Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Related to 100-Seed Weight in the Korean Soybean Core Collection Using a Genome-Wide Association Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

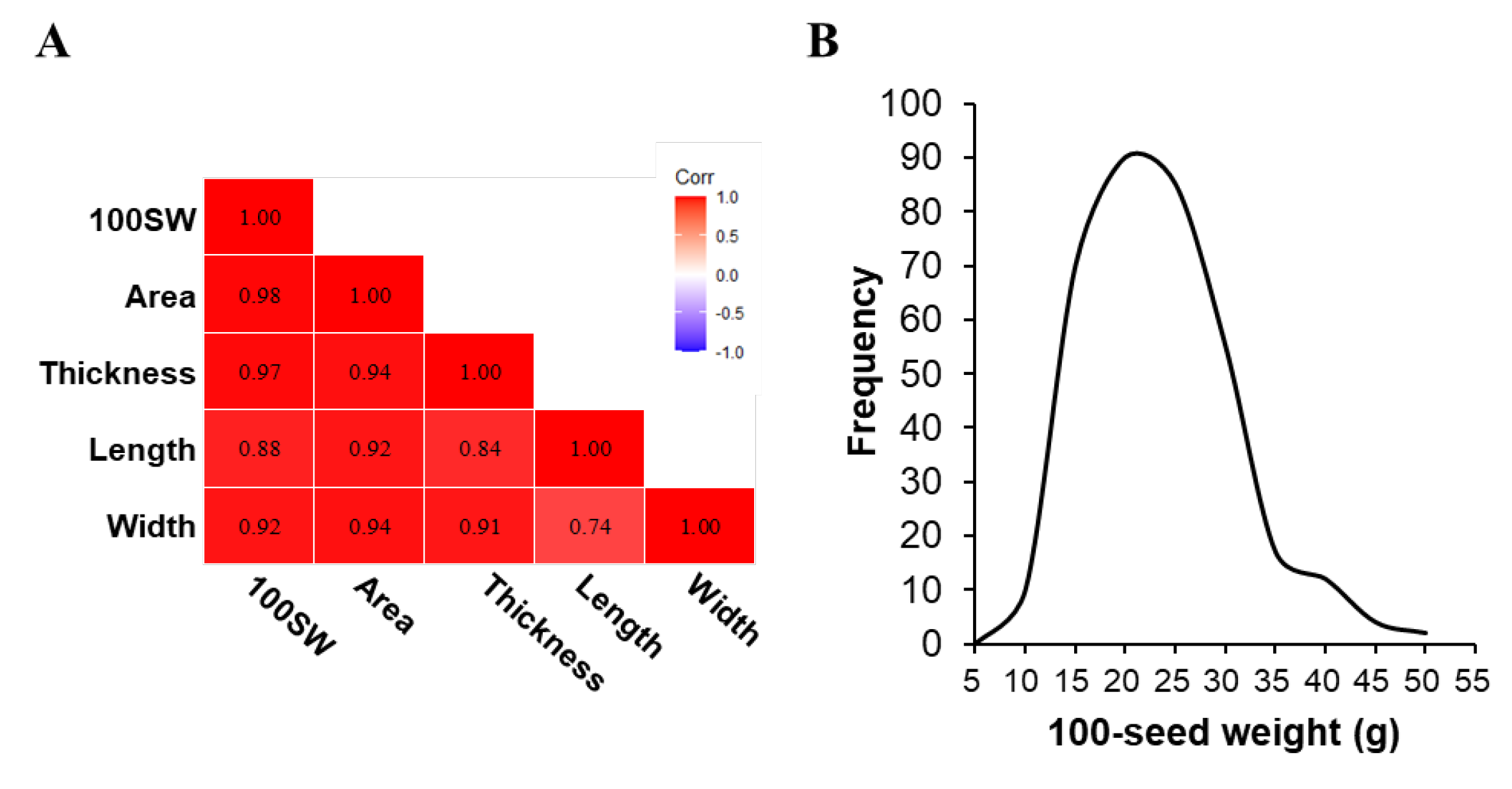

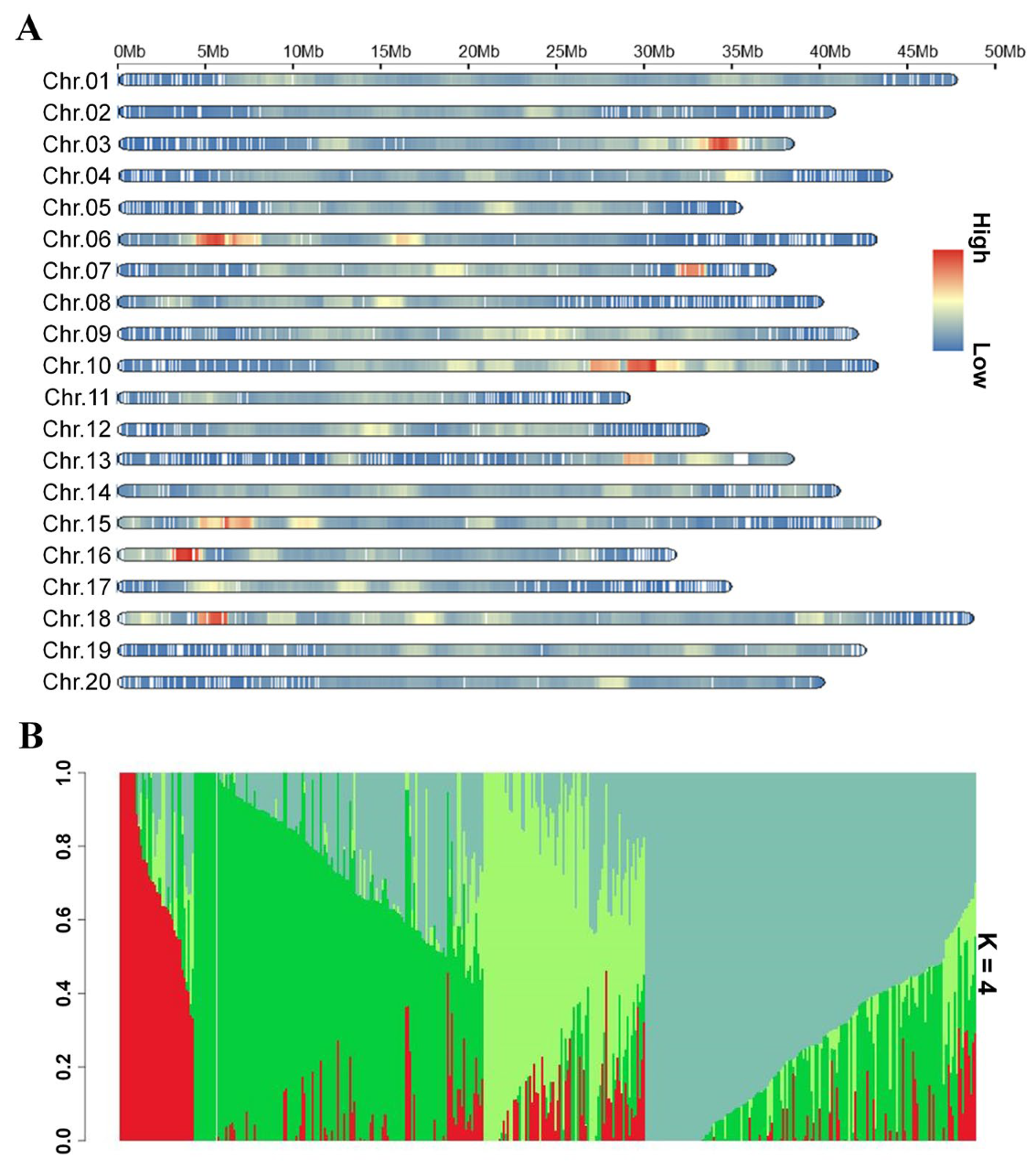

2.1. Analysis of Genetic Variation Between Phenotypes Related to Seed Yield

2.2. Identification of Loci Associated with 100SW According to the GWAS

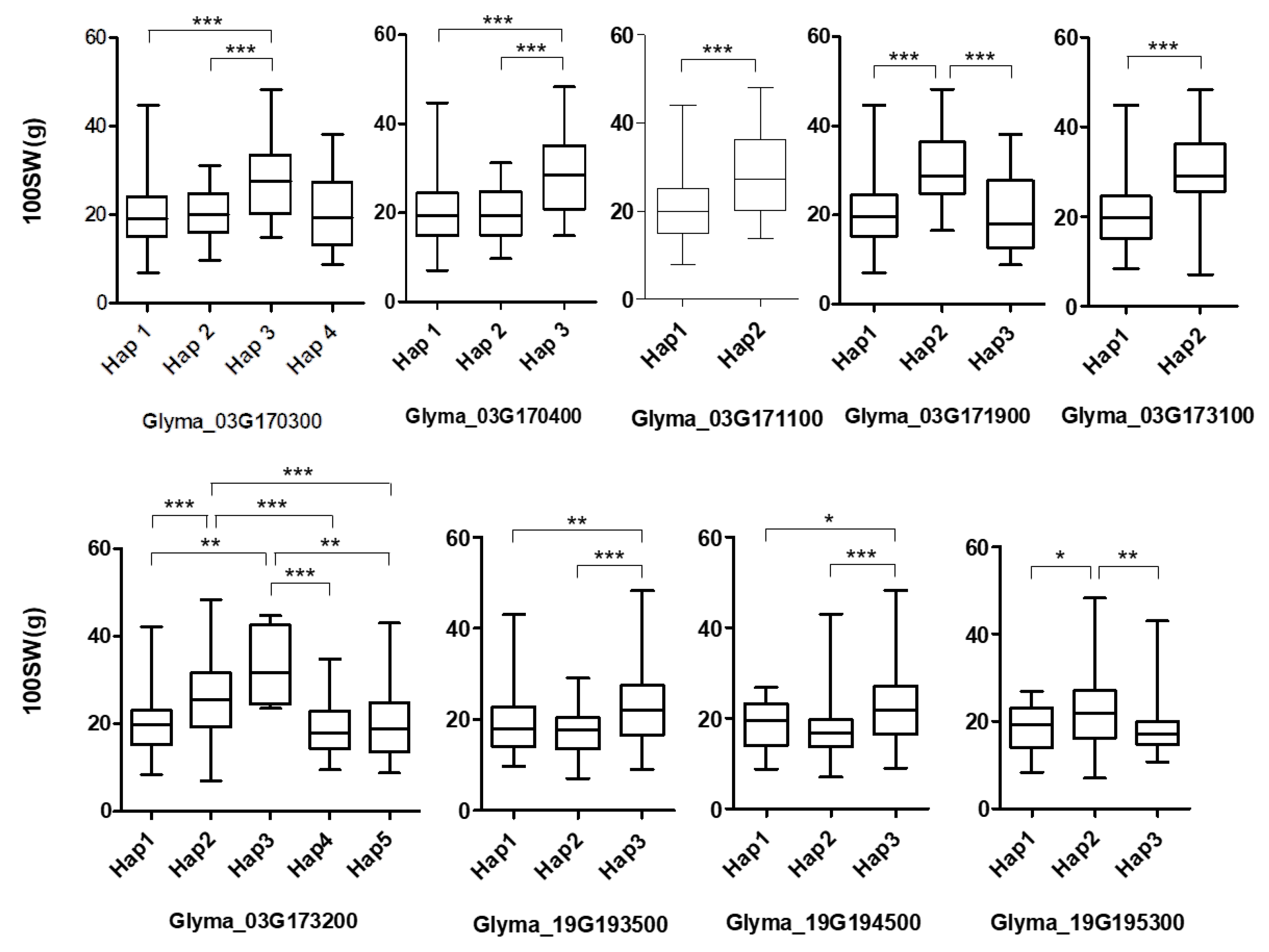

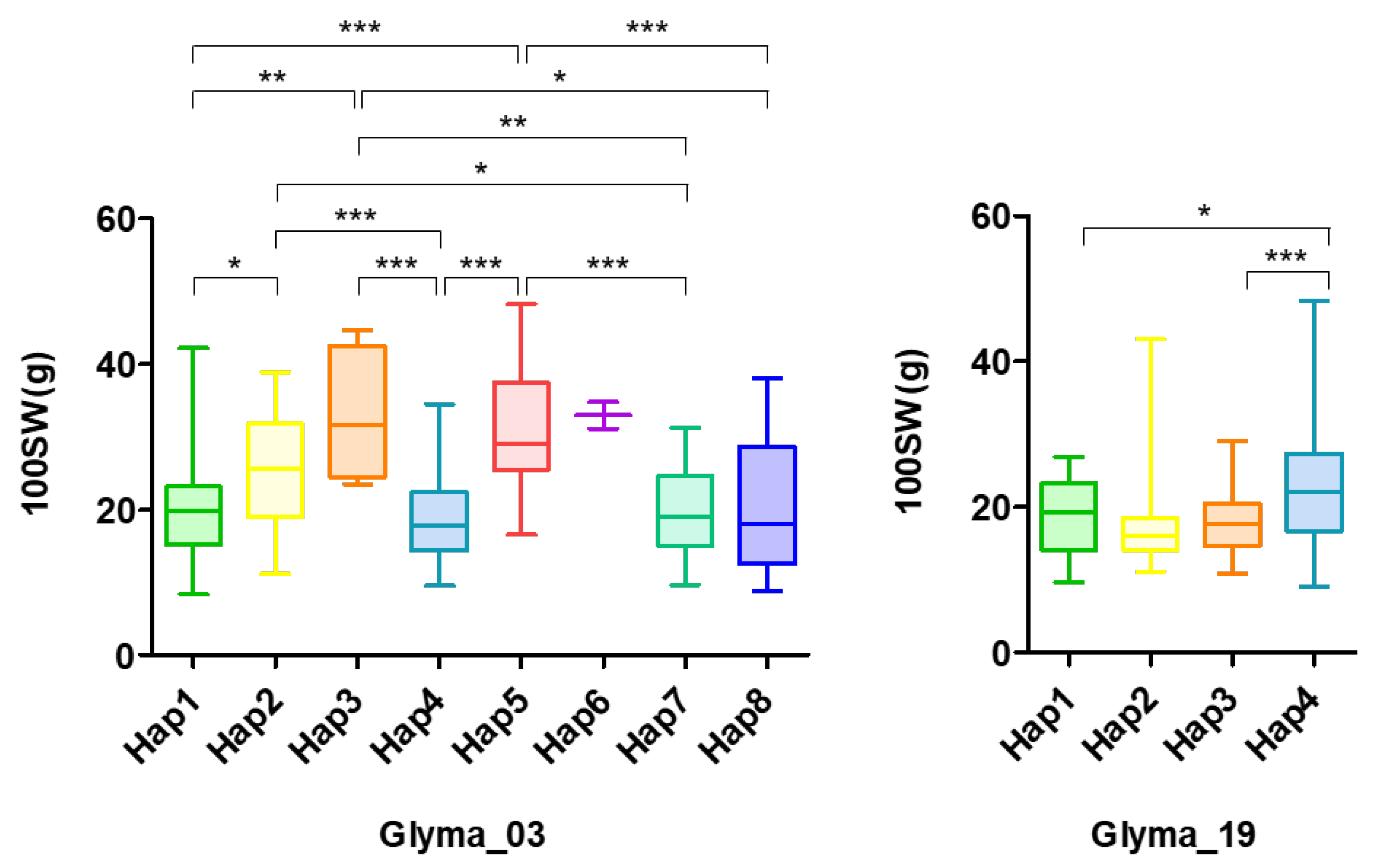

2.3. Haplotypes for the Seed Weight Trait

2.4. Candidate Gene Prediction and Further Analyses

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Phenotypic Evaluation

4.2. Genome-Wide Association Study and Haplotype Analysis

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karikari, B.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, J.; Bhat, J.A.; Zhao, T. Utilization of interspecific high-density genetic map of RIL population for the QTL detection and candidate gene mining for 100-seed weight in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xu, R.; Li, Y. Molecular networks of seed size control in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, J.E.; Kahlon, C.S. Soybean yield formation: What controls it and how it can be improved. In Soybean: Physiology and Biochemistry; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Kim, M.Y.; Van, K.; Lee, Y.-H.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Lee, S.-H. QTL identification of yield-related traits and their association with flowering and maturity in soybean. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 14, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, D.; Zhu, D.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Teng, W.; Li, W. QTL analysis of soybean seed weight across multi-genetic backgrounds and environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Sayama, T.; Fujii, K.; Yumoto, S.; Kono, Y.; Hwang, T.-Y.; Kikuchi, A.; Takada, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Shiraiwa, T. A major and stable QTL associated with seed weight in soybean across multiple environments and genetic backgrounds. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Guo, S.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhao, C.; Shan, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Y.-h. A natural allelic variant of GmSW17. 1 confers high 100-seed weight in soybean. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Song, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, S.