Abstract

There is evidence that mast cells contribute to skeletal response to injury, but it is less clear whether these immune cells directly influence normal bone growth and turnover. Mature mast cells are common in the bone marrow of humans and rats, but have not been convincingly demonstrated to be present in the bone marrow of healthy mice, potentially limiting the mouse as a model for characterizing the full range of mast cell/bone cell interactions. An initial goal of this investigation was to comprehensively screen seven strains of mice for mature mast cells in bone marrow. Finding none, we then investigated three approaches to home these cells to the marrow of mice unable to generate mast cells: (1) administration of soluble kit ligand to membrane kit ligand-deficient KitSl/Sld mice, (2) adoptive transfer of wild-type hematopoietic stem cells to kit receptor-deficient KitW/W−v mice, and (3) adoptive transfer of wild-type mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells generated in vitro and delivered intravenously to KitW/W-v mice. Only the third approach was successful. Using this method, we then evaluated the impact of bone marrow-derived mast cells on bone mass, architecture, turnover, and gene expression. The adoptive transfer of mast cells resulted in alterations in cancellous bone microarchitecture and cell populations in the vertebra, and in differential expression of genes associated with bone metabolism in the tibia. Taken together, our results support the concept that bone marrow mast cells influence bone metabolism and suggest that homing mast cells to the bone marrow of mice is a useful model to understand the role of these cells in skeletal health and disease.

1. Introduction

Mast cells originate from the myeloid branch of the immune system and play important roles in innate and adaptive immune responses [1]. The cells are found in mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, but the tissue distribution varies among species [2,3]. Mast cell progenitors originate in bone marrow. The immature cells leave the marrow, circulate in the blood, home in many tissues, and, under the influence of the local niche, complete their differentiation to form tissue-specific mature mast cells. Mature mast cells are not found in circulation, suggesting that following maturity, they remain within tissues [4].

The physiological and pathophysiological roles of mast cells have been extensively studied in mast cell-deficient mice, including ones with loss-of-function mutations in the kit receptor or kit ligand [5]. Studies have also been carried out using kit signaling-independent genetic models for mast cell deficiency [6]. As initiators of the inflammatory cascade, there is strong evidence that mast cells play a role in the skeletal response to injury [6]. However, there is model-dependent, contradictory evidence as to the role of mast cells in bone growth and turnover [7]. Specifically, Kroner et al. reported that the ablation of mast cells had no impact on normal skeletal growth or turnover, but mast cells influenced fracture repair and were required for ovariectomy-induced bone loss in mice [8]. In contrast, we reported skeletal changes in growing mast cell-deficient mice but found that mast cell deficiency had no effect on the skeletal response to ovariectomy [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Mast cell differentiation and survival require kit receptor-mediated signaling. The kit receptor (CD 117) is a receptor tyrosine kinase present on the surface of hematopoietic stem cells. Although important in early hematopoietic lineage decision, kit receptor-mediated signaling is generally less important in differentiated hematopoietic lineage cells [15]. Mast cells are unusual, but not unique, in that mature cells express the kit receptor [16]. Importantly, mast cell survival, as well as differentiation, is dependent upon the activation of the kit receptor by the kit ligand (stem cell factor). Fibroblast lineage and endothelial cells produce membrane and soluble forms of the kit ligand [17]. Consequently, mast cells that are present in bone marrow have the potential to interact physically (membrane to membrane) with osteoblasts, preosteoblasts, and bone marrow adipocytes expressing the membrane kit ligand. Additionally, mesenchymal lineage cells may interact at a distance with mast cells through the soluble kit ligand and mast cells with bone cells through many effectors (e.g., cytokines, chemokines, growth factors) that mast cells produce and release [18]. Skeletal phenotypes of mast cell-deficient mice resulting from defects in kit signaling are not uniform across mouse models, indicating that additional factors are at play [9,11]. For example, KitW/W-v and KitSl/Sld mice with loss-of-function mutations in the kit receptor and membrane kit ligand, respectively, do not have mature adipocytes in their bone marrow, whereas KitW-sh mice, although mast cell-deficient, accrue bone marrow in adipose tissue. The KitW-sh mouse has an inversion mutation in the transcriptional regulatory elements upstream of the kit receptor transcription start site on chromosome 5 and has fewer developmental abnormalities attributable to defective kit signaling than the KitW/W-v or KitSl/Sld mouse [19].

Kit receptor signaling is important for functions beyond mast cell differentiation, including hematopoiesis, melanocyte survival, and gametogenesis [20]. Loss-of-function mutations resulting in the altered expression of different isoforms of kit ligand or kit receptor differ in their skeletal phenotypes, illustrating the important but complex role of kit signaling in bone metabolism. Our research interests include establishing the role of kit signaling and mast cells in bone tissue. To advance knowledge in how mast cells interact with bone cells, it would be useful to design models in which mature mast cells could be introduced into bone and/or extraskeletal tissues.

Mast cells are normally present within cancellous and endocortical bone compartments in humans and some rodents (e.g., rats). However, as noted, while mast cell precursors originate in bone marrow, the precise stage of differentiation achieved in mice is unknown. We have not detected metachromatic cell granules that are present in mature mast cells in the bone marrow of several commonly investigated mouse strains [21]. There is strong evidence that mature mast cells normally present in bone marrow in other species can interact with preosteoblasts, mature osteoblasts, preosteoclasts, and mature osteoclasts to alter their differentiation and function [21]. The absence of mature mast cells in bone marrow in mice may contraindicate the use of mice as a model to investigate the direct role of mast cells in cancellous and endocortical bone growth and turnover. Therefore, we reviewed histological sections from archived mouse specimens to verify the absence of mature mast cells in marrow. In addition to representative strains of mice, we investigated whether genetic manipulations and interventions that impact bone metabolism localize mast cells to bone marrow in mice. Not finding any mast cells in the bone marrow in the histological sections from representative bones in over 1000 mice, we evaluated the efficacy of several approaches to introduce mast cells into bone marrow. The goal was to develop a model for future investigation of how mast cells in the bone marrow microenvironment interact with resident cell populations. To this end, this study conducted the following: (1) we administered soluble kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice to induce mast cell differentiation, (2) we adoptively transferred wild-type (WT) hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to lethally irradiated KitW/W-v mice to restore normal kit signaling, and (3) we differentiated WT mast cells from unfractionated bone marrow in vitro and adoptively transferred these cells into KitW/W-v mice. The rationale for the first approach is that the subcutaneous administration of soluble kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice results in the localization of mast cells to cutaneous connective tissue. As such, it is plausible that mast cells would also localize to bone marrow. Similarly, the adoptive transfer of WT HSCs to KitW/W-v mice (approach 2) would be anticipated to lead to an efflux of mast cell precursors from bone marrow to relocate to peripheral connective tissues to complete their differentiation. It is plausible that some of these cells would return to the bone. Finally, adoptively transferred mature mast cells (approach 3) would be anticipated to be quickly cleared from circulation by entry into connective tissues, potentially including bone marrow. Of these three approaches, adoptive transfer of bone marrow-derived mast cells was successful in introducing mast cells into bone marrow. Using this method, we evaluated the impact of mast cells on body composition and on bone architecture, cell populations, and gene expression. We hypothesized that the presence of mast cells in bone marrow would alter bone metabolism.

