Design and Characterization of Aptamers to Antibiotic Kanamycin with Improved Affinity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

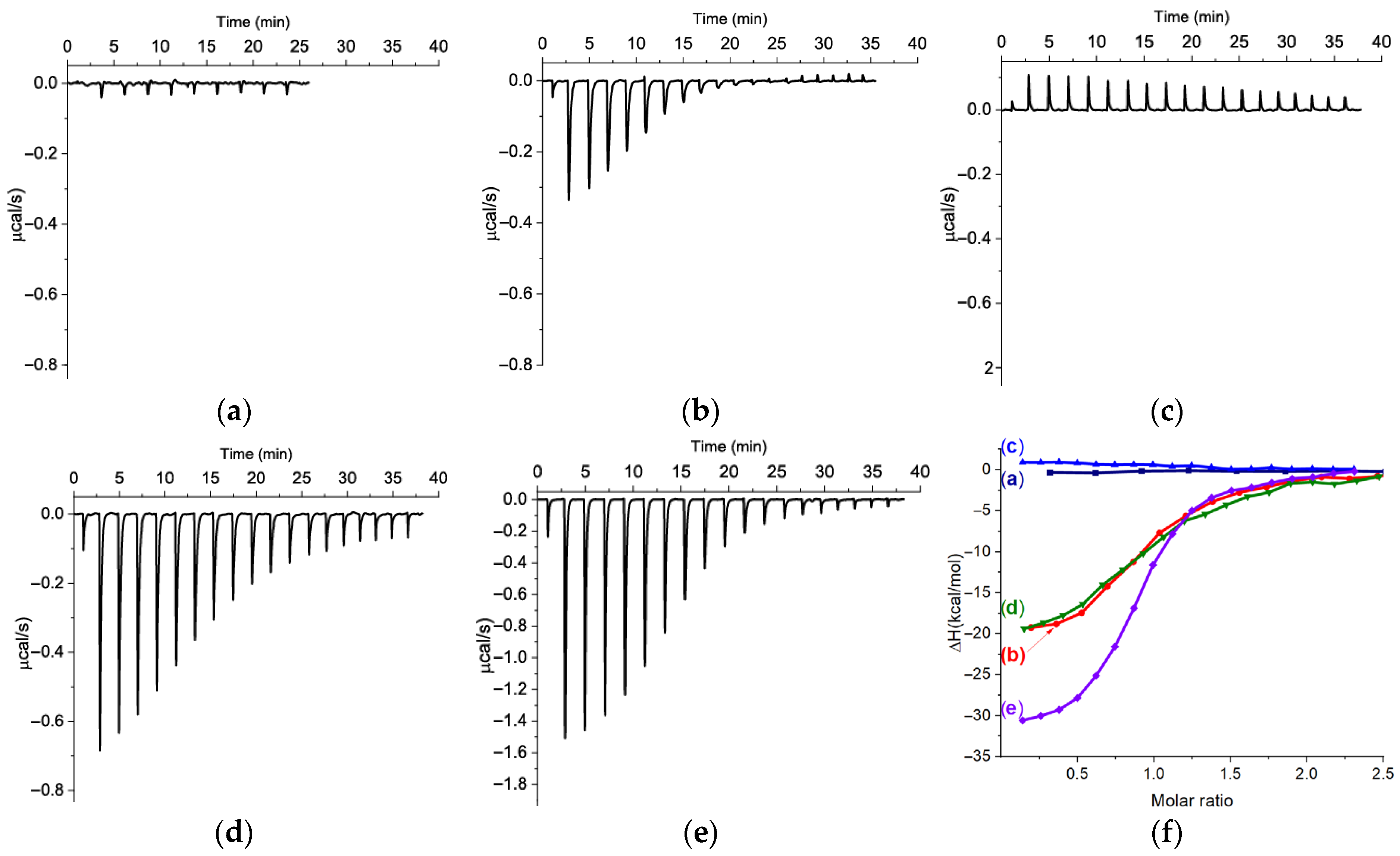

