Abstract

Mitochondrial genomes provide powerful insights into insect phylogeny and molecular evolution, aiding in the clarification of complex taxonomic relationships. Within the swallowtail butterfly subfamily Parnassiinae (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae), an insect group of significant environmental and economic importance, essential aspects of phylogenetic positioning remain unresolved. This study presents the first sequencing and annotation of the complete mitogenome for Parnassius stubbendorfii from two geographically distinct populations in Gansu Province, China. Both mitogenomes are circular, double-stranded molecules, measuring 15,377 bp and 15,348 bp in length, each encoding 37 standard mitochondrial genes: 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA genes, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and an A + T-rich control region. The gene arrangement is highly conserved and typical of Lepidoptera. Phylogenetic analyses based on both the 13 PCGs and the complete set of 37 mitochondrial genes supported the placement of Parnassiinae as a subfamily within Papilionidae, with Parnassini and Zerynthini identified as two distinct clades within Parnassiinae. Notably, tree topologies derived from the 13 PCGs alone exhibited slight deviations from those based on the full mitogenome, underscoring the need for expanded mitogenomic data across Papilionidae to further refine evolutionary relationships.

1. Introduction

Habitat fragmentation, urbanization, pollutant emissions, and climate change are a few facets and drivers of the ongoing age-defining human impacts on Earth [1,2,3]. These global trends contribute to a range of consequences, from increased extreme weather events to species decline and extinction [2,4,5]. Insects, as the most diverse animal group, are particularly revealing in this context, especially flagship species for conservation like bees and butterflies [6,7]. While bees have received significant attention due to issues like colony collapse and declines, often associated with their vulnerability to ongoing environmental changes [8,9], including increased pesticide use [10,11], butterflies are often overlooked despite their substantial ecological roles.

Butterflies and moths comprise the second largest order of insects, Lepidoptera, with about 180,000 species across 126 families and 46 superfamilies worldwide. They hold intrinsic conservation value and also contribute to ecosystem health as bioindicators, as well as being longstanding model organisms in biological research [12,13,14]. Economically, they impact agriculture as pests, support eco-tourism, and provide biologically active compounds (e.g., pheromones and deterrents) with potential economic applications. Among butterflies, swallowtails (family Papilionidae) are of particular conservation interest due to their ecological significance. With an origin in the Late Cretaceous (64–86 Ma) following the rise of angiosperms, Papilionidae includes about 570 species globally and displays remarkable diversity among phytophagous insects [15]. While some authors recognize three subfamilies, namely, Baroniinae, Parnassiinae, and Papilioninae, Nieukerken et al. [16] have suggested that only Parnassiinae and Papilioninae are valid subfamilies within Papilionidae.

The subfamily Parnassiinae predominantly inhabits Central Asia and high mountain regions of the Tibetan Plateau. The genus Parnassius, which contains approximately 50 species, is especially adapted to alpine or subalpine meadows in Central Asia, the Himalayas, and western China, as well as species found in Europe such as Parnassius apollo [17,18,19,20]. Characterized by strong cold resistance and slow movement, these butterflies are vulnerable to local extinction due to climate change and human-driven habitat alterations [12,13,14]. Some species, like Parnassius nomion (the Nomion Apollo) and P. bremeri (the red-spotted Apollo), are listed as endangered in China and Korea due to their sensitivity to environmental changes [21,22,23].

While phylogenetic studies on Papilionidae are abundant, relationships among species remain contentious, with inconsistencies across findings [15,24,25]. Unresolved issues include the taxonomic classification and monophyly of Parnassiinae. For instance, the inclusion of Zerynthiini and Parnassiini within Parnassiinae is disputed [26,27,28,29], with some researchers suggesting that Parnassiinae may form an independent family separate from Papilionidae [30]. However, some studies have argued that Parnassiinae is not monophyletic based on morphological analyses [27], while molecular studies, such as those using the nad5 gene, have further complicated these relationships by suggesting different groupings within the subfamily [28,29].

Morphological characteristics alone have proven insufficient for resolving the phylogeny of Parnassiinae, driving the need for molecular approaches [31,32]. The mitochondrial genome has been widely utilized in systematics and evolutionary studies due to its compact structure, matrilineal inheritance, lack of recombination, and relatively high mutation rate compared to nuclear genomes in insects [26,33]. These features are common among insect mitochondrial genomes, but not universal across all animal mitochondrial genomes. Notably, some insects, such as human lice, possess atypical mitochondrial genome structures [34]. Despite these exceptions, mitochondrial DNA remains a valuable tool for reconstructing phylogenies, as demonstrated in recent studies on Lepidoptera lineages [33,35]. However, existing mitogenome data are sparse, with only 29 mitochondrial sequences for Parnassius species in GenBank, limiting comprehensive phylogenetic analysis [25,36,37].

In this study, we sequenced and annotated the mitogenome of P. stubbendorfii from two regions of Gansu Province, China, adding to the available mitochondrial data for Parnassius. Our results, combined with 163 mitogenomic sequences from Papilionoidea species (Appendix A Table A1), provide a more comprehensive dataset to clarify Parnassiinae’s taxonomic status and monophyly.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Identification, and DNA Extraction

Adult specimens of P. stubbendorfii were collected from Yongjing County, Lanzhou City, Gansu Province (103°28′58″ E, 35°95′83″ N), China, and Hezheng County, Linxia City, Gansu Province (103°41′31″ E, 35°25′75″ N), China. Specimens were preserved in 100% ethanol at −20 °C for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Universal Genomic DNA Kit (CoWin Biosciences, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Voucher specimens were deposited in the College of Plant Protection, Gansu Agriculture University, China (voucher number: GSAU2254, GSAU2261).

2.2. Mitogenome Sequencing Assembly, Annotation, and Sequence Analysis

The mitochondrial genomes of two P. stubbendorfii individuals were sequenced using high-throughput sequencing technology. Whole Genome Shotgun sequencing libraries were prepared with the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) from extracted total DNAs and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform using a 250 bp paired-end strategy. FastQC v. 0.12.0 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc, accessed on 13 September 2022), was used for quality control (average Q20 > 95%, average Q30 > 87%). De novo assembly was conducted with A5-miseq v. 20150522 [38] and SPAdes v. 3.9.0 [39]. Contig and scaffold sequences generated during assembly were used for sequencing depth analysis and gap filling. BLAST searches were used to confirm mitochondrial sequences, and MUMmer v. 3.1 [40] was employed to establish positional relationships with contig sequences.

The mitochondrial genome was annotated using the MITOS webserver based on the invertebrate genetic code [41], with manual verification against published complete mitogenomes of Parnassiinae. Gene boundaries were confirmed using MEGA X [42] by comparison to other complete mitochondrial genomes of Parnassiinae, and reading frames of the 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs) were verified. The tRNAs were identified with tRNAscan-SE v. 1.21 [43], and secondary structures of the rRNAs were drawn by the XRNA v. 2.0 (http://rna.ucsc.edu/rnacenter/xrna/xrna.html, accessed on 25 October 2024), and inferred from P. apollo [44] and P. epaphus [45]. Base composition and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) were calculated with MEGA X. CodonW v. 1.4.2 [46] was used for effective codon usage statistics (Nc). The Nc values are commonly regarded as ranging between 20 and 61 and are negatively correlated with codon usage bias [47]. AT-skew and GC-skew were calculated using formulas AT-skew = (A − T)/(A + T) and GC-skew = (G − C)/(G + C) to assess chain asymmetry [48]. Nucleotide diversity and the ratio of nonsynonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitutions were calculated for the 13 PCGs of Parnassiinae using DnaSP v. 5.0 [49].

