Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata and Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica in Mediterranean Region Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Occurrence Points for the Distribution of Species

2.2. Obtainment and Pretreatment of Environmental Data Layers

2.3. MaxEnt Calibration and Modeling Methodology

2.4. Performance Assessment of Species Distribution Models

2.5. Division of Potential Distribution Areas and Evaluation of Climate Change Impact

3. Results

3.1. Modeling Performance

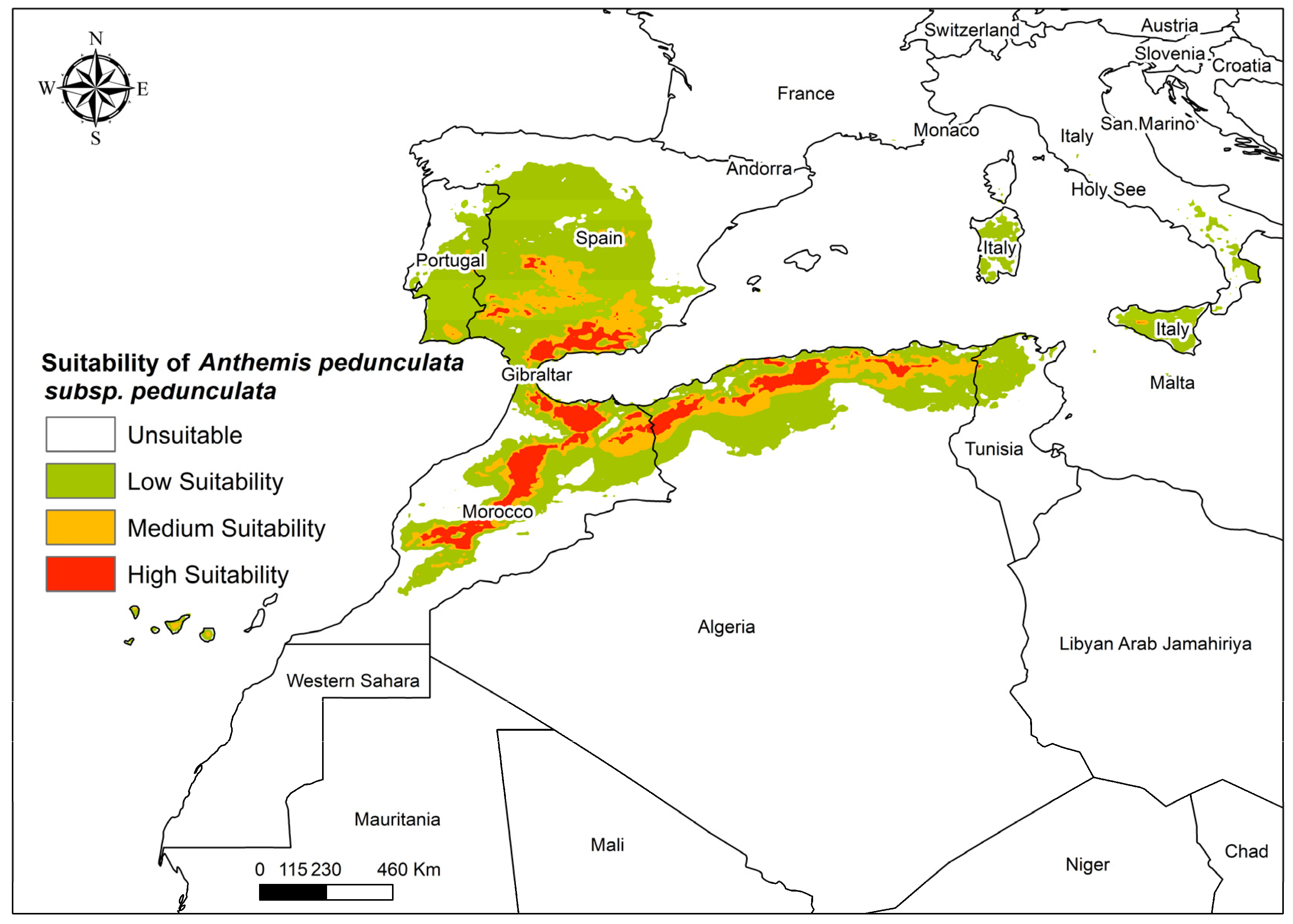

3.2. Current Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata

3.3. Future Global Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica

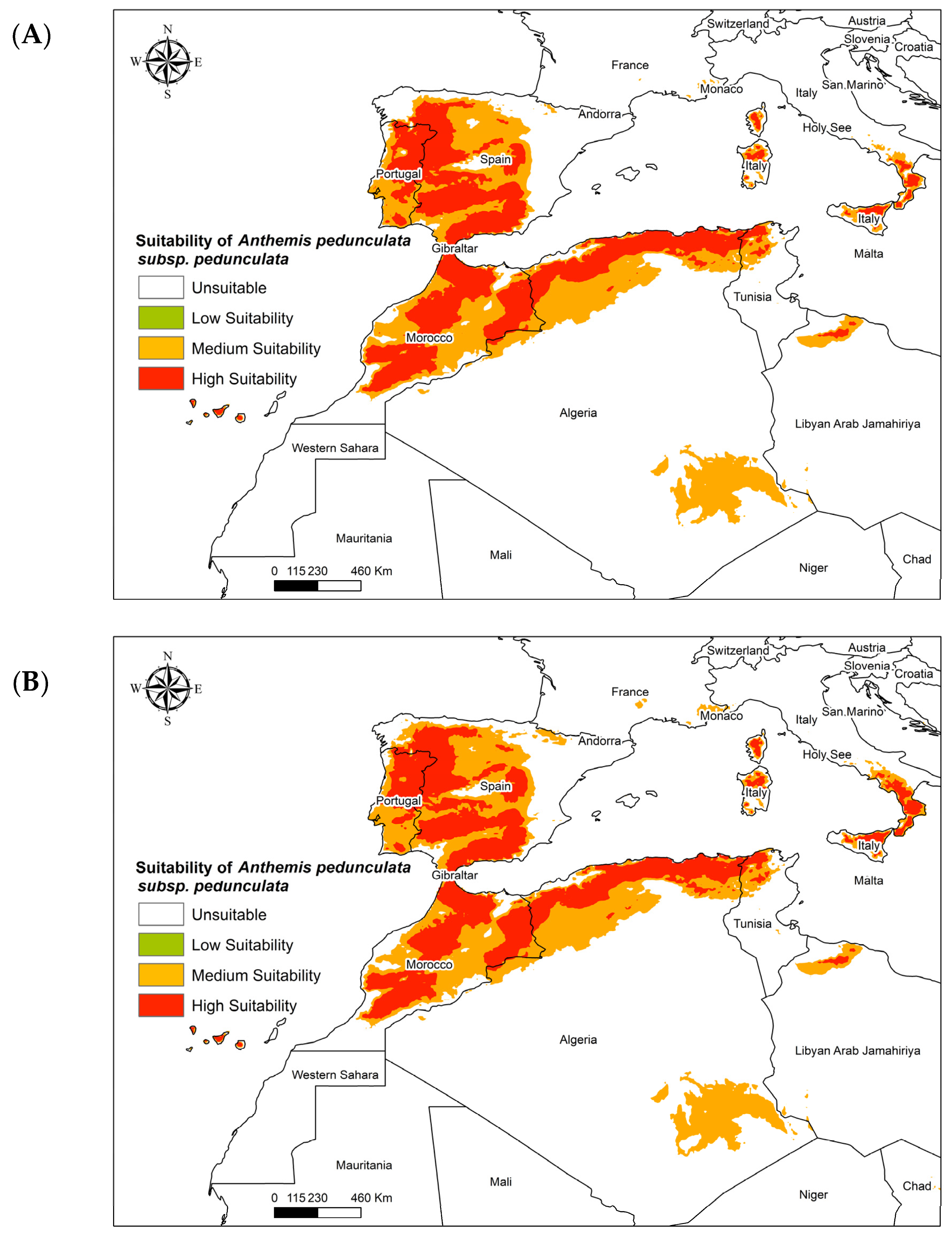

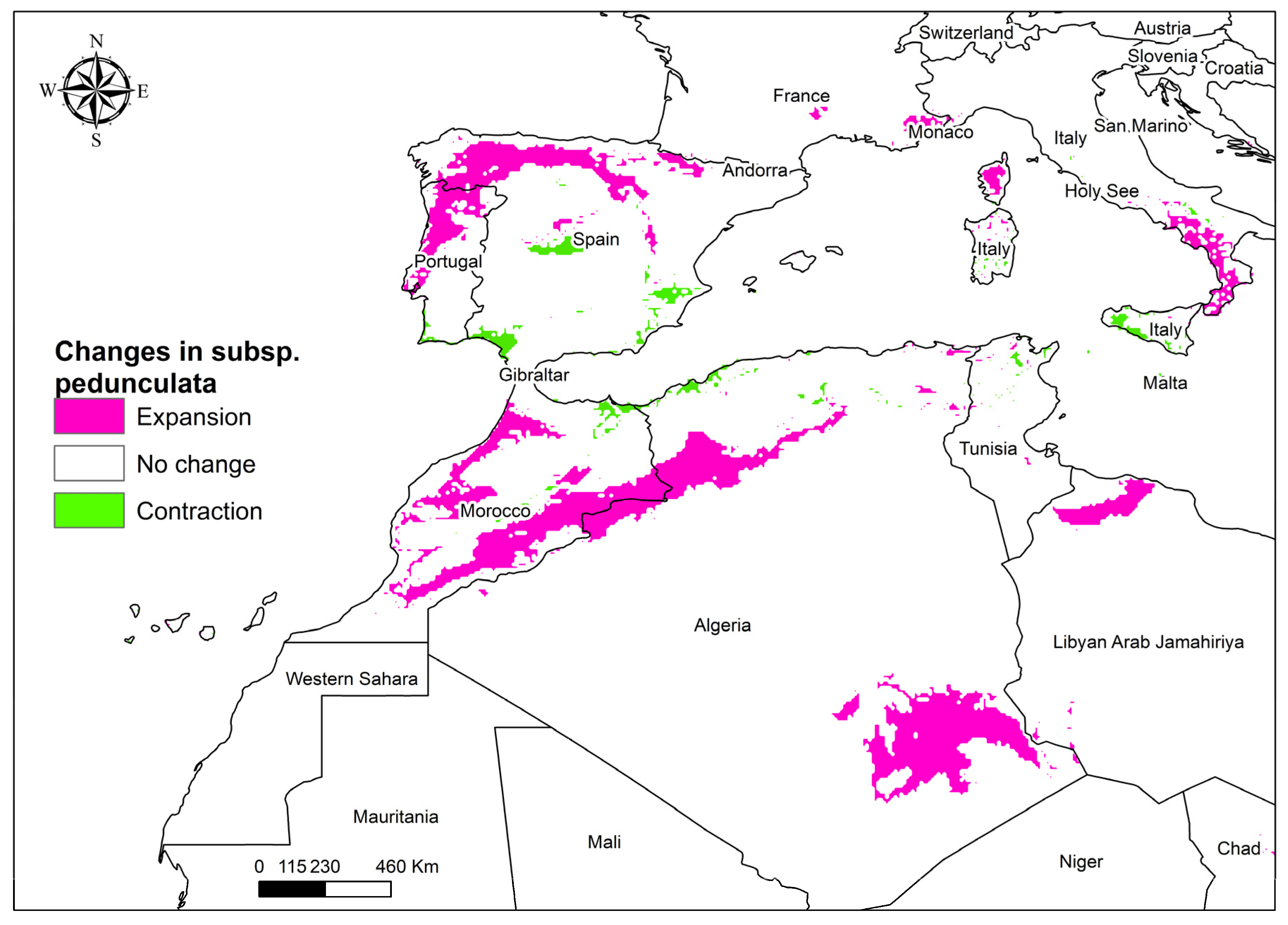

3.4. Future Global Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata

4. Discussion

4.1. Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica

4.2. Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata

4.3. Modeling Habitat for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata Under Climate Change

4.4. Research Limitations

4.5. Conservation Implications and Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Pasquale, G.; Saracino, A.; Bosso, L.; Russo, D.; Moroni, A.; Bonanomi, G.; Allevato, E. Coastal pine-oak glacial refugia in the Mediterranean basin: A biogeographic approach based on charcoal analysis and spatial modelling. Forests 2020, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.; Wejnert, K.E.; Hathaway, S.A.; Rochester, C.J.; Fisher, R.N. Effect of species rarity on the accuracy of species distribution models for reptiles and amphibians in southern California. Divers. Distrib. 2009, 15, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihama, F.; Takenaka, A.; Yokomizo, H.; Kadoya, T. Evaluation of the ecological niche model approach in spatial conservation prioritization. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fan, G.; He, Y. Predicting the current and future distribution of three Coptis herbs in China under climate change conditions, using the MaxEnt model and chemical analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sanchéz, F.; Arroyo, J. Reconstructing the demise of Tethyan plants: Climate-driven range dynamics of Laurus since the Pliocene. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008, 17, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commander, C.J.C.; Barnett, L.A.K.; Ward, E.J.; Anderson, S.C.; Essington, T.E. The shadow model: How and why small choices in spatially explicit species distribution models affect predictions. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walas, L.; Sobierajska, K.; Ok, T.; Dönmez, A.A.; Kanoğlu, S.S.; Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Douaihy, B.; Romo, A.; Stephan, J.; Jasińska, A.K.; et al. Past, present, and future geographic range of an oro-Mediterranean Tertiary relict: The Juniperus drupacea case study. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Schapire, R.E.; Blair, M.E. Opening the black box: An open-source release of Maxent. Ecography 2017, 40, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuel, A.; Eltahir, E.A.B. Why Is the Mediterranean a climate change hot spot? J. Clim. 2020, 33, 5829–5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The Relation between Climate Change in the Mediterranean Region and Global Warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedECC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin—Current Situation and Risks for the Future; First Mediterranean Assessment Report; MedECC Reports; MedECC Secretariat: Marseille, France, 2020; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Iglesias, A.; Lange, M.A.; Lionello, P.; Llasat, M.C.; Paz, S.; et al. Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F.; et al. Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Pietrapertosa, F.; Olazabal, M.; Simoes, S.G.; Salvia, M.; Fokaides, P.A.; Ioannou, B.I.; Viguié, V.; Spyridaki, N.-A.; Hurtado, S.G.; Geneletti, D.; et al. Adaptation to climate change in cities of Mediterranean Europe. Cities 2023, 140, 104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvà-Catarineu, M.; Romo, A.; Mazur, M.; Zielińska, M.; Minissale, P.; Dönmez, A.A.; Boratyńska, K.; Boratyński, A. Past, Present, and Future Geographic Range of the Relict Mediterranean and Macaronesian Juniperus phoenicea complex. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 5075–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Giorgi, F. Climate Change Hotspots in the CMIP5 Global Climate Model Ensemble. Clim. Change 2012, 114, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.; Hertig, E.; Tramblay, Y.; Scheffran, J. Climate Change Vulnerability, Water Resources and Social Implications in North Africa. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, J.