Abstract

Accurate species identification in blackberries (Rubus spp.) is difficult because of morphological similarity and frequent hybridization. We studied 56 wild accessions from the Sirius Federal Territory (Russia), representing coastal and foothill ecosystems of the Black Sea region. Multilocus DNA barcoding with the plastid rbcL gene and nuclear ITS1 and ITS2 regions revealed signals of hybridization and hidden diversity. The rbcL marker showed low variation, grouping most accessions into two clusters with several singletons, which limited its use for distinguishing species. In contrast, ITS1 and ITS2 showed higher variation, forming six clusters and eight singletons, and allowed for clear separation of taxa such as Rubus caesius L., R. irritans Focke, and R. amabilis Focke. Accession 3 carried a raspberry (closely to R. corchorifolius L.fil) plastid haplotype, pointing to a hybrid origin. We also found groups of nearby plants with identical mutations, which likely reflect clonal spread with fixed somatic changes or the persistence of recent hybrid lineages. At the same time, accessions collected up to 140 km apart did not form separate clusters, showing weak geographic structuring along the coast. The results demonstrate that multilocus barcoding can reveal not only species boundaries but also evolutionary processes among Rubus such as hybridization, clonal propagation, and early stages of speciation.

Keywords:

Rubus; blackberry; diversity; DNA barcoding; identification of species; ITS; rbcL; AmpliSeq; hybridization 1. Introduction

Studying the biodiversity of wild plants helps assess the impact of human activity and historical factors on the distribution of new biological forms [1]. Traditional morphological methods for determining species are often insufficient due to the high variability of traits (e.g., petiole length-to-width ratio, internode length, inflorescence structure) [2], also in taxa with complex hybridization. Genetic-based methods enable a more precise analysis by bypassing the influence of environmentally induced phenotypic plasticity. Furthermore, accurate identification of plant species in regions that lack prior biodiversity studies is essential for making decisions about land development and protecting natural ecosystems [3]. This issue is important when planning infrastructure projects, where rare and endemic species may occur among unaccounted [4].

In the study, we assessed plant diversity in a heavily altered coastal area, transformed from natural wetlands into a large-scale urban and recreational complex. We focus on taxonomically challenging plant groups prone to hybridization, using the genus Rubus (blackberries and raspberries) as a model. Rubus is ideal for this purpose due to its widespread occurrence, phenotypic plasticity, frequent interspecific hybridization, and capacity for clonal reproduction, which complicate traditional morphological identification. By applying the method of DNA barcoding to Rubus populations, we aim to conduct an accurate genetic census and detect signals of hybridization or cryptic diversity.

The genus Rubus (family Rosaceae) includes more than 700 species (12 subgenera), among which the central place is occupied by red raspberries (Rubus idaeus L.), black raspberries (R. occidentalis L.), blackberries (R. fruticosus Weihe), and their hybrids, such as boysenberry, marionberry, loganberry, and nessberry [5,6,7]. Species of Rubus are found throughout Asia, Europe, and the Americas, but their origin is thought to lie either in North America or southwestern China [8,9,10]. The breeding of blackberries and raspberries began about 100 years ago, making them relatively recent domesticated crops [8]. Modern blackberry breeding is aimed at creating thornless varieties, since thorns not only damage the fruit, but also increase susceptibility to disease and reduce commercial yield [11,12,13]. The fruits are considered a «superfruit» due to their high content of health-promoting compounds: dietary fiber, vitamins C and K, manganese, polyphenols, flavanols, organic acids [6,14,15].

Wild blackberries grow everywhere, including abandoned areas, drainage ditches, cemeteries, and roadsides. Although some species are native to temperate regions, blackberries are also found from subtropical to Arctic zones and can grow at elevations ranging from sea level up to 4500 m [16]. Plants spread quickly through vegetative reproduction, such as tip layering or root suckers, that allow blackberries to occupy large territories. Their fruits attract animals, which helps widely disperse seeds, while the dense blackberry bushes also serve as nesting sites for birds. As a result, blackberries, with their ability to hybridize, undergo polyploidization, introgression and reproduce through apomixis, can easily colonize new areas and act as fast invaders [6,10]. Genetically, blackberry has a wide range of ploidy levels, from diploid to dodecaploid (2n = 2x = 14 to 2n = 12x = 84) [12,17,18]. The initial genome assembly within Rubus species was assembled in 2016 for black raspberry (R. occidentalis L.) using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology [19]. Later, in 2023, the genome assembly of diploid blackberry (R. argutus Link variety ‘Hillquist’) was published [20], enabling genome-wide association study (GWAS) that identified of multiple quantitative loci (QTLs) and candidate genes associated with fruit firmness [21]. And recently, in 2025, genome assembly of cultivated tetraploid blackberry (Rubus L. subgenus Rubus Watson) was published, where 87,968 protein-coding genes were predicted (82% were functionally annotated) [22]. A 2024 study assembled and annotated 64 Rubus plastomes, including seven new sequences (155,530–156,700 bp), that advancing ongoing work to characterize plastid genomes [23,24,25]. Blackberry, with its complex evolutionary history involving hybridization, polyploidy, and apomixis, represents one of the most taxonomically challenging groups within the genus Rubus [10,26].

Hybridization plays a fundamental role in plant evolution and speciation and has long been recognized as an important source of genetic variation rather than an evolutionary dead end. Many ideas about the role of hybridization in generating biological diversity were formulated decades to over a century ago, and modern genomic tools are now greatly improving our ability to detect hybridization and understand its effects in plants [27,28]. Current genomic studies reveal that introgression and distant hybridization serve as important mechanisms of adaptive evolution, contributing to the emergence of new species through polyploidization and homoploid speciation [28,29]. Distant hybridization between phylogenetically divergent species can overcome interspecific barriers and significantly increase genetic diversity [30,31,32]. Introgressive hybridization allows for the transfer of adaptive alleles between species, enabling faster adaptation to new environmental conditions compared to mutations and standing genetic variation [33,34].

Speciation through hybridization occurs primarily through two pathways: allopolyploid and homoploid mechanisms [35]. Allopolyploid speciation (i.e., duplication of hybrid genomes), arising from hybridization followed by genome duplication, represents the most common mechanism, with approximately 11% of species in 47 studied plant genera having allopolyploid origins [28,36]. Homoploid hybrid speciation (without a change in chromosome number), though rarer, is also documented, particularly between less diverged species [37,38,39]. Reproductive barriers in plants operate at multiple levels: prezygotic barriers include geographic isolation, habitat divergence, and pollinator specialization, while postzygotic barriers manifest as hybrid weakness, sterility, or lethality [40,41]. The genus Rubus, which is characterized by extensive hybridization and polyploidy [42], can be a model for studying evolutionary processes [10] and assessing their ecological consequences [43]. The observed genetic diversity of plants sampled from a specific territory provides insights into their origin and dispersal history, while also enhancing our understanding about the impacts of historical events (e.g., agricultural expansion, urbanization, species introductions).