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

Phylogenetic analysis of the two newly sequenced mitogenomes was conducted using mitochondrial genomes from 163 Papilionoidea species (Table A1). Phylogenetic analyses were performed with two datasets: one containing 13 PCGs and another with 37 mitochondrial genes. The 13 PCGs were aligned individually using the TranslatorX v. 15.0 [50] with codon-based multiple alignments, while alignments of the two rRNAs and 22 tRNAs were conducted using the Q-INS-i algorithm on the MAFFT v. 7.520 [51]. MEGA X was used for alignment verification.

Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was performed in IQ-TREE v. 2.0.4 [52] with models selected by ModelFinder [53]. The alignment was partitioned in the same manner as for the Bayesian analysis, and the models were applied to each partitioned dataset. Bootstrap support (BS) was assessed with 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was conducted in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 [54], using partitioned models generated by PartitionFinder v. 2.1.1 [55]. For the BI analysis, three independent runs with four chains (three heated, one cold) were conducted for 7,000,000 generations, with sampling every 100 generations. Convergence was verified by estimated sample size (ESS) values exceeding 200 and potential scale reduction factor (PSRF) values close to 1.0 [54]. The first 25% of samples were discarded as burn-in, and posterior probabilities (PP) were generated from a 50% majority-rule consensus tree.

3. Results

3.1. General Features of the Sequenced Mitogenomes

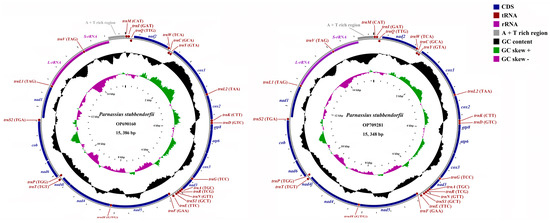

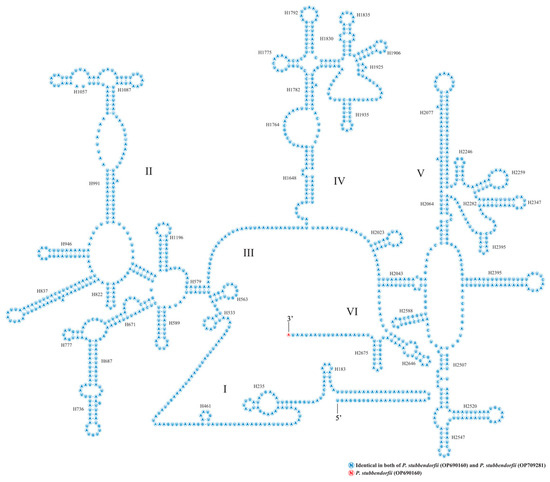

The two newly sequenced mitochondrial genomes of P. stubbendorfii are circular, double-stranded molecules with sizes of 15,386 bp (GenBank accession No. OP690160) and 15,348 bp (GenBank accession No. OP709281) (Figure 1, Table A2). These lengths fall within the published range for Parnassiinae, from 14,557 bp for P. nomion (KJ867422) to 16,028 bp for Luehdorfia chinensis (NC027672). The length variation between the two genomes is primarily due to differences in the AT-rich region, which is 487 bp in OP690160 and 457 bp in OP709281. Both mitogenomes contain 37 typical mitochondrial genes: 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 2 ribosomal RNA genes (rRNAs), 22 transfer RNA genes (tRNAs), and an AT-rich control region. Of these, 14 genes are located on the minority strand (4 PCGs, 2 rRNAs, and 8 tRNAs).

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial genome map of P. stubbendorfii (OP690160 and OP709281).

The nucleotide composition of OP690160 is 40.42% A, 40.85% T, 11.19% C, and 7.53% G, while that of OP709281 is 40.64% A, 40.92% T, 11.02% C, and 7.42% G (Table A3), both showing significant A + T bias (81.27% for OP690160 and 81.56% for OP709281). The AT-skew and GC-skew for OP690160 are −0.00529 and −0.19551, and for OP709281 are −0.00342 and −0.19523 (Table A3), respectively.

3.2. Protein-Coding Genes

The total lengths of the 13 PCGs in OP690160 and OP709281 are 11,197 bp and 11,203 bp, encoding 3707 and 3709 amino acids, with A + T contents of 80.29% and 80.30% (Table A3), respectively. These PCGs exhibit the lowest A + T content compared to other genes in the mitogenomes. AT-skews of −0.00511 and −0.00548 and GC-skews of −0.17707 and −0.17766 are observed for OP690160 and OP709281, respectively (Table A3). All PCGs use the typical start codon ATN except for cox1 and cox2, which starts with CGA (Table A2). Twelve PCGs terminate with the common stop codons TAA or TAG (with TAG in nad2 and TAA in others), while cox1 and cox2 end with an incomplete T codon (Table A2).

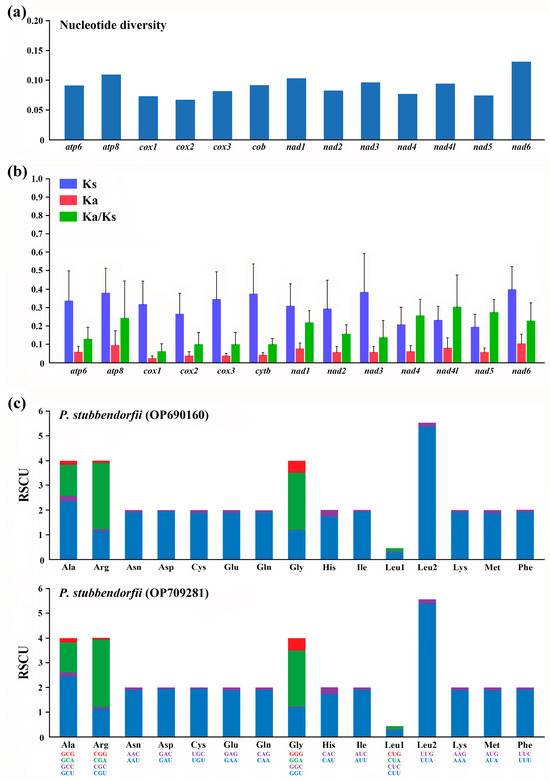

Nucleotide diversity and Ka/Ks ratios of all available Parnassiinae PCGs were analyzed to explore evolutionary patterns (Figure 2). nad6 has the highest nucleotide diversity, while cox2 has the lowest. The highest Ka/Ks ratio is observed for nad4l, and the lowest for cox1, with all PCGs showing values below 1, indicating purifying selection. These results suggest that atp8 experiences the least selection pressure and exhibits the highest evolutionary rate.

Figure 2.

(a) Nucleotide diversity of PCGs from 16 reported and 2 newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes. (b) The ratio of Ka/Ks of PCGs from 16 reported and 2 newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes of this study. (c) The relative synonymous codon usages (RSCU) of PCGs from two newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes of this study. Codon families are listed below the x-axis.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) analysis indicates conserved codon usage in both mitogenomes (Figure 2). Four codons (CUG, CCG, ACG, AGC) are absent in both mitogenomes. Nc values, used to assess codon usage bias, are 30.56 for OP690160 and 30.37 for OP709281, indicating similar codon bias.

