Abstract

There is currently little information on the immune profile of adult type 1 diabetes patients diagnosed with periodontal disease. The aim of this systematic review is to bring together the known evidence of which inflammatory markers, measured in salivary flow or gingival crevicular fluid and serum blood, are present in both pathologies. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analys guidelines, we systematically searched in the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Library databases for studies on the associations of different chemokines with type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. From a total of 703 patients, of which 526 were patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and 215 were controls without diabetes, multiple inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin 8, which showed higher concentrations in the crevicular fluid in several studies of type 1 diabetes patients and a greater severity in its effects on the periodontal status, as well as osteoprotegerin and tumor necrosis factor alpha, have been found elevated in diabetic patients with poor periodontal control. The results suggest that interleukin 8, tumor necrosis factor alpha and osteoprotegerin may be promising novel biomarkers of type 1 diabetes mellitus, and may also indicate the susceptibility profile in these individuals for the worsening of the patient’s periodontal status.

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), as a chronic autoimmune disease, is characterized by the selective loss of insulin-producing beta cells (β cells) mediated by T cells [1,2]. The progressive destruction of these pancreatic beta cells mediated by an altered immune response is characteristic of T1DM. This destruction leads to a deficiency in insulin production resulting in hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. However, its etiology is still unclear; it seems to be the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors, including some viruses. The nature of autoimmunity involves the dysfunction of the innate and acquired responses [3,4,5,6].

The role of the inflammatory effect of certain proinflammatory cytokines concentrated in pancreatic beta cells supports the thesis of their contribution to the development of type 1 diabetes [5]. It is still under debate what the sequence is and what the implications of the genetic side are that could induce cell destruction [7,8].

There seem to be two types of type 1 diabetes: autoimmune (where there is a severe deficit of insulin secretion due to the damage of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas) and idiopathic (where no autoimmune mechanisms are involved, and the cause is currently unknown) [8,9].

Periodontal disease is a pathology of multifactorial etiology where certain periodontopathogenic bacteria alter the balance of the microbiome and infect the tissues in such a way as to trigger an inflammatory response [10]. Depending on the inflammatory response triggered in the individual, it can remain as only an acute inflammation limited to the soft tissues (gingivitis) or become chronic and include the destruction of the supporting tissues [11,12,13]. The hyperglycemic state and hyperlipidemia in turn activate glycation end products (AGEs), whose receptors are on monocytes, endothelial cells and macrophages, which secrete interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [14,15].

Meanwhile, several studies with diabetic patients have shed some light on the role of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontitis [16,17,18,19]. Early diagnosis of periodontal disease in patients with T1DM is a crucial key to improve the patient’s systemic health, limiting the damaged caused by the hyperglycemic state [8,20,21,22].

Clinical studies have provided evidence that higher levels of proinflammatory mediators within the gingival tissues of diabetic patients, like IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANK-L)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio and oxidative stress play a significant role in the increased periodontal destruction [16]. This was also supported by studies using animal models or cell cultures exposed to high glucose levels [23].

Linhartova et al. found that interleukin 8 (IL-8), a C-X-C motif (CXC) member of the cytokine family, is one of the major chemokines and activators of neutrophils with the interaction of CXCR1 (C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1) and CXCR2 (C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2) [24]. IL-8 is related to the initiation and amplification of acute inflammatory reactions and is secreted by various types of cells. Chemokines and neutrophils have been previously associated or implicated with the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. However, it is not clear what the association itself is [20]. The levels of IL-8 in oral keratinocytes, and cells of the gingival epithelium, crevicular fluid, plasma and serum have been ambiguous in patients with T1DM and periodontitis; authors such as Linhartova found an association between IL-8 and patients with periodontitis [24,25].

Salivary biomarkers have been used for the early diagnosis of several diseases, including diabetes, specifically immunoglobulin A (IG-A) [26,27]. In addition, other cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [8,28] have also been associated with an immune response influenced by chronic inflammation, which represents a complication in diabetic patients. Specifically, immunoglobulin 6 (IG-6) and TNF-α are potent proinflammatory cytokines that are significantly increased in patients with gingivitis and type 1 diabetes. At the plasma level, other mediators have been studied, such as IL-8, which some authors have found in higher concentrations in patients with type 1 diabetes [24].

