Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (HCMs) are among the most common genetic disorders; however, they might be underdiagnosed. Sequencing core sarcomere gene panels remain the main diagnostic tool. We present the results of HCM genetic testing performed at Lithuania’s tertiary care center. All patients with diagnosed or clinically suspected HCM underwent next-generation panel sequencing. Of 204 patients, 34 (16.7%) received a genetic diagnosis. The most commonly affected genes were MYBPC3 and MYH7. Notably, two patients were found to have LEOPARD syndrome due to PTPN11 gene variants. Our results indicate that patients with an identified pathogenic variant were diagnosed with HCM at a younger age and exhibited a more severe phenotype (greater septal wall thickness), although no clear correlation with family history was observed. In addition, four novel MYBPC3 variants, c.3467dup, c.1503C>G, c.2610dup, and c.1251del, were identified.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death worldwide. In Lithuania, according to the data from the National Hygiene Institute, cardiovascular diseases account for 52.7% of all causes [1]. This number is one of the highest in Europe, as Europe’s average is 32.7% [2]. This highlights the need for a closer look at the underlying structure of these disorders. From a genetic perspective, the largest contribution to disease risk comes from polygenic risk variants. These remain difficult to interpret, as not all of them have been identified; their individual effect sizes are uncertain, and interactions between genetic variants are still poorly understood. Monogenic variants are easier to interpret but are much rarer in the general population.

Possibly the first description in history of HCM was in 1958 by Sir Russell Brock, who presented three cases of pulmonary stenosis due to chronic pressure overload, which manifested as left ventricular outflow tract hypertrophy [3]. In 1961, it was recognized as a distinct disease and was given the name idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis [4]. Today, the European Society of Cardiology describes HCM as “left ventricular wall thickness ≥ 15 mm in any myocardial segment that is not explained solely by loading conditions” [5]. Many studies have reported a disease frequency of 1 in 500 people. These studies were based on screening large cohorts with heart ultrasound or heart magnetic resonance [6]. A number of other studies looked at health record data and found a much lower frequency, about 1 in 2000. This suggests that many cases are underdiagnosed and may lack appropriate health management.

In 2014, the European Society of Cardiology reported that genetic testing identifies pathogenic variants in sarcomere genes in approximately 40–60% of HCM cases, 5–10% are syndromic cases, and 25–30% remain of unknown origin [7]. An increasing number of genetic diagnoses can be expected as more HCM-related genes are discovered and genetic testing technologies continue to improve. However, in 2020, A. Butters reported a genetic testing yield of about 32% in HCM cases [8]. More recent studies have shown even lower yields: L.M. Dellefave-Castillo reported 22.1% from 2596 cases [9], and J. Hathaway reported 26.8% from 1376 cases [10]. Comparisons between studies may be challenging, as patient selection criteria and variant pathogenicity assessment methods (i.e., which guidelines were used) may differ. Consequently, the true prevalence and genetic landscape of HCM remain difficult to define, and considerable uncertainty persists regarding the underlying causes of many cases. Therefore, in this study, we aim to analyze the genetic profile and clinical characteristics of the most common monogenic heart disorder, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, in a tertiary university hospital in Lithuania.

2. Results

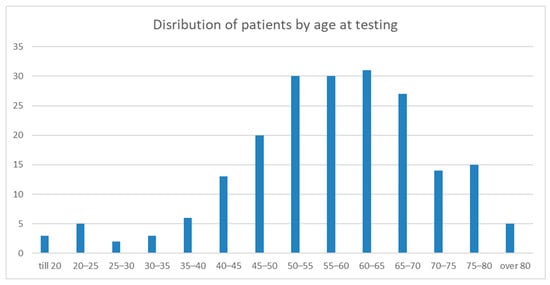

A total of 204 patients underwent genetic testing for HCM. The mean age at testing was 57.49 ± 13.68 years (range 18–86) (Figure 1). The study cohort consisted of 142 males (69.6%) and 62 females (30.4%). The main clinical parameters are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The graph shows patient distribution by age at which they were tested for HCM. The Y-axis shows the age group. The X-axis shows the patient number.

