In Silico Lead Identification of Staphylococcus aureus LtaS Inhibitors: A High-Throughput Computational Pipeline Towards Prototype Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

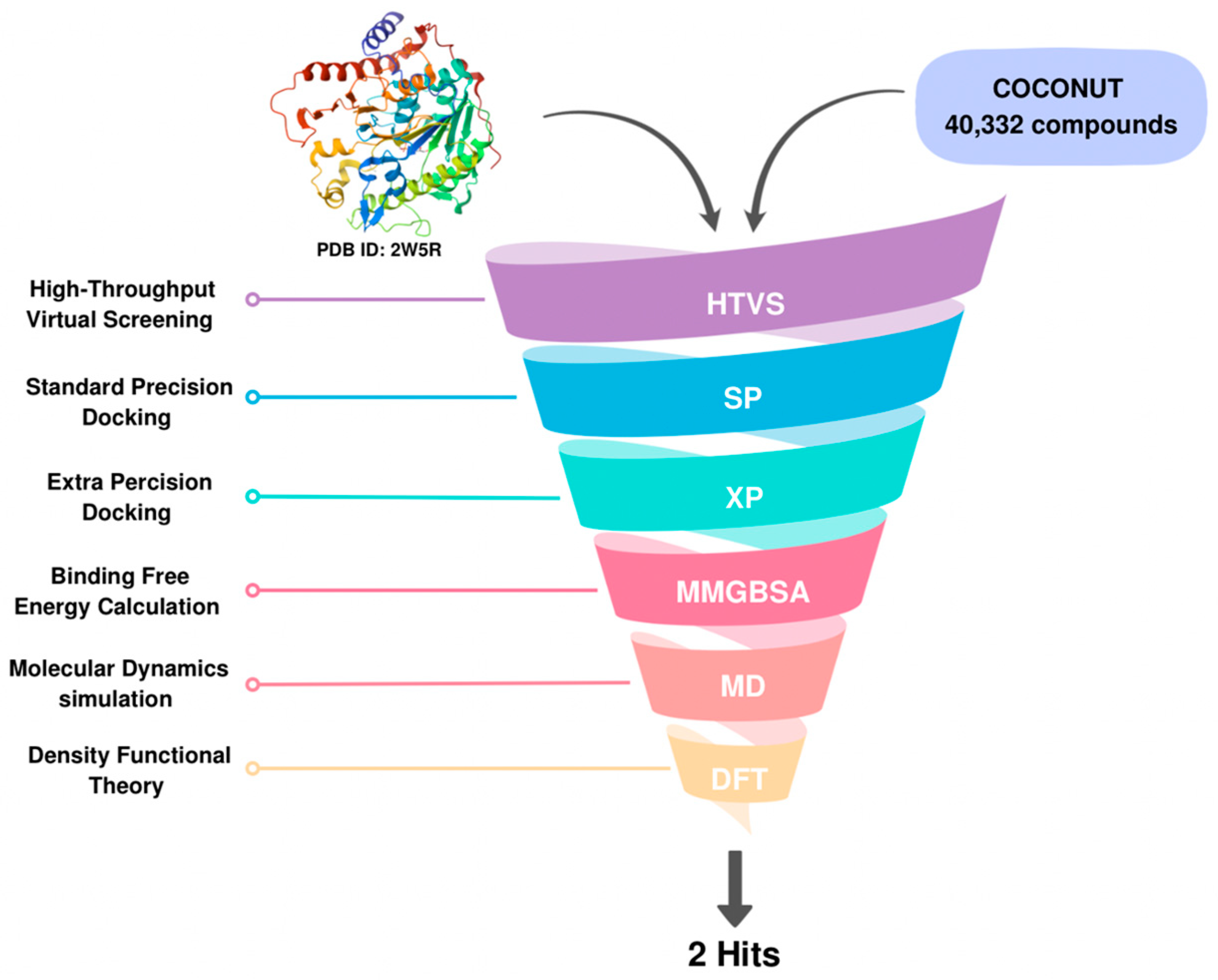

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Docking

2.2. MM-GBSA Calculations

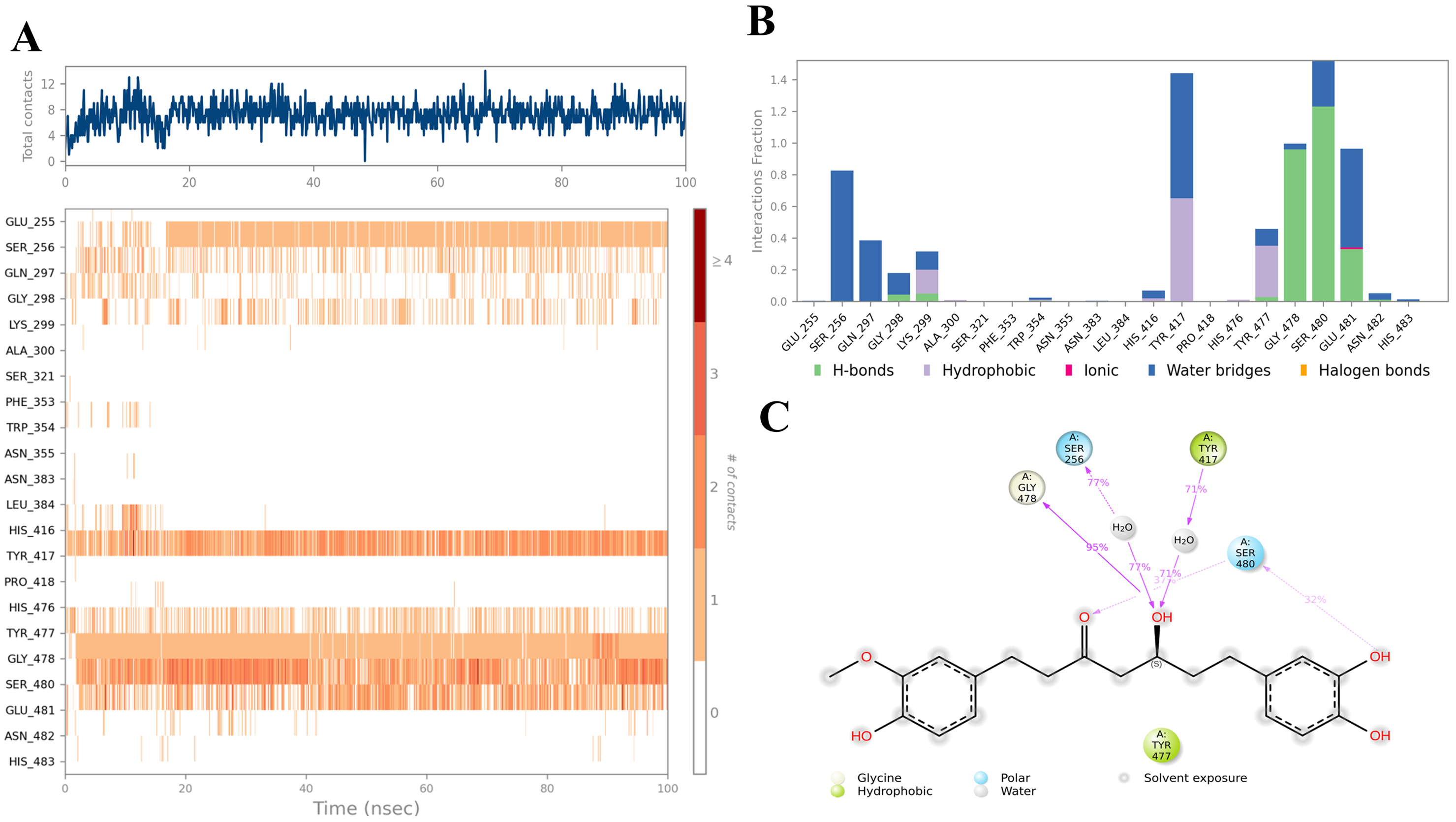

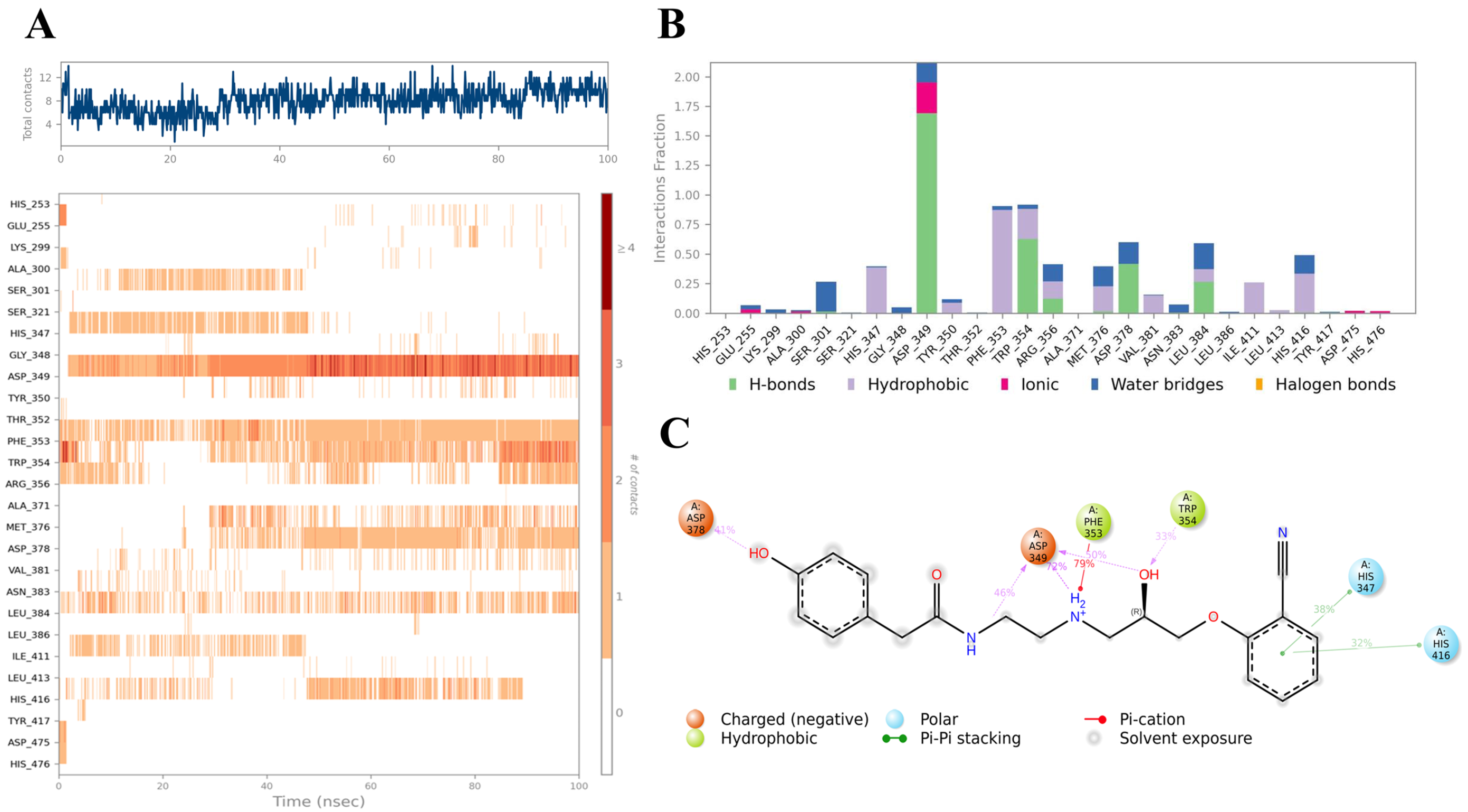

2.3. Ligand–Protein Interactions Analysis

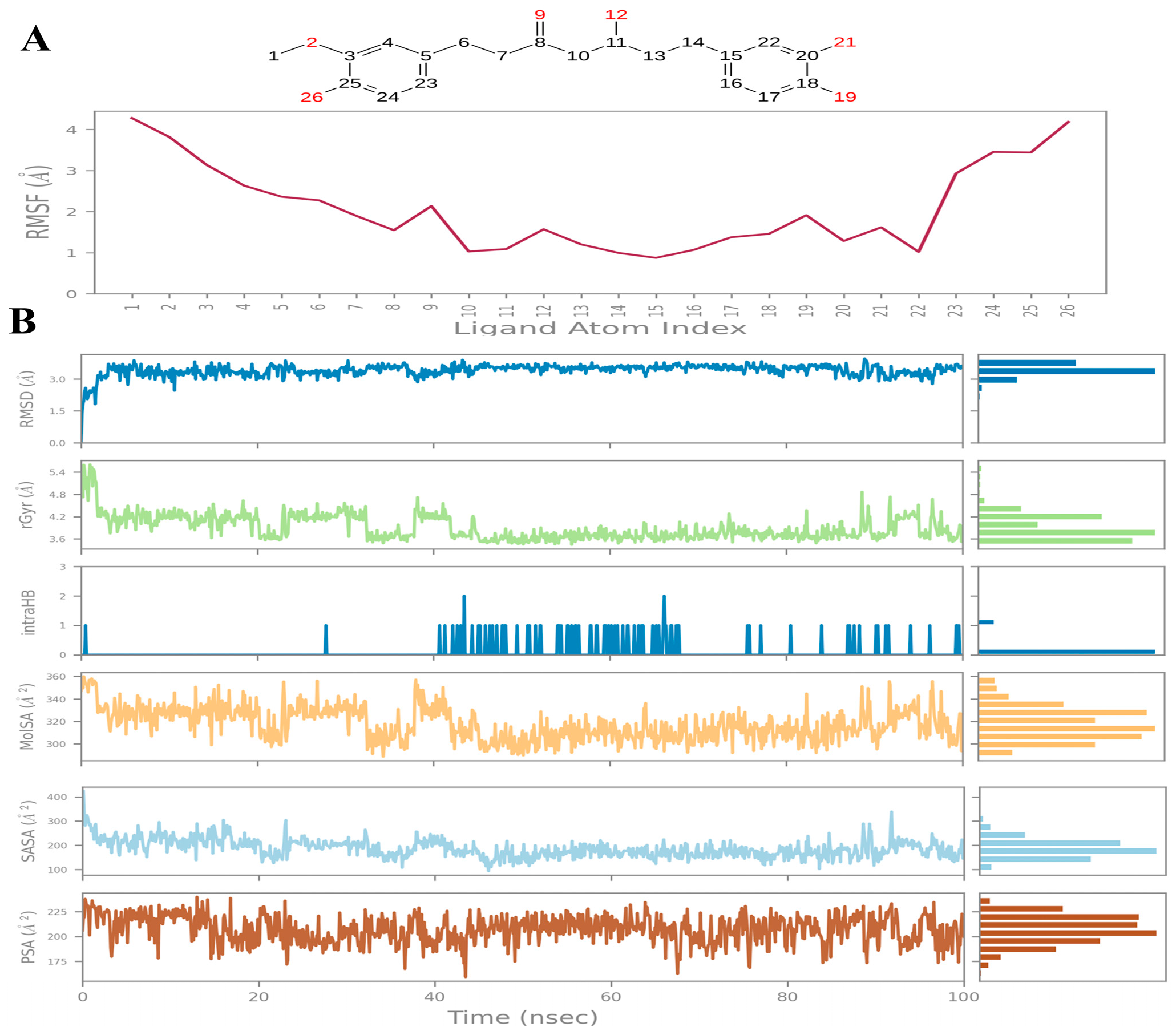

2.4. Molecular Dynamics

2.5. DFT Analysis

2.6. ADMET Profiling

2.7. Physicochemical and Drug-Likeness Profiling

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Software

3.2. Ligands Retrieval and Preparation

3.3. Protein Retrieval and Preparation

3.4. Grid Generation and Molecular Docking

3.5. Binding Free Energy Calculations

3.6. ADMET Profiling

3.7. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

3.8. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology. Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stryjewski, M.E.; Chambers, H.F. Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections Caused by Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, S368–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Das Kumar, A. Integrated Multi Omics, Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking Analysis of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 for the Identification of Potential Therapeutic Targets: An In Silico Approach. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 2735–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.Z.; Daum, R.S. Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and Clinical Consequences of an Emerging Epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 616–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H.W.; Corey, G.R. Epidemiology of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, S344–S349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, Research, and