Abstract

A time scale of phylogenetic relationships contributes to a better understanding of the evolutionary history of organisms. Herein, we investigate the temporal divergence pattern that gave rise to the poor species diversity of the spider genus Solenysa in contrast with the other six major clades within linyphiids. We reconstructed a dated phylogeny of linyphiids based on multi-locus sequence data. We found that Solenysa diverged from other linyphiids early in the Cretaceous (79.29 mya), while its further diversification has been delayed until the middle Oligocene (28.62 mya). Its diversification trend is different from all of the other major lineages of linyphiids but is closely related with the Cenozoic ecosystem transition caused by global climate changes. Our results suggest that Solenysa is a Cretaceous relict group, which survived the mass extinction around the K-T boundary. Its low species diversity, extremely asymmetric with its sister group, is largely an evolutionary legacy of such a relict history, a long-time lag in its early evolutionary history that delayed its diversification. The limited distribution of Solenysa species might be related to their extreme dependence on highly humid environments.

1. Introduction

Molecular data has become an indispensable tool for the reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships among species and provides important insights on the evolutionary histories of many animal groups. It is common in systematics that a high-level molecular phylogeny may significantly conflict with the established taxonomic system based on morphological characters [1,2,3,4]. Understanding the evolutionary past that shaped the species diversity of lineages always attracts the interest of biologists [5,6,7,8]. Spiders are generalist predators, forming a successful terrestrial animal group, and their high species diversity is distributed unevenly across lineages [9], even extremely asymmetrically between sister groups [4,10]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to interpret the driving forces that promote spider diversification, such as co-diversification with insects [11,12,13], key innovations in silk structure and web architecture [10], repeated evolution of the respiratory system from book lungs to tracheae [14], and foraging changes from using capturing web to cursorial habits [15]. While these studies usually focus on the driving forces for fast diversifications that lead to a speciose clade, little attention having been exerted to the factors that might result in groups with poor species diversity. Herein, we investigated the evolutionary history of Solenysa spiders, one of the seven main clades within linyphiids, with poor species diversity compared to other clades [4].

Great conflicts exist between the molecular phylogeny of linyphiids and the classical taxonomic system. Linyphiidae is an ancient spider group and its earliest fossil record dates back to the early Cretaceous, about 125–135 mya [16]. As with many other spiders, linyphiids have experienced adaptive radiation, accompanying the fast radiation of insects in the Cretaceous. Currently, with more than 4700 recognized species, Linyphiidae represents the second largest group of the order Araneae [17]. Generally, linyphiids are conservative in somatic features but have complex genitalia with species-specific characters, which are used as criteria for species recognition. The classical taxonomic system of Linyphiidae consists of seven subfamilies [18]. However, this was not supported by molecular phylogenetic analyses [1,4,7]. Four of them, Linyphiinae, Erigoninae, Micronetinae, and Ipainae, were not monophyletic groups; the representatives of Mynogleninae and Dubiaraneinae fell into Linyphiinae; the Stemonyphantinae taxa were often clustered with pimoids, the sister group of linyphiids [1,4,19,20,21]. The subfamily Stemonyphantinae was newly revised by adding two ex-pimoid genera and another linyphiid genus in it [8]. However, the seven-clade topology of molecular phylogenies are robustly supported, and all of these seven major clades (clades A–F and S in [4]) are supported by some putative synapomorphic characters.

Spider diversity is distributed unevenly among the seven major clades within linyphiids, especially between sister groups [4]. The relationships among the seven major lineages are puzzling. The cladogenetic events of the seven-clade topology were correlated with successive transformations on the state of the epigynal plate that was defined by the location of the copulatory openings and tracings of epigynal tracts [4]. Generally, a set of epigynal characters forms an epigynal type that means a certain interaction pattern between male and female genitalia during copulation [22]. The series of state transformations of the epigynal plate coupled with those lineage divergence events make the seven-clade topology meaningful [4]. Nevertheless, the driving forces that shape the unbalanced diversification across lineages within linyphiids remain unresolved. Among them, the extremely asymmetric species diversity between Solenysa (15 spp.) and its sister group (2885 spp., [18]) provides us a model system to study the evolution of such an asymmetry.

Clade S in [4] is composed of a single genus, Solenysa, and is a unique lineage in linyphiids. All Solenysa species display a distinctive somatic appearance and special genital morphology. These make them easily distinguished from all other linyphiids [23,24]. However, the placement of Solenysa within linyphiids has long been controversial. Saaristo [25] placed Solenysa together with some micronetine genera into a new subfamily, Ipainae, largely based on the females having a movable epigynum. However, this treatment was disproved by the phylogenetic analyses either based on molecular data or morphological data [1,4,24]; the molecular phylogeny supported a sister relationship between Solenysa and clade B, which is a hodgepodge composed of all erigonines, some micronetines, and linyphiines. Although such a sister-relationship was supported by some putative synapomorphies, in comparison to its speciose and widespread sister-clade, the Solenysa clade appeared unusual in term of species diversity and limited distributions and is generally only known from type localities and small adjacent areas (Figure 1; [23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]). The underlying evolutionary process that gave rise to such a biased diversity pattern between these sister clades remains to be explored.