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of Bone Marrow in Mice for Presence/Absence of Mast Cells

As anticipated, mast cells were easily detected in the bone marrow of toluidine blue-stained histological sections of rat, but not mouse, bone (Figure 1). Specifically, mast cells were not detected in the bone marrow in the seven mouse strains evaluated (B6, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ, DBA, ICR, Swiss Webster, or WBB6F1/J) (Table 1). Analyses assessing the age, sex, and bone/bone compartment as intrinsic variables revealed no bone marrow mast cells in healthy mice. Similarly, mast cells were not detected in bone marrow following ovariectomy, oophorectomy, high-fat feeding, simulated hyperparathyroidism (continuous infusion of parathyroid hormone (PTH)), simulated microgravity (hindlimb unloading), high-dose irradiation, polyethylene particle-induced systemic bone loss, spinal cord injury-induced systemic bone loss, temperature stress, or hormones, drugs, and genetic manipulations that influence bone metabolism. These null results contrast with the plentiful numbers of mature mast cells routinely observed in the bone marrow of male and female rats [21], and in skin, adipose tissue, and spleen in mice.

Figure 1.

Representative toluidine blue-stained histological section viewed at 64× (scale bar = 50 μm) of proximal tibia metaphysis in Sprague-Dawley rat and distal femur metaphysis in C57BL/6J (B6) mouse showing presence of mature mast cells (exhibiting metachromatic staining) in the rat (positive control) and absence of mature mast cells in the mouse. White arrows point to mast cells. Over 1000 individual histological bone specimens were reviewed for presence of mast cells in mice. Rat histological section is representative of 6-month-old male rats (n = 8) with marrow mast cell density of 27 ± 6/mm2 (mean ± SE).

Table 1.

Mast cells were not detected in bone marrow of mice across strain, gene alteration, sex, intervention, age, or bone evaluated.

2.2. Homing Mast Cells to Bone Marrow in Mast Cell-Deficient Mice

Approach 1: Administration of kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice. Mast cells were detected in the skin following the administration of soluble kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice [11]. However, these cells were not detected in the bone marrow (femur) in these mice.

Approach 2: Adoptive transfer of WT HSCs into KitW/W-v mice. Adoptive transfer of WT HSCs into KitW/W-v mice following lethal irradiation restored normal kit signaling in the bone marrow [12], but mast cells were not detected in the marrow (femur, lumbar vertebra) in these mice.

