Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy

Abstract

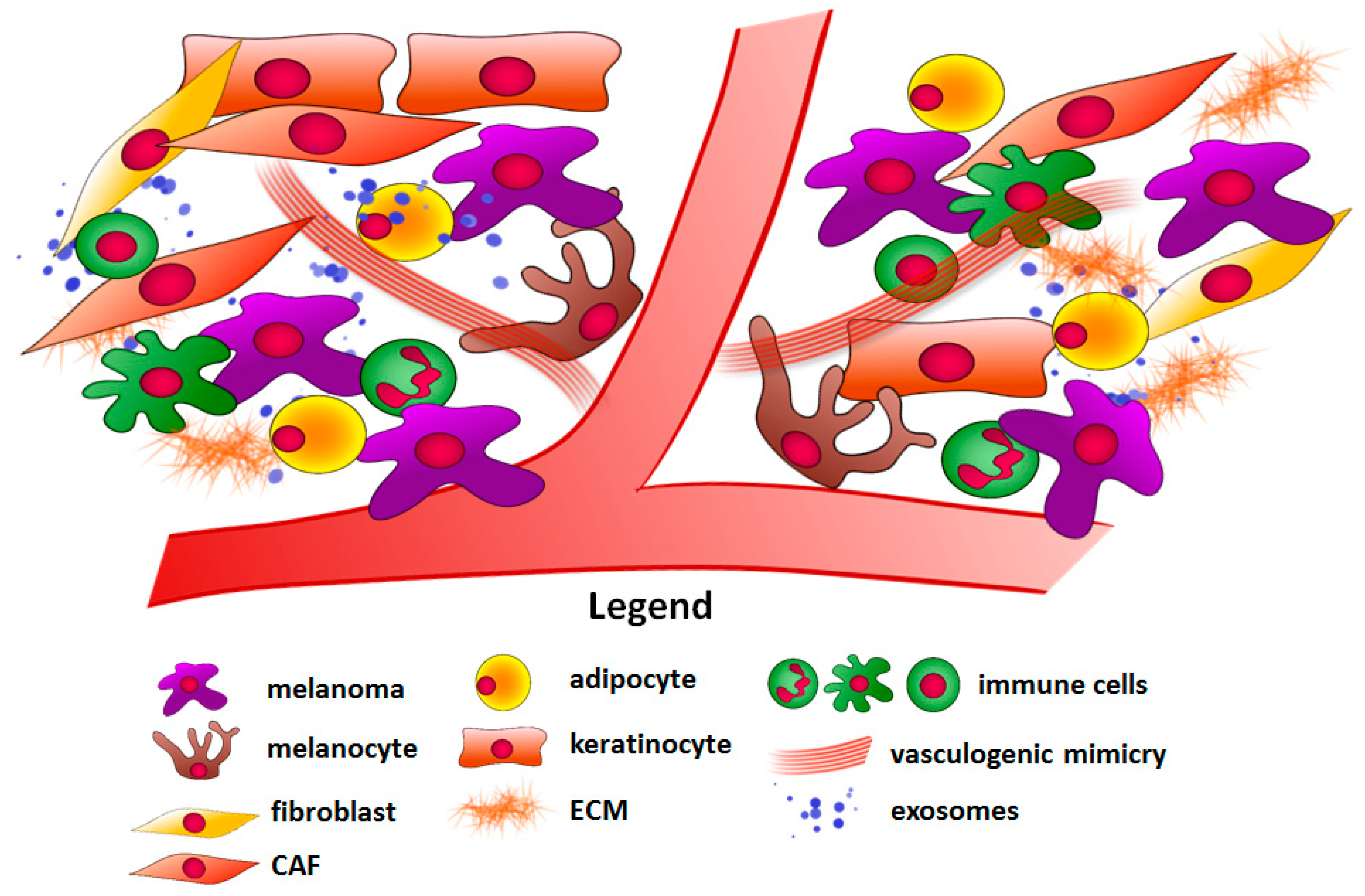

1. Introduction

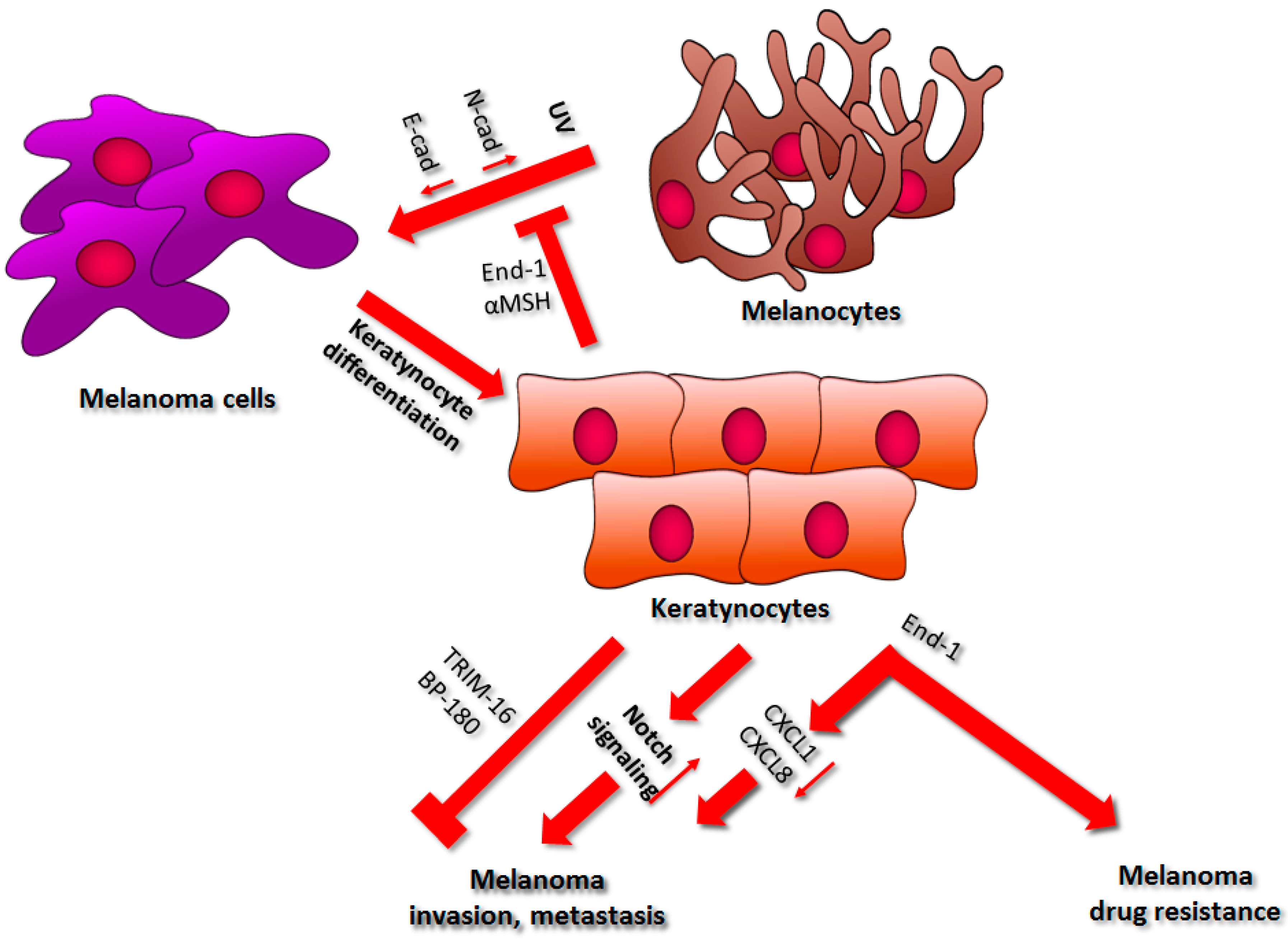

2. Keratinocytes

2.1. Regulation of Cell–Cell Interactions

2.2. Drug Resistance

2.3. Factors Secreted by Keratinocytes

3. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts

3.1. Cell Proliferation, Invasion, and Metastasis

3.2. Angiogenesis

3.3. Effect of CAFs on Melanoma Drug Resistance

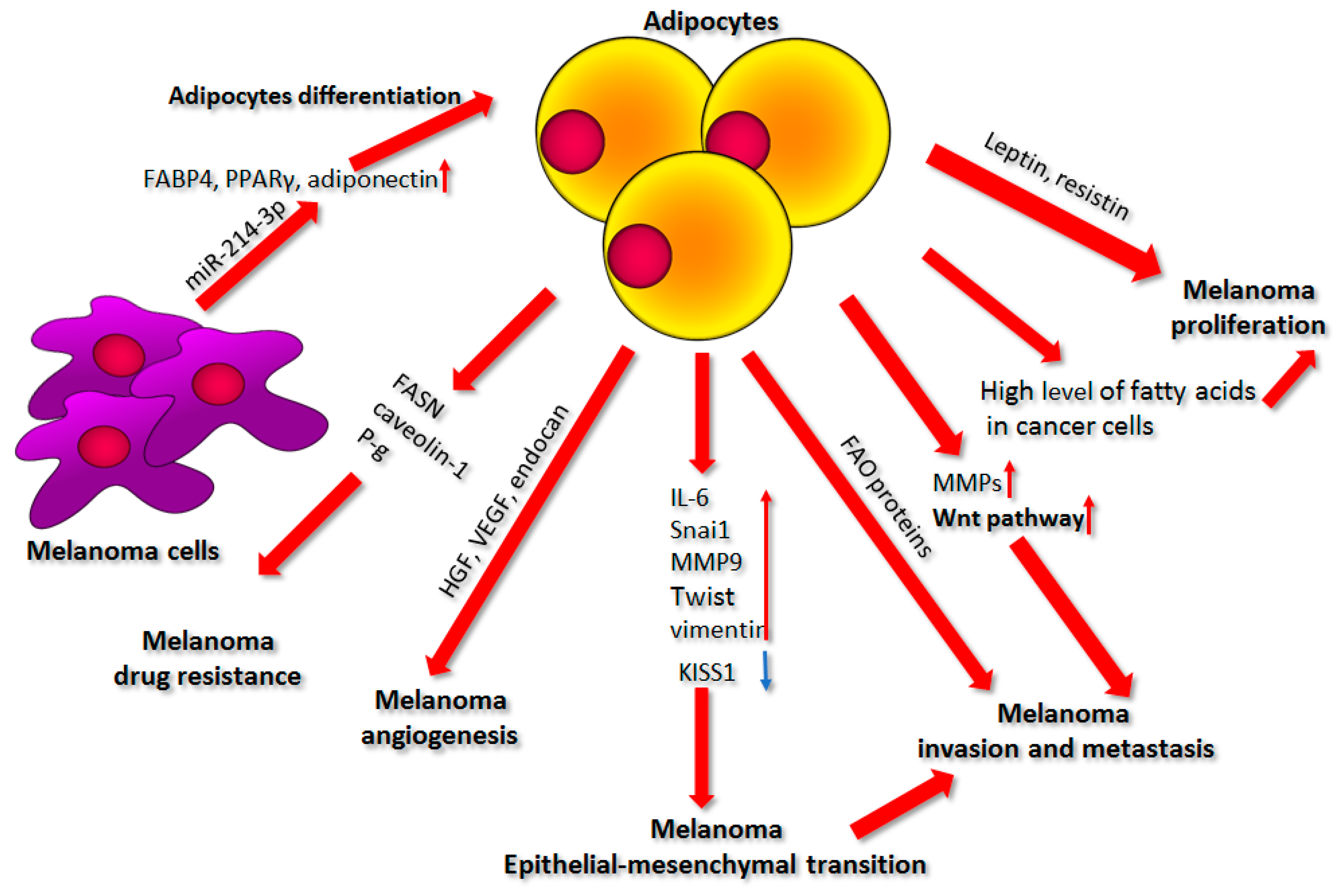

4. Adipocytes

4.1. Factors Secreted by Adipocytes

4.2. Source of Nutrients

4.3. Cell Invasion and Metastasis

4.4. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition

4.5. Adipocytes and Angiogenesis

4.6. Effect of Adipocytes on Drug Resistance

4.7. Influence of Melanoma on Adipocyte Differentiation

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, P.F.; Olsen, C.M.; Hayward, N.K.; Whiteman, D.C. Melanocortin 1 receptor and risk of cutaneous melanoma: A meta-analysis and estimates of population burden. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, L.E.; Shalin, S.C.; Tackett, A.J. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebecca, V.W.; Sondak, V.K.; Smalley, K.S.M. A brief history of melanoma: From mummies to mutations. Melanoma Res. 2012, 22, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreck, K.C.; Grossman, S.A.; Pratilas, C.A. BRAF mutations and the utility of RAF and MEK inhibitors in primary brain tumors. Cancers 2019, 11, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luebker, S.A.; Koepsell, S.A. Diverse Mechanisms of BRAF Inhibitor Resistance in Melanoma Identified in Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Cohen, M.S. The discovery of vemurafenib for the treatment of BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiter, D.; Bogenrieder, T.; Elder, D.; Herlyn, M. Melanoma—Stroma interactions: Structural and functional aspects. Lancet Oncol. 2002, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzu, S.; Beleaua, M.A.; Jung, I. The role of tumor microenvironment in development and progression of malignant melanomas-a systematic review. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sriraman, S.K.; Aryasomayajula, B.; Torchilin, V.P. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Tissue Barriers 2014, 2, e29528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrousse, A.