Abstract

Cellular senescence and oxidative stress constitute an interdependent axis that underlies cardiac pathophysiology. Cellular senescence, defined as durable proliferative arrest, is initiated and sustained by redox imbalance, whereas mitochondrial reactive oxygen species function as signaling molecules or mediators of injury. In the heart, cellular senescence and oxidative stress influence remodeling and dysfunction across diseases, including ischemia–reperfusion injury, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, dilated cardiomyopathy, and cardiac hypertrophy. Accordingly, delineating stress adaptation in cellular senescence is essential for elucidating oxidative stress-related pathogenesis. In this review, we attempt to provide an overview of the fundamental mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence in response to oxidative stress and redox signaling in disease. In addition, we integrate experimental and clinical evidence and delineate implications for mechanism-informed prevention and therapy.

1. Introduction

Cellular senescence denotes a durable state of proliferative arrest accompanied by sustained viability and active metabolism [1,2]. First described in 1961 in normal human fibroblasts, senescent cells elucidate a characteristic secretory program [3], the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which comprises cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, matrix-remodeling enzymes, and other mediators that act via autocrine and paracrine signaling [4,5]. The biological consequences of cellular senescence are largely determined by cell type, the tissue microenvironment surroundings, and the duration of senescent-cell persistence. In the heart, sustained oxidative stress induces cellular senescence and SASP in endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, and fibroblasts, which in turn aggravates oxidative injury and inflammation, ultimately leading to vascular dysfunction, maladaptive cardiac remodeling, and the progression of cardiac diseases [6,7,8]. Senescence is induced by multiple upstream stressors, including telomere shortening, oncogenic activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and maladaptive redox signaling [2,9,10,11]. Among these factors, oxidative stress is predominant driver. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage DNA, proteins, and lipids and are thus recognized as contributors to senescence [12,13]. Sustained ROS alters adaptive signaling toward chronic tissue injury [14].

In the heart, cellular senescence represents a key pathobiological mechanism [15,16]. Cellular senescence is accompanied by DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, which drive the development and progression of cardiac disease [17,18]. This review synthesizes current concepts and mechanisms of senescence and oxidative stress in cardiac diseases, outlines their manifestations across major clinical phenotypes, and directly informs the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies.

2. Biological Pathway of Senescence and Oxidative Stress

2.1. Mechanisms of the Senescence Pathway

Cellular senescence is a stable program of growth arrest accompanied by a persistent SASP. Senescence is a conserved cellular response to DNA damage [19], telomere dysfunction [20], oncogenic activation [21], proteostasis collapse [22], and oxidative stress [23]. In response to these cellular stresses in diverse tissues, the canonical DNA damage response (DDR) activates ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) proteins, which phosphorylate checkpoint kinases 1 and 2 (CHK1/CHK2) and promote tumor protein P53 (p53) stabilization with the induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21/CDKN1A) [24,25,26]. In addition, stress- and chromatin-mediated pathways promote cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16/CDKN2A) and the retinoblastoma protein (RB)-dependent suppression of E2 promoter-binding factor (E2F)-driven transcription [27,28]. At the cell-cycle checkpoint levels, the p53/p21 and p16/RB enhance cell-cycle arrest through inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases 2, 4, and 6 (CDK2/4/6), maintaining RB in a hypophosphorylated state and preventing transition to S-phase [29,30,31]. The predominance of p16/RB is associated with stable G1 arrest, whereas p53/p21 supports G1 or G2 arrest, depending on stress type, intensity, and cell state [32,33,34]. Downstream of CDK suppression, the dimerization partner (DP), RB-like (RBL1/p107, RBL2/p130), E2F, and MuvB (DREAM) complex assembles to silence a broad mitotic gene program and acts as a key effector of arrest, independent of canonical E2F regulation [35,36,37]. RB-linked circuitry further cooperates with anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and APC/C co-activator CDC20 homolog 1 (CDH1) to restrain mitotic cyclins, establishing a second layer that prevents cell-cycle re-entry [38,39,40,41]. The balance between the p53/p21 and the p16/RB axes modulates cell-fate decisions toward apoptosis, adaptive quiescence, or a stable senescent state. Resistance to apoptosis is a characteristic of senescence. Apoptosis is maintained by B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family prosurvival proteins and reprogrammed stress-response signaling [42,43,44]. Senescence is generally stable but not irreversible. Under specific conditions, including mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibition with rapamycin [45], Janus kinase 1 and 2 (JAK1/2) blockade [46], bromodomain and extraterminal (BET)-bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) inhibition [47], p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) to MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) pathway inhibition [27], or blockade of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway [48], secretory metabolites [49,50] are reduced without loss of cell-cycle arrest.

Telomere dysfunction is a canonical trigger of senescent arrest [20]. Replication-driven telomere shortening exposes chromosome ends and triggers persistent DNA-damage signaling at telomeric foci that resemble one-ended double-strand breaks [20,51]. Telomere-associated DNA damage foci are structurally stable lesions that evade efficient repair and sustain checkpoint signaling [52]. Senescent cells accumulate DNA segments with chromatin alterations, reinforcing senescence (DNA-SCARS) marked by γH2AX and 53BP1 [53]. DNA-SCARS exhibit minimal recruitment of late repair factors, indicating attenuated homologous recombination and increased reliance on end joining [52,53]. Replication stress and R-loop stabilization lead to replication-fork collapse and the formation of persistent DNA damage foci [52]. In addition to telomere dysfunction, oncogene activation triggers replication stress and nucleotide imbalance, which activate the DNA-damage response and establish senescent arrest [54]. Loss of tumor suppressor function promotes senescent arrest via dysregulated growth-factor signaling and metabolic reprogramming [55,56,57]. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling promotes p53/p21-mediated senescent arrest, reflecting diverse upstream regulation [58]. Mitogenic hyperactivation elevates nucleotide demand and promotes transcription–replication conflicts, sustaining checkpoint signaling despite limited detectable double-stranded breaks [59,60,61].

SASP is initiated by nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), p38 MAPK signaling, and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ), subsequently requiring chromatin-dependent gene expression involving bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) and EP300 [47,62]. The core secretory module encompasses interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), alongside matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and associated regulatory factors [63,64,65]. However, the precise composition of the SASP is highly heterogeneous and depends on the cell type and the specific senescence-inducing stimulus. For instance, senescent fibroblasts tend to secrete extracellular matrix (ECM)-remodeling enzymes, whereas senescent cardiomyocytes often release specific growth factors and matricellular proteins. Cell enlargement and cytoskeletal remodeling facilitate the nuclear translocation of GATA4 and NF-κB. The autophagic control of GATA4 connects lysosome function to secretory intensity [50]. Translational and post-transcriptional control acts through mTORC1, the p38-to-MK2 pathway, and AU-rich element-binding proteins that determine messenger RNA (mRNA) stability [4,66]. Notch signaling mediates secondary senescence via juxtacrine signaling [49,67]. Early IL-1-primed SASP is distinct from a later chromatin-licensed SASP [66]. Cells shift between an inflammatory- and TGF-β-dominant state as conditions change [49]. MK2-dependent phosphorylation of RNA-binding proteins stabilizes AU-rich SASP transcripts, maintaining secretion despite upstream variability [68].