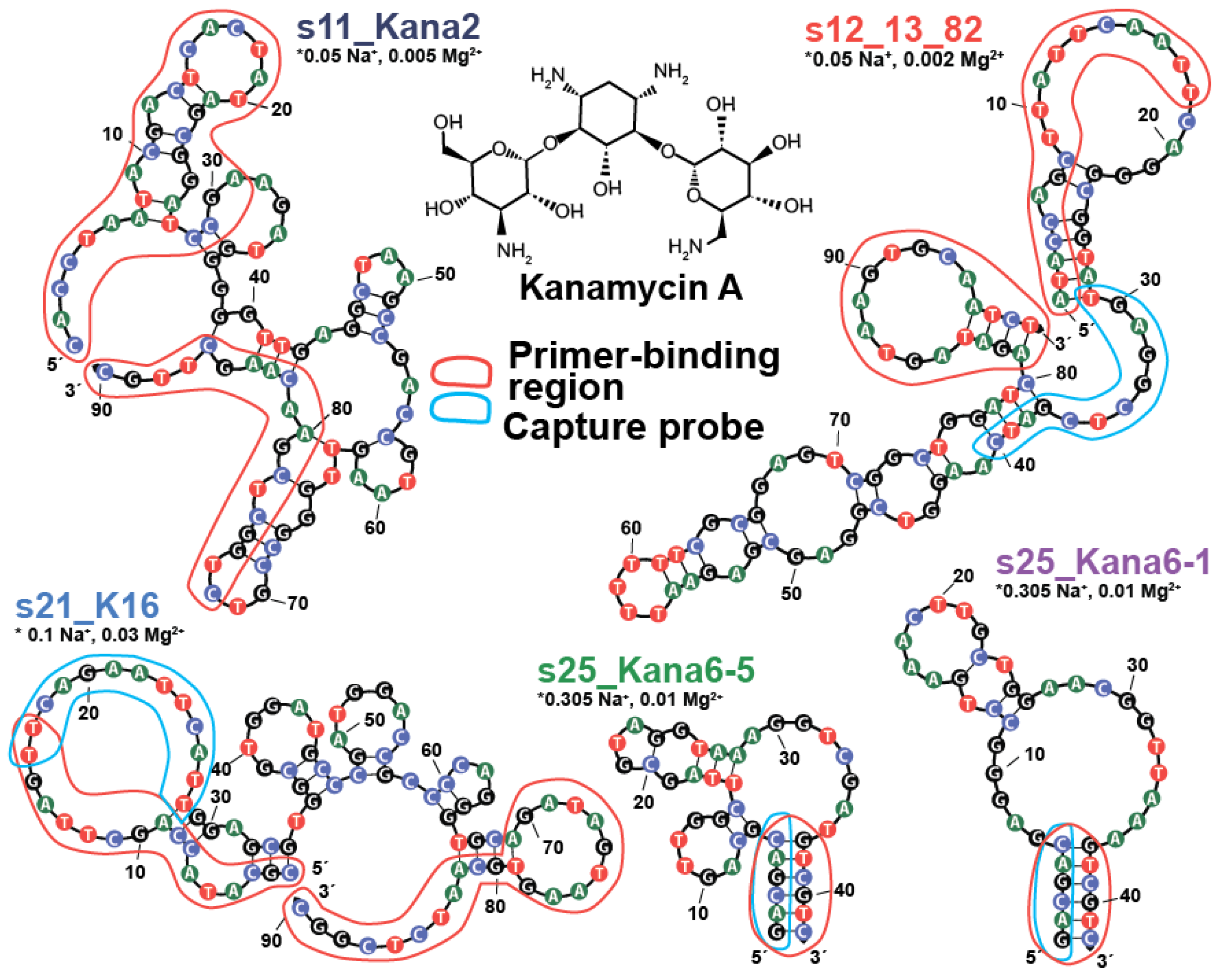

2.1. The Comparison of Affinity for Kanamycin-Binding Aptamers

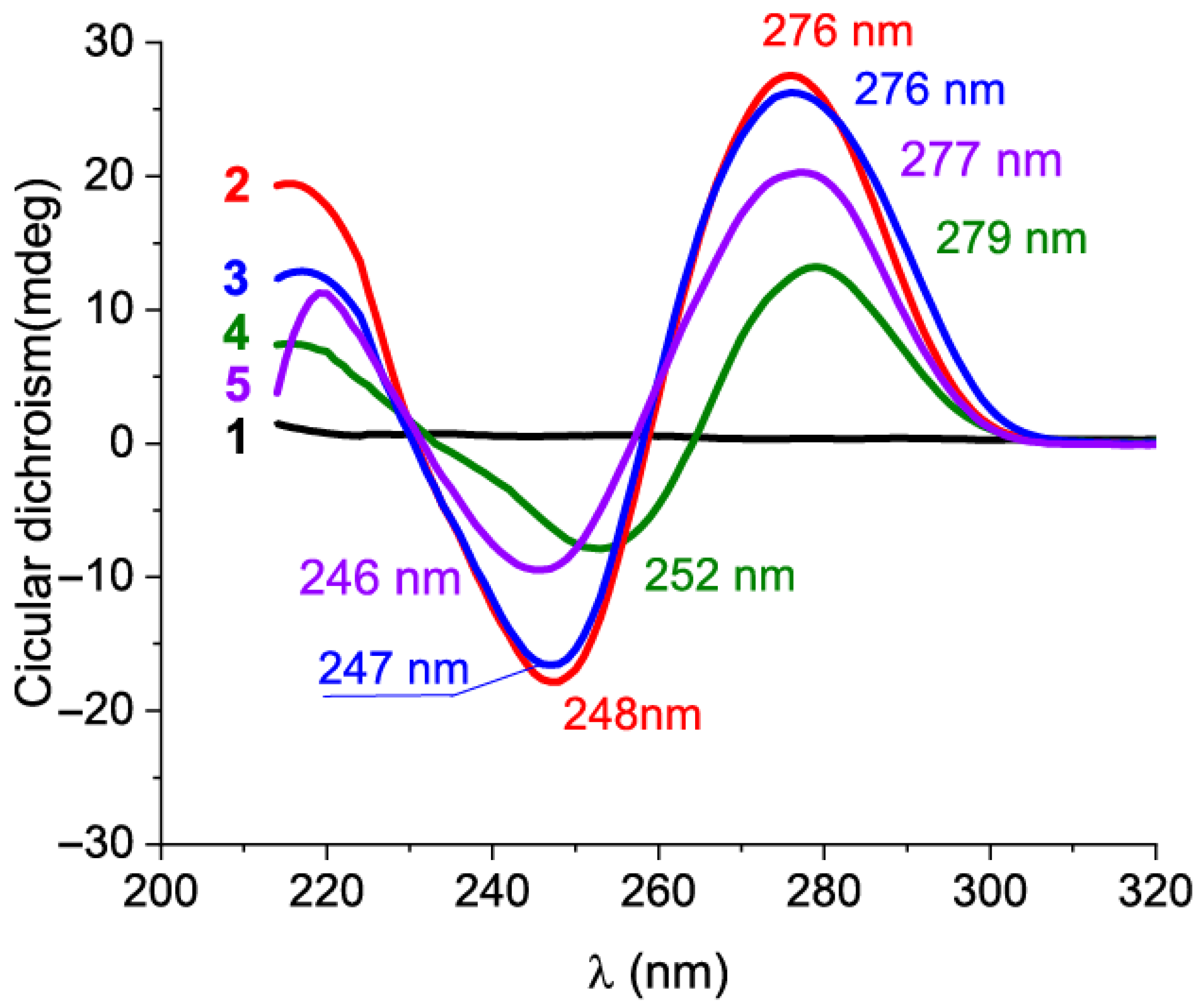

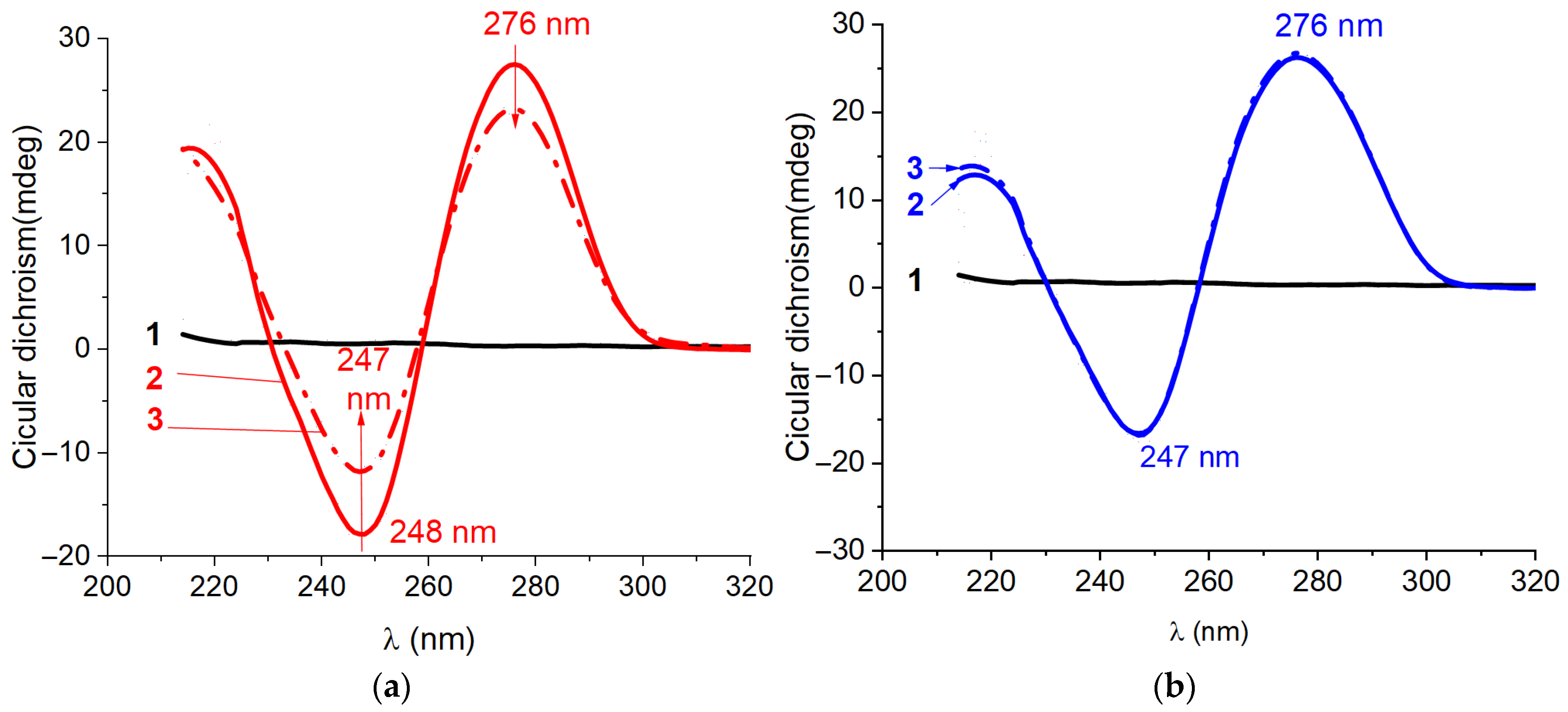

