Abstract

Among the highly toxic heavy metals, cadmium (Cd) is highlighted as a persistent environmental pollutant, posing serious threats to plants and broader ecological systems. Phytochelatins (PCs), which are synthesized by phytochelatin synthase (PCS), are peptides that play a central role in Cd mitigation through metal chelation and vacuolar sequestration upon formation of Cd-PC complexes. PC synthesis interacts with other cellular mechanisms to shape detoxification outcomes, broadening the functional scope of PCs beyond classical stress responses. Plant Cd-related processes have has been extensively investigated within this context. This perspective article presents key highlights of the panorama concerning strategies targeting the PC pathway and PC synthesis to manipulate Cd-exposed plants. It discusses multiple advances on the topic related to genetic manipulation, including the use of mutants and transgenics, which also covers gene overexpression, PCS-deficient and PCS-overexpressing plants, and synthetic PC analogs. A complementary bibliometric analysis reveals emerging trends and reinforces the need for interdisciplinary integration and precision in genetic engineering. Future directions include the design of multigene circuits and grafting-based innovations to optimize Cd sequestration and regulate its accumulation in plant tissues, supporting both phytoremediation efforts and food safety in contaminated agricultural environments.

1. Cadmium and Phytochelatins as Strategic Targets

Cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic pollutant for plants and other living organisms. This heavy metal poses serious risks to human health and is also one of the most extensively studied environmental factors in the field of abiotic stress within the plant research context, frequently occurring under various agricultural conditions (see articles we previously reviewed [1,2]). Here, phytochelatins (PCs), referred to as metal-binding compounds, are highlighted. They are cysteine-rich peptides regarded as key molecules in the detoxification of heavy metals in plants. In response to Cd exposure, plants synthesize PCs, which are able to chelate Cd ions in the cytosol, forming stable complexes. These complexes can then be transported into the vacuole. This mechanism helps lower the toxic concentration of Cd in sensitive cellular compartments [3,4,5]. As such, both the synthesis and chelation capacity of PCs are closely linked to how plants modulate their tolerance and response to Cd upon different experimental settings.

Phytochelatin synthase (PCS) in turn is the key enzyme in the biosynthesis of PCs, catalyzing their formation from the precursor glutathione (GSH) through a transpeptidation reaction involving the polymerization of GSH molecules. PCS activity can be triggered by the presence of heavy metal ions, with Cd recognized as a particularly strong inducer. Its enzymatic activity and gene expression are regulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels in response to metal exposure and other conditions (see information previously reviewed [3,4,5]). Given its crucial role in metal detoxification, PCS holds significant potential for use in genetic manipulation and genetic engineering applications within the context of heavy metal mitigation.

Considering the growing concern over Cd contamination in agricultural systems and its impact on food safety, there is an increasing demand for innovative and relevant strategies to modulate plant tolerance and control the metal accumulation, along with other relevant topics regarding Cd mitigation. PC and their biosynthetic enzyme, as further presented in the following section, play important roles in Cd detoxification, making them strategic targets for both basic and applied research. This article aims to provide information on the current knowledge of PC-related genetic manipulation to explore how these approaches, along with relevant genetic engineering strategies, may contribute to Cd mitigation in plants, particularly through the enzyme involved. By integrating relevant insights, this paper offers a perspective on the potential of PC-centered approaches in plant biotechnology, also highlighting future research directions in this field.

2. Advances in Phytochelatin Synthase Research and Plant Genetic Manipulation

The use of genetic manipulation and various approaches, including mutagenesis and genetic engineering, has established PCS as a relevant and promising genetic target in order to investigate plants with differential tolerance and accumulation of Cd within the context of PCS synthesis. Among such experimental approaches, the use of PCS-deficient mutants, transgenic lines with PCS overexpression, and studies that combine both strategies have stood out, in addition to silencing-focused techniques (which include genetic manipulation through RNA interference and virus-induced gene silencing). These approaches have been applied across different Cd-exposed plant species. This includes model organisms such as Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), as well as crop species like rice (Oryza sativa) and approaches that simultaneously employ both mutants and overexpressing lines (such as the complementation of the cad1-3 mutant with heterologous PCS genes) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of functional genetic manipulations for Cd mitigation in plants, focusing on PCS-related insights and modulation of PC synthesis.

The study of PCS-deficient mutants, such as the well-characterized cad1-3 mutant of Arabidopsis (described as deficient in PCS1, containing a defective AtPCS1 gene), has provided early and robust evidence for the importance of PCS in Cd detoxification. The hypersensitivity of these mutants to Cd directly demonstrated the role of PCS in protecting cells against the toxicity of this metal. Comparing the behavior of cad1-3 mutants to wild-type plants under Cd exposure made it possible to determine the extent of PCs’ contribution to Cd tolerance and accumulation. Although PCS mutants in general are more sensitive to Cd, many still exhibit some level of tolerance at low concentrations, suggesting the existence of additional metal defense mechanisms [6,7,8,10,13,21].

In transgenic plants, while PCS overexpression has, in some cases, led to increased Cd tolerance and accumulation, other studies have reported hypersensitivity (Table 1), indicating that the homeostasis of PCs is finely regulated. Furthermore, different studies have speculated and suggested various reasons for such sensitivity [15,40], which may result from PC toxicity at high concentrations, cytosolic accumulation of PC–Cd complexes exceeding vacuolar sequestration capacity, depletion of GSH, or oxidative stress; and alternatively, excess PCs may be toxic or interfere with alternative detoxification pathways [78].

