Abstract

High-mountain lakes (HMLs) El Sol and La Luna are located 600 m apart in the crater of the Nevado de Toluca volcano, yet they display distinct differences in their morphometry and limnology. This study aimed to compare the zooplankton communities in these two lakes. El Sol harbored 31 zooplankton taxa, while La Luna had only 11. Notably, only four taxa were shared. The zooplankton abundance and biomass were lower than those in other tropical HMLs. La Luna’s zooplankton abundance was just 10% of El Sol’s, and its biomass was only 3%. Copepods dominated El Sol, while cladocerans dominated La Luna. The tropical seasonality (rainy and dry) was evident in meteorological and limnological variables but not in zooplankton; no seasonal patterns were observed in taxonomic richness, abundance, or biomass. No specific factors could explain the temporal dynamics in either lake. The extreme conditions in La Luna (e.g., lower pH and increased UV exposure) likely explained the differences between both lakes. The introduction of rainbow trout in El Sol during the 1950s may have also played a role.

1. Introduction

High-mountain lakes (HMLs) are significant ecological and hydrological features of the landscape. Their geographical isolation and altitude have resulted in distinctive environmental conditions (e.g., low temperatures, low nutrient levels, and high exposure to solar and ultraviolet radiation), making them extreme environments where only specially adapted organisms can survive [1,2].

HMLs are often located in regions of significant natural value, reflecting changes in their environment and the surrounding wilderness. These lakes share many common characteristics across different continents, making them some of the most comparable ecosystems in the world. As a result, research conducted in one location can provide valuable insights that apply to many other sites globally. Given the harsh environmental conditions the organisms face, high-mountain lakes can be classified as extreme ecosystems [1].

Only 10% of the global high-altitude environment is located in tropical regions [3]. Tropical HMLs are fascinating ecosystems that combine the characteristics of high-altitude and tropical climates. These lakes, situated at elevations typically above 3000 m, provide a unique environment where altitude interacts with tropical conditions (e.g., more variable in the short term, very pronounced diel differences in temperature and irradiance, much less cold), resulting in distinct ecological and hydrological features [3,4].

Löffler [4,5] was probably the first to extensively review the limnology of tropical HMLs and synthesize their main characteristics. Colonizing high-altitude lakes can be challenging, especially for larger organisms. Ascending into the mountains presents difficulties with transportation, the need to adapt to new and often harsher conditions, and a decrease in suitable habitats [6]. Tropical HMLs are at higher altitudes (3000 m) than temperate (1000 m) HMLs, making colonization even more challenging [3].

Zooplankton in HMLs are crucial to these fragile, anthropically easy-to-modify ecosystems, so they are considered sentinels of global and climate change (e.g., [2,7]). These organisms demonstrate remarkable adaptations to extreme conditions (e.g., pigmentation), and their ecological roles as primary consumers and nutrient recyclers highlight their importance in maintaining the balance of these exceptional environments. Herbivore communities in tropical lakes are typically similar in composition to temperate lakes. However, tropical lakes show a higher level of endemism among zooplankton, particularly in calanoid copepods, compared to phytoplankton. Additionally, specific essential taxa, such as Keratella tropica and Mesocyclops crassus, are uniquely found in tropical regions [8]. Moreover, recent information shows high biodiversity in tropical HMLs (e.g., [9]).

The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which features altitudes over 5000 m above sea level, lies on the northern edge of the tropical region in North America. The Xinantécatl (Nevado de Toluca) volcano, located 4200 m above sea level, contains two HMLs within its crater. These lakes, El Sol and La Luna, are the only HMLs found from Panama to the northern end of the Tropic of Cancer.

The present study addressed the knowledge gap regarding zooplankton in HMLs in tropical North America. This investigation aims to (a) record the seasonal dynamics of the zooplankton community composition, abundance, and biomass in Lakes El Sol and La Luna; (b) identify the principal differences between the zooplankton communities of the two lakes; (c) measure the seasonal dynamics of the leading environmental (meteorological and limnological) characteristics of both lakes; and (d) detect the critical environmental variables associated with the seasonality of the zooplankton communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

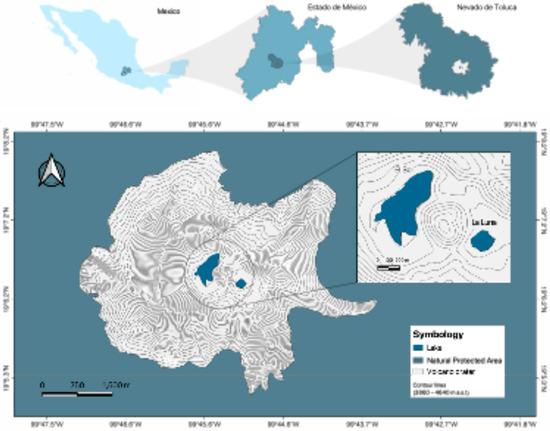

The Nevado de Toluca volcano is located at 19°09′ N and 99°45′ W, 23 km southwest of Toluca (Figure 1), with an elevation of 4680 m above sea level [10]. It is a Strombolian volcano comprising plagioclase feldspars, dacite, and andesite, with albite and anorthite chemical compositions [11]. The Nevado de Toluca crater is truncated and elliptical, with a 2 × 1.5 km diameter. Inside the crater, two lakes (El Sol and La Luna) are located ~200 m above the timberline (~3900–4060 m). They are separated by 600 m by a central dacitic dome called “El Ombligo” [10].

Figure 1.

Location of Lakes El Sol and La Luna, inside the crater of the Nevado de Toluca volcano, Estado de México, Mexico.

The climate in Nevado de Toluca is a cold alpine “páramo” type. The average annual temperature is 4.28 °C, ranging from 2.88 °C in February to 5.88 °C in April [12]. Annual precipitation is 1227 mm, while yearly evaporation is 971 mm (Station 15062, Nevado de Toluca, National Meteorological Service). Vegetation near the lakes is relatively scarce. It consists of mosses, grasses, and lichens, typical of the high tundra and the alpine zacatonal type [13].

At its maximum fill, El Sol has a surface area of 237,321 m2, a maximum depth of 15 m, and an average depth of 6 m, while La Luna has a surface area of 31,083 m2, a maximum depth of 10 m, and an average depth of 5 m. Both lakes are warm polymictic, oligotrophic, and transparent, and have low mineralization [12]. El Sol’s water type is Bic-Ca-Mg, while La Luna’s is mixed–mixed [14].

The first scientist to ascend the Nevado de Toluca was the baron and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who journeyed there in 1803 [15]. It was not until 169 years later that Heinz Löffler [16] published the first limnological observations of these HMLs in Mexico. Interestingly, he only mentioned one (“Toluca crater lake”) but not two lakes. The lake’s characteristics described in the paper matched La Luna. His route during the ascent likely led him to La Luna while overlooking the second lake, El Sol, “hidden” behind “El Ombligo”, the dacitic dome covering the volcano’s chimney at the central portion of the crater.

2.2. Field Sampling

Meteorological data for the sampling year, including monthly average air temperature and precipitation, were obtained from the automatic weather station (EMA) at Nevado de Toluca (SMN-CONAGUA, 2023). Monthly lake sampling was conducted at each lake’s central and deepest part from February 2022 to January 2023. The maximum depth (ZMAX) and Secchi disk depth (ZSD) were recorded on-site. In situ, measurements were taken for water temperature (T), dissolved oxygen concentration (DO), pH, electrical conductivity (K25), oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), and turbidity (Tur) using a calibrated Hydrolab model DS5 multiparametric probe, with a vertical resolution of 1 m. The samples for chlorophyll-a concentration (Chl-a) were analyzed according to the EPA method 445.0 (Turner Design TD-10 fluorometer) [17].

Water was collected in the pelagic zone with a 5 L Niskin bottle for zooplankton samples. Prospective sampling indicated that the zooplankton organisms were found near the bottom, so the annual monitoring sampling was conducted 1 m above the bottom of both lakes. For each lake, a 10 L water sample was taken. The 10 L sample was filtered in situ through a 54 µm mesh net, and all retained organisms were concentrated in 50 mL vials, which were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for further analysis. Additionally, a vertical drag (64 µm, 30 cm × 80 cm plankton net) was carried out along the water column to record those taxa that were not abundant. The drag was concentrated through a 60 µm mesh opening and further fixed with 4% formaldehyde.

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

We identified and counted all individuals concentrated in the 50 mL vials from each lake. The 50 mL samples were examined using a Sedgwick Rafter chamber under an optical microscope, with no sub-sampling (i.e., aliquot) methods.