-L.; Ntayi, C.; Hornebeck, W.; Bernard, P. Stromal reaction in cutaneous melanoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2004, 49, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, K.; Hara, M.; Nagasaki, T.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, H.; Takeyama, H. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Their Characteristics and Their Roles in Tumor Growth. Cancers 2015, 7, 2443–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Allen, C.L.; Maguire, O.; Minderman, H.; Sen, A.; Ciesielski, M.J.; Collins, K.A.; Bush, P.J.; Singh, P.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming of stromal fibroblasts by melanoma exosome microRNA favours a pre- metastatic microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simiczyjew, A.; Dratkiewicz, E.; Mazurkiewicz, J.; Ziętek, M.; Matkowski, R.; Nowak, D. The Influence of Tumor Microenvironment on Immune Escape of Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, J.; Herlyn, M. Melanoma and the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Fukunaga-Kalabis, M.; Herlyn, M. Crosstalk in skin: Melanocytes, keratinocytes, stem cells, and melanoma. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 10, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, V.B.; Starner, R.J.; Rauck, C.; Abdel-Malek, Z.A. Endothelin-1 and α-melanocortin have redundant effects on global genome repair in UV-irradiated human melanocytes despite distinct signaling pathways. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2020, 33, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadekaro, A.L.; Kavanagh, R.; Kanto, H.; Terzieva, S.; Hauser, J.; Kobayashi, N.; Schwemberger, S.; Cornelius, J.; Babcock, G.; Shertzer, H.G.; et al. A-Melanocortin and Endothelin-1 Activate Antiapoptotic Pathways and Reduce DNA Damage in Human Melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4292–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.; Lema, C.; Kirken, R.; Maldonado, R.A.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Aguilera, R.J. Arsenic-exposed Keratinocytes Exhibit Differential microRNAs Expression Profile; Potential Implication of miR-21, miR-200a and miR-141 in Melanoma Pathway. Clin. Cancer Drugs 2015, 2, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, B.C.; John, S.M.