Abstract

Diatoms are of major importance in marine and freshwater systems, but their occurrence in terrestrial situations is generally thought to be exceptional. Following up on the accidental discovery of epiphytic diatoms on bark samples in an unrelated study, we investigated their presence in the tropical lowlands of Panama more systematically using scanning electron and light microscopy. We sampled inundated and aerial bark portions of Annona glabra, a tree that grows along the shore of Lake Gatun, and took bark samples from other tree and liana species at c. 1.5 m height in the forest understory. In total, we found 70 diatom taxa in 28 genera. Species numbers and composition differed among the three microhabitats with the largest numbers on inundated bark portions, but even in the forest understory, we found 12 taxa with densities of up to 900 frustules per mm−2 of bark. Our data set is still quite limited in scale but the results suggest the possibility that hitherto unacknowledged assemblages of epiphytic diatoms may be quite common in wet tropical forests, which clearly warrants further study.

1. Introduction

Aerial algae that grow on the surfaces of terrestrial plants such as on tree bark are called epiphytic or corticolous. The algal communities from that substrate described in the literature are typically dominated by green algae and cyanobacteria [1], while diatoms, with enormous ecological importance in marine and fresh waters, are either not reported at all (e.g., [2,3]) or comprise just a few taxa with low abundance in published species lists (e.g., [4,5,6]). This led Graham, Graham, and Wilcox [1] to the statement that diatoms are a “minor component of epiphytic communities … limited to very wet surfaces”. Given such a statement, it is not surprising that there is a strong bias in the literature towards searching for aerial diatoms as commensals in epiphytic bryophytes as a tree microhabitat with comparatively high moisture [7,8,9,10]. Even texts specifically dedicated to diatoms like Round et al. [11]’s monograph only briefly mention aerial forms, i.e., diatoms growing on wet rocks or between the leaflets of bryophytes, but do not mention any occurrence on bark. In Benito and Fritz [12]’s treatise of diatom diversity and biogeography in tropical South America, terrestrial occurrences are not mentioned at all.

The reason that so few studies mention the occurrence of diatoms on bare bark could simply reflect their true absence, because bark constitutes a microhabitat that is too dry for members of this group. Alternatively, they may have been overlooked and, indeed, there is evidence that supports such doubts. For example, Bock [13] found more than 100 species of diatoms with relatively high abundances at microsites without moss on walls and cliffs under rather dry climatic conditions in northern Bavaria in Germany, and Rybak et al. [14], studying diatoms on bare bark, moss clumps, and bark covered with lichens of three different tree species in Poland, reported substantial diversity and abundances of diatoms in all three microhabitats. As others before (e.g., [15]), Rybak, Czarnota, and Noga [14] emphasise that our understanding of these epiphytic communities is rudimentary at best, and generalisations should be made with caution. The characterisation of our knowledge as limited is particularly true for the tropics. There, aerial diatoms are only well known and rather consistently documented in one special micro-limnic system, phytotelmata of epiphytic bromeliads (e.g., [16,17,18,19,20]). Other studies in the tropics on diatoms focus almost exclusively on their occurrence in rivers and other water bodies (e.g., [21,22,23]), while the very few reports on aerial diatoms are limited to algae associated with epiphytic lichens [24,25] or mosses [9,26,27].

We got interested in diatoms on tree bark in the tropics by chance when investigating the attachment mechanism of roots of vascular epiphytes [28]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of pieces of bark and orchid roots that we collected in a lowland forest of Panama clearly showed numerous diatoms frustules on roots and bark [29]. After this surprising observation, we started to screen bark samples systematically with SEM for the presence of diatoms, quantified their abundance, identified taxa, and also studied live samples to make sure that we were not simply documenting passively dispersed, dead organisms. Finally, we did some preliminary sampling along the vertical profile of the forest and provide first evidence that the occurrence of diatoms is not restricted to the lowermost parts of the studied lowland forest—we even found a few diatoms on bark as high as 25 m (Tay and Zotz, unpubl. obs.).

When presenting our observations, we are fully aware that more detailed studies will be necessary to corroborate our preliminary findings, but given the very limited knowledge on the occurrence of diatoms on trees in the tropics, we hope that this report will stimulate further studies on aerial diatoms in the wet tropics.

2. Materials and Methods

Study site. The Barro Colorado Nature Monument (BCNM), situated in the man-made Gatun Lake as part of the Panama Canal, is covered by a tropical moist lowland forest [30]. The average annual rainfall on Barro Colorado Island is c. 2600 mm [31] with a pronounced dry season of about four months from late December to April. General information on the vegetation can be found in Croat [32] and Leigh et al. [33]. Stands of the inundation-tolerant tree, Annona glabra L., are a characteristic feature of the shorelines [34].

Field sampling. In early 2022, we collected bark samples of around 3–4 cm2, which were free of lichens or mosses, from three different (micro)habitat types: (1) bark from the inundated stem base of Annona glabra (S = submerged), typically one sample per tree; (2) bark from the same trees, but above the so-called lichen line [35] at about 50 cm above the water table (A = Annona stem), and (3) bark samples from trees and lianas from the understory of the BCNM forest, at c. 1.4 m above ground (F = forest). Samples were preserved in 50% ethanol for export to Germany. We also climbed a tall Anacardium excelsum L. tree and collected similar bark samples from 7 m, 12 m, and 25 m. All samples were transferred to Germany for further study.

