Abstract

Pseudoscorpions collected from the remote southeast Pacific Island of Motu Motiro Hiva (also known as Isla Salas y Gómez) yielded two different species. A juvenile specimen of the genus Garypus (Garypidae) was found near the seashore, which represents the most southerly record of Garypus in the Pacific Ocean. Numerous specimens of an unusual chernetid were taken from inside mummified carcasses of seabirds that breed on the island. Although they show morphological similarities to some other American genera such as Americhernes Muchmore, Cordylochernes Beier, and Lustrochernes Beier, the gaping fingers on the male chela and the positions of the trichobothria clearly differentiate them from all other genera. We therefore propose the new genus and species Motuchernes spatiodigitus sp. nov., which is endemic to this small remote and isolated island.

1. Introduction

The pseudoscorpion fauna of the islands of the southern Pacific Ocean is imperfectly known, with a mixture of apparently endemic and widely distributed species (Table S1). The species with the largest distribution, Geogarypus longidigitatus (Rainbow, 1897), occurs from southeast Asia to Rapa Nui, which has been suggested to be due to inadvertent transportation by humans [1,2]. This species is the only pseudoscorpion recorded from Rapa Nui and Pitcairn Island. There are four species recorded from French Polynesia, but none are endemic to this large group of islands. At the other end of the spectrum, the fauna of the Juan Fernández Islands consists of thirteen endemic species and one species that is also found in Argentina [3,4,5]. Seven hundred and eighty kilometres north of this archipelago are the Islas Desventuradas, which host two endemic species not recorded since their original description [6,7]. Most of these species seem to have their affinities with South America, due to the presence of congeneric species in the temperate regions of the Neotropical realm [8].

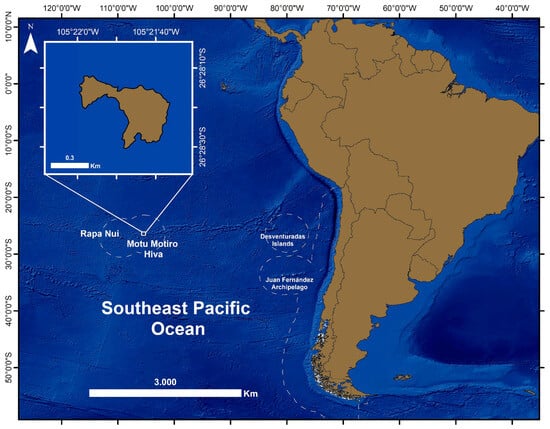

In light of these distributional patterns, the poorly known terrestrial invertebrate fauna of Motu Motiro Hiva (MMH, Figure 1) offers an important case study from both a pseudoscorpion-centric and broader arthropod community perspective. The extreme isolation and small size of this islet may render it of high ecological significance. Designated a Nature Sanctuary in 1976, scientific attention has largely focused on its surrounding marine ecosystems, now part of the Motu Motiro Hiva Marine Park. This marine ecosystem exhibits remarkably high endemism [9]. However, the terrestrial arthropod fauna has not been closely examined.

Figure 1.

Map of the southern Pacific Ocean showing the location of Motu Motiro Hiva (Isla Salas y Gómez). Dotted lines indicate the Chilean Exclusive Economic Zones.

Recent investigations have started to document the island’s broader community, revealing both endemic and more cosmopolitan taxa. Notably, the tube-dwelling spider Ariadna motumotirohiva Giroti, Cotoras, Lazo & Brescovit, 2020 (Segestriidae) is the most recently described endemic species [10,11], while the terrestrial isopod Hawaiioscia rapui Taiti & Wynne, 2015 (Philosciidae), endemic to Rapa Nui and MMH, has drawn interest for its potential dispersal mechanisms—rafting on vegetation and human-aided introduction by early Polynesian wayfarers or possibly contemporary mariners [2,12,13]. The possibility of additional undescribed species is highly relevant for pseudoscorpions, which may occupy discrete and cryptic microhabitats, such as seabird nests, and are notoriously difficult to detect and study. Recent work has underscored the conservation value of such specialised habitats; for example, Sharp and Gray [14] emphasised the role of microrefugia in sustaining highly threatened, island-endemic arthropods.

In addition to known endemics and the likelihood for additional undescribed species, three broad distributed taxa have been documented on MMH. The cosmopolitan springtail, Entomobrya atrocincta Schott, 1896 (Entomobryidae), occurs on both MMH [11] and Rapa Nui [2]. Identified as a Nearctic species [2], this collembolan has also been confirmed in Europe, New Zealand [15], Australia [16], Brazil [17], and Colombia [18]. The second cosmopolitan species, Cryptamorpha desjardinsi (Guérin-Méneville, 1844) (Silvanidae, Coleoptera; see [19]), also occurs on Rapa Nui [20]. Finally, the third species, Lynchia americana (Leach, 1817) (Hippoboscidae) [11], an avian parasite with a principally Nearctic distribution, has also been reported in the Southern Hemisphere [21]. Entomobrya atrocincta and Cryptamorpha desjardinsi may have arrived due to contemporary (but infrequent) marine traffic, while Lynchia americana likely reached the islet phoretically on pelagic birds.

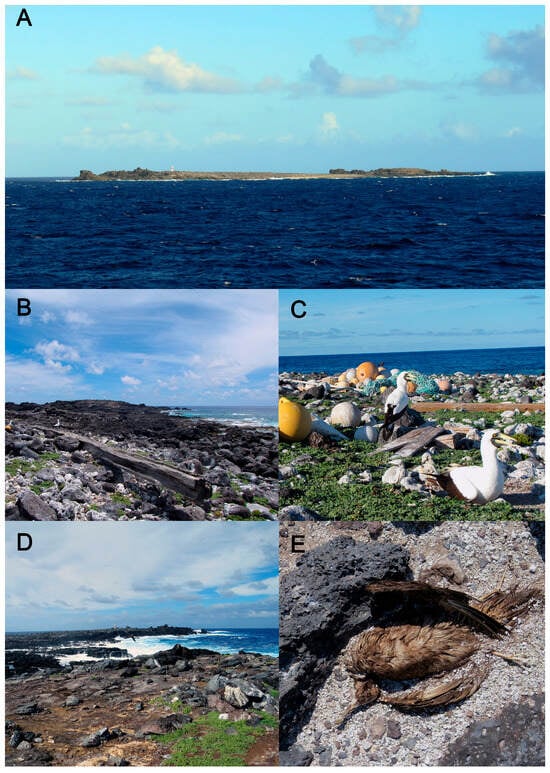

MMH is an islet, with an area of 17 hectares and greatest length of 730 m, with its highest point only 30 m above sea level (Figure 2A). It is the summit of a large volcanic seamount and, along with Rapa Nui, is part of the Salas y Gómez Ridge [22]. Rapa Nui, the nearest landmass, is situated 400 km to the west of MMH and is significantly larger (163 km2) and higher, with an elevation of 511 m.

Figure 2.

Landscape and ecological features of Motu Motiro Hiva. (A) Panoramic view of the island. The lighthouse visible in the image is 6 m tall. (B) Driftwood deposited in MMH by ocean currents. (C) Nesting masked boobies (Sula dactylatra) among marine debris. (D) Western shoreline of the island. (E) Mummified seabird carcass, from which chernetids were collected.

