Abstract

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the most common types of cardiovascular disease and can lead to a heart attack as plaque gradually builds up inside the coronary arteries, blocking blood flow. Previous studies have shown that polymorphisms in the PAI-1 gene are associated with CAD; however, studies of the PAI-1 3′-untranslated region, containing a miRNA binding site, and the miRNAs that interact with it, are insufficient. To investigate the association between miRNA polymorphisms and CAD in the Korean population based on post-transcriptional regulation, we genotyped five polymorphisms in four miRNAs targeting the 3′-untranslated region of PAI-1 using real-time PCR and TaqMan assays. We found that the mutant genotype of miR-30c rs928508 A > G was strongly associated with increased CAD susceptibility. In a genotype combination analysis, the combination of the homozygous mutant genotype (GG) of miR-30c rs928508 with the wild-type genotype (GG) of miR-143 rs41291957 resulted in increased risk for CAD. Also, in an allele combination analysis, the combination of the mutant allele (G) of miR-30c rs928508 and the wild-type allele (G) of miR-143 rs41291957 resulted in increased risk for CAD. Furthermore, metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus showed synergistic effects on CAD risk when combined with miR-30c rs928508. These results can be applied to identify CAD prognostic biomarkers among miRNA polymorphisms and various clinical factors.

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a form of cardiovascular disease caused by plaque accumulation on the walls of coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart. In atherosclerotic disease, these plaques eventually block blood flow to the heart. Because of this, CAD can lead to heart failure, a condition in which the heart’s ability to pump blood is reduced [1]. Risk factors related to CAD include hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes [2,3,4,5]. Several studies have reported that polymorphisms in genes related to fibrin degradation and fibrin coagulation are also associated with CAD [6,7]. In particular, some variants in the promoter region of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (also known as SERPINE1 or PAI-1), which regulates fibrinolysis, are thought to be associated with CAD sensitivity [8,9].

Micro (mi)RNAs are a class of small (18–22 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs that play important regulatory roles in gene expression. By binding to 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) in target mRNAs, miRNAs regulate post-transcriptional gene expression by causing translational repression or mRNA degradation [10,11]. Through these mechanisms, miRNAs are involved in the regulation of cell growth, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell differentiation [12]. In addition, miRNAs play essential roles in the cardiovascular system by regulating heart and blood vessel development as well as cardiovascular diseases [13]. Recently, several miRNAs were found to regulate CAD development [14,15].

The PAI-1 gene, which encodes a member of the serine protease inhibitor superfamily, is located on chromosome 7. PAI-1 is produced by endothelial cells, platelets, and other cell types and is associated with several disease conditions including diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome (MetS), and obesity. When plasminogen is converted to plasmin, the fibrinolytic system is initiated [16]. When plasmin is activated by tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA), it causes fibrinolysis, matrix metalloprotease activation, and extracellular matrix degradation [17]. This fibrinolytic system is regulated by PAI-1. Studies have shown that polymorphisms in PAI-1 are associated with CAD [18].

The above data suggests a role for both PAI-1 and miRNAs in CAD. Based on these associations, we wondered how expression-altering miRNAs that bind to the 3′-UTR of PAI-1 impact the risk for CAD and if there are any associations between polymorphisms in these miRNA genes and other CAD risk factors. To answer these questions, we designed a genetic epidemiological study to test for associations between CAD risk in the Korean population and five polymorphisms of miRNAs binding to the 3′-UTR of the PAI-1 gene: miR-30c rs928508 A > G, miR-143 rs41291957 G > A, miR-143 rs4705342 T > C, miR-145 rs353291 T > C, and miR-181a2 rs10760371 T > G.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