Large-scale epigenetic remodeling stabilizes senescence through heterochromatin redistribution and altered enhancer activity at inflammatory genes. Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHFs) are compact nuclear domains enriched in repressive chromatin marks, such as histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3), and architectural proteins, such as heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) and macroH2A [69,70,71]. SAHF formation depends on cell type and trigger and is prominent in oncogene-induced senescence. Loss of nuclear lamina integrity promotes micronuclei formation and the release of chromatin fragments into the cytosol [72]. Reduced lamin-B1 (LMNB1), together with loss of high-mobility group box 2 (HMGB2), accompanies nuclear reorganization and reduces chromatin boundaries around inflammatory genes [73,74]. Cytosolic DNA activates cGAS-STING signaling. The resulting signaling induces type I interferon (IFN) and NF-κB signaling that sustains the secretory phenotype and promotes immune cell infiltration [75]. The reactivation of retroelements generates double-stranded RNA that activates innate RNA sensors such as retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation-associated gene-5 (MDA-5), and Toll-like receptor-3 (TLR-3). The activation of these sensors enhances IFN and stabilizes SASP [76,77,78]. DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility change in partly conserved patterns quantified by DNA methylation clocks [79]. Together, these chromatin and nucleic acid-sensing pathways sustain the persistence of cellular senescence and its paracrine effect.

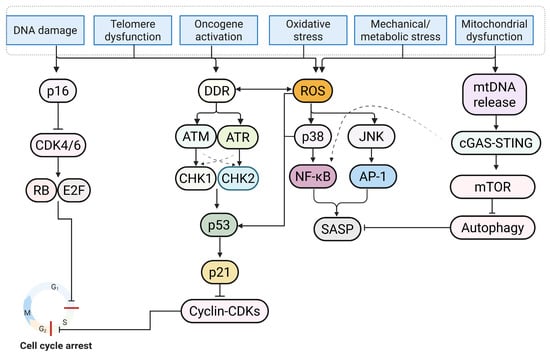

Organelle quality control provides a mechanistic basis for canonical markers of cellular senescence [80]. Lysosomal enlargement with increased senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal) and lipofuscin accumulation is characteristic of senescence [81,82]. Autophagic flux is bidirectionally linked with cellular senescence [83]. Impairment of autophagy promotes the accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles, whereas induction of autophagy attenuates the SASP [84]. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the integrated stress response modulate translation via the phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 alpha (eIF2α) and reprogram amino acid and lipid metabolism with a state of cell-cycle arrest [85,86]. There is no single definitive marker. Diagnostic marker combinations integrating SA-β-gal with p16 or p21, loss of LMNB1, telomere-associated damage foci, heterochromatin features, and SASP profiling are best implemented using a single-cell or spatial assay to reduce classification errors [2,87]. To circumvent the inherent limitations of invasive tissue sampling, contemporary research has pivoted toward non-invasive detection modalities to enhance clinical applicability. Liquid biopsy strategies, encompassing the quantification of senescence-associated extracellular vesicles (SA-EVs) and circulating analytes such as growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), constitute a scalable paradigm for longitudinal patient surveillance. Concurrently, advancements in molecular imaging, particularly positron emission tomography (PET) utilizing radiotracers specific to senescence-associated enzymes, facilitate the in vivo spatiotemporal quantification of cardiac senescence accumulation [88,89,90,91]. An overview of the senescence-associated cell-cycle arrest pathway is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Senescence is triggered by diverse upstream stressors, including DNA damage, telomere dysfunction, oncogene activation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial or metabolic dysfunction. These heterogeneous insults trigger the DNA damage response (DDR). Within this signaling cascade, ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) kinases display reciprocal regulation and phosphorylate checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) and checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1), respectively, resulting in tumor protein p53 (p53) stabilization and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) induction. Upon activation, p21 suppresses cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes, thereby establishing dual blockade at both the G1/S and G2/M checkpoints (indicated by red bars). Concomitantly, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16) axis inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6), maintaining retinoblastoma protein (RB) in a hypophosphorylated state and silencing E2 promoter-binding factor (E2F)-dependent transcription to consolidate G1/S arrest. Independent of cell-cycle control, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and metabolic cues stimulate the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK)/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. mTOR drives senescence by suppressing autophagy, while p38 MAPK/JNK signaling activates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) to orchestrate the expression of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Furthermore, the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway, triggered by cytosolic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), exacerbates inflammatory signaling. In concert, these signaling nodes dictate stable growth arrest and the secretory phenotype (Figure created in Biorender. Hyeong Rok Yun. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/canvas-beta/6911a5a2ecdb3e3f73bc83cf).

2.2. Molecular Biology of Oxidative Stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen (O2)-containing molecules with high chemical reactivity. Most cellular oxygen is fully reduced to water via mitochondrial electron transport (mETC), and only a small cellular oxygen is diverted to ROS through electron leakage [92]. During oxidative phosphorylation, complexes I and III generate superoxide (O2•−), which is converted by superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 (SOD1/2) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [93,94]. In the presence of ferrous iron, H2O2 participates in Fenton chemistry, producing hydroxyl radical (HO•), an extremely reactive species that damages lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [95]. Lipid peroxidation is a chain reaction that initiates as HO• removes a bis-allylic hydrogen from a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) to form a carbon-centered radical (R•) [96]. Molecular O2 produces a lipid peroxyl radical (ROO•), which propagates the reaction and gives rise to lipid hydroperoxides (ROOH) [97]. Glutathione peroxidase-4 (GPx4) reduces ROOH to the corresponding alcohol (ROH) using glutathione, thereby limiting membrane damage and cytotoxicity [98]. NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) serves as a major non-mitochondrial source of ROS in innate immune cells. Upon microbial stimulation, NOX2 transfers electrons from NADPH to O2, generating O2•− within the phagosomal lumen or extracellular space [99]. SODs subsequently convert the resulting O2•− flux into H2O2, at which point myeloperoxidase then reacts with chloride to generate hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [100]. Oxidants are essential for pathogen killing, but excessive production injures host tissues. Other enzymes, including DUOX1/2, xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450s, monoamine oxidases, and nitric oxide synthases (NOSs), produce ROS or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in distinct subcellular locations [101,102]. O2•− reacts rapidly with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [103]. To limit oxidative stress, cells rely on enzyme-based and small-molecule antioxidant defenses. Core enzymes include SOD, catalase, glutathione peroxidases (GPxs), glutathione reductase (GR), peroxiredoxins (Prxs), and the thioredoxin (Trx) system [104,105]. Non-enzymatic antioxidants include reduced glutathione (GSH), ascorbate, tocopherols, urate, and carotenoids, while metal-binding proteins such as transferrin, ferritin, ceruloplasmin, and albumin restrict iron and copper availability and thereby suppress Fenton reactions [105,106]. At the transcriptional level, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) pathway is a major regulator of the antioxidant defense system. Under normal conditions, Keap1 with cullin 3 (Cul3) targets NRF2 for proteasomal degradation, whereas oxidative stress stabilizes NRF2, promotes nuclear translocation, and activates antioxidant response element programs that upregulate heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1), NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), SOD and Gpxs, ferritin, Trx, and related detoxifying systems [107,108,109].

2.3. Interplay Between Cellular Senescence and Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress has been implicated as a primary trigger of cellular senescence. Excess ROS leads to DNA damage and a sustained DDR, which activates p53/p21 and p16/RB [110,111]. In parallel, redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as NF-κB and C/EBPβ, are activated and amplify SASP [62,112,113]. However, it is not yet clear whether the antioxidant defense program represents a nonspecific response to increased oxidant or a ROS-dependent response. Nevertheless, cellular senescence is accompanied by the upregulation of antioxidant defense genes [18,114,115]. Moreover, mitochondria in the senescent cells typically exhibit decreased mitochondrial respiratory capacity and membrane potential (ΔΨm), accompanied by increased ROS production [113,116]. Excess dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) activity with decreased mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1/2) and optic atrophy protein (OPA1) leads to cristae destabilization, elevated ROS, and reduced respiratory capacity [117,118,119]. Senescence-associated mitochondrial dysfunction (SAMD) is characterized by primary organelle injury with oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) depletion and reduced sirtuin (SIRT) activity, accompanied by reprogrammed SASP [18,120,121]. SAMD can be driven by persistent DDR through pathways including p38 MAPK, TGF-β, and Nf-κB signaling, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation, loss of ΔΨm, and impaired complex I and II respiration [27,112,122]. In addition, the dysregulated opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) has been implicated as a key effector that links mitochondrial calcium (Ca2⁺) overload and oxidative stress to SAMD. In the cardiac system, maladaptive mPTP opening promotes loss of ΔΨm, ATP depletion, and cardiomyocyte death in models of ischemia–reperfusion injury and chronic remodeling, suggesting that mPTP activity may provide an opportunity to selectively target senescent cardiac cells [123,124,125,126].