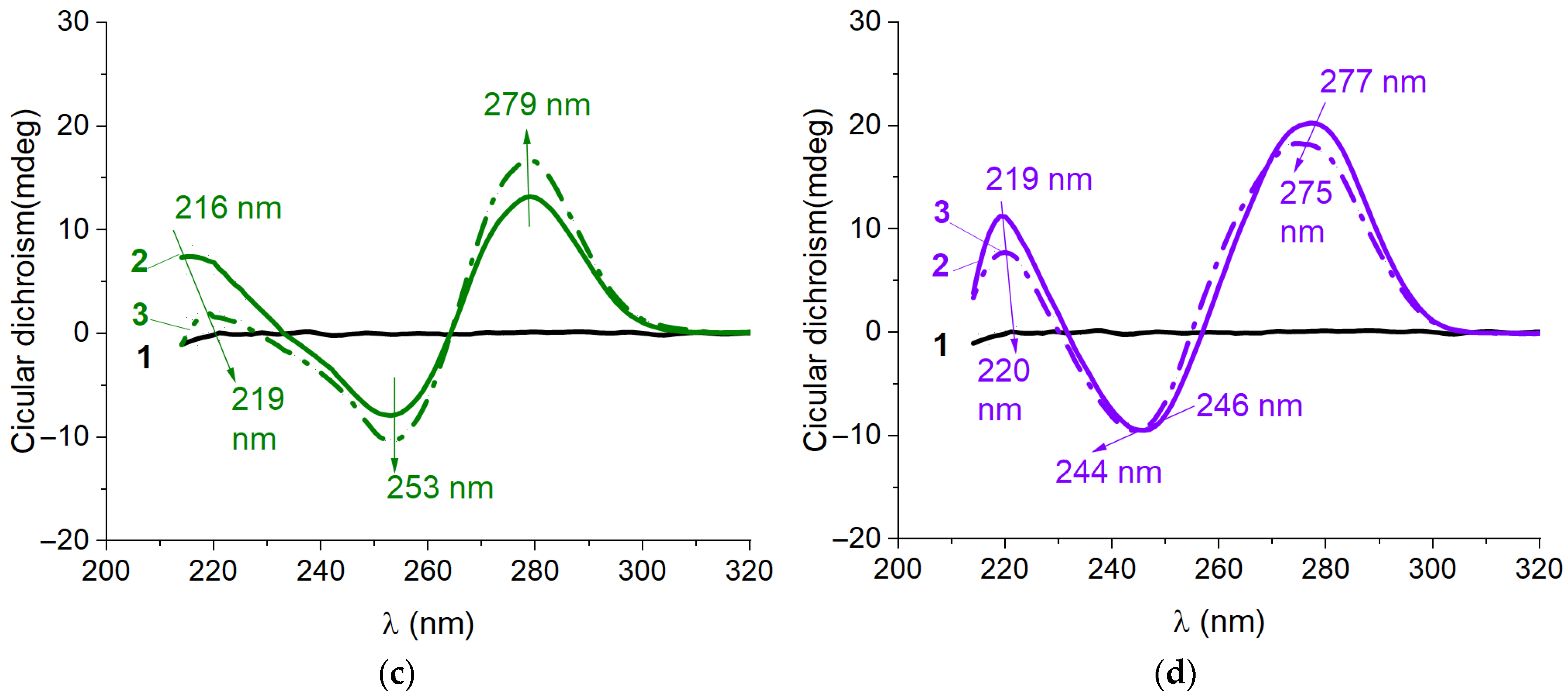

2.2. Characterization of Structure for Kanamycin-Binding Aptamers Using Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

