Abstract

Polymorphisms in the leptin gene (LEP) have been associated with leptin levels and anthropometric variables; however, their association with lipid profiles remains under study. We aimed to determine the relationship between LEP single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and body mass index (BMI), leptin levels, and lipid profiles in prepubertal children. This cross-sectional study included a population-based sample of 1270 males and females aged 6-to-8 years. Lipid and leptin levels were quantified, and the SNVs G19A and G2548A were analyzed by real-time PCR using predesigned TaqMan™ Genotyping Assays. We found that both LEP SNVs were significantly associated with leptin levels after adjusting for sex. No significant associations between the studied SNVs and BMI were observed in our population. Additionally, both SNVs were associated with apolipoprotein AI (Apo-AI) levels in females, whereas G2548A was also associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels after adjusting for sex. These associations remained statistically significant after adjusting for leptin levels. No association was found between SNVs and other lipid variable levels. Our results indicate that polymorphisms in the LEP gene influence not only leptin levels but also lipid metabolism, as evidenced by their association with Apo-AI and HDL-C, independent of plasma leptin concentrations.

1. Introduction

Leptin is an adipocyte-derived hormone that, in addition to maintaining energy homeostasis, plays an important role in regulating lipid metabolism. It promotes lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation and downregulates lipogenesis [1,2]. In this regard, besides being analyzed for its association with obesity, the association of leptin levels with lipid profiles has been extensively studied in adults [3,4,5] and children [6,7,8,9], describing an association with an adverse lipid profile. We described a significant positive association of leptin with triglyceride levels and a negative association with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and apolipoprotein AI (Apo-AI) concentrations in a cohort of prepubertal children [10]. The association we have described between plasma leptin levels and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) concentrations in this cohort of children aged 6–8 years is particularly interesting [11].

Two single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the leptin gene, G19A and G2548A, located in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the human leptin gene, have been reported to be associated with body mass index (BMI) and obesity, as well as leptin levels, but with discordant results [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Studies in children also focused on these SNVs are scarce [21,22,23,24]. We previously described a sex-dependent relationship of G2548A with leptin levels and obesity in a population-based sample of Spanish adolescents [25].

In contrast, the association of these SNVs with lipid levels has been less explored, and the results of the analysis to date have been inconclusive [26,27,28,29]. Although the role of leptin in lipolysis is well known [1,2], to our knowledge, its association with NEFA levels has not been investigated.

In our study, we analyzed whether the SNVs G19A and G2548A in the leptin gene are associated with BMI, leptin levels, and lipid profile, particularly NEFA, in early life by analyzing a large sample population of prepubertal children.

2. Results

Table 1 summarizes the age, BMI, leptin levels, and lipid parameters of the study population according to gender. The mean age was the same for males and females (7.2 ± 0.6 years), and the mean BMI value did not significantly differ between genders (Table 1). However, compared to males, females exhibited significantly higher mean levels of leptin, triglycerides (TGs), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and apolipoprotein B (Apo-B), and lower mean levels of Apo-AI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age, BMI, and biochemical parameters of the study sample population by sex. Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

2.1. Genotype and Allele Frequencies of LEP SNVs

The characterization and genotype distributions of the analyzed LEP SNVs are presented in Table 2. The minor allele frequencies (MAFs) of the G19A and G2548A polymorphisms in the leptin gene were 34.0% and 43.0%, respectively. The observed allelic distributions were consistent with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) principles.

Table 2.

Description, genotype, and allele distribution of the studied SNVs in the LEP gene.

For both LEP SNVs (G19A and G2548A), GG denotes homozygosity for the major ancestral allele (G), GA indicates heterozygosity for G and A alleles, and AA represents homozygosity for the minor allele (A).

2.2. Association Between LEP SNVs and BMI and Leptin Levels

The association between leptin SNVs G19A and G2548A and BMI and leptin levels was assessed using a univariate ANOVA adjusted for sex (Table 3). No statistically significant differences in BMI were observed for either LEP SNVs. However, the association between LEP SNVs and leptin levels showed significant differences across the genotypes. For the LEP SNV G19A, a progressive increase in leptin levels was observed in the GG, GA, and AA genotypes (Table 3), with AA carriers showing significantly higher leptin levels than GG carriers (p = 0.033). For the G2548A LEP SNV, we observed the opposite effect; the presence of the A allele was significantly associated with lower leptin levels, with GG carriers showing significantly higher leptin levels than A allele carriers (p = 0.016) (Table 3).