3.3. Transfer and Ribosomal RNA Genes

Both mitogenomes contain the standard set of 22 tRNAs, totaling 1455 bp (Table A3). The A + T content of tRNAs is 81.51% in OP690160 and 81.72% in OP709281, which is lower than that of rRNAs and the AT-rich region, but higher than that of PCGs (Table A3). The AT-skews for tRNAs are −0.00847 and −0.00930 and GC-skews are −0.13791 and −0.12801 for OP690160 and OP709281, respectively (Table A3).

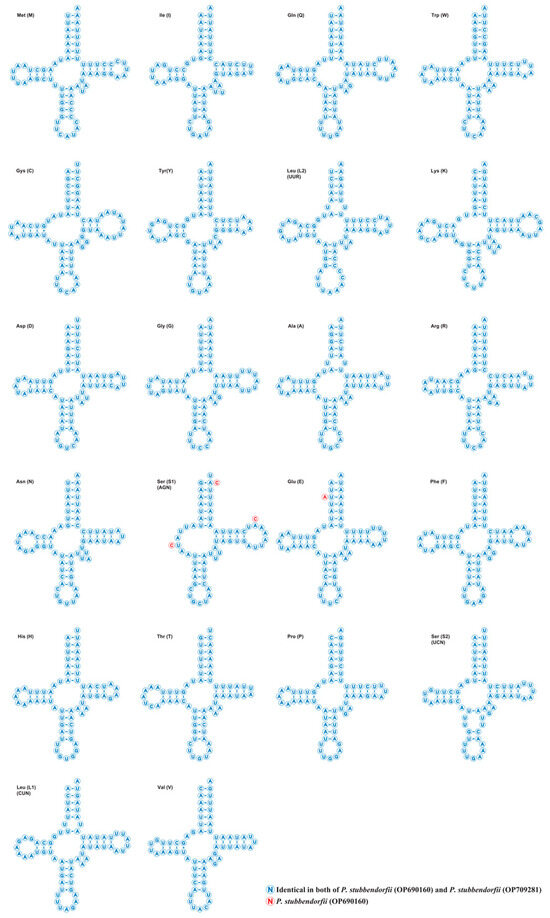

Each tRNA, except trnS1 (AGN), exhibits typical cloverleaf secondary structures, while trnS1 lacks the dihydrouridine (DHU) arm (Figure 3). Seventeen unmatched base pairs are present, including 16 G-U pairs. Additionally, OP690160 contains an A-A pair, and OP709281 a G-A pair.

Figure 3.

The putative secondary structures of tRNAs from the two newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes. The tRNAs are labeled with the abbreviations of their corresponding amino acids. Dashes represent Watson–Crick base pairs; dots indicate wobble GU pairs; and other non-canonical pairs are not labeled.

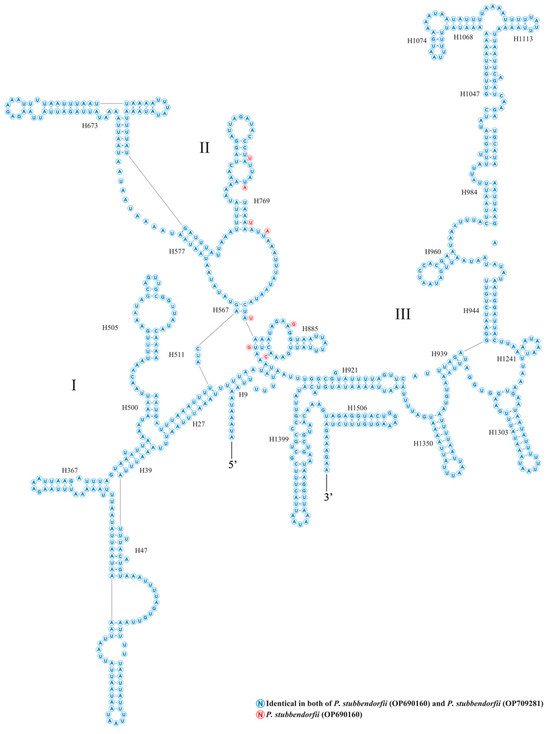

The two rRNA genes, rrnS and rrnL, are located between trnV and the AT-rich region, and between trnL1 and trnV, respectively (Figure 4 and Figure 5, Table A2). rrnS measures 779 bp in OP690160 and 778 bp in OP709281, while rrnL is 1354 bp in both genomes. The A + T content is 84.43% for OP690160 and 84.62% for OP709281. Both rrnS and rrnL exhibit high A + T content compared to PCGs and tRNAs, with AT-skews of −0.00391 and −0.00449 and GC-skews of −0.34961 and −0.34763 for OP690160 and OP709281, respectively (Table A3).

Figure 4.

The putative secondary structures of rrnS from two newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes of this study. Roman numerals indicate the conserved domain structure.

Figure 5.

The putative secondary structures of rrnL from the two newly sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes of this study. Roman numerals denote the conserved domain structure.

3.4. Gene Overlapping and Intergenic Regions

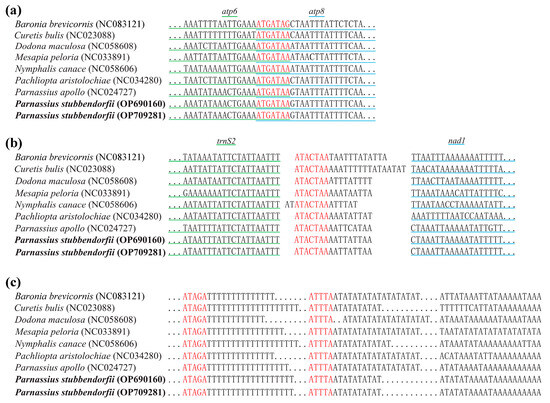

Both mitogenomes feature 11 overlapping and 14 intergenic spacer regions. Overlapping spacers range from 1 to 8 bp, and intergenic spacers range from 1 to 47 bp (Table A2). Notably, an “ATGATAA” motif is located between atp8 and atp6, and an “ATACTAA” motif between trnS2 and nad1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A comparison of the overlapping and intergenic regions among seven species from seven families of Papilionoidea and two sequenced Parnassiinae mitogenomes. The conserved regions are highlighted in red, and the two newly sequenced mitogenomes are shown in bold. (a) The overlapping region between atp6 and atp8. (b) The intergenic region between trnS2 and nad1. (c) Schematic illustration of the A + T-rich region. The dots represent omitted nucleotide bases, with the number of dots not corresponding to the exact number of nucleotides in the corresponding section.

The AT-rich region measures 487 bp in OP690160 and 457 bp in OP709281, with A + T contents of 87.07% and 95.40%, respectively. The AT-skews are 0.01413 and 0.07799, and GC-skews are −0.20650 and −0.23747 for OP690160 and OP709281, respectively (Table A3). Conserved sequences like “ATAGA” and a poly-T structure are also present in this region (Figure 6).