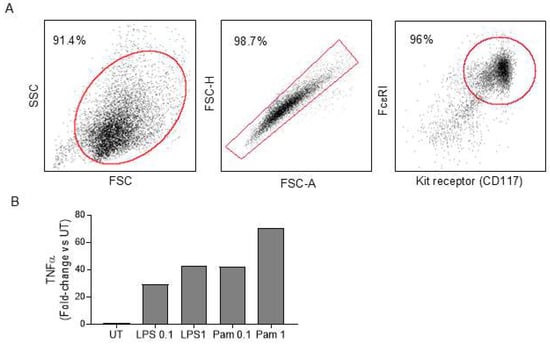

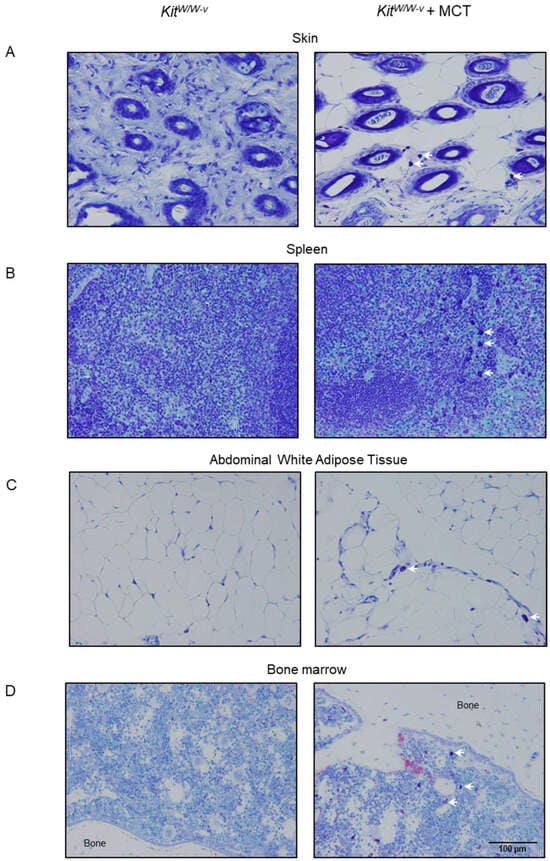

Approach 3: Adoptive transfer of WT mast cells into KitW/W-v mice. Bone marrow cells from WT mice cultured with IL-3 and kit ligand were used to differentiate and expand mast cells count in vitro. Ninety-six percent of these cells co-expressed FcεR1 and CD117, confirming differentiation to the mast cell lineage following 4 weeks in culture (Figure 2A). Incubation of cultured mast cells with toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) agonist (Pam3CSK1) and TLR4 agonist (LPS) resulted in a dose-dependent increase in TNFα expression, a key inflammatory marker for mast cell activation, indicating functionality in these cells (Figure 2B). Mast cells were common in skin, spleen, white adipose tissue (WAT), and lumbar vertebra following the adoptive transfer of the cultured cells into KitW/W-v mice, but were not detected in any of these tissues in untreated KitW/W-v mice (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Generation of mast cells. WT bone marrow cells were differentiated ex vivo into mast cells. (A) At the end of the 4-week culture, the purity of mast cells was verified by flow cytometry, as determined by the co-expression of kit receptor and FcεR1 on the majority of differentiated cells. The red box/oval denotes the gating strategy of each flow cytometry plot. The percentages shown represent cells within the gated region. A minimum of 10,000 events were acquired and analyzed. (B) The ability of cultured mast cells to activate was determined by induced TNFα expression upon TLR2 agonist (Pam3CSK1) and TLR4 agonist (LPS) treatment at 0.1 and 1 µg/mL. TNFalpha gene expression was determined by real-time PCR and compared relative to untreated (UT) control (n = 2/treatment). FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter; FSC-A, FSC area; FSC-H, FSC height.

Figure 3.

Representative toluidine blue-stained histological sections at 32× (scale bar = 100 μm) of (A) skin, (B) spleen, (C) abdominal white adipose tissue, and (D) bone marrow 9 weeks following adoptive transfer of mast cells into KitW/W-v mice. White arrows point to mast cells. Vehicle-treated mast cell-deficient KitW/W-v mice were used as controls (left column). Quantification of bone marrow mast cells from these mice is presented in Figure 4I.

Body composition and markers of bone turnover: A adoptive transfer of mast cells had no significant effect on body mass, lean mass, fat mass, percent fat, bone area, bone mineral content, bone mineral density, abdominal WAT weight, uterine weight, blood glucose, or global serum markers of bone turnover, carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX), and osteocalcin (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of mast cell transfer in KitW/W-v mice on body composition, blood glucose levels, and serum markers of bone turnover.

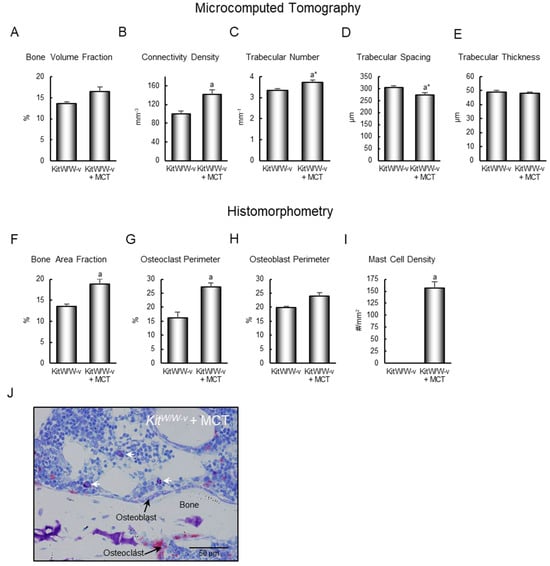

Bone architecture (µCT): Adoptive transfer of mast cells into KitW/W-v mice altered cancellous bone architecture in the lumbar vertebra (Figure 4). Specifically, the adoptive transfer of mast cells resulted in higher connectivity density (Figure 4B), and a tendency (p = 0.078) for higher trabecular number (Figure 4C) and lower trabecular spacing (Figure 4D). Significant differences in cancellous bone volume fraction (Figure 4A, p = 0.106) or trabecular thickness (Figure 4E) were not detected with treatment.

Figure 4.

Effect of mast cell transfer (MCT) in KitW/W-v mice on (A) cancellous bone volume fraction, (B) connectivity density, (C) trabecular number, (D) trabecular spacing, and (E) trabecular thickness, and on (F) cancellous bone area fraction, (G) osteoclast-lined bone perimeter, (H) osteoblast-lined bone perimeter, and (I) mast cell density in lumbar vertebrae 9 weeks following adoptive transfer of mast cells into KitW/W-v mice. Cells measured (64×; scale bar = 50 μm) are shown in panel (J), and include osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and mast cells. White arrows point to mast cells. Data are mean ± SE, n = 7–8/group. a Different from control KitW/W-v, p ≤ 0.05. a* Different form control KitW/W-v, p ≤ 0.1.

Bone histomorphometry: Adoptive transfer of mast cells resulted in higher bone area fraction (Figure 4F) and osteoclast-lined bone perimeter (Figure 4G). Differences in osteoblast-lined bone perimeter (Figure 4H) were not detected with treatment. Mast cell density increased from 0 to 157 ± 13/mm2 (Figure 4I). The cells being assayed are shown in Figure 4J. Bone marrow adipocytes were not observed in the lumbar vertebrae of control KitW/W-v mice or KitW/W-v mice following adoptive transfer of the WT mast cells.

Differential gene expression: We performed 2 PCR gene arrays (osteoporosis and osteogenesis), each evaluating 84 genes. Twenty genes overlapped between the two arrays. Thus, we assayed 144 individual genes related to bone metabolism. Adoptive transfer of mast cells to KitW/W-v mice resulted in the differential expression of 40 genes (Table 3). For the 20 genes that overlapped between the two arrays, there were no discrepancies in gene response to adoptive transfer of mast cells. Mast cell-mediated differential gene expression included genes for enzymes (Alp, Phex), cytokines (Tgfb3), receptors (Bmpr2, Casr, Cnr2, Esr1, Essra, Fgfr1, Itga2, Itgb3, Lrp5, Lrp6, Mthfr, Tgfbr2, Tgfbr3, Vdr), chloride voltage-gated channels (Clcn7), vitamin D function (Dbp, Smad3), skeletal development and maturation (Serpinh1, Ihh, Nog, Runx2, Smad4, Smad5, Sp7, Ahsg), osteoclast differentiation and function (Spp1, Tnfrsf11a, Tnfrsf1b), structural proteins (Col14a1), immune function (Csf2, Tnfaip3), and angiogenesis (Vegfa, Vegfb). As expected, gene ontology enrichment analysis showed that the 40 significantly differentially expressed genes were involved in the regulation of ossification, skeletal system development, bone resorption, and osteoblast differentiation (Supplemental Figure S1).

Table 3.

Differential expression of genes related to bone turnover in tibia 9 weeks following mast cell transfer (MCT) in KitW/W-v versus control KitW/W-v mice.