Table 1 displays the clinical characteristics of the 483 patients with CAD and the 400 control participants. The comparison between patients and controls did not reveal any significant differences in age or sex (p = 0.511 and p = 0.124, respectively). The average body mass index (BMI) of the patients (mean ± standard deviation [SD] = 24.92 ± 3.48) was significantly higher than that of the controls (24.33 ± 3.39). Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and MetS, which are major risk factors for CAD, were more prevalent among the patients than among the controls (p < 0.05 for each). There were no statistically significant differences in hyperlipidemia or smoking status between the two groups. Fasting blood sugar, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol), Total cholesterol, and folate and creatinine levels were significantly different between the patients and controls (p < 0.05 for each). There were no differences in the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol) (p = 0.072), triglycerides (p = 0.074), homocysteine (p = 0.861), or vitamin B12 (p = 0.314) between the patients and the controls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between CAD and controls.

2.2. Genotype Frequencies of miRNA SNPs

To assess potential correlations between CAD risk and the five polymorphisms in miRNAs known to target the PAI-1 3′-UTR, we measured the genotype frequencies of each polymorphism in the patient and the control cohorts (Table 2). We found that the genotype frequencies of the specified SNPs in both cohorts conformed to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE; p > 0.05), suggesting that the population distribution was consistent with the principles of HWE. For miR-30c rs928508, in an adjusted statistical analysis considering age, sex, hypertension, and diabetes, there was a significant difference in the GG genotype [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.636, p = 0.026] and the recessive model (AOR = 1.527, p = 0.037) between the patients and the controls.

Table 2.

Genotype frequencies of PAI-1-related miRNA polymorphisms in CAD and controls.

2.3. Genotype Combination Analysis

We performed a genotype combination analysis to look for the effects of combined miRNA genotypes on CAD risk (Table 3). We found that CAD risk was increased when the homozygous mutant genotype of miR-30c rs928508 was combined with the homozygous wild-type genotypes of miR-143 rs41291957 (GG/GG, AOR = 2.052), miR-143 rs4705342 (GG/TT, AOR = 1.932), or miR-181a2 rs10760371 (GG/TT, AOR = 2.890). Conversely, the CAD risk was reduced with certain combinations of genotypes of miR-143 rs41291957 and miR-143 rs4705342 (GG/TC, AOR = 0.517; GA/TT, AOR = 0.253; AA/TC, AOR = 0.360). None of the other genotype combinations were associated with CAD risk (Table S1).

Table 3.

Genotype combination frequencies of PAI-1-related miRNA polymorphisms in CAD patients and controls.

2.4. Allele Combination Analysis

We performed an allele combination analysis to identify combinations of alleles at the five miRNA polymorphisms that were associated with CAD risk (Table 4). The combination of the mutant allele (G) of miR-30c rs928508 and the wild-type allele (T) of miR-143 rs4705342 was associated with increased CAD risk (AOR = 1.307, 95% CI = 1.034–1.651, p = 0.025). These two alleles also increased the CAD risk in three-allele and four-allele combinations with the wild-type alleles of miR-143 rs41291957 (G), miR-145 rs353291 (T), and miR-181a2 rs10760371 (T).

Table 4.

Summary of results from allele combination analysis in CAD patients and controls identifying PAI-1–related miRNA polymorphisms associated with increased CAD risk.

On the other hand, the combination of the wild-type allele (G) of miR-143 rs41291957 and the mutant allele (C) of miR-143 rs4705342 was associated with decreased CAD risk (AOR = 0.519, 95% CI = 0.337–0.800, p = 0.003). These two alleles also reduced the CAD risk in three-allele and four-allele combinations with the mutant allele of miR-145 rs353291 (C) and the wild-type allele of miR-181a2 rs10760371 (T) (Table 5). The mutant allele (A) of miR-143 rs41291957 and the wild-type allele (T) of miR-143 rs4705342 were also associated with decreased CAD risk in a two-allele combination (AOR = 0.249, 95% CI = 0.121–0.513, p < 0.0001) and in three-allele and four-allele combinations with the wild-type alleles of miR-145 rs353291 (T) and miR-181a2 rs10760371 (T).

Table 5.

