Abstract

Lafora disease is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in the EPM2A or EPM2B genes, which encode laforin and malin, respectively. These mutations lead to the accumulation of intracellular inclusions of abnormal glycogen, known as Lafora bodies, the hallmark of the disease. Symptoms typically begin in early adolescence with seizures and rapidly progress to cognitive and motor decline, ultimately resulting in dementia and death within a decade of onset. Disruption of Epm2a or Epm2b in mice causes neuronal degeneration and Lafora body accumulation in the brain and other tissues. Epm2a−/− and Epm2b−/− mice exhibit motor and memory impairments, epileptic activity, and molecular and histological abnormalities. We previously demonstrated that intracerebroventricular delivery of a recombinant adeno-associated virus carrying EPM2A significantly improved pathology in Epm2a−/− mice. In this study, we tested recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of the human EPM2B gene in Epm2b−/− mice. The treatment partially improved neurological, molecular, and histopathological outcomes, although some pathological features persisted. Importantly, our findings reveal differences between EPM2A- and EPM2B-based gene therapies, highlighting the need to better understand their distinct mechanisms. Despite limitations, our study provides new insights into the complexity of targeting EPM2B mutations in Lafora disease.

1. Introduction

Lafora disease (LD) (OMIM#254780; ORPHA:501) is a rare, progressive neurodegenerative disorder that initially presents with cognitive deficits, myoclonus, and visual and generalized tonic–clonic seizures [1,2,3]. Onset typically occurs in late childhood or early adolescence, followed by a rapid decline leading to severe dementia, ataxia, dysarthria, aphasia, visual loss, and respiratory failure. This progressive deterioration ultimately results in a vegetative state and death, usually within a decade of symptom onset [4,5,6,7]. LD is caused by more than 100 recessive mutations in the EPM2A gene (OMIM: 607566) [8,9,10], which encodes laforin, a dual-specificity phosphatase [11], or in the EPM2B/NHLRC1 gene (OMIM: 608072) [12,13], which encodes malin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase [14]. Malin contains a RING (Really Interesting New Gene) zinc finger domain, which confers E3-ubiquitin ligase activity, and six NHL domains (NCL1, HT2A, and LIN-41), enabling protein–protein interactions [14]. While malin promotes the degradation of laforin through the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) [14,15], laforin stabilizes malin [16,17]. Recently, it has been shown that malin depends on laforin to interact with other proteins involved in glycogen metabolism [16]. Together, laforin and malin form a functional complex that regulates glycogen metabolism, maintains protein homeostasis, and supports mitochondrial function, oxidative stress regulation, and autophagy [15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. A deficiency in this complex leads to the formation of Lafora bodies (LBs), the hallmark of the disease. These LBs consist of polyglucosans—abnormal, insoluble, and poorly branched forms of glycogen—along with a protein content of 6% to 28% [20,26,27,28,29], placing LD within the family of glycogen storage diseases.

Mouse models lacking laforin (Epm2a−/−) [30] or malin (Epm2b−/−) [31] expression exhibit neurological alterations that closely resemble those observed in patients with LD, including the presence of LBs, dyskinesia, impaired motor activity and coordination, deficits in episodic memory, and epileptic activity. These models also display hyperexcitability, as evidenced by heightened response to the convulsant agent pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) [30,31,32,33]. They have proven valuable for testing potential treatments aimed at alleviating or curing LD symptoms. Recently, we reported that metformin, an AMPK activator [34], produced promising outcomes in these models [35,36,37]. As a result, metformin is now administered globally to patients, helping delay neurological symptoms and improve daily activities [36,38]. Additionally, alternative therapeutic strategies, including sodium selenate [39], VAL-0417 [40,41], antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting Gys 1 [42,43], Myozyme® [44], and other neuroinflammation modulators [45], have been evaluated in these animal models.

We recently demonstrated that a recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) carrying the coding region of the human EPM2A gene (rAAV2/9-CAG-hEPM2A) significantly reduced neurological and histopathological abnormalities, diminished epileptic activity, and decreased the formation of LBs in the Epm2a−/− mouse model [46]. Here, we applied gene therapy using a rAAV vector carrying the human EPM2B (hEPM2B) gene under the control of a CAG promoter, which drives general, widespread expression, in Epm2b−/− mice through a single intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection. This treatment led to significant improvements in key neurological and histopathological parameters, although some pathological hallmarks of the disease were less responsive. Western blot analysis revealed beneficial changes in several molecular mediators associated with neuroinflammation and cell death, with these partial improvements persisting up to nine months after ICV injection. Notably, compared to our previously reported results with EPM2A gene therapy [46], the outcomes achieved through EPM2B restoration were less robust. These findings underscore critical differences between EPM2A- and EPM2B-based gene therapy approaches and highlight the need for further investigation to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this divergent therapeutic response.

2. Results

2.1. ICV Injections of the rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-GFP Vectors Enable Efficient Brain Transgene Transcription and Translation

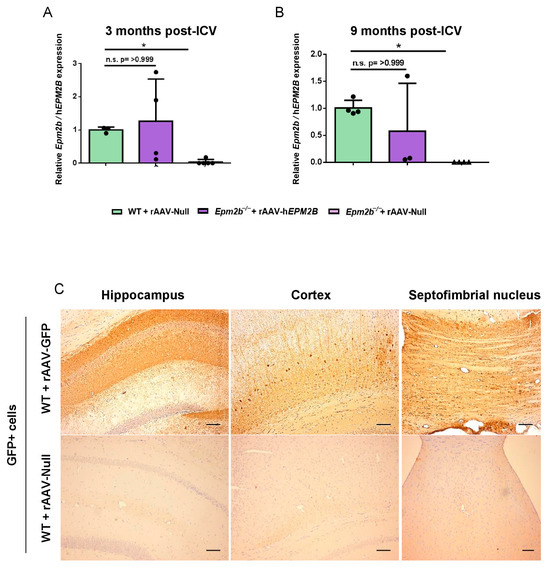

Three and nine months after a single ICV injection of rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null vectors into the brains of 3-month-old Epm2b−/− and WT mice, the expression of the hEPM2B transgene was measured using RT-qPCR (Figure 1A,B). The results showed that levels of hEPM2B transcripts in Epm2b−/− mice, at both 3 and 9 months post-injection, were comparable to the levels of Epm2b transcripts in WT animals. Due to the lack of effective antibodies for detecting the malin protein, we used a rAAV2/9 vector with the CAG promoter carrying the GFP reporter gene to analyze vector biodistribution in the central nervous system. Three months after ICV injection of the rAAV-GFP vector in WT mice, immunohistochemical analysis revealed widespread GFP expression throughout the hippocampus, cortex, and the septofimbrial nucleus (Figure 1C). This indicates that a single ICV injection of the rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-GFP vectors enables the transcription of the hEPM2B or GFP transgenes and the translation of the GFP protein (and, by inference, the malin protein) within the central nervous system of Epm2b−/− and WT mice.

Figure 1.

