Abstract

Cervical cancer remains a significant cause of cancer-related mortality among women, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. High-throughput technologies, such as microarrays, have facilitated the comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles in cervical cancer, enabling the identification of key differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in their pathogenesis. The publicly available microarray datasets, including GSE39001, GSE9750, GSE7803, GSE6791, GSE63514, and GSE52903 in combination with bioinformatic database predictions, were used to identify differential expression genes, potential biomarkers, and therapeutic targets for cervical cancer; additionally, we undertook bioinformatic analysis to determine gene ontology and possible miRNA targets related to our DEGS. Our analysis revealed several DEGs significantly associated with cervical cancer progression, such as cell death, regulation of DNA replication, protein binding, processes, and transcription factors. The most relevant transcription factors (TFs) identified were SP1, ELF3, E2F1, TP53, RELA, HDAC, and FOXM1. Importantly, the DEGs with more important changes were 11 coding genes that were upregulated (KIF4A, MCM5, RFC4, PLOD2, MMP12, PRC1, TOP2A, MCM2, RAD51AP1, KIF20A, AIM2) and 14 that were downregulated (CXCL14, KRT1, KRT13, MAL, SPINK5, EMP1, CRISP3, ALOX12, CRNN, SPRR3, PPP1R3C, IVL, CFD, CRCT1), which were associated with cervical cancer. Interestingly, hub proteins KIF4A, NUSAP1, BUB1B, CEP55, DLGAP5, NCAPG, CDK1, MELK, KIF11, and KIF20A were found to be potentially regulated by several miRNAs, including miR-107, miR-124-3p, miR-147a, miR-16-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-34c-5p, miR-126-3p, miR-10b-5p, miR-23b-3p, miR-200b-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-203a-3p, miR-214-3p, and let-7b-5p. The relationship between these genes highlights their potential as candidate biomarkers for further research in treatment, diagnosis, and prognosis.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer ranks as the fourth most common cancer among women globally, with approximately 661,021 new cases and 348,189 deaths reported in 2022, according to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) [1]. Despite improvements in screening and vaccination programs, cervical cancer remains a significant public health challenge, particularly in regions with limited healthcare access. Persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types is the primary driver of cervical cancer, leading to genetic and epigenetic alterations that disrupt normal cellular function and promote malignant transformation [2]. HPV propagation is dependent on the cellular differentiation state and the abundance of important molecules, including transcriptional factors, polymerases, splicing factors, RNA processing machinery, and regulatory elements of RNAs [3]. HPV infection results in the expression of viral proteins that lead to the acquisition of immortal cell features, such as sustained proliferation and differentiation. HPVs, such as HPV16 and HPV18, are associated with oncogenesis and are therefore considered to be “high risk” (HR) viruses. The HR viral E7 oncoprotein interacts with retinoblastoma (Rb) protein family members, releasing the transcriptional factor E2F from Rb regulation, permitting the transition from G1 to S phase [4]. The binding of E2F to the target promoter activates transcription of several genes involved in proliferation [5]. In addition, the HR-HPV E6 protein interacts with p53 and induces its degradation via ubiquitination, resulting in a p53-null phenotype that abrogates apoptosis and cell cycle checkpoints [3,6]. P53 is altered by several stimuli, such as UV exposure, oncogene activation, and replication stress, among several other factors [7,8]. Additionally, it has been reported that HPV integration can induce gene expression misregulation. Besides the misregulation of coding genes by HR-HPV oncoprotein expression, HPV integration is associated with non-coding genes like microRNAs’ (miRNAs) dysregulation [9]. Therefore, cervical cancer is a genetic complex pathology that involves coding gene and non-coding gene abnormalities [10] that are also involved in tumor cell microenvironment modulation [11]. Normal cellular proliferation is regulated by proto-oncogenes and tumor gene suppressors. Mutations that increase proto-oncogene activity convert these genes into oncogenes, leading to tumor cell proliferation. Normally, these genes encode growth factors, growth factor receptors, transduction signaling proteins, and DNA-binding proteins, among others [12]. On the other hand, mutations that inactivate tumor gene suppressors liberate the genetic inhibition and thereby potentiate tumor cell proliferation. Cellular proliferation is not an autonomic event; it is regulated by intercellular communication, ensuring normal tissue integrity. Examples of intercellular signals include contact inhibition and anchorage-dependent growth, which are both hallmarks of normal cells [13]. Additionally, cell-to-cell microRNA exchange is an important means of cell communication and process regulation [14,15,16]. miRNAs regulating oncogenes are known as anti-oncomiRs, and miRNAs inhibiting tumor gene suppressors are known as oncomiRs [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. One of the most important features of miRNAs is their ability to regulate multiple mRNA targets [18], allowing for the analysis of numerous coding genes with a single miRNA [19]. MiRNAs are non-coding regulatory RNAs 19–25 nucleotides (nt) in size that are produced by RNA polymerase II (pol II) and III (pol III) derived from transcripts of coding or non-coding genes. Many miRNAs are tissue-specific or differentiation-specific, and their temporal and spatial expression patterns modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by base pairing with the complementary nucleotide sequences of target mRNAs [20,21]. The sequence of partial and total complementarity binding of miRNAs to target mRNAs inhibits protein translation or degrades target mRNAs, respectively [18].

The bioinformatics prediction has indicated that each miRNA targets more than 100 RNA transcripts, and up to one-third of the total number of human mRNAs is regulated by these non-coding genes [20,21,22]. Therefore, miRNAs exert deep effects on gene expression in almost every biological process, such as proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, apoptosis, migration, and invasion [15]. Indeed, restoration of miRNA expression or miRNA inhibition alters cellular processes [23]. Therefore, miRNAs are a powerful tool for gene therapy, prognosis, and diagnosis of malignant diseases. miRNAs expression that is affected by HPV specifically occurs as a cause of cervical cancer [24], while some others are altered independently of HPV infection, probably as consequence of the progression of the disease. Distinguishing between the involvement of miRNAs as a consequence and/or a cause of cancer has not been solved until now; however, it is a fact that they orchestrate gene profile changes along carcinogenesis [25,26]. Genes regulated by miRNAs are of great value for cancer treatment, diagnosis, and prognosis, prompting substantial search on this topic [17,27,28]. Microarray technology has revolutionized the field of genomics, allowing researchers to simultaneously analyze the expression of thousands of genes across different conditions. This approach has been valuable in cancer research, where identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between normal and tumor tissues can reveal insights into the molecular mechanisms driving cancer progression in cervical cancer [29,30,31].

In this study, we utilized several publicly available microarray datasets to perform a comprehensive analysis of DEGs in cervical cancer. Our goal was to find highly expressed genes in cervical cancer compared to healthy controls, and to determine whether these genes are regulated by specific miRNAs through a bioinformatics tool. The datasets used include GSE39001, GSE9750, GSE7803, GSE6791, GSE63514, and GSE52903. These datasets collectively encompass a wide range of cervical cancer samples and controls, allowing for a robust analysis of gene expression patterns. GSE39001, GSE7803, GSE6791, GSE63514, and GSE52903 further expand the dataset, providing additional data from different stages and types of cervical cancer, as well as controls. GSE arrays provided data from 197 cervical carcinomas and 95 control cervical tissues. By integrating data from these diverse studies, we aimed to improve the robustness of our findings and uncover novel insights into the molecular drivers of cervical cancer. Identifying key DEGs may facilitate the development of targeted therapies, ultimately improving patients’ outcomes.