The mechanisms by which diabetes affects periodontitis are not fully understood; however, it is known that diabetes is correlated with an improvement in the progression of periodontitis in part due to the increased inflammatory response. A deeper understanding of the two-way relationship between periodontal diseases (PD) and diabetes will contribute decisively to designing new treatment strategies and guiding future lines of research. For that reason, the main objective of our study was to review the current evidence of the role of cytokines, chemokines or immune biomarkers in the bidirectional relationship between type 1 diabetes and periodontal disease.

2. Results

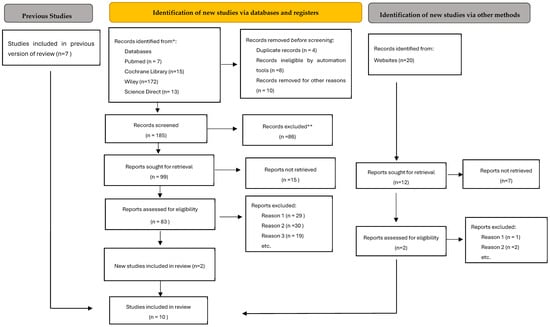

From a total of 207 articles, after eliminating duplicates and articles whose title and abstract did not fit our inclusion criteria, a total of 10 articles were chosen for review. The flow chart is described in Figure 1 according to the criteria of Page et al. [29]. The total number of studies were eight cross-sectional studies (Table 1) and two cohort studies (Table 2), and specifically, one of which had a 50-year follow-up (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. Reason 1: in vitro studies. Reason 2: not specifying whether and when any previous periodontal treatment was performed on the patient in a way that could alter the results obtained. Reason 3: the population included patients with type 2 diabetes. * Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). ** If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Table 1.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies.

Table 2.

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies.

Table 3.

Main results for the studies included.

3. Discussion

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is an inflammatory disease with autoimmune characteristics that is experiencing an exponential increase in its prevalence worldwide [13]. Periodontal disease is the sixth most common systemic complication associated with type 1 diabetic patients [16]. A study carried out in 2019 by Shinjo et al. [36] on a cohort of 170 patients with a diagnosis of T1DM who were over 50 years old and belonged to the Joslin Medalist group aimed to discover the protective factors that this population presented in terms of ocular, renal and neurological complications, compared to the rest of the diabetic patients in the USA. This study found that the prevalence of severe periodontal disease was 13.5%, significantly lower than the overall rate of 23.3% in the US for patients aged 65–74 years in the NHANES (2009–2012). However, this could also be related to the narrow range of HbA1c exhibited by the Medalists, with very good glycemic control (mean 7.15%) compared to the national mean of HbA1c in T1DM (8.2% overall and 7.6% in those ≥50 years age) [36].

Current investigations have proposed that one of the biological mechanisms that occurs in diabetic patients with a chronic hyperglycemic state results in the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGE) through the irreversible non-encapsulated formation of proteins and lipids. This results in the loss of functionality of proteins, leading to molecules that stimulate the inflammatory mediators through the interaction with AGE receptors (RAGE).

On the one hand, the receptors of triggers of AGE receptors such as monocytes, endothelial cells and macrophages are associated with immune and non-immune T1DM. These immune cells produce a significant increase in cytokines and the proinflammatory mediators interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, PGE-2 and TNF-α, which causes the destruction of periodontal tissues, because in the periodontium, there are numerous cells which express RAGE, like oral keratinocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages and monocytes. This interaction between AGE and AGE receptors will stimulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other osteolytic factors that will cause damage to the periodontal ligament and periodontal bone matrix [30,37]. On the other hand, hyperlipidemia also increases the amount of IL-1β and TNF-α [30].

The increase in IL-6 and TNF-α in synchrony promotes the increase in C-reactive proteins and the decrease in adiponectin, which will increase the insulin resistance characteristic of a diabetic patient. In fact, TNF-α amniotic acid together with increased IL-1β results in increased protein kinase C (PKC), the destruction of pancreatic β-cells and a synergistic increase in hyperlipidemia through lipid clearance, increased lipogenesis and decreased lipolysis.