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

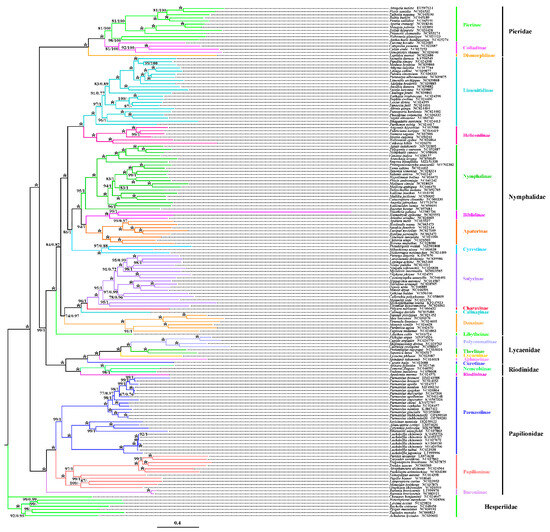

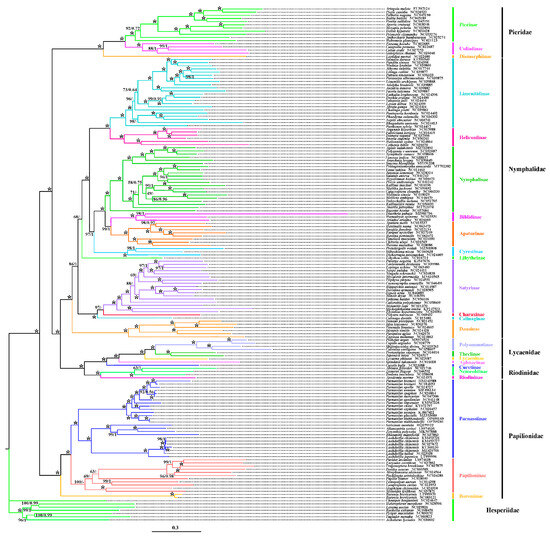

A phylogenetic analysis was conducted using 156 mitochondrial genome sequences of Papilionoidea (including five families) as the ingroup, with seven Hesperiidae sequences as the outgroup, combined with the newly sequenced mitogenomes. Trees were constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) based on 13 PCGs and 37 mitochondrial genes (Table A4 and Table A5).

The analyses reveal two main clades: the first is composed of four families: Pieridae + (Nymphalidae + (Riodinidae + Lycaenidae)), and the second includes Parnassiinae and Papilioninae of the Papilionidae. Both analyses support the monophyly of each family and indicate Parnassiinae as a subfamily within Papilionidae. The results further suggest Parnassini and Zerynthini as sister tribes within Parnassiinae.

Differences emerged between the 13 PCGs and the 37 gene dataset analyses, with Libytheinae clustering variably within Nymphalidae subfamilies. Using 13 PCGs, Libytheinae formed a sister group with several Nymphalidae subfamilies but displayed closer relationships with other lineages in the 37-gene dataset analysis (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of Papilionoidea was conducted based on 13 PCGs inferred from ML and BI analyses. The numbers separated by “/” on each node represent the support values corresponding to ML/bootstrap and BI/posterior probabilities. The two newly sequenced mitogenomes are highlighted in bold. A dash “-” indicates an unrecovered node based on BI analysis, while an asterisk “*” signifies posterior probabilities of 100/1.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic analysis of Papilionoidea was performed based on 37 mitochondrial gene sequences inferred from ML and BI analyses. The numbers separated by “/” on each node represent the posterior probabilities corresponding to the ML/BI. The two newly sequenced mitogenomes are highlighted in bold. A dash “-” indicates unrecovered node based on BI analysis, while an asterisk “*” indicates posterior probabilities of 100/1.

4. Discussion

In this study, we sequenced two mitochondrial genomes of P. stubbendorfii. The nucleotide composition showed a significant A + T bias of 81.27% for P. stubbendorfii (OP690160) and 81.56% for P. stubbendorfii (OP709281) (Table A3), which is characteristic of insect mitochondrial genomes [56]. The AT- and GC-skews of both genomes fall within the range observed in other Papilionidae species [26,57]. Interestingly, both cox1 genes use the CGA start codon, while other protein-coding genes (PCGs) employ the standard ATN start codon. This CGA start codon has been frequently reported in lepidopteran mitogenomes [34]. Additionally, as seen in other Lepidoptera, the cox1 and cox2 gene uses a partial stop codon, likely due to post-transcriptional mRNA modifications [58].

In line with other Lepidopterans, all tRNAs in these genomes display the typical cloverleaf secondary structures, except for trnS1 (AGN), which lacks the dihydrouridine (DHU) arm [47]. The “ATGATAA” motif, conserved across lepidopteran mitochondrial genomes, is found in the intergenic spacer between atp8 and atp6 [34]. Furthermore, the intergenic spacer between trnS2 and nad1 contains the conserved “ATACTAA” motif, known as a potential binding site for transcription termination in Papilionidae [26,59]. Another common motif, “ATAGA”, is observed within the AT-rich region [60].

We performed phylogenetic analyses using 156 mitochondrial genomes sequences from Papilionoidea families as the ingroup and 7 mitochondrial genome sequences of Hesperiidae as the outgroup, alongside the two newly sequenced P. stubbendorfii mitogenomes. Our analysis, based on 13 PCGs and 37 mitochondrial genes, clarified the relationships within Papilionoidea as Papilionidae + (Pieridae + (Nymphalidae + (Riodinidae + Lycaenidae))). Notably, our study challenges the classification of Parnassiinae as a separate family within Papilionidae and supports the notion that Parnassini and Zerynthini formed a sister clade in Parnassiinae [26,38,61]. Our findings also refute the argument for Parnassiinae as an independent family separate from Parnassiinae [26,62] and strongly support the monophyly of Parnassiinae, contrary to previous studies suggesting its non-monophyly [63,64].

However, some differences emerged between the phylogenies derived from 13 PCGs and those based on 37 mitochondrial genes. Using 13 PCGs, Libytheinae clustered with other Nymphalidae subfamilies, whereas the analysis based on 37 mitochondrial genes showed Libytheinae forming a sister clade with several other subfamilies before linking with Satyrinae, Charaxinae, Calinaginae, and Danainae. This discrepancy may stem from the limited representation of mitogenomes per genus. Thus, expanding the dataset with additional mitogenomes could provide a more robust phylogenetic resolution. Currently, only 29 mitochondrial genome sequences of Parnassius species are available on GenBank, which is insufficient for comprehensive analyses. Future studies should consider integrating expanded mitogenomic and nuclear gene data for greater accuracy in Parnassiinae phylogeny.

Author Contributions

S.S. and Y.D. conceived, designed, and supervised the study. L.S., X.C. and X.L. conducted the study. L.S. drafted the manuscript and analyzed the data. S.S., R.N.C.G., Y.D. and J.Z. arranged valuable comments, engaged in critical editing, and proofread the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program: Inter-Governmental Science and Technology Innovation Program, No. 2022YFE0115200; Insect Resources Investigation of Liancheng National Nature Reserve of Gansu Province, GSAU-JSFW-2022-082; and Program of Introducing Talents to Chinese Universities, 111 Program No. D20023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession no. OP690160 (accessed on 19 October 2022) and OP709281 (accessed on 21 October 2022). The associated BioProject, SRA and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA979184, SAMN35570448, and SAMN35570449.

Acknowledgments

We would like to show our gratitude to the associates Yang Zhao-Fu (Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi) and Yang Ming-Sheng (Zhoukou Normal College, Zhoukou, Henan) for their reading the early draft and providing us with many valuable suggestions in experiment design.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The Papilionoidea species used in this study.

Table A1.