To determine if the diatom cells were alive at the time of study, in early 2025, we sampled five pieces of bark from the submerged portion of Annona glabra trees and from wet bark of trees in the forest understory. Using a pipette, we transferred liquid samples to an object plate and studied them with a Zeiss Axio Scope A1 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Oldenburg). A total of 20 samples were chosen, including 4 samples of the category S, 10 of category A, and 6 of category F. Each sample was further cut into 2 × 2 mm pieces, of which 5 pieces were haphazardly chosen and prepared for SEM. The samples were dehydrated in an ascending alcohol series of 60, 70 (with vacuum), 80, 90, 99, 99, and 100% absolute EtOH (v/v), changing the dilution every 30 min, with an additional 1 h in the last step. Samples were then dried with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS). After incubation for 15 min in 2 mL EtOH:HMDS (1:1, v/v) and then for 15 min in 1 mL HMDS, samples were left to dry in a desiccator for one day. Dried samples were mounted onto aluminium stubs (1 cm diameter) with black carbon adhesive stickers (Plano, Wetzlar, Germany). Finally, the samples were coated with 15 nm gold in a sputter coater (SCD 005, Bal Tec, Pfäffikon, Switzerland). Imaging was performed with a SEM, first with the Hitachi S-3200N (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and later with the JSL-IT800 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), under high vacuum (20 kV accelerating voltage). To quantify the number of diatoms, present on each sample, five points on the samples were selected, one in the centre and one in each corner. At each sample point, the magnification was set at 1000× and a digital image was taken. All diatoms within the image were counted (including those for which more than half of the frustule was visible), and the abundance was expressed as the number of diatoms per square millimetre.

Diatom analysis (Berlin). A second set of 20 parallel samples was used to characterise the diatom assemblages taxonomically (4 2 × 2 mm samples of the category S, 10 of category A, and 6 of category F). Briefly, cell contents were oxidised using 35% hydrogen peroxide and rinsed using centrifugation (10 min at 2000 rpm). Cleaned valves were mounted on glass slides for LM using Naphrax. For SEM, the valves were dried on 10 × 10 mm silicon wafer chips and mounted on stubs. Unsputtered valves were examined at 1 kV accelerating voltage using a Hitachi SU 800 SEM. For the identification of the diatom assemblages, the valves were observed using a 100× objective (1.4 numerical aperture) with the Zeiss Axio-Scope A1 microscope. All taxa were photographed using an AxioCam ICm1 camera (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and differential interference contrast. Images were arranged and cropped using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. Samples and slides are stored at the Diatom Collection of the Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin–Dahlem, Freie Universität Berlin. Only intact frustules or fragments whose size exceeded half the shell area were taken into account [36]. Identification of taxa was based on light microscopy using the following references: [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Whenever possible, the identification literature from Central America and the Caribbean was consulted, but often the European literature had to be used. Taxa identified with ‘cf.’ (confer) before the epithet indicate that the taxonomic identity is still uncertain, and ‘sp.’ (species) was used when the taxon showed no similarity with any known species based on the literature review.

Statistical analysis. Differences in diatom density and species numbers between samples from the three microhabitats were analysed with a Kruskal–Wallis test, because the data did not meet the requirements of a parametric ANOVA. When significant, a Dunn test was used as a post hoc test. Differences in the composition of the 17 assemblages with diatoms were assessed using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). The NMDS was performed using the package vegan (version 2.6-10) with the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index as the distance measure [50]. All analyses were performed with R version 4.3.3. [51].

3. Results

3.1. Density Estimates

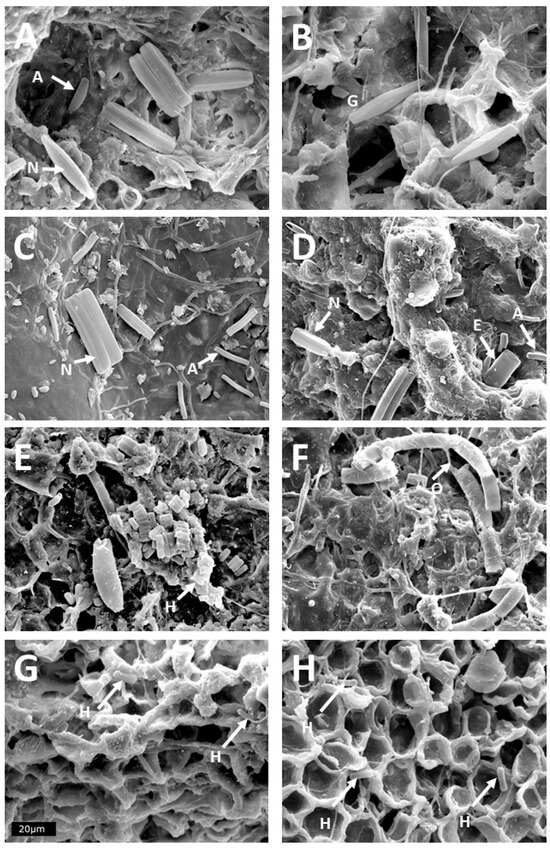

Diatom cell densities on the permanently inundated portions of stems of Annona glabra trees varied relatively little, with an average of c. 350 frustules mm−2 bark surface (Table 1). The average number of diatoms on bark samples of Annona glabra from about 50 cm above the water table reached only about 120 frustules mm−2, but variation was substantial. Two samples were completely devoid of diatoms or had densities that were at least very low, but in a few cases, diatom numbers were similar or even higher than the densities of the samples from submerged bark (Sample 13 and 14, Table 1, Figure 1). Variation was even larger among bark samples from trees and lianas from the forest understorey: with 180 frustules mm−2, average diatom densities were slightly higher than those of Annona bark, but ranged from zero to the highest density documented in this study: almost 900 diatom frustules mm−2 were found on a piece of liana bark (Sample 20, Table 1, Figure 1E). Although suggestive, the differences in diatom densities between microhabitat types were not significant (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.13). On the bark samples collected at 7, 12, and 25 m heights, diatoms were consistently very rare, but they were not entirely absent: an extensive search yielded at least one or two frustules per sample.