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Schmitz, G. MicroRNA-21-enriched exosomes as epigenetic regulators in melanomagenesis and melanoma progression: The impact of western lifestyle factors. Cancers 2020, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Fukatani, K.; Nakashima, A.; Suzuki, K. MicroRNA-141-3p and microRNA-200a-3p regulate α-melanocyte stimulating hormone-stimulated melanogenesis by directly targeting microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Di, W.; Hua, L.; Zhou, B.; Guo, Z.; Luo, D. UVB suppresses PTEN expression by upregulating miR-141 in HaCaT cells. J. Biomed. Res. 2011, 25, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodet, O.; Lacina, L.; Krejčí, E.; Dvořánková, B.; Grim, M.; Štork, J.; Kodetová, D.; Vlček, Č.; Šáchová, J.; Kolář, M.; et al. Melanoma cells influence the differentiation pattern of human epidermal keratinocytes. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuphal, S.; Bosserhoff, A.K. E-cadherin cell-cell communication in melanogenesis and during development of malignant melanoma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 524, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliano, R.L. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: Functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002, 42, 283–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.Y.; Meier, F.; Herlyn, M. Melanoma development and progression: A conspiracy between tumor and host. Differentiation 2002, 70, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuphal, S.; Poser, I.; Jobin, C.; Hellerbrand, C.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Loss of E-cadherin leads to upregulation of NFκB activity in malignant melanoma. Oncogene 2004, 23, 8509–8519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.; Andl, T.; Li, G.; Meinkoth, J.; Herlyn, M. Cadherin repertoire determines partner-specific gap junctional communication during melanoma progression. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Koefinger, P.; Wels, C.; Joshi, S.; Damm, S.; Steinbauer, E.; Beham-Schmid, C.; Frank, S.; Bergler, H.; Schaider, H. The cadherin switch in melanoma instigated by HGF is mediated through epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulators. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Wheelock, M.; Johnson, K.; Herlyn, M. Shifts in cadherin profiles between human normal melanocytes and melanomas. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 1996, 1, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Herlyn, M. N-cadherin-mediated intercellular interactions promote survival and migration of melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 3819–3825. [Google Scholar]