Early mitochondrial injury triggers mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) efflux into the cytosol, activating cGAS-STING and NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to increased SASP and ROS production. Mitophagy reduction, such as PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin, impairs the clearance of damaged mitochondria, while chronic activation of poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) in response to DNA damage depletes NAD+ and further compromises respiratory reserve capacity [127,128,129,130]. NAD homeostasis is additionally eroded by ecto- and endo-enzymes such as CD38, and by reduced salvage through Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAMPT), linking damage signaling to sirtuin-dependent chromatin regulation [131]. Beyond mitophagy, selective autophagy of the endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes, and peroxisomes, together with TFEB and TFE3-driven lysosome biogenesis, shapes organelle quality and influences whether senescence remains stable or transitions toward degeneration [132,133]. A mitochondrial stress-biased program, often termed MiDAS, can produce p21-high and p16-variable arrest with a distinct secretory signature, demonstrating that not all senescence is DDR-centric [120].

3. Senescence and Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Disease

Cardiac disease is a leading global cause of death and disability. Both its prevalence and mortality increase with population aging [134]. Age is the most common independent risk factor for cardiac disease and is accompanied by impaired cardiac structure and function [135]. Rarely dividing/post-mitotic cardiomyocytes exhibit a senescence-like phenotype (reduced metabolic flexibility, Ca2+ handling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased inflammatory signaling) that contributes to age-related functional decline [18,136,137]. In addition, hemodynamic overload, ischemia–reperfusion, and metabolic dysfunction (e.g., insulin resistance and lipotoxicity) promote oxidative stress and accelerate cardiac senescence [18,138]. Although the molecular mechanism underlying oxidative stress-induced cardiac senescence is not fully understood, elevated ROS levels are a consistent feature of cardiac senescence [139,140]. In the cardiac senescent cell, mitochondrial Ca2⁺ overload triggers the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), loss of ΔΨm, and ATP depletion, while impaired PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, lysosomal deacidification, and reduced TFEB signaling delay the clearance of damaged mitochondria [141,142,143]. Consequently, mtDNA deletions and point mutations accumulate with age, while impaired mitochondrial quality control elevates ROS with positive feedback [139,144]. In these sections, we examine the mechanistic contribution of the senescence–oxidative stress axis to the pathogenesis of major cardiac diseases.

3.1. Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury

During ischemia, mETC activity is inhibited, and succinate accumulates [145]. During reperfusion, oxidation of succinate triggers reverse electron transport (RET) at complex I and causes increased mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) [146]. Subsequently, cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, opening of mPTP, loss of ΔΨm, and ATP depletion occur, thereby increasing cardiac injury [141,147]. Nevertheless, both the identification of mPTP and the proposed distinction that transient opening is physiological and sustained opening is pathological remain controversial [142]. Previous studies have reported that cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts at the infarct border zone exhibit increased p16 and p21 expression accompanied by SASP accumulation [148,149,150,151]. Importantly, these cell types exhibit distinct SASP profiles that differentially impact post-ischemic remodeling. Senescent cardiomyocytes are a primary source of CCN1 (cyr61) and pro-fibrotic factors such as TGF-β, which drive replacement fibrosis. In contrast, senescent cardiac fibroblast and endothelial cells predominantly secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and IL-1β) and MMPs, which perpetuate inflammation and degrade the extracellular matrix. Consistent with the relative resistance of senescent cells to apoptosis, experimental models indicate that senescent cardiomyocytes and non-myocytes are not efficiently eliminated during I/R, resulting in persistence and accumulation within the peri-infarct region. Genetic and pharmacological senolytic strategies that increase apoptotic susceptibility in senescent cells, such as BCL-2 family inhibition with navitoclax or combined dasatinib and quercetin, reduce senescent cell accumulation, attenuate adverse remodeling, and improve post-infarction cardiac function in aged mice, indicating that senescent cells survive the initial ischemic insult and contribute to chronic injury [152,153]. However, whether these signatures are causal drivers or downstream consequences of injury remains unclear and appears to depend on the experimental model and the assay used [154]. Recent studies indicated that lipid peroxidation-dependent ferroptosis contributes to I/R injury [155,156]. In addition, mtDNA release with the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway can exacerbate inflammation after reperfusion [157,158]. I/R-induced senescent cardiomyocyte has been linked to hypertrophy, inflammation, and fibrosis via SASP mediators, although some studies report that senescence induction in fibroblasts limits fibrosis and promote repair, suggesting dependence on cell type, timing, and experimental conditions [154,159,160]. Clinical trials of broad antioxidant supplementation have not shown consistent benefits, and low-level ROS may mediate preconditioning, indicating the importance of dose and timing [161,162,163,164,165]. More targeted strategies administered at reperfusion appear promising [166,167]. In experimental models, the administration of malonate at reperfusion to inhibit succinate oxidation attenuates injury and adverse remodeling [146,165]. In contrast, acute inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) to prevent succinate efflux has been reported to increase mtROS and exacerbate injury [168]. These findings emphasize the importance of the RET and succinate timing axis. Overall, I/R injury may be mitigated by approaches that attenuate the early increase in ROS driven by RET, prevent the sustained opening of mPTP, restore mitochondrial quality control, and preserve NAD⁺ metabolism. The modulation of ferroptosis and the cGAS/STING pathway should be guided by the prevailing phenotype. Success is likely to depend on biomarker-guided phenotyping using measures such as succinate and oxidized phospholipids, mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns derived from mtDNA, lipid peroxidation markers, and cellular senescence markers, together with precise therapeutic timing.

3.2. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a heterogeneous syndrome prevalent among older adults with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension [169,170]. Systemic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction are frequent. Endothelial oxidative stress attenuates NO/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/protein kinase G (PKG) signaling, which reduces titin phosphorylation, increases passive myocardial stiffness, and impairs diastolic relaxation [171,172]. Disruptions to redox and signaling pathways occur within a cellular environment characterized by senescence across multiple cardiac cell types [173,174]. In the coronary microvasculature, endothelial cells exhibit increased p16 and p21, loss of LMNB1, telomere-associated DNA damage foci, and SASP enriched in IL-1β, IL-6, TGF-β, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [173,175]. Consequently, SASP factors promote microvascular rarefaction, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), and interstitial remodeling [176,177]. In addition, senescent cardiac fibroblasts promote collagen deposition and cross-linking, whereas cardiomyocytes exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired mitophagy, reduced NAD⁺ and sirtuin activity, and metabolic inflexibility [178,179,180,181]. Consequently, senescence pathways interact with redox imbalance and reduced NO/cGMP/PKG signaling to enhance diastolic dysfunction [182,183]. Despite the established preliminary model, robust experimental validation for the proposed interaction has yet to be provided. Clinically, senescence signatures are heterogeneous and depend on the analytic method, tissue accessibility, and biomarker specificity [2,184]. Currently, available circulating markers remain nonspecific, while the relative contribution of vascular and extracardiac drivers remains controversial, and the causal relationship between microvascular senescence and clinical HFpEF phenotypes has not been definitively established [185,186,187]. Clinical trials that directly augmented the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway have yielded neutral or mixed results, likely reflecting heterogeneity in pathway predominance by patient phenotype, intervention timing, and comorbid state [188,189,190]. By contrast, interventions that attenuate metabolic, inflammatory, and oxidative stress have shown benefit. Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors reduce HF in preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists improve symptoms, physical function, and weight in obese phenotypes [191,192,193,194]. Senescence-targeted therapies, including senolytics and senostatics, remain experimental, with human efficacy and safety still uncertain. Taken together, HFpEF reflects an interplay among microvascular endothelial senescence with oxidative stress, reduced NO/cGMP/PKG signaling, impaired mitochondrial quality control, and metabolic dysfunction. Given that dominant mechanisms are not uniform across patients, treatment should be phenotype-based. Weight reduction combined with SGLT-2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists is appropriate in obese metabolic–inflammatory phenotypes. Approaches that enhance microvascular function and NO production are reasonable in cases characterized by predominant fibrosis. Biomarker panels and imaging of microvascular function will be essential for precise phenotyping and therapy.