A solution to the problem of species identification is the using of DNA barcoding, a method based on the analysis of short standardized genetic markers (barcodes) [44,45]. In 2009, the Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL) proposed using for land plants 2-locus combination of plastid DNA genes of maturase K (matK) and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (rbcL), which provide sufficient level of species discrimination [46]. However, amplification and sequencing of the matK barcoding region remains challenging due to high sequence variability in the primer binding sites [47,48]. A study analyzing processed berry products (fruit juices and jams) demonstrated that rbcL and matK exhibited strong amplification efficiency and species discrimination; however, matK has high sequence variability hindered primer design for barcoding [49]. As an alternative, nuclear ribosomal non-coding transcribed spacers ITS1 and ITS2 spacers have been validated as effective barcoding regions, they amplify reliably across species and clearly distinguish close relatives [17,50,51,52,53]. The combination of nuclear ribosomal ITS regions and chloroplast markers enhances species resolution assessing maternal lineage and nuclear genome variation [54]. An optimal strategy involves developing markers that integrate variable regions from nuclear and plastid DNA, especially given recent progress in blackberry genome and plastome assemblies [22,24,25]. For analysis, sequenced markers’ public repositories like NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information), BOLD (Barcode of Life Data System), GRD (Genome Database for Rosaceae) are available. Currently, BOLD system hosts 454,979 plant sequences for core barcodes: matK, rbcL, ITS1, ITS2 (BOLD, https://id.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025) [55,56]. In the Rosaceae family, barcoding was performed using rbcL, matK, rpoC1 and ITS2 markers, marking ITS2 as successful for species identification [53,57]. In this study, we used DNA barcoding (ITS1 + ITS2 + rbcL) coupled with Illumina NGS to analyze widespread Rubus plants in the Sirius Federal Territory (Russia)—the region hosting the 2014 Winter Olympic Games.

The Sirius Federal Territory was established in 2020 following the separation of the Imereti Lowland from Sochi’s Adler district, occupied 14.19 km2. This lowland, situated between the Mzymta and Psou rivers, is a remnant of the Black Sea coastal terrace and represents a rare landscape type in the Russian Black Sea region, characterized by broad open spaces between the sea and the foothills. The area hosts key infrastructure from the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, including sports venues, hotels, and a seaport at the Mzymta river mouth. Dense development along the shoreline has intensified challenges in coastal protection, landscape preservation, and maintaining the recreational value of beaches. «Sirius» has a humid subtropical climate shaped by the warming influence of the Black Sea and the shielding effect of the Main Caucasian Ridge. The region experiences hot, humid summers, mild winters, and extended spring and autumn seasons, resembling a Mediterranean climate. However, winters remain unstable due to periodic cold air intrusions. Climatic and soil conditions support both native vegetation and the successful introduction of exotic plant species from tropical regions of Eurasia, Australia, Oceania, and the Americas (Magnolia grandiflora L., Phoenix canariensis Chabaud, Nerium oleander L., Eucalyptus cinerea F.Muell. ex Benth) [58]. The natural vegetation of the Imereti lowland had significant changes and is still under anthropogenic influence due to infrastructure development [59]. After hosting the Olympics, the «Sirius» transformed into a science and technology hub, creating an education center that includes schools and universities. Nevertheless, remnants of natural plant communities persist in undisturbed areas such as ornithological parks (bird nesting sites), wetlands, old indigenous cemeteries, and undeveloped beaches [59]. Plants of Rubus are widespread, particularly in areas that have remained free from human activity.

The transformation of the Imereti Lowland reflects a sequential replacement of ecosystems: natural ecosystems were first modified into agroecosystems and later converted into urban ecosystems under intensive development [59]. Urban ecosystems represent the most invasion-prone landscape type, functioning as primary introduction hubs where ornamental plant escapes from artificial plantings constitute the dominant naturalization pathway [60,61]. Studies demonstrate that over 75% of urban garden flora consists of alien species, with approximately two-thirds already naturalized elsewhere in the world [62]. This progression has led to a sharp reduction in native plant communities and the spread of naturalized species [63]. Evaluation of such ecosystem transitions is essential for assessing biodiversity loss, managing invasive plants [60], and developing strategies for sustainable landscaping.

The present work aims to evaluate the effectiveness of DNA barcoding for species identification within the genus Rubus, using a combination of plastid (rbcL) and nuclear (ITS1, ITS2) markers. It represents the initial phase of the comprehensive study and monitoring of plant biodiversity on the Black Sea coast, with the primary goal being to create a plant diversity database, which will serve as a tool for regional planning and development.

2. Materials and Methods

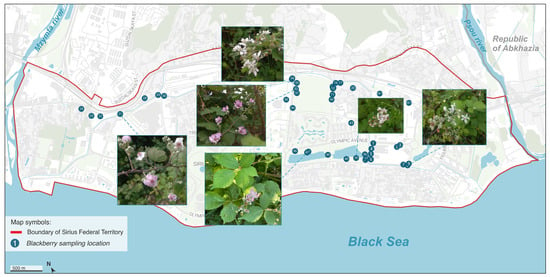

For the analysis of blackberry species diversity, we collected 56 samples, including 49 from the Sirius Federal Territory and 7 from the Republic of Abkhazia (116, 117, 118, 118-1, 118-2, 119-2, 119-4), with the most distant sample obtained near the Sukhum city, 140 km from «Sirius» (Figure 1, Table S1). All sampling sites are located in a humid subtropical climate zone, though local conditions differ depending on elevation and proximity to the Black Sea. In the Sirius Federal Territory (sea level to ~2 m a.s.l.), the mean annual temperature is 18.9 °C, with daily maxima of 29 °C in July and minima of 4 °C in January [64]; average annual precipitation reaches 1651 mm, and relative humidity is about 75%. The area represents a gently sloping coastal terrace rising from the Mzymta river mouth to 50–100 m inland, with no major topographic barriers to wind circulation. In the Republic of Abkhazia, including the most distant site near Sukhum (sea level to ~1 m a.s.l.), the mean annual temperature is 14.8 °C, with daily maxima of 28 °C in July and minima of 1 °C in January [65]. Average precipitation is 1199 mm, while relative humidity remains around 75%, peaking in winter (up to 87% in December) and reaching the lowest values in summer (about 62% in August). Long-term wind rose data indicate prevailing southwest and northwest winds, shaped by the influence of Black Sea breezes and orographic effects of the Caucasus foothills.

Figure 1.

Collection sites of Rubus samples in the Sirius Federal Territory, with representative flower photographs from selected specimens. Note: Samples from Abkhazia are not displayed on this map, because they did not turn out to be unique.

During collection, we performed morphological characterization while preserving leaf specimens for herbarium storage and collecting fresh leaves for DNA extraction. Herbarium specimens are deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology at the Sirius University of Science and Technology. Total DNA was extracted from fresh and frozen leaves using the GMO-Sorb B kit (Syntol, Moscow, Russia) and following the manufacturer’s CTAB-based protocol.

