Abstract

The insectivores (order Eulipotyphla) of Saudi Arabia consist of six species in four genera within two families (Erinaceidae and Soricidae). Details on the past and present distribution of the insectivores are included as well as illustrations for each species, along with available data on their habitat preferences and biology. The Ethiopian hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus, was the most common species inhabiting the arid deserts of Saudi Arabia. An analysis of the insectivorous fauna of Saudi Arabia revealed that they have two major zoogeographical affinities: the Palaearctic (Hemiechinus auratus, Paraechinus hypomelas and Crocidura gueldenstaedtii) and Afrotropical–Palaearctic (Paraechinus aethiopicus), which are endemic to the Arabian Peninsula (Crocidura dhofarensis), and one introduced species (Suncus murinus). Southwestern Saudi Arabia has the highest species richness. The Arabian white-toothed shrew, Crocidura arabica, is expected to occur in the extreme southwest. The conservation status and threats affecting insectivores in Saudi Arabia are highlighted.

1. Introduction

Order Eulipotyphla, previously known as Insectivora, includes several families (Erinaceidae, Solenodontidae, Talpidae, and Soricidae) [1]. Molecular studies proved the relationships between shrews and hedgehogs [2]. This order is represented by two families, Erinaceidae and Soricidae, known to occur in the Arabian Peninsula [3].

Scattered information is available on the hedgehogs of Saudi Arabia. Previous records were outlined by Harrison and Bates [3]. Paraechinus hypomelas’ presence was based on a single specimen collected near Taif [3]. The presence of Hemiechinus auritus was reported in the eastern province [4,5] some 50 years ago, and later from Al Majma’h and Malhem [6]. The distribution and the taxonomic status of Paraechinus hypomelas in the Arabian Peninsula was outlined by Nader [7]. Paraechinus aethiopicus was reported across the extreme deserts of Saudi Arabia, and its distribution was discussed by Harrison and Bates [3] based on old, documented records.

Little is known about the shrews of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Peninsula. Five species of shrews have been reported in the Arabian Peninsula: Suncus etruscus (Savi, 1822), Suncus murinus (Linnaeus, 1766), Crocidura arabica (Hutterer and Harrison 1988), Crocidura suaveolens (Pallas, 1811), and Crocidura dhofarensis (Hutterer and Harrison, 1988) [3]. The conservation of insectivores in Saudi Arabia has never been addressed in previous publications. One publication concerned with haemorrhagic fever viruses included erroneous records for Suncus murinus from a rural area 55 km west of Riyadh, while, in fact, they were Rattus rattus, as depicted in the figures [8].

The present study updates the taxonomy and distributional data for three species of hedgehogs and three shrews based on previous records and the recent results of field work, with a new record of the Dhofar white-toothed shrew, Crocidura dhofarensis, in Saudi Arabia, addresses their zoogeographical affinities, and identifies threats affecting their populations.

2. Materials and Methods

Distributional Data

Previous records for the insectivores of Saudi Arabia were extracted from published papers, reports, and the mammals collection of the late Prof. Iyad Nader, deposited at the National Center for Wildlife (NCW). Additionally, personal observations of insectivores recovered from owl pellets and from trapping in different sites in Saudi Arabia by the NCW field biologists over the past three years (2022–2024) are included. Data on the insectivores’ distribution cover 73 localities (Appendix A). Records for each species reported previously are indicated with the reference number in parentheses. Scientific and common names were verified according to Mittermeier and Wilson [1].

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of the Insectivore Fauna of Saudi Arabia

The insectivores of Saudi Arabia consist of six species in two families: Erinaceidae and Soricidae. The hedgehog family, Erinaceidae, is represented by three species in two genera (Hemiechinus and Paraechinus), while shrews consist of three species in two genera (Crocidura and Suncus).

3.2. Family Erinaceidae

This family includes the hedgehogs. They are characterised by the presence of spines that cover the dorsal and lateral aspects of their body. The tail is short and stumpy. Eyes are rather small but well developed. Hedgehogs are nocturnal animals. They remain in sheltered areas for most of the day and become active by dusk, when they seek small animals as prey (insects and lizards). Some species hibernate during winter. Hedgehogs are the most primitive mammals of Saudi Arabia. They originated in Africa about 20 million years ago and have not changed from their ancestors. Some became well-adapted to living in the arid regions of the Middle East [9]. Three species of hedgehogs have been reported from Saudi Arabia, representing two genera: Hemiechinus and Paraechinus.

Figure 1.

The long-eared hedgehog, Hemiechinus auritus, from Al Majma’h. (Photo by K. Al Malki).

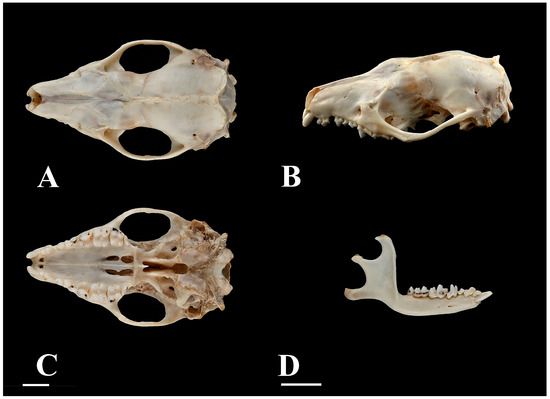

Figure 2.

Cranial morphology of the long-eared hedgehog, Hemiechinus auritus. (A) Dorsal view. (B) Lateral view. (C) Ventral view. (D) Lower mandible. Scale bar = 1 cm. (Photo by K. Al Ajmi).

Common name: Long-eared hedgehog

Arabic name: القنفذ طويل الأذن

Global distribution: Eastern Mediterranean region, through southwest Asia to western Pakistan in the south and from eastern Ukraine through Mongolia to China.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia: Figure 3

Figure 3.

Distribution of three hedgehog species in Saudi Arabia. (NCW).

Previous records: Abu Hadriyah, Dharan, Safaniyah [4], Ras al Abkhara [5], Al Majma’h, Al Mulhem [6].

Diagnosis: Smallest species of hedgehogs in Saudi Arabia. The presence of very long and pointed ears is a distinctive feature of this hedgehog. The ears are not covered by hair. The tips of the dorsal spines are white. The base of the scapular spines is black. A gap in the forehead spines is lacking. The face has white hair and a little brown hair around the eyes, but without a facial mask. The muzzle has a grey tint. The belly buff is white. Four to five pairs of mammae are present in the female. They have a small and delicate skull and large tympanic bullae. The first upper incisors are pointed forward, with elevated crowns of the lower second premolar bicuspids.