Recent collecting on MMH has recovered two different pseudoscorpion species, neither of which have been previously described. The first is an apparently undescribed species of Garypus L. Koch, 1873 of the family Garypidae. Garypus species tend to be rather large and only found in supralittoral zones of seashore environments around the world, e.g., [23]. The second is a large species of Chernetidae that resembles the neotropical genera Cordylochernes Beier, 1932, and Lustrochernes Beier, 1932, but differs in the disposition of the trichobothria and the gaping chelal fingers. Chernetid pseudoscorpions are highly diverse globally, and their taxonomy is often confusing, especially in the Neotropics. Hlebec et al. [24] presented a preliminary phylogeny of Chernetidae, including 21 of the 120 genera; the results supported two of the three proposed subfamilies, Lamprochernetinae and Chernetinae, but more extensive sampling is required to elucidate a more comprehensive status of the family. In this sense, the inclusion of the specimens found on the Motu Motiro Hiva in a phylogenetic analysis provides additional insights into the origins of the island fauna.

2. Materials and Methods

Specimens examined for this study are lodged in the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Santiago, Chile (MNHN), the Sala de Colecciones Biológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile (SCBUCN), and Colección de Flora y Fauna Profesor Patricio Sánchez Reyes, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile (SSUC), and the Western Australian Museum, Perth (WAM).

The specimens were studied using temporary slide mounts prepared by immersion of the specimen in lactic acid at room temperature for several hours to days and mounting them on microscope slides with 10 or 12 mm coverslips supported by small sections of 0.25, 0.35, or 0.5 mm diameter nylon fishing line. After study, the specimens were rinsed in water and returned to 75% ethanol with the dissected portions placed in 12 × 3 mm glass genitalia microvials (BioQuip Products, Inc., Gardena, CA, USA). Specimens were examined with a Leica MZ–16A (Wetzlar, Germany) dissecting microscope and an Olympus BH–2 (Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) or a Leica DM2500 (Wetzlar, Germany) compound microscope, the latter fitted with interference contrast and illustrated with the aid of a drawing tube attached to the compound microscopes. Measurements were taken at the highest possible magnification using an ocular graticule.

Terminology and mensuration mostly follow Chamberlin [25], except for the nomenclature of the pedipalps and legs and with some minor modifications to the terminology of the trichobothria [26], chelicera [27], and faces of the appendages [28].

Molecular Methods

Fragments of one mitochondrial and two nuclear genes were sequenced using standard Sanger methodology, as outlined in recent studies on pseudoscorpions (e.g., [23,29,30,31,32]). This included cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), 18S ribosomal RNA (18S), and 28S ribosomal RNA (28S). Molecular methods used for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of each of these genes followed Harvey et al. [23,29,30,31,32], with PCR purification and Sanger bidirectional sequencing conducted by the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF; Perth, Australia). The primers used are listed in Table 1. Chromatograms were edited using the Geneious software package (ver. 2021.2, Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand; https://www.geneious.com/ accessed on 10 February 2024), and resulting nucleotide sequences for all taxa are deposited in GenBank (Tables S2 and S3). The sequences were aligned using the MAFFT version 7.490 [33,34] plug-in within Geneious with the default settings. The concatenated alignments were analysed using the maximum likelihood (ML) methodology in the web version of IQ-TREE ver. 2.2.0 [35,36]. The substitution model option was set at Auto, and the branch support analysis was performed with 5000 ultrafast bootstrap alignments.

Table 1.

Primers used in the amplification and sequencing of DNA in this study.

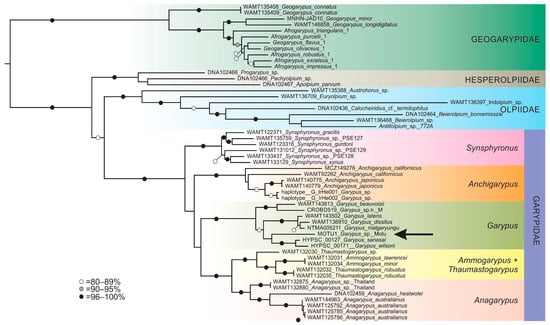

Two different analyses were performed. The first compared the sequence obtained from the Garypus specimen with as many other sequences of the subfamily Garypinae (Garypus and Anchigarypus) as we could obtain (Table S2). This analysis included a variety of outgroups including species from the subfamily Synsphyroninae (Garypidae) and the families Geogarypidae, Hesperolpiidae and Olpiidae. It was rooted on Neobisium carcinoides (Hermann, 1804) of the family Neobisiidae, which was excluded from the phylogram (Figure 3) for clarity. A total of 3536 aligned base pairs (bp) were analysed, including 655 bp for COI, 1750 bp for 18S and 1131 bp for 28S. The best-fit models according to Bayesian information criterion scores were TIM+F+I+G4 (COI), TNe+I+G4 (18S), and TIM3+F+I+G4 (28S) (see Supplementary Material File S1 for details).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of Garypoidea, based on alignment of concatenated COI, 18S and 28S. Bootstrap values are presented for each node. The position of the nymphal specimen of Garypus from Motu Motiro Hiva is denoted with an arrow.

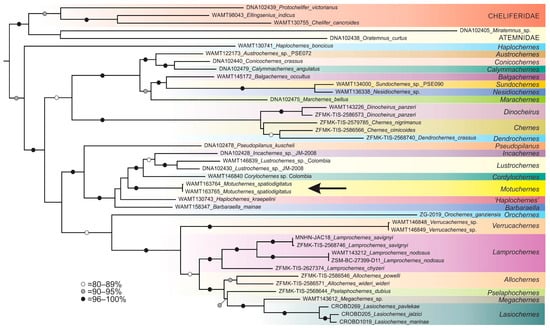

The second analysis compared sequences obtained from the new genus with the majority of the dataset compiled by Hlebec et al. [24] plus the addition of sequences obtained from taxa that are morphologically similar to the new genus, including newly sequenced specimens of Cordylochernes Beier, 1932 and Lustrochernes Beier, 1932 from Colombia (Table S3). Several outgroups from the other three families of Cheliferoidea were added, including Miratemnus sp. and Oratemnus curtus (Beier, 1954) from the family Atemnidae, and Chelifer cancroides (Linnaeus, 1758), Ellingsenius indicus Chamberlin, 1931 and Protochelifer victorianus Beier, 1966 from the family Cheliferidae. The analysis was rooted on Afrosternophorus sp. of the family Sternophoridae, which was excluded from the phylogram (Figure 4) for clarity. A total of 3697 aligned base pairs (bp) were analysed, including 655 bp for COI, 1807 bp for 18S and 1235 bp for 28S. The best-fit models according to Bayesian information criterion scores were TIM+F+I+G4 (COI), TNe+I+G4 (18S), and TIM3+F+I+G4 (28S) (see Supplementary Material File S1 for details).

Figure 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny of Chernetidae, based on alignment of concatenated COI, 18S, and 28S. Bootstrap values are presented for each node. The position of Motuchernes spatiodigitus sp. nov. is denoted with an arrow.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Phylogenetics

Sequence data from the juvenile Garypus specimen from Motu Motiro Hiva places it in a clade with two species recently described from Taiwan, G. sanasai Lin and Chang, 2022 and G. wilsoni Lin and Chang, 2022 [40], although the support values are extremely low (Figure 3). Little confidence can be placed in this interpretation, as so few species of the 38 described species of Garypus are represented by sequence data, and most importantly, none are from the Americas.

The two sequenced specimens of Motuchernes were recovered within a group of genera that also included Barbaraella Harvey, 1995, Cordylochernes Beier, 1932, Incachernes Beier, 1933, Lustrochernes Beier, 1932, and Haplochernes kraepelini (Tullgren, 1905) (Figure 4). This clade was also recovered by Hlebec et al. [24] and is morphologically distinct from other chernetids by the tightly grouped setae of the female anterior genital operculum (sternite II) (Figure 9E). Motuchernes is recovered as the sister group to the clade Cordylochernes + Incachernes + Lustrochernes, but the low support values for many of the nodes severely reduces the confidence in the topology (Figure 4). The fact that Motuchernes does not group with the widespread and diverse genus Lustrochernes suggests that Motuchernes is unlikely to simply represent a highly modified island representative of this genus. The resulting phylogeny supports the distinctiveness of the genus Motuchernes, despite the small number of taxa included in the analysis.

