Abstract

Jasmonate-ZIM domain (JAZ) proteins act as repressors in the jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway and also function as plant-specific proteins participating in plant growth and development, stress response, and defense. In our study, a total of 25 JAZ genes were identified in B. rapa based on their conserved domains. First, the primary characteristics were surveyed, including the lengths of the CDS and proteins, molecular weights, and isoelectric points. Next, a phylogenetic tree of JAZ proteins among B. rapa, A. thaliana, O. sativa, B. oleracea, and B. napus was constructed, which revealed that these proteins cluster into four groups based on sequence homology rather than by species. Synteny analysis of JAZ genes among these species demonstrated that the highest number of collinear pairs was found between B. rapa and B. napus. Most BrJAZ genes were highly expressed in root, stem, and leaf. Moreover, the expression levels of BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were induced by drought, high salt, black rot, and MeJA. Over-expressed these genes in A. thaliana lines enhanced their tolerance to drought and high salt stress, which was associated with higher enzymatic activities of SOD and POD. Both BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP were localized in the nucleus.

1. Introduction

The JAZ gene family represents a subgroup of the TIFY transcription factors and is defined by two highly conserved domains: the ZIM domain, which facilitates protein–protein interactions, and the Jas domain, which plays a critical role in jasmonic acid (JA) signal transduction [1]. JAZ proteins act as central repressors in the JA signaling pathway by interacting with transcription factors such as MYC, thereby modulating the expression of downstream genes [2]. Through this regulatory mechanism, JAZ proteins exert significant influence on plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stimuli.

JA signaling also works in combination with multiple hormones in plant responses to abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, and low temperature [3]. Accumulating evidence across various plant species demonstrates that JAZ proteins contribute to stress adaptations by integrating with particularly abscisic acid (ABA). For instance, JAZ1 has been reported to act as a positive regulator in seed germination in bread wheat by directly interacted with TaABI5, leading the repression of the ABA pathways [4]. Furthermore, JAZ1, JAZ6, and JAZ9 were rapidly induced by drought and salt stress in Oryza sativa [5]; moreover, OsJAZ9 enhanced its tolerance to potassium deficiency, while its knockdown lines were sensitive [6]. On the other hand, JAZ1 was induced at 3 h of drought stress in sugarcane. Furthermore, its over-expressed transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana lines promoted the flowering time to be shorter than Col-0 [7]. JAZ25 acts as a negative regulator in gray leaf spot resistance by directly binding on the SlMYC2 promoter in Solanum lycopersicum [8]. In cruciferous plants, there were not only the 13 JAZ family members identified in A. thaliana in response to biotic and abiotic stress responses [9], but also the genome-wide identification and functional analyses of JAZ members in turnip (Brassica rapa), Brassica napus, have been carried out [10,11,12]. These studies in A. thaliana showed that JAZ8 acts as a negative regulator against Botrytis cinerea infection [13], and JAZ7 promoted drought tolerance [14], while JAZ1 and JAZ4 play negative roles in freezing stress [15].

B. rapa is famous for its high nutritional value and low price with widespread cultivation in East Asia and suffers various abiotic and biotic stresses in field, such as drought, salinity, low temperature, and bacterial diseases, leading losses of crop yield and quality [16]. It is reported that JAZ genes play roles in both abiotic and biotic stresses; however, there were scarcely any reports of the JAZ family in B. rapa. In our study, 25 JAZ genes of Chinese cabbage were identified and analyzed, such as chromosomal locations, promoter cis-elements, the protein motifs, gene structures, molecular weights, and isoelectric points. To investigate the evolutionary relationships of the JAZ members among multiple species, a phylogenetic tree of JAZ proteins was built among B. rapa, A. thaliana, O. sativa, B. oleracea, and B. napus. Furthermore, synteny analysis of JAZ genes among B. rapa and the other species was conducted to demonstrate their duplication events. The expression levels of BrJAZs in different tissues and various treatments, including drought, salinity, black rot infection, and MeJA, were further detected by qPCR. To identify the function of BrJAZ in B. rapa, BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were selected and overexpressed in A. thaliana for drought and high salt treatments.

