Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) has been classically considered a microvascular disease with all diagnostic and therapeutic resources focusing on its vascular components. However, during the past years, the obtained evidence highlighted the critical pathogenic role of early neuronal impairment redefining DR as a neurovascular complication. Retinal neurodegeneration is triggered by chronic hyperglycemia, which activates harmful biochemical pathways that lead to oxidative stress, metabolic overload, glutamate excitotoxicity, inflammation, and neurotrophic factor deficiency. These drivers of neurodegeneration can precede detectable vascular abnormalities. Simultaneously, endothelial injury, pericyte loss, and breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier compromise neurovascular unit integrity and establish a damaging cyclic loop in which neuronal and vascular dysfunctions reinforce each other. The interindividual variability of these processes highlights the need to properly redefine patient phenotyping by using advanced imaging and functional biomarkers. This would allow early detection of neurodegeneration and patient subtype classification. Nonetheless, translation of therapies based on neuroprotection has been limited by classical focus on vascular impairment. To meet this need, several strategies are emerging, with the most promising being those delivered through innovative ocular routes such as topical formulations, sustained-release implants, or nanocarriers. Future advances will depend on proper guidance of these therapies by integrating personalized medicine with multimodal biomarkers.

1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the most frequent complications of diabetes and the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness among the working-age population in the most developed countries [1,2]. Classically, DR has been considered a microvascular disease, which was mainly characterized by vascular leakage, ischemia, and neovascularization [3]. In accordance with this, most current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have been designed to address vascular abnormalities, including treatments such as laser photocoagulation or intravitreal injections against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [4].

Nevertheless, growing evidence indicates that retinal neurodegeneration is an early and critical event in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinal disease [5,6]. Deficits in the functionality of retinal neurons, particularly in ganglion and amacrine cells, occur before vascular lesions become detectable [5,6]. The main pathological mechanisms behind neurodegeneration are oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, chronic low-grade inflammation, and neurotrophic factor deficiency, all of which contribute to neuronal dysfunction, apoptosis, and visual function impairment [7,8,9]. For all these reasons, DR was redefined as a neurovascular complication [10].

Despite this emerging understanding, the neurodegenerative component of diabetic retinal disease remains under-recognized in clinical practice. There is a pressing need for more refined retinal phenotyping in patients with diabetes, incorporating advanced imaging modalities and functional biomarkers beyond microvascular imaging that can detect neurodegeneration at its earliest stages [11,12,13,14]. Such approaches will allow a more precise classification of disease subtypes, help identify patients at highest risk of progression, and open the door to personalized therapeutic strategies [12,13].

Neuroprotection represents a promising medical solution for the treatment of diabetic retinal disease; however, it remains an unmet medical need. While current therapies are predominantly focused on vascular impairment, novel therapeutic strategies that target neuronal survival pathways have the potential to transform the current treatment paradigm, especially those that can be administered via innovative non-invasive routes, such as topical eye drops [15].

This review aims to summarize the pathogenic mechanisms behind the neurodegenerative process that diabetes induces in the retina to outline and discuss the emerging neuroprotective strategies and to highlight the relevance of an improved retinal phenotyping in patients with diabetes. The review focuses on the earliest stages of diabetic retinal disease, in which neuronal dysfunction and neurovascular unit (NVU) impairment precede clinically detectable ischemia, neovascularization, and proliferative disease.

2. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Diabetes-Induced Retinal Neurodegeneration

Diabetic retinal disease is increasingly recognized as a condition where neuronal, glial, and vascular dysfunctions interact from the earliest stages [13,16]. Neurodegenerative changes may occur before or in parallel with classical microvascular anomalies and involve retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), amacrine cells, bipolar cells, photoreceptors, and their glia (Müller cells) [7,16]. The mechanisms that trigger the neurodegenerative process are multifactorial and interact with each other. Briefly, chronic hyperglycemia and metabolic stress promote oxidative stress, accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), mitochondrial dysfunction, glutamate excitotoxicity, microglial activation, and loss of neurotrophic support, all of which contribute to progressive neuronal dysfunction and cell death [9,13,17,18,19].

Meanwhile, hyperglycemia damages endothelial cells and pericytes, causing the breakdown of the inner and outer blood–retinal barrier (BRB), capillary occlusion, and ischemia [7,13]. Hypoxia stimulates VEGF production, which leads to vascular leakage, macular edema, and neovascularization [20,21]. These vascular abnormalities, in turn, exacerbate the neurodegenerative process by worsening ischemia and inflammation, creating a vicious cycle. For that reason, DR is defined as a neurovascular disorder where vascular and neuronal dysfunctions evolve simultaneously and amplify each other, ultimately leading to progressive vision loss [7,22].

2.1. Hyperglycemia: Underlying Mechanism in Early Neuronal Impairment

Retinal neurons are considered one of the most metabolically demanding cell types in the body, as they require a continuous glucose supply to satisfy their high energy demands. Glycolysis is their most immediate and accessible source of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), independently of oxygen availability or intracellular compartmentalization [23,24,25]. This strong dependence on glucose metabolism is essential for visual function, but it makes retinal neurons highly vulnerable to glucose fluctuations. As a result, neuronal impairment is one of the earliest consequences of hyperglycemia in DR [26,27].

Under diabetic conditions, chronic hyperglycemia increases the glycolytic flux generating excess intermediates that trigger four major damaging pathways: protein kinase C (PKC), hexosamine, polyol, and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) [28].

- -

- PKC pathway: When glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate levels increase, diacylglycerol (DAG) synthesis is enhanced activating PKC isoforms (α, β, δ, ε). In neurons, PKC dysregulation alters ion channel activity, neurotransmitter release, and calcium homeostasis, contributing to excitotoxic signaling and neuronal death. PKC-driven oxidative imbalance and pro-inflammatory signaling also compromise neuron–glia communication [29,30].

- -

- Hexosamine pathway: When fructose-6-phosphate is accumulated, it increases its flux into the hexosamine pathway, which produces an excess of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. This overproduction leads to abnormal glycosylation of neuronal proteins and transcription factors, consequently disrupting normal gene expression and synaptic protein function. The hyperactivation of the hexosamine pathway has been associated with an increase in ROS levels, mitochondrial impairment, and reduced neuronal survival under stress conditions [29,31].

- -

- Polyol pathway: Hexokinase enzyme saturates due to the hyperglycemic state, and aldose reductase converts the excess of glucose into sorbitol by oxidizing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+/NADH) phosphate (NADPH) to NADP+ [32]. Sorbitol is then metabolized by sorbitol dehydrogenase to fructose using NAD+ as cofactor. Sorbitol accumulation causes osmotic stress [33], while NADPH reduction impairs glutathione regeneration and increases oxidative stress. Excessive sorbitol oxidation raises the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which inhibits glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and promotes DAG-mediated PKC activation and AGE formation [34]. Excess NADH can also fuel NADH oxidase, increasing ROS generation [28], while fructose metabolism produces potent glycation agents that further contribute to AGE [34]. Neurons express aldose reductase (particularly retinal ganglion cells), making them highly susceptible to polyol pathway activation [33].

- -

- AGEs pathway: Chronic hyperglycemia promotes the non-enzymatic glycation of neuronal proteins and lipids. AGEs interact with RAGE, which is expressed in ganglion cells and glia, and activates oxidative and inflammatory cascades that impair neuronal viability. In Müller cells, AGEs-RAGE signaling further compromises neuronal support by promoting VEGF release, inflammation, and gliosis [glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) upregulation], aggravating neurodegeneration [28,35,36,37].