3.2. Systematics

Family Garypidae Simon, 1879

Subfamily Garypinae Simon, 1879

Genus Garypus L. Koch, 1873

Type species. Garypus litoralis L. Koch, 1873 (junior synonym of Chelifer beauvoisii Audouin, 1826), by subsequent designation of Simon [41].

Remarks. Garypus is a widely distributed genus with 38 named species which are mainly found in tropical ecosystems, with northerly extensions into the Mediterranean region and Taiwan in the Old World, and México and Florida in the New World. Like its sister-genus Anchigarypus Harvey, 2020, all species are restricted to supralittoral seashore habitats [23]. Previous records of Garypus species in the eastern Pacific Ocean are restricted to the Galápagos Islands, where Garypus granosus Mahnert, 2014 has been found on six different islands [42], which are geographically closest to Motu Motiro Hiva. Currently, the only records of Garypus in South America are along the Caribbean coast and its nearby islands, where several species occur in Colombia (G. viridans Banks, 1909), Aruba (G. realini Wagenaar-Hummelinck, 1948), Bonaire (G. bonairensis Beier, 1936), and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (G. withi Hoff, 1946) [8].

The occurrence of a population of Garypus on Motu Motiro Hiva extends the distribution of the genus 3200 km southwest of the previous most southerly record of the genus on the Galápagos Islands [42].

The identity of the population found on Motu Motiro Hiva is unclear due to the lack of adult specimens but based on various morphological features of the nymphal specimens, it most likely represents an undescribed species. Its affinities with other species such as G. granosus will rely on sequence data becoming available for the American fauna, which are currently completely lacking.

Garypus sp.

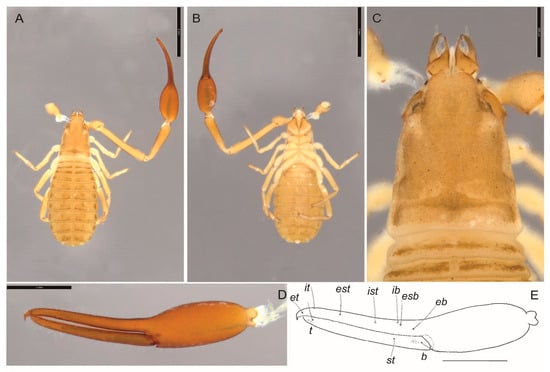

(Figure 5A–E)

Figure 5.

Garypus sp., tritonymph (MNHN): (A) dorsal; (B) ventral; (C) cephalothorax; (D,E) left chela, lateral. Scale lines = 2 mm (A,B), 0.5 mm (C), 1 mm (D,E).

Garypus sp.: [11] Figure 3a.

Material examined. CHILE: Valparaíso Province: 1 tritonymph, Motu Motiro Hiva (Salas y Gómez Island), 26°28′18.1″ S, 105°21′41.1″ W, 23 August 2016, S.Y. Pakarati, J.J. Wynne (MNHN).

Remarks. The sole Garypus specimen collected from Motu Motiro Hiva is a tritonymph which precludes accurate identification at the species level. However, it possesses a highly unusual feature that is not found in any other species of Garypus, where trichobothrium ist is not situated adjacent to ib (Figure 5E) but is located midway along the fixed chelal finger. If this attribute is ultimately confirmed in adults, it would represent a remarkable difference to other species.

Family Chernetidae Menge, 1855

Subfamily Chernetinae Menge, 1855

Genus Motuchernes, gen. nov.

ZooBank Registration:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:504CF465-BA67-4532-9CB8-9FD3086FA33A

Type species. Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov.

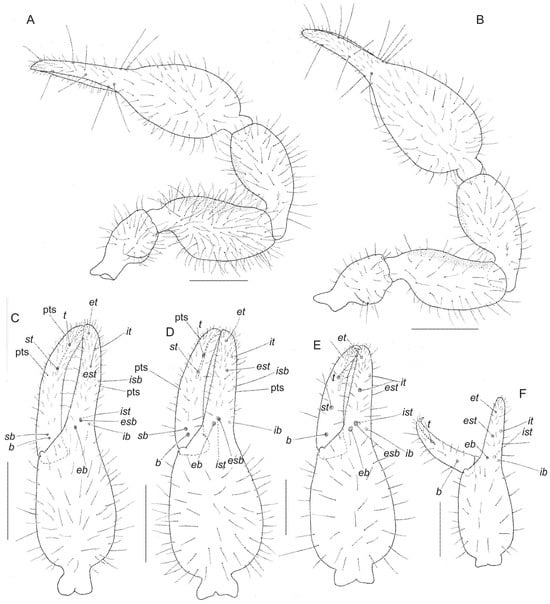

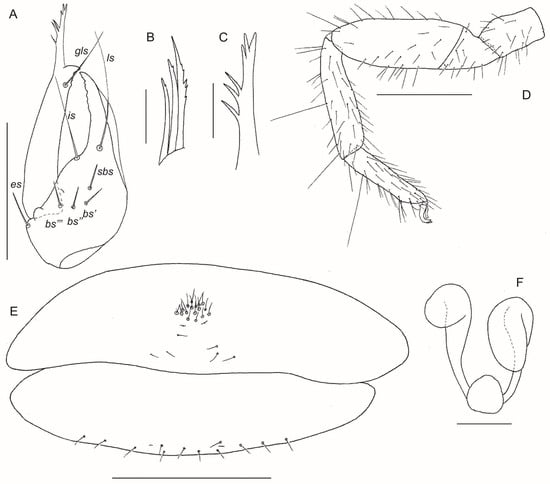

Diagnosis. Motuchernes most closely resemble Lustrochernes and its putative American relatives including Americhernes Muchmore, 1976, Cordylochernes Beier, 1932, Gomphochernes Beier, 1932, Incachernes Beier, 1933, Lustrochernes Beier, 1932, and Odontochernes Beier, 1932 by the presence of long ‘pseudotactile’ setae on the patellae and tibiae of legs III and IV (Figure 9D) and the subdistal position of trichobothrium it, which is located distal to est (Figure 8C,D). It differs from these genera by the position of trichobothrium st which is situated much closer to t than to sb (Figure 8C,D), by the position of trichobothria b and sb which are situated only 1 areolar diameter apart (Figure 8C,D), by the gaping chelal fingers of the male due to the excavated margin of the movable chelal finger (Figure 8C), and the presence of 7 (occasionally 6) setae on the cheliceral hand (Figure 9A).

Description (adults). Setae: generally very long, straight or only slightly curved, and with finely dentate tips in the distal quarter.