Table 3.

BMI and leptin levels by LEP SNVs adjusted for sex.

2.3. Association Between LEP SNVs and Lipid Parameters

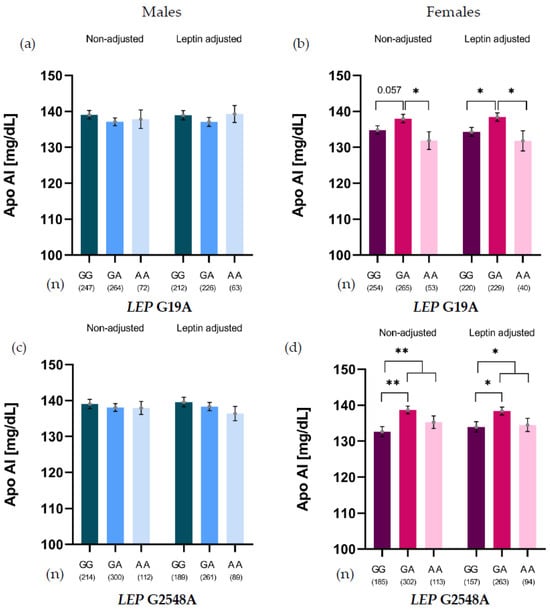

The relationship between the LEP SNVs G19A and G2548A and lipid variables was analyzed by stratifying the results by sex. A significant association between both SNVs and Apo-AI levels was only observed in females (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Apo-AI levels of LEP G19A genotypes in males (a) and females (b), and LEP G2548A genotypes in males (c) and females (d), non-adjusted and adjusted for leptin levels. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

For G19A, heterozygotes (GA) showed higher Apo-AI levels than GG carriers (p = 0.057) and AA homozygotes (p = 0.035). This association was leptin-independent, as the difference persisted after adjusting for leptin, revealing significant differences between GG and GA carriers (p = 0.012) and between AA and GA carriers (p = 0.025) (Figure 1b). For G2548A, GA carriers showed significantly higher Apo-AI levels than GG carriers. This association persisted even after adjusting for leptin levels (Figure 1d).

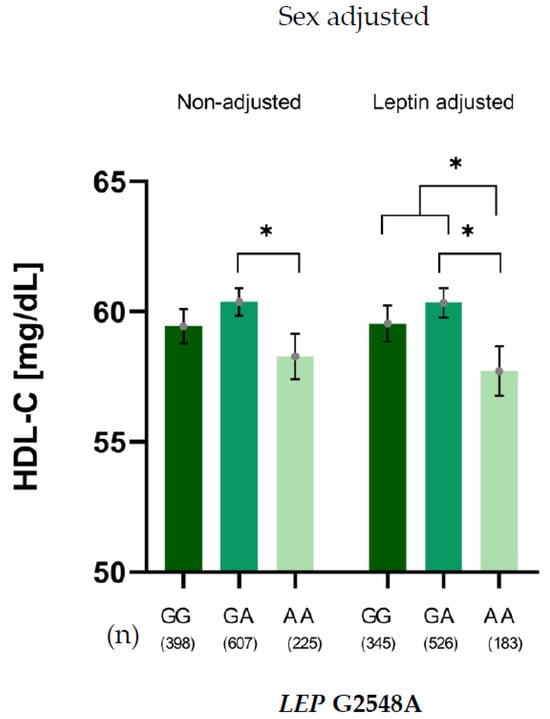

A similar pattern was observed for the relationship between the G2548 LEP SNV and HDL-C levels, adjusted for sex. This relationship persisted after further adjustment for leptin levels, confirming that the association between the G2548A genotype and HDL-C levels was independent of leptin. In this context, G allele carriers showed significantly higher HDL-C levels than AA carriers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HDL-C levels of LEP G2548A genotypes adjusted for sex, non-adjusted and adjusted for leptin levels. * p < 0.05.