We used specialized taxonomic keys to identify rotifers [18,19], cladocerans, and copepods [20,21,22,23,24]. Rotifer biomass was evaluated as a biovolume calculated based on the proposed geometric formulas [25]. Wet weight was estimated from the biovolume of each individual using a specific density of 1.0, and dry weight (DW) corresponds to 10% of wet weight [26]. The microcrustacean biomass was evaluated according to [27] and expressed as DW.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The environmental variables were transformed using the Z-score methodology for statistical analysis, while the logarithm of n + 1 was applied for abundance and biomass. This transformation allowed the data to be normally distributed. The rainy and dry seasons were established with cluster analysis (CA) using the Ward method with Euclidean distances. A CA was performed with the meteorological variables, and one was performed for each lake using its limnological variables. A Student t-test was conducted to assess whether there were differences in environmental variables and between different climatic seasons. In addition, a Student t-test was performed for independent samples to determine whether there were significant differences between the lakes. Pearson correlation was used to verify the relationship of environmental variables with biological ones. The statistical analyses were run using RStudio with the Vegan package. The Shannon–Wiener and Pielou evenness indexes were calculated with PAST4 [28].

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological Variables

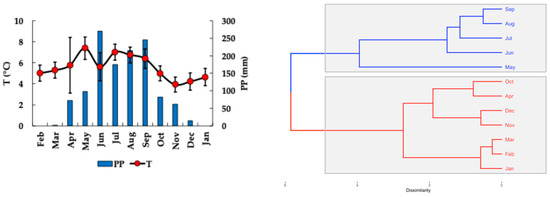

Monthly cumulative precipitation and average air temperatures during the study are displayed in Figure 2. Tropical seasonality is characterized by rainfall rather than temperature, as seen in temperate regions [28]. In this context, the rainy season, marked by precipitation levels exceeding ~100 mm/month, spans from May to September 2022, with an average rainfall of 201 ± 68 mm (Figure 2). Conversely, the dry season, which features precipitation below ~100 mm/month, occurs from February to May 2022 and again from October 2022 to January 2023, with an average rainfall of 33 ± 37 mm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Monthly accumulated precipitation (PP) (right) and average air temperature (T) (left), and cluster dendrogram of the meteorological data (blue = rainy season, red = dry season) in the Nevado de Toluca volcano (EMA weather station Nevado de Toluca: 19.12 N, −99.77 W, 4082 m a.s.l.).

Overall, the region receives a total of 1236 mm of rain annually. Of this, 81% (or 1003 mm) falls during the rainy season, while only 19% (or 232 mm) occurs in the dry season. Throughout the year, the driest months are from January to March, while June and September experience the highest rainfall.

At the latitude (19° N) and altitude (4200 m a.s.l.) where the lakes are located, there is a significant daily thermal variation in air temperature. This variation ranged from an absolute minimum temperature of −6.0 °C (average −2.1 °C ± 1.9 °C) to an absolute maximum of 18.0 °C (average 13.3 °C ± 1.0 °C). The average daily temperature oscillation was 15.36 °C ± 1.96 °C. The most significant daily thermal variations occurred in February, March, and May, as well as from October 2022 to January 2023. Conversely, the most minor daily thermal variations were observed in April and between June and September 2022. Generally, during the rainy season, the daily thermal oscillation decreases to below the average (15.36 °C); during the dry season, it increases to above the average.

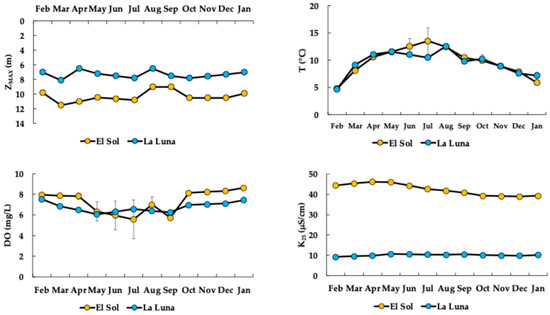

3.2. Limnological Variables

Table 1 provides the limnological variables of El Sol and La Luna (Appendix A, Table A1). The two lakes were significantly similar (p < 0.05) in T, DO, ORP, and Tur and were significantly different (p > 0.05) in ZMAX, K25, pH, and Chl-a. ZMAX, K25, pH, and Chl-a were higher in El Sol than in La Luna. The water transparency in both lakes was total, and the Secchi disk could be seen lying at the lakes’ bottoms. Consequently, from here on, ZSD will not be further discussed.

Table 1.

Environmental variables (X = average; s.d. = standard deviation; min = minimum; max = maximum) of Lakes El Sol and La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023. (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; K25 = electrical conductivity; DO = dissolved oxygen; pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration). [Green = significantly higher (p < 0.05); blue = significantly lower (p < 0.05); white = no significant differences (p > 0.05)].

El Sol is deeper than La Luna (Figure 3). The lakes’ water levels fluctuated by 2.5 m in El Sol and 1.6 m in La Luna, but neither lake dries out (i.e., astatic). The maximum water levels (ZMAX) were reached in March, while the minimum levels occurred in August. Both lakes were cold-water bodies with a substantial annual temperature variation of 9 and 8 °C in El Sol and La Luna, respectively; the highest temperatures occurred in the rainy season and the lowest in the dry season. The DO concentration was high in both lakes, around saturation; however, it was slightly lower in La Luna. The DO levels tended to decrease in the rainy season with higher temperatures and increase in the dry season with lower temperatures. The K25 value was also low in both lakes but significantly lower in La Luna—approximately a quarter of the value found in El Sol.

Figure 3.

Limnological variable dynamics in El Sol and La Luna (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; DO = dissolved oxygen concentration; K25 = electrical conductivity).

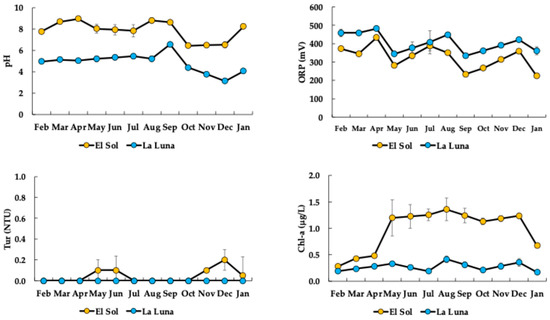

The two lakes exhibited different pH levels (Figure 4). El Sol consistently maintained a pH around neutrality, while La Luna remained in the acidic range throughout the year, reaching particularly low values in December (see Figure 4). The positive ORP values indicated elevated DO concentrations. Tur in both lakes remained very low throughout the year. Additionally, Chl-a concentrations were low in El Sol, reflecting oligotrophic conditions, whereas La Luna showed even lower concentrations characteristic of ultra-oligotrophy. From January to April, Chl-a in El Sol was 20% lower than during the rest of the year.

Figure 4.

Limnological variable dynamics in El Sol and La Luna (pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration).

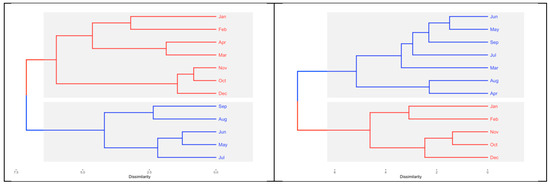

The limnological variable cluster analysis grouped the temporal variability into two periods (Figure 5). In El Sol, the first period comprised May to September (5 months), the rainy period. The second period included the dry period from October to April (7 months). In La Luna, the periods differed slightly. The first period comprised March to September (7 months), which corresponded to the rainy period plus one pre-rainy period; the second period incorporated the dry period (5 months) from October to February.

Figure 5.

Cluster analysis of the limnological data (blue = rainy season; red = dry season) of El Sol (left) and La Luna (right), Nevado de Toluca.

In El Sol (Table 2), the highest values for DO were observed during the dry season. In contrast, the highest T values occurred in the rainy season. The other variables were similar in both periods.

Table 2.

Environmental variables (X = average; s.d. = standard deviation) of Lake El Sol, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023 (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; K25 = electrical conductivity; DO = dissolved oxygen; pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration). (Cluster 1 = June–September; Cluster 2 = October–May.) [Green = significantly higher (p < 0.05); blue = significantly lower (p < 0.05); white = no significant differences (p > 0.05).]

In La Luna (Table 3), the highest values for T, K25, and Chl-a were observed during the rainy season; in contrast, the highest DO concentrations were in the dry season. The other variables were similar in both periods.

Table 3.

Environmental variables (X = average; s.d. = standard deviation) of Lake La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023 (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; K25 = electrical conductivity; DO = dissolved oxygen; pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration). (Cluster 1 = October–February; Cluster 2 = March–September.) [Green = significantly higher (p < 0.05); blue = significantly lower (p < 0.05); white = no significant differences (p > 0.05).]

3.3. Zooplankton Composition and Taxonomic Richness

The total zooplankton taxonomic richness (S) of El Sol and La Luna comprised 38 taxa (Table 4), with 31 taxa in El Sol, and 11 taxa in La Luna. Of the 38 taxa, only 4 (~11%) were found in both lakes, with 27 (~71%) only in El Sol and 7 (~18%) only in La Luna.