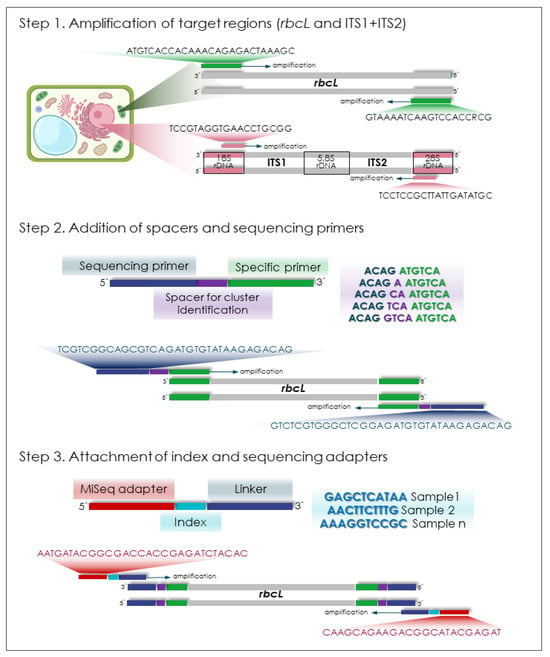

Library preparation for Illumina MiSeq sequencing (AmpliSeq technology) involved three PCR steps: (1) initial amplification of target regions using universal primers for rbcL and ITS1 + ITS2; 2); (2) addition of spacers and sequencing primers; (3) attachment of indexes and sequencing adapters (Figure 2) [66]. The ITS1 and ITS2 regions were amplified in a single PCR reaction using ITS1/ITS4 primers (product is ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2) (Table 1). All PCR reactions used Tersus Plus polymerase (Eurogen, Moscow, Russia) in 25 µL reactions containing: 0.5 µL polymerase; 5 µL 5X Tersus Red buffer; 0.5 µL 50X dNTPs (10 mM each); 2 µL each of primer (10 pM/µL); 1 µL DNA template (50 ng/µL); and 14 µL water.

Figure 2.

Library preparation workflow for the rbcL marker prior to Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for DNA barcode amplification in Rubus spp.

Amplification conditions for target sequences: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 34 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The second PCR used 5 cycles at 55 °C annealing followed by 29 cycles at 72 °C, while the third PCR maintained 72 °C annealing throughout. For the second and third PCR we used 1 µL from each previous PCR-product as template DNA. We verified amplification success every PCR by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis for the respective bands (600 bp for rbcL and 715 bp for ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2). After the final PCR (containing barcodes and adapters), we pooled 1 µL from each sample. Gel extraction using Cleanup Mini kit (Eurogen, Moscow, Russia) removed primer dimers from the sequencing-ready library.

Library pools were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads). Initial processing of sequencing data included quality control and read trimming using Trimmomatic v0.39 and FastQC v0.12.1 [70,71]. Adapter sequences and low-quality regions were removed using the ILLUMINACLIP parameter with the NexteraPE-PE.fa adapter library (seed mismatches = 2, palindrome clip threshold = 30, simple clip threshold = 10). Quality filtering involved trimming bases with quality scores below 5 from the ends of reads (LEADING:5, TRAILING:5), as well as sliding window trimming with a 4 bp window requiring an average quality ≥ 15 (SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15). Reads shorter than 50 nucleotides were discarded (MINLEN:50). Data quality before and after trimming was assessed using FastQC, with results aggregated in MultiQC v1.27. Cleaned reads were aligned to reference sequences randomly selected from the NCBI database (AF362705.1 R. caesius for ITS barcode and NC_060616.1 R. trianthus for rbcL barcode) using Bowtie2 v2.4.1 in very sensitive local mode (–very-sensitive-local) [72]. During alignment, unaligned reads (–no-unal) and discordant pairs (–no-discordant) were excluded. Post-processing included converting SAM files to BAM format using samtools v1.6 view, sorting by coordinates with samtools sort, and indexing using samtools index. Coverage analysis was performed by calculating depth at every position, including those with zero coverage, using samtools depth (-a), along with insert size distribution analysis using Picard CollectInsertSizeMetrics. Genetic variant detection was conducted with FreeBayes v1.3.9, applying a minimum base and mapping quality threshold of 20, a minimal alternative allele frequency of 1%, and a minimum coverage depth of 10×. Variant filtering employed bcftools v1.9 [73], including normalization of multiallelic sites (bcftools norm), selection of biallelic variants with QUAL ≥ 20 and alternative allele frequency > 50%. Phasing was performed with WhatsHap v2.8 (currently applied only to ITS markers, with uncertain applicability). Filtered and phased variants were compressed (bgzip) and indexed (bcftools index). Consensus sequences were generated using bcftools consensus. Final alignment and variant validation were visually inspected in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v2.12 [74]. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences was conducted using MEGA v.11.0.13 [75]. Maximum Likelihood trees were reconstructed independently for each locus. For the rbcL dataset (51 accessions), the Jukes–Cantor substitution model was applied with 500 bootstrap replicates. For the combined ITS1 and ITS2 dataset (53 accessions), the Kimura 2-parameter model was used with 100 bootstrap replicates. In both analyses, branches with bootstrap support below 70% were collapsed. Species assignment was based on phylogenetic clustering patterns with reference taxa and sequence divergence estimates, rather than relying solely on a fixed similarity threshold to reference barcodes.

Topographic maps in the article were created using the Datawrapper platform [76].

3. Results

Barcoding was performed on 56 Rubus samples using the chloroplast rbcL marker for 51 samples and the nuclear ITS1 and ITS2 markers for 53 samples. The difference in sample numbers is due to weak amplification (step 1 in Figure 2) of the barcodes in some samples during library preparation for sequencing.

3.1. Analysis of rbcL Barcode

Sequence analysis of the rbcL chloroplast marker showed the predominant uniformity of almost all blackberry samples, including samples collected at a relative distance (90–140 km) from the main area of «Sirius». The analysis revealed the presence of two variants of the rbcL barcode for each sample (plant). Marker differences within the sample were determined based on the read nucleotide at a specific position (Table S2). Three variants of the rbcL marker have been identified for sample 46, where the third variant has a coverage depth of 165 (3.6%). This minor allele in sample 46 corresponds to a sequence showing 98% identity with the rbcL gene of Rubus irritans Focke (NC_057600.1) or R. amabilis Focke (NC_047211.1).

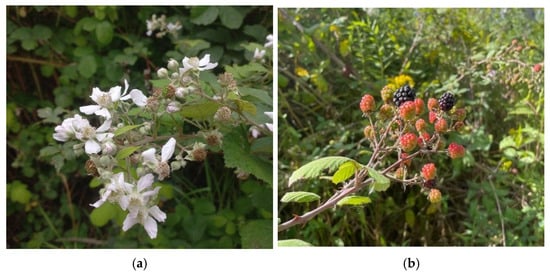

Comparison of consensus barcode sequences with NCBI and BOLD databases identified 38 samples as R. caesius L. (FN689382.1), R. argutus (OR972714.1), R. occidentalis (OR972718.1), and R. tuberculatus Bab. (KX163025.1), showing 100% sequence identity. The rbcL barcode sequences are identical among these species, which explains why these samples cannot be confidently assigned to a single species based on this marker alone. Ten samples exhibited a single nucleotide substitution at position 147 (G→A) relative to R. caesius (FN689382.1). Sample 47 carried a substitution (C→G) at position 189, and sample 39 showed a substitution (C→A) at position 286 (Table 2). More notably, the rbcL barcode of sample 33 matched East Asian species R. corchorifolius L.fil (OP581010.1) and R. chingii var. suavissimus (S.K.Lee) L.T.Lu (NC_083088.1) with 99% identity (1-nucleotide difference). These taxa are native to East Asia (China, Japan, Korea) (Figure 3a,b).

Table 2.

Species-diagnostic nucleotide substitutions in the rbcL gene, where the hyphen sign indicates a match to the nucleotide in the sequence of the Rubus caesius L. gene.

Figure 3.

Morphology of a specimen 33 identified as Rubus corchorifolius L.fil by rbcL barcode: (a) flowering shoots and (b) ripening fruits.