Habitat and ecology: Specimens from Saudi Arabia were collected around the coastal eastern province. It avoids extreme desert habitats, and in the Eastern Mediterranean, it is associated with forests and Irano-Turanian regions [10]. In the Arabian Peninsula, its distribution extends from Kuwait, reaching as far as Bahrain [11]. This species was recently recorded in Al Majma’h [6]. This site is an agricultural area with watermelons, tomatoes, berries, and palm trees. Wells are abundant and used for irrigating crops and trees. The soil is hard and compact with an abundance of Egyptian spiny-tailed lizard, Uromastyx aegyptia, burrows. Other mammals observed include the desert hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus. This record expands the range of the long-eared hedgehog deep into central Saudi Arabia, about 400 km to the east of the coastal eastern province, suggesting its occurrence along the eastern part of the country between the Arabian Gulf and the Arabian Shield mountains. It also confirms the continuous presence of a viable population for almost 50 years, since it was recorded by Pitcher [4].

Biology: Very little is known about its ecology in Saudi Arabia. Gestation lasts for about 37 days, and the newborns are hairless but with soft spines [10]. Young are born in March [4]. Remains of the long-eared hedgehog were recovered from owl pellets near Al-Jubial [5]. It feeds on various insects, centipedes, and land snails [12]. This species digs burrows or seeks refuge in depressions under stones.

Figure 4.

The Ethiopian hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus. (NCW archives).

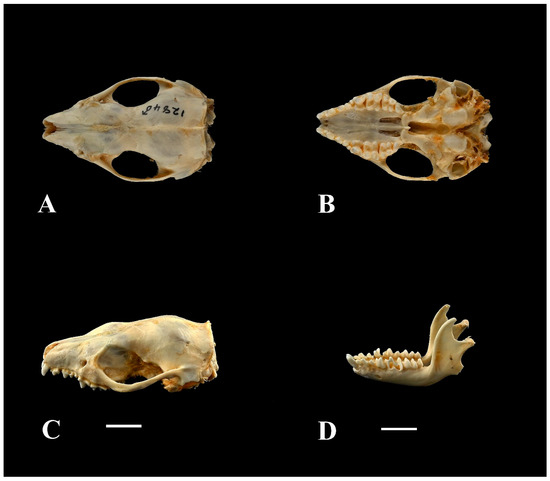

Figure 5.

Cranial morphology of the Ethiopian hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus. (A) Dorsal view. (B) Ventral view. (C) Lateral view. (D) Lower mandible. Scale bar = 1 cm. (Photo by K. Al Ajmi).

Common names: Desert hedgehog, Ethiopian hedgehog.

Arabic name: القنفذ الاثيوبي

Global distribution: Sahara from Mauritania to Egypt and Awash, Ethiopia; Arabian deserts; insular populations in Djerba (Tunisia), Jordan, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia: Figure 3

Previous records: Al Qaseem [13], Taif, 80 km W Al Juf, Jabrin, Hasa, 96 km N Qunfida, Buraidah, Rafha, Hail, Hofuf, Mecca bypass [3], Riyadh Province [14], Al Majma’h, Badaya, Buraidah, Ghamas, Mlida, Muznab, Riyadh, Shmasya, Um Sedra, Unizah [15], Al Adare, Al-Madinah Al-Munawwarah, Al-Ula, Khaybar, Sakaka [16], Turaif [17]. Unizah [18,19], Thumamah [20], Ara’r [21], Bsitah, Al Daba’ah [22].

Recent records: Al Ra’an, Habaka, Luga, Roudah, Wadi Jalil.

Material examined from the Prof Iyad Nader collection:

IN003, ♀ (Skin), Al Kharj, 21.6.1975, leg. I. Nader. IN439, ♀ (Skin), ad Dir’iyah, 11.5.1972, leg. I. Nader. IN560, ♀ (Skin and skull), ad Dir’iyah, 19.5.1974, leg. I. Nader. IN589, ♂ (Skin and skull), Al Wadiain, 11.4.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN591, ♀ (Skin and skull), Jeddah, 8.11.1974, leg. I. Nader. IN611, ♀ (Skin), Hakima, 5.10.1975, leg. I. Nader. IN612, ♀ (Skull), 7 km W Abu Arish, 5.10.1975, leg. I. Nader. IN676, ♂ (Skin and skull), Al Gayah about 28 km SE Abha, 1.3.1977, leg. I. Nader. IN677, ♀ (Skin and skull), Ahad Rufaida, 2.6.1977, leg. I. Nader. IN711, Al Sauda, 25.4.1977, leg. I. Nader. IN804, ♂ (Skin and skull), Wadi Bin Hashbal, 7.31980, leg. I. Nader. IN1015, ♀ (Skin and skull), 15 Km N Khamis Mushait, 22.11.1977, leg. K. Khalily. IN1016, Wadi Dalaghan, 24.6.1981, leg. I. Nader. IN1066, ♂ (Skull), N Abha, al Souda road, 4.2.1984, leg. I. Nader. IN1071, ♂ (Skin and skull), SW Ahad Rufaida, 26.1.1985, is leg. I. Nader. IN1069, ♂ (Skin and skull), Hijla, 15.3.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1065, ♀ (Skin and skull), Tihamaht Asir, 29.3.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1066, ♂ (Skin), Abha, Al Sauda, 30.3.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1067, ♂ (Skin), Abha, Al Sauda, 1.5.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1070, ♂ (Skin), Hijla, 2.4.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1071, ♂ (Skin and skull), Ahad Rufaida, 26.6.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1085, khamis mushait, 26.4.1975, leg. I. Nader. IN1089, ♀ (Skull), Abha, 30.11.1985, leg. I. Nader. IN1118, ♂ (Skin and skull), Abha, 2.3.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1115, ♂ (Skin and skull), Abha, 27.4.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1116, ♂ (Skin and skull), Abha, 9.3.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1125, ♀ (Skin and skull), Abha Al Mahala, 17.4.1986, leg. M. I. Ali. IN1126, ♂ (Skin and skull), Abha, 28.4.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1138, ♂ (Skull), Jazan, 12.10.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1139, ♀ (Skin and skull), Abha, 28.11.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1151, ♂ (Skin), Al Wadiain, 17.3.1987, leg. I. Nader. IN1157, ♂ (Skin and skull), SW Abha, 8.6.1987, leg. I. Nader. IN1138, ♂ (Skin), Jizan, 12.10.1986, leg. I. Nader. IN1141, ♀ (Skin), Alwasely Jizan, 11.12.1987, leg. I. Nader. IN1142, Abha, 17.2.1987, leg. I. Nader. IN1150, ♀ (Skin and skull), Al Wadiain, 14.3.1987, leg. I. Nader.

