Abstract

The herpesviral nuclear egress represents an essential step of viral replication efficiency in host cells, as it defines the nucleocytoplasmic release of viral capsids. Due to the size limitation of the nuclear pores, viral nuclear capsids are unable to traverse the nuclear envelope without a destabilization of this natural host-specific barrier. To this end, herpesviruses evolved the regulatory nuclear egress complex (NEC), composed of a heterodimer unit of two conserved viral NEC proteins (core NEC) and a large-size extension of this complex including various viral and cellular NEC-associated proteins (multicomponent NEC). Notably, the NEC harbors the pronounced ability to oligomerize (core NEC hexamers and lattices), to multimerize into higher-order complexes, and, ultimately, to closely interact with the migrating nuclear capsids. Moreover, most, if not all, of these NEC proteins comprise regulatory modifications by phosphorylation, so that the responsible kinases, and additional enzymatic activities, are part of the multicomponent NEC. This sophisticated basis of NEC-specific structural and functional interactions offers a variety of different modes of antiviral interference by pharmacological or nonconventional inhibitors. Since the multifaceted combination of NEC activities represents a highly conserved key regulatory stage of herpesviral replication, it may provide a unique opportunity towards a broad, pan-antiherpesviral mechanism of drug targeting. This review presents an update on chances, challenges, and current achievements in the development of NEC-directed antiherpesviral strategies.

Keywords:

human pathogenic herpesviruses; cytomegalovirus (HCMV); essential steps of viral replication; viral nucleocytoplasmic capsid egress; nuclear egress complex (NEC); core and multicomponent NEC extensions; novel antiviral drug targeting; NEC-directed mode of action; strategies of antiviral drug development 1. Introduction

The family of Herpesviridae is characterized by a linear double-stranded DNA genome and a comparatively large size of membrane-enveloped particles comprising 100–300 nm [1]. All herpesviruses share a lifelong persistence within the host with extended latency periods and strongly reduced gene expression, followed by intermittent phases of reactivation causing recurrent symptoms [2,3]. With infection rates spanning approx. 60–95% in cases of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), and varicella zoster virus (VZV), herpesvirus infections affect the majority of adults worldwide [4,5]. Herpesviruses can be divided into subfamilies based on their morphology, genetics, and biological properties [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Alphaherpesvirinae (α) include herpes simplex viruses type 1 and type 2 (HSV-1/-2) and varicella zoster virus (VZV); Betaherpesvirinae (β) includes the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) as well as human herpesviruses types 6A, 6B, and 7 (HHV-6A, HHV-6B, HHV-7); and Gammaherpesvirinae (γ) includes Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV/HHV-4).

Within human pathogenic α-herpesviruses, VZV represents a major pathogen, which causes chickenpox (varicella) upon primary infection, followed by VZV persistence in a state of nonproductive latency in the nervous system of the immunocompetent host. Consequences of VZV reactivations are lesions known as shingles (zoster), which can cause severe neurological diseases, such as acute sequelae or persistent burning pain [12]. Representing the only approved vaccine against a human herpesvirus, recommended in Germany by the RKI since 2004, or internationally by the WHO, Zostavax® (live attenuated) and Shingrix® (subunit vaccine) prevent primary or secondary infection with VZV [13]. As far as clinically dominant β-herpesvirus infections are concerned, HCMV is mostly asymptomatic or associated with mild symptoms in immunocompetent individuals [14,15,16]. In immunocompromised patients, however, such as transplant recipients, cancer patients, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals [17,18], HCMV can provoke severe consequences. Importantly, congenital HCMV infection (cCMV) is considered as the most urgent medical problem to be addressed by the development of novel preventive remedies. Representing the far most frequent vertically transmitted viral pathogenic infection during pregnancy [19,20], HCMV causes a wide range of symptoms, in more than 25% of all infected babies if the cases of late-onset disease are included. Symptoms span from mild to severe or even life-threatening (with approx. 10% of stillbirths contained in the group of acutely symptomatic), and the main clinical problems manifest as hearing/vision loss, mental retardation, and microcephaly in the unborn [21,22,23]. Concerning major human γ-herpesvirus infections, EBV is extremely widespread in the adult human world population (>6 billion infected), and, especially in immunity-based risk constellations, is associated with various malignant tumors, including post-transplant B- and T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinoma [24,25,26].

While vaccination is only available against VZV, a number of antiviral drugs are in use against α- and β-herpesvirus infections. Most approved herpesviral therapeutics are nucleoside/nucleotide analogs or other compounds likewise affecting the viral genome replication. For HCMV, the gold standard is still ganciclovir (GCV) and its orally administrated, bioavailable prodrug valganciclovir (VGCV), representing two related acyclic guanosine analogs. Both are activated through monophosphorylation by one of the respective nucleoside-converting herpesviral kinases (i.e., thymidine kinase of α-herpesviruses, or protein kinase of β- and γ-herpesviruses), thus exerting a certain specificity for herpesvirus-infected cells [27,28]. Further inhibitors of herpesviral genome synthesis are the nucleotide analog cidofovir (CDV) and the pyrophosphate analog foscarnet (FOS), used as a second line of therapy for GCV-resistant infections [29,30]. Frequently occurring side effects of viral genome replication inhibitors include nephrotoxicity, myelotoxicity, and anemia [31,32,33]. Two recently added HCMV drugs are letermovir (LMV), which inhibits the viral terminase, and maribavir (MBV), which affects the viral kinase activity, both clinically approved during the last years. Of note, however, subunit pUL56 of the terminase complex, which is important for the processing and encapsidation of newly synthesized viral genomes [34], may acquire LMV-directed resistance mutations. LMV is currently limited to prophylactic use in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients [35,36]. Also, MBV treatment can lead to resistance formation based on gene mutations of the viral kinase pUL97 [37,38,39,40], so the clinically urgent need to resolve drug resistance issues still persists. Although MBV proved to be associated with a lower incidence of severe and treatment-limiting adverse events than standard GCV therapy [41], another limitation of MBV is the lack of an option to combine MBV treatment with GCV. Due to the fact that the target of MBV, pUL97, is necessary for the activating phosphorylation of GCV, an antagonistic drug interaction is predictive, which has actually also been confirmed experimentally [42]. Nevertheless, MBV is highly special in another aspect, as it represents the first approved kinase inhibitor in the entire field of antiviral therapy. Beyond that, by targeting the NEC-associated kinase pUL97, MBV also represents the first identified drug acting through a herpesviral nuclear egress-directed mechanism. Whether MBV, LMV, or any other novel drug in development may become helpful in cCMV therapy or prevention is still in question [43,44].

