Abstract

The Klotho gene is recognized for its anti-aging properties. Its downregulation leads to aging-like phenotypes, whereas overexpression can extend lifespan. Klotho protein exists in three forms: α-klotho, β-klotho and γ-klotho. The α-klotho has two isoforms: a membrane-bound form, primarily in the kidney and brain, and a secreted klotho protein present in blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid. Klotho functions as a co-receptor for fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23), regulating phosphate metabolism. The membrane-bound form controls various ion channels and receptors, while the secreted form regulates endocrine FGFs, including FGF19 and FGF21. The interaction between β-klotho and FGF21 in muscle is critical in the development of sarcopenic obesity. This systematic review, registered in PROSPERO and conducted following PRISMA guidelines, evaluates klotho levels in individuals with obesity or sarcopenic obesity. The study includes overweight, obese, and sarcopenic obese adults compared to those with a normal body mass index. After reviewing 713 articles, 20 studies were selected, including observational, cross-sectional, cohort studies, and clinical trials. Significant associations between klotho levels and obesity, metabolic syndrome (MS), and cardiovascular risk were observed. Exercise and dietary interventions positively influenced klotho levels, which were linked to improved muscle strength and slower decline. Klotho is a potential biomarker for obesity, MS, and sarcopenic obesity. Further research is needed to explore its mechanisms and therapeutic potential.

1. Introduction

Klotho has been identified as an anti-aging gene as its downregulation leads to aging-like phenotypes [1] and extends lifespan when overexpressed [2]. After the discovery of α-klotho (Klotho gene (KL gene), chromosome 13q12.1) [2,3], two homologous proteins were identified and named β-klotho (β-Klotho gene, chromosome 4q26) [4,5] and γ-klotho (KL gene, chromosome 15q22.31) [6]. The α-klotho has two isoforms [7], as a membrane protein mainly expressed in distal convoluted tubules in the kidney and choroid plexus in the brain, but also in endocrine organs [8,9], and as a secreted klotho protein (s-klotho)—the extracellular domain—that locates in the blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [10,11]. Research studies have acknowledged α-klotho as a co-receptor for fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) since the phenotypes of mice lacking klotho and FGF23 were similar [12]. FGF23 and α-klotho might function in a common endocrine system that regulates phosphate metabolism [13]. Under physiological concentrations, FGF23 activation of the c-splice isoforms of FGFR1-3 and FGFR4 requires the formation of a binary complex with membrane-bound klotho, which enhances receptor affinity for FGF23 [5,14,15]. However, secreted klotho seems to be involved in the regulation of multiple ion channels, such as transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 5 (TRPV5) [16], and growth factor receptors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor [10], on the cell surface. In addition to klotho-interacting FGF23, there are two other endocrine FGFs that interact with β-klotho, which is mainly expressed in the liver and white adipose tissue: FGF19 and FGF21 [5,17]. Interestingly, while the intestine has been shown to secrete FGF19 to suppress liver bile acid synthesis in response to feeding, the liver has been found to secrete FGF21 to promote lipolysis and other metabolic responses in white adipose tissue as a consequence of fasting [18]. Therefore, klotho proteins could be principal actors in the regulation of endocrine FGFs [19]. FGF21 has also been found to be expressed in human muscle in response to hyperinsulinemia [20], so it has been proposed as a novel insulin-stimulated myokine [21]. In fact, endocrine-acting FGF21 released by muscle leads to a browning of white adipose tissue [22]. Thus, there is a constant intercommunication between white adipose and muscle tissues that can be altered with the age-dependent klotho and FGF21 decrease, which could be key in the development of sarcopenic obesity.

Overall, this work aims to systematically evaluate and synthesize the existing evidence on klotho levels in adults with obesity and sarcopenic obesity and to compare these levels with those of healthy adults. Additionally, it seeks to determine the existence of correlations between klotho levels and the presence of obesity or sarcopenic obesity.

2. Materials and Methods

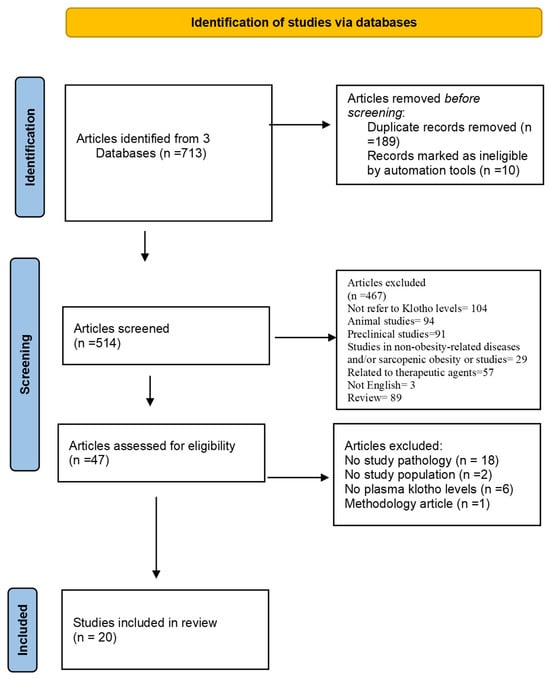

This systematic review was registered at the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42024569938). It was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1) [23]. It considers the findings of the clinical trials and below will clarify the systematic review question and PICOTS, study eligibility, search strategy, data collection and extraction, and validity assessment of risks of bias in included studies. No ethical approval was required for this study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram: study selection process for a systematic review on klotho protein levels in obesity and sarcopenic obesity [23].