We examined the association between LEP SNVs genotypes and other lipid variables (total cholesterol (TC), TG, LDL-C, Apo-B, and NEFA levels). No statistically significant differences were observed across genotypes for any of the lipid parameters.

3. Discussion

Given the significant role of leptin in regulating energy homeostasis, the influence of polymorphisms in the leptin gene on obesity and leptin plasma levels has been extensively analyzed in adults [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and children [21,22,23,24,25]. However, their association with lipid metabolism remains unclear [26,27,28,29]. In our study of prepubertal children, the LEP SNVs G19A and G2548A were not associated with BMI but were significantly associated with leptin levels. These variants were chosen because they are the most widely studied SNVs in the leptin gene and have been central to previous research investigating leptin regulation and metabolic outcomes.

The association of these SNVs in the leptin gene with anthropometric variables and obesity has been reported in several studies in children, including samples of different ages, with discordant results among studies [21,22,23,24,25]. In this sense, we have previously analyzed a cohort of older children (adolescents aged 12-to-16 years) describing a significantly lower presence of the minor allele (A) for the G2548A LEP SNV in overweight/obese females than in normal-weight females. We found that BMI was significantly lower in AA carriers than in GG female carriers [25], supporting the existence of a sex-dependent association. The different associations described in the literature and in our own studies depending on sex and age may be due to the different age- and sex-related hormonal status of the studied populations and point out that the lack of association with BMI in our cohort of younger children could be related to the status of sexual development.

Our study showed that both SNVs were related to leptin concentrations in females. For G19A, GG carriers showed lower leptin levels than A-allele carriers. For G2548A, the GA and AA genotypes had significantly lower plasma leptin levels than GG carriers. Previously, in our cohort of adolescents, we described an association between the G2548A polymorphism and plasma leptin levels, with carriers of the A allele having lower leptin levels [25]. Other studies in children have also reported an association between the AA genotype and lower leptin levels [14,21,22,23].

Functional activity data concerning the activity of LEP polymorphisms remains controversial. As they are located within regions involved in gene regulation, these LEP SNVs do not directly alter the amino acid sequence or structure of the leptin protein. Instead, it is possible that they might affect gene transcription, mRNA stability, and translation [22]. Concerning the G2548A LEP SNV, Hoffstedt et al. [30] reported that A allele carriers showed higher mRNA LEP levels compared to GA/GG carriers, postulating that this promoter variant likely increases transcription by modifying transcription factors binding affinity, enhancing LEP promoter activity, influencing gene expression, and leading to altered circulating leptin levels. Additional studies, such as the study from Kolic et al. [31], found that A allele carriers had significantly higher LEP mRNA levels compared to GG carriers in a cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; however, Song et al. [29], associated the A allele with reduced LEP mRNA expression. Together, these inconsistencies indicate that the regulatory consequences of the G2548A variant remain incompletely understood.

In this sense, an examination of the influence of the rs1137101 variant (LEPR) on LEP mRNA levels across various tissues revealed a significant negative association with LEP mRNA in cultured fibroblasts and the tibial artery, yet a significant positive correlation in tissues such as subcutaneous adipose, brain, and thyroid [29]. We speculate that the regulatory impact of the G2548A variant, and potentially other LEP SNVs, on gene expression may be tissue specific. Although this specific example involves a different variant, it powerfully illustrates the differential regulatory landscape of the LEP locus across distinct human tissues.

The relevant finding in our study is that, when analyzing the association of LEP SNVs with lipid concentrations, we found a relationship with HDL-C and Apo-AI concentrations that remained significant after adjusting for leptin levels. These results strongly suggest that the identified polymorphisms influence lipid metabolism independent of their potential effect on leptin expression or secretion, indicating a direct or pleiotropic mechanism that avoids systemic leptin concentration.

The relationship between circulating leptin and plasma lipid levels remains unclear. Some studies in children have observed a negative association between leptin levels and HDL-C, which has not been observed in other studies or has been described as a positive or negative association depending on sex [6,7,8,9]. We previously described a significant negative association between plasma HDL-C and Apo-AI levels in this cohort of prepubertal children [10]. Thus, polymorphisms that affect leptin levels may be associated with these parameters. However, in our study, we observed that leptin gene polymorphisms were associated with lipid levels independent of leptin levels, distinguishing the genetic effect from the endocrine axis.