Analysis of hEPM2B transcription and GFP expression in the brain 3 and 9 months after a single ICV injection of the rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-GFP vectors: (A,B) RT-qPCR quantification of Epm2b cDNA levels in the brains of WT, and hEPM2B cDNA levels in the brains of Epm2b−/− mice, 3 (A) and 9 (B) months post-injection, normalized to housekeeping Gapdh levels. Data are shown as mean ± SD. (C) Biodistribution of the rAAV2/9 vector in the brain of WT mice 3 months after ICV injection of the rAAV-GFP vector, analyzed by immunohistochemistry with a GFP antibody. Left panel, hippocampus; central panel, cortex; right panel, septofimbrial nucleus. * p < 0.05. n = 3–5 mice per group Scale bar = 100 µm.

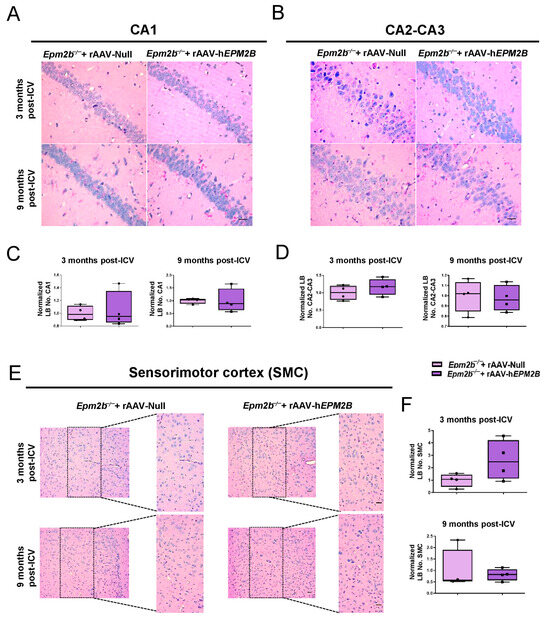

2.2. The rAAV-hEPM2B Vector Does Not Reduce LB Formation in the Brains of Epm2b−/− Mice

PAS-D staining was used to identify LBs within the CA1 (Figure 2A,C) and CA2-CA3 (Figure 2B,D) regions of the hippocampus, and layers IV-V of the sensorimotor cortex (SMC) (Figure 2E,F). LBs were quantified 3 and 9 months following administration of either the rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null vectors. No therapeutic benefit was observed, since there was no reduction in the number of LBs in any of the ages or regions analyzed.

Figure 2.

Quantification of LB formation in the brains of Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null: (A,B,E) PAS-D staining in the CA1 (A) and CA2-CA3 (B) regions of the hippocampus, and in layers IV-V of the SMC (E) to analyze LB formation in Epm2b−/− mice 3 and 9 months after a single ICV injection. (C,D,F) Quantitative comparison of LB numbers in the CA1 (C) and CA2-CA3 (D) regions of the hippocampus, and in layers IV-V of the SMC (F), 3 and 9 months post-treatment. LB quantification in the SMC was conducted within the enlarged region (width: 747 px; height: 1550 px), corresponding to layers IV-V. Results are expressed as the median of independent samples, with boxplot bars indicating minimum and maximum values. Values were normalized using data from Epm2b−/− mice injected with rAAV-Null as a reference. Statistical analysis was conducted using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney test. n = 4 mice per group. Scale bars = 25 µm in (A,B); 50 µm in (E).

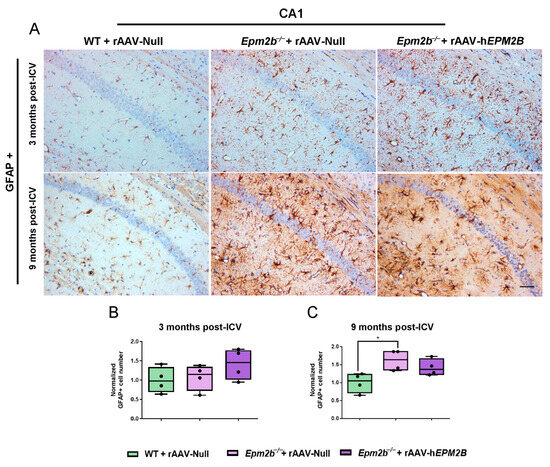

2.3. Treatment with rAAV-hEPM2B Partially Reduces Astrogliosis, Microgliosis, and Neuronal Loss in Epm2b−/− Mice

To assess the effects of rAAV-hEPM2B administration on neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Epm2b−/− mice, we quantified GFAP-, Iba1- and NeuN-positive cells in the CA1 (Figure 3, Figure 4A–C and Figure S2, respectively) and CA2-CA3 (Figure S1A–C, Figure 4D–F; Figure S3A–C; respectively) regions of the hippocampus, as well as in layers IV-V of the SMC (Figure S1D–F and Figure S3D–F, respectively). Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-Null displayed increased astrogliosis (measured as the presence of the GFAP marker) in the CA1 hippocampal region 9 months post-ICV injection, with significant differences compared to the control group (Figure 3). Treatment with the rAAV-hEPM2B vector showed a tendency to reduce astrogliosis in this region, reaching similar levels to those seen in WT mice 9 months post-treatment (Figure 3A,C). However, no significant differences were observed in other regions analyzed (CA2-CA3 region of the hippocampus and layers IV–V of the SMC) at either 3 or 9 months post-treatment (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Analysis of astrogliosis in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in Epm2b−/− mice 3 and 9 months post-injection: (A) Representative images of GFAP immunostaining in the CA1 field of the hippocampus 3 and 9 months after rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null administration in Epm2b−/− mice. (B,C) Quantification of GFAP-positive cells expressed as the median of independent samples. Boxplot bars indicate minimum and maximum values. Data were normalized to levels observed in WT mice injected with rAAV-Null. Statistical analysis was conducted using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. * p < 0.05. n = 4 mice per group. Scale bar = 50 µm.

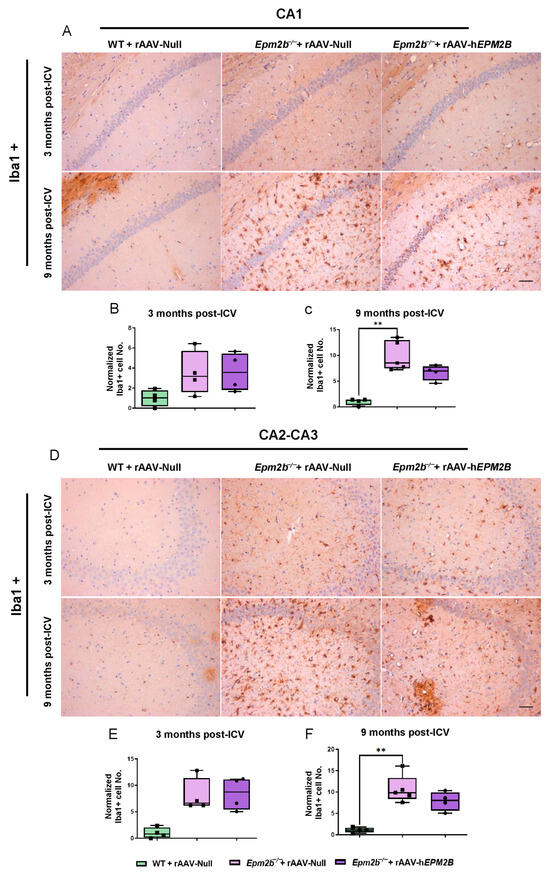

Figure 4.

