Abstract

The HOX gene family plays an indispensable role in regulating embryonic development, cell differentiation, and morphogenesis. This study employed bioinformatics approaches for systematic analysis, ultimately identifying 33 HOX gene family members from the donkey genome. Physicochemical property analysis revealed that the number of amino acids encoded ranged from 94 to 444, with 31 members classified as alkaline proteins. Their secondary structure was predominantly composed of random coils and alpha helices, and all members were localized to the nucleus. Conserved motif analysis further demonstrated that all donkey HOX family proteins contained highly conserved motifs 1 and 2. Along with three other species, the 33 donkey HOX genes were clustered into eight phylogenetic subgroups. Furthermore, collinearity analysis indicated a high degree of collinearity between the donkey and horse HOX gene families. Gene Ontology analysis confirmed the significant role of the donkey HOX gene family in regulating embryonic development and skeletal system formation. Tissue expression profile analysis revealed significant differences in the expression levels of the 33 HOX genes across 13 different tissues. This study not only systematically identified and characterized the donkey HOX gene family but also provided valuable insights into the genetic regulation mechanisms of key traits in donkey molecular breeding.

1. Introduction

Homeobox genes are a class of core regulatory genes that are widely distributed across various organisms and encode transcription factors. These genes primarily regulate the expression of downstream target genes through the proteins they produce. Their products play crucial roles in processes such as embryonic development, cell differentiation, and morphogenesis by controlling the spatiotemporal expression of these target genes [1,2]. The HOX gene family is characterized by several distinctive features, including high conservation, clustered organization, and spatiotemporal collinearity. High conservation is exemplified by a shared 180 bp highly conserved DNA sequence (the homeobox) that encodes a protein domain known as the homeodomain, which consists of 60 amino acids [3,4]. The HOX family is extensive and diverse, typically organized into four distinct clusters—HOXA, HOXB, HOXC, and HOXD—each located on different chromosomes. Additionally, HOX gene clusters exhibit a high degree of organizational coherence, with all genes transcribed from the same DNA strand [3,5]. HOX expression demonstrates collinearity, meaning that genes within the cluster activate sequentially along the 3′→5′ direction of the chromosome. The expression regions of HOX genes are strictly partitioned along the anterior–posterior axis of the embryo: genes located at the 3′-end are expressed in the anterior region, while those at the 5′-end are expressed in the posterior region, with intermediate genes expressed in the transitional zone between them. Furthermore, within the same axial region, if both 3′-end and 5′-end HOX genes are expressed simultaneously on a single chromosome, the 5′-end genes exhibit posterior prevalence [2,6].

HOX genes are crucial regulatory elements that govern vertebral patterning in vertebrates. Mutations in these genes can lead to variations in vertebral morphology and number. Specifically, the loss of function in HOXC8 and HOXD8 primarily disrupts the patterning of the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, while the loss of HOXB8 affects the cervicothoracic region. The simultaneous knockout of two or three HOX genes results in more severe and widespread defects [7]. Ectopic expression of HOXC8 in mice induces skeletal abnormalities; gain-of-function mutations in this gene can transform the first lumbar vertebra into an additional thoracic vertebra, complete with a corresponding pair of ribs [7]. In mouse models where all members of the HOX10 or HOX11 gene families are knocked out, the complete loss of HOX10 function inhibits the formation of lumbar vertebral bodies. In the absence of HOX11 function, the sacral vertebrae fail to develop normally, with vertebrae destined to form the sacrum instead exhibiting morphological characteristics typical of lumbar vertebrae [8]. Observations of HOXD4 mutant mice reveal distinctive skeletal abnormalities in both heterozygous and homozygous individuals, specifically manifested as the homeotic transformation of the second cervical vertebra (C2) into the first cervical vertebra (C1), accompanied by malformations of the neural arches and basioccipital bones in the first three cervical vertebrae (C1–C3) [9]. Additionally, mice with mutations in the HOX5, HOX6, and HOX9 genes also display abnormalities in the ribs and sternum [10].

The molecular mechanisms by which HOX genes regulate vertebral development provide a compelling genetic framework for understanding economically important skeletal traits in livestock species, including donkeys. Given the documented effects of HOX gene mutations on vertebral number and morphology in model organisms, these genes represent promising candidates for genetic improvement of body conformation traits in donkey breeding.

China has a long-standing tradition of consuming donkey meat, which is characterized by high protein content, a rich profile of essential amino acids, high levels of unsaturated fatty acids, and low fat, cholesterol, and calories, making it a high-quality meat source [11]. Additionally, donkey-hide gelatin (ejiao) has been a vital component of traditional Chinese medicine, used for millennia as a valuable herbal remedy known for its blood-nourishing and stamina-enhancing properties [12]. With the growth of the health industry, the market demand for donkey meat, milk, and related products continues to expand. However, the inherent reproductive characteristics of donkeys, such as single births and long generation intervals, severely constrain industrial supply. Consequently, enhancing individual production performance through genetic improvement has emerged as a critical developmental strategy. Vertebral number is a significant economic trait in livestock, with variations that can substantially impact body conformation, hide yield, wool production, and meat production. Existing research indicates that an additional vertebra in Dezhou donkeys correlates with positive increases in both body length and carcass weight. Statistical analysis reveals that an extra thoracic vertebra in Dezhou donkeys increases average body length by 4.3 cm, while an additional lumbar vertebra contributes an increase of 2.4 cm in average body length. Each additional vertebra is associated with an average live weight gain of 7.2 kg and a net hide weight gain of 0.65 kg [13], highlighting its significant breeding value and economic returns.

Given the pivotal role of the HOX gene family in morphogenesis and vertebral development, this study utilizes donkeys as the model organism. Subsequent analyses included chromosomal localization, physicochemical properties, secondary structure prediction, subcellular localization, gene structure, conserved motifs, phylogenetic analysis, interspecies collinearity assessment, Ka/Ks analysis, expression patterns, and functional enrichment. Therefore, this study aims to identify and characterize members of the donkey HOX gene family through the bioinformatics methods and establish a foundation for further investigation into the functional and regulatory mechanisms of the donkey HOX gene family.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Members of the Donkey HOX Gene Family

