Abstract

The current knowledge of Sicilian inland water decapod malacostracans is scarce and an updated synopsis on species distribution is lacking. Therefore, we reviewed the checklist and recent distribution of Sicilian inland water decapods based on published and unpublished records and novel observations with the aim of providing an exhaustive repository, also to be used as a sound baseline for future surveys. Overall, five native decapod species occur in the study area, i.e., the atyid shrimp Atyaephyra desmarestii, the palaemonid shrimps Palaemon adspersus, P. antennarius, and P. elegans, and the freshwater crab Potamon fluviatile, and their current local distributions are described. In addition, three alien species were recorded: the common yabby Cherax destructor and the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii, strictly linked to inland waters, and the Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus, a mainly marine species that can also colonise the lower stretches of rivers and coastal brackish waters. The collected data suggest the existence of a partial segregation of native versus non-native species, with the latter currently confined to coastal water bodies and the lower stretches of rivers. Moreover, the exclusively freshwater caridean A. desmarestii and P. antennarius show a parapatric distribution in the study area, which may suggest the existence of mutual exclusion phenomena. The results obtained raise some concerns about the effects of alien species on the native biota, and dedicated monitoring and management strategies should be implemented in order to better understand and mitigate their impact.

1. Introduction

Despite their limited extent and their intrinsically vulnerable nature, inland water ecosystems are among the most biologically diverse habitats on Earth [1]. At the same time, they are particularly susceptible to external disturbances [2]. Changes in their hydroperiod or the introduction of non-indigenous species are known to cause severe impacts on these fragile ecosystems, leading to the local or global extinction of several taxa [3,4,5,6]. The vulnerability of inland water ecosystems is particularly high in islands and in arid and semi-arid regions, where they are extremely fragile and water demand for human needs is high [3,7,8]. In fact, human activities have often dramatically modified inland water ecosystems, leading to significant habitat alteration and to the decline or loss of freshwater biological diversity [9,10].

To date, the invertebrate fauna inhabiting the inland waters of Sicily is inadequately and unevenly known. Although detailed information is available for some taxa (e.g., non-malacostracan crustaceans; see [11,12,13]), a wide knowledge gap still remains to be filled for the other taxa, thus preventing an accurate picture of the current biological diversity to be obtained. This is the case of the decapod malacostracans, which have never been the subject of an accurate synoptic study. In the frame of this work, we carried out an accurate review of the current knowledge about the occurrence and distribution of decapods in Sicilian inland waters, with a focus on the last four decades.

2. Materials and Methods

The study area considered in this work includes Sicily and the small circum-Sicilian islands.

Since our purpose was to obtain information regarding the current distribution of the species in the study area, the review of bibliographical data was limited to papers published after 1980. Therefore, pre-1980 data stored in the CKmap database [14] were not considered. In addition, a set of unpublished occurrence data is reported herein based on observations made by Filippo Amato (F.A.), Andrea Cusmano (A.C.), Reinhard Gerecke (R.G.), Gabriele Giacalone (G.G.), Federico Marrone (F.M.), Fiorenza Provenzano (F.P.), Francesco Paolo Faraone (F.P.F.), Salvatore Russotto (S.R.), Giuseppe Urso (G.U.), and Luca Vecchioni (L.V.). All available data were critically evaluated and, when considered reliable, included in the analyses.

Decapod specimens collected in the frame of this study were identified according to Williams [15], Froglia [16], González-Ortegón and Cuesta [17], Holdich and Vigneux [18], and González-Ortegón et al. [19].

Occurrence localities were used to produce distribution maps based on the UTM 10 × 10 Km grid cells (zone 33N, datum ED50) using the QGIS freeware software v. 3.18 (QGIS Development Team, 2022 [20]).

Based on the complete dataset, cumulative curves describing the increase of sites and grid cells occupied by alien species, as well as alien species richness, are presented.

3. Results

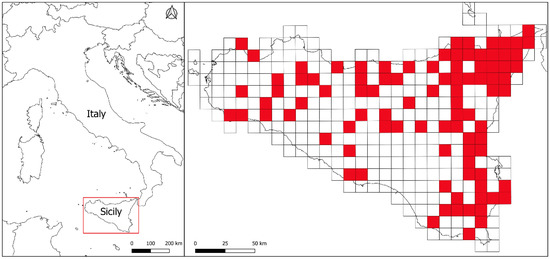

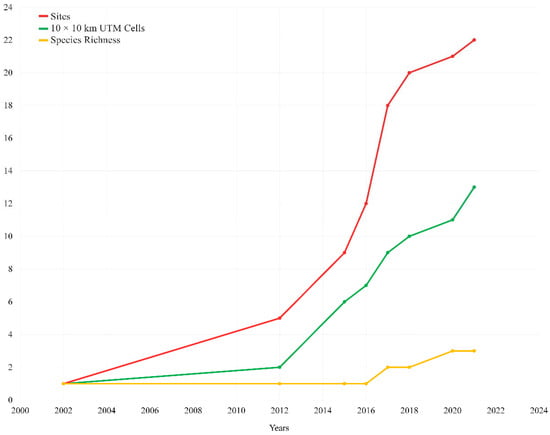

Overall, the occurrence of eight decapod species belonging to six families was reported in 93 sites (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 and Table 1). The first record of an alien decapod in Sicilian inland waters dates to 2002 [21], and a sharply increasing rate of the number of alien species and their distribution sites was observed from 2012 onwards (Figure 3). A checklist of inland water Sicilian decapod fauna is presented below.

Figure 1.

Occurrence sites in the study area based on 10 × 10 km UTM grid square (zone 33N, datum ED50). Both published and novel sites where decapods species were observed are reported.

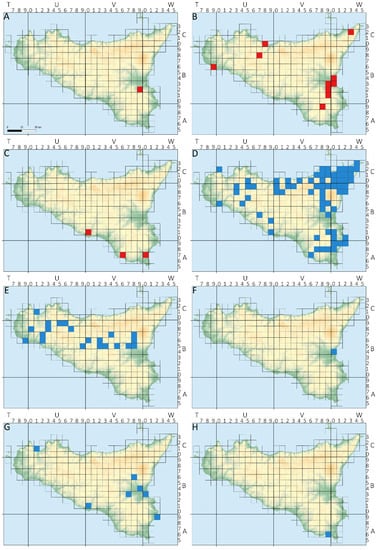

Figure 2.

Occurrence sites of decapod species in Sicily. The blue squares represent the native species occurring in Sicily. Conversely, the red squares represent the alien ones. (A) Cherax destructor; (B) Procambarus clarkii; (C) Callinectes sapidus; (D) Potamon fluviatile; (E) Atyaephyra desmarestii; (F) Palaemon adspersus; (G) P. antennarius; (H) P. elegans.

Figure 3.

Cumulative curves of decapod NIS occurring in Sicily, from the first reported record in 2002 to today, based on “Sites” (red line), “10 × 10 km UTM cells” (green line) and “species richness” (yellow line) data (see also Table 1).