2.1. Systematic Review Question and PICOTS

This systematic review was conducted to investigate klotho levels in people with obesity or sarcopenic obesity. For the PICOTS of the review [population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), outcome (O), time (T), and study design (S)], the criteria were defined prior to the literature search and are detailed in Table 1. Concisely, our study question was: Adults with overweight, body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 Kg/m2 or obesity (BMI ≥ 30 Kg/m2) and adults with sarcopenic obesity (according to ESPEN EASO criteria) [24] (P); “intervention” is not directly applicable, as we were observing existing conditions, not interventions (I); compared with adults with normal BMI (C); may have an impact on klotho levels (O); at any time and for any duration (T); in clinical trials (CTs) (S).

Table 1.

Study characteristics and patient demographics in obesity and sarcopenic obesity research.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2.1. Study Design, Literature Search, and Data Collection

Our objective was to compile the most important literature that provides evidence of klotho levels in the population with obesity and/or sarcopenic obesity and the difference between these levels and a healthy population. For a more comprehensive analysis, the authors included populations related to obesity, such as metabolic syndrome (MS). Additionally, the effect of physical exercise and diet interventions on klotho levels was examined.

No date restrictions were applied during the literature search. The bibliographic search was carried out mainly using the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, as well as the reference lists of the selected studies, and included only manuscripts written in English. The titles and abstracts of all electronic articles were screened for eligibility.

Our search was conducted using the following MeSH/keywords: [“Klotho” AND (“sarcopenic obesity” OR “obesity” OR “sarcopenia”)]. Two authors (D.A. and E.G.) independently reviewed all articles for eligibility, while potential disagreements were resolved by consensus among all authors.

We searched for human studies, experimental studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized studies of interventions, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published in medical journals before 29 February 2024, while excluding case reports, editorials, conference abstracts, reviews, and posters.

2.2.2. Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

All authors participated in the data analysis and each of them extracted data from each article in the preliminary stage. Two authors then reviewed all extracted data and added significant findings if any had been omitted. A wide variety of results were found. We focus on the following:

- Klotho levels in a population with overweight, obesity, and/or sarcopenic obesity.

- The differences in klotho levels compared with a healthy population.

- The relationship between klotho levels and anthropometric parameters and between klotho levels and body composition.

- The relationship between klotho levels and muscle strength parameters.

- Populations related to obesity such as MS and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) were included.

We noted results from studies that matched specific sections. Studies with similar results were tabulated together according to their sequence of description in the article.

Studies that did not refer to klotho levels, animal studies, preclinical studies, studies on non-obesity-related diseases and/or sarcopenic obesity, or studies related to therapeutic agents were excluded during the screening phase as being outside the scope of the review.

Among the 713 published articles considered, 189 were excluded after the removal of duplicates, and 477 were excluded during the selection phase based on the following exclusion criteria: failure to address the pathology under study, lack of relevance to the target population, absence of klotho level measurements, and limitations in the methodological approach.

All 47 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 27 were excluded after the selection of abstracts or full text. Finally, 20 studies were selected. The flow chart of the selection process is presented in Figure 1.

3. Results

The analysis comprised twenty studies, which included one observational study, thirteen cross-sectional studies, two longitudinal cohort studies, and three clinical trials.

Among the six studies that established a relationship between klotho levels and obesity, three were related to MS, three were related to cardiovascular risk, four were related to physical exercise and diet, and four were related to older adult patients.

3.1. Studies Relating Klotho Levels with Obesity

Numerous studies have robustly linked klotho levels to obesity. Research by Amitani et al., Amaro-Gahete et al., Collin et al., Huang et al., Orces et al., and Bednarska et al. has all contributed to this understanding [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Table 1 presents the studies and results regarding klotho levels and their correlation with obesity, overweight, and/or sarcopenic obesity.

A comparative cross-sectional study of 34 adults (11 with obesity, 12 with restrictive anorexia nervosa [r-AN], and 11 controls) analyzed plasma α-klotho levels in different nutritional states. Amitani et al. (2013) [25] found lower α-klotho levels in obesity and r-AN, with a significant increase after BMI recovery in r-AN patients, suggesting klotho as a potential biomarker of nutritional status.

Amaro-Gahete et al. [26] conducted a cross-sectional study on 74 sedentary middle-aged adults (53.7 ± 5.1 years, 52.7% women) to examine the association between body composition and s-klotho plasma levels. The study identified significant positive correlations between BMI and s-klotho (β = 33.981, R2 = 0.125, p = 0.002) and between lean mass index (LMI) and s-klotho (β = 74.794, R2 = 0.346, p < 0.001). Both associations remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and fat mass index, reinforcing the potential link between s-klotho and body composition parameters.

Bednarska et al. [27] analyzed serum β-klotho, FGF19, and FGF21 in 85 young, normal-weight women 67 with PCOS and 18 controls, finding significantly higher levels in PCOS patients. Strong correlations with PCOS diagnosis suggest these biomarkers may serve as potential predictors.