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zeng, L.; He, R.; Guiang, M.M.; Li, Y.; Wu, H. Assessment of Chinese Suitable Habitats of Zanthoxylum nitidum in Different Climatic Conditions by Maxent Model, HPLC, and Chemometric Methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 196, 116515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applequist, W.L.; Brinckmann, J.A.; Cunningham, A.B.; Hart, R.E.; Heinrich, M.; Katerere, D.R.; van Andel, T. Scientists’ Warning on Climate Change and Medicinal Plants. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Wang, F.; Xia, P.; Zhao, G.; Wei, M.; Wei, F.; Han, R. Assessment of Suitable Cultivation Region for Panax notoginseng under Different Climatic Conditions Using MaxEnt Model and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.K.; Rana, H.K.; Ranjitkar, S.; Ghimire, S.K.; Gurmachhan, C.M.; O’Neill, A.R.; Sun, H. Climate-Change Threats to Distribution, Habitats, Sustainability and Conservation of Highly Traded Medicinal and Aromatic Plants in Nepal. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.-Z. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change and Habitat Suitability on the Distribution and Quality of Medicinal Plant Using Multiple Information Integration: Take Gentiana rigescens as an Example. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 123, 107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Meng, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, T.; Tao, J. Impact of Climate Factors on Future Distributions of Paeonia ostii Across China Estimated by MaxEnt. Ecol. Inform. 2019, 50, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, F.; Li, G.; Qin, W.; Li, S.; Gao, H.; Cai, Z.; Lin, G.; Zhang, T. Maxent Modeling for Predicting the Spatial Distribution of Three Raptors in the Sanjiangyuan National Park, China. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 6643–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Cui, X.; Sun, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Ye, X.; Fan, B. Analysis of the Distribution Pattern of Chinese Ziziphus jujuba under Climate Change Based on Optimized Biomod2 and MaxEnt Models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Phillips, S.J.; Hastie, T.; Dudík, M.; Chee, Y.E.; Yates, C.J. A Statistical Explanation of MaxEnt for Ecologists. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.; Almeida-Cortez, J.S.; Kleinschmit, B. Revealing Areas of High Nature Conservation Importance in a Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest in Brazil: Combination of Modelled Plant Diversity Hot Spots and Threat Patterns. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 35, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, Y.; Mou, Q.; Liu, K.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, B.; et al. Modeling Habitat Suitability of Houttuynia cordata Thunb (Ceercao) Using MaxEnt under Climate Change in China. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 63, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X. Moderate Warming Will Expand the Suitable Habitat of Ophiocordyceps sinensis and Expand the Area of O. sinensis with High Adenosine Content. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The Effect of Developmental and Environmental Factors on Secondary Metabolites in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xie, L.; Wang, H.; Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Ou, Z.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; et al. Geographic Distribution and Impacts of Climate Change on the Suitable Habitats of Zingiber Species in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 138, 111429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, F.; Chu, Q. Increasing Inconsistency between Climate Suitability and Production of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 171, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Wang, J.; Li, N. Climate Change Increases the Suitable Area and Suitability Degree of Rubber Tree Powdery Mildew in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, L.; He, Y. Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on the Distribution and Active Compound Content of the Plateau Medicinal Plant Nardostachys jatamansi (D. Don) DC. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Misra, A.; Kumar, B.; Adhikari, D.; Srivastava, S.; Barik, S.K. Identification of Potential Cultivation Areas for Centelloside-Specific Elite Chemotypes of Centella asiatica (L.) Using Ecological Niche Modeling. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Yu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W. Prediction of Suitable Planting Areas of Rubia cordifolia in China Based on a Species Distribution Model and Analysis of Specific Secondary Metabolites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 206, 117651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhang, B.; Chen, B.; Duan, D.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X. A Multi-Dimensional “Climate-Land-Quality” Approach to Conservation Planning for Medicinal Plants: Take Gentiana scabra Bunge in China as an Example. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.-G.; Liang, F.; Wu, K.; Xie, L.