- Infraorder Astacidea Latreille, 1802

- Family Parastacidae Huxley, 1879

- Genus Cherax Erichson, 1846

- Cherax destructor Clark, 1936—Figure 2A

- References

- [22]

- Remarks

- The common yabby Cherax destructor is native to south-eastern Australia and experienced a rapid human-mediated range expansion, colonizing nearly the whole of Australia and Tasmania [23]. Introduced in Europe for aquaculture purposes, the species has been recorded in the wild in Spain [24], France [25,26] and southern Ireland (Julian Reynolds, pers. observ.). In Italy, the common yabby was reported to occur only in Latium [27], where the species disappeared a few years after its discovery possibly due to the crayfish plague Aphanomyces astaci Schikora, 1906 [28], and in Sicily in the Costanzo Stream (province of Syracuse; [22]—one site, one cell—Figure 2A). However, as reported by Vecchioni et al. [29], the species was not observed in the Costanzo Stream in recent years. Further dedicated surveys aimed at confirming its possible local extinction in Sicily are needed.

- Family Cambaridae Hobbs, 1942

- Genus Procambarus Ortmann, 1905

- Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852)—Figure 2B

- References

- [21,22,30,31,32,33]. F.A., A.C., F.P.F., F.P. and G.U., pers. observ.

- Remarks

- The North American red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii is one of the most widespread invasive crayfish species worldwide, and its dramatic impact on native biota is well known [34,35]. In Italy, the species has had an appalling expansion, due to both natural and anthropogenic determinants, since its first introduction in northern Italy [36], with a remarkable invasion rate [35]. To date, the red swamp crayfish has been observed in Sicily in both lotic and lentic water bodies (reported for 21 sites falling into 10 cells—Figure 2B), within a range of 1 to 388 m of altitude. Its local distribution is ascribed to multiple independent introductions [33]. The species has been reported to act as a vector of toxins and heavy metals to higher trophic levels and is considered responsible for biodiversity loss in the invaded ecosystems (see [37] and references therein).

- Infraorder Brachyura Latreille, 1802

- Family Portunidae Rafinesque, 1815

- Genus Callinectes Stimpson, 1860

- Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896—Figure 2C

- References

- [38,39]

- Remarks

- Considered one of the 100 worst invasive alien species that occur in the Mediterranean Sea [40], the Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus, native to the western Atlantic Ocean, has been introduced nearly worldwide [41]. In Italy, the species is widespread and has been reported in the open sea, brackish coastal lagoons, and estuaries [41,42]. In Sicilian inland waters, the species has been recorded with very high densities in coastal ponds at Vendicari [38] and in two rivers (i.e., Irminio and Imera Meridionale [39]) (three sites, three cells—Figure 2C), casting some concerns about its possible impact on the Sicilian pond turtle Emys trinacris Fritz et al. 2005 [43,44], an endemic species occurring both in Vendicari coastal ponds and in the Imera Meridionale river.

- Family Potamidae Ortmann, 1896

- Genus Potamon Savigny, 1816

- Potamon fluviatile (Herbst, 1758 [in Herbst, 1782–1790])—Figure 2D

- References

- [14,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. F.P.F., F.M. and S.R. pers. observ.; R.G., Unpublished data.

- Remarks

- Potamon fluviatile belongs to the subgenus Euthelphusa Pretzmann, 1962, which occurs in the western Mediterranean area and on the Balkan peninsula and includes P. pelops [55] and P. algeriense Bott, 1967 [56,57]. P. fluviatile is the only native freshwater crab species occurring in peninsular Italy and the Sicilian–Maltese archipelago, where it is not homogeneously distributed despite its striking molecular homogeneity [53]. The species is absent in Sardinia and on smaller islands [16,58,59,60]. Its current distribution seems to be due to a natural spread of the species, which occurred about 15,000 years ago [50,53,55]. The freshwater crab is reported for 119 sites falling into 69 cells (Figure 2D), where it colonizes both lotic and lentic water bodies, within an observed range of 16–1200 m in altitude. According to the IUCN red list, the species is assessed as “Near threatened” (https://www.iucnredlist.org/details/134293/0 (accessed on 2 March 2022), [60]) since it has undergone a considerable rarefaction and reduction in abundance within the entire distribution area due to habitat destruction, pollution, and overbuilding [61]. The species is neither mentioned in the “Habitats Directive” (EU Directive 92/43/CEE), nor is it protected at a national level.

- Infraorder Caridae Dana, 1852

- Family Atyidae De Haan, 1849

- Genus Atyaephyra de Brito Capello, 1867

- Atyaephyra desmarestii (Millet, 1831)—Figure 2E

- References

- [14,48,49,62,63,64]. F.M., pers. observ.; R.G., Unpublished data.

- Remarks

- The caridean A. desmarestii is a eurythermal and euryhaline species widespread throughout the Maghreb and western Europe, whereas the closely related shrimp populations occurring in the Balkan Peninsula and in the Middle East belong to different species [65]. In Italy, the species occurs in Friuli Venezia Giulia, in lakes and rivers on the Tyrrhenian watershed (Tuscany, Umbria, Latium, Campania, Basilicata), in Sardinia, and in Sicily [66]. In Sicily, the species has been found between 3 and 620 m a.s.l. in both lentic and lotic water bodies (31 sites, 21 cells—Figure 2E), mainly in oxygen-rich waters with the presence of macrophytes, although the species has also been routinely observed along the muddy shores of artificial reservoirs. Garcia-Muñoz et al. [64] and Christodoulou et al. [65] included some Sicilian specimens in their phylogeographical analyses, showing the absence of a clear geographically based pattern of genetic diversity. According to the IUCN red list, the species has been assessed as being of “Least Concern” (https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/197932/2505632 (accessed on 2 March 2022), [67]).

- Family Palaemonidae Rafinesque, 1815

- Genus Palaemon Weber, 1795

- Palaemon adspersus Rathke, 1836—Figure 2F

- References

- [49]

- Remarks

- The Baltic shrimp Palaemon adspersus is an euryhaline species widely distributed in lagoons, estuaries, and littoral zones of the Mediterranean and Baltic seas. The species was introduced in the Caspian and Aral Sea, and in the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean [19,68]. The only Sicilian population known to date was found by Ferrito [49] in the Simeto River (province of Catania—one site, one cell—Figure 2F), but the species is likely much more widespread in Sicilian estuaries.

- Palaemon antennarius H. Milne Edwards, 1837—Figure 2G

- References

- [14,49,69]. F.M. and L.V., pers. observ.

- Remarks

- This palaemonid species occurs in Albania, Croatia, Greece, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Italy [70]. Palaemon antennarius is a euryhaline species living in both fresh and brackish waters, such as lagoons and estuaries, among the vegetation of lentic or weakly flowing water bodies. In the study area, the distribution of the species is mostly linked to the lower course of rivers of south-eastern Sicily (eight sites, seven cells—Figure 2G), within an altitude range of 1 to 216 m a.s.l. (see Table 1). Jabłońska et al. [69] investigated the phylogeography of the species and ascribed the Sicilian P. antennarius populations to a well-characterised clade inhabiting the Apennine peninsula and Sicily, whereas the Balkan populations currently ascribed to P. antennarius are genetically closer to the congeneric P. minos Tzomos and Koukouras, 2015. According to the IUCN red list, the species has been assessed as being of “Least Concern” (https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/197950/2506191 (accessed on 2 March 2022), [67]).