Table 4.

Phytoplankton taxonomic list of El Sol and La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, México.

The most diverse zooplankton group in El Sol was Rotifera (23 taxa, ~74%), followed by Cladocera (6 taxa, ~19%) and finally Copepoda (2 taxa, ~6%). The most diverse zooplankton group in La Luna was Rotifera (six taxa, ~55%), followed by Cladocera (four taxa, ~36%) and finally Copepoda (one taxon, ~9%). The only four taxa shared between both lakes were the rotifers Cephalodella sp., one unidentified Bdelloid rotifer species, the Cladocera Alona setulose, and the copepod Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci.

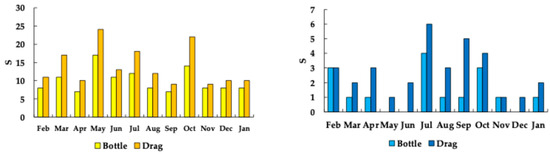

The average S in El Sol was 10 ± 3 (7–17) in the quantitative (Niskin water sampler bottle) samples, while it was 14 ± 5 (9–24) in the qualitative (drags) samples (Figure 6). The average S in La Luna was 1 ± 1 (0–4) in the qualitative samples, while it was 3 ± 2 (1–6) in the samples obtained in the drags (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Zooplankton taxonomic richness (S) in the Nevado de Toluca lakes (Left = El Sol; right = La Luna). (Bottle = quantitative samples; Drag = qualitative samples).

In the rainy season, S in El Sol was 9.5 ± 2.4, while it was 3.3 ± 1.9 in La Luna. In the dry season, S in El Sol was 10.1 ± 3.6, while it was 2.2 ± 1.2 in La Luna.

3.4. Zooplankton Abundance and Biomass

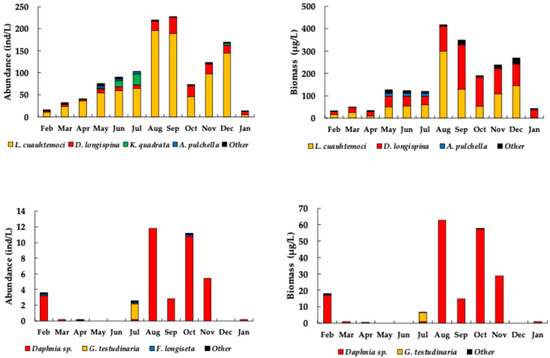

The average abundance of zooplankton in El Sol was 99 ± 74 ind/L, with a range of 13 to 227 ind/L. The highest abundances (above the mean) were observed from July to September and in November and December. The El Sol abundance was dominated by the copepod Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci (~78%), the cladocerans Daphnia longispina group (~14%) and Alonella pulchella (~1%), and the rotifer Keratella quadrata (5%) (Figure 7, Appendix B, Table A2).

Figure 7.

Total zooplankton abundance (left) and biomass (right) in the Nevado de Toluca lakes by dominant taxa (top = El Sol; bottom = La Luna).

In contrast, La Luna had an average abundance of 3 ± 4 ind/L, ranging from 0 to 12 ind/L. The peak abundances in La Luna (above the mean) occurred in February, August, October, and November. La Luna’s abundance was dominated by the cladocerans Daphnia sp. (~91%) and Graptoleberis testudinaria (~5%) and the rotifer Filinia longiseta (~2%) (Figure 7, Appendix C, Table A3).

Regarding biomass, the average zooplankton biomass in El Sol was 166 ± 129 µg/L, with a range of 33 to 418 µg/L. The highest biomasses (above the mean) were recorded from August to December. El Sol biomass was dominated by the copepod Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci (~53%), the cladocerans Daphnia longispina group (~43%), and Alonella pulchella (~3%) (Figure 7, Appendix B, Table A2).

In La Luna, the average biomass was 16 ± 23 µg/L, ranging from 0 to 63 µg/L. The peak biomasses (above the mean) in La Luna also occurred in February, August, October, and November. La Luna’s biomass was dominated by the cladocerans Daphnia sp. (~96%) and Graptoleberis testudinaria (~3%) (Figure 7, Appendix C, Table A3).

Table 5 summarizes the main ecological characteristics of the zooplankton communities in the Nevado de Toluca lakes. The taxonomic richness is generally reduced, whereas that of La Luna corresponds to one-third of El Sol’s. The taxonomic composition differs significantly between the two lakes. The abundance recorded in El Sol greatly exceeds that of La Luna, with the latter comprising approximately 3% of El Sol’s. A similar situation arises with biomass; La Luna’s biomass is approximately 10% of El Sol’s. The dominant taxa in both abundance and biomass differ between the two lakes. Copepods are the most important group in El Sol, while cladocerans are the dominant group in La Luna. The values of the Shannon diversity index in both lakes are very low, lower in La Luna than in El Sol. Likewise, the Pielou evenness index values in both lakes are low, indicating that very few species dominate the abundance, with a smaller number in El Sol than in La Luna.

Table 5.

Taxonomic richness (S), number of common and exclusive taxa, abundance and biomass of zooplankton, and the Shannon–Wiener diversity (H′) and Pielou evenness (J′) indexes in El Sol and La Luna.

4. Discussion

Although some limnological variables showed statistically significant differences, the variations between the lakes or across seasons are minimal. Consequently, these variables can be regarded as having little to no ecological implications. However, it is essential to note that certain variables, such as pH and water transparency, impose severe restrictions on aquatic biota. pH, especially in La Luna, approaches critical levels (i.e., as low as 3.1), restricting the biota to highly tolerant species such as Temnogametum iztacalense, a Charophyta (Zygnematophyceaea) present in La Luna [29], which is a highly tolerant group to acidic environments [30].

Also, the total water transparency allows high doses of solar and ultraviolet radiation (UVR) to reach the bottom of the lakes, preventing a refuge or safe area for organisms to shelter from the harmful effects of UVR. The presence of high concentrations of photoprotective pigments in the zooplankton of both lakes—mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs)—and carotenoids in the copepods of El Sol, as well as carotenoids and melanin in the Cladocera of La Luna, confirms this [31]. T. iztacalense, besides its tolerance to acidic environments, is also tolerant of high UVR doses [30], changing from its characteristic green color to dark purple, imparted by photoprotective compounds (e.g., zeaxanthin).

The average pH of tropical HMLs is 7.7 ± 1.3 (Table 6), so the pH range of El Sol (6.4–8.9) spans both above and below average. In the case of La Luna’s pH range (3.1–6.5), it remains below average. The pH values recorded in El Sol and La Luna are similar to those reported in other tropical HMLs (Table 6). Concerning K25, the average of the tropical HMLs is 157 ± 242 µS/cm (Table 6), excluding two very high records, one from the Kashmir lakes in India and the other from Laguna Lejía in Chile, as they are saline lakes. The ranges of K25 in El Sol (39–46 µS/cm) and La Luna (9–11 µS/cm) fall below average. However, the K25 values recorded in El Sol and La Luna are comparable to those reported in other tropical HMLs (Table 6).

Table 6.

pH and K25 values recorded in tropical HMLs (* one single lake: 18,900 µS/cm; ** saline lake).

Appendix D, Table A4, shows the zooplankton composition, taxonomic richness (S), abundance, and biomass in selected tropical HMLs. Of course, we must consider the great diversity of conditions under which the records were obtained, such as whether the samples come from the littoral or pelagic zones, a specific sampling event, or an annual cycle, and whether the reported numbers are derived from a single body of water or several lakes reported together.

The taxonomic richness recorded in El Sol (31, 10 ± 3) and La Luna (11, 3 ± 2) is within the range of the taxonomic richness reported for other tropical HMLs (2–36, 11 ± 9) (Appendix D, Table A4). In any case, El Sol’s taxonomic richness is closer to the average, while La Luna’s is below-average. However, similar low taxonomic richness has been reported for tropical HMLs like Laguna de Chingaza, Colombia [33], and Lake Tilitso, Nepal [37] (Appendix D, Table A4).

The abundance recorded for El Sol (99 ± 74 ind/L) and La Luna (3 ± 4 ind/L) falls within the low range of the abundance values recorded in tropical HMLs (Appendix D, Table A4), where the average is 59 ± 127 ind/L, spanning a wide range from 0.1 to 543 ind/L. Once again, the abundance of El Sol is closer to but below the average. In contrast, La Luna’s abundance is similar to the lowest values reported for other tropical HMLs, like the lakes in the Mount Everest region [44] and the Cordillera del Tunari, Bolivia [35] (Appendix D, Table A4).

