Abstract

Heart failure (HF) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting over 30 million individuals, with its prevalence steadily increasing due to population aging. Among its forms, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has emerged as a major clinical and public health concern, now accounting for more than half of all HF cases and closely associated with comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have gained recognition as key regulators of the molecular mechanisms underlying HF, particularly HFpEF, where they modulate interconnected pathways of inflammation, fibrosis, and endothelial dysfunction. This review discusses the mechanisms by which miRNAs contribute to the pathogenesis of HF and examines their potential as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets. By integrating current evidence, it aims to clarify the prognostic significance and clinical applicability of these molecular markers, highlighting their role in advancing personalized strategies for the diagnosis and management of HF.

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a major global cause of mortality and hospitalization, with prevalence rising as populations age. More than 30 million individuals are currently affected, and the number continues to increase [1]. Despite ongoing efforts, a uniform definition of HF in clinical and research practice is not always straightforward. The universal definition describes HF as a clinical syndrome characterized by symptoms or signs resulting from structural or functional cardiac abnormalities, supported by elevated natriuretic peptides (NT-proBNP) or objective evidence of congestion. Current staging emphasizes symptom onset and progression (Figure 1), distinguishing individuals at risk (Stage A), with pre-HF (Stage B), with symptomatic HF (Stage C), and with advanced disease (Stage D). Functional capacity is commonly assessed through the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification, which grades patients from Class I (no limitation of physical activity) to Class IV (symptoms at rest or minimal activity). HF is further categorized by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) into reduced (HFrEF, ≤40%), mildly reduced (HFmrEF, 41–49%), preserved (HFpEF, ≥50%), and improved (HFimpEF), the latter defined by a transition from an LVEF ≤ 40%, to a value above >40% following a substantial increase [2,3].

Figure 1.

Classification of heart failure. The contemporary classification of heart failure (HF) is based on the universal definition, which identifies HF as a clinical syndrome arising from structural or functional cardiac abnormalities accompanied by symptoms, signs, elevated natriuretic peptides, or objective evidence of congestion. The staging framework reflects symptom onset and progression, distinguishing individuals at risk (Stage A), with pre-HF (Stage B), with symptomatic HF (Stage C), and with advanced disease (Stage D). Functional status is evaluated using the NYHA classification, and HF is further categorized by left ventricular ejection fraction into HFrEF (≤40%), HFmrEF (41–49%), HFpEF (≥50%), and HFimpEF, defined by an improvement from ≤40% to a value above 40%.

HFpEF arises through diverse mechanisms, most frequently involving left ventricular injury due to coronary artery disease (CAD), myocarditis, or valvular pathology. It represents a heterogenous clinical syndrome characterized by a high burden of comorbidities and multisystem involvement, including vascular dysfunction, skeletal muscle abnormalities, and alterations in body composition. Although the biological diversity of HF is increasingly recognized, the fundamental processes distinguishing HFpEF from HFrEF remain incompletely understood. Transitions between LVEF categories are common, and patients with HFmrEF who progress to HFrEF carry a poorer prognosis than those who remain stable or move toward a higher LVEF category [4]. Those transitioning from HFpEF to HFrEF generally exhibit more complex clinical profiles and more severe diastolic dysfunction. Evidence also suggests that HFmrEF may represent a mixed phenotype that can be further refined on the basis of LVEF stability [5]. Meta-analytic data consistently show lower adjusted mortality in HFpEF than in HFrEF [6].

The marked clinical diversity of HF reflects the interplay of numerous risk factors that activate distinct pathophysiological mechanisms to varying degrees. Microvascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, mitochondrial impairment, and autonomic imbalance contribute to functional and structural remodeling at multiple biological levels [7,8]. These processes underscore the need for more effective preventive and therapeutic strategies as HF continues to impose a growing global burden.

Genetic factors play an important role in HF susceptibility and progression. Both rare, highly penetrant variants and numerous common variants exert measurable effects. A recent exome-wide association study involving more than 8000 participants across clinical trials and population cohort identified several genes (FAM221A, CUTC, IFIT5, STIMATE, TAS2R20, CALB2, BLK) in which rare pathogenic variants were associated with adverse HF outcomes [9,10]. Large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have further confirmed the polygenic architecture of HF and related cardiometabolic traits [11,12]. In a meta-analysis of more than 47,000 HF cases, twelve independent variants across eleven genomic loci were linked to HF, many of them shared with CAD, atrial fibrillation (AF), or impaired ventricular function. Genes involved in cardiac development (MYOZ1, SYNPO2L), protein homeostasis (BAG3), and cellular senescence (CDKN1A) appear to be particularly relevant. These insights highlight the value of genetic information for refining diagnosis and improving patient management, especially in inherited cardiomyopathies [13].

Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) capture the cumulative effect of multiple HF-associated variants and have demonstrated predictive value for several cardiovascular conditions [14,15]. Scores derived from 238 genetic variants influencing ventricular geometry or associated with chronic HF improved risk estimation beyond traditional clinical predictors [16]. Integrating PRS with established factors, including NT-proBNP levels, enhances prognostic accuracy [17], suggesting a potential role for such tools in future risk-stratification models [18,19].

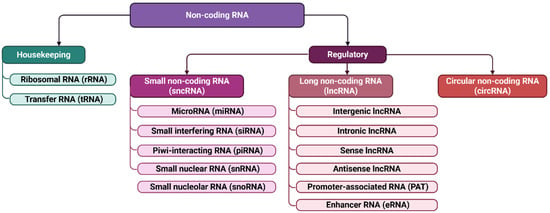

Growing evidence underscores the pivotal role of non-coding RNAs in HF pathogenesis. Regulatory non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (Figure 2), participate in chromatin regulation, transcriptional control, and post-transcriptional gene silencing. MiRNAs are particularly relevant, as they modulate apoptosis, inflammatory signaling, fibrosis, angiogenesis, and metabolic remodeling [20,21,22,23]. Their involvement begins early in cardiac development, where dysregulation can lead to congenital defects [24,25], and continues throughout life in processes governing myocardial injury and repair [24,26,27]. Mature cardiomyocytes lose their proliferative capacity after birth, so perturbations in miRNA networks can contribute to irreversible damage and progressive ventricular dysfunction.

Figure 2.

Non-coding RNAs classification. Non-coding RNAs are classified according to their function and size. This includes housekeeping RNAs, such as ribosomal (rRNA) and transfer (tRNA) RNAs, as well as regulatory non-coding RNAs. Regulatory RNAs are further subdivided into small non-coding RNAs, up to 200 nucleotides in length—including microRNAs (miRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs)—and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which exceed 200 nucleotides.