- Palaemon elegans Rathke, 1836—Figure 2H

- References

- F.M., pers. observ.

- Remarks

- The littoral shrimp Palaemon elegans is a common marine coastal species that inhabits tidal rockpools and seagrasses [17]. The native distribution range of the species includes the eastern Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Black Sea [71]. Recently, the species was also found to occur in the Baltic Sea, where it is considered an invasive species [69]. Although P. elegans is well known in marine coastal areas in Sicily (e.g., [72]), this is the first report of the species in Sicilian inland waters. The littoral shrimp was found in “Pantano Bruno” (province of Ragusa—one site, one cell—Figure 2H), a coastal marsh which, despite its proximity to the sea, has no direct connection with it. When the species was collected (16 December 2006), the water temperature was 13.4 °C and the electrical conductivity 18,390 µS/cm.

Table 1.

List of the novel and published localities of the decapods occurring in Sicily. Geographical decimal coordinates are reported according to the WGS84 datum. UTM coordinates are reported by 10 × 10 km grid square (zone 33N, datum ED50).

Table 1.

List of the novel and published localities of the decapods occurring in Sicily. Geographical decimal coordinates are reported according to the WGS84 datum. UTM coordinates are reported by 10 × 10 km grid square (zone 33N, datum ED50).

| Province | Locality | Latitude N | Longitude E | Elevation (m a.s.l.) | UTM | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atyaephyra desmarestii | |||||||

| Agrigento | Lago Arancio | 37.636616 | 13.056858 | 178 | UB26 | 2007 | F.M. |

| Caltanissetta | Bompensiere, T. Belici o F. Salito | - | - | 200 | UB95 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Caltanissetta | M. Capodarso, F. Salso | - | - | 300 | VB25 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Caltanissetta | Ponte Cinque Archi | 37.608363 | 14.131327 | 340 | VB26 | 2007 | [63] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Barcavecchia | - | - | 178 | VB86 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte dei Saraceni | 37.700852 | 14.799691 | 362 | VB87 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Pietralunga | 37.575195 | 14.865077 | 92 | VB85 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Paternò, F. Simeto | - | - | 65 | VB85 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | 10 km W Enna | - | - | - | VB35 | 1981 | [62] |

| Enna | Catenanuova, F. Dittaino/S.S. 192 | - | - | 128 | VB75 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | F. Dittaino, b. Staz. Dittaino | - | - | 240 | VB55 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | Nicosia, F. Salso b. Brücke S.S. 117 | - | - | 550 | VB47 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | Nicosia, T. Mandre, o. Fitto di Sperlinga | - | - | 550 | VB47 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | Nicosia, T. Mandre, o. Fitto di Sperlinga | - | - | 550 | VB47 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | Villadoro T. Mandre, o. Mdg. T. Feliciosa | - | - | 620 | VB47 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Enna | Villadoro T. Mandre, u. Poggio Pioppo | - | - | 590 | VB47 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Fiume San Leonardo | - | - | 170 | UB78 | 1990 | [48] |

| Palermo | Foce San Bartolomeo | - | - | - | UC11 | 1986 | [14] |

| Palermo | Foce San Bartolomeo | 38.021531 | 12.904877 | 3 | UC11 | 2007 | F.M. |

| Palermo | Gorgo del Drago | 37.901121 | 13.412594 | 340 | UB69 | 1990 | [48] |

| Palermo | Lago Garcia | 37.787894 | 13.098285 | 193 | UB38 | 2009 | F.M |

| Palermo | Lago Scanzano | 37.911915 | 13.370565 | 518 | UB59 | 2007 | F.M. |

| Palermo | Marianopoli, T. Belici/Staz. M.’poli | - | - | 330 | VB06 | 1987 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Poggioreale, F. Belice | - | - | 100 | UB27 | 1986 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Ponte Calatrasi | 37.844329 | 13.119190 | 201 | UB39 | 2009 | F.M. |

| Palermo | S.C. Villarmosa, F. Imera o P. 5 Archi | - | - | 350 | VB26 | 1986 | R.G. |

| Palermo | T. Belici u. Brücke bei, Staz. Marianopoli | - | - | 330 | VB06 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Torrente Frattina | 37.861300 | 13.303000 | 370 | UB59 | 2004–2008 | [64] |

| Trapani | Castelvetrano, F. Grande/C.da Pozzillo | -- | - | 90 | UB08 | 1986 | R.G. |

| Trapani | Gorgo Alto | 37.612702 | 12.649468 | 3 | TB96 | 2014 | F.M. |

| Trapani | S. Ninfa F. Grande, u. Borgo di Buturro | - | - | 115 | UB08 | 1986 | R.G. |

| Callinectes sapidus | |||||||

| Agrigento | Fiume Imera Meridionale | 37.138833 | 13.916907 | 8 | VB01 | 2021 | [39] |

| Ragusa | Fiume Irminio | 36.775803 | 14.596793 | 4 | VA67 | 2021 | [39] |

| Siracusa | RNO “Oasi Faunistica di Vendicari” | 36.787487 | 15.094653 | 1 | WA07 | 2020 | [38] |

| Cherax destructor | |||||||

| Siracusa | Torrente Costanzo | 37.257818 | 14.920217 | 52 | VB92 | 2017 | [22] |

| Palaemon adspersus | |||||||

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Primosole | 37.400180 | 15.064910 | 5 | WB04 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Palaemon antennarius | |||||||

| Agrigento | Fiume Salso (Fiume Imera Meridionale) | 37.157800 | 13.926400 | 13 | VB01 | 2016 | [69] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto | 37.604500 | 14.828500 | 117 | VB86 | 2016 | [69] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Giarretta | 37.457342 | 14.915137 | 22 | VB94 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Foce del Fiume Simeto | 37.399878 | 15.086196 | 1 | WB03 | 1985 | [14] |

| Catania | Stagno agricolo Palagonia | 37.350584 | 14.676467 | 152 | VB73 | 2011 | F.M. |

| Enna | Fiume Salso, Masseria d’Aragona | 37.647130 | 14.772840 | 216 | VB86 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Palermo | Foce San Bartolomeo | 38.023677 | 12.906666 | 5 | UC11 | 1990 | [14] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Ciane | 37.042005 | 15.234638 | 4 | WA29 | 2021 | F.M.; L.V. |

| Palaemon elegans | |||||||

| Ragusa | Pantano Bruno | 36.697897 | 14.986846 | 1 | VA96 | 2006 | F.M. |

| Potamon fluviatile | |||||||

| Agrigento | Fiume Sosio | - | - | - | UB57 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Agrigento | Fiume Sosio, Chiusa Sclafani | 37.646213 | 13.274429 | 227 | UB46 | 2015 | F.P.F. |

| Agrigento | Lago San Giovanni | 37.309064 | 13.766020 | 309 | UB93 | 2020 | S.R. |