There are very few reports of zooplankton biomass for tropical HMLs. The reported figure averages 406 ± 453 µg/L, ranging from 62 to 920 µg/L (Appendix D, Table A4). Similarly to how abundance behaves, the biomass of El Sol (166 ± 129 µg/L) and La Luna (16 ± 23 µg/L) is recorded as being below the average for the former and even below the lowest values reported in the literature for the latter, like Lake Wonchi, Ethiopia [40] (Appendix D, Table A4).

Tropical seasonality was evident in the meteorological (Figure 2) and limnological (Figure 5) variables. In contrast, zooplankton abundance and biomass dynamics varied between the two lakes, neither exhibiting tropical seasonality. Consequently, no correlations were found (p < 0.05) between zooplankton abundance or biomass and the limnological variables.

The dominant taxa in El Sol (copepods) and La Luna (cladocerans) are herbivorous, feeding on phytoplankton (including unicellular algae), small organic particles, detritus, and bacteria [45]. However, while we anticipated a correlation between phytoplankton and zooplankton biomass peaks, it did not occur as expected. The maximum biomass of zooplankton developed around the same time in both lakes, peaking from July to October in El Sol and from July to November in La Luna. Fernández et al. [29] found that phytoplankton maxima occurred from February to April in El Sol and October to January in La Luna. The zooplankton peak in El Sol was observed two months after the phytoplankton peak, while in La Luna, the zooplankton peak started three months before the phytoplankton peak and ended just as the phytoplankton peak began.

The lack of correlation between phytoplankton and zooplankton in El Sol and La Luna lakes can be attributed to their transparency, which allows UVR to penetrate the bottom. In response to UVR, zooplankton migrate to the lakebed for shelter and alternative food sources, such as benthic algae and bacteria. This behavior allows their development to remain independent of the phytoplankton present in the water column.

The copepod Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci, found in El Sol, is not reported to inhabit tropical HMLs, but instead, its close relatives do (i.e., Arctodiaptomus, Stenodiaptomus). The cladoceran Graptoleberis testudinaria, found in La Luna, is not reported from other tropical HMLs (Appendix D, Table A4). In Ecuadorian HMLs, Aguilera et al. [46] found a shift in dominance from cladocerans below 4200 m a.s.l. to one calanoid copepod above. The altitude shift, 4200 m asl, is precisely the altitude of El Sol, where the copepods dominated, and La Luna, where the cladocerans dominated.

In previous studies of the lakes at Nevado de Toluca, Sarma et al. [47] identified 34 species of rotifers, while Dimas-Flores et al. [48] recorded 29 taxa, only one-third (10 taxa) of which had been documented before by Sarma et al. [47] (Appendix E, Table A5). However, none of the initially recorded 34 rotifer species were found in the current study, and only 4 of the later 29 species were observed. Similarly, earlier research [48,49,50,51,52] reported 21 species of cladocerans in the lakes of Nevado de Toluca (Appendix E, Table A5), yet only 4 were present in the current investigation. Notably, the absence of Alona manueli and Ilyocryptus nevadensis—species described based on specimens from these lakes [49,53]—is significant. Finally, Grimaldo-Ortega et al. [54] and Dimas-Flores et al. [48] recorded six species of copepods (Appendix E, Table A5), but only one, Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemocicuauhtemoci, was found in the current investigation. The Leptodiaptomus species found in the Nevado de Toluca lakes corresponded to the Suárez-Morales et al.’s [55] redescription of Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci.

In addition to the problem of taxonomic resolution that still needs to be resolved, the notable change in zooplankton composition may be related to the fact that various atmospheric pollutants have affected the Nevado de Toluca [56], significantly impacting its lakes (e.g., the water temperature, pH levels, primary productivity, sedimentation, and organic carbon burial rates have all increased, while lake water levels have declined [57]). Alcocer et al. [57] found that these changes affected the benthic macroinvertebrate communities, leading to changes in species composition, decreased taxonomic richness, and reduced abundance and biomass. Similar changes may have also occurred with the zooplankton communities of El Sol and La Luna.

In addition to being extreme ecosystems, more so in La Luna than El Sol, HMLs have environmental characteristics that select for and limit the development of aquatic biota. Consequently, this partially explains the extremely low zooplankton abundance and biomass values. However, the low values were also likely due to a deficit in capturing organisms. During the day, in the highly transparent and shallow waters of HMLs, these organisms are compelled to migrate and “hide” near the bottom to avoid the harmful effects of intense solar and ultraviolet radiation.

Consequently, sampling during the day reveals a significant numerical deficit. Similar deficits have been documented in other studies of HMLs (e.g., [46]). Löffler [16,44] reported pigmented specimens, particularly daphnids, in the shallow, transparent HML of the tropical region). The reported high concentrations of photoprotective pigments, such as MAAs, carotenoids, and melanin, in the zooplankton of El Sol and La Luna [31], giving the organisms a distinctly dark coloration (either reddish/purple or dark brown/black, confirm that UVR plays a vital role in the ecology of the zooplankton in these lakes.

The differences between El Sol and La Luna in their environmental and biological characteristics are partly attributed to the introduction of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in the 1950s. This non-native species has affected the local ecosystem, potentially introducing exotic planktonic organisms along with the rainbow trout. Unfortunately, no studies were conducted on the conditions before the trout’s introduction, so the lakes’ original state is unknown, but there are some paleolimnological studies in La Luna. The introduction of rainbow trout was conducted in both lakes. Nonetheless, the more extreme conditions of La Luna impeded trout survival while they continued to survive in El Sol. However, it seemed that before the extinction of fish from La Luna, the zooplankton community was affected. The human impact around the 1950s in La Luna was recorded in paleolimnological studies, which also noted the disappearance of the Daphnia longispina group at the same time [50,52,58].

As Schindler et al. [59] mentioned, introducing rainbow trout to the lakes significantly changed various ecological characteristics, including species composition and abundance. Fishless lakes, such as La Luna, and those stocked with fish, like El Sol, exhibit markedly different biomasses of large pelagic crustaceans. Specifically, the average size of Daphnia is larger in fishless lakes than in stocked lakes [59]. Alcocer et al. [31] observed that Daphnia sp. in El Sol, which is fish-stocked, is smaller than in the fishless La Luna.

The ongoing presence of trout in El Sol indicates a significant adverse effect on zooplankton. However, there needs to be more evidence regarding this issue. Some studies, such as Fetahia et al. [41], suggest that introducing tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) negatively impacts zooplankton. At the same time, other research, like Aguilera et al. [46], indicates that rainbow trout do not significantly affect zooplankton populations. Conversely, Izaguirre et al. [60] reported that fishless lakes typically have higher total biomasses of zooplankton and macrozooplankton while maintaining lower phytoplankton biomass compared to fish-stocked lakes. However, in our study, El Sol, the fish-stocked lake, demonstrated higher total biomasses of both zooplankton and macrozooplankton, along with greater phytoplankton biomass, in contrast to the fishless La Luna.

5. Conclusions

The zooplankton communities in the tropical HMLs El Sol and La Luna show low taxonomic richness, abundance, and biomass compared to similar lakes. Specifically, the values for La Luna are a mere fraction of those found in El Sol, at 30%, 3%, and 10%, respectively. The dynamics of the zooplankton communities did not follow the tropical seasonality associated with the rainy and dry seasons. Furthermore, they are not linked to phytoplankton dynamics, which serve as the primary food source for the dominant zooplankton species. In El Sol, copepods (Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci) dominate in abundance and biomass. In contrast, cladocerans (Daphnia sp.) are the dominant group in La Luna. The species composition in both lakes is distinct; they share only a small number of taxa. Although the lakes differ in various environmental factors, such as depth, concentrations of dissolved salts, nutrients, chlorophyll, and trophic state, pH is the most significant variable. La Luna has a highly acidic pH, reaching 3.1. The lakes’ high transparency allows substantial amounts of solar and ultraviolet radiation to penetrate the bottom, creating a stressful environment for the biota, as suggested by developing protective mechanisms, such as producing photoprotective pigments. The introduction of rainbow trout in the 1950s contributed to the significant differences in environmental and biological characteristics between the two lakes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; methodology, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; software, R.F. and L.A.O.; validation, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; formal analysis, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; investigation, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; resources, J.A.; data curation, R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A. and R.F.; writing—review and editing, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; visualization, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O.; supervision, J.A., R.F. and L.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Programa de Investigación en Cambio Climático (PINCC), UNAM, through the projects PINCC-2021 and PINCC-2023, and the Programa de Apoyo a los Profesores de Carrera para Promover Grupos de Investigación (PAPCA), UNAM, through the project PAPCA-2022.

Data Availability Statement

The authors can provide data and zooplankton samples from this study upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The Comisión Estatal de Parques Naturales y de la Fauna (CEPANAF, Secretaría de Ecología, Gobierno del Estado de México) provided the permit for scientific research at the Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Nevado de Toluca. We thank E. Montserrat Rivera, Mariana Vargas, and Ismael F. Soria for their support during the fieldwork. Mariana Vargas drew Figure 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Limnological variables of Lake El Sol and La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023 (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; K25 = electrical conductivity; DO = dissolved oxygen; pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration). (Average: first row; standard deviation: second row.)

