Abstract

Addressing the growing threat of climate change requires urgent and sustainable solutions for managing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. This review investigates the latest advancements in technologies for capturing and converting CO2, with a focus on approaches that prioritize energy efficiency, environmental compatibility, and economic viability. Emerging strategies in CO2 capture are discussed, with attention to low-carbon-intensity materials and scalable designs. In parallel, innovative CO2 conversion pathways, such as thermocatalytic, electrocatalytic, and photochemical processes, are evaluated for their potential to transform CO2 into valuable chemicals and fuels. A growing body of research now focuses on integrating capture and conversion into unified systems, eliminating energy-intensive intermediate steps like compression and transportation. These integrated carbon capture and conversion/utilization (ICCC/ICCU) technologies have gained significant attention as promising strategies for sustainable carbon management. By bridging the gap between CO2 separation and reuse, these sustainable technologies are poised to play a transformative role in the transition to a low-carbon future.

1. Introduction

The atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased by over 50% since the Industrial Revolution, surpassing 420 ppm and threatening climate stability. Projections estimate CO2 levels could reach 570 ppm by 2100, potentially causing a 3.2 °C global temperature rise [1,2]. Most emissions stem from point sources like power plants, making effective carbon management strategies crucial [3,4].

Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) can help address climate issues by capturing CO2 from specific sources or directly from the atmosphere [5]. Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) methods, including chemical looping and catalytic conversion, are essential to reduce emissions [6,7].

The global CCUS goal is to achieve a carbon-negative future society by reducing CO2 emissions and producing sustainable fuels and chemicals through capturing CO2 and converting to high value-added compounds [8,9]. Converting CO2 through photochemical and electrochemical reduction reactions (CO2RR) shows potential in creating valuable products, leveraging sustainable as well as renewable energy sources [10,11]. Both technologies have shown the capability and potential for generating the fuels which are considered as being both clean and emission-free, and they present significant benefits and power in addressing global warming in addition to reducing anthropogenic CO2 emissions [12,13,14].

Researchers have developed various methods to study and evaluate the catalytic reduction of CO2 toward its industrial application [15]. System modeling plays a vital role in understanding and optimizing CO2 capture and conversion processes [16]. These models help researchers and engineers design and develop efficient systems for photo/catalytic CO2 capture and conversion [17]. Additionally, life cycle assessment (LCA) is an environmental assessment technique that evaluates the ecological effects of a process or product from the time raw materials are first extracted until the end of its useful life, when it is disposed of [18,19]. Catalytic CO2 reduction methods are under study for industrial applications, supported by system modeling and life cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate sustainability and ecological impacts, aiding in developing efficient CO2 capture and conversion technologies [20,21,22,23,24].

This review addresses this evolving landscape by providing a unified, system-level analysis of sustainable CO2 management. Unlike prior reviews that focus on isolated components (capture, catalysis, or conversion), this work integrates these domains to critically assess the transition from standalone processes to integrated systems. We adopt a cross-cutting life-cycle and techno-economic framework to compare the scalability, cost, and holistic sustainability of competing pathways, with a particular focus on the production of formic acid and methanol as key value-added products. By examining advances in multifunctional materials, reactor design, and renewable energy coupling, this review aims to provide a holistic roadmap for the development of scalable, commercially viable ICCU technologies capable of supporting a circular carbon economy.

2. Sustainable CO2 Capture and Conversion

The high levels of CO2 emissions lead to environmental issues which means applying sustainable management strategies is crucial for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), so that we can handle the challenges associated with emission control [25,26,27]. In approaches to CO2 capture and conversion processes, there exist potential benefits for saving energy by combining them effectively to skip the need for energy-intensive steps including regeneration and transportation involved in the traditional sequential pathway [28,29,30]. The integrated capturing and converting carbon (ICCC/ICCU) technology is considered efficient and sustainable for capturing and utilizing CO2. It shows efficiency in converting CO2 and helps reduce costs by eliminating the need for compressing and transporting CO2.

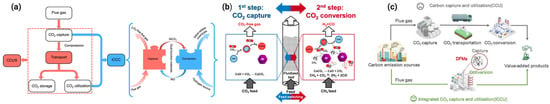

Traditional carbon capture and utilization (CCU) technologies, as shown in Figure 1a (left), involve multiple sequential steps, including CO2 capture, adsorbent regeneration, compression, transportation, and finally, conversion or storage. These multistep processes are not only energy-intensive but also cause significant material degradation, reducing overall process efficiency. To overcome these limitations, an integrated CO2 capture and utilization (ICCU) approach has been proposed, as depicted in Figure 1a (right) and further detailed in Figure 1c. In ICCU, CO2 is captured and directly converted into valuable products within a single reactor using dual-function materials (DFMs), eliminating the need for intermediate steps like compression and transport. A specific example of this is the calcium looping-based ICCU process shown in Figure 1b, where CaO captures CO2 to form CaCO3 in the first step. In the second step, under a methane (CH4) atmosphere, the CaCO3 is regenerated back to CaO while the released CO2 simultaneously undergoes dry reforming of methane (DRM) to produce synthesis gas (syngas: CO + H2). This integrated method greatly improves energy efficiency and system simplicity, offering a promising route for sustainable CO2 management.

Figure 1.

(a) Diagrammatic representations that contrast the development of (ICCC/ICCU) technologies with that of conventional CCUS technologies [31]. (b) A schematic illustration of the proposed method that incorporates dry reforming of methane (DRM) directly into the CO2 collection process, resulting in synthesis gas [32]. (c) Schematic diagrams of CCU and ICCU processes [33].

Carbon-containing compounds like methane (CH4) methanol (CH3OH) and formic acid (HCOOH) show potential for CCU. This new method enables the storage of energy while also capturing CO2 at the same time, a dual benefit making it different from traditional approaches. A key advantage of this technology is its ability to produce CH4 from gas by using a nickel-based catalyst known as the Sabatier reaction, in the process of CO (or CO2) hydrogenation [34].

Furthermore, the evaluation of CO2 value chains over their life cycle has traditionally relied on ad hoc criteria, such as the quantity of CO2 utilized and captured, and simplified CO2 balances. A comprehensive evaluation of the life cycle can serve as a basis for assessing the sustainability of CO2 value chains, considering environmental and economic factors. Utilizing optimization methods can be beneficial for evaluating the sustainability of CO2 value chains [31].

Sustainability Criteria and Strategic Role of Integrated CO2 Capture–Conversion Technologies

Sustainability in CO2 capture, conversion, and utilization requires a holistic framework that considers energy efficiency, material sustainability, resource intensity, environmental safety, and integration. Although renewable pathways may have higher current energy demands, they offer long-term sustainability through compatibility with low-carbon energy. Integrated capture and conversion strategies enhance sustainability by minimizing energy penalties and enabling decentralized processes. High-TRL systems are suited for centralized sectors, while emerging electrochemical pathways are better for flexible applications. Sustainable CO2 utilization focuses on resilience, scalability, and environmental compatibility rather than just immediate efficiency.