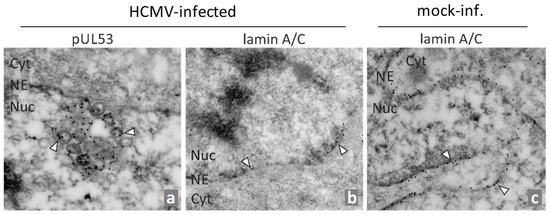

Thus, there is a need to identify new targets and treatment options in order to complement the currently available drugs and to improve anti-HCMV and further antiherpesviral treatment options. The process of nuclear capsid egress provides a rate-limiting step during viral replication, so it has been considered as a promising target, and has actually been experimentally validated in various aspects [45]. Since the diameter of newly assembled capsids (approximately 130 nm) prevents their exit via nuclear pores, a multifaceted, fine-regulated process is necessary for their nucleocytoplasmic transport [46,47,48,49]. A key element of the HCMV-specific nuclear egress complex (NEC) is the core NEC, consisting of the two viral proteins pUL50 and pUL53. This core NEC unites at least three major functions of nuclear egress, namely the recruitment of various NEC-associated effector proteins (multicomponent NEC), the reorganization of the nuclear lamina and membranes (nuclear rim distortion), and the interaction with nuclear capsids for nucleocytoplasmic transition (NEC–capsid docking). The individual stages of this process have been investigated by a variety of methodological approaches [50] and, in particular, electron microscopy (EM)-based techniques revealed highly interesting details. For HCMV, approaches of confocal imaging and immunogold EM labeling deciphered preferred sites of nuclear capsid egress, termed as lamina-depleted areas [51,52,53], as well as a pronounced intranuclear association of pUL53 with viral capsids [54,55], either in proximity or at a distance from the nuclear rim (Figure 1, image a). This accumulation of viral capsids was associated with a typical thinning of the lamina (Figure 1b, compared to c), as effected by site-specific phosphorylation and subsequently induced lamin A/C reorganization [51,56,57].

Figure 1.

Immunogold EM analysis of HCMV-infected primary human fibroblasts (HFFs). HFFs were infected with HCMV AD169 for 6 days (a,b) or remained uninfected (c), before cells were fixed, subjected to sectioning and immunogold staining for EM analysis. Immunostaining was performed for human nuclear lamin A/C or viral pUL53 as indicated. Individual gold particles were exemplarily marked by arrowheads. NE, nuclear envelope; Cyt, cytoplasm; Nuc, nucleus (modified from [54]).

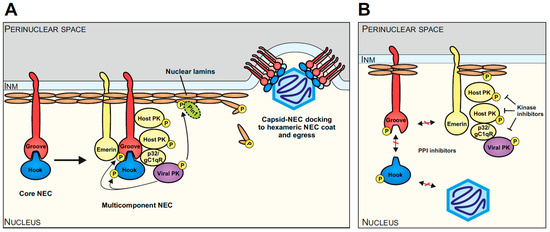

The herpesviral core NEC generally plays a central role in the multistep regulation of nuclear egress and recruits the multicomponent NEC. Interestingly, this extended complex also includes a number of host proteins, which fulfill important roles in the regulation of viral nuclear egress. In the case of HCMV, the multicomponent NEC involves emerin, p32/gC1qR, protein kinase C (PKC), cyclin-dependent kinases 1 and 2 (CDK1, CDK2), possibly further host CDKs/kinases, the viral kinase vCDK/pUL97, and the peptidylprolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 (Figure 2A [50,52,55,58,59,60,61]). The site-specific phosphorylation of lamins leads to a Pin1-dependent disruption of the nuclear lamina that allows de novo assembled capsids to reach the inner nuclear membrane (INM) [51]. The process, encompassing assembly, nucleocytoplasmic transition, and capsid maturation, is conserved in structure and function between α-, β-, and γ-herpesviruses [40,48,50,62,63,64]. As the herpesviral NEC recruits a number of different protein–protein interactions (PPIs), regulatory activities, and transport-specific functions, the options for drug-mediated targeting are broad and diversified. So far, the most interest has been paid to the analysis and development of small molecules interfering with NEC-specific PPI and kinase activities (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of herpesviral nuclear egress, highlighting the example of HCMV and current options of antiviral targeting. (A) The core NEC, consisting of a hook (pUL53 of HCMV) and groove (pUL50 of HCMV), recruits several other viral and cellular proteins, such as emerin, p32/gC1qR, host protein kinases (PKs), the viral PK (pUL97 of HCMV), Pin1, and possibly further effector proteins to phosphorylate and modify the nuclear lamina. The resulting reorganization of the nuclear lamina together with the hexameric arrangement of the core NEC heterodimers at the INM facilitates the egress of the viral capsid into the perinuclear space (modified from [48]). (B) Diverse targeting options of the NEC include the inhibition of initial core NEC heterodimerization, capsid docking, and interactions with further components of the multicomponent NEC (indicated via red-crossed interaction arrows). Kinase inhibitors such as MBV have already demonstrated strong antiviral activity by targeting the nuclear egress (indicated via blocked arrows).

