Abstract

Tribals are known as the torchbearers of ethnobotany. Traditional plant-derived utility products (PUPs) are environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and easy to handle, and are extensively used by the forest-dwelling Gaddi and Sippi tribes of the Union Territory (UT) of Jammu and Kashmir for their subsistence. The present study is an attempt to document the invaluable traditional knowledge on wild plants and PUPs possessed by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes before it perishes completely, as this knowledge is transmitted orally to the next generation. Semi-structured schedules were used for the collection of data regarding the method of making and usage of PUPs and the plant species used for making such products. The cultural importance index (CI) and factor informant consensus (Fic) were calculated to find the predominant plant species and the consensus among informants for species used in making PUPs, respectively. A total of 52 plant species from 28 families and 46 genera are used in the study area for making 93 PUPs. Tools, with a 55.9% contribution, were the major PUP category. Cedrus deodara, used for making 36 PUPs and having a 4.9 CI value, was the most utilized and important tree species for the Gaddi and Sippi tribes. The values of Fic ranged between 0.97 (miscellaneous PUPs) and 0.99 (containers/storage PUPs). The present study documented 43 plant species as new ethnobotanical records from the UT of Jammu and Kashmir for their use in traditional plant products. The Gaddi and Sippi tribes in the study area have extensive knowledge about forest-based PUPs and the associated plant species. This invaluable knowledge can be exploited for developing new resources for some value-added traditional plant products and agro-based cottage industries, which could play an important role in socio-economic upliftment and livelihood promotion of tribals.

1. Introduction

The dependence of human beings on nature to cater to their varied needs dates back to prehistoric times [1]. Ethnobotany is the study of how the indigenous communities inhabiting a particular region and having their own specific culture utilize locally growing plant species to satisfy some of their basic requirements, like food, fodder, medicine, utility products, clothing, and shelter [2]. Tribals, the torch bearers of ethnobotany, are the ecosystem communities who maintain an intimate connection between humans and the environment as they live in complete harmony with nature [3]. Although they use different types of plants primarily for meeting their own needs, the commercialization of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) has been encouraged as an ecologically sustainable means of promoting the economic well-being of the rural communities [4]. Besides these basic requirements, plant-derived traditional utility products (PUPs), such as agricultural tools, household articles, and construction products, also play a vital role in the sustenance of human beings, particularly the tribals [5]. Traditional knowledge also finds its use in solving the problem of climate change, disaster risk resilience, and preservation of rich cultural heritage [6]. However, most of the previous research work in the field of ethnobotany has been carried out around medicinal and dietary aspects of wild plants, and only a few studies are based on other ethnobotanical uses of plants, including PUPs [7].

Despite all the above advantages, the gradual invasion of modern culture into rural lifestyles has resulted in a loss of traditional cultural heritage [8,9]. The truth that the amassed knowledge on ethnobotany is not recorded, accompanied by a lack of concern among the young generations for this field of study, has resulted in the decline of traditional knowledge in the present time [4,10]. Since the traditional knowledge of plant usage is possessed by only a few community members and is transmitted orally, it will disappear with the death of such knowledgeable persons if not documented [7,11,12,13]. Hence, traditional knowledge needs conservation, and many workers have advocated for the legal protection of traditional knowledge [14].

After Africa, India has the second-largest tribal population in the world [15]. The total population of scheduled tribes in India is approximately 10.45 crore, which constitutes 8.6% of the country’s total population [16]. The Jammu and Kashmir Himalayas are inhabited by many nomadic tribes, including Gaddis, Sippis, Paharis, Gujjars, and Bakarwals, who wander from one place to another to facilitate the grazing of their livestock [17]. According to the Census of 2011, the total population of the Gaddi and Sippi tribes in Jammu and Kashmir was 46,489 and 5966, respectively. In district Doda, however, there are 5999 Gaddis and 810 Sippis [18]. Gaddi and Sippi tribes are forest-dwelling tribes, primarily rearing large flocks of goat and sheep, practicing subsistence agriculture, speaking Gadyali or Gaddi language, wearing unique traditional costumes, and having their own tribal rituals and lifestyle [8]. The Gaddis were described by Chakravarty as “shepherds of the snowy ranges” [19]. One or two male members (locally known as palh) of the Gaddi family undergo seasonal migration along with their flock to district Samba and Kathua in the foothills of the Himalayas during winter and to higher reaches of the Himalayas in district Doda, and Kishtwar and Udhampur during the summer to facilitate grazing of their livestock [20]. Gaddis and Sippis use a wide variety of PUPs in their day-to-day life due to the remoteness of their inhabitants from the nearby cities and towns [21] and their close association with the forests.

A very few comprehensive studies on PUPs have been carried out in the past worldwide [22,23] whereas most such studies are not based on all types of PUPs and involved only traditional agricultural implements [24,25,26,27,28,29,30], or storage structures [31,32,33,34], or construction wood [35], or cookware [36], or handicraft [37,38], or construction and tools [39], or construction wood, handicraft, and fiber [40], or construction, furniture, and agricultural implements [41], or agricultural tools, domestic articles, and handicrafts [23]. At the global level, Zambrana et al. [39], Suksri et al. [42], Ibrar et al. [43], Sop et al. [11], Li et al. [44], and Neelo et al. [45] have documented, inter alia, 25, 14, 12, 54, 4, and 38 plant species used traditionally for construction purposes based on ethnobotanical studies carried out in certain parts of Thailand, Pakistan, Burkino Faso, Tibet, Botswana, and Bolivia, respectively. Some of the most commonly used species, generally large canopy trees, reported in these studies include Cedrela fissilis, Ficus spp., Dalbergia oliveri, Juglans regia, Morus nigra, Olea ferruginea, Parrotiopsis jacquemontiana, Pinus spp., Quercus spp., Abies spp., Acacia spp., Albizia spp., Ziziphus spp., Terminalia spp., Tamarandus indica, and Eucalyptus spp.

Although Jammu and Kashmir has witnessed numerous ethnobotanical explorations [17,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], no research has been conducted on PUPs in the region. The present study is an extensive pioneering research work in UT of Jammu and Kashmir, aiming primarily to (i) enlist the plant species used for making PUPs, (ii) document the PUPs used by Gaddi and Sippi tribes, and (iii) find culturally important plants used for making PUPs. The important hypotheses tested were (i) male members have the higher knowledge of plants and PUPs than female, (ii) aged members knew a greater number of plants and PUPs than youngsters, and (iii) educated members have lesser knowledge of plants used for making PUPs than those who have not attended the school at all.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Bhaderwah is a small yet beautiful valley in Doda district of JKUT located between the outer and middle Himalayas [20] on the 75°39′49.5″ East Longitude and 33°17′33.2″ North Latitude. It is drained by a small rivulet, Neeru, and surrounded by Himalayan mountain peaks with evergreen coniferous forests. The Gaddi and Sippi inhabited village Dhamunda is located at a high elevation in the tehsil Bhaderwah and is one of the most suitable places for paragliding [64]. Bhaderwah is bounded by District Kathua to the south, District Udhampur to the west, District Chamba (H.P) to the southeast, and the District Headquarters Doda to the north. It has a wide range of elevations from 1613 masl to 4320 masl. Bhaderwah valley harbors rich phytodiversity because of the presence of different climatic zones, viz. subtropical, temperate, and alpine, along the altitudinal gradient [65]. It receives heavy snowfall during the winter, whereas the colorful blooming of flowering plants is common during the summer and spring seasons. The temperature lies between 26 °C and 29 °C during summer, and 2 °C and 15 °C during winter. Bhaderwah receives an average rainfall of 1206 mm [62,66].