Table A1.

Limnological variables of Lake El Sol and La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023 (ZMAX = maximum depth; T = temperature; K25 = electrical conductivity; DO = dissolved oxygen; pH = potential of hydrogen; ORP = oxidation–reduction potential; Tur = turbidity; Chl-a = chlorophyll-a concentration). (Average: first row; standard deviation: second row.)

| El Sol | ZMAX | T | K25 | DO | pH | ORP | Tur | Chl-a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | (°C) | (µS/cm) | (mg/L) | pH | (mV) | (NTU) | (µg/L) | |

| February | 9.8 | 4.77 | 44 | 7.94 | 7.8 | 373 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| March | 11.5 | 8.10 | 45 | 7.86 | 8.7 | 346 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| April | 11.0 | 10.59 | 46 | 7.81 | 8.9 | 434 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| 0.54 | 0 | 0.30 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| May | 10.5 | 11.52 | 46 | 6.33 | 8.0 | 281 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 0.46 | 0 | 0.92 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | ||

| June | 10.6 | 10.9 | 44.2 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 334.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 16.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||

| July | 10.8 | 10.35 | 43 | 5.56 | 7.8 | 388 | 0.0 | 1.3 |

| 0.51 | 0 | 1.87 | 0.6 | 27 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||

| August | 9.0 | 12.45 | 42 | 6.99 | 8.8 | 350 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| 0.28 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.2 | ||

| September | 9.0 | 10.46 | 41 | 5.73 | 8.6 | 234 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.06 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| October | 10.5 | 9.90 | 39 | 8.12 | 6.4 | 268 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.18 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| November | 10.5 | 8.9 | 39.1 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 313.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | ||

| December | 10.5 | 7.88 | 39 | 8.32 | 6.5 | 359 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| 0.15 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.3 | 6 | 1.6 | 0.0 | ||

| January | 9.9 | 5.87 | 39 | 8.62 | 8.2 | 224 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 0.22 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | ||

| La Luna | ZMAX | T | K25 | DO | pH | ORP | Tur | Chl-a |

| (m) | (°C) | (µS/cm) | (mg/L) | pH | (mV) | (NTU) | (µg/L) | |

| February | 7.0 | 4.68 | 9 | 7.52 | 5.0 | 458 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.05 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 21 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| March | 8.1 | 9.11 | 10 | 6.83 | 5.1 | 459 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| 0.06 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 3 | 1.8 | 0.0 | ||

| April | 6.5 | 11.03 | 10 | 6.48 | 5.0 | 482 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.10 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| May | 7.2 | 11.54 | 11 | 6.05 | 5.2 | 344 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 0.41 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| June | 7.5 | 11.00 | 10.5 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 376.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 34.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| July | 7.8 | 10.46 | 10 | 6.57 | 5.5 | 408 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.02 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 63 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| August | 6.5 | 12.56 | 10 | 6.38 | 5.2 | 449 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.33 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| September | 7.5 | 9.77 | 10 | 6.24 | 6.5 | 334 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.22 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| October | 7.8 | 10.22 | 10 | 6.97 | 4.4 | 361 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.75 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| November | 7.6 | 8.89 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 391.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.42 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| December | 7.3 | 7.57 | 10 | 7.11 | 3.1 | 421 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.08 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| January | 7.0 | 7.17 | 10 | 7.43 | 4.1 | 360 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.56 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 22 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Zooplankton abundance and biomass of Lake El Sol, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023.

Table A2.

Zooplankton abundance and biomass of Lake El Sol, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023.

| Abundance (ind/L) | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotifera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Asplanchna cf priodonta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Asplanchnella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachionus angularis | 0 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachionus havanaensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plationus patulus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalodella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalodella cf doryphora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Echlanis dilatata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Filinia cf. longiseta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella quadrata | 1 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 14 | 25.4 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 4 | 0 |

| Keratella cochlearis | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella americana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella valga | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella lensi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lecane lunaris | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Lecane acuminata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella acuminata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella patella | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella ovalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichocerca cf bicristata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichocerca cf cylindrica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichotria tetractis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified bdelloid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cladocera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Alona setulosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Alonella pulchella | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

| Ceriodaphnia dubia group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chydorus sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia longispina group | 2 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 8.8 | 8 | 7.2 | 21 | 37 | 24.6 | 21.2 | 17.8 | 7 |

| Eurycercus pompholygodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Copepoda Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Paracyclops fimbriatus | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci | 11 | 23.4 | 36 | 54.4 | 59.6 | 64.8 | 196.2 | 189 | 46 | 97.8 | 145.2 | 5 |

| Total abundance | 15.2 | 31.8 | 40.2 | 76 | 90.2 | 103.2 | 220.2 | 227.4 | 73.4 | 123.5 | 169 | 13.4 |

| Biomass (µg3/L) | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan |

| Rotifera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Asplanchna cf. priodonta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0892 | 0.156 | 0.223 | 0 | 0 | 0.268 | 0.156 | 0.045 | 0.045 |

| Asplanchnella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.624 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachionus angularis | 0 | 0.016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachionus havanaensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plationus patulus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalodella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalodella cf. doryphora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Echlanis dilatata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Filinia cf. longiseta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella quadrata | 0.02 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.052 | 0.28 | 0.508 | 0 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.052 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Keratella cochlearis | 0 | 0.0004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella americana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella valga | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Keratella lensi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lecane lunaris | 0 | 0 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 |

| Lecane acuminata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella acuminata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella patella | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella ovalis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichocerca cf. bicristata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichocerca cf. cylindrica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trichotria tetractis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified bdelloid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 |

| Cladocera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Alona setulosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.424 | 4.446 | 0.468 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.468 | 0.936 | 0 |

| Alonella pulchella | 3.05 | 0 | 0 | 13.42 | 13.73 | 14.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.61 | 2.44 | 4.27 | 2.44 |

| Ceriodaphnia dubia group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chydorus sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia longispina group | 10.64 | 22.344 | 18.088 | 46.816 | 42.56 | 38.3 | 111.7 | 196.8 | 130.9 | 112.8 | 94.7 | 37.24 |

| Eurycercus pompholygodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Copepoda Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Paracyclops fimbriatus | 0.738 | 0 | 0 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.738 |

| Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci | 18.75 | 26.97 | 16.976 | 58.372 | 62.216 | 66.06 | 305.596 | 151.5 | 58.346 | 122.51 | 168.24 | 1.968 |

| Total biomass | 33 | 49 | 35 | 127 | 123 | 120 | 418 | 349 | 190 | 238 | 268 | 42 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Zooplankton abundance and biomass of Lake La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023.

Table A3.

Zooplankton abundance and biomass of Lake La Luna, Nevado de Toluca, measured from February 2022 to January 2023.

| Abundance (ind/L) | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotifera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Cephalodella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Filinia longiseta | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hexarthra sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella cf. quinquecostata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Notomata sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified bdelloid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cladocera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Alona setulosa | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alona sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Graptoleberis testudinaria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia sp. | 3.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 11.8 | 2.8 | 10.8 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Copepoda Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Abundance | 3.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 11.8 | 2.8 | 11.2 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Biomass (µg3/L) | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan |

| Rotifera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Cephalodella sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Filinia longiseta | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hexarthra sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lepadella cf. quinquecostata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Notomata sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified bdelloid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cladocera Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Alona setulosa | 0 | 0 | 0.468 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alona sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Graptoleberis testudinaria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia sp. | 17.02 | 1.064 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.064 | 62.78 | 14.9 | 57.46 | 28.73 | 0 | 1.064 |

| Copepoda Taxa | ||||||||||||

| Leptodiaptomus cuauhtemoci | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Biomass | 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 63 | 15 | 57 | 29 | 0 | 1 |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Zooplankton composition, taxonomic richness (S), abundance, and biomass in other tropical HMLs.

Table A4.