3.3. Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy involves chronic oxidative stress, defective organelle quality control, and the accumulation of senescence markers in cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts [195,196,197]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, with impaired mitophagy, lysosomal deacidification, and reduced TFEB signaling, disrupts ATP homeostasis and increases ROS [198,199,200]. Proteostasis failure driven by loss-of-function variants in titin and mutations in lamin A/C (LMNA), BCL2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), and desmin (DES) produces proteotoxic and ER stress with depleted cellular NAD⁺ [201,202,203,204,205]. Nuclear envelope instability and micronuclei formation lead to cytosolic DNA release and an activated cGAS/STING pathway, sustaining inflammatory signaling and SASP, which promotes adverse remodeling, systolic dysfunction, and an arrhythmogenic substrate [75,206]. Nevertheless, senescence markers are not consistently detected in detailed cardiomyopathy patients; concurrently, antioxidant supplementation has failed to yield consistent benefits in clinical trials [2,207]. NOX isoforms may fulfill conflicting roles across varying physiological contexts, evidenced by reports of both detrimental and adaptive signaling [208,209,210,211]. The penetrance of titin-truncating variants remains unresolved, with competing attributions to haploinsufficiency, poison-peptide mechanism, and additional second hits such as viral myocarditis, pressure overload, and metabolic stress [212,213]. Although senolytic and autophagy-enhancing approaches have shown promise in preclinical studies, efficacy and safety in human dilated cardiomyopathy have not yet been demonstrated [214,215]. Overall, dilated cardiomyopathy reflects an interplay between redox imbalance, failures in organelle quality control, and stress-responsive transcriptional programs. Therapeutic development should emphasize phenotype-guided approaches that target mitochondrial function and mitophagy, stabilize proteostasis, modulate cGAS/STING signaling, and support NAD⁺ metabolism, together with guideline-directed neurohormonal blockade.

3.4. Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling

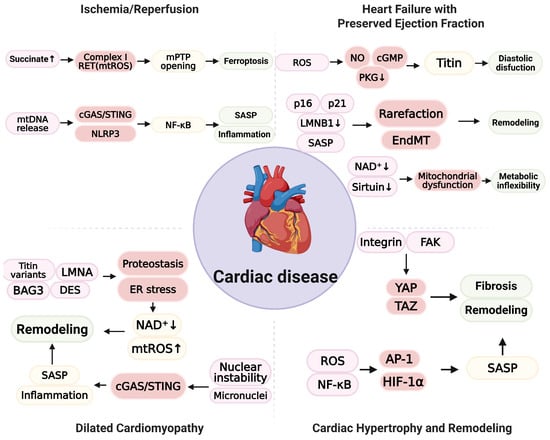

Cardiac hypertrophy is an initially adaptive response to hemodynamic or metabolic load but often progresses to maladaptive remodeling with fibrosis, microvascular rarefaction, and diastolic or systolic dysfunction [216]. Recent studies indicate that senescence-oxidative stress crosstalk is central to driving progression from adaptive hypertrophy to pathological remodeling [18,217]. Mechanical and metabolic stress increase mtROS and activate redox-sensitive transcriptional programs such as NF-κB, activating protein-1 (AP-1), and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), together with mechanotransduction pathways including integrin–focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (YAP/TAZ) [218,219,220,221]. Taz acts with the TEA domain (TEAD) to convert mechanical load into pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic gene expression [222]. Perturbed Ca2+ handling at mitochondria–ER contact sites promotes mitochondrial permeability transition, loss of ΔΨm, and energetic inefficiency [223]. Single-cell and spatial profiling reveal heterogeneous senescent states across endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes [224]. Distinct SASP profiles among these cell populations dictate a specific therapeutic target. For example, senescent cardiomyocytes secrete endothelin-1(EDN-1) and GDF15, which act in an autocrine/paracrine manner to promote hypertrophy and fibrosis, whereas senescent fibroblasts exhibit a strongly inflammatory SASP (IL-6 and CCL2) that recruits immune cells. Endothelial p16 and p21 expression with SASP enriched in adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and TGF-β promote EndMT and microvascular rarefaction [175,225]. Fibroblast populations range from proinflammatory, matrix-secreting cells to quiescent, matrifibrocyte-like states, suggesting time- and cell-type-specific contributions of senescence to remodeling [226,227]. Cytosolic mtDNA and micronuclei activate cGAS/STING and inflammasome pathways, thereby linking organelle injury to sterile inflammation and fibrotic progression [228,229]. However, several crucial mechanistic aspects have yet to be fully elucidated. Physiologically, low levels of ROS mediate adaptive signaling, complicating antioxidant strategies [230]. The consequences of YAP/TAZ signaling depend on the cellular state and timing—early after load, transient YAP/TAZ activation is protective—whereas sustained activation drives fibrotic remodeling [222,231,232]. In addition, whether senescence in cardiomyocytes or fibroblasts precedes remodeling or activates downstream consequences remains unknown, and the direction of the effect likely varies with the model, timing, and measurement endpoints [233]. Therapeutic strategies for hypertrophic remodeling should emphasize unloading and stiffness reduction, together with the selective modulation of mechanotransduction pathways [234,235]. The strategy comprises augmentation of cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG) signaling to increase titin compliance, targeting integrin–FAK and YAP/TAZ to suppress prohypertrophic/profibrotic programs, anti-fibrotic strategies that limit fibroblast activation and extracellular-matrix cross-linking, improvement in microvascular function, and isoform-specific load-dependent modulation of NOX activity [236,237,238]. Responses should be evaluated using remodeling-specific endpoints, such as left ventricular mass, extracellular volume fraction, and myocardial strain, to guide biomarker-informed, stage-specific interventions [239]. An overview of cardiac disease is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of senescence-oxidative stress coupling across cardiac disease. In ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), succinate accumulation drives complex I reverse electron transport (RET) and increases mtROS, thereby promoting the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and ferroptosis. mtDNA release activates cGAS/STING and NLRP3, initiates NF-κB signaling, and augments SASP and inflammation, contributing to injury and early remodeling. In heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), endothelial oxidative stress depresses NO/cGMP/PKG signaling, reduces titin compliance, and produces diastolic dysfunction. Endothelial p16 and p21, together with loss of LMNB1 and SASP, promote microvascular rarefaction and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), leading to interstitial remodeling. In cardiomyocytes, depletion of NAD⁺ and reduced sirtuin activity are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic inflexibility. In dilated cardiomyopathy, variants in titin, LMNA, BAG3, and DES disrupt proteostasis and induce ER stress with NAD⁺ depletion and increased mtROS. Nuclear instability and micronuclei activate cGAS/STING, amplify SASP and inflammation, and drive adverse remodeling. In cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling, mechanical or metabolic load is signaled via integrin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) to yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (YAP/TAZ) and promotes fibrosis and remodeling. ROS activate NF-κB, AP-1, and HIF-1α, increase SASP, and further contribute to remodeling. (Figure created in Biorender. Hyeong Rok Yun. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/canvas-beta/690b558c0fc19569ee5e6335).

