Abstract

Filial cannibalism is the consumption of one’s own viable progeny. It occurs in a range of taxa but is particularly well-documented in fish species. Since parental care in fishes is typically male-biased, it is usually assumed that filial cannibalism is predominantly performed by the parental male while he is providing care to offspring. Filial cannibalism by females is less studied in fish. Video-recorded observations of ten pairs of adults housed in captivity revealed the first documentation of female filial cannibalism in the redhead goby (Elacatinus puncticulatus). Females were observed consuming both their own eggs and larvae. We discuss non-adaptive and adaptive explanations for female filial cannibalism in the redhead goby, including confinement due to captivity, nutritional or energetic need, and a possible lack of kin recognition. Understanding the evolutionary significance of filial cannibalism exhibited by females is an important biological inquiry. Since the redhead goby is a species used in the aquarium trade, understanding the conditions that influence female filial cannibalism in captivity may yield practical implications.

Filial cannibalism is the consumption of one’s own viable progeny [1,2,3,4]. Filial cannibalism was historically assumed to be an abnormal behavior that occurred only in unnatural or disturbed settings [5,6], until Rohwer (1978) proposed that filial cannibalism is an adaptive parental strategy that trades off current and future reproduction. Rohwer (1978) specifically suggested that by consuming some of their eggs, parents can maximize their reproductive success by obtaining energy that they then reallocate to better caring for remaining offspring and/or to increasing future reproductive success [1]. In addition to the energy-based hypothesis proposed by Rohwer (1978), alternative adaptive hypotheses have been proposed to explain the origin and maintenance of filial cannibalism. Filial cannibalism is now thought to be related to energetic need and parental condition (as suggested by Rohwer), mate availability, brood size, age of offspring, density-dependent egg survival, and offspring developmental rate (reviewed in [3,6,7,8,9,10]).

Filial cannibalism occurs in a range of taxa but is particularly well-documented in fish species [3]. Since parental care in fishes is typically male-biased, it is usually assumed that filial cannibalism in fishes is predominantly performed by the parental male while he is providing care to offspring [3]. Further, it has been proposed that males are more cannibalistic than females since they can gain energy from consuming females’ gametes, whereas females who engage in filial cannibalism would have less of a net gain in energy since they have already invested more energy into eggs than males [3,5,11]. Even in fish species in which both sexes engage in filial cannibalism, the father tends to be the predominant cannibal. For example, in spotted tilapia, Pelmatolapia mariae, a biparental fish, both parents have been observed cannibalizing their young, but males are seen most frequently performing this behavior [12,13]. Additionally, in the convict cichlid, Amatitlania nigrofasciata, males are thought to cannibalize their young more than females [14]. When females are cannibalistic, they often engage in cannibalism of young that are not their own (rather than filial cannibalism), such as in the dark chub, Nipponocypris temminckii, where females stay near the spawning area and consume eggs from other females [15]. In the study of dusky frillgoby, Bathygobius fuscus, females cannibalized eggs, but it was unclear if these eggs were their own or from eggs laid previously by another female [16]. Similarly, females of the stream goby (Rhinogobius sp.) are known to cannibalize both their own eggs and the eggs of other females, but males of this species exhibit greater rates of filial cannibalism than females [17,18]. When females of this species consume eggs, it is most often those of other females and is likely carried out to increase the area available for egg deposition [19]. In at least one species, females are thought to accidentally consume viable eggs while attempting to eat unfertilized eggs (e.g., the Egyptian mouthbrooder, Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor [20]). In general, female filial cannibalism in fish species is poorly studied and poorly documented. This is, perhaps, because it is difficult to know whether female fish engage in filial cannibalism since they leave the nest after spawning in many species. To fully understand the prevalence of filial cannibalism by females in fishes, it is important for researchers to document this behavior if and when it occurs.

In the present study, we provide evidence that redhead goby females (Elacatinus puncticulatus) engage in filial cannibalism of eggs and larvae while males take care of the young when in captivity. While, as noted above, some previous studies have documented filial cannibalism by females in other fish species, most of these studies have focused on biparental species, and the current study is the first to document filial cannibalism by females in the redhead goby.