MiRNAs also influence individual susceptibility to hypertrophy, fibrosis, and other maladaptive processes that culminate in HF [28,29]. Aberrant expression patterns correlate with disease progression, offering opportunities for both diagnostic and therapeutic innovation. Ongoing work aimed at characterizing the miRNA transcriptome, elucidating regulatory pathways, and identifying HF-specific miRNAs is essential for developing personalized approaches to monitoring and treating HF [28].

This review focuses on the mechanisms through which miRNAs contribute to HF pathogenesis and examines their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was structured to synthesize current understanding of the mechanisms by which miRNAs contribute to the development and progression of HF, and to assess their emerging utility as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic candidates. Sources were identified through searches in MEDLINE via Ovid (last accessed October 2025), Scopus (last accessed October 2025), Web of Science (last accessed October 2025), and Google Scholar (last accessed November 2025). The search strategy applied the terms “heart failure with preserved ejection fraction” or “HFpEF” or “diastolic heart failure” combined with “non-coding RNA” or “microRNA” or “miRNA” or “lncRNA” or “long non-coding RNA” or “circRNA” or “circular RNA” or “small nucleolar RNA”. Human studies were prioritized, and work involving rodent or other animal models was included when relevant mechanistic insight was provided. Search outputs from MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science were exported in RIS or BibTeX format for screening.

Inclusion required that studies reported original data linking non-coding RNA expression or function to HFpEF, defined by preserved LVEF and diastolic impairment according to clinical guideline criteria, or by established phenotypes in experimental models. Articles needed to present extractable data illustrating regulatory roles, diagnostic or prognostic associations, or therapeutic modulation of microRNAs. Only peer-reviewed full-text manuscripts written in English were incorporated. There were no formal date restrictions, but most selected material was published between 2000 and early 2025. Exclusion was applied when studies investigated heart failure with reduced ejection fraction without presenting HFpEF-specific results, or when analysis of non-coding RNAs was incidental and lacked expression or functional evaluation. Reviews, commentaries, editorials, protocols, and conference abstracts without a complete dataset were omitted. Duplicate reports from shared cohorts were removed unless additional analysis justified inclusion. All records were screened for relevance by two reviewers trained in cardiovascular molecular biology, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Articles meeting the predetermined criteria were evaluated for methodology, sample characteristics, analytical approach, and reported outcomes relating to microRNA-mediated regulation in HFpEF progression, with emphasis on reproducibility and biological plausibility.

3. Pathophysiology and Molecular Mechanisms of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

HFpEF is primarily driven by abnormalities in diastolic relaxation, myocardial stiffness, and impaired energetic homeostasis rather than systolic pump failure. At the molecular level, its pathogenesis reflects a convergence of metabolic dysregulation, mitochondrial impairment, endothelial dysfunction, chronic low-grade inflammation, and interstitial fibrosis. Persistent neurohormonal activation promotes norepinephrine, angiotensin II, and aldosterone release, initiating vasoconstriction, hypertrophy, and redox imbalance. As oxidative burden increases, cardiomyocytes experience mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced fatty acid oxidation, and a shift toward glycolytic metabolism, leading to ATP deficiency and impaired diastolic relaxation [30,31]. Disrupted calcium cycling prolongs cytosolic calcium transients, delays myocardial relaxation, and activates hypertrophic transcriptional programs [30]. Excess reactive oxygen species amplify mitochondrial injury, impair electron transport chain function, inhibit ATP synthase activity, and induce ROS-driven ROS release. These events initiate apoptosis, stimulate fibroblast activation, and promote extracellular matrix accumulation, resulting in increased ventricular stiffness. Parallel inflammatory signaling, characterized by heightened TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, activates NFκB and matrix metalloproteinases, degrading extracellular structure and accelerating collagen deposition. Endothelial dysfunction further impairs nitric oxide bioavailability, exacerbates microvascular rarefaction, and worsens metabolic flexibility. Ultimately, these interconnected processes culminate in energetic failure, fibrosis, and maladaptive remodeling that define HFpEF.

MiRNAs are recognized as key epigenetic regulators that coordinate fibrotic, inflammatory, metabolic, and survival pathways in HFpEF. Distinct miRNA signatures sustain chronic inflammation and extracellular matrix expansion by modulating multiple targets simultaneously [32,33,34]. The involvement of selected miRNAs and their regulatory targets in HF pathogenesis is presented in Figure 3. In addition to miRNA-driven mechanisms, other epigenetic regulators contribute to metabolic and inflammatory control. Notably, recombinant Sirt1 supplementation has been shown to restore cardiac lipid homeostasis and prevent diabetes-related metabolic cardiomyopathy, underscoring the broader epigenetic landscape in HFpEF [35].

Figure 3.

MicroRNA-mediated mechanisms in heart failure pathogenesis. The figure illustrates the principal miRNAs and their downstream targets that participate in the key processes driving heart failure, including inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, and structural cardiac remodeling. MiRNAs and targets that promote these pathogenic pathways are shown in red, whereas those that exert protective or compensatory effects appear in green. Arrows denote potentiating or activating effects, while blunt arrows indicate inhibitory interactions. CTGF—Connective Tissue Growth Factor; Grb10—Growth Factor Receptor-Bound Protein 10; HFpEF—Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; HFrEF—Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction; IGF1R1—Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor 1; MAP4K4—Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase Kinase 4; MAPK10—Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 10; MLCK—Myosin Light Chain Kinase; mt-CytB—Mitochondrial Cytochrome B; PGC1α—Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1 Alpha; PIM1—Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase 1; PRKN—Parkin (E3 Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase); PTEN—Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog; SEPP1—Selenoprotein P; SMAD4—SMAD Family Member 4; SMAD7—SMAD Family Member 7; TGF1β—Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1.

miR-21, enriched in cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts, drives TGF-β-dependent proliferation and fibrosis [32,36,37,38] and targets SPRY1 to enhance fibroblast survival [32,39,40] and extracellular matrix synthesis [32,41,42,43]. In patients with aortic stenosis, plasma and myocardial miR-21 concentrations correlated with histological fibrosis and impaired global longitudinal strain, demonstrating a direct mechanistic link between miR-21-mediated fibrogenesis and diastolic dysfunction [44].

Members of the miR-29 family suppress the expression of fibrillin, collagen, and elastin [32,41,45]. Their downregulation accelerates matrix accumulation by modulating TGF-β/SMAD signaling through TGFβ2 and MMP2, while SMAD3 acts as a transcriptional inhibitor of miR-29 [32,46].

miR-208a/b, transcribed from MYH6/MYH7, contributes to maladaptive remodeling during isoform switching toward MYH7 in hypertensive HF [32,47,48]. Elevated miR-208b promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, AF onset, and fibrosis without stimulating proliferation [32,36], while stretch-activated miR-208a increases endoglin and collagen I production via TGF-β signaling [32,49].