To provide a clearer understanding of PC-mediated detoxification, it is crucial to distinguish between the regulation of PCS gene expression, the actual enzymatic activity of the PCS protein, and the subsequent localization and transport of the synthesized PCs. While PCS gene expression is inducible by heavy metals and exhibits differential spatial and temporal patterns, the activity of the PCS enzyme, which catalyzes PC synthesis from the precursor GSH, is directly triggered by metal ions. Following their synthesis in the cytosol, PCs chelate metals, and the resulting complexes must be transported into the vacuole for effective sequestration (see information previously reviewed [3,4,5]). Crucially, simply increasing PCS gene expression or enzyme activity does not guarantee effective detoxification if downstream processes, such as GSH availability or the capacity for vacuolar transport, are limiting. In fact, existing studies demonstrate that PCs play a crucial role in the plant response to Cd, influencing not only tolerance but also the accumulation and translocation of the metal. Even so, PCS overexpression does not always lead to consistent, desirable, or positive effects, due to aspects such as the complexity of interactions among different enzyme isoforms, metal transport, and the cellular compartmentalization of Cd-PC complexes (Table 1).

Moreover, Gong et al. [13] and Chen et al. [82], using different experimental approaches (transgenic expression and grafting, respectively) and cad1-3 plants, provided key evidence supporting the property of PCs to be translocated within plants, their long-distance transport, and their role in the movement and potential detoxification of heavy metals such as Cd. These strategies offer valuable insight into the role of PCS in vivo, but caution is also necessary due to potential pleiotropic effects and agronomic impacts. Although increased Cd tolerance and certain integrative aspects (which includes the modulation of Cd accumulation) may occur, they do not always lead to improvements in desirable agronomic traits or meet agricultural expectations, as we previously discussed [1].

3. Research Avenues and Approaches in PC-Related Genetic Manipulation

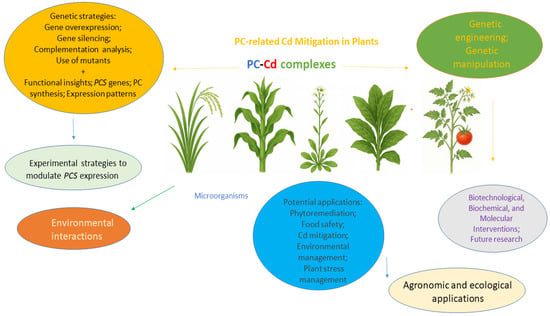

This section outlines key research avenues and emerging perspectives on the use of genetic manipulation strategies to enhance PC-mediated Cd mitigation in plants. An overview of the main approaches investigated to date on this research theme is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of PC-related Cd mitigation research in plants employing genetic manipulation strategies.

Other authors have also demonstrated the promising use of synthetic molecules and PC analogs in genetically modified plants as relevant biotechnological tools for research on heavy metal tolerance and remediation [83,84,85]. Postrigan et al. [83] designed and expressed a synthetic pseudophytochelatin gene in tobacco, observing increased resistance to Cd and enhanced accumulation of the metal in the aerial parts. In turn, Zheng et al. [84] investigated a PC-like gene (PCL) encoding a peptide with an α-Glu-Cys linkage, showing improved performance of transgenic tobacco plants under Cd2+ stress and greater Cd accumulation, mainly in the roots. The localization of PCL in the cytoplasm and nucleus suggests potential involvement in various physiological processes. Additionally, Vershinina et al. [85] generated transgenic tobacco plants expressing the pph6his gene, encoding a PC analog with an α-peptide linkage, which demonstrated stable growth in the presence of Cd and sufficient accumulation in the aerial tissue for Cd mitigation in the given research context. Optimizing the design of these synthetic molecules and analogs with different structures and sizes, exploring regulable and reusable expression systems to enhance phytoremediation efficiency, investigating the transport and complexation mechanisms of these peptides in various plant species and their relevance for Cd mitigation in different agricultural contexts, conducting direct comparative studies between different PC analogs and PCS, evaluating their effectiveness under field conditions and with various types of contamination, as well as analyzing and comparing their short and long-term effects on ecosystems are key perspectives for this research field.

Although PCS1 has historically been the primary focus in this research field, investigations have also explored the role of PCS2 in metal responses under various conditions, including its ability to complement PCS1 function in deficient mutants [17] and the regulation of PCS2 in genetically engineered rice plants (Table 1). Indeed, despite assumptions about PCS1’s primary role in metal tolerance [9], other studies indicate that Arabidopsis thaliana PCS2 is constitutively active in vivo [59]. Additionally, the recent study by Li et al. [86] examines the use of both the cad1-3 mutant (linked to the PCS1 gene) and the pcs2 mutant (associated with PCS2) to further support the involvement of these genes in Cd tolerance. Their finding that the overexpression of either PCS1 or PCS2 in a wrky45 mutant background can restore the mutant’s tolerance to Cd stress suggests that both genes participate in the signaling pathway downstream of WRKY45. This evidence was observed in Arabidopsis thaliana [86]. Also, in addition to the localization in the cytosol, AtPCS2 was shown to be detected in the nucleus, besides being tightly regulated at the transcriptional level in Arabidopsis and potentially playing additional roles beyond PC biosynthesis [87]. Such a regulatory landscape is complex, marked by alternative splicing of genes like OsPCS2 [71], as well as varied expression patterns dependent on species, exposure time, and metal concentration [Table 1]. Moreover, studies involving the cad1-3 atpcs2-1 double mutant have shown phenotypes similar to cad1-3 and a lack of detectable PCs, indicating that the low residual PCS activity in cad1-3 is attributable to AtPCS2 [82]. Such findings highlight the ongoing effort to understand the individual and combined contributions of PCS1 and PCS2 isoforms in the complex plant response to metal stress, expanding our knowledge across different plant species as well.