| Agrigento | Vallone di Gaffe | 37.166953 | 13.826678 | 133 | UB91 | 2021 | S.R. |

| Agrigento | Vallone Ponte | - | - | - | UB74 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Alcantara | - | - | - | VB99 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Alcantara | - | - | - | WB19 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Alcantara | - | - | - | WB28 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Dirillo | 37.121792 | 14.720373 | 333 | VB70 | 2021 | F.P.F. |

| Catania | Fiume Fiumefreddo | - | - | - | WB18 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Fiumefreddo | - | - | - | WB28 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Flascio | - | - | - | VB89 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Salso, Masseria d’Aragona | 37.647130 | 14.772840 | 216 | VB86 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto | - | - | - | VB85 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto | - | - | - | VB87 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto | - | - | - | VB88 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Barcavecchia | 37.643436 | 14.810196 | 178 | VB86 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Giarretta | 37.457342 | 14.915137 | 22 | VB94 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Passo Paglia | 37.767350 | 14.799940 | 466 | VB88 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Pietralunga | 37.575195 | 14.865077 | 92 | VB85 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Leucatìa | - | - | - | WB05 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Presso Randazzo | 37.903491 | 14.937369 | 817 | VB99 | 2018 | F.P.F. |

| Catania | S. Maria di Licodìa | - | - | - | VB96 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Torrente Cutò, Vitalone | 37.864230 | 14.771510 | 750 | VB79 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Catania | Torrente Saracena | - | - | - | VB89 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Catania | Torrente Saracena, Chiusitta | - | - | 1200 | VB89 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Messina | Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto | - | - | - | WC12 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Faidda | 37.811389 | 14.615833 | 792 | VB68 | 2013 | [52] |

| Messina | Fiumara Corsari | - | - | - | WC43 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Elicona | - | - | - | WC01 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Fantina | - | - | - | WC10 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Floripotema | - | - | - | WC21 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Floripotema | - | - | - | WC22 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Marmora | - | - | - | WC43 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Niceto | - | - | - | WC32 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara of Agrò | - | - | - | WC20 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Rodia | - | - | - | WC43 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Santa Lucia | - | - | - | WC21 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Santa Venera | - | - | - | WC11 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Sinagra | - | - | - | VC81 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Tarantonio | - | - | - | WC43 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiumara Tono | - | - | - | WC43 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiume Fiumedinisi | - | - | - | WC30 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiume S. Paolo | - | - | - | WB09 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiume S. Paolo | - | - | - | WB19 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Fiume Simeto, Ponte Bolo | 37.833160 | 14.794980 | 622 | VB88 | 1988–1989 | [49] |

| Messina | Fiume Tusa | 37.936647 | 14.301381 | 175 | VB39 | 2013 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Fonte Camaro | - | - | - | WC42 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Giardini Naxos, F. Alcantara | - | - | 20 | WB28 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Messina | Mistretta | 37.952067 | 14.375715 | 276 | VC40 | 2015 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Moio Alcantare, F. Alcantara o. Brücke | - | - | 525 | WB09 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Messina | Peloritani, Altolia, Bach o. Altolia | - | - | 315 | WC31 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Messina | Stretta di Longi | 38.049757 | 14.763471 | 241 | VC71 | 2013 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Torrente Briga | - | - | - | WC31 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Gualtieri | - | - | - | WC21 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Gualtieri | - | - | - | WC22 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Licopeti, presso Malabotta | 37.947890 | 15.007134 | 739 | WC00 | 2016 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Torrente Mela | - | - | - | WC21 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Petrolo | - | - | - | WB29 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Roccella | - | - | - | WB09 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente San Basilio | - | - | - | VC80 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Torrente Sinagra | 38.069470 | 14.871745 | 317 | VC81 | 2020 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Torrente Timeto, Patti | 38.076461 | 14.971427 | 222 | VC91 | 2011 | F.P.F. |

| Messina | Torrente Tripi | - | - | - | WC01 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Vallone Canneto | - | - | - | VC40 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Vallone Mascarino | - | - | - | VC60 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Vallone Munofu | - | - | - | WB29 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Vallone San Nicola | - | - | - | WC21 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Messina | Viadotto Ponte Naso, Torrente Sinagra | 38.145044 | 14.803335 | 16 | VC82 | 2013 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Castelbuono | 37.950334 | 14.094915 | 194 | VC20 | 2015 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Fiume Pollina | 37.914406 | 14.147270 | 200 | VB29 | 2018 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Fiume Pollina | - | - | - | VC20 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Palermo | Gole del Frattina | 37.865758 | 13.301096 | 463 | UB59 | 2016 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Gole di Tiberio | 37.954672 | 14.148456 | 89 | VC20 | 2013 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Gorgo del Drago | 37.901121 | 13.412594 | 340 | UB69 | 1990 | [48] |

| Palermo | Imera Settentrionale | - | - | - | VB09 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Palermo | Imera Settentrionale | 37.860660 | 13.894776 | 180 | VB09 | 2017 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Imera Settentrionale | 37.858300 | 13.897000 | 174 | VB09 | 2014 | [53] |

| Palermo | Lago di Piana degli Albanesi | 37.971015 | 13.302485 | 607 | UC50 | 2021 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Madonie F. Pollina, o. Mdg. F. Buonanotte | - | - | 50 | VC20 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Madonie, Castelbuono, T. Vicaretto/S.S. 286 | - | - | 320 | VB29 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Madonie, Castelbuono, Vne. Dei Mulini/S.S. 286 | - | - | 350 | VB29 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Madonie, Pollina-Tal, T. Grosso u. C. Parissi | - | - | 350 | VB29 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Palermo | Polizzi Generosa | 37.812536 | 13.999416 | - | VB18 | 2004 | [50] |

| Palermo | Scillato | 37.860412 | 13.895252 | 177 | VB09 | 2017 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Torrente Fichera | - | - | - | VB08 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Palermo | Torrente Frattina | - | - | - | UB59 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Palermo | Torrente Frattina | 37.861300 | 13.303000 | 370 | UB59 | 2014 | [53] |

| Palermo | Torrente Giardinello | 37.915746 | 14.133376 | 234 | VB29 | 2017 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Torrente presso Fiume Pollina | 37.915535 | 14.133192 | 237 | VB29 | 2018 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Torrente Roccella, presso Collesano | 37.946262 | 13.923581 | 214 | VC00 | 2017 | F.P.F. |

| Palermo | Torrente Vicaretto | - | - | - | VB29 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Palermo | Vallone Nocilla | - | - | - | UB69 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Ragusa | Fiume Irminio | 36.788600 | 14.602000 | 18 | VA67 | 2014 | [53] |

| Ragusa | Ragusa | 36.924437 | 14.722580 | - | VA78 | 2005 | [50] |

| Ragusa | Torrente Tellesimo | 36.948889 | 14.850833 | 338 | VA88 | 2011–2012 | [54] |

