Impact of Rotational Atherectomy on Endothelial Integrity and Platelet Activation

Abstract

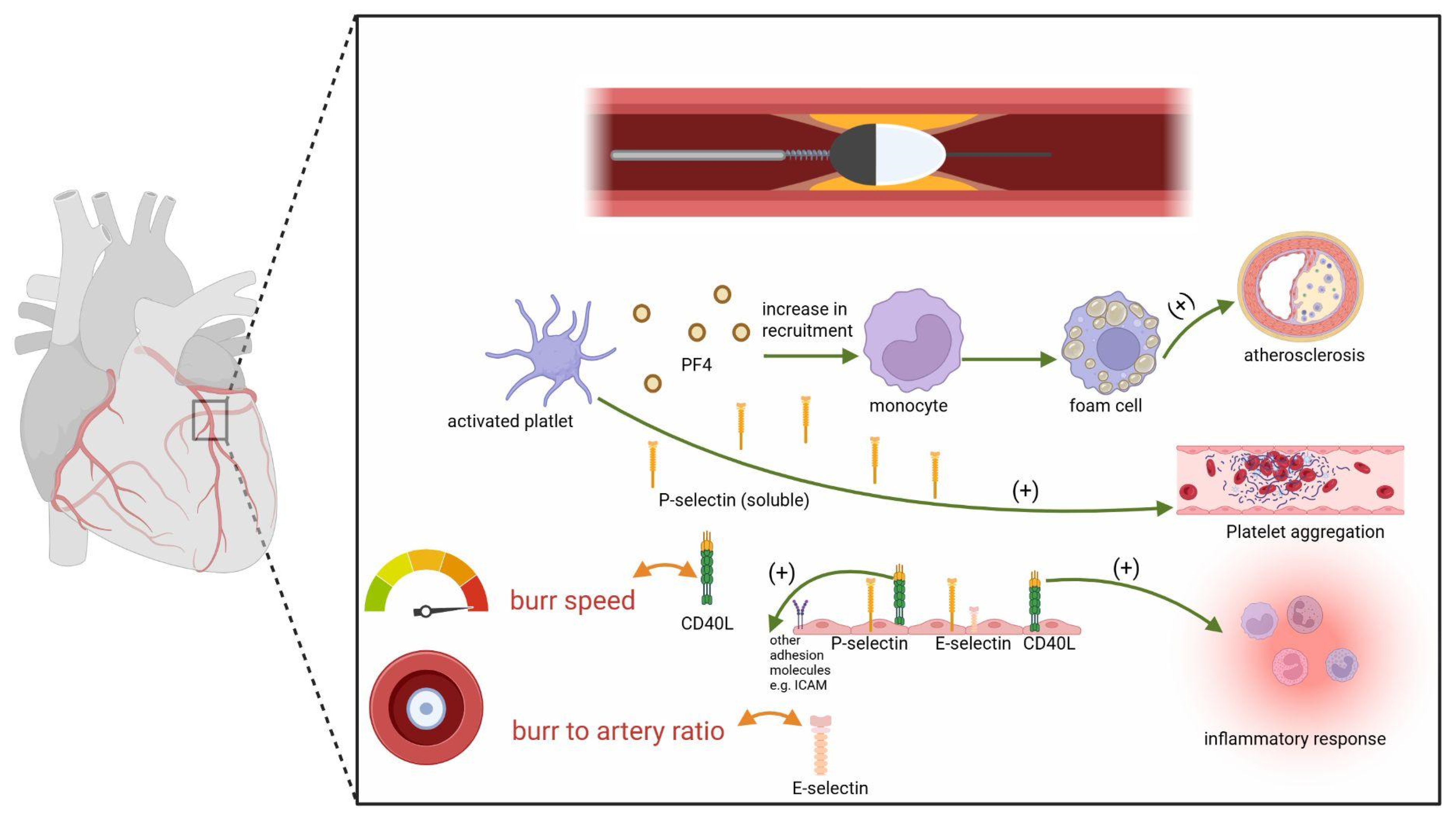

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

2.2. Endothelial and Platelet Markers Response to the Procedure

2.3. Correlations Between Procedural Characteristics and Biomarkers Changes

2.4. Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Clinical Assessment

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Biomarkers

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J.R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzon, J.F.; Otsuka, F.; Virmani, R.; Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1852–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, A.; Gawandalkar, U.U.; Kini, G.; Buradi, A.; Araki, T.; Ikeda, N.; Nicolaides, A.; Laird, J.R.; Saba, L.; Suri, J.S. Numerical analysis of the effect of turbulence transition on the hemodynamic parameters in human coronary arteries. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2016, 6, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, I.A.; Baek, K.I.; Kim, Y.; Park, C.; Jo, H. Flow-induced reprogramming of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M.E.; Gupta, R.M. The role of endothelial cells in atherosclerosis: Insights from genetic association studies. Am. J. Pathol. 2024, 194, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzell, J.; Kereiakes, D.J. Calcified plaque modification during percutaneous coronary revascularization. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 88, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Najam, O.; Bhindi, R.; De Silva, K. Calcium Modification Techniques in Complex Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e009870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuichi, S.; Sangiorgi, G.M.; Godino, C.; Airoldi, F.; Montorfano, M.; Chieffo, A.; Michev, I.; Carlino, M.; Colombo, A. Rotational atherectomy followed by drug-eluting stent implantation in calcified coronary lesions. EuroIntervention 2009, 5, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimoch, W.; Kübler, P.; Kosowski, M.; Rakotoarison, O.; Telichowski, A.; Kuliczkowski, W.; Reczuch, K. Novel procedural risk factors for myocardial injury following percutaneous coronary interventions with rotational atherectomy. Kardiol. Pol. 2023, 81, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, P.; De Belder, A.; Leitão-Marques, A. Rotational atherectomy: Technical update. Rev. Port. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2015, 34, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiacapra, F.; Bartunek, J.; Bijnens, N.; Peace, A.J.; Dierickx, K.; Bailleul, E.; DI Serafino, L.; Pyxaras, S.A.; Fraeyman, A.; Meeus, P.; et al. Periprocedural variations of platelet reactivity during elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 10, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huilcaman, R.; Venturini, W.; Fuenzalida, L.; Cayo, A.; Segovia, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Brown, N.; Moore-Carrasco, R. Platelets, a key cell in inflammation and atherosclerosis progression. Cells 2022, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bańka, P.; Czepczor, K.; Podolski, M.; Kosowska, A.; Garczorz, W.; Francuz, T.; Wybraniec, M.; Mizia-Stec, K. Platelet-related biomarkers and efficacy of antiplatelet therapy in patients with aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonbeck, U.; Libby, P. Cd40 signaling and plaque instability. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.W.; Zhang, P.; Deng, B.-Q.; Ding, S.; Wang, Z.-K.; Wu, T.; Wang, J. CD40 ligand as a potential biomarker for atherosclerotic instability. Neurol. Res. 2013, 35, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognasse, F.; Duchez, A.C.; Audoux, E.; Ebermeyer, T.; Arthaud, C.A.; Prier, A.; Eyraud, M.A.; Mismetti, P.; Garraud, O.; Bertoletti, L.; et al. Platelets as key factors in inflammation: Focus on cd40l/cd40. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 825892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krychtiuk, K.A.; Bräu, K.; Schauer, S.; Sator, A.; Galli, L.; Baierl, A.; Hengstenberg, C.; Gangl, C.; Lang, I.M.; Roth, C.; et al. Association of periprocedural inflammatory activation with increased risk for early coronary stent thrombosis. JAHA 2024, 13, e032300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, F.; Angiolillo, D.J. Targeting p-selectin during coronary interventions. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2056–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Hansson, G.K. Inflammation and immunity in diseases of the arterial tree: Players and layers. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Liao, Y. Targeting IL-1B in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 589654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habets, K.L.; Trouw, L.A.; Levarht, E.N.; Korporaal, S.J.; Habets, P.A.; de Groot, P.; Huizinga, T.W.; Toes, R.E. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies contribute to platelet activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.Z.; To, J.L.; Hughes, M.R.; McNagny, K.M.; Kim, H. Platelet signaling at the nexus of innate immunity and rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 13, 977828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoutzani, L.; Rahimi, S.Y. The History of Neurosurgical Management of Ischemic Stroke; IntechOpen eBooks: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.D.; Frenette, P.S. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood 2008, 111, 5271–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, E.; Ley, K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2292–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, E.; Carrié, D.; Dardas, P.; Fajadet, J.; Gaul, G.; Haude, M.; Khashaba, A.; Koch, K.; Meyer-Gessner, M.; Palazuelos, J.; et al. European expert consensus on rotational atherectomy. EuroIntervention 2015, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Tomey, M.I.; Teirstein, P.S.; Kini, A.S.; Reitman, A.B.; Lee, A.C.; Généreux, P.; Chambers, J.W.; Grines, C.L.; Himmelstein, S.I.; et al. North american expert review of rotational atherectomy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankovic, G.; Milasinovic, D. Rotational atherectomy in clinical practice: The art of tightrope walking. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, e004571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Age | 71 ± 8.87 |