Indeed, PCS2 has been investigated as a functional enzyme capable of mediating PC biosynthesis in response to Cd exposure to some extent, with apparent non-redundancy with AtPCS1 [9]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, however, its endogenous expression was notably low due to weak promoter activity and inefficient mRNA translation, limiting its ability to compensate for the Cd hypersensitivity observed in AtPCS1-deficient mutants like cad1-3 [17]. Despite this, AtPCS2 has shown constitutive PC-synthesizing activity and the capacity to increase Cd accumulation in cad1-3 mutants under certain conditions [59]. Studies using PCS2 genes from other species have yielded contrasting results; overexpression of MnPCS2 from mulberry in Arabidopsis enhanced Cd tolerance and accumulation [51], whereas AdPCS2 from Arundo donax led to increased Cd sensitivity, marked by reduced shoot biomass and chlorosis [52]. In rice, the functional isoform OsPCS2a, distinct from the non-functional OsPCS2b, has been shown to contribute to Cd tolerance and accumulation when expressed in yeast, and its grain-specific silencing via RNAi—alongside OsPCS1—reduces Cd accumulation in rice grains [71]. Moreover, OsPCS2 appears to be the predominant isozyme driving PC synthesis in roots under Cd stress, with its knockdown leading to lower root Cd and PC levels but only marginally affecting whole-plant Cd tolerance [74]. Despite these advances and the contrasting outcomes across species and genetic and experimental contexts, knowledge of PCS2 function within the genetic engineering and manipulation context remains limited to a few plant species and experimental setups, highlighting the need for broader and more systematic investigations as well as including more plant species.

PCS mutants, besides their role in metal detoxification, are involved in processes like nutrient dynamics and pathogen interactions (Table 1). For example, cad1-3 mutants show altered copper transport, revealing the link between PCs and other metal-binding proteins like metallothioneins (which also comprise other major classes of metal-binding molecules). The triple mutant mt1a-2 mt2b-1 cad1-3 (showing metallothionein deficiency combined with PC deficiency) exhibited increased sensitivity to Cd and copper, highlighting compensatory or additive roles of different molecules and their contribution to plant metal homeostasis [21]. PC-deficient mutants also have heightened susceptibility to pathogens, linking Cd stress to weakened defense mechanisms, besides exhibiting impaired callose deposition and lignification [31]. These findings suggest that PCS and PC play a broader role in both abiotic and biotic stress responses, besides providing insights into plant survival under combined metal and biotic stress. Future studies could also focus on understanding how PCS mutations and the use of PC-focused transgenes affect plant-pathogen interactions and identify potential compensatory mechanisms in a broader agricultural context.

The study by Cahoon et al. [28] offers a compelling foundation for future biotechnological strategies targeting metal stress tolerance. By using directed evolution, they generated PCS1 variants in Arabidopsis thaliana that, despite reduced catalytic efficiency, conferred enhanced Cd tolerance and accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Arabidopsis, and Brassica juncea. These findings suggest that PCS activity can be fine-tuned through targeted mutations, opening new avenues for engineering crops with improved detoxification capacity and resilience to heavy metal stress. Future research may build on this approach to design custom PCS alleles tailored to specific environmental challenges.

Recent investigations have expanded our understanding of PCS and its applications in enhancing Cd tolerance and mitigation in plants. For instance, Chen et al. [33] demonstrated that the heterologous co-overexpression of SpGSH1 and SpPCS1 from Spirodela polyrhiza enhances both Cd tolerance and accumulation more effectively than individual gene overexpression. In parallel, Gui et al. [78] engineered rice plants with reduced levels of arsenic and Cd in grains through the co-overexpression of OsPCS1, OsABCC1, and OsHMA3, revealing a synergistic reduction in metal accumulation without compromising plant growth. Additionally, Li et al. [86] identified the transcription factor AtWRKY45 as a positive regulator of Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis, acting via upregulation of PCS1 and PCS2 expression. Recent studies have also begun to elucidate how PC synthesis is modulated by hormonal cues and integrated with broader physiological responses to Cd stress. Xing et al. [81] for example provided compelling evidence that melatonin enhances Cd tolerance in tomato not only by mitigating oxidative damage but also by directly regulating PC biosynthesis. Using gene silencing of PCS and COMT (caffeic acid O-methyltransferase), the authors demonstrated that endogenous melatonin levels and PC content are both upregulated under Cd stress, and that melatonin-deficient plants are more susceptible to metal toxicity. These findings highlight a hormonal regulatory layer that influences the antioxidant system, redox homeostasis, nutrient absorption, and ultimately PC-mediated detoxification.

Notably, while OsPCS1 overexpression alone has been associated with Cd hypersensitivity in some experiments based on rice research [78], combinatorial strategies involving genes encoding metal transporters have shown promise in mitigating this sensitivity and limiting Cd accumulation in edible tissues. This reinforces the notion that multigenic engineering strategies, particularly those that integrate PCS overexpression with genes involved in vacuolar sequestration and long-distance transport, are crucial for balancing detoxification efficiency with agronomic performance.

In this context, mutants such as cad1-3 (defective in PCS1) and nramp3nramp4 (defective in vacuolar metal remobilization) have provided significant mechanistic insights. As shown by Molins et al. [24], both mutants display enhanced Cd sensitivity, yet their physiological responses diverge under stress. For instance, nramp3nramp4 exhibits severe damage to the photosynthetic apparatus under Cd exposure, a phenotype not equally observed in cad1-3. These findings suggest that vacuolar metal stores play a critical role in safeguarding plastid function during Cd and oxidative stress and highlight the necessity of exploring compensatory pathways when PCS function is impaired.