The six Gaddi and Sippi inhabited villages of Bhaderwah viz., Dhamunda, Manthla (Upper), Dandi, Kansar, Bharie, and Butla, where the survey was conducted, are located at far-flung higher elevations on the slopes of the Himalayan Mountain ranges in the close vicinity of evergreen coniferous forests. Kansar village (2400 m amsl) is the highest inhabited place in Bhaderwah valley, which gets cut off from the surrounding villages and Bhaderwah town due to heavy snowfall during the winter.

2.2. Field Survey

There are a total of 12 villages inhabited by Gaddis and Sippis in Bhaderwah. The research survey was conducted from February 2023 to February 2025 in six randomly selected villages, viz. Dhamunda, Manthla (Upper), Dandi, Kansar, Bharie, and Butla (Table 1). Gaddis are found in all six villages under survey, whereas the Sippi population is found only in four villages, viz., Dhamunda, Kansar, Bharie, and Butla, where they live together with the Gaddi population.

Table 1.

Population and location of the six villages of the study site (source: https://www.censusindia.co.in/villagestowns/bhaderwah-tehsil-doda-jammu-and-kashmir-65, accessed on 12 July 2024).

A door-to-door survey was conducted to collect the required information about plant-based traditional products (PUPs) used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes in the study area. To obtain maximum information, the snowball sampling method was used. In the snowball sampling technique, some knowledgeable informants were initially selected and were asked to refer to other knowledgeable informants known to them, and thus the size of the sample increases manifold, just like the size of a rolling snowball. Thus, a large number of knowledgeable tribal people were identified, out of which a total of 236 informants were randomly selected and included in the sample.

The sample included informants from both genders, mostly elderly persons, farmers, and herders like shepherds (palh) who were intimately associated with forests and had an acquaintance with locally growing plants of ethnobotanical importance. The research study and its objectives were briefly explained to all the respondents before the collection of information, and prior informed consent (PIC) was obtained from each interviewee in written form. The ethnobotanical information was collected from the informants through semi-structured interviews and group discussions. The discussions were carried out in their mother tongue—the Gadyali or Gaddi language. Some information was also collected through direct observations of the daily chores of community members involving the use of PUPs.

After the collection of ethnobotanical data, some of the highly knowledgeable respondents were made to accompany the survey during forest visits for identification and collection of plant specimens used for making PUPs. Such plant species were identified by the respondents based on their vernacular names which were subsequently identified with botanical names with the help of a field guide by Polunin and Stainton [67] and by matching the voucher specimen with the preserved plant specimen in the Herbarium of Department of Botany, University of Jammu and online version of Janaki Amal Herbarium of IIIM, Jammu, https://iiim.res.in/herbarium/herbarium.htm (accessed on 12 July 2024). The plant identification was further confirmed with the help of taxonomic experts from the University of Jammu. Only accepted botanical names have been used in the present study, verified through online taxonomic databases, viz., Plants of the World Online and The World Flora Online https://powo.science.kew.org. All the collected plant specimens were pressed, dried, mounted on the herbarium sheets, and deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Botany, University of Jammu, vide accession numbers mentioned in Table 2. The photographs of PUPs and plants used for making such products were also taken during field visits.

Table 2.

Plant species used for making PUPs.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data collected through questionnaires were analyzed using the cultural importance index (CI) and factor informant consensus (Fic). CI was calculated to find the most important plant species culturally used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes, and Fic expresses the degree of acceptability for the PUPs among the informants.

The cultural importance index (CI) was calculated as the total of use reports (UR) for a species in seven use categories (including three subcategories under the tools category), viz., agricultural tools, tools used for making woolen products, miscellaneous tools, containers or storage products, construction products, artifacts, and miscellaneous products divided by number (236) of informants (N) and mathematically expressed as follows:

where the seven use categories (u) are u1–7 and informants (i) are −i1–236. According to Tardio and Pardo-de-Santayana [68], CI accounts for the spread as well as the versatility of uses. The maximum value of CI is the total number of uses in different use categories, and it is improbable that informants will mention the uses of a species for all these use categories.

Factor informant consensus (Fic), given by Trotter and Logan [69], was calculated using the following formula:

where nur refers to the number of use reports for a particular use category, and nt refers to the number of taxa used for a particular use category by all the informants. Fic values are low (near 0) if the selection of plants is random or if there is no sharing of information amongst informants, and approaches one (1) when the community has a well-defined selection criterion and/or if there is an exchange of information between informants [55].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed using R Studio version 1.2.1335 (R Studio 2019) to test the hypotheses and find the significant difference in knowledge of PUPs vis-à-vis gender, age, and education level of informants.

Two-tailed correlation analysis (at significance level, α = 0.05) was also performed to find the relationship between age and education level of informants with respect to PUPs knowledge.

3. Results

3.1. Informants

A total of 236 informants (91 females and 145 males) were interviewed for the present study (Table 3). The age of the informants varied from 25 to 92 years. The maximum number of male (41, 28.3%) and female informants (29, 31.9%) belonged to the 55–65 years age group. The majority of the female (70; 76.9%) and male (88; 60.7%) informants had never attended the school.

Table 3.

Demographic and educational details of the informants.

3.2. Vegetation Characteristics and Diversity of Plant-Derived Utility Products (PUPs)

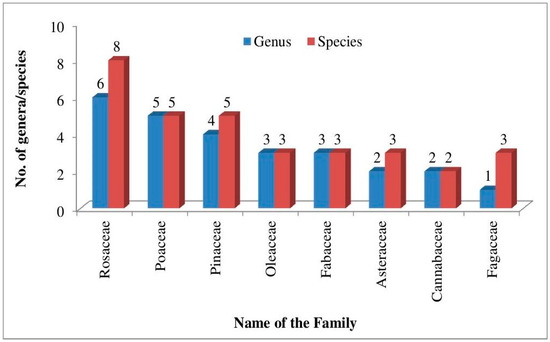

A total of 52 plant species belonging to 46 genera and 28 families were used for making 93 PUPs (Table 2). Angiosperms, gymnosperms, and pteridophytes were represented by 45, six, and one species, respectively. The maximum number of plant species belonged to the family Rosaceae (eight species), followed by Pinaceae and Poaceae (five species each), and Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Fagaceae, and Oleaceae (three species each) (Figure 1). The rest of the families were represented by one species each.