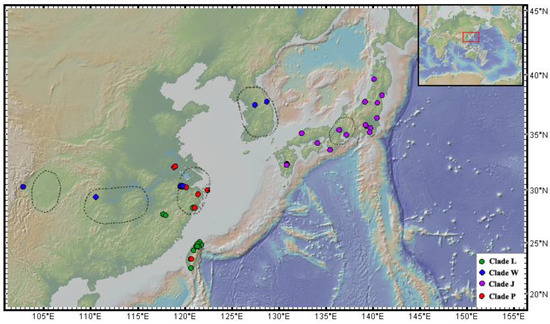

Figure 1.

Distribution of Solenysa species. Circles in color represent species of different clades in Figure 2, green, clade L; blue, clade W; purple, clade J, red, clade P. Dash line circles indicate locations of some supposed Pleistocene ice age refugia in East Asia.

Studies on the defining features (synapomorphies) of a speciose group, especially in comparison to its sister group, may help us in search of potential drivers that promote fast diversification [9]. According to Wang et al. [4], the tracheal system in clade B repeatedly evolved from the haplotracheate to desmitracheate, in which the median pair tracheae extensively branched and extended into the prosoma [33]. Especially the distal erigonines clade, all species have a desmitracheate system forming the largest group in clade B [34], contributing more than half of the species diversity of Linyphiidae. While the tracheal system in Solenysa remains as an intermediate type, with the median pair unbranched in the opisthosoma but extended into the prosoma where they branch and extend into the legs (Tu, personal observation; [24]). Anterior extending tracheae would provide oxygen directly to the brain and legs [35,36], and extensively branched tracheae may help in reducing water loss [9,37]. These imply that the selective advantages of the desmitracheate system might trigger the fast diversification in clade B, while the diversification in the Solenysa clade remained slower, which resulted in the biased species diversity between them. Nevertheless, whether there are any other reasons is unclear.

In the present study, we aimed to explore the reason that caused the biased diversification between Solenysa and its sister group. Our results from phylogenetic analyses, molecular dating, and lineage-wise diversification tracing through time suggested that Solenysa represents a Cretaceous relict spider group in East Asia, and historical climate changes have played a pivotal role in shaping its evolutionary history.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling

In the present study, we collected and sequenced four additional Solenysa species, S. lanyuensis, S. yangmingshana, S. macrodonta, and S. ogatai from their type localities on Taiwan Island and Japanese islands. The relevant sequence data for nine Solenysa species, S. longqiensis, S. retractilis, S. tianmushana, S. wulingensis, S. protrudens, S. mellotteei, S. trunciformis, S. reflexilis, and S. partibilis, have been generated in our earlier study [4]. Another two known species, S. spiralis from Sichuan, China, and S. geumoensis from the Korean Peninsula, were not sampled due to a lack of fresh materials for sequencing. Thus, 13 of the 15 known Solenysa species (86.7%) were included in the present study. To explore the phylogenetic position of Solenysa species within Linyphiidae, other linyphiid taxa of Wang et al. [4], except for the four unstable long-branch taxa and those repeated taxa, were compiled in our dataset. Pimoidae is the sister group of Linyphiidae and often used as outgroups for rooting. Given the recent revision of Pimoidae having the formerly pimoid genera Putaoa and Weintrauboa transferred to Linyphiidae, and redelimited Pimoidae as including only Pimoa and Nanoa [8], we also added representatives of Pimoa and Putaoa into the dataset. The final data set consisted of 127 taxa, including 13 Solenysa taxa, 113 other linyphiids, and one pimoid.

Collected information on the four newly sequenced Solenysa specimens is listed in Supporting Material Table S1. Specimens used for the molecular study were fixed in 95% ethanol and kept at −20 °C before DNA extraction. All newly collected specimens are deposited at the College of Life Sciences, Capital Normal University (CNU).

2.2. Laboratory Protocols for Molecular Data

Five loci used in [4], including two mitochondrial genes, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI), and 16S rRNA (16S), and three nuclear genes, 18S rRNA (18S), 28S rRNA (28S), and histone H3 (H3), were sequenced for newly collected Solenysa specimens. Laboratory protocols and sequence curation follow those described in Wang et al. [4]. The primers and their annealing temperatures used for PCR amplification in the present study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences, their sources, and reaction conditions used for PCR in this study.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

Sequences for the five genes were aligned using MAFFT 7.490 [38] and were concatenated using Mesquite version 3.31 [39] in the order of 16S, 18S, 28S, COI, and H3. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis was carried out using IQ-TREE v2.1.3 [40] with best-fit DNA substitution models selected using ModelFinder [41]. ML trees were inferred from (1) the concatenated super-matrix with a single overall the best-fit model and (2) the partitioned matrix defined by loci using PartitionFinder [42] with each partition applying its best-fit model. The GTR + F + R5 was selected as the best-fit model for the concatenated super-matrix. The models selected for partitions of the best scheme were: TIM2 + F + I + G4 for partition 16S, SYM + R4 for partition 18S + 28S, GTR + F + I + G4 for both partition COI and partition H3. Node supports were assessed through the ultrafast bootstrap method [43] with 1000 replicates, incurring the -bnni option to reduce the risk of overestimating branch supports. We also performed Bayesian phylogenetic inference based on the best partition scheme using MrBayes v3.2.6 [44]. We used the GTR model for the 16S data in place of the TIM2 model, as the latter is not implemented in MrBayes. The SYM model for the 18S + 28S data was converted from the GTR model by fixing the stationary state frequencies to be equal. MrBayes analyses were initiated with random starting trees employing four Markov chains (one cold and three hot). The Markov chains ran for 2 × 106 generations with trees and parameters being sampled every 100 generations. The “temperature” parameter was set to 0.2. The chains were converged and reached a stationary state after the iteration with the average standard deviation of split frequencies being smaller than 0.0074, and all values of potential scale reduction factor for all parameters being very close to 1.00. The majority-rule consensus tree was generated using the sample from the cold chain after the first 25% of the sample was discarded as burn-in. The topology of phylogeny inferred from the present study was statistically tested for robustness against alternative topologies with the approximately unbiased (AU) test [45].