2. Results

2.1. The Isolation and Identification of the JAZ Family Genes in B. rapa

- A total of 31 candidate JAZ family members were initially identified in B. rapa via annotation and homology searches in the BRAD database. The presence of the characteristic ZIM domain in these candidate proteins was then validated using the InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/, accessed on 20 February 2025), SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/, accessed on 20 February 2025), and ScanProsite (https://prosite.expasy.org/, accessed on 20 February 2025) tools. This analysis confirmed that only 25 genes contained a typical TIFY domain, and these were retained for further study. Based on their homology to A. thaliana JAZ genes, these 25 genes were designated as BrJAZ1 to BrJAZ12 (Table S1). Notably, no homologous genes for AtJAZ11 and AtJAZ12 were found in the Chinese cabbage genome. The key characteristics of the 25 BrJAZ genes are summarized in Table 1. The CDS lengths ranged from 342 bp to 1071 bp, while the genomic sequences were considerably longer (501 bp to 3273 bp), a difference attributable to the variation in intron number and size of the introns. The encoded proteins ranged from 113 to 356 amino acids in length, with molecular weights between approximately 13.0 kDa and 39.8 kDa. The theoretical isoelectric points (pI) of most BrJAZ proteins were basic, ranging from 7.9 to 10.07, except for BrJAZ12a, which had an acidic pI of 4.97.

Table 1. The information about the BrJAZ members.

Table 1. The information about the BrJAZ members.

2.2. Phylogenetic Relationships and Synteny of JAZ Members Among B. rapa, A. thaliana, B. napus, and B. oleracea

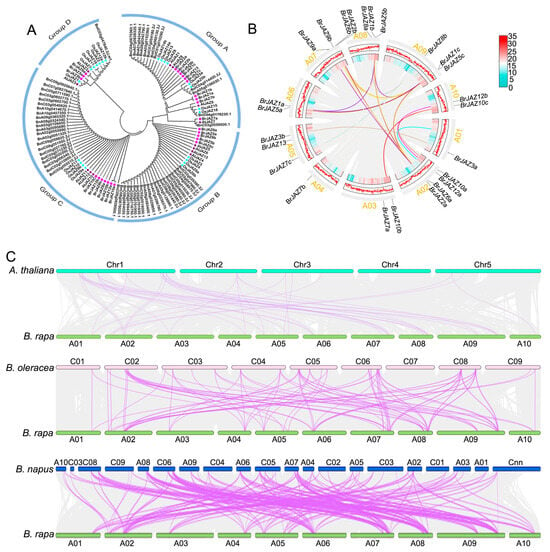

Firstly, the phylogenetic analysis of 121 JAZ proteins derived from B. rapa, A. thaliana, B. napus, B. oleracea, and O. sativa was conducted by the maximum likelihood method including 13 AtJAZs, 23 OsJAZs, 25 BraJAZs, 21 BolJAZs, and 38 BnJAZs. These proteins were classified into four major subgroups, designated Group A to D (Figure 1A). Group C was the largest with 37 members, which were clustered by species rather than orthology. In contrast, Group D is the smallest, including 13 members and clustering based on gene homology, such as JAZ members of B. rapa and A. thaliana grouping together.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic and collinearity analysis of JAZ family members. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of JAZ proteins among B. rapa, A. thaliana, B. oleracea, and B. napus. (B) Collinearity analysis of BrJAZ genes within the B. rapa genome. (C) Synteny analysis of JAZ genes between B. rapa and three related species (A. thaliana, B. oleracea, and B. napus).

Collinearity analysis of the BrJAZ genes revealed 33 collinear pairs (Figure 1B) listed in Table S2. Furthermore, synteny analysis of JAZ members between B. rapa and A. thaliana, O. sativa, B. oleracea, and B. napus was performed (Figure 1C, Table S3). Numerous collinear pairs were detected between B. rapa and other cruciferous species: 39 pairs with A. thaliana, 91 pairs with B. oleracea, and 154 pairs with B. napus (Table S3). In contrast, no collinear pairs were identified between B. rapa and O. sativa (Figure S1).