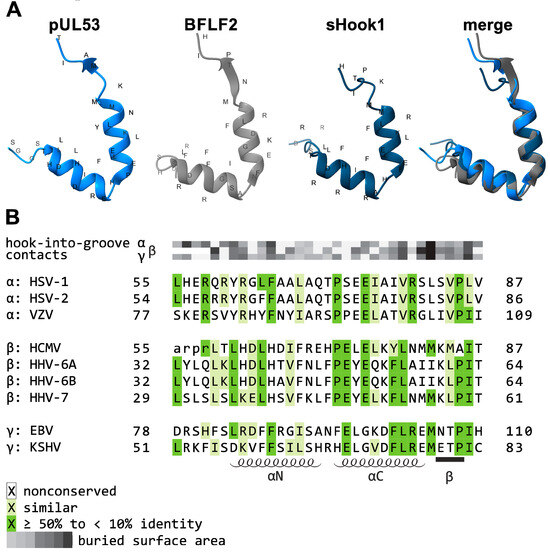

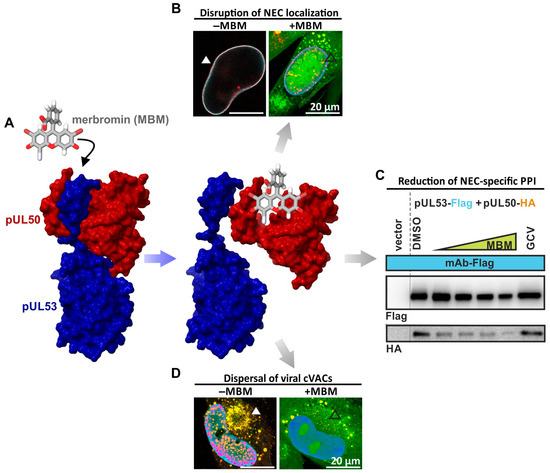

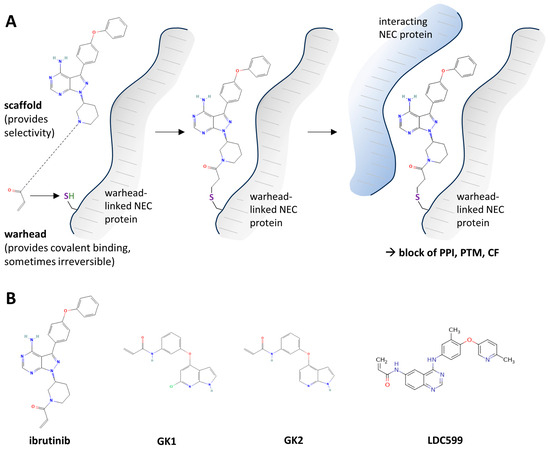

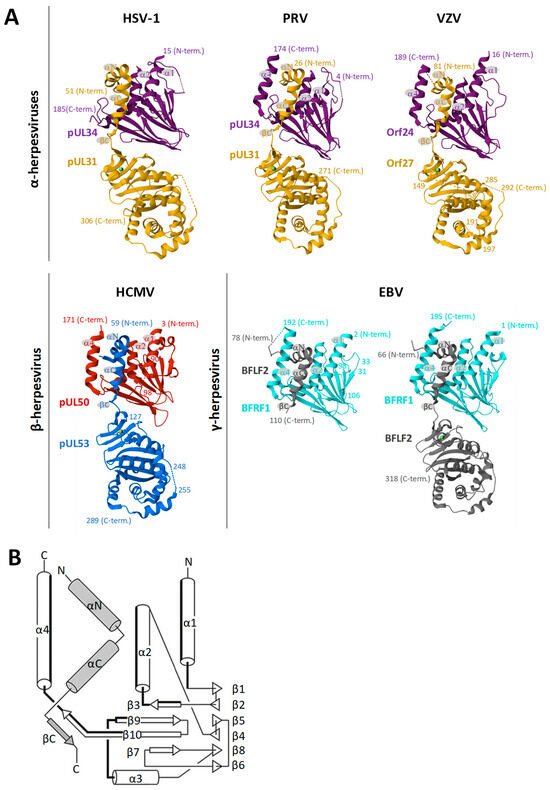

As central elements of the NEC, HCMV pUL50 and pUL53, or their homologs of the other herpesviruses, play a crucial role as a binding platform. Both proteins adopt a globular fold with mixed secondary structure elements (Figure 3). While pUL50 is located within the INM via a transmembrane domain (TMD), pUL53 comprises a classical nuclear localization signal (NLS) [65,66]. pUL53 carries a hallmark element by its N-terminal hook-like extension, consisting of two consecutive α-helices followed by a short β-strand (Figure 3A). This hook structure contributes around 80% of the interaction surface with the groove-like structure of pUL50, mainly composed of four α-helices, i.e., α1, α2, and α4 adjacent to a loop segment formed by α3, as linked to the beta-sheet β9 [48,65,67] (Figure 3B). Based on core NEC secondary structural elements, the nucleoplasmic pUL53 interacts in a hook-into-groove-like principle with its integral membrane protein counterpart pUL50, in a manner identical between all three herpesviral subfamilies [65,66,68]. Compared to the nearly fully conserved crystal structures of the core NECs (Figure 3) [48,69,70], the amount of sequence conservation, as measured by amino acid identity, is relatively limited [71].

Figure 3.

Summarized depiction of crystallization-based 3D structures of herpesviral core NECs resolved so far. (A) Groove proteins are depicted in violet, red, or cyan, with hook proteins in yellow, blue, or grey. Secondary structure elements involved in heterodimerization are indicated. Crystal structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)—HSV-1, 4ZXS [69]; PRV, 5E8C [72]; VZV, 7PAB [68]; HCMV, 5D5N [66]; EBV, 6T3Z [65]—and recently published including the globular domain of BFLF2 7T7I [73]. Additional valuable structural information on NECs has been provided by several more studies [69,70,72,74,75,76,77]. (B) Common topology plot visualizing the interacting secondary structure elements of the core NEC: hook segments indicated in grey, groove counterparts highlighted in bold [65].