Collectively, these miRNAs orchestrate the balance between injury and repair in cardiac tissue, influencing the degree of inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy that shapes the clinical trajectory of HF.

4. Diagnostic Applications of microRNAs in Heart Failure

Circulating miRNAs are increasingly recognized as valuable biomarkers for detecting HF at both early and advanced stages due to their remarkable stability in the bloodstream and their close involvement in key molecular pathways, ensured by encapsulation in extracellular vesicles or binding to protective proteins, is particularly advantageous for clinical practice [20,50]. Their integration into multimarker diagnostic strategies enhances the performance of established biomarkers such as NT-proBNP, soluble suppressor of tumorigenicity-2 (sST2), galectin-3, and high-sensitivity troponins, improving recognition of myocardial stress, fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cardiomyocyte injury [20,51,52]. When incorporated into liquid biopsy approaches, miRNAs offer molecular information beyond that provided by conventional tools and hold potential to improve sensitivity and specificity, particularly in heterogenous forms such as HFpEF where echocardiography and natriuretic peptides lack precision [20,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Numerous studies confirm that circulating miRNA profiles can effectively distinguish HF phenotypes (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

MicroRNAs with major diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic relevance in heart failure.

Combined miRNA panels consistently demonstrate strong diagnostic capacity, with AUC values often above 0.75 when differentiating HFpEF from healthy individuals and exceeding 0.80 when compared with HFrEF [54,95,96,97]. Their relevance is closely tied to their involvement in cardiac pathology, supporting their use for both detection and phenotype classification.

Among the best studied candidates, miR-21-5p displays distinct expression across HF types (Table 1). Levels are markedly lower in HFpEF than in HFrEF and correlate with diastolic dysfunction, myocardial hypertrophy, and NT-proBNP, showing early elevation before declining as disease progresses [54,63,64]. The let-7 family (let-7b-5p, let-7e-5p) also provides diagnostic information, the expression reflecting blood pressure, hypertrophy severity and remodeling, and displaying sex-related differences potentially linked to estrogen signaling [54,66,67].

A structured workflow has been introduced for miRNA biomarker development, including differential expression screening, phenotype correlation, discriminant model construction, and ROC validation [54,70,71,72]. Using this approach, a four-miRNA panel (let-7b-5p, let-7e-5p, miR-21-5p, and miR-140-3p) achieved AUC values above 0.9 in preclinical HFpEF and successfully differentiated HFpEF from healthy and HFrEF cohorts in clinical datasets [54,73] (Table 1). Meta-analytic data further support multi-marker strategies: for HFrEF, an eight-miRNA panel reached sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 88% (AUC 0.91), while a seven-miRNA signature for HFpEF achieved 82% sensitivity and 61% specificity (AUC 0.79) [20,74].

Among individual biomarkers, miR-423-5p remains the most consistently validated, correlating strongly with NT-proBNP and systolic function, and achieving AUC values around 0.86–0.91 in independent studies [20,59,60,61,75,98] (Table 1). Its stability despite comorbidities such as obesity and renal dysfunction strengthens its utility where natriuretic peptides may be misleading [60,61].

Several additional miRNAs hold diagnostic potential. A five-miRNA combination (miR-133a-3p, miR-378, miR-1-3p, miR-106b-5p, miR-133b) performed comparably to NT-proBNP and was linked to remodeling pathways such as MAPK, ErbB, and TGF-β [20,75]. In HFrEF, upregulation of multiple circulating miRNAs (miR 21-3p, miR 21-5p, miR 106b-5p, miR 23a-3p, miR 208a-3p, miR 1-3p, miR-126-5p, miR -133, and miR-223-3p) correlated with chamber dilation and hypertrophy [75], while experimental data indicate that miR-378 may suppress hypertrophy and fibrosis via MAPK/p38 inhibition [75,76]. More recently, miR-3135b, miR-3908, and miR-5571-5p have been identified as particularly promising markers, with discriminatory performance comparable or exceeding NT-proBNP and strong capacity to differentiate HFpEF [20,77] (Table 1).

Cardiomyocyte-derived miRNAs also serve as rapid diagnostic markers. MiR-1 and miR-133a are detectable within 1–3 h of ischemic onset, whereas miR-208b and miR-499 peak later. miR-499 achieves high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing ACS from stable ischemia and differentiating STEMI from NSTEMI [20,89].

In summary, circulating miRNAs constitute a layered biomarker system capable of distinguishing HF phenotypes, reflecting disease mechanisms and supporting risk stratification. Broader clinical implementation will require standardized processing, reduced inter-laboratory variability and validation in large, diverse patient cohorts, particularly considering comorbidities, sex-specific differences and heterogeneity of HF presentation [20,99]. Integrative multi-miRNA panels are expected to enhance diagnostic precision and enable more personalized management approaches.

5. Prognostic Applications of microRNAs in Heart Failure

Circulating miRNAs provide clinically relevant information for predicting outcomes, stratifying risk, and monitoring disease progression. Variations in their expression correlate with mortality, rehospitalization, response to therapy, and degree of cardiac remodeling, making them suitable prognostic tools across the HF spectrum (Supplementary Table S1) [20]. Low admission levels of miR-423-5p are associated with markedly higher mortality and rehospitalization [22,98], while miR-30d independently predicts adverse outcomes and contributes to assessing remodeling reversal during cardiac resynchronization therapy via MAP3K4-mediated hypertrophy modulation [20,79] (Table 1).

Distinct miRNA signatures can guide therapeutic response prediction. Decreased myocardial miR-208a-3p, miR-208b-3p, miR-21-5p, and miR-199a-5p, together with increased miR-1-3p, associate with favorable remodeling during β-blocker treatment [20,100]. In a large cohort, miR-132 independently predicted rehospitalization and enhanced risk stratification beyond standard models [20,80]. A five-miRNA panel (miR-26b-5p, miR-145-5p, miR-92a-3p, miR-30e-5p, and miR-29a-3p) characterized responders to resynchronization therapy [20,81], with protective roles reported for miRNA-26b and miR-145 against hypertrophy and apoptosis, while miRNA-29a-3p and miRNA-30e-5p reduce collagen deposition [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] (Table 1).

Population studies reinforce prognostic value. Elevated miR-21 and miR-29a associate with increased all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer mortality, while low miR-126 predicts higher overall mortality [32,101]. In hypertensive cardiomyopathy, six miRNAs (miR-16, miR-20b, miR-93, miR-106b, miR-223, miR-423-5p) rose with HF progression and correlated with NT-proBNP and MYH7 expression [32,48] (Table 1).