Zooplankton composition, taxonomic richness (S), abundance, and biomass in other tropical HMLs.

| Lake | Group | Taxa | S | Abundance (ind/L) | Biomass (µg/L) | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Partial | Total | Partial | |||||

| Nepallese HMLs | 22 | [32] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Conochiloides coenobasis | 10 (1–5) | ||||||

| Keratella spp. | ||||||||

| Lecane sp. | ||||||||

| Filinia sp. | ||||||||

| Hexarthra bulgarica nepalensis | ||||||||

| Hexarthra bulgarica | ||||||||

| Polyarthra | ||||||||

| Keratella quadrata | ||||||||

| Filinia major | ||||||||

| Conochilus unicornis | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia longispina | 8 (0–6) | ||||||

| Holopendium sp. | ||||||||

| Daphnia spp. | ||||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | ||||||||

| Alona sp. | ||||||||

| Macrothrix sp. | ||||||||

| Simocephalus vetulus | ||||||||

| Branchinecta orientalis | ||||||||

| Copepods | Stenodiaptomus stewartienses | 4 (1–2) | ||||||

| Cyclops | ||||||||

| Arctodiaptomus altissimus | ||||||||

| Arctodiaptomus jurisovitchi | ||||||||

| Laguna de Chingaza, Colombia | 3 | [33] | ||||||

| Cladocerans | Ceriodaphnia dubia | 2 | 0.45 to 6.6 | |||||

| Daphnia leavis | 0.097 to 2.2 | |||||||

| Copepods | Colombodiaotomus brandorffi | 1 | 3.1 to 28 | |||||

| Ethiopian HMLs | 23 (6–13) | copepods 17, rotifers 11, cladocerand 4.5 | [34] | |||||

| Dendi | 9 | |||||||

| Rotifers | Keratella tropica | 3 | ||||||

| Trichocerca smilis | ||||||||

| Polyarthra sp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia magna | 5 | ||||||

| Daphnia longispina | ||||||||

| Diaphanosoma excisum | ||||||||

| Ceriodaphnia quadrangula | ||||||||

| Thermocyclopes ethiopiensis | ||||||||

| Copepods | Thermocyclopes ethiopiensis | 1 | ||||||

| Wonchi | 13 | |||||||

| Rotifers | Asplanchna sieboldii | 6 | ||||||

| Trichocerca gracilis | ||||||||

| Filinia longiseta | ||||||||

| Keratella cf. cochlearis | ||||||||

| Polyarthra sp. | ||||||||

| Brachionus caudatus | ||||||||

| Cladocera | Daphnia longispina | 6 | ||||||

| Daphanosoma excisum | ||||||||

| Bosmina longirostris | ||||||||

| Ceriodaphnia reticulata | ||||||||

| Moina micrura | ||||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | ||||||||

| Copepods | Thermocyclopes ethiopiensis | 1 | ||||||

| Ziqualla | 6 | |||||||

| Rotifers | Trichocerca sp. | 3 | ||||||

| Lecane sp. | ||||||||

| Platias sp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Ceriodaphnia reticulata | 2 | ||||||

| Chydorus sp. | ||||||||

| Copepods | Cyclopoid copepods | 1 | ||||||

| Glacial lakes Cajas National Park, Ecuador | [35] | |||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia | dominated by large cladocerans and cyclopoid copepods, or by B. occidentalis | ||||||

| Bosmina | ||||||||

| Copepods | Boeckella occidentalis | |||||||

| Ecuadorian high Andes | 8 | [36] | ||||||

| Páramo (11 lakes) | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Bosmina longirostris | 3 | 0.7 | 800 | ||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | 0.3 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Daphnia sp. | 4 | 55 | ||||||

| Copepods | Boeckella occidentalis | 4 | 8 | 33 | ||||

| Calanoida indet | 27 | 30 | ||||||

| Cyclopoida indet. | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Cyclops/Metacyclops | 0.3 | 1 | ||||||

| pH: 5.1–8.5 | Glacial (6 lakes) | |||||||

| K25: 6–25 µS/cm | Cladocerans | Bosmina longirostris | 3 | BDL | BDL | |||

| Daphnia sp. | BDL | BDL | ||||||

| Eurycercus sp. | BDL | BDL | ||||||

| Copepods | Calanoida indet | 2 | 0.04 | 0.01 | ||||

| Boeckella occidentalis | 0.02 | 600 | ||||||

| Mount Everest region | 3 max per lake | 50 max | [44] | |||||

| Rotifers | Hexarthra cf. bulgarica | 3 | ||||||

| Eumlanis sp. | ||||||||

| Polyarthra sp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia tibetana | 2 | ||||||

| Daphnia sp. longispina-group | ||||||||

| Copepods | Arctodiaptomus jurisovimi | 1 | ||||||

| Lake Tilitso, Mt. Annapurna Nepal | 2 | [37] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Hexarthra bulgarica nepalensis | BDL | ||||||

| Copepods | Arctodiaptomus altissimus | 1 to 543 | ||||||

| Lake San Pablo, Ecuador | 6 | [61] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Keratella quadrata | 4 | 25 | |||||

| Keratella tropica tropica | ||||||||

| Trichocerca cylindrica-chattoni | ||||||||

| Trichocerca sp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia pulex | 1 | <6 | |||||

| Copepods | Metacyclops mendocinus | 1 | <20 | |||||

| Kashmir lakes, India | 9 | [38] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Keratella quadrata | 4 | ||||||

| Keratella valga | ||||||||

| Brachionus quadridentatus | ||||||||

| Polyarthra spp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Ceriodaphnia pulmella | 2 | ||||||

| Alonella spp. | ||||||||

| Branchiopoda | Diaphanosoma bramyurum | 2 | ||||||

| Pleuroxus spp. | ||||||||

| Copepods | Acanthodiaptomus denticornis | 1 | ||||||

| Himalayan region | 11 | [62] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Asplanchna brightwelli | 5 | ||||||

| A. pridonta | ||||||||

| Alona affinis | ||||||||

| A. costata | ||||||||

| Keratella quadrata | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia pulex | 2 | ||||||

| Chydorus spharicus | ||||||||

| Copepods | Acanthodiaptomus denticomis | 4 | ||||||

| Arctodiaptomus parvispinus | ||||||||

| Cyclops vicinus | ||||||||

| Limnocalanus sp. | ||||||||

| Lake Yahuarcocha, Ecuador | [39] | |||||||

| Rotifers | Brachionus angularis | Dominant: rotifers and cyclopoid copepods | ||||||

| Keratella spp. | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia pulex | |||||||

| Copepods | Acanthocyclops | |||||||

| Cordillera del Tunari, Cochabamba, Bolivia | [46] | |||||||

| Rotifers | 0.82 to 24.51 | |||||||

| Cladocera | Daphnia pulex | 0.11 to 3.31 (D. pulex 0 to 1.35) | ||||||

| Copepods | Calanoids | 7.08 to 56.02 | ||||||

| Cyclopoids | 1.41 to 3.65 | |||||||

| Lake Wonchi, Ethiopia | 14 | 50 | 62.02 ± 25.76 | [40] | ||||

| Rotifers | Asplanchna sieboldii | 7 | 8 | 8% | ||||

| Trichocerca gracilis | Dominant: K. cochlearis | |||||||

| Filinia longiseta | ||||||||

| Keratella cochlearis | ||||||||

| Polyarthra sp. | ||||||||

| Brachionus caudatus | ||||||||

| Brachionus dimidiatus | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Daphnia longispina | 6 | 17 | 53% | ||||

| Diaphanosoma excisum | Dominant: D. longispina & B. longirostris | |||||||

| Bosmina longirostris | ||||||||

| Ceriodaphnia reticulata | ||||||||

| Moina micrura | ||||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | ||||||||

| Copepods | Thermocyclops ethiopiensis | 1 | 25 | 39% | ||||

| Lake Hayq, Ethiopia | 11 | 67,280 | 236.4 | [41] | ||||

| Rotifers | Brachionius angularis | 6 | 300 ± 68 | |||||

| Brachionius quadridentatus | 260 ± 54 | |||||||

| Euchlanis parva | 627 ± 110 | |||||||

| Keratella tropica | 760 ± 184 | |||||||

| Polyarthra | 957 ± 242 | |||||||

| Trichocerca smilis | 457 ± 74 | |||||||

| Cladocerans | Ceriodaphnia reticulata | 3 | 2242 ± 612 | |||||

| Daphnia magna | 2659 ± 330 | |||||||

| Diaphanosoma excisum | 3521 ± 419 | |||||||

| Copepods | Mesocyclops aequatorialis | 2 | 10,716 ± 1080 | |||||

| Thermocyclops ethiopiensis | 26,002 ± 3410 | |||||||

| Lake Sarincof, Turkey | 36 | [42] | ||||||

| Rotifers | Cephalodella catellina | 27 | 51.0% | |||||

| Cephalodella gibba | ||||||||

| Conochilus hippocrepis | ||||||||

| Encentrum uncinatum | ||||||||

| Euchlanis dilatata | ||||||||

| Filinia longiseta | ||||||||

| Filinia longiseta | ||||||||

| Keratella tecta | ||||||||

| Lecane closterocerca | ||||||||

| Lecane flexilis | ||||||||

| Lecane lunaris | ||||||||

| Lecane lunaris | ||||||||

| Lepadella acuminata | ||||||||

| Lepadella ovalis | ||||||||

| Lepadella patella | ||||||||

| Lepadella quadricarinata | ||||||||

| Monommata grandis | ||||||||

| Notholca squamula | ||||||||

| Philodina megalotrocha | ||||||||

| Polyarthra vulgaris | ||||||||

| Polyarthra vulgaris | ||||||||

| Synchaeta pectinata | ||||||||

| Synchaeta pectinata | ||||||||

| Trichocerca longiseta | ||||||||

| Trichocerca longiseta | ||||||||

| Trichocerca pusilla | ||||||||

| Trichocerca similis | ||||||||

| Trichotria tetractis | ||||||||

| Cladocerans | Alona guttata | 6 | 20.7% | |||||

| Alona affinis | ||||||||

| Ceriodaphnia dubia | ||||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | ||||||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | ||||||||

| Moina micrura | ||||||||

| Copepods | Arctodiaptomus aculitobatus acutilobatus | 3 | 28.3% | |||||

| Canthocamptus staphylinus staphylinus | ||||||||

| Mesocyclops leuckarti leuckarti | ||||||||

| Laguna Lejía, Chile | 3 | [43] | ||||||

| Cladocerans | Alona sp. | 2 | 0 to 0.02 | |||||

| Macrothrix palearis | 0 to 1.6 | |||||||

| Copepods | Diacyclops andinus | 1 | 0 to 0.32 | |||||

Appendix E

Table A5.