Table 1.

Main clinical parameters studied.

When comparing the genders, females were significantly older at the time of testing than males (median age 63.87 vs. 54.72 years, p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test). A pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant was detected in 39 patients (19.9%), while 165 patients (80.9%) had no variants identified. Likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants were reevaluated according to the newest gene-specific guidelines: In five cases, variant classification was downgraded to variants of unknown clinical significance; thus, they were subsequently regrouped to negative cases. The final proportion of positive cases was 16.7%.

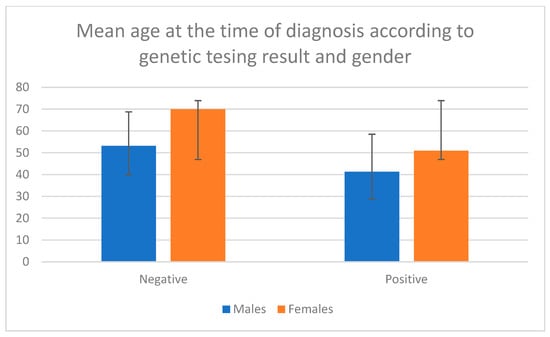

Patients with a detected variant were significantly younger at the time of diagnosis than those without a variant (median age 44 vs. 56 years, p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test). This trend was consistent across both genders: males with a pathogenic variant (n = 24) had a mean age at diagnosis of 41.33 ± 15.55 years compared to 53.81 ± 13.24 years in males without a variant, while females with a pathogenic variant (n = 10) had a mean age at diagnosis of 50.90 ± 17.13 years compared to 62.96 ± 12.55 years in those without a variant (Figure 2). A statistically significant difference was observed, with females being older in the group with no variant detected but not in the group with a pathogenic variant (p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test). The frequency of detected pathogenic variants did not differ significantly between males and females (Chi-square test, p = 0.892).

Figure 2.

Mean age at the time of diagnosis according to genetic testing results and gender. Negative means no pathogenic variant was detected. Positive means a pathogenic variant was detected.

Patients with a pathogenic variant detected had, on average, greater MWT (20.61 ± 5.94 vs. 18.69 ± 4.47 mm; p = 0.053) but lower LVMi (106.53 ± 3 5.42 vs. 115.84 ± 37.01; p = 0.133), according to the Mann–Whitney U test.

The frequency of affected family members and the presence of symptoms at the time of testing did not differ significantly between patients with and without pathogenic variants. An overall positive family history was observed in 20.4% of analyzed cases: 28.1% of individuals with a pathogenic variant and 18.9% of those without one. Symptoms were present in 82% of the analyzed patients: in 81.2% of those with a pathogenic variant and in 82% of those without one. Interestingly, patients with a confirmed genetic cause had lower body mass index (BMI: 26.74 ± 5.07 vs. 31.31 ± 22.13, p = 0.004, Mann–Whitney U test). BMI was not correlated with either LVMi or MWT (Spearman’s correlation, p > 0.05).

Considering unfavorable outcomes of HCM, we tended to see more in the genotype-positive group, as more patients needed a reduction of the heart septal wall (17.6% vs. 9.4%), and more cases of cardioverter implantations (14.7% vs. 10.1%). Thus, differences were observed but were not statistically significant.

MYBPC3 was the most frequently identified gene among patients with a detected causative variant (N = 20, 58.8%). Other affected genes were as follows: MYH7 (N = 11, 32.4%), PTPN11 (N = 2, 5.9%), and TNNI3 (N = 1, 2.9%). All analyzed patients were affected by isolated HCM. We did not expect to find PTPN11 gene pathogenic variants, as they usually cause Noonan or other related syndromes. At the first genetic consultation, no dysmorphic features or congenital anomalies were noted. Upon phenotype review, multiple lentigines were determined in two patents. After discussion with the medical team, LEOPARD syndrome (MIM 176876) was assigned in both cases. These patients had regular sun exposure in their professions, which likely masked suspicion of the syndrome earlier.