3. CO2 Capture

Carbon capture is a process involving the capture of CO2 emissions from sources like power plants and industrial sites, or even directly from the air itself, utilizing specialized technology-induced methods such as pre-combustion capture (capturing CO2 before fuel burning) post-combustion capture (capturing CO2 after fuel burning), oxy-fuel combustion (burning fuel, in pure oxygen rather than air), and direct air capture (extracting CO2 directly from the atmosphere) [35,36,37].

Different technologies are used for capturing CO2, such as direct air capture (DAC), absorption (CO2 is absorbed by a solvent and then released for storage), adsorption (CO2 is captured by solid materials), and membrane separation (CO2 is separated from other gases using a semi-permeable membrane) [38,39]. Once captured, CO2 needs to be transported to storage sites, usually through pipelines or, in some cases, by truck or ship [40].

While conventional CO2 capture technologies such as amine scrubbing, solid sorbents, and membrane separation remain the foundation for industrial-scale carbon management, the integration of capture and conversion (ICCC/ICCU) represents the most innovative and rapidly developing direction. Integrated systems avoid the energetic penalties associated with CO2 release, purification, and compression, enabling direct utilization of captured CO2 under mild conditions. This approach provides significant advantages in energy efficiency, system compactness, and overall process economics. Therefore, the following section expands on ICCC/ICCU concepts in greater detail, reflecting their growing importance and disruptive potential in next-generation carbon utilization technologies.

Molecular Design and Structure–Property Relationships in CO2 Capture Materials

The molecular and structural characteristics of CO2 capture materials directly dictate their performance and stability. In amine-based solvents, the specific chemistry between the amine group and CO2, influenced by factors like steric hindrance (e.g., in AMP), determines whether carbamate or bicarbonate forms, which in turn governs the energy-intensive regeneration step. For solid sorbents like Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs), their exceptional surface area and tunable pores are ideal for physisorption [41], but their practical application is often limited by poor hydrolytic stability [42], a challenge that can be addressed through molecular design such as incorporating hydrophobic linkers. Conversely, high-temperature chemisorbents like CaO suffer from sintering—the loss of surface area and pore structure due to particle agglomeration. This macroscopic failure is mitigated at the atomic scale by doping with inert materials like Al2O3 or MgO, which create a thermally stable nanostructure to preserve the sorbent’s morphology and capacity over repeated capture–regeneration cycles [33]. Thus, optimizing CO2 capture relies on understanding and engineering these fundamental structure–property relationships at the molecular level.

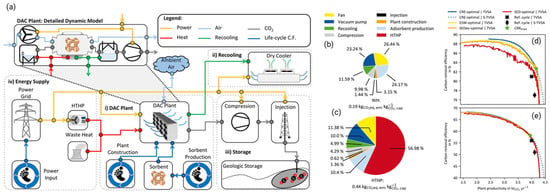

As shown in schematic at Figure 2a, Postweiler et al. [43] explored the optimization of adsorption-based Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS) systems, emphasizing the need for systemic climate-benefit metrics like Carbon Removal Efficiency (CRE) and Carbon Removal Rate (CRR) over traditional energy-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) such as specific energy demand (SED) and equivalent shaft work (ESW). Figures illustrate that using CRE as a KPI can enhance both carbon removal efficiency and plant productivity, with notable shifts in Pareto frontiers toward higher values (Figure 2d,e). The study employs a dynamic DACCS model that incorporates life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions, enabling comprehensive process analysis (Figure 2b,c). It highlights the importance of cleaner energy sources, showing that lower GHG emissions from electricity significantly improve DACCS performance. The findings advocate flexible DACCS operations in response to varying electricity GHG emissions and recommend integrating CRE with economic assessments for broader applicability in negative emission technologies.

Figure 2.

(a) The model scheme of the DACCS system is shown, with power flows marked in yellow, heat flows in red, and waste heat flows in green. The life cycle GHG emissions are shown with blue lines. (b) WH case and (c) HTHP case. Trade-offs between plant productivity and carbon removal efficiency for different KPI-optimal processes: (d) WH case and (e) HTHP case [43].

This critical assessment underscores that while Direct Air Capture (DAC) shows promise, its path to climate-relevant scale is constrained by profound systemic challenges. Its immense energy demand would compete for scarce renewable electricity, and its net benefit depends on a fully decarbonized grid—creating a circular dependency. Coupled with massive material and infrastructure requirements, these hurdles position DAC not as a replacement for aggressive source emission reductions, but as a necessary, high-cost complement for addressing distributed and legacy emissions.

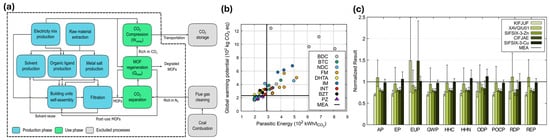

Hu et al. [44] evaluated the environmental impacts of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) for carbon capture after combustion as opposed to monoethanolamine (MEA) scrubbing technology using LCA and molecular simulations (Figure 3a). It highlights that solvent type and recycling rates are critical in determining the overall environmental impact, particularly affecting eutrophication potential (EUP). Figure 3b illustrates the relationship between parasitic energy, greenhouse gas emissions, and the performance of various MOFs, showing that some can achieve up to 33% lower energy consumption than MEA. As shown in Figure 3c, the study identifies five top-performing MOFs, including SIFSIX-3-Zn, which have lower environmental impacts than MEA, emphasizing the importance of optimizing synthesis conditions and using greener solvents.

Figure 3.

(a) The system boundary was chosen for the MOF-based CCS process’s LCA. Every block represents a distinct unit process. (b) The connection between parasitic energy and GWP. The horizontal and vertical lines, respectively, indicate the MEA-based CCS process’s GWP and parasitic energy. (c) The five best-performing MOFs were ranked by parasitic energy (normalized to MEA), with KIFJUF showing the lowest and SIFSIZ-3-Cu the highest, as illustrated with error bars indicating variability [44].

Table 1 provides an overview of the main technologies for CO2 capture, highlighting their relative maturity, efficiency, and scalability. Pre-combustion capture is generally recognized for its efficiency, while post-combustion capture allows for retrofitting and modifications to existing systems. Oxy-fuel combustion enables the production of CO2-rich flue gas, facilitating easier separation, while direct air capture (DAC) is particularly notable for its potential to deliver negative emissions, despite its very high energy and cost requirements. Across all of these approaches, the major challenges remain the high initial capital costs, significant energy demand, and in some cases the costly production of oxygen, all of which may limit their broad deployment.

Table 1.

Comparative Insights into CO2 Capture Technologies.

Amine-based absorption is currently the most mature and widely deployed option, with capture efficiencies of 85–95% and proven commercial readiness. However, its widespread use is hindered by the substantial energy penalty associated with solvent regeneration as well as issues such as solvent degradation and corrosion. Calcium looping represents another near-commercial pathway, offering comparable efficiency with relatively inexpensive sorbents, and is particularly well suited to high-temperature industries such as power generation and cement production. Emerging technologies, including solid sorbents and membranes, are attractive due to their lower energy requirements, modularity, and compact design, but remain challenged by moisture sensitivity, selectivity limitations, and questions of scalability. Cryogenic separation, while capable of producing extremely pure CO2, is energy-intensive and therefore restricted to niche applications where concentrated CO2 streams are already available. DAC stands out for its ability to capture CO2 from diffuse sources, enabling long-term climate strategies that rely on negative emissions. However, its future deployment depends heavily on breakthroughs in process efficiency and the integration of renewable energy to reduce costs. Biological pathways, such as algae cultivation and biochar formation, offer co-benefits including biomass production and soil enrichment, while requiring comparatively less energy. Nevertheless, their scalability is constrained by land and water availability as well as generally low CO2 uptake rates.

