Abstract

MLASA2 is a rare mitochondrial disorder with limited geographic representation in published medical literature. Here, we report the first confirmed case of MLASA2 in a Latin American 16-year-old male harboring a homozygous pathogenic variant p.(Asp311Glu) in the YARS2 gene. The patient presented with sideroblastic anemia and short stature, accompanied by other skeletal dysplasia features not previously associated with MLASA2, including epiphyseal dysplasia, rib edge widening, and poorly defined vertebral structures, but without lactic acidosis. Notably, the patient did not present exercise intolerance but recently exhibited reduced muscle strength. The p.(Asp311Glu) variant, located in the anticodon-binding domain of the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (Mt-TyrRS), was consistently predicted to be pathogenic by multiple in silico tools. Molecular modeling revealed that this variant destabilizes the ‘KMSKS’ motif, potentially compromising tRNA recognition fidelity and aminoacylation efficiency. Analysis of runs of homozygosity (ROH) revealed significantly elevated consanguinity (ROH: 31.93%), consistent with a consanguineous mating between biological parents. This case expands the geographic distribution of MLASA2, documents previously unreported phenotypes, suggests a novel pathogenic mechanism, and demonstrates the utility of genomic approaches for diagnosing rare mitochondrial disorders in the absence of complete clinical information and family history.

1. Introduction

MLASA syndrome type 2 (MLASA2; OMIM # 613561) is a rare autosomal recessive mitochondrial disorder caused by pathogenic variants (PV) in the YARS2 gene, which encodes the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (mtTyrRS) [1]. Since the initial description of the disease by Riley (2010) [2], less than 40 cases have been reported worldwide, with predominant representation from Western Europe, North America, and Australia, and many of them of Lebanese descent [3,4]. To our knowledge, no confirmed cases of MLASA2 have been previously reported in Mexico or Latin America.

MLASA2 manifests with marked phenotypic heterogeneity, and diagnostic challenges frequently result in diagnostic delay. Classic clinical features include myopathy, lactic acidosis, sideroblastic anemia, and exercise intolerance [5]. However, heterogeneous presentations have been documented. Some cases present with isolated anemia and no other evident clinical manifestations and prolonged survival [4], whereas others manifest severe decompensation of cardiorespiratory function and short survival [6].

Here, we report the first MLASA2 case in the Mexican population carrying a homozygous PV in YARS2 gene. We also modeled the structural protein dysfunction caused by the pathogenic variant and analyzed runs of homozygosity (ROH) to assess for consanguinity due to the absence of biological parents.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Case Presentation

The male case reported here was born at 35 weeks of gestation with an Apgar score of three at 1 min, five at 5 min, and eight after 10 min. He was adopted at 14 days of age; hence, his familial history was unavailable. Gross motor development included neck control at 3 months, trunk control at 6 months, crawling at 8 months, and walking at 18 months. Meanwhile, fine motor development began at 4 months and speech milestones at 2 years.

At 11 years old, the patient was referred to a Genetic Clinic presenting with epiphyseal dysplasia, metaphyseal widening and irregularity, widening of rib edges, poorly defined vertebral structures, scoliosis, and genu valgum. At the same age, laboratory tests revealed low alkaline phosphatase serum levels (119 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] 140 U/L (at lower normal end; reference values 235–470), and slightly increased levels of serum phosphorus (5.9 mg/dL; reference < 4.5 mg/dL) with normal calcium and parathormone levels. The patient presented moderate-severe normocytic–normochromic anemia (Hb 7 g/dL), two bone marrow aspirates confirmed sideroblastic rings without evidence of myeloproliferative cause, and thrombocytopenia was detected (<100,000/μL).

At 13 years old, the patient exhibited short stature (percentile < 3), low hairline implantation, horizontal palpebral fissures, high nasal root, dorsal nasal hump with depressed tip, dental malocclusion and crowding, posteriorly rotated ears with hypoplastic antihelix and deep concha, limited elbow extension and pronation–supination, and left-predominant genu valgum. No ocular, neurological, cardiovascular, or respiratory signs and symptoms were identified during the physical examination. However, the patient presented with their most severe anemia episode (Hb 4 g/dL) requiring two transfusions. A clinical exome panel, including variants in 109 genes causing skeletal dysplasia, was performed, and the results were negative.