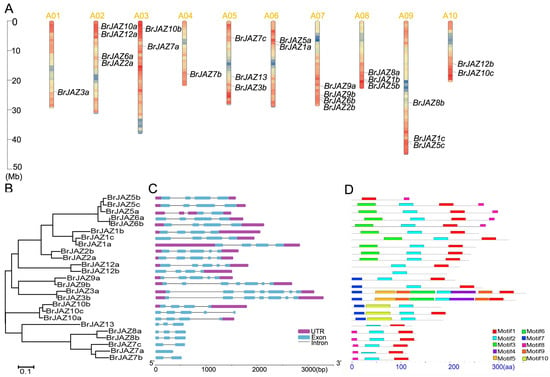

2.3. The Gene Localization, Structures, and Conserved Motifs of BrJAZ Members

The 25 BrJAZ genes were distributed unevenly across all ten chromosomes of B. rapa. Chromosomes A02 and A07 each contained four genes, whereas only one gene each was located on A01 (BrJAZ3a) and A04 (BrJAZ7b). Three chromosomes (A05, A08, and A09) harbored three BrJAZ genes each, and the remaining chromosomes each contained two members (Figure 2A). These results suggested the occurrence of both tandem and segmental duplications in the BrJAZ gene family. A phylogenetic tree of the 25 BrJAZ proteins was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method, clustering them into three major groups (Figure 2B). In addition, ten conserved motifs were identified in the BrJAZ proteins (Figure 2D) with the sequence logos presented in Figure S2. The most conserved motif, Motif 2, presented in 24 members, following by Motif 1 in 21 proteins (Figure 2D). The exon–intron structures of the BrJAZ genes are shown in Figure 2C. Nearly half of the genes contain four exons, and members within the same phylogenetic subgroup exhibit similar gene structures.

Figure 2.

Chromosomal localization, phylogenetic tree, exon–intron structure, and conserved motifs of BrJAZ genes. (A) Chromosomal distribution of BrJAZ genes in B. rapa. (B) Phylogenetic tree of BrJAZ proteins. (C) Exon–intron structure of BrJAZ genes. (D) Conserved motifs in BrJAZ proteins.

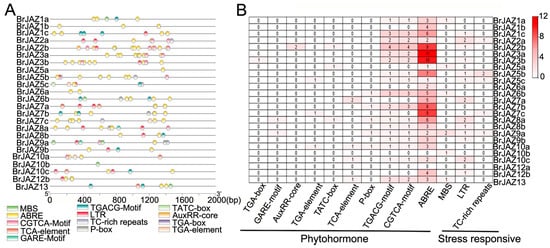

2.4. The Cis-Acting Elements on the BrJAZ Promoters

The 2000 bp promoter sequences upstream of the start codon of each BrJAZ gene were retrieved for cis-element analysis (Figure 3). Hormone-responsive elements were identified in most BrJAZ promoters, except for BrJAZ10b and BrJAZ12a. Notably, the MeJA-responsive motifs TGACG and CGTCA were present in 18 BrJAZ promoters, suggesting these genes are involved in the JA signaling pathway. The most abundant elements were ABREs, associated with abscisic acid responsiveness, with 109 copies distributed across 23 BrJAZ promoters. several stress-related cis-elements were detected, including MBS (drought stress), LTR (low-temperature stress), and TC-rich repeats (general stress response) (Figure 3A,B). These results revealed that BrJAZ genes are involved in hormone responses and stress responses.

Figure 3.

Cis-acting elements related to abiotic stress in BrJAZ promoters. (A) Distribution of cis-acting elements related to abiotic stress. (B) Number of each cis-acting element.

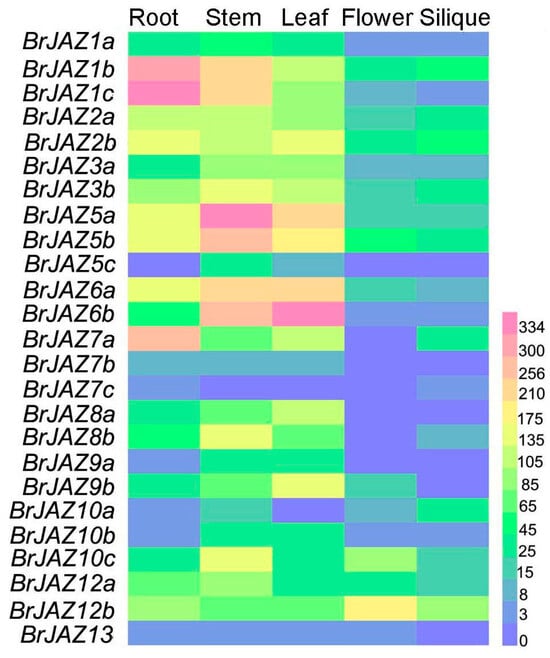

2.5. The Expression Levels of BrJAZs in Different Tissues and in Response to Stresses

The expression levels of BrJAZ genes in different tissues (root, stem, leaf, flower, and silique) were analyzed using transcriptome data of Chinese cabbage from the BRAD database. Most BrJAZ genes exhibited relatively high expressions in root, stem, and leaf (Figure 4). BrJAZ5a, BrJAZ5b, BrJAZ6a, and BrJAZ6b were markedly induced in root and leaf, whereas BrJAZ1b and BrJAZ1c showed high transcript levels in root, stem, and leaf. In contrast, the expression levels of BrJAZ7b, BrJAZ7c, and BrJAZ13 were low across each tissue (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The expression patterns of BrJAZ members in in root, stem, leaf, flower, and silique.