Taken together, these results underscore the importance of moving beyond single-gene approaches. Future research should prioritize integrative strategies that combine PCS manipulation with regulators of redox homeostasis, vacuolar sequestration, and transcriptional control. The development of synthetic circuits or inducible systems might further fine-tune PC-related responses to Cd stress, minimizing unintended physiological trade-offs and optimizing plant resilience in contaminated environments. Also, such insights can pave the way for advanced bioengineering strategies that combine PC modulation with fine-tuned control over metal transport and distribution, maximizing both tolerance and food safety outcomes in Cd-contaminated environments. Importantly, the study underscores the interconnection between PC biosynthesis and multiple transport-related processes, suggesting that future efforts should explore the cross-talk between PCs and different transport systems, including vacuolar sequestration, long-distance translocation, and efflux mechanisms.

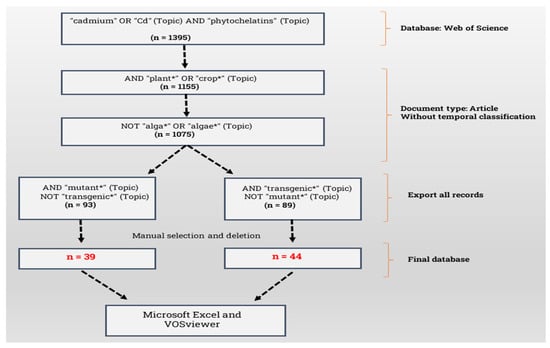

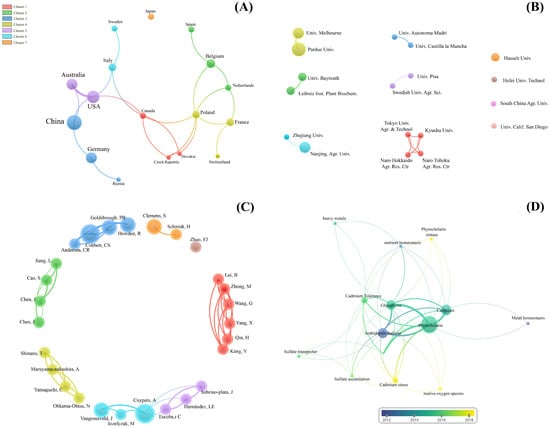

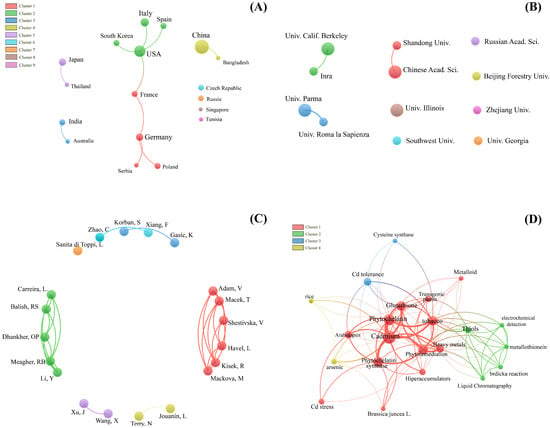

The bibliometric analysis we conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection provided a comprehensive overview of strategies involving PC synthesis in genetically modified plants under Cd stress. Supplementary Material S1 (which also includes Tables S1–S10) provides the full set of information related to this aspect. Using the VOSviewer software (version 1.6.15), we analyzed two subsets of publications: those involving mutants and those focusing on transgenic approaches. The search and filtering process is outlined in the flowchart in Figure 2, while Figure 3 and Figure 4 detail the collaboration networks among countries, institutions, and authors, as well as keyword co-occurrence patterns within each approach.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for searching and filtering articles on ‘phytochelatins’ and ‘cadmium’ in plants, focusing on studies with ‘mutants’ and ‘transgenics’. * Indicates inclusion and selection criteria used during filtering process.

Figure 3.

Bibliometric analysis of global participation and research collaboration networks by country (A), institutions (B), authors (C) and keyword co-occurrence network (D) in articles on ‘phytochelatins’ and ‘cadmium’ in plants, focusing on studies with ‘mutants’. The size of the circles represents the volume of publications or the frequency of keywords, while the thickness of the lines indicates the strength of the connections or collaborations between the elements analyzed.

Figure 4.

Bibliometric analysis of global participation and research collaboration networks by country (A), institutions (B), authors (C), and keyword co-occurrence network (D) in articles on ‘phytochelatins’ and ‘cadmium’ in plants, focusing on studies with ‘transgenics’. The size of the circles represents the volume of publications or the frequency of keywords, while the thickness of the lines indicates the strength of the connections or collaborations between the elements analyzed.

Our analysis revealed that research in this field extends beyond the classical phytochelatin synthase (PCS) pathway, with recurring terms such as “Glutathione”, “Cadmium”, and “Phytochelatin” pointing to broader strategies for responding to cadmium and other heavy metal stresses. There is a clear opportunity to deepen the integration of the PC pathway with antioxidant mechanisms (such as SOD, CAT, and POX) and with genes involved in Cd-related transport and sequestration (such as ZIP and ABC) (Supplementary Material S1), suggesting promising directions for developing plants with enhanced tolerance and accumulation capacities.

The collaboration networks highlight productive and influential clusters, whose thematic analysis may uncover innovative approaches—such as the modulation of Cd bioavailability in soil or interactions with associated microbiota. These insights increase and contribute to our understanding of effective strategies in genetically modified plants and encourage interdisciplinary practices in the field. Another key point is the frequent use of model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum, highlighting the need to expand research efforts to agriculturally relevant crops or species with high phytoremediation potential, which holds substantial practical value.