2.4. Estimation of Divergence Times

The divergence times were estimated with a relaxed molecular clock approach implemented in BEAST2 version 2.6.6 [46]. The rate change was explicitly modeled using uncorrelated lognormal distribution across trees and a birth–death model was used for modeling speciation. The best-fit DNA substitution model was selected using bModelTest module [47] in BEAUti2. Two independent MCMC searches were run for 8 × 107 generations with trees and parameters being sampled every 1000 generations. The convergence of the MCMC chains was checked with Tracer version 1.7.1 [48]. The first 10% samples were discarded as burn-in.

Two calibration points were used: (1) the oldest linyphiid fossil from the Lower Cretaceous Lebanese amber and (2) the divergence between two endemic Hawaiian species Orsonwelles polites and Orsonwelles malus. The oldest linyphiid fossil was originally described as an undetermined linyphiid [16]. Several studies have used it as a calibration point based on different assumptions: as a stem linyphiid, a crown linyphiid, a crown clade containing all linyphiids except Stemonyphantes [7,8,19,20,49,50], or even as a stem araneoid [51]. Herein, following Arnedo and Hormiga [7], we assigned the age of the fossil to the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of Linyphiidae and applied an exponential prior with a mean of 10.0 and offset = 125.0 for this calibration, which gave a 95% confident interval of 125–155 Myr. According to Hormiga et al. [52], the Hawaiian spiders Orsonwelles malus is endemic to Kaui Island (formed 5.1 million years ago), and Orsonwelles polites is endemic to the adjacent O’ahu Island (formed 2.6–3.7 million years ago). We assigned a normal prior for the divergence time between these two species with a mean of 3.0 Myr and standard deviation of 0.5 Myr, following Arnedo and Hormiga [7].

2.5. Lineages Tracing through Time

We use lineages through time (LTT) plot to gain insight into the history of diversification for clades S (Solenysa), A, and B. Samples of dated genealogies for each of these three clades were inferred using BEAST2. The times of the MRCA for the relevant clades came from the dated phylogeny. The LTT plots were generated using Tracer version 1.7.1 [48].

3. Results

3.1. DNA Sequence Data

A total of 590 sequences were obtained. Sequences for all five genes were acquired for 88 taxa (68.22%; 88/129), and at least four genes were acquired for the majority (96.06%; 122/127). Fragments from 16S, 18S, 28S, COI, and H3 were sequenced for the taxa sampled here are 91.34% (116/127), 97.64% (124/127), 81.89% (104/127), 95.28% (121/127), and 98.43% (125/127), respectively. After alignment, the concatenated matrix includes a total of 2678 sites. All newly acquired sequences have been deposited in GenBank. The accession numbers of all samples are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Taxon list and sequence information. An asterisk (*) following species names indicate that they are newly sequenced for the present study.

3.2. Phylogeny of Solenysa

The ML trees inferred from the concatenated super-matrix and from the best partition scheme and the Bayesian tree are highly congruent as far as the major clades we concern in the present study. All analyses recovered seven major clades equivalent to those found in previous studies [4]. Given the ML estimate obtained from the partitioned analysis was significantly better than from the concatenated analysis, (log-likelihoods, −45494.13 vs. −46688.08), we reported the result from the partitioned analysis in Figure 2 (see Supplementary Material Figures S1 and S2 for node supports in ML tree and Bayesian tree). All linyphiid taxa formed a monophyletic lineage sister to the pimoid clade and were grouped into seven strongly supported (bootstrap support/Bayesian posterior = 100/1.00), named as clades A, B, C, D, E, F, and S (sensu Wang et al. [4]). The monophyly of Solenysa (clade S, 100/1.00) and its sister relationship with the species-rich clade B (100/1.00) were robustly supported (100/1.00). Relationships among the seven major lineages remain the same as those of the analyses of Wang et al. [4]. One major conflict between the phylogeny we inferred here and the phylogeny reported by [8] involved relationship between Putaoa hauaping and the Stemonyphantes species (clade E). In our results, Putaoa hauaping and the Stemonyphantes species failed to form a monophyletic clade. However, our phylogeny was strongly supported by the AU test (p = 0.99).

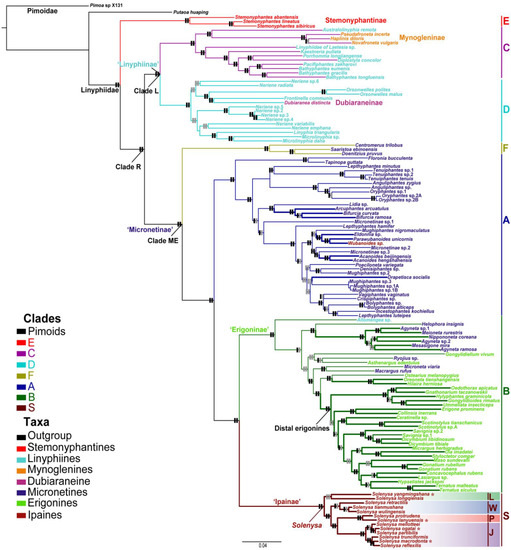

Figure 2.