Leptin exerts its function by binding to and activating the leptin receptor (LEPR), mainly in the hypothalamus [32,33]. However, the presence of functional leptin receptors in white adipose tissue suggests a direct action of leptin on adipocyte metabolism [34]. Leptin participates in lipid metabolism by inhibiting lipogenesis and stimulating lipolysis in adipose tissue [1,2]. In the liver, a central player in systemic lipid metabolism, leptin can inhibit the gene expression of key lipogenic enzymes, such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase, resulting in decreased de novo lipid synthesis [35]. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that leptin can inhibit adipocyte proliferation [36] and exert autocrine and paracrine lipolytic effects in white adipose tissue, both in vitro and ex vivo [37,38].

The leptin concentration-independent association observed in our study suggests that LEP variants may influence lipid metabolism through alternative mechanisms. These SNVs may be in linkage disequilibrium with regulatory elements affecting LEPR splicing or transcript stability, particularly in hepatocytes and adipocytes [29,30]. Another plausible mechanism is that LEP variants may modulate hepatic HDL-C clearance pathways, suggesting that they might indirectly affect the downstream transcription factors that regulate the activity of the main HDL-C receptor, Scavenger Receptor B1 (SR-B1) [39,40]. This could alter HDL-C catabolism and Apo-AI incorporation into lipoproteins without affecting systemic leptin levels. Collectively, these findings indicate that LEP genetic variation may subtly impact lipid metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport through tissue-specific or regulatory mechanisms independent of circulating leptin.

The strength of our study lies in the fact that we analyzed a homogeneous and broad sample of Caucasian 6-to-8-year-old children without disparity in age and genetic background, as well as free of hormonal influence acting as a confounding factor in our analysis of the relationship between the SNVs and the parameters under study. A limitation of our study is the lack of information on the functional activity of the SNVs which would help clarify their association with the studied variables. An additional important limitation of our study is the lack of physical activity and socioeconomic factors that may affect the variables under study.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that polymorphisms within the leptin gene exert associations independent of leptin concentrations, affecting lipid concentrations. This is substantiated by the observed associations with HDL-C and Apo-AI levels, independent of circulating plasma leptin concentrations. Given the central role of HDL-C and Apo-AI in cardiovascular protection, such variants may contribute to interindividual susceptibility to dyslipidemia and long-term cardiovascular risks.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

The sample population included 1270 prepubertal children (638 males and 632 females), aged 6–8 years old, who participated in a cross-sectional study examining cardiovascular risk factors in Spain [41]. All participants were confirmed to be free of pre-existing endocrine, metabolic, hepatic, or renal disorders.

The study was presented orally to the School Board of each participating school. Subsequently, a letter outlining the study goals and procedures was sent to the parents of all children invited to participate in the study. The parents were required to provide written consent for their children to participate in the study. The study protocol complied with the Helsinki Declaration guidelines and Spanish legal provisions governing human clinical research. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Fundación Jiménez Díaz (approval reference number: PIC105-2023 FJD, 15 September 2023).

4.2. Anthropometric Measurements

Measurements were taken with the children wearing light clothing and barefoot. Weight and height were recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively, using a standardized electronic digital scale and portable stadiometer, respectively. These values were subsequently used to calculate BMI, expressed as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2).

4.3. Biochemical and Genetic Determinations

Sample collection and processing: Fasting (12 h) venous blood samples were obtained early in the morning by venipuncture. Blood was drawn into two types of Vacutainer tubes: one containing EDTA-Na2 as an anticoagulant and the other containing a serum gel separator. Following immediate centrifugation, the resulting fractions (plasma and serum) were separated and immediately stored at −70 °C to ensure preservation for subsequent biochemical and genetic analyses.

Biochemical assays: TC and TG levels were determined enzymatically using a Technicon RA-1000 Autoanalyzer (Menarini Diagnostics, Naples, Italy). HDL-C was measured using an RA-1000 analyzer after precipitation of Apo-B-containing lipoproteins with phosphotungstic acid and Mg2+ (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula. Plasma Apo-AI and Apo-B concentrations were quantified using immunoephelometry (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). The intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for the main analytes were as follows: cholesterol, 1.4%; TG, 1.7%; Apo-AI, 1.6%; and Apo-B, 4.8%.