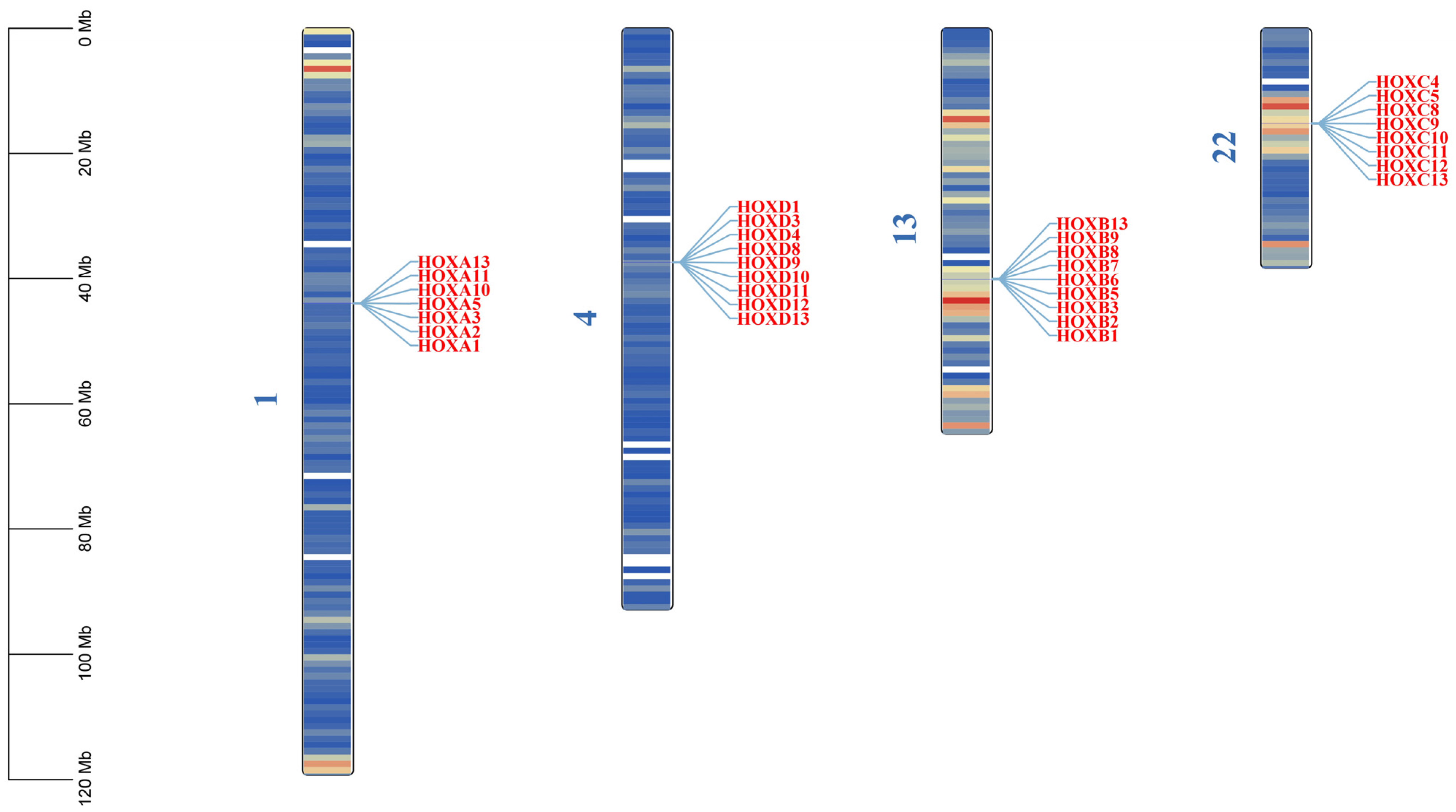

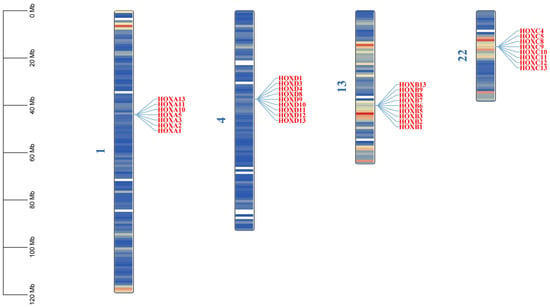

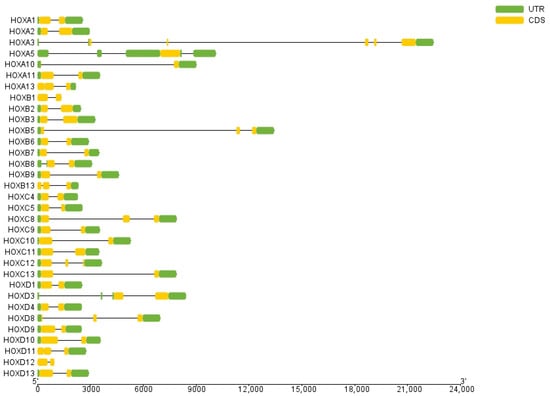

Through HMMER (v3.3.2+dfsg-1)and TBtools Ⅱ-BLAST (v2.340) searches, combined with conserved domain validation using CDD and SMART databases, 33 HOX gene family members were identified in the donkey genome. These genes range in length from 958 to 24,874 bp. Sixteen genes are located on the forward strand, while 17 are on the reverse strand (Table 1). The HOX genes are distributed across four chromosomes: 1, 4, 13, and 22 (Figure 1). The number of HOX genes in donkeys (33) is lower than in humans (39), horses (35), and cattle (39), with the primary missing genes being HOXA4, HOXA6, HOXA7, HOXA9, HOXB4, and HOXC6 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Basic information of HOX gene family in donkeys.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal location of HOX gene family in donkeys. The color on the chromosome represents the size of gene density in the 1 MB window, blue represents the region with low gene density, and red is the opposite.

Table 2.

The HOX gene family among donkeys, humans, horses, and cattle.

2.2. Analysis of the Basic Properties of Proteins from the Donkey HOX Gene Family

Analysis of physicochemical properties revealed that the amino acid length of donkey HOX family members ranged from 94 (HOXA10) to 444 (HOXA3) (Table 3). Protein molecular weights varied between 11,452.25 Da (HOXA10) and 47,378.77 Da (HOXA3). The theoretical isoelectric point (pI) ranged from 5.04 (HOXB2) to 10.76 (HOXD8), with 31 members classified as alkaline proteins (pI > 7). The instability index ranged from 32.48 (HOXA10) to 90.52 (HOXB2). The aliphatic index ranged from 41.74 (HOXD9) to 73.59 (HOXD12). The grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) ranged from −1.518 (HOXD8) to −0.288 (HOXA13). All GRAVY values were negative, indicating that all HOX proteins are hydrophilic.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of HOX gene family proteins in donkeys.

Secondary structure prediction revealed that donkey HOX proteins predominantly contain random coils, followed by α-helices, with β-turns representing the smallest proportion. Subcellular localization analysis showed that all donkey HOX proteins are localized to the nucleus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary structure prediction and subcellular localization of HOX gene family proteins in donkeys.