Microgliosis in the hippocampus of Epm2b−/− mice: (A,D) IHC with an anti-Iba1 antibody to localize microglia. (B,C,E,F) Quantitative analysis of microgliosis in the CA1 (B,C) and CA2-CA3 (E,F) regions of the hippocampus of WT mice injected with rAAV-Null and Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null, 3 months (B,E) and 9 months (C,F) post-treatment. Results are expressed as the median of independent samples, with bars in the boxplots representing minimum and maximum values. Values were normalized to those of WT mice injected with rAAV-Null. Statistical analysis was performed using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. ** p < 0.01. n = 4 mice per group. Scale bars = 50 µm.

We also analyzed microgliosis in the CA1 and CA2-CA3 regions of the hippocampus and in layers IV–V of the SMC in Epm2b−/− mice 3 and 9 months post-injection (Figure 4). The hippocampus of Epm2b−/− mice treated with the rAAV-hEPM2B vector displayed a reduction in microgliosis compared to those injected with the rAAV-Null vector, which exhibited a significant increase in microgliosis relative to the control group, 9 months after injection. This reduction was observed in both the CA1 (Figure 4A–C) and CA2-CA3 (Figure 4D–F) regions of the hippocampus. However, no significant differences were detected 3 months after treatment in any analyzed regions of the hippocampus (Figure 4B,E), nor in layers IV–V of the SMC either 3 or 9 months after ICV administration.

Neuronal loss analysis in Epm2b−/− mice, 3 and 9 months after rAAV-hEPM2B treatment, revealed a partial increase in NeuN-positive cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Figure S2). However, despite this trend, the differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure S2B,C). No significant differences were observed between experimental groups in the CA2-CA3 region (Figure S3A–C) or in layers IV–V of the SMC (Figure S3D–F).

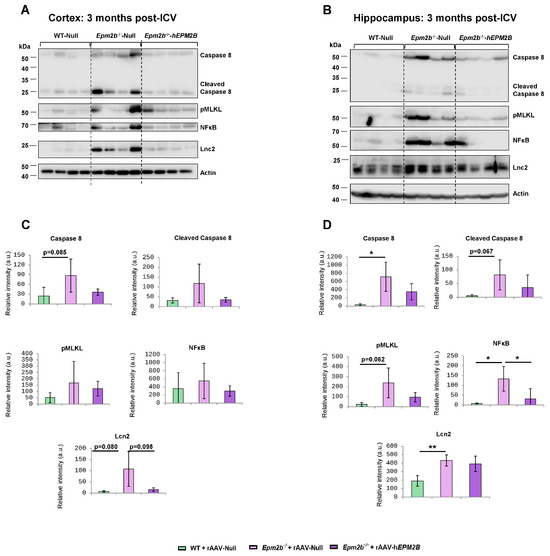

2.4. Treatment with rAAV-hEPM2B Reduces the Levels of Neuroinflammatory and Cell Death Markers in Epm2b−/− Mice

Neuroinflammation has recently been identified as a significant and novel feature of LD, contributing to its pathogenesis and progression. To obtain a deeper understanding of the potential beneficial effects of rAAV-hEPM2B on various neuroinflammatory mediators in LD, we analyzed the levels of caspase-8, the phosphorylated form of the mixed lineage kinase domain-like (pMLKL) protein, NF-kB, chemokine CXCL10, and lipocalin 2 (Lcn2), as described in [47,48], in cortical and hippocampus extracts from WT mice injected with rAAV-Null and Epm2b−/− mice treated with either rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null. Three and nine months post-injections, Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-Null exhibited increased levels of several neuroinflammatory markers in the cortex and, especially, in the hippocampus compared to WT mice (Figure 5 and Figure S4). Interestingly, Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B showed a reduction in some of these markers (Figure 5 and Figure S4). A significant decrease in NF-kB levels was observed in the hippocampus 3 months after ICV injection, with a clear trend toward reduced caspase-8, pMLKL, and Lcn2 expression, the latter particularly evident in the cortex (Figure 5). Notably, this trend was sustained up to 9 months post-treatment, although differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure S4). These findings suggest that rAAV-hEPM2B administration may exert a sustained modulatory effect on specific components of the neuroinflammatory response, especially in the hippocampus.

Figure 5.

Levels of caspase-8 and NFkB in the cortex and hippocampus 3 months post-ICV injection of rAAV-Null or rAAV-hEPM2B in WT and Epm2b−/− mice: (A–D) Protein levels of caspase-8 (full length and cleaved), NFκB, and actin assessed by Western blot in cortical (A,C) and hippocampal (B,D) extracts from WT mice injected with rAAV-Null and Epm2b−/− mice treated with either rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null. Molecular weight standards are shown on the left. Densitometric quantification of the blots (C,D) was carried out as described in the Section 4, with values normalized to actin and represented as arbitrary units (a.u.). Four independent samples from each genotype were analyzed. Results are expressed as means +/− standard deviation (SD). Differences between paired samples were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-tests using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 statistical software (La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was considered at * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01.

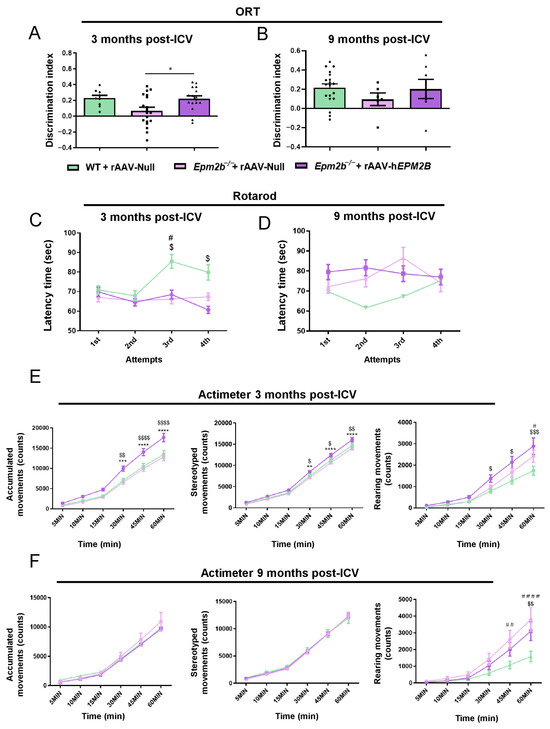

2.5. rAAV-hEPM2B-Based Gene Therapy Reverses Episodic Memory Alterations and Improves Spontaneous Locomotor Activity but Does Not Correct Motor Coordination Impairments in Epm2b−/− Mice

Object recognition task (ORT) was performed to evaluate the episodic memory state in Epm2b−/− mice 3 and 9 months after the administration of rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null vectors (Figure 6A,B). Memory performance was significantly improved in Epm2b−/− mice 3 months after treatment to levels comparable to WT mice, as indicated by the recovery of the D.I. between the old and new object (Figure 6A). However, 9 months after treatment (Figure 6B), the differences between WT and Epm2b−/− mice injected with the rAAV-Null or rAAV-hEPM2B vectors were not statistically significant. Despite this, Epm2b−/− mice treated with the rAAV-hEPM2B vector showed a tendency to recover the mild memory deficits present in aged Epm2b−/− mice (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Behavioral assessments in Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B, and in Epm2b−/− and WT mice injected with rAAV-Null: (A,B) Memory performance based on the D.I. obtained from the ORT, 3 (A) and 9 (B) months post-ICV injection. (C,D) Evaluation of motor coordination based on the latency to fall from the cylinder in the rotarod test, 3 (C) and 9 (D) months post-ICV treatment (# WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-Null; $ WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-hEPM2B). (E,F) Analysis of spontaneous accumulated, stereotyped, and rearing movements recorded over one hour in the actimeter, 3 (E) and 9 (F) months after ICV injection (* Epm2b−/− + rAAV-hEPM2B vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-Null; # WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-Null; $ WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b-/- + rAAV-hEPM2B). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparison between groups was conducted using one- and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. n = 15–25 mice per group per experiment.