Despite high energy costs, Table 1 shows that mature CO2 capture technologies, such as calcium looping and amine absorption, are expected to lead to large-scale adoption because of their high readiness and efficiency. Solid sorbents, membranes, and direct air capture (DAC) are examples of emerging technologies that enable modular designs but have issues with energy cost and demand, suggesting a trade-off between their maturity and flexibility. There is no single technology that works best for everyone; instead, complementarity is what makes them useful. Amine absorption and calcium looping will predominate in the near future, but if costs come down in the medium to long term, additional technologies could become more popular. Furthermore, biological capture can offer synergies in larger sustainable systems despite its restricted use.

A critical synthesis of the CO2 capture and formic acid conversion literature reveals significant trade-offs in efficiency, scalability, and readiness. In capture, amine scrubbing remains the most mature (TRL 8–9) with high efficiency (85–95%) but suffers from high energy penalties and solvent degradation, whereas emerging solid sorbents and membranes offer modularity and lower energy use but face stability and selectivity challenges under realistic conditions [45]. Direct air capture enables negative emissions but is energy-intensive and costly without renewable integration [43]. For formic acid production, electrochemical reduction using Bi-based catalysts achieves >90% Faradaic efficiency but struggles with long-term stability and electrolyte management [46]. Photocatalytic systems offer modular operation but lower production rates and light-distribution limits, while thermocatalytic hydrogenation shows higher TRL and continuous operation but depends on green H2 and faces separation hurdles [47]. Ultimately, integrated capture–conversion systems such as calcium looping-DRM or amine–electrolysis hybrids present promising routes to bypass energy-intensive intermediate steps, yet they remain at lower TRL and require further validation under industrial conditions.

4. CO2 Conversion

The process of CO2 conversion involves transforming CO2 into useful products or fuels, aiming to reduce its environmental impact while simultaneously generating economic value. This approach is closely connected to Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU), which focuses not only on capturing CO2 from industrial emissions or the atmosphere but also on converting it into marketable chemicals, fuels, or materials. Unlike simple carbon storage, CCU emphasizes the reuse of CO2, thus contributing to a circular carbon economy [48]. Overall, CO2 conversion technologies particularly into formic acid and methanol represent significant advances in CCU. They not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also transform CO2 into valuable resources, creating a bridge between environmental sustainability and economic viability. Various methods are employed for CO2 conversion, including chemical, biological, and electrochemical approaches [49].

4.1. CO2 Conversion into Formic Acid

Converting CO2 into formic acid represents an important chemical reaction, which turns CO2 into a valuable carboxylic acid. Formic acid is widely used in industry for different purposes, such as a preservative, antibacterial agent, coagulant, and as a starting material in chemical production [50]. This conversion typically involves metal catalysts like ruthenium, palladium, or copper to facilitate the reduction of CO2 to formic acid [51]. It is part of ongoing research efforts for CCU to mitigate CO2 emissions and offers promise for both environmental and economic reasons [52,53,54].

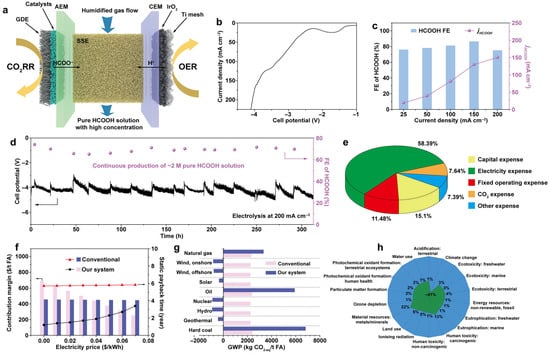

Zhang and his colleagues [46] developed a novel approach for catalytically reducing CO2 to formic acid leveraging bismuth-based catalysts with lattice distortion defects, known as Bi-based catalysts with rich lattice distortion defects (RD-Bi). This was accomplished utilizing laser-irradiation in liquid-phase (LIL) to generate amorphous BiOx nanoparticles, which were subsequently electrochemically reduced to RD-Bi. The method resulted in a high yield of 2 M formic acid at an industrial current density of 200 mA cm−2 over 300 h with Faradaic efficiency of 94.2% for formate (Figure 4b–d). Further techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment suggest that this technique could potentially replace the traditional hydrolysis of methyl formate in commercial formic acid production. Additionally, the formic acid produced can serve as a direct fuel in air-breathing formic acid fuel cells, achieving a power density of 55 mW cm−2 and remarkable thermal efficiency of 20.1% (Figure 4e–h). These results underscore the promise of electrochemical CO2 reduction as a sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly method for producing formic acid.

Figure 4.

(a) Diagrammatic illustration of the ECO2RR in MEA with SSE generating a high concentration of pure HCOOH solution. (b,c) LSV curve (b) FE of HCOOH at different cell current densities, and associated partial current densities of HCOOH (c). (d) Long-term stability test and FEs for CO2 reduction to FA solution at 200 mA cm−2 over RD-Bi catalyst in MEA with SSE. (e) Used the ECO2RR method to divide the cost of generating 1 t FA. (f) ECO2RR offers higher contribution margins and shorter payback times than conventional methyl formate hydrolysis across varying power prices. (g) The potential for global warming of ECO2RR and conventional formate hydrolysis methods is also discussed. (h) ECO2RR outperforms conventional methyl formate hydrolysis by delivering greater profitability and faster cost recovery under different electricity prices [46].

The electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formic acid presents challenges for industrial-scale deployment, including scalability of reactor designs, uniform current distribution, mass transfer at high densities, electrolyte stability, and catalyst durability amidst flue gas impurities. Additionally, improving energy efficiency through reduced overpotentials and integration with low-carbon electricity sources is crucial for environmental and economic viability [55].

Additional practical hurdles involve the downstream separation and purification of formic acid from the electrolyte and gaseous co-products, which can significantly impact overall process energy and cost. The integration of electrochemical conversion with upstream CO2 capture—central to the concept of integrated carbon capture and conversion (ICCC)—also demands careful alignment of operating conditions and material compatibility to avoid efficiency losses [56]. Addressing these challenges through advances in catalyst design, reactor engineering, and process intensification will be essential for translating laboratory achievements into commercially viable, sustainable formic acid production systems [57].

Industrial methyl-formate hydrolysis typically requires 5.6–7.3 GJ per ton of formic acid and results in production costs of 450–650 USD per ton. In contrast, the RD-Bi electrochemical CO2-to-formic acid system operates at 3.2–3.8 V, equivalent to an energy demand of 8–11 MWh per ton of formic acid, and shows competitive economic performance under renewable-electricity scenarios. These quantitative comparisons highlight the potential economic advantages of RD-Bi technology relative to conventional processes.