Although PKC activation, polyol flux, hexosamine pathway, and AGE accumulation are all implicated in DR, their individual quantitative contribution cannot be precisely determined, as these pathways act in parallel and converge on common downstream mechanisms. Through early metabolic stress, this convergence leads to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, osmotic imbalance, abnormal protein modifications, and inflammatory signaling. Together, these processes disrupt neuronal homeostasis, compromise synaptic function and neuronal survival at very early stages of the disease, placing neurodegeneration at the forefront of early DR, even before classical vascular abnormalities are established.

2.2. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction represent early and sustained events in DR. Retinal ganglion cells are particularly vulnerable due to their high metabolic demand, while Müller glia and microglia are responsible of amplifying oxidative and inflammatory responses, contributing to early neuronal dysfunction and progression of retinal neurodegeneration [38].

The activation of all the aforementioned pathways leads to ROS overproduction and redox imbalance. Meanwhile, higher glucose flux raises electron transport chain and electron leak increasing the levels of mitochondrial superoxide anion [39]. Consequently, mitochondrial dynamics (fusion/fission, mitophagy) are impaired, and damaged mitochondria are accumulated, further increasing ROS production and damaging mitochondrial DNA/lipids/proteins [40].

Independently of mitochondrial ROS production, NADPH oxidases (NOXs), especially NOX2, are upregulated and hyperactivated in retinal cells due to high glucose levels and inflammation, aggravating the redox imbalance by producing cytosolic superoxide anion [41]. Under hyperglycemic conditions, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1), a small signaling protein, becomes activated and facilitates the assembly of the NOX2 complex by recruiting its cytosolic subunits to the membrane-bound components. Once assembled, NOX2 transfers electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen, producing superoxide anion, which can give rise to other ROS [42]. Cyclooxygenases (COXs), lipoxygenases, and xanthine oxidases also contribute to the production of cytosolic ROS [43,44,45].

Although the retinal NVU has robust antioxidant defenses, chronic hyperglycemia compromises its efficiency increasing the oxidative imbalance. These include both enzymatic (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, etc.) and non-enzymatic antioxidants, along with repair systems that target oxidized molecules [29,46]. The reduced antioxidant activity in DR has been associated with impaired signaling of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a transcription factor that normally activates antioxidant gene expression via antioxidant response elements (DNA sequences in the promoter regions of antioxidant genes). Additionally, there are studies linking hyperglycemia with the inhibition of NRF2 expression, particularly in Müller cells, thereby promoting oxidative stress [47,48].

In parallel with mitochondrial dysfunction, increasing evidence supports a role for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in diabetes-induced retinal neurodegeneration. Chronic hyperglycemia disrupts ER homeostasis, leading to persistent activation of the unfolded protein response, which amplifies oxidative stress, calcium imbalance, and pro-apoptotic signaling in retinal neurons and glial cells. Recent global analyses of research trends in retinal diseases identify ER stress as a key mechanism linking metabolic stress to retinal neurodegeneration, reinforcing its relevance in diabetic retinopathy [49].

2.3. Glutamate Excitotoxicity and Neurotransmitter Imbalance

Glutamate is the main neurotransmitter in the retinal visual pathway and has an essential role in synaptic transmission but becomes neurotoxic at elevated levels (excitotoxicity) by overstimulation of its receptors, leading to neuronal death. Glutamate clearance relies on Müller cell uptake via glutamate aspartate transporter 1 (GLAST) and conversion to glutamine by glutamine synthetase, maintaining the glutamate–glutamine cycle [50]. In experimental DR, it has been observed that the expression of genes involved in glutamate transport, including GLAST in Müller cells, is reduced [51,52]. Retinal ganglion cells are particularly susceptible to glutamate excitotoxicity [53].

Diabetes can also disrupt synaptic machinery, lowering the levels of presynaptic proteins such as synaptophysin, synapsin I, or syntaxin 1A, which are critical for neurotransmitter release and synaptic maintenance. These reductions have been reported in animal models and postmortem human retinas and can be attributed to a deterioration of retrograde axonal transport in retinal ganglion cells [54,55,56,57].

Together, alterations in glutamate clearance, the excitotoxicity resulting from its accumulation, and the resulting synaptic dysfunction create an environment of increased neuronal stress in the diabetic retina. These alterations are increasingly recognized as early contributing factors to the pathogenesis of RD and may occur in parallel with, or even before, detectable vascular abnormalities.

2.4. Inflammation and Microglial Activation

Chronic hyperglycemia triggers the initial pathological mechanisms that lead to oxidative and metabolic stress in the retina, which in turn activate inflammatory pathways that promote the release of cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators that initiate a cascade of glial cell activation. Microglia, the resident macrophages of the retina, become activated and release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), contributing to retinal inflammation and neuronal damage [58,59].

Müller cells, the principal glial cells in the retina, also undergo reactive gliosis in response to hyperglycemic stress. This gliosis involves changes in gene expression and cellular morphology, which consequently alter its supportive functions, mainly glutamate uptake and potassium buffering, and promotes the release of inflammatory mediators [60]. Astrocytes, another type of glial cell, contribute to the inflammatory environment by releasing cytokines and ROS, further exacerbating neuronal injury and disrupting the BRB [61,62].

Collectively, the activation of microglia, Müller cells, and astrocytes creates a pro-inflammatory milieu that accelerates neuronal dysfunction and contributes to the early stages of neurodegeneration in DR.

Beyond associative observations, experimental studies provide mechanistic and causal evidence for the involvement of inflammation and microglial activation in neurodegeneration. Genetic modulation of key inflammatory and innate immune pathways reduces microglial activation, oxidative stress, and retinal neuronal loss in diabetic models [63]. In parallel, pharmacologic modulation of inflammatory signaling further supports a causal role for inflammation by attenuating neuronal dysfunction and neurovascular unit impairment in experimental diabetes [64]. Although direct genetic evidence in humans remains limited, these convergent findings support inflammation as an active contributor to early neuronal dysfunction in diabetic retinal disease.

2.5. Neurotrophic Factor Deficiency

The low retinal production of neuroprotective factors associated with diabetes compromises the capacity of arresting the neurodegenerative process. Among the factors involved are pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), somatostatin (SST), interstitial retinol-binding protein (IRBP), or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) [62,65,66,67]. Under physiological conditions, PEDF is synthesized by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and plays a crucial role in retinal homeostasis by preventing oxidative stress and glutamate excitotoxicity [68]. SST, which is also mainly produced by the RPE, has antiangiogenic and neuroprotective properties [69]. Furthermore, IRBP is synthesized by photoreceptors and is essential for their survival and maintenance [70,71]. Additionally, neurotrophic factors like VEGF and erythropoietin (EPO) are overexpressed in the diabetic retina, potentially counteracting this reduction in neuroprotective factors. Other factors, including insulin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), and nerve growth factor (NGF) might also have an important role in the neurodegenerative process that occurs in DR [62,72,73]. In fact, BDNF has emerged as a key regulator of retinal neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity. A recent systematic review integrating clinical, pathological, and experimental evidence demonstrated that BDNF levels are consistently altered in diabetic retinopathy, particularly at early stages, and are associated with retinal neurodegeneration and functional impairment rather than with advanced vascular pathology [74]. These findings support the concept that impaired BDNF signaling contributes to early neuronal dysfunction in diabetic retinal disease and highlight its potential value as both a biomarker and a therapeutic target.

2.6. Vascular–Neuronal Interactions (Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction)

NVU integrates neurons, endothelial cells, and pericytes to ensure homeostasis, coupling neuronal activity with vascular supply, and preserving BRB integrity [7]. In DR, hyperglycemia and oxidative stress can directly affect vascular cells too, causing early endothelial dysfunction and pericyte dropout, even before that microvascular lesions can clinically be detected [75,76]. Pericyte loss destabilizes retinal capillaries, impairs endothelial survival signaling, and disrupts proper myogenic response, making neurons more vulnerable to changes in blood flow and pressure [77].