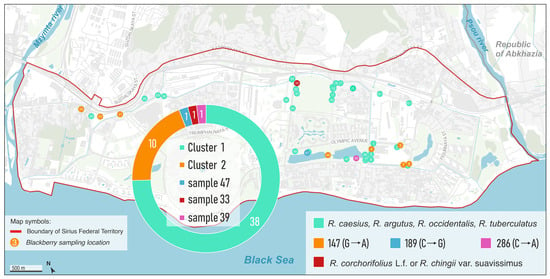

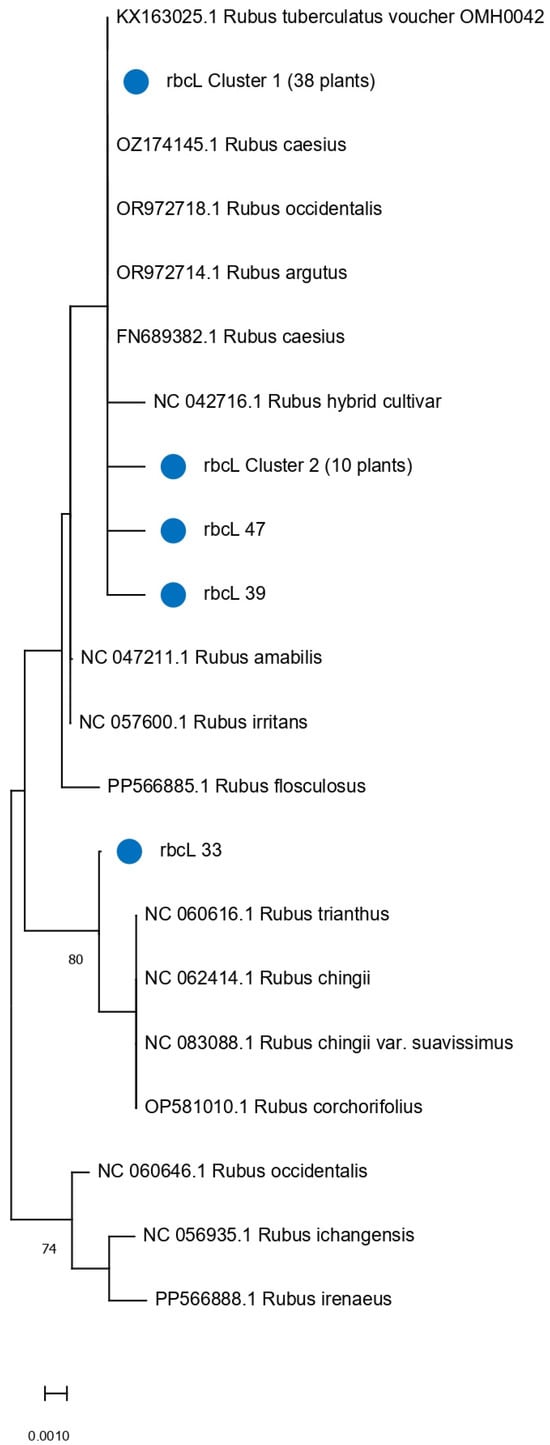

Analysis of the rbcL barcode region revealed genetic clustering among the studied Rubus samples. The sequences were grouped into two main clusters based on nucleotide similarity. The largest cluster, designated Cluster 1, comprised 38 samples, which were evenly distributed across the study area. Samples collected in the Republic of Abkhazia (116, 117, 118, 118-1, 119-4) also belonged to this cluster, indicating continuity of this haplotype beyond the Russian part of the Black Sea coast. In contrast, a second cluster (Cluster 2) containing 10 samples was mainly found in areas that have undergone anthropogenic transformation, including sites along routes of machinery movement where soil disturbance and potential introduction of plant material occurred. Among the Abkhazian accessions, two samples (118-2 and 119-2) were assigned to Cluster 2. Three individual samples—47, 33, and 39—each formed unique singleton clusters, indicating distinct haplotypes within the dataset (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The clear separation into two major clusters suggests the presence of at least two common haplotypes of the rbcL gene within the analyzed germplasm, while the singleton clusters may represent rare or species-specific variants. For determining the species affiliation of nuclear DNA, we targeted the highly variable nuclear markers ITS1 and ITS2, as they offer greater discriminatory power.

Figure 4.

Map of Rubus collection sites, colored according to genetic clusters identified by the rbcL barcode.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree showing relationships among 51 Rubus accessions based on rbcL barcode sequences. The tree was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Jukes–Cantor substitution model. Branch support was evaluated with 500 bootstrap replicates; values below 70% are hidden. Blue circles highlight clusters that group accessions with identical rbcL barcode sequences.

3.2. Analysis of ITS1, ITS2 Barcodes

Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2) in 53 blackberry samples revealed a higher level of variability compared to the rbcL marker. Both single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions/deletions were identified across the two regions (Table S3).

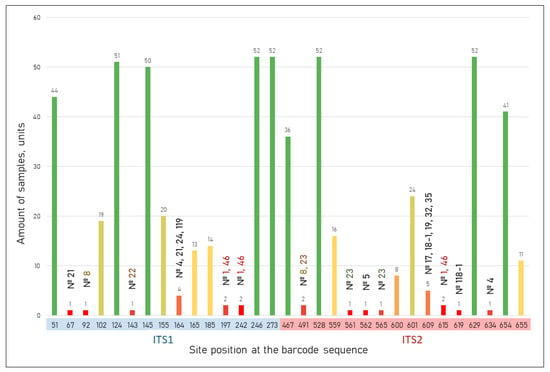

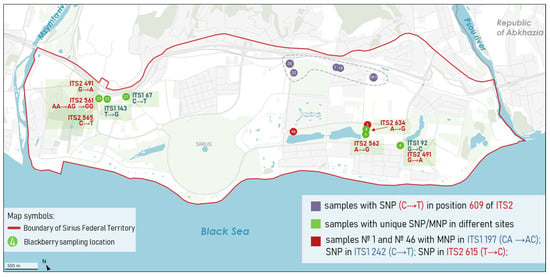

Figure 6 shows the distribution of SNPs and indels across ITS1 and ITS2 regions in 53 Rubus samples. Several positions in ITS1 (124, 145, 246, 273) and ITS2 (528, 629) were shared by more than 50 samples, indicating common and conserved substitutions within the group. Interestingly, sample 8 did not share the most common substitutions found at positions 246, 273, 528, and 629, which were characteristic of the majority. Based on sequence similarity, this sample showed the closest affinity to Rubus caesius L., a species believed to have been originally distributed on the Imereti Lowland. In contrast, many positions were represented by only one or two samples, reflecting rare or unique variants. For example, only sample 21 had a SNP (C→T) at position 67 of ITS1, but it also carried substitutions in conserved sites of ITS1 (124, 145) and in ITS2 (467, 528, 629, 655) (Figure 7, Table S2). Sample 8 showed a unique substitution at site 92 of ITS1 (G→C) and another at position 491 of ITS2 (G→A), similar to sample 23, which also had two additional unique SNPs at sites 561 and 565 (C→T) in ITS2. Samples with unique SNP/MNP sites can be grouped. Thus, the samples within the dashed line in Figure 7 share a C→T substitution at position 609 of ITS2. These samples are located in areas that experienced minimal landscape transformation during the construction of the Olympic facilities, which may have contributed to the preservation of their original genetic composition.

Figure 6.