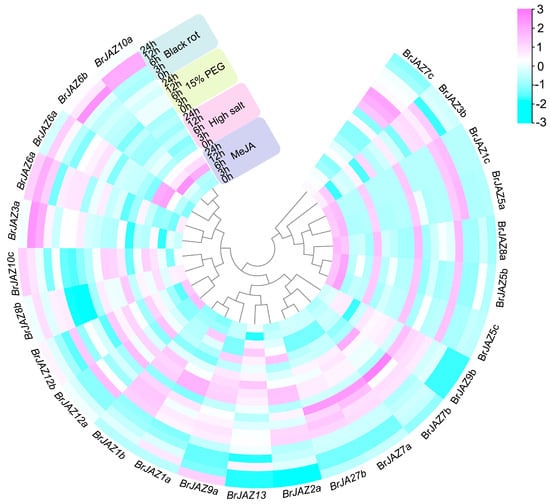

2.6. The Transcriptional Levels of BrJAZs in Response to Stresses

The transcriptional levels of BrJAZ genes in B. rapa under drought and high-salt stresses were further detected by qPCR at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours post-treatment (Figure 5). Under drought stress, nine members (BrJAZ1a, BrJAZ1b, BrJAZ2a, BrJAZ2b, BrJAZ6a, BrJAZ7a, BrJAZ7b, BrJAZ9a, and BrJAZ9b) were markedly induced, with peak expression levels generally observed at 3 h and 6 h. Among them, BrJAZ1a, BrJAZ1b, BrJAZ7a, and BrJAZ7b maintained notably high expression from 3 h to 24 h (Figure 5). Under high-salt stress, BrJAZ1a, BrJAZ1b, BrJAZ2a, and BrJAZ9a were strongly induced at 24 h, whereas BrJAZ2b was up-regulated at the earlier time points of 3 h and 6 h (Figure 5). Furthermore, the expression of BrJAZ1a, BrJAZ6a, BrJAZ6b, BrJAZ10a, and BrJAZ10b was significantly enhanced by both MeJA treatment and black rot pathogen infection. In contrast, BrJAZ2a and BrJAZ9a were induced specifically by MeJA at 24 h, and BrJAZ3a was specifically up-regulated in response to black rot infection (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

qPCR analysis of BrJAZ gene expression in response to drought, salt stress, black rot infection, and MeJA treatment at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h.

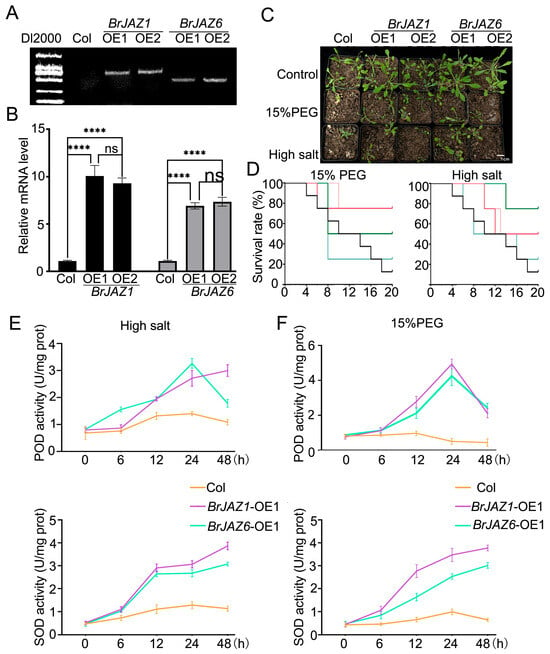

2.7. The Phenotypic Characteristics of Over-Expressed BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b Transgenic A. thaliana Lines Under Abiotic Stresses

BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were over-expressed in A. thaliana Col-0 by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Two independent transgenic lines for each gene were obtained through hygromycin selection and confirmed by PCR using gene-specific primers (Figure 6A; Table S4). The expression levels of BrJAZ1a in the OE1 and OE2 lines were up to 10.077- and 9.293-fold higher than in Col-0, respectively, while BrJAZ6b expression was up to 6.927- and 7.350-fold higher (Figure 6B). The transgenic lines and Col-0 were subjected to drought and high-salt treatments. The survival rates of the transgenic lines were higher than Col-0. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) were measured in these lines under drought and salt stress at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h (Figure 6D,E). Under drought stress, POD activities of the BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b overexpression lines were induced, peaked at 24 h and then declined at 48 h, remaining higher than in Col-0. Under salt stress, POD activities of the BrJAZ6b lines showed a similar trend, whereas in the BrJAZ1a lines, they increased continuously throughout the treatment. SOD activities increased continuously following both stress treatments; moreover, these of the overexpression lines had significantly higher activity than Col-0 (Figure 6D,E).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic and physiological analyses of BrJAZ1a- and BrJAZ6b-overexpressing A. thaliana lines under abiotic stress. (A) PCR confirmation of transgenic BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b overexpression lines. (B) Expression levels of BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b in transgenic lines by qPCR. (C) Phenotype of wild-type (Col-0) and transgenic lines under drought (15% PEG) and salt (200 mM NaCl) stress. (D) Survival rates of the indicated lines under drought and salt stress over time. (E) POD and SOD activities in wild-type and transgenic lines under salt stress. (F) POD and SOD activities in wild-type and transgenic lines under drought stress. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons tests (**** p < 0.0001; ns, not significant).

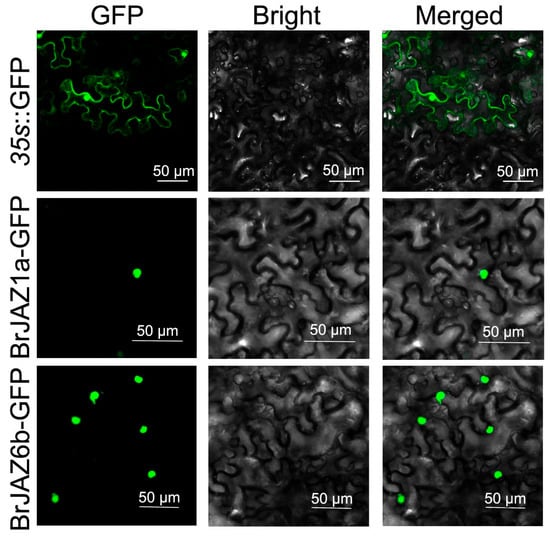

2.8. The Subcellular Localization of BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP

To determine the subcellular localization of BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b, BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP fusion constructs were generated and transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves. Fluorescence signals were observed using confocal microscopy. The 35s::GFP exhibited the green fluorescence in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and membrane. In contrast, both BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP were specifically localized in the nucleus, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The subcellular localization of BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP in N. benthamiana.

3. Discussion

Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins are central repressors of JA signaling and play critical roles in plant growth, development, and stress responses. Increasing evidence indicates that JAZ-mediated regulations are pivotal for plant adaptation to both abiotic and biotic stresses, including drought, salinity, and pathogen infection. B. rapa, an important leafy vegetable crop, is frequently exposed to multiple environmental stresses throughout its growth cycle, which significantly constrain yield and quality [17]. Extensive studies of JAZ genes in Arabidopsis and other Brassica species were identified; however, a systematic investigation of the JAZ gene family in B. rapa has been lacking. In this study, 25 JAZ family members were identified in B. rapa with the main information listed in Table 1, including the length of CDS and protein, exon number, molecular weight, and isoelectric point. Next the protein phylogenetic tree and motifs of BrJAZs exhibit that the motifs of the same clustered groups were similar. Furthermore Motif 1 (ZIM domain) and Motif 2 (Jas domain) are the most conserved, presenting in nearly every member, while other motifs vary in number and arrangements (Figure 2D). Similar conserved motifs of the JAZ families have been reported in Arabidopsis, B. oleracea, and B. napu [12,18,19,20], indicating that core JAZ functions are evolutionarily conserved across Brassicaceae species. It has been reported that the JAZ family has 13 members in A. thaliana [18], while there were 15 members in rice [20] and 26 and 56 members in B. oleracea [12] and B. napus [19], respectively, suggesting that gene duplication has driven the expansion and diversification of the JAZ family in Chinese cabbage. Therefore, we built the evolutionary relationships of JAZ members among these species, they were clustered together based on gene homology rather than species-specific relationships, indicating that the JAZ genes are conserved in different species. Synteny revealed abundant collinearity pairs of JAZ genes between B. rapa and other species but none were found in rice, reflecting the evolutionary divergence between dicots and monocots.

The promoters of most BrJAZ genes harbored multiple hormone- and stress-related elements, including ABRE (ABA-responsive), MBS (drought-responsive), and CGTCA/TGACG motifs (MeJA-responsive). Notably, ABRE elements—known mediators of ABA-dependent stress responses [21]—were present in nearly all BrJAZ promoters, implying potential crosstalk between ABA and JA signaling. The widespread occurrence of MeJA-responsive elements further supports the role of BrJAZs in JA-mediated defense, which is consistent with reports in other Brassica species [10,22,23].