ML tree of linyphiid phylogeny with proportional branch lengths. Branches in color show the seven major clades within Linyphiidae. Taxa names in color indicate their current subfamilial placements. Thickened blue branches in clade A indicate taxa having a movable epigynum. Thickened green branches in clade B indicate taxa having a desmitracheate system. Thickened branches in clade S indicate all Solenysa taxa having both movable epigynum and an intermediate type tracheate system. Bars on branches indicate corresponding node supports of the main clades: the anterior show the maximum likelihood bootstrap (BS) and the posterior Bayesian posterior probability (PP), respectively. Bars in black indicate BS > 80%; PP > 0.95; bars in grey BS < 80%, PP < 0.95. Trees with all the node supports are included as Supplementary Material.

The thirteen Solenysa taxa were further divided into four clades (Figure 2): the longqiensis clade (clade L) including S. longqiensis and S. yangmingshana (68/0.81); the wulingensis clade (clade W) including S. wulingensis, S. retractilis, and S. tianmushana (99/1.00); the mellotteei clade (clade J) including six Japanese species, S. mellotteei, S. reflexilis, S. trunciformis, S. macrodonta, S. partibili, and S. ogatai (100/1.00); and the protrudens clade (clade P), including S. protrudens and S. lanyuensis (100/1.00). Compositions of the four clades were largely congruent with the four clades recognized in phylogenetic analysis based on morphological data, each of which was supported by several synapomorphies [12]. However, the relationships among these clades in our results were: the longqiensis clade was the most basal lineage sister to all other Solenysa clades (100/1.00); the mellotteei clade was sister to the protrudens clade (100/1.00), and the clade (mellotteei + protrudens) was sister to the wulingensis clade (95/1.00).

Mapping the characters of the epigynum with an extensible base and the desmitracheate system onto the phylogenetic framework show that the movable epigynum independently evolved multiple times in clades A and S. The Solenysa clade was distantly related with the taxon of Ipainae (Wubanoides sp.) and those micronetines also having a movable epigynum. The desmitracheate system independently evolved in clade B multiple times.

Distributions of the four Solenysa clades have different patterns (Figure 1). All species of Clade J are limited to the Japanese Archipelago; the species of clades L and P are known from the southeast coast of China and Taiwan Island; those of clade W scatter in southern China, as well as the Korean Peninsula (not sampled here). All Solenysa species have a disjunct distribution, and all the materials studied here were collected from leaf litter with high ambient humidity.

3.3. Divergence Times Estimation

Divergence times of the relevant nodes within linyphiids estimated using a relaxed molecular clock method in BEAST are provided in Table 3. The dated phylogeny is shown in Figure 3, with branches of the other six major clades collapsed and the complete chronogram is presented in Supplementary Material Figure S3.

Table 3.

Divergence times of relevant nodes within linyphiids estimated using a relaxed molecular clock method in BEAST.

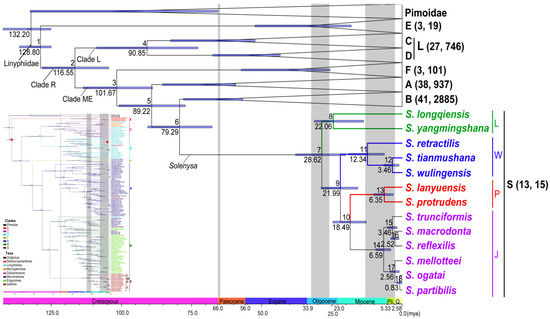

Figure 3.

Chronogram of linyphiids. Branches and taxon names in color show the four clades within Solenysa. Branches of other six major clades collapsed. In the complete chronogram shown in microimage, two red dots indicate calibration points. Numbers in parentheses after clade names refer to the sampling numbers of the clades and species numbers represented, respectively. Numbers above branches label the divergence nodes of the seven major clades within linyphiids and internal nodes within Solenysa. Values below branches show divergence time of nodes, and node bars show confidence intervals. Three grey belts refer to K-T boundary, early and middle Oligocene, and middle Miocene and Pliocene, respectively.

The chronogram of linyphiids suggests that all the seven major lineages survived the K-T boundary. The MRCA of all linyphiids (node 1) can be traced back to the early Cretaceous (128.80 mya, 95% HPD, 125.14–136.36 mya). Clade S and clade B (node 6) diverged around 79.29 (67.69–90.67) mya in the Cretaceous. Further diversifications in the linyphiid lineages largely took place after the K-T boundary, except for the Solenysa clade. The earliest split of Solenysa species (node 7) can only be traced back to 28.62 (20.09–37.98) mya in the middle Oligocene. In the following 10 Myr until the early Miocene, all of the four Solenysa clades (nodes 8–10) have appeared. The speciation of extant species (nodes 11–17) took place largely in the middle Miocene and the Pliocene, ranging between 12.34 (6.29–18.98) mya to 2.56 (0.99–4.33) mya, before the onset of the Quaternary climatic oscillations (2.6 mya–present [53,54]). Two exceptions involved the divergence of Japanese species, between S. partibilis and S. ogatai (node 18), which occurred much recently, around 0.83 (0.02–1.94) mya and between S. macrodonta and S. reflexilis (node 16), around 2.52 (1.12–4.07) mya during the Quaternary glaciations. In contrast, diversification in clades A and B crossed the K-T boundary and continued during the whole Cenozoic.