Huang et al. [28] conducted a cross-sectional study on 1950 adults (1119 men, 831 women) aged ≥ 40 years, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2016 to examine s-klotho concentrations, sagittal abdominal diameter (SAD), and metabolic parameters. The study identified a significant inverse association between SAD and s-klotho (β = −12.02), with a stronger negative correlation in individuals with BMI ≥ 30 Kg/m2 (β = −18.83, p = 0.001). Findings suggest a concentration-dependent relationship between SAD and s-klotho.

Orces (2022) [29] conducted a cross-sectional study on 4971 adults aged ≥ 40 years using NHANES 2007–2016 and confirmed lower s-klotho levels in obese individuals compared to those with normal weight, particularly in women. The study indicated an inverse association between general and abdominal obesity in women and s-klotho levels. Women who developed obesity earlier in life (765.0 pg/mL 25 years before, and 757.4 pg/mL 10 years before) had significantly lower mean s-klotho levels compared to those who were never obese (820.5 pg/mL). However, no significant differences in serum klotho levels were observed among men regardless of weight history.

Collins et al. [30] conducted an RCT involving 383 adults (BMI: 25–40 Kg/m2; age: 18–55 years) to evaluate changes in circulating α-klotho levels following weight loss interventions. Participants were randomly assigned to either a diet-only or a diet-plus-exercise program for 6 or 12 months and categorized based on their weight loss response: Responders (≥10% weight loss) and Non-responders (<5% weight loss) at both time points. Changes in circulating α-klotho levels were inversely correlated with reductions in weight (rs = −0.195), BMI (rs = −0.196), fat mass (FM) (rs = −0.184), and waist circumference (rs = −0.218), all of which were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

3.2. Studies Relating Klotho Levels with Metabolic Syndrome

Lower S-KL levels are linked to MS and its components [31,32], a phenomenon also observed in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) due to the inflammation and insulin resistance they exhibit [33]. Table 2 summarizes studies examining KL levels and their association with MS patients.

Table 2.

Study characteristics and patient demographics in metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk research.

In research conducted by Cheng et al. [31], a study analyzed data from 9976 participants aged 18 and older (32.2% women), followed by Orces et al. [32], who studied 5069 participants (50% women, 57.4 ± 10.6 years). Both studies consistently demonstrated a negative relationship between the occurrence of MS and the concentrations of s-klotho. Even after accounting for various factors, the studies showed an inverse correlation between s-klotho levels and the number of MS components.

Detailed statistical analyses indicated that s-klotho levels were negatively associated with abdominal obesity and elevated triglycerides (TG) levels in both studies. Furthermore, a positive correlation was identified between s-klotho levels and high glucose concentrations in both investigations.

In a population of patients with HIV infection (n = 261), a study by Gutiérrez-Pérez et al. [33] found that the prevalence of MS was notably higher compared to a control group. Despite comparable weight and BMI between the HIV-infected and non-HIV groups, the HIV-infected population exhibited lower levels of β-klotho. This disparity implies that inflammation, heightened insulin resistance, and the presence of MS are contributing factors to the reduced β-klotho levels observed in HIV-infected individuals [33].

3.3. Studies Relating Klotho Levels with Cardiovascular Risk

Semba et al. [34], Amaro-Gahete et al. [35], and Lee et al. [36] demonstrated that higher s-klotho levels are associated with reduced cardiovascular and cardiometabolic risks, lower obesity rates, and improved lipid profiles. Table 2 provides an overview of studies investigating klotho levels and their association with cardiovascular risk.

In the study by Semba et al. [34] involving 1023 participants, 25.3% of whom had cardiovascular disease (55.1% women, aged 24–102 years), the median s-klotho concentration was 676 (530, 819) pg/mL. s-klotho correlated with age, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), and C-reactive protein (CRP), but not with systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, or renal function. After adjusting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, a significant association was found between log s-klotho and prevalent cardiovascular disease, with an odds ratio of 0.85 (95% confidence interval: 0.72 to 0.99) per one standard deviation increase.

Amaro-Gahete et al. [35] calculated a cardiometabolic risk score based on waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, HDL-c, and TG. This cross-sectional study included 214 healthy, sedentary adults, with approximately 64% women aged 18–25 years. A significant inverse relationship was found between s-klotho and the cardiometabolic risk score in middle-aged men and women (β = −0.658, R2 = 0.433, p < 0.001 and β = −0.442, R2 = 0.195, p = 0.007, respectively). However, no significant association was found between s-klotho and the cardiometabolic risk score in young, healthy adults (p > 0.5), nor for young, healthy men and women when analyzed separately (all p > 0.1).

In a study by Lee et al. [36] involving 13,154 participants, 75% being women aged 40–79 years, higher levels of circulating klotho were associated with lower rates of being overweight (β = −22.609, p = 0.0025) and obese (β = −23.716, p = 0.0011), as well as reduced rates of current smoking (β = −46.412, p < 0.0001) and alcohol consumption (β = −51.194, p < 0.0001). The study also found that s-klotho levels decreased with higher levels of TG (β = −0.117, p = 0.0006) and total cholesterol (β = −0.249, p = 0.0002).