The expression levels of BrJAZ genes were further monitored in various responses including drought, high salinity, MeJA treatment, and black rot infection. Ten BrJAZ genes were significantly induced by drought stress, while nine members were increased under high salinity. The expressions of six BrJAZs were markedly induced by exogenous MeJA, while BrJAZ1a/1b, BrJAZ3a, BrJAZ6a/6b, and BrJAZ10 were significantly upregulated by black rot stresses. It has been reported that the expression levels of JAZ genes were up-regulated under multiple stresses in turnip, rapeseed, and Brassica juncea [10,23,24], which aligns with our study; together with the results in our study, this suggests a conserved mechanism. Notably, BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were strongly induced in each treatment, indicated that BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b might play central roles in the broad stress adaptation in B. rapa. Therefore, BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were highly over-expressed in Arabidopsis, which showed that they enhanced the drought and salt tolerance of their over-expressed transgenic lines compared to Col-0, with the increased activities of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD and POD). It has been reported that JAZ1 and JAZ6 play roles in the stress responses of many species, such as TaJAZ1 promoting the seed germination in bread wheat [4]; OsJAZ1 and OsJAZ6 were rapidly induced by drought and salt stress in O. sativa [5]; and overexpressing GaJAZ1 increased tolerance to salt stress in G. hirsutum [25]. Furthermore research findings on the mechanism of JAZ’s involvement in abiotic stress as core repressors of jasmonic acid (JA) signaling revealed that jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins directly interact with MYC transcription factors to modulate JA-responsive gene expression [26,27] Under normal conditions, JAZ proteins inhibit MYC activity; however, stress-induced JA accumulation triggers JAZ degradation via the SCFCOI1 complex, thereby releasing MYC to activate defense pathways in Arabidopsis [28,29]. Notably, specific JAZ members are known to fine-tune—rather than simply repress—JA signaling, enabling an adaptive responses to abiotic stress [30]. Our study provides that BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b are located in the nucleus and play positive roles in drought and salt stresses in Arabidopsis; however, the molecular mechanisms were not explored. Collectively, our findings offer valuable genetic resources and theoretical framework for breeding stress-resilient Brassica crops.

Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study provides a comprehensive genomic and functional characterization of the JAZ gene family in B. rapa, identifying BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b as positive regulators of drought and salt tolerance. However, since the genetic transformation system of Chinese cabbage has not obtained transgenic plants in B. rapa and only subcellular localization experiments were conducted, definitive conclusion cannot be drawn without further exploring how BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b are involved in non-biological molecular mechanisms. In future studies, the functions and underlying mechanisms of these two genes will be investigated in depth.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

Seeds of the Chinese cabbage inbred line and A. thaliana ecotype Col-0 were obtained from the Chinese Cabbage Research Laboratory, College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Northeast Agricultural University. Chinese cabbage plants were cultivated in a greenhouse under a 16-h light (light intensity: 200 µmol m−2 s−1, temperature: 25 °C)/8-h dark (temperature: 20 °C) photoperiod. The relative humidity was controlled at 60–70%, and the growth substrate was a mixed medium of peat moss:vermiculite:perlite at a volume ratio of 3:1:1. Upon reaching the five-leaf stage, some of the plants were subjected to treatment with 100 µM ABA (foliar spray), 100 µM MeJA (foliar spray), 15% PEG 8000 (root irrigation), or 200 mM NaCl (root irrigation). Tissue samples were collected at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-treatment, with three biological replicates for each time point. Each biological replicate consisted of tissue pooled from one individually grown plant. All collected plant materials were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The remaining plants were vernalized (temperature: 4 °C) for 21 days, and then returned to the greenhouse until the flowering stage. Subsequently, various tissues, including roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and siliques, were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

4.2. Phylogenetic Tree and Collinearity Analysis

The genomic DNA and protein sequences of JAZ family members from A. thaliana and cruciferous vegetables were retrieved from the TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and BRAD (http://www.brassicadb.cn/) databases. Multiple sequence alignment of the full-length JAZ proteins was performed using MEGA11. A phylogenetic tree was constructed via the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method, with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess branch node support [31]. For synteny and duplication analysis, whole-genome protein sequences of the selected species were analyzed using TBtools v2.388 [32], which integrates the MCScanX algorithm [33]. Homologous gene pairs were first identified by BLASTP (E-value < 1 × 10−5). MCScanX was then employed to detect syntenic blocks within and across genomes. JAZ gene pairs located within these conserved collinear blocks were classified as segmental duplications. Tandem duplication events were identified based on genomic proximity. Genes from the same phylogenetic subgroup were considered tandemly duplicated if two or more were located within a 100-kb genomic region on the same chromosome, with no more than one non-JAZ gene intervening.

