Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has claimed over 7 million lives worldwide, providing a stark reminder of the importance of pandemic preparedness. Due to the lack of approved antiviral drugs effective against coronaviruses at the start of the pandemic, the world largely relied on repurposed efforts. Here, we summarise results from randomised controlled trials to date, as well as selected in vitro data of directly acting antivirals, host-targeting antivirals, and immunomodulatory drugs. Overall, repurposing efforts evaluating directly acting antivirals targeting other viral families were largely unsuccessful, whereas several immunomodulatory drugs led to clinical improvement in hospitalised patients with severe disease. In addition, accelerated drug discovery efforts during the pandemic progressed to multiple novel directly acting antivirals with clinical efficacy, including small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. We argue that large-scale investment is required to prepare for future pandemics; both to develop an arsenal of broad-spectrum antivirals beyond coronaviruses and build worldwide clinical trial networks that can be rapidly utilised.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic highlighted the world’s under-preparedness when faced with a newly emerging viral pathogen, for which no specific antiviral therapy was available [1]. Coronaviruses that cause human infections include alphacoronaviruses human coronavirus (HCoV) 229E and HCoV NL63, and betacoronaviruses HCoV OC43, HCoV HKU1, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1) [2,3,4]. However, over the past two decades, the world has witnessed the emergence of several highly pathogenic betacoronaviruses, with mortality rates ranging from 10% for SARS-CoV-1 in 2002, 34% for MERS-CoV in 2012, and 2% for SARS-CoV-2 in 2019, respectively [5,6]. While the spread of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV was contained through public health measures, SARS-CoV-2 caused a global pandemic with more than 771.68 million cases recorded and 6.98 million confirmed deaths (Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-deaths-and-cases-covid-19, as of 2 November 2023). SARS-CoV-2 is highly transmissible and can cause asymptomatic or mild symptoms, which makes preventing its spread more difficult [6,7,8]. New variants of SARS-CoV-2 keep emerging, with Omicron being up to 70% more transmissible than previously circulating virus variants [9,10].

Table 1.

Coronaviruses with a history of pathogenicity in humans and their respective cellular entry receptors.

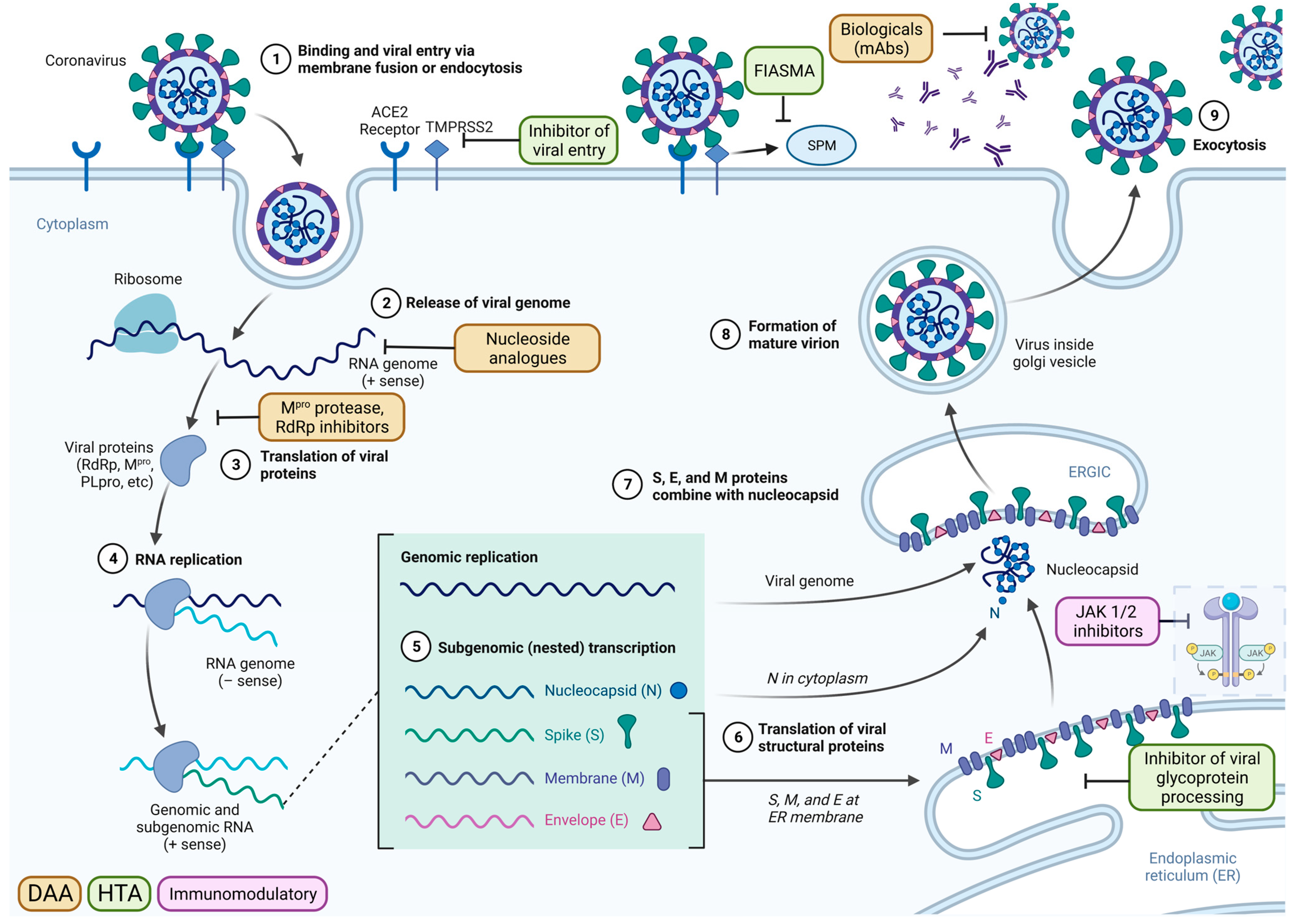

At the start of the 2019 pandemic, no therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2 were available. The SARS-CoV-2 life cycle provides insight into antiviral drug targets (Figure 1), with key targets that were exploited for the development of directly acting antivirals (DAA) and host-targeting antivirals (HTA) marked. DAAs target essential viral proteins, such as the main protease (MPro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), while host-targeting antivirals inhibit human proteins that the virus utilises for its entry, replication, or assembly.

Figure 1.

The coronavirus life cycle and the mechanistic actions of antiviral drugs within the viral replication process, using SARS-CoV-2 as an example. The virus-cell membrane fusion was induced by the binding of spike protein to the host cellular receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), together with the cell surface transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2). Following viral entry, the release of the viral genome is followed by the immediate translation of viral proteins and the formation of the viral replication and transcription complex. The 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (CLpro)/main protease (Mpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) cleave the virus polypeptide into 16 non-structural proteins. Structural glycoproteins are synthesised in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane for transit through the endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). Newly synthesised genomic RNA is encapsulated and buds into the ERGIC to form a virion. New virions leave the cell via lysosomes and are then able to infect new susceptible cells. SARS-CoV-2 infection activates the acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide system, resulting in the formation of ceramide-enriched membrane domains that serve viral entry and infection by clustering ACE2. The directly acting antivirals (DAA) mechanisms include the monoclonal antibodies that target the spike protein of the virus, Mpro inhibitor, nucleoside analogues, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitor. The host-targeting antivirals (HTA) include the inhibitors of viral entry, functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase activity (FIASMA), and inhibitors of viral glycoprotein processing. The immunomodulatory drugs modify the negative effects of an overreacting immune system, such as the interleukins and JAK ½ inhibitors. Adapted from “Coronavirus Replication Cycle”, by BioRender.com (2023). Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates, accessed on 20 April 2023.