MiRNAs involved in microvascular dysfunction contribute to diastolic impairment and HFpEF. miR-30 family members drive oxidative stress and impaired nitric oxide signaling [32,102]; miR-34a-5p and miR-92a-3p rise in chronic HFpEF, particularly in metabolic disease, promoting endothelial–mesenchymal transition and vascular remodeling [32,103]. Reduced endothelial miR-126a associates with diminished cardiac output and aggravated microvascular rarefaction [32,104]. In Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, co-expression of miR-16 and miR-26a heightens catecholamine sensitivity, linking emotional stress to acute cardiac dysfunction [32,90] (Table 1).

Altogether, circulating miRNAs offer multidimensional prognostic insight into HF, often outperforming conventional biomarkers by capturing early molecular disturbances. Their integration into clinical assessment may enhance risk stratification, guide treatment decisions, and support long-term monitoring in HF management [20].

6. Therapeutic Applications of microRNAs in Heart Failure

Circulating miRNAs are emerging as responsive biomarkers that reflect the molecular effects of HF therapies and help distinguish treatment responders (Supplementary Table S1) [20]. Although no miRNA-based drugs have been approved yet, antisense inhibitors- and mimetic approaches hold promise, highlighted by the development of the locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified miR-132-3p inhibitor CDR132L, which has shown encouraging early clinical results [32].

Therapeutic modulation of miRNA expression is particularly evident with sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. In HFpEF with diabetes, empagliflozin markedly reduced miR-21 and miR-92a levels, with normalization accompanying improved endothelial function, while other dysregulated miRNAs (miR-126, miR-342-3p, miR-638) remained unchanged under metformin or insulin therapy [20,91,93]. Preclinical studies show that empagliflozin and dapagliflozin induce distinct miRNA responses, with empagliflozin increasing miR-146a and miR-34a and dapagliflozin elevating only miR-146a, indicating differing cardioprotective pathways [93,94] (Table 1).

ARNI therapy (sacubitril/valsartan) produces a characteristic miRNA pattern associated with reverse remodeling. In HFpEF, ARNI induced miR-29b-3p, miR-221-3p, and miR-503-5p, particularly in patients with high baseline expression, with changes correlating with functional and fibrosis-related indices [20,94]. Bioinformatic and experimental data suggest that these miRNAs converge on PI3K/AKT signaling, and suppression of miR-29b-3p enhances cardiomyocyte survival and associates with decreased septal thickness and improved global strain after therapy [20,94]. Overlap between drug-modulated pathways (e.g., dapagliflozin effects on TGF-β/SMAD and inflammasome signaling) and miRNA-regulated networks such as miR-29 and miR-21 highlights potential synergy between pharmacologic and miRNA-targeted interventions [32] (Table 1).

Overall, circulating miRNAs act as sensitive indicators of therapeutic response, mirror remodeling processes and endothelial recovery, and provide mechanistic insight into cardioprotective drug action. While promising, miRNA-based interventions remain in early stages, and their clinical translation is limited by challenges in delivery, potential off-target effects, and regulatory hurdles. Nevertheless, current evidence, including the modulation of miRNAs by SGLT2 inhibitors and ARNI therapy, highlights their capacity to provide mechanistic insights, identify treatment responders, and guide personalized therapy. Integration of circulating miRNAs into clinical evaluation, alongside conventional biomarkers, may support personalized therapy selection and guide future miRNA-based treatment strategies.

7. Conclusions

The study of miRNAs in the development of HF is a promising frontier in cardiology, offering new opportunities for both diagnosis and therapy. MiRNAs exert a significant influence on the regulation of genes involved in cardiomyocyte function, cardiac remodeling, and inflammatory processes. A deeper understanding of their mechanisms of action may facilitate the development of effective biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies capable of slowing HF progression and improving patients’ quality of life. Integrating miRNA profiling into clinical practice holds the potential to advance truly personalized therapeutic approaches, enabling drug selection and dosing to be tailored according to the molecular response of individual patients.

Nevertheless, current evidence is limited by substantial heterogeneity across HF phenotypes, differences in study populations, and variability in analytical platforms, all of which complicate comparisons and hinder clinical translation. The field continues to face major obstacles, including the need for rigorous standardization of miRNA extraction and quantification, persistent inter-laboratory variability, and the limited scope and methodological inconsistency of existing clinical trials. Many published studies remain exploratory, with inconsistent replication and limited longitudinal data, leaving important gaps in clinical validation. Future research should prioritize standardized measurement protocols, large prospective cohorts representing diverse HF phenotypes, and integrative analyses linking miRNA signatures with imaging, hemodynamic, and genetic data to clarify their prognostic and mechanistic relevance.

Despite their high specificity, circulating miRNAs should be considered complementary rather than alternative biomarkers. Their clinical implementation requires standardized detection methods, validation in large multicenter studies, and demonstration of added value when combined with established biomarkers, as part of a precision medicine approach to managing patients with HF [87].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262412085/s1. Refs. [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134] are cited in the Supplementary Materials file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G. and Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G., Y.T., A.C. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, I.G., Y.T., A.C. and G.A.; visualization, I.G., Y.T., M.P., A.C. and G.A.; supervision, M.P. and N.Z.; project administration, N.Z.; funding acquisition, N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 25-15-00020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS | Acute coronary syndrome |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFimpEF | Heart failure with improved ejection fraction |

| HFmrEF | Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PRS | Polygenic risk score |