Development of New Antibiotics: The WHO Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, B.P.; Davies, J.K.; Johnson, P.D.R.; Stinear, T.P.; Grayson, M.L. Reduced Vancomycin Susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, Including Vancomycin-Intermediate and Heterogeneous Vancomycin-Intermediate Strains: Resistance Mechanisms, Laboratory Detection, and Clinical Implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 99–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, S.; Siddiqui, T.J.; Bidaisee, S. Reduced Susceptibility and Resistance to Vancomycin of Staphylococcus aureus: A Review of Global Incidence Patterns and Related Genetic Mechanisms. Cureus 2021, 13, e18925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Arias, C.A. Mechanism of Action and Resistance to Daptomycin in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococci. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, K.S.; Vester, B. Resistance to Linezolid Caused by Modifications at Its Binding Site on the Ribosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.A.; Marshall, B.; Alghamadi, A.; Joseph, E.A.; Duggan, S.; Vittorio, S.; De Luca, L.; Serpi, M.; Laabei, M. Improved Antibacterial Activity of 1,3,4-Oxadiazole-Based Compounds That Restrict Staphylococcus aureus Growth Independent of LtaS Function. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 2141–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, M.G.; Gründling, A. Lipoteichoic Acid Synthesis and Function in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 68, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenmaier, C.; Peschel, A. Teichoic Acids and Related Cell-Wall Glycopolymers in Gram-Positive Physiology and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, F.C.; Baddiley, J. A Continuum of Anionic Charge: Structures and Functions of D-Alanyl-Teichoic Acids