3.4. Temporal Patterns of Linyphiids Diversification

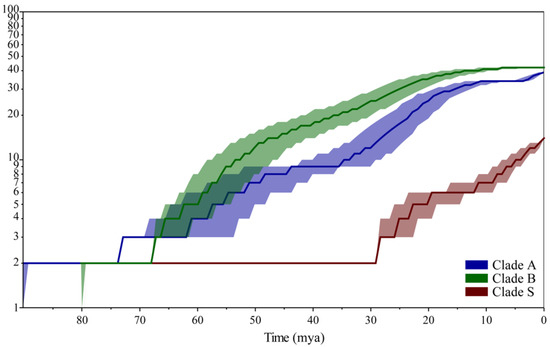

Analysis of lineage accumulation over time using LTT plots suggested that species of clade A and clade B began to accumulate long before the K-T boundary, while the lineage number in clade S (Solenysa) did not change until the Oligocene, long after the K-T boundary (Figure 4). Both clade S and clade B experienced obvious increases in the accumulation of lineages during the Oligocene. Besides, clade S experienced a unique fast lineage-accumulating phase during the last 10 Myr.

Figure 4.

Temporal patterns of linyphiid lineage diversifications. a, stepped line in color indicate species number of lineages vary through time for Solenysa clade (brown), clade A (purple), and clade B (green). The shadowed areas in the same color show 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

For a long time, a temporal framework was lacking for linyphiids, the second-largest group of spiders (but see [7,8]). Through phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating based on sequence data of five genes for all major groups of linyphiids, we brought a time scale to this important spider group and gained some illuminating insights into the evolutionary history that gave rise to the poor species diversity of Solenysa spiders contrasted with its sister group. We further use LTT plots to demonstrate the history of Solenysa diversification.

Solenysa spiders originated in the first radiation of linyphiids and missed the second burst of speciation in this group. The chronogram shows that the MRCA of linyphiids can be traced back to the early Cretaceous (Figure 3); it might even be traced to the Jurassic [20]. All the seven major clades, including the Solenysa clade, emerged during the Cretaceous. Being generalist predators in natural ecosystems, linyphiid spiders weave horizonal sheet webs to catch prey [1]. Their web-building level varies a lot across the seven major clades (Figure 2): most taxa of clade C + D, traditionally grouped in Linyphiinae, build aerial webs at various levels of vegetation, especially often at the crown level, while the taxa of clade ME mainly formed by species of Micronetinae and Erigoninae build their webs much closer to the ground. Generally, those micronetines with dorsal spots on their abdomen usually build aerial webs at the leaf-litter surface in forests, and those of clade B, especially those erigonines having an abdomen in grey to dark black without dorsal spots, build substrate-webs close to or even on the ground. Solenysa spiders, as members of clade ME, inhabit the litter layer in forests and have a grayish abdomen without dorsal spots; they build their webs close to the ground (see the figure in [31]). These suggest that linyphiids had their first diversification, as in many other spiders, accompanied by the co-adaptative radiation of insects and angiosperms in the Cretaceous [1,11,12,55], and diversification among the seven clades were accompanied by the divergence of their web-building levels. Furthermore, the subsequent diversification within these major clades mainly flourished in the Cenozoic in general. This indicates that the species diversity of all seven clades was significantly affected by the mass extinction of the K-T boundary (65 mya, [56]); their diversifications in the Cenozoic was, in fact, the second radiation in linyphiid evolution. Unlike other major clades, diversification in the Solenysa clade has a long-time lag of more than 50 Myr in their early history. The single lineage crossed the K-T boundary, with the earliest split occurring 28.62 mya in the middle Oligocene, much later than its sister group clade B, and their sister group clade A (Figure 4), although we expanded the sampling of Solenysa taxa in the present study.

The low species diversity of Solenysa spiders might result from both the lower diversification rate than that of their sister group clade B and the long-time lag in their evolutionary history. Among all the major clades of linyphiids, only in clade B did the desmitracheate system independently evolve multiple times (Figure 2). Although its selective advantages, either the high efficiency of anteriorly extending tracheae in providing oxygen directly to the brain and legs [35,36] or the assistance of extensively branched tracheae on water retention [9,37], have never been physiologically tested in web-weaver spiders (but see the morphological test in [57]), such a tracheal system repeatedly evolved in clade B, as well as in several litter-dweller spider groups [14,58,59], which implies its selective advantage for these spiders. Furthermore, the great species diversity of clade B, especially of the distal erigonines clade, suggest that the desmitracheate system might be a key innovation that triggered the fast diversification in clade B. Accordingly, without driving by the selection advantages of the desmitracheate system, it is not a surprise that the diversification rate of Solenysa clade is not as fast as that of clade B. Nevertheless, this is not the only reason attributed to the extreme asymmetry in the species diversity between the Solenysa clade and clade B. The long time lag across the K-T boundary to the middle Oligocene makes the Solenysa clade have no origination of any further extant groups for more than half of the common historical time shared with clades A and B (Figure 4).

Being highly dependent on high-humidity environments may be a major limit impact on Solenysa spiders. Unlike book lungs, tracheal respiration in spiders does not depend on hemolymph [36,60], and intensive branched tracheae are helpful in saving water [9,37]. Nevertheless, the intermediate-type tracheal system in Solenysa has the unbranched median pair tracheae extending into the prosoma [24]. Furthermore, their living habits are usually in areas with high ambient humidity. Although building sheet-webs at litter level, Solenysa spiders failed to leave forests for more open and less humid ecosystems, such as grasslands, or even as pioneers to colonize the ecological bare grounds as those erigonines of their sister group. Accordingly, we infer that their extreme dependence on high environmental humidity is the main constraint for their distribution.