The redhead goby is a small rocky reef goby (from 4.4 cm to 5 cm TL) with a translucent yellowish body with approximately eight black spots [21,22]. One of its most distinguishable features is the red line behind the eye and in the middle of the interorbital area [22]. Males are slightly bigger than females and have a more robust appearance, especially in the head region [23], and parental care is performed by the male [24]. The redhead goby is distributed from the Gulf of California to southern Mexico [25].

While performing experiments for a separate study on male parental care in the redhead goby, we observed and documented filial cannibalism by females. We kept 10 reproductive pairs (a single male and a single female) for behavioral observations at Unidad Piloto de Maricultivos in Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Mexico. Each pair was housed in an aquarium (25 cm × 21 cm × 25 cm) provided with either a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe or two PVC pipes as nesting sites and an artificial light simulating an ambient 16.5 h:7.5 h day/night cycle (Hygger lamp HG-990, Shenzhen Mago Trading Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). All fish in this study were fed Artemia ad libitum twice per day. In five pairs who were provided with one nest, parental behavior was filmed from the day of spawning until hatching, starting every day at 8 am and ending at 6 pm, with 10 min of video recordings taken every two hours. The remaining five pairs were filmed from the day of spawning until day five, when eggs were developed, at 10 am for 20 min.

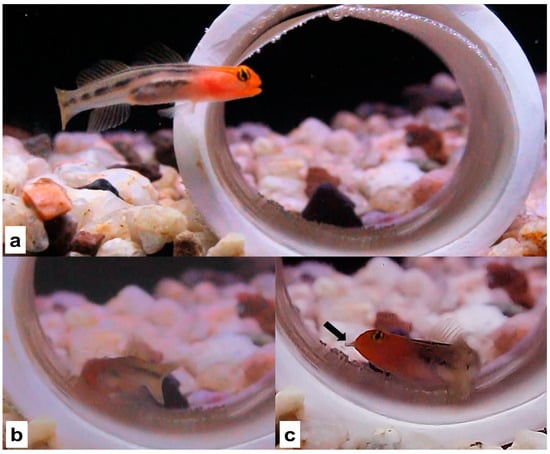

In reviewing these videos, we observed females engaging in filial cannibalism of eggs. Filial cannibalism of eggs was observed in two cases: once in which a male was provided with two nests and once in which a male was provided with one nest (Figure 1 and Video S1). When females were observed engaging in filial cannibalism of eggs, they entered the nest when males were far away and started to bite the eggs in a hasty and abrupt manner. Females were able to detach the eggs and consume them (Figure 1 and Video S1). This biting differed from the biting performed by males, which was a delicate form of biting that likely functions to clean the nest (as observed in the video found in [24]). Given that our observations of female filial cannibalism of eggs were incidental and not the primary focus of our study, it is unclear how common this behavior is. Observations of cannibalism on eggs are likely difficult to detect since males spend most of their time guarding the nest [24]. Future work aimed at detecting the frequency of female egg cannibalism in the redhead goby will require recordings of greater duration than those used in our study.

Figure 1.

Female cannibalizing eggs. (a) The female approaches the nest while the male is away from it. (b) The female biting the eggs in a hasty and abrupt manner. (c) The female with eggs in her mouth (black arrow).