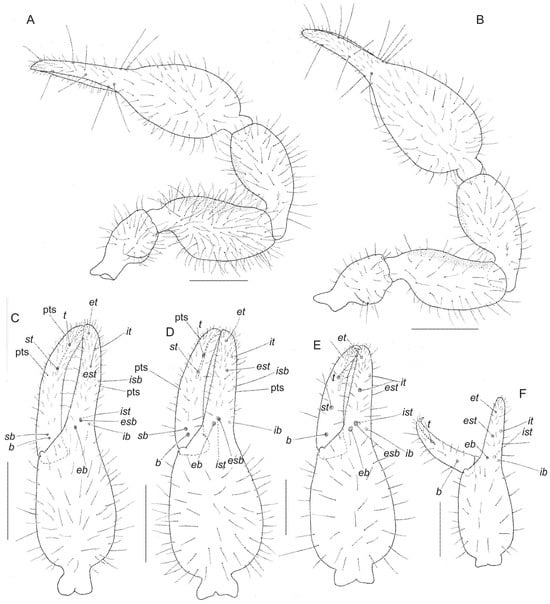

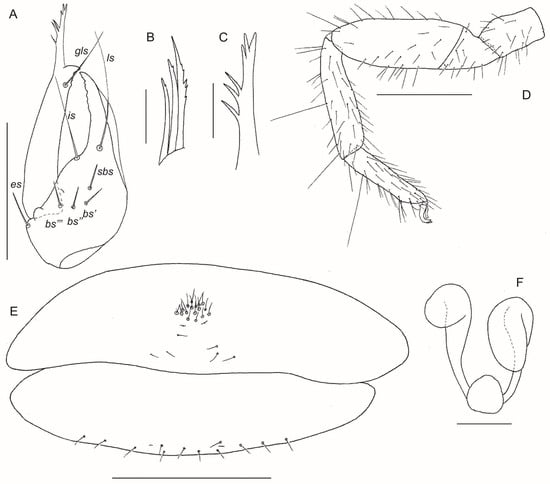

Chelicera (Figure 9A): hand with 7 (occasionally 6) setae; movable finger with 1 long subdistal seta; with 2 dorsal lyrifissures and 1 ventral lyrifissure; rallum of 3 blades, all blades serrate (Figure 9B); galea slender with several rami (Figure 9C); lamina exterior present (Figure 9A).

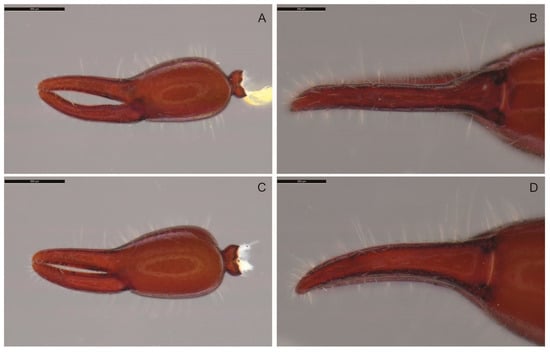

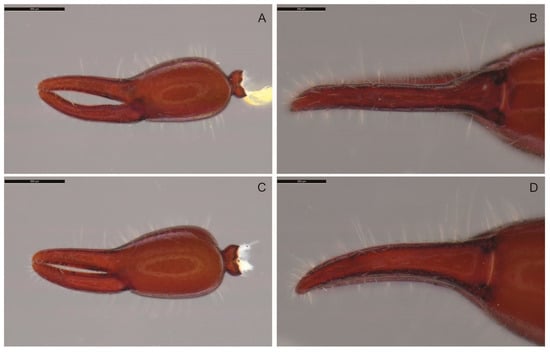

Pedipalp (Figure 8A,B): robust; fixed chelal finger with 8 trichobothria, movable chelal finger with 4 trichobothria (Figure 8C,D): trichobothria eb and esb sub-basal; est much closer to et than to esb; et distal; ib and ist sub-basal; isb submedial, situated basal to est; and it situated subdistally, midway between et and est; b and sb sub-basal and situated only 1 areolar diameter apart; st situated much closer to t than to sb. Chelal hand foramen without flange on retrolateral margin; chelal hand without sense-spots. Chelal fingers of male noticeably gaping (Figure 8C). Fixed finger with 1 dorsal pseudotactile seta basal to isb, movable finger with 2 pseudotactile setae, one basal to st and the other near tip of finger (Figure 8C,D). Venom apparatus only present in movable chelal finger, venom duct long terminating in slightly inflated nodus ramosus near st (Figure 8C,D); marginal chelal teeth juxtadentate, with accessory chelal teeth on retrolateral and prolateral margins.

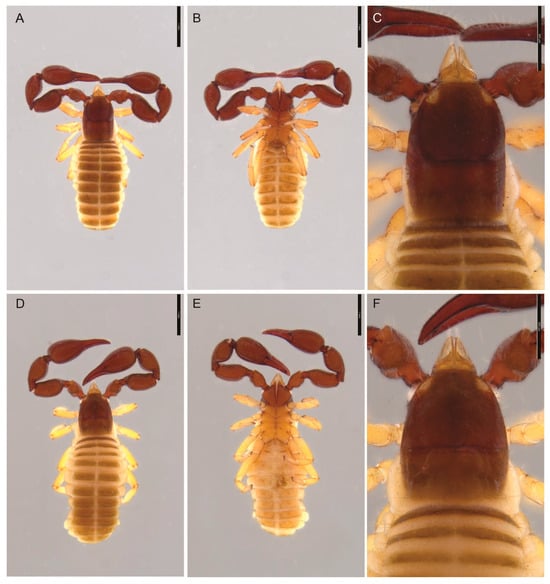

Carapace (Figure 6C,F): mostly smooth, with finely granulate antero-lateral regions; with 1 pair of eye-spots; with broad, distinct anterior furrow, but posterior furrow absent; posterior margin of carapace straight.

Figure 6.

Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov.: (A–C) holotype male (MNHN): (A) dorsal; (B) ventral; (C) cephalothorax; (D–F) paratype female (MNHN): (D) dorsal; (E) ventral; (F) cephalothorax. Scale lines = 1 mm.

Coxal region: manducatory process with small sub-oral seta on medial edge; median maxillary lyrifissure rounded and situated submedially; posterior maxillary lyrifissure rounded.

Legs (Figure 9C): junction between femora and patellae I and II strongly oblique; suture line between femora and patellae III and IV strongly oblique; femora III and IV much smaller than patellae; patella III and IV with 1 subdistal ‘pseudotactile’ seta; tibia with 1 medial and 1 subdistal ‘pseudotactile’ seta; tarsi III and IV with long tactile seta; all tarsi with slit sensillum on raised mound; legs with sub-terminal tarsal setae arcuate and acute; arolium undivided, slightly shorter than claws; claws slender and simple, without ventral process.

Abdomen: most tergites and sternites with medial suture line (Figure 6A,B,D,E). Sternite II of ♀ with small, concentrated patch of setae, plus a row of setae on posterior margin (Figure 9E). Spiracles simple, with spiracular helix. Pleural membrane longitudinally striate, without setae.

Genitalia: male with typical chernetid morphology; female with paired spermathecae with long ducts terminating in large ovoid receptacula (Figure 9F).

Description (tritonymph). Pedipalp: fixed finger with 7 trichobothria, est situated slightly closer to et than esb; movable finger with 3 trichobothria; isb and sb absent; st situated midway between b and t (Figure 8E).

Description (deutonymph). Pedipalp: fixed finger with 6 trichobothria, est situated midway between eb and et; movable finger with 2 trichobothria; esb, isb, sb, and st absent (Figure 8F).

Etymology. The genus name is derived from the island Motu Motiro Hiva, which is combined with the genus name Chernes (labourer, Greek). It is masculine in gender.

Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov.

ZooBank Registration:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:6F67729D-9116-4550-9292-EBAF3C3056C5

Material examined. Holotype male. CHILE: Valparaíso Province: Motu Motiro Hiva (Salas y Gómez Island), 26.4721° S, 105.3625° W, 2 September 2014, M. Portflitt-Toro (MNHN).

Paratypes. CHILE: Valparaíso Province: 3 males, 1 females, 1 tritonymph, same data (MNHN); 2 males (SSUC 8085, 8086), 1 female (SSUC 8087), same data; 1 female, same data (SCBUCN-5559); 1 male, 1 female, same data (WAM T163734, T163735); 2 males, 1 tritonymph, 1 deutonymph, same data except 2 September 2015 (SCBUCN-5560); 1 male, same data (WAM T163736).

Diagnosis. As for genus.