Zooplankton taxa recorded for the Nevado de Toluca Lakes (1 = [47]; 2 = [48]; 3 = [63]; 4 = [49]; 5 = [51]; 6 = [58]; 7 = [50]; 8 = [64]; 9 = [54]). (The columns are ordered from the oldest records on the left to the most recent on the right).

Table A5.

Zooplankton taxa recorded for the Nevado de Toluca Lakes (1 = [47]; 2 = [48]; 3 = [63]; 4 = [49]; 5 = [51]; 6 = [58]; 7 = [50]; 8 = [64]; 9 = [54]). (The columns are ordered from the oldest records on the left to the most recent on the right).

| Rotifera | El Sol | La Luna | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [2] | Present | [1] | [2] | Present | ||||||||

| Ascomorpha saltans | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Aspelta lestes | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Aspelta psitta | – | X | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Asplanchna cf. priodonta | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Asplanchnella sp. | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Unidentified bdelloid | – | X | X | – | X | X | |||||||

| Brachionus angularis | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Brachionus bidentatus | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Brachionus havanaensis | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Brachionus urceolaris | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella cf. doryphora | – | X | – | – | – | ||||||||

| Cephalodella cf. eva | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella cf. mira | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella cf. ventripes | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella cf. vitella | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella delicata | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella gibba | X | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella hoodi | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella panarista | X | X | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Cephalodella sp. | – | – | X | – | – | X | |||||||

| Cephalodella tenuiseta | – | X | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Colurella calurus | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Colurella obtusa | – | X | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Conochillus unicornis | X | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Dicranophorus cf. epicharis | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Dicranophorus forcipatus | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Dicranophorus grandis | – | – | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Echlanis dilatata | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Filinia cf. longiseta | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Filinia longiseta | – | – | – | – | – | X | |||||||

| Hexarthra bulgarica canadensis | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Hexarthra sp. | – | – | – | – | – | X | |||||||

| Kellicottia bostoniensis | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella americana | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella cochlearis | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella lensi | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella quadrata | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella tropica | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Keratella valga | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane acuminata | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane bulla | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane closterocerca | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane flexilis | X | X | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane furcata | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Lecane inopinata | – | – | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane lunaris | X | X | X | – | X | – | |||||||

| Lecane scutata | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lecane tenuiseta | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lepadella acuminata | – | X | X | X | X | – | |||||||

| Lepadella cf. quinquecostata | – | – | – | – | – | X | |||||||

| Lepadella ovalis | – | – | X | X | – | – | |||||||

| Lepadella patella | – | – | X | X | – | – | |||||||

| Lepadella quinquecostata | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Lepadella rhomboides | – | – | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Notomata cerberus | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Notomata sp. | – | – | – | – | – | X | |||||||

| Notommata glyphura | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Plationus patulus | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Pleurotrocha sp. | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Polyarthra dolichoptera | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Polyarthra vulgaris | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Proales sp. | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Synchaeta oblonga | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Synchaeta pectinata | – | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Taphrocampa annulosa | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Testudinella emarginula | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Trichacerca similis | – | – | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Trichacerca tigris | – | – | – | X | X | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca bicristata | X | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca bidens | – | – | – | X | – | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca cf. bicristata | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca cf. cylindrica | – | – | X | – | – | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca collaris | X | X | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca longiseta | – | X | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Trichocerca vernalis | – | – | – | – | X | – | |||||||

| Trichotria tetractis | X | X | X | – | X | – | |||||||

| Cladocera | El Sol | La Luna | |||||||||||

| [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | Present | [2] | [3] | [6] | [4] | [7] | [5] | [8] | Present | |

| Alona cf. setulosa | X | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alona manueli (Alpinalona manueli) | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | X | X | X | – |

| Alona ossiani | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alona setulosa | – | – | – | – | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| Alona sp. | – | – | – | X | - | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | X |

| Alonella pulchella | X | – | – | – | X | X | – | X | X | X | X | X | – |

| Biapertura affinis | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Biapertura intermedia | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bosmina sp. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| Ceriodaphnia dubia group | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chydorus cf. sphaericus | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – |

| Chydorus sp. | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chydorus sphaericus group | – | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | X | X | X | – | – |

| Daphnia ambigua | X | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Daphnia longispina group | – | – | – | X | X | – | – | X | – | X | X | X | – |

| Daphnia sp. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| Eurycercus cf. pompholygodes | X | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eurycercus intermedia | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eurycercus longirostris | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eurycercus pompholygodes | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eurycercus sp. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| Graptoleberis testudinaria | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| Iliocryptus nevadensis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | X | – |

| Iliocryptus sp. | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Leydigia sp. | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pleuroxus cf. denticulatus | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Copepoda | El Sol | La Luna | |||||||||||

| [2] | [9] | Present | [2] | Present | |||||||||

| Acanthocyclops robustus | – | X | – | – | – | ||||||||

| Leptodiaptomus assiniboiaensis | – | X | – | – | – | ||||||||

| Leptodiaptomuscuauhtemoci | X | – | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Leptodiaptomus montezumae | – | X | – | – | – | ||||||||

| Leptodiaptomus novamexicanus | – | X | – | – | – | ||||||||

| Paracyclops fimbriatus | X | – | X | X | – | ||||||||

References

- Catalan, J.; Camarero, L.; Felip, M.; Pla, S.; Ventura, M.; Buchaca, T.; Bartumeus, F.; De Mendoza, G.; Miró, A.; Casamayor, E.O.; et al. High Mountain Lakes: Extreme Habitats and Witnesses of Environmental Changes. Limnetica 2006, 25, 551–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, P.; Prearo, M. High-Mountain Lakes, Indicators of Global Change: Ecological Characterization and Environmental Pressures. Diversity 2020, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, D.; Dangles, O. Ecology of High Altitude Waters; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-873687-5. [Google Scholar]

- Löffer, H. Tropical High-Mountain Lakes. Their Distribution, Ecology and Zoogeographical Importance. In Geo-Ecology of the Mountainous Regions of the Tropical Americas; Ferd. Dümmlers Verlag: Bonn, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Löffer, H. The Limnology of Tropical High-Mountain Lakes. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 1964, 15, 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Catalan, J.; Donato Rondón, J.C. Perspectives for an Integrated Understanding of Tropical and Temperate High-Mountain Lakes. J. Limnol 2016, 75, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, D.W. Lakes as Sentinels and Integrators for the Effects of Climate Change on Watersheds, Airsheds, and Landscapes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.M. Tropical Lakes: How Latitude Makes a Difference. In Perspectives in Tropical Limnology; SPB Academic Publishing bv: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Criales-Hernández, M.I.; Sanchez-Lobo, D.M.; Almeyda-Osorio, J.K. Expanding the Knowledge of Plankton Diversity of Tropical Lakes from the Northeast Colombian Andes. RBT 2020, 68, S159–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, J.L. Geología e historia eruptiva de algunos de los grandes volcanes activos de México. BSGM 2005, 57, 379–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palomo, A.; Macías, J.L.; Arce, J.L.; Capra, L.; Garduño, V.H.; Espíndola, J.M. Geology of Nevado de Toluca Volcano and Surrounding Areas, Central Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Map Chart Ser. MCH089 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alcocer, J.; Oseguera, L.A.; Escobar, E.; Peralta, L.; Lugo, A. Phytoplankton Biomass and Water Chemistry in Two High-Mountain Tropical Lakes in Central Mexico. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2004, 36, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzedowski, J. Vegetación de México; LIMUSA: CDMX, México, 1981; ISBN 978-968-18-0002-4. [Google Scholar]