4.3. Gene Location, Structure, and Protein Motifs

The chromosomal locations of BrJAZ genes were obtained from the BRAD database and visualized using TBtools. The gene structures (intron/exon organization) were determined by submitting the CDS and corresponding genomic sequences of the BrJAZ genes to the online tool GSDS 2.0 (https://gsds.gao-lab.org/). Furthermore, the conserved motifs within the BrJAZ proteins were identified using the MEME Suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/, accessed on 23 February 2025). The search parameters were set to a maximum of 10 motifs and “Zero or One Occurrence Per Sequence(zoops)” was selected. The motif sequences and motif logos are presented in Table S5 and Figure S2, respectively.

4.4. Total RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from plant samples using the FreeZol Reagent kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Subsequently, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript III RT SuperMix kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The qPCR reactions were performed in a 15 µL volume, which consisted of 7.5 µL ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme), 0.5 µL of each forward and reverse primer, 3 µL of diluted cDNA template, and 3.5 µL of ddH2O. All reactions were run on the qTOWER2.0 system (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). The qPCR cycling consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s. A melt curve analysis was subsequently carried out by heating from 65 °C to 95 °C, with continuous fluorescence measurement to verify amplification specificity. BrACTIN was used as the reference gene for normalization, and all primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

4.5. Gene Clone and Vector Constructions

BrJAZ1a and BrJAZ6b were amplified from a Chinese cabbage inbred line cDNA using gene-specific primers (listed in Table S4). The resulting PCR products were then inserted into the plant expression vector pCambia1302 using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China; Catalog No.: C112-02).

4.6. Plant Transformations

The recombinant plasmids were first introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 via electroporation. These transformed agrobacteria were then used to infect A. thaliana plants via the floral dip method [34]. Transgenic seeds were surface-sterilized and sown on 1/2 MS medium containing 20 mg/L hygromycin for selection. After one week, resistant seedlings were transplanted into a 1:1 mixture of vermiculite and soil and grown in a controlled greenhouse under a 16-h light (22 °C)/8-h dark (19 °C) cycle. Putative transgenic plants were confirmed by both PCR and qPCR analyses using the primers listed in Tables S6 and S4. For stress treatments, T3 generation transgenic seedlings were grown to the five-leaf stage and then subjected to either high salt (200 mM NaCl, root irrigation) for 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h for enzymatic assays or to drought stress simulated by 15% PEG6000 for three weeks for phenotypic observation. During cultivation, seedlings were manually watered (root irrigation). All treatments at each time point were conducted with three biological replicates. For all expression and physiological assays, biological replicates refer to samples collected from independent plants grown under identical conditions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and enzyme activity data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 10 software and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate multiple comparisons tests. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For subcellular localization, the fusion constructs (BrJAZ1a-GFP and BrJAZ6b-GFP) were transiently expressed in tobacco leaves via agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. GFP signals were observed using a confocal microscope 72 h after infiltration.

4.7. Enzyme Activities

For the measurements of SOD and POD enzyme activities, 0.5 g of A. thaliana tissue from each treatment was harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a powder. The total protein content of each sample was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Boxbio, Beijing, China) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The value was used to normalize the subsequent enzyme activity results, which were determined using specific commercial assay kits (Boxbio, Beijing, China) and are expressed as units per milligram of protein.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010289/s1.