3.5. Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital heart disease (CHD) represents a complex pathophysiological paradigm in which chronic hypoxia and hemodynamic overload accelerate biological aging through distinct molecular mechanisms [240,241]. Unlike HF in adults, the myocardium in CHD is exposed to sustained cyanosis and pressure loading from early development, leading to maladaptive metabolic reprogramming driven by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) [242,243]. While initially adaptive, chronic HIF-1α stabilization alters mitochondrial biogenetics and upregulates NOX2 and NOX4, thereby establishing a persistent source of mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS [244,245]. Under these conditions, NRF2 signaling is insufficient to yield an adequate antioxidant response, resulting in chronic redox dysfunction and exacerbated oxidative injury [246,247]. Cumulative oxidative stress directly compromises genomic stability. ROS-induced DNA double-stranded breaks activate the ATM/ATR-p53-p21 axis, initiating cell-cycle arrest, while concurrent oxidative damage to telomeres suppresses telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) activity, thereby accelerating telomere shortening in cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells [248,249]. Crucially, the transition from damage accumulation to a stable senescent state is consolidated by p16 upregulation, which correlates with ventricular dysfunction severity in patients with CHD. Senescent cells adopt SASP characterized by NF-κB-dependent secretion of IL-6, TGF-β, and MMPs, which drives EndMT and myocardial fibrosis [250]. Furthermore, perioperative I/R injury and mechanical stress from cardiopulmonary bypass invoke marked increases in mtROS and the release of mtDNA, which may trigger the cGAS/STING pathway and link metabolic stress to sterile inflammation [157,214,251]. Thus, CHD constitutes a trajectory of “accelerated cardiovascular aging” driven by the convergence of hypoxic signaling, NRF2 dysfunction, and p53/p16-mediated senescence.

3.6. Clinical Translation and Ongoing Trials Targeting the Senescence-Oxidative Stress Axis

Notwithstanding the robust preclinical evidence elucidating the therapeutic potential of the senescence-oxidative stress axis, clinical translation remains in its early stages [252]. Contemporary clinical investigations are primarily stratified into two distinct approaches: the repurposing of established pharmacotherapies with pleiotropic senomorphic properties and the evaluation of novel senolytic or mitochondria-targeted agents [17,139]. The most substantial clinical advancement has been realized with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors such as Empagliflozin and Dapagliflozin. Although initially developed as antidiabetic agents, landmark cardiovascular outcome trials have substantiated efficacy in reducing HF hospitalization and mortality across all ejection fraction ranges [192,253]. Mechanistically, these agents have been demonstrated to attenuate oxidative stress, ameliorate mitochondrial energetics, and suppress cellular senescence pathways in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, thereby effectively functioning as putative “senomorphics” in clinical practice [254,255]. Concurrently, Metformin is under active investigation for the potential to alleviate age-related cardiovascular decline via AMPK activation and ROS reduction, and the prospective TAME (Targeting Aging with Metformin) trial is anticipated to provide definitive insights [252,256]. Pharmacological strategies targeting the selective elimination of senescent cells, termed senolytics, are currently subject to evaluation in pilot clinical trials. The combination of Dasatinib and Quercetin is being assessed for safety and efficacy in pathologies exhibiting significant mechanistic overlap with adverse cardiac remodeling, including diabetic kidney disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [257]. Furthermore, the flavonoid Fisetin is under investigation in the AFFIRM-LITE trial to delineate its impact on frailty and systemic inflammation in the geriatric population [258,259]. While these agents exhibit therapeutic promise, clinical application necessitates precise dosing protocols to optimize the therapeutic window while minimizing off-target cytotoxicity. In parallel, interventions designed to directly modulate mitochondrial oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms have yielded heterogeneous outcomes. Elamipretide (SS-31), a peptide engineered to stabilize cardiolipin and reduce mtROS, has been evaluated in HF cohorts [139,141]. Although broad efficacy endpoints have shown variability, post hoc analyses suggest potential benefits in patient subgroups defined by specific mitochondrial phenotypes. Additionally, NRF2 activators such as bardoxolone methyl have demonstrated the capacity to augment antioxidant response elements in renal pathologies, although the cardiovascular safety profile necessitates vigilant monitoring due to potential fluid retention [260]. Collectively, these translational efforts underscore a paradigm shift toward precision medicine and necessitate the stratification of therapeutic interventions based on individual oxidative or senescent phenotypes.

4. Conclusions

The cellular senescence–oxidative stress axis represents an extensive pathophysiological mechanism in cardiac disease. Understanding integrated signaling pathways enables the development of target-, timing-, and phenotype-guided approaches for prevention and therapy. Recent studies focus on senolytic and senostatic strategies. In the future, advances in multi-omics (metabolomics, proteomics, and genomics) and precision biomarker development will permit precise identification and stratification of patients characterized by a predominant senescence-oxidative stress axis, enabling mechanism-informed, individualized therapy. Outstanding priorities include elucidating cell-type and temporal dependencies, establishing causal mechanisms, and undertaking adequately powered systemic human studies to define safety and efficacy.

Author Contributions

H.R.Y., M.K.S., S.H. and J.S.R. wrote and revised the manuscript. J.H., I.K., and S.S.K. conceptualized and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03025124, NRF-2022R1A1A01067626, and RS-2025-25442355).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AP-1 | Activator protein-1 |

| APC/C | Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome |

| ATM | Ataxia–telangiectasia mutated |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| ATR | ATM- and Rad3-related |

| BACH1 | BTB and CNC homology 1 |

| BAG3 | BCL2-associated athanogene 3 |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma-2 |

| BET | Bromodomain and extraterminal (family) |

| BRD4 | Bromodomain-containing protein 4 |

| C/EBPβ | CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β |

| CDH1 | APC/C co-activator CDC20 homolog 1 |

| CDK2/4/6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2/4/6 |

| CDKN1A (p21) | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| CDKN2A (p16) | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| CUL3 | Cullin 3 |

| DNA-SCARS | DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence |

| DP | Dimerization partner (of E2F) |

| DREAM | DP, RB-like, E2F, and MuvB complex |

| DRP1 | Dynamin-related protein-1 |

| DUOX1/2 | Dual oxidase 1/2 |

| E2F | E2 promoter-binding factor |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor-2 alpha |

| EndMT | Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| EP300 (p300) | E1A-binding protein p300 |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GPx4 | Glutathione peroxidase-4 |

| GPxs | Glutathione peroxidases |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| H3K9me3 | Histone H3 lysine-9 trimethylation |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha |

| HMGB2 | High-mobility group box 2 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HO• | Hydroxyl radical |

| HOCl | Hypochlorous acid |

| HP1 | Heterochromatin protein-1 |

| I/R | Ischemia–reperfusion |

| IFN | Interferon (type I unless otherwise specified) |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| JAK1/2 | Janus kinase-1/2 |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 |

| LMNA | Lamin A/C |

| LMNB1 | Lamin B1 |

| macroH2A | Macro-H2A histone variant |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MCT1 | Monocarboxylate transporter-1 |

| MDA-5 | Melanoma differentiation-associated gene-5 |

| mETC | Mitochondrial electron transport chain |

| MFN1/2 | Mitofusin-1/2 |

| MiDAS | Mitochondrial dysfunction-associated senescence |

| MK2 | MAPK-activated protein kinase-2 |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex-1 |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species |

| NAD⁺ | Oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOSs | Nitric oxide synthases |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| NOX2 | NADPH oxidase-2 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 |

| O2•− | Superoxide |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy-1 |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase-1 |

| PKG | Protein kinase-G |

| Prxs | Peroxiredoxins |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| RB | Retinoblastoma protein |

| RET | Reverse electron transport |

| RIG-I | Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROH | Lipid alcohol |

| ROO• | Lipid peroxyl radical |

| ROOH | Lipid hydroperoxide |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SA-β-gal | Senescence-associated β-galactosidase |

| SAHFs | Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

| SAMD | Senescence-associated mitochondrial dysfunction |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SGLT-2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 |

| SIRT(s) | Sirtuin(s) |

| SOD1/2 | Superoxide dismutase-1/2 |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TAZ | Transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif |

| TEAD | TEA domain transcription factor |

| TFE3 | Transcription factor E3 |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TLR-3 | Toll-like receptor-3 |

| Trx | Thioredoxin |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| ΔΨm | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