Assessment of motor coordination with the rotarod test revealed that Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null vectors remained on the rod for a shorter period than WT mice 3 months after injection (Figure 6C), although no differences were found 9 months after treatment administration (Figure 6D).

Examination of spontaneous motor activity showed that rAAV-hEPM2B treatment led to an improvement in spontaneous accumulated, stereotyped, and rearing movements 3 months post-injection (Figure 6E). Epm2b−/− treated mice presented higher spontaneous locomotor activity than WT control mice, indicating some level of hyperactivity (Figure 6E). However, 9 months after treatment, Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B showed no differences in locomotor activity in comparison to rAAV-Null treated mice (Figure 6F).

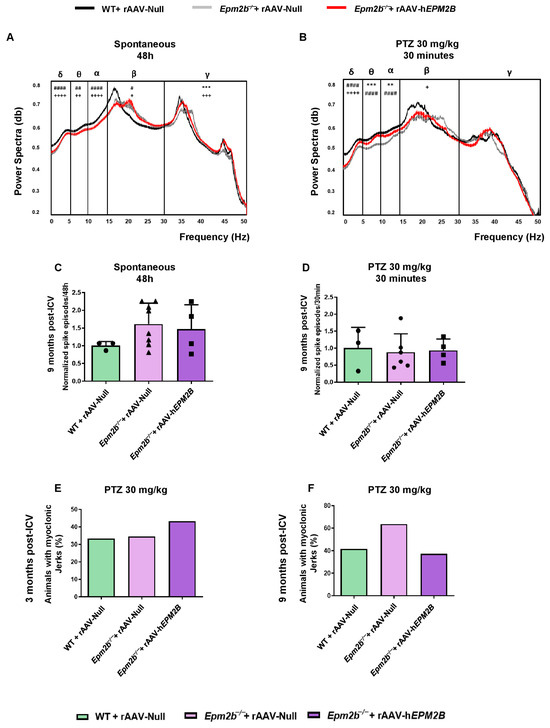

2.6. Treatment with rAAV-hEPM2B in Epm2b−/− Mice Does Not Improve Spontaneous Electrical Brain Activity or Reduce PTZ Sensitivity

To analyze epileptic-like activity, we performed video-EEG recordings 9 months after treatment (Figure 7A,B). Analysis of basal activity rhythms revealed an altered EEG in Epm2b−/− mice injected with rAAV-Null or rAAV-hEPM2B vectors (Figure 7A). After intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg PTZ, power spectra were decreased in all experimental groups, possibly reflecting a desynchronization of neuronal firing induced by the compound (Figure 7B). Both Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null showed a significantly decreased power spectrum of delta low-frequency waves. Notably, gene therapy normalized power spectra in both theta and alpha frequency waves after PTZ injection; however, only Epm2b−/− mice treated with the rAAV-hEPM2B vector exhibited lower beta wave power spectra (Figure 7B). These findings suggest a differential impact of gene therapy on specific frequency bands.

Figure 7.

EEG and PTZ susceptibility analysis in WT and Epm2b−/− mice 3 and 9 months post-ICV injection of rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null vectors: (A) Representative normalized power spectra from baseline EEG recordings over a 48 h period. (B) Representative normalized power spectra from EEG recordings after IP injection of subconvulsive doses of PTZ (30 mg/kg). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was performed on the areas under the curve obtained by plotting EEG powers across all experimental groups. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; + p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, +++ p < 0.001, ++++ p < 0.0001; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001 (+ WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-hEPM2B; # WT + rAAV-Null vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-Null; Epm2b−/− + rAAV-hEPM2B vs. Epm2b−/− + rAAV-Null). n = 3–6 mice per group. (C) Spontaneous interictal spikes and (D) PTZ-induced interictal spikes in WT and Epm2b−/− mice 9 months after ICV administration of rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null. A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test was used. Data are shown as normalized mean ± SEM, with values normalized to those of WT mice injected with rAAV-Null values. n = 3–8 mice per group. (E,F) Percentage of animals displaying myoclonic jerks after IP injection of 30 mg/kg PTZ in WT and Epm2b−/− mice 3 (E) or 9 (F) months after ICV injection. Data are shown as percentages, with Fisher’s exact test applied between experimental groups. n = 15–25 mice per group per experiment.

Epm2b−/− mice treated with rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null exhibited a similar amount of spontaneous interictal spikes compared to WT mice (Figure 7C). Furthermore, after administration of 30 mg/kg PTZ, all groups displayed a comparable amount of interictal spikes (Figure 7D). The same percentage of mice displayed myoclonic jerks 3 (Figure 7E) and 9 (Figure 7F) months after rAAV-hEPM2B or rAAV-Null injections.

3. Discussion

Gene therapy-based strategies are considered promising therapeutic approaches for monogenic diseases. We recently reported a gene therapy approach aimed at inducing laforin expression in the Epm2a−/− mouse model using a rAAV vector containing the coding region of the human EPM2A gene. A single ICV injection of this vector resulted in significant neurological improvements [46]. In the present study, we demonstrate that restoring EPM2B gene expression with a rAAV vector in the Epm2b−/− mouse model reverses some neurological impairments, although the therapeutic effects were less pronounced compared to restoring laforin function in Epm2b−/− mice [46].

RT-qPCR analysis of brain samples revealed that ICV administration of the rAAV-hEPM2B vector achieved EPM2B transgene expression levels in Epm2b−/− mice comparable to endogenous Epm2b expression in WT controls. Due to the lack of reliable malin-specific antibodies, we used a rAAV2/9 vector carrying the GFP reporter gene under the same CAG promoter to assess vector biodistribution throughout the central nervous system. Consistent with our previous findings [46], the rAAV-GFP vector transduced the hippocampus, cortex, and fimbria. Based on these results, we assumed a similar distribution pattern for malin expression.

We evaluated the effect of a single ICV injection of the rAAV-hEPM2B vector on LB formation in Epm2b−/− mice at 3 and 9 months post-treatment. Unlike the recovery of the hEPM2A gene expression in Epm2a−/− mice [46], restoration of hEPM2B gene expression in Epm2b−/− mice did not reduce LB accumulation. These findings contrast with a recent report showing beneficial effects of restoring malin function in Epm2b−/− mice containing an inducible malin expression cassette [49]. In that study, the authors showed that although malin expression did not degrade insoluble glycogen or remove preexisting LBs, it prevented further LB accumulation [49]. The lack of LB reduction observed in our study may be attributed to insufficient hEPM2B expression. As noted above, RT-qPCR analyses confirmed transgene expression; however, the malin protein may not be as stable as its endogenous murine counterpart.