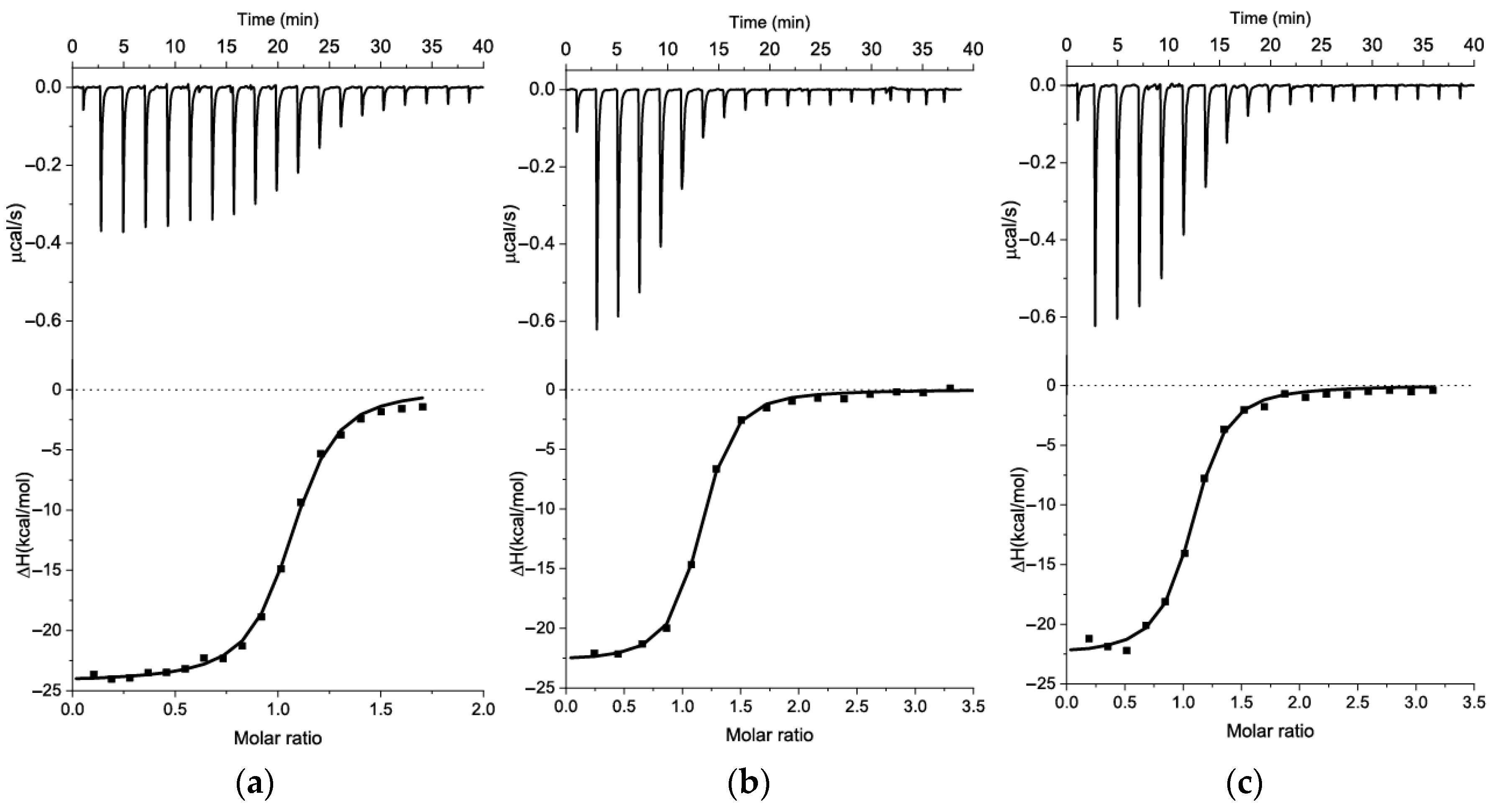

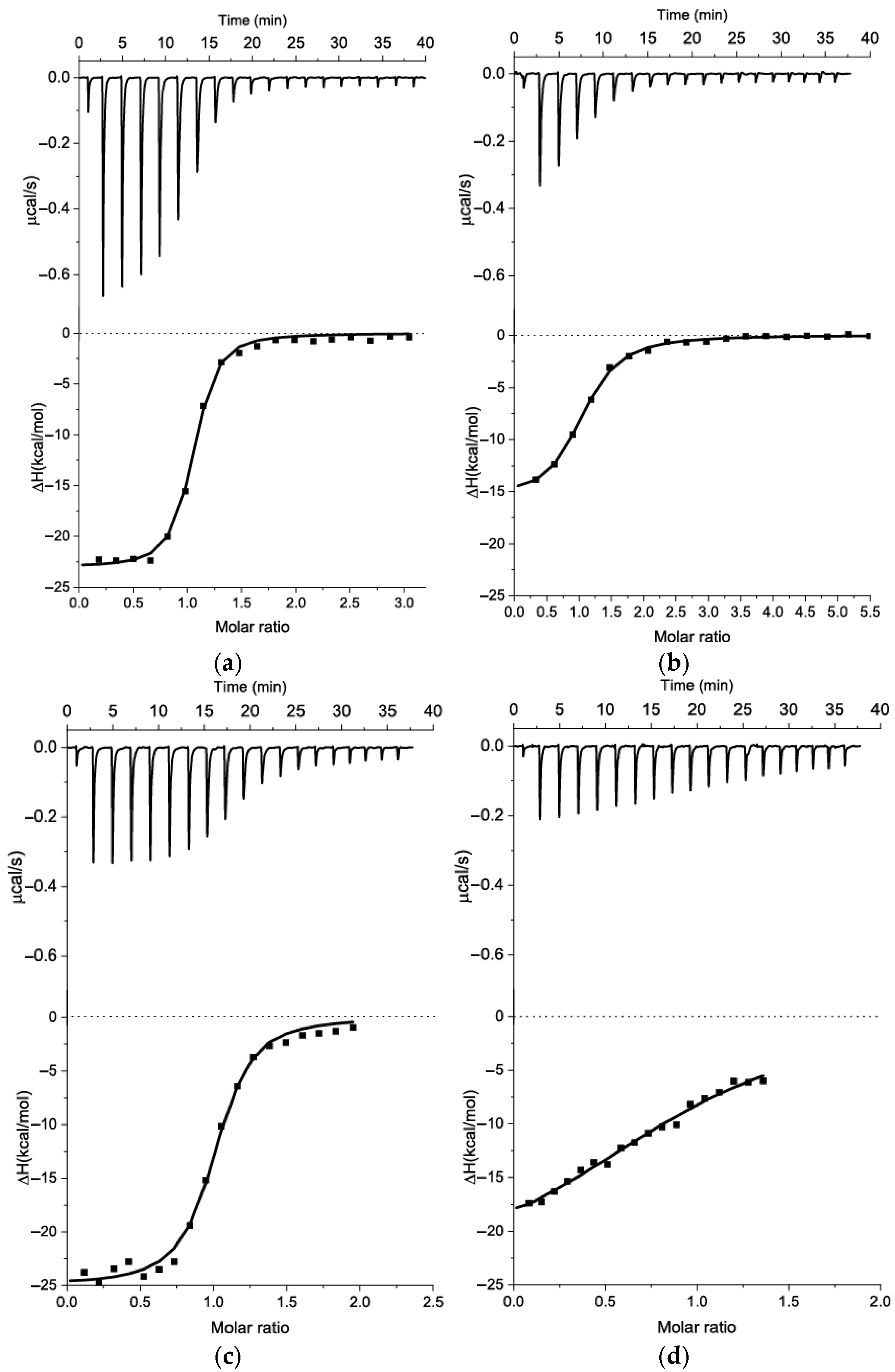

2.3. Modification of Kanamycin Aptamer Based on 2D Model and ITC Measurements

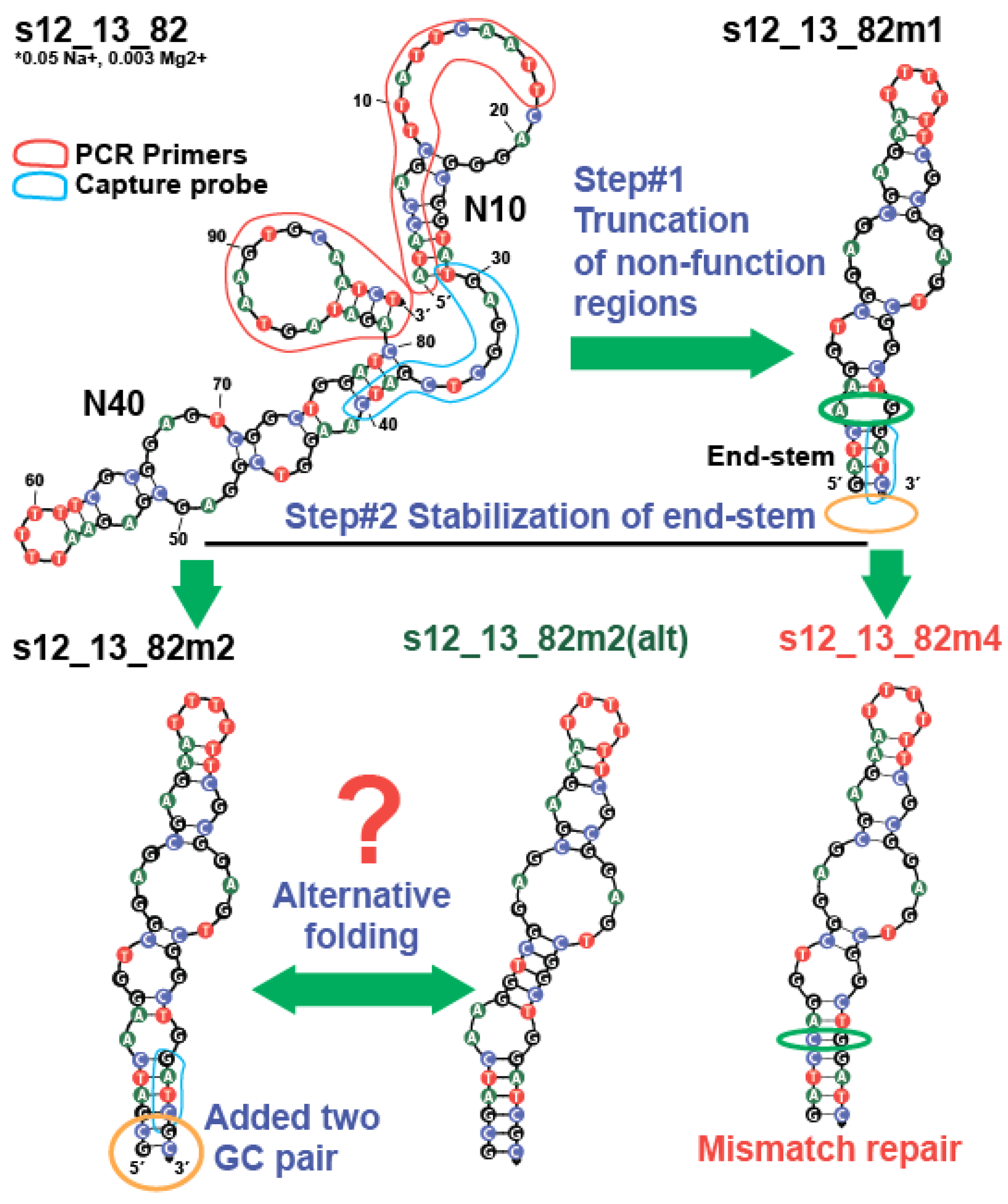

2.3.1. The Truncation of Initial Aptamers and Modification of End-Stem Region