Table 1.

Diatom counts of samples from three different habitat types at BCNM: S = submerged parts of Annona glabra trunks, A = aerial parts of Annona glabra trunks, 50 cm above the water table, and F = forest understory at 1.4 m height. Given are details of the sampling site in BCNM, e.g., the location along the BCNM trail system, the density of diatoms (means ± SD, n = 5), and the number of taxa. Details on the latter are given in Table 2.

Figure 1.

SEM pictures of diatoms on trees in the tropical lowlands. (A,B) Stem base of Annona glabra that is permanently inundated: A: Nitzschia, Achnanthidium; B: Gomphonema. (C,D) Annona glabra stem, about 50 cm above the water table in the dry season: C: Nitzschia, Achnanthidium; D: Nitzschia, Achnanthidium, Eunotia. (E,F) liana bark at about 1.4 m above ground in the forest of BCNM: F: Orthoseira; (G) tree bark at about 1.4 m in the forest of BCNM: Humidophila; (H) diatoms on an aerial root of Aspasia principissa at c. 1.2 m above ground: 1H: Humidophila. Scale is 20 µm, so the area of each picture is 0.012 mm2. Arrows highlight some of the diatoms, and initials A, E, G, H, N, O identify the respective genus.

3.2. Alive or Not?

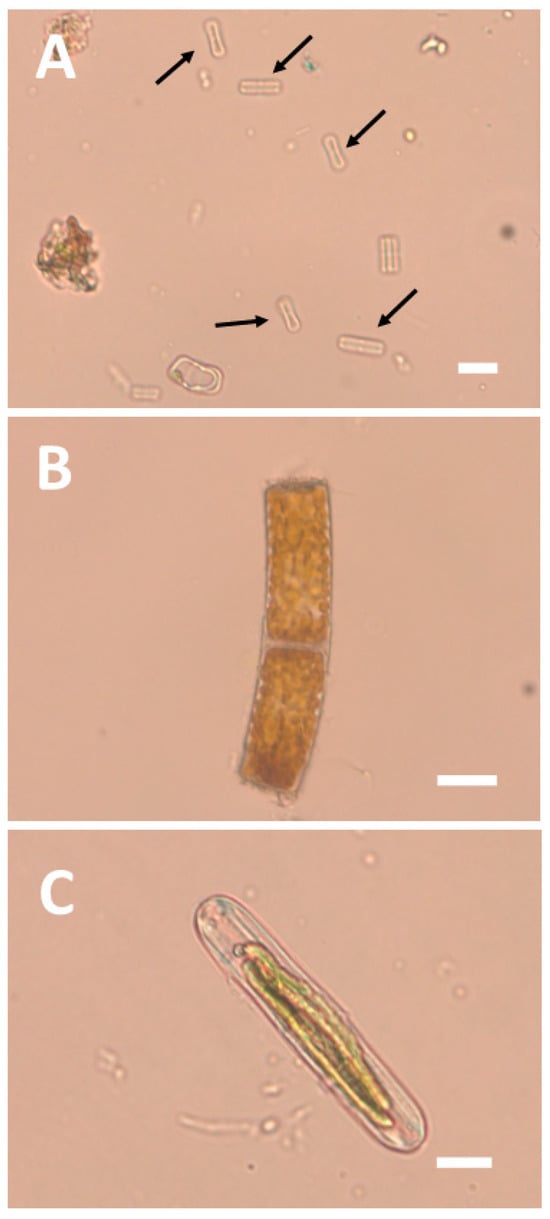

Studying samples stored in alcohol cannot unambiguously demonstrate that the observed diatoms had been alive at the time of sampling. Frustules or parts of them can remain on bark long after the cell has died or has been transported from elsewhere. For this reason, we also studied freshly collected material using light microscopy. Material was collected in the forest understory at about 1.4 m height after a few heavy rains in the dry season of 2025. We found numerous frustules, most of which were dead. However, we also found a substantial number of diatoms (c. 30% of the total) with intact chloroplasts, and some of the raphe-bearing ones were actually moving (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

LM pictures of diatoms from tree bark in the understory of the BCNM forest. (A) numerous small and supposedly dead diatoms of the genus Humidophila (black arrows); (B) live Orthoseira sp. cells; and (C) live Naviculales cell. Scale bars: 10 µm.