The formation of a functional laforin-malin complex is essential for recruiting malin to glycogen particles and regulating glycogen synthesis [16]. It has been shown that brains from Epm2b−/− mice exhibit increased levels of laforin in the insoluble fraction of brain extracts compared to WT mice [19,31,50], a fraction that also displays a marked increase in insoluble glycogen [19]. This elevated laforin content likely results from the absence of malin-dependent ubiquitination. These results suggest that laforin, found in the LBs of Epm2b−/− mice [51], may be bound to insoluble glycogen, thereby rendering it inactive or functionally impaired. The expressed malin protein may therefore not fully interact with endogenous murine laforin, resulting in an incomplete or non-functional complex. Unfortunately, the lack of a reliable antibody to detect malin expression hinders our ability to further explore that option. Importantly, in a recent study, we administered an rAAV-based malin gene therapy systemically at a presymptomatic stage (1 month old) and observed a clear reduction in LB formation. These findings strongly support our hypothesis and highlight that treatment timing is a key determinant of therapeutic success [52].

Treatment with the rAAV-hEPM2B vector in Epm2b−/− mice reduces neuroinflammation, as evidenced by decreased levels of GFAP, Iba1, and different pro-inflammatory mediators. These results are consistent with previous findings obtained following malin recovery [49]. Despite a direct relationship between polyglucosan accumulation and neuroinflammation [53], malin also modulates inflammatory pathways independently of the laforin-malin complex [48,54,55]. Our results show that restoring malin function in Epm2b−/− mice reduces neuroinflammation, thereby improving specific behavioral impairments, including defects in episodic memory and spontaneous locomotor activity. Although treated mice display higher locomotor activity than WT controls, this increase is interpreted as a functional improvement consistent with other molecular and behavioral corrections. Nevertheless, it should be noted that partial restoration could theoretically result in a new, non-physiological behavioral state.

Seizures represent one of the most severe symptoms and can result in heightened morbidity and mortality in LD patients. We evaluated the efficacy of a single ICV injection of the rAAV-hEPM2B vector on epileptic activity in Epm2b−/− mice 9 months after treatment administration. Video-EEG and PTZ sensitivity tests showed that rAAV-hEPM2B-based gene therapy did not restore normal brain electrical activity or normal neuronal excitability. This lack of antiepileptic benefit of the rAAV-hEPM2B vector could be associated with the inability of malin to form a functional complex with laforin, which regulates the abundance of several proteins involved in neuronal excitability [46]. The absence of this complex not only leads to LB accumulation but may also disrupt additional laforin–malin–dependent regulatory mechanisms beyond glycogen metabolism, both of which could contribute to neuronal hyperexcitability and seizure susceptibility [25,43,46,56,57,58,59,60].

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that rAAV-based gene therapy, inducing malin expression with the coding region of the human EPM2B gene, produces relevant therapeutic benefits in the Epm2b−/− mouse model. However, its efficacy is lower than that observed following laforin restoration in the Epm2a−/− mouse model. Further studies and alternative strategies are required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this divergent therapeutic response and to develop an effective therapy for LD patients carrying EPM2B mutations.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

The colonies of Epm2b−/− and WT mice were housed in isolated cages within a controlled environment at the Animal Facility Service of the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria-Fundación Jiménez Díaz. The conditions included a 12:12 light/dark cycle, a constant temperature of 23 °C, and ad libitum access to food and water. Animal welfare was prioritized throughout the experiments, with efforts made to minimize distress and to use the minimum number of animals necessary for sacrifice. Since no gender-related phenotypic differences have been described in mice or patients with LD, data from male and female mice were analyzed interchangeably. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines [61], as well as the ethical standards set by the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria-Fundación Jiménez Díaz Ethical Review Board, the European Communities Council Directive (2010/63/EU), and the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 86–23, updated 1985).

4.2. Production of rAAV2/9-CAG-hEPM2B, rAAV2/9-CAG-Null and rAAV2/9-CAG-GFP Vectors

The rAAV2/9-CAG-hEPM2B (rAAV-hEPM2B) vector, carrying the cDNA of the hEPM2B gene (NM_198586.3), the rAAV2/9-CAG-Null (rAAV-Null) vector, and the rAAV2/9-CAG-GFP (rAAV-GFP) vector were produced at the Unitat de Producció de Vectors (UPV_ www.viralvector.eu, accessed on 2 March 2021). These vectors were generated following the triple transfection system: (a) the ITR-containing plasmid; (b) the plasmid encoding the AAV capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3) and replicate genes; and (c) the adenoviral helper plasmid. AAV vectors were purified using iodixanol-based ultracentrifugation to remove empty capsids [62].

4.3. Stereotaxic ICV Injections

Stereotaxic ICV injections were performed at 3 months of age, as previously described [46]. Epm2b−/− and WT mice received a single ICV injection of either rAAV-hEPM2B, rAAV-Null, or rAAV-GFP vectors. To induce anesthesia, 4% isoflurane and 2% oxygen were administered, while 2% isoflurane and 1.5% oxygen were used to maintain it. The mice were secured in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Illinois, USA). To ensure hydration, a subcutaneous saline injection (1 mL) was given, and ophthalmic gel was applied to prevent dry eyes. A heating pad was used to maintain a body temperature of 37 °C. After sterilizing the area with 70% ethanol, a 2 cm incision was made behind the eyes. H2O2 was used to mark the bregma and lambda spots on the skull. A small burr hole was drilled using the coordinates of the right cerebral lateral ventricle (anteroposterior −0.3 mm, mediolateral −0.9 mm, and dorsoventral −2.5 mm). Then, using a Hamilton® syringe (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat. #10664301), 3 µL of viral suspension (titer: 1.26 × 1012 vg/mL) was administered at a rate of 1 µL/min. After suturing the incision, analgesia was provided by administering 5 mg/kg of meloxicam (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany). A total of 40 mice were used in each group and condition.

4.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Brain tissues were homogenized on ice using TRIzolTM Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to extract RNA. The extracted RNA pellets were cleaned, dried, and resuspended before applying DNase Enzyme (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove any DNA traces. Quantification was carried out using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). For RT-PCR, 1 µg of RNA per reaction was used with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase inhibitor (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RT-PCR settings were as follows: 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 120 min, and 85 °C for 5 min. The resulting hEPM2B cDNA was used as a template for quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR), performed using TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Probes used included Epm2b (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Mm00614667_s1; Cat: #4331182), EPM2B (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Hs01112790_s1; Cat: #4331182), and Gapdh (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Mm99999915_g1; Cat: #4448491). qPCR conditions were: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 1 sec and 60 °C for 20 sec. Triplicates of each sample were analyzed, and results were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

4.5. PAS-Diastase Staining and Immunohistochemistry

PAS-diastase (PAS-D), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence in paraffin (IF-P) procedures were performed following the protocol described in [46,63]. Sections were rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of alcohol. For PAS-D staining, they were treated with porcine pancreas α-amylase (5 mg/mL in dH2O) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), processed with the PAS Kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and counterstained with Gill No. 3 hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). For IHC, rehydrated sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Samples were then incubated in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, 5% fetal bovine serum, 2% Triton X-100, diluted in PBS), followed by incubation with primary antibodies diluted in the same blocking buffer. The primary antibodies used were green fluorescent protein (GFP) (1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Cat. #ab183734), Neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (1:100 dilution; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA; Cat. # MAB377), ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) (1:100 dilution; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA; #MA536257), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (1:1000 dilution; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA; Cat. #MAB360). After incubation, sections were treated with biotinylated secondary antibodies, stained with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), visualized with diaminobenzidine (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) and H2O2, and counterstained with Carazzi hematoxylin (Panreac Quimica, Barcelona, Spain).