Patients with MYBPC3 gene-causative variants were diagnosed with HCM earlier than those with MYH7 (33.59 ± 15.68 vs. 43.10 ± 18.40). They also had greater MWT (23.08 ± 6.30 vs. 19.20 ± 6.09) and greater LVMi (115.24 ± 40.54 vs. 93.14 ± 20.69), although these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2). No apparent statistical differences (Chi square) were determined in the family history (5 vs. 3, p = 0.077), the presence of symptoms at testing (16 vs. 7, p = 0.713), or gender between patients (males 77.3% vs. 60.0%, p = 0.314) with causative variants in MYBPC3 or MYH7 genes.

Table 2.

Patient data distribution with respect to MYBPC3 and MYH7 variants.

All detected variants are presented in Table 3. Despite repeated variants, none of the patients were known to be related. Seven cases were found with MYBPC3 variant c.1505G>A and four cases with MYBPC3 variant c.3697C>T, while other variants were less frequent. When analyzing the distribution of detected variants, we noted that all MYBPC3 variants affected exon 15–33, whereas MYH7 variants were more widely dispersed. Nine variants of MYH7 were in the myosin motor domain and three in the coiled coil domain. No significant differences in clinical parameters were found when comparing recurrent variants to others or comparing affected domains.

Table 3.

Variants detected in our cohort.

3. Discussion

We analyzed patients tested at the Hospital of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kauno Klinikos, a single center for genetic causes of HCM. We achieved a diagnostic yield of 16.7%, which is lower than in other studies [7,8,9,10]. If we exclude non-sarcomeric genes (like PTPN11), yield decreases to 15.7%. Based on recently published studies, there is a recent tendency to report lower diagnostic yields than previously thought. Comparison with these studies is challenging, as they differ in clinical selection criteria, tested gene panels, and variant interpretation guidelines. Some studies also included other cardiovascular genes, such as SCN5A and RYR2, whose variants do not necessarily explain the HCM phenotype [10]. In our study, we focused only on genes that are clearly related to HCM. Our lower diagnostic yield may also be related to overlapping phenotypes between HCM and other, more common cardiac disorders, such as severe arterial hypertension or valvular disease.

As expected, in our study, patients with an identified genetic cause of HCM were diagnosed earlier and had more pronounced MWT. This is in line with previously published studies, which have demonstrated that carriers of pathogenic variants in sarcomeric genes present with more severe disease and experience more major cardiac events [11]. However, multiple studies have shown that there is no clear correlation between the specific causative gene and the cardiac phenotype. We also noted that females in our study were diagnosed, on average, later with HCM compared to males. Terauchi Y. et al. also reported that females are usually diagnosed later but present with a more severe phenotype [12]. The same observation was made by Preveden A. et al. [13]. Looking globally, it is noted that males have a higher prevalence not only of HCM but also of myocarditis and ischemic heart disorders [14]. It is unknown whether male gender has biological predisposition regarding developing HCM or whether it is biased by different cardiac screening approaches or patients’ behavior towards seeking medical help [15]. These findings suggest that females might require a different clinical approach for early HCM detection.

Our results showed an association between pathogenic variants and patients’ BMI. This suggests that patients with higher BMI have a cardiac phenotype similar to that seen in genetically determined HCM. However, BMI was not associated with MWT, LVMi, symptoms, or other clinical parameters, indicating that this could be an incidental finding.

As mentioned, we have identified pathogenic variants in the PTPN11 gene that are causative for LEOPARD syndrome. This syndrome usually presents with multiple lentigines, cardiac abnormalities, short stature, dysmorphic features, and other clinical signs [16]. Both of our patients carried variants affecting the same codon, 468, which has previously been reported in LEOPARD syndrome patients [17]. Based on the genetic test results and the presence of multiple lentigines, the diagnosis of this syndrome was established in our patients. Our gene panel included more genes than is usually recommended for isolated cases. According to the literature, the PTPN11 gene is typically excluded from panels [18,19,20]. However, considering that such syndromes can have variable expression and that cardinal features (e.g., dysmorphic traits) may diminish later in life, including syndromic HCM genes (phenocopies) in gene panels is valuable. This approach proved useful in our patients, who presented without short stature or dysmorphic features. It is also important to note that, in LEOPARD syndrome, HCM penetrance is approximately 80%, which is comparable to that observed for sarcomeric genes [21].