3.3. Taxonomic Composition of Diatom Assemblages

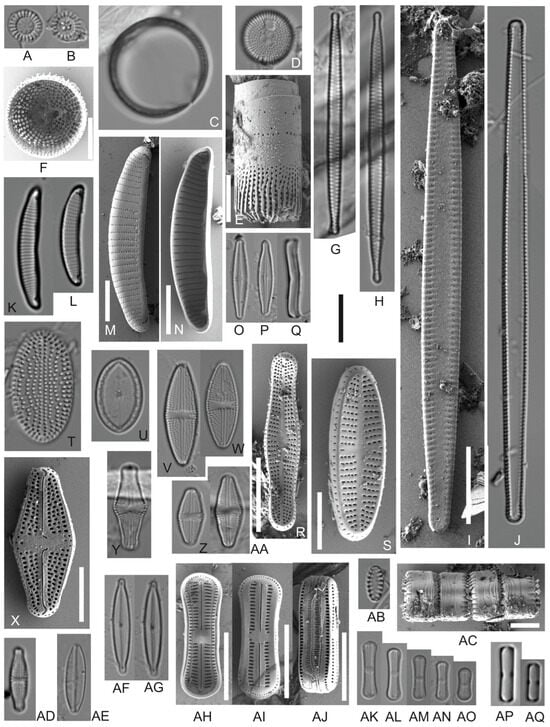

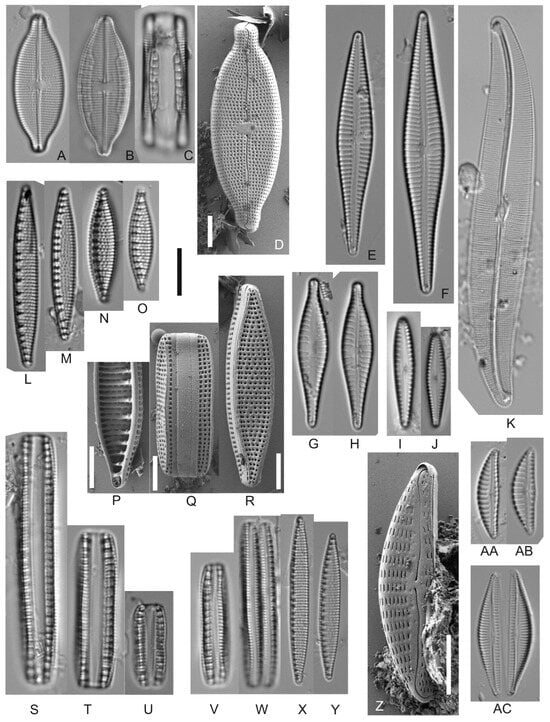

In three of the aerial samples, no diatoms were found (two forest understory samples and one aerial Annona trunk sample, Table 1). Using LM and SEM, we distinguished 70 taxa belonging to 28 genera in the 17 samples with diatoms (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Of those taxa, 15 taxa could be identified at the species level, in another 21 cases, species identification was uncertain (“cf.”), and in 35 cases, it was not even possible to go beyond the genus level (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Overview of the most abundant taxa (part 1). LM (A–D,F,G,I–K,N–P,S–V,X–AA,AC–AF,AJ–AP) and SEM (E,H,L,M,Q,R,W,AB,AG–AI). (A,B) Cyclotella stelligera; (C) Pleurosira sp.; (D–F) Orthoseira roeseana; (G,H) Fragilaria cf. tenera; (I,J) Tabularia sp.; (K–N) Eunotia cf. veneris; (O–R) Achnanthidium cf. exile; (S) Achnanthidium cf. minutissimum; (T) Cocconeis fluviatilis; (U) Cocconeis sp.; (V,W) Luticola sp.; (X,Z,AA) Luticola cf. intermedia; (Y) Luticola hustedtii; (AB,AC) Staurosira sp.; (AD) Sellaphora sp.; (AE) Adlafia sp.; (AF,AG) Encyonopsis cf. subminuta; (AH–AQ) Humidophila contenta. Scale bars: Light micrographs 10 μm; (E,F,M,N,S,X,AC,AH–AJ) 5 μm; and (R) 3 μm.

Figure 4.

Overview of the most abundant taxa (part 2). LM (A–C,E–O,S–Y,AA–AC) and SEM (D,P–R,Z). (A–D) Mastogloia sp; (E,F) Gomphonema naviculoides; (G,H) Gomphonema cf. pantropicum; (I,J) Gomphonema brasiliense; (K) Gyrosigma cf. obtusatum; (L–U) Nitzschia semirobusta; (V–Y) Nitzschia amphibia; (Z,AB) Encyonema sp.; (AC) Seminavis cf. strigose. Scale bars: Light micrographs 10 μm; (D,P–R,Z) 5 μm.

Table 2.

Diatom taxa from three different habitat types at BCNM: S = submerged parts of Annona glabra trunks, A = aerial parts of Annona glabra trunks, 50 cm above the water table, and F = forest understory in 1.4 m height. Sample number refers to Table 1, in which details on each sample are given. Species total represents the sum of all taxa of a given sample, while constancy indicates the number of the 18 samples where a particular taxon was found.

In a number of cases, we found up to eight taxa per genus like in Nitzschia, Eunotia, Achnanthidium, or Luticola, the dominant species being Humidophila contenta (Grunow) R.L.Lowe, Kociolek, Johansen, Van de Vijver, Lange-Bertalot & Kopalová, Nitzschia semirobusta Lange-Bertalot, and Achnanthidium cf. minutissimum.

We found differences in the species composition of the three microhabitat types, both in terms of the number and the identity of participating taxa. In the 17 samples with diatoms, species numbers ranged from 1 to 31 species. Numbers differed significantly among microhabitats (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05). Samples of the submersed portion of Annona trunks, which tended to have the highest abundances of diatoms (Table 1), also had the highest species numbers, with up to 31 taxa (average: 14 species, Table 1 and Table 2). However, subsequent pairwise comparisons yielded significant differences in species numbers only between inundated Annona trunks and the forest understory, where we found, on average, just three species per sample (Dunn test, p < 0.01). The species numbers of the aerial portions of Annona trunks (average of eight species) did not differ significantly from those in the other two microhabitats (Dunn test, p = 0.06 in both cases).

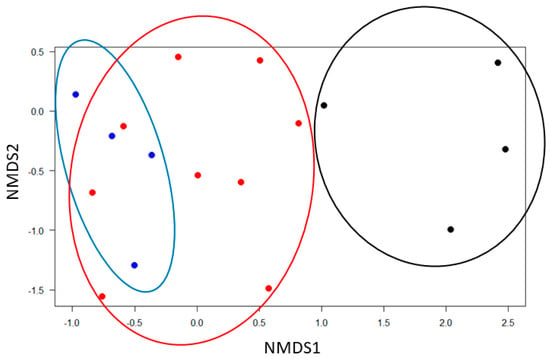

The epiphytic forest understory microhabitat stood out in terms of low species numbers, but also in terms of species identity—most of the 12 species belonged to just two genera, Orthoseira and Luticola, with three and four taxa, respectively, and these taxa were rarely found in the two other habitats. The result of the NMDS (Figure 5) clearly shows that differences are not limited to these two taxa: the diatom assemblages in the understory were taxonomically quite distinct, while there was relatively little difference between the assemblages on the two microhabitat types of Annona glabra.