2.3. Analysis of Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs in the Donkey HOX Gene Family

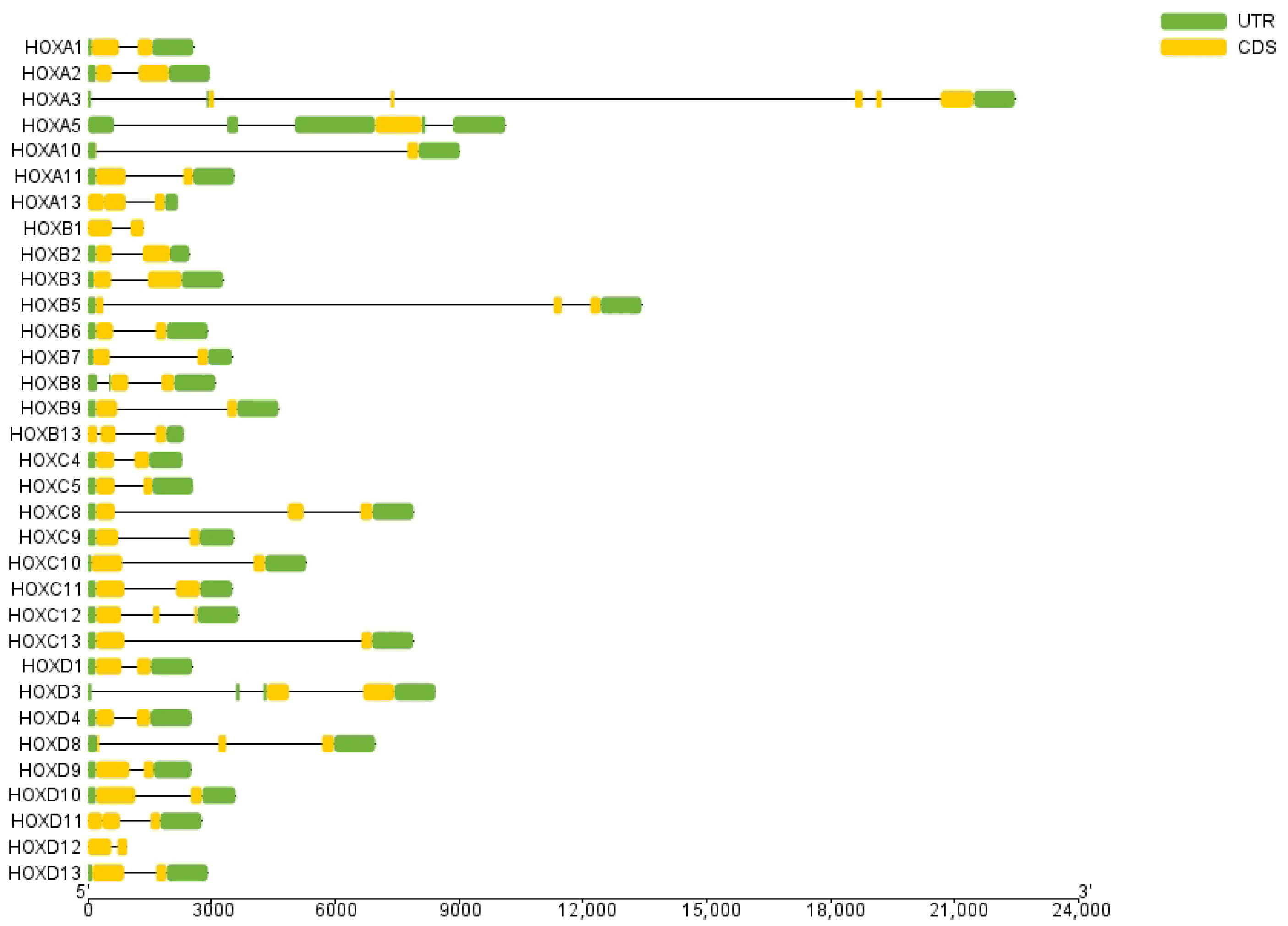

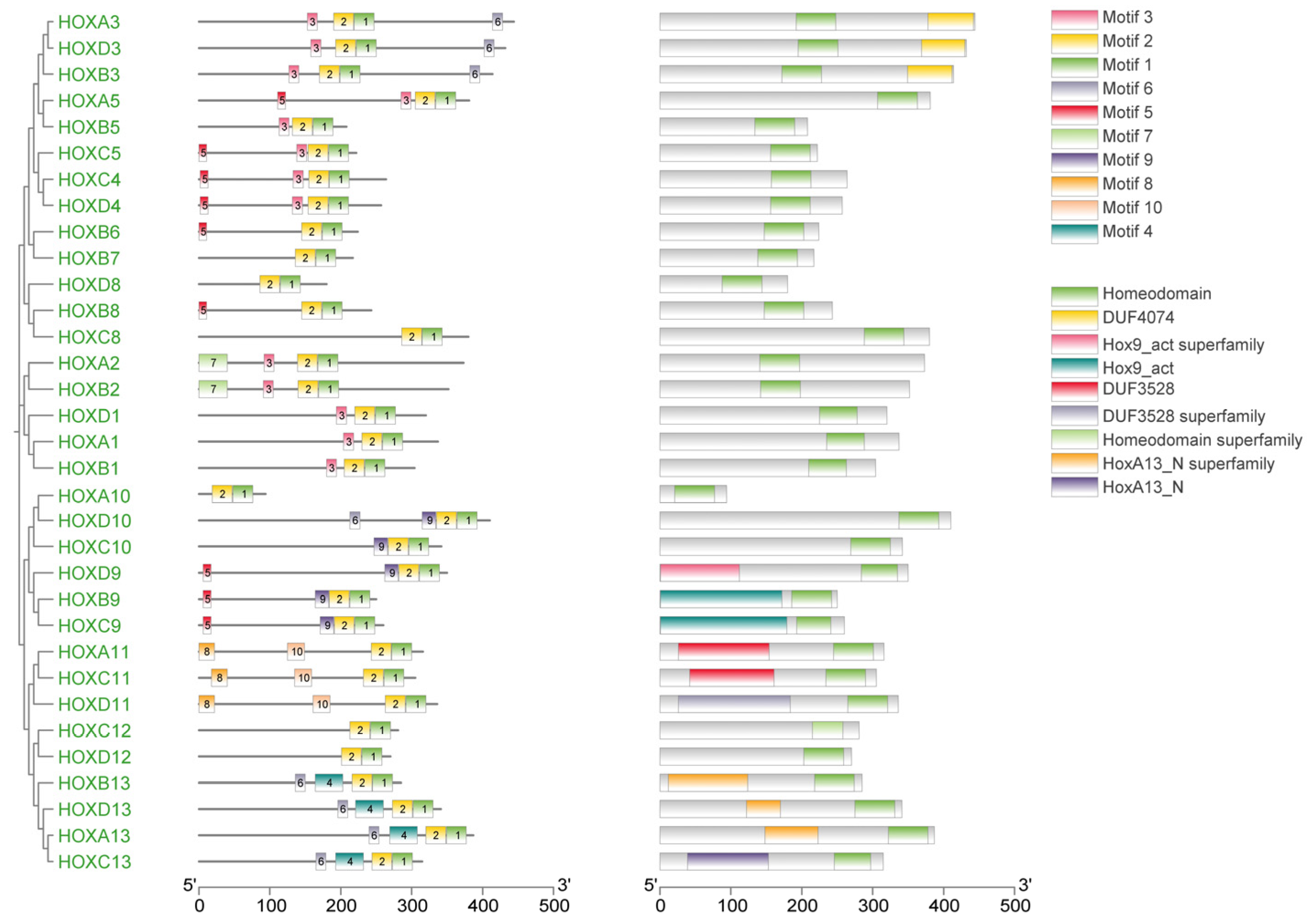

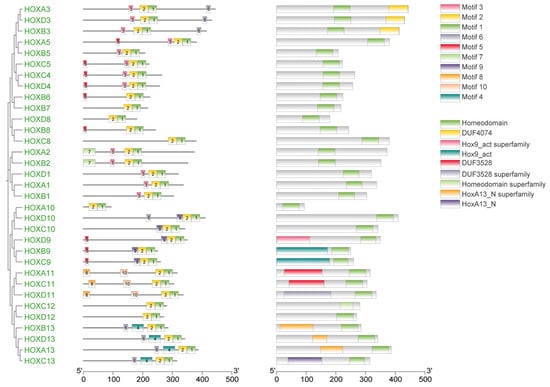

Gene structure analysis revealed that exon numbers in donkey HOX gene family members ranged from 1 to 5 (Figure 2). HOXA5 contained the fewest exons (1), while HOXA3 contained the most (5). All genes except HOXA5 contained introns, with HOXA3 having the highest number. These results indicate structural diversity among donkey HOX family members, reflecting evolutionary divergence within this gene family. Conserved motif analysis identified ten distinct motifs in the donkey HOX protein sequences (Figure 3). Motifs 1 and 2 were present in all 33 HOX family members, indicating high conservation of these sequences. The remaining motifs showed variable distribution patterns across different HOX members. This conservation pattern suggests that motifs 1 and 2 likely represent core functional domains essential for HOX protein function. Analysis results from the PFAM (PF00046) and CDD databases confirmed that both motif 1 and motif 2 are located within the homeodomain of the HOX protein. Functional analysis demonstrates that motif 1 possesses DNA-binding capability and DNA-binding transcription factor activity; motif 2 has also been confirmed to participate in the DNA-binding process.

Figure 2.

Structure analysis of HOX gene family members in donkey.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree, motif and domain relationship of donkey HOX gene family.