Figure 1.

The most represented families for making plant-derived utility products (PUPs).

As far as life forms are concerned, 28 species were trees, nine shrubs, and 15 herbs. A total of 35 species were used for making tools: 25 species for agricultural tools, 12 species for tools used for making woolen products, and 20 species for miscellaneous tools. The number of species used for making container/storage products, construction products, artifacts, and miscellaneous products was 7, 6, 15, and 23, respectively.

Out of the total 52 reported species, 35 (67%) spp. are native to India, whereas 17 (33%) are exotic or introduced species (Table 2). The native and exotic status of the reported spp. was confirmed by visiting online databases like Plants of the World Online (powo) and the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species—India (GRIIS). The reported native spp. include most of the culturally important plants like Cedrus deodara (4.9 CI), Quercus floribunda (2.89 CI), Pinus wallichiana (1.91 CI), and Aesculus indica (1.18 CI), etc. These spp. have not only cultural and ethnobotanical importance but are also ecologically significant and play a pivotal role in maintaining the ecological balance of their habitats and supporting native wildlife. Some of the exotic spp. like Oryza sativa, Triticum aestivum, and Zea mays are used as staple food crops. Exotic species can sometimes become invasive, outcompeting native flora and altering ecosystems. Hence, their cultivation and spread need to be managed carefully to protect native biodiversity.

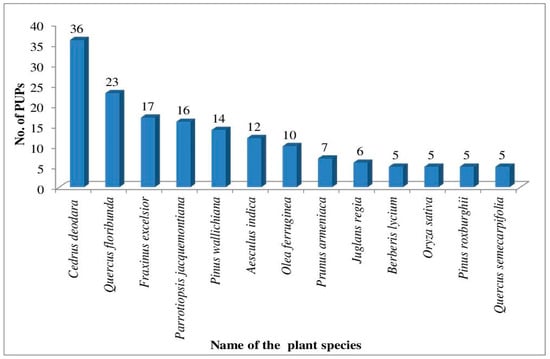

In the present study, 93 plant-derived utility products (PUPs) have been documented (Table 4). These PUPs are used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes of the study area in their day-to-day life for different purposes. These products are prepared from 52 locally growing plant species (Table 2), mostly wild plants. The largest number of PUPs was made from Cedrus deodara and Quercus floribunda, which were used for making 36 and 23 PUPs, respectively (Figure 2). These were followed by Parrotiopsis jacquemontiana (16 PUPs), Fraxinus excelsior (15 PUPs), Pinus wallichiana (14 PUPs), and Aesculus indica (12 PUPs). For the convenience of study, these plant products were arbitrarily classified into five major categories, viz., tools, containers/storage products, construction products, artifacts, and miscellaneous products.

Table 4.

Plant species and plant-based traditional products (PUPs) used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes.

Figure 2.

Plant species with the highest number of plant-derived utility products (PUPs).

3.3. Tools

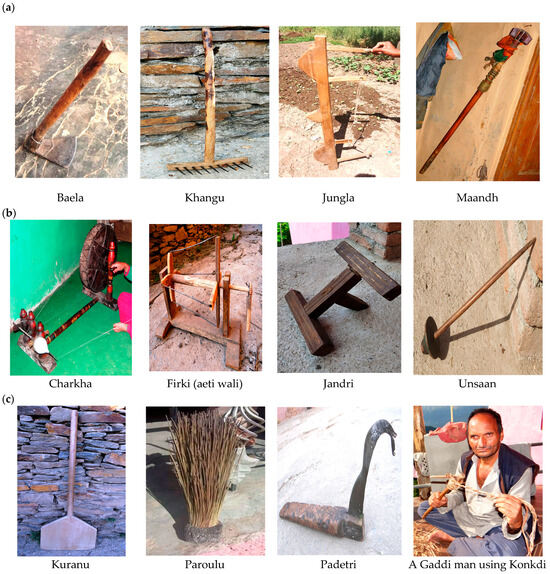

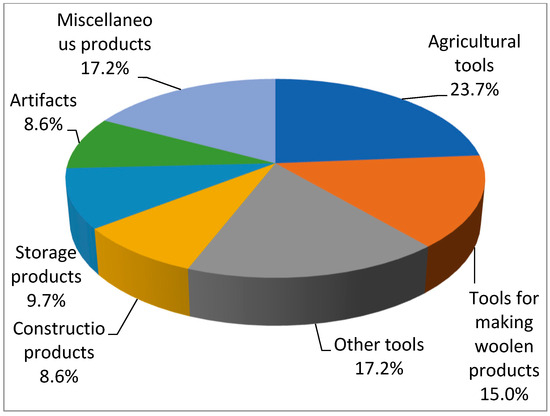

A tool is a product designed to facilitate a particular type of manual work. The number of tools (52) reported is 55.9% of the total PUPs. These tools are used for carrying out different activities in day-to-day life. Tools can be further classified into three sub-categories viz. agricultural tools (Figure 3a), tools for making woolen products (Figure 3b), and other/miscellaneous tools (Figure 3c), and their numbers are reported as 22 (23.7% of total PUPs), 14 (15.1%), and 16 (17.2%), respectively (Figure 4). All parts of traditional handlooms are made up of wood and are derived from different plant species. Miscellaneous tools include all other tools which could not be included in the above two sub-categories, e.g., shrub broom (loath)—a broom used for sweeping houses and lawns, sickle for cutting vegetables (padetri), washing bat (dabotan)—a wooden bat used for washing clothes, churner (maandh)—a wooden churner used for churning buttermilk, snow shovel (kuranu), and snow clearing frame (masheen)—a wooden tool with the triangular working frame used for clearing snow from roofs etc.

Figure 3.

Photographs of tools: (a) agricultural tools, (b) tools used for making woolen products, and (c) miscellaneous tools.

Figure 4.

Contribution of various types of PUPs.

3.4. Containers/Storage Products

These products are used for holding or storing different objects (Figure 5). Nine products (9.7%) were reported from this category. These containers/storage products are a grain storage fixed compartment (kuthar) and moveable compartment (toon); flour storage bin (koolhi); honey barrel (ganarh); dog feeding container (kutroshu); cattle watering long trough (charh); cattle feeding trough (kunala); large, fixed tub for washing woolen clothes (kund); and storage box for storing household articles (sandook).

Figure 5.

Photographs of containers/storage products.

3.5. Construction Products

These products are used in construction work (Figure 6). Eight (8.6%) of these products were reported in the present study. For example, products used for the construction of shelters such as houses, field security shed (tapri), cattle compartment (gaien), lamb shelter (oda), roof shafts (faantu), and roofing material (othan). Besides shelters, some other structures are also constructed by using construction products, e.g., a hay rack (gaali), a log foot-bridge (tarangdi), and farm fencing (baad).

Figure 6.

Photographs of PUPs used for construction purposes.