| Siracusa | Cava Carosello | 36.939827 | 15.019083 | 324 | WA08 | 2019 | S.R. |

| Siracusa | Cava dei Molini | - | - | - | WB01 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Anapo | - | - | - | WB00 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Cassibile | 36.988200 | 15.026800 | 406 | WA09 | 2014 | [53] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Cassibile | - | - | - | WA19 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Ciane | - | - | - | WA29 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Ciane | - | - | - | WB20 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Fiume Tellaro | 36.883700 | 14.950400 | 95 | VA98 | 2014 | [53] |

| Siracusa | Fonte Paradiso | - | - | - | VB91 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | Iblei, Mte. S. Venere, Contr. Ceusa, Quelle | - | - | 520 | VB91 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Siracusa | Iblei, Sortino, F. Anapo/Staz. ENEL | - | - | 163 | WB01 | 1985 | R.G. |

| Siracusa | Sortino | 37.152035 | 15.037073 | 250 | WB01 | 2012 | F.P.F. |

| Siracusa | Sortino | 37.147198 | 15.052666 | 178 | WB01 | 2012 | F.P.F. |

| Siracusa | Sortino, Fiume Anapo | 37.137540 | 15.039070 | 202 | WB01 | 2012 | F.P.F. |

| Siracusa | Torrente Calcinara | 37.140200 | 15.029100 | 264 | WB01 | 2014 | [53] |

| Siracusa | Valle Pantalica | - | - | - | WB00 | 1990 | [47] |

| Siracusa | Vallone Zappardino | - | - | - | VC92 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Siracusa | - | - | - | - | WA08 | 1998 | [45] |

| Trapani | C.da Acci, RNO “Zingaro” | - | - | - | UC02 | 1992 | [46] |

| Trapani | C.da Acci, RNO “Zingaro” | 38.123697 | 12.768234 | 577 | UC02 | 2004 | F.M. |

| Trapani | Fiume Belice | - | - | - | UB38 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Trapani | Fiume Belice | - | - | - | UB39 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Trapani | Fiume Modione | - | - | - | UB06 | 2006–2010 | [51] |

| Procambarus clarkii | |||||||

| Catania | Canale Buttaceto | 37.437703 | 15.047918 | 7 | WB04 | 2017 | [33] |

| Catania | Fiume Gornalunga | 37.388865 | 15.078404 | 2 | WB03 | 2016 | [22] |

| Catania | Foce Fiume Simeto | 37.400072 | 15.064382 | 1 | WB03 | 2016 | [22] |

| Messina | Pantani di Venetico | 38.212611 | 15.364333 | 6 | WC32 | 2017 | [33] |

| Messina | Venetico, pozze artificiali | 38.195686 | 15.384248 | 124 | WC32 | 2015 | [22] |

| Palermo | Fiume San Leonardo | 37.842270 | 13.562021 | 243 | UB78 | 2018 | F.A.; G.G.; F.P.F.; F.P. |

| Palermo | Lago Rosamarina | 37.938619 | 13.635133 | 170 | UC80 | 2012 | [30] |

| Ragusa | Fiume Irminio | 36.996840 | 14.778049 | 388 | VA89 | 2017 | [33] |

| Ragusa | Lago Santa Rosalia | 36.974803 | 14.776731 | 374 | VA89 | 2015 | [22] |

| Siracusa | Fiume San Leonardo | 37.342701 | 15.081742 | 3 | WB03 | 2015 | [22] |

| Siracusa | Fiume San Leonardo | 37.343166 | 15.088748 | 3 | WB03 | 2017 | [33] |

| Siracusa | Lentini, canale | 37.282435 | 14.970489 | 19 | VB92 | 2018 | A.C. |

| Siracusa | Lentini, stagno agricolo | 37.360270 | 14.913601 | 20 | VB93 | 2017 | G.U. |

| Siracusa | Torrente Costanzo | 37.252467 | 14.912453 | 60 | VB92 | 2016 | [22] |

| Siracusa | Torrente Margi | 37.214115 | 14.891158 | 192 | VB91 | 2015 | [22] |

| Trapani | Lago di Murana | 37.626475 | 12.634279 | 4 | TB96 | 2017 | [33] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.620374 | 12.641136 | 4 | TB96 | 2012 | [31] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.611327 | 12.651033 | 3 | TB96 | 2012 | [31] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.609080 | 12.655051 | 2 | TB96 | 2002 | [21] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.620374 | 12.641136 | 6 | TB96 | 2012 | [32] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.612475 | 12.649554 | 3 | TB96 | 2012 | [32] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.611327 | 12.651033 | 3 | TB96 | 2012 | [32] |

| Trapani | RNI “Lago Preola e Gorghi Tondi” | 37.609080 | 12.655051 | 2 | TB96 | 2012 | [32] |

4. Discussion

The unpublished data and the critical review of the existing literature made it possible to produce an updated checklist and distribution maps for Sicilian decapod inland water fauna, including five native (i.e., Atyaephyra desmarestii, Palaemon adspersus, P. antennarius, P. elegans, and Potamon fluviatile), and three alien (Callinectes sapidus, Cherax destructor and Procambarus clarkii) species, i.e., three brackish water species were added to the list reported by Hupalo et al. [73] for the Island. Among the decapods reported in the present work, some are primarily marine species, i.e., Callinectes sapidus and Palaemon elegans, which are known to be able to colonize transitional or inland water environments (e.g., [41,72,74]). Conversely, we excluded from the current review those species whose occurrence in inland waters is only occasional and limited to river mouths and coastal lagoons in direct connection to the sea (e.g., [75,76]).

Overall, the retrieved data show a good coverage of the Sicilian territory (about 27%, i.e., 93 cells occupied by at least one record out of 343 total cells), with the significant exceptions of the area that includes the “Piana di Gela” and “Monti Erei” and of the western coastal area of the island, where no records are available despite the occurrence of suitable habitats. No decapods are known to date for the small circum-Sicilian islands, which is possibly due to the scarcity of the surface permanent hydrographical network occurring there. However, it should be considered that the vast majority of the records pertains to large-bodied, charismatic species (P. fluviatile, 69 cells, P. clarkii, 10 cells), so that the actual distribution of palaemonid and atyid shrimps in Sicily is certainly underestimated. It is also worth stressing that some of the occurrence data should be taken with caution, as they could be the result of erroneous identifications, especially when the occurrence of a species was reported without iconographic support in the frame of papers not focused on crustaceans. For example, the report of Palaemon antennarius from “Gorgo del Drago” (province of Palermo, see [48]) is probably due to a misidentification of Atyaephyra desmarestii (F.M., pers. observ.).

Based on available data, the atyid Atyaephyra desmarestii seems to be rather frequent in north-western and central Sicily but absent in the south-eastern part of the island. Conversely, the distribution of the palaemonid shrimp Palaemon antennarius appears to be scarcely represented in northern and western Sicily, with the single record for Trapani province in need for being validated, and more frequent in south-eastern Sicily. Further studies on the distribution of caridean species in Sicilian inland waters are to evaluate whether there is a complementary distribution pattern between these two species, or the observed pattern is rather due to the non-representativeness of currently available data (see Figure 2E,F and Table 1).