3.4. Studies Relating Klotho Levels with Exercise and Diet

Fat oxidation and plasma s-klotho levels are positively correlated [37], while exercise [38] and dietary interventions [39] enhance s-klotho concentrations, improving metabolic and inflammatory profiles in sedentary and overweight individuals [40]. Table 3 presents a summary of studies exploring the relationship between klotho levels, diet, and exercise.

Table 3.

Study characteristics and patient demographics in exercise and diet research.

The study by Amaro-Gahete et al. [37] in 2019 aimed to explore the relationship between basal metabolic rate (BMR), fuel oxidation, and plasma s-klotho in 74 middle-aged sedentary adults (53% women, 53.7 ± 5.1 years). The results revealed no significant correlation between BMR and plasma s-klotho (p > 0.1). However, both basal fat oxidation and maximal fat oxidation (MFO) during exercise exhibited positive associations with s-klotho (both p < 0.001), which remained significant even after adjusting for age, sex, and FM. Interestingly, there were no significant associations found between BMR, basal fat oxidation, or MFO and chronological age (all p > 0.1). These findings suggest a strong link between basal fat oxidation, MFO, and plasma s-klotho in middle-aged sedentary adults.

Amaro-Gahete et al. [38] investigated the impact of different training modalities on s-klotho plasma levels in 68 sedentary, middle-aged adults (52.7% women, 53.4 ± 5.0 years). The study revealed that s-klotho levels increased in response to physical activity interventions like physical activity recommendations, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), and HIIT combined with whole-body electromyostimulation (HIIT-EMS) compared to the control group (p = 0.003, p = 0.019, p < 0.001, respectively), with no significant differences between the intervention groups. Positive associations were found between changes in LMI and s-klotho levels, while negative associations were observed between changes in FM outcomes and s-klotho levels, persisting even after adjusting for sex and age.

In the cross-sectional study conducted by Ma et al. [39], which used data from the NHANES from 2007 to 2016, including 8456 participants aged 40–79 years, data from 24-h dietary recalls were used to calculate the Healthy Eating Index 2015 (HEI-2015) for each participant. A positive correlation was observed between HEI-2015 and s-klotho plasma levels (β = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.21, 1.27, p = 0.0067). The analysis indicated a turning point of HEI-2015 at 45.15, where a significant dose-response relationship was observed between HEI-2015 and s-klotho levels. Furthermore, individuals with a normal BMI showed a more pronounced association between HEI-2015 and s-klotho concentrations.

Silva-Reis et al. [40] explored the effects of 12 weeks of combined physical exercise on lung function and mechanics in non-obese (n = 12), overweight (n = 17), and obese grade I (n = 11) women. The study showed that the exercise regimen reduced pro-fibrotic IGF-1 levels in overweight and obese groups, increased klotho levels in obese individuals, and decreased exhaled nitric oxide levels in both overweight and obese groups.

3.5. Studies Relating to Klotho Levels in Older Adults

Lower s-klotho levels are associated with reduced grip and knee strength, highlighting its role in muscle function [41,42]. However, studies report no significant links between s-klotho and frailty or fractures, warranting further investigation [43,44]. Table 4 presents a summary of studies examining klotho levels and their associations in older adults.

Table 4.

Study characteristics and patient demographics in older adults.

In the Aging in the Chianti Area (InCHIANTI) study [41], involving 804 older adults aged 65 and above (55.8% women), grip strength showed a positive correlation with s-klotho at a threshold of less than 681 pg/mL. After adjusting for several factors, s-klotho (per 1 standard deviation increase) was associated with grip strength (β = 1.20, SE = 0.35, p = 0.0009) in adults with s-klotho levels below 681 pg/mL, indicating that older adults with poorer skeletal muscle strength have lower s-klotho levels.

Semba et al. [42] analyzed the relationship between s-klotho levels and knee strength in older adults (aged 71–79 years) based on data from 1983 participants. Individuals in the highest tercile of s-klotho exhibited significantly greater knee extension strength (β = 0.72, SE = 0.018, p < 0.0001) than those in the lowest tercile, after adjusting for various factors in a multivariable linear regression model. Additionally, participants in the highest tercile of s-klotho at baseline experienced less decline in knee strength over 4 years of follow-up (β = −0.025, SE = 0.011, p = 0.02) compared to those in the lowest tercile.

The study by Chalhoub et al. [43] found no significant association between the lowest quartile of s-klotho levels and non-spine, hip, or vertebral fractures. This analysis included 2776 participants aged 70–79 from the Health ABC cohort, of whom 52% were women.

Polat et al. [44] conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the relationship between frailty and s-klotho levels in geriatric patients. The study included 89 individuals aged 65 and older, divided into two groups: 45 frail patients and 44 non-frail controls. The mean s-klotho levels of the control and frail groups were 0.76 ± 1.01 ng/mL and 0.54 ± 0.61 ng/mL, respectively. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.286).

4. Discussion

Obesity is a major public health challenge, with a rising prevalence affecting one in eight individuals worldwide [45]. Beyond classical metabolic complications, obesity frequently coexists with sarcopenia, a condition characterized by the loss of muscle mass and functionality, leading to sarcopenic obesity. This phenotype exacerbates metabolic dysfunction, increases the risk of disability, and is associated with higher mortality rates [46].