Our results show the temporal patterns of linyphiid lineage diversification were closely related to global climate changes (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Although the Paleocene Earth was commonly considered ice-free and the global climate was warm and humid [61,62], evidence has shown that the climate in Asia was dry during most of the Paleogene. There was an arid belt that existed from the western-most part to the eastern coasts, and arid and semi-arid conditions dominated in large areas of China [63]. This led to the formation of temperate grasslands and savannah ecosystems on most land at the expense of forest decline [61,62,64]. Such ecosystem transformations might have acted as a driving force that promoted the rapid diversification of micronetines (clade A) and erigonines (clade B) but might be a major constraint on the survival of Solenysa species. Nevertheless, such a dry belt retreated northwestward from the Eocene to the Oligocene [63]. Until the late Oligocene (28–24 mya), the southeast part of China, including the southeast coasts and Taiwan Island, became humid. This might have triggered the diversification of extant Solenysa spiders (28.62 mya, Figure 3). In the following Miocene (24–5.3 mya) and the Pliocene (5.3–2.6 mya), the humid belt further expanded northwards, the whole eastern part of China transformed into humid conditions. During this time, clade S experienced a unique fast lineage-accumulating phase. Therefore, such climate changes might have released the constraint from arid conditions and promoted the diversification of Solenysa in the Neogene.