2.4. Interspecies Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of the HOX Gene Family

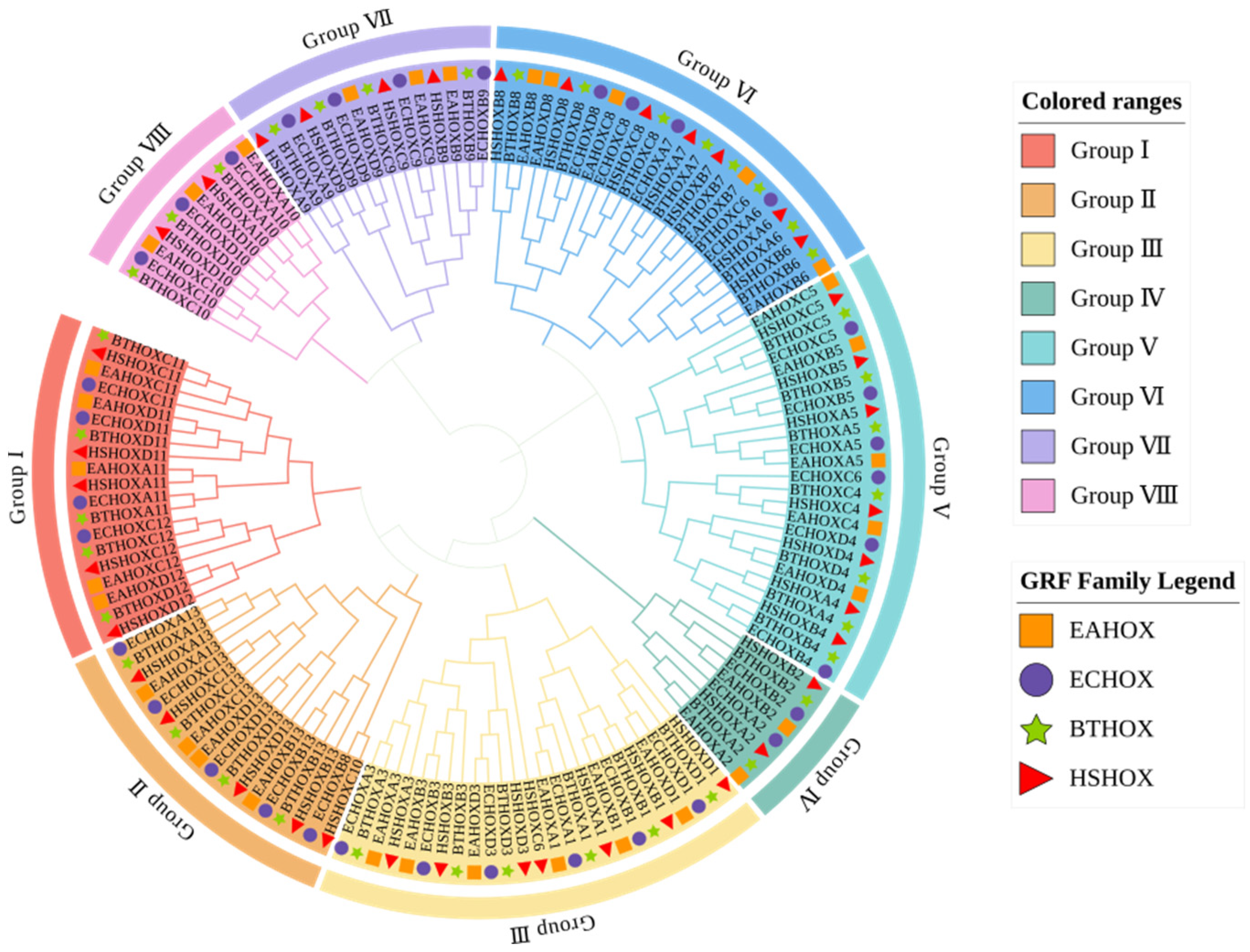

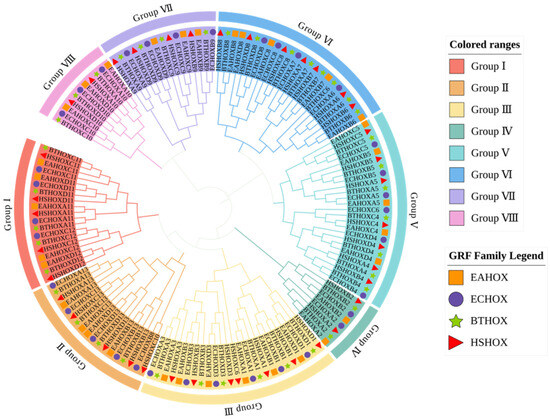

To investigate the evolutionary relationships among donkey HOX gene family members and those of other species, phylogenetic analysis was performed using HOX protein sequences from four species: donkey, horse, cattle, and human. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method in MEGA software (v12.0.11) (Figure 4, Supplementary Materials S2). The dataset comprised 145 HOX proteins: 33 from donkey, 34 from horse, 39 from cattle, and 39 from human.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree among species of HOX gene family.

The phylogenetic tree clustered 145 HOX genes into eight subfamilies (Group I to Group VIII). HOX gene family members from the four species clustered together within each subfamily, indicating close evolutionary relationships and potential functional conservation. Each subfamily contained orthologous gene pairs between donkey and horse. Group II contained the fewest orthologous pairs (one pair: HOXD13), while Group III contained the most (five pairs: HOXB3, HOXD3, HOXA1, HOXB1, and HOXD1). Groups IV and VII each contained two pairs, while Groups I, V, VI, and VIII each contained three pairs.

2.5. Interspecies Collinearity Analysis

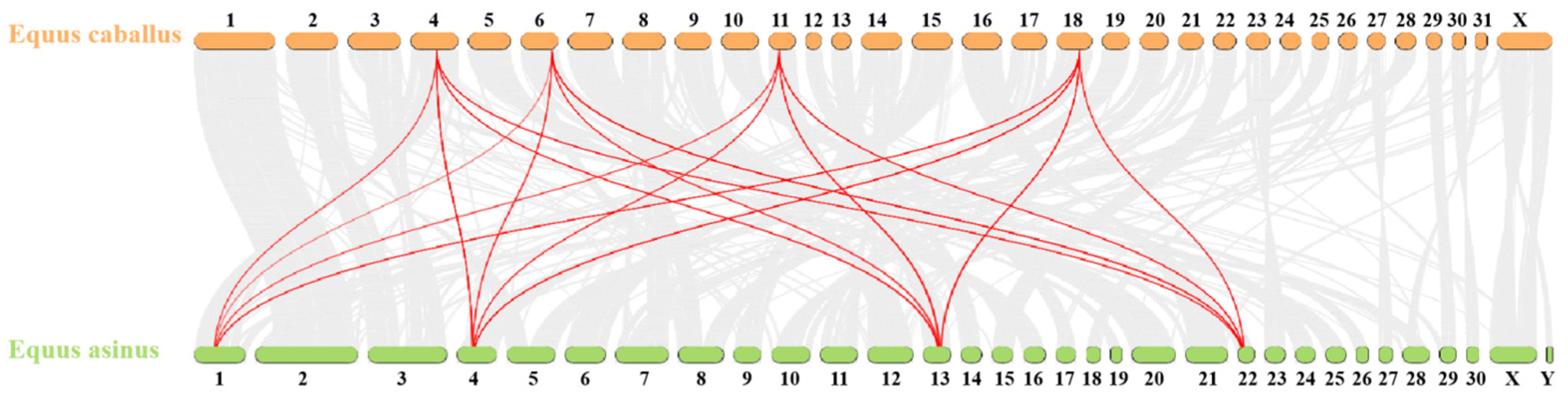

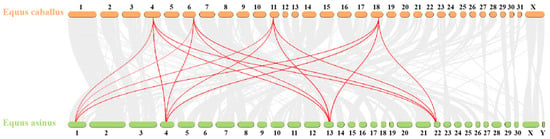

To further elucidate the evolutionary relationships within the donkey HOX gene family, an interspecies collinearity analysis was conducted on the HOX gene families of donkeys and horses. As shown in Figure 5 and Table 5, 55 pairs of homologous genes were identified between donkeys and horses, exhibiting high collinearity. This indicates a close phylogenetic relationship between the two species.

Figure 5.

Collinear analysis of HOX gene family in Equus asinus and Equus caballus. The gray line represents all collinearity blocks of the whole genome; The red line represents the collinearity of HOX gene family.

Table 5.

Interspecific homologous gene pairs of the HOX gene gamily in Equus asinus and Equus caballus. “==” represents the collinearity of genes in two species.

2.6. Ka/Ks Analysis

To assess selective pressure on the donkey HOX gene family, the ratio of non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution rates was calculated for all gene pairs. The Ka/Ks ratio indicates the mode of selection: Ka/Ks < 1 suggests purifying selection, Ka/Ks = 1 indicates neutral evolution, and Ka/Ks > 1 indicates positive selection. Analysis revealed that all Ka/Ks ratios among donkey HOX gene family members were less than 1 (Table 6), indicating that this gene family has evolved under purifying selection. This selective constraint suggests strong functional conservation of HOX genes, consistent with their essential roles in development.

Table 6.

Ka/Ks analysis of HOX gene family members in donkey.