The study by Shinjo et al. showed that serum IL-6, but not C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, is associated with an increased periodontitis severity in this group of periodontitis patients [36]. However, other researchers found an increased trend of CRP and HbA1c in type 1 adults, which reflects data from individuals with type 2 diabetes and type 1 pediatric patients (HbA1c data only) [1].

Specifically, according to Lappin et al., IL-6 is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine found in elevated circulating levels in poorly controlled T1DM patients and also appears to be related to periodontitis [37].

IL-8 is a major neutrophil chemoattractant and plays a key role in the induction and maintenance of inflammation. High levels of these cytokines have been detected in the gingival tissues of patients with periodontal disease and T1DM [24].

In relation to serum OPG, it is still not clear if it increases in cases of attachment loss and greater severity. Other studies conclude that the local concentration of RANK-L/OPG increases in healthy patients, patients with gingivitis and periodontitis. There are studies that state that the samples of control patients with the same periodontal situation are small and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about the effect of serum OPG in relation to the status and degree of PD [31].

Studies carried out in animal models have demonstrated higher levels of interleukin 23 (IL-23) and interleukin 17 (IL-17) in patients with type 1 diabetes, and in addition, the interferon (IFN) produced by T cells appears to be implicated in the destruction of Langerhans cell islets. In the same way, IL-17 is found in higher concentrations in patients with periodontitis [11,38]. Salivary biomarkers have been verified as a non-invasive diagnostic strategy. Our other preliminary analysis of saliva samples recovered from PD patients with distinct degrees of severity was performed to select the most informative panel of inflammatory mediators. We observed a significant increase in IL-1β,, IL-6 and interferon gamma (IFNγ) in the saliva of PD patients compared to age- and gender-matched healthy controls. In opposition, we observed the inverse phenotype with interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) and interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10) [39].

Among the plethora of markers, MMP-8 is also known as collagenase 2 or neutrophil collagenase and members of the MMP family have been studied extensively in oral fluids. MMP-8 is the main collagenase and is found in the inflamed gingiva of adults, being associated with the pathological destruction of the extracellular matrix. A recent review of 61 articles stated that MMP8 has the potential (alone or in combination with other inflammatory and microbiological markers) to serve as a diagnostic tool in periodontal and peri-implant disease [30,31,32].

Chronic hyperglycemia is related to the increased production of AGEs. These products compromise physiological and mechanical function resulting in a malfunctioning ECM (extracellular matrix), e.g., they suppress collagen production from periodontal and gingival ligament fibroblasts. In an in vivo study, they have also been shown to be increased in type 1 diabetes (AGE+). The hypothesis says that in diabetic patients, there are a greater number of local inflammatory biomarkers than in non-diabetic patients. This study evaluates the levels of MMP8, interleukin 8 (IL-8) and AGEs in GCF in type 1 diabetes with different glycemic levels compared to healthy controls [30]. Interleukin 8 has been identified as a chemotactic factor, produced by various cell types upon the stimulation and induction of neutrophils that release lysosomal enzymes. IL-8 levels in crevicular fluid have been found to be significantly higher in patients with chronic PD but decreased in those treated periodontally [30]. This is in line with other studies on crevicular fluid, where an increase was also found in patients with periodontitis with a higher degree of severity [37].

Duque et al. reported higher lipid parameters in type 1 diabetes patients compared to controls; however, they obtained similar results in red complexes, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6. On the other hand, another author who used protein analysis reported on eight proteins [33,35].

The immune system’s neutrophils, macrophages and monocytes are among the cells whose activities are compromised by diabetes mellitus (DM).

Gingival crevicular fluid changes in connection with immune cell activity, and modifications in the control of proteolytic production and modified inflammatory cytokine profiles have all been found in smokers’ studies. Smoking affects the immune system (delaying the migration and recruitment of neutrophils), the microbiota (the composition of subgingival biofilms varies with the increased prevalence of periodontal pathogens) and the healing capacity of the periodontium (higher collagenolytic activity coupled with fewer gingival blood vessels) [40].