Description (adult). Colour (Figure 6A–F): carapace, pedipalps deep red-brown; tergites yellow-brown; and legs pale yellow-brown.

Chelicera (Figure 9A): with 7 (occasionally 6) setae on hand and 1 subdistal seta on movable finger; setae ls and is long and acuminate, all others lightly dentate; galea long and slender with 3 distal rami and 3 further rami along shaft (Figure 9C); rallum of 3 blades, anterior blade with several serrations, medial and posterior blades with 1 serration (Figure 9B); serrula exterior with 19 (♂), 22 (♀) blades.

Pedipalp (Figure 8A,B): dorsal surface of trochanter and prolateral surfaces of femur and patella granulate, all other pedipalpal surfaces smooth; patella with 3 large and 2 small sub-basal lyrifissures; all segments robust, trochanter 1.59–1.97 (♂), 1.85–2.04 (♀), femur 2.11–2.40 (♂), 2.28–2.57 (♀), patella 1.90–2.18 (♂), 2.08–2.17 (♀), chela (with pedicel) 3.06–3.43 (♂), 2.96–2.99 (♀), chela (without pedicel) 2.83–3.22 (♂), 2.72–2.79 (♀), hand (without pedicel) 1.33–1.48 (♂), 1.36–1.46 (♀) × longer than broad, movable finger 1.02–1.21 (♂), 0.94–1.28 (♀) × longer than hand (without pedicel). Fixed chelal finger with 8 trichobothria, movable chelal finger with 4 trichobothria (Figure 8C,D): eb and esb situated basally, est situated much closer to et than to esb, ib and ist situated sub-basally, isb situated submedially; it situated subdistally, midway between est and et; et situated distally; st and t situated subdistally, st situated much closer to t than sb, and sb situated much closer to b than to st. Fixed finger with 1 dorsal submedial pseudotactile seta, movable finger with 2 pseudotactile setae, one basal to st, and the other near tip of finger (Figure 8C,D). Venom apparatus only present in movable chelal finger, venom duct long, terminating in nodus ramosus near st (Figure 8C,D). Chelal hand ovoid; foramen without flange on retrolateral margin. Chelal fingers of male strongly gaping (Figure 8C), of female slightly gaping (Figure 8D); teeth slightly retrorse, basal teeth more rounded; fixed finger with 49 (♂), 41 (♀) teeth, plus 4 (♂), 9 (♀) retrolateral accessory teeth and 6 (♂), 4 (♀) prolateral accessory teeth, all located in distal half; movable finger with 44 (♂), 44 (♀) teeth, plus 7 (♂), 8 (♀) retrolateral accessory teeth and 6 (♂), 5 (♀) prolateral accessory teeth, all located in distal half; chelal hand and fingers without sense-spots.

Carapace (Figure 6C,F): granulate laterally, but remainder smooth; 1.22–1.40 (♂), 1.19–1.31 (♀) × longer than broad; with 1 pair of distinct eye-spots; with 98 (♂), 101 (♀), including 6 (♂), 6 (♀) setae near anterior margin and 12 (♂), 15 (♀) setae near posterior margin; with distinct median furrow, posterior furrow absent.

Coxal region: maxillae and coxae smooth; manducatory process rounded, with 4 apical acuminate setae, with 1 small sub-oral seta, and 49 (♂), 51 (♀) additional setae. Chaetotaxy of coxae I–IV: ♂, 24: 21: 20: 42; ♀: 28: 24: 23: 59.

Legs (Figure 9D): femur + patella of leg IV 3.55 (♂), 3.45 (♀) × longer than deep; patella IV with distal tactile seta; tibia IV with 2 tactile setae situated medially and distally; tarsus IV with long tactile seta located in basal third, TS ratio = 0.30 (♂), 0.35 (♀).

Abdomen: tergites II–XI and sternites IV–XI with medial suture line (Figure 6A,B,D,E). Tergal chaetotaxy: ♂, 23: 21: 19: 27: 28: 29: 25: 27: 35: 28: 18: 2; ♀, 22: 20: 19: 22 32: 30: 34: 30: 31: 28: 20: 2; setae lightly dentate. Sternal chaetotaxy: ♂, 40: (3) 12 [4 + 4] (3): (1) 12 (1): 27: 27: 27: 30: 26: 27 (including 6 tactile setae): 14: 2; ♀, 24: (2) 12 (2): (2) 10 (2): 22: 27: 28: 27: 30: 30 (including 8 tactile setae): 12: 2. Sternite II of ♀ with small, concentrated patch of 18 short setae, plus 6 setae closer to posterior margin (Figure 9E). Pleural membrane without setae.

Genitalia: male with typical chernetid morphology; female with 1 pair of spermathecae with long ducts terminating in large ovoid receptacula (Figure 9F).

Dimensions (mm): holotype male (followed by 9 other paratypes in parentheses): body length 3.25 (2.54–3.84). Pedipalps: trochanter 0.625/0.325 (0.570–0.635/0.300–0.390), femur 1.020/0.460 (0.900–1.105/0.410–0.465), patella 0.890/0.425 (0.790–0.930/0.380–0.475), chela (with pedicel) 1.730/0.505 (1.580–1.730/0.490–0.565), chela (without pedicel) 1.625 (1.450–1.600), hand (without pedicel) length 0.740 (0.685–0.780), movable finger length 0.895 (0.750–0.865). Carapace 1.115/0.795 (0.955–1.170/0.750–0.835); eye diameter 0.105. Leg IV: femur + patella 0.905/0.255, tibia 0.705/0.160, tarsus 0.525/0.125, TS = 0.160.

Female: paratype female (followed by 3 other paratypes in parentheses): body length 4.21 (3.89–4.35). Pedipalps: trochanter 0.610/0.320 (0.570–0.575/0.280–0.310), femur 0.975/0.420 (0.915–0.950/0.370–0.400), patella 0.910/0.435 (0.835–0.865/0.385–0.415), chela (with pedicel) 1.685/0.570 (1.570–1.675/0.530–0.560), chela (without pedicel) 1.590 (1.455–1.550), hand (without pedicel) length 0.815 (0.760–0.775), movable finger length 0.770 (0.690–0.800). Carapace 1.110/0.850 (0.960–1.025/0.810–0.815); eye diameter 0.145. Leg IV: femur + patella 0.965/0.280, tibia 0.710/0.155, tarsus 0.530/0.125, TS = 0.185.

Description (tritonymph). Colour: pedipalps red-brown, carapace pale brown.

Chelicera: with 5 setae on hand and 1 subdistal seta on movable finger; seta bs, sbs and es dentate, ls and is long and acuminate; galea slender with 2 distal and 2 subdistal rami; rallum with 3 blades.

Pedipalp: trochanter 1.98, femur 2.35, patella 2.02, chela (with pedicel) 3.30, chela (without pedicel) length 3.07, hand (without pedicel) 1.60 × longer than broad, movable finger 0.89 × longer than hand (without pedicel); chelal hand about as deeper as broad. Fixed chelal finger with 7 trichobothria, movable chelal finger with 3 trichobothria (Figure 8E): eb, esb, ib and ist situated sub-basally, est situated midway between esb to et, et situated closer to the end of the finger than to it, t situated subdistally, and st situated slightly closer to b than to t. Venom apparatus only present in movable chelal finger, venom duct long, terminating in nodus ramosus basal to t. Retrolateral margin of chelal hand foramen without flange. Fixed chelal finger with 36 teeth, with 2 prolateral accessory teeth and no retrolateral accessory teeth; movable finger with 33 teeth, with 2 prolateral accessory teeth and 1 retrolateral accessory tooth.