Endothelial injury is characterized by downregulation of tight-junction proteins such as occludin and claudin-5, which increases BRB permeability and facilitates leakage of plasma proteins into the retinal parenchyma [78]. These extravasated molecules exert direct neurotoxic effects, amplifying oxidative stress and promoting neuronal apoptosis [79]. At the same time, neuronal hyperactivity and metabolic stress increase oxygen demand, but impaired functional hyperemia interferes with the ability of retinal blood vessels to adapt adequately to blood flow, leading to hypoxia and accelerating neuronal dysfunction [15].

This interplay establishes a vicious cycle: vascular instability compromises neuronal survival, while stressed or dying neurons release vasoactive and pro-apoptotic mediators, such as glutamate and nitric oxide, which further damage endothelial cells and pericytes [7,80]. Glutamate accumulation has been shown to impair vascular integrity, while vascular leakage introduces neurotoxic agents like fibrinogen into the neural retina, worsening neurodegeneration [50,80,81]. Therefore, vascular impairment within the NVU not only occurs in parallel to neuronal dysfunction, but it also actively exacerbates the process, consequently creating a self-reinforcing loop that accelerates the progression of the disease.

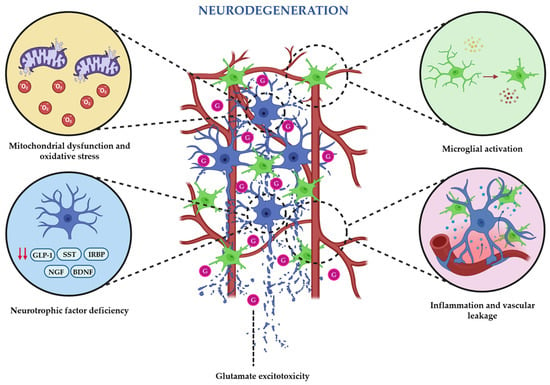

In summary, all the addressed pathophysiological mechanisms illustrate that chronic hyperglycemia initiates a cascade of metabolic, oxidative, and inflammatory alterations that trigger early retinal neurodegeneration, while excitotoxicity and neurotrophic support deficiencies further compromise neuronal integrity (Figure 1). As vascular instability and BRB breakdown emerge, neuronal and vascular dysfunctions reinforce each other, ultimately resulting in a progressive damaging neurovascular cycle that ultimately accelerates the development of DR.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the main pathophysiological mechanisms that trigger and maintain the neurodegenerative state that occur during the earliest stages of diabetic retinopathy.

3. Retinal Phenotyping in Diabetic Patients

DR has been classified by the vascular abnormalities, which are visible by means of direct or indirect fundus exam [81]. Currently two classifications are used: the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) classification [82], which is used in clinical trials and research and the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy (ICDR) Severity Scale, which is a simplification of the first one and more usable in clinical practice. Advances in imaging technology and in the understanding of DR pathogenesis urges for new phenotyping approaches [83].

New retinal imaging approaches like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) have contributed to characterizing the diabetic macular edema (DME). OCT biomarkers have been proposed to predict the response to different treatments in diabetic macular edema [84,85]. For example, the disorganization of the retinal inner layers [86] or the disruption of the external limiting membrane [87] have been associated with poorer visual acuity responses to treatment. Furthermore, cytokines and inflammatory markers in serum, vitreous or even aqueous humor have been proposed to determine the prognosis and the responses to treatment of DME [88]. In addition, the assessment of different biomarkers in the aqueous humor has been proposed to predict the response to the two main therapeutic options in DME: corticosteroids (for those subjects with more inflammatory markers) or anti-VEGF (when the expression of VEGF dominates) [89]. However, more prospective studies are needed to implement all this information in the clinical practice towards a personalized medicine.

Regarding the pathogenesis of DR, it is now not only considered a merely vascular disease, but a neurovascular disease where neurodegeneration plays an important role. Neurodegeneration can be detected before vascular changes are evident by OCT or by functional tests like electroretinogram. In fact, new approaches for early treatment of DR include the use of neuroprotective agents [65]. Simó et al. conducted a clinical trial designed to arrest the progression of DR in early stages using eye drops of somatostatin (the European Consortium for Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy or EUROCONDOR trial). One of the main lessons of this trial was that neurodegeneration (at least when assessed by multifocal electroretinography) was not identified in a significant proportion (35%) of patients with early microvascular impairment (ETDRS 20-34) [90,91]. Thus, neurodegeneration may represent an early indicator of diabetic retinopathy only in a specific group of individuals with diabetes. This observation underscores the importance of screening for retinal neurodysfunction to identify patients who could benefit from neuroprotective therapies. The future implications of these two phenotypes have not yet been explored. In fact, there is an initiative towards a proposal of a new approach for the staging of DR that considers the presence of neurodegeneration and macular edema [92].

In the future, the impact of genome studies or the analysis of OCT and/or retinal images by IA could contribute to the definition of new retinal phenotypes that could not only been related to DR but also to systemic diseases such dementia or cardiovascular disease [93,94].

4. Therapeutic Strategies Based on Neuroprotection

4.1. New Emerging Neuroprotective Agents

Neurodegeneration is now recognized as an early and key component of DR, often preceding microvascular lesions and contributing to inflammation, vascular leakage, and vision loss [5,95]. Multiple experimental studies have evidenced the efficacy of promising neuroprotective strategies targeting different stages of the neurodegenerative process, such as oxidative stress, synaptic impairment, or neurotrophic factors deficiency, among others [5,95]. However, translation to patients has been limited [15,91,96,97]. A key reason is that clinical trials and regulatory endpoints have focused almost exclusively on vascular changes, ignoring neurodegeneration. Updating the DR staging system to include neuronal damage could pave the way for trials that adequately evaluate neuroprotective therapies and allow them to complement existing treatments focused on the vascular components of the disease [98,99,100].

The search for neuroprotective therapies in DR has grown considerably in the past decade, moving beyond glucose control and vascular endpoints to focus on mechanisms that directly benefit retinal neurons [15,65]. A mechanistic classification provides a clearer framework for understanding how diverse agents intervene in the complex pathophysiology of early DR and converge to drive neurodegeneration.

4.1.1. Antioxidants and Mitochondrial Protectors

ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction have a key role in neuronal injury in DR. Classical antioxidants such as α-lipoic acid (ALA) improve mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative damage, and preserve retinal structure and electrophysiology in experimental diabetes [101,102]. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as SkQ1 selectively accumulate within mitochondria and prevent ganglion cell loss, preserving retinal integrity in diabetic and senescence-accelerated rat models [103]. Pharmacological activation of NRF2, the main regulator of antioxidant defenses, has exhibited promising results too. Sulforaphane restored antioxidant enzyme activity and improved retinal function in diabetic models through NRF2-dependent mechanisms [104]. Together, these strategies aim not only to scavenge ROS but to restore mitochondrial redox balance and prevent neuronal apoptosis.

4.1.2. Therapeutic Approaches Targeting the Reduction in Excitotoxicity and the Preservation of Synapses

The excitotoxicity caused by glutamate accumulation is one of the main contributors of retinal neuronal loss in diabetes. Brimonidine, an α2-adrenergic agonist, can inhibit this glutamate accumulation and its detrimental effects by reducing glutamate release and activating pro-survival mechanisms (PI3K/Akt, ERK). In the EUROCONDOR trial, topical brimonidine preserved retinal function in patients with early DR [91,105]. Citicoline (CDP-choline) is able to stabilize neuronal membranes, enhance mitochondrial bioenergetics, and improve pattern electroretinogram responses, delaying neurodegeneration in small human and animal studies [106,107,108]. NMDA receptor antagonists, such as memantine, attenuate calcium influx and excitotoxic damage, demonstrating neuroprotection in diabetic rodents, although systemic side effects have limited clinical translation [109]. All these treatments aim to maintain synaptic integrity and prevent early neuronal dysfunction.