Figure 5.

NMDS ordinations of the diatom assemblages on 17 bark samples. Stress = 0.08. The three microhabitat types in the Barro Colorado Nature Monument are inundated trunk bases of Annona glabra (blue), aerial trunk of Annona glabra (red), and bark samples from the forest understory at c. 1.4 m (black).

4. Discussion

We present clear evidence that diatoms can be quite common occupants of tree bark in the understory of the tropical lowland forest of Barro Colorado Island and are not restricted to special tree microhabitats like epiphytic mosses or lichens or phytotelms, which one would deduce from previous publications (e.g., [25,26,52,53]). However, the almost complete lack of diatoms in the few samples from greater heights in the forest suggests that these epiphytic occurrences are limited to the forest understory, which is probably related to the steep gradient in air humidity from the forest floor to the outermost canopy [54].

Our samples reveal rich diatom assemblages, with 70 taxa belonging to 28 genera identified across a relatively small set of 20 samples. However, the numbers of species from the two aerial microhabitats are somewhat smaller, totalling 54 taxa in 26 genera. Still, this level of diversity on aerial bark surfaces alone is remarkable, especially in comparison to the very limited number of aerial diatoms previously reported from tropical forests. Many of the taxa detected belong to groups typically associated with periodically desiccating or acidic subaerial habitats, such as Humidophila, Eunotia, Luticola, Achnanthidium, and Nitzschia [11,55,56,57,58,59,60], suggesting that the bark microbiome of tropical lowland forests may harbour a distinct and largely unexplored diatom flora.

The Barro Colorado Nature Monument is situated in the Panama Canal watershed. Soler B., Pérez Aparicio, Aguilar, and Batista [23] published a detailed study of the diatom flora of this limnic system. Considering that their work is based on several years of field work, while our sampling effort was much more limited, it is surprising that we found many species that were not mentioned in that monograph (Table 2, e.g., Humidophila contenta, Luticola hustedii Levkov, Metzeltin & A.Pavlov or Nitzschia semirobusta Lange-Bertalot). We even found members of several genera in our samples that were not listed there, e.g., species in the genera Adlafia, Encyonopsis, Staurosira, or Ulnaria (Table 2). Particularly noteworthy is the absence of Humidophila contenta, the species with the highest constancy of all taxa in our study, which was, e.g., found in four of six samples in the forest understory. Clearly, the list provided by Soler B., Pérez Aparicio, Aguilar, and Batista [23] is far from complete, and any detailed comparison would therefore be premature. However, we can nevertheless start to address the question of the source populations of the observed epiphytic diatoms. The more frequently encountered species in our study, such as Humidophila contenta, Nitzschia semirobusta, Encyonopsis cf. subminuta, and Achnanthidium cf. minutissimum, are also taxa known for their ecological tolerance to fluctuating moisture, rapid colonisation, and persistence on unstable or seasonally dry substrates [11,14,56,57,61]. Their repeated appearance across multiple microhabitats, including submerged bark, above-water bark, and—at least in the case of Humidophila contenta—even bark in the forest understory, suggests that some aerial diatoms may function as ecological generalists capable of exploiting a wide range of intermittently wet tree-associated surfaces [61,62]. Our samples were collected in the dry season, when the lake level is much lower than in the rainy season [34]. Thus, diatoms found on the sampled aerial parts of Annona glabra stems could simply be remnants of the inundation during the last rainy season. However, since we always collected above the lichen lines, which indicate the highest water level due to the susceptibility of crustose lichens to inundation [35], this explanation can be rejected. We note the suggestive overlap in community composition between the two microhabitats (Figure 5), but whether this reflects active vertical movements or rather passive transport of diatoms originating from the lake remains to be shown.

The aerial occurrences in the forest understory demand a different explanation. In the literature, passive transport by wind has been discussed for a long time to explain the occurrence of diatoms in aerial habitats by, e.g., Sharma et al. [63], Hustedt [64], and Bock [13], but such a scenario only seems plausible for trees in open situations such as the aerial parts of Annona glabra. We sampled in the understory of a dense lowland forest, at a distance of about 500–1000 m from the lake shore. Thus, we argue that passive transport can hardly explain our observations, particularly when considering that we found densities up to almost 1000 frustules mm−2 (Table 1). The same argument against passive transport has already been used by Beger [65], and our reasoning is also supported by the results of a recent study from Southern France, in which the authors concluded that the impact of wind is restricted to the immediate vicinity of lakes and rivers, while passive transport of diatoms into the forest interior was nil [66]. Thus, the most likely source could be subaerial diatoms from the forest floor. This remains to be tested, but the fact that most of the species on bark in the understory were not found in the other two microhabitats (Table 2, Figure 5) close to the lake is in line with this reasoning. In any case, independent of the issue of the origin, we provide direct evidence that there are live diatoms on bark, even in the dry season. The large proportion of empty frustules testifies that abiotic conditions in this aerial habitat are demanding for diatoms, at least during the dry season. This agrees with other reports that subaerial diatom assemblages often contain only a small fraction of living cells and may be active only intermittently [11,56]. As a result, distinguishing between actively growing diatoms and passively deposited material remains challenging without time-resolved sampling. Nevertheless, the presence of living cells, even during the dry season, indicates that bark surfaces can serve as active habitats rather than acting merely as traps for wind-transported diatoms.