- Armienta, M.A.; Vilaclara, G.; De la Cruz-Reyna, S.; Ramos, S.; Ceniceros, N.; Cruz, O.; Aguayo, A.; Arcega-Cabrera, F. Water Chemistry of Lakes Related to Active and Inactive Mexican Volcanoes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2008, 178, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, P.; Montero, A.; Junco, R. Las Aguas Celestiales: Nevado de Toluca, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia—INAH: CDMX, México, 2009; ISBN 978-968-03-0378-6. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, H. Contribution to the Limnology of High Montain Lakes in Central America. Int. Rev. Der Gesamten Hydrobiol. Und Hydrogr. 1972, 57, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, E.J.; Collins, G.B. Method 445.0 In Vitro Determination of Chlorophyll a and Pheophytin Ain Marine and Freshwater Algae by Fluorescence; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Nandini, S. Rotíferos Mexicanos (Rotifera). In Manual de Enseñanza; UNAM, FES Iztacala: Toluca, México, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Koste, W. Rotatoria: Die Rädertiere Mitteleuropas; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978; Volumes 1 and 2, ISBN 978-3-443-39076-1. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Morales, E.; Gutierrez-Aguirre, M.A. Morfología y Taxonomía de Los Mesocyclops (Crustacea: Copepoda: Cyclopoida) de México; Ecosur-Conacyt: Chetumal, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Benzie, J.A. Cladocera: The Genus DAPHNIA (Including DAPHNIOPSIS) (Anomopoda: Daphniidae); Guides to the Identification of the Microinvertebrates of the Continental Waters of the World; Blackhuys: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; ISBN 978-90-5782-151-6. [Google Scholar]

- Korovchinsky, N.M. Sididae & Holopediidae (Crustacea: Daphniiformes); Guides to the Identification of the Microinvertebrates of the Continental Waters of the World; SPB Academic Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; ISBN 978-90-5103-074-7. [Google Scholar]

- Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Suárez Morales, E.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M.A.; Silvia Briano, M.; Granados Ramírez, J.G.; Garfias Espejo, T. Cladocera y Copepoda de Las Aguas Continentales de México: Guía Ilustrada; UNAM, FES Iztacala: Tlalnepantla, Mexico, 2008; ISBN 978-970-32-4852-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado-Salas, N.F.; Pozo, C.; Morrone, J.J.; Suárez-Morales, E. Distribution Patterns of the American Species of the Freshwater Genus Eucyclops (Copepoda: Cyclopoida). J. Crustac. Biol. 2012, 32, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttner-Kolisko, A. Suggestions for Biomass Calculation of Plankton Rotifers. Arch. Hydrobiol. Beih. Ergebn. Limnol. 1977, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mccauley, E. The Estimation of the Abundance and Biomass of Zooplankton in Samples. In Manual on Methods for the Assessment of Secondary Productivity in Fresh Waters; Blackwell Science Inc.: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 228–265. [Google Scholar]

- Bonecker, C.C.; Nagae, M.Y.; Bletller, M.C.M.; Velho, L.F.M.; Lansac-Tôha, F.A. Zooplankton Biomass in Tropical Reservoirs in Southern Brazil. Hydrobiologia 2007, 579, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talling, J.F.; Lemoalle, J. Ecological Dynamics of Tropical Inland Waters; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-521-62115-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, R.; Alcocer, J.; Oseguera, L.A.; Zuñiga-Ramos, C.A.; Vilaclara, G. Phytoplankton Communities’ Seasonal Fluctuation in Two Neighboring Tropical High-Mountain Lakes. Plants 2024, 13, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Pichrtová, M. Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Charophyte Green Algae: New Challenges for Omics Techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, J.; Delgado, C.N.; Sommaruga, R. Photoprotective Compounds in Zooplankton of Two Adjacent Tropical High Mountain Lakes with Contrasting Underwater Light Climate and Fish Occurrence. J. Plankton Res. 2020, 42, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, C.M. A Brief Review on Limnological Status of High Altitude Lakes in Nepal. J. Wetl. Ecol. 2009, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria, S. Crustacean Plankton of a High Altitude Tropical Lake: Laguna de Chingaza, Colombia. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 1993, 25, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefu, F.; Herzig, A.; Jirsa, F.; Schagerl, M. First Limnological Records of Highly Threatened Tropical High-Mountain Crater Lakes in Ethiopia. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2014, 7, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Colen, W.R.; Mosquera, P.; Vanderstukken, M.; Goiris, K.; Carrasco, M.-C.; Decaestecker, E.; Alonso, M.; León-Tamariz, F.; Muylaert, K. Limnology and Trophic Status of Glacial Lakes in the Tropical Andes (Cajas National Park, Ecuador). Freshw. Biol. 2017, 62, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, B.; Mouillet, C.; Espinosa, R.; Andino, P.; Jacobsen, D.; Christoffersen, K.S. Glacial-Fed and Páramo Lake Ecosystems in the Tropical High Andes. Hydrobiologia 2018, 813, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaki, M.; Terashima, A.; Nakahara, H.; Nishio, T.; Ishida, Y. Trophic Status of Tilitso, a High Altitude Himalayan Lake. Hydrobiologia 1987, 153, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutshi, D.P.; Kaul, V.; Vass, K.K. Limnology of High Altitude Kashmir Lakes. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 1972, 18, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Colen, W.; Portilla, K.; Oña, T.; Wyseure, G.; Goethals, P.; Velarde, E.; Muylaert, K. Limnology of the Neotropical High Elevation Shallow Lake Yahuarcocha (Ecuador) and Challenges for Managing Eutrophication Using Biomanipulation. Limnologica 2017, 67, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefu, F.; Schagerl, M. Zooplankton Abundance, Species Composition and Ecology of Tropical High-Mountain Crater Lake Wonchi, Ethiopia. J. Limnol. 2015, 74, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetahi, T.; Mengistou, S.; Schagerl, M. Zooplankton Community Structure and Ecology of the Tropical-Highland Lake Hayq, Ethiopia. Limnologica 2011, 41, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüzer, P.; Altındağ, A.; Tekatlı, G.; Tekatlı, Ç. Zooplankton Fauna of High Mountain Lake: Sarıncof (Çamlıhemşin, Rize, Turkey). KSU J. Agric Nat. 2023, 26, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pedreros, A.; De Los Ríos, P.; Möller, P. Zooplankton in Laguna Lejía, a High-Altitude Andean Shallow Lake of the Puna in Northern Chile. Crustac 2013, 86, 1634–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, H. High Altitude Lakes in Mt. Everest Region. Int. Ver. Für Theor. Und Angew. Limnol. Verhandlungen 1969, 17, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Seinos, J.L.; Alcocer, J.; Planas, D. Food Web Differences between Two Neighboring Tropical High Mountain Lakes and the Influence of Introducing a New Top Predator. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, X.; Declerck, S.; De Meester, L.; Maldonado, M.; Ollevier, F. Tropical High Andes Lakes: A Limnological Survey and an Assessment of Exotic Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Limnologica 2006, 36, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Soto Serranía, C. Rotifers from high altitude crater-lakes at Nevado de Toluca Volcano, México. Hidrobiológica 1997, 6, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dimas-Flores, N.; Alcocer, J.; Ciros-Pérez, J. The Structure of the Zooplankton Assemblages from Two Neighboring Tropical High Mountain Lakes. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2008, 23, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinev, A.Y.; Zawisza, E. Comments on Cladocerans of Crater Lakes of the Nevado de Toluca Volcano (Central Mexico), with the Description of a New Species, Alona manueli sp. Nov. Zootaxa 2013, 3647, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuna, E.; Zawisza, E.; Caballero, M.; Ruiz-Fernández, A.C.; Lozano-García, S.; Alcocer, J. Environmental Impacts of Little Ice Age Cooling in Central Mexico Recorded in the Sediments of a Tropical Alpine Lake. J. Paleolimnol. 2014, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeroczyńska, K.; Zawisza, E.; Wojewódka, M. Initial Time Of Two High Altitude Crater Lakes (Nevado De Toluca, Central Mexico) Recorded In Subfossil Cladocera. Stud. Quat. 2015, 32, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caballero, M.; Zawisza, E.; Hernández, M.; Lozano-García, S.; Ruiz-Córdova, J.P.; Waters, M.N.; Ortega-Guerrero, B. The Holocene History of a Tropical High-Altitude Lake in Central Mexico. Holocene 2020, 30, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Martínez, A.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M. Description of Iyocryptus Nevadensis (Branchiopoda, Anomopoda), a New Species from a High Altitude Crater Lake in the Volcano Nevado de Toluca, Mexico. Crustaceana 2000, 73, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldo-Ortega, D.; Elıas-Gutierrez, M.; Camacho-Lemus, M.; Ciros-Perez, J. Additions to Mexican Freshwater Copepods with the Description of the Female Leptodiaptomus mexicanus (Marsh). J. Mar. Syst. 1998, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]