Author Contributions

C.L. for experiments and data curation; Q.F. and C.L. for writing—original draft, X.W. for data analysis; K.L. and Z.L. for conceptualization and resources; Y.Z. (Yan Zhang) and Y.Z. (Yaowei Zhang) for supervision; and Y.L. for funding acquisition, writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32202483.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due Laboratory Requirements but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, Y.; Meng, Y.; Huang, D.; Qi, Y.; Chen, M. Origin and evolutionary analysis of the plant-specific TIFY transcription factor family. Genomics 2011, 98, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, L.; Goossens, A. The JAZ proteins: A crucial interface in the jasmonate signaling cascade. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3089–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Meng, Y.; Hu, J.; Ding, M.; Bian, J.; Yan, M.; Han, J.; Zhou, M. Jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling coordinates hydroxycinnamic acid amides biosynthesis through ORA59 transcription factor. Plant J. 2018, 95, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Jing, Y.; Shi, P.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Yan, J.; Chu, J.; Chen, K.M.; Sun, J. JAZ proteins modulate seed germination through interaction with ABI5 in bread wheat and Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Du, H.; Tang, N.; Li, X.; Xiong, L. Identification and expression profiling analysis of TIFY family genes involved in stress and phytohormone responses in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Pandey, B.K.; Mehra, P.; Heitz, T.; Giri, J. OsJAZ9 overexpression modulates jasmonic acid biosynthesis and potassium deficiency responses in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.L.; Zhang, J.X.; Jiang, S.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.S.; Dong, X.M.; Hu, Q.; Yao, W.; Zhang, M.Q.; Xiao, S.H. Genome-wide identification of JAZ gene family in sugarcane and function analysis of ScJAZ1/2 in drought stress response and flowering regulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, H. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Expression Analysis of the JAZ Gene Family in Resistance to Gray Leaf Spots in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, H.; Cao, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Su, Z. Chromatin state analysis for regulatory features of JAZ family genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, K.; Yan, C.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, W.; Yan, H.; Gao, J. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the JAZ gene family in turnip. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zheng, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, B.; Li, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the JAZ Gene Family in Rapeseed Reveal JAZ2 and JAZ3 Roles in Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 20955–20971, Correction in J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 25689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lv, H. Genome-Wide Identification, Expression Profile of the TIFY Gene Family in Brassica oleracea var. capitata, and Their Divergent Response to Various Pathogen Infections and Phytohormone Treatments. Genes 2020, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, D. The transcription factor WRKY75 positively regulates jasmonate-mediated plant defense to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1473–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, T.; Geng, S.; Scott, P.B.; Li, H.; Chen, S. Comparative proteomics and metabolomics of JAZ7-mediated drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Proteom. 2019, 196, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, F.; Yu, D. Jasmonate regulates the inducer of cbf expression-C-repeat binding factor/DRE binding factor1 cascade and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2907–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shen, Y.; Yang, W.; Pan, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, L. Comparative Metabolic Study of Two Contrasting Chinese Cabbage Genotypes under Mild and Severe Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, I.; Mlinarić, S.; Tarkowská, D.; Oklestkova, J.; Novák, O.; Lepeduš, H.; Bok, V.V.; Brkanac, S.R.; Strnad, M.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Early Brassica Crops Responses to Salinity Stress: A Comparative Analysis Between Chinese Cabbage, White Cabbage, and Kale. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thireault, C.; Shyu, C.; Yoshida, Y.; St Aubin, B.; Campos, M.L.; Howe, G.A. Repression of jasmonate signaling by a non-TIFY JAZ protein in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015, 82, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.R.; Shi, J.; Wang, H. Genome-wide analysis of the JAZ subfamily of transcription factors and functional verification of BnC08.JAZ1-1 in Brassica napus. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Pandey, B.K.; Deveshwar, P.; Narnoliya, L.; Parida, S.K.; Giri, J. JAZ Repressors: Potential Involvement in Nutrients Deficiency Response in Rice and Chickpea. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, J.; Chang, X.; Dong, N.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Zha, L.; Gui, S. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the WRKY gene family reveals abiotic stress response mechanisms in Platycodon grandiflorus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Kang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, W.; Xie, P.; Liao, L.; Huang, L.; Yao, M.; Qian, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of the TIFY gene family in the response to multiple stresses in Brassica napus L. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liao, J.; Wang, D. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of jasmonate ZIM domain gene family in tuber mustard (Brassica juncea var. tumida). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Song, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yao, D.; Li, D.; Qin, W.; Ge, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Su, Z.; et al. Gossypium hirsutum Salt Tolerance Is Enhanced by Overexpression of G. arboreum JAZ1. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thines, B.; Katsir, L.; Melotto, M.; Niu, Y.; Mandaokar, A.; Liu, G.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A.; Browse, J. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF(COI1) complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chini, A.; Fonseca, S.; Fernández, G.; Adie, B.; Chico, J.M.; Lorenzo, O.; García-Casado, G.; López-Vidriero, I.; Lozano, F.M.; Ponce, M.R.; et al. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 2007, 448, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browse, J. Jasmonate passes muster: A receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, L.B.; Tan, X.; Mao, H.; Withers, J.; Ben-Nissan, G.; Hinds, T.R.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hsu, F.F.; Sharon, M.; Browse, J.; et al. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 2010, 468, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.