3. Discussion

Here we verified that mature mast cells with toluidine blue-stained granules are not normally present in the bone marrow of representative bones of commonly studied inbred and outbred strains of mice. We also showed that neither aging nor interventions that alter bone growth and/or turnover resulted in homing of mature mast cells into bone marrow in mice. Specifically, we evaluated the following interventions that alter bone metabolism: (1) reduction in sex hormone levels (ovariectomy and oophorectomy), (2) hyperparathyroidism, (3) manipulation of diet (e.g., high fat diet), (4) manipulation of skeletal loading (e.g., hindlimb unloading), (5) tissue injury (e.g., high dose radiation, polyethylene particle-induced inflammation, spinal cord injury), (6) temperature stress, (7) hormones (e.g., growth hormone, parathyroid hormone, sex hormones, leptin), (8) drugs (e.g., propranolol, rapamycin), or (9) genetic interventions (e.g., factor 8 KO, TIEG KO, TTP KO, AR TG). As anticipated, mast cells were not detected in the skin, WAT, spleen, or bone marrow of KitW/W-v mice. Following subcutaneous administration of soluble kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice, mast cells were detected in the skin, but they failed to home to bone marrow. Adoptive transfer of HSCs from WT mice into KitW/W-v mice restored kit expression levels in bone marrow to normal, but mast cells were not detected in the marrow. In contrast, mast cells differentiated from bone marrow of WT mice in vitro and adoptively transferred into KitW/W-v mice homed to the skin, WAT, spleen, and bone marrow. The presence of mast cells in the bone marrow in these mice was associated with increased cancellous bone area fraction and osteoclast-lined bone perimeter in the lumbar vertebra and altered gene expression in the tibia. The changes in gene expression are consistent with an overall reduction in bone turnover and decreased osteoclast function, as exemplified by lower Clen7 expression [30].

There is controversy as to whether mast cells, which are commonly found in the intestine and WAT, play a role in energy homeostasis [31,32]. In the present study, adoptive transfer of mature mast cells to mast cell-deficient KitW/W-v mice did not influence important measures of body composition, including total weight, lean weight, fat weight, WAT weight, or blood glucose levels. In contrast to our study, which was performed in mice fed a normal diet, studies implicating a role for mast cells in energy homeostasis have been performed in mice fed high-fat diets [33].

The present study was performed on KitW/W-v mice. As indicated, these mice have decreased levels of cell-surface Kit receptor. The most consistent skeletal phenotype of KitW/W-v mice is the absence of mature bone marrow adipocytes in their long bones and lumbar vertebrae [34]. KitW-sh mice are mast cell-deficient but have bone marrow adipocytes [11], and in the present study, adoptive transfer of mast cells into KitW/W-v mice resulted in homing of mast cells to bone marrow but did not result in an influx of marrow fat. These observations constitute strong evidence that the absence of bone marrow adipocytes in KitW/W-v and KitSl/Sld mice is due to disturbed kit signaling and not to the absence of mast cells. Compared to WT mice, KitW/W-v mice exhibit modest differences in bone architecture and turnover [13]. Adoptive transfer of WT HSCs following lethal irradiation into KitW/W-v mice restored kit signaling to hematopoietic lineage cells but did not result in homing of mast cells to bone marrow and had minimal effect on bone architecture (femur and lumbar vertebra) [13]. Furthermore, following adoptive transfer of HSCs, there were minimal differences in the expression of genes related to hematopoiesis or bone turnover in the femur between WT and KitW/W-v mice [13]. Taken together, these findings strongly support the conclusion that the changes in bone architecture, turnover, and gene expression observed in the present study are due to the introduction of mast cells into the bone marrow.

Systemic mastocytosis can present in a variety of tissues, including skin and bone marrow. Its presence in bone marrow is a rare condition in which mast cells present as compact multifocal aggregates. Gain-of-function mutations of the gene coding for the kit receptor, leading to constitutive signaling through the receptor, are found in >90% of patients with systemic mastocytosis [35]. Osteoporosis is often associated with systemic mastocytosis but not cutaneous mastocytosis [36]. Histologically, bone marrow involvement is typically associated with increased bone turnover, but turnover balance varies [37]. Advanced disease may be associated with osteosclerosis [38]. Systemic mastocytosis with bone loss has a proinflammatory cytokine profile in plasma, whereas mastocytosis with diffuse osteosclerosis shows increased serum/plasma levels of biomarkers related to bone formation and turnover, as well as an immunosuppressive cytokine secretion profile [39]. These findings strongly suggest that mast cell activation in bone marrow and at sites peripheral to bone can have markedly different actions on the skeleton. Additional studies will be required to assess the skeletal impact of normal mast cell function in bone marrow.

In contrast to systemic mastocytosis with a bone marrow component, adoptive transfer of mast cells in the current study resulted in a diffuse distribution of mast cells within the bone marrow. At the gene level, the presence of mast cells was associated with the differential expression of genes related to enzymes, cytokines, receptors, chloride voltage-gated channels, vitamin D function, skeletal development and maturation, osteoclast differentiation and function, immune function, and angiogenesis. This finding suggests that mast cells influence multiple signaling pathways that regulate bone metabolism. At the cellular level, adoptively transferred mast cells homing to bone marrow, while dispersed, were located in the vicinity of bone lining cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, a distribution similar to that observed in normal rats and humans [21]. Mast cell number increases in bone marrow in humans during inflammation, parasitism, uremia, aplastic anemia, select hematologic diseases, and osteoporosis [40,41,42,43,44]. Additional research will be required to establish the role of mast cells in the skeletal response to these pathologies.

Our adoptive transfer of mast cells was limited to females, but we have shown that the skeletal alterations of mast cell-deficient KitW/W-v mice in reference to WT mice are similar across sex. As mentioned, mutations in the kit ligand and kit receptor that result in mast cell deficiency have collateral actions that could influence bone metabolism. For example, KitW/W-v mice are hypogonadal due to defective gametogenesis [45]. However, we have shown that a deficiency in the kit receptor has minimal effects on the skeletal response to sex hormone deficiency [34].