3.6. Artifacts

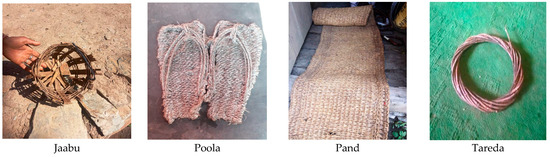

The handmade products of cultural interest (Figure 7) included eight products (8.6%). For example, paddy straw carpet (pand) and paddy straw rug (chakotu), paddy straw slippers (poola), fiber rope (jodi), and traditional cot (manja).

Figure 7.

Photographs of artifacts.

3.7. Miscellaneous Products

This category comprises all other products that could not be included in any of the above-mentioned categories. As many as 16 (17.2%) of such products have been documented in the present study.

3.8. Current Status of PUPs

Twenty PUPs that were popular among these communities during the recent past have been reported by the informants to be rare PUPs and are on the verge of disappearance due to the availability of modern tools/items. These include frame for arranging warp fiber (aernoti), take up roll (belnu), washing bat (dabotan), reed/hand beater (hatha), noodle making tool (jandra/Bhedu), frame for making double thread (jandri), weaving shuttle (naal), treadles/foot pedal (khadavan), handloom (khadi), snow shovel (kuranu), snow clearing frame (masheen), wood channel water spring (naadu), weft loading stick (tarnethi), flour storage bin (koolhi), grain storage fixed compartment (kuthar), grain storage moveable compartment (toon), rope (jodi), cattle feeding trough (kunala), straw slippers (poola), and hand spindle (unsan).

Four PUPs, viz., scrubber (shota), fruit of Aesculus indica, used as detergent (goon), rhizome of Dioscorea deltoidea used as detergent (kins), and dog feeding container (kutroshu), were reported to have disappeared completely from the life of these tribes during the recent past and are no longer in use.

3.9. Cultural Importance Index (CI)

The maximum value of the cultural importance index (CI) was recorded for Cedrus deodara (4.92). The top three major contributors were miscellaneous tools (CIOT, 1.11), container/storage products (CICS, 1.05), and tools used for making woolen products (CIWP, 1.03) (Table 5). Quercus floribunda, with 2.89 CI, was the next most important plant in the Gaddi and Sippi culture, mainly used for making agricultural tools (CIAT, 2.0). Other important species with more than 1.0 CI were Juglans regia (CI, 1.74), Pinus wallichiana (CI, 1.91), and Aesculus indica (CI, 1.18).

Table 5.

The cultural importance index of species used for making PUPs.

3.10. Factor Informant Consensus (Fic)

All the PUPs were classified into five categories (Table 6). The values of factor informant consensus (Fic) for these categories ranged between 0.970 (miscellaneous products) and 0.985 (tools). The highest citation (3704) and number of species (57) were utilized for the tools category. The major share of contribution was from agricultural tools (1639 citations; 26 species), followed by miscellaneous tools (1061 citations; 19 species) and tools for woolen products (1004 citations; 12 species). Other important categories were artifacts (685 citations; 15 species) and miscellaneous products (671 citations; 21 species).

Table 6.

Factor informant consensus (Fic) of various PUP categories.

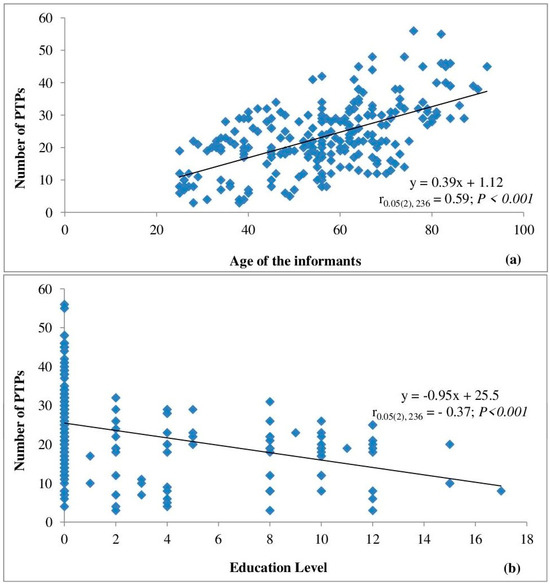

3.11. Knowledge of PUPs with Respect to Gender, Age, and Educational Level

The number of PUPs known to males (29.4) was significantly (F-value, 91.7; p-value < 0.001) higher than the female (18.1) informants (Table 7). The informants in the 75- to 84-year age group reported the highest number of PUPs for both female (30.8) and male (44.5) informants. Informants who had never attended a school had the maximum information regarding PUPs, with female and male informants having, on average, the data of 20.7 and 34.1 PUPs, respectively. Correlation analysis (r0.05,(2),236 = 0.60; p < 0.001) shows that with the increase in the age of informants, the knowledge of PUPs increased significantly (Figure 8a). Education of the informants was significantly (p < 0.001) and inversely correlated (r0.05,(2),236 = −0.37) to the number of PUPs reported by the informants, i.e., as the education level of the informants increased, the information regarding PUPs decreased (Figure 8b).

Table 7.

A comparison of the number of plants known to informants with respect to gender, age, and education.

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis between age and knowledge of plant-based traditional products/Plant-based utility products (PTPs/PUPs) (a), and education level and knowledge of (PTPs/PUPs) (b).

4. Discussion

Bhadarwah is located in the Western Himalayan region with an altitudinal variation of 1613 to 4320 m amsl. The area supports rich phytodiversity along its altitudinal gradient. The region is dominated by Pinus roxburghii, Quercus floribunda, and Pyrus pashia up to 2000 m amsl, Cedrus deodara, Pinus wallichiana, Quercus leucotrichophora, Quercus semecarpifolia, and Aesculus indica up to 3000 m amsl, and Abies pindrow, Picea smithiana, Taxus baccata, and Betula utilis up to 3500 m amsl. Gaddi and Sippi tribes use all these and other associated plant species for making PUPs. A combination of rich phytodiversity and the remotest location of Gaddi and Sippi settlements in the Bhaderwah Himalayan region has resulted in valuable ethnobotanical heritage in this region.

4.1. Vegetation Characteristics and PUPs Diversity

A total of 52 plant species are used for making 93 PUPs in the present study. The number of species used is higher than those of many similar studies carried out in India [22,25,27], whereas Kang et al. [40] has reported the use of 84 species from Heihe Valley, China, and Salernao et al. [23] have mentioned the usage of 60 species from Basilicata, Italy.

High diversity in traditional usage of plants and PUPs by Gaddis and Sippis shows that: (i) they are intimately associated with the forests, visit diverse habitats, and have greater knowledge of vegetation of the region, (ii) the traditional knowledge is well dispersed from one generation to another, (iii) they still use and rely on PUPs for their sustenance, and (iv) the study area harbors rich phytodiversity. Many PUPs are used as cheaper substitutes to market products by poor rural communities like the Gaddi and Sippi tribes, who cannot afford to market products. Hence, PUPs can be referred to not only as eco-friendly products but also as friendly to poor people, as they help them in coping with poverty.