Summary of results from allele combinations analysis in CAD patients and controls identifying PAI-1–related miRNA polymorphisms associated with decreased CAD risk.

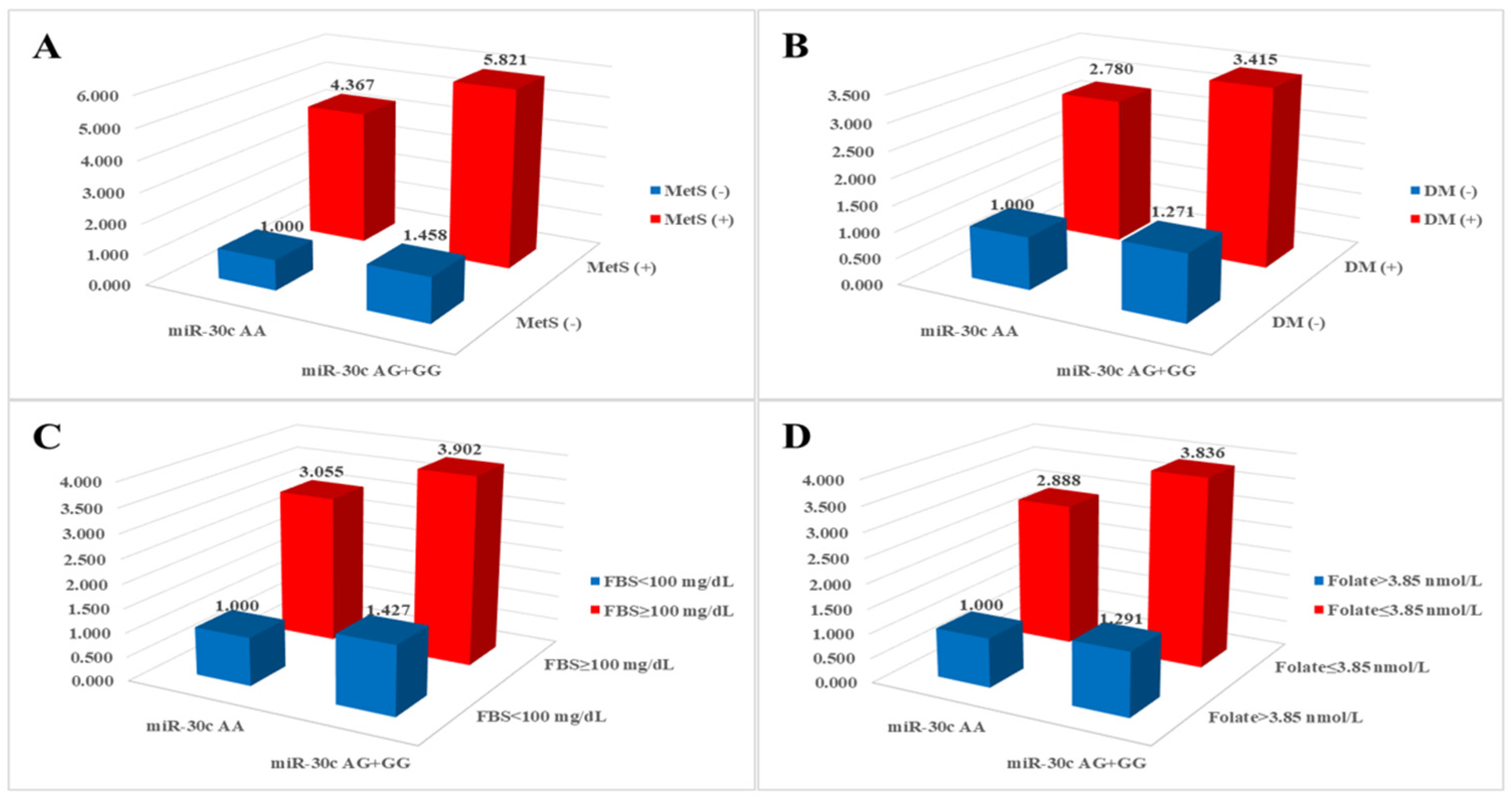

2.5. Synergistic Effects of miRNA Polymorphisms and Clinical Parameters

We investigated the combined effects of miRNA polymorphisms and clinical parameters and found that various clinical parameters exhibited synergistic effects with miRNA polymorphisms (Table S2). Specifically, MetS-related clinical parameters in conjunction with miR-30c rs928508 were significantly associated with an elevated risk of CAD, as illustrated in Figure 1. The AOR for individuals with the miR-30c rs928508 AG + GG genotypes and diabetes mellitus, fasting blood sugar ≥ 100 mg/dL, and folate ≤ 3.85 nmol/L was 3.415 (p < 0.0001), 3.902 (p < 0.0001), and 3.836 (p < 0.0001), respectively.

Figure 1.

Analysis of synergistic effects on coronary artery disease risk between miR-30c rs928508 and (A) metabolic syndrome (MetS), (B) diabetes mellitus (DM), (C) fasting blood sugar (FBS), and (D) folate.

3. Discussion

We evaluated associations between CAD risk and five polymorphisms in miRNAs targeting the 3′-UTR of PAI-1. Associations have been reported between these five polymorphisms and other diseases, including non-small-cell lung cancer (miR-30c rs928508) [19], colorectal cancer (miR-143 rs41291957) [20], ischemic stroke (miR-143 rs4705342) [21], atherosclerosis (miR-145 rs353291) [22], and methamphetamine addiction (miR-181a2 rs10760371) [23]. However, only miR-143 rs41291957 was previously investigated in relation to CAD [24]. Furthermore, although these SNPs have been studied in many countries, they have not been analyzed in Korea. Thus, to our knowledge, our study represents the first attempt to elucidate the effect of these five miRNA SNPs on the prevalence of CAD in Koreans.

In a prior study, miR-34a was shown to bind to the 3′UTR of PAI-1 and regulate PAI-1 expression, with miR-34a overexpression leading to reduced expression of PAI-1 [25]. Similarly, miR-143, another miRNA investigated in this study, was reported to bind to the 3′UTR of PAI-1 and inhibit its expression [26]. Thus, published findings indicate that miRNA binding to PAI-1 lowers the expression