Tobacco use is associated with a number of diseases and increases the risk of developing periodontitis. It has been shown that smokers suffer more periodontal disorders than non-smokers, and the impact of tobacco on periodontal tissues has been debated for decades [34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

It would be necessary to study a greater number of inflammatory biomarkers in different media, both minimally invasive, such as crevicular fluid or saliva, as well as more invasive media, such as blood samples. A correct periodontal evaluation should be carried out in these patients with standardized diagnostic criteria in order to compare different populations. The risk of taking records of deep pockets has been criticized in several studies, and healthy sites are therefore also necessary to compare results. The importance of these studies in the public health of the population is great, since in addition to periodontal involvement, a higher prevalence of neuropathies related to a greater increase in IgA or cardiovascular risk systematically associated with IL-6 and CPR have been recorded [36].

4. Materials and Methods

The study protocol for this systematic review was registered on the International Prospective of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), under number CRD42024565892.

This systematic review was conducted from 2010 to 2024, according to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines” (PRISMA) [41] using the databases MEDLINE via PubMed and Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Science Direct. The search was also conducted using the following journals: Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Journal of Periodontology and Periodontology 2000 via Wiley Online Library (2012 to present). The search strategy was as follows:

(((chemotactic cytokines[MeSH Terms]) OR (inflammation mediators[MeSH Terms]) OR (interleukins[MeSH Terms])) AND (periodontal disease[MeSH Terms]) AND (type 1 diabetes mellitus[MeSH Terms])).

To demonstrate intra- and inter-examiner reliability, two independent examiners (A.M./F.S.) were used and the Kappa coefficient test produced nearly perfect agreement (0.81–0.99) during the search and selection of the articles. Disagreements between these examiners were later resolved by agreement and based on the opinion of a third experienced researcher (M.R.)

PICO question: What inflammatory markers have been identified in adult patients with type 1 diabetes and periodontal disease?

The records were screened by the title, abstract and full text by two independent investigators. The studies included in this review matched all the predefined criteria according to PICOS at Table 4 (“Population”, “Intervention”, “Comparison”, “Outcomes” and “Study design”). A detailed search flow chart is presented in the Results section.

Table 4.

PICO strategy.

The eligibility criteria were organized, using the PICO method, as follows:

The inclusion criteria corresponding to the PICO questions were articles in English, Portuguese or Spanish; articles related to T1DM; and cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, cohort studies and randomized controlled clinical studies. The studies chosen were from 2010 to 2024 to rule out outdated study methodologies or diagnostic tests.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were articles without an abstract available; literature reviews and meta-analyses, expert opinions, letters to the editor, conference abstracts and animal studies; and studies investigating type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) exclusively. We also excluded inflammatory diseases, chronic liver disease or articles related to any treatment that may modify the study parameters, such as antibiotics, immunosuppressants or antiepileptic drugs. The pre-selected studies were excluded for several reasons, including the population being children or adolescents; the population being patients with type 2 diabetes and not specifying this in the title; and not specifying whether and when any previous periodontal treatment was performed on the patient in a way that could alter the results obtained.

4.1. Extraction of Sample Data

The data were collected by drawing up a results table, and the information was collected, taking into consideration the study design and aim, the eligibility criteria, the study population (with sample size and age group or average age), the duration in months or years of the study as well as the follow-up period, the outcome measures and the results.

4.2. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

To assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study had addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, or analysis, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance 2017 for each type of study (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort studies or randomized controlled trials) [42]. For each type of study, a different questionnaire was conducted using the answers Yes (Y), No (n), Unclear (UN) and Not Applicable (NA). Two independent examiners (A.M./P.J.) were used to demonstrate intra- and inter-examiner reliability. All cross-sectional studies responded positively to most of the bias test responses; only two questions were not answered positively, having a low risk of bias. The two cohort studies responded positively to all responses (Table 1 and Table 2).

5. Conclusions

Since type 1 diabetes is a disease with an etiology highly induced by the immune response, we believe that there is a deficit in knowledge specifically in adults, a field that has received little study, and not in children or adolescents. If we also add the fact of its association with periodontal disease, we will see that there are very few studies that evaluate the profile of inflammatory cytokines in these individuals.