In the present study, adoptive transfer of mast cells was performed in young growing mice, and mast cells were detected within the skeleton, evaluated 9 weeks later. This finding demonstrates that the stability of mast cells in bone is maintained over time following adoptive transfer. Furthermore, mast cell density in the bone marrow of mice following adoptive transfer was similar to that observed in rats [21]. This suggests that mast cell density within bone marrow following adoptive transfer is physiologically relevant. Additional studies are required to determine the precise time course for the observed changes in cancellous bone balance.

While there are many similarities in bone physiology across vertebrate species, there are also notable differences, some of which may be related to the presence or absence of mature mast cells in bone marrow. For example, parathyroid bone disease in humans is associated with an increase in mast cell density in bone marrow [21]. In rats, simulated hyperparathyroidism recapitulates human parathyroid disease by inducing severe peritrabecular bone marrow fibrosis. The migration of mast cells to bone surfaces, followed by cell degranulation, precedes fibrosis [46]. These responses are inhibited by interventions that interfere with mast cell signaling [21,46]. In contrast to rats, mice are resistant to parathyroid hormone-induced bone marrow fibrosis [21]. Additional research will be required to establish if the absence of mast cells in mice confers resistance to this disease.

In summary, mature mast cells, although common in bone marrow in humans, are not normally present in the bone marrow of mice. This verification should inspire a reevaluation of mouse studies claiming that mast cells play no role in normal bone physiology. Subcutaneous administration of soluble kit ligand into KitSl/Sld mice results in local differentiation of mast cell progenitors to form mature mast cells in skin only, whereas adoptive transfer of purified HSCs into KitW/W-v mice restored mast cells to skin, spleen, and adipose tissue. Finally, homing of WT mast cells to the bone marrow of KitW/W-v mice by adoptive transfer altered gene expression, bone cell populations, and bone turnover balance. These findings suggest that homing mature mast cells to select tissue locations (e.g., skin only, normal tissue distribution, normal tissue distribution plus bone marrow) is a viable approach for investigating the role of mast cells in mice, residing remotely in peripheral tissues and locally in bone marrow, on bone metabolism. While there are multiple genetic models for mast cell deficiency, we believe this is the first model for introducing mast cells into the bone marrow of mice.

4. Methods

4.1. Mast Cell Distribution in Skeletal Tissue of Mice

Histological sections of femur, tibia, and/or lumbar vertebra from B6, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ, DBA, ICR, Swiss Webster, and WBB6F1/J mice were evaluated for bone marrow mast cells at 20× magnification (Table 1). Toluidine blue is a basic thiazine dye that exhibits metachromasia and detects cytoplasmic granules present in mature mast cells. The regions of interest for histological sections viewed from over 1000 mice were as follows: femur (distal epiphysis, distal metaphysis, diaphysis), tibia (proximal epiphysis, proximal metaphysis, diaphysis), and vertebra (cancellous compartment and endocortical bone perimeter). The total bone marrow area reviewed per histological section ranged from 2 mm2 (vertebrae) to 5+ mm2 (long bones). Bone marrow cell density in young growing male mice is reported to be ~25,000 cells/mm2 [47]. Absence of mast cells in the bone marrow of B6, DBA, and WBB6F1 mice was previously reported [21] and confirmed in the present study. Tibiae from Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan; Indianapolis, IN) were used as positive controls (Figure 1). Additional positive controls consisted of spleen, skin, and adipose tissue from B6 mice fixed for 24 h in 10% buffered formalin and stored in 70% ethanol prior to embedding in paraffin.

It is possible that mast cells home to bone as an adaptive response to treatment. As such, we reviewed toluidine blue-stained histological sections in mice ranging in age from 1 month to 24 months, ovariectomized at the Jackson Laboratory, oophorectomized [27], treated with PTH to simulate hyperparathyroidism [21], fed normal and high-fat diets, hindlimb unloaded [10], subjected to high dose radiation (up to 10 Gy) [13], or experienced systemic bone loss following the insertion of polyethylene particles over calvaria [48], spinal cord injury [49], gene therapy [50], or other interventions (Table 1).

4.2. Homing Mast Cells to Bone Marrow in Mast Cell-Deficient Mice

The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon State University. All mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and, unless indicated otherwise, were single-housed at 22 °C on a 12 h light–dark cycle and provided food (rodent chow, Teklad 8604, Harlen Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and water ad libitum.

Approach 1: Administration of kit ligand to KitSl/Sld mice. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether soluble kit ligand administered to KitSl/Sld mice to induce mast cell differentiation potentiates the homing of mast cells to bone marrow. The experiment has been described in detail [11]. In brief, 5-week-old male mice were divided into 3 treatment groups (n = 7–9 mice/group): (1) WT (WBB6F1/J), (2) KitSl/Sld administered carrier (buffered saline), or (3) KitSl/Sld administered secreted kit ligand (mouse recombinant stem cell factor, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Kit ligand was delivered in saline by daily subcutaneous injection for 3 weeks (100 µg/kg/day, week 1; 150 µg/kg/day, week 2; 200 µg/kg/day, week 3). Following sacrifice, skin and tibia were removed, fixed for 24 h in 10% buffered formalin, and stored in 70% ethanol for histomorphometric analyses for the presence/absence of mast cells.

Approach 2: Adoptive transfer of WT HSCs into KitW/W-v mice. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the restoration of normal kit expression levels in the bone marrow of KitW/W-v mice results in the presence of mature mast cells in the marrow. The experiment has been described in detail [13]. In brief, 1-month-old female mice were used (n = 5–7 mice/group): (1) WBB6F1/J control, (2) KitW/W-v control, (3) KitW/W-v recipients receiving purified HSCs (HSC → KitW/W-v; 5 Gy), and (4) KitW/W-v recipients receiving purified HSCs (HSC → KitW/W-v, 2 × 5 Gy delivered within a 4 h interval). Following irradiation (60Co irradiator source), the mice in groups 3 and 4 were reconstituted with 750 purified WBB6F1/J HSCs by injection (200 µL) in the lateral tail vein. The mice were maintained for 8 weeks subsequent to HSC engraftment. Following sacrifice, tibiae were removed, fixed for 24 h in 10% buffered formalin, and stored in 70% ethanol for histomorphometric analysis of mast cells.