level of this gene. PAI-1 encodes a protein that inhibits tPA and uPA, disrupts the fibrinolytic system, and contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Accordingly, elevated expression of PAI-1 leads to an increased risk for CAD [27]. Based on the above, we predict that binding of miRNA to the PAI-1 3′UTR reduces PAI-1 expression and lowers the risk for CAD. In our study, CAD risk was significantly increased for those with the GG genotype of miR-30c rs928508 (Table 2). This observation suggests that individuals with GG genotype have an elevated incidence of CAD, resulting from reduced expression of miR-30c and increased expression of PAI-1 relative to those with the AA genotype.

CAD is a complex condition influenced by a variety of environmental and genetic risk factors, including PAI-1 and its associated miRNAs [28,29,30,31]. Several studies have indicated a strong association between components of MetS and atherosclerotic diseases, including CAD [32,33]. Based on the ATP III criteria, a diagnosis of MetS is established when an individual exhibits three or more of the following five criteria: blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg, waist circumference > 102 cm in males or >88 cm in females, fasting blood sugar ≥ 110 mg/dL, plasma triglyceride concentration ≥ 150 mg/dL, and plasma HDL-cholesterol concentration < 40 mg/dL in males or <50 mg/dL in females [34]. Diabetes mellitus, another clinical characteristic, is also associated with CAD [35,36]. On the other hand, genetic predisposition to elevated folate levels was linked to a reduced likelihood of developing CAD [37]. Combinations of miR-30c rs928508 genotypes and risk factors associated with MetS demonstrated synergistic elevation of risk for CAD, as illustrated in Figure 1. Subgroups characterized by the miR-30c AG + GG genotypes and the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and HDL < 40 mg/dL (males) or <50 mg/dL (females) displayed significantly increased AORs (2.246, 3.415, 1.675, 1.887, and 2.008, respectively) compared with subgroups with the miR-30c AA genotype without MetS-related conditions (Table S2). Consistent with our findings, MetS was also shown to be an important risk factor for CAD in patients from other ethnic groups [38,39].