2. Results

2.1. Microarray Data Information and DEGs Analysis in Cervical Cancer

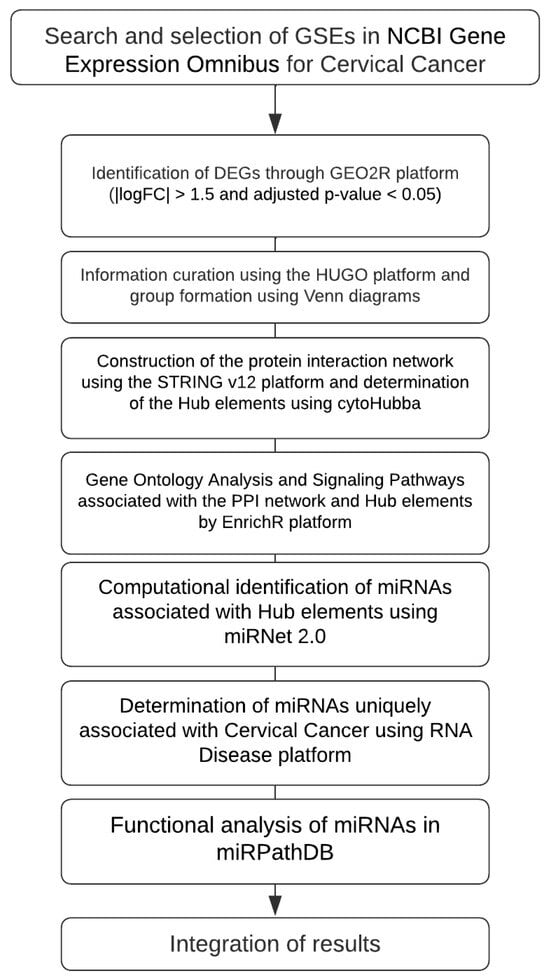

According to our workflow diagram strategy (Figure 1), six GEO microarray datasets (GSE39001, GSE9750, GSE7803, GSE6791, GSE63514, and GSE52903) were selected through a systematic screening process to ensure analytical comparability, biological relevance, and data quality. The inclusion criteria required the following: (I) availability of raw or normalized expression matrices; (II) clearly annotated clinical information, including the presence of cervical cancer samples and non-cancer controls; and (III) use of well-standardized microarray platforms with reliable probe annotation. Several additional GEO series were initially examined but then excluded due to a lack of matched controls, small sample sizes, incomplete metadata, or platforms with limited probe coverage, all of which hindered cross-study comparability.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the bioinformatics analysis. Identification of DEGs from GEO datasets, construction of PPI networks, enrichment analysis, and integration of miRNA functional data associated with cervical cancer. Each microarray was analyzed independently, and a common pattern of gene expression was selected for the subsequent analysis following this consideration (adj. p < 0.05, |logFC| > 1.5).

The final selected datasets included both the Affymetrix and Agilent arrays: two platforms known for producing reproducible gene-expression profiles across independent studies. Since cross-platform merging can introduce artificial batch effects, each dataset was analyzed separately using GEO2R R 4.2.2, Biobase 2.58.0, GEOquery 2.66.0, limma 3.54.0, with adjusted p-values < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1.5 as thresholds. Only cancer cervical samples and their corresponding controls were included in the differential expression analysis and examined for common characteristics, such as tumor stage, VPH type, and histology (Table 1 and Supplementary Material Table S1).

Table 1.

General information on expression sets and platforms from cervical cancer and healthy control samples.

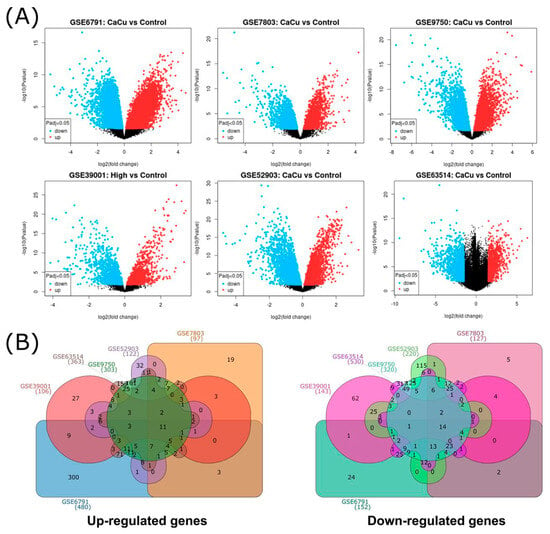

Across the six studies, a total of 2955 unique differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified. As expected, datasets with larger sample sizes or paired tumor–control designs, particularly GSE6791, GSE9750, and GSE63514, produced the highest numbers of DEGs. A graphical overview of the DEG distribution is shown in Figure 2A, where volcano plots display upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes for each dataset.

Figure 2.

General distribution of DEGs by microarray. (A) Volcano plots from 6 microarray analyses, blue and red dots represented upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. The black dots represent genes with basal expression. (B) Common upregulated and downregulated differentially expressed genes from cervical cancer visualized through a Venn diagram, (GSE39001 (106 up and 143 down DEGs), GSE52903 (122 up and 220 down DEGs), GSE63514 (363 up and 530 down DEGs), GSE6791 (480 up and 152 down DEGs), GSE7803 (97 up and 127 down DEGs), and GSE9750 (303 up and 320 down DEGs)). The numbers indicate the genes that are shared between microarrays.

To identify the recurrent signals across studies, DEGs from each dataset were compared, revealing the overlap patterns shown in Figure 2B. This visualization indicates the number of unique and shared upregulated and downregulated genes across microarrays. Consistently with the recent literature on integrative transcriptomic workflows [32], variation in DEG counts across studies reflects differences in sample size, study design, and platform chemistry. This highlights the importance of dataset-level analysis before identifying common transcriptional changes.

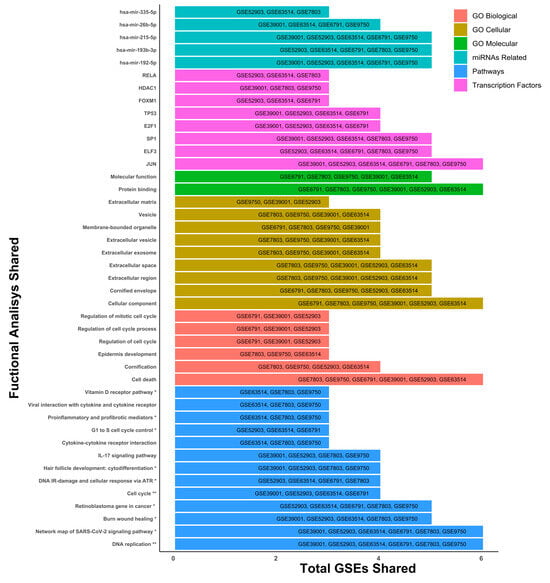

2.2. Gene Ontology (GO) Terms and KEGG Pathway Analysis by GSE

Once the DEGs were determined for each of the microarrays, a gene ontology analysis was carried out to identify the cellular, molecular, and biological mechanisms, as well as the main signaling pathways, transcription factors, and miRNAs that are most representative and shared across the different microarrays. Within the results, we can observe processes such as cell death (GO Biological), regulation of DNA replication (Pathways), protein binding regulation processes (GO Molecular), and the JUN transcription factor (Transcription factors), standing out as elements that are involved and shared in the six microarrays selected for this study (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

General ontology analysis. Gene ontology was determined with 197 tissue samples, with cervical cancer and 95 controls. Differentially expressed genes with a threshold of 1.5 and p-adjusted < 0.05 were used for ontology analysis. The pathway analysis was performed using the KEGG and Wiki Pathways databases; * is significant in only one database and ** is significant in both databases.

However, we also observed that other elements were shared in microarrays 3, 4 and 5, as the signaling pathway associated with IL-17 (Pathways), viral interactions related to cytokine receptors (Pathways), epidermis development (GO Biological), different extracellular elements such as vesicles or exosomes (GO Cellular), transcription factors like RELA, HDAC, and FOXM1, and miRNAs such as hsa-miR-215-5p, hsa-miR-26b-5p, and hsa-miR-335-5p stand out as elements involved in the development of CC in at least three of the six microarrays (Figure 3). Exploring transcription factors SP1, ELF3, E2F1, TP53, RELA, HDAC, and FOXM1 and their relationship with cervical cancer can reveal essential function in cancer progression. Importantly, the cellular component analysis was linked to cell death, protein binding, DNA replication, JUN transcription factor, and several miRNAs (miR-192-5p, miR-193b, and miR-215-5p) being the most representative changes among the six microarrays.

2.3. Microarray Analysis Integration and Common Gene Determination

To derive a high-confidence gene signature and reduce inter-dataset variability, we adopted an intersection-based integration strategy, retaining only genes that were consistently dysregulated in more than four of the six datasets (Table 2). This approach is widely used in integrative genomics to identify reproducible molecular alterations and parallels the strategy applied by Farrim et al. (2024) [32], who selected genes shared across more than four transcriptomic datasets to ensure robustness and reduce study-specific bias.

Table 2.

Distribution of the main DEGs between GSEs.