The occurrence of non-indigenous species (NIS) represents a significant risk for native biota both through direct impact and parasite spill-over [37,77,78,79]. Introduced decapods are considered among the most concerning NIS in inland waters [80]. In Sicily, the current impact of NIS is exerted mainly on permanent water bodies, whereas temporary ones have been to date less affected [8]; moreover, Procambarus clarkii, Cherax destructor, and Callinectes sapidus are to date mostly limited to low altitudes and lowland stretches of rivers (with few exceptions, see Table 1). Conversely, Atyaephyra desmarestii and Potamon fluviatile, i.e., the most widespread native decapods occurring in Sicily, have most of their populations currently located in the upper parts of the river watersheds. Accordingly, a spatial segregation between native and non-native species seems to be in place. Nevertheless, in some cases, native and non-native species co-occur, as for the crabs Callinectes sapidus and Potamon fluviatile, coexisting in the Irminio river (province of Ragusa).

The trend observed in Sicily for NIS is rather worrying. Based on the available evidence, the first finding of an alien decapod species [21] was not followed by its spreading on the island nor by the introduction of other species for about ten years. Later, from 2012 onwards, a steep rate of increase for both the number of alien species and their local distribution was observed (Figure 3). Such an increase in the number of NIS occurring on the island and their local distribution was most likely mediated by several drivers, such as the ease of buying species on the global market through websites, to limited environmental awareness, and to the current absence of a proper legislation actively regulating the amateur and commercial breeding of species with high invasive potential. Inland waters are facing several threats causing significant risks for their biota [4,81], especially in arid and semi-arid regions and insular habitats [3,82]. To date in Sicily, the biota of permanent water bodies is scarcely known, and the basic knowledge needed to preserve or manage them is limited. Moreover, in contrast to what happens in other Italian regions (e.g., Abruzzo, Emilia Romagna, and Tuscany, see [83], no specific legislation on the protection of native decapod crustaceans is currently in force in Sicily. We hope that the present work might be a useful tool for stressing the need for further, more detailed, surveys aimed at filling current knowledge gaps regarding the presence and distribution of decapod species in Sicilian inland waters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M. and M.A.; methodology, F.P.F., F.S. and L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.V. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

All the people who provided unpublished data on decapod distribution in Sicily (see Table 1) are acknowledged for their support. Reinhard Gerecke (University of Tübingen, Germany) is kindly acknowledged for sharing unpublished data and for the stimulating discussions on Sicilian inland water fauna.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.R.; Knowles, L.L. Habitat corridors facilitate genetic resilience irrespective of species dispersal abilities or population sizes. Evol. Appl. 2015, 8, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epele, L.B.; Grech, M.G.; Williams-Subiza, E.A.; Stenert, C.; McLean, K.; Greig, H.S.; Maltchik, L.; Pires, M.M.; Bird, M.S.; Boissezon, A.; et al. Perils of life on the edge: Climatic threats to global diversity patterns of wetland macroinvertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F. Biological invasions in inland waters: An overview. In Biological Invaders in Inland Waters: Profiles, Distribution, and Threats; Gherardi, F., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Matzke, N.; Tomiya, S.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Swartz, B.; Quental, T.B.; Marshall, C.; McGuire, J.L.; Lindsey, E.L.; Maguire, K.C.; et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhead, N.M. Extinction rates in north American freshwater fishes, 1900-2010. Bioscience 2012, 62, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Brucet, S.; Naselli-Flores, L.; Papastergiadou, E.; Stefanidis, K.; Nõges, T.; Nõges, P.; Attayde, J.L.; Zohary, T.; Coppens, J.; et al. Ecological impacts of global warming and water abstraction on lakes and reservoirs due to changes in water level and related changes in salinity. Hydrobiologia 2015, 750, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli-Flores, L.; Marrone, F. Different invasibility of permanent and temporary waterbodies in a semiarid Mediterranean Island. Inl. Waters 2019, 9, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C.; Finlayson, C.M. Extent, regional distribution and changes in area of different classes of wetland. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2018, 69, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantonati, M.; Poikane, S.; Pringle, C.M.; Stevens, L.E.; Turak, E.; Heino, J.; Richardson, J.S.; Bolpagni, R.; Borrini, A.; Cid, N.; et al. Characteristics, main impacts, and stewardship of natural and artificial freshwater environments: Consequences for biodiversity conservation. Water 2020, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, G.; Stoch, F.; Marrone, F. An annotated checklist and bibliography of the Diaptomidae (Copepoda, Calanoida) of Italy, Corsica, and the Maltese islands. J. Limnol. 2021, 80, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, F.; Vecchioni, L. The genus Daphnia in Sicily and Malta (Crustacea, Branchiopoda, Anomopoda). In Life on Islands. 1. Biodiversity in Sicily and Surrounding Islands. Studies Dedicated to Bruno Massa; La Mantia, T., Badalamenti, E., Carapezza, A., Lo Cascio, P., Troia, A., Eds.; Edizioni Danaus: Palermo, Italy, 2020; pp. 105–123. ISBN 978-88-97603-26-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, V.; Marrone, F.; Martens, K.; Rossetti, G. An updated checklist of recent ostracods (Crustacea: Ostracoda) from inland waters of Sicily and adjacent small islands with notes on their distribution and ecology. Eur. Zool. J. 2020, 87, 714–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, S.; Stoch, F. Checklist and distribution of the Italian fauna: 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species. Memorie del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona, 2.Serie, Sezione Scienze della Vita 17, with CD-ROM; Comune di Verona: Verona, Italy, 2006; Volume 91, ISBN 8889230096. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, W.D. Freshwater Crustacea; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1974; pp. 63–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froglia, C. Decapodi (Crustacea Decapoda) (Vol. 4); Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Verona, Stamperia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ortegón, E.; Cuesta, J.A. An illustrated key to species of Palaemon and Palaemonetes (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) from European waters, including the alien species Palaemon macrodactylus. In Proceedings of the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 86, pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Holdich, D.M.; Vigneux, E. Key to crayfish in Europe. In Atlas of Crayfish in Europe; Souty-Grosset, C., Holdich, D., Noël, P., Reynolds, J., Haffner, P., Eds.; Patrimoines naturels (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle): Paris, France, 2006; pp. 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ortegón, E.; Sargent, P.; Pohle, G.; Martinez-Lage, A. The Baltic prawn Palaemon adspersus Rathke, 1837 (Decapoda, Caridea, Palaemonidae): First record, possible establishment, and illustrated key of the subfamily Palaemoninae in northwest Atlantic waters. Aquat. Invasions 2015, 10, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2022. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- D’Angelo, S.; Lo Valvo, M. On the presence of the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii in Sicily. Nat. Sicil. 2003, 27, 325–327. [Google Scholar]