Diagnosis: Medium-sized hedgehog. The ears are large, slightly rounded at the tips, and extend beyond the upper surface of the spines. There are dark terminal ends of the dorsal spikes. The anterio-median gap of spines on the head is a distinguishing characteristic of this species. The ventral side is pure white, and the legs and feet are dark brown. It possesses a distinctive facial mask, the muzzle being dark grey to black; otherwise, the face is white from the eyes to the forehead. This animal is much lighter in colour than other hedgehogs in Jordan; both the bases and tips of the spines are white. Its fur is fine and dense. The skull is robust and broad, with a wide braincase. Strongly inflated tympanic bullae, with their cavities extending into the pterygoids.

Habitat and ecology: This is a true desert species adapted to survive in arid habitats. Most of the localities indicated are extreme desert habitats ranging from black lava to sand to gravel deserts. It is very common in Wadi Jalil near Jeddah, where it occurs in high numbers during early winter. It was found to be associated with farms in the northern and central parts of the country.

Biology: Mohammad [15] found that this species feeds on plants and cultivated crops, insects, mammals, birds, and worms, as well as cooked rice from the garbage. Moniliformis saudi, an acanthocephalan worm, was described from the Ethiopian hedgehog collected from the Unaizah area [18]. Cranial remains of this species were recovered from the Pharaoh eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, pellets from three localities in Saudi Arabia [21,22]. The karyotype was studied, and it has 2n = 48, fundamental number 96, 15 metacentric, and 9 submetacentric [13].

Hibernation is triggered by low ambient temperature around 13° C and lasts for 1.5 months during January and February in Qatar [23]; however, it was observed basking during the daytime in winter [24]. Breeding activities were reported to occur in March in Qatar [23]. Yamaguchi et al. [25] proposed that this species in Qatar has two mating periods: one during February/March and a second in June; thus, it breeds more than two times per year. The first rains trigger the onset of reproductive activation in females, and pregnancies occur in early spring and summer [19]. It was reported to hibernate during winter but awakens every few days to feed [26]. Females may produce two to three litters per year [26]. The dog tick, Ripicephalus sanguineus, was collected from this species at Thumamah [20].

Figure 6.

Brandt’s hedgehog, Paraechinus hypomelas. (NCW archives).

Figure 7.

Cranial morphology of Brandt’s hedgehog, Paraechinus hypomelas. (A) Lateral view. (B) Ventral view. (C) Dorsal view. (D) Lower mandible. Scale bar = 1 cm. (Photo by K. Al Ajmi).

Common Name: Brandt’s hedgehog

Arabic name: قنفذ براندت

Global distribution: Iran, E Iraq, SW Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, W Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Uzbekistan, Yemen, islands of Tanb and Kharg.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia: Figure 3

Previous records: N Abha, Al Sarhan, Al Masgi, An Namas, Bani Razzam, Belad Bel Asmar, Biljurshi, Wadi Bahwan, Wadi Bin Hashbel, Hijla, [7], Taif [3], and Al Baha [16].

Recent records: Ashayrah, Sabya, and Wadi Lajab.

Diagnosis: Medium-sized hedgehog. The ears are large and narrower across their base compared to P. aethiopicus. The ears are covered by fine white hair. A bare median gap is well developed on the forehead, reaching about 2 cm long and 6.5 mm wide. Spines have longitudinally grooved nodose. The spines are uniform in colour with black-brown colouration. Spines terminate with a dark brown tip about 1 cm long and without a white tip, as those in P. aethiopicus. The hair is very dark, with the face sooty to blackish-brown in colour, with few white hairs intercepted on the forehead. The throat has creamy-white hairs. The ventral side is usually sooty to blackish-brown in colour.

Habitat and ecology: This species inhabits mountains reaching up to 2380 m asl and semi-arid areas of Saudi Arabia and avoids extreme deserts [7]. Elsewhere, it was found in arid regions with gravelly slopes or rocky areas.

Biology: In Saudi Arabia, females give birth to one to three young in April and May [7]. Elsewhere, it feeds on a variety of insects, including grasshoppers, locusts, and beetles, as well as scorpions. It is also known to feed on the eggs of birds, fruits, and watermelons. Newborns can be seen during April–May, and females give birth to three to four young [1].

Taxonomic remarks: Nader [7] recognised three subspecies of Brandt’s hedgehog in the Arabian Peninsula: Paraechinus hypomelas seniculus (Thomas, 1922), described from Tanb Island, Arabian Gulf; Paraechinus hypomelas niger (Blanford, 1878), from Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen; and Paraechinus hypomelas hypomelas (Brandt, 1836).

3.3. Family Soricidae

This family includes the shrews, identified by their long, narrow, and pointed snout. Shrews are the smallest living mammals, where some species do not exceed 4 cm long and weigh 2 g. So far, about 400 species have been described [1]. They have short legs, with five toes per foot. Shrews are known for their extremely high metabolic rate as well as rapid heart rate that may reach up to 450 beats per minute. They feed on insects, earthworms, and larvae. Shrews of Saudi Arabia are represented by three species belonging to two genera: Crocidura and Suncus.

Crocidura gueldenstaedtii (Pallas, 1811) Figure 8

Figure 8.

Adult Pallas’s white-toothed shrew, Crocidura gueldenstaedtii from Al Far’ah farms (Photo by A. Aloufi).

Common name: Pallas’s white-toothed shrew

Arabic name: زبابة بالاس بيضاء الاسنان

Global distribution: Central and western Europe (Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, North Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Austria, Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal) and southwestern Asia (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt (Sinai), west Jordan, north Iraq, northwest Iran, and north Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia: Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Distribution of three species of shrews in Saudi Arabia. (NCW).

Previous records: Bani Mashoor [27].

Recent records: Abha, Al Far’ah farms.

