Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage is a potential source of secondary infections in COVID-19 patients, yet it remains unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 infection favors colonization by more virulent or resistant strains. We analyzed 31 nasal S. aureus isolates from hospitalized COVID-19 patients to assess antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene content, and genetic diversity. Only two isolates (6.4%) were methicillin resistant, and most strains showed limited resistance beyond the MLSB phenotype. Adhesin genes were highly prevalent, whereas toxin genes were detected in only 16.1% of isolates. Spa typing revealed high genetic diversity with no dominant clone. Overall, S. aureus isolates from COVID-19 patients did not differ substantially from previously described carriage strains, suggesting no selective enrichment of highly virulent or resistant lineages during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a major opportunistic pathogen responsible for a wide spectrum of infections ranging from mild skin disease to severe invasive conditions such as pneumonia, sepsis, and infective endocarditis [1]. Secondary bacterial infections have historically contributed substantially to morbidity and mortality during viral respiratory pandemics, and S. aureus remains one of the most frequently reported bacterial pathogens associated with severe viral illness [2,3]. In patients with COVID-19, S. aureus has been commonly identified as a cause of bacterial coinfection, particularly among hospitalized and critically ill individuals [4,5,6].

Nasal carriage of S. aureus represents a key endogenous reservoir for subsequent infection. Approximately 20–30% of healthy adults are persistent nasal carriers, and carriage is associated with a markedly increased risk of invasive disease, especially in elderly and hospitalized patients [7,8]. In individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection, reported S. aureus carriage rates are comparable to those observed in the general population, yet concerns remain that viral infection, immune dysregulation, or antibiotic exposure may favor colonization by strains with increased virulence or antimicrobial resistance [7,9]. Therefore, detection of S. aureus carriage—especially methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)—is important for preventing and managing secondary infections in COVID-19 patients.

The pathogenic potential of S. aureus is determined by a combination of antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene content, and genetic background [10,11,12]. Adhesins facilitating colonization and tissue invasion, as well as toxin genes encoding superantigens, contribute to disease severity, while clonal lineage influences transmission dynamics and epidemiology. However, data addressing whether S. aureus strains colonizing COVID-19 patients differ from previously described carriage isolates remain limited.

In this Communication, we provide a concise molecular snapshot of nasal S. aureus isolates recovered from hospitalized COVID-19 patients, focusing on antimicrobial resistance patterns, selected virulence determinants, and genetic diversity assessed by spa typing. The aim of this study was to determine whether SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with enrichment of particular S. aureus clones or virulence profiles among nasal carriers.

2. Results

A total of 31 nasal Staphylococcus aureus isolates from COVID-19 patients were analyzed. Overall antimicrobial resistance was low. Only two isolates (6.4%) were identified as MRSA, and resistance to antibiotics other than β-lactams was uncommon. The macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance phenotype was observed in 35.5% of isolates, predominantly as inducible resistance, while resistance to ciprofloxacin and mupirocin was rare. All isolates were susceptible to glycopeptides, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and aminoglycosides tested (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance of S. aureus nasal strains isolated from COVID-19 patients.

Virulence gene profiling revealed a high prevalence of adhesin genes associated with nasal colonization. Genes encoding laminin-binding protein (eno) and clumping factors (clfA, clfB) were detected in all isolates, whereas other adhesin genes occurred at variable frequencies. In contrast, toxin genes were infrequently detected, with only five isolates (16.1%) carrying genes encoding toxic shock syndrome toxin or enterotoxins. Genes encoding Panton–Valentine leucocidin and exfoliative toxins were absent (Table 2).

Table 2.

The prevalence of toxin and adhesin genes in S. aureus nasal strains isolated from COVID-19 patients.

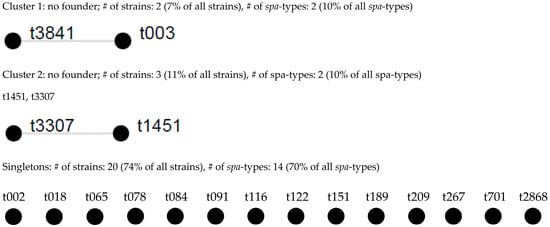

Spa typing demonstrated substantial genetic heterogeneity among the isolates, as illustrated in Figure 1. Twenty different spa types were identified, with most isolates belonging to unrelated genetic backgrounds and no dominant clone observed. Both MRSA isolates and toxin-positive strains were distributed among distinct spa types, indicating the absence of clonal expansion of high-risk lineages among nasal S. aureus isolates from COVID-19 patients. Detailed spa types and associated resistance and virulence profiles are provided in Supplementary Table S1, while the occurrence of adhesins in relation to spa types is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

Population structure of 27 S. aureus isolates after BURP analysis with a cost of 4. Clusters of linked spa types correspond to spa-CCs. The spa types that were defined as founders of particular clusters are indicated in blue. % of strains based on 27 strains collection; % of spa types based on 20 spa types (including excluded ones); # sign means the word number.