4.1.3. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Agents

Inflammation amplifies the neurodegenerative cascades of DR. SOCS1-derived peptides, when applied topically, inhibit JAK/STAT signaling, and are able to prevent glial activation and vascular leakage in diabetic models [110]. Minocycline is an antibiotic modulator of the microglia that decreases TNF-α, IL-1β and oxidative stress, resulting in the protection of retinal neurons in diabetic rodents [111]. Palmitoylethanolamide acts on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) to suppress glial reactivity and inflammation, improving retinal structure and function in experimental diabetes [112]. In addition, the inhibition of P2X7 purinergic receptors, which are mediators of inflammasome activation, reduces neuronal apoptosis in the diabetic retina [113]. These results support that inflammation control is a relevant neuroprotective approach in DR.

4.1.4. Vasoactive and Neurovascular Protectors

Given the close interrelationship of neuronal and vascular compartments, therapies that improve microvascular health can also confer neuroprotection. Calcium dobesilate is a vasoactive and antioxidant compound that has demonstrated efficacy in reducing vascular permeability, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity in the diabetic retina, although clinical results are heterogeneous [114]. Another neurovascular protector is bosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, which improves retinal perfusion and reduces neuronal cell death in diabetic models, indicating that retinal blood flow normalization can indirectly protect neurons [115].

4.1.5. Therapies Based on Neurotrophic and Growth Factors

Loss of neurotrophic support is a hallmark of DR. Somatostatin, normally secreted by retinal neurons, is markedly reduced in diabetes; topical somatostatin analogs have shown neuroprotective effects both experimentally and in the EUROCONDOR clinical trial [91,105].

CNTF and BDNF promote retinal ganglion cell survival in diabetic models when delivered via encapsulated-cell technology or viral vectors [116]. PEDF, an anti-angiogenic and neuroprotective protein downregulated in DR, prevents oxidative stress and apoptosis when supplemented topically [117]. NGF eye drops prevent neurodegeneration in experimental diabetes [118]. Erythropoietin (EPO), beyond its hematopoietic role, protects against neuronal apoptosis when delivered locally to the retina [119].

GLP-1 and its receptor (GLP-1R) form an endogenous neurotrophic system in the retina. GLP-1 and GLP-1R expression is downregulated in diabetic retina, contributing to increased oxidative stress and neuronal vulnerability [66]. Activation of GLP-1R with liraglutide or exendin-4 triggers PI3K/Akt and CREB survival pathways upregulates BDNF and reduces apoptosis and gliosis [66,120,121].

Enhancing endogenous GLP-1 signaling through DPP-4 inhibitors, such as sitagliptin, has also demonstrated retinal neuroprotection [117,118,119]. Recent studies showed that sitagliptin eye drops reach the retina and prevent neurovascular unit impairment without systemic effects (glycemia and body weight) [122,123,124]. In addition, GLP-1R activation has been found to prevent the downregulation of presynaptic proteins involved in vesicle biogenesis and mobilization in diabetic retinas. Additionally, GLP-1R has shown to protect against diabetes-induced retinal thinning. These neuroprotective effects are associated with the improvement of retinal function assessed by electroretinography (ERG). To date, retinal neuroprotection by GLP-1R agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors has been demonstrated only in experimental models. Systemic therapies provide indirect translational support, whereas topical formulations remain preclinical [122,123,124].

Beyond retinal experimental models, recent narrative reviews highlight that GLP-1 receptor agonists exert pleiotropic neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects across multiple diabetes-associated comorbidities, reinforcing the translational relevance of GLP-1R activation as a clinically attractive pathway for retinal neurodegeneration [125].

These findings support GLP-1 as a key neurotrophic and metabolic factor whose replacement may prevent early neuronal loss in DR.

Table 1 summarizes neuroprotective candidates investigated in early DR, highlighting their preclinical neuroprotective effects, primary mechanisms of action, cellular targets, and stage of evaluation.

Table 1.

Summary of agents that have demonstrated neuroprotective effects in experimental models of early DR. Agents are listed in the order of appearance in Section 4.

4.2. Novel Delivery Routes

Effective retinal delivery of neuroprotective agents remains a major challenge due to ocular barriers, including the cornea, sclera, and BRB. To overcome these limitations, several novel drug delivery systems have been investigated to enhance retinal bioavailability, prolong therapeutic effects, and reduce systemic exposure.

Intravitreal injections are the most direct route to deliver drugs to the retina, allowing high local concentrations of neuroprotective agents. However, the invasiveness of this delivery route has been associated with adverse effects including endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and patient discomfort. To overcome these issues, sustained-release intravitreal implants have been developed, which can continuously release therapeutic agents over weeks to months, reducing the frequency of injections while maintaining effective drug levels. For instance, biodegradable implants have been studied for the delivery of corticosteroids and neurotrophic factors, demonstrating prolonged retinal exposure and neuroprotective effects [126].

Topical eye drops, traditionally limited by poor penetration to the posterior segment, have gained renewed interest through novel formulations [127]. One of the innovative strengths of this route is that it allows the drug to be delivered in a much safer way without losing efficacy. In addition, it allows self-administration, reducing visits, and medical interventions [128]. However, errors in self-administration of eye drops may occur, increasing the risk of therapeutic failure. Despite this, with proper patient education on long-term administration of eye drops this issue can be overcome [129].

Another innovative approach that has recently emerged is the suprachoroidal delivery, which consists of injecting drugs into the space between the sclera and choroid. This technique achieves high posterior segment drug concentrations while minimizing exposure to the anterior segment and systemic circulation. It is particularly suitable for delivering biologics and large-molecule neuroprotective agents, providing targeted and sustained retinal exposure [130].

Carriers based on nanotechnology have also been widely explored for retinal neuroprotection. Liposomes, dendrimers, and polymeric nanoparticles can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs and protect them from degradation and enabling controlled release. The engineering of magnetic nanoparticles has allowed targeted delivery with external guidance to all retinal layers for localized treatment. These strategies enhance the stability, bioavailability, and efficacy of neuroprotective agents [130].

Thermoresponsive hydrogels are an emerging drug delivery system designed for the posterior segment of the eye. These materials are liquids at room temperature, allowing injection through fine needles and quickly form gels at body temperature, creating a localized drug reservoir. This gel gradually releases therapeutic agents, such as anti-VEGF proteins, enabling sustained treatment over weeks or months. This approach addresses the limitations of frequent intravitreal injections, reducing complications and improving patient compliance. By controlling polymer composition and gel properties, drug release can be finely tuned, making thermoresponsive hydrogels a promising minimally invasive platform for chronic retinal disease management [131].

Stem cell-based therapies offer a biological method of drug delivery, as transplanted stem cells can secrete neurotrophic factors locally within the retina. Intravitreal or subretinal transplantation allows sustained release of neuroprotective agents, potentially repairing or preserving retinal neurons in diabetic eyes [132].

Finally, biodegradable microparticles have been investigated as vehicles for sustained drug delivery. These particles encapsulate neuroprotective agents and release them gradually as the polymer degrades, providing controlled and prolonged retinal exposure when administered intravitreally [127].

In summary, the development of novel ocular delivery routes, ranging from intravitreal implants and eye drops to suprachoroidal injections, nanocarriers, thermorespobsive hydrogels, and stem cell-based systems, offers promising strategies for neuroprotection in DR. By overcoming ocular barriers, enabling targeted and sustained release, and minimizing systemic side effects, these approaches have the potential to preserve retinal function, reduce treatment burden, and improve long-term visual outcomes.

