Abstract

Microbial mutualisms are still commonly described as obligate or facultative, but this dichotomy is insufficient to describe the complexity of host–microbe interactions. A multi-dimensional conceptual framework that accounts for asymmetry in dependency and taxonomic membership flexibility is introduced. This framework allows the classification of mutualisms by how they are structured and for whom the interaction is necessary. The dimensions include dependency considered independently for both organisms, and both the global/potential and individual/actual microbiome diversities. Examples are given primarily from the field of insect–microbe interactions, showing how past frameworks cannot fully encompass the diversity of symbioses. This new framework integrates symbiont community complexity and highlights functional redundancy, which is useful for understanding host plasticity, vulnerability, invasiveness, and resilience.

1. Introduction

Microbe–host mutualisms are traditionally labelled as obligate, where neither symbiont can survive without the other, and facultative, where both organisms benefit from the mutualism but neither requires it to live [1,2]. This binary oversimplifies the diversity of these mutualistic relationships, as shown by recent works challenging past assumptions about gut microbes. The obligate–facultative dichotomy cannot capture the physiological, developmental, and evolutionary role of microbiomes to their hosts. Host–microbe interactions require at least a two-dimensional model to be meaningfully classified, allowing more nuanced analysis with implications for host adaptation, pest biology, conservation, etc.

2. The Traditional Binary and Its Limitations

In classical ecological theory, obligate mutualists have co-evolved to the point that the mutualism is necessary for survival. For example: All aphids house endocellular Buchnera aphidicola endosymbionts in specialized bacteriocytes, depending on the symbiont for essential amino acids. Buchnera in turn lost enough genes such that they cannot live outside their host. The mutualism is obligate in both organisms, and vertical transmission ensures that every aphid is born with Buchnera [3]. Another example is Macrotermitidae and the symbiotic, cellulolytic Termitomyces fungi that they farm [4]. The termites cannot live without the fungus and, although the fungus does grow externally on the termite body, it cannot compete with other microbes in the environment without the selective tending of the termite farmers, such that these fungi are never found in the wild outside of active termite nests.

A facultative mutualism, by contrast, is one where the organisms both survive without the other, but mutualism significantly improves aspects of fitness like survival, growth rate, reproductive rate, etc. The classic example given in contrast to aphids and Buchnera are stink bugs like Riptortus pedestris and Burkholderia bacteria [5]. Unlike Buchnera, Burkholderia are free-living and acquired by the stink bugs from the environment of each generation. The bacteria provide nutrients absent from the insect’s diet and can degrade certain insecticides. Stink bugs in insecticide-contaminated environments thus benefit from having Burkholderia in their midguts, but the symbiont is not essential for their survival. Likewise, the stink bug midgut crypts are a stable environment for Burkholderia and a source of transportation to new environments, but the microbe does not need the insects to survive [5]. This mutualism is facultative: beneficial if present, but not essential for survival.

Newer research exposed the limitations of this dichotomy. One issue is asymmetry in dependency: one organism may require the mutualism to survive and the other does not, even if it benefits them. Within aphids, other endosymbionts besides Buchnera like Hamiltonella defensa, Regiella insecticola, or Serratia symbiotica may be present [6,7]. The insect benefits from their roles in nutrient provisioning or defense against parasitoids, but does not require them: for the insect, the mutualism is facultative. However, Hamiltonella defensa and Regiella insecticola exist mostly as vertically-transmitted, endocellular endosymbionts, for which the mutualism may be obligate [8]. In the opposite direction, Oryctes rhinoceros beetle larvae fully depend on cellulolytic gut microbes for digestion of their woody diet: an obligate symbiosis for the beetle. However, the microbes are all acquired and enriched from the diet, as in the Burkholderia system, with no system of horizontal or vertical transmission; so, for the microbes, the mutualism is facultative [9]. Note that the symbioses described above are not commensalisms, where the symbiosis benefits one organism and is neutral to the other. These are true mutualisms where both organisms benefit, but the essentiality is unequal.

Another factor to consider is the taxonomic diversity of the mutualists, both in general and within a single instance. Pollinator biology already recognizes this issue as asymmetric specialization: one-to-one pollinator-plant species relationships exist, as do specialist plants that depend on a generalist pollinator and generalist plants among whose pollinators are specialist insects [10]. In host–microbe mutualisms, Buchnera aphidoicola is essential to thousands of species of Aphididae. In fungus-growing termites, multiple species of fungus can be grown by the same species of termite, and multiple species of termite can grow the same species of fungus. However, each termite nest will typically farm a single fungal species as a monoculture [4], while in Oryctes, different phyla of bacteria can serve as cellulolytic symbionts and multiple such species may colonize the same individual’s gut [9]. To properly classify microbial mutualisms thus requires consideration for community-level interactions and greater clarity for systems with flexible membership, like gut microbiomes.