| Gender(M) | 73.81% |

| Diabetes | 61.9% |

| Hypertension | 92.86% |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 42.86% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21.43% |

| Heart failure | 45.24% |

| Prior PCI | 80.95% |

| Prior CABG | 11.9% |

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Contrast volume, mL, mean (SD) | 218.21 (51.36) |

| Total number of passages, mean (SD) | 5.98 (4.18) |

| Total drilling time, seconds, mean (SD) | 160.71 (133.77) |

| Mean burr speed, RPM, mean (SD) | 145,980 (4980) |

| Total stent length, mm, mean (SD) | 27.59 (16.18) |

| Burr-to-artery ratio, mean (SD) | 0.46 (0.08) |

| Medication | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| ASA | 100% | |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 100% | |

| ticagrelor: 9.52% | clopidogrel: 90.48% | |

| Beta-blocker | 95.24% | |

| ACEI | 80.95% | |

| ARB | 11.90% | |

| Diuretic | 61.90% | |

| Statin | 97.62% | |

| Nitrate p.o. | 14.29% | |

| Anticoagulant p.o. | 21.43% | |

| IPP p.o. | 66.67% | |

| Variable | Before the Procedure | After the Procedure | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-selectin | 47.04 (37.32; 73.97) | 68.91 ± 26.48 | p < 0.001 |

| CD40L | 1712.22 (363.90; 3363.94) | 3602 ± 2428.71 | 0.01 |

| PF-4 | 4734.45 (1437.75; 8151.30) | 10,877.55 ± 4979.72 | p < 0.001 |

| ICAM-1 | 231.27 (205.41; 286.10) | 223.40 (202.16; 296.74) | 0.51 |

| E-selectin | 27.31 (22.62; 37.66) | 29.92 ± 14.71 | 0.57 |

| ΔP-Selectin | ΔCD40L | ΔPF-4 | ΔICAM-1 | ΔE-Selectin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of passages | r = 0.0015 p = 0.9922 | r = −0.0976 p = 0.5386 | r = −0.1070 p = 0.5001 | r = −0.0484 p = 0.7607 | r = −0.0323 p = 0.8391 |

| Total drilling time | r = −0.0573 p = 0.7185 | r = −0.1772 p = 0.2617 | r = −0.1684 p = 0.2864 | r = −0.0006 p = 0.9967 | r = 0.0002 p = 0.9992 |

| Mean burr speed | r = 0.1214 p = 0.4440 | r = 0.3437 p = 0.0258 | r = 0.1676 p = 0.2888 | r = −0.0793 p = 0.6179 | r = 0.0317 p = 0.8420 |

| Total stent length | r = 0.1362 p = 0.3958 | r = 0.0649 p = 0.6868 | r = 0.1221 p = 0.4468 | r = −0.1469 p = 0.3596 | r = 0.1703 p = 0.2872 |

| Burr-to-artery ratio | r = 0.1087 p = 0.5102 | r = 0.1327 p = 0.4206 | r = 0.1005 p = 0.5426 | r = 0.2347 p = 0.1504 | r = 0.3886 p = 0.0145 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zimoch, W.; Florek, K.; Błaszkiewicz, M.; Buzun, W.H.; Glińska, J.; Zalewska, Z.; Radek, K.; Kasztura, M.; Jankowska, E.A.; Reczuch, K. Impact of Rotational Atherectomy on Endothelial Integrity and Platelet Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411932

Zimoch W, Florek K, Błaszkiewicz M, Buzun WH, Glińska J, Zalewska Z, Radek K, Kasztura M, Jankowska EA, Reczuch K. Impact of Rotational Atherectomy on Endothelial Integrity and Platelet Activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411932

Chicago/Turabian StyleZimoch, Wojciech, Kamila Florek, Michał Błaszkiewicz, Wiktoria Hanna Buzun, Julia Glińska, Zuzanna Zalewska, Karolina Radek, Monika Kasztura, Ewa Anita Jankowska, and Krzysztof Reczuch. 2025. "Impact of Rotational Atherectomy on Endothelial Integrity and Platelet Activation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411932

APA StyleZimoch, W., Florek, K., Błaszkiewicz, M., Buzun, W. H., Glińska, J., Zalewska, Z., Radek, K., Kasztura, M., Jankowska, E. A., & Reczuch, K. (2025). Impact of Rotational Atherectomy on Endothelial Integrity and Platelet Activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411932