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, C. Identification of QTNs controlling 100-seed weight in soybean using multilocus genome-wide association studies. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Han, X.; Zuo, J.-F.; Song, J.; Han, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Zhang, Y.-M. Identification of QTNs and their candidate genes for 100-seed weight in soybean (Glycine max L.) using multi-locus genome-wide association studies. Genes 2020, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Jia, J.; Liu, R.; Wei, R.; Guo, Z.; Cai, Z.; Chen, B.; Liang, F.; Xia, Q.; Nian, H. Identification of major QTLs for soybean seed size and seed weight traits using a RIL population in different environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1094112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Hofmann, N.; Li, S.; Ferreira, M.E.; Song, B.; Jiang, G.; Ren, S.; Quigley, C.; Fickus, E.; Cregan, P. Identification of QTL with large effect on seed weight in a selective population of soybean with genome-wide association and fixation index analyses. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hou, J.; Hu, Q.; An, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. Pedigree-based genetic dissection of quantitative loci for seed quality and yield characters in improved soybean. Mol. Breed. 2021, 41, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Zhou, B.; Ruan, Y.-L.; Shou, H. Identification of regulatory networks and hub genes controlling soybean seed set and size using RNA sequencing analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Dai, A.; Wei, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, B.; Jiang, N.; Feng, X. Arabidopsis KLU homologue GmCYP78A72 regulates seed size in soybean. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Tang, J.; Yue, X.; Gu, J.; Zhao, B.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y. Identification of the domestication gene GmCYP82C4 underlying the major quantitative trait locus for the seed weight in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.X.; Paddock, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Stacey, M.G. GmKIX8-1 regulates organ size in soybean and is the causative gene for the major seed weight QTL qSw17-1. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagoaga, C.; Tadeo, F.R.; Iglesias, D.J.; Huerta, L.; Lliso, I.; Vidal, A.M.; Talón, M.; Navarro, L.; García-Martínez, J.-L.; Peña, L. Engineering of gibberellin levels in citrus by sense and antisense. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, J.J.; Lu, L.; Jiang, Z.H.; Wei, J.J.; Wu, C.M.; Yin, C.C.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.D. GmJAZ3 interacts with GmRR18a and GmMYC2a to regulate seed traits in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1983–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xiong, Q.; Cheng, T.; Li, Q.-T.; Liu, X.-L.; Bi, Y.-D.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.-K.; Ma, B.; Lai, Y.-C. A PP2C-1 allele underlying a quantitative trait locus enhances soybean 100-seed weight. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Chaitieng, B.; Hirano, K.; Kaga, A.; Takagi, K.; Ogiso-Tanaka, E.; Thavarasook, C.; Ishimoto, M.; Tomooka, N. Multiple organ gigantism caused by mutation in VmPPD gene in blackgram (Vigna mungo). Breed. Sci. 2017, 67, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, W.; Zhuang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, T.; Yang, J.; Ambrose, M.; Hu, Z.; Weller, J.L.; et al. BIGGER ORGANS and ELEPHANT EAR-LIKE LEAF1 control organ size and floral organ internal asymmetry in pea. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 70, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Luth, D.; Bai, G.; Wang, K.; Chen, R. Increasing seed size and quality by manipulating BIG SEEDS1 in legume species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12414–12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, T.R.; Duceppe, M.-O.; O’Donoughue, L.S. Identification of novel loci associated with maturity and yield traits in early maturity soybean plant introduction lines. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, R.M.; Torabi, S.; Lukens, L.; Eskandari, M. Genomic regions associated with important seed quality traits in food-grade soybeans. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, C.; Jing, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Han, Y. Identification of quantitative trait loci underlying soybean (Glycine max) 100-seed weight under different levels of phosphorus fertilizer application. Plant Breed. 2020, 139, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yu, D. Development and application of a novel genome-wide SNP array reveals domestication history in soybean. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Jia, Q.; Hu, S.