Wild plants form an integral part of the culture and traditions of the Himalayan tribal communities [70]. The usage of a large number of tools by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes in agricultural practices (22) and for making woolen products (14) provides a deep insight into their pastoral occupation of practicing subsistence agriculture and rearing goats and sheep, respectively. Thus, the conservation of PUPs will also lead to the conservation of the culture of these Himalayan tribal communities.

A large number of timber-yielding plant species have been safely utilized for hundreds of years for making food container items, and such plant species have not shown any detrimental effect on human health [36]. Rural communities are highly skilled in making traditional grain storage structures [32], and wood is one of the basic materials utilized for making such structures [31]. Plant-based grain storage structures used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes include fixed containers (kuthar) and moveable compartments (toon). Such storage structures are used by farmers for storing grains as they are cheaper, eco-friendly, protect grains from insects, and provide high shelf life to stored grains [34].

4.2. Culturally Important Plant Species and PUPs

The informants were highly knowledgeable about the wood properties of different species and their suitability for making different PUPs. As per the cultural importance index (CI), the most important species for the Gaddi and Sippi tribes are Cedrus deodara, Quercus floribunda, Pinus wallichiana, Juglans regia, and Aesculus indica.

Cedrus deodara is culturally the most important species used for making PUPs. More than one-third of the total PUPs were made from Cedrus deodara. The stem and branches of Cedrus deodara are long and straight; its wood has a smooth surface and is highly durable and insect-resistant due to the presence of aromatic oils, which possess insecticidal properties. In addition to this, Cedrus deodara wood is stronger than that of Abies pindrow, Pinus wallichiana [71], and other Indian conifers [72]. Hence, Cedrus deodara wood is highly preferred by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes for making long or large containers/storage products (charh, kunala, ganarh, kund, etc.) and construction products (gaali, tarangdi, baad, etc.).

It was pointed out by the respondents that the wood of Quercus floribunda, Quercus semecarpifolia, and Parrotiopsis jacquemontiana is very hard, strong, and durable and was therefore used for making agricultural tools like plow, plow shoe, small hand hoe, hoe, large sickle, mallet, etc. This is because these tools require the application of high mechanical force during operation and need to be strong enough to withstand the applied force without sustaining any damage.

The wood of Juglans regia is preferred by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes for making PUPs due to its strength and durability. Vassilion and Voulgaridis [73] have also reported the strength, durability, and good quality of Juglans regia wood. The wood of this species is used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes for making tools used for weaving woolen products (spinning wheel, reed, and shaft), a snow shovel, a wood shaving plane, and a palanquin. Bhangali tribe of Western Himalayan region of Chhota Bhangal also use wood of Juglans regia, primarily for making tools used in weaving [22], whereas in Greece it has multipurpose use where it is used for making esthetic/decorative items, furniture, music instruments, carving, sports items, gun stocks and in construction work [73].

According to the Gaddi and Sippi tribes, the wood of Pinus wallichiana is moderately strong but highly durable and free from insect attack due to the high content of aromatic oils in it. This species is one of the most preferred timber-yielding species used for construction and furniture making in the entire Himalayan region [74]. The wood of Aesculus indica was used for the preparation of 12 PUPs by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes, and it is also known for its strength and unbreakability [22].

Koolhi, a flour storage bin, is made from mud mixed with wheat and barley straw, locally known as kinyahri, which prevents shrinkage cracks in it. This is in line with the findings of Ashour and Wu [75], who reported that crack formation in mud plaster decreases with an increase in fiber content and increases with an increase in soil content.

4.3. Consensus for the Usage of PUPs

The values of factor informant consensus (Fic) were very high and had a narrow range of 0.968 to 0.991. Bhatia et al. (2018) have also reported very high values of Fic for the usage of wild edible plants in Udhampur, J&K [55]. High values of Fic may be ascribed to frequent sharing of knowledge regarding PUPs and a greater degree of consensus among the informants regarding species used for making a particular PUP [55,56,57]. Nearly two-thirds (66.1%) of the citations pertain to the tools category, which substantiates the fact that the Gaddi and Sippi tribes have a pastoral occupation of practicing agriculture, rearing goats and sheep, and weaving woolen products, which involves the use of a large number of tools.

4.4. Knowledge of PUPs

Male informants possessed significantly higher knowledge about the PUPs than the females, thus supporting our first hypothesis. These results are in accordance with Sharma et al. (2019), who have also recorded significantly higher numbers of PUPs known to males than females in the western Himalayas [22]. Ethnobotanical research in the region [22,56,63] and other parts of the world [76,77,78,79] has also indicated that men play a greater role in traditional knowledge, especially of plants used in making tools and crafts, and construction works [80,81]. However, the majority of earlier studies [55,61] have demonstrated that women tend to have a more traditional understanding, as they typically lack employment in rural areas and devote their time to household and subsistence tasks. In contrast, a few other studies [82,83] found no significant difference between genders. The higher knowledge of PUPs is possessed by males because they are more often active in resource extraction and PUP production than women [22] and because of their nomadic behavior [63]. During the summer, the men of the tribes under investigation travel to temperate regions, while during the winter, they travel to tropical areas, penetrating far into the forest, passing through a variety of habitats, and encountering many challenges, all of which add to their understanding of plants, their properties and utility.

The elder members knew a greater number of plants used for making PUPs than the younger ones, thus supporting our second hypothesis. Similar findings are also recorded in the Himalayas [22,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63], other parts of India [6,62], and the world [43,44,45,74,82]. A significant positive correlation was also found between the age of the informants and the knowledge possessed by them about PUPs, i.e., the knowledge of PUPs increased with the age of the informants. Hence, traditional knowledge is confined mostly to the older people, as the younger generations of these tribes are least interested in using PUPs. Recent research also suggests that conventional wisdom is in decline [22,55,63], probably due to changing lifestyle [84], urbanization and modernization [55], and market forces [85].

In relation to the third hypothesis, this study found that educated members had less knowledge of plants used for making PUPs. These results are further corroborated by correlation analysis, which shows a significant decline in informant knowledge of PUPs as the education level rises. Similar trends have been reported in other studies [8,9]. Most of the educated and employed youth of the Gaddi and Sippi tribes migrated from villages and settled permanently in nearby towns and cities. It also resulted in the invasion of modern culture into the tribal lifestyle of these communities, which is one of the most important reasons for the decline in the use of PUPs by these communities, especially the younger generations. Recently, five out of six villages under survey, viz., Dhamunda, Manthla (Upper), Kansar, Dandi, and Butla have been connected by motorable roads, whereas roads to the remaining one village under survey, viz., Bharie, are under construction. Atreya et al. [86] reported that increasing road linkages are one of the factors responsible for the decline in traditional practices in rural areas.