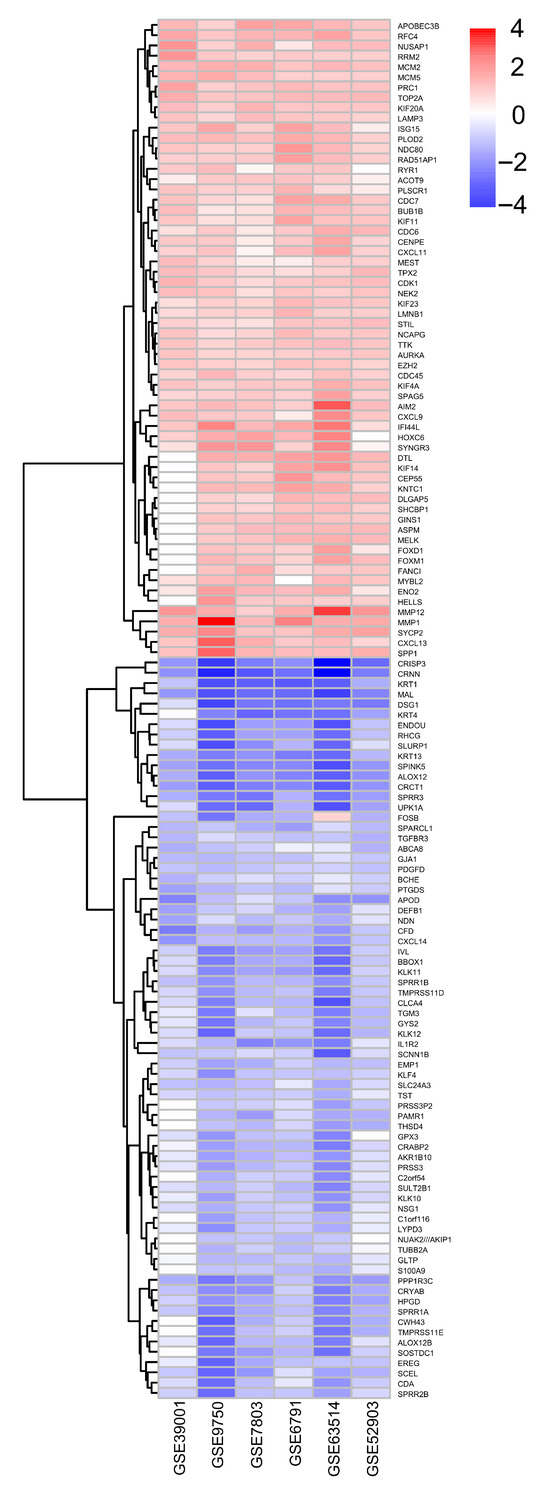

A similar tendency was observed among the 134 selected DEGs: 62 and 72 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in cervical cancer versus the control samples (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Differentially expressed genes between microarrays. Differentially expressed genes that were upregulated and downregulated were grouped based on their fold change of 1.5 and p-adjusted < 0.05.

We selected the most prominently altered genes: 11 were upregulated coding genes (KIF4A, MCM5, RFC4, PLOD2, MMP12, PRC1, TOP2A, MCM2, RAD51AP1, KIF20A, and AIM2) and 14 were downregulated genes (CXCL14, KRT1, KRT13, MAL, SPINK5, EMP1, CRISP3, ALOX12, CRNN, SPRR3, PPP1R3C, IVL, CFD, and CRCT1), which were possibly involved in the cause and/or consequence, as well as biomarkers for cervical cancer. It should be noted that data from gene ontology and DEGs were different: while in the former, the TFs (SP1, ELF3, E2F1, P53, RELA, HDAC, and FOXM1) were the most relevant, they did not appear as DEGs. However, in later analysis, different types of genes (CXCL14, KRT1, KRT13, MAL, SPINK5, EMP1, KIF4A, MCM5, RFC4, PLOD2, CRISP3, MMP12, ALOX12, PRC1, TOP2A, MCM2, CRNN, RAD51AP1, SPRR3, KIF20A, PPP1R3C, AIM2, IVL, CFD, and CRCT1) were found to be more prominently dysregulated (Figure 4).

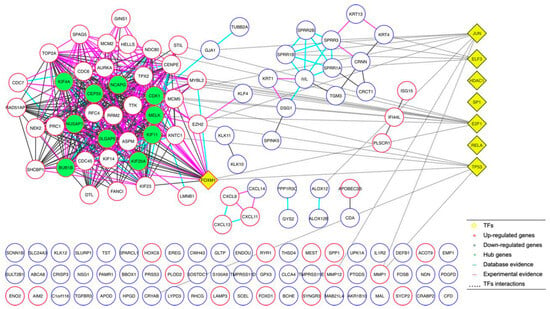

2.4. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analyses

Once we determined the 134 DEGs shared between the microarrays and their expression trends, we continued our study by performing a protein–protein interaction analysis, generating an interaction network determining 10 DEGs (KIF4A, NUSAP1, BUB1B, CEP55, DLGAP5, NCAPG, CDK1, MELK, KIF11, and KIF20A) of the greatest importance (hub proteins), based on their evidence of interaction as well as the number of interactions they presented (Figure 5). Additionally, we observed that these 10 DEGs were characterized by being consistently overexpressed in their respective microarrays. Expression and interaction analysis identified the different genes associated with cervical cancer; therefore, their importance should be integrated. Interestingly, the proteins (hub) that participated in the protein–protein interaction network were not the first DEGs; however, they could be linked to TFs in GO analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Protein–protein interaction network analyses. The analysis of protein–protein interaction using 134 DEGs shared between the microarrays, generating an interaction network.

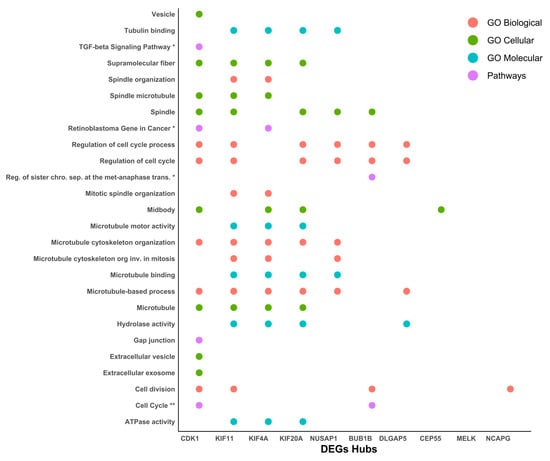

2.5. Functional Enriched Process for Hub Proteins

After the protein–protein interaction network was generated and we had obtained the 10 most relevant hub proteins in the network, we performed an ontology and signaling pathway analysis on these 10 elements, finding that CDK1 (cyclin-dependent kinase 1), Human kinesin family member 11 (KIF11), kinesin superfamily 4A (KIF4A), kinesin superfamily 20A (KIF20A), and Nucleolar and spindle-associated protein 1 (NUSAP1) were the five elements with the most significant participation in different processes related to the cytoskeleton, ATP synthesis, and cell-cycle regulation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Functional enriched process for hub proteins. Ontology and signaling pathway analysis were performed on the protein–protein interaction network. The pathway analysis was performed using the KEGG and Wiki Pathways databases; * is significant in only one database and ** is significant in both databases.

Additionally, their participation in GO, DEGs, and hub analysis was also remarked upon, suggesting an implication of the cause and/or consequence of cancer cervical. Cdk1 is known as a transcriptional target of E2F1 [33] and Sp1 proteins [34] which is responsible for G1/S progression [33,34], and its overexpression has been stated in cervical cancer [35]. CDK1 upregulation at the mRNA and protein level through HPV-E6 p53 modulation has been suggested [36,37]. On the other hand, the KIF11 protein plays a vital role in cell-cycle regulation and it has been implicated in the tumorigenesis and progression of various cancers, except in cervical cancer [34]. However, Kinesin Family Member 4A (KIF4A), a member of the kinesin 4 subfamily of kinesin-related proteins, serves an important role in cell division, and its overexpression has been shown in cervical cancer [38,39].