NEFA levels were measured using the Wako NEFA-C kit (Wako Industries, Osaka, Japan). Leptin levels were measured by ELISA with a commercial kit (Leptin EIA-2395; DRG, Marburg, Germany).

LEP SNVs genotyping: Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from leukocytes according to standard procedures. The quantity and quality of the recovered gDNA were assessed by UV-spectrophotometry using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The selected LEP SNVs, G19A (rs2167270) and G2548A (rs7799039), were genotyped by Real-Time PCR, using predesigned TaqMan™ SNV Genotyping Assays from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA); (C__15966471_20 and C__1328079_10, respectively). The QuantStudio3® Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for allelic discrimination. qPCR was performed using a mixture containing 10 ng genomic DNA and TaqMan™ Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The samples were cycled under the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min, repeated over 40 cycles.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software package (version 25.0; IBM, New York, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8 statistical software (San Diego, CA, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The normality of all continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Variables with skewed distributions were logarithmically transformed prior to the statistical analysis. Initial differences in means between males and females were tested using Student’s t-test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare quantitative variables across genotypes for males and females separately. Post hoc comparisons between genotype groups were conducted using Tukey’s test whenever statistically significant differences were detected (p < 0.05). Univariate analyses were used to compare lipid variables across LEP genotypes, adjusting for both leptin levels and sex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and resources, C.G.; formal analysis and investigation, O.P. and C.G.; data curation, O.P., I.P.-N. and C.G.; writing—original draft, C.G.; writing—review and editing, O.P., F.J.M.-M., A.P.-R., and L.S.-G.; visualization, O.P.; supervision, L.S.-G., and C.G.; project administration, C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through project PI22/00498 and co-funded by the European Union. Olga Pomares has been awarded a research contract from the Carlos III Institute of Health (PFIS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Approval reference: PIC105-2023 FJD, 15 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission from the Jiménez Díaz Foundation Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the late Manuel de Oya as the warmest homage to his memory. de Oya designed the Four Province Study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Apo-AI | Apolipoprotein-AI |

| Apo-B | Apolipoprotein-B |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

| NEFA | Non-Esterified Fatty Acid |

| SR-B1 | Scavenger Receptor B1 |

| SNV | Single-Nucleotide Variant |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| UTR | Untranslated region |