4.5. Current Status of PUPs in Bhaderwah

As reported by the informants, their forefathers knew a greater number of PUPs. They also stated that a sharp decline in the occupation of shepherding has been observed in the study area over the last two and a half decades, resulting in a decrease in the production of wool and woolen products. Hence, the making and use of plant-derived traditional tools used in traditional handloom weaving and the associated traditional skills have also diminished in the recent past. Such tools can be categorized under the category of rare PUPs and are on the verge of extinction.

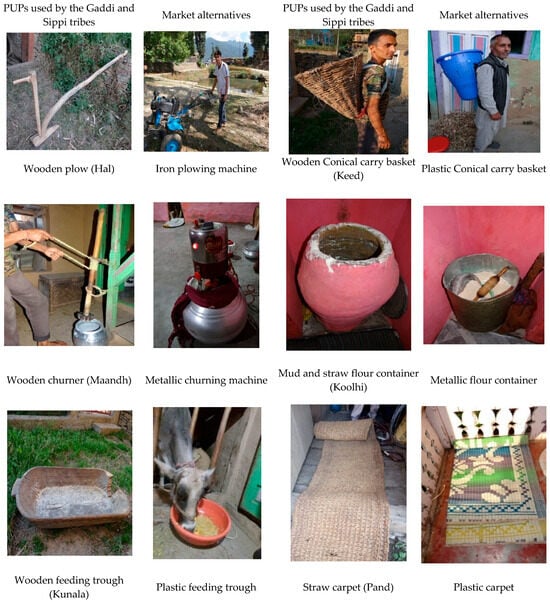

Some of the PUPs that were most commonly used among the Gaddi and Sippi tribes have recently been substituted by alternate market products (Figure 9). This is due to increased accessibility of local markets to these tribes as a result of the establishment of road connectivity to some of their inhabited areas and increased financial capabilities of the community members to purchase market products. For example, rhizomes of Dioscorea deltoidea (kins) and fruit of Aesculus indica (goon), which were used for washing clothes due to their ability to generate foam, have been substituted by soap and detergents. Cob sheath of maize and leaves of Pteris biaurita (shota) used as scrubbers for washing utensils have been substituted by nylon and steel scrubbers available in the markets, and dog feeding containers (Kutroshu) have been substituted by plastic and metal containers. It was observed that the availability of alternatives in the market has resulted in a decline in the use of plants for making traditional products [22]. The same findings have also been reported in some other studies [87,88].

Figure 9.

Photographs of traditional PUPs and their market alternatives used by the Gaddi and Sippi tribes.

4.6. Novelty and Future Prospects

The present work is one of the pioneering works and the first of its kind from UT of J&K, and also in terms of the tribes selected for ethnobotanical investigations. However, Singh et al., 2021 [65], carried out a trivial study on PUPs in UT of J&K and have reported the use of 10 plant species for making tools used for making woolen products from Doda district (UT of J&K), out of which nine species, namely Aesculus indica, Berberis lyceum, Cedrus deodara, Juglans regia, Fraxinus excelsior, Pinus wallichiana, P. roxburghii, Prunus armeniaca, and Quercus floribunda, have also been reported in the present study. Hence, except the aforementioned nine species, all other 43 plant species out of the total 52 species (Table 2) documented in the present study are the new reports from UT of J&K to the best of our knowledge as far as their utilization for making traditional PUPs is concerned. Tribals have ample knowledge about the utility of various plant species, which are still unknown to modern society. Such plants and the associated knowledge about their utility can be exploited for developing new resources for some value-added plant products and agro-based cottage industries such as basketry, carpet industry, wooden containers, broom making industries, etc., which may pave the way for obtaining patents for some of the PUPs. Since PUPs play an important role in socio-economic upliftment and eco-friendly livelihood promotion of tribals, multiplication and conservation of the plants with high CI values like Cedrus deodara (4.9 CI), Quercus floribunda (2.89 CI), Pinus wallichiana (1.91 CI), etc., is strongly recommended.