So far, a number of mechanistic modes have been described that may be utilized for developing NEC-directed drugs [45]. These include the blocking of core NEC formation, the interference with activities of the multicomponent NEC (such as NEC-associated kinase, isomerase, or transport activities), the interference with capsid docking to the NEC, or the blocking of membrane-specific activities during primary envelopment [45]. As the first NEC-associated prototype inhibitor directed to viral kinase pUL97, MBV exerts a strong nuclear egress-inhibitory activity. Its inhibitory mode of action (MoA) concerns the pUL97-mediated phosphorylation of nuclear lamin and core NEC proteins as well additional multicomponent factors. This situation supports the strategy of a multifactorial option of inhibition, as based on a herpesviral nuclear egress-specific mechanism [22].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; methodology, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; validation, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; investigation, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; data curation, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; visualization, J.T., J.K., J.L. and M.M.; supervision, J.K. and M.M.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) grant 401821119/Research Training Group GRK2504; grant MA 1289/11-3; grant MA 1289/17-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all members of the M.M. research group for experimental and scientific support in the NEC project. We greatly appreciate the very valuable and continuous collaborative support from our NEC research partners at the FAU and in industry, in particular Heinrich Sticht (Division of Bioinformatics, FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany), Jutta Eichler (Department of Chemistry and Pharmacy, FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany), Yves A. Muller (Division of Biotechnology, FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany), and Peter Lischka (AiCuris Anti-Infective Cures AG, Wuppertal, Germany).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roizman, B.; Baines, J. The diversity and unity of Herpesviridae. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1991, 14, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, P.E.; Nimonkar, A.V. Herpes virus replication. IUBMB Life 2003, 55, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R.J. Herpesviruses. In Medical Microbiology; Baron, S., Ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, M.J.; Schmid, D.S.; Hyde, T.B. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010, 20, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Sternberg, M.R.; Kottiri, B.J.; McQuillan, G.M.; Lee, F.K.; Nahmias, A.J.; Berman, S.M.; Markowitz, L.E. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA 2006, 296, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J. Herpesvirus systematics. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 143, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Eberle, R.; Ehlers, B.; Hayward, G.S.; McGeoch, D.J.; Minson, A.C.; Pellett, P.E.; Roizman, B.; Studdert, M.J.; Thiry, E. The order Herpesvirales. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.C.; Liao, Y.T.; Juan, Y.T.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Su, M.T.; Su, Y.Z.; Liu, H.C.; Tsai, C.H.; Lee, C.P.; Chen, M.R. The novel nuclear targeting and BFRF1-interacting domains of BFLF2 are essential for efficient Epstein-Barr virus virion release. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01498-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.P.; Liu, G.T.; Kung, H.N.; Liu, P.T.; Liao, Y.T.; Chow, L.P.; Chang, L.S.; Chang, Y.H.; Chang, C.W.; Shu, W.C.; et al. The Ubiquitin Ligase Itch and Ubiquitination Regulate BFRF1-Mediated Nuclear Envelope Modification for Epstein-Barr Virus Maturation. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8994–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.T.; Kung, H.N.; Chen, C.K.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.L.; Yu, C.P.; Lee, C.P. Improving nuclear envelope dynamics by EBV BFRF1 facilitates intranuclear component clearance through autophagy. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2018, 32, 3968–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luitweiler, E.M.; Henson, B.W.; Pryce, E.N.; Patel, V.; Coombs, G.; McCaffery, J.M.; Desai, P.J. Interactions of the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus nuclear egress complex: ORF69 is a potent factor for remodeling cellular membranes. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 3915–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerboni, L.; Sen, N.; Oliver, S.L.; Arvin, A.M. Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershon, A.A.; Breuer, J.; Cohen, J.I.; Cohrs, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; Gilden, D.; Grose, C.; Hambleton, S.; Kennedy, P.G.; Oxman, M.N.; et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, Y.; Shiohara, T. Current understanding of cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent individuals. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2000, 22, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancini, D.; Faddy, H.M.; Flower, R.; Hogan, C. Cytomegalovirus disease in immunocompetent adults. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, J.G.; Carmichael, A.J. Clinical aspects and management of cytomegalovirus infection. J. Infect. 2002, 44, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, J.A. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2601–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianella, S.; Letendre, S. Cytomegalovirus and HIV: A Dangerous Pas de Deux. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214 (Suppl. S2), S67–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revello, M.G.; Gerna, G. Diagnosis and management of human cytomegalovirus infection in the mother, fetus, and newborn infant. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 680–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, Y. Effects of cytomegalovirus infection on embryogenesis and brain development. Congenit. Anom. 2009, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Reeves, M. Pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus in the immunocompromised host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingruber, M.; Marschall, M. The cytomegalovirus protein kinase pUL97:host interactions, regulatory mechanisms and antiviral drug targeting. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanimura, K.; Uchida, A.; Imafuku, H.; Tairaku, S.; Fujioka, K.; Morioka, I.; Yamada, H. The Current Challenges in Developing Biological and Clinical Predictors of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, H.C.; Pei, Y.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr Virus: Diseases Linked to Infection and Transformation. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, L.S.; Rickinson, A.B. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, L.S.; Yap, L.F.; Murray, P.G. Epstein-Barr virus: More than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.; Noble, S. Valganciclovir. Drugs 2001, 61, 1145–1150; discussion 1151–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, V.; Talarico, C.L.; Stanat, S.C.; Davis, M.; Coen, D.M.; Biron, K.K. A protein kinase homologue controls phosphorylation of ganciclovir in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Nature 1992, 358, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Holý, A. Acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: A key class of antiviral drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakki, M. Moving Past Ganciclovir and Foscarnet: Advances in CMV Therapy. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2020, 15, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, K.K. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antivir. Res. 2006, 71, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, G.; Michel, D. Antiviral treatment of cytomegalovirus infection: An update. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischka, P.; Zimmermann, H. Antiviral strategies to combat cytomegalovirus infections in transplant recipients. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, B.G.; Bogner, E.; Drach, J.C. Targeting the terminase: An important step forward in the treatment and prophylaxis of human cytomegalovirus infections. Antivir. Res. 2019, 161, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakharia, N.; Howard, D.; Riedel, D.J. CMV Infection in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischka, P.; Hewlett, G.; Wunberg, T.; Baumeister, J.; Paulsen, D.; Goldner, T.; Ruebsamen-Schaeff, H.; Zimmermann, H. In vitro and in vivo activities of the novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Song, K.; Wu, J.; Bo, T.; Crumpacker, C. Drug Resistance Mutations and Associated Phenotypes Detected in Clinical Trials of Maribavir for Treatment of Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eid, A.J.; Arthurs, S.K.; Deziel, P.J.; Wilhelm, M.P.; Razonable, R.R. Emergence of drug-resistant cytomegalovirus in the era of valganciclovir prophylaxis: Therapeutic implications and outcomes. Clin. Transplant. 2008, 22, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razonable, R.R. Drug-resistant cytomegalovirus: Clinical implications of specific mutations. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2018, 23, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, R.J.; Baines, J.D. Herpesvirus Nuclear Egress. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2017, 223, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R.K.; Alain, S.; Alexander, B.D.; Blumberg, E.A.; Chemaly, R.F.; Cordonnier, C.; Duarte, R.F.; Florescu, D.F.; Kamar, N.; Kumar, D.; et al. Maribavir for Refractory Cytomegalovirus Infections With or Without Resistance Post-Transplant: Results From a Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Kicuntod, J.; Seyler, L.; Wangen, C.; Bertzbach, L.D.; Conradie, A.M.; Kaufer, B.B.; Wagner, S.; Michel, D.; Eickhoff, J.; et al. Combinatorial Drug Treatments Reveal Promising Anticytomegaloviral Profiles for Clinically Relevant Pharmaceutical Kinase Inhibitors (PKIs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.T.; Marschall, M.; Rawlinson, W.D. Investigational Antiviral Therapy Models for the Prevention and Treatment of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection during Pregnancy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourin, C.; Alain, S.; Hantz, S. Anti-CMV therapy, what next? A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1321116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häge, S.; Marschall, M. ‘Come together’-The Regulatory Interaction of Herpesviral Nuclear Egress Proteins Comprises Both Essential and Accessory Functions. Cells 2022, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganova, E.B.; Thorsen, M.K.; Heldwein, E.E. Nuclear Egress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 41, 125–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, L.T.; Pellet, P.E. The Family Herpesviridae: A Brief Introduction. In Fields Virology, 7th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Wolter Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 212–234. [Google Scholar]