2.7. Functional Enrichment Analysis of the Donkey HOX Gene Family

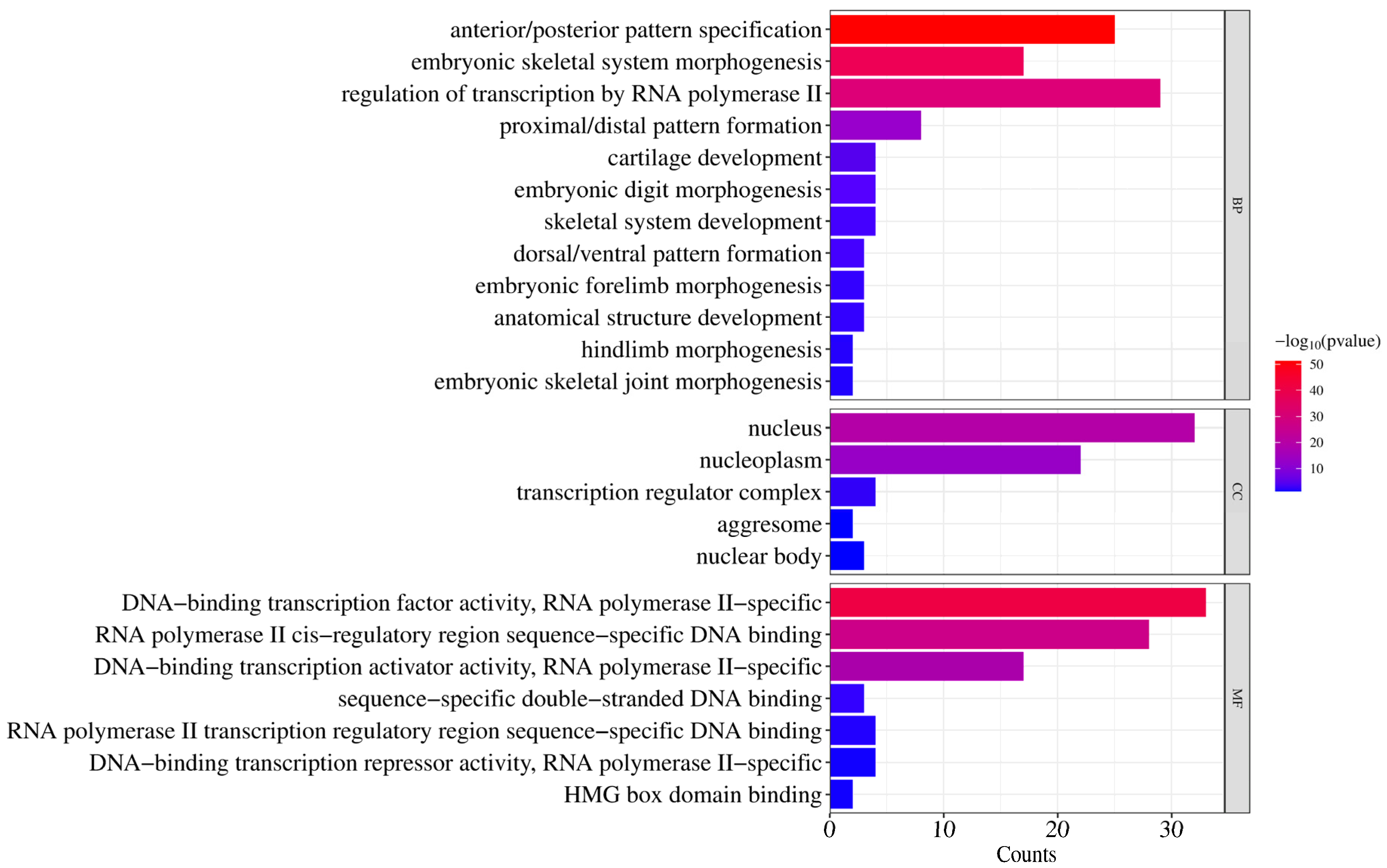

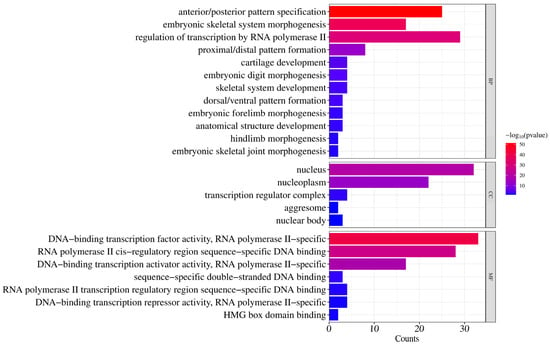

To elucidate the biological functions of donkey HOX genes, GO enrichment analysis was performed across three categories: biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

GO enrichment analysis of donkey HOX family members.

For biological processes, significantly enriched terms included anterior/posterior pattern specification (GO:0009952), embryonic skeletal system morphogenesis (GO:0048704), proximal/distal pattern formation (GO:0009954), and cartilage development (GO:0051216). These terms are associated with skeletal system development and body axis patterning during embryogenesis. Additionally, regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (GO:0006357) was significantly enriched, indicating transcriptional regulatory functions.

For cellular components, significant enrichment was observed for nucleus (GO:0005634), nucleoplasm (GO:0005654), transcription regulator complex (GO:0005667), nuclear body (GO:0016604), and aggresome (GO:0016235). These results confirm nuclear localization of HOX proteins, consistent with their roles in transcriptional regulation.

For molecular functions, enrichment was primarily observed in DNA−binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II−specific (GO:0000981), RNA polymerase II cis−regulatory region sequence−specific DNA binding (GO:0000978), and DNA-binding transcription activator activity, RNA polymerase II−specific (GO:0001227). These findings confirm that HOX proteins function as sequence−specific transcription factors.