5. Conclusions

Gaddi and Sippi tribes of the study area are highly skilled in making and using a wide variety of plant-derived utility products (PUPs). Some of the important factors that can be attributed to the use of PUPs by these tribes are remoteness of their inhabitants, lack of market access, pastoral and semi-nomadic lifestyle, location of their inhabitation in and around forests, lack of road connectivity, and poverty. However, a decline has been observed in the use of PUPs by the tribes under investigation in the recent past. Hence, it is recommended that efforts should be made to conserve the indigenous skills, culture, and traditions of these tribes without compromising their socio-economic development. This invaluable knowledge about PUPs, confined to the tribal groups, should be commercially exploited for the extension of their use to mainstream society. District Industries Centre, Doda, and SC, ST, OBC Corporation, Doda should encourage the setting up of cottage industries for making value-added PUPs by providing subsidized financial assistance and technical and marketing support to these tribals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.; funding acquisition, I.S.; methodology, R.K.M. and I.S.; supervision, V.S.; writing—original draft, B.P.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and R.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the informants involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the informants who can be identified.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the conduct and writing up of the manuscript are incorporated in the research article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly thankful to the informants for providing the information and allowing the taking of photographs of PUPs. Thanks are also due to the taxonomists of the University of Jammu for identifying plant species. We are also grateful to the Curator of the Herbarium at the University of Jammu for providing access to the herbarium for the authors and for assigning Accession Numbers to all deposited herbarium specimens. The KU Research Professor Program of Konkuk University supported this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Choudhary, B.L.; Katewa, S.S.; Galav, P.K. Plants in material culture of tribals and rural communities of Rajsamand district of Rajasthan. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2008, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Wani, Z.A.; Dhyani, S. Ethnobotanical study of the plants used by the local people of Gulmarg and its allied areas, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Int. J. Curr. Res. Biosci. Plant Biol. 2015, 2, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sajem, A.L.; Gosai, K. Traditional use of medicinal plants by the Jaintia tribes in North Cachar Hills district of Assam, northeast India. J. Ethnobiol.Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binfield, L.; Britton, T.L.; Dai, C.; Innes, J.L. Evidence on the Social, Economic, and Environmental Impact of Interventions That Facilitate Bamboo Industry Development for Sustainable Livelihoods: A Systematic Map. Forests 2025, 16, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharwal, A.D.; Rawat, D.S. Ethnobotanical studies on timber resources of Himachal Pradesh (HP), India. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2009, 9, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.; Sonar, R.M.; Jain, K. Traditional knowledge research in India: A bibliometric-based review and thematic analysis. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2025, 24, 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Maguipuinamei, M. Traditional Knowledge, Traditional Cultural Expressions and Intellectual Property Rights of Tribes in North-Eastern Region of India. Intern.Res. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2016, 6, 226–236. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, K. Beyond Visual Culture: A Study of Material Culture of a Transhumant Gaddi Tribe of North India. Int. J. Med. Res. Prof. 2015, 1, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.C.; Lin, S.; Shen, A.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Huai, H.Y. Traditional knowledge on “Luchai” [Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. and Arundo donax L.] and their dynamics through urbanization in Yangzhou area, East China. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, G. A study on the traditional textile motifs of Dimasa Kacharis in the Cachar District of Assam. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2025, 24, 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Biona, T.; Keithellakpam, O.S.; Nameirakpam, B.; Sougrakpam, S.; Nahakpam, S.; Lalvenhimi, S.; Nambam, B.; Ashihe, D.; Deb, L.; Bhardwaj, P.K.; et al. Ethnobotany of traditional medicinal plants used in Senapati district of Manipur, Northeastern India. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2025, 24, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dagni, A.; Suharoschi, R.; Hegheș, S.-C.; Vârban, R.; Lelia Pop, O.; Vulturar, R.; Fodor, A.; Cozma, A.; Soukri, A.; El Khalfi, B. Ethnobotanical Survey on Plants Used to Manage Febrile Illnesses among Herbalists in Casablanca, Morocco. Diversity 2023, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slathia, P.S.; Paul, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Sharma, B.C.; Kumar, R.; Kher, S.K. Traditional uses of under-utilized tree species in sub-tropical rainfed areas of Kathua, Jammu & Kashmir. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2017, 16, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bath, S.; Prasad, S. Legal protection of traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions under copyright laws. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2025, 24, 384–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap, S.D.; Deokule, S.S.; Pawar, P.K.; Harsulkar, A.M. Traditional ethnomedicinal knowledge confined to the Pawra tribe of Satpura Hills, Maharashtra, India. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2009, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Govt. of India. Available online: https://tribal.nic.in/ST/Statistics8518.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Sharma, P.K.; Singh, V. Ethnobotanical studies in northwest and Trans-Himalaya. V. Ethno-veterinary medicinal plants used in Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989, 27, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, District Wise ST Population, J&K. 2011. Available online: https://dev.ihsn.org/nada//catalog/58335 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Chakravarty-Kaul, M. Transhumance and customary pastoral rights in Himachal Pradesh: Claiming the high pastures for Gaddis. Mt. Res. Dev. 1998, 18, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, H.C.; Bhagat, N.; Pandita, S. Oral traditional knowledge on medicinal plants in jeopardy among Gaddi shepherds in hills of northwestern Himalaya, J&K, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, T.; Malik, Z.H.; Dar, M.E.; Shaheen, H. Wood utilization pattern in Kashmir region, western Himalaya. For. Prod. J. 2016, 66, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Thakur, D.; Uniyal, S.K. Plant-derived utility products: Knowledge comparison across gender, age and education from a tribal landscape of western Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, G.; Guarrera, P.M.; Caneva, G. Agricultural, domestic and handicraft folk uses of plants in the Tyrrhenian sector of Basilicata (Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2005, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K.; Nag, D. Traditional agricultural tools—A review. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2006, 5, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Veeraragavathatham, D.; Karpagam, D.; Firdouse, S.A. Traditional tools in agricultural practices. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2009, 8, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, D. Plant species used as traditional agricultural implements and tools in Garhwal region of western Himalaya. Ind. J. Scient. Res. Technol. 2014, 2, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, B.; Sundaram, P.K.; Dey, A.; Kumar, U.; Sarma, K.; Bhatt, B.P. Traditional agricultural tools used by tribal farmers in Eastern India. Res. J. Agri. Sci. 2015, 6, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Brahma, N.; Daimary, L. The Traditional agricultural tools and technology used by the Bodos. IOSR J. Human. Soc. Sci. 2017, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, U.; Paul, N.; De, D.; Giri, S.; Kundu, M.C. Indigenous traditional tools and implements used in agriculture and allied sector in Tripura. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2020, 9, 2102–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramv, P.K.; Sarkar, B.; Raghav, D.K.; Mali, S.S.; Anurag, A.P.; Kumar, U.; Bhatt, B.P. Traditional Agricultural Tools used by Tribal Farmers in Chhotanagpur Plateau. Ind. J. Hill Farm. 2020, 6, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar, P.; Sharma, N. Traditional storage structures prevalent in Himachali homes. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2006, 5, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Nagnur, S.; Channal, G.; Channamma, N. Indigenous grain structures and methods of storage. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2006, 5, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramari, M.; Ganesh, S.; Kannan, G.S.; Seethalakshmi, M.; Gopalsamy, K. Indigenous grain storage structures of South Tamil Nadu. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2011, 10, 380–383. [Google Scholar]