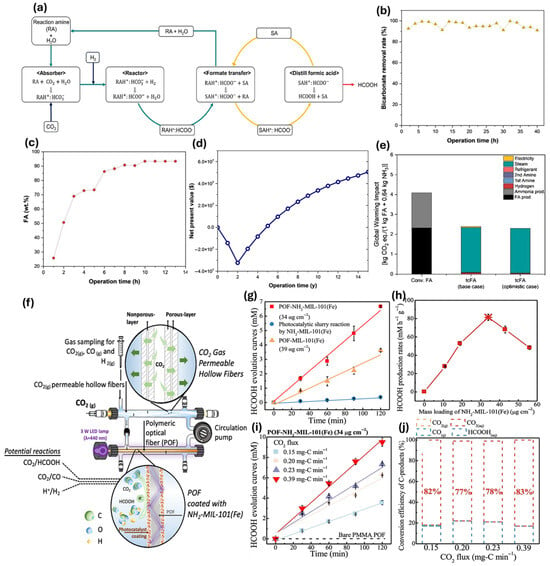

A new cost-effective and efficient method for producing formic acid from CO2 has been developed by Kim et al. [47], which has potential environmental benefits, and could help achieve a net-zero economy in the face of the climate crisis. This study presents an innovative CO2 hydrogenation process for producing formic acid (Figure 5a) at a pilot scale of 10 kg/day, achieving 92 wt% purity. The process demonstrates a 37% cost reduction and a 42% decrease in global warming impact compared to conventional methods, validated by continuous operation for over 100 h with an 82% CO2 conversion rate (Figure 5a,b). Key strategies include optimal amine selection and corrosion mitigation, enhancing operational efficiency. Techno-economic analysis indicates a net present value of $5.1 million over 15 years (Figure 5d), while life cycle assessment reveals a 41.5% reduction in global warming potential (Figure 5e), showcasing significant environmental benefits.

Figure 5.

(a) Illustration of the formic acid (FA) production process through CO2 hydrogenation, with colored streamlines indicating reaction and separation amines (cyan), input materials (yellow), and FA output (red), and bicarbonate flow (navy). key performance indicators (KPIs) (b) for bicarbonate removal and (c) the amount of FA recovered through distillation. (d) Net present value analysis indicating the process’s economic viability. (e) Global warming impact indices [47]. (f) Dual-fiber reactor with NH2-MIL-101(Fe)-coated optical fibers and hollow fibers enables photocatalytic CO2 reduction to formic acid. (g) Comparison of HCOOH yields under 440 nm LED using NH2-MIL-101(Fe)-coated POFs, MIL-101(Fe), and NH2-MIL-101(Fe) slurry. (h) Optimal catalyst surface loading determined at 34 μg cm−2 NH2-MIL-101(Fe). (i) CO2 flux results and (j) carbon mass balance after 2 h of photocatalytic CO2 reduction shows efficiency trends with optimized catalyst loading under different CO2 pressures [58].

As shown in Figure 5f, Wang et al. [58] presented a novel dual-fiber reactor system for efficient CO2 conversion to formic acid (HCOOH) using polymeric optical fibers (POFs) coated with NH2-MIL-101(Fe) and hollow-fiber membranes (HFMs) for bubble-free CO2 delivery. This system achieved a remarkable production rate of 116 ± 1.2 mM h−1 g−1 (Figure 5h), with a quantum efficiency of 12% based on the HCOOH generation (Figure 5g), significantly outperforming traditional slurry-based methods. The dual-fiber design enhanced light utilization and CO2 adsorption, achieving 99% selectivity for HCOOH. Figure 5i shows that the peak production rate of formic acid (HCOOH) was 116 mM h−1 g−1 (k = 3.5 × 10−4 mM s−1), occurring at a CO2 pressure of 10 psig. This rate is over 2.7 times higher than the production rate observed at 2 psig (k = 1.9 × 10−4 mM s−1). Furthermore, the greatest carbon-conversion efficiency of CO2 to HCOOH was attained at 3 psig of CO2, recorded at 0.2 mg-C·min−1 (Figure 5j).

4.2. CO2 Conversion into Methanol

Converting CO2 to methanol is an attractive process to reduce emissions and produce valuable chemical feedstock [59]. The process involves capturing CO2, producing hydrogen, combining CO2 and H2 to make methanol, purifying the methanol, and using it as fuel, solvent, or feedstock [60]. Challenges include the energy-intensive nature of capturing and purifying CO2, and the need for efficient catalysts [61,62,63]. Continuing research and development efforts are focused on optimizing the efficiency and economic viability of converting CO2 into methanol as a strategy to mitigate climate change [64].

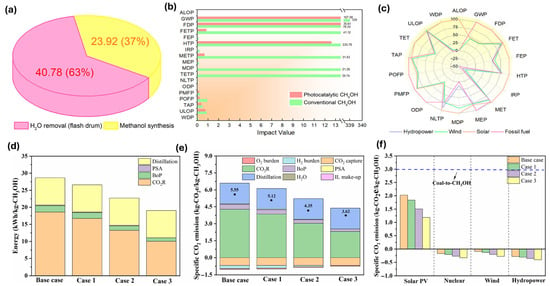

Sheng Ling et al. [65] assessed a photocatalytic CO2 reduction system utilizing graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) for methanol production. They demonstrated a 68% decrease in carbon footprint and a 53% reduction in fossil fuel consumption compared to conventional steam methane reforming. Key results highlight lower energy requirements (Figure 6a) and notable environmental advantages (Figure 6b). Sensitivity analysis suggests that incorporating renewable energy, particularly hydropower, can further lessen environmental impacts (Figure 6c). This study underscores the promising role of photocatalytic technology in enabling sustainable, industrial-scale methanol production.

Figure 6.

(a) Detailed energy usage in kWh for the CH3OH synthesis step using the traditional equipment. (b) Overview of the 18 midpoint indicator analysis. (c) Sensitivity analysis of replacing fossil fuels with renewables. The impact ratings are adjusted to the greatest value of each indicator as a percentage (%) [65]. (d) Energy and (e) specific CO2 emissions for CO2R under different scenarios. (f) Specific CO2 emissions for CO2R under different scenarios with 100% utilization of solar photovoltaic (PV) [66].

Li and colleagues [66] evaluated the economic and environmental feasibility of methanol production via electrochemical reduction of CO2 from bio syngas. They highlight that investment and electricity costs are significant contributors to total production costs (TPC), with integrated systems reducing TPC by 28–66% (Figure 6d,e). Current stand-alone systems are economically unviable, but future advancements could lower costs to 0.50 €/kg-CH3OH. Renewable energy sources can enhance sustainability, achieving negative specific CO2 emissions (Figure 6f). The study emphasizes the importance of integrating CO2R with biomass gasification to improve economic competitiveness and environmental benefits.