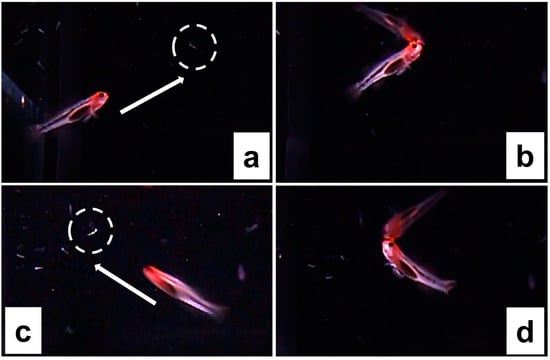

Females also engaged in filial cannibalism of their larvae. When females engaged in filial cannibalism of larvae, they chased (i.e., rapidly swam towards) and consumed the newly hatched offspring (Figure 2 and Video S1). In our study, filial cannibalism of larvae by females was observed only immediately after males engaged in larva release (see [24] for a description of male larva release behavior). However, it is possible that females engage in larval filial cannibalism at other times. In the current study, the opportunity to observe filial cannibalism of larvae by females was restricted because our filming was focused on the male only (i.e., the female was not the focal subject of our video recording), and larvae are typically very difficult (if not impossible) to spot in the tank after they leave the nest and/or are released by the male. Release of larvae by males was not observed for all ten males; however, females were observed cannibalizing larvae in 100% of the cases in which we observed male release of larvae, which was a total of three times (see [24] for larvae release). Female filial cannibalism of larvae was observed in both females that spawned for the first time in the laboratory, as well as in those females who had spawned several times in the laboratory; it is also likely that females had previously spawned in the wild before capture. Thus, female filial cannibalism in captivity does not appear to be restricted to a female’s first spawning event. In the future, it would be worthwhile to further quantify the prevalence of female filial cannibalism of larvae, and it would be informative to determine whether female reproductive experience influences patterns of filial cannibalism.

Figure 2.

Female cannibalizing larvae as they reach the top of the water column. (a,c) The female approaching the larvae. (b,d) The female consuming the larvae. In (a,c) circles indicate larvae, arrows indicate the swimming direction of the female.

These observations raise an important question: Why do females cannibalize their own progeny in the redhead goby? Female cannibalism could be related to non-adaptive or adaptive explanations.

Non-adaptive explanations of filial cannibalism by females could be possibly related to (a) confinement [12] and/or (b) nutritional or energetic need [26], although as noted above, all fish in this study were fed Artemia ad libitum. Confinement could create a scenario for females in which they face a source of nutrients (eggs and larvae), but they are not able to recognize their own progeny. In the wild, females might not need a mechanism of kin recognition since it is possible that females leave the nest soon after spawning, such that if females consume eggs, they are likely not consuming their own. Thus, it is possible that filial cannibalism by females in the redhead goby is simply the result of a lack of kin recognition mechanisms, which might be a maladaptive behavior that is typically only observed in captivity. In the future, it would be worthwhile to explore whether females remain in proximity to their young versus not in the wild.

The conditions of captivity might also influence filial cannibalism, which is something that has been documented in other species in a non-filial context. For example, in female chicks, light stimulation in captivity influences hormonal concentrations, which changes food preferences and, in consequence, the cannibalistic behavior of juveniles and eggs [27]. In the North African catfish, Clarias gariepinus, continuous light leads to high rates of cannibalism of siblings and unrelated larvae [28]. In our experimental set-up, a preset light/dark cycle was used with 16.5 h of light, simulating sunrise to sunset, as our aim was to mimic natural conditions. However, it is possible that other characteristics of our set-up did not mimic natural conditions and elicited a behavior that is unlikely to occur in the wild. For example, in our laboratory study, individuals were fed twice a day with Artemia. It is possible that such a feeding regime does not fulfill all nutritional requirements because Artemia has low levels of omega-3 fatty acids, mainly eicosapentanoic (EPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids, that are essential for marine fish and crustaceans [23,29]. In future studies, it would be worthwhile to explore how the nutritional composition of food influences filial cannibalism by females. Regardless, given that the redhead goby is commonly found in the aquarium trade, understanding the conditions that influence female filial cannibalism in captivity could also have applied implications.

Alternatively, it is possible that filial cannibalism by females in the redhead goby is an adaptive behavior that is related to energetic need, mating opportunities, or some other biotic or abiotic factors, and it is possible that filial cannibalism by females also occurs in the wild. For example, it is possible that females can recognize their offspring (something that we cannot rule out) and consume them to gain energy or nutrients that they use to increase future reproduction [1]. Females of some species, such as the three-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, perform filial cannibalism of eggs but preferentially cannibalize unrelated eggs [30]. Further, the energetic condition of parents is thought to adaptively drive [3] and/or mediate rates of filial cannibalism [11] in fishes in general, and filial cannibalism can also provide access to limited nutrients [15] even under natural conditions.