Solenysa spiders display typical characters of a relict group, with low species diversity and narrow distribution [65,66,67]. The chronogram of linyphiids shows that most Solenysa species have emerged before the onset of the Quaternary glaciations (2.6 mya, [53,54]). However, all of the 15 known species have a disjunct distribution, most of them being only known from type localities that fall near the supposed Pleistocene glacial refugia in East Asia (Figure 1; [68,69,70,71,72]). This suggests that the refugia have played an important role in maintaining these Solenysa species during the glacial period. The dramatically cold climate during the glacial period would generally incur contractions of the distribution range [65,66,73,74,75]. Such an interpretation may partially explain the current disjunct distribution patterns of Solenysa species. However, it also implies that Solenysa species have failed to expand their distributional ranges as the climate became warmer in the post-glacial periods. Generally, linyphiids, as well as most other spiders, are capable of dispersal by balloon [60]. Nevertheless, long-distance dispersal by ballooning means spiders staying a long time in the air without a water supply. The survival of Solenysa spiders depends extremely on highly humid environments that not only constrain their distribution but also limit their capacity for long-time ballooning for dispersal, especially when suitable habits are segmentized. Accordingly, the current distribution pattern of Solenysa spiders might be shaped by both the locations of those refugia they survived during the Quaternary glaciations and their weak dispersal capacity.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that Solenysa is a Cretaceous relict group, having survived the mass extinctions at the K-T boundary and the ecosystem transition caused by the global climate changes in the Cenozoic. Its diversification was shaped by the climatic oscillations in the Cenozoic. The low species diversity of the Solenysa clade, in contrast to its sister group, is largely due to the long time lag in its early evolutionary history. Given Solenysa represents a strongly supported major clade in linyphiid multi-locus phylogeny and is supported by several synapomorphies, it warrants a subfamilial status in Linyphiidae.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d14020120/s1, Table S1: Collecting information of the Solenysa spider sequenced in the present study; Figure S1: Bayesian tree with all nodes supports; Figure S2: ML tree with all nodes supports; Figure S3: The complete chronogram.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.T., C.S., and L.T.; methodology, J.T., Y.Z., C.S., and L.T.; acquisition, J.T., H.O., L.T.; formal analysis, J.T., Y.Z., C.S., and L.T.; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, J.T., C.S., and L.T.; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, L.T., and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant Nos. 31572244, 31872188 and 31772435).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The new genetic sequences are available on GenBank (ac-cession codes: OL693166 to OL693169 (COI), OL691622 to OL691623 (16S), OL691624 to OL691627 (18S), OL691628 to OL691631 (28S), OL702837 to OL702840 (H3)) and also as a supplement to this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Fu and the anonymous reviewers for their critical comments on the early versions of this manuscript. We also thank F. Wang, F. Zhang, S. Tian., Z. Zhao, and R. Li for their kind assistance in field work, and A. Andoh and A. Tanikawa for kindly providing Solenysa material collected from Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnedo, M.A.; Hormiga, G.; Scharff, N. Higher-level phylogenetics of linyphiid spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae) based on morphological and molecular evidence. Cladistics 2009, 25, 231–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabert, M.; Witalinski, W.; Kaźmierski, A.; Olszanowski, Z.; Dabert, J. Molecular phylogeny of acariform mites (Acari, Arachnida): Strong conflict between phylogenetic signal and long-branch attraction artifacts. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2010, 56, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.P.; Kaluziak, S.T.; Perez-Porro, A.; González, V.L.; Hormiga, G.; Wheeler, W.C.; Giribet, G. Phylogenomic interrogation of Arachnida reveals systemic conflicts in phylogenetic signal. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 2963–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Ballesteros, J.A.; Hormiga, G.; Chesters, D.; Zhan, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhu, C.; Chen, W.; Tu, L. Resolving the phylogeny of a speciose spider group, the family Linyphiidae (Araneae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2015, 91, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Cardillo, M.; Jones, K.E.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Beck, R.M.D.; Grenyer, R.; Price, S.A.; Vos, R.A.; Gittleman, J.L.; Purvis, A. The delayed rise of present-day mammals. Nature 2007, 446, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near, T.J.; Dornburg, A.; Kuhn, K.L.; Eastman, J.T.; Pennington, J.N.; Patarnello, T.; Zane, L.; Fernández, D.A.; Jones, C.D. Ancient climate change, antifreeze, and the evolutionary diversification of Antarctic fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3434–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnedo, M.A.; Hormiga, G. Repeated colonization, adaptive radiation and convergent evolution in the sheet-weaving spiders (Linyphiidae) of the south Pacific Archipelago of Juan Fernandez. Cladistics 2020, 37, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormiga, G.; Kulkarni, S.; Moreira, T.D.S.; Dimitrov, D. Molecular phylogeny of pimoid spiders and the limits of Linyphiidae, with a reassessment of male palpal homologies (Araneae, Pimoidae). Zootaxa 2021, 5026, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Hormiga, G. Spider Diversification Through Space and Time. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.E.; Opell, B.D. Testing adaptive radiation and key innovation hypotheses in spiders. Evolution 1998, 52, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, D. Does the fossil record of spiders track that of their principal prey, the insects? Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh Earth Sci. 2003, 94, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, D.; Ortuño, V.M. Oldest true orb-weaving spider (Araneae: Araneidae). Biol. Lett. 2006, 2, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selden, P.A.; Penney, D. Fossil spiders. Biol. Rev. 2010, 85, 171–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopardo, L.; Michalik, P.; Hormiga, G. Take a deep breath… The evolution of the respiratory system of symphytognathoid spiders (Araneae, Araneoidea). Org. Divers. Evol. 2021, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, N.L.; Rodriguez, J.; Agnarsson, I.; Coddington, J.A.; Griswold, C.E.; Hamilton, C.A.; Hedin, M.; Kocot, K.M.; Ledford, J.M.; Bond, J.E. Spider phylogenomics: Untangling the Spider Tree of Life. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penney, D.; Selden, P.A. The oldest linyphiid spider, in Lower Cretaceous Lebanese amber (Araneae, Linyphiidae, Linyphiinae). J. Arachnol. 2002, 30, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Spider Catalog. Version 22.5. Natural History Museum Bern. Available online: http://wsc.nmbe.ch (accessed on 20 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Tanasevitch, A.V. Linyphiid Spiders of the World. Available online: http://www.andtan.newmail.ru/list (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Dimitrov, D.; Lopardo, L.; Giribet, G.; Arnedo, M.; Álvarez-Padilla, F.; Hormiga, G. Tangled in a sparse spider web: Single origin of orb weavers and their spinning work unravelled by denser taxonomic sampling. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2011, 279, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Benavides, L.R.; Arnedo, M.; Giribet, G.; Griswold, C.E.; Scharff, N.; Hormiga, G. Rounding up the usual suspects: A standard target-gene approach for resolving the interfamilial phylogenetic relationships of ecribellate orb-weaving spiders with a new family-rank classification (Araneae, Araneoidea). Cladistics 2017, 33, 221–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, W.C.; Coddington, J.A.; Crowley, L.M.; Dimitrov, D.; Goloboff, P.A.; Griswold, C.E.; Hormiga, G.; Prendini, L.; Ramírez, M.J.; Sierwald, P.; et al. The spider tree of life: Phylogeny of Araneae based on target-gene analyses from an extensive taxon sampling. Cladistics 2017, 33, 574–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, W.G. Evolution of genitalia: Theories, evidence, and new directions. Genetica 2010, 138, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Li, S. A review of the linyphiid spider genus Solenysa (Araneae, Linyphiidae). J. Arachnol. 2006, 34, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Hormiga, G. Phylogenetic analysis and revision of the linyphiid spider genus Solenysa (Araneae: Linyphiidae: Erigoninae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 161, 484–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaristo, M.I. A new subfamily of linyphiid spiders based on a new genus created for the keyserlingi-group of the genus Lepthyphantes (Aranei: Linyphiidae). Arthropoda Sel. 2007, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Namkung, J. Two unrecorded species of linyphiid spiders from Korea. Korean Arachnol. 1986, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Song, D. On two new species of soil linyphiid spiders from China (Araneae: Linyphiidae: Erigoninae). Acta Arachnol. Sin. 1992, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.C.; Zhu, C.D.; Sha, Y.H. Two new species of the genus Solenysa from China (Araneae: Linyphiidae: Erigoninae). Acta Arachnol. Sin. 1993, 2, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L.; Ono, H.; Li, S. Two new species of Solenysa Simon, 1894 (Araneae: Linyphiidae) from Japan. Zootaxa 2007, 1426, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H. Notes on Japanese spiders of the genera Paikiniana and Solenysa (Araneae, Linyphiidae). Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. Ser. A 2011, 37, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L.; Wang, F.; Ono, H. A review of Solenysa spiders from Japan (Araneae, Linyphiidae), with a comment on the type species S. mellotteei Simon, 1894. ZooKeys 2015, 481, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tu, L. A new species of the spider genus Solenysa from China (Araneae, Linyphiidae). Zootaxa 2018, 4531, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blest, A.D. The tracheal arrangement and the classification of linyphiid spiders. J. Zool. 1976, 180, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormiga, G. Higher level phylogenetics of erigonine spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae, Erigoninae). Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 2000, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A. Metabolic rates during rest and activity in differently tracheated spiders (Arachnida, Araneae): Pardosa lugubris (Lycosidae) and Marpissa muscosa (Salticidae). J. Comp. Physiol. B 2004, 174, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spider Ecophysiology; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–529.