Distribution of nucleotide substitutions relative to Rubus caesius L. reference. The color of the columns changes from red for the minimum number of samples to green for the maximum number of samples.

Figure 7.

Geographic distribution of blackberry samples with unique SNPs and MNPs in ITS1 and ITS2 regions.

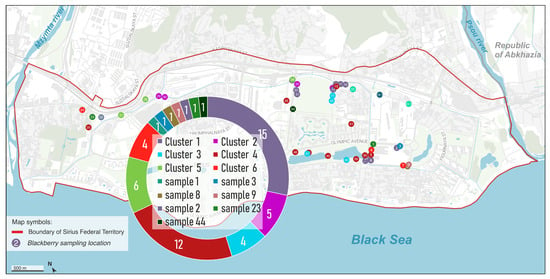

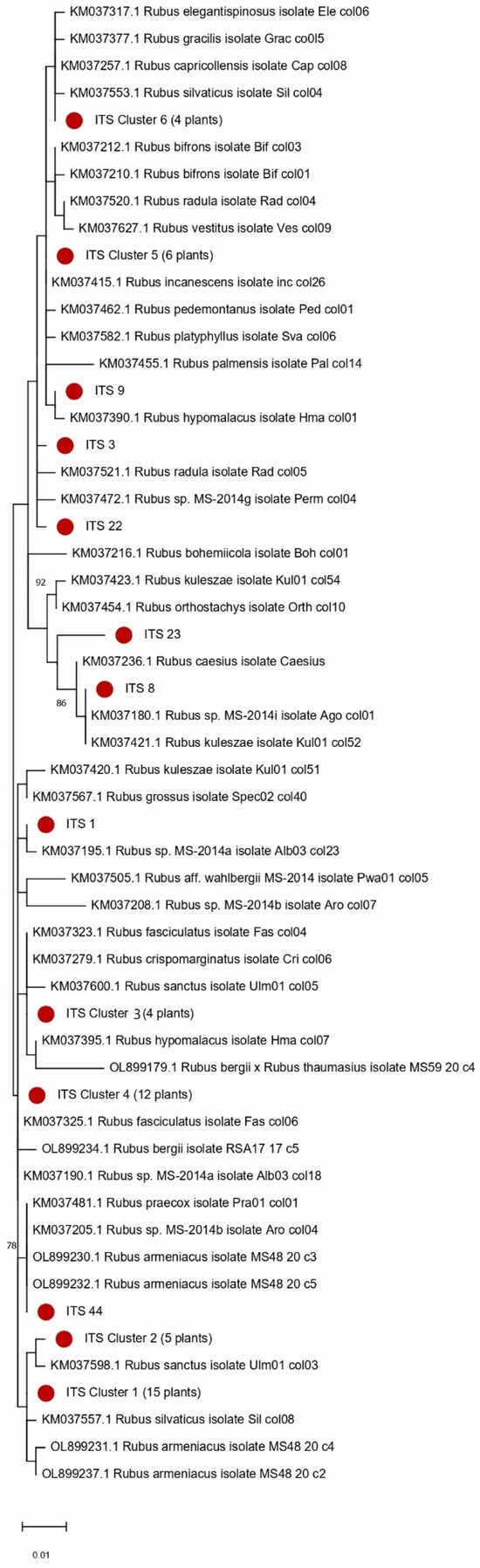

Analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS1 and ITS2) revealed a more complex genetic structure compared to the rbcL barcode. The sequences were grouped into six multi-sample clusters and eight singleton clusters based on nucleotide similarity. The largest cluster 1 contained 15 samples, which were genetically closest to Rubus sanctus Schreb. (Figure 8). Cluster 4 was also substantial, comprising 12 samples. Cluster 5 included six samples (21, 28, 34, 116, 118, 119), while cluster 6 contained four samples (4, 7, 24, 118-1). The remaining multi-sample clusters, Cluster 2 and Cluster 3, consisted of five and four samples, respectively. Additionally, eight samples (1, 3, 8, 9, 22, 23, 44) formed unique singleton clusters, each representing a distinct haplotype (Figure 8). As shown in Figure 8, the spatial distribution of clusters appears to correlate with the degree of landscape modification. Clusters 1, 2, and 3 are mainly found in areas that experienced minimal soil disturbance during the construction of Olympic facilities and are located along the same drainage channel, suggesting preservation of the original genetic structure. In contrast, Cluster 4 tends to occur in zones that underwent more intensive anthropogenic transformation. The increased resolution and higher number of clusters observed with the ITS markers highlight their greater variability and utility for distinguishing closely related Rubus taxa compared to the chloroplast rbcL gene (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Map of Rubus collection sites, colored according to genetic clusters identified by the ITS1, ITS2 barcodes.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of 53 Rubus accessions based on ITS1 and ITS2 barcode sequences. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Kimura 2-parameter substitution model and 100 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap support values below 70% are not shown. Red circles highlight clusters that group accessions with identical ITS1 and ITS2 barcode sequences.

4. Discussion

In the genus Rubus, the combination of hybridization, polyploidy, and apomixis serve as a strong evolutionary engine that accelerates speciation and helps plants expand their ranges [11,41,77]. Apomixis gives an advantage for colonization because it removes the need for pollinators and mating partners, following Baker’s rule [78,79], while polyploidy ensures physiological adaptations to a wide range of environmental conditions [80]. Such a combination is especially beneficial in the variable coastal and foothill environments of the Black Sea region, where climatic and orographic gradients create numerous ecological niches. In many blackberry species, apomixis is facultative, which makes occasional sexual reproduction and recombination possible, helping to preserve genetic diversity while keeping successful genotypes through clonal propagation [43]. This reproductive plasticity explains the persistent ability for interspecific hybridization observed across different Rubus subgenera, including crosses between blackberries (subg. Rubus) and raspberries (subg. Idaeobatus) [10]. An indirect confirmation of this was obtained in the study: in sample 33, the chloroplast gene rbcL most likely belongs to raspberry (R. corchorifolius L.fil.), which indicates the possible formation of a hybrid genotype. At the same time, we detected clusters of samples with identical SNPs/MNPs that were also spatially close (Figure 7). This pattern may reflect localized clonal groups, where somatic mutations are propagated vegetatively within patches. Also, such groups may result from recent hybridization or introgression, where unique substitutions are fixed in descendants of a particular hybrid lineage.

Technically, we applied DNA barcoding, using the plastid marker rbcL and the nuclear ribosomal spacers ITS1 and ITS2, to evaluate their potential for species identification in taxonomically complex group of Rubus [46,81]. The two markers showed different resolution: the rbcL gene was almost uniform across 51 accessions, with only a few variable sites, and most samples clustered with R. caesius, providing low to moderate support and thus weak discrimination of closely related species [51]. In contrast, ITS1 + ITS2 revealed a much higher level of variation, with numerous SNPs and indels that allowed clearer separation of 53 samples. Phylogenetic reconstruction produced well-supported clusters corresponding to reference taxa such as R. bifrons Vest, R. radula Weihe ex Boenn., R. kuleszae Ziel, and R. armeniacus Focke, confirming the higher power of nuclear spacers in Rubus, as also shown for other genera [82]. Overall, DNA barcoding confirmed the dominance of R. caesius and R. sanctus Schreb. on the «Sirius» territory, as the largest clusters formed by both the plastid marker rbcL and the nuclear ITS1–ITS2 barcode corresponded to these taxa. At the same time, the absence of interpretation of allele phasing may have masked some intra-individual variation.