- Marschall, M.; Häge, S.; Conrad, M.; Alkhashrom, S.; Kicuntod, J.; Schweininger, J.; Kriegel, M.; Lösing, J.; Tillmanns, J.; Neipel, F.; et al. Nuclear egress complexes of HCMV and other herpesviruses: Solving the puzzle of sequence coevolution, conserved structures and subfamily-spanning binding properties. Viruses 2020, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panté, N.; Kann, M. Nuclear pore complex is able to transport macromolecules with diameters of about 39 nm. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Muller, Y.A.; Diewald, B.; Sticht, H.; Milbradt, J. The human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex unites multiple functions: Recruitment of effectors, nuclear envelope rearrangement, and docking to nuclear capsids. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017, 27, e1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Hutterer, C.; Bahsi, H.; Wagner, S.; Sonntag, E.; Horn, A.H.; Kaufer, B.B.; Mori, Y.; Sticht, H.; Fossen, T.; et al. The Prolyl Isomerase Pin1 Promotes the Herpesvirus-Induced Phosphorylation-Dependent Disassembly of the Nuclear Lamina Required for Nucleocytoplasmic Egress. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Webel, R.; Auerochs, S.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Novel mode of phosphorylation-triggered reorganization of the nuclear lamina during nuclear egress of human cytomegalovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13979–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, V.; Britt, W. Human Cytomegalovirus Egress: Overcoming Barriers and Co-Opting Cellular Functions. Viruses 2021, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häge, S.; Sonntag, E.; Svrlanska, A.; Borst, E.M.; Stilp, A.C.; Horsch, D.; Müller, R.; Kropff, B.; Milbradt, J.; Stamminger, T.; et al. Phenotypical Characterization of the Nuclear Egress of Recombinant Cytomegaloviruses Reveals Defective Replication upon ORF-UL50 Deletion but Not pUL50 Phosphosite Mutation. Viruses 2021, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbradt, J.; Sonntag, E.; Wagner, S.; Strojan, H.; Wangen, C.; Lenac Rovis, T.; Lisnic, B.; Jonjic, S.; Sticht, H.; Britt, W.J.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus nuclear capsids associate with the core nuclear egress complex and the viral protein kinase pUL97. Viruses 2018, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuny, C.V.; Chinchilla, K.; Culbertson, M.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Cyclin-dependent kinase-like function is shared by the beta- and gamma- subset of the conserved herpesvirus protein kinases. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Kamil, J.P.; Coughlin, M.; Reim, N.I.; Coen, D.M. Human cytomegalovirus UL50 and UL53 recruit viral protein kinase UL97, not protein kinase C, for disruption of nuclear lamina and nuclear egress in infected cells. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Marzi, A.; aus dem Siepen, P.; Jochmann, R.; Kalmer, M.; Auerochs, S.; Lischka, P.; Leis, M.; Stamminger, T. Cellular p32 recruits cytomegalovirus kinase pUL97 to redistribute the nuclear lamina. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33357–33367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Auerochs, S.; Marschall, M. Cytomegaloviral proteins pUL50 and pUL53 are associated with the nuclear lamina and interact with cellular protein kinase C. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 2642–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Auerochs, S.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Cytomegaloviral proteins that associate with the nuclear lamina: Components of a postulated nuclear egress complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Kraut, A.; Hutterer, C.; Sonntag, E.; Schmeiser, C.; Ferro, M.; Wagner, S.; Lenac, T.; Claus, C.; Pinkert, S.; et al. Proteomic analysis of the multimeric nuclear egress complex of human cytomegalovirus. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014, 13, 2132–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigalke, J.M.; Heldwein, E.E. Have NEC Coat, Will Travel: Structural Basis of Membrane Budding During Nuclear Egress in Herpesviruses. Adv. Virus. Res. 2017, 97, 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Shen, S.; Xiang, L.; Jia, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, D.; Deng, H. Functional Identification and Characterization of the Nuclear Egress Complex of a Gammaherpesvirus. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01422-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, M.F.; Wilkie, A.R.; Filman, D.J.; Hogle, J.M.; Coen, D.M. Getting to and through the inner nuclear membrane during herpesvirus nuclear egress. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 46, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, Y.A.; Hage, S.; Alkhashrom, S.; Hollriegl, T.; Weigert, S.; Dolles, S.; Hof, K.; Walzer, S.A.; Egerer-Sieber, C.; Conrad, M.; et al. High-resolution crystal structures of two prototypical beta- and gamma-herpesviral nuclear egress complexes unravel the determinants of subfamily specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 3189–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, S.A.; Egerer-Sieber, C.; Sticht, H.; Sevvana, M.; Hohl, K.; Milbradt, J.; Muller, Y.A.; Marschall, M. Crystal structure of the human cytomegalovirus pUL50-pUL53 core nuclear egress complex provides insight into a unique assembly scaffold for virus-host protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 27452–27458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösing, J.; Häge, S.; Schütz, M.; Wagner, S.; Wardin, J.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. ‘Shared-Hook’ and ‘Changed-Hook’ Binding Activities of Herpesviral Core Nuclear Egress Complexes Identified by Random Mutagenesis. Cells 2022, 11, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweininger, J.; Kriegel, M.; Häge, S.; Conrad, M.; Alkhashrom, S.; Lösing, J.; Weiler, S.; Tillmanns, J.; Egerer-Sieber, C.; Decker, A.; et al. The crystal structure of the varicella-zoster Orf24-Orf27 nuclear egress complex spotlights multiple determinants of herpesvirus subfamily specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigalke, J.M.; Heldwein, E.E. Structural basis of membrane budding by the nuclear egress complex of herpesviruses. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2921–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, M.F.; Sharma, M.; El Omari, K.; Filman, D.J.; Schuermann, J.P.; Hogle, J.M.; Coen, D.M. Unexpected features and mechanism of heterodimer formation of a herpesvirus nuclear egress complex. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2937–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häge, S.; Sonntag, E.; Borst, E.M.; Tannig, P.; Seyler, L.; Bauerle, T.; Bailer, S.M.; Lee, C.P.; Muller, R.; Wangen, C.; et al. Patterns of autologous and nonautologous interactions between core nuclear egress complex (NEC) proteins of alpha-, beta- and gamma-herpesviruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, T.; Weberruß, M.; Lorenz, M.; Cheleski, J.; Hellberg, T.; Whittle, C.; El Omari, K.; Vasishtan, D.; Dent, K.C.; Harlos, K.; et al. Crystal Structure of the Herpesvirus Nuclear Egress Complex Provides Insights into Inner Nuclear Membrane Remodeling. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 2645–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsen, M.K.; Draganova, E.B.; Heldwein, E.E. The nuclear egress complex of Epstein-Barr virus buds membranes through an oligomerization-driven mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigalke, J.M.; Heuser, T.; Nicastro, D.; Heldwein, E.E. Membrane deformation and scission by the HSV-1 nuclear egress complex. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, C.; Dent, K.C.; Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, T.; Grange, M.; Bosse, J.B.; Whittle, C.; Klupp, B.G.; Siebert, C.A.; Vasishtan, D.; Bauerlein, F.J.; et al. Structural basis of vesicle formation at the inner nuclear membrane. Cell 2015, 163, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, K.E.; Sharma, M.; Mansueto, M.S.; Boeszoermenyi, A.; Filman, D.J.; Hogle, J.M.; Wagner, G.; Coen, D.M.; Arthanari, H. Structure of a herpesvirus nuclear egress complex subunit reveals an interaction groove that is essential for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9010–9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Auerochs, S.; Sevvana, M.; Muller, Y.A.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Specific residues of a conserved domain in the N terminus of the human cytomegalovirus pUL50 protein determine its intranuclear interaction with pUL53. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 24004–24016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.E.; Sant, C.V.; Krug, P.W.; Sears, A.E.; Roizman, B. The null mutant of the U(L)31 gene of herpes simplex virus 1: Construction and phenotype in infected cells. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8307–8315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, W.; Klupp, B.G.; Granzow, H.; Osterrieder, N.; Mettenleiter, T.C. The interacting UL31 and UL34 gene products of pseudorabies virus are involved in egress from the host-cell nucleus and represent components of primary enveloped but not mature virions. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Tanaka, M.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Baines, J.D. Cell lines that support replication of a novel herpes simplex virus 1 UL31 deletion mutant can properly target UL34 protein to the nuclear rim in the absence of UL31. Virology 2004, 329, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupp, B.G.; Nixdorf, R.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Pseudorabies virus glycoprotein M inhibits membrane fusion. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6760–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, R.J.; Zhou, Y.; Schnetzer, R.; Ferguson, J.; DeSalvo, D. Herpes simplex virus type 1 U(L)34 gene product is required for viral envelopment. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.J.; Roizman, B. The essential protein encoded by the UL31 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 depends for its stability on the presence of UL34 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11002–11007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, K.S.; Klupp, B.G.; Granzow, H.; Müller, F.M.; Fuchs, W.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Analysis of viral and cellular factors influencing herpesvirus-induced nuclear envelope breakdown. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6512–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupp, B.G.; Granzow, H.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Nuclear envelope breakdown can substitute for primary envelopment-mediated nuclear egress of herpesviruses. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 8285–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Etingov, I.; Pante, N. Effect of viral infection on the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 299, 117–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, Y.; Hodgson, L.; Mantell, J.; Verkade, P.; Carlton, J.G. ESCRT-III controls nuclear envelope reformation. Nature 2015, 522, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmanns, J.; Häge, S.; Borst, E.M.; Wardin, J.; Eickhoff, J.; Klebl, B.; Wagner, S.; Wangen, C.; Hahn, F.; Socher, E.; et al. Assessment of Covalently Binding Warhead Compounds in the Validation of the Cytomegalovirus Nuclear Egress Complex as an Antiviral Target. Cells 2023, 12, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häge, S.; Horsch, D.; Stilp, A.C.; Kicuntod, J.; Müller, R.; Hamilton, S.T.; Egilmezer, E.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Stamminger, T.; Sonntag, E.; et al. A quantitative nuclear egress assay to investigate the nucleocytoplasmic capsid release of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. Methods 2020, 283, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossum, E.; Friedel, C.C.; Rajagopala, S.V.; Titz, B.; Baiker, A.; Schmidt, T.; Kraus, T.; Stellberger, T.; Rutenberg, C.; Suthram, S.; et al. Evolutionarily conserved herpesviral protein interaction networks. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.; Farina, A.; Granato, M.; Gonnella, R.; Raffa, S.; Leone, L.; Bei, R.; Modesti, A.; Frati, L.; Torrisi, M.R.; et al. Identification and characterization of the product encoded by ORF69 of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4562–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnee, M.; Ruzsics, Z.; Bubeck, A.; Koszinowski, U.H. Common and specific properties of herpesvirus UL34/UL31 protein family members revealed by protein complementation assay. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11658–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhashrom, S.; Kicuntod, J.; Häge, S.; Schweininger, J.; Muller, Y.A.; Lischka, P.; Marschall, M.; Eichler, J. Exploring the Human Cytomegalovirus Core Nuclear Egress Complex as a Novel Antiviral Target: A New Type of Small Molecule Inhibitors. Viruses 2021, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhashrom, S.; Kicuntod, J.; Stillger, K.; Lützenburg, T.; Anzenhofer, C.; Neundorf, I.; Marschall, M.; Eichler, J. A Peptide Inhibitor of the Human Cytomegalovirus Core Nuclear Egress Complex. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Lye, M.F.; Gorgulla, C.; Ficarro, S.B.; Cuny, G.D.; Scott, D.A.; Wu, F.; Rothlauf, P.W.; Wang, X.; Fernandez, R.; et al. A small molecule exerts selective antiviral activity by targeting the human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganova, E.B.; Heldwein, E.E. Virus-derived peptide inhibitors of the herpes simplex virus type 1 nuclear egress complex. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicuntod, J.; Alkhashrom, S.; Häge, S.; Diewald, B.; Müller, R.; Hahn, F.; Lischka, P.; Sticht, H.; Eichler, J.; Marschall, M. Properties of Oligomeric Interaction of the Cytomegalovirus Core Nuclear Egress Complex (NEC) and Its Sensitivity to an NEC Inhibitory Small Molecule. Viruses 2021, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