Two consecutive sections per animal from 4–6 mice were analyzed in the CA1 and CA2-CA3 regions of the hippocampus and layers IV-V of the SMC. Immunoreactivity was quantified by two researchers using ImageJ 1.54g software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), with results reported as the means of both quantifications.

4.6. Western Blot Analyses

Samples from the mouse brain (hippocampus and cortex) were lysed in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 1% Nonidet P40; 1mM PMSF; and a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Barcelona, Spain)] for 30 min at 4 °C with occasional vortexing. The lysates were passed ten times through a 25-gauge needle in a 1 mL syringe and centrifuged at 13,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected, and 35 μg protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS-T: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4; with 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the corresponding primary antibodies: anti-NF-kB (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX, USA, Sc-8008), anti-caspase-8 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA, 9746), anti-phospho (Ser345)-MLKL (Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA, MABC1158), anti-CXCL10 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab9938) and anti-Lipocalin2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab63929). Anti-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, A2066) was used as a housekeeping antibody. Membranes were then probed with suitable secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were detected using chemiluminescence with ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Cytiva-Amersham, Marlborough, MA, USA, RPN2232) and imaged using the Fuji-LAS-4000 system (GE Healthcare, Barcelona, Spain). The results were analyzed using the software Image Studio Lite version 5.2 (LI-COR Biosciences, Bad Homburg, Germany). Experiments were performed on at least three individuals from each genotype, including both males and females.

4.7. Object Recognition Task

The ORT was used to analyze episodic memory. It involved habituating mice to a dark open field box for 10 min. After a 2 h break, two identical objects, A and B, were placed in the center of the box. The mice were allowed to explore both objects freely, and the time spent examining each object (tA and tB) was recorded. The same test was repeated 2 h later, but object B was replaced with a new object, C. The mice’s exploration times (tA and tC) were measured using virtual timers generated by XNote Stopwatch 1.68 software, which were activated when the mice inspected the object from a distance of 2 cm or less. The discrimination index (D.I.) was calculated using the following formula: D.I. = (tC − tA)/(tC + tA) [63].

4.8. Motor Coordination

To evaluate the balance and motor coordination of mice, the rotarod test (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) was used. After two days of training, only those mice that could stay on the cylinder for at least 60 s were included in the analysis. The latency time to fall from the rotating cylinder was measured twice a day, with each session lasting a maximum of five minutes, as the speed increased from 4 rpm to 40 rpm [63].

4.9. Spontaneous Locomotor Activity

Spontaneous movements of mice were monitored using a computerized actimeter (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The device detects breaks in an infrared light beam and records mouse crossings in an open field. SEDACOM 1.4 software (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) was used to analyze spontaneous, rearing, and stereotyped movements at 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min [63].

4.10. Video-EEG Recording

A plastic pedestal with trimmed electrodes (Plastics1, Roanoke, VA, USA) was surgically implanted onto the skull and secured with acrylic resin. To alleviate post-surgical pain, meloxicam (5 mg/kg) (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) was administered to the animals. Following the surgery, mice were given one week to recover before video-EEG testing began. The recordings were performed using a wireless transmitter (Epoch, BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA) attached to the pedestal, and data were digitally recorded on a computer under free-motion conditions. Mice were observed in their cages for 2 days under basal conditions. Afterwards, they were recorded for 30 min following PTZ injections. The recordings were done at a sampling rate of 250 Hz, and a 50 Hz notch filter was applied. Digital video cameras were used to capture their behavior. The EEG data were analyzed both automatically and manually using Acknowledge® 5.0 software (Epoch, BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA). Any signal loss or artifacts were identified and excluded. Power spectra were calculated using a spectral estimator derived from autoregressive processes, ensuring normalized amplitudes for consistent peak-to-peak ranges. The Comb Band Stop filter and a Blackman window were then applied. Automated seizure analysis was conducted, which included monitoring interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) and seizures [46,63].

4.11. Sensitivity to PTZ

PTZ (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was administered intraperitoneally to mice at subconvulsive doses (30 mg/kg). This treatment was used to assess the percentage of mice exhibiting myoclonic jerks. The study lasted for 45 min, and each animal was examined by two different researchers [63].

4.12. Statistical Analysis

For behavioral tests, PTZ-based studies, and electrophysiology, a minimum of 12 mice per genotype were examined. For video-EEG and RT-qPCR assays, 4–6 mice per genotype were used. For immunohistochemistry and Western blot experiments, 4–8 mice per genotype were analyzed. The values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), mean ± standard deviation (SD), or as percentages. To assess differences between experimental groups, one- or two-way ANOVA, Fisher’s exact test, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, or the Mann–Whitney test were used, as appropriate for each specific case. For EEG analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to compare differences in the power spectra between groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the statistical significance thresholds were set at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262411930/s1.