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y. The Potential Habitat of Angelica dahurica in China under Climate Change Scenario Predicted by MaxEnt Model. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1388099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, L.; Han, Y.; Wen, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, Q.; Peng, C.; He, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of the Effects of Climate Change on the Species Distribution and Active Components of Leonurus japonicus Houtt. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yao, L.; Meng, J.; Tao, J. MaxEnt Modeling for Predicting the Potential Geographical Distribution of Two Peony Species under Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, V.A.; Susanna, A.; Stuessy, T.F.; Bayer, R.J. Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Compositae; IAPT: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bardaweel, S.K.; Tawaha, K.A.; Hudaib, M.M. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activities of Anthemis palestina Essential Oil. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, V.; Dorizas, N.; Kypriotakis, Z.; Skaltsa, H.D. Analysis of the Essential Oil Composition of Eight Anthemis Species from Greece. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1104, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemsa, A.E.; Zellagui, A.; Öztürk, M.; Erol, E.; Ceylan, O.; Duru, M.E.; Lahouel, M. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant, Anticholinesterase, Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activities of Essential Oil and Methanolic Extract of Anthemis stiparum subsp. sabulicola (Pomel) Oberpr. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 119, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccobono, L.; Maggio, A.; Bruno, M.; Spadaro, V.; Raimondo, F.M. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils of Some Species of Anthemis sect. Anthemis (Asteraceae) from Sicily. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R. Genus anthemis L. In Flora Europaea; Tutin, T.G., Heywood, V.H., Burges, N.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976; Volume 4, pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bremer, K. Asteraceae, Cladistics and Classification; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, V.; Karioti, A.; Rancik, A.; Dimas, K.; Koukoulitsa, C.; Zervou, M. Sesquiterpene Lactones from Anthemis melanolepis and Their Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activities: Prediction of Their Pharmacokinetic Profile. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, A. The genus Anthemis L. (Compositae-Anthemideae), Arabian Peninsula: A taxonomic study. Pak. J. Bot. 2010, 42, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Labiad, H.; Et-tahir, A.; Ghanmi, M.; Satrani, B.; Aljaiyash, A.; Chaouch, A.; Fadli, M. Ethnopharmacological survey of aromatic and medicinal plants of the pharmacopoeia of northern Morocco. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kolli, M. Contribution Chimique Et De L’activité Antimicrobienne Des Huiles Essentielles d’Anthemis pedunculata Desp. D’anthemis Punctata Vahl. Et Daucus crinitus Desf. Master’s Dissertation, Université Ferhat Abbas, Setif, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Belahcene, N.; Messouak, E. Étude Comparative Des Activités Antioxydante, Antibactérienne Et Anti-Inflammatoire Des Composés Phénoliques De l’Anthemis pedunculata Et Matricaria chamomilla. Master’s Dissertation, Université Mohammed El Bachir El Ibrahimi B.B.A., El Anceur, Algeria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chermat, S.; Gharzouli, R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the northeast of Algeria—An Empirical Knowledge in Djebel Zdimm (Setif). J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 5, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Behbahani, B.; Noshad, M.; Mehrnia, M.A. Investigating the Antioxidant Potential and Antimicrobial Effect of Roman (Anthemis nobilis) Chamomile Essential Oil: “In Vitro”. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, J.D.; Todorova, M.N.; Evstatieva, L.N. Sesquiterpene Lactones as Chemotaxonomic Markers in Anthemis Genus. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouer, H.; Kolli, M.E.; Boulaacheb, N.; Akkal, S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil of Anthemis pedunculata and Anthemis punctata. Yanbu J. Eng. Sci. 2014, 9, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Floc’h, E.; Boulos, L. Vela E Flore de la Tunisie; Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable Banque de Genès: Tunis, Tunisia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gaamoune, S.; Nouioua, W. In vitro Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities assessment of flavonoids crude extract of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica (Pomel) Oberpr., aerial parts. Alger. J. Biosci. 