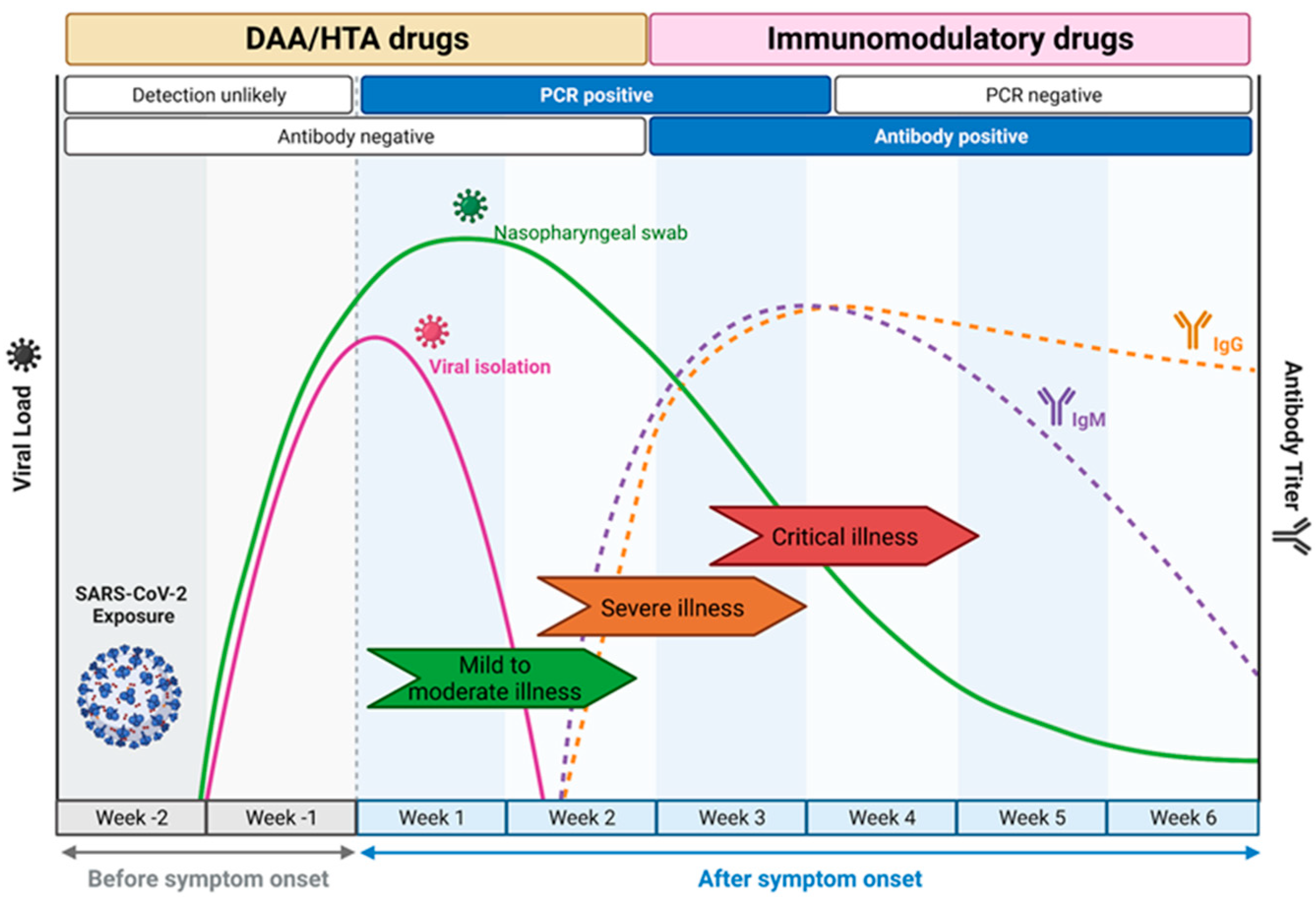

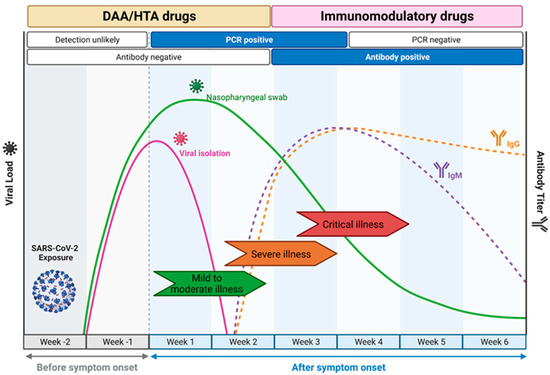

The choice of drug Is closely linked to the course of natural infection (Figure 2) [11]. DAA and HTA are most suited for use within the first week of infection as they target viral replication. This leads to a short window of opportunity for treatment, as patients often only seek medical attention a few days after symptoms develop [12,13]. In contrast, during later stages of disease, the immune system rather than viral replication as such is the main driver of disease progression, and here, immunomodulatory drugs were shown to be effective [14].

Figure 2.

COVID-19 disease progression and the windows of opportunities where antiviral drugs should be deployed. The directly acting antivirals (DAA) and host-targeting antivirals (HTA) are most effective for an intervention in the earlier course of the mild to moderate disease manifestation when viral load is increasing and detectable by RT-PCR. The immunomodulatory drugs are more potent in the later phase of the disease when the host immune response starts to develop as a response to the infection and the clinical manifestation starts to develop from severe to critical illness due to the risks of a cytokine storm. Adapted from “Time Course of COVID-19 Infection and Test Positivity”, by BioRender.com (2023). Retrieved from https://app.biorender.com/biorender-templates, accessed on 20 April 2023.

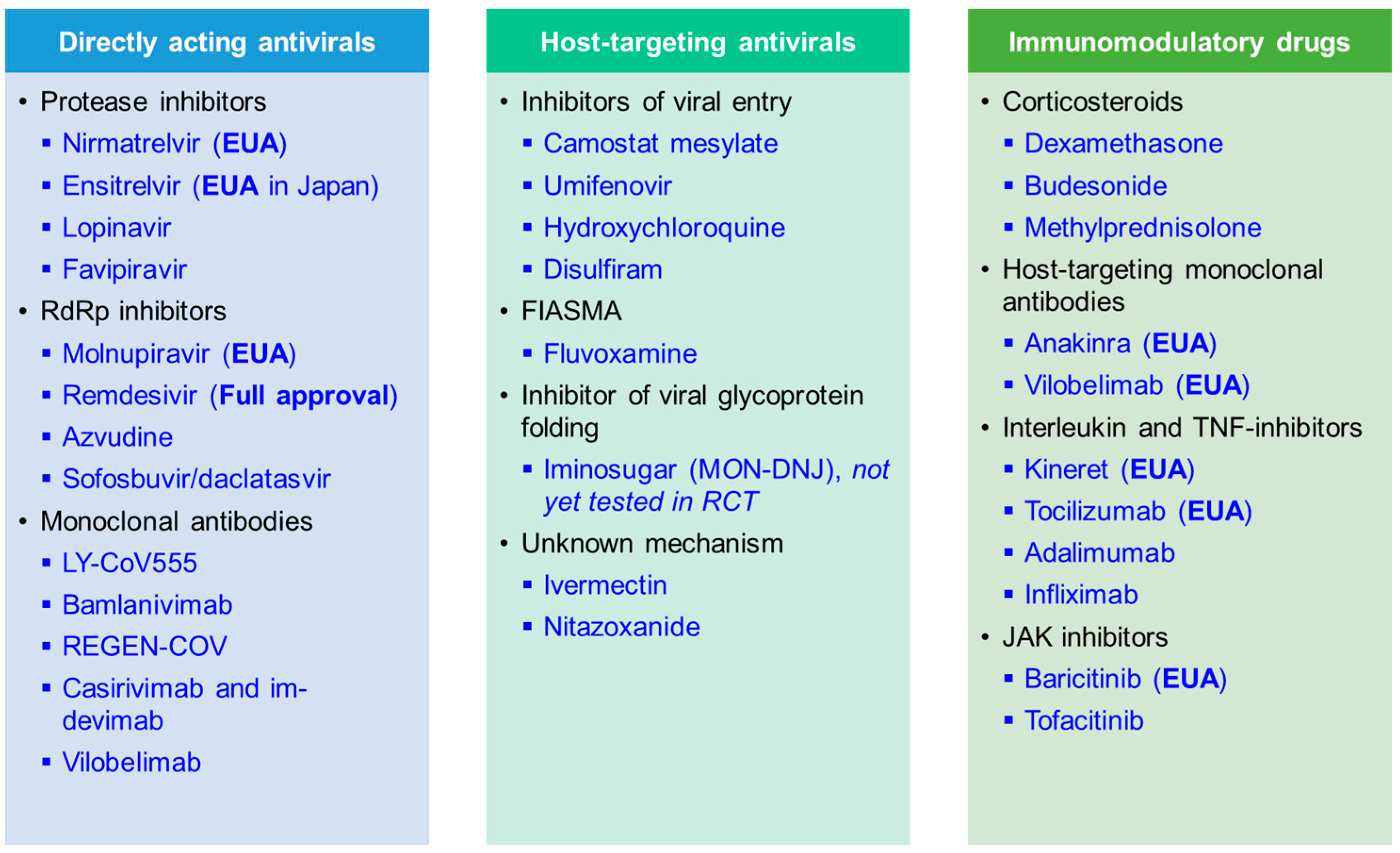

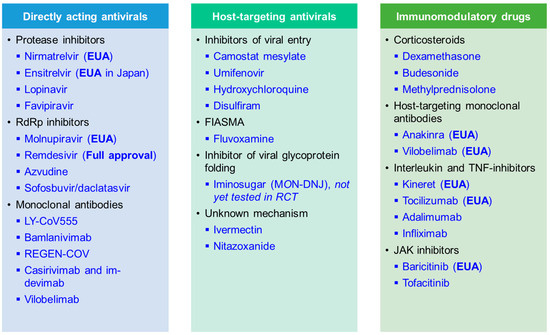

Here, we summarise recent results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with linked in vitro results that were performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. We present data on key candidate compounds with a direct impact on virally encoded proteins (DAA), indirect mechanisms of action depriving the virus of essential host factors needed for replication and spread (HTA), and immunomodulatory compounds (Figure 3). An overview of compounds that are now fully approved or under emergency use authorisation (EUA) for COVID-19 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is shown in Table 2. Further, the World Health Organization (WHO) is releasing a living update on COVID-19 therapeutics [15]. In this review, we will summarise clinical trial results of now authorised compounds and highlight other drugs that were shown to be ineffective.

Figure 3.

Summary of compounds discussed in this review article, including directly acting antiviral (DAA), host-targeting antiviral (HTA), and immunomodulatory drugs. Therapeutics that received full approval and emergency use authorisation (EUA) for COVID-19 are marked in the table. FIASMA, Functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase activity.