Author Contributions

L.Z.-P., conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writingreview and editing; N.I.-C., investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; P.S., conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; M.A.G.-G., data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; G.S.-M., investigation, methodology; M.P.S., conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; J.M.S., conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy [Rti2018-095784b-100SAF MCI/AEI/FEDER, UE] to J.M.S. and M.P.S.; from the Tatiana Perez de Guzman el Bueno Foundation to M.P.S. and J.M.S.; from the Fondazione Malattie Rare Mauro Baschirotto BIRD Onlus to M.P.S. and L.Z.P; from the AEVEL Foundation to J.M.S. and L.Z.P.; from the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER) [ACCI 2020, 23—U744 and—742] to J.M.S., P.S. and M.P.S.; and from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health [P01NS097197], which established the Lafora Epilepsy Cure Initiative (LECI), to J.M.S, P.S. and M.P.S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving animals were carried out in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines [61], and in compliance with the ethical standards set by the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria-Fundación Jiménez Díaz Ethical Review Board, the European Community Council Directive (2010/63/EU), and the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 86–23, revised 1985) approval date: 4 December 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miguel Chillón Rodríguez (Viral Vector Production Unit of UPV-UAB-VHIR) for the generation of rAAVs and technical advice, and the Animal Facility of the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria-Fundación Jiménez Díaz, for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lafora, G.R.; Glueck, B. Beitrag zur Histopathologie der Myoklonischen Epilepsie. Z. Die Gesamte Neurol. Und Psychiatr. 1911, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovic, S.F.; Andermann, F.; Carpenter, S.; Wolfe, L.S. Progressive myoclonus epilepsies: Specific causes and diagnosis. New Engl. J. Med. 1986, 315, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heycoptenhamm, V.; Jager, D.J.E. Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy with Lafora Bodies. Clin. Pathol. Features 1963, 4, 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Harriman, D.G.; Millar, J.H.; Stevenson, A.C. Progressive familial myoclonic epilepsy in three families: Its clinical features and pathological basis. Brain A J. Neurol. 1955, 78, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, G.A.; Yanoff, M. Lafora’s disease. Distinct clinico-pathologic form of unverricht’s syndrome. Arch. Neurol. 1965, 12, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desdentado, L.; Espert, R.; Sanz, P.; Tirapu-Ustarroz, J. Lafora disease: A review of the literature. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 68, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.; Tiberia, E.; Striano, P.; Genton, P.; Carpenter, S.; Ackerley, C.A.; Minassian, B.A. Lafora disease. Epileptic Disord. Int. Epilepsy J. Videotape 2016, 18, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratosa, J.M.; Delgado-Escueta, A.V.; Posada, I.; Shih, S.; Drury, I.; Berciano, J.; Zabala, J.A.; Antúnez, M.C.; Sparkes, R.S. The gene for progressive myoclonus epilepsy of the Lafora type maps to chromosome 6q. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratosa, J.M.; Gómez-Garre, P.; Gallardo, M.E.; Anta, B.; de Bernabé, D.B.; Lindhout, D.; Augustijn, P.B.; Tassinari, C.A.; Malafosse, R.M.; Topcu, M.; et al. A novel protein tyrosine phosphatase gene is mutated in progressive myoclonus epilepsy of the Lafora type (EPM2). Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, B.A.; Lee, J.R.; Herbrick, J.A.; Huizenga, J.; Soder, S.; Mungall, A.J.; Dunham, I.; Gardner, R.; Fong, C.Y.; Carpenter, S.; et al. Mutations in a gene encoding a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase cause progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat. Genet. 1998, 20, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, S.; Agarwala, K.L.; Ueda, K.; Akagi, T.; Shoda, K.; Usui, T.; Hashikawa, T.; Osada, H.; Delgado-Escueta, A.V.; Yamakawa, K. Laforin, defective in the progressive myoclonus epilepsy of Lafora type, is a dual-specificity phosphatase associated with polyribosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 2251–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.M.; Bulman, D.E.; Paterson, A.D.; Turnbull, J.; Andermann, E.; Andermann, F.; Rouleau, G.A.; Delgado-Escueta, A.V.; Scherer, S.W.; Minassian, B.A. Genetic mapping of a new Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy locus (EPM2B) on 6p22. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.M.; Young, E.J.; Ianzano, L.; Munteanu, I.; Zhao, X.; Christopoulos, C.C.; Avanzini, G.; Elia, M.; Ackerley, C.A.; Jovic, N.J.; et al. Mutations in NHLRC1 cause progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat. Genet. 2003, 35, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, M.S.; Worby, C.A.; Dixon, J.E. Insights into Lafora disease: Malin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of laforin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8501–8506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilchez, D.; Ros, S.; Cifuentes, D.; Pujadas, L.; Vallès, J.; García-Fojeda, B.; Criado-García, O.; Fernández-Sánchez, E.; Medraño-Fernández, I.; Domínguez, J.; et al. Mechanism suppressing glycogen synthesis in neurons and its demise in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurat, A.V.; Segvich, D.M.; Contreras, C.J.; Hu, Y.C.; Hurley, T.D.; DePaoli-Roach, A.A.; Roach, P.J. Impaired malin expression and interaction with partner proteins in Lafora disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romá-Mateo, C.; Sanz, P.; Gentry, M.S. Deciphering the role of malin in the lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy. IUBMB Life 2012, 64, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaz-Fuster, M.C.; Gimeno-Alcañiz, J.V.; Ros, S.; Fernandez-Sanchez, M.E.; Garcia-Fojeda, B.; Criado Garcia, O.; Vilchez, D.; Dominguez, J.; Garcia-Rocha, M.; Sanchez-Piris, M.; et al. Regulation of glycogen synthesis by the laforin-malin complex is modulated by the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaoli-Roach, A.A.; Tagliabracci, V.S.; Segvich, D.M.; Meyer, C.M.; Irimia, J.M.; Roach, P.J. Genetic depletion of the malin E3 ubiquitin ligase in mice leads to lafora bodies and the accumulation of insoluble laforin. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25372–25381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, M.S.; Guinovart, J.J.; Minassian, B.A.; Roach, P.J.; Serratosa, J.M. Lafora disease offers a unique window into neuronal glycogen metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 7117–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernia, S.; Rubio, T.; Heredia, M.; Rodríguez de Córdoba, S.; Sanz, P. Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and decreased proteasomal function in lafora disease models lacking the phosphatase laforin. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romá-Mateo, C.; Aguado, C.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Ibáñez-Cabellos, J.S.; Seco-Cervera, M.; Pallardó, F.V.; Knecht, E.; Sanz, P. Increased oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant response in Lafora disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 51, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romá-Mateo, C.; Aguado, C.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Knecht, E.; Sanz, P.; Pallardó, F.V. Oxidative stress, a new hallmark in the pathophysiology of Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahuerta, M.; Aguado, C.; Sánchez-Martín, P.; Sanz, P.; Knecht, E. Degradation of altered mitochondria by autophagy is impaired in Lafora disease. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 2071–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Gruart, A.; García-Rocha, M.; Delgado-García, J.M.; Guinovart, J.J. Glycogen accumulation underlies neurodegeneration and autophagy impairment in Lafora disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3147–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafora, G.R. Über das Vorkommen amyloider Körperchen im Innern der Ganglienzellen. Virchows Arch. Für Pathol. Anat. Und Physiol. Und Für Klin. Med. 1911, 205, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, S.; Austin, J.; Witmer, F.; Sakai, M. Studies in myoclonus epilepsy (Lafora body form). I. Isolation and preliminary characterization of Lafora bodies in two cases. Arch. Neurol. 