At 15 years old, the patient was referred to our institution, and Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) revealed a homozygous PV located in the YARS2 gene [chr12:32906866 G>C (GRCh37); c.933C>A; p.(Asp311Glu)], found in the anticodon-binding domain of mtTyrRS.

At present, at the age of 16 years, the patient no longer presents with anemia (Hb = 12.5 g/dL) and is currently managed only with folic acid supplementation, demonstrating non-transfusion dependence; however, he continues to have mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count of 89,000/μL). Cardiological evaluation revealed no cardiomyopathy and serum lactate levels were 1.4 mmol/L (normal range 0.7–2.1). In the last evaluation (April 2025), the patient exhibited decreased muscle strength in the upper extremities (4/5 bilaterally) and lower extremities (right 4/5, left 3/5). However, neither intolerance to exercise, fatigue, nor tiredness were referred to during the interview. No muscle biopsy nor additional enzymatic study was accepted by the patient’s legal guardians. Imaging studies demonstrated left-sided acetabular–femoral dysplasia with neoacetabulum formation and the genu varum predominantly affecting the left knee (15 degrees versus 10 degrees on the right). The patient is currently scheduled to undergo osteotomy to correct the acetabulum–femoral deformity. No additional information regarding the 24 h food recall and the food frequency questionnaire could be obtained from the legal guardians. Since Ardissone et al. [7] described two Italian siblings harboring the same PV identified in our patient, and Riley reported another case [4], we present a comparison of their clinical manifestations in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative clinical features of MLASA2 cases (YARS2 p.(Asp311Glu)).

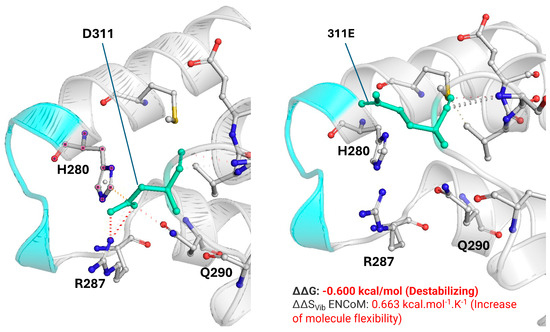

2.2. In Silico Prediction of Pathogenicity

In silico prediction tools classified the p.(Asp311Glu) variant as damaging (SIFT), probably damaging (PolyPhen-2), disease-causing (MutationTaster), deleterious (FATHMM), possibly pathogenic (M-CAP score), and pathogenic (MutPred2) [Table A1]. To deepen the impact of PV p.(Asp311Glu) on protein structure and stability, we evaluated the changes in interactions between residue 311 and near amino acids using DynaMut2 and PyMOL3.1. In wild-type YARS2, the D311 amino acid interacts with H280, R287, and Q290, contributing to the stability of the ‘KMSKS’ motif. This region is crucial for maintaining the fidelity of tRNA recognition and for the efficient catalysis of the aminoacylation reaction, helping to coordinate the transfer of the amino acid to its cognate tRNA [8]. In the mutated YARS2 [311E], these interactions are lost due to the disruption of ionic bonds and van der Waals forces. It results in a loss of stability in the ‘KMSKS’ motif demonstrated with the parameters of the stability and flexibility of the protein [ΔΔG and ΔΔSVib, respectively] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural comparison of the wild-type Asp311 and mutant Glu311 residues and their impact on the KMSKS motif of YARS2. Left: wild-type Asp311 (D311, green) within the anticodon-binding domain, showing its spatial relationship with the KMSKS loop (cyan) and neighboring residues His280, Arg287, and Gln290. Right: mutant Glu311 (311E, green) modeled at the same coordinates, displaying changes in the side chain that alter local packing and the interaction network around the KMSKS motif. DynaMut2 predicts a destabilizing effect for the p.(Asp311Glu) substitution with ΔΔG = −0.600 kcal/mol and an increase in molecular flexibility with ΔΔSVib ENCoM = +0.663 kcal·mol−1·K−1. The ΔΔG for other pathogenic variants such as p.(Gly46Asp) [catalytic domain], p.(Cys369Tyr) [anticodon-binding domain], and Gly244Ala [catalytic domain] are −0.84 kcal/mol, −0.82 kcal/mol, and −0.52kcal/mol, respectively.