3. A New Typology for Microbial Mutualisms

To account for the above factors and better classify host–microbe mutualisms beyond the obligate–facultative dichotomy, the following multidimensional framework is presented, with some new terminology to accompany the model.

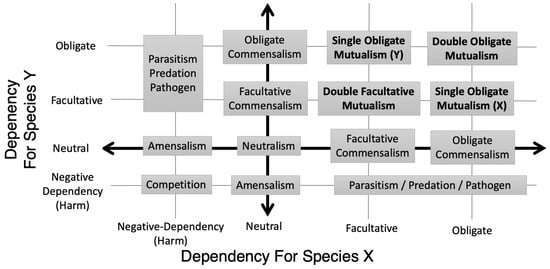

The first dimensions are dependency, considered separately for both members of the symbiosis, as graphed in Figure 1. If one includes complete non-dependency (neutrality) and negative-dependency (harm), the graph will include neutralism, facultative and obligate commensalisms, amensalism, parasitism/predation, and competition [11]. Within mutualisms, the novel framework produces four quadrants. By the origin are “double facultative mutualisms” (DFMs), such as the stink bug/Burkholderia symbiosis. These should not be confused with a “double mutualism,” where two species benefit each other in two different functions [12]. Opposite this are “double obligate mutualisms” (DOMs), such as the aphid/Bucherna and termite/fungus symbioses. The other quadrants are “single obligate mutualisms” (SOMs), though they could just as easily be called “single facultative mutualisms” (SFMs). These are either host–obligate/microbe–facultative mutualisms like Oryctes and its gut microbes, or host–facultative/microbe–obligate mutualisms like Hamiltonella and its insect hosts. Specifically within host–microbe mutualisms, the terms “host-obligate mutualism” (HOM or SOM-host) and “microbe-obligate mutualism” (MOM or SOM-microbe) can be used, or their respective synonyms, “microbe-facultative mutualism” (MFM) and “host-facultative mutualism” (HFM).

Figure 1.

Symbioses arranged along dimensions of dependency for each organism. Each axis shows dependency for one of two organisms in a mutualism (ex: host and microbe) from negative dependency (indicating that the symbiosis harms the organism) to true neutrality to positive dependencies (indicating the symbiosis benefits the organism), and from facultative to obligate. In addition to classical symbiosis categories like commensalism and parasitism, this view produces a four-quadrant division of mutualisms: double facultative, double obligate, and two single obligate mutualisms/single facultative mutualisms (ex: host–obligate but microbe–facultative, and microbe–obligate but host–facultative).

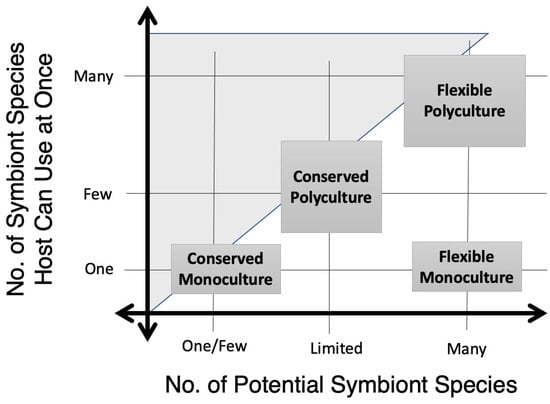

Additional dimensions, best seen from the reference frame of the host (an individual organism’s body or superorganism’s nest, etc.), are the number of microbe species worldwide with the potential to participate as the mutualists, and the number that can be used in any individual instance at any one time (Figure 2). By the origin are mutualisms where only one microbe species is ever involved: “conserved monocultures”, where only one or very few microbial species can serve as symbionts, and each host individual rarely carries or maintains more than one of them. These relationships are typically highly specialized and evolutionarily conserved, like Buchnera and aphids, Burkholderia and stink bugs, and Termitomyces and termites. Conserved monocultures can be vertically, horizontally, or environmentally transmitted, and can be obligate or facultative. The dimensions of potential and actual microbial symbiont pools are distinct from the dimensions of dependency.

Figure 2.