Diagnosis: Body length is 88 mm. The bicoloured tail is dark and long, more than half the length of the head and body. Fur colour is brownish-grey dorsally, and the ventral colour is lighter. No sharp line on the flanks separates the dorsal and ventral aspects. The upper jaw has three unicuspid teeth.

Habitat and ecology: This species was reported in the mountains of southwestern Saudi Arabia at an altitude reaching up to 2500 m a.s.l. In Al Baha, it was found on a farm with cultivated vegetables and almond trees. It prefers humid areas with relatively dense vegetation cover that may attract arthropods. The coordinates (22°50′ N, 42°09′ E) given by Bates and Harrison [28] for “Bani Mashoor” seem to be erroneous; it is located east of Rabigh in a flat arid desert surrounded by black lava mountains. In Saudi Arabia, two localities carrying the same name are known: “Bani Mashoor”, Al Baha area (19°58′ 31.13″ N. 41°31′57.39″ E) located in mountainous area with lush and dense vegetation and abundance of trees, and “Bani Mashoor”, An Namas (19°05′5.96″ N, 42° 07′ 50.31″ E) with a similar habitat as that for the Al Baha area. At the Al Far’ah farms (Yanba’ an Nakhal), this species was collected from agricultural areas situated between wadi systems with an abundance of permanent springs. It was found in shady areas under palm trees, irrigated by the traditional method of flooding water. The soil is always relatively moist. Other vegetable crops, grapes, and citrus trees are widespread (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Habitat of Crocidura gueldenstaedtii at Al Far’ah farms (Yanba’ an Nakhal). (Photo by A. Aloufi).

Biology: Hellwing [29] gave an account of the breeding of this species in captivity, with an average gestation period of about 29 days. The litter size ranges from one to seven, with an average of three. Specimens collected from Jordan contained a single embryo [30].

Taxonomic remarks: Pallas’s white-toothed shrew was until recently regarded to be conspecific with C. suaveolens; the two have been separated on the basis of molecular evidence. C. suaveolens, with its restricted scope, occupies Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, northeast Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, north Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, northwest China, and western Mongolia. Their borders in the zone of contact are known only tentatively. In the past, C. gueldenstaedtii was reported as C. russula (e.g., specimens from Bani Mashoor in Bates and Harrison [28]), although the two shrews are not closely related.

Figure 11.

Crocidura dhofarensis from Baish. (A) Lateral view of adult specimen. (B) Lateral view of the tail. (C) Lateral view of the head region. (Photo by B. Kryštufek).

Figure 12.

Crocidura dhofarensis. (A) Adult Crocidura dhofarensis. (B) Ventral view of the hind foot. (C) Ventral view of the forefoot. (D) Frontal view of a living specimen showing its large ears. (Photo by S. Al Jbour).

Figure 13.

Cranial morphology of C. dhofarensis from Baish, Saudi Arabia. (A) Dorsal view. (B) Ventral view. (C) Lower jaw (Scale bar 15 mm). (D) Lateral view (Scale bar = 5 mm). (Photo by David Kunc).

Common name: Dhofar white-toothed shrew.

Arabic name: زبابة ظفار بيضاء الأسنان

Global distribution: Oman, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia: Figure 9.

Material examined: (1) 1 June 2023. Baish, Jazan Governorate, leg. A-R. Al Ghamdi and K. Al Malki (Sent to B. Kryštufek). (4—2 adults and 2 subadults) 25 July 2023. Baish, Jazan Governorate.

Diagnosis: Pelage is dark brown on the dorsal side and light grey ventrally; delimitation on the flanks is distinct though not sharp. The chin is covered with short white hair. The tail is indistinctly bicoloured: grey-brown dorsally and light grey ventrally. It has long hairs loosely scattered over the entire tail except its terminal portion. The fore and hind feet are covered by brown hair; the claws are whitish. The skull is slender, and the rostrum is narrow and elongated compared to other shrews in Arabia. It differs from other shrews of the genus Crocidura by having a concavity in the lambda in the posterior end of the skull.

Comparison of our voucher from Baish with the description of the type [27] and two vouchers from Yemen (NMP 2957 and NMP 2958; [31]) revealed no noteworthy differences, and cranial dimensions largely overlap. Some of the differences between the type (measurements from Hutterer and Harrison 1988 [27]) and vouchers from Saudi Arabia and Yemen (measured by one of this article’s researchers) may reflect inconsistency in scoring measurements.

Dimensions in mm (Baish skull; two skulls from Yemen; the type): Condyle–incisive length of skull 18.81; 18.94; 18.54; 20.2; condylobasal length of skull 18.07; 18.01; 18.07;/; basal length 17.26; 17.30; 16.86; 18.5; palatal length 8.63; 8.76; 8.38; 8.5; length of maxillary tooth row (alveolar) 8.04; 8.37; 7.76; 8.6; infraorbital width 3.27; 3.36; 3.52; bimaxillary width 5.46; 5.64: 5.53; 5.7; least interorbital width 4.02; 3.73; 3.73; 3.8; width across pterygoids 2.48; 2.08; 2.31; greatest width of skull 8.26; 8.06; 8.07; 8.5; height of rostrum behind 3rd molar 3.44; 3.36; 3.35;/; posterior median height 4.56; 4.00; 4.19; 4.5; length of mandible (incisor—articular process) 11.27; 11.47; 11.27; length of mandibular tooth row (alveolar) 8.55; 7.22; 7.16; 7.7; and coronoid process height 4.53; 4.37; 4.50; 5.0.

Habitat and ecology: Specimens were collected from a banana farm at 63 m a.s.l. in Baish, Jazan Governorate. The area is an orchard cultivated with banana and rich in irrigation canals (Figure 14). It extends for a few kilometres to the east of Jazan. Other mango and vegetable farms are situated around the collection site. Only the house mouse, Mus musculus, was trapped, along with C. dhofarensis.

Figure 14.

Habitat of C. dhofarensis in Baish, Jazan Governorate. (Photo by A-R. Al Ghamidi).

Remarks: This is the first record of C. dhofarensis in Saudi Arabia. The Dhofar white-toothed shrew was originally described in Khadrafi, Dhofar, Oman [27] and later recorded in Hawf, Al Mahra Province, Yemen [31]. It is considered endemic to the Arabian Peninsula. It was originally treated as a subspecies of Crocidura somalica dhofarensis (Hutterer and Harrison, 1988). It differs from Crocidura somalica in several characteristics, including the dark brown colour of the ventral pelage, the colour of the dorsal surface of the hands and brown feet, unicoloured tail, and the narrower facial part of the skull [27]. These differences warrant raising Crocidura dhofarensis as a separate species confined to the Arabian Peninsula [32].