The most commonly affected genes in our study were MYBPC3 and MYH7. Findings across multiple studies are similar [22]. In our study, we did not find any differences regarding age of onset, affected family members, MWT, or other parameters, suggesting limited impact of genotype on disease prognosis. Other studies have also reported no significant differences [23]. Patients with MYBPC3 variants can be divided into two main groups: with truncating or with missense variants. As MYBPC3 causes HCM through haploinsufficiency, we could expect a more severe phenotype with truncating variants. However, studies have shown no substantial impact on clinical presentation, likely due to the unclear pathomechanism of missense variants [11]. Similarly, our MYBPC3-positive patients did not demonstrate major phenotypic differences. The MYBPC3 variants c.3467dup, c.1503C>G, c.2610dup, and c.1251del have not previously been described in the literature or clinical databases. They were classified as pathogenic due to their rarity in population databases and their predicted deleterious nature.

In our study, all MYBPC3 variants were located in exons 15–33. Other studies have not reported clustering of truncating variants [21]. However, it was demonstrated that missense variants tend to affect the C3, C6, and C10 domains [21]. In our cases, MYBPC3 variants affected the C3 and C8 domains compared to the sequence published by Carrier L et al. [24]. C3–C6 are the central domains participating in binding to other sarcomere proteins [25] and C8–10 anchor to the titin [26]. It is important to note that 32% of our patients with a positive MYBPC3 finding harbored the p.Arg502Gln variant. In previously published studies, the most frequent variant is p.Arg502Trp, which accounts for approximately 1.5–3% of cases [27]. Our identified p.Arg502Gln variant is also relatively frequent and has previously been reported in cohorts from Poland [28], Jordan [29], and China [30].

MYH7 causes HCM through a different mechanism: a dominant-negative of poisonous polypeptide. Incorporation of the modified protein into the sarcomere leads to functional changes. There are many different variants in the MYH7 gene that can lead to HCM through various protein changes, in most cases leading to an increased number of myosin heads available to interact with actin [31]. For example, the variant p.Gly256Glu in the literature is described as more benign than others, with a lower likelihood of sudden cardiac death. Nevertheless, it is also described in pediatric patients with expressed phenotype [32]. Our patient with this variant presented with disease at 53 years old, with no affected family members (possibly due to reduced penetrance). Therefore, an individual MYH7 genotype may not provide an accurate prognosis. It is speculated that variants in myosin motor regions can be severe [33]. This is supported by variants reported in databases, as more pathogen variants are within codons 167–931 [34]. Our three cases are outside this region (2x p.Thr1377Met; p.Arg1420Gln), in the coiled coil domain. However, these cases also did not differ significantly from others. These variants are not novel and well described in the literature.

Our study is limited by the small sample size, and thus may not reach the necessary statistical power. Not all possible confounding factors were analyzed, as there are many clinical situations that can cause left ventricular hypertrophy, such as intensive training, untreated long-going arterial hypertension, etc. Also, not all patients selected for genetic testing met the required criteria for HCM diagnosis.

4. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted between 2019 and 2024 in the Hospital of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kauno Klinikos, Genetics and Molecular Medicine department. The study was approved by the Kaunas Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (No. BE-2-63). Data were collected from electronic health records and from patients who were consulted due to diagnosed or clinically suspected HCM (confirmed by heart ultrasound and/or heart MRI). Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 years or older at the time of genetic consultation, echocardiography or cardiac MRI performed, and HCM diagnosed or suspected by a multidisciplinary medical team consisting of a clinical geneticist and cardiologists. The cohort consisted of patients who had had an HCM diagnosis for years, as well as those who were newly diagnosed. Data on symptoms, age at onset, laboratory and instrumental findings, complications such as atrial/ventricular fibrillation, treatments such as cardioverter/pacemaker implantation, and septal wall reduction (myectomy or alcohol ablation) were collected. Maximum wall thickness (MWT) of the left ventricle of the heart, left ventricular mass indexed LVMi, and heart ejection fraction (EF) were determined by the first available heart MRI scan. The MRI scans were performed on a 3T magnetic resonance imaging scanner with an 18-channel cardiac coil (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Images were acquired during an expiratory breath hold with ECG gating. In case MRI was not performed (or no data were accessible), heart ultrasound parameters were used. Two-dimensional (2D) transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) at rest was performed by an experienced echocardiographer using a diagnostic ultrasound system (EPIQ 7, Phillips Ultrasound, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA). All measurements were performed according to the existing guidelines. Family history was considered positive if the first-degree relatives had sudden cardiac death before the age of 60 years, or if there were known cases of HCM in the family.

Patients’ DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using the DNA extraction system QIA symphony (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) with the reagent kit DNA midi Kit or with QIcube (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), with the reagent QIAmp DNA blood Mini Kit. DNA purity was measured with Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using dsDNA HS Assay kit reagents. All patients underwent genetic testing using the Sistemas Genómicos (Valencia, Spain) Cardio-GeneSGKit library preparation kit and the Illumina NextSeq 550 system (San Diego, CA, USA). The library kit gene list changed during the period of analysis, but without compromising the core analysis genes. The gene lists are in the Supplementary Materials (List S1—for older panel, List S2—newest panel). All laboratory procedures were carried out according to the manufacturers’ manuals. The enrichment targeted all the genes associated with hereditary cardiovascular disorders, with an average sequencing depth of 200×. Samples that did not reach the target average depth were re-sequenced until the required depth was achieved. Most genes were entirely covered. Only coding exons and 20 bp of intron–exon boundaries were analyzed and reported. Sequencing fragment alignment, quality evaluation, variant calling, and gene variant interpretation were performed using the Sistemas Genomics (provided with the library kit) online platform GeneSystems. Low-quality variants (coverage < 10×, allele balance < 20%, Phred < 20) were removed. We selected only those genes for analysis that showed evidence of causing HCM by PanelApp: ACTC1, ACTN2, ALPK3, CACNA1C, CSRP3, FHL1, FHOD3, FLNC, GLA, LAMP2, MYBPC3, MYH7, MYL2, MYL3, PLN, PRKAG2, TBX20, TNNC1, TNNI3, TNNT2, TPM1, TRIM63, and TTR [18]. Firstly, variants were classified according to the ACMG/AMP 2015 guidelines [35]. Because the study is retrospective, variant interpretation criteria varied between periods, so we reinterpreted variants according to the newest gene specific recommendations from ClinGen [36,37]. Variants of unknown clinical significance were not included in this analysis; however, clinically relevant variants were reported to the patients.

Statistical data were collected in a Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS 26.0 software. All data were checked for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. As data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used as appropriate based on data type: Chi square, Mann–Whitney U test, and Spearmen test.

5. Conclusions

Genetic testing in Lithuanian HCM patients revealed that MYBPC3 and MYH7 are the most frequently affected genes, with several novel variants identified. Patients with pathogenic variants were diagnosed earlier and exhibited a more severe phenotype, highlighting the value of genetic screening in HCM management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010221/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.U., E.E. and M.Š.; methodology, R.U., E.E. and M.Š.; validation, M.Š., R.J. and K.A.; formal analysis, M.Š., R.J. and K.A.; investigation, M.Š., R.J. and K.A.; resources, M.Š., R.J., K.A. and J.A.; data curation, M.Š., R.J., K.A., E.T.-S. and J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Š.; writing—R.U. and E.E.; supervision, R.U.; project administration, R.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Kaunas Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (No. BE-2-63. Approval date: 28 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