Mutualisms arranged along dimensions of potential and actual microbiome diversity. The x-axis reflects the number of possible microbe clades that could potentially function within a host-microbe mutualism, while the y-axis reflects the number that are functioning in an individual symbiotic instance (ex: inside an individual host’s body or habitat at a single moment in time). When a microbiome always contains the same member(s), it is conserved, but if it varies taxonomically while retaining its function, it is flexible. When it rarely contains more than one dominant member, it is a monoculture, while microbiomes that can contain multiple species engaged in the symbiotic function simultaneously are polycultures.

Further along the potential pool size axis are “flexible monocultures,” where only one microbe strain can play the symbiotic role in any individual at any time, but the global or environmental pool of potential mutualists is high. This system conserves function, rather than taxonomic identity. For example: the Aedes mosquito larval gut is typically dominated by one environmentally acquired microbe species, without which the larva dies, but the identity of this symbiont varies greatly even within larvae from the same container [13,14]. The leading explanation is that the symbiont blocks pathogens through microbial antagonism, so its taxonomic identity does not matter so long as it literally fills the gut niche.

Multiple microbes functioning as mutualists in the same host simultaneously (though not necessarily in equal abundance) are a polyculture. If a limited number of microbe clades appear as these symbionts more frequently than they appear in the host’s environment, then the system is a “conserved polyculture,” and these clades are often described as “core” microbes. For example, in global studies of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae, while the gut microbiome varies greatly; a few genera consistently appear as the most abundant, like Dysgonomonas, Klebsiella, Morganella, and Providencia [15]. The forces selecting for these “cores” is currently unknown. Farthest from the origin are “flexible polycultures,” as in Oryctes, where the possible species pool for the polyculture is extremely diverse and unrelated, rather than a select core. It could even involve bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, for example. Note that there is no current consensus on how frequently “core” microbes have to appear in a host species, either globally or in a narrow population, to be called as such.

4. Implications for Ecology, Evolution, and Research

Dependency and specificity have implications. The more flexible and less specific the taxonomic composition of the mutualism, the more easily the host can acquire the necessary symbionts from different environments, facilitating host adaptation to new diets, habitats, or in response to perturbation [16]. Flexibility thus facilitates invasiveness, as posited for Oryctes rhinoceros [9], and improves host resilience to change, perhaps just as much as gut microbe resilience in conserved systems [17]. Microbiome loss, as can happen unintentionally under climate change [18] or intentionally as pest control [19], would threaten host survival in a host–obligate mutualism only if the symbiont pool was taxonomically conserved and not flexible. Dependency alone would not predict susceptibility to such control strategies.

For any system, questions will arise over how a particular mutualism evolved. For example, are DFMs the base for all mutualisms, potentially evolving into SOMs and DOMs later on, or do other factors lead mutualisms down a certain path? Selection can occur at the level of the taxon, as in the genome reduction of Buchnera following extended co-evolution with aphids, or at the level of function, as in the gut of rhinoceros beetle larvae whose microbiota always have a similar functional profile even when the species composition differs radically. Different mutualisms certainly have different evolutionary histories, and the factors that can drive pathogenic or transient microbes to become mutualists have yet to be untangled [20,21,22,23]. The many ways a third species could form a symbiosis with one or both members of a mutualism add further opportunities for theoretical and experimental study [24].

Thus, researchers should rethink how they study microbial mutualisms to ensure they are capturing functional profiles as well as taxonomic composition. Microbiome studies, especially for extracellular symbionts acquired from the environment, rather than transovarially, should always include samples of this environment, as this microbial pool will shape the community composition of the host microbiome. Standard taxonomic profiling of a microbiome should be combined with functional profiling, in part to see which is more globally conserved. Longitudinal studies of transmission and colonization dynamics (from parent to offspring, among individuals, or between life stages in the same individual) are valuable to see if the taxonomic composition and/or functional capacity of the microbiome shifts. One should not assume that taxonomic stability equals obligacy, or that taxonomic flexibility equals facultativity. A microbiome may be the same in every examined host but could still be facultative if the host can survive without it or replace it under certain conditions. Sampling from distant geographic populations with potentially different symbiont pools could identify such cases. Conversely, a microbiome could be highly variable in composition across hosts but obligate in function if the host always needs some partner providing a specific ecological service; checking for a conserved functional profile would avoid this misclassification pitfall. Finally, one should consider the possibility that an apparent mutualism may be a commensalism, neutralism, or even amensalism. In microbiome research, always including environmental microbial pools in microbiome sampling will not only identify environmental acquisition of symbionts, but also any cases where an uncommon environmental microbe becomes abundant and dominant in the host, which could be evidence of a mutualism rather than a transient presence.