- Deidun, A.; Sciberras, A.; Formosa, J.; Zava, B.; Insacco, G.; Corsini-Foka, M.; Crandall, K.A. Invasion by non-indigenous freshwater decapods of Malta and Sicily, central Mediterranean Sea. J. Crustac. Biol. 2018, 38, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, R.B. New records and review of the translocation of the yabby Cherax destructor into eastern drainages of New South Wales, Australia. Aust. Zool. 2014, 37, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedia, I.; Miranda, R. Review of the state of knowledge of crayfish species in the Iberian Peninsula. Limnetica 2013, 29, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, T.; Collas, M.; Grandjean, F.; Poulet, N. Premier signalement de Cherax destructor en milieu naturel en France (Bretagne). 2019. Available online: http://especes-exotiques-envahissantes.fr (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Collas, M. Écrevisses exotiques envahissantes en France. Le rythme des introductions en milieu naturel s’accélère. Le Courr. la Nat. 2020, 325, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Scalici, M.; Chiesa, S.; Gherardi, F.; Ruffini, M.; Gibertini, G.; Marzano, F.N. The new threat to Italian inland waters from the alien crayfish “gang”: The Australian Cherax destructor Clark, 1936. Hydrobiologia 2009, 632, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Scalici, M.; Inghilesi, A.F.; Aquiloni, L.; Pretto, T.; Monaco, A.; Tricarico, E. The red alien vs. the blue destructor: The eradication of Cherax destructor by Procambarus clarkii in Latium (Central Italy). Diversity 2018, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Marrone, F.; Chirco, P.; Arizza, V.; Tricarico, E.; Arculeo, M. To be, or not to be invasive: The case of the crayfish Cherax spp. in Italy (Crustacea, Parastacidae). BioInvasions Rec. 2022. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leo, C.; Faraone, F.P.; Valvo, M. Lo A new record of the red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Crustacea, Cambaridae), in Sicily, Italy. Biodivers. J. 2014, 5, 425–428. [Google Scholar]