As approved by our regional ethics committee, some retrospective data were allowed to be collected without written consent (as no personal data were collected). Informed consent was obtained from other subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter defibrillator |

| MWT | Heart maximum wall thickness |

| LVMi | left ventricular mass indexed |

| VF/VT | Ventricular fibrillation/tachycardia |

References

- Lietuvos Gyventojai (2022 m. Leidimas). Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/lietuvos-gyventojai-2022/mirtingumas/gyventoju-mirties-priezastys (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Causes of Death Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Causes_of_death_statistics (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Turley, K. Lord Brock—The direct approach. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1989, 48, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, A.; Vassiliou, V.; Cooper, R.; Raphael, C. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy—Past, Present and Future. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiomyopathies of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massera, D.; Sherrid, M.V.; Maron, M.S.; Rowin, E.J.; Maron, B.J. How common is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy… really?: Disease prevalence revisited 27 years after CARDIA. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 382, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.M.; Anastasakis, A.; Borger, M.A.; Borggrefe, M.; Cecchi, F.; Charron, P.; Hagege, A.A.; Lafont, A.; Limongelli, G.; Mahrholdt, H.; et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2733–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, A.; Bagnall, R.D.; Ingles, J. Revisiting the Diagnostic Yield of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genetic Testing. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, e002930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellefave-Castillo, L.M.; Cirino, A.L.; Callis, T.E.; Esplin, E.D.; Garcia, J.; Hatchell, K.E.; Johnson, B.; Morales, A.; Regalado, E.; Rojahn, S.; et al. Assessment of the Diagnostic Yield of Combined Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmia Genetic Testing. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathaway, J.; Heliö, K.; Saarinen, I.; Tallila, J.; Seppälä, E.H.; Tuupanen, S.; Turpeinen, H.; Kangas-Kontio, T.; Schleit, J.; Tommiska, J.; et al. Diagnostic yield of genetic testing in a heterogeneous cohort of 1376 HCM patients. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudurachi, B.-S.; Zăvoi, A.; Leonte, A.; Țăpoi, L.; Ureche, C.; Bîrgoan, S.G.; Chiuariu, T.; Anghel, L.; Radu, R.; Sascău, R.A.; et al. An Update on MYBPC3 Gene Mutation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terauchi, Y.; Kubo, T.; Baba, Y.; Hirota, T.; Tanioka, K.; Yamasaki, N.; Furuno, T.; Kitaoka, H. Gender differences in the clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by cardiac myosin-binding protein C gene mutations. J. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preveden, A.; Golubovic, M.; Bjelobrk, M.; Miljkovic, T.; Ilic, A.; Stojsic, S.; Gajic, D.; Glavaski, M.; Maier, L.S.; Okwose, N.; et al. Gender Related Differences in the Clinical Presentation of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy—An Analysis from the SILICOFCM Database. Medicina 2022, 58, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethemiotaki, I. Global prevalence of cardiovascular diseases by gender and age during 2010–2019. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2023, 8, e196–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, F.M.; Oliveira, M.; Belo, A.; Correia, J.; Azevedo, O.; Morais, J.; Portuguese Registry of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Investigators. The sex gap in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelb, B.D.; Tartaglia, M. Noonan Syndrome with Multiple Lentigines; GeneReviews® [Internet]; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, S.; Torreri, P.; Tinti, M.; Stella, L.; Bocchinfuso, G.; Flex, E.; Grottesi, A.; Ceccarini, M.; Palleschi, A.; Cesareni, G.; et al. Diverse driving forces underlie the invariant occurrence of the T42A, E139D, I282V and T468M SHP2 amino acid substitutions causing Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 2018–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Williams, E.; Foulger, R.E.; Leigh, S.; Daugherty, L.C.; Niblock, O.; Leong, I.U.S.; Smith, K.R.; Gerasimenko, O.; Haraldsdottir, E.; et al. PanelApp crowdsources expert knowledge to establish consensus diagnostic gene panels. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.R.; Ho, C.Y.; Elliott, P.M. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Established and emerging implications for clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2727–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.G.; Romero, L.d.l.H.; Fernández, A.; Peña-Peña, M.L.; Mora-Ayestaran, N.; Basurte-Elorz, M.T.; Larrañaga-Moreira, J.M.; Reyes, I.C.; Villacorta, E.; Valverde-Gómez, M.; et al. Redefining the Genetic Architecture of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Role of Intermediate-Effect Variants. Circulation 2025, 152, 1060–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, A.S.; Thompson, A.D.; Glazier, A.A.; Hafeez, N.; Kabani, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Yob, J.M.; Woolcock, H.; Mazzarotto, F.; Lakdawala, N.K.; et al. Spatial and Functional Distribution of MYBPC3 Pathogenic Variants and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, C.G.; Ho, C.Y. Genetic Testing in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 212, S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velicki, L.; Jakovljevic, D.G.; Preveden, A.; Golubovic, M.; Bjelobrk, M.; Ilic, A.; Stojsic, S.; Barlocco, F.; Tafelmeier, M.; Okwose, N.; et al. Genetic determinants of clinical phenotype in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, L.; Bonne, G.; Bahrend, E.; Yu, B.; Richard, P.; Niel, F.; Hainque, B.; Cruaud, C.; Gary, F.; Labeit, S.; et al. Organization and Sequence of Human Cardiac Myosin Binding Protein C Gene (MYBPC3) and Identification of Mutations Predicted to Produce Truncated Proteins in Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 1997, 80, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, C.Y.; Schmidt, A.V.; Chinthalapudi, K.; Stelzer, J.E. Bringing into focus the central domains C3-C6 of myosin binding protein C. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1370539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howarth, J.W.; Ramisetti, S.; Nolan, K.; Sadayappan, S.; Rosevear, P.R. Structural Insight into Unique Cardiac Myosin-binding Protein-C Motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 8254–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Fernández, A.I.; Espinosa, M.Á.; Cuenca, S.; Lorca, R.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Tamargo, M.; García-Montero, M.; Gómez, C.; Vilches, S.; et al. Founder mutation in myosin-binding protein C with an early onset and a high penetrance in males. Open Heart 2021, 8, e001789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudziński, T.; Selmaj, K.; Drozdz, J.; Krzemińska-Pakuła, M. Selected mutations in the myosin binding protein C gene in the Polish population of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Kardiol. Pol. 2008, 66, 821–825; discussion 826–827. [Google Scholar]