How is the occurrence of diatoms on bark related to the distribution of diatoms at large in the landscape? Clearly, we are largely ignorant of the communities of subaerial (soil) diatoms in this and other tropical forests, and in spite of a published monograph [23], our knowledge of the diatom community in the Panama watershed is also far from complete, as concluded above. What seems necessary is a systematic sampling of the diatom assemblages from possible sources (forest floor, creeks on Barro Colorado Island, and Lake Gatun) and the lower portions of tree trunks to the lower parts of the forest canopy. Within this gradient, there are numerous types of tree-related microhabitats (TREMs, [67]), from pure bark to epiphytic mosses, epiphytic lichens, and epiphytic vascular plants, but also water-filled tree holes [68], which all need to be considered. Among epiphytes, tank bromeliads would deserve particular attention as a micro-limnic system that is a key habitat for numerous groups of organisms from unicellular organisms like diatoms or ciliates to vertebrates (e.g., [69,70,71,72,73]). However, if the goal is to fully understand this system of aerial diatoms, we have to study whether diatoms on bark are only transiting to more suitable microhabitats, e.g., from soil to moss cushions, or between mosses and lichens, or whether there are indeed viable diatom populations on pure bark. Moreover, in a seasonal climate such as that of central Panama, one would also expect variation in distributional patterns between the dry and the wet season. Thus, sampling should cover this seasonal variation. A limitation of our study is that LM preparations were not quantified, and therefore relative abundances of live cells of individual taxa could not be assessed. SEM counts provided robust total cell densities, but in most cases, these counts cannot be assigned to taxa without additional image analysis. Future studies should incorporate quantitative LM or high-resolution SEM imaging to determine dominance patterns within samples and to evaluate how community composition shifts between wet and dry periods. Such data would be essential for distinguishing stable bark-associated assemblages from groups of transient colonisers.

The idea for the present study originated from a chance observation of diatoms on bark in a study on orchid roots. Although the present work is still limited in scope, our data provide sufficient evidence that aerial occurrences of diatoms are not restricted to epiphytic moss cushions or lichens, as suggested by previous reports, but diatoms may be quite common on tree bark in the wet tropics, albeit with few species. The number of taxa with sometimes surprisingly high abundances documented here, despite the limited sampling effort and a rather qualitative-empirical approach, underscores how little is known about these communities and highlights the potential for future taxonomic and ecological work. This exciting finding should now be the starting point for interesting follow-up projects that investigate specific questions, such as (1) how the composition of the aerial diatom community is related to that of potential donor communities like the soil or water bodies, i.e., creeks and lakes; (2) whether there is vertical stratification and if it differs with the season; and (3) whether there are differences in the diatom communities associated with different TREMs. Far from representing a biological oddity, aerial diatoms may constitute a hitherto unacknowledged part of epiphyte communities in tropical forest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z., J.Z., N.A., and J.Y.L.T.; methodology, G.Z., J.Z., N.A., and J.Y.L.T.; validation, G.Z., J.Z., N.A., and J.Y.L.T.; formal analysis, G.Z.; data curation, J.Y.L.T. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.Z., J.Z., N.A., and J.Y.L.T.; visualisation, G.Z., N.A., and J.Y.L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Material was exported under permit PA01ARB005-202. Thanks to Ina Becker (Oldenburg) and Juliane Bettig, Ariadni Giannopouloun, Josefa Bo Rolfing (Berlin) for technical help. We acknowledge the Electron and Light Microscopy Service Unit, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, for the use of the imaging facilities and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) for funding the instrument JEOL IT800 scanning electron microscope project number INST 184/235-1 FUGG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Graham, L.F.; Graham, J.M.; Wilcox, L.W. Algae; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neustupa, J.; Škaloud, P. Diversity of subaerial algae and cyanobacteria growing on bark and wood in the lowland tropical forests of Singapore. Plant Ecol. Evol. 2010, 143, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustupa, J.; Škaloud, P. Diversity of subaerial algae and cyanobacteria on tree bark in tropical mountain habitats. Biol. Futur. 2008, 63, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandkar, J.T.; Kamble, A.K. Freshwater, terrestrial and sub-aerial algal flora of Bhuleshwar and Baneshwar temples. Ann. Biol. 2020, 36, 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, P.A.; Schlichting, H.E., Jr. A floristic survey of corticolous subaerial algae in North Carolina. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 1973, 89, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Saraphol, S.; Rindi, F.; Sanevas, N. Diversity of epiphytic subaerial algal communities in bangkok, thailand, and their potential bioindicator with air pollution. Diversity 2024, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, U.; Kusber, W.-H.; Jahn, R. The diatom flora of Berlin (Germany): A spotlight on some documented taxa as a case study on historical biodiversity. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Diatom Symposium, Międzyzdroje, Poland, 2–7 September 2004; Biopress Limited: Bristol, UK, 2006; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kharkongor, D.; Ramanujam, P. Diversity and species composition of subaerial algal communities in forested areas of Meghalaya, India. Int. J. Biodivers. 2014, 2014, 456202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zheng, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, X. Diatom composition of epiphytic bryophytes on trees and its ecological distribution in Wuhan City. Chin. J. Ecol. 2016, 35, 2983–2990. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, N.B.; Bondugula, V.; Kola, S.G.; Gajula, R.G. Study of algal flora of algae-moss association on selected tree species existing in forest regions of Vikarabad and Nizamabad in Telangana State, India. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 22, 507–510. [Google Scholar]