- Levi, H.W. Adaptations of respiratory systems of spiders. Evolution 1967, 21, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis. Version 3.51. Available online: http://www.mesquiteproject.org (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, R.; Calcott, B.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Guindon, S. PartitionFinder: Combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimodaira, H. An approximately unbiased test of phylogenetic tree selection. Syst. Biol. 2002, 51, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Heled, J.; Kühnert, D.; Vaughan, T.; Wu, C.-H.; Xie, D.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2: A software platform for bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouckaert, R.R.; Drummond, A.J. bModelTest: Bayesian phylogenetic site model averaging and model comparison. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, R.; Kallal, R.J.; Dimitrov, D.; Ballesteros, J.A.; Arnedo, M.A.; Giribet, G.; Hormiga, G. Phylogenomics, diversification dynamics, and comparative transcriptomics across the Spider Tree of Life. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 1489–1497.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharff, N.; Coddington, J.A.; Blackledge, T.A.; Agnarsson, I.; Framenau, V.; Szűts, T.; Hayashi, C.Y.; Dimitrov, D. Phylogeny of the orb-weaving spider family Araneidae (Araneae: Araneoidea). Cladistics 2020, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, I.L.F.; Azevedo, G.H.F.; Michalik, P.; Ramírez, M.J. The fossil record of spiders revisited: Implications for calibrating trees and evidence for a major faunal turnover since the Mesozoic. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 184–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormiga, G.; Arnedo, M.; Gillespie, R.G. Speciation on a conveyor belt: Sequential colonization of the Hawaiian Islands by Orsonwelles spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae). Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G.M. The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature 2000, 405, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G.M. Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the Quaternary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackledge, T.A.; Scharff, N.; Coddington, J.A.; Szüts, T.; Wenzel, J.W.; Hayashi, C.Y.; Agnarsson, I. Reconstructing web evolution and spider diversification in the molecular era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5229–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayar, A. Asteroid impact may have gassed Earth. Nature 2009, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opell, B.D. The influence of web monitoring tactics on the tracheal systems of spiders in the family Uloboridae (Arachnida, Araneida). Zoomorphology 1987, 107, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopardo, L.; Hormiga, G. On the synaphrid spider Cepheia longiseta (Simon 1881) (Araneae, Synaphridae). Am. Museum Novit. 2007, 20052, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopardo, L.; Hormiga, G. Out of the twilight zone: Phylogeny and evolutionary morphology of the orb-weaving spider family Mysmenidae, with a focus on spinneret spigot morphology in symphytognathoids (Araneae, Araneoidea). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 173, 527–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foelix, R.F. Biology of Spiders, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zachos, J.C.; Dickens, G.R.; Zeebe, R.E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 2008, 451, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, C.A. Evolution of grasses and grassland ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 39, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.T.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Z.S.; Peng, S.Z.; Xiao, G.Q.; Ge, J.Y.; Hao, Q.Z.; Qiao, Y.S.; Liang, M.Y.; Liu, J.F.; et al. A major reorganization of Asian climate by the Early Miocene. Clim. Past 2008, 4, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.J. Evolutionary shifts in extant mustelid (Mustelidae: Carnivora) cranial shape, body size and body shape coincide with the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition. Biol. Lett. 2019, 15, 20190155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, A.; Jump, A.S. Climate Relicts: Past, Present, Future. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandcolas, P.; Nattier, R.; Trewick, S. Relict species: A relict concept? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandcolas, P.; Trewick, S. Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics, Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Weadick, C.J.; Zeng, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; Hu, Y. Phylogeographic analysis of the Bufo gargarizans species complex: A revisit. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2005, 37, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzée, A.; Santos, J.; Sanchez-Ramirez, S.; Bae, Y.; Heo, K.; Jang, Y.; Jowers, M.J. Phylogeographic and population insights of the Asian common toad (Bufo gargarizans) in Korea and China: Population isolation and expansions as response to the ice ages. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Cao, L.-J.; Li, B.-Y.; Gong, Y.-J.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Wei, S.-J. Multiple refugia from penultimate glaciations in East Asia demonstrated by phylogeography and ecological modelling of an insect pest. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Ishikawa, T.; Liu, H.; Kamitani, S.; Tadauchi, O.; Cai, W.; Li, H. Phylogeography of the assassin bug Sphedanolestes impressicollis in East Asia inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, S.; Sakaguchi, S.; Hirota, S.K.; Kurashima, O.; Suyama, Y.; Nishida, S.; Ito, M. Refugia within refugium of Geranium yesoense (Geraniaceae) in Japan were driven by recolonization into the southern interglacial refugium. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 132, 552–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.C.; Assmann, T. Relict Species: Phylogeography and Conservation Biology; Springer eBooks: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.-M.; Ji, Y.-J.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.-X. Impact of climate changes from Middle Miocene onwards on evolutionary diversification in Eurasia: Insights from the mesobuthid scorpions. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 1700–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammola, S.; Hormiga, G.; Arnedo, M.A.; Isaia, M. Unexpected diversity in the relictual European spiders of the genus Pimoa (Araneae: Pimoidae). Invertebr. Syst. 2016, 30, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).