3. Discussion

Secondary bacterial infections, particularly those caused by Staphylococcus aureus, have been recognized as important contributors to adverse outcomes during viral respiratory infections, including COVID-19 [13]. However, whether SARS-CoV-2 infection promotes colonization by S. aureus strains with enhanced virulence or antimicrobial resistance has remained unclear [14]. In this Communication, we show that nasal S. aureus isolates from hospitalized COVID-19 patients do not differ substantially from previously described carriage strains with respect to resistance profiles, virulence gene content, or genetic structure.

Overall antimicrobial resistance among the analyzed isolates was low. Only a small proportion of strains were identified as MRSA, and resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics was limited, with the MLSB phenotype being the most frequently observed. These findings are consistent with reports from the general population and hospitalized cohorts and do not indicate selective enrichment of multidrug-resistant S. aureus during SARS-CoV-2 infection [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Importantly, resistance to mupirocin and fluoroquinolones was rare, suggesting that nasal decolonization strategies remain effective in this setting [25].

Analysis of virulence determinants revealed a high prevalence of adhesin genes involved in colonization and host tissue interaction, which is characteristic of S. aureus nasal carriage isolates [11,26,27,28]. In contrast, toxin genes encoding superantigens were detected infrequently and were distributed among unrelated genetic backgrounds. The low prevalence of toxin genes and the absence of Panton–Valentine leucocidin or exfoliative toxin genes further support the conclusion that SARS-CoV-2 infection does not preferentially select for highly virulent S. aureus strains at the level of nasal carriage [17,29].

Genotyping by spa typing demonstrated substantial genetic diversity, with most isolates belonging to unrelated spa types and no dominant clone identified. This heterogeneous population structure mirrors that observed in asymptomatic carriers and indicates that colonization in COVID-19 patients arises from diverse endogenous strains rather than expansion of specific epidemic lineages. Although individual isolates carrying notable resistance or virulence traits were identified, these occurred sporadically and were not associated with a particular clonal background [30,31,32,33,34].

This study has limitations, including the relatively small sample size and single-center design, which restrict the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, the consistency of our results with existing carriage studies suggests that the observed patterns are representative rather than incidental.

In summary, nasal S. aureus isolates from COVID-19 patients exhibit genetic diversity, limited antimicrobial resistance, and virulence profiles comparable to those of previously described carrier strains. These data indicate that SARS-CoV-2 infection is not associated with enrichment of high-risk lineages among nasal carriers, while highlighting the importance of continued surveillance in elderly and hospitalized populations.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Identification of S. aureus

Between December 2021 and April 2024, a total of 31 Staphylococcus aureus isolates were recovered from anterior nasal swabs of hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Samples were collected during routine admission screening at a regional hospital in northern Poland, with one isolate included per patient. Bacterial identification was performed using standard microbiological methods. Ethical approval was obtained from the Local Independent Committee for Ethics in Scientific Research at the Medical University of Gdańsk (NKBBN/525/2021). The main clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using the disk diffusion method in accordance with EUCAST guidelines accurate for the year of specimen’s isolation [35]. Methicillin resistance was identified using cefoxitin disks and confirmed by detection of the PBP2a protein. Inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance was assessed using the D-test. Susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin was evaluated using E-test strips. Reference S. aureus strains ATCC 25923 and ATCC 43300 were used for quality control.

4.3. Detection of Virulence Genes

Genomic DNA was extracted from all isolates, and selected virulence genes encoding adhesins and toxins were detected by PCR using previously described protocols [36,37]. Target genes included adhesins associated with colonization and tissue interaction as well as genes encoding superantigenic toxins.