Carapace: smooth; 1.24 × longer than broad; eye-spots not visible; with 38 setae, including 4 near anterior margin and 11 near posterior margin; with 1 medial furrow.

Coxal region: chaetotaxy of coxae I–IV: 10: 10: 9: 12.

Legs: much as in adults except femur + patella 3.53 × longer than deep; TS ratio = 0.13.

Abdomen: tergal chaetotaxy: 14: 14: 16: 20: 20: 21: 19: 20: 21: 19: 12: 2. Sternal chaetotaxy: 2: (2) 6 (2): (1) 6 (1): 16: 18: 18: 19: 20: 20: 14: 2. Pleural membrane without setae.

Dimensions (mm): body length 3.76. Pedipalps: trochanter 0.395/0.200, femur 0.600/0.255, patella 0.555/0.275, chela (with pedicel) 1.105/0.335, chela (without pedicel) length 1.030, hand (without pedicel) length 0.535, movable finger length 0.475. Carapace 0.680/0.550. Leg IV: femur + patella 0.600/0.170, tibia 0.435/0.115, tarsus 0.340/0.095, TS = 0.045.

Description (deutonymph). Colour: pedipalps red-brown, carapace pale brown.

Chelicera: with 5 setae on hand and 1 subdistal seta on movable finger; seta bs, sbs and es sparsely dentate, ls and is long and acuminate; galea slender with 2 distal and 2 subdistal rami; rallum with 3 blades.

Pedipalp: trochanter 1.89, femur 2.39, patella 2.00, chela (with pedicel) 3.00, chela (without pedicel) 2.836, hand (without pedicel) 1.68 × longer than broad, movable finger 0.80 × longer than hand (without pedicel); chelal hand about as deep as broad. Fixed chelal finger with 6 trichobothria, movable chelal finger with 2 trichobothria (Figure 8F): eb, ib and ist situated sub-basally, est situated midway eb and et, et situated closer to the end of the finger than to it, it situated closer to est than et, t situated subdistally, and b situated sub-basally. Venom apparatus only present in movable chelal finger, venom duct long, terminating in nodus ramosus slightly basal to t. Retrolateral margin of chelal hand foramen without flange. Fixed chelal finger with 26 teeth, with 2 prolateral accessory teeth and no retrolateral accessory teeth; movable finger with 28 teeth, with 1 prolateral accessory tooth and no retrolateral accessory teeth.

Carapace: smooth; 1.20 × longer than broad; eye-spots not visible; with 26 setae, including 4 near anterior margin and 10 near posterior margin; without furrows.

Coxal region: chaetotaxy of coxae I–IV: 4: 7: 7: 9.

Legs: much as in adults except femur + patella 3.36 × longer than deep; TS ratio = 0.24.

Abdomen: tergal chaetotaxy: 10: 10: 10: 11: 13: 14: 15: 12: 16: 14: 10: 2. Sternal chaetotaxy: 0: (1) 5 (1): (1) 6 (1): 10: 11: 12: 12: 14: 12: 10 (including 2 tactile setae): 2. Pleural membrane without setae.

Dimensions (mm): body length 2.53. Pedipalps: trochanter 0.265/0.140, femur 0.405/0.175, patella 0.370/0.185, chela (with pedicel) 0.705/0.235, chela (without pedicel) length 0.665, hand (without pedicel) length 0.395, movable finger length 0.315. Carapace 0.610/0.510. Leg IV: femur + patella 0.420/0.125, tibia 0.285/0.090, tarsus 0.250/0.070, TS = 0.060.

Etymology. The species epithet refers to the gaping chelal fingers of the male (spatium, Latin, room, distance; digitus, Latin, finger).

Remarks. The specimens were found within mummified carcasses of seabirds (Figure 2E).

Figure 7.

Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov., left chelae: (A,B), holotype male (MNHN): (A) retrolateral; (B) ventral; (C,D) paratype female (MNHN): (C) retrolateral; (D) ventral. Scale lines = 0.5 mm.

Figure 8.

Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov., holotype male, and paratype female and nymphs (MNHN): (A) right pedipalp, dorsal, male; (B) right pedipalp, dorsal, female; (C) left chela, retrolateral, male; (D) left chela, retrolateral, female; (E) left chela, retrolateral, tritonymph; (F) left chela, retrolateral, deutonymph. Scale lines = 0.50 mm (A–D), 0.25 mm (E,F).

Figure 9.

Motuchernes spatiodigitus, sp. nov.: (A–D) holotype male (MNHN): (A) left chelicera, dorsal; (B) left rallum; (C) galea, dorsal; (D) left leg IV; (E,F) paratype female (MNHN): (E) genital sternites, ventral; (F) spermathecae, ventral. Scale lines = 0.50 mm (D), 0.25 mm (A,E), 0.05 mm (B,C,F).

4. Discussion

Concerning the two pseudoscorpion taxa likely endemic to Motu Motiro Hiva, their regional distributions and dispersal potential remain largely unknown. Within the Garypus genus, 12 species are known from the New World [8] with the majority occurring in littoral habitats [23,43,44,45]. Their occurrence along the coast suggests that rafting on flotsam and/or phoresy on pelagic birds may have facilitated their dispersal, possibly from the American continent. The Galápagos islands is the closest territory known to contain Garypus species. As for the new genus Motuchernes, it was recovered within a clade that includes Lustrochernes. This genus is broadly distributed across North and South America [8], with additional species known from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, French Polynesia, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, and Tonga (Harvey, unpublished data). In this case, given the current sampling of the closely related species, it turns out to be more difficult to assess a potential origin.

These patterns suggest that long-distance mechanisms, such as rafting or phoresy, may play a key role in their colonisation on this remote oceanic island. Driven by oscillating oceanic currents associated with the South Pacific Gyre, rafting vegetation could eventually reach the shores of MMH from the South American coast and Rapa Nui [13]. Additionally, 12 seabird species nests on MMH, including terns, boobies, frigatebirds, tropicbirds, and petrels (Figure 2C) [45,46]. These nesting sites provide suitable habitats for terrestrial invertebrates such as pseudoscorpions. Similar associations have been documented on Brazilian oceanic islands, where Masked boobies (Sula dactylatra Lesson, 1831) and terns of the genus Anous acted as transport vectors for pseudoscorpions [47]. Therefore, rafting via floating vegetation and phoretic transport on seabirds represent plausible dispersal pathways for the colonisation of this extremely isolated island (Figure 2B–D).

There is a limited number of studies assessing the origin of the flora and fauna from this islet. The endemic spider Ariadna motumotirohiva presents genital morphological characteristics more similar to species from the same genus present in Hawai’i and the Marquesas, instead of those from the New World [10]. Currently, with molecular data not available yet, this has been interpreted as a biogeographic affinity with other Polynesian islands. Given the data reported here, Motuchernes could also have their origin in the Polynesian region, but this still needs to be phylogenetically tested.

Regarding the flora of the island, it is limited to four species, corresponding to one fern and three flowering plants [48]. They all correspond to coastal species with widespread distributions suggesting affinities with other Pacific islands such as the Juan Fernández Archipelago, the Pitcairn, the Cook, the Austral, the Gambier, the Society and the Marquesas Islands (French Polynesia), the Galápagos, and the Hawaiian Islands. The remoteness makes MMH subject to colonisation by only highly dispersive plants, which in principle would be expected to reduce the probability of the development of local endemics. However, this idea is challenged by one of the reported species from the genus Parietaria, which due to particular morphological characteristics, has been proposed as potentially new to science [48]. Therefore, despite having low diversity of highly dispersive plant species, it appears that the supreme isolation of MMH has facilitated the divergence of one of those species. The same situation could be expected of other highly dispersed organisms such as pseudoscorpions.