References

- Roh, J.; Hill, J.A.; Singh, A.; Valero-Munoz, M.; Sam, F. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Heterogeneous Syndrome, Diverse Preclinical Models. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 1906–1925, Erratum in Circ Res. 2022, 131, e100. https://doi.org/10.1161/RES.0000000000000564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: A report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Rev. Esp. De Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 75, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Roger, V.L.; Weston, S.A.; Jiang, R.; Redfield, M.M. Longitudinal changes in ejection fraction in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Ma, T.; Su, Y.; Pan, X.; Huang, R.; Zhang, F.; Yan, C.; Xu, D. Heart Failure With Mid-range Ejection Fraction: Every Coin Has Two Sides. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 683418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, S.J.; Collier, T.J. Critical Appraisal of the 2018 ACC Scientific Sessions Late-Breaking Trials From a Statistician’s Perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zile, M.R.; Abraham, W.T.; Weaver, F.A.; Butter, C.; Ducharme, A.; Halbach, M.; Klug, D.; Lovett, E.G.; Müller-Ehmsen, J.; Schafer, J.E.; et al. Baroreflex activation therapy for the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction: Safety and efficacy in patients with and without cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Povysil, G.; Chazara, O.; Carss, K.J.; Deevi, S.V.V.; Wang, Q.; Armisen, J.; Paul, D.S.; Granger, C.B.; Kjekshus, J.; Aggarwal, V.; et al. Assessing the Role of Rare Genetic Variation in Patients With Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazara, O.; Dubé, M.-P.; Wang, Q.; Middleton, L.; Vitsios, D.; Walentinsson, A.; Wang, Q.-D.; Hansson, K.M.; Granger, C.B.; Kjekshus, J. Assessing the role of rare pathogenic variants in heart failure progression by exome sequencing in 8089 patients. Medrxiv Prepr. Serv. Health Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.W.; Raghavan, S.; Marquez-Luna, C.; Luzum, J.A.; Damrauer, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Willer, C.J.; Natarajan, P. Polygenic Risk Scores for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e93–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, N.; Koskela, J.T.; Ripatti, P.; Kiiskinen, T.T.J.; Havulinna, A.S.; Lindbohm, J.V.; Ahola-Olli, A.; Kurki, M.; Karjalainen, J.; Palta, P.; et al. Polygenic and clinical risk scores and their impact on age at onset and prediction of cardiometabolic diseases and common cancers. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Singh, J.; Bidasee, K.; Isaza, A.; Rupee, S.; Rupee, K.; Hanoman, C.; Adeghate, E.; Smail, M.M. Molecular and cellular biology and genetic factors in chronic heart failure. In Pathophysiology, Risk Factors, and Management of Chronic Heart Failure; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Khera, A.; Baum, S.J.; Gluckman, T.J.; Gulati, M.; Martin, S.S.; Michos, E.D.; Navar, A.M.; Taub, P.R.; Toth, P.P.; Virani, S.S.; et al. Continuity of care and outpatient management for patients with and at high risk for cardiovascular disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scientific statement from the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.A.; Abraham, G.; Inouye, M. Towards clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, R133–R142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, N.; Vargas, J.D.; Yang, C.; Cabrera, C.P.; Warren, H.R.; Fung, K.; Tzanis, E.; Barnes, M.R.; Rotter, J.I.; Taylor, K.D.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Left Ventricular Image-Derived Phenotypes Identifies Fourteen Loci Associated With Cardiac Morphogenesis and Heart Failure Development. Circulation 2019, 140, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Liu, P.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, F.; Tian, J. Myocardial protective effect and transcriptome profiling of Naoxintong on cardiomyopathy in zebrafish. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.T.; Huang, J.L.; Lin, P.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chung, F.P.; Liao, C.T.; Chiou, W.R.; Lin, W.Y.; Liang, H.W.; et al. Clinical impacts of sacubitril/valsartan on patients eligible for cardiac resynchronization therapy. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 3825–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulka, J.S.; Ashraf, M.; Bajwa, B.K.; Pare, G.; Laksman, Z. Current State and Future of Polygenic Risk Scores in Cardiometabolic Disease: A Scoping Review. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2023, 16, 286–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charidemou, E.; Felekkis, K.; Papaneophytou, C. From Natriuretic Peptides to microRNAs: Multi-Analyte Liquid Biopsy Horizons in Heart Failure. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, H.A.; Demir, M. MicroRNA and Cardiovascular Diseases. Balk. Med. J. 2020, 37, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Jin, J.P.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, Z.G.; Freedman, J.H.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, L. miRNAS in cardiovascular diseases: Potential biomarkers, therapeutic targets and challenges. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. Advances in MicroRNA therapy for heart failure: Clinical trials, preclinical studies, and controversies. Drugs Ther. 2025, 39, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.K.S.; Phua, Q.H.; Soh, B.S. Applications of miRNAs in cardiac development, disease progression and regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.E., Jr.; Kibiryeva, N.; Zhou, X.G.; Marshall, J.A.; Lofland, G.K.; Artman, M.; Chen, J.; Bittel, D.C. Noncoding RNA expression in myocardium from infants with tetralogy of Fallot. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2012, 5, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrello, E.R.; Johnson, B.A.; Aurora, A.B.; Simpson, E.; Nam, Y.J.; Matkovich, S.J.; Dorn, G.W., 2nd; van Rooij, E.; Olson, E.N. MiR-15 family regulates postnatal mitotic arrest of cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Feng, Y.; Liang, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, M.; Jiang, L.; Meng, W.; Cai, W.; et al. Loss of microRNA-128 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Prosperi, S.; Severino, P.; Myftari, V.; Correale, M.; Perrone Filardi, P.; Badagliacca, R.; Fedele, F.; Vizza, C.D.; Palazzuoli, A. MicroRNA and Heart Failure: A Novel Promising Diagnostic and Therapeutic Tool. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennel, P.J.; Schulze, P.C. A Review on the Evolving Roles of MiRNA-Based Technologies in Diagnosing and Treating Heart Failure. Cells 2021, 10, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Rubattu, S.; Volpe, M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doenst, T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Abel, E.D. Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: Implications beyond ATP production. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micu, M.A.; Cozac, D.A.; Scridon, A. miRNA-Orchestrated Fibroinflammatory Responses in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Translational Opportunities for Precision Medicine. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A. Epigenetics in heart failure phenotypes. BBA Clin. 2016, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, C.; Michaelsson, E.; Linde, C.; Donal, E.; Daubert, J.C.; Gan, L.M.; Lund, L.H. Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict Heart Failure Severity and Prognosis in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Holistic Proteomic Approach. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, S.; Mengozzi, A.; Velagapudi, S.; Mohammed, S.A.; Gorica, E.; Akhmedov, A.; Mongelli, A.; Pugliese, N.R.; Masi, S.; Virdis, A.; et al. Treatment with recombinant Sirt1 rewires the cardiac lipidome and rescues diabetes-related metabolic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka, A.; Badacz, R.; Okarski, M.; Wawak, M.; Przewłocki, T.; Podolec, J. Cardiac microRNAs: Diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Arch. Med. Sci. AMS 2023, 19, 1360–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, H.; Ge, D.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Gu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ge, T.; et al. Mir-21 Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis After Myocardial Infarction Via Targeting Smad7. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 42, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surina, S.; Fontanella, R.A.; Scisciola, L.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G.; Barbieri, M. miR-21 in Human Cardiomyopathies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 767064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardin, S.; Guasch, E.; Luo, X.; Naud, P.; Le Quang, K.; Shi, Y.; Tardif, J.C.; Comtois, P.; Nattel, S. Role for MicroRNA-21 in atrial profibrillatory fibrotic remodeling associated with experimental postinfarction heart failure. Circulation. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nun, D.; Buja, L.M.; Fuentes, F. Prevention of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): Reexamining microRNA-21 inhibition in the era of oligonucleotide-based therapeutics. Cardiovasc. Pathol. Off. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2020, 49, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.-L.; Yang, B.-F. Role of microRNAs in cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial fibrosis and heart failure. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2011, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegter, E.L.; van der Meer, P.; de Windt, L.J. MicroRNAs in heart failure: From biomarker to target for therapy. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2016, 18, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kura, B.; Kalocayova, B.; Devaux, Y.; Bartekova, M. Potential Clinical Implications of miR-1 and miR-21 in Heart Disease and Cardioprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, I.; Scatena, C.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Conte, L.; Pugliese, N.R.; Franceschi, S.; Lessi, F.; Menicagli, M.; De Martino, A.; Pratali, S.; et al. Micro-RNA-21 (biomarker) and global longitudinal strain (functional marker) in detection of myocardial fibrotic burden in severe aortic valve stenosis: A pilot study. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, L.T.; Sørensen, A.E.; Hardikar, A.A.; Joglekar, M.V. The microRNA-29 family: Role in metabolism and metabolic disease. Am. J. physiology. Cell Physiol. 2022, 323, C367–C377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, N.; Rao, P.; Wang, L.; Lu, D.; Sun, L. Role of the microRNA-29 family in myocardial fibrosis. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 77, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.H.; Li, J.L.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, S.X.; Jiao, Z.H.; Li, S.Q.; Liu, J.; Ding, J. miR-208a in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 773314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, B.A.; Semus, H.M.; Montgomery, R.L.; Stack, C.; Latimer, P.A.; Lewton, S.M.; Lynch, J.M.; Hullinger, T.G.; Seto, A.G.; van Rooij, E. Plasma microRNAs serve as biomarkers of therapeutic efficacy and disease progression in hypertension-induced heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-T.; Xu, M.-G. Potential link between microRNA-208 and cardiovascular diseases. J. Xiangya Med. 2021, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e895–e1032, Correction in Circulation 2022, 145, 18. Correction in Circulation 2022, 146, 13. Correction in Circulation 2023, 147, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topf, A.; Mirna, M.; Ohnewein, B.; Jirak, P.; Kopp, K.; Fejzic, D.; Haslinger, M.; Motloch, L.J.; Hoppe, U.C.; Berezin, A.; et al. The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Value of Multimarker Analysis in Heart Failure. An Approach to Biomarker-Targeted Therapy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 579567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvan, R.; Rolim, N.; Gevaert, A.B.; Cataliotti, A.; van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Adams, V.; Wisløff, U.; Silva, G.J.J.; the OptimEx Study Group. Multi-microRNA diagnostic panel for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in preclinical and clinical settings. ESC Hear. Fail. 2025, 12, 3028–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders-van Wijk, S.; Barandiarán Aizpurua, A.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Henkens, M.; Weerts, J.; Knackstedt, C.; Uszko-Lencer, N.; Heymans, S.; van Empel, V. The HFA-PEFF and H(2) FPEF scores largely disagree in classifying patients with suspected heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthahar, N.; Tschöpe, C.; de Boer, R.A. Being in Two Minds-The Challenge of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Diagnosis with a Single Biomarker. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Haase, T.; Zeller, T.; Schulte, C. Biomarkers for Heart Failure Prognosis: Proteins, Genetic Scores and Non-coding RNAs. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 601364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logeart, D. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: New challenges and new hopes. Presse Medicale 2024, 53, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijsen, A.J.; Creemers, E.E.; Moerland, P.D.; de Windt, L.J.; van der Wal, A.C.; Kok, W.E.; Pinto, Y.M. MiR423-5p as a circulating biomarker for heart failure. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumarulo, I.; De Prisco, A.; Salerno, E.N.M.; Ravenna, S.E.; Vaccarella, M.; Garramone, B.; Burzotta, F.; Aspromonte, N. New Frontiers of microRNA in Heart Failure: From Clinical Risk to Therapeutic Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.L.; Cameron, V.A.; Troughton, R.W. Circulating microRNAs as candidate markers to distinguish heart failure in breathless patients. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2013, 15, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seronde, M.F.; Vausort, M.; Gayat, E.; Goretti, E.; Ng, L.L.; Squire, I.B.; Vodovar, N.; Sadoune, M.; Samuel, J.L.; Thum, T.; et al. Circulating microRNAs and Outcome in Patients with Acute Heart Failure. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paim, L.R.; da Silva, L.M.; Antunes-Correa, L.M.; Ribeiro, V.C.; Schreiber, R.; Minin, E.O.Z.; Bueno, L.C.M.; Lopes, E.C.P.; Yamaguti, R.; Coy-Canguçu, A.; et al. Profile of serum microRNAs in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction: Correlation with myocardial remodeling. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzikovic, L.; Aryan, L.; Eghbali, M. Connecting sex differences, estrogen signaling, and microRNAs in cardiac fibrosis. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 97, 1385–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, A.; Liang, S.; Yu, L.; Shen, B.; Huang, Z. The association of serum hsa-miR-21-5p expression with the severity and prognosis of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 2025, 25, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, D.; Hong, C.; Chen, I.Y.; Lypowy, J.; Abdellatif, M. MicroRNAs play an essential role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.W.; Lou, X.Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.H. Let-7 in cardiovascular diseases, heart development and cardiovascular differentiation from stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 23086–23102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhao, M.; Yu, H.; Xu, W.; Wand, Z.; Xiao, H. Cardiomyocyte-derived small extracellular vesicle-transported let-7b-5p modulates cardiac remodeling via TLR7 signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.D.; Fang, X.H.; Zhu, J.N.; Yang, J.; Pan, R.; Yuan, S.J.; Zeng, N.; Yang, Z.Z.; Yang, H.; et al. Circular RNA circRNA_000203 aggravates cardiac hypertrophy via suppressing miR-26b-5p and miR-140-3p binding to Gata4. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkisto, P.; Dalgaard, L.T.; Belmonte, T.; Pinto-Sietsma, S.J.; Devaux, Y.; de Gonzalo-Calvo, D. Development of circulating microRNA-based biomarkers for medical decision-making: A friendly reminder of what should NOT be done. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2023, 60, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.; Saleem, A.; Hajjaj, M.; Faiz, H.; Pragya, A.; Jamil, R.; Salim, S.S.; Lateef, I.K.; Singla, D.; Ramar, R.; et al. Sex-specific differences in risk factors comorbidities, diagnostic challenges, optimal management, and prognostic outcomes of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A comprehensive literature review. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2024, 29, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamtani, M.R.; Thakre, T.P.; Kalkonde, M.Y.; Amin, M.A.; Kalkonde, Y.V.; Amin, A.P.; Kulkarni, H. A simple method to combine multiple molecular biomarkers for dichotomous diagnostic classification. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ríos, E.; Montesinos, L.; Alfaro-Ponce, M.; Pecchia, L. A review of machine learning in hypertension detection and blood pressure estimation based on clinical and physiological data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021, 68, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvan, R.; Hosseinpour, M.; Moradi, Y. Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the detection of heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2022, 10, e37929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, Z.; Ma, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J. Potential diagnostic value of circulating miRNAs in HFrEF and bioinformatics analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Y.; Yuan, L.; Ding, Z.; Wu, J.; Kang, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. MicroRNA-378 suppresses myocardial fibrosis through a paracrine mechanism at the early stage of cardiac hypertrophy following mechanical stress. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2565–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for heart failure. Hell. J. Cardiol. HJC Hell. Kardiol. Ep. 2018, 59, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Gao, R.; Bei, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jin, M.; Wei, S.; Wang, K.; Xu, X.; et al. Circulating miR-30d Predicts Survival in Patients with Acute Heart Failure. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 41, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melman, Y.F.; Shah, R.; Danielson, K.; Xiao, J.; Simonson, B.; Barth, A.; Chakir, K.; Lewis, G.D.; Lavender, Z.; Truong, Q.A.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA-30d Is Associated With Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy in Heart Failure and Regulates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis: A Translational Pilot Study. Circulation 2015, 131, 2202–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, S.; Batkai, S.; Beermann, J.; Bär, C.; Pfanne, A.; Thum, S.; Magnoli, M.; Balconi, G.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Tavazzi, L.; et al. Circulating microRNA-132 levels improve risk prediction for heart failure hospitalization in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marfella, R.; Di Filippo, C.; Potenza, N.; Sardu, C.; Rizzo, M.R.; Siniscalchi, M.; Musacchio, E.; Barbieri, M.; Mauro, C.; Mosca, N.; et al. Circulating microRNA changes in heart failure patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: Responders vs. non-responders. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Yang, Z.; Sayed, D.; He, M.; Gao, S.; Lin, L.; Yoon, S.; Abdellatif, M. GATA4 expression is primarily regulated via a miR-26b-dependent post-transcriptional mechanism during cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yan, G.; Li, Q.; Sun, H.; Hu, Y.; Sun, J.; Xu, B. MicroRNA-145 protects cardiomyocytes against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced apoptosis through targeting the mitochondria apoptotic pathway. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, A.M.; Steuerwald, N.M.; Walling, T.L.; Ghosh, S.; Li, T.; McKillop, I.H.; Russo, M.W.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Schrum, L.W. Inhibitory effects of microRNA 19b in hepatic stellate cell-mediated fibrogenesis. Hepatology 2012, 56, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnall, R.D.; Tsoutsman, T.; Shephard, R.E.; Ritchie, W.; Semsarian, C. Global microRNA profiling of the mouse ventricles during development of severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duisters, R.F.; Tijsen, A.J.; Schroen, B.; Leenders, J.J.; Lentink, V.; van der Made, I.; Herias, V.; van Leeuwen, R.E.; Schellings, M.W.; Barenbrug, P.; et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: Implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 170–178, 176p following 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soci, U.P.; Fernandes, T.; Hashimoto, N.Y.; Mota, G.F.; Amadeu, M.A.; Rosa, K.T.; Irigoyen, M.C.; Phillips, M.I.; Oliveira, E.M. MicroRNAs 29 are involved in the improvement of ventricular compliance promoted by aerobic exercise training in rats. Physiol. Genom. 2011, 43, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Komers, R.; Carew, R.; Winbanks, C.E.; Xu, B.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Koh, P.; Thomas, M.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Gregorevic, P.; et al. Suppression of microRNA-29 expression by TGF-β1 promotes collagen expression and renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2012, 23, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Ouatu, A.; Badescu, M.C.; Dima, N.; Ganceanu-Rusu, A.R.; Popescu, D.; Floria, M.; Rezus, E.; Rezus, C. Current Knowledge of MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Life 2021, 11, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, L.S.; Fiedler, J.; Chick, G.; Clayton, R.; Dries, E.; Wienecke, L.M.; Fu, L.; Fourre, J.; Pandey, P.; Derda, A.A.; et al. Circulating microRNAs predispose to takotsubo syndrome following high-dose adrenaline exposure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pocock, S.J.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Brueckmann, M.; Ofstad, A.P.; Pfarr, E.; Jamal, W.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H.; Dobrev, D.; Heijman, J. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor (ARNI) and Cardiac Arrhythmias. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mone, P.; Lombardi, A.; Kansakar, U.; Varzideh, F.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Pansini, A.; Marzocco, S.; De Gennaro, S.; Famiglietti, M.; Macina, G.; et al. Empagliflozin Improves the MicroRNA Signature of Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Diabetes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 384, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak-Kirmaci, H.; Hazar-Yavuz, A.N.; Polat, E.B.; Alsaadoni, H.; Cilingir-Kaya, O.T.; Aktas, H.S.; Elcioglu, H.K. Effects of empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, SGLT2 inhibitors, on miRNA expressions in diabetes-related cardiovascular damage in rats. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2025, 39, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.L.; Armugam, A.; Sepramaniam, S. Circulating microRNAs in heart failure with reduced and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2015, 17, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanakrishnan, R.; Ng, T.P.; Cameron, V.A.; Gamble, G.D.; Ling, L.H.; Sim, D.; Leong, G.K.; Yeo, P.S.; Ong, H.Y.; Jaufeerally, F.; et al. The Singapore Heart Failure Outcomes and Phenotypes (SHOP) study and Prospective Evaluation of Outcome in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (PEOPLE) study: Rationale and design. J. Card. Fail. 2013, 19, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.; Adamopoulos, S.; Anker, S.D.; Auricchio, A.; Böhm, M.; Dickstein, K.; Falk, V.; Filippatos, G.; Fonseca, C.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.A.; et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1787–1847, Erratum in Eur Heart J. 2013, 34, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pan, N.; An, Y.; Xu, M.; Tan, L.; Zhang, L. Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Myocardial Infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 617277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.; Alves, M.; Fischer, T.; Rolim, N. High-intensity interval training attenuates endothelial dysfunction in a Dahl salt-sensitive rat model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucharov, C.C.; Kao, D.P.; Port, J.D.; Karimpour-Fard, A.; Quaife, R.A.; Minobe, W.; Nunley, K.; Lowes, B.D.; Gilbert, E.M.; Bristow, M.R. Myocardial microRNAs associated with reverse remodeling in human heart failure. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e89169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Suzuki, K.; Fujii, R.; Kawado, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Iso, H.; Fujino, Y.; Wakai, K.; Tamakoshi, A. Circulating miR-21, miR-29a, and miR-126 are associated with premature death risk due to cancer and cardiovascular disease: The JACC Study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, S.; Njock, M.S.; Chandy, M.; Siraj, M.A.; Chi, L. MiR-30 promotes fatty acid beta-oxidation and endothelial cell dysfunction and is a circulating biomarker of coronary microvascular dysfunction in pre-clinical models of diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattih, B.; Fischer, A.; Muhly-Reinholz, M.; Tombor, L.; Nicin, L.; Cremer, S.; Zeiher, A.M.; John, D.; Abplanalp, W.T.; Dimmeler, S. Inhibition of miR-92a normalizes vascular gene expression and prevents diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2025, 198, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominic, K.L.; Schmidt, A.V.; Granzier, H.; Campbell, K.S.; Stelzer, J.E. Mechanism-based myofilament manipulation to treat diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1512550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Shao, X.; Zhang, X.; Han, Z.; Yang, C.; Li, X. Circulating microRNA-1 in the diagnosis and predicting prognosis of patients with chest pain: A prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 2019, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Luo, J.; Zhao, J.; Shang, D.; Lv, Q.; Zang, P. Combined Use of Circulating miR-133a and NT-proBNP Improves Heart Failure Diagnostic Accuracy in Elderly Patients. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 8840–8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Tian, L.; Sun, Q. Circulating microRNA-208 family as early diagnostic biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Su, T.; Li, H.; Huang, Q.; Wu, D.; Yang, C.; Han, Z. Circulating miR-499 are novel and sensitive biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvan, R.; Becker, V.; Hosseinpour, M.; Moradi, Y.; Louch, W.E.; Cataliotti, A.; Devaux, Y.; Frisk, M.; Silva, G.J.J. Prognostic and predictive microRNA panels for heart failure patients with reduced or preserved ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of Kaplan-Meier-based individual patient data. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gager, G.M.; Eyileten, C.; Postuła, M.; Nowak, A.; Gąsecka, A.; Jilma, B.; Siller-Matula, J.M. Expression Patterns of MiR-125a and MiR-223 and Their Association with Diabetes Mellitus and Survival in Patients with Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liao, R. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of miR-320a-3p in patients with chronic heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 2024, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Fu, G.; Li, Q.; Min, X.; Guo, Y. Circulating miRNA-21 as a diagnostic biomarker in elderly patients with type 2 cardiorenal syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Liu, D.; Zhu, W.; Su, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, P. Circulating MiR-17-5p, MiR-126-5p and MiR-145-3p Are Novel Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, X.S.; Fan, S.W.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Pei, H.J.; Qiu, L.; Zhuang, X.; Yang, C.H. Prognostic value of microRNAs in heart failure: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ji, W. Diagnostic and Prognostic Significance of serum miR-18a-5p in Patients with Atherosclerosis. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. Off. J. Int. Acad. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. 2021, 27, 10760296211050642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; He, Y.; Chen, W.; Shui, X.; Chen, C.; Lei, W. Circulating microRNA-19a as a potential novel biomarker for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 20355–20364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, R.L.; Liu, S.X.; Dong, S.H. Diagnostic value of circulating microRNA-19b in heart failure. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccini, J.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Cordelier, P.; Martins, F.; Maoret, J.J.; Bongard, V.; Ferrières, J.; Roncalli, J.; Elbaz, M.; Vindis, C. Circulating miR-155, miR-145 and let-7c as diagnostic biomarkers of the coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, S.; Ji, K.; Zhou, H.; Luo, C.; Sui, Y. Differentially expressed TUG1 and miR-145-5p indicate different severity of chronic heart failure and predict 2-year survival prognosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitry, M.O.; Soliman, Y.M.A.; ElKorashy, R.I.; Raslan, H.M.; Kamel, S.A.; Hassan, E.M.; Ahmed, F.E.; Yousef, R.N.; Awadallah, E.A. Role of micro-RNAs 21, 124 and other novel biomarkers in distinguishing between group 1 WHO pulmonary hypertension and group 2, 3 WHO pulmonary hypertension. Egypt. Heart J. (EHJ) Off. Bull. Egypt. Soc. Cardiol. 2023, 75, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhang, L. MicroRNAs and therapeutic potentials in acute and chronic cardiac disease. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, F. Analysis of the diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-9-5p in carotid artery stenosis. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2021, 21, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; He, Y. lncRNA ROR and miR-125b Predict the Prognosis in Heart Failure Combined Acute Renal Failure. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 6853939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scărlătescu, A.I.; Barbălată, T.; Sima, A.V.; Stancu, C.; Niculescu, L.; Micheu, M.M. miR-146a-5p, miR-223-3p and miR-142-3p as Potential Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiac Events in Young Patients with Acute ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction-Added Value over Left Ventricular Myocardial Work Indices. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, G.L.; Aguennouz, M.; Polito, F.; Oteri, R.; Russo, M.; Gentile, L.; Barbagallo, C.; Ragusa, M.; Rodolico, C.; Di Giorgio, R.M.; et al. Circulating microRNAs Profile in Patients With Transthyretin Variant Amyloidosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, M.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, L.; Bai, Z.; Wang, B.; Guo, Z.; Hou, A.; Li, H. MicroRNA-34a in coronary heart disease: Correlation with disease risk, blood lipid, stenosis degree, inflammatory cytokines, and cell adhesion molecules. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Mishra, S.; Rizvi, A.; Pradhan, A.; Perrone, M.A. Circulating microRNA-126 as an Independent Risk Predictor of Coronary Artery Disease: A Case-Control Study. Ejifcc 2021, 32, 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, D.; Lin, K. MicroRNA-221 is a potential biomarker of myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20191234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Li, W.W.; Wu, J.; Han, M.; Li, B.H. The diagnostic value of circulating microRNAs in heart failure. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 1985–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Meng, M.; Wei, J.; Wang, S. Long noncoding RNA PVT1 contributes to vascular endothelial cell proliferation via inhibition of miR-190a-5p in diagnostic biomarker evaluation of chronic heart failure. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 3348–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ma, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Qiu, D.; Zhou, K.; Hua, Y.; Li, Y. miRNAs as biomarkers for diagnosis of heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.; Zong, Z.; Xin, M.; Yang, K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of microRNA423-5p in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 19, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevchenko, O.; Velikiy, D.; Sharapchenko, S.; Gichkun, O.E.; Marchenko, A.V.; Ulybysheva, A.A.; Pavlov, V.S.; Mozheiko, N.P.; Koloskova, N.N.; Shevchenko, A.O. Diagnostic value of microRNA-27 and -339 in heart transplant recipients with myocardial fibrosis. Russ. J. Transplantology Artif. Organs 2021, 23, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Ebrahimi, S.R.; Rezabakhsh, A.; Aslanabadi, N.; Asadi, M.; Zafari, V.; Shanebandi, D.; Zarredar, H.; Enamzadeh, E.; Taghizadeh, H.; Badalzadeh, R. Novel diagnostic potential of miR-1 in patients with acute heart failure. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275019, Erratum in PLoS ONE. 2025, 20, e0320341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).