2.3. p.(Asp311Glu) PV Interpretation According to ACMG/AMP

According to the criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), the p.(Asp311Glu) PV fulfills two strong criteria (PS1 and PS3), one moderate (PM2), and two supporting [PP3 and PS3_supporting], classifying it as pathogenic (Table 2). Functional evidence (PS3) comes from Ardissone’s study, which showed that carriers of the pathogenic variant p.(Asp311Glu) had reduced activity of complexes I, III, and IV of oxidative phosphorylation in muscle tissue [7].

Table 2.

p.(Asp311Glu) PV interpretation according to ACMG/AMP.

2.4. Estimation of Runs of Homozygosity (ROH)

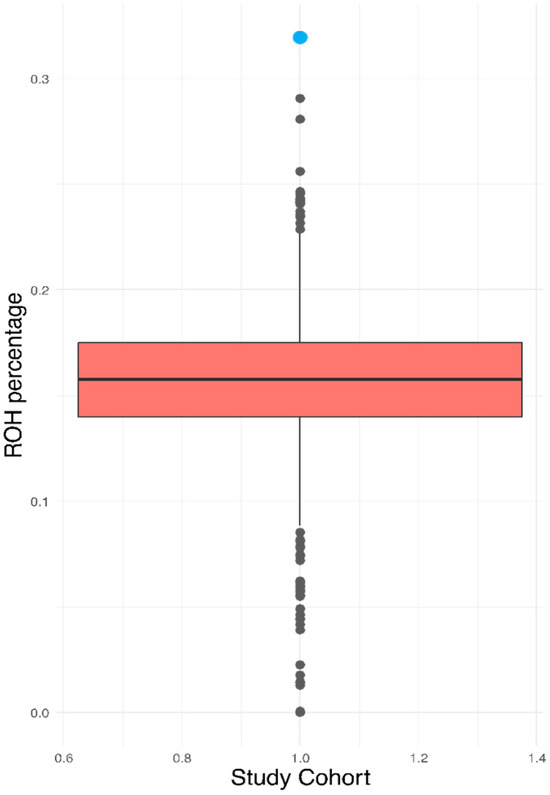

Since the patient’s biological parents were unavailable for genealogical evaluation, we estimated the ROH as a proxy for consanguinity, considering that an offspring of a first-degree parental relationship typically leads to ROH values that exceed 25%. The ROH value for the index case was 31.93%, significantly higher than that exhibited in the reference cohort of 2217 Mexicans (16.05 ± 2.59%) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the ROH values of the case [blue] and the total population.

3. Discussion

In rare genetic disorders, the convergence of multiple clinical manifestations often presents a complex puzzle that challenges medical practitioners to uncover the specific diagnosis and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms [9], especially in clinical scenarios where all clinical features are not explained by one syndrome or disease.

Although the patient analyzed here presented transfusion-dependent sideroblastic anemia and lactic acidosis, two of the main characteristics of MLASA2 [10], he did not present exercise intolerance, nor was suspected of having myopathy. Instead, the patient displayed skeletal abnormalities not previously reported in MLASA2, including epiphyseal dysplasia, widening of the metaphysis, irregularity and widening of rib cages, poorly defined vertebral structures, scoliosis, genu valgum, and elevated serum phosphorus. These clinical features initially suggested bone dysplasia, delaying the accurate diagnosis. After WES, the homozygous PV p.(Asp311Glu) in YARS2 was identified, reaching the precise diagnosis, and suggesting a phenotypic expansion of MLASA2 toward some skeletal abnormalities, such as epiphyseal dysplasia, widening of the metaphysis, irregularity and widening of rib cages, and poorly defined vertebral structures, because scoliosis was previously reported by Riley in a patient harboring another PV [p.(Phe52Leu)]. An explanation for the skeletal phenotypes of the index case might be found in a study by Holzer et al., who demonstrated in mice that postnatal inactivation of the respiratory chain in chondrocytes disorganizes the growth plate, precipitating premature closure, metaphyseal/epiphyseal defects, and short stature [11]. However, we cannot exclude other genetic and environmental factors contributing to the patient’s skeletal phenotypes, as no whole-genome sequencing was performed, and we cannot rule out the exposure to other environmental factors that can disrupt growth plate function during the antenatal or early postnatal period, because of the limited information associated with the adoption of the patient.