The Papilionoidea species used in this study.

| Superfamily | Family | Subfamily | Species | GenBank Accession No. | Genome Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papilionoidea | Lycaenidae | Aphnaeinae | Spindasis takanonis | NC016018 | 15,349 |

| Curetinae | Curetis bulis | NC023088 | 15,162 | ||

| Lycaeninae | Lycaena phlaeas | NC023087 | 15,280 | ||

| Polyommatinae | Caerulea coeligena | NC058607 | 15,164 | ||

| Cupido argiades | NC020779 | 15,330 | |||

| Plebejus argus | MN974526 | 15,426 | |||

| Shijimiaeoides divina | NC029763 | 15,259 | |||

| Theclinae | Japonica lutea | NC026517 | 15,225 | ||

| Protantigius superans | NC016016 | 15,248 | |||

| Nymphalidae | Apaturinae | Apatura metis | NC015537 | 15,236 | |

| Chitoria ulupi | NC026569 | 15,279 | |||

| Euripus nyctelius | NC027109 | 15,417 | |||

| Herona marathus | NC028086 | 15,487 | |||

| Hestina persimilis | NC063472 | 15,252 | |||

| Hestinalis nama | NC063473 | 15,208 | |||

| Sasakia funebris | NC022134 | 15,233 | |||

| Timelaea maculata | NC021090 | 15,178 | |||

| Biblidinae | Ariadne ariadne | NC026069 | 15,179 | ||

| Diaethria gabaza | MZ981736 | 15,156 | |||

| Hamadryas epinome | NC025551 | 15,207 | |||

| Calinaginae | Calinaga davidis | NC015480 | 15,267 | ||

| Charaxinae | Polyura narcaeus | NC060432 | 15,319 | ||

| Cyrestinae | Dichorragia nesimachus | NC024409 | 15,355 | ||

| Pseudergolis wedah | MZ501808 | 15,079 | |||

| Stibochiona nicea | NC060638 | 15,298 | |||

| Danainae | Danaus plexippus | NC021452 | 15,314 | ||

| Euploea midamus | NC024863 | 15,187 | |||

| Idea leuconoe | NC030376 | 15,278 | |||

| Ideopsis similis | NC024428 | 15,200 | |||

| Parantica aglea | NC042670 | 15,219 | |||

| Tirumala limniace | NC024605 | 15,285 | |||

| Heliconiinae | Argynnis hyperbius | NC015988 | 15,156 | ||

| Cethosia biblis | NC026070 | 15,211 | |||

| Damora sagana | NC037006 | 15,151 | |||

| Fabriciana nerippe | NC016419 | 15,140 | |||

| Heliconius cydno | NC024864 | 15,367 | |||

| Issoria eugenia | NC050261 | 15,206 | |||

| Libytheinae | Libythea celtis | NC016724 | 15,164 | ||

| Limenitidinae | Abrota ganga | NC024404 | 15,356 | ||

| Adelpha bredowii | NC039885 | 15,187 | |||

| Athyma sulpitia | NC017744 | 15,268 | |||

| Auzakia danava | NC039882 | 15,367 | |||

| Bhagadatta austenia | NC024413 | 15,615 | |||

| Chalinga pratti | NC039861 | 15,290 | |||

| Dophla evelina | NC024400 | 15,320 | |||

| Euthalia irrubescens | NC024396 | 15,365 | |||

| Lexias dirtea | NC024399 | 15,250 | |||

| Limenitis archippus | NC039868 | 15,220 | |||

| Litinga cottini | NC039877 | 15,205 | |||

| Moduza lysanias | NC039860 | 15,238 | |||

| Neptis obscurior | NC060741 | 15,172 | |||

| Pandita sinope | NC024398 | 15,257 | |||

| Pantoporia hordonia | NC024402 | 15,603 | |||

| Parasarpa albomaculata | NC039875 | 15,272 | |||

| Parthenos sylvia | NC024417 | 15,249 | |||

| Patsuia sinensium | NC036333 | 15,192 | |||

| Phaedyma columella | NC036332 | 15,197 | |||

| Sumalia daraxa | KF590549 | 15,173 | |||

| Tacola larymna | NC039887 | 15,503 | |||

| Tanaecia julii | NC024416 | 15,316 | |||

| Nymphalinae | Aglais ladakensis | MN732892 | 15,222 | ||

| Anartia jatrophae | MT712074 | 15,297 | |||

| Araschnia levana | NC050649 | 15,207 | |||

| Baeotus beotus | NC057684 | 15,131 | |||

| Catacroptera cloanthe | NC060330 | 15,204 | |||

| Doleschallia melana | NC052705 | 15,269 | |||

| Hypolimnas bolina | NC026072 | 15,260 | |||

| Junonia lemonias | NC028324 | 15,230 | |||

| Kallima inachus | NC016196 | 15,183 | |||

| Kallimoides rumia | NC050691 | 15,234 | |||

| Melitaea cinxia | NC018029 | 15,170 | |||

| Mallika jacksoni | NC050692 | 15,193 | |||

| Mellicta ambigua | NC046470 | 15,205 | |||

| Nymphalis canace | NC058606 | 15,216 | |||

| Polygonia c-aureum | NC052687 | 15,208 | |||

| Precis andremiaja | NC041242 | 15,239 | |||

| Protogoniomorpha anacardii | MT702382 | 15,220 | |||

| Salamis anteva | NC041243 | 15,201 | |||

| Smyrna blomfildia | MZ151338 | 15,149 | |||

| Vanessa indica | NC038157 | 15,191 | |||

| Yoma sabina | NC024403 | 15,330 | |||

| Satyrinae | Callerebia polyphemus | NC058609 | 15,156 | ||

| Coenonympha amaryllis | NC046491 | 15,125 | |||

| Davidina armandi | NC028505 | 15,214 | |||

| Elymnias hypermnestra | NC026061 | 15,167 | |||

| Hipparchia autonoe | NC014587 | 15,489 | |||

| Lasiommata deidamia | NC039986 | 15,244 | |||

| Lopinga achine | NC063460 | 15,284 | |||

| Melanitis leda | NC021370 | 15,122 | |||

| Minois dryas | NC046591 | 15,195 | |||

| Mycalesis intermedia | MN610565 | 15,386 | |||

| Neope pulaha | NC024411 | 15,209 | |||

| Ninguta schrenckii | NC026838 | 15,261 | |||

| Oeneis urda | NC046889 | 15,248 | |||

| Pararge aegeria | KJ547676 | 15,240 | |||

| Stichophthalma louisa | KP247523 | 15,721 | |||

| Triphysa phryne | NC024551 | 15,143 | |||

| Ypthima baldus | NC056106 | 15,304 | |||

| Baroniinae | Baronia brevicornis | LT999970 | 14,918 | ||

| Baronia brevicornis | NC083121 | 15,173 | |||

| Papilionidae | Papilioninae | Atrophaneura alcinous | NC024564 | 15,266 | |

| Euryades corethrus | NC037862 | 15,133 | |||

| Graphium chironides | NC026910 | 15,235 | |||

| Lamproptera curius | NC023953 | 15,277 | |||

| Mimoides lysithous | NC037871 | 15,038 | |||

| Pachliopta aristolochiae | NC034280 | 15,232 | |||

| Papilio bianor | NC018040 | 15,340 | |||

| Parides ascanius | LS974638 | 15,212 | |||

| Teinopalpus aureus | NC014398 | 15,242 | |||

| Troides aeacus | NC060569 | 15,224 | |||

| Trogonoptera brookiana | NC037875 | 15,005 | |||

| Parnassiinae | Allancastria cerisyi | LS974636 | 15,279 | ||