The results suggest that IL-8, TNF-α and OPG may be promising novel biomarkers of T1DM and may also indicate the susceptibility profile in these individuals for the worsening of the patient’s periodontal status. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in longitudinal studies and explore the potential mechanisms underlying other biomarkers as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-23, IFNγ, IL-1RA and IP-10, as well as IL-10, IL-17, IL-33, RANK- L and their associations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.P.M., F.S. and M.R.; methodology, Á.P.M., P.L.-J., R.C. and M.R.; software, M.R.; formal analysis, B.R.-C. and P.L.-J.; investigation, Á.P.M., F.S. and M.R.; resources, R.C. and B.R.-C.; data curation, Á.P.M., M.R. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.P.M. and P.L.-J.; writing—review and editing, B.R.-C., F.S. and M.R.; visualization P.L.-J. and B.R.-C.; supervision, F.S. and M.R.; project administration, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Steigmann, L.; Maekawa, S.; Kauffmann, F.; Reiss, J.; Cornett, A.; Sugai, J.; Venegas, J.; Fan, X.; Xie, Y.; Giannobile, W.V.; et al. Changes in salivary biomarkers associated with periodontitis and diabetic neuropathy in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, E.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Ong, K.L.; Vos, T.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abd-Rabu, R.; et al. Diabetes mortality and trends before 25 years of age: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Geladari, E.; Tessier, C.M.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Diabetes type 1:Can it be treated as an autoimmune disorder? Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 22, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.A.; Wong, F.S.; Wen, L. Inflammasomes and Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 686956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y.; Dinarello, C.A.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. Targeting innate immune mediators in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavera, M.; Giannini, C.; Chiarelli, F. Prediction and Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicembrini, I.; Barbato, L.; Serni, L.; Caliri, M.; Pala, L.; Cairo, F.; Mannucci, E. Glucose variability and periodontal disease in type 1 diabetes: A cross-sectional study-The “PAROdontopatia e DIAbete” (PARODIA) project. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajita, M.; Karan, P.; Vivek, G.; Meenawat Anand, S.; Anuj, M. Periodontal disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus: Associations with glycemic control and complications: An Indian perspective. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2013, 7, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.; Rios-Carrasco, B.; Monteiro, L.; Lopez-Jarana, P.; Carneiro, F.; Relvas, M. Association between Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenbud, I.; Wilensky, A.; Almoznino, G. Periodontal Disease and Its Association with Metabolic Syndrome-A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunte, K.; Beikler, T. Th17 Cells and the IL-23/IL-17 Axis in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis and Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nibali, L.; Gkranias, N.; Mainas, G.; Di Pino, A. Periodontitis and implant complications in diabetes. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 90, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, S.; Loume, A.; Giannopoulou, C.; Papathanasiou, E.; Zekeridou, A. Investigating the Interplay: Periodontal Disease and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus-A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Losada, F.L.; Jane-Salas, E.; Sabater-Recolons, M.M.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Lopez-Lopez, J. Correlation between periodontal disease management and metabolic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic literature review. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2016, 21, e440–e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Gopalkrishna, P. Type 1 diabetes and periodontal disease: A literature review. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 56, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, T.; Konig, J.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Pink, C.; Meisel, P. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontol. 2000 2018, 78, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, D.; Shapira, L. An update on the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, H. Effects of statins on cytokines levels in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva and on clinical periodontal parameters of middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohr, J.; Barbaresko, J.; Neuenschwander, M.; Schlesinger, S. Bidirectional association between periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Ceriello, A.; Buysschaert, M.; Chapple, I.; Demmer, R.T.; Graziani, F.