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Su, C. Genome-Wide Association Study on Candidate Genes Associated with Soybean Stem Pubescence and Hilum Colors. Agronomy 2024, 14, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanatha, C.; Torkamaneh, D.; Rajcan, I. Genome-Wide Association Study of Soybean Germplasm Derived From Canadian × Chinese Crosses to Mine for Novel Alleles to Improve Seed Yield and Seed Quality Traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 866300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-S.; Lozano, R.; Kim, J.H.; Bae, D.N.; Kim, S.-T.; Park, J.-H.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, J.; Ok, H.-C.; Park, S.-K. The patterns of deleterious mutations during the domestication of soybean. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.T.; Moon, J.-K.; Park, S.; Park, S.-K.; Baek, J.; Seo, M.-S. Genome-wide analysis of KIX gene family for organ size regulation in soybean (Glycine max L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1252016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.G.; Pfeiffer, T.W.; Buss, G.R.; Kilen, T.C. Qualitative genetics. In Soybeans: Improvement, Production, and Uses; Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 16, pp. 137–233. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Marek, L.; Shoemaker, R.; Lark, K.; Concibido, V.; Delannay, X.; Specht, J.E.; Cregan, P. A new integrated genetic linkage map of the soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Githiri, S.M.; Hatayama, K.; Dubouzet, E.G.; Shimada, N.; Aoki, T.; Ayabe, S.-i.; Iwashina, T.; Toda, K.; Matsumura, H. A single-base deletion in soybean flavonol synthase gene is associated with magenta flower color. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 63, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikari, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, W.; Feng, J.; Zhao, T. Identification of quantitative trait nucleotides and candidate genes for soybean seed weight by multiple models of genome-wide association study. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dong, H.; Chang, H.; Zhao, J.; Teng, W.; Qiu, L.; Li, W.; Han, Y. Genome wide association mapping and candidate gene analysis for hundred seed weight in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill]. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, L.; Zeng, J.; Razzaq, M.K.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Xing, G.; Gai, J. Identification of additive–epistatic QTLs conferring seed traits in soybean using recombinant inbred lines. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 566056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Guo, P.; Hao, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; Zhao, L.; Luo, W.; He, J. Differential SW16. 