in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 686–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, G.; Kohler, T.; Peschel, A. The Wall Teichoic Acid and Lipoteichoic Acid Polymers of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 300, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, C.R.; Wood, B.M.; Morris, H.G.; Losick, R.; Walker, S. Reconstitution of Staphylococcus aureus Lipoteichoic Acid Synthase Activity Identifies Congo Red as a Selective Inhibitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezen, X.C.; Chandran, A.; Eapen, R.S.; Waters, E.; Bricio-moreno, L.; Tosi, T.; Dolan, S.; Millership, C.; Kadioglu, A.; Gründling, A.; et al. Structure-Based Discovery of Lipoteichoic Acid Synthase Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2586–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.G.; Elli, D.; Kim, H.K.; Hendrickx, A.P.A.; Sorg, J.A.; Schneewind, O.; Missiakas, D. Small Molecule Inhibitor of Lipoteichoic Acid Synthesis Is an Antibiotic for Gram-Positive Bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3531–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gill, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Mann, P.; Zuck, P.; Meredith, T.C.; Murgolo, N.; She, X.; Kales, S.; Liang, L.; et al. Discovery of Wall Teichoic Acid Inhibitors as Potential Anti-MRSA β-Lactam Combination Agents. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxley, M.A.; Wright, S.N.; Lam, A.K.; Friedline, A.W.; Strange, S.J.; Xiao, M.T.; Moen, E.L.; Rice, C. V Targeting Wall Teichoic Acid In Situ with Branched Polyethylenimine Potentiates β-Lactam Efficacy against MRSA. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchil, R.R.; Kohli, G.S.; Katekhaye, V.M.; Swami, O.C. Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, ME01–ME04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The Re-Emergence of Natural Products for Drug Discovery in the Genomics Era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionta, E.; Spyrou, G.; Vassilatis, D.K.; Cournia, Z. Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Drug Discovery: Principles, Applications and Recent Advances. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1923–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Kličič, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein-Ligand Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, R.T. Structure-Based Drug Design: Docking and Scoring. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2007, 8, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, D.; Caballero, J. Is It Reliable to Take the Molecular Docking Top Scoring Position as the Best Solution without Considering Available Structural Data? Molecules 2018, 23, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.G.; Dos Santos, R.N.; Oliva, G.; Andricopulo, A.D. Molecular Docking and Structure-Based Drug Design Strategies. Molecules 2015, 20, 13384–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahinko, M.; Niinivehmas, S.; Jokinen, E.; Pentikäinen, O.T. Suitability of MMGBSA for the selection of correct ligand binding modes from docking results. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2019, 93, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wörmann, M.E.; Zhang, X.; Schneewind, O.; Gründling, A.; Freemont, P.S. Structure-Based Mechanism of Lipoteichoic Acid Synthesis by Staphylococcus aureus LtaS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Rajan, K.; Kanakam, S.R.S.; Sharma, N.; Weißenborn, V.; Schaub, J.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT 2.0: A comprehensive overhaul and curation of the collection of open natural products database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D634–D643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.S.; Dalal, P.; Tebben, A.J.; Cheney, D.L.; Shelley, J.C. Macrocycle Conformational Sampling with MacroModel. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 2680–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastry, G.M.; Adzhigirey, M.; Day, T.; Annabhimoju, R.; Sherman, W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.Z.H.; Hou, T. End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and applications in drug design. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9478–9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, R.A.; Predescu, C.; Ierardi, D.J.; Mackenzie, K.M.; Eastwood, M.P.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E. Accurate and efficient integration for molecular dynamics simulations at constant temperature and pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 164106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Berkelbach, T.C.; Blunt, N.S.; Booth, G.H.; Guo, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; McClain, J.D.; Sayfutyarova, E.R.; Sharma, S.; et al. PySCF: The Python-based simulations of chemistry framework. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.; Kaya, S.; Kaya, C.; Tüzün, B. Density Functional Theory (DFT) modeling and Monte Carlo simulation assessment of inhibition performance of some carbohydrazide Schiff bases for steel corrosion. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2016, 80, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Performance of B3LYP Density Functional Methods for a Large Set of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Tripathi, V.; Dwivedi, V.D.; Chouhan, G. Mechanistic inhibition of FtsZ-driven bacterial cytokinesis by natural products: An integrated machine learning and advanced drug discovery approach. Mol. Divers. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | COCONUT ID | Chemical Structure | Docking Score in kcal/mol | ΔG_bind in kcal/mol | Key Amino Acid Residues in LtaS | Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