4.3. Personalized Medicine: Patient Stratification and Targeted Therapies

Personalized neuroprotection in DR addresses the heterogeneity of retinal neurodegeneration, which often precedes visible vascular damage, by adapting interventions based on functional assessments, advanced imaging, and systemic or ocular biomarkers [133,134]. However, several limitations make widespread implementation difficult. Reliable and standardized biomarkers for early neurodegeneration are still lacking, and many functional or imaging techniques, such as ERG and OCT angiography, may not be routinely available in all clinical settings [135,136]. Stratifying patients accurately requires longitudinal data and complex interpretation, which can be resource-intensive. Furthermore, evidence from animal models demonstrates early neuronal dysfunction and synaptic alteration before cell death, but translation to human disease remains uncertain [137,138]. The long-term safety, optimal dosing, and sustained efficacy of many neuroprotective agents, particularly the newest therapies, are not yet established [91]. Patient adherence, comorbidities, and variability in metabolic control further complicate individualized strategies. Finally, integrating personalized neuroprotection into routine practice demands robust predictive models and clinical decision support systems, which are not yet fully developed [139]. Despite these challenges, targeted approaches combining neuroprotection with metabolic management and lifestyle interventions hold promise for preserving retinal neuronal function and preventing vision loss in high-risk patients.

5. Future Perspectives and Unmet Needs

Future advances in neuroprotection for DR will rely on the capacity of integrating retinal phenotyping with molecular biomarkers, allowing early detection and precise patient stratification. By combining advanced imaging tools, such as OCT angiography and adaptive optics, with biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain, GFAP, or AGEs, it may be possible to distinguish between patients with predominantly neurodegenerative or vascular phenotypes, thereby facilitating individualized treatment [134,135]. Another critical need is the redesign of clinical trials to focus on neuronal endpoints. Most current studies emphasize vascular outcomes, whereas early neuronal dysfunction often predicts visual decline. Future trials should incorporate multimodal endpoints that combine functional (ERG, microperimetry) and structural (OCT) measures, alongside molecular indicators of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [91,140]. Additionally, a shift toward combined vascular and neuronal therapeutic approaches is essential, recognizing that the NVU functions as an integrated system. Dual-target strategies, pairing anti-VEGF, or vascular stabilizers with neurotrophic or anti-inflammatory agents would provide synergistic benefits and prevent irreversible vision loss [5,137]. Overall, advancing toward a precision medicine model that unites imaging, molecular diagnostics, and computational prediction represents the most promising path to address the unmet needs of neuroprotection in DR.

Author Contributions

O.S.-S. conceived the study concept and contributed to critically revising the manuscript; H.R. and O.S.-S. reviewed the published literature and selected the suitable studies; H.R. and O.S.-S. drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final article. H.R. and O.S.-S. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

H.R. is a recipient of a Torres Quevedo grant from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PTQ2023-013246).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 was created using BioRender. Bastida, R. (2026) https://BioRender.com/11lzb7p.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End-products |

| ALA | α-Lipoic Acid |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BRB | Blood–Retinal Barrier |

| CDP-choline | Cytidine Diphosphate Choline |

| CNTF | Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CREB | cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERG | Electroretinography |

| ETDRS | Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| EUROCONDOR | European Consortium for Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| GDNF | Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GLAST | Glutamate Aspartate Transporter 1 |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 |

| GLP-1R | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor |

| ICDR | International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IRBP | Interstitial Retinol-Binding Protein |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| NOX | NADPH Oxidase |

| NOX2 | NADPH Oxidase 2 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| NVU | Neurovascular Unit |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PEDF | Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| PPAR-α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha |

| RAC1 | Ras-Related C3 Botulinum Toxin Substrate 1 |

| RAGE | Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products |

| RD | Retinal Disease |

| RGCs | Retinal Ganglion Cells |

| RPE | Retinal Pigment Epithelium |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SkQ1 | Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant (Plastoquinone Derivative) |