1 allelic effects and genetic backgrounds contributed to increased seed weight after soybean domestication. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1734–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, I.; Kathare, P.K.; Kim, J.-I.; Huq, E. Expanding roles of PIFs in signal integration from multiple processes. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Kang, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; Kamiya, Y.; Choi, G. Genome-wide analysis of genes targeted by PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3-LIKE5 during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hu, J.; Yusuke, J.; Jung, B.; Paik, I.; Lee, H.-S.; Sun, T.-P.; Kamiya, Y.; Choi, G. PIL5, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH protein, regulates gibberellin responsiveness by binding directly to the GAI and RGA promoters in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1192–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Ariyoshi, Y.; Taniguchi, T.; Nakagawa, A.C.; Hamaoka, N.; Iwaya-Inoue, M.; Suriyasak, C.; Ishibashi, Y. Heat shock protein 70 is associated with duration of cell proliferation in early pod development of soybean. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.; Kallberg, Y.; Oppermann, U.; Jörnvall, H. Coenzyme-based functional assignments of short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs). Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2003, 143, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Jin, Y.; Akhter, D.; Chen, J. Bioinformatic analysis of short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase proteins in plant peroxisomes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1180647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandri, M.; Smirnov, A.; Novelli, F.; Pitolli, C.; Agostini, M.; Malewicz, M.; Melino, G.; Raschellà, G. Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-X.; Zhang, F.-C.; Zhang, W.-Z.; Song, L.-F.; Wu, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-F. Arabidopsis Di19 functions as a transcription factor and modulates PR1, PR2, and PR5 expression in response to drought stress. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 1487–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, C. Genome-wide analysis of C2H2 zinc-finger family transcription factors and their responses to abiotic stresses in poplar (Populus trichocarpa). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Ke, X.