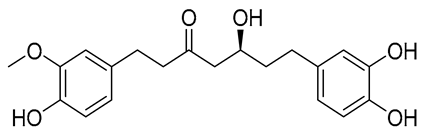

| A | CNP0231191.2 |  | −6.771 | −46.02 | HIP416, THR300, GLU255, TRP354, ASP475, ASP349, ARG356, LEU384 and HIP476 | THR352, TYR417 H2O2002, and 2435 |

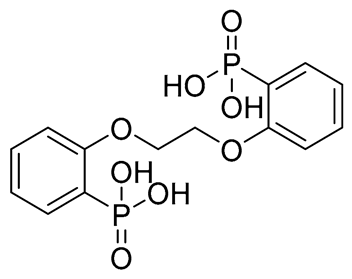

| B | CNP0521000.0 |  | −6.414 | −32.78 | THR352, TRP354, HIP416, and H2O2002 | |

| C | CNP0471911.0 |  | −11.285 | −26.32 | GLU255, PHE353, TRP354, HIP416, and H2O2142 | |

| D | CNP0470462.0 |  | −11.27 | −20.3 | GLU255, TRP354, HIP416, and H2O2142 | |

| E | CNP0598632.1 |  | −11.169 | −5.72 | GLU255, ALA300, ARG356, HIP416, and H2O2142 | |

| F | CNP0471223.0 |  | −11.012 | −22.56 | GLU255, TRP354, ASN383, HIP416, TYR417, and H2O2142 | |

| G | CNP0470600.0 |  | −10.912 | −19.56 | GLU255, TRP354, HIP416, and H2O2142 | |

| H | CNP0477679.0 |  | −10.895 | −3.37 | GLU255, TRP354, HIP416, and H2O2142 | |

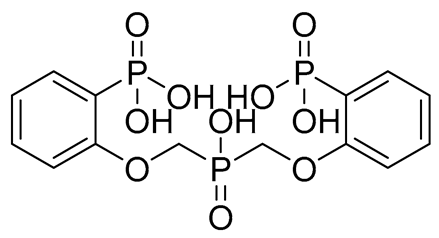

| Reference |  | −10.062 | −30.15 | ALA300, TRP354, ARG356, HIS347 MN1643, H2O2440, and 2441 |

| S. No. | Compounds | Total Energy (Hartree) | HOMO Energy (Hartree) | LUMO Energy (Hartree) | HOMO-LUMO Gap | Electronegativity (χ) (Hartree) | Hardness (η) (Hartree) | Softness (S) | Electrophilicity Index (ω) (Hartree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | A | −1227.931989 | −0.204084 | −0.027620 | 4.802 eV | 0.115852 | 0.176465 | 5.666852 | 0.038029 |