- Bellante, A.; Maccarone, V.; Buscaino, G.; Buffa, G.; Filiciotto, F.; Traina, A.; Del Core, M.; Mazzola, S.; Sprovieri, M. Trace element concentrations in red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) and surface sediments in Lake Preola and Gorghi Tondi natural reserve, SW Sicily. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccarrone, V.; Filiciotto, F.; Buffa, G.; Di Stefano, V.; Quinci, E.M.; de Vincenzi, G.; Mazzola, S.; Buscaino, G. An invasive species in a protected area of Southern Italy: The structure, dynamics and spatial distribution of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Turkish J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, F.P.; Giacalone, G.; Canale, D.E.; D’Angelo, S.; Favaccio, G.; Garozzo, V.; Giancontieri, G.L.; Isgrò, C.; Melfi, R.; Morello, B.; et al. Tracking the invasion of the red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Decapoda Cambaridae) in Sicily: A “citizen science” approach. Biogeographia 2017, 32, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquiloni, L.; Tricarico, E.; Gherardi, F. Crayfish in Italy: Distribution, threats and management. Int. Aquat. Res. 2010, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Parrino, E.; Ficetola, G.F.; Manenti, R.; Falaschi, M. Thirty years of invasion: The distribution of the invasive crayfish Procambarus clarkii in Italy. Biogeographia 2020, 35, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mastro, G.B. Sull’acclimatazione del gambero della Louisiana Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) nelle acque dolci italiane (Crustacea: Decapoda: Cambaridae). Pianura 1992, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, F.; Naselli-Flores, L. A review on the animal xenodiversity in Sicilian inland waters (Italy). Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 2015, 6, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Di Martino, V.; Stancanelli, B. Mass mortality event of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896 in a coastal pond of the protect area of Vendicari in summer 2020 (S-E Sicily). J. Sea Res. 2021, 172, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Russotto, S.; Arculeo, M.; Marrone, F. On the occurrence of the invasive Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae) in Sicilian inland waters Nat. Hist. Sci. 2022, accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Streftaris, N.; Zenetos, A. Alien marine species in the Mediterranean—the 100 “worst invasives” and their impact. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2006, 7, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Bardelli, R.; Zenetos, A. A global occurrence database of the Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancinelli, G.; Chainho, P.; Cilenti, L.; Falco, S.; Kapiris, K.; Katselis, G.; Ribeiro, F. The Atlantic blue crab Callinectes sapidus in southern European coastal waters: Distribution, impact and prospective invasion management strategies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchioni, L.; Marrone, F.; Arculeo, M.; Fritz, U.; Vamberger, M. Stand out from the crowd: Small-scale genetic structuring in the endemic Sicilian pond turtle. Diversity 2020, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Cicerone, A.; Scardino, R.; Arizza, V.; Arculeo, M.; Marrone, F. Sicilians are not easily hooked! first assessment of the impact of recreational fishing on the endemic Sicilian pond turtle Emys trinacris (Testudines, Emydidae). Herpetol. Notes 2020, 13, 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Pretzmann, G. Über einige Süsswasserkrabben in italienischen Sammlungen. Anzeiger Math.-Naturw. Kl. öst. Akad. Wiss. 1980, 1980, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- VV.AA. La Riserva Naturale Orientata dello “Zingaro”; Azienda Foreste Demaniali della Regione Siciliana: Palermo, Italy, 1992; pp. 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, M.A.; Migliore, L. I macroinvertebrati come indicatori ecologici nel mappaggio di qualità del fiume Anapo (Siracusa, Sicilia). Nat. Sicil. 1992, 16, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zava, B.; Violani, C. Contributi alia conoscenza dell’ittiofauna delle acque interne siciliane. I. Sulla presenza in Sicilia di Salaria fluviatilis (Asso, 1801) (Pisces, Blennidae). Boll. del Mus. Reg. Sci. Nat. Torino 1991, 9, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrito, V. Les macroinvertébrés benthiques de la rivière Simeto (Sicile) et de quelques-uns de ses affluents. Ann. Limnol. 1994, 30, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, R.; Pfenninger, M.; Fratini, S.; Scalici, M.; Streit, B.; Schubart, C.D. Disjunct distribution of the Mediterranean freshwater crab Potamon fluviatile-natural expansion or human introduction? Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.; Restivo, S. New data on distribution of Potamon fluviatile (Decapoda, Brachyura) in Sicily (Southern Italy). Ital. J. Freshw. Ichthyol. 2014, 1, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Duchi, A.; Divincenzo, S. Prime indagini ittiologiche nel torrente Sant’Elia (Troina, EN, Sicilia, Italia). Ital. J. Freshw. Ichthyol. 2017, 4, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchioni, L.; Deidun, A.; Sciberras, J.; Sciberras, A.; Marrone, F.; Arculeo, M. The late Pleistocene origin of the Italian and Maltese populations of Potamon fluviatile (Malacostraca: Decapoda): Insights from an expanded sampling of molecular data. Eur. Zool. J. 2017, 84, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, A. Prove di censimento di Salmo cettii Rafinesque-Schmaltz, 1810, tramite faretto e maschera e boccaglio in Sicilia sud-orientale (Ragusa): Attività e risultati preliminari. Ital. J. Freshw. Ichthyol. 2020, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jesse, R.; Schubart, C.D.; Klaus, S. Identification of a cryptic lineage within Potamon fluviatile (Herbst) (Crustacea:Brachyura:Potamidae). Invertebr. Syst. 2010, 24, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandis, D.; Storch, V.; Turkay, M. Taxonomy and zoogeography of the freshwater crabs of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East (Crustacea, Decapoda, Potamidae). Senckenb. Biol. 2000, 80, 5–56. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, F.; Vecchioni, L.; Deidun, A.; Mabrouki, Y.; Arab, A.; Arculeo, M. DNA taxonomy of the potamid freshwater crabs from Northern Africa (Decapoda, Potamidae). Zool. Scr. 2020, 49, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. Il granchio di fiume Potamon edule (Latr.) in Liguria. Doriana Suppl. Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. G. Doria. 1953, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pretzmann, G. Die Gattung Potamon Savigny in der Sammlung des Museo Civico di Storia Naturale “G. Doria” in Genua. Estratto Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Genova 1984, 85, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cumberlidge, N. Potamon Fluviatile; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: E.T134293A3933275. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/134293/3933275 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Vella, A.; Vella, N. First population genetic structure analysis of the freshwater crab Potamon fluviatile (Brachyura: Potamidae) reveals fragmentation at small geographical scale. Genet. Aquat. Org. 2020, 4, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzmann, G.; Pauler, K. Atyaephyra desmarestii (Millet 1831) in Österreich. Anzeiger Math.-Naturw. Kl. öst. Akad. Wiss. 1981, 8, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Duca, R.; Marrone, F. Conferma della presenza di Aphanius fasciatus (Valenciennes, 1821) (Cyprinodontiformes Cyprinodontidae) nel bacino indrografico del fiume Imera Meridionale (Sicilia). Nat. Sicil. 2009, 33, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- García-Muñoz, J.E.; Rodríguez, A.; García-Raso, J.E.; Cuesta, J.A. Genetic evidence for cryptic speciation in the freshwater shrimp genus Atyaephyra de Brito Capello (Crustacea, Decapoda, Atyidae). Zootaxa 2009, 2025, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, M.; Antoniou, A.; Magoulas, A.; Koukouras, A. Revision of the freshwater genus Atyaephyra (Crustacea, Decapoda, Atyidae) based on morphological and molecular data. Zookeys 2012, 229, 53–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, G.; Cianfanelli, S. Distribuzione di Atyaephyra desmarestii (Millet, 1831) e Palaemonetes antennarius (H. Milne Edwards, 1837)(Crustacea: Decapoda) in Toscana e Liguria. In Proceedings of the Codice Armonico, Quarto Congresso di Scienze naturali, ambiente toscano. Edizioni ETS, Pisa, Italy; 2012; pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- De Grave, S. Atyaephyra desmarestii; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: E.T197932A2505632. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T197932A2505632.en (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Grabowski, M. Rapid colonization of the Polish Baltic coast by an Atlantic palaemonid shrimp Palaemon elegans Rathke, 1837. Aquat. Invasions 2006, 1, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, A.; Navarro, N.; Laffont, R.; Wattier, R.; Pešić, V.; Zawal, A.; Vukić, J.; Grabowski, M. An integrative approach challenges species hypotheses and provides hints for evolutionary history of two Mediterranean freshwater palaemonid shrimps (Decapoda: Caridea). Eur. Zool. J. 2021, 88, 900–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, M.; Anastasiadou, C.; Jugovic, J.; Tzomos, T. Freshwater shrimps (Atyidae, Palaemonidae, Typhlocarididae) in the broader mediterranean region: Distribution, life strategies, threats, conservation challenges and taxonomic issues. In A Global Overview of the Conservation of Freshwater Decapod Crustaceans; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, T.; Pfaller, M.; Schubart, C.D. Phylogeography of the littoral prawn species Palaemon elegans (Crustacea: Caridea: Palaemonidae) across the Mediterranean Sea unveils disparate patterns of population genetic structure and demographic history in the two sympatric genetic types II a. Mar. Biodivers. 2018, 48, 1979–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, C.; Arculeo, M. The marine Crustacea Decapoda of Sicily (central Mediterranean Sea): A checklist with remarks on their distribution. Ital. J. Zool. 2003, 70, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupało, K.; Stoch, F.; Karaouzas, I.; Wysocka, A.; Rewicz, T.; Mamos, T.; Grabowski, M. Freshwater Malacostraca of the Mediterranean Islands—Diversity, Origin, and Conservation Perspectives. In Recent Advances in Freshwater Crustacean Biodiversity and Conservation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 139–220. ISBN 9781003139560. [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbe, S.; Lo Piccolo, M.; Scaduto, G. Forty-seven years later: The blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea Decapoda Portunidae) reappears in the Strait of Messina (Sicily, Italy). Biodivers. J. 2019, 10, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Marrone, F.; Deidun, A.; Adepo-Gourene, B.; Froglia, C.; Sciberras, A.; Bariche, M.; Burak, A.Ç.; Foka-Corsini, M.; Arculeo, M. DNA taxonomy confirms the identity of the widely-disjunct mediterranean and atlantic populations of the tufted ghost crab Ocypode cursor (Crustacea: Decapoda: Ocypodidae). Zoolog. Sci. 2019, 36, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacobbe, S.; De Pasquale, P.; Porporato, E.M.D. Daily and seasonal population dynamics of Brachynotus sexdentatus (Risso, 1827) (Varunidae: Brachyura: Decapoda) in a temperate coastal lake. Acta Adriat. 2021, 62, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F.; Aquiloni, L.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J.; Tricarico, E. Managing invasive crayfish: Is there a hope? Aquat. Sci. 2011, 73, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizza, V.; Sacco, F.; Russo, D.; Scardino, R.; Arculeo, M.; Vamberger, M.; Marrone, F. The good, the bad and the ugly: Emys trinacris, Placobdella costata and Haemogregarina stepanowi in Sicily (Testudines, Annelida and Apicomplexa). Folia Parasitol. 2016, 63, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchioni, L.; Chirco, P.; Bazan, G.; Marrone, F.; Arizza, V.; Arculeo, M. First record of Temnosewellia minor (Platyhelminthes, Temnocephalidae) in Sicily, with a plea for a re-examination of the identity of the publicly available molecular sequences of the genus. Biogeographia 2021, 36, a003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Torralba-Burrial, A. First record of the redclaw crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus (Von martens, 1868) on the Iberian Peninsula. Limnetica 2021, 40, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.J.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J.; et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, F.; Alfonso, G.; Stoch, F.; Pieri, V.; Alonso, M.; Dretakis, M.; Naselli-Flores, L. An account on the non-malacostracan crustacean fauna from the inland waters of Crete, Greece, with the synonymization of Arctodiaptomus piliger Brehm, 1955 with Arctodiaptomus alpinus (Imhof, 1885) (Copepoda: Calanoida). Limnetica 2019, 38, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquiloni, L.; Caricato, G.; Chiesa, S.; Ciutti, F.; Dörr, A.J.M.; Elia, C.; Fea, G.; Ghia, D.; Inghilesi, A.; Innocenti, G.; et al. Linee guida per la conoscenza e il corretto monitoraggio dei Decapodi Dulcicoli in Italia. AIIAD 2019, 1–99. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).