-J.; Lan, H.-X.; Yuan, X.; Huang, P.; Xu, E.-S.; Gao, X.-Y.; Wang, R.-Q.; Tang, H.-J.; Zhang, H.-S. A Cys2/His2 zinc finger protein acts as a repressor of the green revolution gene SD1/OsGA20ox2 in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Tao, J.J.; Cheng, T.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Jiang, Z.H.; Sun, W.C. Global analysis of seed transcriptomes reveals a novel PLATZ regulator for seed size and weight control in soybean. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 2436–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Pei, X.; Kong, F.; Zhao, L.; Lin, X. Divergence of functions and expression patterns of soybean bZIP transcription factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1150363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Hao, D.; Chao, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Su, X.; Jiang, M. Downregulation of a gibberellin 3β-hydroxylase enhances photosynthesis and increases seed yield in soybean. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, L.; Pelletier, J.M.; Hsu, S.-W.; Baden, R.; Goldberg, R.B.; Harada, J.J. Combinatorial interactions of the LEC1 transcription factor specify diverse developmental programs during soybean seed development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Lei, C. Gene SGL, encoding a kinesin-like protein with transactivation activity, is involved in grain length and plant height in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Lee, E.; Kim, N.; Kim, S.L.; Choi, I.; Ji, H.; Chung, Y.S.; Choi, M.-S.; Moon, J.-K.; Kim, K.-H. High throughput phenotyping for various traits on soybean seeds using image analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.-C.; Moon, J.-K.; Park, S.-K.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.R.; Jeong, N.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, N.; Kang, S.-T. Genetic diversity patterns and domestication origin of soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Dai, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Sanchez, D.L.; Lübberstedt, T.; Kang, Y.; Udvardi, M.K.; Beavis, W.D.; Xu, S. GWASpro: A high-performance genome-wide association analysis server. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2512–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Marker a | Chr. b | Year | log10(p) c | Effect Allele d (Ref->Alt) | Phenotypic Effect e (Mean Difference, g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| snp.03.38576307 | 3 | 2016 | 6.45 | A->T | 8.3 |