The hemoglobin level in our patient [7 g/dL] was similar to that reported by Riley [4] in a Dutch male patient [6.6 g/dL] and by Ardissone et al. [7] in an Italian male [5.2 g/dL], but lower than that of the latter’s sister [10.5 g/dL], suggesting the influence of additional factors on anemia severity. Furthermore, although our patient presented with anemia during adolescence, as in the case reported by Riley at 13 years old, the two cases reported by Ardissone et al. [7] presented it during the first two months of life. A similar pattern was observed for lactic acidosis, which is absent in our index case, whereas in the Italian cases it occurred during infancy and in the Dutch patient at 13 years of age (Table 1). Other PVs in YARS2 exhibited the same extreme phenotypic differences in the timing of anemia and lactic acidosis onset. For example, some carriers of p.(Phe52Leu) present anemia during the first months of life [2], whereas others develop anemia at 14 years of age [4]. Also, although lactic acidosis is a universal feature of p.(Phe52Leu) carriers [2,4,12], it is present in only 50% of those with p.(Leu392Ser), suggesting that variable expressivity is not exclusive of the p.(Asp311Glu), and that it does not depend on the domain where the PV is located, since patients carrying PV in the anticodon-binding or the catalytic domain do no present lactic acidosis [3,4,5].

In our patient, hemoglobin levels normalized after transfusions and subsequent folic acid supplementation alone, suggesting that adequate folate availability may enhance compensatory erythropoiesis despite the underlying mitochondrial defect [13]. While this observation does not imply disease modification, it raises the possibility that folic acid could serve as a useful supportive cofactor in selected individuals with YARS2-related MLASA2. Folic acid is a cofactor required for the synthesis of purines and thymidylate, and thus for proper DNA and RNA production during rapid proliferation of erythroid precursors [14]. Even in sideroblastic anemias where mitochondrial dysfunction, and not folate deficiency, is the primary pathology, increased erythropoietic turnover can raise folate requirements, and supplementation may support more efficient maturation of red-cell precursors by optimizing nuclear division and reducing ineffective erythropoiesis. However, Riley reported two cases of patients with MLASA2 who did not respond to folic acid therapy [2,4], and current evidence on the efficacy of folic acid for congenital sideroblastic anemia is unclear. For example, whereas LeBlanc et al. reported amelioration of congenital sideroblastic anemia with the administration of glycine plus folic acid in animal models, the transfusion requirement was not resolved in three patients with PV in the SLC25A38 gene [15]. Cox and colleagues supplemented pyridoxin plus folic acid in three subjects with congenital X-linked sideroblastic anemia, achieving hemoglobin control that relapsed after discontinuation of supplementation and remitted after re-administration of pyridoxin [16]. Thus, folate supplementation might be a co-adjuvant therapy in sideroblastic anemia to meet the high folate demand associated with increased erythropoiesis. In any case, future studies should identify the optimal therapy and cofactors for achieving an optimal response in congenital sideroblastic anemia caused by YARS2 mutations and determine whether the anemia is self-limited.

Even if at present our patient has no clinical evidence of lactic acidosis, fatigue, or low physical performance, we cannot discard the future presentation of clinically recognizable myopathy and lactic acidosis during resting or exercise as presented by the male Dutch patient carrying p.(Asp311Glu) PV and by other patients harboring p.(Leu61Val) and [p.Gly191Val];[p.(Ile454Serfs*10] PV whose carriers developed lactic acidosis only during exercise [4]. For this reason, a timely follow-up will be mandatory, and the prescription of riboflavin and coenzyme Q10 will be suggested to the patient’s primary care physician, as it could enhance muscle function by improving mitochondrial mass and electron flow in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [17,18].