4.4. Spa Typing

Genetic diversity was assessed by spa typing based on sequencing of the polymorphic X region of the spa gene [38,39]. Spa types were assigned using the Ridom SpaServer database, and clonal relatedness was evaluated using the BURP algorithm. Detailed spa typing parameters and extended clustering results are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27031250/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P., M.K.-S. and J.M.; methodology, L.P. and M.K.-S.; validation, L.P.; formal analysis, L.P.; investigation, L.P., M.P. and M.K.-S.; resources, M.P. and A.P.; data curation, L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P., A.N. and K.K.-K.; writing—review and editing, A.N., K.K.-K. and M.K.-S.; visualization, L.P.; supervision, A.P., M.K.-S. and J.M.; project administration, L.P.; funding acquisition, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Gdańsk, grant number 01-10025/0008269/01/MPK/MPK/0/2025 to Lidia Piechowicz.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Local Independent Committee for Ethics in Scientific Research at the Medical University of Gdańsk, no. NKBBN/525/2021, issued: 6 September 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because specimens were collected from patients who were routinely screened for S. aureus carriage during admission and hospitalization, in accordance with hospital procedures.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data available per request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.-H.; Tseng, H.-K.; Wang, W.-S.; Chiang, H.-T.; Wu, A.Y.-J.; Liu, C.-P. Clinical characteristics of children and adults hospitalized for influenza virus infection. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2014, 47, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Goodarzi, P.; Asadi, M.; Soltani, A.; Aljanabi, H.A.A.; Jeda, A.S.; Dashtbin, S.; Jalalifar, S.; Mohammadzadeh, R.; Teimoori, A.; et al. Bacterial co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; May, A.; Tan, L.; Hughes, H.; Jones, J.P.; Harrison, W.; Bradburn, S.; Tyrrel, S.; Muthuswamy, B.; Berry, N.; et al. Comparative incidence of early and late bloodstream and respiratory tract co-infection in patients admitted to ICU with COVID-19 pneumonia versus Influenza A or B pneumonia versus no viral pneumonia: Wales multicentre ICU cohort study. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, V.; Lawrence, H.; Lansbury, L.E.; Webb, K.; Safavi, S.; Zainuddin, N.I.; Huq, T.; Eggleston, C.; Ellis, J.; Thakker, C.; et al. Co-infection in critically ill patients with COVID-19: An observational cohort study from England: Read the story behind the paper on the Microbe Post here. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Moore, L.S.P.; Zhu, N.; Ranganathan, N.; Skolimowska, K.; Gilchrist, M.; Satta, G.; Cooke, G.; Holmes, A. Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals With Coronavirus: A Rapid Review To Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2459–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouwen, J.L.; Ott, A.; Kluytmans-Vandenbergh, M.F.Q.; Boelens, H.A.M.; Hofman, A.; Van Belkum, A.; Verbrugh, H.A. Predicting the Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Carrier State: Derivation and Validation of a “Culture Rule”. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susethira, A. Management of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection of Endogenous Origin in an Electrical Burns Patient—A Case Report. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2014, 4, 1138–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowora, M.A.; Aiyedogbon, A.; Omolopo, I.; Tajudeen, A.O.; Onyeaghasiri, F.; Edu-Muyideen, I.; Olanlege, A.-L.O.; Abioye, A.; Bamidele, T.A.; Raheem, T.; et al. Nasal carriage of virulent and multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A possible comorbidity of COVID-19. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.J.; Geoghegan, J.A.; Ganesh, V.K.; Höök, M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: The many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Pöllath, C.; Siegmund, A.; Deinhardt-Emmer, S.; Hoerr, V.; Svensson, C.-M.; Thilo Figge, M.; Monecke, S.; Löffler, B. Clinical S. aureus Isolates Vary in Their Virulence to Promote Adaptation to the Host. Toxins 2019, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Cornforth, D.M.; Mideo, N. Evolution of virulence in opportunistic pathogens: Generalism, plasticity, and control. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Fauci, A.S. Predominant Role of Bacterial Pneumonia as a Cause of Death in Pandemic Influenza: Implications for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-C.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Hsueh, S.-C.; Yen, M.-Y.; Ko, W.-C.; Hsueh, P.-R. Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neradova, K.; Jakubu, V.; Pomorska, K.; Zemlickova, H. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in veterinary professionals in 2017 in the Czech Republic. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfingsten-Würzburg, S.; Pieper, D.H.; Bautsch, W.; Probst-Kepper, M. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nursing home residents in northern Germany. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 78, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piechowicz, L.; Garbacz, K.; Wiśniewska, K.; Dąbrowska-Szponar, M. Screening of Staphylococcus aureus nasal strains isolated from medical students for toxin genes. Folia Microbiol. 2011, 56, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, K.; Tóthpál, A.; Kovács, E.; Sahin-Tóth, J.; Horváth, A.; Kardos, S.; Dobay, O. High prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among children in Szolnok, Hungary. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2017, 65, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xie, L.; Huang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, W.; Zeng, Z. Prevalence of Livestock-Associated MRSA ST398 in a Swine Slaughterhouse in Guangzhou, China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 914764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, K. Prevalence of M RSA Nasal Carriage in Patients Admitted to a Tertiary Care Hospital in Southern India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, DC11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerri, J.; Monecke, S.; Borg, M.A. Prevalence and characteristics of community carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Malta. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2013, 3, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Yang, H.-J.; Fang, Y.-P.; Chang, Y.-F.; Tzeng, S.-L.; Lu, M.-C. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among nasal carriage strains isolated from emergency department patients and healthcare workers in central Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svent–Kucina, N.; Pirs, M.; Kofol, R.; Blagus, R.; Smrke, D.M.; Bilban, M.; Seme, K. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from skin and soft tissue infections samples and healthy carriers in the Central Slovenia region. APMIS 2016, 124, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainous, A.G. Nasal Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant S aureus in the United States, 2001–2002. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006, 4, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, M.; Hajikhani, B.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D.; Van Belkum, A.; Goudarzi, M. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 20, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Wieler, L.; Witte, W. Livestock-Associated MRSA: The Impact on Humans. Antibiotics 2015, 4, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Gamberini, S.; Baldassarri, L.; Montanaro, L. Prevalence of cna, fnbA and fnbB adhesin genes among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from orthopedic infections associated to different types of implant. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 246, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartford, O.M.; Wann, E.R.; Höök, M.; Foster, T.J. Identification of Residues in the Staphylococcus aureus Fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM Clumping Factor A (ClfA) That Are Important for Ligand Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 2466–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.; Friedrich, A.W.; Lubritz, G.; Weilert, M.; Peters, G.; Von Eiff, C. Prevalence of Genes Encoding Pyrogenic Toxin Superantigens and Exfoliative Toxins among Strains of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Blood and Nasal Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 1434–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilczyszyn, W.M.; Sabat, A.J.; Akkerboom, V.; Szkarlat, A.; Klepacka, J.; Sowa-Sierant, I.; Wasik, B.; Kosecka-Strojek, M.; Buda, A.; Miedzobrodzki, J.; et al. Clonal Structure and Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Strains from Invasive Infections in Paediatric Patients from South Poland: Association between Age, spa Types, Clonal Complexes, and Genetic Markers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151937, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; You, Y.; Wu, Q.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Hu, Y.; et al. A food poisoning caused by ST7 Staphylococcal aureus harboring sea gene in Hainan province, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1110720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtfreter, S.; Grumann, D.; Schmudde, M.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Eichler, P.; Strommenger, B.; Kopron, K.; Kolata, J.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S.; Steinmetz, I.; et al. Clonal Distribution of Superantigen Genes in Clinical Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2669–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangvik, M.; Olsen, R.S.; Olsen, K.; Simonsen, G.S.; Furberg, A.-S.; Sollid, J.U.E. Age- and gender-associated Staphylococcus aureus spa types found among nasal carriers in a general population: The Tromso Staph and Skin Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4213–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijnders, M.I.A.; Deurenberg, R.H.; Boumans, M.L.L.; Hoogkamp-Korstanje, J.A.A.; Beisser, P.S.; Stobberingh, E.E. Population Structure of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated from Intensive Care Unit Patients in The Netherlands over an 11-Year Period (1996 to 2006). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 4090–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclercq, R.; Cantón, R.; Brown, D.F.J.; Giske, C.G.; Heisig, P.; MacGowan, A.P.; Mouton, J.W.; Nordmann, P.; Rodloff, A.C.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, G.; Piemont, Y.; Godail-Gamot, F.; Bes, M.; Peter, M.-O.; Gauduchon, V.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J. Involvement of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin--Producing Staphylococcus aureus in Primary Skin Infections and Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 29, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, M.; Wang, G.; Johnson, W.M. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Genes for Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins, Exfoliative Toxins, Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin 1, and Methicillin Resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 1032–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Boye, K.; De Lencastre, H.; Deplano, A.; Enright, M.C.; Etienne, J.; Friedrich, A.; Harmsen, D.; Holmes, A.; Huijsdens, X.W.; et al. High Interlaboratory Reproducibility of DNA Sequence-Based Typing of Bacteria in a Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frénay, H.M.E.; Bunschoten, A.E.; Schouls, L.M.; Leeuwen, W.J.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; Verhoef, J.; Mooi, F.R. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 15, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.