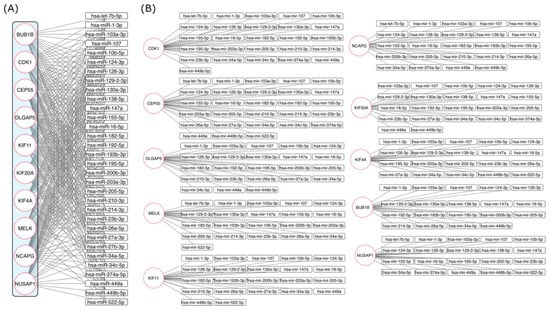

2.6. Hub Proteins and miRNAs Interaction Network Analyses

To determine the possible association between miRNAs and hub proteins, we used the online tool miRNet. A total of 149 miRNAs that had been experimentally reported to have had some type of interaction with at least two of the hub proteins were analyzed. For subsequent studies, only 31 miRNAs that presented an interaction with at least five or more of the hub proteins, were selected (Figure 7A,B).

Figure 7.

Interaction network between mRNAs of hub proteins and miRNAs. (A) miRNAs and mRNAs of hub protein interactions were determined using the online tool miRNet. (B) miRNAs and mRNAs of hub protein interactions were separated and amplified to clarify their association.

Additionally, miRNA expression in cervical cancer and mRNA regulation were searched in previously published papers (Table 3). Based on previous reports of miRNA expression, we separated them into three categories: (1) miRNAs with an experimentally defined expression profile, (2) miRNAs with dual expression that were upregulated and downregulated, and (3) miRNAs with no previous experimental reports. Interestingly, the mRNAs of the hub genes were shown to be regulated by miR-103-3p, miR-107, miR-124-3p, miR-129-2-3p, miR-147a, miR-16-5p, miR-205-5p, and miR-34a-5p, suggesting gene interrelation acting as cause and/or consequence of cervical cancer. Additionally, miR-1-3p, miR-126-3p, miR-449-5p, and miR-195-5p were displayed, regulating 9 of the 10 hub genes, except for KIF20A, MELK, and KIF11, respectively.

Table 3.

miRNAs and targets regulated in cervical cancer. — No information was found in cervical cancer, ↑ overexpressed miRNAs in cervical cancer, ↓ underexpressed in cervical cancer, ↓↑ overexpressed and underexpressed in cervical cancer.

Furthermore, miR-10b-5p, miR-23b-3p, miR-449a, and miR-130a-3p were found to modulate 4, 4, 6 and 7 of the 10 hub genes, respectively. On the other hand, miR-155-5p and miR182-5p were shown to regulate 6 of the 10 hub genes, while miR-200b-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-192-5p, miR-193b-3p, miR-203a-3p, miR-210-3p, miR-214-3p, miR-34c-5p, and let-7b-5p were found to modulate 5 of the 10 hub genes, Figure 7A,B. Regulation of the hub genes through upregulated or downregulated microRNAs has previously been shown. In this instance, microRNAs, miR-103-3p, miR-205-5p, miR-130a-3p, miR-192-5p, and miR-210-3p have been found to have overexpressed, while miR-107, miR-124-3p, miR-147a, miR-16-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-34c-5p, miR-126-3p, miR-10b-5p, miR-23b-3p, miR-200b-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-203a-3p, miR-214-3p, and let-7b-5p expression has been revealed to have reduced. On the other hand, the expression of miR-195-5p, miR-155-5p, miR-193b-3p, and miR-449a has been ambiguous, with upregulation or downregulation in cervical cancer; and the expression of miR-129-2-3p and miR-1-3p, miR-449b-5p, and miR-522-5p in cervical cancer is unknown, Table 3.

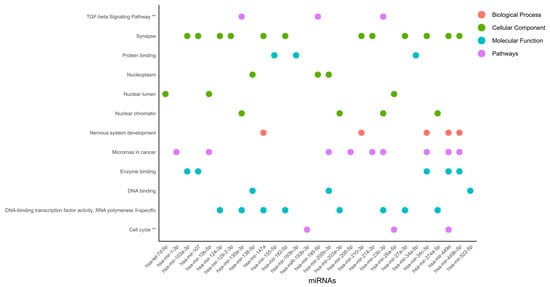

2.7. miRNAs Functional Enriched Processes

Functional enriched processes for miRNAs (Figure 8) revealed nuclear organization, including nucleoplasm, nuclear lumen, and nuclear chromatin, suggesting gene regulation at the organelle shape and dynamic organization levels.

Figure 8.

Functional enriched processes regulated by miRNAs. miRNAs were classified into 4 categories of processes regulated by miRNAs involved in cervical cancer. The pathway analysis was performed using the KEGG and Wiki Pathways databases; ** is significant in both databases.

Nuclear organization is as dependent on protein binding as it can be on enzyme binding, DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II-specificity, and DNA binding. This type of regulation could be linked to the TGF-beta signaling pathway and the cell cycle. Interestingly, in the synapse, microRNAs in cancer, and DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II-specific processes were regulated by 12, 9, and 8 miRNAs, respectively, which were ranked as the most representative among all processes. DNA-binding transcription factor activity and RNA polymerase II-specific processes were linked to nuclear chromatin by miR-130a-3p, miR-203a-3p, miR-23b-3p, and miR-374a-5p, Figure 8. Further TGF-beta signaling pathway DNA-binding transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II-specific, and nuclear chromatin processes were regulated by miR-130a-3p and miR-23b-3p. Interestingly, microRNAs in cancer were linked to nervous system development and enzyme binding by miR-34c-5p, miR-449a, and miR-449b-5p. In agreement, the activation of nervous-system-related genes in cervical cancer has been previously reported [77].