Table 2.

Biologicals and small molecule antiviral drugs granted full approval or emergency use authorisation (EUA) for the treatment of COVID-19 from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) *.

4. Immunomodulatory Drugs

Immunomodulatory drugs are commonly used in autoimmune disease and include both monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors. They can either target cytokines directly, such as monoclonal antibodies against interleukins (ILs) or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, inhibit proteins involved in inflammatory signalling pathways such as the janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, or interfere with the hormonal regulation of inflammation such as corticosteroids [219,220]. Multiple monoclonal antibodies and immunomodulatory compounds were evaluated in COVID-19 infection (Table 6), driven by the aim to impact on COVID-19 associated systemic inflammation that can be associated with heightened cytokine release, as indicated by elevated blood levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer and ferritin [221,222,223,224]. Crucial for the assessment of the effects of immunomodulatory drugs were large-scale platform trials initiated early in the pandemic.

4.1. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids bind to the glucocorticoid receptor and inhibit the synthesis of multiple inflammatory proteins through the suppression of genes that encode them, as well as promoting anti-inflammatory signals [224,225]. Coordinated from Oxford, the open-label RECOVERY trial recruited over 43,000 hospitalised patients with COVID-19 participants worldwide and randomly assigned patients to treatment groups that included dexamethasone, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir-ritonavir, or azithromycin, and compared them to usual care, with the primary endpoint mortality at 28 days [226]. Dexamethasone treatment significantly decreased mortality in patients who were receiving either invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen alone at randomization [14]. Another inhaled corticosteroid, budesonide, was assessed in the PRINCIPLE study in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19, and improved recovery time with the potential to reduce hospital admissions or deaths [227].

4.2. Host-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies

Multiple immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies, directed against cytokines such as against tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6, were assessed in COVID-19 patients [224]. Tocilizumab is a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody that binds to interleukin-6 receptors, thereby blocking the activity of the pro-inflammatory cytokine. IL-6 is produced by a variety of cell types including lymphocytes, monocytes, and fibroblasts, and has been shown to be induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection in bronchial epithelial cells. The IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab is in clinical use for several inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. As of 24 June 2021, the FDA has authorised the use of tocilizumab under EUA for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalised adults who are receiving systemic corticosteroids and require supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [228]. The authorisation was based on the results of 4 clinical trials: RECOVERY, EMPACTA, COVACTA, and REMDACTA (Table 6), with the decision to grant EUA mainly based on the positive results of RECOVERY and EMPACTA that demonstrated an impact on mortality and a composite readout of mechanical ventilation and mortality [30,229].

IL-1 inhibitors include the IL-1 receptor antagonist Kineret (brand name anakinra), the IL-1 “Trap” rilonacept, and the neutralising monoclonal antibody to IL-1β canakinumab [224,230]. Anakinra was considered a safe and efficient treatment for severe forms of COVID-19 with a significant survival benefit in critically ill patients and features of macrophage activation-like syndrome [20,21], with most RCTs supporting the clinical benefit of this drug for COVID-19 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Immunomodulatory drugs tested in clinical trials for COVID-19.

Table 6.

Immunomodulatory drugs tested in clinical trials for COVID-19.

| Drug Name | Initial Development Target | Mechanism | Trial Attributes | Clinical Trial Settings | Readout | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A prospective, open-label, interventional study in adults hospitalised with severe COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 69) in Oman in 2020. | A significant reduction in inflammatory biomarkers and may confer clinical benefit. | [231] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A multi-centre, open-label, Bayesian randomised clinical trial in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 116) in France in 2020 (CORIMUNO-ANA-1 study). | No improved outcomes in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 pneumonia compared to usual care. | [232] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | An open-label trial in patients with COVID-19 (n = 130) in Greece in 2020. | A decreased risk of progression into severe respiratory failure. | [233] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A prospective, multi-centre, open-label, randomised, controlled trial, in hospitalised patients with COVID-19, hypoxia, and signs of a cytokine release syndrome (n = 342) in Belgium in 2020. | No reduction of the time to clinical improvement. | [234] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A double-blind, randomised controlled trial in patients with COVID-19 at risk of progressing to respiratory failure (n = 606) in Greece between Dec 2020 and Mar 2021 (SAVE-MORE study). | A decrease in the 28-day mortality and shorter duration of hospital stay. | [235] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | An open-label prospective trial (n = 102) in Greece in 2020 (ESCAPE study). | Favorable responses among critically ill patients with COVID-19 and features of MALS. | [21] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | An open-label, randomised, controlled trial in patients confirmed with COVID-19 (n = 30) in Iran in 2020. | Reduced need for mechanical ventilation and the hospital length of stay. | [236] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A controlled, open-label trial in adults with COVID-19 requiring oxygen (n = 71) at 20 sites in France in 2020 (ANACONDA study). | No efficacy compared to the standard of care. | [237] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | An open-label, multi-centre, randomised clinical trial in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection, evidence of respiratory distress, and signs of cytokine release syndrome (n = 80) in Qatar from October 2020 to April 2021. | No significant improvement compared to the standard of care. | [238] |

| Anakinra | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised, open-label, 2-group, phase 2/3 clinical trial in adult patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation (n = 179) at 12 hospitals in Spain between May 2020 and March 2021 (ANA-COVID-GEAS study). | No reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation or reduction in mortality risk compared with standard of care alone. | [239] |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, controlled, open-label multi-centre trial in COVID-19 (33 patients tocilizumab, 32 patients standard of care) at six hospitals in Anhui and Hubei, China in 2020. | Improvement of hypoxia in the tocilizumab group from day 12. | [32] |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, placebo-controlled, trial in 389 patients hospitalised with COVID-19 pneumonia, randomised to tocilizumab (n = 249) and placebo (n = 128), enrollment from 6 countries in 2020 (EMPACTA). | Reduced likelihood of progression to the composite outcome of mechanical ventilation or death, but no improvement in survival. | [229] |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial in 452 patients in Europe and North America, hospitalised with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, randomised to tocilizumab (n = 294) and placebo (n = 144) in 2020 (COVACTA trial). | Tocilizumab did not result in significantly better clinical status or lower mortality than placebo at 28 days. | [240] |

| Tocilizumab plus remdesivir | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial included patients hospitalised with severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygen (REMDACTA trial), with 649 enrolled patients randomised to tocilizumab plus remdesivir (n = 434) and placebo plus remdesivir (n = 215) in Brazil, Russia, Spain, and the United States between June 2020 and March 2021. | Tocilizumab plus remdesivir did not shorten the time to hospital discharge or “ready for discharge” to day 28 compared with placebo plus remdesivir in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. | [241] |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial with 4116 patients in the United Kingdom with severe COVID pneumonia, randomised to tocilizumab and usual care (n = 2022), or usual care alone (n = 2094), enrolled between April 2020 and January 2021 (RECOVERY study). | Improved survival and other clinical outcomes | [30] |

| Tocilizumab and sarilumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | An international, multifactorial, adaptive platform trial in critically ill adult patients (n = 895) with COVID-19, randomised to tocilizumab (n = 353), sarilumab (n = 48), and standard care control (n = 402) in 2020 (REMAP-CAP study). | Improved clinical outcomes including 90-day survival of clinically ill patients after treatment with tocilizumab or sarilumab compared to the standard care. | [242] |

| Anakinra, tocilizumab, and siltuximab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-1 cytokine inhibitor (anakinra) IL-6 cytokine inhibitor (tocilizumab and siltuximab) | Prospective | A prospective, multi-centre, open-label, randomised, controlled trial in hospitalised patients (n = 342) with COVID-19, hypoxia, and signs of a cytokine release syndrome with a 2 × 2 factorial design to evaluate IL-1 blockade (n = 112) versus no IL-1 blockade (n = 230) and IL-6 blockade (n = 227; 114 for tocilizumab and 113 for siltuximab) versus no IL-6 blockade (n = 115) at 16 hospitals in Belgium in 2020 (COV-AID study). | Drugs targeting IL-1 or IL-6 did not shorten the time to clinical improvement. | [234] |

| Tocilizumab | Rheumatoid arthritis | IL-6 cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (n = 452), assessed for efficacy and safety through day 60, in Europe and North America in 2020 (COVACTA study). | No benefit in reducing mortality up to day 60. | [243] |

| Adalimumab | Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease | TNF-alpha cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised controlled trial in patients (n = 68) in Iran in 2020, where both the intervention and control groups received remdesivir, dexamethasone, and supportive care. | No significant difference between the two groups in terms of mortality rate and mechanical ventilation requirement. No effect on the length of hospital and ICU stay duration as well as radiologic changes. | [244] |

| Namilumab or infliximab | Rheumatoid arthritis | TNF-alpha cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, multi-centre, multi-arm, multi-stage, parallel-group, open-label, adaptive, phase 2, proof-of-concept trial in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 146) in the United Kingdom between June 2020 and February 2021 (CATALYST study). | Namilumab, but not infliximab, showed proof-of-concept evidence for a reduction in inflammation (measured as c-reactive protein/CRP concentration). | [245] |