An important observation was that the accessions collected in 140 km (at an altitude of up to 100 m a.s.l.) from the main sampling site in the Sirius Territory, did not form a separate cluster in either rbcL or ITS. This indicates that geographic distance along the Black Sea coast does not necessarily translate into genetic differentiation of blackberry populations. However, collections made in mountainous areas at different altitudes are likely to reveal greater divergence, as altitude is a direct proxy for significant climatic variation [83].

Alongside classical barcoding markers, numerous studies in Rubus demonstrate the strong advantages of SNP datasets for resolving genetic structure, identifying hybridization, and supporting breeding [84,85]. For example, SNP and SSR markers helped evaluate 15 cultivars of R. glaucus and identify promising parental lines for breeding programs, showing their usefulness for selecting productive genotypes [86]. Large genome-wide SNP panels have also enabled the discovery of key loci controlling agronomic traits: in a study of 300 blackberry genotypes, 65,995 SNPs uncovered major QTLs for fruit firmness, defining of postharvest quality [21]. Population-genomic approaches such as RAD-seq have clarified invasion pathways, as shown for R. niveus in the Galápagos, where thousands of SNPs revealed at least two independent introductions and low genetic diversity despite rapid spread [87]. GBS-derived SNPs are also effective for distinguishing mutant and cultivated lines, as demonstrated by the identification of over 19,000 SNPs in boysenberry and blackberry mutants and the development of KASP assays for rapid genotype discrimination [84]. Collectively, these studies show that SNP markers provide high-resolution, genome-wide insight and outperform barcodes for fine-scale population genomics, breeding, and trait mapping.

However, SNP-based approaches require significantly higher sequencing depth, complex bioinformatics, and larger budgets, whereas DNA barcoding relies on a few standard loci and remains the most efficient initial step when sampling poorly studied wild material. Therefore, in the first phase of our project, we applied ITS1, ITS2, and rbcL barcodes to establish species boundaries, detect hybridization signals, and describe broad genetic patterns. At the next stage, we are transitioning to GBS to obtain genome-wide SNP data that will allow for high-resolution analysis of population structure, introgression, and evolutionary dynamics of Rubus across the Black Sea region.

DNA barcoding can be tool for plant genetic resource conservation and biodiversity assessment [88]. Molecular identification of plant taxa enables conservation programs to protect endemic and rare species in their natural habitats and supports evidence-based management of biological invasions. Creating barcode reference libraries facilitates rapid species identification across all development plant stages, particularly when morphological characters are lacking or indistinct [89]. In the case of blackberries, the analysis of sample 33 using the rbcL gene identified it as raspberry (R. corchorifolius L.fil.), a species not native to «Sirius» territory.

5. Conclusions

The study of Rubus plants collected in the federal territory «Sirius» made it possible to analyze genetic diversity using two molecular markers representing plastid and nuclear genomes. The standard chloroplast marker rbcL showed low discriminatory power for distinguishing closely related species and hybrids of Rubus. Nevertheless, most samples were grouped into two dominant clusters and several unique haplotypes.

Analysis of nuclear markers ITS1 and ITS2 revealed a much higher level of genetic polymorphism, allowing for clear separation of both well-known and previously unrecognized taxa. A complex spatial structure of genetic lines was observed, including clusters of clonal groups probably formed through apomixis and vegetative propagation, correlated with the least disturbed construction areas.

Evidence of interspecific hybridization was also detected in sample 33: chloroplast DNA corresponded to raspberry, while nuclear DNA belonged to blackberry. Geographic distance between sampling points did not correlate with genetic divergence, suggesting the absence of isolation within the studied area.

More detailed insight into genetic diversity could be achieved by increasing the number of samples, including those from adjacent sites, and by applying more informative genomic methods, primarily genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS).

The results demonstrate the high informativeness of the ITS1/ITS2 barcoding combination for taxonomic and population-level studies in complex plant groups characterized by frequent hybridization, apomixis, and polyploidy. This work provides a foundation for creating regional genetic catalogues useful for biodiversity monitoring and the detection of invasive and valuable native species. However, it is important to recognize that DNA barcoding, while effective in distinguishing taxa with different barcodes, cannot assert that two plants sharing the same barcode are genetically identical due to unexamined variation in the rest of the genome. Therefore, DNA barcoding should be viewed as a preliminary tool that reveals diversity and guides more detailed genetic analysis. Future taxonomic and population genetic studies will benefit from incorporating additional genomic data such as SNP markers to deepen resolution and our understanding of species boundaries and hybridization dynamics.

Effective implementation of barcoding in urban contexts requires close interdisciplinary collaboration between botanists, who possess knowledge about the locations of plant populations, and municipal services responsible for landscaping and green infrastructure [90]. DNA barcoding can serve as a tool for creating libraries of local flora, including endemic species, allowing landscaping services to quickly identify protected plants in the field [91,92]. Such barcode libraries are especially valuable for identifying species in non-flowering conditions or at early developmental stages, when morphological diagnosis is difficult or impossible.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120869/s1, Table S1: Collection data for the Rubus accessions. Notes: negative elevation values (e.g., −1, −3 m) were recorded for some accessions collected in the low-lying, heavily engineered landscape of the Olympic Park area (Sirius Federal Territory). These values likely reflect both the natural proximity to sea level of the Imeretinskaya Lowland and localized anthropogenic alterations of the terrain (e.g., drainage ditches, excavation sites) during large-scale construction; Table S2: Nucleotide diagnostic characters of Rubus species from Sirius Federal Territory and Republic of Abhazia by rbcL barcode; Table S3: Nucleotide diagnostic characters of Rubus species from Sirius Federal Territory and Republic of Abhazia by ITS1, ITS2 barcodes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.R. and E.K.K.; methodology, I.Y.Z., E.S.T., I.M.P.; software, A.V.K.; validation, I.Y.Z., E.K.K. and A.S.R.; formal analysis, I.Y.Z.; investigation, I.Y.Z., N.A.D., E.N.M., M.T.M. and L.Y.S.; data curation, A.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Y.Z., N.A.D. and E.I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.V.R., E.K.K. and A.S.R.; visualization, I.Y.Z.; supervision, E.K.K. and A.S.R.; project administration, A.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation No. 24-16-20042, https://rscf.ru/project/24-16-20042/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. The raw sequencing reads are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Andrey Manakhov for technical support and David Seturidze for graphic illustration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ITS1 | Internal Transcribed Spacer 1 |

| ITS2 | Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 |

| rbcL | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| MNP | Multi-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| GBS | Genotyping-by-Sequencing |