Although we cannot demonstrate the mechanisms underlying heterogeneity in the clinical presentation, some factors may be involved, including modifier genes, differences in mitochondrial haplogroups, tissue-specific mitochondrial thresholds, and nutritional and environmental factors. Modifier genes are mechanisms proposed in other recessive diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, for explaining variable expressivity [19]. Mexicans, when compared to Italians and Dutch, have different mitochondrial haplogroups (mH) [A2, B2, C1, D1 in Mexicans and H, U, J, T, K in Caucasians] that might influence the baseline respiratory efficiency, ROS management, and compensatory capacity; however, differences in oxidative phosphorylation, ATP, and ROS generation have, up until now, only been proved in cell models of some mH (H, J, T) [20] and for some mitochondrial diseases such as Leber’s optic neuropathy whose risk is modified by mH [21]. Tissue-specific biochemical–metabolical mitochondrial thresholds are a well-established concept whereby different organs manifest dysfunction only when oxidative phosphorylation drops below a critical level [22]; hence, it is possible that during developmental transitions such as pubertal growth, the increased metabolic demands may unmask latent mitochondrial insufficiency, contributing to disease presentation in patients with mitochondrial diseases, as in our index case. On the other hand, nutritional factors might mask disease presentation, as the administration of riboflavin and coenzyme Q10 appears to contribute to a better clinical evolution in a boy harboring p.(Asp311Glu) PV [7].

Although it was impossible to construct the patient’s family tree, the exceptional high ROH (31.93%) suggests inbreeding, since the ROH value was higher than the threshold defined for first-degree relatives (25%) [23], exceeding even those reported in two Mexican indigenous groups where endogamy and consanguinity are frequent because of the small population size and geographic and cultural isolation [24].

The in silico structural analysis revealed previously unexplored potential mechanisms of pathogenicity associated with p.(Asp311Glu). Our prediction indicated that this PV decreased the stability of the TyrRS ‘KMSKS’, a crucial motif for maintaining the fidelity of tRNA recognition [8] and for the efficient catalysis of the aminoacylation reaction [25].

The p.(Asp311Glu) PV fulfills criteria for being classified as pathogenic (two strong criteria, one moderate, and two supporting criteria) according to the ACMG/AMP [26]. PS3 (strong) is fulfilled because a previously reported patient carrying the same YARS2 p.(Asp311Glu) variant underwent well-established functional studies demonstrating a clear deleterious effect on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Specifically, a markedly reduced activity of respiratory chain complexes I, III, and IV (13%, 18%, and 15% of mean control values, respectively), and Seahorse-based oxygraphy in fibroblasts revealed a profound reduction in maximal respiratory capacity (28% of controls) [7]. These findings provide direct experimental evidence that the p.(Asp311Glu) substitution disrupts mitochondrial bioenergetics, fully satisfying the ACMG/AMP definition of PS3. PS1 (strong) is fulfilled because the variant identified in our patient results in the same amino acid change as previously established pathogenic variants reported in individuals with MLASA2, indicating that this substitution has been unequivocally associated with disease in independent cases. Such facts, in combination with the robust in silico analysis supporting pathogenicity (PP3) and the absence in population databases, including gnomAD (PP3), suggest that p.(Asp311Glu) is pathogenic.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, including the lack of a muscle biopsy to evaluate respiratory chain activity, as subclinical mitochondrial myopathy may be present despite clinical silence. Furthermore, the failure to study the patient’s biological family limits our ability to determine variant segregation and potential carrier status among relatives. Furthermore, the absence of detailed metabolic profiling (plasma organic acids, carnitine profile) limits the complete characterization of mitochondrial dysfunction.

4. Materials and Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2024). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for participation in the study, for genetic testing, and for publication of anonymized clinical and genetic data. All identifying information has been removed to preserve patient confidentiality.

A complete clinical evaluation of the index case was performed, focusing on clinical phenotypes and relevant symptoms. The genetic tree was not constructed because the biological parents of the affected individual were unavailable. The patient’s legal guardians did not consent to additional examinations, such as biopsy and enzymatic activity measurements, or to measurements of biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction, such as acylcarnitines, plasma amino acids, or CoQ10 levels.

WES was performed as previously described [27]. Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA blood specimens using a standard protocol. Exome capture was performed using the xGen Exome Research Panel v2 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA), and sequencing was performed using NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing reads were uniquely aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) and Revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS) of the mitochondrial genome, generating 198.84 mean depth-of-coverage within the captured region. Approximately 99.10% of the targeted bases were covered to a depth of ≥20x. Variant interpretation was performed using EVIDENCE v.1 (https://3billion.io/variant-interpretation, 1 December 2022) [28] and GEBRA v.1 (https://3billion.io/gebra/, 1 December 2022), proprietary software to prioritize and interpret variants based on the guideline recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) [29] in the context of the patient’s phenotype, relevant family history, and previous test results.