The discovery of a new pseudoscorpion fauna underscores the need for expanded geographic sampling and targeted microhabitat surveys to clarify phylogenetic relationships among the different genera, including the placement of Motuchernes relative to Lustrochernes and other potentially allied groups. As the closest island, Rapa Nui is particularly important to survey, because sister populations could be found, as is the case for the terrestrial isopod Hawaiioscia rapui [12]. The higher elevation of Rapa Nui (511 m), compared with 30 m for MMH, may have provided a refugium for pseudoscorpions and other terrestrial invertebrates during inclement weather when high seas may have completely inundated MMH. Additionally, Rapa Nui may have served as a source habitat for MMH when sea levels were higher than today [49]. However, to date, no closely related pseudoscorpions have been found on Rapa Nui. Alternatively, MMH could have served as a peripheral island refugium for species that became extinct on the main island (i.e., Rapa Nui), as occurred with several plant species on Hawaiʻi Island [50] and the Lord Howe Island stick insect in Australia [51].

In the current context of climate change, it is more urgent than ever to explore the biodiversity present on remote and understudied islands. Many of these land masses are highly threatened and, at the same time, host unique species, which are key to our understanding of how particular groups evolve and more general mechanisms of diversification. At the same time, biodiversity discovery is the foundation for evidence-based decisions in conservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120852/s1, File S1: Phylogenetic analyses and output, Table S1: Recorded distributions of described pseudoscorpion species from the south-eastern Pacific Ocean, Table S2: Specimens used in the molecular analysis of the genus Garypus, Table S3: Specimens used in the molecular analysis of the genus Motuchernes. References [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.H., M.P.-T., and D.D.C.; methodology, M.S.H.; validation, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., C.R.-O., and D.D.C.; formal Analysis, M.S.H.; investigation, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., C.R.-O., and D.D.C.; resources, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., and D.D.C.; data curation, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., and D.D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., C.R.-O., and D.D.C.; writing—review and editing, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., C.R.-O., and D.D.C.; visualisation, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., C.R.-O., and D.D.C.; supervision, M.S.H., M.P.-T., J.J.W., and D.D.C.; project administration, M.S.H., M.P.-T., and D.D.C.; funding acquisition, M.P.-T. and D.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

DDC was supported by the Fondecyt Iniciación Project No. 11250485 funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile. MPT was supported by the Center of Ecology and Sustainable Management for Oceanic Islands (ESMOI), ANILLO ANID ATE 220044 BiodUCCT, and the Sala de Colecciones Biológicas of the Universidad Católica del Norte (SCBUCN).

Data Availability Statement

The sequences used in this paper are lodged in the NCBI under the accession numbers given in Tables S2 and S3.

Acknowledgments

M.P.-T. and J.J.W. thanks the support of the Chilean Navy and the Rapa Nui CONAF Park Rangers for the work on Motu Motiro Hiva. D.D.C. acknowledges financial support by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile. We are very grateful to the staff of the Western Australian Museum’s Genetic Resources Unit for generating some of the sequence data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMH | Motu Motiro Hiva |

| MNHN | Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Santiago, Chile |

| SCBUCN | Sala de Colecciones Biológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile |

| SSUC | Colección de Flora y Fauna Profesor Patricio Sánchez Reyes, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile |