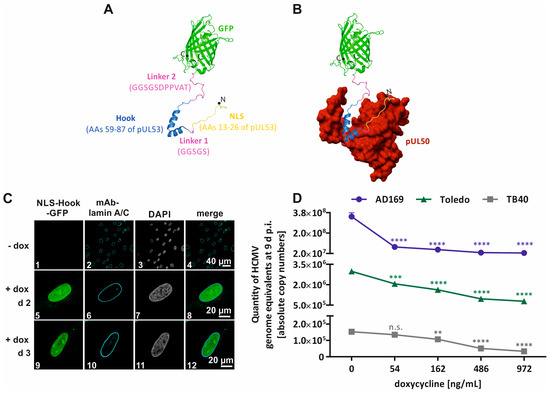

- Kicuntod, J.; Häge, S.; Lösing, J.; Kopar, S.; Muller, Y.A.; Marschall, M. An antiviral targeting strategy based on the inducible interference with cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex. Antivir. Res. 2023, 212, 105557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicuntod, J.; Häge, S.; Hahn, F.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. The Oligomeric Assemblies of Cytomegalovirus Core Nuclear Egress Proteins Are Associated with Host Kinases and Show Sensitivity to Antiviral Kinase Inhibitors. Viruses 2022, 14, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Burley, S.K.; Kleywegt, G.J.; Markley, J.L.; Nakamura, H.; Velankar, S. The archiving and dissemination of biological structure data. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 40, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormö, M.; Cubitt, A.B.; Kallio, K.; Gross, L.A.; Tsien, R.Y.; Remington, S.J. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science 1996, 273, 1392–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, E.; Bowlin, T.; Brooks, J.; Chiang, L.; Hussein, I.; Kimberlin, D.; Kauvar, L.M.; Leavitt, R.; Prichard, M.; Whitley, R. Advances in the Development of Therapeutics for Cytomegalovirus Infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, S32–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotton, C.N. Updates on antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus prevention and treatment. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2019, 24, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.K.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wei, F.; Shen, M.X.; Zhong, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, L.J.; Ma, N.; Liu, B.Y.; Mao, Y.D.; et al. Antiviral activity of arbidol hydrochloride against herpes simplex virus I in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Coen, D.M. Comparison of effects of inhibitors of viral and cellular protein kinases on human cytomegalovirus disruption of nuclear lamina and nuclear egress. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 10982–10985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péczka, N.; Orgován, Z.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Keserű, G.M. Electrophilic warheads in covalent drug discovery: An overview. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Petri, L.; Imre, T.; Szijj, P.; Scarpino, A.; Hrast, M.; Mitrović, A.; Fonovič, U.P.; Németh, K.; Barreteau, H.; et al. A road map for prioritizing warheads for cysteine targeting covalent inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 160, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangarpour, M.; Kavianinia, I.; Brimble, M.A. Thia-Michael addition: The route to promising opportunities for fast and cysteine-specific modification. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 3057–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, M.; Laufer, S.A. Emerging and Re-Emerging Warheads for Targeted Covalent Inhibitors: Applications in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5673–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Orally effective FDA-approved protein kinase targeted covalent inhibitors (TCIs). Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 165, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillie, T.A. Targeted Covalent Inhibitors for Drug Design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 13408–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonsdale, R.; Burgess, J.; Colclough, N.; Davies, N.L.; Lenz, E.M.; Orton, A.L.; Ward, R.A. Expanding the Armory: Predicting and Tuning Covalent Warhead Reactivity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 3124–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, M.D.; Evans, B.T.; Coen, D.M.; Hogle, J.M. Biochemical, biophysical, and mutational analyses of subunit interactions of the human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2996–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hatcher, J.M.; Teng, M.; Gray, N.S.; Kostic, M. Recent Advances in Selective and Irreversible Covalent Ligand Development and Validation. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 1486–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feni, L.; Neundorf, I. The Current Role of Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Cancer Therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1030, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habault, J.; Poyet, J.L. Recent Advances in Cell Penetrating Peptide-Based Anticancer Therapies. Molecules 2019, 24, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, F.; Lindberg, S.; Langel, U.; Futaki, S.; Gräslund, A. Mechanisms of cellular uptake of cell-penetrating peptides. J. Biophys. 2011, 2011, 414729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, A.S.; Vupputuri, S.; Flynn, N.; Ramsey, J.D. Effects of cell-penetrating peptides on transduction efficiency of PEGylated adenovirus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 71, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, S. Cell penetration: Scope and limitations by the application of cell-penetrating peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 760–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Duarte, D.; Silva, S.; Correia, A.S.; Costa, B.; Gouveia, M.J.; Ferreira, A. Cell-penetrating peptides in oncologic pharmacotherapy: A review. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 162, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Cao, X.W.; Fu, L.Y.; Zhang, T.Z.; Wang, F.J.; Zhao, J. Screening and characterization of a novel high-efficiency tumor-homing cell-penetrating peptide from the buffalo cathelicidin family. J. Pept. Sci. 2019, 25, e3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeiser, C.; Borst, E.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M.; Milbradt, J. The cytomegalovirus egress proteins pUL50 and pUL53 are translocated to the nuclear envelope through two distinct modes of nuclear import. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2056–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muranyi, W.; Haas, J.; Wagner, M.; Krohne, G.; Koszinowski, U.H. Cytomegalovirus recruitment of cellular kinases to dissolve the nuclear lamina. Science 2002, 297, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonntag, E.; Hamilton, S.T.; Bahsi, H.; Wagner, S.; Jonjic, S.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Marschall, M.; Milbradt, J. Cytomegalovirus pUL50 is the multi-interacting determinant of the core nuclear egress complex (NEC) that recruits cellular accessory NEC components. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonntag, E.; Milbradt, J.; Svrlanska, A.; Strojan, H.; Hage, S.; Kraut, A.; Hesse, A.M.; Amin, B.; Sonnewald, U.; Coute, Y.; et al. Protein kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of the nuclear egress core complex of human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arii, J. Host and Viral Factors Involved in Nuclear Egress of Herpes Simplex Virus 1. Viruses 2021, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailer, S.M. Venture from the Interior-Herpesvirus pUL31 Escorts Capsids from Nucleoplasmic Replication Compartments to Sites of Primary Envelopment at the Inner Nuclear Membrane. Cells 2017, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigalke, J.M.; Heldwein, E.E. Nuclear Exodus: Herpesviruses Lead the Way. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016, 3, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, J.B.; Enquist, L.W. The diffusive way out: Herpesviruses remodel the host nucleus, enabling capsids to access the inner nuclear membrane. Nucleus 2016, 7, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellberg, T.; Passvogel, L.; Schulz, K.S.; Klupp, B.G.