Approach 3: Adoptive transfer of WT mast cells into KitW/W-v mice. The purpose of this study was to assess whether the introduction of differentiated WT mast cells into KitW/W-v mice results in their homing to the marrow. Four-week-old female KitW/W-v mice were randomly divided into two treatment groups (n = 7–8 mice/group): (1) vehicle (buffered saline) or (2) mast cell transfer (MCT; mast cells → KitW/W-v). Bone marrow cells from the tibia and femur of WT mice were cultured in vitro in RMPI1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 3 ng/mL interleukin-3, and 15 ng/mL stem cell factor for 4 weeks to differentiate and expand mast cell number. The purity of mast cells was verified by flow cytometry, as determined by the co-expression of kit receptor and FcεR1. The activation of cultured mast cells was evaluated after 24 h stimulation with TLR2 agonist (Pam3CSK1) and TLR4 agonist (LPS) at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µg/mL. Mast cell activation was determined by real-time PCR, as determined by induced TNFα expression. For the adoptive transfer experiment, mast cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual media. The number of healthy live mast cells was determined (>98% viable cells that excluded trypan blue staining), and cells were resuspended in PBS for injections. In total, 6 × 106 mast cells were adoptively transferred via lateral tail vein injections in the mast cell transfer group. The mice were maintained for 9 weeks. Body composition was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). For tissue collection, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane anesthesia and terminated by decapitation and exsanguination. Abdominal white adipose tissue (WAT) weight (g), uterine weight (g), and blood glucose (mg/dL) were recorded at necropsy. The fifth lumbar vertebrae were removed and placed in formalin for 24 h fixation, then stored at 4 °C in 70% ethanol prior to sequential analysis by microcomputed tomography (μCT) and histomorphometry. Tibiae were removed, flash frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C until processed for RNA analysis. spleens, WAT, and skin were fixed for 24 h in 10% buffered formalin and subsequently embedded in paraffin for histological evaluation.

4.3. Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry

Lean mass and fat mass were measured in vivo using DXA (Piximus, Lunar Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), and % lean mass and % fat mass were calculated. Additionally, total bone area (cm2), bone mineral content (g), and bone mineral density (g/cm2) were determined. For scanning, the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane anesthesia, positioned on the scanning platform with a nose cone attached to the mouse for isoflurane delivery, and scanned [51].

4.4. Micro-Computed Tomography

μCT was used for nondestructive three-dimensional evaluation of bone volume and architecture. The fifth lumbar vertebrae were scanned using a Scanco μCT40 scanner (Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) at a voxel size of 12 µm × 12 µm × 12 µm (55 kVp X-ray voltage, 145 µA intensity, and 200 ms integration time). The filtering parameters sigma and support were set to 0.8 and 1, respectively. The threshold value for evaluation was determined empirically and set at 245 (gray scale, 0–1000).

The entire cancellous bone compartment was evaluated in the vertebral body (154 ± 2 slices; 1848 ± 12 µm). Direct cancellous bone measurements included bone volume fraction (bone volume/tissue volume; volume of total tissue occupied by cancellous bone, %), connectivity density (number of redundant connections per unit volume, 1/mm3), trabecular number (number of trabecular intercepts per unit length, 1/mm), trabecular spacing (distance between trabeculae, µm), and trabecular thickness (mean thickness of individual trabeculae, µm).

4.5. Histomorphometry

Lumbar vertebrae were dehydrated in graded increases of ethanol and xylene, then embedded undecalcified in methyl methacrylate. Four µm thick sections were cut with a vertical bed microtome (Leica/Jung 2165 Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and affixed to slides with a dried, pre-coated 1% gelatin solution. For cell-based measurements, slides were stained with tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase and counterstained with toluidine blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). All data were collected using the OsteoMeasure System (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA).

The entire cancellous envelope (2.5 ± 0.1 mm2) was evaluated in the vertebral body. Static (cell-based) histological measurements included bone area fraction (bone area/tissue area; %), osteoclast perimeter (osteoclast perimeter/bone perimeter; %), osteoblast perimeter (osteoblast perimeter/bone perimeter; %), adipocyte density (#/mm2), and mast cell density (#/mm2) (Figure 4J). Osteoclast perimeter was determined as a percentage of cancellous bone perimeter covered by multinucleated cells with an acid phosphatase-positive (stained red) cytoplasm. Osteoblast perimeter was determined as a percentage of total bone perimeter lined by plump cuboidal cells located immediately adjacent to a layer of osteoid in direct physical contact with bone. Adipocytes were identified as large circular or oval-shaped cells bordered by a prominent cell membrane, lacking cytoplasmic staining due to alcohol extraction of intracellular lipids during processing. Mast cells were identified by metachromatic staining of histamine-containing granules [52].

The presence or absence of mast cells was also evaluated in paraffin-embedded toluidine blue-stained histological sections of skin, spleen, and WAT.

4.6. Gene Expression

Total RNA from the tibia was isolated from 5 to 6 mice/group and individually analyzed. Tibiae were initially pulverized with a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and subsequently in Trizol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The expression of 84 genes related to bone metabolism was determined for the tibia using the mouse Osteoporosis RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array (PAMM-170Z) (Qiagen; Carlsbad, CA, USA). The expression of 84 genes related to osteogenic differentiation was determined using the Mouse Osteogenesis RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array (Qiagen; Carlsbad, CA, USA). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH. Relative quantification was determined (ΔΔCt method) using RT2 Profiler PCR Array Data Analysis software version 3.5 (Qiagen) after normalization to housekeeping control. Only the significant-averaged fold-change versus control is reported. For TNFα expression in cultured mast cells, RNA was isolated from mast cells after 4 weeks of culture, and cDNA was synthesized as described above. TNFα was detected by real-time PCR, normalized to the expression of Rn18s housekeeping control. The gene list analysis report was generated using Metascape, a web-based portal designed to provide a comprehensive gene list annotation and analysis resource (https://metascape.org/ accessed 11 October 2025).