References

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Uversky, V.N.; Ren, J. Hallmarks of cellular senescence: Biology, mechanisms, regulations. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 1482–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Carlos Acosta, J.; Adams, P.D.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F.; Baker, D.J.; Bishop, C.L.; Chandra, T.; Collado, M.; Gil, J.; Gorgoulis, V.; et al. Guidelines for minimal information on cellular senescence experimentation in vivo. Cell 2024, 187, 4150–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.C.; Banito, A.; Wuestefeld, T.; Georgilis, A.; Janich, P.; Morton, J.P.; Athineos, D.; Kang, T.W.; Lasitschka, F.; Andrulis, M.; et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Yeo, H.L.; Wong, S.W.; Zhao, Y. Cellular Senescence: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppe, J.P.; Desprez, P.Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: The dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2010, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagares, D.; Santos, A.; Grasberger, P.E.; Liu, F.; Probst, C.K.; Rahimi, R.A.; Sakai, N.; Kuehl, T.; Ryan, J.; Bhola, P.; et al. Targeted apoptosis of myofibroblasts with the BH3 mimetic ABT-263 reverses established fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Espin, D.; Canamero, M.; Maraver, A.; Gomez-Lopez, G.; Contreras, J.; Murillo-Cuesta, S.; Rodriguez-Baeza, A.; Varela-Nieto, I.; Ruberte, J.; Collado, M.; et al. Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development. Cell 2013, 155, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storer, M.; Mas, A.; Robert-Moreno, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Ortells, M.C.; Di Giacomo, V.; Yosef, R.; Pilpel, N.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Sharpe, J.; et al. Senescence is a developmental mechanism that contributes to embryonic growth and patterning. Cell 2013, 155, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, M.; Ohtani, N.; Youssef, S.A.; Rodier, F.; Toussaint, W.; Mitchell, J.R.; Laberge, R.M.; Vijg, J.; Van Steeg, H.; Dolle, M.E.; et al. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev. Cell 2014, 31, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Park, J.W.; Degan, P.; Ames, B.N. Oxidative damage to DNA during aging: 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine in rat organ DNA and urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 4533–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ming, H.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Huang, C. Redox regulation: Mechanisms, biology and therapeutic targets in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atayik, M.C.; Cakatay, U. Redox signaling and modulation in ageing. Biogerontology 2023, 24, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, P.; Maurer, M.S.; Roh, J. Aging in Heart Failure: Embracing Biology Over Chronology: JACC Family Series. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, D.E.; de Lemos, J.A.; Shaw, L.J.; Reuben, D.B.; Lyubarova, R.; Peterson, E.D.; Spertus, J.A.; Zieman, S.; Salive, M.E.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Cardiovascular Biomarkers and Imaging in Older Adults: JACC Council Perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1577–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.; Rainer, P.P.; Sedej, S.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of cardiovascular ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, M.O.J. Cell senescence in cardiometabolic diseases. NPJ Aging 2024, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, A.; Meyer, M.; Bechmann, V.; Nerlich, M.; Angele, P. Oxidative stress induces senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Adda di Fagagna, F.; Reaper, P.M.; Clay-Farrace, L.; Fiegler, H.; Carr, P.; Von Zglinicki, T.; Saretzki, G.; Carter, N.P.; Jackson, S.P. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 2003, 426, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Lin, A.W.; McCurrach, M.E.; Beach, D.; Lowe, S.W. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 1997, 88, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondrogianni, N.; Stratford, F.L.; Trougakos, I.P.; Friguet, B.; Rivett, A.J.; Gonos, E.S. Central role of the proteasome in senescence and survival of human fibroblasts: Induction of a senescence-like phenotype upon its inhibition and resistance to stress upon its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 28026–28037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallage, S.; Gil, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Meets Senescence. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canman, C.E.; Lim, D.S.; Cimprich, K.A.; Taya, Y.; Tamai, K.; Sakaguchi, K.; Appella, E.; Kastan, M.B.; Siliciano, J.D. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science 1998, 281, 1677–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Piwnica-Worms, H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 4129–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Deiry, W.S.; Tokino, T.; Velculescu, V.E.; Levy, D.B.; Parsons, R.; Trent, J.M.; Lin, D.; Mercer, W.E.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 1993, 75, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, A.; Patil, C.K.; Campisi, J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracken, A.P.; Kleine-Kohlbrecher, D.; Dietrich, N.; Pasini, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Beekman, C.; Theilgaard-Monch, K.; Minucci, S.; Porse, B.T.; Marine, J.C.; et al. The Polycomb group proteins bind throughout the INK4A-ARF locus and are disassociated in senescent cells. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Hannon, G.J.; Zhang, H.; Casso, D.; Kobayashi, R.; Beach, D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature 1993, 366, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Hannon, G.J.; Beach, D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature 1993, 366, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchkovich, K.; Duffy, L.A.; Harlow, E. The retinoblastoma protein is phosphorylated during specific phases of the cell cycle. Cell 1989, 58, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelle, D.E.; Zindy, F.; Ashmun, R.A.; Sherr, C.J. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell 1995, 83, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrier-Savournin, F.B.; Chateau, M.T.; Gire, V.; Sedivy, J.; Piette, J.; Dulic, V. p21-Mediated nuclear retention of cyclin B1-Cdk1 in response to genotoxic stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 3965–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lossaint, G.; Horvat, A.; Gire, V.; Bacevic, K.; Mrouj, K.; Charrier-Savournin, F.; Georget, V.; Fisher, D.; Dulic, V. Reciprocal regulation of p21 and Chk1 controls the cyclin D1-RB pathway to mediate senescence onset after G2 arrest. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs259114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uxa, S.; Bernhart, S.H.; Mages, C.F.S.; Fischer, M.; Kohler, R.; Hoffmann, S.; Stadler, P.F.; Engeland, K.; Muller, G.A. DREAM and RB cooperate to induce gene repression and cell-cycle arrest in response to p53 activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 9087–9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.; Quaas, M.; Steiner, L.; Engeland, K. The p53-p21-DREAM-CDE/CHR pathway regulates G2/M cell cycle genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ayad, N.G.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Kirschner, M.W.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. Degradation of the SCF component Skp2 in cell-cycle phase G1 by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 2004, 428, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listovsky, T.; Sale, J.E. Sequestration of CDH1 by MAD2L2 prevents premature APC/C activation prior to anaphase onset. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 203, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouery, B.L.; Baker, E.M.; Mei, L.; Wolff, S.C.; Mills, C.A.; Fleifel, D.; Mulugeta, N.; Herring, L.E.; Cook, J.G. APC/C prevents a noncanonical order of cyclin/CDK activity to maintain CDK4/6 inhibitor-induced arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319574121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliopoulos, M.G.; Alfieri, C. Cell cycle regulation by complex nanomachines. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 5100–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, J.E.; Karhohs, K.W.; Mock, C.; Batchelor, E.; Loewer, A.; Lahav, G. p53 dynamics control cell fate. Science 2012, 336, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, R.; Pilpel, N.; Tokarsky-Amiel, R.; Biran, A.; Ovadya, Y.; Cohen, S.; Vadai, E.; Dassa, L.; Shahar, E.; Condiotti, R.; et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, D.; Essmann, F.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Janicke, R. U. p21 blocks irradiation-induced apoptosis downstream of mitochondria by inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated caspase-9 activation. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11254–11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yu, Z.; Sunchu, B.; Shoaf, J.; Dang, I.; Zhao, S.; Caples, K.; Bradley, L.; Beaver, L.M.; Ho, E.; et al. Rapamycin inhibits the secretory phenotype of senescent cells by a Nrf2-independent mechanism. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Tchkonia, T.; Ding, H.; Ogrodnik, M.; Lubbers, E.R.; Pirtskhalava, T.; White, T.A.; Johnson, K.O.; Stout, M.B.; Mezera, V.; et al. JAK inhibition alleviates the cellular senescence-associated secretory phenotype and frailty in old age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6301–E6310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir, N.; Banito, A.; Roe, J.S.; Alonso-Curbelo, D.; Camiolo, M.; Tschaharganeh, D.F.; Huang, C.H.; Aksoy, O.; Bolden, J.E.; Chen, C.C.; et al. BRD4 Connects Enhancer Remodeling to Senescence Immune Surveillance. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 612–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Ren, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.J. cGAS is essential for cellular senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4612–E4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, M.; Ito, Y.; Kang, T.W.; Weekes, M.P.; Matheson, N.J.; Patten, D.A.; Shetty, S.; Parry, A.J.; Menon, S.; Salama, R.; et al. NOTCH1 mediates a switch between two distinct secretomes during senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Xu, Q.; Martin, T.D.; Li, M.Z.; Demaria, M.; Aron, L.; Lu, T.; Yankner, B.A.; Campisi, J.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science 2015, 349, aaa5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takai, H.; Smogorzewska, A.; de Lange, T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G.; Jurk, D.; Marques, F.D.; Correia-Melo, C.; Hardy, T.; Gackowska, A.; Anderson, R.; Taschuk, M.; Mann, J.; Passos, J.F. Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodier, F.; Munoz, D.P.; Teachenor, R.; Chu, V.; Le, O.; Bhaumik, D.; Coppe, J.P.; Campeau, E.; Beausejour, C.M.; Kim, S.H.; et al. DNA-SCARS: Distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, A.C.; Roniger, M.; Oren, Y.S.; Im, M.M.; Sarni, D.; Chaoat, M.; Bensimon, A.; Zamir, G.; Shewach, D.S.; Kerem, B. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell 2011, 145, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.H.; Hwang, H.J.; Kang, D.; Park, H.A.; Lee, H.C.; Jeong, D.; Lee, K.; Park, H.J.; Ko, Y.G.; Lee, J.S. mTOR kinase leads to PTEN-loss-induced cellular senescence by phosphorylating p53. Oncogene 2019, 38, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimonti, A.; Nardella, C.; Chen, Z.; Clohessy, J.G.; Carracedo, A.; Trotman, L.C.; Cheng, K.; Varmeh, S.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; et al. A novel type of cellular senescence that can be enhanced in mouse models and human tumor xenografts to suppress prostate tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.D.; Campisi, J. The metabolic roots of senescence: Mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, L.; Bailey, J.; Glick, A.B.; Dellambra, E.; Scarponi, C.; Pallotta, S.; Albanesi, C.; Madonna, S. RAS-activated PI3K/AKT signaling sustains cellular senescence via P53/P21 axis in experimental models of psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2024, 115, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R.; Fumagalli, M.; Cicalese, A.; Piccinin, S.; Gasparini, P.; Luise, C.; Schurra, C.; Garre, M.; Nuciforo, P.G.; Bensimon, A.; et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature 2006, 444, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsantis, P.; Silva, L.M.; Irmscher, S.; Jones, R.M.; Folkes, L.; Gromak, N.; Petermann, E. Increased global transcription activity as a mechanism of replication stress in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donne, R.; Saroul-Ainama, M.; Cordier, P.; Hammoutene, A.; Kabore, C.; Stadler, M.; Nemazanyy, I.; Galy-Fauroux, I.; Herrag, M.; Riedl, T.; et al. Replication stress triggered by nucleotide pool imbalance drives DNA damage and cGAS-STING pathway activation in NAFLD. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1728–1741 e1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L.C.; Douma, S.; van Doorn, R.; Desmet, C.J.; Aarden, L.A.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppe, J.P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Munoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, 2853–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, J.C.; O’Loghlen, A.; Banito, A.; Guijarro, M.V.; Augert, A.; Raguz, S.; Fumagalli, M.; Da Costa, M.; Brown, C.; Popov, N.; et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 2008, 133, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, S.; Alessio, N.; Acar, M.B.; Mert, E.; Omerli, F.; Peluso, G.; Galderisi, U. Unbiased analysis of senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) to identify common components following different genotoxic stresses. Aging 2016, 8, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, R.M.; Sun, Y.; Orjalo, A.V.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Zhou, L.; Curran, S.C.; Davalos, A.R.; Wilson-Edell, K.A.; Liu, S.; et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1049–1061, Erratum in Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Y.V.; Rattanavirotkul, N.; Olova, N.; Salzano, A.; Quintanilla, A.; Tarrats, N.; Kiourtis, C.; Muller, M.; Green, A.R.; Adams, P.D.; et al. Notch Signaling Mediates Secondary Senescence. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 997–1007.e1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedje, C.; Ronkina, N.; Tehrani, M.; Dhamija, S.; Laass, K.; Holtmann, H.; Kotlyarov, A.; Gaestel, M. The p38/MK2-driven exchange between tristetraprolin and HuR regulates AU-rich element-dependent translation. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, M.; Nunez, S.; Heard, E.; Narita, M.; Lin, A.W.; Hearn, S.A.; Spector, D.L.; Hannon, G.J.; Lowe, S.W. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003, 113, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Poustovoitov, M.V.; Ye, X.; Santos, H.A.; Chen, W.; Daganzo, S.M.; Erzberger, J.P.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Canutescu, A.A.; Dunbrack, R.L.; et al. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contrepois, K.; Thuret, J.Y.; Courbeyrette, R.; Fenaille, F.; Mann, C. Deacetylation of H4-K16Ac and heterochromatin assembly in senescence. Epigenet. Chromatin 2012, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Pawlikowski, J.; Manoharan, I.; van Tuyn, J.; Nelson, D.M.; Rai, T.S.; Shah, P.P.; Hewitt, G.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Passos, J.F.; et al. Lysosome-mediated processing of chromatin in senescence. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaie, M.; Salama, R.; Carroll, T.; Tomimatsu, K.; Chandra, T.; Young, A.R.; Narita, M.; Perez-Mancera, P.A.; Bennett, D.C.; Chong, H.; et al. Redistribution of the Lamin B1 genomic binding profile affects rearrangement of heterochromatic domains and SAHF formation during senescence. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, K.M.; Iwasaki, O.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Tanizawa, H.; Fatkhutdinov, N.; Bitler, B.G.; Le, L.; Alicea, G.; Yang, T.L.; Johnson, F.B.; et al. HMGB2 orchestrates the chromatin landscape of senescence-associated secretory phenotype gene loci. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, K.J.; Carroll, P.; Martin, C.A.; Murina, O.; Fluteau, A.; Simpson, D.J.; Olova, N.; Sutcliffe, H.; Rainger, J.K.; Leitch, A.; et al. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature 2017, 548, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cecco, M.; Ito, T.; Petrashen, A.P.; Elias, A.E.; Skvir, N.J.; Criscione, S.W.; Caligiana, A.; Brocculi, G.; Adney, E.M.; Boeke, J.D.; et al. L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature 2019, 566, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullani, N.; Porozhan, Y.; Mangelinck, A.; Rachez, C.; Costallat, M.; Batsche, E.; Goodhardt, M.; Cenci, G.; Mann, C.; Muchardt, C. Reduced RNA turnover as a driver of cellular senescence. Life Sci. Alliance 2021, 4, e202000809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Chen, R.; Sheu, M.; Kim, N.; Kim, S.; Islam, N.; Wier, E.M.; Wang, G.; Li, A.; Park, A.; et al. Noncoding dsRNA induces retinoic acid synthesis to stimulate hair follicle regeneration via TLR3. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Wilson, J.G.; Reiner, A.P.; Aviv, A.; Raj, K.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Li, Y.; Stewart, J.D.; et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2019, 11, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Prat, L.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Perdiguero, E.; Ortet, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Rebollo, E.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Gutarra, S.; Ballestar, E.