Epidemiological studies indicate that sarcopenia affects approximately 10–16% of older adults globally [47]. In Spain, no nationwide epidemiological studies have been conducted, and prevalence varies by setting, affecting between 15% and 50% [48,49,50,51,52]. Additionally, the EXERNET multicenter study underscores the relevance of body composition assessment in aging populations [53]. Sarcopenic obesity arises from a multifactorial interaction between adipose tissue dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and muscle degradation, further intensifying insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction [54].

Several biomarkers have been identified for sarcopenia, including the creatinine/cystatin C ratio, C-terminal agrin fragment, and multiple microRNAs (miR-7a-1-3p, miR-135a-5p, miR-151-5p, miR-196b-5p) [55,56,57]. Additionally, inflammatory and metabolic markers such as CRP, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IGF-1, myostatin, follistatin, and growth differentiation factor 15 have been highlighted [58,59,60]. While these biomarkers exhibit potential for sarcopenia diagnosis, their diagnostic accuracy remains limited, necessitating further studies to validate their clinical applicability. Despite its clinical significance, no pharmacological treatments for sarcopenic have been approved [61]. Investigational strategies include myostatin inhibitors, follistatin, IGF-1, and inflammatory modulators such as CRP and IL-6 [62].

Klotho, a pleiotropic protein associated with longevity, has emerged as a critical factor in aging research [63]. Its deficiency has been linked to various age-related diseases, including cancer, chronic kidney disease, ataxia, diabetes, and skin atrophy [64,65]. However, the relationship between klotho and conditions such as obesity and MS remains incompletely understood, providing the basis for this systematic review.

This analysis, encompassing 20 studies, consistently revealed a negative association between s-klotho levels and obesity, particularly in women. Notably, women who developed obesity earlier in life exhibited significantly lower s-klotho levels compared to those with normal weight [25,26,27,28,29,30]. This observation underscores the possibility that early-life obesity may lead to long-lasting biological changes impacting klotho expression, with potential sex-specific implications. These findings highlight the need to further explore the mechanistic links between obesity and longevity-related pathways mediated by klotho.

Similarly, research on school-age children revealed that serum α-klotho concentrations were negatively associated with obesity-related parameters, particularly in girls, indicating that early-life obesity might have a more pronounced effect on klotho levels in females [66]. Moreover, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, a condition often associated with obesity, lower serum klotho levels were observed in those with moderate cognitive impairment, further linking metabolic health and klotho expression [67].

The review also demonstrated that s-klotho levels are inversely associated with specific components of MS, such as abdominal obesity and elevated TG levels, while a positive association was observed with elevated glucose levels [31,32]. This suggests that s-klotho might serve not only as an early biomarker for metabolic risk but also as a mediator in the development and progression of metabolic disorders. Future research should prioritize elucidating the underlying mechanisms to determine whether klotho could be leveraged as a therapeutic target.

The evidence indicates that the concentration of the klotho protein might influence the onset and advancement of MS. This underscores the significant role that klotho could have in maintaining metabolic health, particularly regarding its relationship with conditions such as obesity, lipid imbalances, and elevated blood sugar levels [67]. This is consistent with the findings presented in the research by de Luca Corrêa et al. [68].

Regarding cardiovascular risk, higher circulating klotho levels have been associated with lower rates of overweight and obesity, as well as reduced prevalence of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption [34,35,36]. Moreover, in individuals with carotid atherosclerosis, lower klotho protein levels in the blood and reduced KL gene expression in vascular tissues were observed alongside higher carotid-intima media thickness values [69]. These findings suggest that klotho may play a role in mitigating cardiovascular risk through its anti-inflammatory and vascular-protective properties [70].

Lifestyle interventions such as regular aerobic exercise [37,38,39,40] and healthy dietary patterns [39] appear to support the maintenance or increase of s-klotho levels. These interventions may mitigate age-related metabolic and inflammatory changes, thereby preserving functional health. Additionally, elevated s-klotho levels have been positively correlated with muscle strength and physical performance in older adults, such as increased knee extension strength and reduced strength decline over time [41,42,43,44]. These findings underscore the potential of klotho in preventing functional deterioration and promoting healthy aging.

Despite these promising insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. The variability in study designs, including observational, cross-sectional, and cohort studies, complicates direct comparisons and reduces the generalizability of findings. Gender-related discrepancies, as reported in Orces’ study [29], further highlight the need for more targeted research to understand sex-specific variations. Additionally, the heterogeneity of study populations, including those with conditions like PCOS, r-AN, and older adults, warrants cautious interpretation of the results.

The primary limitation of the review lies in the establishment of associations rather than causative relationships between klotho levels and obesity-related parameters. Cross-sectional studies, which provide only a snapshot in time, are insufficient to infer causality or directionality in these associations. Furthermore, variations in adjustments for confounding factors across studies and potential sample size limitations could introduce bias and affect the robustness of conclusions.