2023, 4, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezudo, B.; Solanas, F.C.S.; Pérez-Latorre, A.V. Vascular flora of the Sierra de las Nieves National Park and its surroundings (Andalusia, Spain). Phytotaxa 2022, 534, 1–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayf-eddine, B.; Bussmann, R.W.; Elachouri, M. Anthemis arvensis L. Anthemis cotula L. Anthemis pedunculata Desf. Anthemis pseudocotula Boiss. Anthemis rascheyana Boiss.: Asteraceae. In Ethnobotany of Northern Africa and Levant; Bussmann, R.W., Elachouri, M., Kikvidze, Z., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Boria, R.A.; Radosavljevic, A.; Vilela, B.; Anderson, R.P. spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography 2015, 38, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boria, R.A.; Olson, L.E.; Goodman, S.M.; Anderson, R.P. Spatial Filtering to Reduce Sampling Bias Can Improve the Performance of Ecological Niche Models. Ecol. Model. 2014, 275, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer-Schadt, S.; Niedballa, J.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Schröder, B.; Lindenborn, J.; Reinfelder, V.; Stillfried, M.; Heckmann, I.; Scharf, A.; Augeri, D.; et al. The Importance of Correcting for Sampling Bias in MaxEnt Species Distribution Models. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisz, M.S.; Hijmans, R.J.; Li, J.; Peterson, A.T.; Graham, C.H.; Guisan, A. Effects of sample size on the performance of species distribution models. Divers. Distrib 2008, 14, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Nakamura, M.; Peterson, A.T. Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: A test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J. Biogeogr. 2007, 34, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcheglovitova, M.; Anderson, R.P. Estimating optimal complexity for ecological niche models: A jackknife approach for species with small sample sizes. Ecol. Model. 2013, 269, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.T.; Papeş, M.; Soberón, J. Rethinking receiver operating characteristic analysis applications in ecological niche modeling. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.S.; Kumar, L.; Shabani, F.; Picanço, M.C. Mapping Global Risk Levels of Bemisia tabaci in Areas of Suitability for Open Field Tomato Cultivation under Current and Future Climates. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellert, K.H.; Fensterer, V.; Küchenhoff, H.; Reger, B.; Kölling, C.; Klemmt, H.J.; Ewald, J. Hypothesis-Driven Species Distribution Models for Tree Species in the Bavarian Alps. J. Veg. Sci. 2011, 22, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Bennett, J.R.; French, C.M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: The Next Generation Python-Based GIS Toolkit for Landscape Genetic, Biogeographic and Species Distribution Model Analyses. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.G.; Pillar, V.D.; Palmer, A.R.; Melo, A.S. Predicting the Current Distribution and Potential Spread of the Exotic Grass Eragrostis plana Nees in South America and Identifying a Bioclimatic Niche Shift during Invasion. Austral Ecol. 2013, 38, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.S.; Kumar, L.; Shabani, F.; da Silva, R.S.; de Araújo, T.A.; Picanço, M.C. Climate Model for Seasonal Variation in Bemisia tabaci Using CLIMEX in Tomato Crops. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Z.; Nemomissa, S.; Lemessa, D. Predicting the Distributions of Pouteria adolfi-friederici and Prunus africana Tree Species under Current and Future Climate Change Scenarios in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Ecol. 2023, 61, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatebe, H.; Ogura, T.; Nitta, T.; Komuro, Y.; Ogochi, K.; Takemura, T.; Sudo, K.; Sekiguchi, M.; Abe, M.; Saito, F.; et al. Description and Basic Evaluation of Simulated Mean State, Internal Variability, and Climate Sensitivity in MIROC6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 2727–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; A Boria, R.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; Anderson, R.P. ENMeval: An R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for MAXENT ecological niche models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monier-Corbel, A.; Robert, A.; Hingrat, Y.; Benito, B.M.; Monnet, A.-C. Species Distribution Models predict abundance and its temporal variation in a steppe bird population. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 43, e02442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Jaimes, J.; González-Fernández, A.; Torres-Romero, E.J.; Bolom-Huet, R.; Manjarrez, J.; Gopar-Merino, F.; Pacheco, X.P.; Garrido-Garduño, T.; Chávez, C.; Sunny, A. Impact of climate and land cover changes on the potential distribution of four endemic salamanders in Mexico. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 64, 126066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.T.; Soberón, J.; Pearson, R.G.; Anderson, R.P.; Martínez-Meyer, E.; Nakamura, M.; Araújo, M.B. Ecological Niches and Geographic Distributions; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011; 314p, ISBN 978-0-691-13686-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar, J.N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand, D.J.; Anagnostopoulos, C. When is the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve an appropriate measure of classifier performance? Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2013, 34, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, O.F.; Souza, P.G.; da Silva, R.S.; Santana, P.A.; Picanço, M.C.; Kyerematen, R.; Sètamou, M.; Ekesi, S.; Borgemeister, C. Climate-induced range shifts of invasive species (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama). Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2534–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidoo, O.F.; da Silva, R.S.; Junior, P.A.S.; Souza, P.G.C.; Kyerematen, R.; Owusu-Bremang, F.; Yankey, N.; Borgemeister, C. Model-based prediction of the potential geographical distribution of the invasive coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis Keifer (Acari: Eriophyidae) based on MaxEnt. Agric. For. Entomol. 2022, 24, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahatara, D.; Acharya, A.K.; Dhakal, B.P.; Sharma, D.; Ulak, S.; Paudel, P. Maxent modelling for habitat suitability of vulnerable tree Dalbergia latifolia in Nepal. Silva Fenn. 2021, 55, 10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, A.; Ramos, R.S.; da Silva, R.S.; Soares, J.R.S.; Picanço, M.C.; Fidelis, E.G. Risk of the introduction of Lobesia botrana in suitable areas for Vitis vinifera. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qi, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, P.; Wang, X. Applying Specific Habitat Indicators to Study Asteraceae Species Diversity Patterns in Mountainous Area of Beijing, China. Forests 2024, 15, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpis, J.; Serrato-Cruz, A.M.; Arroyo, T.P.F. Modeling the Effects of Climate Change on the Distribution of Tagetes lucida Cav. (Asteraceae). Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, Y.; Zurano, J.P.; Ribeiro-Junior, M.A.; Avila-Pires, T.C.; Rodrigues, M.T.; Colli, G.R.; Werneck, F.P. The combined role of dispersal and niche evolution in the diversification of Neotropical lizards. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 2608–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafati, A.; Pezeshki, E. A strategy to assess the uncertainty of a climate change impact on extreme hydrological events in the semi-arid Dehbar catchment in Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 139, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.M.; Chen, F.S.; Sun, R.X.; Wu, N.S.; Liu, B.; Song, Y.L. Prediction of Potential Suitable Distribution Areas for Choerospondias axillaris besed on MaxEnt Model. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis 2019, 41, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Chang, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C. The potential geographical distribution of Haloxylon across Central Asia under climate change in the 21st century. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 275, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Z.; Zhao, G.H.; Zhang, M.Z.; Cui, X.Y.; Fan, H.H.; Liu, B. Distribution Pattern of Endangered Plant Semiliquidambar cathayensis (Hamamelidaceae) in Response to Climate Change after the Last Interglacial Period. Forests 2020, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, B.; Bai, C.; Li, G.; Mao, M. Predicting suitable cultivation regions of medicinal plants with Maxent modeling and fuzzy logics: A case study of Scutellaria baicalensis in China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan-Cisneros, C.M.; Villa, P.M.; Coelho, A.J.P.; Campos, P.V.; Meira-Neto, J.A.A. Altitude as environmental filtering influencing phylogenetic diversity and species richness of plants in tropical mountains. J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, A.; Orücü, O.K.; Arslan, E.S.; Sarıkaya, A.G. Predicting of the current and future geographical distribution of Laurus nobilis L. under the effects of climate change. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, A.; Ning, X.; Fan, G.; Wu, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Prediction of the potentially suitable areas of Litsea cubeba in China based on future climate change using the optimized MaxEnt model. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, G. Is climate change threatening or beneficial to the habitat distribution of global pangolin species? Evidence from species distribution modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 151385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C.; Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 2003, 421, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulliam, H. On the relationship between niche and distribution. Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberon, J.; Peterson, A.T. Interpretation of models of fundamental ecological niches and species’ distributional areas. Biodivers. Inform. 