1968, 19, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, M.; Austin, J.; Witmer, F.; Trueb, L. Studies in myoclonus epilepsy (Lafora body form) II. Polyglucosans in the systemic deposits of myoclonus epilepsy and in corpora amylacea. Neurology 1970, 20, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.A.; Nitschke, S.; Steup, M.; Minassian, B.A.; Nitschke, F. Pathogenesis of Lafora Disease: Transition of Soluble Glycogen to Insoluble Polyglucosan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, S.; Delgado-Escueta, A.V.; Sakamoto, T.; Avila, M.R.; Machado-Salas, J.; Hoshii, Y.; Akagi, T.; Gomi, H.; Suzuki, T.; Amano, K.; et al. Targeted disruption of the Epm2a gene causes formation of Lafora inclusion bodies, neurodegeneration, ataxia, myoclonus epilepsy and impaired behavioral response in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criado, O.; Aguado, C.; Gayarre, J.; Duran-Trio, L.; Garcia-Cabrero, A.M.; Vernia, S.; San Millán, B.; Heredia, M.; Romá-Mateo, C.; Mouron, S.; et al. Lafora bodies and neurological defects in malin-deficient mice correlate with impaired autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabrero, A.M.; Marinas, A.; Guerrero, R.; de Córdoba, S.R.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sánchez, M.P. Laforin and malin deletions in mice produce similar neurologic impairments. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Cabrero, A.M.; Sánchez-Elexpuru, G.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sánchez, M.P. Enhanced sensitivity of laforin- and malin-deficient mice to the convulsant agent pentylenetetrazole. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Myers, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X.; Fenyk-Melody, J.; Wu, M.; Ventre, J.; Doebber, T.; Fujii, N.; et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, A.; Payá, M.; García-Cabrero, A.M.; Ballester, M.I.; Heredia, M.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sánchez, M.P.; Sanz, P. Pharmacological Interventions to Ameliorate Neuropathological Symptoms in a Mouse Model of Lafora Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, D.F.; Machío-Castello, M.; Iglesias-Cabeza, N.; Giráldez, B.G.; González-Fernández, J.; Sánchez-Martín, G.; Sánchez, M.P.; Serratosa, J.M. Early Treatment with Metformin Improves Neurological Outcomes in Lafora Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Elexpuru, G.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sanz, P.; Sánchez, M.P. 4-Phenylbutyric acid and metformin decrease sensitivity to pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in a malin knockout model of Lafora disease. Neuroreport 2017, 28, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisulli, F.; Muccioli, L.; d’Orsi, G.; Canafoglia, L.; Freri, E.; Licchetta, L.; Mostacci, B.; Riguzzi, P.; Pondrelli, F.; Avolio, C.; et al. Treatment with metformin in twelve patients with Lafora disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Elexpuru, G.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sánchez, M.P. Sodium selenate treatment improves symptoms and seizure susceptibility in a malin-deficient mouse model of Lafora disease. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, G.L.; Simmons, Z.R.; Klier, J.E.; Rondon, A.; Hodges, B.L.; Shaffer, R.; Aziz, N.M.; McKnight, T.R.; Pauly, J.R.; Armstrong, D.D.; et al. Central Nervous System Delivery and Biodistribution Analysis of an Antibody-Enzyme Fusion for the Treatment of Lafora Disease. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3791–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.K.; Uittenbogaard, A.; Austin, G.L.; Segvich, D.M.; DePaoli-Roach, A.; Roach, P.J.; McCarthy, J.J.; Simmons, Z.R.; Brandon, J.A.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Targeting Pathogenic Lafora Bodies in Lafora Disease Using an Antibody-Enzyme Fusion. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 689–705.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, S.; Nitschke, S.; Grossman, T.R.; Kordasiewicz, H.; Wang, P.; Zhao, X.; Guisso, D.R.; Kasiri, S.; Nitschke, F.; Minassian, B.A. Gys1 antisense therapy rescues neuropathological bases of murine Lafora disease. Brain 2021, 144, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, K.J.; Fitzsimmons, B.; Bruntz, R.C.; Markussen, K.H.; Young, L.E.A.; Clarke, H.A.; Coburn, P.T.; Griffith, L.E.; Sanders, W.; Klier, J.; et al. Gys1 Antisense Therapy Prevents Disease-Driving Aggregates and Epileptiform Discharges in a Lafora Disease Mouse Model. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1808–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafra-Puerta, L.; Colpaert, M.; Iglesias-Cabeza, N.; Burgos, D.F.; Sánchez-Martín, G.; Gentry, M.S.; Sánchez, M.P.; Serratosa, J.M. Effect of intracerebroventricular administration of alglucosidase alfa in two mouse models of Lafora disease: Relevance for clinical practice. Epilepsy Res. 2024, 200, 107317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollá, B.; Heredia, M.; Sanz, P. Modulators of Neuroinflammation Have a Beneficial Effect in a Lafora Disease Mouse Model. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 2508–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Puerta, L.; Iglesias-Cabeza, N.; Burgos, D.F.; Sciaccaluga, M.; González-Fernández, J.; Bellingacci, L.; Canonichesi, J.; Sánchez-Martín, G.; Costa, C.; Sánchez, M.P.; et al. Gene therapy for Lafora disease in the Epm2a−/− mouse model. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 2130–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahuerta, M.; Gonzalez, D.; Aguado, C.; Fathinajafabadi, A.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Moreno-Estellés, M.; Romá-Mateo, C.; Knecht, E.; Pallardó, F.V.; Sanz, P. Reactive Glia-Derived Neuroinflammation: A Novel Hallmark in Lafora Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy That Progresses with Age. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 1607–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, T.; Viana, R.; Moreno-Estellés, M.; Campos-Rodríguez, Á.; Sanz, P. TNF and IL6/Jak2 signaling pathways are the main contributors of the glia-derived neuroinflammation present in Lafora disease, a fatal form of progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 176, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varea, O.; Guinovart, J.J.; Duran, J. Malin restoration as proof of concept for gene therapy for Lafora disease. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.; Wang, P.; Girard, J.M.; Ruggieri, A.; Wang, T.J.; Draginov, A.G.; Kameka, A.P.; Pencea, N.; Zhao, X.; Ackerley, C.A.; et al. Glycogen hyperphosphorylation underlies lafora body formation. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.M.; Ackerley, C.A.; Lohi, H.; Ianzano, L.; Cortez, M.A.; Shannon, P.; Scherer, S.W.; Minassian, B.A. Laforin preferentially binds the neurotoxic starch-like polyglucosans, which form in its absence in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Puerta, L.; Iglesias-Cabeza, N.; Sciaccaluga, M.; Bellingacci, L.; Canonichesi, J.; Sánchez-Martín, G.; Costa, C.; Sánchez, M.P.; Serratosa, J.M. Advances in gene therapy for Lafora disease: Intravenous recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of EPM2A and EPM2B genes. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, J.; Hervera, A.; Markussen, K.H.; Varea, O.; López-Soldado, I.; Sun, R.C.; Del Río, J.A.; Gentry, M.S.; Guinovart, J.J. Astrocytic glycogen accumulation drives the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration in Lafora disease. Brain 2021, 144, 2349–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, I.; Viana, R.; Sanz, P.; Ferrer, I. Inflammation in Lafora Disease: Evolution with Disease Progression in Laforin and Malin Knock-out Mouse Models. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romá-Mateo, C.; Lorente-Pozo, S.; Márquez-Thibaut, L.; Moreno-Estellés, M.; Garcés, C.; González, D.; Lahuerta, M.; Aguado, C.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Sanz, P.; et al. Age-Related microRNA Overexpression in Lafora Disease Male Mice Provides Links between Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gimeno, M.A.; Knecht, E.; Sanz, P. Lafora Disease: A Ubiquitination-Related Pathology. Cells 2018, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Song, D.; Xue, Z.; Gu, L.; Hertz, L.; Peng, L. Requirement of glycogenolysis for uptake of increased extracellular K+ in astrocytes: Potential implications for K+ homeostasis and glycogen usage in brain. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNuzzo, M.; Mangia, S.; Maraviglia, B.; Giove, F. Does abnormal glycogen structure contribute to increased susceptibility to seizures in epilepsy? Metab. Brain Dis. 2015, 30, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.; DePaoli-Roach, A.A.; Zhao, X.; Cortez, M.A.; Pencea, N.; Tiberia, E.; Piliguian, M.; Roach, P.J.; Wang, P.; Ackerley, C.A.; et al. PTG depletion removes Lafora bodies and rescues the fatal epilepsy of Lafora disease. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.; Epp, J.R.; Goldsmith, D.; Zhao, X.; Pencea, N.; Wang, P.; Frankland, P.W.; Ackerley, C.A.; Minassian, B.A. PTG protein depletion rescues malin-deficient Lafora disease in mouse. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedra, J.; Ontiveros, M.; Miravet, S.; Penalva, C.; Monfar, M.; Chillon, M. Development of a rapid, robust, and universal picogreen-based method to titer adeno-associated vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2015, 26, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, D.F.; Sciaccaluga, M.; Worby, C.A.; Zafra-Puerta, L.; Iglesias-Cabeza, N.; Sánchez-Martín, G.; Prontera, P.; Costa, C.; Serratosa, J.M.; Sánchez, M.P. Epm2aR240X knock-in mice present earlier cognitive decline and more epileptic activity than Epm2a−/− mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 181, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).