5. Conclusions

The review uncovered a complex relationship between klotho protein levels and various aspects of obesity and related health issues. Higher levels of s-klotho have been positively linked with BMI and LMI, indicating a possible association between klotho levels and body composition. Lower concentrations of s-klotho have been found in obese women compared to those with normal weight, suggesting potential gender disparities in klotho expression related to obesity. Inverse associations have been observed between s-klotho concentrations and the prevalence of MS and cardiovascular risk, positioning s-klotho as a potential predictive biomarker for these conditions. Exercise and diet have been shown to impact klotho levels, with exercise interventions leading to increased s-klotho levels, emphasizing the significance of lifestyle in obesity management. Higher klotho levels have been associated with greater muscle strength in older adults, hinting at a protective role against age-related declines in muscle function. Implementing klotho level testing in clinical settings could aid in assessing obesity risks and monitoring the effectiveness of intervention strategies. Further research is required to clarify the mechanisms through which klotho influences metabolic processes and its potential therapeutic applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.E., M.D.B.-P. and M.J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.A.-C. and B.E.; writing—review and editing, D.G.A.-C., E.G.-A., B.E., M.P.G.-P., D.E.B.-G., M.R.-V., B.P.d.l.M., D.G.-S., M.D.B.-P. and M.J.C.; supervision, B.E., M.D.B.-P. and M.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Gerencia Regional de Salud (GRS 2326/A/21 and GRS 2516/A/22), Castilla y León, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kurosu, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Miyoshi, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Nandi, A.; Rosenblatt, K.P.; Baum, M.G.; Schiavi, S.; Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W.; et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 6120–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuro-o, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Suga, T.; Utsugi, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Kurabayashi, M.; Kaname, T.; Kume, E.; et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 1997, 390, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Shiraki-Iida, T.; Nagai, R.; Kuro-o, M.; Nabeshima, Y. Identification of the human klotho gene and its two transcripts encoding membrane and secreted klotho protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 242, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Kinoshita, S.; Shiraishi, N.; Nakagawa, S.; Sekine, S.; Fujimori, T.; Nabeshima, Y.I. Molecular cloning and expression analyses of mouse betaklotho, which encodes a novel Klotho family protein. Mech. Dev. 2000, 98, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosu, H.; Choi, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Dickson, A.S.; Goetz, R.; Eliseenkova, A.V.; Mohammadi, M.; Rosenblatt, K.P.; Kliewer, S.A.; Kuro-O, M. Tissue-specific Expression of βKlotho and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Receptor Isoforms Determines Metabolic Activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 26687–26695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Fujimori, T.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Nabeshima, Y. Identification of a novel mouse membrane-bound family 1 glycosidase-like protein, which carries an atypical active site structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002, 1576, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Sun, Z. Molecular basis of Klotho: From gene to function in aging. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuro-o, M. Klotho as a regulator of oxidative stress and senescence. Biol. Chem. 2008, 389, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dov, I.Z.; Galitzer, H.; Lavi-Moshayoff, V.; Goetz, R.; Kuro-o, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Sirkis, R.; Naveh-Many, T.; Silver, J. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 4003–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosu, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Clark, J.D.; Pastor, J.V.; Nandi, A.; Gurnani, P.; McGuinness, O.P.; Chikuda, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kawaguchi, H.; et al. Suppression of Aging in Mice by the Hormone Klotho. Science 2005, 309, 1829–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imura, A.; Iwano, A.; Tohyama, O.; Tsuji, Y.; Nozaki, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Fujimori, T.; Nabeshima, Y.I. Secreted Klotho protein in sera and CSF: Implication for post-translational cleavage in release of Klotho protein from cell membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004, 565, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.E.; Evans, W.E.; O’Riordan, J.L.H.; ADHR Consortium. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakawa, I.; Yamazaki, Y.; Shimada, T.; Iijima, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Okawa, K.; Fujita, T.; Fukumoto, S.; Yamashita, T. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature 2006, 444, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ibrahimi, O.A.; Goetz, R.; Zhang, F.; Davis, S.I.; Garringer, H.J.; Linhardt, R.J.; Ornitz, D.M.; Mohammadi, M.; White, K.E. Analysis of the Biochemical Mechanisms for the Endocrine Actions of Fibroblast Growth Factor-23. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4647–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, G.J.; Kurt, M.; Wang, Q. Pathobiology of the Klotho Antiaging Protein and Therapeutic Considerations. Front. Aging 2022, 12, 931331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.K.; Ortega, B.; Kurosu, H.; Rosenblatt, K.P.; Kuro-o, M.; Huang, C.L. Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9805–9810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, R.; Beenken, A.; Ibrahimi, O.A.; Kalinina, J.; Olsen, S.K.; Eliseenkova, A.V.; Xu, C.F.; Neubert, T.A.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; et al. Molecular Insights into the Klotho-Dependent, Endocrine Mode of Action of Fibroblast Growth Factor 19 Subfamily Members. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 3417–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.; Dutchak, P.; Zhao, G.; Ding, X.; Gautron, L.; Parameswara, V.; Li, Y.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Esser, V.; et al. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARalpha-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuro-o, M. Klotho. Pflüg Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2010, 459, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojman, P.; Pedersen, M.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Yfanti, C.; Akerstrom, T.; Nielsen, S.; Pedersen, B.K. Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 Is Induced in Human Skeletal Muscles by Hyperinsulinemia. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2797–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keipert, S.; Ost, M.; Johann, K.; Imber, F.; Jastroch, M.; van Schothorst, E.M.; Keijer, J.; Klaus, S. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial uncoupling drives endocrine cross-talk through the induction of FGF21 as a myokine. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E469–E482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Clin. Nutr. Edinb. Scotl. 2022, 41, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitani, M.; Asakawa, A.; Amitani, H.; Kaimoto, K.; Sameshima, N.; Koyama, K.I.; Haruta, I.; Tsai, M.; Nakahara, T.; Ushikai, M.; et al. Plasma klotho levels decrease in both anorexia nervosa and obesity. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; De-la-O, A.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Espuch-Oliver, A.; de Haro, T.; Gutiérrez, A.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J. Body Composition and S-Klotho Plasma Levels in Middle-Aged Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Rejuvenation Res. 2019, 22, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarska, S.; Fryczak, J.; Siejka, A. Serum β-Klotho concentrations are increased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cytokine 2020, 134, 155188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.W.; Fang, W.H.; Chen, W.L. Clinical Relevance of Serum Klotho Concentration and Sagittal Abdominal Diameter. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orces, C.H. The Association of Obesity and the Antiaging Humoral Factor Klotho in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 7274858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.A.; Ambrosio, F.; Rogers, R.J.; Lang, W.; Schelbert, E.B.; Davis, K.K.; Jakicic, J.M. Change in circulating klotho in response to weight loss, with and without exercise, in adults with overweight or obesity. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1213228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Hung, C.C.; Fang, W.H.; Chen, W.L. Association between Soluble α-Klotho Protein and Metabolic Syndrome in the Adult Population. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orces, C.H. The association between metabolic syndrome and the anti-aging humoral factor klotho in middle-aged and older adults. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Pérez, M.E.; Urraza-Robledo, A.I.; Miranda-Pérez, A.A.; Molina-Flores, C.A.; Ruíz-Flores, P.; Delgadillo-Guzmán, D.; López-Márquez, F.C. Role of β-Klotho and Malondialdehyde in Metabolic Disorders, HIV Infection, and Antiretroviral Therapy. DNA Cell Biol. 2022, 41, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Cappola, A.R.; Sun, K.; Bandinelli, S.; Dalal, M.; Crasto, C.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Plasma klotho and cardiovascular disease in adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; García-Lario, J.V.; Castillo, M.J.; Ruiz, J.R. Relationship between plasma S-Klotho and cardiometabolic risk in sedentary adults. Aging 2020, 12, 2698–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Min, J.Y.; Min, K.B. Association between serum klotho levels and cardiovascular disease risk factors in older adults. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; De-la-O, A.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J. Association of basal metabolic rate and fuel oxidation in basal conditions and during exercise, with plasma S-klotho: The FIT-AGEING study. Aging 2019, 11, 5319–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; De-la-O, A.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Espuch-Oliver, A.; de Haro, T.; Gutierrez, A.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J. Exercise training increases the S-Klotho plasma levels in sedentary middle-aged adults: A randomised controlled trial. The FIT-AGEING study. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.X.; Lin, Z.Z.; Gao, F. Associations between the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and S-Klotho plasma levels: A cross-sectional analysis in middle-to-older aged adults. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 904745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Reis, A.; Rodrigues Brandao-Rangel, M.A.; Moraes-Ferreira, R.; Gonçalves-Alves, T.G.; Souza-Palmeira, V.H.; Aquino-Santos, E.H.; Lacerda Bachi, A.L.; Franco de Oliveira, L.V.; Brandão Lopes-Martins, R.A.; Oliveira-Silva, I.; et al. Combined resistance and aerobic training improves lung function and mechanics and fibrotic biomarkers in overweight and obese women. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 946402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; Cappola, A.R.; Sun, K.; Bandinelli, S.; Dalal, M.; Crasto, C.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Relationship of low plasma klotho with poor grip strength in older community-dwelling adults: The InCHIANTI study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Ferrucci, L.; Sun, K.; Simonsick, E.; Turner, R.; Miljkovic, I.; Harris, T.; Schwartz, A.V.; Asao, K.; Kritchevsky, S.; et al. Low Plasma Klotho Concentrations and Decline of Knee Strength in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, D.; Marques, E.; Meirelles, O.; Semba, R.D.; Ferrucci, L.; Satterfield, S.; Nevitt, M.; Cauley, J.A.; Harris, T.; Health ABC Study. Association of serum klotho with loss of bone mineral density and fracture risk in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, e304–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Y.; Yalcin, A.; Yazihan, N.; Bahsi, R.; Surmeli, D.M.; Akdas, S.; Aras, S.; Varli, M. The relationship between frailty and serum alpha klotho levels in geriatric patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 91, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.D.; Chen, Q.F.; Yang, W.; Zuluaga, M.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Valenti, L.; Luo, F.; Katsouras, C.S.; Thaher, O.; et al. Burden of disease attributable to high body mass index: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 76, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Choi, K.M. Interplay of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue: Sarcopenic obesity. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Larsson, S.C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia: Prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvà, A.; Serra-Rexach, J.A.; Artaza, I.; Formiga, F.; Rojano, I.; Luque, X.; Cuesta, F.; López-Soto, A.; Masanés, F.; Ruiz, D.; et al. La prevalencia de sarcopenia en residencias de España: Comparación de los resultados del estudio multicéntrico ELLI con otras poblaciones [Prevalence of sarcopenia in Spanish nursing homes: Comparison of the results of the ELLI study with other populations]. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2016, 51, 260–264. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Montalvo, J.I.; Alarcón, T.; Gotor, P.; Queipo, R.; Velasco, R.; Hoyos, R.; Pardo, A.; Otero, A. Prevalence of sarcopenia in acute hip fracture patients and its influence on short-term clinical outcome. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illamola-Martin, L.; Granados, A.; Sanllorente, A.; Rodríguez, J.J.; Broto, M. Prevalencia de inactividad física y riesgo de sarcopenia en atención primaria. Estudio transversal [Prevalence of physical inactivity and risk of sarcopenia in primary care. Cross-sectional study]. Aten. Primaria 2024, 56, 102993. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillamón-Escudero, C.; Diago-Galmés, A.; Tenías-Burillo, J.M.; Soriano, J.M.; Fernández-Garrido, J.J. Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Valencia, Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, P.; Olmos, J.M.; Llorca, J.; Hernández, J.L.; González-Macías, J. Sarcopenic osteoporosis, sarcopenic obesity, and sarcopenic osteoporotic obesity in the Camargo cohort (Cantabria, Spain). Arch. Osteoporos. 2022, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Cabello, A.; Pedrero-Chamizo, R.; Olivares, P.R.; Luzardo, L.; Juez-Bengoechea, A.; Mata, E.; Albers, U.; Aznar, S.; Villa, G.; Espino, L.; et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in non-institutionalized people aged 65 or over from Spain: The elderly EXERNET multi-centre study. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Liatis, S.; Dalamaga, M.; Kokkinos, A. Sarcopenic Obesity: Epidemiologic Evidence, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2019, 8, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, R.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, M. Blood biomarkers for sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, R.; Kim, Y.; Baek, S.; Suram, R.P.; An, S.L.; Hong, Y. C-Terminal Agrin Fragment as a Biomarker for Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2025, 16, e13707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Z.; Lv, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Fan, J.; Chen, N. MicroRNA profiling of different exercise interventions for alleviating skeletal muscle atrophy in naturally aging rats. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladang, A.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Al-Daghri, N.; Bruyère, O.; Burlet, N.; Cesari, M.; Cherubini, A.; da Silva, M.C.; Cooper, C.; et al. Biochemical Markers of Musculoskeletal Health and Aging to be Assessed in Clinical Trials of Drugs Aiming at the Treatment of Sarcopenia: Consensus Paper from an Expert Group Meeting Organized by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) and the Centre Académique de Recherche et d’Expérimentation en Santé (CARES SPRL), Under the Auspices of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for the Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Conditions and Aging. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2023, 112, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, F.; Ferro, G.; Basile, C.; Liguori, I.; Parrella, P.; Pirozzi, F.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Tocchetti, C.G.; et al. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: A multifactorial approach. Exp. Gerontol. 2016, 85, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinkovich, A.; Livshits, G. Sarcopenia--The search for emerging biomarkers. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 22, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.; Dantas, W.S.; Kirwan, J.P. Sarcopenic obesity: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Metabolism 2023, 146, 155639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeszczyński, F.; Hamilton, D.; Bończak, O.; Brzeszczyńska, J. Systematic Review of Sarcopenia Biomarkers in Hip Fracture Patients as a Potential Tool in Clinical Evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. Current understanding of klotho. Ageing Res. Rev. 2009, 8, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, C.R.; Li, A. Aging-suppressor Klotho: Prospects in diagnostics and therapeutics. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 82, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, M. Emerging role of α-Klotho in energy metabolism and cardiometabolic diseases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreras-Badosa, G.; Puerto-Carranza, E.; Mas-Parés, B.; Gómez-Vilarrubla, A.; Gómez-Herrera, B.; Díaz-Roldán, F.; Riera-Pérez, E.; de Zegher, F.; Ibañez, L.; Bassols, J.; et al. Higher levels of serum α-Klotho are longitudinally associated with less central obesity in girls experiencing weight gain. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1218949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, L.; Yun, G. Reduced Serum Levels of Klotho are Associated with Mild Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Luca Corrêa, H.; Oppelt Raab, A.T.; Marra Araújo, T.; Alves Deus, L.; Lucena Reis, A.; Sousa Honorato, F.; Rodrigues-Silva, P.L.; Passos Neves, R.V.; Simionato Brunetta, H.; Alves da Silva Mori, M.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrating Klotho as an emerging exerkine. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate-Correa, J.; Martín-Núñez, E.; Martin-Olivera, A.; Mora-Fernández, C.; Tagua, V.G.; Ferri, C.M.; López-Castillo, A.; Delgado-Molinos, A.; Castro López-Tarruella, V.; Arévalo-Gómez, M.A.; et al. Klotho inversely relates with carotid intima- media thickness in atherosclerotic patients with normal renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2): A proof-of-concept study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1146012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostamzadeh, F.; Joukar, S.; Yeganeh-Hajahmadi, M. The role of Klotho and sirtuins in sleep-related cardiovascular diseases: A review study. NPJ Aging 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).