Figure 15.

Female Suncus murinus from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Iyad Nader collection at NCW (Scale bar = 2 cm). (Photo by S. Al Jubor).

Figure 16.

Cranial remains of S. murinus recovered from barn owl pellets. (A) Lateral view. (B) Ventral view. (C) Right lower mandible (Scale bar = 1 cm). (Photo by S. Al Jubor).

Common name: Asian House Shrew.

Arabic name: زبابة المنزل الاسيوية

Global distribution: This species is native to South and Southeast Asia and was introduced to East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia (Figure 9).

Previous records: Jeddah [28].

Recent records: Al Qatif, skulls collected from barn owl pellets.

Materials examined: IN583, ♀, Jeddah, 3.12.1974, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN595 ♂, Jeddah, 3.2.1975, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN678, ♀, Jeddah, 29.3.1979, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN679, ♀, Jeddah, 29.3.1979, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN680, ♀, Jeddah, 29.3.1979, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN725, ♂, Jeddah, 1.9. 1978, leg. J. Gasperetti. IN726, ♂, Jeddah,1.9.1978, leg. J. Gasperetti.

Diagnosis: Large in size, it can reach up to 25 cm. The tail is short and thick, tapering towards the end. The tail has rings formed from epidermal scales. The ears are round and short. Dorsal pelage is short, fine, dense, and brown-greyish in colour. The ventral side has light grey hair. The skull is large, reaching up to 35 mm, narrow, and elongated. The sagittal ridge is prominent, and the lambdoid crest projects beyond the supraoccipital. The infraorbital foramina are large; the anterior palatine foramina are small. The mesopterygoid space is pear-shaped and wider posteriorly. The incisors are large, hook-shaped, and consist of large principal and small secondary lobes. Of the four upper unicuspid teeth, the first is the largest, while the fourth is the smallest and sometimes missing, but with remnants of its socket.

Habitats and ecology: In the Middle East, the Asian house shrew was reported in cities with seaports on the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf, from Bahrain, southern Iraq, Oman, and Yemen [3,33]. It is believed that it was introduced via goods imported by sea. It was not reported in any locality in the mainland of Arabia. The Asian house shrew was found among garbage dumps, gardens, and houses around seaports [3]. Detailed distribution in Arabia and Africa, and the possibility of its dispersal through ships, was discussed by Hutterer and Tranier [33].

Biology: It was reported that this shrew is active and more abundant during May. A pregnant female was found in January, and a lactating female with three embryos was observed in May [3]. This species breeds all year in its natural habitats. The Asian house shrew is known to be loud, emitting squeaking sounds as an aggressive behaviour. A total of 23 skulls were recovered from pellets of the barn owl, Tyto alba, at Al Qatif.

Remarks: The Asian house shrew has been recorded by Al Qurna and Fao [34], Basrah [35], Chebaeish [36], and Hammar Marsh [37] in Iraq, Muscat, and Oman [38], north of Hodeida [39], Bajil [40], and Al-Haswa [41] in Yemen and Bahrain [42], and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia [28]. This finding in the eastern province extends its known range in Saudi Arabia to the Arabian Gulf.

Morphometric measurements were recorded for specimens from Jeddah in the collection of Dr. Iyad Nader (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body measurements for Suncus murinus specimens collected from Jeddah.

3.4. Zoogeographical Affinities of Insectivores in Saudi Arabia

The zoogeography of the mammals of the Arabian Peninsula was presented by Delany [43]. His discussion was based on distributional data obtained before 1989 (Table 2). Recent studies expanded the known range for several species, which now allows us to discuss in detail the zoogeographic affinities of the insectivores of Saudi Arabia.

Table 2.

Zoogeographical affinities of the insectivores of Saudi Arabia.

Two species of shrews, C. dhofarensis and C. arabica, are considered endemic to the Arabian Peninsula. Their distribution is confined to southern Arabia and southwestern Saudi Arabia. Crocidura dhofarensis exhibited some similarities with its neighbouring African species, Crocidura somalica. C. gueldenstaedtii presence in Saudi Arabia represents relic populations scattered along the western highlands, and it is believed to survive in humid environments along the western mountain ranges. Suncus murinus represents introduction, as it is believed that this shrew originated from tropical Asia [44]. This shrew is now widespread along seaports of the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa, and Madagascar, and its distribution coincides with the Dhow route of Arabian trade ships [33].

Both H. auritus and P. hypomelas are considered Palaearctic species. The long-eared hedgehog, H. auritus, is distributed across the Middle East, former southern states of the former Soviet Union, reaching as far as China to the east, and coastal areas of Egypt and Libya to the west [1]. Brandt’s hedgehog, P. hypomelas, is widely distributed in Iran, Iraq, Turkmenistan, N Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Yemen, but is restricted to the southern parts of the Arabian Peninsula [1]. Paraechinus aethiopicus is considered a Palaearctic–Afrotropical species. It has a wide range of distribution, extending from Iran in the east, across the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula, reaching the Western Sahara [1].

The southwestern corner of Saudi Arabia, covering Asir, Jazan, and extending further into the Al Sarawat mountains, hosts the highest number of insectivore species (three species). This includes two species of shrews, the endemic C. dhofarensis and C. gueldenstaedtii, and one hedgehog species, P. hypomelas. This area represents the Afromontane element characterised by rich vegetation cover, relatively high humidity and rainfall, and an abundance of permanent water bodies.

The Ethiopian hedgehog, P. aethiopicus, has the widest range of distribution in open desert areas, avoiding the mountainous areas to the west. The long-eared hedgehog is primarily confined to east-central and eastern Saudi Arabia, overlapping with P. aethiopicus in the east and around central and eastern Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, the Afromontane region of Saudi Arabia was found to host the highest diversity of bats [45].

It highly possible to find the Arabian white-toothed shrew, Crocidura arabica, in areas around Jazan. This species was reported from Yemen and Oman [27]. It shows a similar distribution range as C. dhofarensis [27].