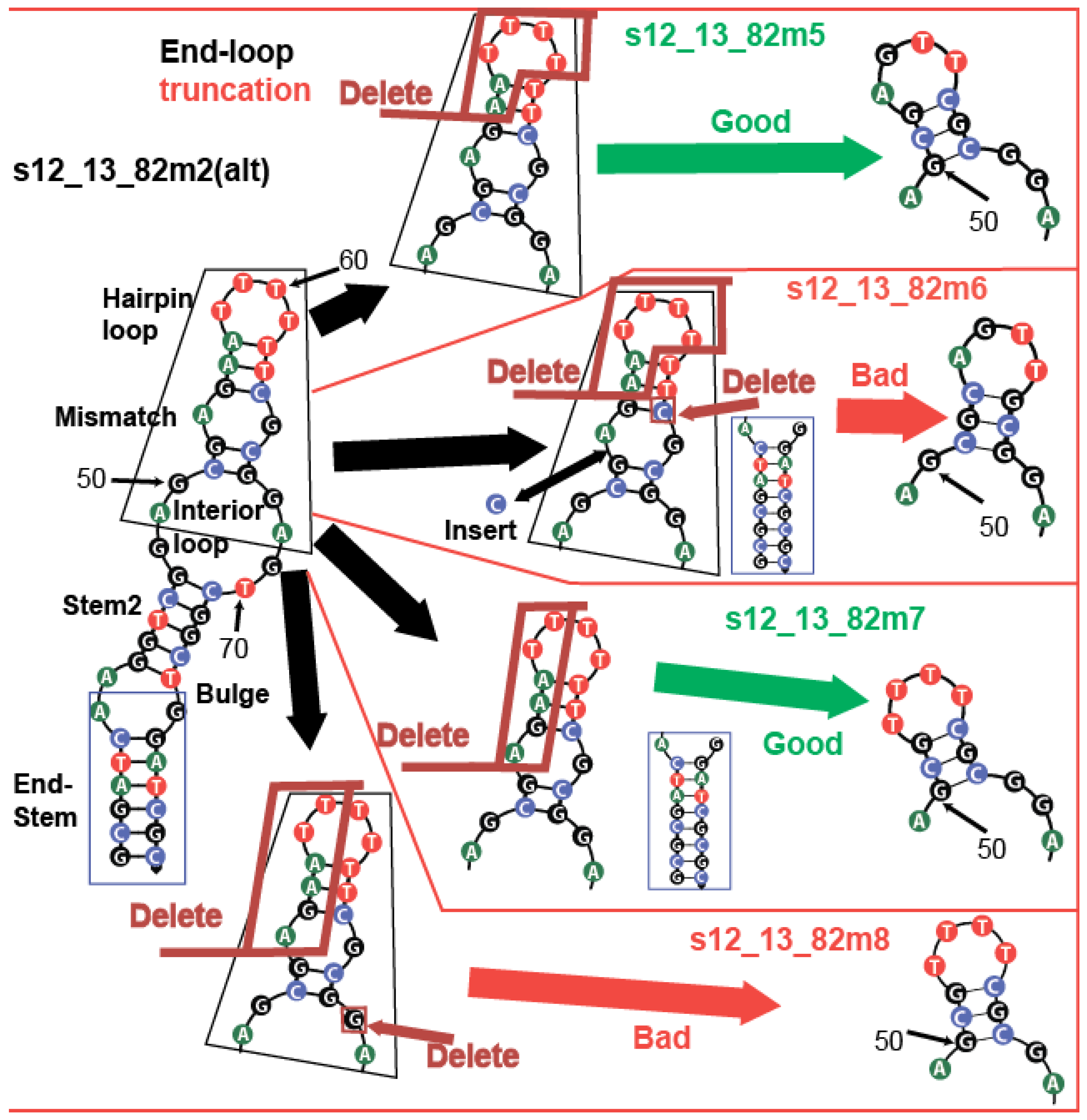

2.3.2. The Modification of the Aptamer Hairpin and Interior Loop Organization

2.4. Modification of Kanamycin Aptamer of Sequences

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Sample Preparation

3.2. The Measurements of KD for Kanamycin-Binding Aptamers Using ITC

3.3. Circular Dichroism Spectra Measurements at Equilibrium

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MST | Microscale thermophoresis |

| ITC | Isothermal titration calorimetry |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| KANA | Kanamycin A |