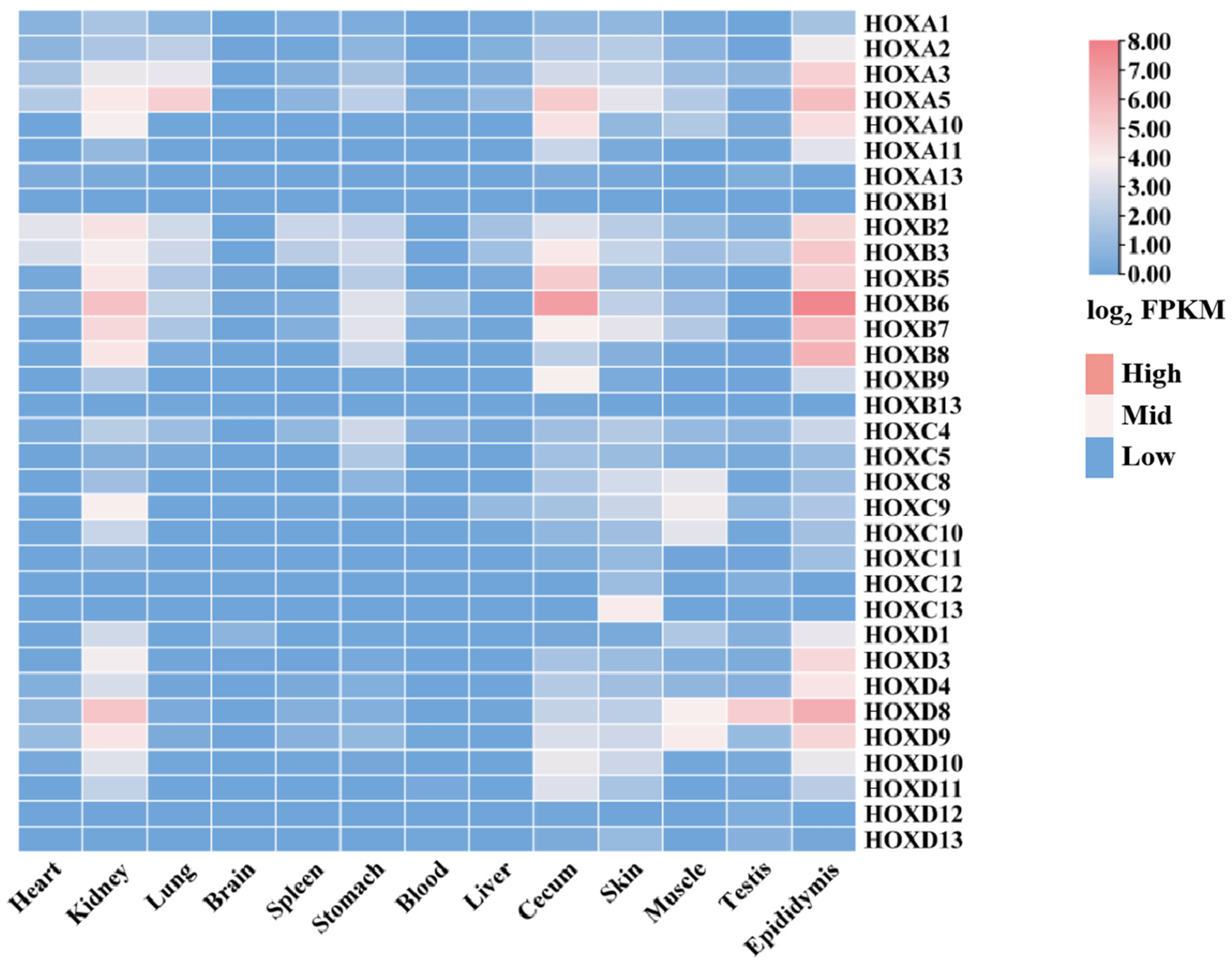

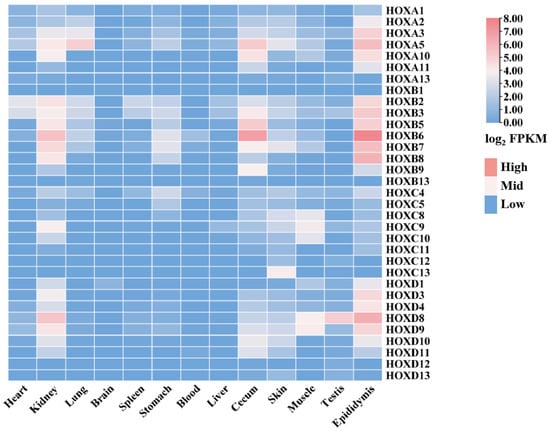

2.8. Expression Analysis of Members of the Donkey HOX Gene Family

To investigate the expression patterns of the HOX gene family across different donkey tissues, transcriptomic data from 13 tissues were analyzed using RNA-seq data (Supplementary Materials S1) obtained from the NCBI database. This analysis revealed distinct tissue-specific expression profiles for HOX family members (Figure 7, Supplementary Materials S1).

Figure 7.

Expression of donkey HOX family members in different tissues.

Notable expression patterns included the following: HOXB2 and HOXB3 showed high expression in heart, spleen, and liver. HOXB6 and HOXB7 were highly expressed in kidney and stomach. HOXA3 exhibited the highest expression in lung. Most HOX family members showed low expression levels (FPKM < 1) in brain. HOXB6 showed the highest expression in blood, cecum, and epididymis. HOXC13, HOXA5, and HOXB7 were highly expressed in skin. HOXC8, HOXC9, HOXC10, HOXD8, and HOXD9 showed high expression in muscle. HOXD8 exhibited the highest expression in testis.

These tissue-specific expression patterns suggest that HOX genes may play differentiated regulatory roles in tissue development and functional maintenance. These findings provide a foundation for further investigation into the functions and regulatory mechanisms of the donkey HOX gene family.

3. Discussion

In this study, 33 HOX genes were identified in the donkey genome, representing a reduction in six members compared to the 39 HOX genes found in humans. This difference likely reflects species-specific gene loss events, variations in genome assembly quality, or lineage-specific evolutionary pressures, consistent with observations in other mammalian lineages [14,15]. The donkey HOX genes are organized into four clusters distributed across chromosomes 1, 4, 13, and 22, supporting the canonical vertebrate HOX cluster organization that originated from two rounds of whole-genome duplication during early vertebrate evolution [16,17]. This clustered arrangement is evolutionarily conserved and functionally significant, as it facilitates coordinated transcriptional regulation through shared chromatin domains [18]. In this study, all four HOX gene clusters exhibited a 3′→5′ linear arrangement on the chromosomes. During embryonic development, the genes within the HOX clusters were sequentially activated and expressed in a 3′-to-5′ direction. Specifically, the genes located at the 3′ end were predominantly expressed in the anterior tissues of the embryo (e.g., head and neck), whereas the genes proximal to the 5′ end were concentrated in the posterior tissues (e.g., lumbar and caudal). These expression patterns are consistent with the spatial collinearity characteristics of the HOX gene family.

Physicochemical analysis revealed that donkey HOX proteins are predominantly alkaline (31 of 33 members) and uniformly hydrophilic, with molecular weights ranging from 11.5 to 47.4 kDa [19]. These properties are consistent with nuclear localization and DNA-binding function. Secondary structure prediction showed high proportions of random coils and α-helices, with random coils likely serving as flexible linkers between structured domains [20]. Intrinsically disordered regions are known to enhance protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions through conformational plasticity [21], which may contribute to the sequence-specific DNA-binding capabilities of HOX transcription factors. Indeed, subcellular localization analysis confirmed nuclear localization for all 33 HOX proteins, consistent with their role as transcription factors that must access nuclear to regulate target gene expression [22,23].

Gene structure analysis revealed that most donkey HOX genes contain 2–3 exons and 1–2 introns, with HOXA3 exhibiting the most complex structure. Conserved motif analysis identified ten distinct motifs across the HOX family, with motifs 1 and 2 universally present in all 33 members, indicating strong functional constraint on these core domains. Moreover, as a highly conserved class of transcription factors, HOX proteins play crucial regulatory roles in key processes such as somite patterning and organogenesis during animal embryonic development. The functional significance of these roles may have driven the evolutionary conservation of these motifs. Notably, paralogous groups showed consistent motif compositions; for example, HOXA3/HOXB3/HOXD3 and HOXA13/HOXB13/HOXC13/HOXD13 exhibited similar motif arrangements. This conservation pattern suggests functional similarity within paralogous groups and likely reflects purifying selection to maintain essential developmental functions. Structural variation among HOX family members has been attributed to evolutionary events including duplications, insertions, and deletions [24,25], representing a balance between functional constraint and adaptive diversification.

To further understand the evolutionary relationships within this gene family, phylogenetic analysis of HOX proteins from donkey, horse, cattle, and human was performed. The results revealed that orthologous genes clustered together across species, indicating that inter-species conservation of individual HOX genes exceeds intra-family conservation within a single species. This pattern is characteristic of genes under strong purifying selection to maintain conserved developmental functions. Collinearity analysis between donkey and horse genomes showed high synteny for HOX clusters, although their chromosomal positions differed substantially (chromosomes 1, 4, 13, 22 in donkey versus 4, 6, 11, 18 in horse). These chromosomal rearrangements [26] likely occurred during equid divergence, yet the preservation of cluster integrity underscores the functional importance of maintaining HOX gene linkage for coordinated transcriptional regulation.

GO enrichment analysis provided functional insights into the biological roles of donkey HOX genes. Significant overrepresentation was observed for biological processes including anterior–posterior pattern specification, embryonic skeletal system morphogenesis, and transcriptional regulation by RNA polymerase II. These findings align with established HOX functions in body axis patterning, limb development, and skeletal formation [3,27], confirming the evolutionary conservation of HOX gene roles across mammals. Specifically, the two SNPs g.15179224C>T and g.15179674G>A in HOXC8 gene were significantly correlated with carcass weight, lumbar vertebrae length, and lumbar vertebrae number in Dezhou donkeys [28]. This indicates that HOXC8 gene is a key gene influencing the number of vertebrae and body weight in the Dezhou donkey, and it may serve as a potential genetic marker for selecting and breeding high-quality, high-yielding Dezhou donkey strains. The enrichment of transcription factor activities at the molecular function level substantiates the regulatory nature of HOX proteins. These results provide a functional framework for investigating HOX gene contributions to economically important traits in donkeys, particularly vertebral number variation, which directly impacts body conformation, carcass weight, and hide yield [13].

Among the HOX genes identified in donkeys, several paralogs merit particular attention for their established roles in vertebral patterning. HOXC8, located on chromosome 22, is a key regulator of thoracolumbar vertebral identity; loss-of-function mutations in mice cause homeotic transformations of lumbar vertebrae toward thoracic identity, while gain-of-function mutations can induce the formation of supernumerary ribs. The association of HOXC8 polymorphisms with vertebral number variation in Dezhou donkeys suggests this gene as a primary target for marker-assisted selection. Similarly, HOXD4 plays a critical role in cervical vertebral specification, with mutations causing anterior transformations of the axis (C2) into atlas-like (C1) morphology. The HOX10 paralogs (HOXA10, HOXC10, HOXD10) collectively specify lumbar vertebral identity; complete loss of HOX10 function abolishes lumbar vertebral formation entirely. The HOX11 paralogs (HOXA11, HOXC11, HOXD11) are essential for sacral vertebral development, with their loss causing sacral vertebrae to adopt lumbar-like characteristics. These paralog-specific functions provide a molecular basis for understanding natural variation in vertebral formulas across donkey populations and offer specific genetic targets for breeding programs aimed at optimizing body conformation.