5. Conclusions

Presented here is a new typology for microbial mutualisms that accounts for dependency asymmetry plus taxonomic versus functional conservation. Terms such as single and double obligate mutualisms, and flexible and conserved mono- and polycultures are introduced to facilitate discussion of this expanded model. Future empirical work should include both taxonomic and functional profiling of microbiomes, always sample the environmental sources of symbionts, and cover longitudinal studies over time and across individuals or geographic distances whenever possible. Field-wide adoption of multidimensional thinking for microbial mutualisms (if not mutualisms in general) can ensure that researchers get a full and accurate picture of how these systems are maintained and evolve.

Funding

This research was funded by Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council, Grant Number 114-2311-B-002-017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFM | Double Facultative Mutualism |

| DOM | Double Obligate Mutualism |

| HFM | Host–Facultative Mutualism |

| HOM | Host–Obligate Mutualism |

| MFM | Microbe–Facultative Mutualism |

| MOM | Microbe–Obligate Mutualism |

| SFM | Single Facultative Mutualism |

| SOM | Single Obligate Mutualism |

References

- Gupta, A.; Nair, S. Dynamics of Insect–Microbiome Interaction Influence Host and Microbial Symbiont. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuk, R.A. Gut Bacteria in the Holometabola: A Review of Obligate and Facultative Symbionts. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Nikoh, N.; Shimada, M.; Fukatsu, T. Strict host-symbiont cospeciation and reductive genome evolution in insect gut bacteria. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, S.; Inoue, T.; Ohkuma, M.; Yaovapa, T.; Johjima, T.; Suwanarit, P.; Sangwanit, U.; Vongkaluang, C.; Noparatnaraporn, N.; Kudo, T. Fungal Community Analysis of Fungus Gardens in Termite Nests. Microbes Environ. 2005, 20, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, K.; Kikuchi, Y. Riptortus pedestris and Burkholderia symbiont: An ideal model system for insect–microbe symbiotic associations. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E.; François, C.L.M.J.; Minto, L.B. Facultative ‘secondary’ bacterial symbionts and the nutrition of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Physiol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.M.; Degnan, P.H.; Burke, G.R.; Moran, N.A. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Monnin, D.; Lee, R.A.R.; Henry, L.M. Local adaptation to hosts and parasitoids shape Hamiltonella defensa genotypes across aphid species. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20221269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-J.; Huang, J.-P.; Chiang, M.-R.; Jean, O.S.M.; Nand, N.; Etebari, K.; Shelomi, M. The hindgut microbiota of coconut rhinoceros beetles (Oryctes rhinoceros) in relation to their geographical populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e00987-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, D.P.; Aizen, M.A. Asymmetric Specialization: A Pervasive Feature of Plant-Pollinator Interactions. Ecology 2004, 85, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheam, D.; Nishiguchi, M.K. Symbiosis: A Review of Different Forms of Interactions Among Organisms. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 3rd ed.; Scheiner, S.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, F.; Kaiser-Bunbury, C.; Olesen, J.M.; Traveset, A. Global patterns of the double mutualism phenomenon. Ecography 2019, 42, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, F.; Casiraghi, M.; Bonizzoni, M. Aedes spp. and Their Microbiota: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnusamy, L.; Xu, N.; Stav, G.; Wesson, D.M.; Schal, C.; Apperson, C.S. Diversity of Bacterial Communities in Container Habitats of Mosquitoes. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 56, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-W.; Shelomi, M. Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Microbiome and Microbe Interactions: A Scoping Review. Animals 2024, 14, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hulcr, J.; Sun, J. The Role of Symbiotic Microbes in Insect Invasions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Anderson, J.M.; Bharti, R.; Raes, J.; Rosenstiel, P. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Tada, A.; Musolin Dmitry, L.; Hari, N.; Hosokawa, T.; Fujisaki, K.; Fukatsu, T. Collapse of Insect Gut Symbiosis under Simulated Climate Change. mBio 2016, 7, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupawate, P.S.; Roylawar, P.; Khandagale, K.; Gawande, S.; Ade, A.B.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Borgave, S. Role of gut symbionts of insect pests: A novel target for insect-pest control. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1146390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Althoff, D.M. Extreme specificity in obligate mutualism—A role for competition? Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.A.; McCutcheon, J.P.; Nakabachi, A. Genomics and Evolution of Heritable Bacterial Symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, T.; Ishii, Y.; Nikoh, N.; Fujie, M.; Satoh, N.; Fukatsu, T. Obligate bacterial mutualists evolving from environmental bacteria in natural insect populations. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, J.L. The evolution of facilitation and mutualism. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, G.; Suzuki, K. Global stability of obligate mutualism in community modules with facultative mutualists. Oikos 2016, 125, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).