| Infliximab | Rheumatoid arthritis | TNF-alpha cytokine inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, multi-centre, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial in hospitalised adult patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 146) at 85 clinical research sites in the United States and Latin America between October 2020 and December 2021 (ACTIV-1 study). | No significant difference in time to recovery from COVID-19 pneumonia after treatment with abatacept, cenicriviroc, or infliximab, compared to placebo. | [246] |

| Dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised, open-label, clinical trial in patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 299) at 41 intensive care units in Brazil in 2020 (CoDEX study). | Significant increase in the number of ventilator-free days (days alive and free of mechanical ventilation) over 28 days, compared to standard care alone. | [247] |

| Dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A randomised, controlled, open-label trial (n = 2104) in the United Kingdom in 2020 (RECOVERY study). | Lower 28-day mortality among participants receiving either invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen alone at randomization but not among those receiving no respiratory support. | [14] |

| Dexamethasone (high versus low dose) | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised clinical trial in adults with confirmed COVID-19 requiring oxygen or mechanical ventilation (n = 1000) between August 2020 and May 2021 at 26 hospitals in Europe and India (COVID STEROID 2 study). | No statistically significant difference in more days alive without life support at 28 days. | [248] |

| Dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial in adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit with COVID-19 (n = 546) at 19 sites in France between April 2020 to January 2021 (COVIDICUS study). | No significant improvement in 60-day survival. | [249] |

| Dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A randomised clinical trial between dexamethasone and methylprednisolone groups in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 (n = 143) in Iran in 2021. | Better effectiveness of dexamethasone compared with methylprednisolone. | [250] |

| Dexamethasone (high versus low dose) | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A randomised, open-label, controlled trial involving hospitalised patients with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia needing oxygen therapy (n = 200) in Spain in 2021. | A high dose of dexamethasone reduced clinical worsening within 11 days after randomization, compared with a low dose. | [251] |

| Dexamethasone (high versus low dose) | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised, open-label, clinical trial in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19 (n = 100) in Argentina between June 2020 and March 2021. | No difference in the number of ventilator-free days between high versus low doses. | [252] |

| Budesonide | Ulcerative colitis | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, open-label, multi-arm, randomised, controlled, adaptive platform trial in outpatients (n = 4700) in the United Kingdom between November 2020 and March 2021 (PRINCIPLE study). | Improved time to recovery. | [227] |

| Budesonide | Ulcerative colitis | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised, open-label trial in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 120) in Spain and Argentina from April 2020 to March 2021 (TACTIC study). | Budesonide reduces the risk of disease progression. | [253] |

| Methylprednisolone versus dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A triple-blinded randomised controlled trial in hospitalised COVID-19 patients (n = 86) from August to November 2020 in Shiraz, Iran. | Methylprednisolone showed better efficacy than dexamethasone. | [254] |

| Methylprednisolone and dexamethasone | Arthritis and other inflammatory conditions | Corticosteroids | Prospective | A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 304) at 19 centres in Italy between December 2020 and March 2021. | No benefit in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. | [255] |

| Baricitinib | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | A multi-centre, phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial (n = 1525) at 101 centres across 12 countries in Asia, Europe, North America, and South America, between June 2020 and January 2021 (COV-BARRIER study). | No significant reduction in the frequency of overall disease progression. | [28] |

| Baricitinib plus remdesivir | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalised adults with COVID-19 (n = 1033) at 67 trial sites in 8 countries: the United States, Singapore, South Korea, Mexico, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Denmark in 2020 (ACTT-2 study). | Combined with remdesivir, baricitinib was beneficial in reducing recovery time and accelerating improvement in clinical status, compared to remdesivir alone or placebo. | [26] |

| Baricitinib | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (n = 8156) in the United Kingdom in 2021 (RECOVERY study). | Reduced mortality in patients compared to standard of care alone. | [256] |

| Baricitinib versus dexamethasone | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | A multi-centre randomised, double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen by low-flow, high-flow, or non-invasive ventilation (n = 1010) at 67 trial sites in the United States, South Korea, Mexico, Singapore, and Japan, between December 2020 and April 2021 (ACTT-4 study). | Similar mechanical ventilation-free survival by day 29 between groups, while dexamethasone was associated with significantly more adverse events, treatment-related adverse events, and severe or life-threatening adverse events. | [29] |

| Tofacitinib | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | A randomised, placebo-controlled trial in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (n = 289) at 15 sites in Brazil in 2020. | Lower risk of death or respiratory failure than placebo through day 28. | [257] |

| Tofacitinib | Rheumatoid arthritis | Janus kinase inhibitor | Prospective | An open-labeled randomised control study in hospitalised adult patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 100) in India in 2020. | Reduction of the overwhelming inflammatory response compared to the standard care alone. | [258] |

TNF-inhibitors have been used in severe cases of autoimmune inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or ankylosing spondylitis [259]. Several formulations of TNF inhibitors are currently available, including adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab [224]. Elevated serum levels of TNF-α and soluble TNF-Receptor 1 have been detected in COVID-19 patients with severe infection, providing a rationale for the use of TNF-α inhibitors in SARS-CoV-2 infection [260]. However, concerns regarding the potential suppression of antiviral immune responses have been raised by an observational study showing a negative impact on SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels following natural infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab [261,262]. In the CATALYST open-label phase 2 trial, infliximab showed no impact on CRP levels as a measure for inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 infection [245]. Recently reported results of the ACTIV-1 trial, a placebo-controlled, masked, RCT among patients hospitalised for COVID-19, reported a significant benefit of infliximab on mortality [263], but no impact on the primary study endpoint length of pneumonia [246].

The latest addition to monoclonal antibodies under EUA is vilobelimab, a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the soluble human complement C5a, a product of complement activation. C5a activates the innate immune response, including the local release of histamines, contributing to inflammation and local tissue damage. In vivo studies demonstrated that an anti-C5a monoclonal antibody inhibited acute lung injury in a human C5a receptor knock-in mouse model [264]. The phase 3 PANAMO RCT study recorded an improvement in invasive mechanically ventilated patients’ survival that led to a decrease in mortality with the use of vilobelimab [19].

4.3. Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors

The primary mechanism of action of Janus kinases (JAK) is the phosphorylating signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), a key player in signalling pathways involved signalling, growth, survival, inflammation, and immune activation. Inhibiting JAK prevents the phosphorylation of key signalling proteins involved in inflammation pathways, thereby blocking cytokine signalling [224,265]. Tofacitinib and baricitinib are orally available small-molecule JAK inhibitors approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [265] and have been evaluated in multiple RCTs in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading to a treatment recommendation in hospitalised adults that require respiratory support [35]. In brief, baricitinib had an impact on mortality [28,256], as well as reducing intensive care unit admissions, lowering the requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation, and improving patients’ oxygenation index [27,29], effects that were maintained in a meta-analysis [266]. Furthermore, baricitinib in combination with remdesivir showed superior results compared to remdesivir alone in reducing patients’ recovery time and improving their clinical status [26].

In summary, for immunomodulatory drugs, the NIH issued guidelines based on the existing evidence, recommending dexamethasone, tocilizumab, and baricitinib for hospitalised patients with COVID-19, whilst the evidence for anakinra, inhaled corticosteroids, and vilobelimab was deemed inconclusive, despite all compounds receiving EUA from the FDA.

5. Discussion

The devastating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was a stark reminder of the requirement for antiviral compounds that are ready to use against viruses of pandemic potential and emerging viral threads.

A major accomplishment during the pandemic was the rapid implementation of several large platform trials that facilitated the evaluation of various repurposed compounds on COVID-19 hospitalisation and mortality, including DAA, HTA, and immunomodulatory drugs (Figure 3). Due to the time required to develop novel small molecule inhibitors, initial trials focused on immunomodulatory drugs and known antivirals developed against other viruses, followed by rapidly developed monoclonal antibodies to deliver treatments quickly [42,66,246,267]. Based on these RCTs, SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic management guidelines now include several repurposed drugs that were shown to be active against COVID-19. The success of initial repurposing efforts was highly variable for the different compound classes. Several immunomodulatory drugs such as baricitinib, tocilizumab, and dexamethasone improved SARS-CoV-2 disease severity and mortality and are now included in the treatment guidelines for hospitalised patients. Further, repurposing efforts of DAA—that were in the late stages of development but not yet approved at the start of the pandemic—shows the potential to rapidly translate in vivo antiviral activity findings into clinical trials [108]. This holds true for remdesivir and molnupiravir which were developed against the RdRp of RNA viruses EBOV and VEEV, respectively and are also highly effective against the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. In contrast, repurposed DAA approved for HIV, HCV, or influenza, such as lopinavir, favipiravir, darunavir, and danoprevir, showed limited or no clinical activity against SARS-CoV-2 across RCTs. Not surprisingly, repurposed inhibitors of viral proteins that are not expressed by coronaviruses, such as the neuraminidase targeted by oseltamivir, did not show clinical activity [268]. Of note, comparably few repurposed HTA with a plausible mechanism of action were evaluated in large RCTs to date (Table 5).