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Lione, L.; Madianos, P.; et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascones-Martinez, A.; Gonzalez-Febles, J.; Sanz-Esporrin, J. Diabetes and periodontal disease. Review of the literature. Am. J. Dent. 2014, 27, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicembrini, I.; Serni, L.; Monami, M.; Caliri, M.; Barbato, L.; Cairo, F.; Mannucci, E. Type 1 diabetes and periodontitis: Prevalence and periodontal destruction-a systematic review. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhartova, P.B.; Kavrikova, D.; Tomandlova, M.; Poskerova, H.; Rehka, V.; Dusek, L.; Izakovicova Holla, L. Differences in Interleukin-8 Plasma Levels between Diabetic Patients and Healthy Individuals Independently on Their Periodontal Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell-Bergeon, J.K.; West, N.A.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Liese, A.D.; Marcovina, S.M.; D’Agostino, R.B., Jr.; Hamman, R.F.; Dabelea, D. Inflammatory markers are increased in youth with type 1 diabetes: The SEARCH Case-Control study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2868–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligora, J.; Kusnierz-Cabala, B.; Pawlica-Gosiewska, D.; Gawlik, K.; Chomyszyn-Gajewska, M.; Pytko-Polonczyk, J. Salivary matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a biomarker of periodontitis in pregnant patients with diabetes. Dent. Med. Probl. 2023, 60, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Swensen, A.C.; Qian, W.J. Serum biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of type 1 diabetes. Transl. Res. 2018, 201, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, V.M.; Kennedy, A.D.; Panagakos, F.; Devizio, W.; Trivedi, H.M.; Jonsson, T.; Guo, L.; Cervi, S.; Scannapieco, F.A. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereti, M.; Roy, M.; Zekeridou, A.; Gastaldi, G.; Giannopoulou, C. Gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers in type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2021, 7, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, G.; Knuuttila, M.; Nieminen, P.; Vainio, O.; Hiltunen, L.; Raunio, T.; Niemela, O.; Hedberg, P.; Karttunen, R.; Tervonen, T. Serum osteoprotegerin and periodontal destruction in subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poplawska-Kita, A.; Siewko, K.; Szpak, P.; Krol, B.; Telejko, B.; Klimiuk, P.A.; Stokowska, W.; Gorska, M.; Szelachowska, M. Association between type 1 diabetes and periodontal health. Adv. Med. Sci. 2014, 59, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, C.; Joao, M.F.; Camargo, G.A.; Teixeira, G.S.; Machado, T.S.; Azevedo, R.S.; Mariano, F.S.; Colombo, N.H.; Vizoto, N.L.; Mattos-Graner, R.O. Microbiological, lipid and immunological profiles in children with gingivitis and type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2017, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksymenko, A.I.; Sheshukova, O.V.; Kuz, I.O.; Lyakhova, N.A.; Tkachenko, I.M. The Level of Interleukin-18 in the Oral Fluid in Primary School Children with Chronic Catarrhal Gingivitis and Type I Diabetes Mellitus. Wiad. Lek. 2021, 74, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, S.; Anik, A.; Cevik, O.; Abas, B.I.; Anik, A. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in type 1 diabetic children with gingivitis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 3623–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinjo, T.; Ishikado, A.; Hasturk, H.; Pober, D.M.; Paniagua, S.M.; Shah, H.; Wu, I.H.; Tinsley, L.J.; Matsumoto, M.; Keenan, H.A.; et al. Characterization of periodontitis in people with type 1 diabetes of 50 years or longer duration. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, D.F.; Robertson, D.; Hodge, P.; Treagus, D.; Awang, R.A.; Ramage, G.; Nile, C.J. The Influence of Glycated Hemoglobin on the Cross Susceptibility Between Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhartova, P.B.; Kastovsky, J.; Lucanova, S.; Bartova, J.; Poskerova, H.; Vokurka, J.; Fassmann, A.; Kankova, K.; Izakovicova Holla, L. Interleukin-17A Gene Variability in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Periodontitis: Its Correlation with IL-17 Levels and the Occurrence of Periodontopathic Bacteria. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 2979846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, M.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Gonçalves, M.; Salazar, F.; López-Jarana, P.; Silvestre, R.; Viana da Costa, A. Salivary IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 Are Key Biomarkers of Periodontitis Severity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinucci, L.; Coniglio, M.; Valenti, C.; Massari, S.; Di Michele, A.; Billi, M.; Bruscoli, S.; Negri, P.; Lombardo, G.; Cianetti, S.; et al. In vitro effects of alternative smoking devices on oral cells: Electronic cigarette and heated tobacco product versus tobacco smoke. Arch. Oral Biol. 2022, 144, 105550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI’s Systematic Reviews: Study selection and critical appraisal. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).