Our study has several limitations. First, although the regulatory effect of miRNA on PAI-1 is known [25,26], the specific mechanisms through which the five SNPs impact the development of CAD are not fully understood. Therefore, further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to validate the effects of the SNPs on CAD risk and enhance our understanding for future applications. Second, our study sample was limited to the Korean population, which restricts the generalizability of our findings. We further note that the frequencies of these polymorphisms in the Korean population differ slightly from those in other populations, making it difficult to extend our conclusions to a global context. Consequently, it is crucial to expand our research to encompass a more diverse range of patient samples. Third, there is a dearth of information regarding other environmental risk factors for CAD.

In summary, we evaluated whether five polymorphisms of PAI-1-related miRNAs affect susceptibility to CAD in the Korean population. We found that miR-30c rs928508 was associated with CAD risk. In combination analyses, some combinations of miR-30c rs928508, miR-143 rs41291957, and miR-143 rs4705342 alleles and genotypes were also associated with increased or decreased CAD risk. Moreover, these three polymorphisms displayed synergistic effects on CAD risk when combined with clinical conditions that independently increase the risk of CAD. These findings can be used to identify new CAD prognostic biomarkers using miR-30c rs928508, miR-143 rs41291957, and miR-143 rs4705342 combined with other miRNA polymorphisms and various clinical factors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Participants

Blood samples were obtained from 483 patients with CAD [age, mean ± standard deviation (SD) = 61.07 ± 11.46 years] and 400 age- and sex-matched healthy control participants (age, mean ± SD = 60.56 ± 11.70 years). All participants were recruited from the Department of Cardiology of CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, in Seongnam, South Korea, between 2014 and 2016. All participants provided written informed consent for the study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHA Bundang Medical Center (IRB number: 2013-10-114). All study procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The patients included in this study exhibited coronary artery stenosis of over 50% in at least one of the primary coronary arteries or their significant branches, as verified by coronary angiography. Patients with a history of cardiac arrest and a life expectancy of less than one year were excluded to mitigate the confounding effects of diverse medical interventions on blood testing. Diagnoses were established via coronary angiography and were corroborated by at least one proficient cardiologist. The 400 control participants were seen at the Department of Cardiology at the CHA Bundang Medical Center for a thorough health assessment, which included biochemical testing and cardiological examination. Individuals with a history of angina or myocardial infarction, as well as those exhibiting T wave inversion on electrocardiography, were excluded from the control cohort.

Hypertension was characterized by systolic pressure ≥ 130 mmHg and diastolic pressure ≥ 80 mmHg and was considered present in individuals using anti-hypertensive medications [40]. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 110 mg/dL and was considered present in individuals taking medications for diabetes. Hyperlipidemia was defined as fasting serum total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 150 mg/dL or a history of treatment with anti-hyperlipidemic agents. Smoking status referred to individuals currently engaged in smoking [18].

4.2. Blood Biochemical Analyses

Blood (2 mL) was obtained in tubes containing anticoagulant after a 12 h fasting period. To isolate plasma from whole blood, the samples were centrifuged at 1000× g for 15 min. Plasma concentrations of homocysteine and folate were measured using the IMx fluorescence polarizing immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and a radioimmunoassay kit (ACS:180; Bayer, Tarrytown, NY, USA), respectively. The levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol were determined by colorimetric enzymatic methods using commercial reagent sets (TBA 200FR NEO, Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan).