| RAD-seq | Restriction-site Associated DNA sequencing |

| a.s.l. | Above sea level |

References

- Magurran, A.E.; McGill, B.J. Biological Diversity: Frontiers in Measurement and Assessment; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 0-19-157684-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wäldchen, J.; Mäder, P. Plant Species Identification Using Computer Vision Techniques: A Systematic Literature Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2018, 25, 507–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, A.E.; Hart, A.G. Applied Ecology: Monitoring, Managing, and Conserving; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 0-19-872328-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, S.B.; Wu, C.-H.; Kamoun, S. Overcoming Plant Blindness in Science, Education, and Society. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focke, W.O. Species Ruborum. Monographiae Generis Rubi Prodromus; E. Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Manghwar, H.; Hu, W. Study on Supergenus Rubus L.: Edible, Medicinal, and Phylogenetic Characterization. Plants 2022, 11, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Chen, J.; Hummer, K.E.; Alice, L.A.; Wang, W.; He, Y.; Yu, S.; Yang, M.; Chai, T.; Zhu, X.; et al. Phylogeny of Rubus (Rosaceae): Integrating Molecular and Morphological Evidence into an Infrageneric Revision. Taxon 2023, 72, 278–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, T.K.; Kattukunnel, J.J.; Bharathi, B.L.; Ramaiyan, K. Rubus. In Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 179–196. ISBN 978-3-642-16056-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkman, C. The Phylogeny of the Rosaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1988, 98, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.A.; Liston, A.; Bassil, N.V.; Alice, L.A.; Bushakra, J.M.; Sutherland, B.L.; Mockler, T.C.; Bryant, D.W.; Hummer, K.E. Target Capture Sequencing Unravels Rubus Evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janick, J. (Ed.) Plant Breeding Reviews; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007; Volume 29, ISBN 978-0-470-05241-9. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, T.M.; Bassil, N.V.; Dossett, M.; Leigh Worthington, M.; Graham, J. Genetic and Genomic Resources for Rubus Breeding: A Roadmap for the Future. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnev, A.M.; Antonova, O.Y.; Dunaeva, S.E.; Gavrilenko, T.A.; Chukhina, I.G. Molecular Markers in the Genetic Diversity Studies of Representatives of the Genus Rubus L. and Prospects of Their Application in Breeding. Vestn. VOGiS 2020, 24, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Dossett, M.; Finn, C.E. Rubus Fruit Phenolic Research: The Good, the Bad, and the Confusing. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaume, L.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. The Blackberry Fruit: A Review on Its Composition and Chemistry, Metabolism and Bioavailability, and Health Benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5716–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummer, K.E. Rubus Diversity. HortScience 1996, 31, 182–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alice, L.A.; Campbell, C.S. Phylogeny of Rubus (Rosaceae) Based on Nuclear Ribosomal DNA Internal Transcribed Spacer Region Sequences. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H.; et al. Allopolyploid Origin in Rubus (Rosaceae) Inferred from Nuclear Granule-Bound Starch Synthase I (GBSSI) Sequences. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanBuren, R.; Bryant, D.; Bushakra, J.M.; Vining, K.J.; Edger, P.P.; Rowley, E.R.; Priest, H.D.; Michael, T.P.; Lyons, E.; Filichkin, S.A.; et al. The Genome of Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis). Plant J. 2016, 87, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brůna, T.; Aryal, R.; Dudchenko, O.; Sargent, D.J.; Mead, D.; Buti, M.; Cavallini, A.; Hytönen, T.; Andrés, J.; Pham, M.; et al. A Chromosome-Length Genome Assembly and Annotation of Blackberry (Rubus argutus, Cv. “Hillquist”). G3 2023, 13, jkac289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizk, T.M.; Clark, J.R.; Johns, C.; Nelson, L.; Ashrafi, H.; Aryal, R.; Worthington, M.L. Genome-Wide Association Identifies Key Loci Controlling Blackberry Postharvest Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1182790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Parrish, S.B.; Peng, Z.; Parajuli, S.; Deng, Z. A Chromosome-Scale and Haplotype-Resolved Genome Assembly of Tetraploid Blackberry (Rubus L. Subgenus Rubus Watson). Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Hsu, T.-W.; Kim, S.-H.; Pak, J.-H.; Kim, S.-C. Characterization and Comparative Analysis among Plastome Sequences of Eight Endemic Rubus (Rosaceae) Species in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, J.; Fang, Y.; Xiang, J.; Dong, H. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Rubus Species (Rosaceae) and Comparative Analysis within the Genus. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Tian, Q.; Gu, W.; Yang, C.-X.; Wang, D.-J.; Yi, T.-S. Comparative Genomics on Chloroplasts of Rubus (Rosaceae). Genomics 2024, 116, 110845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarhanová, P.; Sharbel, T.F.; Sochor, M.; Vašut, R.J.; Dančák, M.; Trávníček, B. Hybridization Drives Evolution of Apomicts in Rubus Subgenus Rubus: Evidence from Microsatellite Markers. Ann. Bot. 2017, 120, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, J. Hybridization as an Invasion of the Genome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulet, B.E.; Roda, F.; Hopkins, R. Hybridization in Plants: Old Ideas, New Techniques. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, K.D.; Ahern, J.R.; Campbell, L.G.; Albert, L.P.; King, M.S. Patterns of Hybridization in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 12, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, M.; Li, S.; Tao, M.; Ye, X.; Duan, W.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Q.; Xiao, J.; Liu, S. A Comparative Study of Distant Hybridization in Plants and Animals. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Hiscock, S.J.; Filatov, D.A. The Role of Interspecific Hybridisation in Adaptation and Speciation: Insights From Studies in Senecio. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 907363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Yan, C. Cytological Observation of Distant Hybridization Barrier and Preliminary Investigation of Hybrid Offspring in Tea Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Gonzalez, A.; Lexer, C.; Cronk, Q.C.B. Adaptive Introgression: A Plant Perspective. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20170688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.H. Apomixis, Hybridization, and Speciation in Rubus. Castanea 1958, 23, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. The Role of Hybridization in Plant Speciation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.S.; Arrigo, N.; Baniaga, A.E.; Li, Z.; Levin, D.A. On the Relative Abundance of Autopolyploids and Allopolyploids. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieseberg, L.H.; Raymond, O.; Rosenthal, D.M.; Lai, Z.; Livingstone, K.; Nakazato, T.; Durphy, J.L.; Schwarzbach, A.E.; Donovan, L.A.; Lexer, C. Major Ecological Transitions in Wild Sunflowers Facilitated by Hybridization. Science 2003, 301, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigham, C.A. Population Viability in Plants: Conservation, Management, and Modeling of Rare Plants; Springer Science & Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 165, ISBN 3-540-43909-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schumer, M.; Rosenthal, G.G.; Andolfatto, P. How common is homoploid hybrid speciation? perspective. Evolution 2014, 68, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, H.; Hess, J.; Pickup, M.; Field, D.L.; Ingvarsson, P.K.; Liu, J.; Lexer, C. Evolution of Strong Reproductive Isolation in Plants: Broad-Scale Patterns and Lessons from a Perennial Model Group. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, H. Hybrid Fertility and the Rarity of Homoploid Hybrid Speciation. AoB Plants 2025, 17, plaf035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoar, C.S. Sterility as the Result of Hybridization and the Condition of Pollen in Rubus. Bot. Gaz. 1916, 62, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochor, M.; Vašut, R.J.; Sharbel, T.F.; Trávníček, B. How Just a Few Makes a Lot: Speciation via Reticulation and Apomixis on Example of European Brambles (Rubus Subgen. Rubus, Rosaceae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2015, 89, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckle, M. Taxonomy, DNA, and the Bar Code of Life. BioScience 2003, 53, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; deWaard, J.R. Biological Identifications through DNA Barcodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOL Plant Working Group. A DNA Barcode for Land Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12794–12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xue, J.; Zhou, S. New Universal matK Primers for DNA Barcoding Angiosperms. J. Sytemat. Evol. 2011, 49, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckenhauer, J.; Barfuss, M.H.J.; Samuel, R. Universal Multiplexable matK Primers for DNA Barcoding of Angiosperms. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016, 4, 1500137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y. Authentication of Small Berry Fruit in Fruit Products by DNA Barcoding Method. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, M.W.; Salamin, N.; Wilkinson, M.; Dunwell, J.M.; Kesanakurthi, R.P.; Haidar, N.; Savolainen, V. Land Plants and DNA Barcodes: Short-Term and Long-Term Goals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2005, 360, 1889–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yao, H.; Han, J.; Liu, C.; Song, J.; Shi, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, T.; Pang, X.; et al. Validation of the ITS2 Region as a Novel DNA Barcode for Identifying Medicinal Plant Species. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, B.; Yao, H.; Song, J.; Chen, S.; Meng, F. The Short ITS2 Sequence Serves as an Efficient Taxonomic Sequence Tag in Comparison with the Full-Length ITS. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 741476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Song, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, L.; Chen, S. Applying Plant DNA Barcodes for Rosaceae Species Identification. Cladistics 2011, 27, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopopova, M.; Pavlichenko, V.; Gnutikov, A.; Chepinoga, V. DNA Barcoding of Waldsteinia Willd. (Rosaceae) Species Based on ITS and trnH-psbA Nucleotide Sequences. In Information Technologies in the Research of Biodiversity; Bychkov, I., Voronin, V., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 107–115. ISBN 978-3-030-11719-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barcode ID–BOLD. Available online: https://id.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Chen, S. Using DNA Barcodes to Identify Rosaceae. Planta Med. 2009, 75, P-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, D.; Tregubov, O. The Potential of the Imeretinsky Valley’s Natural Conditions for Introduction of Tropical Plants. For. Eng. J. 2015, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbinina, V.G.; Belyuchenko, I.S. The impact of the 2014 Olympics on the state of vegetation in the Imereti lowland. Ecol. Bull. North Cauc. 2009, 5, 5–12. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gallien, L.; Carboni, M. The Community Ecology of Invasive Species: Where Are We and What’s Next? Ecography 2017, 40, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalusová, V.; Chytrý, M.; Van Kleunen, M.; Mucina, L.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Pergl, J.; Weigelt, P.; Winter, M.; et al. Naturalization of European Plants on Other Continents: The Role of Donor Habitats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13756–13761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.; Haeuser, E.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Kreft, H.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P.; Weigelt, P.; Winter, M.; Lenzner, B.; et al. Naturalization of Ornamental Plant Species in Public Green Spaces and Private Gardens. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3613–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D.F.; Gaines, S.D. Species Invasions and Extinction: The Future of Native Biodiversity on Islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11490–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochi Weather Averages–Krasnodar, RU. Available online: https://www.worldweatheronline.com/sochi-weather-averages/krasnodar/ru.aspx (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- 68Sukhumi Weather Averages–Abkhazia, GE. Available online: https://www.worldweatheronline.com/sukhumi-weather-averages/abkhazia/ge.aspx (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Cruaud, P.; Rasplus, J.-Y.; Rodriguez, L.J.; Cruaud, A. High-Throughput Sequencing of Multiple Amplicons for Barcoding and Integrative Taxonomy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. A Guide Methods Appl. 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri, L.; Lorusso, L.; Mottola, A.; Intermite, C.; Piredda, R.; Di Pinto, A. Authentication of the Botanical Origin of Honey: In Silico Assessment of Primers for DNA Metabarcoding. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 15429–15442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, R.A.; Wagner, W.L.; Hoch, P.C.; Nepokroeff, M.; Pires, J.C.; Zimmer, E.A.; Sytsma, K.J. Family-level Relationships of Onagraceae Based on Chloroplast Rbc L and Ndh F Data. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FASTQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-Performance Genomics Data Visualization and Exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013, 14, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashboard–Datawrapper. Available online: https://app.datawrapper.de/cbyMOkkSlb (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cervantes-Díaz, C.I.; Oyama, K.; Cuevas, E. Ecological and Evolutionary Implications of Hybridization, Polyploidy and Apomixis in Angiosperms. Bot. Sci. 2024, 102, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.G. Self-Compatibility and Establishment after ’long-Distance’ dispersal. Evolution 1955, 9, 347–349. [Google Scholar]