2005, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.A.; Griffiths, G.; Lukac, M. Land use and climate change interaction triggers contrasting trajectories of biological invasion. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.D.; Cameron, A.; Green, R.E.; Bakkenes, M.; Beaumont, L.J.; Collingham, Y.C.; Erasmus, B.F.N.; de Siqueira, M.F.; Grainger, A.; Hannah, L.; et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 2004, 427, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Thuiller, W.; Leroy, B.; Genovesi, P.; Bakkenes, M.; Courchamp, F. Will climate change promote future invasions? Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 3740–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwarahm, N.R. Mapping current and potential future distributions of the oak tree (Quercus aegilops) in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yin, Q.; Sang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Jia, Z.; Ma, L. Prediction of potentially suitable areas for the introduction of Magnolia wufengensis under climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yuan, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y. Species distribution modeling based on MaxEnt to inform biodiversity conservation in the Central Urban Area of Chongqing Municipality. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadieux, P.; Boulanger, Y.; Cyr, D.; Taylor, A.R.; Price, D.T.; Sólymos, P.; Stralberg, D.; Chen, H.Y.; Brecka, A.; Tremblay, J.A. Projected effects of climate change on boreal bird community accentuated by anthropogenic disturbances in western boreal forest, Canada. Divers. Distrib. 2020, 26, 668–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.S.; Ortiz, E.; Villaseñor, J.L.; Espinosa-García, F.J. The distribution of cultivated species of Porophyllum (Asteraceae) and their wild relatives under climate change. Syst. Biodivers. 2016, 14, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjerehei, M.M.; Rundel, P.W. The Impact of Climate Change on Habitat Suitability for Artemisia sieberi and Artemisia aucheri (Asteraceae)—A Modeling Approach. Pol. J. Ecol. 2017, 65, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.; Mehrabian, A.; Mostafavi, H. The distribution patterns and priorities for conservation of monocots Crop Wild relatives (CWRs) of Iran. J. Wildl. Biodivers. 2021, 5, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soilhi, Z.; Sayari, N.; Benalouache, N.; Mekki, M. Predicting current and future distributions of Mentha pulegium L. in Tunisia under climate change conditions, using the MaxEnt model. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z. The impact of climate change on the distribution of rare and endangered tree Firmiana kwangsiensis using the Maxent modeling. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.-B.; Wang, L.-Y.; Wang, L.-J.; Jia, Y.; Li, Z.-H.; Bai, G.; Zhao, R.-M.; Liang, W.; Wang, H.-Y.; Guo, F.-X.; et al. Distributional response of the rare and endangered tree species Abies chensiensis to climate change in east Asia. Biology 2022, 11, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, S.; Abedi, R.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A. Which environmental factors are more important for geographic distributions of Thymus species and their physio-morphological and phytochemical variations? Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolyat, M.A.; Afshari, R.T.; Jahansoz, M.R.; Nadjafi, F.; Naghdibadi, H.A. Determination of cardinal germination temperatures of two ecotypes of Thymus daenensis subsp. daenensis. Seed Sci. Technol. 2014, 42, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, B.; Rahimmalek, M.; Arzani, A. Essential oil composition, total phenolic, flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activity of Thymus species collected from different regions of Iran. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, B.; Rahimmalek, M.; Trindade, H. Review on essential oil, extracts composition, molecular and phytochemical properties of Thymus species in Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majd, M.; Dastjerdi, J.K.; Sefidkon, F.; Lebasschi, M.; Baratian, A. Determination of the Effects of Climate on Growth and Phenological Stage of Thymus daenensis for Cultivation in Different Geographical Regions. Phys. Geogr. Res. 2021, 53, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Sun, S.; Wang, N.; Fan, P.; You, C.; Wang, R.; Zheng, P.; Wang, H. Dynamics of the distribution of invasive alien plants (Asteraceae) in China under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guisan, A.; Zimmermann, N.E. Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology. Ecol. Model. 2000, 135, 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; Guisan, A. Five (or) so challenges for species distribution modelling. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M. Habitat, environment and niche: What are we modelling? Oikos 2006, 115, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, R.; Quesada, M.; Ashworth, L.; Herrerias-Diego, Y.; Lobo, J. Genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation in plant populations: Susceptible signals in plant traits and methodological approaches. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 5177–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnay, O.; Jacquemyn, H. Susceptibility of common and rare plant species to the genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.P.; Kiers, E.T.; Driessen, G.; van der Heijden, M.; Kooi, B.W.; Kuenen, F.; Liefting, M.; Verhoef, H.A.; ELLERS, J. Adapt or disperse: Understanding species persistence in a changing world. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate-Escobedo, J.; Castañeda-González, E.L.; Cuevas-Sánchez, J.A.; Carrillo-Fonseca, C.L.; Ortiz-Torres, C.; Ibarra-Estrada, E.; Serrato-Cruz, M.A. Essential oil of some populations of Tagetes lucida cav. from the northern and southern regions of the state of Mexico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2018, 41, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasenor, J.L.; Ibarra, G.; Ocana, D. Strategies for the conservation of Asteraceae in Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.A. Use of maximum entropy modeling in wildlife research. Entropy 2009, 11, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Liu, B.; Guo, Q.; Bussmann, R.W.; Ma, F.; Jian, Z.; Xu, G.; Pei, S. Maxent modeling for predicting impacts of climate change on the potential distribution of Thuja sutchuenensis Franch. an extremely endangered conifer from southwestern China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.A.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Fagan, W.F.; Fryxell, J.M.; Van Moorter, B.; Alberts, S.C.; Ali, A.H.; Allen, A.M.; Attias, N.; Avgar, T.; et al. Moving in the Anthropocene: Global reductions in terrestrial mammalian movements. Science 2018, 359, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaneh, J.M.; Ahmadi, J.; Rahmanian, S.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Nasiri, V.; Borz, S.A. Prediction of wild pistachio ecological niche using machine learning models. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 72, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Q.; Liu, C.C.; Liu, Y.G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.S.; Guo, K. Advances in theoretical issues of species distribution models. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 4827–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissovsky, A.A.; Dudov, S.V. Species-distribution modeling: Advantages and limitations of its application. 1. General Approaches. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2021, 11, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, A.; Deka, J.R.; Nath, P.C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nath, A.J.; Giri, K.; Das, A.K. Modelling habitat suitability of the critically endangered Agarwood (Aquilaria malaccensis) in the Indian East Himalayan region. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 4787–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, D.; Lathrop, R.G.; Santos, C.D.; Paludo, D.; Niles, L.; Smith, J.A.M.; Feigin, S.; Dey, A. Distribution modeling and gap analysis of shorebird conservation in Northern Brazil. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhou, L.; Qi, S.; Jin, M.; Hu, J.; Lu, J. Effect of habitat factors on the understory plant diversity of Platycladus orientalis plantations in Beijing mountainous areas based on MaxEnt model. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H. Using maxent model to guide marsh conservation in the Nenjiang River Basin. Northeast China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, K.O.; Khwarahm, N.R. An integrated approach to map the impact of climate change on the distributions of Crataegus azarolus and Crataegus monogyna in Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, A.A.; Khwarahm, N.R. Predictive mapping of two endemic oak tree species under climate change scenarios in a semiarid region: Range overlap and implications for conservation. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 73, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Alatalo, J.M.; Yang, Z. Mapping biodiversity conservation priorities for protected areas: A case study in Xishuangbanna Tropical Area. China. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 249, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, G.M.; Cotrina-Sanchez, A.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Rojas-Briceño, N.B.; Guzmán, C.T.; Castro, E.C.; Oliva, M. Does climate change impact the potential habitat suitability and conservation status of the national bird of Peru (Rupicola peruvianus)? Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 2323–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zeng, W.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, G.; Li, Q.; Cao, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Zhang, T. Boundary delineation and grading functional zoning of Sanjiangyuan National Park based on biodiversity importance evaluations. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code/Unit | Environmental Variable |