4.3. SNP Selection

To identify miRNAs that bind to PAI-1 mRNA, an online search was performed using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org, accessed on 5 September 2023) (Figure S1) and TarBase v8 databases (DIANA tools—TarBase v8 (uth.gr), accessed on 5 September 2023) (Figure S2). The targeted mRNA sequences, primarily located in the 3′-UTR, were acquired from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 5 September 2023). We first selected overlapping SNPs from the results of an online search. We then searched the SNPs in NCBI and selected only those found in East Asian populations and with an alternative allele frequency of ≥0.05.

4.4. Genetic Analyses

DNA was isolated from white blood cells in peripheral blood using the G-dex II Genomic DNA Extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Seongnam, Republic of Korea), following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer. After extraction, the quantity (A260) and quality (A260/A280 ratio) of genomic DNA were promptly evaluated with a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Genomic DNA purity was further confirmed by analyzing the patterns of DNA fragments obtained from agarose gel electrophoresis.

miR-30c rs928508 A > G, miR-143 rs41291957 G > A, miR-143 rs4705342 T > C, miR-145 rs353291 T > C, and miR-181a2 rs10760371 T > G were genotyped using a TaqMan™ SNP Genotyping Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with a Rotor-Gene 6000 Real-Time PCR System (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). A solution was prepared for real-time PCR by combining 1 µL genomic DNA (100 ng/µL), 7.5 µL TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.75 µL TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems), and distilled water to achieve a final volume of 15 µL. The experimental procedure included appropriate negative controls. The thermal cycling conditions for this experiment were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing at 60 °C for 1 min [41]. To confirm the genotypes, 30% of the samples for each polymorphism were randomly selected and subjected to base sequence analysis using an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequencing results were 100% consistent with the genotyping results. Primer sequences for the five SNPs are listed in Table S3.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

To compare clinical characteristics between the controls and the patients with CAD, Chi-square tests and Student’s t-tests were used for categorical data and continuous data, respectively. Logistic regression was used to estimate associations between the polymorphisms and CAD risk. The AORs were adjusted by age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking status. Genotyping was performed by treating the most common homozygous genotype as the dominant model and the less common homozygous genotype as the recessive model. To minimize false positives in the results, a false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to the p-values using the formula q = p * (n/k), where n represents the total number of p-values and k indicates the rank of the p-values when arranged from smallest to largest [42]. One-way analysis of variance was performed to investigate the differences in various clinical factors depending on the genotypes of the polymorphisms. Statistical significance was accepted at the p < 0.05 level. The allele frequencies obtained from each cohort were calculated to assess the adherence or departure from HWE. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and Medcalc version 12.7.1.0 (Medcalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Haplotypes for multiple loci were estimated using the expectation–maximization algorithm with SNPAlyze (version 5.1; DYNACOM Co, Ltd., Yokohama, Japan).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms252111528/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.H. and N.K.K.; methodology, C.S.R. and E.J.K.; validation, Y.H.H., J.H.S. and I.J.K.; formal analysis, Y.H.H. and J.H.S.; investigation, E.J.K., H.W.P. and H.S.P.; resources, J.H.S. and O.J.K.; data curation, Y.H.H. and J.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.H., J.H.S., I.J.K. and N.K.K.; visualization, C.S.R., E.J.K. and H.S.P.; supervision, I.J.K. and N.K.K.; project administration, I.J.K. and N.K.K.; funding acquisition, O.J.K., I.J.K. and N.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2021R1G1A1094307, 2022R1F1A1076255).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of CHA Bundang Medical Center reviewed and approved this study (IRB number: 2013-10-114).