| 2017 | 6.71 | 8.56 | |||

| 2021 | 5.05 | 7.22 | |||

| snp.03.38576403 | 3 | 2016 | 6.45 | A->G | 8.3 |

| 2017 | 6.71 | 8.56 | |||

| 2021 | 5.05 | 7.22 | |||

| snp.03.38685095 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | C->T | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.57 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.14 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.03.38685383 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | T->A | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.57 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.14 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.03.38685486 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | A->G | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.57 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.14 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.03.38685655 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | T->C | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.61 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.08 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.03.38686042 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | T->G | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.57 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.14 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.03.38686093 | 3 | 2016 | 5.97 | T->C | 4.69 |

| 2017 | 5.57 | 4.4 | |||

| 2021 | 5.14 | 4.33 | |||

| snp.04.40965491 | 4 | 2016 | 7 | G->A | 6.86 |

| 2017 | 6.25 | 6.65 | |||

| 2021 | 5.62 | 6.21 | |||

| snp.19.45174797 | 19 | 2016 | 5.38 | G->A | 9.33 |

| 2017 | 5.54 | 9.5 | |||

| 2021 | 6.8 | 8.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, J.Y.; Park, S.; Park, S.-K.; Moon, J.-K.; Kim, J.A.; Seo, M.-S. Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Related to 100-Seed Weight in the Korean Soybean Core Collection Using a Genome-Wide Association Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411921

Moon JY, Park S, Park S-K, Moon J-K, Kim JA, Seo M-S. Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Related to 100-Seed Weight in the Korean Soybean Core Collection Using a Genome-Wide Association Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411921

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Ju Yeon, Sangjun Park, Soo-Kwon Park, Jung-Kyung Moon, Jin A. Kim, and Mi-Suk Seo. 2025. "Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Related to 100-Seed Weight in the Korean Soybean Core Collection Using a Genome-Wide Association Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411921

APA StyleMoon, J. Y., Park, S., Park, S.-K., Moon, J.-K., Kim, J. A., & Seo, M.-S. (2025). Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Related to 100-Seed Weight in the Korean Soybean Core Collection Using a Genome-Wide Association Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411921