To assess the pathogenicity of variants we used several in silico tools, including SIFT v4.0.4 (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/, 1 August 2025), PolyPhen v2.0 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/, 1 August 2025), MutationTaster 2025 (https://www.mutationtaster.org/, 1 August 2025), Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models [FATHMM] v2.3 (http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk/, 1 August 2025), Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion [CADD] v1.7 (https://cadd.bihealth.org/, 1 August 2025), Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity [M-CAP] score (http://bejerano.stanford.edu/mcap/, 1 August 2025), MutPred2 (http://mutpred.mutdb.org/, 1 August 2025), and Local Indicator of Statistical Dependence using Spatial Smoothing [LIST-S2] v.1 (https://list-s2.msl.ubc.ca, 1 August 2025).

Structural impact of the PV on the protein stability was evaluated selecting the best PDB available [2PID; obtained by X-ray crystallography] and was used to estimate the ΔΔG, ΔΔG ENCoM, and the ΔΔSVib in DynaMut2 (https://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/dynamut/, 1 August 2025). The model generated was visualized and customized in PyMOL3.1 (https://www.pymol.org/, 1 August 2025). DynaMut2 was run with default parameters, including force-field energy minimization for 5 ns at 300K.

Because of the unavailability of the patient’s biological parents, runs of homozygosity (ROH) were estimated using PLINK as previously described [24]. ROH was calculated in the patient, employing as a reference the Mexican DMS2 cohort of 2217 individuals [30]. The ROH cut-off values to estimate consanguineous mating were 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, and 1.56%, from first to fourth degrees, respectively [23].

5. Conclusions

The present case highlights the usefulness of genomic tools, such as next-generation sequencing, for enabling precision diagnosis and personalized medicine, as they facilitate the detection of disease-causing mutations, especially when clinical manifestations do not fit into an evident disorder. This study expands the knowledge of MLASA2 syndrome by describing the first Latin American individual affected and potentially new skeletal dysplasia features that have not been previously reported. Additionally, we provide new mechanistic insights into pathogenicity and employ ROH-based estimates to evaluate consanguinity in the absence of biological parents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.V.-B., F.B.-O. and L.O.; methodology, J.R.V.-B., F.B.-O. and H.G.-O.; software, J.R.V.-B. and H.G.-O.; validation, H.G.-O., A.M.-H. and C.C.-C.; formal analysis, J.R.V.-B.; investigation, I.G.-C.; resources, H.L., G.H.S., J.R.-H. and A.C.; data curation, I.G.-C. and C.C.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.V.-B.; writing—review and editing, H.G.-O., A.M.-H., C.C.-C., J.R.-H., H.G.-O., F.B.-O., A.C. and L.O.; visualization, J.R.V.-B. and I.G.-C.; supervision, L.O.; project administration, J.R.V.-B.; funding acquisition, H.L., G.H.S., F.B.-O. and L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The exome sequencing was funded by 3billion, Inc., “2nd End the Diagnostic Odyssey Grant”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (#489, approval date 11 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We acknowledge the legal guardians of the patient as well as all technical personnel and students who contributed to the performance of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors from the INMEGEN declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. H.L. and G.H.S. are employees of 3billion Inc.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| AMP | Association for Molecular Pathology |

| CADD | Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CRIT | Centro de Rehabilitación Infantil Teletón |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DMS2 | Diabetes in Mexico Study 2 |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| FATHMM | Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models |

| GEBRA | Genetic Evidence BRowsing and Analysis |

| GRCh37 | Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| LIST-S2 | Local Indicator of Statistical Dependence using Spatial Smoothing |

| MLASA | Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia |

| MLASA2 | Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia Type 2 |

| mtTyrRS | Mitochondrial Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase |

| M-CAP | Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity score |

| MutPred2 | Mutation Prediction 2 (pathogenicity prediction tool) |

| n.d. | Not Determined |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PUS1 | Pseudouridine Synthase 1 gene |

| PV | Pathogenic Variant |

| RC | Respiratory chain |

| ROH | Runs of Homozygosity |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| rCRS | Revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (mitochondrial genome) |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| SIFT | Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (in silico predictor) |

| tRNA | Transfer Ribonucleic Acid |

| TyrRS | Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing |

| ΔΔG | Change in Gibbs Free Energy (protein stability difference) |

| ΔΔSVib | Change in Vibrational Entropy (protein flexibility difference) |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variant Effect Predictors of YARS2 p.(Asp311Glu).