Importantly, we also suggest that future bibliometric analyses take into account not only the content but also the tone and context of the publications, aiming to identify whether a balanced view is presented between the reported benefits and the potential limitations or risks of genetically manipulating the PC pathway. This critical perspective is essential for guiding more mindful, integrated, and sustainable research in plant bioengineering, particularly in the face of heavy metal contamination and its relationship with PC synthesis.

4. Concluding Remarks and Additional Future Directions

With regard to future research and ongoing investigations involving PC synthesis, mutant and transgenic plants, and Cd exposure, the integration of diverse approaches is crucial for achieving a more comprehensive and practically relevant understanding. For instance, optimizing transgenic plants through the heterologous expression of PCS genes from various species—while also considering factors such as subcellular localization and metabolic balance—represents a promising avenue. Transferring these genetically modified plants into agricultural systems, with an emphasis on food safety, is a critical next step. Furthermore, future studies might prioritize a fuller picture and knowledge regarding tissue-specific analyses and the use of targeted promoters to enhance the precision of transgenic and genetic engineering approaches focused on PC and PCS.

The combination of tools such as transgenic plants with omics approaches, alongside advances in gene editing technologies like CRISPR/Cas9, opens up exciting possibilities for precise modifications of PCS-related pathways. In our research group, we have also been exploring grafting as a strategy to modulate Cd tolerance. Grafting emerges as a powerful methodological innovation to dissect the specific contributions of root and shoot systems in response to Cd exposure, enabling investigations into inter-organ signaling and the modulation of metal accumulation in targeted tissues.

We have been working on the integration of grafting [1,2] with omics approaches [1,88,89] in plants, which potentially can help uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying Cd tolerance and transport related to PC synthesis. These different perspectives align with the future directions we have discussed, highlighting the importance of refining transgenic approaches, manipulating transcription factors, and applying grafting techniques to drive more robust advancements in engineering Cd-tolerant plants.

There is also a clear need for more comprehensive studies that simultaneously assess Cd accumulation, growth and productivity parameters, and the underlying mechanisms of tolerance and response. Broadening the focus to include other cellular components involved in metal homeostasis—such as ABC (ATP-binding cassette transporters) transporters and transcription factors—is equally essential.

Combining genetic manipulation of the PC pathway with agronomic strategies to modulate systemic responses holds strong potential to drive significant progress in both phytoremediation efforts and the production of safe food.

From the integrated analysis of available studies, a clear direction emerges: the development of multi-target precision engineering approaches. These would combine targeted gene editing of specific PCS isoforms with the simultaneous modulation of key genes involved in the transport and compartmentalization of Cd-PC complexes. The studies summarized in the Table also reveal inconsistent patterns of Cd accumulation and tolerance depending on genetic, tissue-specific, and metabolic contexts, highlighting that simple PCS overexpression is often insufficient to ensure consistent responses.

The given information reinforces the need for modular editing systems capable of fine-tuning not only PCS levels but also genes such as ABCC1/2/3, HMA2/4, and redox-related elements like GSH1 and YCF1, depending on the plant species, target organ, and intended goal (phytoremediation vs. food safety). Technologies such as multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 and expression vectors with tissue-specific and/or stress-inducible promoters offer the level of precision required for such strategies.

Moreover, applying these approaches in model platforms—such as transgenic lines grafted with cultivated plant tissues—could serve as a valuable translational validation system before deploying them in economically relevant food crops. These proposals point toward a future where Cd tolerance can be modulated in a dynamic, efficient, and highly specific manner, tailored to the ecological and agricultural demands of each unique scenario.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms26104767/s1.