Informed Consent Statement

The Institutional Review Board of CHA Bundang Medical Center approved this study. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in this study for the publication of this paper (IRB number: 2013-10-114).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Park, H.S.; Kim, I.J.; Kim, E.G.; Ryu, C.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Ko, E.J.; Park, H.W.; Sung, J.H.; Kim, N.K. A study of associations between CUBN, HNF1A, and LIPC gene polymorphisms and coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMahon, S.; Peto, R.; Cutler, J.; Collins, R.; Sorlie, P.; Neaton, J.; Abbott, R.; Godwin, J.; Dyer, A.; Stamler, J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: Prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990, 335, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, R. The health benefits of smoking cessation. Ir. Med. J. 1990, 83, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stamler, J.; Vaccaro, O.; Neaton, J.D.; Wentworth, D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuren, W.M.; Jacobs, D.R.; Bloemberg, B.P.; Kromhout, D.; Menotti, A.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Buzina, R.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.; et al. Serum total cholesterol and long-term coronary heart disease mortality in different cultures. Twenty-five-year follow-up of the seven countries study. JAMA 1995, 274, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, N.; Hassine, M.; Fodha, H.; Ben Messaoud, M.; Maatouk, F.; Gamra, H.; Ferchichi, S. Association of the methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase gene rs1801133 C677T variant with serum homocysteine levels, and the severity of coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.J.; Kim, S.H.; Cha, D.H.; Lim, S.W.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, J.O.; Ryu, C.S.; Park, H.S.; Sung, J.H.; Kim, N.K. Association of COX2 -765G>C promoter polymorphism and coronary artery disease in Korean population. Genes Genomics 2019, 41, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Ouyang, M.; Yang, K. PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism and coronary artery disease risk: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.M.; Carvalho, M.; Fonseca Neto, C.P.; Garcia, J.C.; Sousa, M.O. PAI-1 4G/5G polymorphism and plasma levels association in patients with coronary artery disease. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2011, 97, 462-386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.M.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X.M.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, S.S.; Zhu, Y.H. Biological mechanism analysis of acute renal allograft rejection: Integrated of mRNA and microRNA expression profiles. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 5170–5180. [Google Scholar]