3.5. Conservation Status of the Insectivores of Saudi Arabia

Table 3 summarises the conservation status of insectivores of Saudi Arabia according to the global, regional, and national levels. Among the species of insectivores of Saudi Arabia, C. dhofarensis, is listed as data deficient at the global and regional levels [46]. This species was collected from a single locality near Jazan, in the extreme southwest of Saudi Arabia.

Table 3.

Conservation status of insectivores of Saudi Arabia according to the global, regional, and national levels.

At the national level, the status of H. auratus requires more validation, since it was reported from few localities. The conservation status of all shrews is not clear yet, pending further collecting and investigation.

3.6. Threats Affecting the Insectivores of Saudi Arabia

Hedgehogs in general are threatened by urban expansion, habitat loss and degradation, and road construction across their habitats. Hedgehogs were among the most frequent casualties encountered along highways and secondary roads as road kills, especially P. aethiopicus [47]. During early spring, individuals are killed on highways and roads across the country. Additionally, they are offered for sale as pets in open animal markets in many towns and cities in Saudi Arabia. Trade in hedgehogs was documented in Morocco and several countries for medicinal purposes or as food [48]. Shrews are affected by urban expansion within their very restricted habitats and overgrazing of grassland and woodland by livestock [46]; however, they benefited from agricultural expansion, as farms provide humidity and ample source of arthropod food sources. In the Jazan area, C. dhofarensis was found in relatively high numbers on banana farms.

4. Discussion

The present study documents the insectivore fauna of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with a total of six extant species, and a possible additional shrew, C. arabica. In comparison to the surrounding countries on the Arabian Peninsula, this number is relatively high, with the presence of at least two endemic species. A total of seven extant species of insectivores have been recorded from Iraq [35,49,50], five from Jordan [10], three from Bahrain [3,51], three from Kuwait [52], one from Qatar [3], three from the United Arab Emirates [53], six from Oman [3,27], and eight from Yemen [41].

Hedgehogs are desert-adapted species, particularly P. aethiopicus, which is the most common species, with a large distribution range across the Arabian Peninsula. The distribution of P. hypomelas requires further investigation to understand its fragmented distribution in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Nader [7] suggested that three subspecies of Brandt’s hedgehog occur in the Arabian Peninsula, and that P. h. hypomelas (Brandt, 1836) is distributed in Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Yemen.

The shrews of Saudi Arabia remain largely unknown in terms of distribution and taxonomy. The western mountains of the Red Sea may offer suitable habitats within enclaves with high humidity and agricultural fields. It was brought to our attention that there were sightings of “mice with a long snout” from areas west of Al Madinah, with images of what seems to be C. gueldenstaedtii. Such reports require scrutiny and field studies to confirm their presence. The presence of the Arabian white-toothed shrew, C. arabica, is investigatable through extensive surveys in the southwestern corner of Saudi Arabia.

Indeed, recent data and field studies showed that the distribution of the long-eared hedgehog, H. auritus, extended further, to the west of eastern Saudi Arabia [6]. This was mainly due to recent fieldwork. On the other hand, the two other species of hedgehogs were confined to previously known habitats, but with additional locality records.

As indicated, additional locality records for C. gueldenstaedtii are attributed to more extensive field work in previously unstudied areas. The record of Crocidura dhofarensis represents a new record for Saudi Arabia based on extensive studies in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Recently, additional locality records for the Asian house shrew, S. murinus, was recorded from the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, where it was recorded over 50 years ago by Jeddah [54].

By and large, further field studies are required to better understand the insectivore fauna of Saudi Arabia, along with adding additional locality records identifying habitat preference for shrews and threats that may affect their populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S.A., B.K. and A.R.A.G.; methodology and data collection, A.R.A.G., K.A.A.M., F.N., A.A., A.A.A.S., N.A.Q., S.A.J. and A.A.B.; result analysis, Z.S.A., B.K., F.N., A.R.A.G., K.A.A.M. and N.A.Q. writing, Z.S.A., B.K., A.A.B., S.A.J. and A.R.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Center for Wildlife (NCW), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are presented in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mohammad Al Nashiri and Abdul Majeed Alaqil from the GIS unit (NCW) for the preparation of maps, and Kama’an Al Ajmi for photography of skulls The authors wish to express their gratitude to Mohammed Qurban, CEO of NCW, for his continuous support and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Locality | N | E | Locality | N | E |