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Nuclear Egress of Herpesviruses: The Prototypic Vesicular Nucleocytoplasmic Transport. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 94, 81–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.P.; Chen, M.R. Conquering the Nuclear Envelope Barriers by EBV Lytic Replication. Viruses 2021, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roller, R.J.; Johnson, D.C. Herpesvirus Nuclear Egress across the Outer Nuclear Membrane. Viruses 2021, 13, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Cordsmeier, A.; Wangen, C.; Horn, A.H.C.; Wyler, E.; Ensser, A.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. The Interactive Complex between Cytomegalovirus Kinase vCDK/pUL97 and Host Factors CDK7-Cyclin H Determines Individual Patterns of Transcription in Infected Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Wangen, C.; Sommerer, M.; Kögler, M.; Eickhoff, J.; Degenhart, C.; Klebl, B.; Naing, Z.; Egilmezer, E.; Hamilton, S.T.; et al. Cytomegalovirus cyclin-dependent kinase ortholog vCDK/pUL97 undergoes regulatory interaction with human cyclin H and CDK7 to codetermine viral replication efficiency. Virus Res. 2023, 335, 199200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Bender, B.J.; Kamil, J.P.; Lye, M.F.; Pesola, J.M.; Reim, N.I.; Hogle, J.M.; Coen, D.M. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 phosphorylates the viral nuclear egress complex. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahnamiri, M.M.; Roller, R.J. Distinct roles of viral US3 and UL13 protein kinases in herpes virus simplex type 1 (HSV-1) nuclear egress. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Monreal, G.L.; Wylie, K.M.; Cao, F.; Tavis, J.E.; Morrison, L.A. Herpes simplex virus 2 UL13 protein kinase disrupts nuclear lamins. Virology 2009, 392, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.P.; Huang, Y.H.; Lin, S.F.; Chang, Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Takada, K.; Chen, M.R. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase induces disassembly of the nuclear lamina to facilitate virion production. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11913–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krosky, P.M.; Baek, M.C.; Coen, D.M. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein kinase, an antiviral drug target, is required at the stage of nuclear egress. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, M.N.; Gao, N.; Jairath, S.; Mulamba, G.; Krosky, P.; Coen, D.M.; Parker, B.O.; Pari, G.S. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 5663–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.G.; Courcelle, C.T.; Prichard, M.N.; Mocarski, E.S. Distinct and separate roles for herpesvirus-conserved UL97 kinase in cytomegalovirus DNA synthesis and encapsidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C. Maribavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herget, T.; Freitag, M.; Morbitzer, M.; Kupfer, R.; Stamminger, T.; Marschall, M. Novel chemical class of pUL97 protein kinase-specific inhibitors with strong anticytomegaloviral activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4154–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutterer, C.; Hamilton, S.; Steingruber, M.; Zeitträger, I.; Bahsi, H.; Thuma, N.; Naing, Z.; Örfi, Z.; Örfi, L.; Socher, E.; et al. The chemical class of quinazoline compounds provides a core structure for the design of anticytomegaloviral kinase inhibitors. Antivir. Res. 2016, 134, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Freitag, M.; Suchy, P.; Romaker, D.; Kupfer, R.; Hanke, M.; Stamminger, T. The protein kinase pUL97 of human cytomegalovirus interacts with and phosphorylates the DNA polymerase processivity factor pUL44. Virology 2003, 311, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleiss, M.R. Cytomegalovirus vaccine development. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 325, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Hahn, F.; Brückner, N.; Schütz, M.; Wangen, C.; Wagner, S.; Sommerer, M.; Strobl, S.; Marschall, M. Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs) and the Human Cytomegalovirus-Encoded CDK Ortholog pUL97 Represent Highly Attractive Targets for Synergistic Drug Combinations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kamil, J.P.; Coen, D.M. Preparation of the Human Cytomegalovirus Nuclear Egress Complex and Associated Proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 569, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemnitzer, F.; Raschbichler, V.; Kolodziejczak, D.; Israel, L.; Imhof, A.; Bailer, S.M.; Koszinowski, U.; Ruzsics, Z. Mouse cytomegalovirus egress protein pM50 interacts with cellular endophilin-A2. Cell. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kato, A.; Oyama, M.; Kozuka-Hata, H.; Arii, J.; Kawaguchi, Y. Role of Host Cell p32 in Herpes Simplex Virus 1 De-Envelopment during Viral Nuclear Egress. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8982–8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Libotte, F.; Buono, E.; Valia, S.; Farina, G.A.; Faggioni, A.; Farina, A. EBV early lytic protein BFRF1 alters emerin distribution and post-translational modification. Virus Res. 2017, 232, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamirally, S.; Kamil, J.P.; Ndassa-Colday, Y.M.; Lin, A.J.; Jahng, W.J.; Baek, M.C.; Noton, S.; Silva, L.A.; Simpson-Holley, M.; Knipe, D.M.; et al. Viral mimicry of Cdc2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 mediates disruption of nuclear lamina during human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, R.; McKeon, F. Mutations of phosphorylation sites in lamin A that prevent nuclear lamina disassembly in mitosis. Cell 1990, 61, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L.A.; DeLassus, G.S. Breach of the nuclear lamina during assembly of herpes simplex viruses. Nucleus 2011, 2, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.L.; Mathias, R.A. The human cytomegalovirus decathlon: Ten critical replication events provide opportunities for restriction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1053139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Thomas, M.; Wangen, C.; Wagner, S.; Rauschert, L.; Errerd, T.; Kießling, M.; Sticht, H.; Milbradt, J.; Marschall, M. The peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 interacts with three early regulatory proteins of human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganova, E.B.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.H.; Heldwein, E.E. Structural basis for capsid recruitment and coat formation during HSV-1 nuclear egress. eLife 2020, 9, e56627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, C.; Ott, M.; Raschbichler, V.; Nagel, C.H.; Binz, A.; Sodeik, B.; Bauerfeind, R.; Bailer, S.M. The herpes simplex virus protein pUL31 escorts nucleocapsids to sites of nuclear egress, a process coordinated by its N-terminal domain. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, K.; Arii, J.; Maruzuru, Y.; Koyanagi, N.; Kato, A.; Kawaguchi, Y. Identification of the Capsid Binding Site in the Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Nuclear Egress Complex and Its Role in Viral Primary Envelopment and Replication. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01290-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvory-Sobol, H.; Shaik, N.; Callebaut, C.; Rhee, M.S. Lenacapavir: A first-in-class HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2022, 17, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).