3. Discussion

The bioinformatics analyses performed on six cervical cancer expression microarray studies showed 1471 and 1492 upregulated and downregulated coding genes, respectively. Across the different platforms’ analysis, a total of 134 coding genes presented similar expression in at least in four of the six microarrays analyzed. From 134 common genes, 62 and 72 were upregulated and downregulated, respectively. The GO analysis showed several associations with cell death processes, regulation of DNA replication, protein-binding regulation, and transcription factors as JUN, SP1, ELF3, E2F1, P53, RELA, HDAC, and FOXM1, which have been reported to contribute to the promotion of cervical cancer, which is also regulated by oncomiRs and tumor-suppressing microRNAs [78,79,80], which are also associated with DEGs in this work. In agreement with the results found here, the impact of this microRNA deregulation on cervical cancer has been previously stated. hsa-miR-26b-5p has been reported to increase in cervical cancer [81,82], and upregulation of hsa-miR-215-5p has been related to poor survival [83]. However, hsa-miR-335-5p, found to be overexpressed in our analysis, has been previously reported as an anti-oncomiRNA [84]; therefore, this preliminary analysis may be inconclusive and the study population differences such as ethnicity, HPV infection, and advancement of the disease may be playing a role in this discrepancy. Eleven coding genes were upregulated (KIF4A, KIF20A, MCM2, MCM5, TOP2A, RFC4, RAD51AP1, PLOD2, MMP12, PRC1, and AIM2) and 14 were downregulated (CXCL14, KRT1, KRT13, MAL, SPINK5, EMP1, CRISP3, ALOX12, CRNN, SPRR3, PPP1R3C, IVL, CFD, and CRCT1); these genes were found to be differentially expressed between cervical cancer and the controls. It was previously shown that several proteins participate in a cellular program to enhance DNA replication by an increase in replicative helicase proteins (MCM2, MCM4, MCM5, MCM6, and MCM10), DNA polymerases (PLOA1/E2/E3/Q), and cytokinesis through motor proteins (KIF11, KIF14, KIF4A, and PRC1) in cervical cancer progression [39]. KIF4A is dominantly localized in the nuclear matrix and is associated with chromosomes during mitosis [85] and mediates cytokinesis during cervical cancer progression [39]. Another Kinesin family member, KIF20A, has been correlated with HPV infection, clinical stage, tumor recurrence, lymphovascular space involvement, pelvic lymph node metastasis, and poor outcome in early-stage cervical squamous cell carcinoma patients [86]. Additionally, it should be noted that in our work, the genes from GO and protein–protein interaction analyses were different. The upregulated coding genes were mainly related to cytokinesis, DNA repair, and replication. Interestingly, their miRNAs regulators are downregulated. The expression of miR-107 [41,42], miR-124-3p [44,53], miR-126-3p [45,46], miR-138-5p [49,50], miR-16-5p [53,54], miR-200b-3p [61,62], miR-203a-3p [63], miR-214-3p, miR-23b-3p, miR-26a-3p, miR-34a-5p, and miR-34c-5p have been previously reported as having diminished, similarly to our data. Interestingly, the same microRNAs that regulate the DEGs modulate the genes resulting from protein–protein interaction network analyses (KIF4A, NUSAP1, BUB1B, CEP55, DLGAP5, NCAPG, CDK1, MELK, KIF11, and KIF20A); these denominated hub proteins are based on their evidence of interaction, as well as the number of interactions they present. Hub proteins have been implicated in disease progression, ensuring constant tumorigenesis-related proteins. Likewise, NUSAP1 is a crucial mitotic regulator that binds to microtubules and mediates their attachment to chromosomes, ensuring the accurate distribution of genetic material to the two daughter cells, and it is associated with cervical cancer progression [87]. HPV 18 E6/E7 promoted maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) expression by activating E2F1 [30] and DLGAP5 stabilized E2F1 through its binding, preventing the ubiquitination of E2F1 via USP11 [88]. E2F1 binds to the promoter of CDK1 [30], NCAPG [89], and TOP2A, promoting its transcription [90], which is potentiated by the expression of E7 [91]. CDK1 is known as a transcriptional target of Sp1 [31], which is responsible for G1/S progression [33,34]. HPV-E6 upregulates CDK1 at mRNA and protein [36], suggesting that CDK1 modulation is p53-dependent [37]. p53 activated the transcription p21 a Cdk inhibitor. CDK1 binds p21 with lower affinity than Cdk2, abrogating the postmitotic checkpoint in E6-expressing cells, favoring cervical cancer development through the induction of polyploidy [92]. The levels of the protein p53 could influence CDK1 expression. It has been reported that miR-92a-1-5p downregulates the expression of TP53 [93]. The Cyclin B1/CDK1- complex induces the phosphorylation of PRC1 [94]: a protein present at high levels during the S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. MMP12 expression is regulated positively by MTA2 via AP1 through phosphorylation of the pathway ASK1/MEK3/p38/YB1, leading to tumor cell metastasis [95]. JUN has reported an increase in cancer versus CIN and normal tissue [96]. The expression of phosphorylated c-Jun, c-Fos, and ERK1/2, a key factor of the ERK signaling pathway, was increased in the progressive lesions of the cervix [97]. Several genes have been reported as being regulated by miRNAs, while MELK is regulated by miR-107 [41,42], miR-124-3p [44,53], miR-16-5p [53,54], miR-200b-3p [61,62], miR-203a-3p [63], miR-214-3p, miR-23b-3p, miR-26a-3p, and miR-34a-5p. DLGAP5 is modulated by miR-107 [41,42,70], miR-124-3p [44,53], miR-126-3p [45,46], miR-16-5p [53,54], miR-200b-3p [61,62], miR-23b-3p, miR-26a-3p, miR-34a-5p, and miR-34c-5p; it should be noted that there is a difference of two miRNAs (miR-203a-3p, miR-214-3p) and three miRNAs (miR-126-3p, miR-200b-3p and miR-34c-5p), respectively, between these two coding genes. E2F1 downregulates miR-107 through its binding to the promoter of miR-107, inducing transcriptional repression [98]. On the other hand, E2F1 is downregulated by miR-16-5p [99] and miR-34c-5p [84]. This study used multiple microarray datasets of patients diagnosed with cervical cancer, but some data, such as associated comorbidities, duration of illness, or presence and related HPV, could not be fully represented due to limitations in the GEO database or the data reported by microarray authors. Furthermore, microarray technology has limitations, such as platform-specific probe differences, incomplete transcript coverage, and several variations in metadata, which can limit the interpretation of associations with disease progression or comorbidities not reported from samples. Meanwhile, PPI analysis depends on the existing experimental data. Additionally, protein interaction databases may not include all possible interactions, especially for poorly understood proteins or pathways. Similarly, the identification of miRNAs related to DEGs in cervical cancer was performed using two platforms, such as miRNet and RNADisease, but they rely on known interactions, which can cause discrepancies between databases. Additionally, the bioinformatic analysis of biological pathways, molecular functions, transcription factors, and miRNA interactions is based on the current definitions and databases, which may be incomplete or outdated. Remarkably, we aimed to integrate multiple microarray datasets to enable a broad identification of genes with potential biomedical importance in cervical cancer, including samples from various HPV genotypes (primarily HPV16), different tumor stages (IB–IIB), and diverse squamous histological subtypes introducing clinical variability that reflects the biological diversity of the disease and enhances the translational relevance of the findings. Furthermore, the processes found herein were linked to different genes; therefore, it is imperative to integrate the processes, systems, and gene regulation. Unraveling the coding and non-coding RNAs regulated during cervical cancer is an important factor in achieving new treatments and biomarkers.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Diagram

Gene expression datasets for cervical cancer were retrieved from the GEO database, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by using GEO2R R 4.2.2, Biobase 2.58.0, GEOquery 2.66.0, limma 3.54.0 (|logFC| > 1.5, adjusted p < 0.05). Curated gene lists (based on HUGO nomenclature and Venn analysis) were used to construct a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network in STRING v12, with the hub genes determined through cytoHubba. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses were performed using EnrichR. Hub gene–associated miRNAs were predicted with miRNet 2.0, disease-specific associations were retrieved from the RNA Disease database, and functional miRNA analyses were conducted in miRPathDB 2.0. The integrated analysis identified key genes, miRNAs, and pathways associated with cervical cancer (Figure 1).

4.2. Gene Expression Profile Data Collection

Microarray samples from healthy patients and patients with cervical cancer from 6 different tissue experiments of gene expression were selected from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, (accessed on 13 June 2025)) (Table 1). Raw data can be revised in Supplementary Material Table S1.

4.3. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified independently for each microarray by using the GEO2R bioinformatics tool. This strategy helps to avoid potential biases associated with the batch effect, which can arise when combining heterogeneous datasets in a single analysis.

This ensured that comparisons between the different microarrays were performed only with the most relevant DEGs in each case, in a robust manner and without introducing external technical variability. During the analysis, only samples corresponding to controls and cases with cervical cancer were selected.

Only the genes with a log FC (fold-change) > |1.5| and adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant in the comparisons of cervical cancer and the controls, as recommended by DJ McCarthy and GK Smyth in 2009 for the analysis of biological data [100].

The adjusted p-value (adj. p), using the Benjamini–Hochberg (BHC) procedure, was applied to limit the false discovery rate (BHC method) [101]. The obtained upregulated and downregulated DEGs were classified into the cervical cancer and control groups, and the shared information from each microarray was identified with the help of Venn diagrams created with an online platform (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/ (accessed on 16 December 2025)) [102]. The shared information was organized in lists and curated by eliminating synonymous gene names with the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee platform (https://www.genenames.org/) [103].

4.4. PPI Network Construction

The DEG lists selected for the CC and controls association were uploaded into the STRING platform (STRING; v12.0; https://string-db.org/) to create protein–protein interaction networks (PPI). The parameters for constructing the DEG CC/Control network on STRING included experimental information, database curation, and co-expression evidence to reduce the rate of false-positive results (medium confidence, 0.400) [104]. Only the nodes that had at least two connections on the produced network were kept for analysis. The hub proteins within the network were determined using the maximal clique centrality method (MCC) parameter, available in the cytoHubba app for Cystoscope (v3.10.1) [105,106]. To determine the proteins of high biological value within the PPI network groups (hub proteins), the hub option from the EnrichR platform (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/ (accessed on 16 December 2025)) was used. The Expression2Kinases program (https://www.maayanlab.net/X2K/ (accessed on 16 December 2025)) [107] was used to identify the regulatory proteins (mainly transcription factors (TFs) and kinases) involved in important signaling pathways that potentially regulate a PPI network based on the gene list submitted [108].

4.5. DEG Annotation and Functional Analyses

The biological value of the PPI, derived from the DEGs Cervical Cancer/Controls and for the hub proteins, was determined through an enrichment analysis that included KEGG pathways, transcription factors (TFs), dbGap genotype/phenotypes, biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC) with the online EnrichR platform (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/ (accessed on 16 December 2025)) [108]. Only ontology annotation terms with adj. p < 0.05 were considered significant.