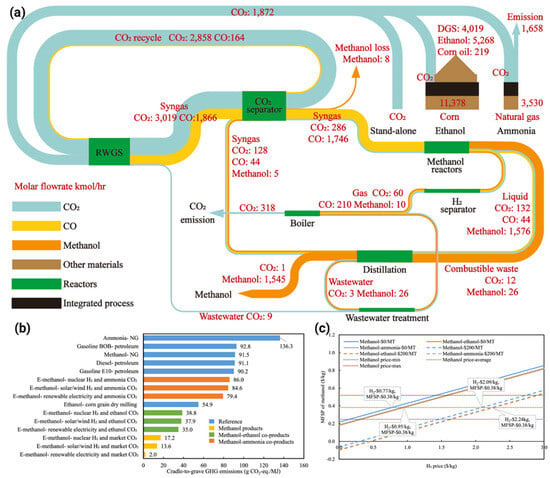

Zang et al. [67] analyzed the technoeconomic and life cycle aspects of synthetic methanol production using renewable H2 and high-purity CO2 from ethanol and ammonia plants. It identifies three production systems: integrated methanol–ethanol, integrated methanol-ammonia, and standalone methanol coproduction. The stand-alone system achieves cradle-to-grave emissions of 13.6 g CO2-equiv/MJ, significantly lower than conventional methanol at 91.5 g CO2-equiv/MJ (Figure 7b). Carbon credit can further reduce costs (Figure 7c). The study highlights that integrating methanol synthesis with other processes improves efficiency, with a carbon conversion efficiency of 82.5% and energy efficiency of 75.6% (Figure 7a). The findings suggest broader applications across various industries to enhance environmental benefits.

Figure 7.

The study examines the CO2 conversion and specific electricity consumption of: (a) Sankey diagram illustrates carbon flow balances (kmol/h) across components, processes, and material streams in three systems. (b) CTGR analysis compares synthetic methanol’s GHG emissions with other fuels using renewable H2 sources and U.S. grid-based methanol synthesis. (c) Breakeven H2 costs for various CO2 credit values and methanol production systems are also presented [67].

The electrochemical route for CO2 conversion to formic acid is inherently more suitable for decentralized and modular applications, whereas the hydrogenation pathway is better aligned with centralized, large-scale production. This distinction arises from fundamental differences in energy input, system complexity, and infrastructure requirements. Electrochemical CO2 reduction operates under relatively mild temperatures and pressures and can be directly powered by renewable electricity. In contrast, hydrogenation requires a continuous hydrogen supply and large-scale setups, favoring centralized operations with economies of scale but limiting decentralized use. The trade-off is between scalability and flexibility, with electrochemical systems offering operational advantages but facing challenges like electricity cost and catalyst durability, while hydrogenation is more mature but dependent on centralized infrastructure. Both pathways should be seen as complementary, serving different segments of CO2 utilization.

In Table 2, the summary presents CO2 conversion routes, focusing on their scalability and readiness for producing bulk fuels and intermediates. Routes that generate urea, syngas, and methanol show higher scalability and TRLs, making them suitable for centralized industrial use, with efficiencies of 50–70%. However, they require significant renewable hydrogen and effective CO2 integration. In contrast, electrochemical processes that produce carbon monoxide and formic acid are less mature, indicated by lower TRLs, but allow for decentralized operations and better alignment with renewable energy. The choice of product impacts conversion strategy and reactor design, with various CO2 conversion technologies having different maturities and efficiencies for fuels, chemicals, and building materials.

Table 2.

Comparative Summary of Major CO2 Conversion Pathways.

Formic acid, produced via electrochemical reduction, represents a promising liquid energy carrier and chemical intermediate. While its Faradaic efficiencies are high at lab scale (40–60%), broader deployment is currently restricted by catalyst stability and high energy costs. Carbon monoxide serves as a key feedstock for downstream chemical synthesis, yet challenges in selectivity and catalyst durability limit its widespread use. Industrial-scale urea production is already commercialized (TRL 8–9) and achieves high efficiency (60–70%), but its environmental benefits depend on replacing conventional ammonia with green hydrogen. Polymers and carbonates, synthesized via chemical fixation, offer high conversion efficiency (60–90%), though their applicability is constrained by smaller markets and catalyst costs. Mineralization, which converts CO2 into stable Ca/Mg carbonates for construction, combines high efficiency (70–90%) with very high scalability (TRL 7–9), providing a permanent and environmentally beneficial route, despite slow reaction kinetics and the energy required for mineral processing.

Overall, methanol and mineralization pathways appear most promising for large-scale deployment, whereas formic acid, syngas, and polymers serve as niche or transitional solutions. The success of all CO2 conversion routes depends critically on integration with renewable energy sources and efficient coupling with capture technologies, emphasizing the need for system-level optimization in sustainable carbon management strategies.

4.3. Molecular Mechanisms and Active Sites in Catalytic CO2 Conversion

Advancing CO2 conversion technologies requires a molecular-level understanding of the catalytic cycles involved. In thermocatalytic methanol synthesis, Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts typically follow a formate pathway, where CO2 is sequentially hydrogenated via adsorbed formate and methoxy intermediates. Catalytic activity is closely tied to the Cu–ZnO interface and the oxidation state of Zn, with the hydrogenation of formate often being rate-limiting [68]. In electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (CO2RR), product selectivity hinges on the catalyst’s electronic structure and interactions with intermediates. On Cu surfaces, *CO dimerization dictates multi-carbon product formation, influenced by local pH, electric field, and crystal facet. For formate-selective metals like Sn or Bi, stabilization of the *OCHO intermediate is critical, though catalyst degradation under operating conditions remains a challenge [69].

In photocatalytic systems, efficiency depends on the cascade from photon absorption to surface redox reactions, with charge recombination being a major bottleneck. Modifications such as nitrogen vacancies in g-C3N4 or heterojunction formation can enhance charge separation, while coordinatively unsaturated metal sites in MOF-based photocatalysts activate CO2 by stabilizing key reduction intermediates like *COOH.

5. Integrated Carbon Capture and Conversion/Utilization (ICCC/ICCU)

Integrated Carbon Capture and Conversion/Utilization (ICCC/ICCU) refers to a class of technologies that combine the capture of CO2 emissions with their immediate conversion or utilization into valuable products within a single, often synergistic system. ICCC/ICCU technologies aim to enhance the economic efficiency of CO2 conversion by addressing energy-intensive processes, such as purification and compression [70].

Molecular Synergies in Dual-Function Materials (DFMs) for ICCU

Integrated carbon capture and conversion utilizes Dual-Function Materials (DFMs), which simultaneously capture CO2 and catalyze its conversion. For instance, in CaO–Ni DFMs, CaO captures CO2 as CaCO3, which then decomposes in a CH4 atmosphere to release CO2 at Ni nanoparticle sites, enhancing syngas yield and reducing equilibrium limitations. Strong metal–support interactions at the Ni–CaO interface increase catalyst activity and coking resistance, while CeO2 aids in stabilizing Ni and promoting carbon removal. Similarly, in amine-supported systems with metals like Pd and Ru, CO2 converts to carbamate/bicarbonate and spills over to catalytic sites for reduction. Challenges include the kinetics of spillover and amine stability under reducing conditions, with DFT and in situ spectroscopy assisting in understanding interfacial processes and designing efficient DFMs [32,71,72].