- Satyamoorthy, K.; Muyrers, J.; Meier, F.; Patel, D.; Herlyn, M. Mel-CAM-specific genetic suppressor elements inhibit melanoma growth and invasion through loss of gap junctional communication. Oncogene 2001, 20, 4676–4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.Y.; Meier, F.E.; Nesbit, M.; Hsu, J.Y.; Van Belle, P.; Elder, D.E.; Herlyn, M. E-cadherin expression in melanoma cells restores keratinocyte-mediated growth control and down-regulates expression of invasion-related adhesion receptors. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlyn, M.; Rodeck, U.; Mancianti, M.; Cardillo, F.M.; Lang, A.; Ross, A.H.; Jambrosic, J.; Koprowski, H. Expression of Melanoma-associated Antigens in Rapidly Dividing Human Melanocytes in Culture. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 3057–3061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shih, L.M.; Elder, D.E.; Hsu, M.Y.; Herlyn, M. Regulation of Mel-CAM/MUC18 expression on melanocytes of different stages of tumor progression by normal keratinocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 1994, 145, 837–845. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, R. Endothelin receptor B is required for the expansion of melanocyte precursors and malignant melanoma. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005, 49, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S. Endothelin-1 down-regulates E-cadherin in melanocytic cells by apoptosis-independent activation of caspase-8. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 43, 703–704. [Google Scholar]