4.6. Computational Identification of miRNAs Associated with Cervical Cancer

The miRNAs associated with the hub genes of the DEGs-Cervical Cancer/Controls network were determined by using the miRNet platform (https://www.mirnet.ca/ (accessed on 16 December 2025)) [109]. This database contains information on interactions between miRNAs and their target gene, incorporating various database sources such as miRTarBase v8.0, TarBase v8.0, and miRecords v1.0 [110,111]. In the network analysis, the miRNAs that had at least two interactions with hub genes or were reported for cervical cancer development were kept for the subsequent analysis on the RNA-Disease platform (http://www.rnadisease.org/) [112]. On this last platform, the search for miRNAs of interest was carried out to collect experimental and computational evidence related to their expression in cervical cancer. Only miRNAs with experimental evidence were manually analyzed in detail.

4.7. Functional Analysis of miRNAs in miRPathDB

Functional analysis of miRNAs was performed using the miRPathDB V4.0 [113], a bioinformatics tool designed for the annotation and functional analysis of miRNAs that collects information that is validated in the literature, thus allowing us to discover some of the biological implications and roles of miRNAs. For our study, only terms with an Adj. p < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

5. Conclusions

The integrative transcriptomic and network-based analysis performed in this study provides a robust and reproducible molecular framework to understand the regulatory landscape of cervical cancer. Combining six independent GEO datasets, encompassing diverse populations and experimental platforms, we overcame cohort-specific variability and minimized batch effects, achieving a consensus gene signature that reflects biologically consistent transcriptional alterations. The hub genes KIF4A, NUSAP1, BUB1B, CEP55, DLGAP5, NCAPG, CDK1, MELK, KIF11, and KIF20A converge on pathways that are essential for mitosis, spindle formation, and cell-cycle progression, all of which are recognized hallmarks of cancer development. In parallel, the integration of miRNA–mRNA regulatory networks revealed a coordinated pattern of post-transcriptional dysregulation. miR-107, miR-124-3p, miR-16-5p, miR-126-3p, and let-7b-5p are inversely expressed to hub genes, supporting a mechanistic model that contributes to the persistent activation of mitotic and proliferative pathways, amplifying tumor aggressiveness. It should be noted that combining data from different laboratories, technological platforms, and protocols leads to a high risk of strong batch effects. These effects can mask biological differences or generate spurious signals of differential expression. The integration, consisting of very diverse samples, should be interpreted with caution and merely as a general expression signature, not as a precise result for a specific population. Our approach was adopted to minimize potential cohort-specific biases and highlight only the transcriptional changes that were consistently or globally observed in independent analyses, identifying only the common expression pattern related to the disease, rather than effects associated with specific populations or contexts. Despite strong statistical support, the results still lack functional and experimental validation. However, these findings provide a system-level perspective, linking transcriptional deregulation with disrupted post-transcriptional control and thereby strengthening the molecular basis for future biomarker validation and therapeutic targeting in cervical cancer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010258/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; methodology, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V. and C.R.S.-A.; software, D.A.A.-C. and R.C.-V.; validation, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V. and Y.L.-H.; formal analysis, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., D.A.G.-L., Y.L.-H. and A.J.G.-L.; investigation, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., D.A.G.-L., Y.L.-H., R.G.-H., C.A.R.-E., S.H.S.-R., A.J.G.-L. and C.R.S.-A.; resources, Y.L.-H., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; data curation, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., D.A.G.-L., Y.L.-H., R.G.-H., C.A.R.-E., S.H.S.-R., H.H.-L., J.A.V.-S. and A.J.G.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; writing—review and editing, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., A.J.G.-L., J.A.L. and C.R.S.-A.; visualization, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., D.A.G.-L., Y.L.-H., R.G.-H., C.A.R.-E., S.H.S.-R. and A.J.G.-L.; resources, Y.L.-H., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; supervision, D.A.A.-C., R.C.-V., D.A.G.-L., Y.L.-H., R.G.-H., C.A.R.-E., S.H.S.-R. and A.J.G.-L.; resources, Y.L.-H., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; project administration, Y.L.-H., A.J.G.-L. and J.A.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L.-H. and J.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONAHCYT [FIDCC 2022/321616].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank CONAHCYT for the fellowships of D.A.A.-C.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, P.A.; Jhingran, A.; Oaknin, A.; Denny, L. Cervical cancer. Lancet 2019, 393, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMaio, D.; Liao, J.B. Human papillomaviruses and cervical cancer. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 66, 125–159. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, N.; Howley, P.M.; Münger, K.; Harlow, E. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 1989, 243, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, O.; Krishna, S. Molecular interactions of ‘high risk’human papillomaviruses E6 and E7 oncoproteins: Implications for tumour progression. J. Biosci. 2003, 28, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffner, M.; Werness, B.A.; Huibregtse, J.M.; Levine, A.J.; Howley, P.M. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 1990, 63, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Lopez, A.J.; Manzanares-Acuna, E.; Lopez-Hernandez, Y.; Castaneda-Delgado, J.E.; Fraire-Soto, I.; Reyes-Estrada, C.A.; Gutierrez-Hernandez, R.; Lopez, J.A. UVB inhibits proliferation, cell cycle and induces apoptosis via p53, E2F1 and microtubules system in cervical cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermeking, H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Sevignani, C.; Dumitru, C.D.; Hyslop, T.; Noch, E.; Yendamuri, S.; Shimizu, M.; Rattan, S.; Bullrich, F.; Negrini, M. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2999–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, G.A.; Croce, C.M. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.M.; Blume, S.; Borst, M.; Gee, J.; Polansky, D.; Ray, R.; Rodu, B.; Shrestha, K.; Snyder, R.; Thomas, S. Oncogenes, malignant transformation, and modern medicine. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1990, 300, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A. Tumor suppressor genes. Science 1991, 254, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, P.K.; Bliss, S.A.; Patel, S.A.; Taborga, M.; Dave, M.A.; Gregory, L.A.; Greco, S.J.; Bryan, M.; Patel, P.S.; Rameshwar, P. Gap junction–mediated import of microRNA from bone marrow stromal cells can elicit cell cycle quiescence in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdova-Rivas, S.; Fraire-Soto, I.; Mercado-Casas Torres, A.; Servín-González, L.S.; Granados-López, A.J.; López-Hernández, Y.; Reyes-Estrada, C.A.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.; Castañeda-Delgado, J.E.; Ramírez-Hernández, L. 5p and 3p strands of miR-34 family members have differential effects in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechavi, O.; Erlich, Y.; Amram, H.; Flomenblit, L.; Karginov, F.V.; Goldstein, I.; Hannon, G.J.; Kloog, Y. Cell contact-dependent acquisition of cellular and viral nonautonomously encoded small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.J.G.; López, J.A. Multistep model of cervical cancer: Participation of miRNAs and coding genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 15700–15733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Jones, S.; Saini, H.K.; Van Dongen, S.; Enright, A.J. miRBase: Tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D154–D158. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, D.; Villén, J.; Shin, C.; Camargo, F.D.; Gygi, S.P.; Bartel, D.P. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 2008, 455, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimson, A.; Farh, K.K.-H.; Johnston, W.K.; Garrett-Engele, P.; Lim, L.P.; Bartel, D.P. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selbach, M.; Schwanhäusser, B.; Thierfelder, N.; Fang, Z.; Khanin, R.; Rajewsky, N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 2008, 455, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, S.; Luan, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Tang, H. MicroRNA-214 is aberrantly expressed in cervical cancers and inhibits the growth of HeLa cells. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.-K.; McCoy, J.P.; Banerjee, N.S.; Rader, J.S.; Broker, T.R.; Meyers, C.; Chow, L.T.; Zheng, Z.-M. Oncogenic HPV infection interrupts the expression of tumor-suppressive miR-34a through viral oncoprotein E6. Rna 2009, 15, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Q.; Zhou, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, Z. Aberrant microRNA expression in human cervical carcinomas. Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 1242–1248, Erratum in Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilting, S.; Snijders, P.; Verlaat, W.; Jaspers, A.v.; Van De Wiel, M.; Van Wieringen, W.; Meijer, G.; Kenter, G.; Yi, Y.; Le Sage, C. Altered microRNA expression associated with chromosomal changes contributes to cervical carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2013, 32, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Pramodh, S.; Hussain, A.; Elsori, D.; Lakhanpal, S.; Kumar, R.; Alsaweed, M.; Iqbal, D.; Pandey, P.; Al Othaim, A. Understanding the role of miRNAs in cervical cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic responses. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1397945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doghish, A.S.; Ali, M.A.; Elyan, S.S.; Elrebehy, M.A.; Mohamed, H.H.; Mansour, R.M.; Elgohary, A.; Ghanem, A.; Faraag, A.H.; Abdelmaksoud, N.M. miRNAs role in cervical cancer pathogenesis and targeted therapy: Signaling pathways interplay. Pathol. -Res. Pract. 2023, 244, 154386. [Google Scholar]