Table A1.

Variant Effect Predictors of YARS2 p.(Asp311Glu).

| Tool | Prediction | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| SIFT | 0.000 | Damaging |

| Polyphen2 | 0.999 | Probably damaging |

| Mutation taster | 0.99789 | Disease causing |

| FATHMM | 0.14848 | Deleterious |

| Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity (M-CAP) Score | 0.561 | Possibly pathogenic |

| MutPred2 | 0.628 | Pathogenic |

| LIST-S2 | 0.91221 | Deleteriousness effect |

| CADD | 17.39 | Deleterious |

| ESM1b | −11.8056 | Deleterious |

| Alphafold score | 0.7814 | Pathogenic |

References

- McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University. Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia 2; MLASA2—Entry—# 613561 OMIM. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/613561 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Riley, L.G.; Cooper, S.; Hickey, P.; Rudinger-Thirion, J.; McKenzie, M.; Compton, A.; Lim, S.C.; Thorburn, D.; Ryan, M.T.; Giegé, R.; et al. Mutation of the Mitochondrial Tyrosyl-TRNA Synthetase Gene, YARS2, Causes Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia--MLASA Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 87, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, E.W.; Ng, Y.S.; Alston, C.L.; Dallabona, C.; Gilberti, M.; He, L.; Knowles, C.; Chin, S.L.; Schaefer, A.M.; Falkous, G.; et al. Clinical Features, Molecular Heterogeneity, and Prognostic Implications in YARS2-Related Mitochondrial Myopathy. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, L.G.; Heeney, M.M.; Rudinger-Thirion, J.; Frugier, M.; Campagna, D.R.; Zhou, R.; Hale, G.A.; Hilliard, L.M.; Kaplan, J.A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; et al. The Phenotypic Spectrum of Germline YARS2 Variants: From Isolated Sideroblastic Anemia to Mitochondrial Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis and Sideroblastic Anemia 2. Haematologica 2018, 103, 2008–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.; Hopton, S.; Dallabona, C.; Gilberti, M.; Falkous, G.; Norwood, F.; Donnini, C.; Gorman, G.S.; Clark, B.; Taylor, R.W.; et al. Sideroblastic Anemia with Myopathy Secondary to Novel, Pathogenic Missense Variants in the YARS2 Gene. Haematologica 2018, 103, e564–e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudaks, L.I.; Watson, E.; Oboudiyat, C.; Kumar, K.R.; Sullivan, P.; Cowley, M.J.; Davis, R.L.; Sue, C.M. Decompensation of Cardiorespiratory Function and Emergence of Anemia during Pregnancy in a Case of Mitochondrial Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia 2 with Compound Heterozygous YARS2 Pathogenic Variants. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2022, 188, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardissone, A.; Lamantea, E.; Quartararo, J.; Dallabona, C.; Carrara, F.; Moroni, I.; Donnini, C.; Garavaglia, B.; Zeviani, M.; Uziel, G. A Novel Homozygous YARS2 Mutation in Two Italian Siblings and a Review of Literature. JIMD Rep. 2015, 20, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadavalli, S.S.; Ibba, M. Quality Control in Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthesis Its Role in Translational Fidelity. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2012, 86, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.E.; Singleton, K.S.; Wallin, M.; Faundez, V. Rare Genetic Diseases: Nature’s Experiments on Human Development. iScience 2020, 23, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbal, A.; Avissar, N.; Shaklai, M.; Kuritzky, A.; Schejter, A.; Ben-David, E.; Shanske, S.; Garty, B.Z. Myopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Sideroblastic Anemia: A New Syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995, 55, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, T.; Probst, K.; Etich, J.; Auler, M.; Georgieva, V.S.; Bluhm, B.; Frie, C.; Heilig, J.; Niehoff, A.; Nüchel, J.; et al. Respiratory Chain Inactivation Links Cartilage-Mediated Growth Retardation to Mitochondrial Diseases. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 1853–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahni, R.; Wedatilake, Y.; Cleary, M.A.; Lindley, K.J.; Sibson, K.R.; Rahman, S. A distinct mitochondrial myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA) phenotype associates with YARS2 mutations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2013, 161A, 2334–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, C.; Larson, E.A.; Wang, M. Mechanisms of genome instability from cellular folate stress. J Cell Biol. 2025, 224, e202502205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, M.J.; Ponka, P. New insights into erythropoiesis: The roles of folate, vitamin B12, and iron. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, M.A.; Bettle, A.; Berman, J.N.; Price, V.E.; Pambrun, C.; Yu, Z.; Tiller, M.; McMaster, C.R.; Fernandez, C.V. Study of Glycine and Folic Acid Supplementation to Ameliorate Transfusion Dependence in Congenital SLC25A38 Mutated Sideroblastic Anemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1307–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.C.; Bottomley, S.S.; Wiley, J.S.; Bawden, M.J.; Matthews, C.S.; May, B.K. X-linked pyridoxine-responsive sideroblastic anemia due to a Thr388-to-Ser substitution in erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, B.; Li, D.; Shan, J.; Liu, S.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, P.; Zheng, J.; Li, D.; Gong, Y.; et al. Increased muscle coenzyme Q10 in riboflavin responsive MADD with ETFDH gene mutations due to secondary mitochondrial proliferation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013, 109, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergheen, V.; Chalasani, A.; Wainwright, L.; Yubero, D.; Montero, R.; Artuch, R.; Hargreaves, I. Coenzyme Q10 in the Treatment of Mitochondrial Disease. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2017, 5, 2326409817707771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumm, M.L.; Konstan, M.W.; Schluchter, M.D.; Handler, A.; Pace, R.; Zou, F.; Zariwala, M.; Fargo, D.; Xu, A.; Dunn, J.M.; et al. Genetic modifiers of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.E.; Brunner, S.M.; Mayr, J.A.; Stanger, O.; Sperl, W.; Kofler, B. Functional differences between mitochondrial haplogroup T and haplogroup H in HEK293 cybrid cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Durán, A.; Pacheu-Grau, D.; Martínez-Romero, I.; López-Gallardo, E.; López-Pérez, M.J.; Montoya, J.; Ruiz-Pesini, E. Oxidative phosphorylation differences between mitochondrial DNA haplogroups modify the risk of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, R.; Malgat, M.; Mazat, J.P.; Letellier, T. Threshold effect and tissue specificity. Implication for mitochondrial cytopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 33426–33432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, K.L.; Zimmerman, S.L.; Thomas, C.; Mitchell, A.L.; Prada, C.E.; Grote, L.; Bao, L.; Martin, L.J.; Smolarek, T.A. Regions of Homozygosity Identified by SNP Microarray Analysis Aid in the Diagnosis of Autosomal Recessive Disease and Incidentally Detect Parental Blood Relationships. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ortiz, H.; Barajas-Olmos, F.; Contreras-Cubas, C.; Cid-Soto, M.Á.; Córdova, E.J.; Centeno-Cruz, F.; Mendoza-Caamal, E.; Cicerón-Arellano, I.; Flores-Huacuja, M.; Baca, P.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of Mexican Indigenous Populations Brings Insights into the Peopling of the Americas. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turvey, A.K.; Horvath, G.A.; Cavalcanti, A.R.O. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in human health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1029218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.M.; Biesecker, L.G.; Rehm, H.L. Overview of Specifications to the ACMG/AMP Variant Interpretation Guidelines. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2019, 103, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Seo, G.H.; Hyun, S.I.; Kwon, K.; Ryu, S.W.; Khang, R.; Lee, E.; Kim, J.H.; Song, Y.; Jeong, W.C.; et al. Exome Sequencing of 18,994 Ethnically Diverse Patients with Suspected Rare Mendelian Disorders. NPJ Genom. Med. 2025, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.H.; Kim, T.; Choi, I.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Won, D.G.; Oh, A.; Lee, Y.; Choi, J.; et al. Diagnostic Yield and Clinical Utility of Whole Exome Sequencing Using an Automated Variant Prioritization System, EVIDENCE. Clin. Genet. 2020, 98, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannick, J.; Mercader, J.M.; Fuchsberger, C.; Udler, M.S.; Mahajan, A.; Wessel, J.; Teslovich, T.M.; Caulkins, L.; Koesterer, R.; Barajas-Olmos, F.; et al. Exome sequencing of 20,791 cases of type 2 diabetes and 24,440 controls. Nature 2019, 570, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).