- Kayano, M.; Higaki, S.; Satoh, J.I.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsubara, E.; Takikawa, O.; Niida, S. Plasma microRNA biomarker detection for mild cognitive impairment using differential correlation analysis. Biomark. Res. 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, I.; Parhar, I. MicroRNAs Regulate Cell Cycle and Cell Death Pathways in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, E.M.; Frost, R.J.; Olson, E.N. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2010, 121, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Gholipour, M.; Taheri, M. Role of MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 632392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andiappan, R.; Govindan, R.; Ramasamy, T.; Poomarimuthu, M. Circulating miR-133a-3p and miR-451a as potential biomarkers for diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol. 2024, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.G.; Motazedian, P.; Ramirez, F.D.; Simard, T.; Di Santo, P.; Visintini, S.; Faraz, M.A.; Labinaz, A.; Jung, Y.; Hibbert, B. Association between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb. J. 2018, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.S.; Wilhelm, S.M.; Pentland, A.P.; Marmer, B.L.; Grant, G.A.; Eisen, A.Z.; Goldberg, G.I. Tissue cooperation in a proteolytic cascade activating human interstitial collagenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 2632–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Sung, J.H.; Ryu, C.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Ko, E.J.; Kim, I.J.; Kim, N.K. The Synergistic Effect of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) Polymorphisms and Metabolic Syndrome on Coronary Artery Disease in the Korean Population. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Shu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Pan, S.; Xu, L.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the precursor MicroRNA flanking region and non-small cell lung cancer survival. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pan, X.; Li, Z.; Bai, P.; Jin, H.; Wang, T.; Song, C.; Zhang, L.; Gao, L. Association between polymorphisms in the promoter region of miR-143/145 and risk of colorectal cancer. Hum. Immunol. 2013, 74, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.S.; Xiang, Y.; Liao, P.H.; Wang, J.L.; Peng, Y.F. An rs4705342 T>C polymorphism in the promoter of miR-143/145 is associated with a decreased risk of ischemic stroke. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Yi, Y.; Jia, S.; Peng, X.; Yang, H.; Guo, R. The miR-145 rs353291 C allele increases susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Front. Biosci. 2020, 25, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Su, H.; Chen, T.; Jiang, H.; Du, J.; Zhong, N.; Yu, S.; Zhao, M. An association study between methamphetamine use disorder with psychosis and polymorphisms in MiRNA. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 717, 134725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, I.F.; Climent, M.; Viviani Anselmi, C.; Papa, L.; Tragante, V.; Lambroia, L.; Farina, F.M.; Kleber, M.E.; März, W.; Biguori, C.; et al. rs41291957 controls miR-143 and miR-145 expression and impacts coronary artery disease risk. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e14060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Y. miR-34a exerts as a key regulator in the dedifferentiation of osteosarcoma via PAI-1-Sox2 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahata, M.; Osaki, M.; Kanda, Y.; Sugimoto, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Takeshita, F.; Fujiwara, T.; Kawai, A.; Ito, H.; et al. PAI-1, a target gene of miR-143, regulates invasion and metastasis by upregulating MMP-13 expression of human osteosarcoma. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillen, M.; Declerck, P.J. Targeting PAI-1 in Cardiovascular Disease: Structural Insights Into PAI-1 Functionality and Inhibition. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 622473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiannitopoulos, K.; Samara, P.; Papadopoulou, M.; Efthymiadou, A.; Papadopoulou, E.; Tsaousis, G.N.; Mertzanos, G.; Babalis, D.; Lamnissou, K. miRNA polymorphisms and risk of premature coronary artery disease. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 2021, 62, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, A.K.; Choudhury, D.; Halder, B.; Paul, P.; Uddin, A.; Chakraborty, S. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 16812–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarecka, B.; Zak, I.; Krauze, J. Synergistic effects of the polymorphisms in the PAI-1 and IL-6 genes with smoking in determining their associated risk with coronary artery disease. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 41, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Zhou, H. Expression profiles and bioinformatic analysis of microRNAs in myocardium of diabetic cardiomyopathy mice. Genes Genomics 2023, 45, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidi, W.; Allal-Elasmi, M.; Zayani, Y.; Zaroui, A.; Guizani, I.; Feki, M.; Mourali, M.S.; Mechmeche, R.; Kaabachi, N. Metabolic Syndrome, Independent Predictor for Coronary Artery Disease. Clin. Lab. 2015, 61, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, A.; Johnson, B.D.; Anderson, R.D.; Bavry, A.A.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M.; Handberg, E.M.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Nicholls, S.J.; Nissen, S.; Pepine, C.J. Relationships between components of metabolic syndrome and coronary intravascular ultrasound atherosclerosis measures in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: The NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. 2015, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [CrossRef]

- Aronson, D.; Edelman, E.R. Coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus. Cardiol. Clin. 2014, 32, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarson, T.R.; Acs, A.; Ludwig, C.; Panton, U.H. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: A systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Mason, A.M.; Carter, P.; Burgess, S.; Larsson, S.C. Homocysteine, B vitamins, and cardiovascular disease: A Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerifar, F.; Bolouri, A.; Mahmoudi Mozaffar, M.; Karajibani, M. The Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Cardiol. Res. 2016, 7, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammary, A.F.; Alharbi, K.K.; Alshehri, N.J.; Vennu, V.; Ali Khan, I. Metabolic Syndrome and Coronary Artery Disease Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.M.; Jamal, S.F. Essential Hypertension. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Ko, E.J.; Kim, Y.R.; Cho, H.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Ahn, E.H.; Kim, N.K. Association Study between Mucin 4 (MUC4) Polymorphisms and Idiopathic Recurrent Pregnancy Loss in a Korean Population. Genes. 2022, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, W.; He, K.; Chen, M. IL1RL1 polymorphisms rs12479210 and rs1420101 are associated with increased lung cancer risk in the Chinese Han population. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1183528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).