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 2016, 529, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimri, G.P.; Lee, X.; Basile, G.; Acosta, M.; Scott, G.; Roskelley, C.; Medrano, E.E.; Linskens, M.; Rubelj, I.; Pereira-Smith, O.; et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakimoto, Y.; Okada, C.; Kawabe, N.; Sasaki, A.; Tsukamoto, H.; Nagao, R.; Osawa, M. Myocardial lipofuscin accumulation in ageing and sudden cardiac death. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.R.; Narita, M.; Ferreira, M.; Kirschner, K.; Sadaie, M.; Darot, J.F.; Tavare, S.; Arakawa, S.; Shimizu, S.; Watt, F.M.; et al. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Nakamura, K.; Matsui, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Nakahara, Y.; Suzuki-Migishima, R.; Yokoyama, M.; Mishima, K.; Saito, I.; Okano, H.; et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 2006, 441, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Bertolotti, A.; Zeng, H.; Ron, D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Bennett, B.S.; Cullinan, S.B.; Diehl, J.A. PERK and GCN2 contribute to eIF2alpha phosphorylation and cell cycle arrest after activation of the unfolded protein response pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 5493–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Kang, C.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, S.V. Brief guide to senescence assays using cultured mammalian cells. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, O.H.; Wilson, D.R.; Clement, C.C.; Rathod, S.; Cherry, C.; Powell, B.; Lee, Z.; Khalil, A.M.; Green, J.J.; Campisi, J.; et al. Senescence cell-associated extracellular vesicles serve as osteoarthritis disease and therapeutic markers. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e125019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seara, F.A.C.; Maciel, L.; Kasai-Brunswick, T.H.; Nascimento, J.H.M.; Campos-de-Carvalho, A.C. Extracellular Vesicles and Cardiac Aging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1418, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xue, X.; Han, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lu, T.; Zhang, P. An effective system for senescence modulating drug development using quantitative high-content analysis and high-throughput screening. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Candia, A.M.; de Avila, D.X.; Moreira, G.R.; Villacorta, H.; Maisel, A.S. Growth differentiation factor-15, a novel systemic biomarker of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular aging: Potential role in cardiovascular diseases. Am. Heart J. Plus Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2021, 9, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; Bayir, H.; Belousov, V.; Chang, C.J.; Davies, K.J.A.; Davies, M.J.; Dick, T.P.; Finkel, T.; Forman, H.J.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.; et al. Guidelines for measuring reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.J.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, E.K.; Park, S.I.; Lee, S.J. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Torres, M.; Bachar-Wikstrom, E.; Wikstrom, J.D. Cellular and molecular roles of reactive oxygen species in wound healing. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okado-Matsumoto, A.; Fridovich, I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38388–38393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Emerging mechanisms of lipid peroxidation in regulated cell death and its physiological implications. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duche, G.; Sanderson, J.M. The Chemical Reactivity of Membrane Lipids. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3284–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Oh, M.; Lee, E.W. An integrated view of lipid metabolism in ferroptosis revisited via lipidomic analysis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreng, S.; Ota, N.; Sun, Y.; Ho, H.; Johnson, M.; Arthur, C.P.; Schneider, K.; Lehoux, I.; Davies, C.W.; Mortara, K.; et al. Structure of the core human NADPH oxidase NOX2. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q. The Applications and Mechanisms of Superoxide Dismutase in Medicine, Food, and Cosmetics. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Tian, H.X.; Rong, D.C.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Xu, H.; Mei, J.; Wang, L.Y.; Liou, Y.L.; et al. ROS homeostasis in cell fate, pathophysiology, and therapeutic interventions. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; He, J.; Rusling, J.F. Electrochemical transformations catalyzed by cytochrome P450s and peroxidases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 5135–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Min, T.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Che, Q.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Oxidative stress in alcoholic liver disease, focusing on proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Fresser, L.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Interplay of oxidative stress and antioxidant mechanisms in cancer development and progression. Arch. Toxicol. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohda, A.; Kamakura, S.; Hayase, J.; Sumimoto, H. The NADPH oxidases DUOX1 and DUOX2 are sorted to the apical plasma membrane in epithelial cells via their respective maturation factors DUOXA1 and DUOXA2. Genes Cells 2024, 29, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liang, L.; Dai, Z.; Zuo, P.; Yu, S.; Lu, Y.; Ding, D.; Chen, H.; Shan, H.; Jin, Y.; et al. A conserved N-terminal motif of CUL3 contributes to assembly and E3 ligase activity of CRL3(KLHL22). Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Inoue, J.; Iso, T.; Wells, G.; Moore, T.W.; Mizushima, T.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Kasai, T.; Kamei, T.; et al. Molecular basis for the disruption of Keap1-Nrf2 interaction via Hinge & Latch mechanism. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, J.F.; Motz, G.T.; Puga, A. Heme oxygenase-1 induction by NRF2 requires inactivation of the transcriptional repressor BACH1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7074–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Hales, C.N.; Ozanne, S.E. DNA damage, cellular senescence and organismal ageing: Causal or correlative? Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7417–7428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Li, T.; Ma, F.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Liu, Q. DNA damage-dependent mechanisms of ionizing radiation-induced cellular senescence. PeerJ 2025, 13, e20087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.; Scuoppo, C.; Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Balgley, B.; Bolden, J.E.; Premsrirut, P.; Luo, W.; Chicas, A.; Lee, C.S.; et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-kappaB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, K.C.; Alspach, E.; Pazolli, E.; Parajuli, S.; Ren, Q.; Arthur, L.L.; Tapia, R.; Stewart, S.A. c-Myb and C/EBPbeta regulate OPN and other senescence-associated secretory phenotype factors. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, L.; Taguchi, K.; Zhang, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Kensler, T.W.; Yamamoto, M. A NRF2-induced secretory phenotype activates immune surveillance to remove irreparably damaged cells. Redox Biol. 2023, 66, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, A.; Hejazi, S.M.; Canesin, G.; Choudhury, R.; Hanafy, K.A.; Csizmadia, E.; Persson, J.L.; Wegiel, B. Heme detoxification by heme oxygenase-1 reinstates proliferative and immune balances upon genotoxic tissue injury. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuollo, L.; Antonangeli, F.; Santoni, A.; Soriani, A. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) in the Challenging Future of Cancer Therapy and Age-Related Diseases. Biology 2020, 9, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogliati, S.; Frezza, C.; Soriano, M.E.; Varanita, T.; Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Corrado, M.; Cipolat, S.; Costa, V.; Casarin, A.; Gomes, L.C.; et al. Mitochondrial cristae shape determines respiratory chain supercomplexes assembly and respiratory efficiency. Cell 2013, 155, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrera, L.; Prieto Clemente, L.; Dahlhaus, A.; Lotfipour Nasudivar, S.; Tishina, S.; Olmo Gonzalez, D.; Stroh, J.; Yapici, F.I.; Singh, R.P.; Grotehans, N.; et al. Ferroptosis triggers mitochondrial fragmentation via Drp1 activation. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Encina, M.; Booth, L.K.; Redgrave, R.E.; Folaranmi, O.; Spyridopoulos, I.; Richardson, G.D. Cellular Senescence, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Their Link to Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.D.; Velarde, M.C.; Lecot, P.; Liu, S.; Sarnoski, E.A.; Freund, A.; Shirakawa, K.; Lim, H.W.; Davis, S.S.; Ramanathan, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Senescence with a Distinct Secretory Phenotype. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pei, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Y.; Hao, S.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the regulation of aging and aging-related diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]