| Bhutanitis mansfieldi | NC037863 | 14,994 | |||

| Luehdorfia chinensis | MZ420706 | 15,443 | |||

| Luehdorfia chinensis | KU360130 | 15,550 | |||

| Luehdorfia chinensis | KM453726 | 15,580 | |||

| Luehdorfia chinensis | KM453727 | 15,580 | |||

| Luehdorfia chinensis | NC027672 | 16,028 | |||

| Luehdorfia japonica | LT999996 | 15,347 | |||

| Luehdorfia taibai | NC023938 | 15,553 | |||

| Parnassius apollo | NC024727 | 15,404 | |||

| Parnassius apollonius | NC041148 | 15,381 | |||

| Parnassius bremeri | NC014053 | 15,389 | |||

| Parnassius bremeri | HM243588 | 15,390 | |||

| Parnassius cephalus | NC026457 | 15,343 | |||

| Parnassius choui | KY072797 | 15,367 | |||

| Parnassius epaphus | NC026864 | 15,458 | |||

| Parnassius glacialis | MZ353680 | 15,353 | |||

| Parnassius imperator | KM507326 | 15,424 | |||

| Parnassius mercurius | NC047306 | 15,372 | |||

| Parnassius nomion | MF496134 | 15,362 | |||

| Parnassius nomion | KJ867422 | 14,557 | |||

| Parnassius stubbendorfii | OP690160 | 15,386 | |||

| Parnassius stubbendorfii | OP709281 | 15,348 | |||

| Sericinus montela | HQ259122 | 15,242 | |||

| Zerynthia polyxena | MK507888 | 15,092 | |||

| Pieridae | Coliadinae | Catopsilia pomona | NC022687 | 15,142 | |

| Colias erate | NC027253 | 15,184 | |||

| Eurema hecabe | NC022685 | 15,160 | |||

| Gonepteryx rhamni | NC026046 | 15,203 | |||

| Dismorphiinae | Leptidea morsei | NC022686 | 15,122 | ||

| Pierinae | Anthocharis bambusarum | NC025274 | 15,180 | ||

| Aporia crataegi | NC018346 | 15,140 | |||

| Artogeia melete | EU597124 | 15,140 | |||

| Baltia butleri | NC045189 | 15,124 | |||

| Delias hyparete | NC020428 | 15,186 | |||

| Hebomoia glaucippe | NC021123 | 15,701 | |||

| Mesapia peloria | NC033891 | 15,159 | |||

| Pieris canidia | NC026532 | 15,153 | |||

| Pontia callidice | NC045191 | 15,109 | |||

| Prioneris clemanthe | NC053274 | 15,131 | |||

| Talbotia nagana | NC045190 | 15,155 | |||

| Riodinidae | Nemeobiinae | Abisara fylloides | NC021746 | 15,301 | |

| Dodona maculosa | NC058608 | 15,486 | |||

| Zemeros flegyas | NC046592 | 15,219 | |||

| Riodininae | Apodemia mormo | NC024571 | 15,262 | ||

| Outgroup | |||||

| Hesperioidea | Hesperiidae | Coeliadinae | Choaspes benjaminii | NC024647 | 15,300 |

| Eudaminae | Achalarus lyciades | NC030602 | 15,612 | ||

| Hesperiinae | Lerema accius | NC029826 | 15,338 | ||

| Heteropterinae | Heteropterus morpheus | NC028506 | 15,769 | ||

| Pyrginae | Pyrgus maculatus | NC030192 | 15,346 | ||

| Tagiadinae | Tagiades menaka | NC060823 | 15,294 | ||

| Trapezitinae | Rachelia extrusus | NC048456 | 16,114 |

Note: The two newly sequenced mitogenomes are emphasized in bold.

Table A2.

The two newly determined Parnassiinae mitogenomes.

Table A2.

The two newly determined Parnassiinae mitogenomes.

| Feature | Strand | Location | Start Codon | Stop Codon | Anticodon | Intergenic Nucleotides | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | ||||||

| trnM | J | 1/1 | 68/68 | CAT/CAT | 0/0 | ||

| trnI | J | 69/69 | 132/132 | GAT/GAT | −3/−3 | ||

| trnQ | N | 130/130 | 198/198 | TTG/TTG | 47/47 | ||

| nad2 | J | 246/246 | 1259/1259 | ATC/ATC | TAA/TAA | −1/−1 | |

| trnW | J | 1259/1259 | 1324/1324 | TCA/TCA | −8/−8 | ||

| trnC | N | 1317/1317 | 1383/1383 | GCA/GCA | 3/3 | ||

| trnY | N | 1387/1387 | 1450/1450 | GTA/GTA | 3/3 | ||

| cox1 | J | 1454/1454 | 2984/2984 | CGA/CGA | T/T | 0/0 | |

| trnL2 | J | 2985/2985 | 3051/3051 | TAA/TAA | 0/0 | ||

| cox2 | J | 3052/3052 | 3733/3733 | ATG/ATG | T/T | 0/0 | |

| trnK | J | 3734/3734 | 3804/3804 | CTT/CTT | −1/−1 | ||

| trnD | J | 3804/3804 | 3870/3870 | GTC/GTC | 0/0 | ||

| atp8 | J | 3871/3871 | 4035/4035 | ATT/ATT | TAA/TAA | −7/−7 | |

| atp6 | J | 4029/4029 | 4706/4706 | ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA | −1/−1 | |

| cox3 | J | 4706/4706 | 5494/5494 | ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA | 3/3 | |

| trnG | J | 5498/5498 | 5564/5564 | TCC/TCC | 0/0 | ||

| nad3 | J | 5565/5565 | 5918/5918 | ATT/ATT | TAA/TAA | −1/−1 | |

| trnA | J | 5918/5918 | 5983/5983 | TGC/TGC | −1/−1 | ||

| trnR | J | 5983/5983 | 6048/6048 | TCG/TCG | 2/2 | ||

| trnN | J | 6051/6051 | 6116/6116 | GTT/GTT | 3/3 | ||

| trnS1 | J | 6120/6120 | 6180/6180 | GCT/GCT | 39/35 | ||

| trnE | J | 6220/6216 | 6285/6281 | TTC/TTC | −2/−2 | ||

| trnF | N | 6284/6280 | 6350/6346 | GAA/GAA | 1/1 | ||

| nad5 | N | 6352/6348 | 8085/8081 | ATT/ATT | TAA/TAA | 0/0 | |

| trnH | N | 8086/8082 | 8149/8145 | GTG/GTG | −1/−1 | ||

| nad4 | N | 8149/8145 | 9489/9485 | ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA | 0/0 | |

| nad4l | N | 9490/9486 | 9780/9776 | ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA | 2/2 | |

| trnT | J | 9783/9779 | 9848/9844 | TGT/TGT | 0/0 | ||

| trnP | N | 9849/9845 | 9913/9909 | TGG/TGG | 2/2 | ||

| nad6 | J | 9916/9912 | 10,446/10,442 | ATT/ATT | TAA/TAA | 13/13 | |

| cob | J | 10,460/10,456 | 11,611/11,604 | ATG/ATG | TAA/TAA | 1/1 | |

| trnS2 | J | 11,613/11,606 | 11,678/11,671 | TGA/TGA | 16/16 | ||

| nad1 | N | 11,695/11,688 | 12,633/12,626 | ATG/ATG | TAG/TAG | 1/1 | |

| trnL1 | N | 12,635/12,628 | 12,702/12,695 | TAG/TAG | 0/0 | ||

| rrnL | N | 12,703/12,696 | 14,056/14,049 | 0/0 | |||

| trnV | N | 14,057/14,050 | 14,120/14,113 | TAC/TAC | 0/0 | ||

| rrnS | N | 14,121/14,114 | 14,899/14,891 | 0/0 | |||

| A + T-rich region | 14,900/14,892 | 15,386/15,348 | |||||

Note: “J” indicates the majority strand and “N” indicates the minority strand. The characters divided by “/” correspond to P. stubbendorfii (OP690160) and P. stubbendorfii (OP709281).