- Cheptou, P.-O. Clarifying Baker’s Law. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.V.; Jasieniuk, M. Spontaneous Hybrids between Native and Exotic Rubus in the Western United States Produce Offspring Both by Apomixis and by Sexual Recombination. Heredity 2012, 109, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, A.J.; Burgess, K.S.; Kesanakurti, P.R.; Graham, S.W.; Newmaster, S.G.; Husband, B.C.; Percy, D.M.; Hajibabaei, M.; Barrett, S.C.H. Multiple Multilocus DNA Barcodes from the Plastid Genome Discriminate Plant Species Equally Well. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Luo, K.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Pang, X.; Xu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, P.; et al. Use of ITS2 Region as the Universal DNA Barcode for Plants and Animals. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, M.; Suga, M. Ambiguous Species Boundaries: Hybridization and Morphological Variation in Two Closely Related Rubus Species along Altitudinal Gradients. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 7476–7486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kim, W.J.; Im, J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.-S.; Jo, H.-J.; Kim, E.-Y.; Kang, S.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Ha, B.-K. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Based Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Enabled Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR Marker Development in Mutant Rubus Genotypes. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 35, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, I.Y.; Menkov, M.T.; Markova, E.N.; Dobarkina, N.A.; Evlash, A.Y.; Shipilina, L.Y.; Rozanov, A.S. Current Methods for Identifying Plant Hybrids: A Case Study of Blackberry. Proc. Appl. Bot. Genet. Breed. 2025, 186, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.M.; Barrera, C.F.; Marulanda, M.L. Evaluation of SSR and SNP Markers in Rubus Glaucus Benth Progenitors Selection. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2019, 41, e-081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijos, C.E.; Cerca, J.; Alarcón-Bolaños, P.; Torres, M.D.L. Population Genomics of the Invasive Blackberry (Rubus niveus) in the Galapagos Islands. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiou, A.; Aconiti Mandolini, L.; Piredda, R.; Bellarosa, R.; Simeone, M.C. DNA Barcoding as a Complementary Tool for Conservation and Valorisation of Forest Resources. ZooKeys 2013, 365, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, D.; Park, J.-I.; Chung, M.-Y.; Cho, Y.-G.; Ramalingam, S.; Nou, I.-S. Utility of DNA Barcoding for Plant Biodiversity Conservation. Plant Breed. Biotech. 2013, 1, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, E.M.; Kuzma, F.C.; Enander, H.D.; Cole-Wick, A.; Coury, M.; Cuthrell, D.L.; Johnson, C.; Kelso, M.; Lee, Y.M.; Methner, D.; et al. Assessing Habitat Connectivity of Rare Species to Inform Urban Conservation Planning. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, R.D.; Stewart, R.D.; Niemann, H.J.; Olaniyan, O.D.; Van Der Bank, M. Leafing through Genetic Barcodes: An Assessment of 14 Years of Plant DNA Barcoding in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 172, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Deng, Y.-F.; Yan, H.-F.; Lin, Z.-L.; Delgado, A.; Trinidad, H.; Gonzales-Arce, P.; Riva, S.; Cano-Echevarría, A.; Ramos, E.; et al. Flora Diversity Survey and Establishment of a Plant DNA Barcode Database of Lomas Ecosystems in Peru. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).