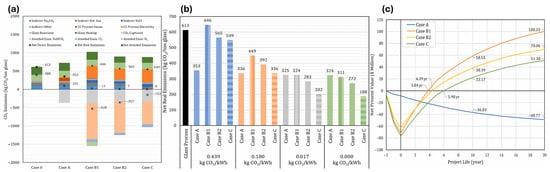

Caudle et al. [73] investigated the ICCU in the glass industry to reduce CO2 emissions, emphasizing the economic and environmental benefits of CO2 mineralization. It models three cases (B1, B2, C) against a conventional CCS case (A). Case A, utilizing amine absorption, captures 380 kg CO2/ton of glass but lacks profitability without carbon credits. In contrast, Case B1 captures the same amount while producing 127 kton/year of NaHCO3 and additional byproducts, achieving net negative emissions of −528 kg CO2/ton glass. Case B2 partially replaces natural gas with H2, reducing emissions to 338 kg CO2/ton, while Case C incorporates Na2CO3 recycling, capturing 100% of CO2 but requiring higher capital investment. The analysis highlights that all CCU cases demonstrate significant emissions reduction and profitability, illustrating emissions comparisons (Figure 8a), net real (Figure 8b), and net present values (Figure 8c), respectively, underscoring the potential for strategic application in hard-to-abate industries.

Figure 8.

(a) A summary of positive and negative emissions from the glass process and four potential carbon capture technologies. The paper highlights that instances 0 and A have no averted emissions. (b) Shows how four carbon capture methods are related by analyzing their net CO2 emissions and how sensitive they are to electrical CO2 emission parameters. (c) Net present values for the four carbon capture technologies during a 20-year project life cycle [73].

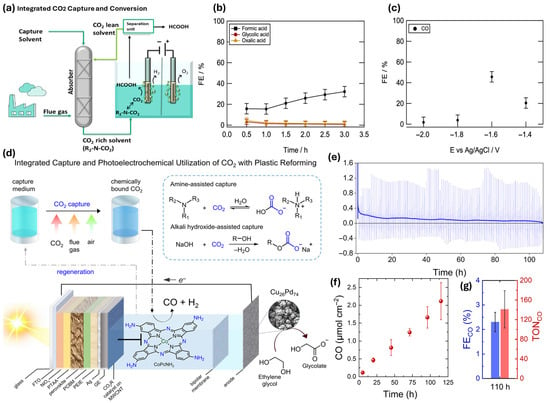

Pérez-Gallent et al. [74] present an integrated approach for CO2 capture and electrochemical conversion using amine-based solvents as electrolytes (Figure 9a). This method eliminates the energy-intensive CO2 desorption step, enhancing economic feasibility and efficiency. At elevated temperatures (75 °C), formate production rates increase significantly, achieving faradaic efficiencies of about 40% (Figure 9b). The use of a mixture of 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP) and propylene carbonate (PC) improves efficiency, with 1 M AMP concentration optimizing faradaic efficiency despite potential mass transfer limitations. Validated in a semi-continuous flow reactor, the system shows promise for large-scale applications, with gold electrodes yielding up to 45% faradaic efficiency for carbon monoxide production (Figure 9c). This integrated methodology supports the advancement of a circular carbon economy.

Figure 9.

Illustration of integrated CO2 capture and conversion strategies, including: (a) CO2 absorption in amine solution (carbamate/bicarbonate forms). (b,c) Faradaic efficiencies for formate, glycolic acid, oxalate (Pb electrode) and CO (Au electrode) under varying electrolysis conditions [74]. (d) Using solar energy, the one-step PEC process upcycles ethylene glycol from plastic to glycolic acid and turns post-capture solution into syngas. (e–g) PEC performance over 110 h: (e) photocurrent stability, (f) linear CO production, and (g) turnover number (TON) with Faradaic efficiency, demonstrating long-term system stability under simulated solar irradiation [75].

Kar et al. [75] discuss an innovative system for capturing and converting CO2 from various sources in their article, including concentrated streams, flue gas, and ambient air, into syngas using solar energy (Figure 9d). The process employs amine or hydroxide solutions for efficient CO2 capture, facilitated by a cobalt-phthalocyanine catalyst. This integrated approach allows for direct conversion of captured CO2 into syngas, thus addressing both carbon utilization and waste valorization. Figure 9e shows the photocurrent transients over a 110 h experiment, which exhibit fluctuations due to charge recombination. In contrast, Figure 9f illustrates a linear increase in CO production, demonstrating the system’s consistent performance. The experiment achieved a faradaic efficiency of 2.3% and a turnover number (TON) of 141 for CO production, highlighting the effectiveness of converting atmospheric CO2 into usable products, as shown in Figure 9g.

Table 3 provides an overview of current integrated carbon capture and conversion/utilization (ICCC/ICCU) strategies, comparing different approaches in terms of capture–conversion integration, energy requirements, efficiency, technology readiness, and practical advantages. Among the methods, chemical looping CO2 capture and in situ conversion and mineralization via integrated absorption stand out due to their high overall efficiency (60–90%), energy efficiency, and relatively advanced maturity (TRL 6–7 for chemical looping, TRL 7–9 for mineralization). These systems offer compact designs, reduce intermediate energy costs, and enable either permanent or value-added CO2 utilization, making them highly promising for industrial-scale deployment. Other approaches, such as absorption-methanolization and membrane-coupled electrocatalysis, provide the advantage of directly producing fuels or chemicals, but they face challenges including high renewable hydrogen demand, catalyst stability, and scale-up limitations [71]. Photocatalysis- and ionic liquid-based adsorption systems offer modular and low-energy options suitable for solar-driven processes, yet they are still at early research stages (TRL 4–5) and require further development for commercial application. Overall, the choice of ICCC/ICCU method depends on the intended application: mineralization and chemical looping are preferable for permanent CO2 storage and large-scale industrial integration, while absorption-methanolization and membrane-electrocatalysis are more suitable for producing fuels or high-value chemicals when renewable energy and hydrogen are available. Emerging photocatalytic and high-value adsorption systems show potential for decentralized or off-grid applications. In summary, high TRL systems with integrated capture and conversion, such as chemical looping and mineralization, are currently the most feasible for near-term deployment, whereas other technologies are expected to become competitive as renewable energy integration and catalyst performance advance. Thus, chemical looping and mineralization represent the most practical and scalable ICCC/ICCU strategies for immediate industrial implementation [76].

Table 3.

Overview of Integrated Carbon Capture and Conversion/Utilization (ICCC/ICCU) Technologies.

6. Conclusions

ICCU technologies represent a shift towards more efficient carbon management by turning captured CO2 into useful products as compared with traditional CCU technologies. This approach aims to combat climate change by creating closed-loop systems. However, success relies on overcoming various challenges, including technical, regulatory, economic, and societal issues, which require collaboration among researchers, industries, and policymakers. Recent improvements in photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical technologies have focused on increasing efficiency and stability under real sunlight. It is important to design effective materials for these systems, particularly for applications like treating flue gas. This involves choosing engineering photocatalysts to improve their performance and durability against harsh conditions. Dual-function materials are noteworthy because they can capture and convert pollutants at the same time, enhancing performance and sustainability. Their design aims to resist damage from heat and chemicals. According to this review, integrating ICCU technologies with cutting-edge material design is essential for creating a sustainable, low-carbon economy to lower the cost of ICCU technologies. Additionally, achieving this economic model necessitates a combination of financial incentives, supportive regulations, and international collaboration.