| SOCS1 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 1 |

| SST | Somatostatin |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| UDP | Uridine Diphosphate |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Ting, D.S.; Cheung, G.C.; Wong, T.Y. Diabetic retinopathy: Global prevalence, major risk factors, screening practices and public health challenges: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 44, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, R.R.A.; Jonas, J.B.; Bron, A.M.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Das, A.; Flaxman, S.R.; Friedman, D.S.; E Keeffe, J.; Kempen, J.H.; Leasher, J.; et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: Magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, D.A.; Klein, R.; Gardner, T.W. Diabetic retinopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, E.J.; Sun, J.K.; Stitt, A.W. Diabetic retinopathy: Current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e93751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, E.H.; van Dijk, H.W.; Jiao, C.; Kok, P.H.; Jeong, W.; Demirkaya, N.; Garmager, A.; Wit, F.; Kucukevcilioglu, M.; van Velthoven, M.E.J.; et al. Retinal neurodegeneration may precede microvascular changes characteristic of diabetic retinopathy in diabetes mellitus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2655–E2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, H.W.; Verbraak, F.D.; Kok, P.H.; Stehouwer, M.; Garvin, M.K.; Sonka, M.; DeVries, J.H.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Abràmoff, M.D. Early neurodegeneration in the retina of type 2 diabetic patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 2715–2719, Erratum in Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 3269. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8997a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Mi, Y.; Ren, K.; Yang, D. Neurovascular unit in diabetic retinopathy: Pathophysiological roles and potential therapeutical targets. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Su, S.B. Neuroinflammatory responses in diabetic retinopathy. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, M.Y.; Yiang, G.T.; Lai, T.T.; Li, C.J. The Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction during the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 3420187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.H.; Schwartz, S.S. Diabetic Retinopathy—An Underdiagnosed and Undertreated Inflammatory, Neuro-Vascular Complication of Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, S.; Midena, E. Retinal layers changes in human preclinical and early clinical diabetic retinopathy support early retinal neuronal and Müller cells alterations. J. Diabetes Res. 2013, 2013, 905058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhablani, J.; Sharma, A.; Goud, A.; Peguda, H.K.; Rao, H.L.; Begum, V.U.; Barteselli, G. Neurodegeneration in Type 2 Diabetes: Evidence From Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 6333–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Stitt, A.W.; Gardner, T.W. Neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: Does it really matter? Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, M.H.; Marques, I.P.; Ferreira, S.; Tavares, D.; Santos, T.; Santos, A.R.; Figueira, J.; Lobo, C.; Cunha-Vaz, J. Retinal Neurodegeneration in Different Risk Phenotypes of Diabetic Retinal Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 800004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.; Dal Monte, M.; Simó, R.; Casini, G. Neuroprotection as a Therapeutic Target for Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 9508541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, B. Retinal Cell Damage in Diabetic Retinopathy. Cells 2023, 12, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Tang, P.; Lv, H. Targeting oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy: Mechanisms, pathology, and novel treatment approaches. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1571576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, P.; Luo, E. Advanced glycation end products and reactive oxygen species: Uncovering the potential role of ferroptosis in diabetic complications. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Dhankhar, S.; Chauhan, R.; Saini, M.; Singh, R.; Kumar, P.; Singh, T.G.; Chauhan, S.; Devi, S. Targeting neurotrophic dysregulation in diabetic retinopathy: A novel therapeutic avenue. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, A.; Heckman, J.; Tah, G.; Lopez, S.; Valdez, L.; Tsin, A. VEGF in Diabetic Retinopathy and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Mansoor, S.; Sharma, A.; Sapkal, A.; Sheth, J.; Falatoonzadeh, P.; Kuppermann, B.; Kenney, M. Diabetic retinopathy and VEGF. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2013, 7, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitari, T. Neurovascular Impairment and Therapeutic Strategies in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.B.; Lindsay, K.J.; Du, J. Glucose, lactate, and shuttling of metabolites in vertebrate retinas. J. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 93, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, L.; Ma, S.; Cipi, J.; Cheng, S.Y.; Zieger, M.; Hay, N.; Punzo, C. Aerobic Glycolysis Is Essential for Normal Rod Function and Controls Secondary Cone Death in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2629–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajala, A.; Bhat, M.A.; Teel, K.; Gopinadhan Nair, G.K.; Purcell, L.; Rajala, R.V.S. The function of lactate dehydrogenase A in retinal neurons: Implications to retinal degenerative diseases. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, S.X. The unfolded protein response signaling and retinal Müller cell metabolism. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Kern, T.S.; Hellström, A.; Smith, L.E.H. Fatty acid oxidation and photoreceptor metabolic needs. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Yang, C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumnamcha, T.; Guerra, M.; Singh, L.P.; Ibrahim, A.S. Metabolic Dysregulation and Neurovascular Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, P.; King, G.L. Activation of protein kinase C isoforms and its impact on diabetic complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, S.D. Biochemical changes in diabetic retinopathy triggered by hyperglycaemia: A review. Afr. Vis. Eye Health 2018, 77, a439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, S.Z.; Qvist, R.; Kumar, S.; Batumalaie, K.; Ismail, I.S. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic retinopathy, general preventive strategies, and novel therapeutic targets. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 801269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, M. The polyol pathway as a mechanism for diabetic retinopathy: Attractive, elusive, and resilient. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2007, 2007, 61038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Bali, A.; Singh, N.; Jaggi, A.S. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, C.; Jacobs, K.; Haucke, E.; Navarrete Santos, A.; Grune, T.; Simm, A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, H.; Ward, M.; Stitt, A.W. AGEs, RAGE, and diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2011, 11, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.H.; Kang, E.Y.; Lin, P.H.; Yu, B.B.; Wang, J.H.; Chen, V.; Wang, N.K. Mitochondria in Retinal Ganglion Cells: Unraveling the Metabolic Nexus and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.J.; Cascio, M.A.; Rosca, M.G. Diabetic Retinopathy: The Role of Mitochondria in the Neural Retina and Microvascular Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Mishra, M. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and diabetic retinopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A. Diabetic Retinopathy and NADPH Oxidase-2: A Sweet Slippery Road. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahajpal, N.; Kowluru, A.; Kowluru, R.A. The Regulatory Role of Rac1, a Small Molecular Weight GTPase, in the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonna, R.; Giovannelli, G.; Confalone, P.; Renna, F.V.; Geng, Y.J.; De Caterina, R. High glucose-induced hyperosmolarity contributes to COX-2 expression and angiogenesis: Implications for diabetic retinopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubitosi-Klug, R.A.; Talahalli, R.; Du, Y.; Nadler, J.L.; Kern, T.S. 5-Lipoxygenase, but not 12/15-lipoxygenase, contributes to degeneration of retinal capillaries in a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P.; Nivorozhkin, A.; Szabó, C. Therapeutic effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitors: Renaissance half a century after the discovery of allopurinol. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, H.; Bogdanov, P.; Sampedro, J.; Huerta, J.; Simó, R.; Hernández, C. Beneficial Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) in Diabetes-Induced Retinal Abnormalities: Involvement of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansanen, E.; Kuosmanen, S.M.; Leinonen, H.; Levonen, A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: Mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert-Garay, J.S.; Riesgo-Escovar, J.R.; Salceda, R. High glucose concentrations induce oxidative stress by inhibiting Nrf2 expression in rat Müller retinal cells in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Tu, Y.; Tan, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Global research trends on endoplasmic reticulum stress in retinal diseases from 2000 to 2024. Int. Ophthalmol. 2025, 45, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M. Abnormalities in glutamate metabolism and excitotoxicity in the retinal diseases. Scientifica 2013, 2013, 528940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Puro, D.G. Diabetes-induced dysfunction of the glutamate transporter in retinal Müller cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3109–3116. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J.C.; Kroes, R.A.; Moskal, J.R.; Linsenmeier, R.A. Diabetes changes expression of genes related to glutamate neurotransmission and transport in the Long-Evans rat retina. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 1538–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, I.; Lu, B.; Yang, N.; Huang, K.; Wang, P.; Tian, N. The Susceptibility of Retinal Ganglion Cells to Glutamatergic Excitotoxicity Is Type-Specific. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanGuilder, H.D.; Brucklacher, R.M.; Patel, K.; Ellis, R.W.; Freeman, W.M.; Barber, A.J. Diabetes downregulates presynaptic proteins and reduces basal synapsin I phosphorylation in rat retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ino-ue, M.; Dong, K.; Yamamoto, M. Retrograde axonal transport impairment of large- and medium-sized retinal ganglion cells in diabetic rat. Curr. Eye Res. 2000, 20, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.F.; VanGuilder, H.D.; D’Cruz, T.S.; El-Remessy, A.B.; Barber, A.J. Synapsin 1 protein expression and phosphorylation are compromised by diabetes in rodent and human retinas. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 4920. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, A.; Scheerer, M.F.; Zukunft, S.; Muschet, C.; Merl, J.; Adamski, J.; de Angelis, M.H.; Neschen, S.; Hauck, S.M.; Ueffing, M. Retinal proteome alterations in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinuthia, U.M.; Wolf, A.; Langmann, T. Microglia and Inflammatory Responses in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 564077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srejovic, J.V.; Muric, M.D.; Jakovljevic, V.L.; Srejovic, I.M.; Sreckovic, S.B.; Petrovic, N.T. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Involved in the Pathophysiology of Retinal Vascular Disease-Interplay Between Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, A.; Pannicke, T.; Grosche, J.; Francke, M.; Wiedemann, P.; Skatchkov, S.N.; Osborne, N.; Reichenbach, A. Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2006, 25, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Luo, Q.; Chen, J.; Huang, C.; Jahangir, A.; Pan, T.; Wei, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z. Retinal Astrocytes and Microglia Activation in Diabetic Retinopathy Rhesus Monkey Models. Curr. Eye Res. 2022, 47, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Hernández, C. European Consortium for the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy (EUROCONDOR). Neurodegeneration in the diabetic eye: New insights and therapeutic perspectives. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Xie, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Tian, H.; Lu, L.; Xu, J.; Xu, G.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J. Enhancing fractalkine/CX3CR1 signalling pathway can reduce neuroinflammation by attenuating microglia activation in experimental diabetic retinopathy. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Dong, L.; Pearsall, E.A.; Zhou, K.; Cheng, R.; Ma, J.X. The Protective Role of Microglial PPARα in Diabetic Retinal Neurodegeneration and Neurovascular Dysfunction. Cells 2022, 11, 3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Simó-Servat, O.; Bogdanov, P.; Hernández, C. Neurovascular Unit: A New Target for Treating Early Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.; Bogdanov, P.; Corraliza, L.; García-Ramírez, M.; Solà-Adell, C.; Arranz, J.A.; Arroba, A.I.; Valverde, A.M.; Simó, R. Topical Administration of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prevents Retinal Neurodegeneration in Experimental Diabetes. Diabetes 2016, 65, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ramírez, M.; Hernández, C.; Villarroel, M.; Canals, F.; Alonso, M.A.; Fortuny, R.; Masmiquel, L.; Navarro, A.; García-Arumí, J.; Simó, R. Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) is downregulated at early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2633–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnstable, C.J.; Tombran-Tink, J. Neuroprotective and antiangiogenic actions of PEDF in the eye: Molecular targets and therapeutic potential. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004, 23, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E.; Hernández, C.; Miralles, A.; Huguet, P.; Farrés, J.; Simó, R. Lower somatostatin expression is an early event in diabetic retinopathy and is associated with retinal neurodegeneration. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Fernandez, F.; Ghosh, D. Focus on molecules: Interphotoreceptor retinoidbinding protein (IRBP). Exp. Eye Res. 2008, 86, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Hollander, A.I.; McGee, T.L.; Ziviello, C.; Banfi, S.; Dryja, T.P.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, F.; Ghosh, D.; Berson, E.L. A homozygous missense mutation in the IRBP gene (RBP3) associated with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysona, B.A.; Shanab, A.Y.; Elshaer, S.L.; El-Remessy, A.B. Nerve growth factor in diabetic retinopathy: Beyond neurons. Expert Rev. Ophthalmol. 2014, 9, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afarid, M.; Namvar, E.; Sanie-Jahromi, F. Diabetic Retinopathy and BDNF: A Review on Its Molecular Basis and Clinical Applications. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 1602739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhoro, R.; Raffad; Durrani, M.U.; Munim, A.; Jamil, N.; Ali, M.I.; Shah, M.U. Clinicopathological Assessments of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor BDNF Physiology in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review. Pak. J. Med. Dent. 2025, 14, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, F.; You, Z.; Fu, S.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.R.; Boia, R.; Aires, I.D.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Fernandes, R. Sweet Stress: Coping with Vascular Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes, H.P.; Lin, J.; Renner, O.; Shani, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Betsholtz, C.; Brownlee, M.; Deutsch, U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 2002, 51, 3107–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, E.C.; Martins, J.; Voabil, P.; Liberal, J.; Chiavaroli, C.; Bauer, J.; Cunha-Vaz, J.; Ambrósio, A.F. Calcium dobesilate inhibits the alterations in tight junction proteins and leukocyte adhesion to retinal endothelial cells induced by diabetes. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2637–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Remessy, A.B.; Behzadian, M.A.; Abou-Mohamed, G.; Franklin, T.; Caldwell, R.W.; Caldwell, R.B. Experimental diabetes causes breakdown of the blood-retina barrier by a mechanism involving tyrosine nitration and increases in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 162, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldosari, D.I.; Malik, A.; Alhomida, A.S.; Ola, M.S. Implications of Diabetes-Induced Altered Metabolites on Retinal Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 938029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, A.J.; Gardner, T.W.; Abcouwer, S.F. The significance of vascular and neural apoptosis to the pathology of diabetic retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tan, T.E.; Shao, Y.; Wong, T.Y.; Li, X. Classification of diabetic retinopathy: Past, present and future. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1079217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 766–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C.P.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Klein, R.E.; Lee, P.P.; Agardh, C.D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J.T. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, D.; Iglicki, M.; Busch, C.; Invernizzi, A.; Mariussi, M.; Loewenstein, A. International Retina Group. OCT Biomarkers as Functional Outcome Predictors in Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Dexamethasone Implant. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.K.; Lin, M.M.; Lammer, J.; Prager, S.; Sarangi, R.; Silva, P.S.; Aiello, L.P. Disorganization of the retinal inner layers as a predictor of visual acuity in eyes with center-involved diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muftuoglu, I.K.; Mendoza, N.; Gaber, R.; Alam, M.; You, Q.; Freeman, W.R. INTEGRITY OF OUTER RETINAL LAYERS AFTER RESOLUTION OF CENTRAL INVOLVED DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA. Retina 2017, 37, 2015–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markan, A.; Agarwal, A.; Arora, A.; Bazgain, K.; Rana, V.; Gupta, V. Novel imaging biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 12, 2515841420950513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udaondo, P.; Hernández, C.; Briansó-Llort, L.; García-Delpech, S.; Simó-Servat, O.; Simó, R. Usefulness of Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers from Aqueous Humor in Predicting Anti-VEGF Response in Diabetic Macular Edema: Results of a Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.R.; Ribeiro, L.; Bandello, F.; Lattanzio, R.; Egan, C.; Frydkjaer-Olsen, U.; García-Arumí, J.; Gibson, J.; Grauslund, J.; Harding, S.P.; et al. Functional and structural findings of neurodegeneration in early stages of diabetic retinopathy: Cross-sectional analyses of baseline data of the EUROCONDOR project. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2503–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Hernández, C.; Porta, M.; Bandello, F.; Grauslund, J.; Harding, S.P.; Aldington, S.J.; Egan, C.; Frydkjaer-Olsen, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; et al. Effects of Topically Administered Neuroprotective Drugs in Early Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy: Results of the EUROCONDOR Clinical Trial. Diabetes 2019, 68, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Channa, R.; Wolf, R.M.; Simo, R.; Brigell, M.; Fort, P.; Curcio, C.; Lynch, S.; Verbraak, F.; Abramoff, M.D.; Brigell, M.; et al. Diabetic Retinal Neurodegeneration and Macular Edema working group of the Mary Tyler Moore Vision Initiative’s Diabetic Retinal Disease Staging Update Project. A New Approach to Staging Diabetic Eye Disease: Staging of Diabetic Retinal Neurodegeneration and Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 4, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Hysi, P.G.; Khawaja, A.P.; Mahroo, O.A.; Xu, Z.; Hammond, C.J.; Foster, P.J.; Welikala, R.A.; Barman, S.A.; Whincup, P.H.; et al. UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. GWAS on retinal vasculometry phenotypes. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, V.E.; Wu, Y.; Bonelli, R.; Owen, J.P.; Scott, L.W.; Farashi, S.; Kihara, Y.; Gantner, M.L.; Egan, C.; Williams, K.M.; et al. Multi-omic spatial effects on high-resolution AI-derived retinal thickness. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroel, M.; Ciudin, A.; Hernández, C.; Simó, R. Neurodegeneration: An early event of diabetic retinopathy. World J. Diabetes 2010, 1, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, E.A.; Cheng, R.; Matsuzaki, S.; Zhou, K.; Ding, L.; Ahn, B.; Kinter, M.; Humphries, K.M.; Quiambao, A.B.; A Farjo, R.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of PPARα in retinopathy of type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubben, T.J.; Besirli, C.G.; Johnson, M.W.; Zacks, D.N. Retinal Neuroprotection: Overcoming the Translational Roadblocks. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 192, xv–xxii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yasvoina, M.; Olvera-Barrios, A.; Mendes, J.; Zhu, M.; Egan, C.; Tufail, A.; Fruttiger, M. Deciphering the Connection Between Microvascular Damage and Neurodegeneration in Early Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes 2024, 73, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; Aiello, L.P.; Abràmoff, M.D.; Antonetti, D.A.; Dutta, S.; Pragnell, M.; Levine, S.R.; Gardner, T.W. Updating the Staging System for Diabetic Retinal Disease. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M.M. Retinal Neurodegeneration in Diabetes: An Emerging Concept in Diabetic Retinopathy. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2021, 21, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Odenbach, S. Effect of long-term administration of alpha-lipoic acid on retinal capillary cell death and the development of retinopathy in diabetic rats. Diabetes 2004, 53, 3233–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Bierhaus, A.; Bugert, P.; Dietrich, N.; Feng, Y.; Vom Hagen, F.; Nawroth, P.; Brownlee, M.; Hammes, H.-P. Effect of R-(+)-alpha-lipoic acid on experimental diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovets, A.M.; Fursova, A.Z.; Kolosova, N.G. Therapeutic action of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SkQ1 on retinopathy in OXYS rats linked with improvement of VEGF and PEDF gene expression. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Walton, D.A.; Plafker, K.S.; Boulton, M.E.; Plafker, S.M. Sulforaphane recovers cone function in an Nrf2-dependent manner in middle-aged mice undergoing RPE oxidative stress. Mol. Vis. 2022, 28, 378–393. [Google Scholar]