- Mangahas, C.R.; Dela Cruz, G.V.; Friedman-Jiménez, G.; Jamal, S. Endothelin-1 induces CXCL1 and CXCL8 secretion in human melanoma cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balentien, E.; Mufson, B.E.; Shattuck, R.L.; Derynck, R.; Richmond, A. Effects of MGSA/GROα on melanocyte transformation. Oncogene 1991, 6, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Gutman, M.; Radinsky, R.; Bucana, C.D.; Fidler, I.J. Expression of Interleukin 8 Correlates with the Metastatic Potential of Human Melanoma Cells in Nude Mice. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3242–3247. [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga, L.; Meehan, S.; Osman, I.; Glick, M.; De La Cruz, G.; Howell, B.S.; Friedman-Jiménez, G.; Schneider, R.J.; Jamal, S. Endothelin-1 in the tumor microenvironment correlates with melanoma invasion. Melanoma Res. 2016, 26, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbet, A.; Costa, N.; Leventoux, N.; Mabondzo, A.; Couraud, J.Y.; Borrull, A.; Hugnot, J.P.; Boquet, D. Antibodies targeting human endothelin-1 receptors reveal different conformational states in cancer cells. Physiol. Res. 2018, 67, S257–S264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; Dong, C.; Fan, R.; Qi, S. A high affinity nanobody against endothelin receptor type B: A new approach to the treatment of melanoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirosh, I.; Izar, B.; Prakadan, S.M.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Treacy, D.; Trombetta, J.J.; Rotem, A.; Rodman, C.; Lian, C.; Murphy, G.; et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 2016, 352, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Krijgsman, O.; Tsoi, J.; Robert, L.; Hugo, W.; Song, C.; Kong, X.; Possik, P.A.; Cornelissen-Steijger, P.D.M.; Geukes Foppen, M.H.; et al. Low MITF/AXL ratio predicts early resistance to multiple targeted drugs in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.P.; Rowling, E.J.; Miskolczi, Z.; Ferguson, J.; Spoerri, L.; Haass, N.K.; Sloss, O.; McEntegart, S.; Arozarena, I.; Kriegsheim, A.; et al. Targeting endothelin receptor signalling overcomes heterogeneity driven therapy failure. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.K.; Cheung, B.B.; Massudi, H.; Tan, O.; Koach, J.; Mayoh, C.; Carter, D.R.; Marshall, G.M. Heterozygous loss of keratinocyte TRIM16 expression increases melanocytic cell lesions and lymph node metastasis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, S.K.; Koach, J.; Tan, O.; Liu, B.; Carter, D.R.; Wilmott, J.S.; Yosufi, B.; Haydu, L.E.; Mann, G.J.; Thompson, J.F.; et al. TRIM16 inhibits proliferation and migration through regulation of interferon beta 1 in melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 10127–10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hwang, B.J.; Zhang, Y.; Brozowski, J.M.; Liu, Z.; Burette, S.; Lough, K.; Smith, C.C.; Shan, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, N.; et al. The dysfunction of BP180/collagen XVII in keratinocytes promotes melanoma progression. Oncogene 2019, 38, 7491–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenacs, T.; Kiszner, G.; Stelkovics, E.; Balla, P.; Teleki, I.; Nemeth, I.; Varga, E.; Korom, I.; Barbai, T.; Plotar, V.; et al. Collagen XVII is expressed in malignant but not in benign melanocytic tumors and it can mediate antibody induced melanoma apoptosis. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 138, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlyn, M.; Clark, W.H.; Rodeck, U. Biology of disease. Biology of tumor progression in human melanocytes. Lab. Investig. 1987, 56, 461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, T.; Messer, A.R.; Amitai-Lange, A.; Melamed, Z.; Ohana, R.; Bell, R.E.; Kapitansky, O.; Lerman, G.; Greenberger, S.; Khaled, M.; et al. Interactions of Melanoma Cells with Distal Keratinocytes Trigger Metastasis via Notch Signaling Inhibition of MITF. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felicetti, F.; De Feo, A.; Coscia, C.; Puglisi, R.; Pedini, F.; Pasquini, L.; Bellenghi, M.; Errico, M.C.; Pagani, E.; Carè, A. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-222 is sufficient to increase tumor malignancy in melanoma. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, Y. HMGA1 exacerbates tumor progression by activating miR-222 through PI3K/Akt/MMP-9 signaling pathway in uveal melanoma. Cell. Signal. 2019, 63, 109386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashima, A.; Bergstresser, P.R. Impact of UVB Radiation on the Epidermal Cytokine Network. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 63, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellman, Y.G.; Makela, M.; Norris, D.A. Induction of secreted matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in human melanoma cells by extracellular matrix proteins and cytokines. Melanoma Res. 2006, 16, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascard, P.; Tlsty, T.D. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts: Orchestrating the composition of malignancy. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Vickers, M.F.; Kerbel, R.S. Interleukin 6: A fibroblast-derived growth inhibitor of human melanoma cells from early but not advanced stages of tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 9215–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhou, L.; Yang, K.; Iwasawa, K.; Kadekaro, A.L. The β -catenin / YAP signaling axis is a key regulator of melanoma-associated fi broblasts. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, K.; Andl, T.; Wickett, R.R.; Zhang, Y. Perspective of Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Melanoma. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yan, T.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, E.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Shao, Z.; et al. Melanoma cell-secreted exosomal miR-155-5p induce proangiogenic switch of cancer-associated fibroblasts via SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, A.; Keilholz, U. Role of TGF-β in Melanoma. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, A.; Weinberg, R.A. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer: A novel tumor-promoting cell type. Cell Cycle. 2006, 5, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, H.; Mundel, T.M.; Kieran, M.W.; Kalluri, R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, W.W.; Wen, Q.T.; Xu, L.; Chen, M. TGF-β-induced fibroblast activation protein expression, fibroblast activation protein expression increases the proliferation, adhesion, and migration of HO-8910PM. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009, 87, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmik, M.; Ullmann, P.; Rodriguez, F.; Haan, S.; Letellier, E. In search of definitions: Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their markers. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wan, G.; Cai, S.; Du, J. Nodal Facilitates Differentiation of Fibroblasts to Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts that Support Tumor Growth in Melanoma and Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2019, 8, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuninty, P.R.; Bojmar, L.; Tjomsland, V.; Larsson, M.; Storm, G.; Östman, A.; Sandström, P.; Prakash, J. MicroRNA-199a and -214 as potential therapeutic targets in pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic tumor. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 16396–16408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunavat, T.R.; Cheng, L.; Kim, D.K.; Bhadury, J.; Jang, S.C.; Lässer, C.; Sharples, R.A.; López, M.D.; Nilsson, J.; Gho, Y.S.; et al. Small RNA deep sequencing discriminates subsets of extracellular vesicles released by melanoma cells—Evidence of unique microRNA cargos. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, M.; Anene, C.A.; Nsengimana, J.; Roberts, W.; Newton-Bishop, J.; Boyne, J.R. The role of CAF derived exosomal microRNAs in the tumour microenvironment of melanoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, S.; Sander, L.; Schwartz, H.; Sheinboim, D.; Barzilai, A.; Dishon, Y.; Apcher, S.; Golan, T.; Greenberger, S.; Barshack, I.; et al. Melanoma miRNA trafficking controls tumour primary niche formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunavat, T.R.; Cheng, L.; Einarsdottir, B.O.; Bagge, R.O.; Muralidharan, S.V.; Sharples, R.A.; Lässer, C.; Gho, Y.S.; Hill, A.F.; Nilsson, J.A.; et al. BRAFV600 inhibition alters the microRNA cargo in the vesicular secretome of malignant melanoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5930–E5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, K.; Wickett, R.R.; Kadekaro, A.L. Targeted deactivation of cancer-associated fibroblasts by β -catenin ablation suppresses melanoma growth. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 14235–14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, K.; Dunaway, S.; Abdel-Malek, Z.; Andl, T.; Kadekaro, A.L.; Zhang, Y. Suppression of MAPK signaling in BRAF-activated PTEN-deficient melanoma by blocking β-catenin signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018, 31, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Webster, M.R.; Marchbank, K.; Behera, R.; Ndoye, A.; Kugel, C.H.; Dang, V.M.; Appleton, J.; O’Connell, M.P.; Cheng, P.; et al. sFRP2 in the aged microenvironment drives melanoma metastasis and therapy resistance. Nature 2016, 532, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchenreuther, J.; Vincent, K.; Norley, C.; Racanelli, M. Activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts is required for tumor neovascularization in a murine model of melanoma. Matrix Biol. 2018, 74, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Son, S.; Shin, I. Role of the CCN protein family in cancer. BMB Rep. 2018, 51, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, K.; Williams, S.; Kothapalli, D.; Klapper, H.; Grotendorst, G.R. Stimulation of fibroblast cell growth, matrix production, and granulation tissue formation by connective tissue growth factor. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1996, 107, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazani, Y.; Knops, N.; Elmonem, M.A.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Arcolino, F.O.; van den Heuvel, L.; Levtchenko, E.; Kuypers, D.; Goldschmeding, R. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) from basics to clinics. Matrix Biol. 2018, 68–69, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, I.; Shiomi, T.; Hashimoto, G.; Enomoto, H.; Nakamura, H.; Makino, K.; Ikeda, E.; Takata, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Okada, Y. Connective tissue growth factor binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Leask, A. CCN2 expression and localization in melanoma cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011, 5, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchenreuther, J.; Vincent, K.M.; Carter, D.E.; Postovit, L.; Leask, A. CCN2 Expression by Tumor Stroma Is Required for Melanoma Metastasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2805–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, A.; Azuma, S.; Tanaka, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Takaki, S.; Takatsu, K.; Nakao, K.; Nakamura, K.; Katsuki, M.; Yamamoto, T.; et al. Severe osteopetrosis, defective interleukin-1 signalling and lymph node organogenesis in TRAF6-deficient mice. Genes Cells 1999, 4, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomaga, M.A.; Yeh, W.C.; Sarosi, I.; Duncan, G.S.; Furlonger, C.; Ho, A.; Morony, S.; Capparelli, C.; Van, G.; Kaufman, S.; et al. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, W.; Su, J.; Yang, K.; Lu, L.; Bian, C. TRAF6 regulates melanoma invasion and metastasis through ubiquitination of Basigin. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.L.; Wang, J.; Chan, C.H.; Lee, S.W.; Campos, A.D.; Lamothe, B.; Hur, L.; Grabiner, B.C.; Lin, X.; Darnay, B.G.; et al. The E3 Ligase TRAF6 regulates akt ubiquitination and activation. Science 2009, 325, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Ghosh, S.; Bagchi, A. A structural perspective on the interactions of TRAF6 and Basigin during the onset of melanoma: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Mol. Recognit. 2017, 30, e2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F. Targeting AKT for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2019, 28, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, J.; Cai, L.; Wu, Z.; Su, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, N.; Tang, L.; et al. TRAF6 Activates Fibroblasts to Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) through FGF19 in Tumor Microenvironment to Benefit the Malignant Phenotype of Melanoma Cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 2268–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meierjohann, S.; Hufnagel, A.; Wende, E.; Kleinschmidt, M.A.; Wolf, K.; Friedl, P.; Gaubatz, S.; Schartl, M. MMP13 mediates cell cycle progression in melanocytes and melanoma cells: In vitro studies of migration and proliferation. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandel, E.; Grasshoff, A.; Mittag, M.; Haustein, U.F.; Saalbach, A. Fibroblasts surrounding melanoma express elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in vitro. Exp. Dermatol. 2000, 9, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntayi, C.; Hornebeck, W.; Bernard, P.; Ntayi, C.; Hornebeck, W.; Bernard, P. Influence of cultured dermal fibroblasts on human melanoma cell proliferation, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) expression and invasion in vitro. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2003, 1, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Tang, X.; Wong, P.; Jacobs, B.; Borden, E.C.; Bedogni, B. Noncanonical Activation of Notch1 Protein by Membrane Type 1 Matrix Metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) Controls Melanoma Cell Proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 8442–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittayapruek, P.; Meephansan, J.; Prapapan, O.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in Photoaging and photocarcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ren, X. Fibroblast activation protein: A potential therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wäster, P.; Orfanidis, K.; Eriksson, I.; Rosdahl, I.; Seifert, O.; Öllinger, K. UV radiation promotes melanoma dissemination mediated by the sequential reaction axis of cathepsins-TGF-β1-FAP-α. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraman, M.; Bambrough, P.J.; Arnold, J.N.; Roberts, E.W.; Magiera, L.; Jones, J.O.; Gopinathan, A.; Tuveson, D.A.; Fearon, D.T. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-α. Science 2010, 330, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, V.; Arkhypov, I.; Weber, R.; Groth, C.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Modern Aspects of Immunotherapy with Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Maki, W.; Cardones, A.R.; Fang, H.; Kyi, A.T.; Nestle, F.O.; Hwang, S.T. Expression of CXC Chemokine Receptor-4 Enhances the Pulmonary Metastatic Potential of Murine B16 Melanoma Cells 1. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 7328–7334. [Google Scholar]