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Data collection was blinded to the group. Mean responses between the control mice and mice injected with WT bone marrow-derived mast cells were compared using independent two-sample t-tests or distribution-free Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests. Model diagnostics included the use of the Breusch–Pagan test for homogeneity of variance, plots of residuals versus fitted values, normal quantile plots, and the Anderson–Darling test of normality. The Benjamini and Hochberg [53] method for maintaining the false discovery rate at a maximum of 5% was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Data analysis was performed using R version 4.4.2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262411952/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.T.T., U.T.I. and C.P.W.; Formal analysis: A.J.B.; Funding acquisition: R.T.T., U.T.I., C.P.W. and A.J.B.; Investigation: C.P.W., J.A.K., K.A.P., U.T.I. and R.T.T.; Project administration: R.T.T.; Supervision: R.T.T.; Visualization: R.T.T., C.P.W. and U.T.I.; Writing—original draft preparation: R.T.T., C.P.W. and U.T.I.; Writing—review and editing: C.P.W., J.A.K., K.A.P., A.J.B., U.T.I. and R.T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AR060913 and AR066811) and NASA (80NSSC20K0998).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon State University (protocol code 4304, 3 January 2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of our lab manager, the late Dawn Olson, to the completion of this project. We also acknowledge Christiane V. Löhr for the helpful discussion and critical review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CTX | carboxyterminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen |

| DXA | dual energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| FSC | forward scatter |

| HSC | hematopoietic stem cell |

| KO | knockout |

| LV | lumbar vertebra |

| MCT | mast cell transfer |

| μCT | microcomputed tomography |

| PTH | parathyroid hormone |

| SSC | side scatter |

| TLR2 | toll-like receptor 2 |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