| 2. | B | −1241.137531 | −0.224214 | −0.052793 | 4.665 eV | 0.138503 | 0.171421 | 5.833580 | 0.055953 |

| 3. | Reference | −911.096591 | −0.288515 | −0.266392 | 0.602 eV | 0.277454 | 0.022123 | 45.200991 | 1.739797 |

| ADMET Parameters | Compound A | Compound B | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | |||

| Water solubility (log mol/L) | −3.711 | −2.798 | −0.02 |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10−6 cm/s) | 0.156 | 0.069 | −0.193 |

| Intestinal absorption (human) (% Absorbed) | 76.64 | 63.667 | 57.786 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Distribution | |||

| BBB permeability (log BB) | −1.033 | −0.79 | −0.896 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | −3.329 | −3.608 | −3.67 |

| Metabolism | |||

| CYP2D6 substrate (Yes/No) | No | Yes | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No |

| Excretion | |||

| Total Clearance (log mL/min/kg) | 0.299 | 1.164 | 0.34 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | No |

| Toxicity | |||

| AMES toxicity (Yes/No) | No | No | No |

| Max. tolerated dose (human) (log mg/kg/day) | 0.158 | −0.273 | 1.439 |

| hERG I inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No |

| Hepatotoxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Molecule Properties | Compound A | Compound B | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties | |||

| Molecular Weight | 360.40 g/mol | 370.42 g/mol | 170.06 g/mol |

| LogP | 2.45 | 0.53 | −1.55 |

| #Acceptors | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| #Donors | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| #Heavy atoms | 26 | 27 | 10 |

| #Arom. heavy atoms | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| Fraction Csp3 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 1 |

| #Rotatable bonds | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| Molar refractivity | 98.66 | 101.22 | 27.87 |

| TPSA (Å2) | 107.22 | 119.19 | 122.69 |

| Drug-likeness | |||

| Lipinski alert | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation | Yes; 0 violation |

| Ghose | Yes | Yes | No; 3 violations: WLOGP < −0.4, MR < 40, #atoms < 20 |

| Veber | Yes | No; 0 violation: Rotors > 10 | Yes |

| Egan | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Muegge | Yes | Yes | No; 3 violations: MW < 200, XLOGP3 < −2, #C < 5 |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| Medicinal chemistry | |||

| PAINS | 1 alert: catechol_A | 0 alert | 0 alert |

| Brenk | 1 alert: catechol | 0 alert | 1 alert: phosphor |

| Synthetic accessibility | 2.94 | 3.23 | 3.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Khzem, A.H.; Shoaib, T.H.; Mukhtar, R.M.; Alturki, M.S.; Gomaa, M.S.; Hussein, D.; Mostafa, A.; Alrumaihi, L.A.; Alansari, F.A.; Laabei, M. In Silico Lead Identification of Staphylococcus aureus LtaS Inhibitors: A High-Throughput Computational Pipeline Towards Prototype Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412038

Al Khzem AH, Shoaib TH, Mukhtar RM, Alturki MS, Gomaa MS, Hussein D, Mostafa A, Alrumaihi LA, Alansari FA, Laabei M. In Silico Lead Identification of Staphylococcus aureus LtaS Inhibitors: A High-Throughput Computational Pipeline Towards Prototype Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412038

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Khzem, Abdulaziz H., Tagyedeen H. Shoaib, Rua M. Mukhtar, Mansour S. Alturki, Mohamed S. Gomaa, Dania Hussein, Ahmed Mostafa, Layla A. Alrumaihi, Fatimah A. Alansari, and Maisem Laabei. 2025. "In Silico Lead Identification of Staphylococcus aureus LtaS Inhibitors: A High-Throughput Computational Pipeline Towards Prototype Development" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412038

APA StyleAl Khzem, A. H., Shoaib, T. H., Mukhtar, R. M., Alturki, M. S., Gomaa, M. S., Hussein, D., Mostafa, A., Alrumaihi, L. A., Alansari, F. A., & Laabei, M. (2025). In Silico Lead Identification of Staphylococcus aureus LtaS Inhibitors: A High-Throughput Computational Pipeline Towards Prototype Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412038