- Round, F.E.; Crawford, R.M.; Mann, D.G. The Diatoms: Biology & Morphology of the Genera; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 747. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, X.; Fritz, S.C. Diatom diversity and biogeography across tropical South America. In Neotropical Diversification: Patterns and Processes; Rull, V., Carnaval, A.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, W. Diatomeen extrem trockener Standorte. Nova Hedwig. 1963, 5, 199–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rybak, M.; Czarnota, P.; Noga, T. Study of terrestrial diatoms in corticolous assemblages from deciduous trees in Central Europe with descriptions of two new Luticola DG Mann taxa. PhytoKeys 2023, 221, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štifterová, A.; Neustupa, J. Community structure of corticolous microalgae within a single forest stand: Evaluating the effects of bark surface pH and tree species. Fottea 2015, 15, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudes, D.; Benzing, D.H. Nitrogen fixation in association with Ecuadorian bromeliads. J. Trop. Ecol. 1991, 7, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.J.P.; Branco, L.H.Z.; Moura, C.W.D. Cyanobacteria from bromeliad phytotelmata: New records, morphological diversity, and ecological aspects from northeastern Brazil. Nova Hedwig. 2019, 108, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra, L.T.d. Algumas diatomáceas encontradas em Bromeliáceas, Brasil. Memórias Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1971, 69, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, K.M.S.d.; Tavares, A.R.; Vercellino, L.S.; Ferragut, C. Biomass and abiotic variables change in phytotelmic environment in the tank-bromeliad Nidularium longiflorum Ule in tropical forest. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2019, 31, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laessle, A.M. A micro-limnological study of Jamaican bromeliads. Ecology 1961, 42, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, N.; Espinosa, H.; Soler, B.A. Estudio florístico de las diatomeas epilíticas en el río Fonseca, provincia de Chiriquí, Panamá. Centros 2015, 4, 188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Metzeltin, D.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Tropische Diatomeen in Sudamerika: Tropical Diatoms of South America I; Koeltz Scientific: Königstein, Germany, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, B.A.; Pérez Aparicio, M.I.; Aguilar, E.; Batista, I.V. Diatomeas del Canal de Panamá: Bioindicadores y Otros Estudios Pioneros; Autoridad del Canal de Panamá—Universidad de Panamá: Panama City, Panama, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, M.; Fischer-Pardow, A. Nonvascular epiphytes: Functions and risks at the tree canopy. In Treetops at Risk; Lowman, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, M.; Lange-Bertalot, H.; Büdel, B. Diatoms living inside the thallus of the green algal lichen Coenogonium linkii in neotropical lowland rain forests. J. Phycol. 2004, 40, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, J.W. The ecology of an elfin forest in Puerto Rico, 14. The algae of Pico del Oeste. J. Arnold Arbor. 1971, 52, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkwitz, R.; Krieger, W. Zur Ökologie der Pflanzenwelt, insbesondere der Algen, des Vulkans Pangerango in West-Java. Berichte Der Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1936, 54, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, J.; Zotz, G.; Einzmann, H.J.R. Smoothing out the misconceptions of the role of bark roughness in vascular epiphyte attachment. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.; Zotz, G.; Gorb, S.N.; Einzmann, H.J.R. Getting a grip on the adhesion mechanism of epiphytic orchids—Evidence from histology and Cryo-SEM. Front. For. Glob. Change—For. Ecophysiol. 2021, 4, 764357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdridge, L.R.; Grenke, W.C.; Hatheway, W.H.; Liang, T.; Tosi, J.A., Jr. Forest Environments in Tropical Life Zones: A Pilot Study; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1971; p. 747. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, S. Yearly Reports Barro Colorado Island. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Dataset. Available online: https://smithsonian.figshare.com/articles/dataset/Yearly_Reports_Barro_Colorado_Island/11799111/3 (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Croat, T.B. Flora of Barro Colorado Island; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1978; p. 943. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, E.G., Jr.; Rand, A.S.; Windsor, D.M. (Eds.) The Ecology of a Tropical Forest. Seasonal Rhythms and Long-Term Changes; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1982; p. 468. [Google Scholar]