|---|---|

| BIO_1 (°C) | Annual Mean Temperature |

| BIO_2 (°C) | Mean Diurnal Range (mean of monthly (max temp-min temp)) |

| BIO_3 (%) | Isothermality (BIO2/BIO7) (×100) |

| BIO_4 (°C) | Temperature Seasonality (standard deviation × 100) |

| BIO_5 (°C) | Max Temperature of Warmest Month |

| BIO_6 (°C) | Min Temperature of Coldest Month |

| BIO_7 (°C) | Annual Temperature Range (BIO5-BIO6) |

| BIO_8 (°C) | Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO_9 (°C) | Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter |

| BIO_10 (°C) | Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter |

| BIO_11 (°C) | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter |

| BIO_12 (mm) | Annual Precipitation |

| BIO_13 (mm) | Precipitation of Wettest Month |

| BIO_14 (mm) | Precipitation of Driest Month |

| BIO_15 (mm) | Precipitation Seasonality (coefficient of variation) |

| BIO_16 (mm) | Precipitation of Wettest Quarter |

| BIO_17 (mm) | Precipitation of Driest Quarter |

| BIO_18 (mm) | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter |

| BIO_19 (mm) | Precipitation of Coldest Quarter |

| BIO_20 (m) | Elevation |

| Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica | Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Contribution (%) | Variable | Contribution (%) |

| BIO_9 | 30.2 | BIO_18 | 39.3 |

| BIO_6 | 27.7 | BIO_19 | 30.8 |

| BIO_8 | 26.1 | BIO_5 | 20.5 |

| BIO_3 | 8.3 | BIO_20 | 9.4 |

| BIO_15 | 7.7 | ||

| Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 2030 | 2050 | |

| Suitable | 25.47 | 27.08 | 29.04 |

| Unsuitable | 74.53 | 72.92 | 70.96 |

| Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica (ha) | |||

| 2024 | 2030 | 2050 | |

| Suitable | 201,179,880 | 213,898,608 | 229,357,062 |

| Unsuitable | 588,711,123 | 575,992,395 | 560,533,941 |

| Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. penduculata (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 2030 | 2050 | |

| Suitable | 12.62 | 18.35 | 18.72 |

| Unsuitable | 87.38 | 81.65 | 81.28 |

| Distribution of Anthemis pedunculata subsp. penduculata (ha) | |||

| 2024 | 2030 | 2050 | |

| Suitable | 99,330,066 | 144,365,562 | 147,335,265 |

| Unsuitable | 687,601,233 | 642,565,737 | 639,596,034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mechergui, K.; Jaouadi, W.; Azevedo, C.H.S.; Faqeih, K.Y.; Alamri, S.M.; Alamery, E.R.; Aldubehi, M.A.; Souza, P.G.C. Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata and Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica in Mediterranean Region Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis. Diversity 2025, 17, 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120851

Mechergui K, Jaouadi W, Azevedo CHS, Faqeih KY, Alamri SM, Alamery ER, Aldubehi MA, Souza PGC. Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata and Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica in Mediterranean Region Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):851. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120851

Chicago/Turabian StyleMechergui, Kaouther, Wahbi Jaouadi, Carlos Henrique Souto Azevedo, Khadeijah Yahya Faqeih, Somayah Moshrif Alamri, Eman Rafi Alamery, Maha Abdullah Aldubehi, and Philipe Guilherme Corcino Souza. 2025. "Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata and Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica in Mediterranean Region Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis" Diversity 17, no. 12: 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120851

APA StyleMechergui, K., Jaouadi, W., Azevedo, C. H. S., Faqeih, K. Y., Alamri, S. M., Alamery, E. R., Aldubehi, M. A., & Souza, P. G. C. (2025). Modeling Habitat Suitability for Endemic Anthemis pedunculata subsp. pedunculata and Anthemis pedunculata subsp. atlantica in Mediterranean Region Using MaxEnt and GIS-Based Analysis. Diversity, 17(12), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120851