Filial cannibalism by females under natural conditions has been documented in some other fish species. For instance, female filial cannibalism of eggs occurs in Rhinogobius sp. [19]. Additionally, in this species, under captive conditions, females consume recently deposited eggs [18], a remarkable difference from our observations, where females cannibalized developed eggs (Figure 1 and Video S1). Some cichlid species (Amatitlania nigrofasciata, Neolamprologus caudopunctatus, and Pelmatolapia mariae) are also known to exhibit female filial cannibalism [12,13,14,31], although these species exhibit biparental care, which is different from the care patterns of the redhead goby. Regardless of such differences, it is possible that the female filial cannibalism that we observed is an adaptive mechanism for females to gain energy or nutrients. In the future, it would be worthwhile to evaluate the influence of female condition and energetic need on rates of cannibalism in the redhead goby. In general, it will be important to consider both adaptive and non-adaptive causes of this behavior.

In conclusion, filial cannibalism by females is not as well documented as in males in fishes, and our study is the first to document this behavior in the redhead goby. Our finding is similar to that of other Elacatinus species, E. colini and E. lori, where females were observed consuming larvae as they hatched in the laboratory [32]. However, those studies did not note cannibalism of eggs, and as such, it is unclear whether females cannibalize their eggs in these other species. While our observations of filial cannibalism in the redhead goby were incidental, we think that additional research on this topic is worthwhile, and more generally, it is important for researchers to continue to document filial cannibalism by females if and when it occurs in fishes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17050365/s1; Video S1: Female cannibalizing her own eggs and larvae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.-G. and H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.-G., H.K., and B.P.C.-V.; writing—review and editing, M.T.-G., H.K., and B.P.C.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, grant number SIP20240325.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal collection permit was approved by the National Commission for Aquaculture and Fisheries (PPF/DEGOPA-014/23) (15 February 2023). Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all animal welfare conditions in captivity were met, and fish were not sacrificed in the process.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mariae del Carmen Estrada González, Mauricio Contreras Olguín, and Laura Guadalupe Flores Montijo for their help with keeping fish at the laboratory. Miguel Trujillo is a fellow student of BEIFI (IPN) and SECIHTI (713420); the results presented here are part of his PhD thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rohwer, S. Parent Cannibalism of Offspring and Egg Raiding as a Courtship Strategy. Am. Nat. 1978, 112, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, R.C. Ecology of Filial Cannibalism in Fish: Theoretical Perspectives. In Cannibalism: Ecology and Evolution Among Diverse Taxa; Elgar, M.A., Crespi, B.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 38–62. [Google Scholar]