Author Contributions

S.M.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft. Z.M.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization. A.M.S.: Data curation, Investigation. D.K.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. M.T.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00343746) and the “Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Ulsan RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ulsan Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-07-001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Swaminathan, S.; Singh, M.R. Advancements in Emulsion Technologies for Efficient and Sustainable CO2 Capture and Gas Absorption. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 11717–11732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Sipra, A.T.; Gao, N.; Vandenberghe, L.P.d.S.; Vieira, S.; Soccol, C.R.; Zhao, R.; Deng, S.; et al. A comprehensive review of carbon capture science and technologies. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Khurram, A.; Hatton, T.A.; Gallant, B. Electrochemical carbon capture processes for mitigation of CO2 emissions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8676–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prašnikar, A.; Linec, M.; Jurković, D.L.; Bajec, D.; Sarić, M.; Likozar, B. Understanding membrane-intensified catalytic CO2 reduction reactions to methanol by structure-based multisite micro-kinetic model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 463, 142480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, A. CO2 Capture via Electrochemical pH-Mediated Systems. ACS Energy Lett. 2025, 10, 1550–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffry, L.; Ong, M.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.; Mofijur, M.; Mubashir, M.; Show, P.L. Greenhouse gases utilization: A review. Fuel 2021, 301, 121017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A. Synthesis chemistry of metal-organic frameworks for CO2 capture and conversion for sustainable energy future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 570–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Loh, H.; Low, B.Q.L.; Zhu, H.; Low, J.; Heng, J.Z.X.; Tang, K.Y.; Li, Z.; Loh, X.J.; Ye, E.; et al. Role of oxygen vacancy in metal oxides for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 321, 122079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for CO2 conversion: A key technology for rapid introduction of renewable energy in the value chain of chemical industries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1711–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P.R.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Varjani, S.J.; Saravanan, A. A review on photochemical, biochemical and electrochemical transformation of CO2 into value-added products. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 33, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Ye, W.; Li, Y. CO2 Reduction: From the Electrochemical to Photochemical Approach. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, T.; Shafi, S.; Anwar, M.T.; Rizwan, K.; Ahmad, T.; Bilal, M. Revisiting photo and electro-catalytic modalities for sustainable conversion of CO2. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 623, 118248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Rahaman, M.; Bharti, J.; Reisner, E.; Robert, M.; Ozin, G.A.; Hu, Y.H. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, Z.; Tayebi, M.; Tayebi, M.; Masoumi Lari, S.A.; Sewwandi, N.; Seo, B.; Lim, C.-S.; Kim, H.-G.; Kyung, D. Electrocatalytic Reactions for Converting CO2 to Value-Added Products: Recent Progress and Emerging Trends. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somoza-Tornos, A.; Guerra, O.J.; Crow, A.M.; Smith, W.A.; Hodge, B.-M. Process modeling, techno-economic assessment and life cycle assessment of the electrochemical reduction of CO2: A review. iScience 2021, 24, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desport, L.; Selosse, S. An overview of CO2 capture and utilization in energy models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C.R.; Abruña, H.D. Electrocatalysis of CO2 reduction at surface modified metallic and semiconducting electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1986, 209, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Franca, R.M.; Azapagic, A. Carbon capture, storage and utilisation technologies: A critical analysis and comparison of their life cycle environmental impacts. J. CO2 Util. 2015, 9, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Der Assen, N.; Jung, J.; Bardow, A. Life-cycle assessment of carbon dioxide capture and utilization: Avoiding the pitfalls. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 2721–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareschino, P.; Mancusi, E.; Urciuolo, M.; Paulillo, A.; Chirone, R.; Pepe, F. Life cycle assessment and feasibility analysis of a combined chemical looping combustion and power-to-methane system for CO2 capture and utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 130, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.; Jeong, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Roh, K.; Lee, J.H. Electrification of CO2 conversion into chemicals and fuels: Gaps and opportunities in process systems engineering. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 170, 108106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.C.; Caramanna, G.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. An overview of current status of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 426–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, R.; Doig, A.; Finnveden, G. The Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Integrated Solid Waste Management: Part 1—Methodology. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2000, 78, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, T.T.; Perrella Balestieri, J.A.; de Toledo Silva, J.M.; Vilanova, M.R.N.; Oliveira, O.J.; Ávila, I. Life cycle assessment of carbon capture and storage/utilization: From current state to future research directions and opportunities. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2021, 108, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, S.-Y.; Li, H.; Cai, J.; Ghani Olabi, A.; Anthony, E.J.; Manovic, V. Recent advances in carbon dioxide utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 125, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkamel, A.; Ba-Shammakh, M.; Douglas, P.; Croiset, E. An Optimization Approach for Integrating Planning and CO2 Emission Reduction in the Petroleum Refining Industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Liu, X.J.; Ma, J.J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.R.; Dong, Y.L.; Yang, Q.-Y. Prospective life cycle assessment of CO2 conversion by photocatalytic reaction. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, R.Q.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Rojas-Michaga, M.F.; Michailos, S.; Pourkashanian, M.; Zhang, X.; Font-Palma, C. Sorption direct air capture with CO2 utilization. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 95, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Treviño, M.A.; Kanani, N.; Jeong-Potter, C.W.; Farrauto, R.J. Bimetallic catalysts for CO2 capture and hydrogenation at simulated flue gas conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 375, 121953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerhofer, A.M.; Fuchs, J.; Müller, S.; Benedikt, F.; Schmid, J.C.; Hofbauer, H. CO2 gasification in a dual fluidized bed reactor system: Impact on the product gas composition. Fuel 2019, 253, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Hu, J.; Liu, H. CO2 capture and in-situ conversion: Recent progresses and perspectives. Green Chem. Eng. 2022, 3, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Abdala, P.M.; Broda, M.; Hosseini, D.; Copéret, C.; Müller, C. Integrated CO2 Capture and Conversion as an Efficient Process for Fuels from Greenhouse Gases. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Sun, S.; Liu, T.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Wu, C. Integrated CO2 Capture and Utilization: Selection, Matching, and Interactions between Adsorption and Catalytic Sites. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 15572–15589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, C.; Cheon, S.; Kim, H.; Lim, H. Mitigating climate change for negative CO2 emission via syngas methanation: Techno-economic and life-cycle assessments of renewable methane production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilberforce, T.; Baroutaji, A.; Soudan, B.; Al-Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G. Outlook of carbon capture technology and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koytsoumpa, E.I.; Bergins, C.; Kakaras, E. The CO2 economy: Review of CO2 capture and reuse technologies. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 132, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ji, N.; Deng, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, H. Alternative pathways for efficient CO2 capture by hybrid processes—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Sandhu, N.K.; McCoy, S.T.; Bergerson, J.A. A life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from direct air capture and Fischer–Tropsch fuel production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brethomé, F.M.; Williams, N.J.; Seipp, C.A.; Kidder, M.K.; Custelcean, R. Direct air capture of CO2 via aqueous-phase absorption and crystalline-phase release using concentrated solar power. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bordejé, E.; González-Olmos, R. Advances in process intensification of direct air CO2 capture with chemical conversion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 100, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Rodgers, J.; Argueta, E.; Biong, A.; Gómez-Gualdrón, D.A. Role of Pore Chemistry and Topology in the CO2 Capture Capabilities of MOFs: From Molecular Simulation to Machine Learning. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 6325–6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cao, X.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; Li, C.; Zhu, G. Research Progress on the Water Stability of a Metal-Organic Framework in Advanced Oxidation Processes. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2021, 232, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postweiler, P.; Engelpracht, M.; Rezo, D.; Gibelhaus, A.; von der Assen, N. Environmental process optimisation of an adsorption-based direct air carbon capture and storage system. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 3004–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Gu, X.; Lin, L.C.; Bakshi, B.R. Toward Sustainable Metal-Organic Frameworks for Post-Combustion Carbon Capture by Life Cycle Assessment and Molecular Simulation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 12132–12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, S.; Bardow, A. Life-cycle assessment of an industrial direct air capture process based on temperature–vacuum swing adsorption. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hao, X.; Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, M.; Long, R.; Gong, W.; Liang, C.; et al. Concentrated Formic Acid from CO2 Electrolysis for Directly Driving Fuel Cell. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Park, K.; Lee, H.; Im, J.; Usosky, D.; Tak, K.; Park, D.; Chung, W.; Han, D.; Yoon, J.; et al. Accelerating the net-zero economy with CO2-hydrogenated formic acid production: Process development and pilot plant demonstration. Joule 2024, 8, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Arán-Ais, R.M.; Jeon, H.S.; Roldan Cuenya, B. Rational catalyst and electrolyte design for CO2 electroreduction towards multicarbon products. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, T.; An, L.; Xia, C.; Zhang, X. Integration of CO2 Capture and Electrochemical Conversion. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 2840–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, A.; Mir, N.; Ewis, D.; El-Naas, M.H.; Amhamed, A.I.; Bicer, Y. Formic acid production through electrochemical reduction of CO2: A life cycle assessment. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 20, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Zhao, H.; Li, T.; Luo, Y.; Fan, G.; Chen, G.; Gao, S.; Shi, X.; Lu, S.; Sun, X. Metal-based electrocatalytic conversion of CO2 to formic acid/formate. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 21947–21960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markewitz, P.; Kuckshinrichs, W.; Leitner, W.; Linssen, J.; Zapp, P.; Bongartz, R.; Schreiber, A.; Müller, T.E. Worldwide innovations in the development of carbon capture technologies and the utilization of CO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7281–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortlever, R.; Shen, J.; Schouten, K.J.P.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Koper, M.T.M. Catalysts and Reaction Pathways for the Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4073–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhong, H.R.M.; Ma, S.; Kenis, P.J. Electrochemical conversion of CO2 to useful chemicals: Current status, remaining challenges, and future opportunities. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Arquer, F.P.; Dinh, C.T.; Ozden, A.; Wicks, J.; McCallum, C.; Kirmani, A.R.; Nam, D.-H.; Gabardo, C.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Wang, X.; et al. CO2 electrolysis to multicarbon products at activities greater than 1 A cm−2. Science 2020, 367, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.A.; Kanan, M.W. The future of low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis depends on solving one basic problem. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, O.B.; Lucht, B.L. Interfacial Issues and Modification of Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Li Metal Anode in Liquid and Solid Electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2203791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.H.; Lai, Y.J.S.; Tsai, C.K.; Fu, H.; Doong, R.A.; Westerhoff, P.; Rittmann, B.E. Efficient CO2 Conversion through a Novel Dual-Fiber Reactor System. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13717–13725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Bravo, P.; Debecker, D.P. Combining CO2 capture and catalytic conversion to methane. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 53–65, Correction in Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2021, 3, 255–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42768-021-00078-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fortes, M.; Schöneberger, J.C.; Boulamanti, A.; Tzimas, E. Methanol synthesis using captured CO2 as raw material: Techno-economic and environmental assessment. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, E.; Tang, J. Insight on Reaction Pathways of Photocatalytic CO2 Conversion. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 7300–7316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Khan, M.H.; Daiyan, R.; Neal, P.; Haque, N.; MacGill, I.; Amal, R. A framework for assessing economics of blue hydrogen production from steam methane reforming using carbon capture storage & utilisation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 22685–22706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Pragt, J.J.; Vos, H.J.; Bargeman, G.; de Groot, M.T. Novel efficient process for methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 284, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.A.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Goeppert, A. Anthropogenic chemical carbon cycle for a sustainable future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12881–12898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, G.Z.S.; Foo, J.J.; Tan, X.Q.; Ong, W.J. Transition into Net-Zero Carbon Community from Fossil Fuels: Life Cycle Assessment of Light-Driven CO2 Conversion to Methanol Using Graphitic Carbon Nitride. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 5547–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chang, F.; Lundgren, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Engvall, K.; Ji, X. Energy, Cost, and Environmental Assessments of Methanol Production via Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 from Biosyngas. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 2810–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, G.; Sun, P.; Elgowainy, A.; Wang, M. Technoeconomic and Life Cycle Analysis of Synthetic Methanol Production from Hydrogen and Industrial Byproduct CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 5248–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Kumar, N.; Aho, A.; Roine, J.; Heinmaa, I.; Murzin, D.Y.; Ivaska, A. Determination of acid sites in porous aluminosilicate solid catalysts for aqueous phase reactions using potentiometric titration method. J. Catal. 2016, 335, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitopi, S.; Bertheussen, E.; Scott, S.B.; Liu, X.; Engstfeld, A.K.; Horch, S.; Seger, B.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Chan, K.; Hahn, C.; et al. Progress and Perspectives of Electrochemical CO2 Reduction on Copper in Aqueous Electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7610–7672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Zhou, J.; Ren, J. Recent advances in CO2 capture and utilization: From the perspective of process integration and optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 216, 115688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Liao, P.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H. Recent Progress in Integrated CO2 Capture and Conversion Process Using Dual Function Materials: A State-of-the-Art Review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan Law, Z.; Pan, Y.T.; Tsai, D.H. Calcium looping of CO2 capture coupled to syngas production using Ni-CaO-based dual functional material. Fuel 2022, 328, 125202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, B.; Taniguchi, S.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Kataoka, S. Integrating carbon capture and utilization into the glass industry: Economic analysis of emissions reduction through CO2 mineralization. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gallent, E.; Vankani, C.; Sánchez-Martínez, C.; Anastasopol, A.; Goetheer, E. Integrating CO2capture with electrochemical conversion using amine-based capture solvents as electrolytes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 4269–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Rahaman, M.; Andrei, V.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Roy, S.; Reisner, E. Integrated capture and solar-driven utilization of CO2 from flue gas and air. Joule 2023, 7, 1496–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, R.; Gao, S. Sustainable CO2 management through integrated CO2 capture and conversion. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 72, 102493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.