Numerous in vitro high throughput screens have been conducted since early 2020 to identify potential candidates for repurposing, by screening approved and investigational drug collections [269,270]. However, many trials included compounds based on insufficiently validated cellular screening results, with extensive resources wasted in unnecessary investigations aiming to translate screening hits with marginal cellular activity or false positive data in vitro. This is particularly poignant for compounds causing phospholipidosis, a phenomenon caused by cationic amphiphilic drugs such as Chloroquine or Amiodarone leading to false positive results in vitro due to lipid processing inhibition [271]. Further, many compound libraries that were used in large in vitro screens, such as the ReFRAME library, are skewed towards human proteins, and therefore have, perhaps unsurprisingly, only yielded a few hits of compounds with previously known antiviral activity such as nelfinavir and MK-448 [272]. We, therefore, conclude that in vitro hits should be translated into clinical trials with caution, thoroughly reviewing in vitro and in vivo efficacy in relevant animal models, and, for DAA, establishing a robust pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship and demonstrating consistent exposure over 90% effective concentration/EC90 prior to embarking on resource-demanding clinical trials.

With an abundance of in vitro screening data being generated, the sustainability and maintenance of data repositories is of particular importance, especially downstream for pandemic preparedness. The FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) provide a useful framework and should guide the development of data repositories that capture screening results against viruses of pandemic concern, which may aid pandemic response in the future. The maintenance of existing data repositories for cellular screening results, not only for SARS-CoV-2 but also for other viruses of pandemic concern, is of utmost importance to ensure an efficient pandemic response in the future.

In addition to repurposing efforts, the rapid discovery of novel, SARS-CoV-2 targeting DAA was unprecedented. This includes small molecule inhibitors such as MPro inhibitors nirmatrelvir, based on existing chemical starting points from previous coronavirus protease targets [25], or ensitrelvir, developed through de novo high-throughput screening hits that were progressed using SARS-CoV-2 specific fragment hits [50]. Similar to small molecule DAA efforts, highly efficient monoclonal antibodies designed to neutralise SARS-CoV-2 by binding to the spike protein on its surface were rapidly advanced early in the pandemic. However, many antibodies targeting spike lost their in vitro effectiveness against novel circulating variants such as Omicron and are no longer recommended for clinical use.

Drug resistance has always been the major challenge in drug development against viruses, including coronaviruses [273]. Newly evolving viral strains are linked to recurring waves, with partial immune escape and waning immunity within the population [274,275,276]. In addition, drug-induced viral mutations have been described for SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics, however, so far mostly in immunosuppressed individuals. Further, circulating viruses may harbour variants that are resistant to DAA, such as G15S and T21I that confer resistance to the MPro inhibitor Paxlovid [277,278,279]. The ongoing identification and characterisation of drug-resistant signatures within the SARS-CoV-2 genome will be crucial for clinical management and virus surveillance [280].

The accepted primary trial endpoints by the FDA include all-cause mortality, the need for hospitalisation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and a range of clinical signs such as sustained symptom alleviation [281]. In addition, a virological measure is acceptable as a primary endpoint in a Phase 2 clinical trial, but only as a secondary endpoint in a Phase 3 trial. However, over the last 3 years, circulating viral strains have changed significantly, and both vaccinations and natural infection have led to an increased immunological memory against SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, these endpoints are now less common, leading to discontinued RCTs such as for obeldesivir, due to lower-than-expected hospitalisations or mortality. This also leads to ethical considerations, on whether it is acceptable to enroll patients into a placebo-controlled trial where there is a very low risk of the primary endpoints of death or hospitalisation (e.g., <1%). A promising approach to overcome these issues may include pharmacodynamic modelling of viral clearance [282].

For pandemic preparedness, the concept of “one drug, multiple viruses” carries more promise than a “one drug, one virus” paradigm. Broad-spectrum antiviral agents that inhibit a wide range of human viruses should therefore be the target of de novo pandemic preparedness drug discovery efforts, as well as a focus on HTA that could be deployed immediately [283,284].

The 100-Day Mission set ambitious goals to prepare us for “Disease X”, aiming to generate safe, effective vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics within 100 days of the identification of a novel threat [285]. As well as developing novel assets, their licensing to ensure global and equitable access to future assets remains a key consideration. In the COVID-19 pandemic, the existing international laws and intellectual property practices failed to ensure equitable access to vaccines and therapeutics globally [286]. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, companies appear to have financed their development efforts on the back of large procurement contracts with governments, rather than on the prospect of intellectual property, providing a useful case study for pandemic preparedness [287].

An urgent need remains [35,288] for drugs that can be easily stockpiled to ensure availability for pandemic preparedness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y.A., N.Z. and A.v.D.; Writing and illustrating, B.Y.A. and A.v.D.; Review and editing, J.B., M.L.H., N.Z. and A.v.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

B.Y.A. is funded by Indonesian Education Scholarship (Beasiswa Pendidikan Indonesia) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia (Kemendikbudristek) within a funding scheme from Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; APN, Aminopeptidase N; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CPZ, Chlorpromazine; DAA, Directly acting antivirals; DPP4, Dipeptidyl peptidase 4; EBOV, Ebola virus; EC50, Half-maximum effective concentration; ER, Endoplasmic reticulum; ERQC, Endoplasmic reticulum quality control; ERGIC, Endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi intermediate compartment; EUA, Emergency use authorisation; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FIASMA, Functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase activity; HCoV, Human coronavirus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; HTA, Host-targeting antivirals; IC50, Half maximum inhibitory concentration; IL, Interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; Mpro, Main protease; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PK, pharmacokinetic; RBD, receptor binding domain; RCT, Randomised controlled trial; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; SARS-CoV-1, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 1; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2, Transmembrane serine protease 2; TNF, Tumour Necrosis Factor; VEEV, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; VOC, Variant of concern; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