- Mobolade, A.; Bunindro, N.; Sahoo, D.; Rajashekar, Y. Traditional methods of food grains preservation and storage in Nigeria and India. Ann. Agri. Sci. 2019, 64, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujarwo, W.; Keim, A.P. Ethnobotanical study of traditional building materials from the Island of Bali, Indonesia. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.K.; Adei, E.; Adei, D.; Ansah, G.O. Assessment of local wood species used for the manufacture of cookware and the perception of chemical benefits and chemical hazards associated with their use in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, Y.; Nedelcheva, A.M.; Dragica, O.P.; Padure, I.M. Plants used in traditional handicrafts in several Balkan countries. Ind. J. Trad. Knowl. 2008, 7, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcheva, A.; Dogan, Y.; Obratov-Petkovic, D.; Padure, I.M. The traditional use of plants for handicrafts in southeastern Europe. Hum. Ecol. 2011, 39, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Bussmann, R.W.; Hart, R.E.; Huanca, A.L.M.; Soria, G.O.; Vaca, M.O.; Alvarez, D.O.; Moran, J.S.; Moran, M.S.; Chavez, S.; et al. Traditional knowledge hiding in plain sight–twenty-first century ethnobotany of the Chácobo in Beni, Bolivia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kang, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, M.; Ji, X.; Li, D.; Stawarczyk, K.; Luczaj, L. Plants as highly diverse sources of construction wood, handicrafts and fibre in the Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, China): The importance of minor forest products. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Saklani, A.; Lal, B. Ethnobotanical observations on some gymnosperms of Garhwal Himalaya, Uttar Pradesh, India. Econ. Bot. 1990, 44, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksri, S.; Premcharoen, S.; Thawatphan, C.; Sangthongprow, S. Ethnobotany in Bung Khong Long non-hunting area, Northeast Thailand. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2005, 39, 519–533. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrar, M.; Hussain, F.; Sultan, A. Ethnobotanical studies on plant resources of Ranyal hills, District Shangla, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2007, 39, 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Zhuo, J.; Liu, B.; Jarvis, D.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical study on wild plants used by Lhoba people in Milin County, Tibet. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelo, J.; Kashe, K.; Teketay, D.; Masamba, W. Ethnobotanical survey of woody plants in Shorobe and Xobe villages, northwest region of Botswana. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrol, B.K.; Kapoor, L.D.; Chopra, I.G. Pharmacognostic study of the rhizome of Dioscorea deltoide a Wall. Planta Med. 1962, 3, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachroo, P.; Nahvi, I.M. Ethnobotany of Kashmiris. In Forest Flora of Srinagar and Plants of Neighbourhood, 1st ed.; Singh, G., Kachroo, P., Eds.; Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh: Dehra Dun, India, 1976; pp. 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, T.N. Wild edible plants of Jammu & Kashmir state–an ethno-botanical study. Anc. Sci. Life 1988, 3–4, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, M.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Singh, V. Ethnobotanical Studies in Northwest and Trans-Himalaya Vi. Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Basohli-Bani Region, J&K, India. Nelumbo 1989, 31, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, H.S.; Kapahi, B.K.; Srivastava, T.N. Non-Timber forest wealth of Jammu and Kashmir State (India). Plant J. Non-Timb. For. Prod. 1999, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Anand, V.K.; Sarwar, J. Less known wild edible plants used by the Gujjar tribe of district Rajouri, Jammu and Kashmir State. Int. J. Bot. 2008, 4, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Kumar, S.; Hamal, I.A. Medicinal plants of Sewa river catchment area in the Northwest Himalaya and its implication for conservation. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2009, 13, 1113–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Hamal, I.A. Wild edibles of Kishtwar high altitude national park in northwest Himalaya, Jammu and Kashmir (India). Ethnobot. Leafl. 2009, 13, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gairola, S.; Sharma, J.; Bedi, Y.S. A cross-cultural analysis of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh (India) medicinal plant use. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 925–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, H.; Sharma, Y.P.; Manhas, R.K.; Kumar, K. Traditionally used wild edible plants of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Sharma, Y.P.; Manhas, R.K.; Bhatia, H. Ethnomedicinal plants of Shankaracharya Hill, Srinagar, J&K, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 170, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.K.; Hasan, S.S.; Bhellum, B.L.; Manhas, R.K. Ethnomedicinal plants of Kathua district, J&K, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trak, T.H.; Giri, R.A. Inventory of the plants used by the tribals (Gujjar and bakarwal) of district Kishtwar, Jammu and Kashmir (India). Ind. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 13, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.; Singh, S.; Puri, S. Exploration of wild edible plants used as food by Gaddis-a tribal community of the Western Himalaya. Sci. World J. 2020, 6280153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, B.; Sharma, Y.P.; Gairola, S. The wild edible plants of Paddar valley, Jammu division, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Sharma, Y.P.; Hashmi, S.A.J.; Kumar, S.; Manhas, R.K. Ethnomycological study of wild edible and medicinal mushrooms in district Jammu, J&K (UT), India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, N.; Upadhyay, H.; Manhas, R.K.; Gupta, S.K. Wild Edible Plants of Purmandal block of District Samba, J&K (UT), India. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2022, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.P.; Devashree, Y.; Sharma, V.; Manhas, R.K. Diversity of wild edible plants and fungi consumed by seminomadic Gaddi and Sippi tribes in Doda district of Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2023, 25, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, K. An Assessment of Tourism Potential in Bhaderwah (J&K). Ind. Streams Res. J. 2013, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.P.; Kumar, B.; Devi, A. Traditional handloom weaving: A cultural heritage in jeopardy among Gaddi scheduled tribe of Bhaderwah (J&K), North West Himalayas. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2021, 7, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. Water Quality Characterization and Assessment of Pollution Load in Neeru Watershed Bhaderwah, J&K. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Jammu, Jammu, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Polunin, O.; Stainton, A. Concise Flowers of Himalayas; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 1987; ISBN-13: 978-0-19-564414-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tardio, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural importance indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.T.; Logan, M.H. Informant consensus: A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet, Behavioural Approaches; Etkin, N.L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; pp. 91–112. ISBN 9780913178027. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, D.; Bhatt, A.; Lal, B. Ethnobotanical knowledge among the semi-pastoral Gujjar tribe in the high altitude (Adhwari’s) of Churah subdivision, district Chamba, Western Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, K.M.; Khan, J.A.; Mahmood, I. Comparison of anatomical, physical and mechanical properties of Abies pindrow, Cedrus deodara and Pinus wallichiana from dry and wet temperate forests. Pak. J. Forest. 1989, 39, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.P.; Singh, B.S.; Dey, S. Plant Biodiversity and Taxonomy; Daya Publishing House: Delhi, India, 2002; ISBN 81-7035-289-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliou, V.G.; Voulgaridis, E.V. Wood properties and utilisation potentials of walnut wood (Juglans regia L.) grown in Greece. Acta Hortic. 2005, 705, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.M.; Mughal, A.H.; Malik, A.R.; Khan, P.A.; Shazmeen, Q. Natural regeneration status of blue pine (Pinus wallichiana) in north west Himalayas, India. Ecoscan 2015, 9, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour, T.; Wu, W. The influence of natural reinforcement fibres on erosion properties of earth plastermaterials for straw bale buildings. J. Build. Appr. 2010, 5, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorou, S.N.; De Kesel, A. Connaissances ethnomycologiques des peuples Nagot du centre du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest). Proceedings of the XVIth AETFAT Congress, Brussels 2000. Syst. Geogr. Plants 2002, 71, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, M.; Balslev, H. Perception, use and availability of woody plants among the Gourounsi in Burkina Faso. Biodiver. Conser. 2003, 128, 1715–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Kang, J.; Zhang, S. Wild food plants and wild edible fungi in two valleys of the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, central China). J. Ethnobiol.Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotowski, M.A.; Pietras, M.; Łuczaj, L. Extreme levels of mycophilia documented in Mazovia, a region of Poland. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesheim, I.; Dhillion, S.S.; Stølen, K. What happens to traditional knowledge and use of natural resources when people migrate? Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.R.; Lopes, M.A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of palms (Arecaceae) in eastern Amazonia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 21, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turreira Garcia, N.; Theilade, I.; Meilby, H.; Sørensen, M. Wild edible plant knowledge, distribution and transmission: A case study of the Achí Mayans of Guatemala. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakurel, D.; Upreti, Y.; Łuczaj, L.; Rajbhandary, S. Foods from the wild: Local knowledge, use pattern and distribution in Western Nepal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, S.K.; Awasthi, A.; Rawat, G.S. Developmental processes, changing lifestyle and traditional wisdom: Analysis from western Himalaya. Environment 2003, 23, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodirekkala, K.R. Internal and external factors affecting loss of traditional knowledge: Evidences from a horticultural society in South India. J. Anthropol. Res. 2017, 73, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atreya, K.; Pyakurel, D.; Thagunna, K.S.; Bhatta, L.D.; Uprety, Y.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Oli, B.N.; Rimal, S.K. Factors contributing to the decline of traditional practices in communities from the Gwallek–Kedar area, Kailash sacred landscape. Nepal. Environ. Mgmt. 2018, 61, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Macia, M.J. The benefits of traditional knowledge. Nature 2015, 518, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byg, A.; Balslev, H. Diversity and use of palms in Zahamena, eastern Madagascar. Biodivers. Conserv. 2001, 10, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).