- Sprio, A.E.; Carriero, V.; Levra, S.; Botto, C.; Bertolini, F.; Di Stefano, A.; Maniscalco, M.; Ciprandi, G.; Ricciardolo, F.L.M. Clinical characterization of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in asthma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Ji, M. Up-regulation of MELK by E2F1 promotes the proliferation in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Lei, Q.; Li, G.; Zhang, C. Identification of key genes and pathways in cervical cancer by bioinformatics analysis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrim, M.I.; Gomes, A.; Milenkovic, D.; Menezes, R. Gene expression analysis reveals diabetes-related gene signatures. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Zheng, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, W. Regulator of chromatin condensation 1 abrogates the G1 cell cycle checkpoint via Cdk1 in human papillomavirus E7-expressing epithelium and cervical cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Bao, L.; Li, X.; Sun, G.; Yang, W.; Xie, N.; Lei, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, M. Identification and validation of the important role of KIF11 in the development and progression of endometrial cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Pan, H.; Wang, W.; Qi, C.; Gu, C.; Shang, A.; Zhu, J. MiR-495-3p and miR-143-3p co-target CDK1 to inhibit the development of cervical cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogi, K.; Koya, Y.; Yoshihara, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Miki, R.; Miyamoto, E.; Fujimoto, H.; Kitami, K.; Iyoshi, S.; Tano, S. 9-oxo-ODAs suppresses the proliferation of human cervical cancer cells through the inhibition of CDKs and HPV oncoproteins. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Thakur, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, F.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Molecular mechanism of anti-cancerous potential of Morin extracted from mulberry in Hela cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 112, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, G.; Bourdon, V.; Chaganti, S.; Arias-Pulido, H.; Nandula, S.V.; Rao, P.H.; Gissmann, L.; Dürst, M.; Schneider, A.; Pothuri, B. Gene dosage alterations revealed by cDNA microarray analysis in cervical cancer: Identification of candidate amplified and overexpressed genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007, 46, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Duan, P.; Li, C. Interactome analysis of gene expression profiles of cervical cancer reveals dysregulated mitotic gene clusters. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3048. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. The promotional effect of microRNA-103a-3p in cervical cancer cells by regulating the ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 function. Hum. Cell 2022, 35, 472–485. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Han, N.; Liu, Z.; Yin, J. miR-107 activates ATR/Chk1 pathway and suppress cervical cancer invasion by targeting MCL1. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.; Xiong, Y.; Hanley, S.J.; Yue, J.; Watari, H. Musashi-2, a novel oncoprotein promoting cervical cancer cell growth and invasion, is negatively regulated by p53-induced miR-143 and miR-107 activation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H. Natural killer T cell cytotoxic activity in cervical cancer is facilitated by the LINC00240/microRNA-124-3p/STAT3/MICA axis. Cancer Lett. 2020, 474, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, B. Long non-coding RNA-NEAT1 promotes cell migration and invasion via regulating miR-124/NF-κB pathway in cervical cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 3265–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, I.; Gardiner, A.; Board, K.; Monzon, F.; Edwards, R.; Khan, S. Human papillomavirus type 16 reduces the expression of microRNA-218 in cervical carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, S.; Le, S.-Y.; Lu, R.; Rader, J.S.; Meyers, C.; Zheng, Z.-M. Aberrant expression of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive microRNAs in cervical cancer is required for cancer cell growth. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causin, R.L.; da Silva, L.S.; Evangelista, A.F.; Leal, L.F.; Souza, K.C.; Pessôa-Pereira, D.; Matsushita, G.M.; Reis, R.M.; Fregnani, J.H.; Marques, M.M. MicroRNA biomarkers of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in liquid biopsy. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6650966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Choi, C.H.; Choi, J.J.; Park, Y.A.; Kim, S.J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Kim, W.Y.; Kim, T.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.G.; et al. Altered MicroRNA expression in cervical carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2535–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Ji, H. MicroRNA-138 inhibits proliferation of cervical cancer cells by targeting c-Met. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.; Fei, D.; Zong, S.; Zhang, M.; Yue, Y. MicroRNA-138 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion through targeting hTERT in cervical cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shan, S.; Huo, Y.; Xie, Z.; Fang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, B. MiR-155-5p inhibits PDK1 and promotes autophagy via the mTOR pathway in cervical cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 99, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Cui, T.; Guo, W.; Wang, D.; Mao, L. MiR-155-5p accelerates the metastasis of cervical cancer cell via targeting TP53INP1. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 3181–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Liu, W.; Ding, F. miR-16-5p modulates the radiosensitivity of cervical cancer cells via regulating coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1. Pathol. Int. 2020, 70, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Ji, M.; Wang, Q.; He, N.; Li, Y. miR-16-5p/PDK4-mediated metabolic reprogramming is involved in chemoresistance of cervical cancer. Mol. Ther. -Oncolytics 2020, 17, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zou, J.; Wu, L.; Lu, W. Transcriptome analysis uncovers the diagnostic value of miR-192-5p/HNF1A-AS1/VIL1 panel in cervical adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzanehpour, M.; Mozhgani, S.-H.; Jalilvand, S.; Faghihloo, E.; Akhavan, S.; Salimi, V.; Azad, T.M. Serum and tissue miRNAs: Potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of cervical cancer. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Wences, H.; Martínez-Carrillo, D.N.; Peralta-Zaragoza, O.; Campos-Viguri, G.E.; Hernandez-Sotelo, D.; JIMéNEz-LóPEz, M.A.; Muñoz-Camacho, J.G.; Garzón-Barrientos, V.H.; Illades-Aguiar, B.; Fernandez-Tilapa, G. Methylation and expression of miRNAs in precancerous lesions and cervical cancer with HPV16 infection. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Liang, J.; Lin, S.; Wang, D.; Xie, Q.; Lin, Z.; Yao, T. N6-methyladenosine associated silencing of miR-193b promotes cervical cancer aggressiveness by targeting CCND1. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 666597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ning, Y.-e.; Gu, H.; Tong, Y.; Wang, N. MiR-195-5p inhibits malignant progression of cervical cancer by targeting YAP1. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, P.; Reyila, M.; Qi, X.; Yang, J. The Abnormal Expression of miR-205-5p, miR-195-5p, and VEGF-A in Human Cervical Cancer Is Related to the Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3929435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.X.; Zhang, Q.F.; Hong, L.; Pan, F.; Huang, J.L.; Li, B.S.; Hu, M. MicroRNA-200b suppresses cell invasion and metastasis by inhibiting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cervical carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 3155–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Wang, J.; Chang, D.; Lv, D.; Li, H.; Feng, H. Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA. Open Med. 2020, 15, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, N.P.G.; Gally, T.B.; Borges, G.F.; Campos, L.C.G.; Kaneto, C.M. Systematic review of circulating MICRORNAS as biomarkers of cervical carcinogenesis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Zhao, Y.; Caramuta, S.; Larsson, C.; Lui, W.-O. miR-205 expression promotes cell proliferation and migration of human cervical cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Chan, K.K.; Chu, D.K.; Wei, T.N.; Lau, L.S.; Ngu, S.F.; Chu, M.M.; Tse, K.Y.; Ip, P.P.; Ng, E.K. Oncogenic micro RNA signature for early diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 12, 2009–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhao, N.; He, M.; Zhang, K.; Bi, X. MiRNA-214 promotes the pyroptosis and inhibits the proliferation of cervical cancer cells via regulating the expression of NLRP3. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2020, 66, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Hu, Z. miR-214 down-regulates MKK3 and suppresses malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells. Gene 2020, 724, 144146, Erratum in Gene 2023, 877, 147538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Sun, Z.; Hu, K.; Tang, M.; Sun, S.; Fang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y. Over-expression of Hsa-miR-23b-3p suppresses proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human cervical cancer CasKi cells. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi = Chin. J. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 36, 983–989. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, M.; Ning, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Tang, S.; Mo, Z. MiR-26a-5p regulates proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion via inhibiting hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase like-2 in cervical cancer cell. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Sui, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Sun, H. MicroRNA-26a inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of cervical cancer cells by targeting protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA 1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 1426–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, W.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Y. MiR-27a-3p regulated the aggressive phenotypes of cervical cancer by targeting FBXW7. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Tang, H. B4GALT3 up-regulation by miR-27a contributes to the oncogenic activity in human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2016, 375, 284–292, Erratum in Cancer Lett. 2020, 493, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veena, M.S.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Basak, S.K.; Venkatesan, N.; Kumar, P.; Biswas, R.; Chakrabarti, R.; Lu, J.; Su, T.; Gallagher-Jones, M. Dysregulation of hsa-miR-34a and hsa-miR-449a leads to overexpression of PACS-1 and loss of DNA damage response (DDR) in cervical cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17169–17186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Wang, X.; Niu, X.; Jiao, R.; Li, X.; Wang, S. miR-34c-5p targets Notch1 and suppresses the metastasis and invasion of cervical cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerova, L.; Anton, M.; Bouchalova, P.; Jasickova, H.; Rak, V.; Jandakova, E.; Selingerova, I.; Bartosik, M.; Vojtesek, B.; Hrstka, R. The role of miR-409-3p in regulation of HPV16/18-E6 mRNA in human cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Antivir. Res. 2019, 163, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, H. LncRNA FAL1 upregulates SOX4 by downregulating miR-449a to promote the migration and invasion of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) cells. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Xiao, X.; Luo, Y.; He, Z.; Song, X. FEZF1 is an independent predictive factor for recurrence and promotes cell proliferation and migration in cervical cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotta, C.; Schlüter, T.; Ruiz-Perera, L.M.; Kadhim, H.M.; Tertel, T.; Henkel, E.; Hübner, W.; Greiner, J.F.; Huser, T.; Kaltschmidt, B. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of c-REL in HeLa cells results in profound defects of the cell cycle. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckmann, K.; Rörsch, F.; Geisslinger, G.; Grösch, S. Dimethylcelecoxib induces an inhibitory complex consisting of HDAC1/NF-κB (p65) RelA leading to transcriptional downregulation of mPGES-1 and EGR1. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.-m.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Luo, G.-w.; Li, H.-t.; Zhang, R.; Chen, B.-l.; Hua, W. A novel FoxM1-PSMB4 axis contributes to proliferation and progression of cervical cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, R.; Meng, S.; Wang, L.; Jia, Y.; Tang, F.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Fan, X.; Xiao, B. 6 Circulating miRNAs can be used as Non-invasive Biomarkers for the Detection of Cervical Lesions. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenborn, J.; Weikert, L.; Hangarter, B.; Stickeler, E.; Maurer, J. The use of micro RNA in the early detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kori, M.; Yalcin Arga, K. Potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cervical cancer: Insights from the meta-analysis of transcriptomics data within network biomedicine perspective. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, C.; Guan, H.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y. LncRNA DANCR promotes cervical cancer progression by upregulating ROCK1 via sponging miR-335-5p. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 7266–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LEE, Y.M.; LEE, S.; LEE, E.; SHIN, H.; HAHN, H.; CHOI, W.; KIM, W. Human kinesin superfamily member 4 is dominantly localized in the nuclear matrix and is associated with chromosomes during mitosis. Biochem. J. 2001, 360, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; He, W.; Shi, Y.; Gu, H.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, N.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Y. High expression of KIF20A is associated with poor overall survival and tumor progression in early-stage cervical squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.M.; Alfaro, A.; Roman-Basaure, E.; Guardado-Estrada, M.; Palma, Í.; Serralde, C.; Medina, I.; Juárez, E.; Bermúdez, M.; Márquez, E. Mitosis is a source of potential markers for screening and survival and therapeutic targets in cervical cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55975, Correction in PLoS ONE 2013, 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Deng, Z.; Shen, D.; Lu, M.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, G.; Qian, K.; Ju, L. DLGAP5 triggers proliferation and metastasis of bladder cancer by stabilizing E2F1 via USP11. Oncogene 2024, 43, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Cheng, H.; Fan, J.; Sun, T. Up-regulation of NCAPG mediated by E2F1 facilitates the progression of osteosarcoma through the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Transl. Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 2437–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lv, M.; Shi, Q.; Li, X. E2F1-mediated up-regulation of TOP2A promotes viability, migration, and invasion, and inhibits apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. J. Biosci. 2022, 47, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, D.; Quan, S.; Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, T. Human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein promotes proliferation and migration through the transcription factor E2F1 in cervical cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Former. Curr. Med. Chem. -Anti-Cancer Agents) 2021, 21, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, N.; Chen, H.; Qiao, L.; Zhao, W.; Chen, J.J. Role of Cdk1 in the p53-independent abrogation of the postmitotic checkpoint by human papillomavirus E6. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Lin, J.; Gao, J.; Lin, S.; Duan, S. Lovastatin inhibits the proliferation of human cervical cancer hela cells through the regulation of tp53 pathway by mir-92a-1-5p. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 35, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Kagawa-Miki, L.; Ueda, N.; Shigemoto, K.; Yasukawa, M.; Kito, K. A mitotic kinase TOPK enhances Cdk1/cyclin B1-dependent phosphorylation of PRC1 and promotes cytokinesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 370, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-L.; Ying, T.-H.; Yang, S.-F.; Chiou, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Kao, S.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-H. MTA2 silencing attenuates the metastatic potential of cervical cancer cells by inhibiting AP1-mediated MMP12 expression via the ASK1/MEK3/p38/YB1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusty, B.K.; Das, B.C. Constitutive activation of transcription factor AP-1 in cervical cancer and suppression of human papillomavirus (HPV) transcription and AP-1 activity in HeLa cells by curcumin. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 113, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ding, L.; Bai, L.; Chen, X.; Kang, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, J. Folate receptor alpha is associated with cervical carcinogenesis and regulates cervical cancer cells growth by activating ERK1/2/c-Fos/c-Jun. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 491, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Lv, S.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, X. E2F transcription factor 1 elevates cyclin D1 expression by suppressing transcription of microRNA-107 to augment progression of glioma. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Mao, A.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Di, C.; Gan, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H. microRNA-16-5p enhances radiosensitivity through modulating Cyclin D1/E1–pRb–E2F1 pathway in prostate cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 13182–13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Smyth, G.K. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4288–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.; Lalansingh, C.M.; Babaran, H.E.; Wang, Z.; Prokopec, S.D.; Fox, N.S.; Boutros, P.C. VennDiagramWeb: A web application for the generation of highly customizable Venn and Euler diagrams. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braschi, B.; Denny, P.; Gray, K.; Jones, T.; Seal, R.; Tweedie, S.; Yates, B.; Bruford, E. Genenames. org: The HGNC and VGNC resources in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D786–D792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timalsina, P.; Charles, K.; Mondal, A.M. STRING PPI score to characterize protein subnetwork biomarkers for human diseases and pathways. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 10–12 November 2014; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, H.-H.; Ho, C.-W.; Ko, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.J.B.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Schilder, B.M.; Torre, D.; Duffy, M.E.; Keenan, A.B.; Lachmann, A.; Feldmann, A.S.; Gundersen, G.W.; Silverstein, M.C. eXpression2Kinases (X2K) Web: Linking expression signatures to upstream cell signaling networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W171–W179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Xia, J. miRNet 2.0: Network-based visual analytics for miRNA functional analysis and systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W244–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagkouni, D.; Paraskevopoulou, M.D.; Chatzopoulos, S.; Vlachos, I.S.; Tastsoglou, S.; Kanellos, I.; Papadimitriou, D.; Kavakiotis, I.; Maniou, S.; Skoufos, G. DIANA-TarBase v8: A decade-long collection of experimentally supported miRNA–gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D239–D245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-D.; Lin, F.-M.; Wu, W.-Y.; Liang, C.; Huang, W.-C.; Chan, W.-L.; Tsai, W.-T.; Chen, G.-Z.; Lee, C.-J.; Chiu, C.-M. miRTarBase: A database curates experimentally validated microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D163–D169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y.; Ye, M.; Yao, L.; Wu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Deng, T.; Guo, F. RNADisease v4. 0: An updated resource of RNA-associated diseases, providing RNA-disease analysis, enrichment and prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1397–D1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, T.; Kern, F.; Backes, C.; Fehlmann, T.; Stöckel, D.; Meese, E.; Lenhof, H.-P.; Keller, A. miRPathDB 2.0: A novel release of the miRNA Pathway Dictionary Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D142–D147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.