- Grauslund, J.; Frydkjaer-Olsen, U.; Peto, T.; Fernández-Carneado, J.; Ponsati, B.; Hernández, C. EUROCONDOR. Topical Treatment With Brimonidine and Somatostatin Causes Retinal Vascular Dilation in Patients with Early Diabetic Retinopathy From the EUROCONDOR. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2257–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, V.; Centofanti, M.; Ziccardi, L.; Tanga, L.; Michelessi, M.; Roberti, G. Treatment with citicoline eye drops enhances retinal function and neural conduction along the visual pathways in open angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, V.; Oddone, F.; Ziccardi, L.; Roberti, G.; Coppola, G.; Manni, G. Citicoline and Retinal Ganglion Cells: Effects on Morphology and Function. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, P.; Sampedro, J.; Solà-Adell, C.; Simó-Servat, O.; Russo, C.; Varela-Sende, L.; Simó, R.; Hernández, C. Effects of Liposomal Formulation of Citicoline in Experimental Diabetes-Induced Retinal Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, J.; Zhou, S.; Padillo, E.; Clarke, K.G.; Gil, D.W. Effect of memantine on neuroretinal function and retinal vascular changes of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5152–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.; Bogdanov, P.; Gómez-Guerrero, C.; Sampedro, J.; Solà-Adell, C.; Espejo, C.; García-Ramírez, M.; Prieto, I.; Egido, J.; Simó, R. SOCS1-Derived Peptide Administered by Eye Drops Prevents Retinal Neuroinflammation and Vascular Leakage in Experimental Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.; Sobotka, M.; Caramoy, A.; Stempfl, T.; Moehle, C.; Langmann, T. Minocycline counter-regulates pro-inflammatory microglia responses in the retina and protects from degeneration. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterniti, I.; Di Paola, R.; Campolo, M.; Siracusa, R.; Cordaro, M.; Bruschetta, G.; Tremolada, G.; Maestroni, A.; Bandello, F.; Esposito, E.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide treatment reduces retinal inflammation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 769, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T. Role of P2X7 receptors in the development of diabetic retinopathy. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wu, S.; Jin, J.; Li, W.; Wang, N. Calcium dobesilate for diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2015, 58, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanov, P.; Simó-Servat, O.; Sampedro, J.; Solà-Adell, C.; Garcia-Ramírez, M.; Ramos, H.; Guerrero, M.; Suñé-Negre, J.M.; Ticó, J.R.; Montoro, B.; et al. Topical Administration of Bosentan Prevents Retinal Neurodegeneration in Experimental Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizu, Y.; Katayama, H.; Takahama, S.; Hu, J.; Nakagawa, H.; Oyanagi, K. Topical instillation of ciliary neurotrophic factor inhibits retinal degeneration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neuroreport 2003, 14, 2067–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Leo, L.F.; McGregor, C.; Grivitishvili, A.; Barnstable, C.J.; Tombran-Tink, J. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) peptide eye drops reduce inflammation, cell death and vascular leakage in diabetic retinopathy in Ins2(Akita) mice. Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, G.; Maestroni, S.; Leocani, L.; Mosca, A.; Godi, M.; Paleari, R.; Belvedere, A.; Gabellini, D.; Tirassa, P.; Castoldi, V.; et al. Topical nerve growth factor prevents neurodegenerative and vascular stages of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1015522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, G.; Sinha, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.-Y.; Tian, H.; Gao, F.; Li, W.; et al. Erythropoietin exerts a neuroprotective function against glutamate neurotoxicity in experimental diabetic retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 8208–8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, J.; Bogdanov, P.; Ramos, H.; Solà-Adell, C.; Turch, M.; Valeri, M.; Simó-Servat, O.; Lagunas, C.; Simó, R.; Hernández, C. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Action of Topical Administration of GLP-1 in an Experimental Model of Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, W. Exendin-4 protects retinal cells from early diabetes in Goto-Kakizaki rats by increasing the Bcl-2/Bax and Bcl-xL/Bax ratios and reducing reactive gliosis. Mol. Vis. 2014, 20, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, H.; Bogdanov, P.; Sabater, D.; Huerta, J.; Valeri, M.; Hernández, C.; Simó, R. Neuromodulation Induced by Sitagliptin: A New Strategy for Treating Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.; Bogdanov, P.; Simó, R.; Deàs-Just, A.; Hernández, C. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals That Retinal Neuromodulation Is a Relevant Mechanism in the Neuroprotective Effect of Sitagliptin in an Experimental Model of Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.; Augustine, J.; Karan, B.M.; Hernández, C.; Stitt, A.W.; Curtis, T.M.; Simó, R. Sitagliptin eye drops prevent the impairment of retinal neurovascular unit in the new Trpv2+/− rat model. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Balajam, N.Z.; Rakhsham, S.; Sajjadi-Jazi, S.M.; Shafiee, G.; Heshmat, R. GLP-1 receptor agonists efficacy in managing comorbidities associated with diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Lin, P.; Xing, Y.; Yang, N. Recent advances in the treatment and delivery system of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1347864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.; Pande, S.; Sagathia, V.; Ranch, K.; Beladiya, J.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Jacob, S.; Al-Tabakha, M.M.; Hassan, N.; Shahwan, M. Nanocarriers for the Delivery of Neuroprotective Agents in the Treatment of Ocular Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, A.; Hu, V.H. Safety around medicines for eye care. Community Eye Health 2021, 34, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, A.; Bruckner, T.; Haefeli, W.E.; Seidling, H.M. Improving eye-drop administration skills of patients—A multicenter parallel-group cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, R.; Dal Monte, M.; Lulli, M.; Raffa, V.; Casini, G. Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of Neuroprotective Substances for the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, D.; Guerrero, M.; Marican, A.; Arango, D.; Sarmento, B.; Ferrer, R.; Durán-Lara, E.F.; Clark, S.J.; Schwartz, S. Delivery Systems in Ocular Retinopathies: The Promising Future of Intravitreal Hydrogels as Sustained-Release Scaffolds. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kąpa, M.; Koryciarz, I.; Kustosik, N.; Jurowski, P.; Pniakowska, Z. Future Directions in Diabetic Retinopathy Treatment: Stem Cell Therapy, Nanotechnology, and PPARα Modulation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.J.; Joglekar, M.V.; Hardikar, A.A.; Keech, A.C.; O’Neal, D.N.; Januszewski, A.S. Biomarkers in Diabetic Retinopathy. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2015, 12, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.; Simó, R. Neuroprotection in diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2012, 12, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micera, A.; Balzamino, B.O.; Di Zazzo, A.; Dinice, L.; Bonini, S.; Coassin, M. Biomarkers of Neurodegeneration and Precision Therapy in Retinal Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 601647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wu, C.; Yu, H.; Lin, Z.; Shi, C.; Zheng, G.; et al. Visual acuity is correlated with ischemia and neurodegeneration in patients with early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore-Dotson, J.M.; Beckman, J.J.; Mazade, R.E.; Hoon, M.; Bernstein, A.S.; Romero-Aleshire, M.J.; Brooks, H.L.; Eggers, E.D. Early Retinal Neuronal Dysfunction in Diabetic Mice: Reduced Light-Evoked Inhibition Increases Rod Pathway Signaling. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 1418–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawam, Y.; Kurihara, T.; Sasaki, M.; Ban, N.; Yuki, K.; Kubota, S.; Tsubota, K. Neural degeneration in the retina of the streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes model. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, L.; Arrigo, A.; Aragona, E.; Antropoli, A.; Berni, A.; Saladino, A.; Parodi, M.B.; Bandello, F. Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 937999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zheng, X.; Yang, M.M. New insights of potential biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy: Integrated multi-omic analyses. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1595207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.