Tissue expression profiling revealed distinct spatial patterns consistent with known HOX functions. The near-absence of HOX expression in brain tissue (FPKM < 1 for most genes) reflects the anterior expression boundary that typically excludes forebrain regions, a pattern essential for proper brain regionalization [29]. In contrast, robust expression of multiple HOX genes in kidney indicates active roles in organogenesis and tissue homeostasis [30]. Several expression patterns provide insights into tissue-specific HOX functions. In skin, 30 HOX genes were expressed, further confirming the role of HOX genes in skin development, homeostasis maintenance, and regeneration [31], with HOXC13 showing the highest levels, consistent with its established role in hair follicle development and epithelial differentiation [32]. Donkey hide is the primary raw material for producing Ejiao (donkey-hide gelatin), with collagen as its main component [33]. The expression level of HOXC13 may regulate the local collagen yield and the compactness of fiber arrangement by affecting hair follicle density and growth status, thereby enhancing the gelatin production rate. HOXC13 is expected to serve as a potential molecular marker for evaluating the collagen quality of donkey hide, which provides a theoretical basis for breeding skin-purpose donkey strains that are more suitable for producing high-quality gelatin. In muscle tissue, HOXD9 showed peak expression, suggesting involvement in myogenesis and skeletal patterning [34,35]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that homeobox transcription factors may play a crucial role in skeletal muscle by regulating muscle fiber types and intramuscular fat [36,37], thereby influencing meat yield and quality in livestock.

The hematopoietic system showed predominant HOXB6 expression; the dysregulation of this gene has been implicated in acute myeloid leukemia through aberrant differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells [38]. In reproductive tissues, HOXD8 was highly expressed in testis, while 26 genes showed active expression (FPKM > 1) in epididymis, indicating potential roles in male fertility through regulation of epididymal function [39,40,41]. Finally, HOXA5 showed elevated expression in lung tissue, consistent with its essential function in respiratory tract morphogenesis; HOXA5 knockout mice exhibit severe postnatal lung defects including alveolar damage and emphysema [42].

This comprehensive characterization establishes a foundation for understanding HOX gene functions in donkey development and physiology. The tissue expression patterns, combined with functional enrichment data, suggest that specific HOX genes regulate vertebral patterning—a trait with significant economic value affecting body length (additional thoracic vertebra: +4.3 cm; additional lumbar vertebra: +2.4 cm), carcass weight (+7.2 kg per vertebra), and hide yield (+0.65 kg per vertebra) [13]. The conservation of HOX gene function across mammals indicates that insights from model organisms can inform donkey breeding strategies. Future functional studies using genome editing and chromatin profiling will be necessary to validate the regulatory roles of specific HOX genes in vertebral number determination and to develop molecular markers for selection of economically valuable traits in donkey production.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Preparation and Gene Family Member Identification

Initially, the complete genome sequence, gene annotation file, and protein sequence file of the donkey were obtained from the Ensembl database (https://asia.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html (accessed on 22 September 2025)). Subsequently, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile (PF00046) for the HOX gene family was downloaded from the Pfam database. The hmmsearch program, part of the HMMER software (v3.3.2+dfsg-1, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, VA, USA) suite, was employed to analyze the donkey protein sequence file, facilitating the identification of HOX gene family members. Following this, the BLAST function within TBtools-II (v2.340, CJ-Chen Lab, Guangzhou, China) was utilized to conduct alignment between donkey protein sequences and horse HOX family protein sequences, which yielded potential candidate protein sequences for the donkey HOX family. The e-value for both HMMER and BLAST searches was set to 1 × 10−5. The intersection of results from both methodologies was taken to refine candidate members of the HOX gene family. The candidate gene family protein sequences were submitted to the CDD and SMART databases for conserved domain validation. Sequences lacking the HOX domain were removed to obtain the final gene family members. Gene annotation information corresponding to the HOX gene family member IDs was extracted from the donkey GTF gene annotation file. TBtools-II software (v2.340) was used to generate the chromosomal localization map of the donkey HOX genes.

4.2. Physicochemical Properties of Proteins, Secondary Structure Prediction, and Subcellular Localization Analysis

The physicochemical properties of donkey HOX gene family members were analyzed using the Protein Parameter Calculator feature in TBtools-II software, including amino acid residues, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). The secondary structure of HOX proteins was predicted using the SOPMA online tool (https://npsa.lyon.inserm.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html (accessed on 24 September 2025)). Subcellular localization analysis of HOX proteins was performed using the WoLF PSORT online tool (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/ (accessed on 24 September 2025)).

4.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis

Gene structures were visualized using the GXF Rename and Visualize Gene Structure functions in TBtools-II software. Predictions on protein sequence files of the HOX gene family were performed using NCBI Batch CD-Search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi (accessed on 27 September 2025)) to obtain hitdata files. Subsequently, the Simple MEME Wrapper function in TBtools-II was employed to perform conserved motif analysis on the protein sequences of the donkey HOX gene family, with the motif count set to 10. Finally, the Gene Structure View function in TBtools-II was used to visualize the results.

4.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

To investigate the evolutionary relationships among members of the HOX gene family, multiple sequence alignments of HOX protein sequences from donkeys, horses, cattle, and humans were performed using MEGA (v12.0.11, Institute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method, with the bootstrap value set to 1000, the substitution model set to p-distance and other parameters left at default settings. The resulting tree was then visualized using the online tool iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)).

4.5. Interspecies Collinearity Analysis

Based on the gene sequence files and gene annotation files of donkeys and horses, interspecies collinearity analysis was performed using the One Step MCScanX-Super Fast function in TBtools-II. Subsequently, visualization was achieved through the Dual Synteny Plot for MCScanX function within TBtools-II.

4.6. Ka/Ks Analysis

Intraspecific collinearity analysis was performed using the One Step MCScanX-Super Fast feature in TBtools-II to obtain gene pair files, then the Ka/Ks ratio was calculated using the Simple Ka/Ks Calculator (NG) feature in TBtools-II.

4.7. Functional Enrichment Analysis

Using the online tool DAVID (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)), gene functional enrichment analysis was performed on the HOX gene family across three categories: biological process, molecular function, and cellular component.

4.8. Tissue Expression Analysis

Raw RNA-seq sequencing data (PRJNA431818) from 13 tissues (brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, muscle, skin, spleen, stomach, blood, cecum, epididymis, and testis) of adult domestic donkeys were downloaded from the SRA database on the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Quality control was performed using FastQC (v0.11.8; http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)) followed by alignment to the donkey genome (ASM1607732v2) via HISAT2 (v2.1.0, Center for Computational Biology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA). Transcripts were assembled using StringTie, and gene expression abundance (FPKM) was estimated. Finally, the HeatMap function in TBtools-II was used to construct an expression heatmap of HOX family genes across different donkey tissues.

5. Conclusions

In this study, 33 HOX gene family members were identified in the donkey genome and were characterized by their chromosomal distribution, physicochemical properties, and structural features. All HOX proteins were predicted to localize to the nucleus and contained highly conserved motifs, consistent with their function as transcription factors. Phylogenetic analysis classified these genes into eight subfamilies, with strong conservation of orthologous relationships across mammalian species. Collinearity analysis revealed high synteny between donkey and horse HOX clusters, indicating close evolutionary relationships between equid species. Ka/Ks analysis confirmed that purifying selection maintains functional constraint across all HOX family members.