| SB | Selection buffer |

| BB | Binding buffer |

References

- Yang, L.F.; Ling, M.; Kacherovsky, N.; Pun, S.H. Aptamers 101: Aptamer discovery and in vitro applications in biosensors and separations. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 4961–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsicova, M.; Korcekova, J.; Poturnayova, A.; Breier, A. New Insights into Aptamers: An Alternative to Antibodies in the Detection of Molecular Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberger, M.; Gadermaier, G. SELEX: Critical factors and optimization strategies for successful aptamer selection. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 1771–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhu, J.; Shen, G.; Deng, Y.; Geng, X.; Wang, L. Improving aptamer performance: Key factors and strategies. Mikrochim. Acta 2023, 190, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Duan, N.; Khan, I.M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z. Strategies to manipulate the performance of aptamers in SELEX, post-SELEX and microenvironment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 55, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, S.C.B.; Lakshmipriya, T.; Md Arshad, M.K.; Voon, C.H.; Adam, T.; Hashim, U.; Singh, H.; Chinni, S.V. Shortening full-length aptamer by crawling base deletion–Assisted by Mfold web server application. J. Assoc. Arab. Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 23, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaiyum, Y.A.; Hoi Pui Chao, E.; Dhar, L.; Shoara, A.A.; Nguyen, M.D.; Mackereth, C.D.; Dauphin-Ducharme, P.; Johnson, P.E. Ligand-Induced Folding in a Dopamine-Binding DNA Aptamer. Chembiochem 2024, 25, e202400493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canovas, R.; Daems, E.; Campos, R.; Schellinck, S.; Madder, A.; Martins, J.C.; Sobott, F.; De Wael, K. Novel electrochemiluminescent assay for the aptamer-based detection of testosterone. Talanta 2022, 239, 123121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Zhao, J.; Liu, N.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Li, C.; Liu, M. Structure-guided post-SELEX optimization of an ochratoxin A aptamer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5963–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Liu, M. Structural basis for high-affinity recognition of aflatoxin B1 by a DNA aptamer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 7666–7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Kondo, S. Kanamycin and its derivative, arbekacin: Significance and impact. J. Antibiot. 2018, 71, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Li, F.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y. Degradation of kanamycin from production wastewater with high-concentration organic matrices by hydrothermal treatment. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 97, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Karasawa, T.; Steyger, P.S. Aminoglycoside-Induced Cochleotoxicity: A Review. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021 (WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1035. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/351172 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on Pharmacologically Active Substances and Their Classification Regarding Maximum Residue Limits in Foodstuffs of Animal Origin. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2010/37(1)/oj/eng (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Song, K.M.; Cho, M.; Jo, H.; Min, K.; Jeon, S.H.; Kim, T.; Han, M.S.; Ku, J.K.; Ban, C. Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric detection of kanamycin using a DNA aptamer. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 415, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenburg, R.; Nikolaus, N.; Strehlitz, B. Capture-SELEX: Selection of DNA Aptamers for Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. J. Anal Methods Chem. 2012, 2012, 415697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, A.A.; Rangel, A.E.; Feagin, T.A.; Lowery, R.G.; Argueta-Gonzalez, H.S.; Heemstra, J.M. RE-SELEX: Restriction enzyme-based evolution of structure-switching aptamer biosensors. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 11692–11702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. pH-Directed Capture-SELEX for Nanomolar Affinity Aptamers for Kanamycin Detection. Anal. Sens. 2024, 5, e202400099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A.A.; Miller, E.A.; Plaxco, K.W. Reagentless measurement of aminoglycoside antibiotics in blood serum via an electrochemical, ribonucleic acid aptamer-based biosensor. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 7090–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.; Chun, S.M.; Jeong, S.; Yu, J. In vitro selection of RNA against kanamycin B. Mol. Cells 2001, 11, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornace, M.E.; Huang, J.; Newman, C.T.; Porubsky, N.J.; Pierce, M.B.; Pierce, N.A. NUPACK: Analysis and design of nucleic acid structures, devices, and systems. ChemRxiv 2022. Available online: https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/636c7089b588507d0045f283 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Samokhvalov, A.V.; Maksimenko, O.G.; Eremin, S.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Interactions of Ligand, Aptamer, and Complementary Oligonucleotide: Studying Impacts of Na+ and Mg2+ Cations on Sensitive FRET-Based Detection of Aflatoxin B1. Molecules 2025, 30, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.; Abian, O.; Johnson, C.M.; Ferreira-da-Silva, F.; Vega, S.; Jimenez-Alesanco, A.; Ortega-Alarcon, D.; Velazquez-Campoy, A. Isothermal titration calorimetry. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubova, E.A.; Strelnikov, I.A. Experimental detection of conformational transitions between forms of DNA: Problems and prospects. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1053–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorlickova, M.; Kejnovska, I.; Bednarova, K.; Renciuk, D.; Kypr, J. Circular dichroism spectroscopy of DNA: From duplexes to quadruplexes. Chirality 2012, 24, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.A.; Pei, R.; Stojanovic, M.N. In vitro selection and amplification protocols for isolation of aptameric sensors for small molecules. Methods 2016, 106, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhao, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Liu, M. Structural Insights into the Mechanism of High-Affinity Binding of Ochratoxin A by a DNA Aptamer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7731–7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzynska, J.; Popenda, M.; Antczak, M.; Szachniuk, M. RNA tertiary structure prediction using RNAComposer in CASP15. Proteins 2023, 91, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Olson, W.K.; Lu, X.J. Web 3DNA 2.0 for the analysis, visualization, and modeling of 3D nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W26–W34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Hoyer, S.; Chou, W.; McLean, C.; Davis, G.; Gong, Q.; Armstrong, Z.; Jang, J.; et al. Machine learning guided aptamer refinement and discovery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Tobia, J.; Huang, P.J.; Ding, Y.; Saran Narayan, R.; Narayan, A.; Liu, J. Machine Learning Directed Aptamer Search from Conserved Primary Sequences and Secondary Structures. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousivand, M.; Bagherzadeh, K.; Anfossi, L.; Javan-Nikkhah, M. Key criteria for engineering mycotoxin binding aptamers via computational simulations: Aflatoxin B1 as a case study. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 17, e2100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Duan, N.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, P.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z. High-affinity aptamer of allergen β-lactoglobulin: Selection, recognition mechanism and application. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 340, 129956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, N.; Strehlitz, B. DNA-Aptamers Binding Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Sensors 2014, 14, 3737–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indications | Aptamers (5′-3′) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s11*_Kana2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| C | A | C | C | T | A | A | T | A | C | G | A | C | T | C | A | C | T | A | T | A | G | C | G | G | A | T | C | C | G | A | A | G | A | T | G | G | G | G | G | T | T | |