Table A3.

Nucleotide composition of the two newly determined Parnassiinae mitogenomes.

Table A3.

Nucleotide composition of the two newly determined Parnassiinae mitogenomes.

| Size (bp) | A (%) | T (%) | C (%) | G (%) | AT Content (%) | AT-Skew | GC-Skew | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | 15,377/ 15,348 | 40.42/ 40.64 | 40.85/ 40.92 | 11.19/ 11.02 | 7.53/ 7.42 | 81.27/ 81.56 | −0.00529/ −0.00342 | −0.19551/ −0.19523 |

| PCGs | 11,197/ 11,203 | 39.94/ 39.93 | 40.35/ 40.37 | 11.60/ 11.60 | 8.11/ 8.10 | 80.29/ 80.30 | −0.00511/ −0.00548 | −0.17707/ −0.17766 |

| tRNAs | 1455/ 1455 | 40.41/ 40.48 | 41.10/ 41.24 | 10.52/ 10.31 | 7.97/ 7.97 | 81.51/ 81.72 | −0.00847/ −0.00930 | −0.13791/ −0.12801 |

| rRNAs | 2133/ 2132 | 42.05/ 42.12 | 42.38/ 42.50 | 10.50/ 10.37 | 5.06/ 5.02 | 84.43/ 84.62 | −0.00391/ −0.00449 | −0.34961/ −0.34763 |

| A + T-rich region | 487/ 457 | 44.15/ 51.42 | 42.92/ 43.98 | 7.80/ 2.84 | 5.13/ 1.75 | 87.07/ 95.40 | 0.01413/ 0.07799 | −0.20650/ −0.23747 |

Note: The characters divided by “/” correspond to P. stubbendorfii (OP690160)/P. stubbendorfii (OP709281).

Table A4.

Partitioned models generated by PartionFinder version 2.1.1 for BI analysis.

Table A4.

Partitioned models generated by PartionFinder version 2.1.1 for BI analysis.

| Partitions | Models | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | GTR + I + G | c3p1; a6p1, cbp1 |

| P2 | GTR + I + G | c1p2, c2p2, a6p2 |

| P3 | TRN + G | a6p3, a8p3 |

| P4 | TIM + I + G | a8p1 |

| P5 | TIM + I + G | a8p2 |

| P6 | GTR + I + G | c2p1, c1p1 |

| P7 | GTR + G | c1p3 |

| P8 | GTR + I + G | c2p3, n6p3, c3p3, cbp3 |

| P9 | TVM + I + G | c3p2, cbp2 |

| P10 | TVM + I + G | n1p1, n5p1, n4p1, n4lp1 |

| P11 | GTR + I + G | n4lp2, n5p2, n4p2, n1p2 |

| P12 | TIM + I + G | n5pos3, n1p3, n4lp3 |

| P13 | GTR + I + G | n2p1 |

| P14 | TVM + I + G | n2p2, n6p2 |

| P15 | GTR + G | n2p3 |

| P16 | GTR + I + G | n3p1 |

| P17 | TVM + I + G | n3p2 |

| P18 | TRN + I + G | n3p3 |

| P19 | TIM + G | n4p3 |

| P20 | GTR + I + G | n6p1 |

| P21 | GTR + I + G | rrnS |

| P22 | GTR + I + G | rrnL |

| P23 | GTR + I + G | tRNAs |

Note: a6, a8, c1-c3, cb, and n1-n6 indicate the 13 PCGs; p1, p2, and p3 indicate the 1, 2, and 3 codon positions of each PCG.

Table A5.

Partitioned models generated by IQ-TREE 2.0.4 for ML analysis.

Table A5.

Partitioned models generated by IQ-TREE 2.0.4 for ML analysis.

| Partitions | Models | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | GTR + F + R6 | a6p1; c3p1; cbp1 |

| P2 | GTR + F + R4 | a6p2; c2p2; c3p2; cbp2 |

| P3 | TPM2 + F + R5 | a6p3 |

| P4 | TIM3 + F + I + G4 | a8p1 |

| P5 | TIM2 + F + I + G4 | a8p2; n3p1 |

| P6 | TPM2 + F + R5 | a8p3; n6p3 |

| P7 | GTR + F + R4 | c1p1; c2p1 |

| P8 | GTR + F + I + G4 | c1p2 |

| P9 | TVM + F + R7 | c1p3 |

| P10 | TIM + F + R7 | c2p3 |

| P11 | TIM2 + F + R7 | c3p3 |

| P12 | TN + F + R7 | cbp3; n3p3 |

| P13 | TVM + F + R6 | n1p1; n4p1; n4lp1; n5p1 |

| P14 | GTR + F + R5 | n1p2; n4p2; n4lp2; n5p2 |

| P15 | TIM + F + R8 | n1p3; n5p3 |

| P16 | GTR + F + R6 | n2p1; n6p1 |

| P17 | TVM + F + R4 | n2p2; n6p2 |

| P18 | GTR + F + R6 | n2p3 |

| P19 | GTR + F + I + G4 | n3p2 |

| P20 | TIM + F + R6 | n4p3; n4lp3; |

| P21 | GTR + F + R6 | rrnS |

| P22 | GTR + F + R6 | rrnL |

| P23 | GTR + F + R6 | tRNAs |

Note: a6, a8, c1-c3, cb, and n1-n6 indicate the 13 PCGs; p1, p2, and p3 indicate the 1, 2, and 3 codon positions of each PCG.