Functional enrichment analysis demonstrated significant roles in anterior–posterior patterning, skeletal morphogenesis, and transcriptional regulation, consistent with established HOX functions in developmental processes. Tissue expression profiling revealed distinct spatial patterns, with tissue-specific expression of particular HOX providing essential genomic resources for future research on donkey HOX genes and their roles in economically important traits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010038/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., M.Z.K., C.W. and Y.P.; methodology, X.L., M.Z.K., C.W. and Y.P.; software, X.L., M.Z.K., C.W. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., M.Z.K., C.W. and Y.P.; writing—review and editing, X.L., A.L., M.Z.K., Q.Z., Y.Z., W.C., B.C., Z.Y., Y.P. and C.W.; supervision, M.Z.K., C.W. and Y.P.; project administration, C.W.; funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, (grant no. 2025LZGC033), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no. ZR2024MC213), Horizontal Scientific Research Project of Liaocheng University (grant no. K25LD167), and Liaocheng University scientific research fund (grant no. 318052339), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2022YFD1600103), Liaocheng Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology, High-talented Foreign Expert Introduction Program (grant no. GDWZ202401), The Shandong Province Modern Agricultural Technology System Donkey Industrial Innovation Team (grant no. SDAIT-27), Livestock and Poultry Breeding Industry Project of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (grant no. 19211162), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31671287), The Open Project of Liaocheng University Animal Husbandry Discipline (grant no. 319312101-14), The Open Project of Shandong Collaborative Innovation Center for Donkey Industry Technology (grant no. 3193308), Research on Donkey Pregnancy Improvement (grant no. K20LC0901), and Liaocheng University scientific research fund (grant no. 318052025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mallo, M.; Alonso, C.R. The regulation of Hox gene expression during animal development. Development 2013, 140, 3951–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallo, M.; Wellik, D.M.; Deschamps, J. Hox genes and regional patterning of the vertebrate body plan. Dev. Biol. 2010, 344, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, K.A.; Wellik, D.M. Hox genes in development and beyond. Development 2023, 150, dev192476, Erratum in Development 2024, 151, dev202770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.P.; Krumlauf, R. Diversification and functional evolution of HOX proteins. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 798812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbellay, F.; Bochaton, C.; Lopez-Delisle, L.; Mascrez, B.; Tschopp, P.; Delpretti, S.; Zakany, J.; Duboule, D. The constrained architecture of mammalian Hox gene clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13424–13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, S.J. Seeking Sense in the Hox Gene Cluster. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, E.; Fromental-Ramain, C.; de Graaff, W.; Le Mouellic, H.; Brûlet, P.; Chambon, P.; Deschamps, J. Axial skeletal patterning in mice lacking all paralogous group 8 Hox genes. Development 2001, 128, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellik, D.M.; Capecchi, M.R. Hox10 and Hox11 Genes Are Required to Globally Pattern the Mammalian Skeleton. Science 2003, 301, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, G.S.; Kovàcs, E.N.; Behringer, R.R.; Featherstone, M.S. Mutations in Paralogous Hox Genes Result in Overlapping Homeotic Transformations of the Axial Skeleton: Evidence for Unique and Redundant Function. Dev. Biol. 1995, 169, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mcintyre, D.C.; Rakshit, S.; Yallowitz, A.R.; Loken, L.; Jeannotte, L.; Capecchi, M.R.; Wellik, D.M. Hox patterning of the vertebrate rib cage. Development 2007, 134, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. Factors affecting the quality and nutritional value of donkey meat: A comprehensive review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1460859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, H. Species-specific identification of donkey-hide gelatin and its adulterants using marker peptides. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e273021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, Q.; Wang, T.; Chai, W.; Zhan, Y.; Akhtar, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, C. Multi-Thoracolumbar Variations and NR6A1 Gene Polymorphisms Potentially Associated with Body Size and Carcass Traits of Dezhou Donkey. Animals 2022, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wu, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the Polycomb Group Family in Medicago truncatula. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.W.; Han, M.V.; Han, S. Gene Family Evolution across 12 Drosophila Genomes. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramov, A.V.; Ermakova, G.V.; Kuchryavyy, A.V.; Zaraisky, A.G. Genome duplications as the basis of vertebrates’ evolutionary success. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 2021, 52, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aase-Remedios, M.E.; Ferrier, D.E.K. Improved understanding of the role of gene and genome duplications in chordate evolution with new genome and transcriptome sequences. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 703163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegg, S.; Meyer, A. Hox clusters as models for vertebrate genome evolution. Trends Genet. 2005, 21, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Khan, A.; Hashem, A.; Abd Allah, E.F.; Al-Harrasi, A. The molecular mass and isoelectric point of plant proteomes. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, S.; Sur, K.; Dasgupta, S. Characterization of the nonregular regions of proteins by a contortion index. Biopolymers 2005, 79, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uversky, V.N. The Mysterious Unfoldome: Structureless, Underappreciated, Yet Vital Part of Any Given Proteome. BioMed Res. Int. 2010, 2010, 568068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadhouders, R.; Filion, G.J.; Graf, T. Transcription factors and 3D genome conformation in cell-fate decisions. Nature 2019, 569, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, D.M. Transcription factors and DNA play hide and seek. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, H.; Katagiri, S.; Kanamori, H.; Mukai, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Wu, J. Evolutionary dynamics and impacts of chromosome regions carrying R-gene clusters in rice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Luthe, D. Identification and evolution analysis of the JAZ gene family in maize. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannan, E.O.; Hartley, G.A.; O’Neill, R.J. Mechanisms of Rapid Karyotype Evolution in Mammals. Genes 2024, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Pineault, K.M.; Dones, J.M.; Raines, R.T.; Wellik, D.M. Hox genes maintain critical roles in the adult skeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7296–7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liang, H.; Kou, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Association of HOXC8 Genetic Polymorphisms with Multi-Vertebral Number and Carcass Weight in Dezhou Donkey. Genes 2022, 13, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.S.; Le Boiteux, E.; Arnaud, P.; Costa, B.M. HOX gene cluster (de)regulation in brain: From neurodevelopment to malignant glial tumours. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 3797–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Li, X. Current Epigenetic Insights in Kidney Development. Genes 2021, 12, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, F. HOXgenes in the skin. Chin. Med. J. 2010, 123, 2607–2612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Awgulewitsch, A. Hox in hair growth and development. Sci. Nat. 2003, 90, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y.; Khan, M.Z.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Kou, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Elucidating the Role of Transcriptomic Networks and DNA Methylation in Collagen Deposition of Dezhou Donkey Skin. Animals 2024, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliacikova, G.; Maurel-Zaffran, C.; Graba, Y.; Saurin, A.J. Hox Proteins in the Regulation of Muscle Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 731996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Suo, P.; Wang, J.; Cheng, L.; Cheng, Z.; Jia, J.; Kan, S.; Wang, B.; et al. Association analysis between HOXD9 genes and the development of developmental dysplasia of the hip in Chinese female Han population. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.L.; Boler, D.D.; Kutzler, L.W.; Jones, K.A.; McKeith, F.K.; Killefer, J.; Carr, T.R.; Dilger, A.C. Muscle gene expression associated with increased marbling in beef cattle. Anim. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Prendes, R.; Quintanilla, R.; Mármol-Sánchez, E.; Pena, R.N.; Ballester, M.; Cardoso, T.F.; Manunza, A.; Casellas, J.; Cánovas, Á.; Díaz, I.; et al. Comparing the mRNA expression profile and the genetic determinism of intramuscular fat traits in the porcine gluteus medius and longissimus dorsi muscles. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbach, N.A.; Rozenfeld, S.; Shen, W.; Fong, S.; Chrobak, D.; Ginzinger, D.; Kogan, S.C.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Le Beau, M.M.; Largman, C.; et al. HOXB6 overexpression in murine bone marrow immortalizes a myelomonocytic precursor in vitro and causes hematopoietic stem cell expansion and acute myeloid leukemia in vivo. Blood 2005, 105, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, D.; Shen, X.; Ouyang, H.; Li, W.; Xu, D.; Fang, L.; Tian, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals candidate genes for seasonal breeding in the male Lion-Head goose. Br. Poult. Sci. 2023, 64, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloğlu, U.; Akbalik, M.E.; Sağsöz, H. Immunolocalization of some HOX proteins in immature and mature feline testes. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2021, 50, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomgardner, D.; Hinton, B.T.; Turner, T.T. Hox Transcription Factors May Play a Role in Regulating Segmental Function of the Adult Epididymis. J. Androl. 2001, 22, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandeville, I.; Aubin, J.; Leblanc, M.; Lalancette-Hébert, M.; Janelle, M.; Tremblay, G.M.; Jeannotte, L. Impact of the Loss of Hoxa5 Function on Lung Alveogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 1312–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.