- Azab, B.; Aburizeg, D.; Shaaban, S.T.; Ji, W.; Mustafa, L.; Isbeih, N.J.; Al-Akily, A.S.; Mohammad, H.; Jeffries, L.; Khokha, M.; et al. Unraveling the genetic tapestry of pediatric sarcomeric cardiomyopathies and masquerading phenocopies in Jordan. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, T.; Piao, C.; Li, X.; Guo, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Du, J. Screening Mutations of MYBPC3 in 114 Unrelated Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy by Targeted Capture and Next-generation Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawana, M.; Spudich, J.A.; Ruppel, K.M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Mutations to mechanisms to therapies. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 975076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fananapazir, L.; Epstein, N.D. Genotype-phenotype correlations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Insights provided by comparisons of kindreds with distinct and identical beta-myosin heavy chain gene mutations. Circulation 1994, 89, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, M.; de Brouwer, R.; Hassanzada, F.; Schoemaker, A.E.; Schmidt, A.F.; Kooijman-Reumerman, M.D.; Bracun, V.; Slieker, M.G.; Dooijes, D.; Vermeer, A.M.; et al. Penetrance and Prognosis of MYH7 Variant-Associated Cardiomyopathies. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.; Mazzarotto, F.; Whiffin, N.; Buchan, R.; Midwinter, W.; Wilk, A.; Li, N.; Felkin, L.; Ingold, N.; Govind, R.; et al. Quantitative approaches to variant classification increase the yield and precision of genetic testing in Mendelian diseases: The case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, E.F.; Azzariti, D.R.; Babb, L.J.; Berg, J.S.; Biesecker, L.G.; Bly, Z.; Buchanan, A.H.; DiStefano, M.T.; Gong, L.; Harrison, S.M.; et al. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen): Advancing genomic knowledge through global curation. Genet. Med. 2025, 27, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Genome Resource. Available online: https://cspec.genome.network/cspec/ui/svi/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.