References

- Steffen, W.; Grinevald, J.; Crutzen, P.; McNeill, J. The Anthropocene: Conceptual and historical. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2011, 369, 842–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Williams, M.; Haywood, A.; Ellis, M. The Anthropocene: A new epoch of geological time? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2011, 369, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Teaching climate change in the Anthropocene: An integrative approach. Anthropocene 2020, 30, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Heinen, R.; Gols, R.; Thakur, M.P. Climate change-mediated temperature extremes and insects: From outbreaks to breakdowns. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 6685–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordblad, J. On the difference between anthropocene and climate change temporalities. Crit. Inq. 2021, 47, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, M.; Gurdak, D.J.; Ahmed, R.A.; Tamuly, J. Selecting flagships for invertebrate conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, P.; Barua, M. A Theory of Flagship Species Action. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, W.F.; Smagghe, G.; Guedes, R.N.C. Pesticides and reduced-risk insecticides, native bees and pantropical stingless bees: Pitfalls and perspectives. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, J.M.; Hogendoorn, K. How protection of honey bees can help and hinder bee conservation. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 46, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botina, L.L.; Bernardes, R.C.; Barbosa, W.F.; Lima, M.A.P.; Martins, G.F. Toxicological assessments of agrochemical effects on stingless bees (Apidae, Meliponini). MethodsX 2020, 7, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, R.C.; Botina, L.L.; Araújo, R.D.S.; Guedes, R.N.C. Artificial Intelligence-Aided Meta-Analysis of Toxicological Assessment of Agrochemicals in Bees. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 845608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLeo, J.M.F.; Nair, A.; Kardos, M.; Saastamoinen, M. Demography and environment modulate the effects of genetic diversity on extinction risk in a butterfly metapopulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2309455121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, G.; Ekroos, J.; Persson, A.S.; Pettersson, L.B.; Ockinger, E. Intensive management reduces butterfly diversity over time in urban green spaces. Urban. Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rija, A.A. Local habitat characteristics determine butterfly diversity and community structure in a threatened Kihansi gorge forest, Southern Udzungwa Mountains, Tanzania. Ecol. Process 2022, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condamine, F.L.; Nabholz, B.; Clamens, A.L.; Dupuis, J.R.; Sperling, F.A.H. Mitochondrial phylogenomics, the origin of swallowtail butterflies, and the impact of the number of clocks in Bayesian molecular dating. Syst. Entomol. 2018, 43, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieukerken, E.J.; Kaila, L.; Kitching, J.; Kristensen, N.P. Order Lepidoptera Linnaeus, 1758. In Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-Level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness; Zhang, Z.-Q., Ed.; Zootaxa—Magnolia Press: Auckland, New Zealand, 2011; Volume 3148, pp. 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xia, C.; Xia, X.; Chen, X.; Hao, J. The complete mitochondrial genome of Parnassius imperator (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae: Parnassiinae). Mitochondrial Dna 2016, 27, 1900–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omoto, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Shinkawa, T. Molecular systematics and evolution of the recently discovered “Parnassian” butterfly (Parnassius davydovi Churkin, 2006) and its allied species (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae). Gene 2009, 441, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todisco, V.; Gratton, P.; Zakharov, E.V.; Wheat, C.W.; Sbordoni, V.; Sperling, F.A.H. Mitochondrial phylogeography of the Holarctic Parnassius phoebus complex supports a recent refugial model for alpine butterflies. J. Biogeogr. 2012, 39, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, V.; Gratton, P.; Cesaroni, D.; Sbordoni, V. Phylogeography of Parnassius apollo: Hints on taxonomy and conservation of a vulnerable glacial butterfly invader. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 101, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, M.Z.; Mo, L.D. Competition index and application to conservation biology of Parnassius nomion. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2002, 10, 1695–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Minsu, K.; Junseok, L.; Cheolhak, K.; Seungsu, K.; Kyutek, P. Distributional data and ecological characteristics of Parnassius bremeri Bremer in Korea. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 2004, 4, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S. Illustrated Book of Korean Butterflies in Color; Kyo-Hak Pub. Co.: Seoul, Republioc of Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä, M.; Kaila, L.; Mutanen, M.; Pena, C.; Wahlberg, N. Cretaceous origin and repeated tertiary diversification of the redefined butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, A.Y.; Breinholt, J.W. Phylogenomics provides strong evidence for relationships of butterflies and moths. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20140970. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Yang, X.J.; Wu, J.; Zheng, S.Z.; Fang, J. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Papilio protenor (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae) and Implications for Papilionidae Taxonomy. J. Insect Sci. 2017, 6, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, C.L. Critical comments on the phylogenetic relationships within the family Papilionidae (Lepidoptera). Nota Lepid. 1993, 16, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, T.; Sasaki, G.; Takebe, H. Phylogeny of Japanese papilionid butterflies inferred from nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial ND5 gene. J. Mol. Evol. 1999, 48, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caterino, M.S.; Reed, R.D.; Kuo, M.M.; Sperling, A.F. A partitioned likelihood analysis of swallowtail butterfly phylogeny (Lepidoptera:Papilionidae). Syst. Biol. 2001, 1, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; Sinica, F. Lepidoptera; Papilionidae; Papilioninae, Zerynthiinae, Parnassiinae. In Fauna Sinica: Insecta; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2001; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Condamine, F.L.; Sperling, F.; Kergoat, G.J. Global biogeographical pattern of swallowtail diversification demonstrates alternative colonization routes in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Baek, J.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Jeong, H.C.; Kim, K.G.; Bae, C.H.; Han, Y.S.; Jin, B.R.; Kim, I. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitogenome of the red-spotted apollo butterfly, Parnassius bremeri (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) and comparison with other lepidopteran insects. Mol. Cells 2009, 28, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.J.; Zhang, X.; Duan, K. Complete mitochondrial genomes of two insular races of Pazala swordtails from Taiwan, China (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae: Graphium). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2021, 6, 1557–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, R.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Barker, S.C.; Herd, K. Evolution of extensively fragmented mitochondrial genomes in the lic of humans. Genome Biol. Evol. 2012, 4, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, M.L.; Chen, M.Y.; Wu, L.W. Two complete mitochondrial genomes of papilio butterflies obtained from historical specimens (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2021, 6, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Cong, Q.; Grishin, N.V. The complete mitochondrial genome of Papilio glaucus and its phylogenetic implications. Meta Gene 2015, 5, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breinholt, J.W.; Earl, C.; Lemmon, A.R.; Lemmon, E.M.; Xiao, L.; Kawahara, A.Y. Resolving relationships among the megadiverse butterflies and moths with a novel pipeline for anchored phylogenomics. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coil, D.; Jospin, G.; Darling, A.E. A5-miseq: An updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes illumina MiSeq data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, S.; Phillippy, A.; Delcher, A.L.; Smoot, M.; Shumway, M.; Antonescu, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, r12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Stadler, P. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, T.M.; Eddy, S.R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Huang, D.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhu, C.D.; Hao, J.S. The complete mitochondrial genome of the endangered Apollo butterfly, Parnassius apollo (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) and its comparison to other Papilionidae species. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2014, 17, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Xia, C.C.; Xia, X.Q.; Tao, R.S.; Hao, J.S. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Common Red Apollo, Parnassius epaphus (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae: Parnassiinae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2015, 18, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, J.F. Analysis of Codon Usage. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F. The effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene 1990, 87, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, N.T.; Kocher, T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, A.; Rafael, Z.; Telford, M.J. TranslatorX: Multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Mihn, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; Haeseler, A.V.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Hohna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution formolecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boore, J.L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.L.; Whiting, M.F. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within butterflies and moths. Gene 2008, 408, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.F.; Su, T.J.; Luo, A.R.; Zhu, C.D.; Wu, C.S. Characterization of the complete mitochondrion genome of diurnal moth Amata emma (Butler) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) and its phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenn, J.D.; Cameron, S.L.; Whiting, M.F. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the Mormon cricket (Anabrus simplex: Tettigoniidae: Orthoptera) and an analysis of control region variability. Insect Mol. Biol. 2007, 16, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taanman, J.W. The mitochondrial genome: Structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1410, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.L.; Zhu, B.Y. Atlas of Chinese Butterflies; Shanghai Far East Publisher: Shanghai, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.X.; Hewitt, G.M. Insect mitochondrial control region: A review of its structure, evolution and usefulness in evolutionary studies. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1997, 25, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.S. Phylogenetic studies in the Papilioninae (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1987, 186, 365–512. [Google Scholar]

- Caterino, M.S.; Sperling, F. Papilio phylogeny based on mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I and II genes. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 1999, 11, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).