| WT | wild type |

References

- Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Dileepan, K.N.; Wood, J.G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccari, G.C.; Pinelli, C.; Santillo, A.; Minucci, S.; Rastogi, R.K. Mast cells in nonmammalian vertebrates: An overview. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 290, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlson, H.C.; Hacking, M.A. Distribution of mast cells in chicken, turkey, pheasant, and quail, and their differentiation from basophils. Avian Dis. 1972, 16, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Tsai, M.; Weissman, I.L.; Galli, S.J. Identification of mast cell progenitors in adult mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11408–11413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, A.D.; Rottapel, R.; Giddens, E.; Brady, C.; Forrester, L.; Bernstein, A. W mutant mice with mild or severe developmental defects contain distinct point mutations in the kinase domain of the c-kit receptor. Genes Dev. 1990, 4, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragipoglu, D.; Bülow, J.; Hauff, K.; Voss, M.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Dudeck, A.; Ignatius, A.; Fischer, V. Mast Cells Drive Systemic Inflammation and Compromised Bone Repair After Trauma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 883707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragipoglu, D.; Dudeck, A.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Voss, M.; Kroner, J.; Ignatius, A.; Fischer, V. The Role of Mast Cells in Bone Metabolism and Bone Disorders. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroner, J.; Kovtun, A.; Kemmler, J.; Messmann, J.J.; Strauss, G.; Seitz, S.; Schinke, T.; Amling, M.; Kotrba, J.; Froebel, J.; et al. Mast Cells Are Critical Regulators of Bone Fracture-Induced Inflammation and Osteoclast Formation and Activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotinun, S.; Evans, G.L.; Turner, R.T.; Oursler, M.J. Deletion of membrane-bound steel factor results in osteopenia in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005, 20, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, J.A.; Wong, C.P.; Branscum, A.J.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Turner, R.T. Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue Deficiency Increases Disuse-Induced Bone Loss in Male Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.T.; Wong, C.P.; Iwaniec, U.T. Effect of reduced c-Kit signaling on bone marrow adiposity. Anat. Rec. 2011, 294, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keune, J.A.; Wong, C.P.; Branscum, A.J.; Menn, S.A.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Turner, R.T. Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue Is Not Required for Reconstitution of the Immune System Following Irradiation in Male Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyhle, R.T., Jr.; Wong, C.P.; Martin, S.A.; McDougall, M.Q.; Olson, D.A.; Branscum, A.J.; Menn, S.A.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Hamby, D.M.; Turner, R.T. Maintenance of Near Normal Bone Mass and Architecture in Lethally Irradiated Female Mice following Adoptive Transfer with as few as 750 Purified Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Radiat. Res. 2019, 191, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotinun, S.; Krishnamra, N. Disruption of c-Kit Signaling in Kit(W-sh/W-sh) Growing Mice Increases Bone Turnover. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.H.; Ji, K.; Alderson, N.; He, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.E.; Li, L.; Feng, G.S. Kit-Shp2-Kit signaling acts to maintain a functional hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell pool. Blood 2011, 117, 5350–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.; Valent, P.; Galli, S.J. KIT as a master regulator of the mast cell lineage. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.G.; Leder, P. The kit ligand: A cell surface molecule altered in steel mutant fibroblasts. Cell 1990, 63, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.T.; Martin, S.A.; Iwaniec, U.T. Metabolic Coupling Between Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue and Hematopoiesis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2018, 16, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimbaldeston, M.A.; Chen, C.C.; Piliponsky, A.M.; Tsai, M.; Tam, S.Y.; Galli, S.J. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissel, H.; Timokhina, I.; Hardy, M.P.; Rothschild, G.; Tajima, Y.; Soares, V.; Angeles, M.; Whitlow, S.R.; Manova, K.; Besmer, P. Point mutation in kit receptor tyrosine kinase reveals essential roles for kit signaling in spermatogenesis and oogenesis without affecting other kit responses. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.T.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Marley, K.; Sibonga, J.D. The role of mast cells in parathyroid bone disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Sarkar, R.; Naas, T.; Lawler, A.M.; Pain, J.; Shumaker, S.; Bedian, V.; Kazazian, H.H. Further characteriza-tion of factor VIII-deficient mice created by gene targeting: RNA and protein studies. Blood 1996, 88, 3446–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.C.; Tsui, Y.C.; Feng, X.; Greaves, D.R.; Wei, L.N. NF-κB-mediated degradation of the coactivator RIP140 regulates inflammatory responses and contributes to endotoxin tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensamoun, S.F.; Hawse, J.R.; Subramaniam, M.; Ilharreborde, B.; Bassillais, A.; Benhamou, C.L.; Fraser, D.G.; Oursler, M.J.; Amadio, P.C.; An, K.N.; et al. TGFbeta inducible early gene-1 knockout mice display defects in bone strength and microarchi-tecture. Bone 2006, 39, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasu, V.T.; Ott, S.; Hobson, B.; Rashidi, V.; Oommen, S.; Cross, C.E.; Gohil, K. Sarcolipin and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase 1 mRNAs are over-expressed in skeletal muscles of alpha-tocopherol deficient mice. Free. Radic. Res. 2009, 43, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, S.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Canalis, E.; Sun, H.; Glatt, V.; Gundberg, C.; Cohen, P.; Hwang, D.; Boisclair, Y.; Leroith, D.; et al. The ternary IGF complex influences postnatal bone acquisition and the skeletal response to intermittent parathyroid hormone. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 189, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiren, K.M.; Semirale, A.A.; Zhang, X.W.; Woo, A.; Tommasini, S.M.; Price, C.; Schaffler, M.B.; Jepsen, K.J. Targeting of androgen receptor in bone reveals a lack of androgen anabolic action and inhibition of osteogenesis: A model for compartment-specific androgen action in the skeleton. Bone 2008, 43, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydon, J.P.; DeMayo, F.J.; Conneely, O.M.; O’Malley, B.W. Reproductive phenotpes of the progesterone receptor null mutant mouse. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996, 56, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.A.; Riordan, R.T.; Wang, R.; Yu, Z.; Aguirre-Burk, A.M.; Wong, C.P.; Olson, D.A.; Branscum, A.J.; Turner, R.T.; Iwaniec, U.T.; et al. Rapamycin impairs bone accrual in young adult mice independent of Nrf2. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 154, 111516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobacchi, C.; Schulz, A.; Coxon, F.P.; Villa, A.; Helfrich, M.H. Osteopetrosis: Genetics, treatment and new insights into osteoclast function. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, R.P.; Fudge, D.H.; Brown, J.M. Cellular Energetics of Mast Cell Development and Activation. Cells 2021, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shi, G.P. Mast cell stabilization: Novel medication for obesity and diabetes. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elieh Ali Komi, D.; Shafaghat, F.; Christian, M. Crosstalk Between Mast Cells and Adipocytes in Physiologic and Pathologic Conditions. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaniec, U.T.; Turner, R.T. Failure to generate bone marrow adipocytes does not protect mice from ovariectomy-induced osteopenia. Bone 2013, 53, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent, P.; Akin, C.; Hartmann, K.; Nilsson, G.; Reiter, A.; Hermine, O.; Sotlar, K.; Sperr, W.R.; Escribano, L.; George, T.I.; et al. Advances in the Classification and Treatment of Mastocytosis: Current Status and Outlook toward the Future. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degboé, Y.; Severino-Freire, M.; Couture, G.; Apoil, P.A.; Gaudenzio, N.; Hermine, O.; Ruyssen-Witrand, A.; Paul, C.; Laroche, M.; Constantin, A.; et al. The Prevalence Of Osteoporosis Is Low in Adult Cutaneous Mastocytosis Patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvard, B.; Pascaretti-Grizon, F.; Legrand, E.; Lavigne, C.; Audran, M.; Chappard, D. Bone lesions in systemic mastocytosis: Bone histomorphometry and histopathological mechanisms. Morphologie 2020, 104, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Seibel, M.J. Skin and bones: Systemic mastocytosis and bone. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, 22-0408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, T.A.; Henriques, A.F.; Matito, A.; Jara-Acevedo, M.; Caldas, C.; Mayado, A.; Muñoz-González, J.I.; Moreira, A.; Cavaleiro-Rufo, J.; García-Montero, A.; et al. Bone and Cytokine Markers Associated with Bone Disease in Systemic Mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1536–1547, Erratum in J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Hatfield, J.K. Mast Cells are Important Modifiers of Autoimmune Disease: With so Much Evidence, Why is There Still Controversy? Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, L.; Orfao, A.; Villarrubia, J.; Díaz-Agustín, B.; Cerveró, C.; Rios, A.; Velasco, J.L.; Ciudad, J.; Navarro, J.L.; San Miguel, J.F. Immunophenotypic characterization of human bone marrow mast cells. A flow cytometric study of normal and pathological bone marrow samples. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 1998, 16, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, B.; Nixon, R.K. Bone-marrow mast cells in osteoporosis of aging. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 279, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, O.; Savasan, S. The role of mast cells in bone marrow diseases. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004, 57, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collington, S.J.; Williams, T.J.; Weller, C.L. Mechanisms underlying the localisation of mast cells in tissues. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R.; Yeasky, T.; Wei, J.Q.; Miki, R.A.; Cai, K.Q.; Smedberg, J.L.; Yang, W.L.; Xu, X.X. White spotting variant mouse as an experimental model for ovarian aging and menopausal biology. Menopause 2012, 19, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, M.B.; Lotinun, S.; Leontovich, A.A.; Zhang, M.; Maran, A.; Shogren, K.L.; Palama, B.K.; Marley, K.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Turner, R.T. Osteitis fibrosa is mediated by Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-A via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway in a rat model for chronic hyperparathyroidism. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 5735–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.T.; Iwaniec, U.T.; Wong, C.P.; Lindenmaier, L.B.; Wagner, L.A.; Branscum, A.J.; Menn, S.A.; Taylor, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; et al. Acute exposure to high dose gamma-radiation results in transient activation of bone lining cells. Bone 2013, 57, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philbrick, K.A.; Wong, C.P.; Kahler-Quesada, A.M.; Olson, D.A.; Branscum, A.J.; Turner, R.T.; Iwaniec, U.T. Polyethylene particles inserted over calvarium induce cancellous bone loss in femur in female mice. Bone Rep. 2018, 9, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Dang, A.B.; Joshi, S.K.; Halloran, B.; Nissenson, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Kim, H.T.; Liu, X. Novel mouse model of spinal cord injury-induced heterotopic ossification. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2014, 51, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.G.; Torto, R.; Kalra, S.P. Increased leptin expression selectively in the hypothalamus suppresses inflammatory markers CRP and IL-6 in leptin-deficient diabetic obese mice. Peptides 2008, 29, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulombe, J.C.; Maridas, D.E.; Chow, J.L.; Bouxsein, M.L. Small animal DXA instrument comparison and validation. Bone 2024, 178, 116923, Erratum in Bone 2025, 190, 117298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigorev, I.P.; Korzhevskii, D.E. Modern Imaging Technologies of Mast Cells for Biology and Medicine (Review). Sovrem. Tehnol. V. Med. 2021, 13, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).