- Adamson, C.S.; Chibale, K.; Goss, R.J.M.; Jaspars, M.; Newman, D.J.; Dorrington, R.A. Antiviral Drug Discovery: Preparing for the next Pandemic. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3647–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. Human Coronavirus: Host-Pathogen Interaction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartenian, E.; Nandakumar, D.; Lari, A.; Ly, M.; Tucker, J.M.; Glaunsinger, B.A. The Molecular Virology of Coronaviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12910–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artika, I.M.; Dewantari, A.K.; Wiyatno, A. Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses: Current Knowledge. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artese, A.; Svicher, V.; Costa, G.; Salpini, R.; Di Maio, V.C.; Alkhatib, M.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Santoro, M.M.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Alcaro, S.; et al. Current Status of Antivirals and Druggable Targets of SARS CoV-2 and Other Human Pathogenic Coronaviruses. Drug Resist. Updat. Rev. Comment. Antimicrob. Anticancer Chemother. 2020, 53, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrashdy, F.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. Why COVID-19 Transmission Is More Efficient and Aggressive Than Viral Transmission in Previous Coronavirus Epidemics? Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.G.; Lin, T.; Wang, P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.S.A.; Karim, Q.A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variant: A New Chapter in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 398, 2126–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, T. New Variant of SARS-CoV-2 in UK Causes Surge of COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, e20–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, M.; Kuppalli, K.; Kindrachuk, J.; Peiris, M. Virology, Transmission, and Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ 2020, 371, m3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, F.Y.; Macleod, M.D.; Paggiaro, P.; Carewicz, O.; El Sawy, A.; Wat, C.; Griffiths, M.; Waalberg, E.; Ward, P.; IMPACT Study Group. Early Administration of Oral Oseltamivir Increases the Benefits of Influenza Treatment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegivinti, C.T.R.; Evanson, K.W.; Lyons, H.; Akosman, I.; Barrett, A.; Hardy, N.; Kane, B.; Keesari, P.R.; Pulakurthi, Y.S.; Sheffels, E.; et al. Efficacy of Antiviral Therapies for COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2023.1 (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of COVID-19—Final Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.L.; Vaca, C.E.; Paredes, R.; Mera, J.; Webb, B.J.; Perez, G.; Oguchi, G.; Ryan, P.; Nielsen, B.U.; Brown, M.; et al. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe COVID-19 in Outpatients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. FDA Approves Vilobelimab for Emergency Use in Hospitalized Adults. JAMA 2023, 329, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaar, A.P.J.; Witzenrath, M.; van Paassen, P.; Heunks, L.M.A.; Mourvillier, B.; de Bruin, S.; Lim, E.H.T.; Brouwer, M.C.; Tuinman, P.R.; Saraiva, J.F.K.; et al. Anti-C5a Antibody (Vilobelimab) Therapy for Critically Ill, Invasively Mechanically Ventilated Patients with COVID-19 (PANAMO): A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Wang, F.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Perspectives on Anti-IL-1 Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Interventions for Severe COVID-19. Cytokine 2021, 143, 155544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakike, E.; Dalekos, G.N.; Koutsodimitropoulos, I.; Saridaki, M.; Pourzitaki, C.; Papathanakos, G.; Kotsaki, A.; Chalvatzis, S.; Dimakopoulou, V.; Vechlidis, N.; et al. ESCAPE: An Open-Label Trial of Personalized Immunotherapy in Critically Lll COVID-19 Patients. J. Innate Immun. 2021, 14, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayk Bernal, A.; Gomes da Silva, M.M.; Musungaie, D.B.; Kovalchuk, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Delos Reyes, V.; Martín-Quirós, A.; Caraco, Y.; Williams-Diaz, A.; Brown, M.L.; et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of COVID-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-C.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Ko, W.-C. Molnupiravir-A Novel Oral Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simón-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.R.; Allerton, C.M.N.; Anderson, A.S.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Avery, M.; Berritt, S.; Boras, B.; Cardin, R.D.; Carlo, A.; Coffman, K.J.; et al. An Oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitor Clinical Candidate for the Treatment of COVID-19. Science 2021, 374, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, A.C.; Patterson, T.F.; Mehta, A.K.; Tomashek, K.M.; Wolfe, C.R.; Ghazaryan, V.; Marconi, V.C.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Hsieh, L.; Kline, S.; et al. Baricitinib plus Remdesivir for Hospitalized Adults with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Niu, J.; Xu, Y.; Qin, L.; Ding, J.; Zhou, L. Clinical Efficacy and Adverse Events of Baricitinib Treatment for Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 94, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconi, V.C.; Ramanan, A.V.; de Bono, S.; Kartman, C.E.; Krishnan, V.; Liao, R.; Piruzeli, M.L.B.; Goldman, J.D.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.; de Cassia Pellegrini, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Baricitinib for the Treatment of Hospitalised Adults with COVID-19 (COV-BARRIER): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, C.R.; Tomashek, K.M.; Patterson, T.F.; Gomez, C.A.; Marconi, V.C.; Jain, M.K.; Yang, O.O.; Paules, C.I.; Palacios, G.M.R.; Grossberg, R.; et al. Baricitinib versus Dexamethasone for Adults Hospitalised with COVID-19 (ACTT-4): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Double Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abani, O.; Abbas, A.; Abbas, F.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, S.; Abbass, H.; Abbott, A.; Abdallah, N.; Abdelaziz, A.; Abdelfattah, M.; et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Platform Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Amoabeng, D.; Kanji, Z.; Ford, B.; Beutler, B.D.; Riddle, M.S.; Siddiqui, F. Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19 Patients Treated with Tocilizumab: An Individual Patient Data Systematic Review. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2516–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Fu, B.; Peng, Z.; Yang, D.; Han, M.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, T.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; et al. Tocilizumab in Patients with Moderate or Severe COVID-19: A Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label, Multicenter Trial. Front. Med. 2021, 15, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Han, M.; Li, T.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Fu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Effective Treatment of Severe COVID-19 Patients with Tocilizumab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10970–10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorizations for Drugs and Non-Vaccine Biological Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/emergency-preparedness-drugs/emergency-use-authorizations-drugs-and-non-vaccine-biological-products (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Groaz, E.; De Clercq, E.; Herdewijn, P. Anno 2021: Which Antivirals for the Coming Decade? Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2021, 57, 49–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, S.L.; Lim, Y.H.; Lai, N.M.; Lee, S.W.H. Directly Acting Antivirals for COVID-19: Where Do We Stand? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, M.; Tan, X. Current Strategies of Antiviral Drug Discovery for COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 671263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, C.B.; Golden, J.E.; Meibohm, B. Time to “Mind the Gap” in Novel Small Molecule Drug Discovery for Direct-Acting Antivirals for SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 50, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwek, R.A.; Bell, J.I.; Feldmann, M.; Zitzmann, N. Host-Targeting Oral Antiviral Drugs to Prevent Pandemics. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2022, 399, 1381–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.C.; Liew, D.F.L.; Tanner, H.L.; Grainger, J.R.; Dwek, R.A.; Reisler, R.B.; Steinman, L.; Feldmann, M.; Ho, L.-P.; Hussell, T.; et al. COVID-19 Therapeutics: Challenges and Directions for the Future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2119893119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Delft, A.; Hall, M.D.; Kwong, A.D.; Purcell, L.A.; Saikatendu, K.S.; Schmitz, U.; Tallarico, J.A.; Lee, A.A. Accelerating Antiviral Drug Discovery: Lessons from COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boby, M.L.; Fearon, D.; Ferla, M.; Filep, M.; Koekemoer, L.; Robinson, M.C.; The COVID Moonshot Consortium; Chodera, J.D.; Lee, A.A.; London, N.; et al. Open Science Discovery of Potent Noncovalent SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors. Science 2023, 382, eabo7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, W.H.K.; Jittamala, P.; Watson, J.A.; Boyd, S.; Luvira, V.; Siripoon, T.; Ngamprasertchai, T.; Batty, E.M.; Cruz, C.; Callery, J.J.; et al. Antiviral Efficacy of Molnupiravir versus Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir in Patients with Early Symptomatic COVID-19 (PLATCOV): An Open-Label, Phase 2, Randomised, Controlled, Adaptive Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 24, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heskin, J.; Pallett, S.J.C.; Mughal, N.; Davies, G.W.; Moore, L.S.P.; Rayment, M.; Jones, R. Caution Required with Use of Ritonavir-Boosted PF-07321332 in COVID-19 Management. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2022, 399, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DTB Drug Review. Two New Oral Antivirals for COVID-19: ▼molnupiravir and ▼nirmatrelvir plus Ritonavir. Drug Ther. Bull. 2022, 60, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Tignanelli, C.J.; Hoertel, N.; Boulware, D.R.; Usher, M.G. Prevalence of Medical Contraindications to Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir in a Cohort of Hospitalized and Nonhospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, J. Discovery of PF-07817883: A next Generation Oral Protease Inhibitor for the Treatment of COVID-19. Available online: https://acs.digitellinc.com/sessions/584379/view (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Tyndall, J.D.A. S-217622, a 3CL Protease Inhibitor and Clinical Candidate for SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 6496–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unoh, Y.; Uehara, S.; Nakahara, K.; Nobori, H.; Yamatsu, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Maruyama, Y.; Taoda, Y.; Kasamatsu, K.; Suto, T.; et al. Discovery of S-217622, a Noncovalent Oral SARS-CoV-2 3CL Protease Inhibitor Clinical Candidate for Treating COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 6499–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Tabata, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Itakura, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Ariizumi, T.; Uemura, K.; Toba, S.; Kusakabe, S.; Maruyama, Y.; et al. S-217622, a SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitor, Decreases Viral Load and Ameliorates COVID-19 Severity in Hamsters. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukae, H.; Yotsuyanagi, H.; Ohmagari, N.; Doi, Y.; Imamura, T.; Sonoyama, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Ichihashi, G.; Sanaki, T.; Baba, K.; et al. A Randomized Phase 2/3 Study of Ensitrelvir, a Novel Oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-Like Protease Inhibitor, in Japanese Patients with Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19 or Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Results of the Phase 2a Part. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0069722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, I.; Sapountzaki, E.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Inhibition of the Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2 (Mpro) by Repurposing/Designing Drug-like Substances and Utilizing Nature’s Toolbox of Bioactive Compounds. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1306–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidman, D.; Gehrtz, P.; Filep, M.; Fearon, D.; Gabizon, R.; Douangamath, A.; Prilusky, J.; Duberstein, S.; Cohen, G.; Owen, C.D.; et al. An Automatic Pipeline for the Design of Irreversible Derivatives Identifies a Potent SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitor. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Cattaneo, D.; Gervasoni, C.; Corbellino, M.; Galli, M.; Riva, A.; Gervasoni, C.; Clementi, E.; Clementi, E. Does Lopinavir Really Inhibit SARS-CoV-2? Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horby, P.W.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.; Palfreeman, A.; Raw, J.; Elmahi, E.; Prudon, B.; et al. Lopinavir–Ritonavir in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Platform Trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.K.; Patel, P.B.; Barvaliya, M.; Saurabh, M.K.; Bhalla, H.L.; Khosla, P.P. Efficacy and Safety of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashima, K.; Crofoot, G.; Tomaka, F.L.; Kakuda, T.N.; Brochot, A.; Van de Casteele, T.; Opsomer, M.; Garner, W.; Margot, N.; Custodio, J.M.; et al. Cobicistat-Boosted Darunavir in HIV-1-Infected Adults: Week 48 Results of a Phase IIIb, Open-Label Single-Arm Trial. AIDS Res. Ther. 2014, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyer, S.; Bojkova, D.; Cinatl, J.; Van Damme, E.; Buyck, C.; Van Loock, M.; Woodfall, B.; Ciesek, S. Lack of Antiviral Activity of Darunavir against SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Gong, F.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, J.J. First Clinical Study Using HCV Protease Inhibitor Danoprevir to Treat COVID-19 Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e23357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammeltoft, K.A.; Zhou, Y.; Duarte Hernandez, C.R.; Galli, A.; Offersgaard, A.; Costa, R.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Feng, S.; Scheel, T.K.H.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Protease Inhibitors Show Differential Efficacy and Interactions with Remdesivir for Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0268020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Tu, X.; Peng, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ju, W.; Rao, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, D.; et al. A Comparative Study on the Time to Achieve Negative Nucleic Acid Testing and Hospital Stays between Danoprevir and Lopinavir/Ritonavir in the Treatment of Patients with COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, Z.; Lin, W.; Cai, W.; Wen, C.; Guan, Y.; Mo, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Peng, P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lopinavir/Ritonavir or Arbidol in Adult Patients with Mild/Moderate COVID-19: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. N. Y. N 2020, 1, 105–113.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Fan, G.; Ruan, L.; Song, B.; Cai, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, I.F.-N.; Lung, K.-C.; Tso, E.Y.-K.; Liu, R.; Chung, T.W.-H.; Chu, M.-Y.; Ng, Y.-Y.; Lo, J.; Chan, J.; Tam, A.R.; et al. Triple Combination of Interferon Beta-1b, Lopinavir-Ritonavir, and Ribavirin in the Treatment of Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19: An Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 395, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium; Pan, H.; Peto, R.; Henao-Restrepo, A.-M.; Preziosi, M.-P.; Sathiyamoorthy, V.; Abdool Karim, Q.; Alejandria, M.M.; Hernández García, C.; Kieny, M.-P.; et al. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for COVID-19—Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Antinori, A.; Berselli, N.; Blandi, L.; Bonaccio, M.; Bruno, R.; Cauda, R.; Gialluisi, A.; Guaraldi, G.; et al. Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Darunavir/Cobicistat in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: Findings From the Multicenter Italian CORIST Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 639970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Gordon, A.C.; Derde, L.P.G.; Nichol, A.D.; Murthy, S.; Beidh, F.A.; Annane, D.; Swaidan, L.A.; Beane, A.; Beasley, R.; et al. Lopinavir-Ritonavir and Hydroxychloroquine for Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: REMAP-CAP Randomized Controlled Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ader, F.; Peiffer-Smadja, N.; Poissy, J.; Bouscambert-Duchamp, M.; Belhadi, D.; Diallo, A.; Delmas, C.; Saillard, J.; Dechanet, A.; Mercier, N.; et al. An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect of Lopinavir/Ritonavir, Lopinavir/Ritonavir plus IFN-β-1a and Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1826–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xia, L.; Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Ling, Y.; Huang, D.; Huang, W.; Song, S.; Xu, S.; Shen, Y.; et al. Antiviral Activity and Safety of Darunavir/Cobicistat for the Treatment of COVID-19. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimitvilai, S.; Suputtamongkol, Y.; Poolvivatchaikarn, U.; Rassamekulthana, D.; Rongkiettechakorn, N.; Mungaomklang, A.; Assanasaen, S.; Wongsawat, E.; Boonarkart, C.; Sawaengdee, W. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Combined Ivermectin and Zinc Sulfate versus Combined Hydroxychloroquine, Darunavir/Ritonavir, and Zinc Sulfate among Adult Patients with Asymptomatic or Mild Coronavirus-19 Infection. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2022, 14, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmekaty, E.Z.I.; Alibrahim, R.; Hassanin, R.; Eltaib, S.; Elsayed, A.; Rustom, F.; Mohamed Ibrahim, M.I.; Abu Khattab, M.; Al Soub, H.; Al Maslamani, M.; et al. Darunavir-Cobicistat versus Lopinavir-Ritonavir in the Treatment of COVID-19 Infection (DOLCI): A Multicenter Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.P.; Toussi, S.S.; Hackman, F.; Chan, P.L.; Rao, R.; Allen, R.; Van Eyck, L.; Pawlak, S.; Kadar, E.P.; Clark, F.; et al. Innovative Randomized Phase I Study and Dosing Regimen Selection to Accelerate and Inform Pivotal COVID-19 Trial of Nirmatrelvir. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Ma, K.; Fan, C.; Lv, Y.; Guan, X.; Yang, Y.; Ye, X.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Paxlovid in Severe Adult Patients with SARS-Cov-2 Infection: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 33, 100694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukae, H.; Yotsuyanagi, H.; Ohmagari, N.; Doi, Y.; Sakaguchi, H.; Sonoyama, T.; Ichihashi, G.; Sanaki, T.; Baba, K.; Tsuge, Y.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ensitrelvir in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019: The Phase 2b Part of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2/3 Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yotsuyanagi, H.; Ohmagari, N.; Doi, Y.; Imamura, T.; Sonoyama, T.; Ichihashi, G.; Sanaki, T.; Tsuge, Y.; Uehara, T.; Mukae, H. A Phase 2/3 Study of S-217622 in Participants with SARS-CoV-2 Infection (Phase 3 Part). Medicine 2023, 102, e33024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, R.; Sonoyama, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Kuwata, A.; Matsuzaki, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Kubota, R. Evaluation of the Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid with Cytochrome P450 3A Substrates in Healthy Japanese Adults. Clin. Drug Investig. 2023, 43, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, Y.; Hibino, M.; Hase, R.; Yamamoto, M.; Kasamatsu, Y.; Hirose, M.; Mutoh, Y.; Homma, Y.; Terada, M.; Ogawa, T.; et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial of Early versus Late Favipiravir Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01897-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashchenko, A.A.; Dmitriev, K.A.; Vostokova, N.V.; Azarova, V.N.; Blinow, A.A.; Egorova, A.N.; Gordeev, I.G.; Ilin, A.P.; Karapetian, R.N.; Kravchenko, D.V.; et al. AVIFAVIR for Treatment of Patients with Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Interim Results of a Phase II/III Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udwadia, Z.F.; Singh, P.; Barkate, H.; Patil, S.; Rangwala, S.; Pendse, A.; Kadam, J.; Wu, W.; Caracta, C.F.; Tandon, M. Efficacy and Safety of Favipiravir, an Oral RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Inhibitor, in Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized, Comparative, Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase 3 Clinical Trial. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, F.; Al Naabi, H.; Al Lawati, A.; Ambusaidi, Z.; Al Sharji, M.; Al Barwani, U.; Pandak, N.; Al Balushi, Z.; Al Bahrani, M.; Al Salmi, I.; et al. Randomized Controlled Open Label Trial on the Use of Favipiravir Combined with Inhaled Interferon Beta-1b in Hospitalized Patients with Moderate to Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Liu, L.; Yao, H.; Hu, X.; Su, J.; Xu, K.; Luo, R.; Yang, X.; He, L.; Lu, X.; et al. Clinical Outcomes and Plasma Concentrations of Baloxavir Marboxil and Favipiravir in COVID-19 Patients: An Exploratory Randomized, Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 157, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holubar, M.; Subramanian, A.; Purington, N.; Hedlin, H.; Bunning, B.; Walter, K.S.; Bonilla, H.; Boumis, A.; Chen, M.; Clinton, K.; et al. Favipiravir for Treatment of Outpatients with Asymptomatic or Uncomplicated Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J.H.; Lau, J.S.Y.; Coldham, A.; Roney, J.; Hagenauer, M.; Price, S.; Bryant, M.; Garlick, J.; Paterson, A.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Favipiravir in Early Symptomatic COVID-19, a Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.L.; Orton, C.M.; Grinsztejn, B.; Donaldson, G.C.; Crabtree Ramírez, B.; Tonkin, J.; Santos, B.R.; Cardoso, S.W.; Ritchie, A.I.; Conway, F.; et al. Favipiravir in Patients Hospitalised with COVID-19 (PIONEER Trial): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Trial of Early Intervention versus Standard Care. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaezi, A.; Salmasi, M.; Soltaninejad, F.; Salahi, M.; Javanmard, S.H.; Amra, B. Favipiravir in the Treatment of Outpatient COVID-19: A Multicenter, Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Adv. Respir. Med. 2023, 91, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.D.; Lye, D.C.B.; Hui, D.S.; Marks, K.M.; Bruno, R.; Montejano, R.; Spinner, C.D.; Galli, M.; Ahn, M.-Y.; Nahass, R.G.; et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1827–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinner, C.D.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Criner, G.J.; Arribas López, J.R.; Cattelan, A.M.; Soriano Viladomiu, A.; Ogbuagu, O.; Malhotra, P.; Mullane, K.M.; Castagna, A.; et al. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients with Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Du, G.; Du, R.