References

- Martínez-Sánchez, N. There and Back Again: Leptin Actions in White Adipose Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, C.; Pomar, C.A.; Rodríguez, A. Leptin as a key regulator of the adipose organ. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 23, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainwater, D.L.; Comuzzie, A.G.; VandeBerg, J.L.; Mahaney, M.C.; Blangero, J. Serum leptin levels are independently correlated with two measures of HDL. Atherosclerosis 1997, 132, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluzik, M.; Fiedler, J.; Nedvidkova, J.; Ceska, R. Serum leptin levels in patients with hyperlipidemias. Nutrition 2000, 16, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisike, G.; Kuerbanjiang, M.; Muheyati, D.; Zaibibuli, K.; Lv, M.; Han, J. Correlation analysis of obesity phenotypes with leptin and adiponectin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavazarakis, E.; Moustaki, M.; Gourgiotis, D.; Drakatos, A.; Bossios, A.; Zeis, P.M.; Xatzidimoula, A.; Karpathios, T. Relation of serum leptin levels to lipid profile in healthy children. Metabolism 2001, 50, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.-M.; Shen, M.-H.; Chu, N.-F. Relationship between plasma leptin levels and lipid profiles among schoolchildren in Taiwan–the Taipei Children Heart Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 17, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, M.; Gascón, F.; Martos, R.; Bermudo, F.; Ceballos, P.; Suanes, A. Relationship between high plasma leptin concentrations and metabolic syndrome in obese pre-pubertal children. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2003, 27, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubey, S.; Kabra, M.; Bajpai, A.; Pandey, R.M.; Hasan, M.; Gautam, R.K.; Menon, P.S.N. Serum leptin levels in obese Indian children relation to clinical and biochemical parameters. Indian Pediatr. 2007, 44, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jois, A.; Navarro, P.; Ortega-Senovilla, H.; Gavela-Pérez, T.; Soriano-Guillén, L.; Garcés, C. Relationship of high leptin levels with an adverse lipid and insulin profile in 6–8-year-old children in Spain. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomares, O.; Vales-Villamarín, C.; Pérez-Nadador, I.; Mejorado-Molano, F.J.; Soriano-Guillén, L.; Garcés, C. Plasma Non-Esterified Fatty Acid levels throughout childhood and its relationship with leptin levels in children. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolés, O.; Sorlí, J.V.; Francés, F.; Coltell, O.; González, J.I.; Sáiz, C.; Corella, D. Effect of genetic variation in the leptin gene promoter and the leptin receptor gene on obesity risk in a population-based case-control study in Spain. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 21, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, S.F.P.; Francischetti, E.A.; Genelhu, V.A.; Cabello, P.H.; Pimentel, M.M.G. LEPR p.Q223R, beta3-AR p.W64R and LEP c.-2548G>A gene variants in obese Brazilian subjects. Genet. Mol. Res. 2007, 6, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ben Ali, S.; Kallel, A.; Ftouhi, B.; Sediri, Y.; Feki, M.; Slimane, H.; Jemaa, R.; Kaabachi, N. Association of G-2548A LEP polymorphism with plasma leptin levels in Tunisian obese patients. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 42, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.-H.; Say, Y.-H. Leptin and leptin receptor gene polymorphisms and their association with plasma leptin levels and obesity in a multi-ethnic Malaysian suburban population. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2014, 33, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki-Khatibi, F.; Shademan, B.; Gholikhani-Darbroud, R.; Nourazarian, A.; Radagdam, S.; Porzour, M. Gene polymorphism of leptin and risk for heart disease, obesity, and high BMI: A systematic review and pooled analysis in adult obese subjects. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2022, 44, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.L.; Camberos, A.M.; Arredondo, M.I.; Magallanes, N.G.; Meraz, E.A. LEP (G2548A-G19A) and ADIPOQ (T45G-G276T) gene polymorphisms are associated with markers for metabolic syndrome. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqlain, M.; Khalid, M.; Fiaz, M.; Saeed, S.; Raja, A.M.; Zafar, M.M.; Fatima, T.; Pesquero, J.B.; Maglio, C.; Valadi, H.; et al. Risk variants of obesity associated genes demonstrate BMI raising effect in a large cohort. PLoS ONE 2024, 17, e0274904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, S.; Sezgin, S.B.A.; Celik, F.; Diramali, M.; Yaylim, I.; Gurol, A.O.; Cakmak, R.; Zeybek, U. The Investigation of Leptin (LEP) and Leptin Receptor (LEPR) Gene Variations in Obese Patients. Clin. Transl. Metab. 2025, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, L.; Ahmadi, N.; Feizy, F.; Lotfipanah, S.; Ghaffari, M.E.; Saltanatpour, Z. Leptin promoter G2548A variant, elevated plasma leptin levels, and increased risk of Type 2 diabetes with CAD in Iranian patients: A genetic association study. J. Diabetes Investig. 2025, 16, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunff, C.L.; Le Bihan, C.; Schork, N.J.; Bougnères, P. A common promoter variant of the leptin gene is associated with changes in the relationship between serum leptin and fat mass in obese girls. Diabetes 2000, 49, 2196–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savino, F.; Rossi, L.; Di Stasio, L.; Galliano, I.; Montanari, P.; Bergallo, M. Mismatch Amplification Mutation Assay Real-Time PCR Analysis of the Leptin Gene G2548A and A19G Polymorphisms and Serum Leptin in Infancy: A Preliminary Investigation. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2016, 85, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ahmed, H.H.; ElSadek, S.M.; Mohamed, R.S.; El-Amir, R.Y.; Salah, W.; Sultan, E.; El-Hassib, D.M.A.; Fouad, H.M. A study of leptin and its gene 2548 G/A Rs7799039 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in Egyptian children: A single-center experience. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2021, 45, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, S.; Yılmaz, R.; Karaslan, E.; Özer, S.; Ateş, Ö.; Ensari, E.; Demir, O. The Relationship of Leptin (+19) AG, Leptin (2548) GA, and Leptin Receptor Gln223Arg Gene Polymorphisms with Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2021, 24, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riestra, P.; García-Anguita, A.; Viturro, E.; Schoppen, S.; de Oya, M.; Garcés, C. Influence of the leptin G-2548A polymorphism on leptin levels and anthropometric measurements in healthy Spanish adolescents. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2010, 74, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Ohzeki, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Sugihara, S.; Arisaka, O. Impact of leptin and leptin-receptor gene polymorphisms on serum lipids in Japanese obese children. Acta Padiatr. 2010, 99, 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Julio, M.A.; Pinhel, M.S.; Quinhoneiro, D.C.G.; Nicoletti, C.F.; Brandão, A.C.; Nonino, C.B.; Pinheiro, S., Jr.; Oliveira, B.A.P.; Gregório, M.L.; Andrade, D.O.; et al. LEP-2548G>A Polymorphism of the Leptin Gene and Its Influence on the Lipid Profile in Obese Individuals. Lifestyle Genom. 2014, 7, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, N.; Hasnain, S. Leptin promoter variant G2548A is associated with serum leptin and HDL-C levels in a case control observational study in association with obesity in a Pakistani cohort. J. Biosci. 2016, 41, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Gong, W.; Ai, Y.; Shen, B.; Li, J.; He, C. The rs7799039 variant in the leptin gene promoter drives insulin resistance through reduced serum leptin levels. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1589575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffstedt, J.; Eriksson, P.; Mottagui-Tabar, S.; Arner, P. A Polymorphism in the Leptin Promoter Region (-2548 G/A) Influences Gene Expression and Adipose Tissue Secretion of Leptin. Horm. Metab. Res. 2002, 34, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolić, I.; Stojković, L.; Stankovic, A.; Stefanović, M.; Dinčić, E.; Zivkovic, M. Association study of rs7799039, rs1137101 and rs8192678 gene variants with disease susceptibility/severity and corresponding LEP, LEPR and PGC1A gene expression in multiple sclerosis. Gene 2021, 774, 145422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Leon, V.; Perez-Lois, R.; Villalon, M.; Prida, E.; Muñoz-Moreno, D.; Fernø, J.; Quiñones, M.; Al-Massadi, O.; Seoane, L.M. Novel mechanisms involved in leptin sensitization in obesity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 223, 116129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, C.; Duensing, A.; Myers, M.G. Molecular mechanisms and neural mediators of leptin action. Genes Dev. 2025, 39, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceddia, R.B. Direct metabolic regulation in skeletal muscle and fat tissue by leptin: Implications for glucose and fatty acids homeostasis. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M.; Werrmann, J.G.; Tota, M.R. 13C NMR study of the effects of leptin treatment on kinetics of hepatic intermediary metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7385–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Gori, F.; Khosla, S.; Jensen, M.D.; Burguera, B.; Riggs, B.L. Leptin acts on human marrow stromal cells to enhance differentiation to osteoblasts and to inhibit differentiation to adipocytes. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruhbeck, G.; Aguado, M.; Martinez, J.A. In vitro lipolytic effect of leptin on mouse adipocytes: Evidence for a possible autocrine/paracrine role of leptin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 240, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kuropatwinski, K.K.; White, D.W.; Hawley, T.S.; Hawley, R.G.; Tartaglia, L.A.; Baumann, H. Leptin receptor action in hepatic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 16216–16223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundåsen, T.; Liao, W.; Angelin, B.; Rudling, M. Leptin Induces the Hepatic High Density Lipoprotein Receptor Scavenger Receptor B Type I (SR-BI) but Not Cholesterol 7α-Hydroxylase (Cyp7a1) in Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 43224–43228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Uña, M.; López-Mancheño, Y.; Diéguez, C.; Fernández-Rojo, M.A.; Novelle, M.G. Unraveling the Role of Leptin in Liver Function and Its Relationship with Liver Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artalejo, F.R.; Garcés, C.; Gil, Á.; Lasunción, M.Á.; José, M.; Moreno, M.; Gorgojo, L.; de Oya, M. The 4 Provinces Study: Its principal objectives and design. The Researchers of the 4 Provinces Study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 1999, 52, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).