- Einzmann, H.J.R.; Zotz, G. A grey-green band around BCI—The population structure of the inundation-tolerant tree Annona glabra. In the First 100 Years of Research on Barro Colorado Island—Plant and Ecosystem Science; Muller-Landau, H.C., Wright, S.J., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 665–670. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, M.E., Jr. The lichen line and high water levels in a freshwater stream in Florida. Bryologist 1984, 87, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutowski, A.; Stelzer, D.; Schönfelder, I.; Müller, A. Verfahrensanleitung für die ökologische Bewertung von Fließgewässern zur Umsetzung der EG-Wasserrahmenrichtlinie: Makrophyten und Phytobenthos. Phylib Fließgewässer: 2024. Available online: https://gewaesser-bewertung-berechnung.de/files/downloads/phylib/LFP_O623_A3_Verfahrensanleitung%20Phylib_FG_2024.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Hofmann, G.; Werum, M.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Diatomeen im Süßwasser-Benthos von Mitteleuropa. In Bestimmungsflora Kieselalgen für die Ökologische Praxis. Über 700 der Häufigsten Arten und Ihre Ökologie; A.R.G. Gantner: Rugell, Liechtenstein, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, Bacillariophyceae. 2/2: Bacillariaceae, Epithemiaceae, Surirellaceae; Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, Bacillariophyceae. 2/3: Centrales, Fragilariaceae, Eunotiaceae; Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, Bacillariophyceae. 2/1: Naviculaceae; Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, Bacillariophyceae. 2/4: Achnanthaceae (Ergänzter Nachdruck); Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Bertalot, H.; Metzeltin, D. Oligotrophie-Indikatoren. 800 Taxa Repräsentativ für Drei Diverse Seen-Typen; Koeltz Scientific: Königstein, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Levkov, Z.; Lange-Bertalot, H.; Mitić-Kopanja, D.; Reichardt, E. The diatom genus Gomphonema from the Republic of Macedonia. In Diatoms of Europe; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; Koeltz Botanical: Oberreifenberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Metzeltin, D.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Tropical Diatoms of South America I: About 700 Predominantly Rarely Known or New Taxa Representative of the Neotropical Flora; Koeltz Scientific: Königstein, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Metzeltin, D.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Tropical Diatoms of South America II: Special Remarks on Biogeography Disjunction; Koeltz Scientific: Königstein, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Novais, M.H.; Juettner, I.; Van de Vijver, B.; Morais, M.M.; Hoffmann, L.; Ector, L. Morphological variability within the Achnanthidium minutissimum species complex (Bacillariophyta): Comparison between the type material of Achnanthes minutissima and related taxa, and new freshwater Achnanthidium species from Portugal. Phytotaxa 2015, 224, 101–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, E. Zur Revision der Gattung Gomphonema; A.R.G. Gantner: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Levkov, Z. Amphora sensu lato. In Diatoms of Europe; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; A.R.G. Gantner: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Bertalot, H. Navicula sensu stricto, 10 genera separated from Navicula sensu lato, Frustulia. In Diatoms of Europe; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; A.R.G. Gantner: Ruggell, Liechtenstein, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.F.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Sólymos, P.; Henry, M.; Stevens, H.; et al. Package ‘vegan’. Community Ecology Package. R Cran Repository. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Arguelles, E.D.L.R. Phytotelm algae of Pandan [Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.] (Pandanaceae) leaf axil tanks from Laguna (Philippines). Trop. Nat. Hist. 2021, 21, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.T.X. Algas (Chlorophyta, Bacillariophyta, Euglenophyta) de ambientes fitotelmatas bromelícolas de uma área de Restinga de Guarajuba, município de Camaçari, Bahia. An. Dos Semin. De Iniciação Científica 2019, 23, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K.; Bogusch, W.; Zotz, G. The role of the regeneration niche for the vertical stratification of vascular epiphytes. J. Trop. Ecol. 2013, 29, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, J.R. Cryptogamic crusts of semiarid and arid lands of North America. J. Phycol. 1993, 28, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, J.R. Diatoms of aerial habitats. In The Diatoms: Applications for the Environmental and Earth Sciences; Smol, J.P., Stoermer, E.F., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, R.L.; Kociolek, P.; Johansen, J.R.; Vijver, B.V.D.; Lange-Bertalot, H.; Kopalová, K. Humidophila gen. nov., a new genus for a group of diatoms (Bacillariophyta) formerly within the genus Diadesmis: Species from Hawai’i, including one new species. Diatom Res. 2014, 29, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkov, Z.; Metzeltin, D.; Pavlov, A. Luticola and Luticolopsis. In Diatoms of Europe; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; Koeltz Scientific: Königstein, Germany, 2013; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver, B.; De Haan, M.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Revision of the genus Eunotia (Bacillariophyta) in the Antarctic Region. Plant Ecol. Evol. 2014, 147, 256–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.; Noga, T.; Zubel, R. The aerophytic diatom assemblages developed on mosses covering the bark of Populus alba L. J. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange-Bertalot, H.; Hofmann, G.; Werum, M.; Cantonati, M.; Kelly, M.G. Freshwater Benthic Diatoms of Central Europe: Over 800 Common Species Used in Ecological Assessment; Koeltz Botanical Books: Schmitten-Oberreifenberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 942. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, D.; Carmona, J.; Jahn, R.; Zimmermann, J.; Abarca, N. Epilithic diatom communities of selected streams from the Lerma-Chapala Basin, Central Mexico, with the description of two new species. PhytoKeys 2017, 88, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Rai, A.K.; Singh, S.; Brown, R.M., Jr. Airborne algae: Their present status and relevance. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustedt, F. Aërophile Diatomeen in der nordwestdeutschen Flora. Berichte Der Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1942, 60, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Beger, H. Beitrage zur Ökologie und Soziologie der luftlebigen (atmophytischen) Kieselalgen. Berichte Der Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1927, 45, 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, J.; Coste, C.; Garrigue, J. Première contribution à l’étude des diatomées de la réserve naturelle nationale de la forêt de la Massane (Pyrénées-Orientales). Carnets Nat. 2022, 9, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nußer, R.; Bianco, G.; Kraus, D.; Larrieu, L.; Feldhaar, H.; Schleuning, M.; Mueller, J. An adapted typology of tree-related microhabitats including tropical forests. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanoviak, S.P. Community structure in water-filled tree holes of Panama: Effects of hole height and size. Selbyana 1999, 20, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Malkmus, R.; Dehling, J.M. Anuran amphibians of Borneo as phytotelm breeders—A synopsis. Herpetozoa 2008, 20, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zotz, G.; Traunspurger, W. What’s in the tank? Nematodes and other major components of the meiofauna of bromeliad phytotelms in lowland Panama. BMC Ecol. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janetzky, W.; Martínez Arbizu, P.; Reid, J.W. Attheyella (Canthosella) mervini sp. n. (Canthocamptidae, Harpacticoida) from Jamaican bromeliads. Hydrobiologia 1996, 339, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foissner, W.; Struder-Kypke, M.; van der Staay, G.W.M.; Moon-van der Staay, S.Y.; Hackstein, J.H.P. Endemic ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) from tank bromeliads (Bromeliaceae): A combined morphological, molecular, and ecological study. Eur. J. Protistol. 2003, 39, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.F.; Sant’Anna, C.L.; Azevedo, M.T.d.P.; Komarek, J.; Kastovsky, J.; Sulek, J.; Lorenzi, A.S. The cyanobacterial genus Brasilonema, gen. nov., a molecular and phenotypic evaluation. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).