Author Contributions

D.N.M.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Visualization. C.C.T.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. R.A.A.: Supervision, Resources, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP [grant numbers 2020/12666-7 and 2022/11018–7 to DNM] (from Brazil).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marques, D.N.; Mason, C.; Stolze, S.C.; Harzen, A.; Nakagami, H.; Skirycz, A.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Grafting systems for plant cadmium research: Insights for basic plant physiology and applied mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, D.N.; Nogueira, M.L.; Gaziola, S.A.; Batagin-Piotto, K.D.; Freitas, N.C.; Alcantara, B.K.; Paiva, L.V.; Mason, C.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. New insights into cadmium tolerance and accumulation in tomato: Dissecting root and shoot responses using cross-genotype grafting. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seregin, I.V.; Kozhevnikova, A.D. Phytochelatins: Sulfur-Containing Metal(loid)-Chelating Ligands in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, M.; Alam, P.; Hussain, A.; Karabulut, F.; Haque Tonny, S.; Cheng, S.H.; Yusuf, M.; Adil, M.F.; Sehar, S.; Alomrani, S.O.; et al. Phytochelatins: Key Regulator Against Heavy Metal Toxicity in Plants. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.N.; Gaziola, S.A.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Phytochelatins: Advances in Tomato Research. Agronomy 2025, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, R.; Cobbett, C.S. Cadmium-sensitive mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1992, 100, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howden, R.; Goldsbrough, P.B.; Andersen, C.R.; Cobbett, C.S. Cadmium-Sensitive, cad1 Mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana Are Phytochelatin Deficient. Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-B.; Smith, A.P.; Howden, R.; Dietrich, W.M.; Bugg, S.; O’Connell, M.J.; Goldsbrough, P.B.; Cobbett, C.S. Phytochelatin Synthase Genes from Arabidopsis and the Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazalé, A.C.; Clemens, S. Arabidopsis thaliana expresses a second functional phytochelatin synthase. FEBS Lett. 2001, 507, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, E.H.; Asp, H.; Bornman, J.F. Influence of prior Cd2+ exposure on the uptake of Cd2+ and other elements in the phytochelatin-deficient mutant, cad1-3, of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Moon, J.S.; Domier, L.L.; Korban, S.S. Molecular characterization of phytochelatin synthase expression in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, C.; Ros, R.; De Haro, A.; Walker, D.J.; Bernal, M.P.; Serrano, R.; Navarro-Aviñó, J. A plant genetically modified that accumulates Pb is especially promising for phytoremediation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 303, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.-M.; Lee, D.A.; Schroeder, J.I. Long-distance root-to-shoot transport of phytochelatins and cadmium in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10118–10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Petros, D.; Moon, J.S.; Ko, T.S.; Goldsbrough, P.B.; Korban, S.S. Higher levels of ectopic expression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase do not lead to increased cadmium tolerance and accumulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 41, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Moon, J.S.; Ko, T.S.; Petros, D.; Goldsbrough, P.B.; Korban, S.S. Overexpression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase paradoxically leads to hypersensitivity to cadmium stress. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dhankher, O.P.; Carreira, L.; Lee, D.; Chen, A.; Schroeder, J.I.; Balish, R.S.; Meagher, R.B. Overexpression of Phytochelatin Synthase in Arabidopsis Leads to Enhanced Arsenic Tolerance and Cadmium Hypersensitivity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kang, B.S. Expression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase 2 is too low to complement an AtPCS1-defective Cad1-3 mutant. Mol. Cells 2005, 19, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovet, L.; Eggmann, T.; Meylan-Bettex, M.; Polier, J.; Kammer, P.; Marin, E.; Feller, U.; Martinoia, E. Transcript levels of AtMRPs after cadmium treatment: Induction of AtMRP3. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kang, B.S. Phytochelatin Is Not a Primary Factor in Determining Copper Tolerance. J. Plant Biol. 2005, 48, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.E.; Cobbett, C.S. HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.J.; Meetam, M.; Goldsbrough, P.B. Examining the specific contributions of individual Arabidopsis metallothioneins to copper distribution and metal tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennstedt, P.; Peisker, D.; Böttcher, C.; Trampczynska, A.; Clemens, S. Phytochelatin synthesis is essential for the detoxification of excess zinc and contributes significantly to the accumulation of zinc. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Song, W.Y.; Ko, D.; Eom, Y.; Hansen, T.H.; Schiller, M.; Lee, T.G.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. The phytochelatin transporters AtABCC1 and AtABCC2 mediate tolerance to cadmium and mercury. Plant J. 2012, 69, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molins, H.; Michelet, L.; Lanquar, V.; Agorio, A.; Giraudat, J.; Roach, T.; Krieger-Liszkay, A.; Thomine, S. Mutants impaired in vacuolar metal mobilization identify chloroplasts as a target for cadmium hypersensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, N.; Rahman, A.; Moś, M.; Warzecha, T.; Ghosh, S.; Hossain, K.; Nawani, N.N.; Mandal, A. In silico and in vivo studies of molecular structures and mechanisms of AtPCS1 protein involved in binding arsenite and/or cadmium in plant cells. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino-Plata, J.; Carrasco-Gil, S.; Abadía, J.; Escobar, C.; Álvarez-Fernández, A.; Hernández, L.E. The role of glutathione in mercury tolerance resembles its function under cadmium stress in Arabidopsis. Metallomics 2014, 6, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, P.; Zanella, L.; De Paolis, A.; Di Litta, D.; Cecchetti, V.; Falasca, G.; Barbieri, M.; Altamura, M.M.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. Cadmium-inducible expression of the ABC-type transporter AtABCC3 increases phytochelatin-mediated cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3815–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, R.E.; Lutke, W.K.; Cameron, J.C.; Chen, S.; Lee, S.G.; Rivard, R.S.; Rea, P.A.; Jez, J.M. Adaptive Engineering of Phytochelatin-based Heavy Metal Tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 17321–17330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnlenz, T.; Hofmann, C.; Uraguchi, S.; Schmidt, H.; Schempp, S.; Weber, M.; Lahner, B.; Salt, D.E.; Clemens, S. Phytochelatin Synthesis Promotes Leaf Zn Accumulation of Arabidopsis thaliana Plants Grown in Soil with Adequate Zn Supply and is Essential for Survival on Zn-Contaminated Soil. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, H.; Vangronsveld, J.; Cuypers, A. Cd-induced Cu deficiency responses in Arabidopsis thaliana: Are phytochelatins involved? Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, M.; Brunetti, C.; Brauer, E.K.; Andreucci, A.; Popescu, S.C.; Commisso, M.; Guzzo, F.; Sofo, A.; Ruffini Castiglione, M.; Vatamaniuk, O.K.; et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana Knockout Mutant for Phytochelatin Synthase1 (cad1-3) Is Defective in Callose Deposition, Bacterial Pathogen Defense and Auxin Content, But Shows an Increased Stem Lignification. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.J. Protein phosphatase 2A alleviates cadmium toxicity by modulating ethylene production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1008–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Huang, S.B.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Gao, C.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhao, F.J. IAR4 mutation enhances cadmium toxicity by disturbing auxin homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutilleul, C.; Jourdain, A.; Bourguignon, J.; Hugouvieux, V. The Arabidopsis Putative Selenium-Binding Protein Family: Expression Study and Characterization of SBP1 as a Potential New Player in Cadmium Detoxification Processes. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picault, N.; Cazalé, A.C.; Beyly, A.; Cuiné, S.; Carrier, P.; Luu, D.T.; Forestier, C.; Peltier, G. Chloroplast targeting of phytochelatin synthase in Arabidopsis: Effects on heavy metal tolerance and accumulation. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, M.; Censi, V.; Di Girolamo, V.; De Paolis, A.; di Toppi, L.S.; Aromolo, R.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. Overexpression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase in tobacco plants enhances Cd2+ tolerance and accumulation but not translocation to the shoot. Planta 2006, 223, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzynski, A.; Kopera, E.; Wawrzynska, A.; Kaminska, J.; Bal, W.; Sirko, A. Effects of simultaneous expression of heterologous genes involved in phytochelatin biosynthesis on thiol content and cadmium accumulation in tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, M. Enhanced cadmium accumulation in transgenic tobacco expressing the phytochelatin synthase gene of Cynodon dactylon L. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006, 48, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S. Overexpression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase (atpcsi) does not change the maximum capacity for non-protein thiol production induced by Cadmium. J. Plant Biol. 2007, 50, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojas, S.; Clemens, S.; Hennig, J.; Sklodowska, A.; Kopera, E.; Schat, H.; Bal, W.; Antosiewicz, D.M. Overexpression of phytochelatin synthase in tobacco: Distinctive effects of AtPCS1 and CePCS genes on plant response to cadmium. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2205–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Dai, X.; Xu, W.; Ma, M. Overexpressing GSH1 and AsPCS1 simultaneously increases the tolerance and accumulation of cadmium and arsenic in Arabidopsis thaliana. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojas, S.; Ruszczyńska, A.; Bulska, E.; Clemens, S.; Antosiewicz, D.M. The role of subcellular distribution of cadmium and phytochelatins in the generation of distinct phenotypes of AtPCS1- and CePCS3-expressing tobacco. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 981–988. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, P.; Zanella, L.; Proia, A.; De Paolis, A.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M.M.; Sanità di Toppi, L.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. Cadmium tolerance and phytochelatin content of Arabidopsis seedlings over-expressing the phytochelatin synthase gene AtPCS1. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5509–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Chai, T.Y. Phytochelatin synthase of Thlaspi caerulescens enhanced tolerance and accumulation of heavy metals when expressed in yeast and tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, M. The assembly of metals chelation by thiols and vacuolar compartmentalization conferred increased tolerance to and accumulation of cadmium and arsenic in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 199, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gu, C.; Chen, F.; Yang, D.; Wu, K.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z. Heterologous expression of a Nelumbo nucifera phytochelatin synthase gene enhances cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Kesari, R.; Tiwari, M.; Dwivedi, S.; Tripathi, R.D.; Nath, P.; Trivedi, P.K. Expression of Ceratophyllum demersum phytochelatin synthase, CdPCS1, in Escherichia coli and Arabidopsis enhances heavy metal(loid)s accumulation. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, J. Overexpression of PtPCS enhances cadmium tolerance and cadmium accumulation in tobacco. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2015, 121, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.D.; Hwang, S. Tobacco phytochelatin synthase (NtPCS1) plays important roles in cadmium and arsenic tolerance and in early plant development in tobacco. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2015, 9, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, L.; Fattorini, L.; Brunetti, P.; Roccotiello, E.; Cornara, L.; D’Angeli, S.; Della Rovere, F.; Cardarelli, M.; Barbieri, M.; Sanità di Toppi, L.; et al. Overexpression of AtPCS1 in tobacco increases arsenic and arsenic plus cadmium accumulation and detoxification. Planta 2016, 243, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Guo, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Long, D.; Xiang, Z.; Zhao, A. Two mulberry phytochelatin synthase genes confer zinc/cadmium tolerance and accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis and tobacco. Gene 2018, 645, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Stragliati, L.; Bellini, E.; Ricci, A.; Saba, A.; Sanità di Toppi, L.; Varotto, C. Evolution and functional differentiation of recently diverged phytochelatin synthase genes from Arundo donax L. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5391–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Zou, T.; Lin, R.; Zheng, J.; Jian, S.; Zhang, M. Characterization of a phytochelatin synthase gene from Ipomoea pes-caprae involved in cadmium tolerance and accumulation in yeast and plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 155, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Shi, W.; Jie, Y. Overexpression of BnPCS1, a Novel Phytochelatin Synthase Gene From Ramie (Boehmeria nivea), Enhanced Cd Tolerance, Accumulation, and Translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 639189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.G.; Oliver, D.J. Leaf-targeted phytochelatin synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 44, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, B.B.; Vonderheide, A.P.; Gong, J.M.; Schroeder, J.I.; Shann, J.R.; Caruso, J.A. An HPLC-ICP-MS technique for determination of cadmium-phytochelatins in genetically modified Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2008, 861, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, D.; Kesari, R.; Mishra, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Tripathi, R.D.; Nath, P.; Trivedi, P.K. Expression of phytochelatin synthase from aquatic macrophyte Ceratophyllum demersum L. enhances cadmium and arsenic accumulation in tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Tiwari, M.; Tripathi, R.D.; Nath, P.; Trivedi, P.K. Synthetic phytochelatins complement a phytochelatin-deficient Arabidopsis mutant and enhance the accumulation of heavy metal(loid)s. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 434, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnlenz, T.; Schmidt, H.; Uraguchi, S.; Clemens, S. Arabidopsis thaliana phytochelatin synthase 2 is constitutively active in vivo and can rescue the growth defect of the PCS1-deficient cad1-3 mutant on Cd-contaminated soil. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4241–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnlenz, T.; Westphal, L.; Schmidt, H.; Scheel, D.; Clemens, S. Expression of Caenorhabditis elegans PCS in the AtPCS1-deficient Arabidopsis thaliana cad1-3 mutant separates the metal tolerance and non-host resistance functions of phytochelatin synthases. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rui, H.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Z.; Xia, Y.; Shen, Z. Overexpression of a Functional Vicia sativa PCS1 Homolog Increases Cadmium Tolerance and Phytochelatins Synthesis in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Le, S.; Zhao, Y. Overexpression of Three Duplicated BnPCS Genes Enhanced Cd Accumulation and Translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana Mutant cad1-3. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 102, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liang, M.; Li, A.; Wu, J. Overexpression of the maize phytochelatin synthase gene (ZmPCS1) enhances Cd tolerance in plants. Acta Physiol. Plant 2022, 44, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.S.; Ding, G.; Yi, H.Y.; Gong, J.M. Cloning and functional analysis of phytochelatin synthase gene from Sedum plumbizincicola. Plant Physiol. J. 2014, 50, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, M. RNA Interference-mediated Silencing of Phytochelatin Synthase Gene Reduce Cadmium Accumulation in Rice Seeds. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasic, K.; Korban, S.S. Expression of Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) plants enhances tolerance for Cd and Zn. Planta 2007, 225, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasic, K.; Korban, S.S. Transgenic Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) plants expressing an Arabidopsis phytochelatin synthase (AtPCS1) exhibit enhanced As and Cd tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 64, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramaiah, N.; Ramakrishna, S.V.; Sreevathsa, R. Overexpression of phytochelatin synthase (AtPCS) in rice for tolerance to cadmium stress. Biologia 2011, 66, 1060–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, C. Heteroexpression of the wheat phytochelatin synthase gene (TaPCS1) in rice enhances cadmium sensitivity. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2012, 44, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Xiang, F. Cloning and characterization of a Phragmites australis phytochelatin synthase (PaPCS) and achieving Cd tolerance in tall fescue. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Maiti, M.K. Identification of alternatively spliced transcripts of rice phytochelatin synthase 2 gene OsPCS2 involved in mitigation of cadmium and arsenic stresses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 94, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, S.; Kuramata, M.; Abe, T.; Takagi, H.; Ozawa, K.; Ishikawa, S. Phytochelatin synthase OsPCS1 plays a crucial role in reducing arsenic levels in rice grains. Plant J. 2017, 91, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uraguchi, S.; Tanaka, N.; Hofmann, C.; Abiko, K.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N.; Weber, M.; Kamiya, T.; Sone, Y.; Nakamura, R.; Takanezawa, Y.; et al. Phytochelatin Synthase has Contrasting Effects on Cadmium and Arsenic Accumulation in Rice Grains. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1730–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, S.; Ueda, Y.; Mukai, A.; Ochiai, K.; Matoh, T. Rice phytochelatin synthases OsPCS1 and OsPCS2 make different contributions to cadmium and arsenic tolerance. Plant Direct 2018, 2, e00034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.C.; Hwang, J.E.; Jiang, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Nguyen, X.C.; Kim, C.Y.; Chung, W.S. Functional characterisation of two phytochelatin synthases in rice (Oryza sativa cv. Milyang 117) that respond to cadmium stress. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Barbaro, E.; Bellini, E.; Saba, A.; Sanità di Toppi, L.; Varotto, C. Ancestral function of the phytochelatin synthase C-terminal domain in inhibition of heavy metal-mediated enzyme overactivation. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 6655–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Leso, M.; Buti, M.; Bellini, E.; Bertoldi, D.; Saba, A.; Larcher, R.; Sanità di Toppi, L.; Varotto, C. Phytochelatin synthase de-regulation in Marchantia polymorpha indicates cadmium detoxification as its primary ancestral function in land plants and provides a novel visual bioindicator for detection of this metal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Teo, J.; Tian, D.; Yin, Z. Genetic engineering low-arsenic and low-cadmium rice grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2143–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Rai, K.K.; Rai, S.K.; Pandey-Rai, S. Heterologous expression of cyanobacterial PCS confers augmented arsenic and cadmium stress tolerance and higher artemisinin in Artemisia annua hairy roots. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 15, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, N.; Zhang, A.; Tangnver, S.; Li, S.; Gao, C. Cloning ThPCS1 gene of Tamarix hispida to improve cadmium tolerance. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2021, 45, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Q.; Hasan, M.K.; Li, Z.; Yang, T.; Jin, W.; Qi, Z.; Yang, P.; Wang, G.; Ahammed, G.J.; Zhou, J. Melatonin-induced plant adaptation to cadmium stress involves enhanced phytochelatin synthesis and nutrient homeostasis in Solanum lycopersicum L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 456, 131670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Komives, E.A.; Schroeder, J.I. An Improved Grafting Technique for Mature Arabidopsis Plants Demonstrates Long-Distance Shoot-to-Root Transport of Phytochelatins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postrigan, B.N.; Knyazev, A.B.; Kuluev, B.R.; Yakhin, O.I.; Chemeris, A.V. Expression of the Synthetic Phytochelatin Gene in Tobacco. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 59, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X. Effects of Phytochelatin-like Gene on the Resistance and Enrichment of Cd²⁺ in Tobacco. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vershinina, Z.R.; Maslennikova, D.R.; Chubukova, O.V.; Khakimova, L.R.; Mikhaylova, E.V. Synthetic Pph6his Gene Confers Resistance to Cadmium Stress in Transgenic Tobacco. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mai, C.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Liang, C.; Wang, J. Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY45 confers cadmium tolerance via activating PCS1 and PCS2 expression. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Peng, J.; Zhang, G.; Yi, H.; Fu, Y.; Gong, J. Regulation of the Phytochelatin Synthase Gene AtPCS2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2013, 43, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.N.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Phosphoproteomics: Advances in Research on Cadmium-Exposed Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.N.; Gaziola, S.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Phytochelatins and their relationship with modulation of cadmium tolerance in plants. In Handbook of Bioremediation: Physiological, Molecular and Biotechnological Interventions; Hasanuzzaman, M., Prasad, M.N.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).