- Cardones, A.R.; Murakami, T.; Hwang, S.T. CXCR4 Enhances Adhesion of B16 Tumor Cells to Endothelial Cells in Vitro and in Vivo via β1 Integrin. Cancer Res. 2003, 54, 3233–3236. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, A.T.; Ellis, R.; Pathy, B.; Plummer, R.; Lovat, P.E.; O’Boyle, G. The prognostic significance and impact of the CXCR4–CXCR7–CXCL12 axis in primary cutaneous melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieranò, C.; D’Alterio, C.; Giarra, S.; Napolitano, M.; Rea, G.; Portella, L.; Santagata, A.; Trotta, A.M.; Barbieri, A.; Campani, V.; et al. CXCL12 loaded-dermal filler captures CXCR4 expressing melanoma circulating tumor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massagué, J. TGFβ in Cancer. Cell 2008, 134, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straussman, R.; Morikawa, T.; Shee, K.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Qian, Z.R.; Du, J.; Davis, A.; Mongare, M.M.; Gould, J.; Frederick, D.T.; et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature 2012, 487, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazao-Rozas, P.; Guerreschi, P.; Jendoubi, M.; André, F.; Jonneaux, A.; Scalbert, C.; Garçon, G.; Malet-Martino, M.; Balayssac, S.; Rocchi, S.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress is the Achille’s heel of melanoma cells resistant to Braf-mutant inhibitor. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 1986–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Gao, L.X.; Ma, X.Q.; Hu, F.X.; Li, C.M.; Lu, Z. Involvement of superoxide and nitric oxide in BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032-induced growth inhibition of melanoma cells. Integr. Biol. 2014, 6, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, M.P.; Marchbank, K.; Webster, M.R.; Valiga, A.A.; Kaur, A.; Vultur, A.; Li, L.; Herlyn, M.; Villanueva, J.; Liu, Q.; et al. Hypoxia induces phenotypic plasticity and therapy resistance in melanoma via the tyrosine kinase receptors ROR1 and ROR2. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 1378–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biechele, T.L.; Kulikauskas, R.M.; Toroni, R.A.; Lucero, O.M.; Swift, R.D.; James, R.G.; Robin, N.C.; Dawson, D.W.; Moon, R.T.; Chien, A.J. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and AXIN1 regulate apoptosis triggered by inhibition of the mutant kinase BRAF V600E in human melanoma. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczkowski, D.J.; Johannessen, C.M.; Abudayyeh, O.; Kim, J.W.; Cooper, Z.A.; Piris, A.; Frederick, D.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Straussman, R.; Haq, R.; et al. A melanoma cell state distinction influences sensitivity to MAPK pathway inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.V.; Basile, K.J.; Kugel, C.H.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Le, K.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Karakousis, G.C.; Xu, X.; Xu, W.; Schuchter, L.M.; et al. Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falls, D.L. Neuregulins: Functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 284, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledonne, A.; Mercuri, N.B. On the modulatory roles of neuregulins/ErbB signaling on synaptic plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capparelli, C.; Rosenbaum, S.; Berger, A.C.; Aplin, A.E. Fibroblast-derived Neuregulin 1 Promotes Compensatory ErbB3 Receptor Signaling in Mutant BRAF Melanoma. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 24267–24277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugel, C.H., III; Hartsough, E.J.; Davies, M.A.; Setiady, Y.Y.; Aplin, A.E. Function-blocking ERBB3 antibody inhibits the adaptive response to RAF inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Cancer-associated fi broblasts promote PD-L1 expression in mice. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 12, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadzadeh, M.; Johnson, L.A.; Heemskerk, B.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Dudley, M.E.; White, D.E.; Rosenberg, S.A. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood 2009, 114, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, E.; Lazar, I.; Muller, C.; Nieto, L. Obesity and melanoma: Could fat be fueling malignancy? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017, 30, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, K.M.; Romero, I.L.; Van Houten, B.; Lengyel, E. Adipose tissue and adipocytes support tumorigenesis and metastasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2013, 1831, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpa, J. Tumor Microenvironment; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 9780470749968. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, F.; Soares, R. Obesity and cancer phenotype: Is angiogenesis a missed link? Life Sci. 2015, 139, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.M.; Tampa, M.; Mitran, C.I.; Mitran, M.I.; Caruntu, C.; Caruntu, A.; Lupu, M.; Matei, C.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M. Tumor Microenvironments in Organs, Tumour Microenvironment in Skin Carcinogenesis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9783030362133. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, P.; Almeida, J.; Prudêncio, C.; Fernandes, R.; Soares, R. Effect of Adipocyte Secretome in Melanoma Progression and Vasculogenic Mimicry. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Magnuson, A.; Fouts, J.; Foster, M. Adipose tissue, obesity and adipokines: Role in cancer promotion. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 21, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvi, P.; Chaube, B.; Pandey, V.; Vijayakumar, M.V.; Boreddy, P.R.; Mohammad, N.; Singh, S.V.; Bhat, M.K. Obesity induced rapid melanoma progression is reversed by orlistat treatment and dietary intervention: Role of adipokines. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalding, K.L.; Arner, E.; Westermark, P.O.; Bernard, S.; Buchholz, B.A.; Bergmann, O.; Blomqvist, L.; Hoffstedt, J.; Näslund, E.; Britton, T.; et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature 2008, 453, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Antoniadis, A.G.; Gogas, H.J.; Antonopoulos, C.N.; Adami, H.O.; Ekbom, A.; Petridou, E.T. Obesity and risk of malignant melanoma: A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.K.; Arabi, S.; Lelliott, E.J.; McArthur, G.A.; Sheppard, K.E. Obesity and the impact on cutaneous melanoma: Friend or foe? Cancers 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, E.L.; Gu, J.W.; Cantwell, L.; He, Z.; Wallace, G.; Hall, J.E. Obesity promotes melanoma tumor growth: Role of leptin. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009, 8, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Vijayakumar, M.V.; Ajay, A.K.; Malvi, P.; Bhat, M.K. Diet-induced obesity increases melanoma progression: Involvement of Cav-1 and FASN. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.I.; Cho, H.J.; Jung, Y.J.; Kwon, S.H.; Her, S.; Choi, S.S.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, K.W.; Park, J.H.Y. High-fat diet-induced obesity increases lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis in the B16F10 melanoma allograft model: Roles of adipocytes and M2-macrophages. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vizio, D.; Adam, R.M.; Kim, J.; Kim, R.; Sotgia, F.; Williams, T.; Demichelis, F.; Solomon, K.R.; Loda, M.; Rubin, M.A.; et al. Caveolin-1 interacts with a lipid raft-associated population of fatty acid synthase. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 2257–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.S.; Sharma, A.; Kumari, R.; Mohammad, N.; Singh, S.V.; Bhat, M.K. Inherent and Acquired Resistance to Paclitaxel in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Molecular Events Involved. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadi, F.; Javanmard, S.H.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, H.; Khazaei, M.; Narimani, M. Leptin promotes melanoma tumor growth in mice related to increasing circulating endothelial progenitor cells numbers and plasma NO production. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Diwan, A.H.; Dang, S.M.; Uffort, D.G.; Johnson, M.K.; Cooke, C.P.; Grimm, E.A. Promotion of melanoma growth by the metabolic hormone leptin. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 23, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katira, A.; Tan, P.H. Evolving role of adiponectin in cancer-controversies and update. Cancer Biol. Med. 2016, 13, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Roh-Johnson, M. Sharing Is Caring. Dev. Cell 2019, 49, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Coelho, F.; Gouveia-Fernandes, S.; Serpa, J. Metabolic cooperation between cancer and non-cancerous stromal cells is pivotal in cancer progression. Tumor Biol. 2018, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabacka, M.; Plonka, P.M.; Reiss, K. Melanoma—Time to fast or time to feast? An interplay between PPARs, metabolism and immunity. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoico, E.; Darra, E.; Rizzatti, V.; Tebon, M.; Franceschetti, G.; Mazzali, G.; Rossi, A.P.; Fantin, F.; Zamboni, M. Role of adipose tissue in melanoma cancer microenvironment and progression. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, H.Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, B.; Chao, X.; Chan, C.L.; Cao, H.; Su, T.; Tse, A.K.W.; Fong, W.F.; Yu, Z.-L. Subcutaneous adipocytes promote melanoma cell growth by activating the Akt signaling pathway: Role of palmitic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 30525–30537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Di Martino, J.S.; Bowman, R.L.; Campbell, N.R.; Baksh, S.C.; Simon-Vermot, T.; Kim, I.S.; Haldeman, P.; Mondal, C.; Yong-Gonzales, V.; et al. Adipocyte-derived lipids mediate melanoma progression via FATP proteins. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.H.; Um, J.Y.; Lee, S.G.; Yang, W.M.; Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S. Conditioned media from adipocytes promote proliferation, migration, and invasion in melanoma and colorectal cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 18249–18261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavey, C.; Mari, B.; Monthouel, M.N.; Bonnafous, S.; Anglard, P.; Van Obberghen, E.; Tartare-Deckert, S. Matrix metalloproteinases are differentially expressed in adipose tissue during obesity and modulate adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11888–11896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, T.; Parikh, R.; Jacob, E.; Vaknine, H.; Zemser-Werner, V.; Hershkovitz, D.; Malcov, H.; Leibou, S.; Reichman, H.; Sheinboim, D.; et al. Adipocytes sensitize melanoma cells to environmental TGF-β cues by repressing the expression of miR-211. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12, eaav6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, N.; Song, L.; Xie, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, C.; Xu, G. Adipokines and free fatty acids regulate insulin sensitivity by increasing microRNA-21 expression in human mature adipocytes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 2254–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- An, Y.; Zhao, J.; Nie, F.; Qin, Z.; Xue, H.; Wang, G.; Li, D. Exosomes from Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) Overexpressing miR-21 Promote Vascularization of Endothelial Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au Yeung, C.L.; Co, N.N.; Tsuruga, T.; Yeung, T.L.; Kwan, S.Y.; Leung, C.S.; Li, Y.; Lu, E.S.; Kwan, K.; Wong, K.K.; et al. Exosomal transfer of stroma-derived miR21 confers paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells through targeting APAF1. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robado de Lope, L.; Alcíbar, O.L.; Amor López, A.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Peinado, H. Tumour-adipose tissue crosstalk: Fuelling tumour metastasis by extracellular vesicles. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20160485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.L.; Luo, Y.; Eriksson, D.; Meng, X.; Qian, C.; Bäuerle, T.; Chen, X.X.; Schett, G.; Bozec, A. High fat diet increases melanoma cell growth in the bone marrow by inducing osteopontin and interleukin 6. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 26653–26669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Mao, X.; Mehta, M.; Cui, J.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y. A comparative study of gene-expression data of basal cell carcinoma and melanoma reveals new insights about the two cancers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, I.; Clement, E.; Dauvillier, S.; Milhas, D.; Ducoux-Petit, M.; LeGonidec, S.; Moro, C.; Soldan, V.; Dalle, S.; Balor, S.; et al. Adipocyte Exosomes Promote Melanoma Aggressiveness through Fatty Acid Oxidation: A Novel Mechanism Linking Obesity and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4051–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D. Adipose tissue: Adipocyte exosomes drive melanoma progression. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 436. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, E.; Lazar, I.; Attané, C.; Carrié, L.; Dauvillier, S.; Ducoux-Petit, M.; Esteve, D.; Menneteau, T.; Moutahir, M.; Le Gonidec, S.; et al. Adipocyte extracellular vesicles carry enzymes and fatty acids that stimulate mitochondrial metabolism and remodeling in tumor cells. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastushenko, I.; Blanpain, C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffer, C.L.; Weinberg, R.A. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 2011, 331, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, L.J.; Vaidya, K.S.; Welch, D.R. Metastasis suppressors genes in cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 874–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushiro, K.; Chu, R.A.; Verma, A.; Núñez, N.P. Adipocytes promote B16BL6 melanoma cell invasion and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Microenviron. 2012, 5, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenouille, N.; Tichet, M.; Dufies, M.; Pottier, A.; Mogha, A.; Soo, J.K.; Rocchi, S.; Mallavialle, A.; Galibert, M.D.; Khammari, A.; et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulatory factor SLUG (SNAI2) is a downstream target of SPARC and AKT in promoting melanoma cell invasion. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimbow, K.; Lee, S.K.; King, M.G.; Hara, H.; Hua, C.; Dakour, J.; Marusyk, H. Melanin Pigments and Melanosomal Proteins as Differentiation Markers Unique to Normal and Neoplastic Melanocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1993, 100, 259S–268S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotobuki, Y.; Tanemura, A.; Yang, L.; Itoi, S.; Wataya-Kaneda, M.; Murota, H.; Fujimoto, M.; Serada, S.; Naka, T.; Katayama, I. Dysregulation of melanocyte function by Th17-related cytokines: Significance of Th17 cell infiltration in autoimmune vitiligo vulgaris. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matano, F.; Yoshida, D.; Ishii, Y.; Tahara, S.; Teramoto, A.; Morita, A. Endocan, a new invasion and angiogenesis marker of pituitary adenomas. J. Neurooncol. 2014, 117, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Bjerkvig, R.; Wiig, H.; Melero-Martin, J.M.; Lin, R.Z.; Klagsbrun, M.; Dudley, A.C. Inflamed tumor-associated adipose tissue is a depot for macrophages that stimulate tumor growth and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2012, 15, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvi, P.; Chaube, B.; Singh, S.V.; Mohammad, N.; Pandey, V.; Vijayakumar, M.V.; Radhakrishnan, R.M.; Vanuopadath, M.; Nair, S.S.; Nair, B.G.; et al. Weight control interventions improve therapeutic efficacy of dacarbazine in melanoma by reversing obesity-induced drug resistance. Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, M.; Chen, J.; Ye, Y.; Tseng, H.-Y.; Lai, F.; Tay, K.H.; Jin, L.; Guo, S.T.; Jiang, C.C.; Zhang, X.D. Adipocytes Contribute to Resistance of Human Melanoma Cells to Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Chiang, H.C.; Sun, X.; Yuan, B.; Mitra, P.; Hu, Y.; Curiel, T.J.; Li, R. Genetic ablation of adipocyte PD-L1 reduces tumor growth but accentuates obesity-associated inflammation. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloia, A.; Müllhaupt, D.; Chabbert, C.D.; Eberhart, T.; Flückiger-Mangual, S.; Vukolic, A.; Eichhoff, O.; Irmisch, A.; Alexander, L.T.; Scibona, E.; et al. A Fatty Acid Oxidation-dependent Metabolic Shift Regulates the Adaptation of BRAF-mutated Melanoma to MAPK Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6852–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, G.; Avgustinova, A.; Mejetta, S.; Martín, M.; Castellanos, A.; Attolini, C.S.O.; Berenguer, A.; Prats, N.; Toll, A.; Hueto, J.A.; et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature 2017, 541, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, F.X.; Wei, C.S.; Xu, Y.T.; Ma, L.; He, Y.L.; Shi, X.E.; Yang, G.S.; Yu, T.Y. MicroRNA-214-3p targeting ctnnb1 promotes 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation by interfering with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Fu, M.; Bookout, A.L.; Kliewer, S.A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. MicroRNA let-7 regulates 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 23, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Barry, S.; Kmetz, D.; Egger, M.; Pan, J.; Rai, S.N.; Qu, J.; McMasters, K.M.; Hao, H. Melanoma cell-derived exosomes promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition in primary melanocytes through paracrine/autocrine signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016, 376, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazurkiewicz, J.; Simiczyjew, A.; Dratkiewicz, E.; Ziętek, M.; Matkowski, R.; Nowak, D. Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020529

Mazurkiewicz J, Simiczyjew A, Dratkiewicz E, Ziętek M, Matkowski R, Nowak D. Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(2):529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020529

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazurkiewicz, Justyna, Aleksandra Simiczyjew, Ewelina Dratkiewicz, Marcin Ziętek, Rafał Matkowski, and Dorota Nowak. 2021. "Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 2: 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020529

APA StyleMazurkiewicz, J., Simiczyjew, A., Dratkiewicz, E., Ziętek, M., Matkowski, R., & Nowak, D. (2021). Stromal Cells Present in the Melanoma Niche Affect Tumor Invasiveness and Its Resistance to Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020529