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, S.; Gao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, Q.; et al. Remdesivir in Adults with Severe COVID-19: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicentre Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2020, 395, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, A.; Nevola, R.; Sellitto, A.; Cozzolino, D.; Romano, C.; Cuomo, G.; Aprea, C.; Schwartzbaum, M.X.P.; Ricozzi, C.; Imbriani, S.; et al. Remdesivir Plus Dexamethasone Versus Dexamethasone Alone for the Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients Requiring Supplemental O2 Therapy: A Prospective Controlled Nonrandomized Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e403–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.H.; Fitzgerald, R.; Fletcher, T.; Ewings, S.; Jaki, T.; Lyon, R.; Downs, N.; Walker, L.; Tansley-Hancock, O.; Greenhalf, W.; et al. Optimal Dose and Safety of Molnupiravir in Patients with Early SARS-CoV-2: A Phase I, Open-Label, Dose-Escalating, Randomized Controlled Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3286–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Peng, L.; Shu, D.; Zhao, L.; Lan, J.; Tan, G.; Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C.; et al. Antiviral Efficacy and Safety of Molnupiravir Against Omicron Variant Infection: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 939573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, W.A.; Eron, J.J.; Holman, W.; Cohen, M.S.; Fang, L.; Szewczyk, L.J.; Sheahan, T.P.; Baric, R.; Mollan, K.R.; Wolfe, C.R.; et al. A Phase 2a Clinical Trial of Molnupiravir in Patients with COVID-19 Shows Accelerated SARS-CoV-2 RNA Clearance and Elimination of Infectious Virus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabl7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.G.; Puenpatom, A.; Moncada, P.A.; Burgess, L.; Duke, E.R.; Ohmagari, N.; Wolf, T.; Bassetti, M.; Bhagani, S.; Ghosn, J.; et al. Effect of Molnupiravir on Biomarkers, Respiratory Interventions, and Medical Services in COVID-19: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.H.; FitzGerald, R.; Saunders, G.; Middleton, C.; Ahmad, S.; Edwards, C.J.; Hadjiyiannakis, D.; Walker, L.; Lyon, R.; Shaw, V.; et al. Molnupiravir versus Placebo in Unvaccinated and Vaccinated Patients with Early SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the UK (AGILE CST-2): A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, C.C.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Gbinigie, O.A.; Rahman, N.M.; Hayward, G.; Richards, D.B.; Dorward, J.; Lowe, D.M.; Standing, J.F.; Breuer, J.; et al. Molnupiravir plus Usual Care versus Usual Care Alone as Early Treatment for Adults with COVID-19 at Increased Risk of Adverse Outcomes (PANORAMIC): An Open-Label, Platform-Adaptive Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2023, 401, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.G.; Strizki, J.M.; Brown, M.L.; Wan, H.; Shamsuddin, H.H.; Ramgopal, M.; Florescu, D.F.; Delobel, P.; Khaertynova, I.; Flores, J.F.; et al. Molnupiravir for the Treatment of COVID-19 in Immunocompromised Participants: Efficacy, Safety, and Virology Results from the Phase 3 Randomized, Placebo-Controlled MOVe-OUT Trial. Infection 2023, 51, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Luo, H.; Yu, Z.; Song, J.; Liang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. A Randomized, Open-Label, Controlled Clinical Trial of Azvudine Tablets in the Treatment of Mild and Common COVID-19, A Pilot Study. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden-Wurtt. Ger. 2020, 7, 2001435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jin, L.; Dian, Y.; Shen, M.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. Oral Azvudine for Hospitalised Patients with COVID-19 and Pre-Existing Conditions: A Retrospective Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, C.; Wu, Q.; Sun, H.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of Azvudine versus Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour Kasgari, H.; Moradi, S.; Shabani, A.M.; Babamahmoodi, F.; Davoudi Badabi, A.R.; Davoudi, L.; Alikhani, A.; Hedayatizadeh Omran, A.; Saeedi, M.; Merat, S.; et al. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Sofosbuvir plus Daclatasvir in Combination with Ribavirin for Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients with Moderate Disease Compared with Standard Care: A Single-Centre, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3373–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, G.; Mousaviasl, S.; Radmanesh, E.; Jelvay, S.; Bitaraf, S.; Simmons, B.; Wentzel, H.; Hill, A.; Sadeghi, A.; Freeman, J.; et al. The Impact of Sofosbuvir/Daclatasvir or Ribavirin in Patients with Severe COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3366–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Ali Asgari, A.; Norouzi, A.; Kheiri, Z.; Anushirvani, A.; Montazeri, M.; Hosamirudsai, H.; Afhami, S.; Akbarpour, E.; Aliannejad, R.; et al. Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir Compared with Standard of Care in the Treatment of Patients Admitted to Hospital with Moderate or Severe Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19): A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3379–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, H.; Nourian, A.; Ahmadinejad, Z.; Emadi Kouchak, H.; Jafari, S.; Dehghan Manshadi, S.A.; Rasolinejad, M.; Kebriaeezadeh, A. Efficacy and Safety of Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir in Treatment of Patients with COVID-19; A Randomized Clinical Trial. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, e2020102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozbeh, F.; Saeedi, M.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Hedayatizadeh-Omran, A.; Merat, S.; Wentzel, H.; Levi, J.; Hill, A.; Shamshirian, A. Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir for the Treatment of COVID-19 Outpatients: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobarak, S.; Salasi, M.; Hormati, A.; Khodadadi, J.; Ziaee, M.; Abedi, F.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Azarkar, Z.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F.; Joukar, F.; et al. Evaluation of the Effect of Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial (DISCOVER). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgohary, M.A.-S.; Hasan, E.M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Abdelsalam, M.F.A.; Abdel-Rahman, R.Z.; Zaki, A.I.; Elaatar, M.B.; Elnagar, M.T.; Emam, M.E.; Hamada, M.M.; et al. Efficacy of Sofosbuvir plus Ledipasvir in Egyptian Patients with COVID-19 Compared to Standard Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cully, M. A Tale of Two Antiviral Targets—And the COVID-19 Drugs That Bind Them. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 21, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicenti, I.; Zazzi, M.; Saladini, F. SARS-CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase as a Therapeutic Target for COVID-19. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijssers, A.J.; George, A.S.; Schäfer, A.; Leist, S.R.; Gralinksi, L.E.; Dinnon, K.H.; Yount, B.L.; Agostini, M.L.; Stevens, L.J.; Chappell, J.D.; et al. Remdesivir Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in Human Lung Cells and Chimeric SARS-CoV Expressing the SARS-CoV-2 RNA Polymerase in Mice. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Cao, R.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, W.; Xiao, G. Remdesivir and Chloroquine Effectively Inhibit the Recently Emerged Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Vitro. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Zhou, S.; Graham, R.L.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Agostini, M.L.; Leist, S.R.; Schäfer, A.; Dinnon, K.H.; Stevens, L.J.; et al. An Orally Bioavailable Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in Human Airway Epithelial Cell Cultures and Multiple Coronaviruses in Mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabb5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.; Selisko, B.; Le, N.-T.-T.; Huchting, J.; Touret, F.; Piorkowski, G.; Fattorini, V.; Ferron, F.; Decroly, E.; Meier, C.; et al. Rapid Incorporation of Favipiravir by the Fast and Permissive Viral RNA Polymerase Complex Results in SARS-CoV-2 Lethal Mutagenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Lo, M.K.; Ray, A.S.; Mackman, R.L.; Soloveva, V.; Siegel, D.; Perron, M.; Bannister, R.; Hui, H.C.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of the Small Molecule GS-5734 against Ebola Virus in Rhesus Monkeys. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Case, J.B.; Leist, S.R.; Pyrc, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Trantcheva, I.; et al. Broad-Spectrum Antiviral GS-5734 Inhibits Both Epidemic and Zoonotic Coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID-19. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-covid-19 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Martinez, D.R.; Moreira, F.R.; Zweigart, M.R.; Gully, K.L.; la Cruz, G.D.; Brown, A.J.; Adams, L.E.; Catanzaro, N.; Yount, B.; Baric, T.J.; et al. Efficacy of the Oral Nucleoside Prodrug GS-5245 (Obeldesivir) against SARS-CoV-2 and Coronaviruses with Pandemic Potential. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilead Sciences Gilead Sciences Statement on Phase 3 Obeldesivir Clinical Trials in COVID-19: BIRCH Study to Stop Enrollment While OAKTREE Study Nears Full Enrollment. Available online: https://www.gilead.com/news-and-press/company-statements/gilead-sciences-statement-on-phase-3-obeldesivir-clinical-trials-in-covid-19-birch-study-to-stop-enrollment-while-oaktree-study-nears-full-enrollment (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- European Medicines Agency Refusal of the Marketing Authorisation for Lagevrio (Molnupiravir). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop-initial/questions-answers-refusal-marketing-authorisation-lagevrio-molnupiravir_en.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Wang, R.-R.; Yang, Q.-H.; Luo, R.-H.; Peng, Y.-M.; Dai, S.-X.; Zhang, X.-J.; Chen, H.; Cui, X.-Q.; Liu, Y.-J.; Huang, J.-F.; et al. Azvudine, a Novel Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Showed Good Drug Combination Features and Better Inhibition on Drug-Resistant Strains than Lamivudine in Vitro. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, L.-L.; Liu, H.-Q.; Lu, S.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, B.; Li, S.-Y.; Shao, F.-M.; et al. Azvudine Is a Thymus-Homing Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Drug Effective in Treating COVID-19 Patients. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y. China Approves First Homegrown COVID Antiviral. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Chang, J. The First Chinese Oral Anti-COVID-19 Drug Azvudine Launched. Innov. Camb. Mass 2022, 3, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-C.; Lu, R.-M.; Su, S.-C.; Chiang, P.-Y.; Ko, S.-H.; Ke, F.-Y.; Liang, K.-H.; Hsieh, T.-Y.; Wu, H.-C. Monoclonal Antibodies for COVID-19 Therapy and SARS-CoV-2 Detection. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abani, O.; Abbas, A.; Abbas, F.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, S.; Abbass, H.; Abbott, A.; Abdallah, N.; Abdelaziz, A.; Abdelfattah, M.; et al. Casirivimab and Imdevimab in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Platform Trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gonzalez-Rojas, Y.; Juarez, E.; Crespo Casal, M.; Moya, J.; Falci, D.R.; Sarkis, E.; Solis, J.; Zheng, H.; Scott, N.; et al. Early Treatment for COVID-19 with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Sotrovimab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, A.D.; Issema, R.; Barnabas, R.V.; Ross, J.M. Estimated Health Outcomes and Costs of COVID-19 Prophylaxis with Monoclonal Antibodies Among Unvaccinated Household Contacts in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e228632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, R.; Basile, K.; Maddocks, S.; Fong, W.; Agius, J.E.; Johnson-Mackinnon, J.; Arnott, A.; Chandra, S.; Gall, M.; Draper, J.; et al. Resistance Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant after Sotrovimab Use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1477–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.P. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 and Host Cell Receptor Interactions. Antiviral Res. 2022, 210, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, Z.; Xie, X.; Hinton, P.R.; Liu, X.; Ye, X.; Muruato, A.E.; Ng, D.C.; Biswas, S.; Zou, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Nasal Delivery of an IgM Offers Broad Protection from SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Nature 2021, 595, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]