| Abha | 18°14′00″ | 42°31′00″ | Ghamas | 26°13′31″ | 43°53′26″ |

| Abu Hadriyah | 27°05′00″ | 49°00′00″ | Habaka | 29°30′05″ | 42°08′22″ |

| ad Dir′iyah | 24°44′45″ | 46°31′38″ | Hail | 27°31′00″ | 41°45′00″ |

| Afif | 23°54′32″ | 42°54′37″ | Jazan | 16°53′21″ | 42°34′14″ |

| Al Ahsa | 25°33′16″ | 49°46′36″ | Hakima | 17°0′36″ | 42°50′03″ |

| Al Adare | 30°10′00″ | 40°10′00″ | Hasa | 25°23‘08″ | 49°32′15″ |

| Al Baha | 19°35′54″ | 41°45′40″ | Hijla | 18°15′00″ | 42°38′00″ |

| Al Daba′ah | 28°44′03″ | 37°58′23″ | Hofuf | 25°20′00″ | 49°34′00″ |

| Al Gayah | 21°28′17″ | 39°26′09″ | Jabrin | 23°15′42″ | 48°58′51″ |

| Al Far′ah farms | 18°50′51″ | 42°00′21″ | Jeddah | 21°51′00″ | 39°07′00″ |

| Al Jawf | 29°52′22″ | 36°26′05″ | Khamis Mushait | 18°16′20″ | 42°46′14″ |

| Al Kharj | 24°09′27″ | 47°19′29″ | Khaybar | 24°59′00″ | 39°55′00″ |

| Al Madinah | 24°49′07″ | 39°23′44″ | Luga | 29°46′00″ | 42°38′00″ |

| Al Majmaah | 22°04′00″ | 40°01′00″ | Makkah bypass | 21°26′00″ | 39°71′00″ |

| Al Masgi | 18°02′22″ | 42°43′31″ | Mlida | 26°19′55″ | 43°48′31″ |

| Al Mulhem | 25°16′00″ | 46°32′00″ | Muznab | 25°50′55″ | 44°12′28″ |

| Al Namas | 19°09′07′′ | 42°09′26″ | Qunfida | 19°09′00″ | 41°07′00″ |

| Al Qaseem | 25°40′08″ | 41°43′28″ | Rafha | 29°36′00″ | 43°32′00″ |

| Al Qatif | 26°34′35″ | 49°59′53″ | Ras al Abkhara | 27°24′00″ | 49°14′00″ |

| Al Ra′an | 26°51′60″ | 43°22′60″ | Riyadh | 24°39′00″ | 46°46′00″ |

| Al Sarhan | 18°16′00″ | 42°22′00″ | Roudah | 25°38′54″ | 44°12′21″ |

| Al Sauda | 18°16′19″ | 42°23‘07″ | Sabya | 17°07‘00″ | 42°39′00″ |

| Al-Ula | 26°36′10″ | 37°55′46″ | Safaniyah | 27°56′26″ | 48°39′46″ |

| Al Wadiain | 18°05′49″ | 42°48′57″ | Sakaka | 30°10′00″ | 40°20′00″ |

| Alwasely | 16°56′52″ | 42°41′34″ | Al-Shamasiyah | 25°41′53″ | 44°37′34″ |

| Ahad Rufaida | 18°11′42″ | 42°49′13″ | Taif | 21°31′12″ | 40°35′19″ |

| Ara′r | 30°57′35″ | 41°03′34″ | Thumamah | 25°22′00″ | 46°36′00″ |

| Ashayrah | 21°39′00″ | 40°38′00″ | Tihamaht Asir | 18°31′37″ | 42°03′55″ |

| Badaya | 25°59′59″ | 43°42′00″ | Turaif | 31°39′57″ | 38°39′48″ |

| Baish | 17°22′26″ | 42°32′10″ | Um Sedra | 25°49′50″ | 45°17′13″ |

| Bani Mashoor | 19°58′31″ | 41°31′57″ | Unizah | 26°05′00″ | 43°59′00″ |

| Bani Razzam | 18°35′00″ | 42°46′00″ | Wadi Bahwan | 18°41′42″ | 42°25′06″ |

| Belad Bel Asmar | 18°46′58″ | 42°10′08″ | Wadi Dalaghan | 18°06′04″ | 42°42′18″ |

| Biljurashi | 19°49′28″ | 41°37′25″ | Wadi Bin Hashbel | 18°34′57″ | 42°40′06″ |

| Bsitah | 30°44′20″ | 38°31′01″ | Wadi Jalil | 21°27′41″ | 39°50′49″ |

| Buraydah | 26°20′00″ | 43°59′00″ | Wadi Lajb | 17°36′17″ | 42°55′51″ |

| Dharan | 26°18′00″ | 50°05′00″ |

References

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Wilson, D.E. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8. Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; 709p. [Google Scholar]