- Manica, A. Filial Cannibalism in Teleost Fish. Biol. Rev. 2002, 77, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, K. The Evolution of Filial Cannibalism and Female Mate Choice Strategies as Resolutions to Sexual Conflict in Fishes. Evolution 2000, 54, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, G.J. Filial Cannibalism in Fishes: Why Do Parents Eat Their Offspring? Trends Ecol. Evol. 1992, 7, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.P.H. Parent–Offspring Cannibalism throughout the Animal Kingdom: A Review of Adaptive Hypotheses. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1868–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, M.; Okuda, N. Mate Availability Influences Filial Cannibalism in Fish with Paternal Care. Anim. Behav. 2002, 63, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, H.; Bonsall, M.B. When to Care for, Abandon, or Eat Your Offspring: The Evolution of Parental Care and Filial Cannibalism. Am. Nat. 2007, 170, 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, H.; Lindström, K. Hurry-up and Hatch: Selective Filial Cannibalism of Slower Developing Eggs. Biol. Lett. 2008, 4, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Klug, H.; Lindström, K.; St. Mary, C.M. Parents Benefit from Eating Offspring: Density-Dependent Egg Survivorship Compensates for Filial Cannibalism. Evolution 2006, 60, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Agostinho, A.A.; Winemiller, K.O. Revisiting Cannibalism in Fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2017, 27, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanck, E. Filial Cannibalism in Tilapia mariae. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 1986, 2, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanck, E.J. Parental Care of Tilapia mariae in the Field and in Aquaria. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1989, 24, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, R.J.; Keenleyside, M.H.A. Filial Cannibalism in the Biparental Fish Cichlasoma nigrofasciatum (Pisces: Cichlidae) in Response to Early Brood Reductions. Ethology 1990, 86, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katano, O.; Maekawa, K. Individual Differences in Egg Cannibalism in Female Dark Chub (Pisces: Cyprinidae). Behaviour 1995, 132, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishida, Y. Egg Consumption by the Female in the Paternal Brooding Goby Bathygobius fuscus. Fish. Sci. 2002, 68, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Iwao, H.; Sakata, J.; Inoue, M.; Omori, K.; Yanagisawa, Y. Simultaneous Spawning by Female Stream Goby Rhinogobius sp. and the Association with Brood Cannibalism by Nesting Males. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 89, 1592–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, N.; Ito, S.; Iwao, H. Female Spawning Strategy in Rhinogobius sp. OR: How Do Females Deposit Their Eggs in the Nest? Ichthyol. Res. 2002, 49, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Yanagisawa, Y. Mate Choice and Cannibalism in a Natural Population of a Stream Goby, Rhinogobius sp. Ichthyol. Res. 2000, 47, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowka, W. Filial Cannibalism and Reproductive Success in the Maternal Mouthbrooding Cichlid Fish Pseudocrenilabrus milticolor. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1987, 21, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.R.; Robertson, D.R. Fishes of the Tropical Eastern Pacific; University of Hawaii Press: Hong Kong, China, 1994; ISBN 0-8248-1675-7. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D.; FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Available online: http://fishbase.org (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Wittenrich, M.L. The Complete Illustrated Breeder’s Guide to Marine Aquarium Fishes; T.F.H. Publications: Neptune City, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo-García, M.; Klug, H.; Balart, E.F.; Ceballos-Vázquez, B.P. Paternal Care in the Redhead Goby, Elacatinus puncticulatus. J. Ethol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Huerta, E.R.; Beltrán-López, R.G.; Pedraza-Marrón, C.R.; Paz-Velásquez, M.A.; Angulo, A.; Robertson, D.R.; Espinoza, E.; Domínguez-Domínguez, O. The Evolutionary History of the Goby Elacatinus puncticulatus in the Tropical Eastern Pacific: Effects of Habitat Discontinuities and Local Environmental Variability. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 130, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Reay, P. Cannibalism in Teleost Fish. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 1991, 1, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, R.C. Cannibalism. In Welfare of the Laying Hen; CABI Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2004; Volume 27, pp. 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Adamek, J.; Kamler, E.; Epler, P. Uniform Maternal Age/Size and Light Restrictions Mitigate Cannibalism in Clarias gariepinus Larvae and Juveniles Reared under Production-like Controlled Conditions. Aquac. Eng. 2011, 45, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.A.; Sorgeloos, P.; Trotman, C.N.A. (Eds.) Artemia Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991; ISBN 9781315890791. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, G.J.; van Havre, N. The Adaptive Significance of Cannibalism in Sticklebacks (Gasterosteidae: Pisces). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1987, 20, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Saraiva, F.; Balshine, S.; Wagner, R.H.; Schaedelin, F.C. From Cannibal to Caregiver: Tracking the Transition in a Cichlid Fish. Anim. Behav. 2018, 139, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoris, J.E.; Francisco, F.A.; Atema, J.; Buston, P.M. Reproduction, Early Development, and Larval Rearing Strategies for Two Sponge-Dwelling Neon Gobies, Elacatinus lori and E. colini. Aquaculture 2018, 483, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).