| 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | |

| G | A | G | G | C | T | A | A | G | C | C | G | A | C | C | G | T | A | A | G | T | T | G | G | G | C | C | G | T | C | T | G | G | C | T | C | G | A | A | C | A | A | |

| 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| G | C | T | T | G | C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| s12_13_82 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| A | T | A | C | C | A | G | C | T | T | A | T | T | C | A | A | T | T | C | A | G | G | G | C | G | G | T | A | T | G | A | G | G | C | T | C | G | A | T | C | A | A | |

| 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | |

| G | G | T | C | G | G | A | G | C | G | A | G | A | A | T | T | T | T | T | T | C | G | C | G | G | A | G | T | C | G | G | C | T | G | G | A | T | C | A | G | A | T | |

| 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | G | T | A | A | G | T | G | C | A | A | T | C | T | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| s21_K16 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| C | G | C | A | T | A | C | C | A | G | C | T | T | A | G | T | T | C | A | G | A | A | T | T | C | A | T | T | G | G | A | G | C | G | T | G | G | C | G | T | G | G | |

| 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | |

| A | T | G | C | C | C | G | A | T | G | A | A | C | C | G | C | C | C | C | A | G | G | G | T | G | C | A | G | A | T | A | G | T | A | A | G | T | G | C | A | A | T | |

| 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | T | C | G | G | C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| s25_Kana6-1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| G | A | C | G | A | C | G | A | G | G | G | C | C | T | G | A | A | A | C | T | T | G | C | T | G | G | A | A | C | G | G | T | T | A | A | A | G | T | C | G | T | C | |

| s25_Kana6-5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 |

| G | A | C | G | A | C | G | C | A | G | T | T | G | G | C | T | T | A | G | C | G | T | A | G | G | T | A | A | A | G | G | T | C | G | A | T | G | T | C | G | T | C | |

| Isothermal Calorimetry | 2 KD (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer | Medium | N | ∆H (kcal/mol) | ∆S × T (kcal/mol) | ∆G (kcal/mol) | KD (μM) | |

| s11_Kana2 | SB1 | NA 1 | −0.4 | NA | ~0.08 (FAM-labeled aptamer to target-immobilized beads) [16] | ||

| s12_13_82 | SB2 | 0.91 | −21.7 ± 0.5 | −13.3 | −8.42 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 5.1 (ligand-induced displacement of FAM-labeled aptamer) [17] |

| BB | 1.02 | −21.9 ± 0.4 | −13.3 | −8.64 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | ||

| s21_K16 | SB2 | NA | 1.4 | NA | 340 (MST) [18] | ||

| s25_Kana6-1 | SB3 | 0.95 | −23.1 ± 0.7 | −15.4 ± 0.6 | −7.7 | 2.23 ± 0.24 | 0.32 ± 0.1 (ITC) [19] |

| s25_Kana6-5 | 0.90 | −32.4 ± 0.2 | −24.2 | −8.28 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.02 (ITC) [19] | |

| Isothermal Calorimetry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer | Medium | N | ∆H (kcal/mol) | ∆S × T (kcal/mol) | ∆G (kcal/mol) | KD (nM) |

| s12_13_82m1 | BB | 1.03 | −24.2 ± 0.2 | −14.7 | −9.60 | 96 ± 8.7 |

| 12_13_82m2 | 1.07 | −22.2 ± 0.2 | −12.6 | −9.54 | 101 ± 8.0 | |

| s12_13_82m4 | 1.03 | −22.6 ± 0.4 | −13.5 | −9.15 | 199 ± 24.9 | |

| Isothermal Calorimetry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer | Medium | N | ∆H (kcal/mol) | ∆S × T (kcal/mol) | ∆G (kcal/mol) | KD (nM) |

| s12_13_82m5 | BB | 0.99 | −23.1 ± 0.3 | −13.6 | −9.52 | 106 ± 8.7 |

| 12_13_82m6 | 0.99 | −15.9 ± 0.4 | −7.34 | −8.58 | 519 ± 48.4 | |

| s12_13_82m7 | 0.98 | −24.5 ± 0.3 | −15.0 | −9.50 | 109 ± 14.9 | |

| 12_13_82m8 | 0.90 | −18.5 ± 0.7 | −10.8 | −7.76 | 2200 ± 352 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samokhvalov, A.V.; Maksimenko, O.G.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Design and Characterization of Aptamers to Antibiotic Kanamycin with Improved Affinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211234

Samokhvalov AV, Maksimenko OG, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Design and Characterization of Aptamers to Antibiotic Kanamycin with Improved Affinity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211234

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamokhvalov, Alexey V., Oksana G. Maksimenko, Anatoly V. Zherdev, and Boris B. Dzantiev. 2025. "Design and Characterization of Aptamers to Antibiotic Kanamycin with Improved Affinity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211234

APA StyleSamokhvalov, A. V., Maksimenko, O. G., Zherdev, A. V., & Dzantiev, B. B. (2025). Design and Characterization of Aptamers to Antibiotic Kanamycin with Improved Affinity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211234