- Douady, C.J.; Chatelier, P.I.; Madsen, O.; de Jong, W.W.; Catzeflis, F.; Springer, M.S.; Stanhope, M.J. Molecular phylogenetic evidence confirming the Eulipotyphla concept and in support of hedgehogs as the sister group to shrews. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2002, 25, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.L.; Bates, P.J.J. The Mammals of Arabia, 2nd ed.; Harrison Zoological Museum Publication: Kent, UK, 1991; 354p. [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher, D.A. The long eared hedgehog of Arabia. J. Saudi Arab. Nat. Hist. Soc. 1976, 16, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, D.; Nader, I. Terrestrial mammals of the Jubail Marine Wildlife Sanctuary. In A Marine Wildlife Sanctuary for the Arabian Gulf: Environmental Research and Conservation Following the 1991 Gulf War Oil Spill; Krupp, F., Abuzinada, A.H., Nader, I.A.A., Eds.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1996; pp. 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Al Malki, K.; Al Obaid, A.; Shuraim, F.; Al Boug, A.; Amr, Z.S. Further records of the Long-eared Hedgehog, Hemiechinus auritus (Gmelin, 1770), in Saudi Arabia. Jordan J. Nat. Hist. 2023, 10, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nader, I.A. Paraechinus hypomelas (Brandt, 1836) in Arabia with notes on the species zoogeography and biology (Mammalia: Insectivora: Erinaceidae). Fauna Saudi Arab. 1991, 12, 400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, R.A.E.H.; Aleanizy, F.S.; Alqahtani, F.Y.; Alhmoaidi, E.A.; Mohamed, N. Detection of some haemorrhagic fever viruses in wild shrews collected from different habitats in Saudi Arabia: First record in the Middle East. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, P. Desert Specialists: Arabia’s elegant mice. Arab. Wildl. 1996, 2, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S. The Mammals of Jordan, 2nd ed.; Al Rai Press: Amman, Jordan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalili, A.D. New records and a review of the mammalian fauna of the State of Bahrain, Arabian Gulf. J. Arid Environ. 1990, 19, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, M.; Yom-Tov, Y. The biology of two species of hedgehogs, Erinaceus europaeus concolor and Hemiechinus auritus aegyptius, in Israel. Mammalia 1985, 49, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI-Saleh, A.A.; Khan, M.A. Cytological studies of certain mammals of Saudi Arabia. 3. The karyotype of Paraechinus aethiopicus. Cytologia 1985, 50, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.D.; Al-Mohammed, H.I.; Alyousif, M.S.; Said, A.E.; Salim, B.; Abdel-Shafy, S.; Shaapan, R.M. Species diversity and seasonal distribution of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting mammalian hosts in various districts of Riyadh province. Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Entomol. 2019, 56, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, B. Arthropod-Borne Infections in the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. Ph. D. Thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2018; 197p. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, W.F. Changes in the feeding behavior and habitat use of the desert hedgehog Paraechinus aethiopicus (Ehrenberg 1832, Eulipotyphla: Erinaceidae), in Saudi Arabia. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e244581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paray, B.A.; Al-Sadoon, M.K. A survey of mammal diversity in the Turaif province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, O.M.; Heckmann, R.A.; Mohammed, O.; Evans, R.P. Morphological and molecular descriptions of Moniliformis saudi sp. n. (Acanthocephala: Moniliformidae) from the desert hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus (Ehrenberg) in Saudi Arabia, with a key to species and notes on histopathology. Folia Parasitol. 2016, 63, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Bennett, N.C.; Mohammed, O.B.; Hart, D.W. The reproductive biology of the Ethiopian hedgehog, Paraechinus aethiopicus, from central Saudi Arabia: The role of rainfall and temperature. J. Arid Environ. 2017, 145, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, F.S.; Soares, J.F. Tick survey in Ethiopian hedgehogs (Paraechinus aethiopicus) at Thumamah, Saudi Arabia. Wildl. Middle East News 2014, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Alshammary, T.; Al Gethami, F.; Al Boug, A.; Al Jbour, S.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, from Ara’r region, northeastern Saudi Arabia. Ornis Hung. 2023, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Al Gethami, F.; Abu Baker, M.; Al Atawi, T.; Al Boug, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet composition of the Pharaoh eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, diet across agricultural and natural areas in Saudi Arabia. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e276117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musfir, H.M.; Yamaguchi, N. Timings of hiber0nation and breeding of Ethiopian Hedgehogs, Paraechinus aethiopicus, in Qatar. Zool. Middle East 2008, 45, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Baker, M.A.; Mohedano, I.; Reeve, N.; Yamaguchi, Y. Observations on the postnatal growth and development of captive Ethiopian hedgehogs, Paraechinus aethiopicus, in Qatar. Mammalia 2016, 80, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Al-Hajri, A.; Al-Jabiri, H. Timing of breeding in free-ranging Ethiopian hedgehogs, Paraechinus aethiopicus, from Qatar. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 99, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qumsiyeh, M.B. Mammals of the Holyland; Texas Tech. University Press: Lubbock, TX, USA, 1996; p. 389. [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer, R.; Harrison, D.L. A new look at the shrews (Soricidae) of Arabia. Bonn Zool. Bull. 1988, 39, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, P.J.J.; Harrison, D.L. Significant new records of shrews (Soricidae) from the southern Arabian Peninsula, with remarks on the species occurring in the region. Mammalia 1984, 48, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwing, S. Husbandry and breeding of the white-toothed shrews (Crocidurinae) in the Research Zoo of the Tel-Aviv University. Int. Zoo Yearb. 1970, 13, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, P.; Sádlová, J. New records of small mammals (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Rodentia, Hyracoidea) from Jordan. Cas. Národního Muz. Rada Prirodoved. 1999, 166, 25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Benda, P.; Nasher, A.K. First record of Crocidura dhofarensis Hutterer et Harrison, 1988 (Mammalia: Soricidae) in Yemen. Čas. Národního Muz. Řada Přírodověd. 2006, 175, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer, R.; Sidiyene, E.A.; Tranier, M. A record of Crocidura somalica from the Sahara. Mammalia 1991, 55, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutterer, R.; Tranier, M. The immigration of the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) into Africa and Madagascar. In Vertebrates in the Tropics; Peters, G., Hutterer, R., Eds.; Museum Alxander Koening: Bonn, Germany, 1990; pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman, R.E. Report on the mammals of Mesopotamia collected by Members of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, 1915–1919. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1920, 27, 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hatt, R.T. The mammals of Iraq. Misc. Publ. Mus. Zool. Univ. Mich. 1959, 106, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Haba, M.K. Documentation of some mammals in Iraqi Kurdistan region. J. Univ. Zakho 2013, 1, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Abass, A.F. The relative abundance and biological indicators of mammals’ community in east Hammar. Master’s Thesis, University of Basra, Basrah, Iraq, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D. The Mammals of Arabia. Volume 1, Insectivora Chiroptera Primate; Ernest Benn Limited: London, UK, 1964; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn, C.C.; Hoogstraal, H. Some mammals of Yemen and their ectoparasites. Fieldiana Zool. 1953, 34, 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Showler, D.A. Mammal observations in Yemen and Socotra, spring 1993. Sandgrouse 1996, 17, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Mensoor, M. The mammals of Yemen (Chordata: Mammalia). Preprints 2023, 2023010181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaghar, M.; Harrison, D.L. The terrestrial mammals of Bahrain. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1975, 72, 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Delany, M.J. The zoogeography of the mammal fauna of southern Arabia. Mamm. Rev. 1989, 19, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P.; Ruedi, M.; Catzeflis, F.M. A biochemical and morphological investigation of Suncus dayi (Dobson, 1888) and discussion of relationships of Suncus Hemprich Ehrenberg, 1833, Crocidura Wagler, 1832, and Sylvisorex Thomas, 1904 (Insectivora: Soricidae). Bonn. Zool. Beitr. 1998, 47, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Al Obaid, A.; Shuraim, F.; Al Boug, A.; Al Jebour, S.; Neyaz, F.; Aloufi, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diversity and conservation of bats in Saudi Arabia. Diversity 2023, 15, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, D.P.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Amori, G.; Baldwin, R.; Bradshaw, P.L.; Budd, K. The Conservation Status and Distribution of the Mammals of the Arabian Peninsula; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Environment and Protected Areas Authority: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2023; 152p.

- Massoud, D. Regional differences in the skin of the desert hedgehog (Paraechinus aethiopicus) with special reference to hair polymorphism. Zool. Anz. 2020, 289, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V.; Bergin, D. Trade in hedgehogs (Mammalia: Erinaceidae) in Morocco, with an overview of their trade for medicinal purposes throughout Africa and Eurasia. J. Threat. Taxa 2015, 7, 7131–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; Haba, M.K.; Barbanera, F.; Csorba, G.; Harrison, D.L. Checklist of the mammals of Iraq (Chordata: Mammalia). Bonn Zool. Bull. 2015, 64, 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; Ahmed, S.H.; Majeed, S.I.; Kryštufek, B.; Yusefi, G.H.; Ararat, K. Brandt’s Hedgehog, Paraechinus hypomelas (Brandt, 1836), new to the mammal fauna of Iraq. Mammalia 2024, 88, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergier, P. Presence de la pachyure Suncus etruscus dans le Golfe arabe. Mammalia 1988, 52, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Baker, M.A.; Buhadi, Y.A.; Alenezi, A.; Amr, Z.S. Mammals of the State of Kuwait; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Environment Public Authority: Kuwait, Kuwait, 2022.

- Judas, J. Terrestrial mammals of the United Arab Emirates. In A Natural History of the Emirates; Burt, J.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 427–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Aloufi, A.; Hajwal, F.; Al Ghamdi, R.; Al Boug, A.; Al Jbour, S.; Amr, Z.S. Birds dominate the diet of Barn Owls, Tyto alba, in eastern Saudi Arabia. Zool. Middle East. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).