| WAM | Western Australian Museum, Perth |

| b | Basal seta |

| sb | Sub-basal seta |

| t | Terminal seta |

| st | Sub-terminal seta |

| it | Interior terminal seta |

| ist | Interior sub-terminal seta |

| ib | Interior basal seta |

| isb | Interior sub-basal seta |

| et | Exterior terminal seta |

| est | Exterior sub-terminal seta |

| eb | Exterior basal seta |

| esb | Exterior sub-basal seta |

| gls | Galeal seta |

| ls | Laminal seta |

| is | Interior seta |

| sbs | Sub-basal seta |

| es | Exterior seta |

| bs | Basal setae (chelicera) |

| pts | Pseudotactile setae |

References

- Harvey, M.S. From Siam to Rapa Nui—The identity and distribution of Geogarypus longidigitatus (Rainbow) (Pseudoscorpiones: Geogarypidae). Bull. Br. Arachnol. Soc. 2000, 11, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, J.J.; Howarth, F.G.; Cotoras, D.D.; Rothmann, S.; Ríos, S.; Valdez, C.; Hucke, P.L.; Villagra, C.; Flores-Prado, L. The terrestrial arthropods of Rapa Nui: A fauna dominated by non-native species. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 57, e03280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M. Pseudoscorpione von den Juan-Fernandez-Inseln (Arachnida Pseudoscorpionida). Rev. Chil. De Entomol. 1955, 4, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, M. Los Insectos de las Islas Juan Fernandez. 37. Die Pseudoscorpioniden-Fauna der Juan-Fernandez-Inseln (Arachnida Pseudoscorpionida). Rev. Chil. De Entomol. 1957, 5, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Mahnert, V. New records of pseudoscorpions from the Juan Fernandez Islands (Chile), with the description of a new genus and three new species of Chernetidae (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones). Rev. Suisse Zool. 2011, 118, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, M. Die Pseudoscorpioniden-Fauna Chiles. Ann. Des Naturhistorischen Mus. Wien 1964, 67, 307–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cotoras, D.D.; Elgueta, M.; Vilches, M.J.; Hagen, E.; Pott, M. Terrestrial invertebrates surviving San Ambrosio island’s ecological catastrophe reinforce biogeographic affinities between the Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands. J. Nat. Hist. 2021, 55, 1781–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Pseudoscorpiones Catalog. Natural History Museum, Bern. 2024. Available online: https://wac.nmbe.ch/order/pseudoscorpiones/3 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Gaymer, C.F.; Wagner, D.; Alvarez-Varas, R.; Boteler, B.; Bravo, L.; Brooks, C.M.; Chavez-Molina, V.; Currie, D.; Delgado, J.; Dewitte, B.; et al. Research advances and conservation needs for the protection of the Salas y Gómez and Nazca ridges: A natural and cultural heritage hotspot in the Southeastern Pacific Ocean. Mar. Policy 2025, 171, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroti, A.M.; Cotoras, D.D.; Lazo, P.; Brescovit, A.D. First endemic arachnid from Isla Sala y Gómez (Motu Motiro Hiva), Chile: A new species of tube-dwelling spider (Araneae: Segestriidae). Eur. J. Taxon. 2020, 722, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershauer, S.; Y-Pakarati, S.; Wynne, J.J. Notes on the arthropod fauna of Salas y Gómez Island, Chile. Rev. Chil. De Hist. Nat. 2020, 93, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiti, S.; Wynne, J.J. The terrestrial Isopoda (Crustacea, Oniscidea) of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), with descriptions of two new species. ZooKeys 2015, 515, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, J.J.; Taiti, S.; Pakarati, S.; Castillo-Trujillo, A.C. Range extension of the endemic terrestrial isopod, Hawaiioscia rapui, reveals the dispersal potential for the genus across the South Pacific. Bish. Mus. Occas. Pap. 2022, 147, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, A.; Gray, A. Tiny habitats of tiny species: The importance of micro-refugia for threatened island-endemic arthropods. Oryx 2025, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, F. Checklist of the Collembola, Last Updated on 12 October 2024. 2025. Available online: http://www.collembola.org/taxa/collembo.htm (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Greenslade, P.; Ireson, J.E. Collembola of the southern Australian culture steppe and urban environments: A review of their pest status and key to identification. Aust. J. Entomol. 1986, 25, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, E.C.A.; Zeppelini, D. First survey of Collembola (Hexapoda: Entognatha) fauna in soil of Archipelago Fernando de Noronha, Brazil. Fla. Entomol. 2015, 98, 368–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipola, N.G. An updated catalogue of the Collembola (Hexapoda) from Colombia and a perspective for unexplored richness. Zootaxa 2023, 5293, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgueta, M.; Lazo, P.H. Cryptamorpha desjardinsi (Guérin-Méneville, 1844) primer registro de un insecto (Coleoptera: Silvabidae) para la Isla Sala y Gómez, Chile. Acta Entomológica Chil. 2013, 33, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, S.L.; Peña, G.L.E. Los insectos de la isla de Pascua (Resultados de una prospección entomológica). Rev. Chil. De Entomol. 1973, 7, 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- [GBIF] Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Lynchia americana (Leach, 1817) Checklist Dataset. 2025. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/uk/species/5088622 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Rodrigo, C.; Díaz, J.; González-Fernández, A. Origin of the Easter Submarine Alignment: Morphology and structural lineaments. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 42, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S.; Hillyer, M.J.; Carvajal, J.I.; Huey, J.A. Supralittoral pseudoscorpions of the genus Garypus (Pseudoscorpiones: Garypidae) from the Indo-West Pacific region, with a review of the subfamily classification of Garypidae. Invertebr. Syst. 2020, 34, 34–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebec, D.; Harms, D.; Kučinić, M.; Harvey, M.S. Integrative taxonomy of the pseudoscorpion family Chernetidae (Pseudoscorpiones: Cheliferoidea): Evidence for new range-restricted species in the Dinaric Karst. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 200, 644–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J.C. The Arachnid Order Chelonethida; Stanford University Publications, Biological Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1931; Volume 7, pp. 1–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S. The phylogeny and classification of the Pseudoscorpionida (Chelicerata: Arachnida). Invertebr. Taxon. 1992, 6, 1373–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, M.L.I. A new and endangered species of the pseudoscorpion genus Lagynochthonius from a cave in Vietnam, with notes on chelal morphology and the composition of the Tyrannochthoniini (Arachnida, Chelonethi, Chthoniidae). Zootaxa 2007, 1627, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S.; Ratnaweera, P.B.; Udagama, P.V.; Wijesinghe, M.R. A new species of the pseudoscorpion genus Megachernes (Pseudoscorpiones: Chernetidae) associated with a threatened Sri Lankan rainforest rodent, with a review of host associations of Megachernes. J. Nat. Hist. 2012, 46, 2519–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S.; Lopes, P.C.; Goldsmith, G.R.; Halajian, A.; Hillyer, M.J.; Huey, J.A. A novel symbiotic relationship between sociable weaver birds (Philetairus socius) and a new cheliferid pseudoscorpion (Pseudoscorpiones: Cheliferidae) in southern Africa. Invertebr. Syst. 2015, 29, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S.; Abrams, K.M.; Beavis, A.S.; Hillyer, M.J.; Huey, J.A. Pseudoscorpions of the family Feaellidae (Pseudoscorpiones: Feaelloidea) from the Pilbara region of Western Australia show extreme short-range endemism. Invertebr. Syst. 2016, 30, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S.; Huey, J.A.; Hillyer, M.J.; McIntyre, E.; Giribet, G. The first troglobitic species of Gymnobisiidae (Pseudoscorpiones, Neobisioidea), from Table Mountain (Western Cape Province, South Africa) and its phylogenetic position. Invertebr. Syst. 2016, 30, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murienne, J.; Harvey, M.S.; Giribet, G. First molecular phylogeny of the major clades of Pseudoscorpiones (Arthropoda: Chelicerata). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2008, 49, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.-I.; Mityata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software Version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.-T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R.C. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giribet, G.; Carranza, S.; Baguñà, J.; Riutort, M.; Ribera, C. First molecular evidence for the existence of a Tardigrada + Arthropoda clade. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996, 13, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, M.F.; Carpenter, J.M.; Wheeler, Q.D.; Wheeler, W.C. The Strepsiptera problem: Phylogeny of the holometabolous insect orders inferred from 18S and 28S ribosomal DNA sequences and morphology. Syst. Biol. 1997, 46, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Huang, J.X.; Liu, H.H.; Chang, C.-H. Two new pseudoscorpion species of the coastal genus Garypus, L. Koch, 1873 (Garypidae) and an updated checklist of the Pseudoscorpiones of Taiwan. Zool. Stud. 2022, 61, e24. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, E. Les Ordres des Chernetes, Scorpiones et Opiliones. In Les Arachnides de France; Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret: Paris, France, 1879; Volume 7, pp. 1–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mahnert, V. Pseudoscorpions (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpiones) from the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador). Rev. Suisse De Zool. 2014, 121, 135–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar-Hummelinck, P. Pseudoscorpions of the genera Garypus, Pseudochthonius, Tyrannochthonius and Pachychitra. Stud. Fauna Curaçao Other Caribb. Isl. 1948, 3, 29–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.F. The maritime pseudoscorpions of Baja California, México (Arachnida: Pseudoscorpionida). Occas. Pap. Calif. Acad. Sci. 1979, 131, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.A.; Schlatter, R.P.; Hucke-Gaete, R. Seabirds of Easter Island, Salas y Gómez Island and Desventuradas Islands, southeastern Pacific Ocean. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 42, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Jorquera, G.; Thiel, M.; Portflitt-Toro, M.; Dewitte, B. Marine protected areas invaded by floating anthropogenic litter: An example from the South Pacific. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Neto, M.A.; de Lima, E.C.A.; Lopes, B.C.H.; Gallão, J.E.; Stievano, L.C.; Machado, C.C.C.; Bichuette, M.E.; Zeppelini, D. Pseudoscorpiones (Arachnida) of the Brazilian oceanic islands. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 52, e02971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.-Y.; Cotoras, D.D.; Lazo Hucke, P.; Yancovic Pakarati, S. The peculiar flora of Motu Motiro Hiva (Salas y Gómez, Chile) and its similarities with other small remote uninhabited Eastern Pacific islands. Atoll Res. Bull. 2023, 632, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, R. Sea Level Change During the Last 5 Million Years. 2016. Available online: https://serc.carleton.edu/integrate/teaching_materials/coastlines/student_materials/901 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Wood, K.R. Possible extinctions, rediscoveries, and new plant records within the Hawaiian Islands. Bish. Mus. Occas. Pap. 2012, 113, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Priddel, D.; Carlile, N.; Humphrey, M.; Fellenberg, S.; Hiscox, D. Rediscovery of the ‘extinct’ Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis (Montrouzier)) (Phasmatodea) and recommendations for its conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.S. Redescriptions of Geogarypus bucculentus Beier and G. pustulatus Beier (Geogarypidae: Pseudoscorpionida). Bull. Br. Arachnol. Soc. 1987, 7, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, T.; Lehtinen, P. The arachnids of Henderson Island, South Pacific. Newsl. Br. Arachnol. Soc. 1995, 72, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, T.; Lehtinen, P. Biodiversity and origin of the non-flying terrestrial arthropods of Henderson Island. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1995, 56, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J.C. New and little-known false-scorpions from the Pacific and elsewhere (Arachnida—Chelonethida). Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1938, 2, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchmore, W.B. Redefinition of the genus Chelanops Gervais (Pseudoscorpionida: Chernetidae). Pan-Pac. Entomol. 1999, 75, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- With, C.J. On some new species of the Cheliferidae, Hans., and Garypidae, Hans., in the British Museum. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. Zool. 1907, 30, 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J.C. Tahitian and other records of Haplochernes funafutensis (with) (Arachnida: Chelonethida). Bull. Bernice P. Bish. Mus. 1939, 142, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, M. Die Pseudoscorpionidenfauna der landfernen Inseln. Zool. Jahrbücher Abt. Syst. Okol. Geogr. Der Tiere 1940, 74, 161–192. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).