Abstract

Nitrate (NO3–) and auxin are key regulators of root growth and development, modulating the signalling cascades in auxin-induced lateral root formation. Auxin biosynthesis, transport, and transduction are significantly altered by nitrate. A decrease in nitrate (NO3–) supply tends to promote auxin translocation from shoots to roots and vice-versa. This nitrate mediated auxin biosynthesis regulating lateral roots growth is induced by the nitrate transporters and its downstream transcription factors. Most nitrate responsive genes (short-term and long-term) are involved in signalling overlap between nitrate and auxin, thereby inducing lateral roots initiation, emergence, and development. Moreover, in the auxin signalling pathway, the varying nitrate supply regulates lateral roots development by modulating the auxin accumulation in the roots. Here, we focus on the roles of nitrate responsive genes in mediating auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis root, and the mechanism involved in the transport of auxin at different nitrate levels. In addition, this review also provides an insight into the significance of nitrate responsive regulatory module and their downstream transcription factors in root system architecture in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

1. Introduction

Roots are crucial for the anchorage of plants in the soil and facilitate the translocation of water and mineral nutrients. Thus, plant roots play an essential role in plant metabolism [1]. The root system is composed of primary root (embryonic roots) and postembryonic roots (lateral roots). Root system architecture (RSA) is the general spatial arrangement of individual parts of the root system and enables the plant to acquire adequate resources from the soil. The rate at which individual parts of the root system develop and grow can be reformed by their response to environmental signals, including changes in water, nutrient, and oxygen availability, or pathogens and pests [2,3].

Nitrogen (N) is in two major forms nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+), which plays a vital role in the root growth and development of the plant. It was suggested that lateral roots (LRs) formation is regulated by NO3− and NH4+ ratio via modification of the polar auxin transport [4]. NH4+ ions were found to dramatically suppress Arabidopsis root growth in the absence of K+, even though NO3– is available [5]. The ammonia transporter gene AtAmt1.1 has also been found to play a critical role in restructuring LRs architecture under N-starvation [6,7]. However, the majority of the plants preferentially uptake nitrogen in the form NO3– in aerobic soil [8], and by contrast, only a few grow well when taking N only from NH4+ [4]. This uptake system of N by the roots is under the synchronized control of nutrients availability and hormonal signalling [2,3].

Nitrate (NO3−) plays a signal regulatory role in many physiological processes including root growth. The nutrient uptake efficiency depends on root system architecture in the soil [9], and these processes are controlled by several gene-transcript levels, which are regulated by NO3− [10]. NO3– regulates root branches under various signalling pathways, such as NRT1.1 (dual-affinity NO3− responsive gene), which is assumed to participate in the nitrate-sensing system [11,12], and also governed by auxin [13].

Signalling communication is a general rule rather than an omission. For instance, it is cited that about 1545 genes were the nutrient-related signals of NO3−, NH4+, or both nitrogen forms. Also, 982 (64%) genes were controlled by hormonal signals [14]. Several studies reveal that hormone biosynthesis, transport, and transduction are significantly influenced by several mineral nutrients [11]. Hormones play a key role in the root-growth adaptation to NO3− readiness [13]. Numerous studies have also shown that NO3− regulation of root system architecture (RSA) entails an overlap between NO3− and auxin signalling pathways [13,15]. IAA is the most researched and best naturally occurring active auxin [12], and it plays a specific role in the control of systemic inhibition of fresh lateral roots (LRs) developments in response to the sufficient supply of nitrate [16]. Both external NO3− and IAA supply significantly influence the auxin concentration in the tiller nodes [17]. As part of the root system, lateral root not only depends on the external NO3− supply, but also on the amount of internal NO3− supplied to the plant root system [18].

Several studies on transporter/channels as well as nutrient responses have been reported for many years. However, at the more basic level, important mechanisms of the signalling overlap between nitrate and auxin in lateral root initiation, emergence, and development in Arabidopsis are still poorly understood. In this review, we focus on an in-depth role of NO3− in auxin-induced signalling, and the relationship between NO3− and IAA transcript levels in the regulation of lateral root initiation, emergence, and development in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

2. Classification of Nitrate Responsive Genes

Root growth and development are influenced by the plants’ nutritious status and the external availability of the nutrients [19,20]. NO3− is taken up by the root cell is considered to be a key constituent of the N metabolism. Moreover, the NO3− can be subsequently excreted from the root cell by the primary extrusion from the external medium or unloading in the xylem vessel to reach the aerial organs of the plant [21]. For such nitrate transport through the cellular membrane, NO3− influx is an active process [21]. The recognizable proof of the proteins and the transport process of NO3− inside the plants are essential to understand the components that control NO3− retention and distribution within the entire plant. Here, we classify the genes that potentially involved in NO3− responses [20,22], as short-term and long-term responsive (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3), which are described in detail below.

Table 1.

Short Term Primary Nitrate Responsive Genes.

Table 2.

Long Term and Short Term Nitrate Responsive Genes.

Table 3.

Long Term Nitrate Responsive Genes.

2.1. Short Term Primary Nitrate Response (PNR) Genes

In Arabidopsis, NRT1.1 is one of the chief low-affinity nitrate transporter gene, which affects the root growth in nitrate-responsive signalling, and toggles from the low nitrate condition to high nitrate condition by its phosphorylation of at the Thr101 by CIPK23 kinases (Table 1). NRT1.1 activates a specific nitrate signalling pathway, thereby regulating RSA, and subsequently stimulating LR growth under low and high NO3− supply [55]. It is also evident that auxin might be a secondary signal, triggering the regulatory action of NRT1.1 on LR growth and development. NRT1.1 transports nitrate and also encourages the uptake of auxin. In contrast, NO3− also inhibits NRT1.1-mediated IAA uptake, which revealed that nitrate signal transduction alters the transport of auxin via NRT1.1. Moreover, NRT1.1 functions in phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation in response to diverse nitrate conditions [56,57] (Table 1).

In addition to NRT1.1, lateral organ boundaries domain (LBD) LBD37/38/39 have been recently identified to be essential nitrate regulatory genes that suppress several N responsive genes required for NO3– uptake and assimilation, and influence NO3− content [58,59]. LBDs regulates EXPANSINA 17 (EXPA17), a gene encoding cell wall loosening factor by coupling with EXPA17 to enhance lateral root emergence. Overexpression of EXPA17 increases LRs emergence density in the presence of auxin compared to wild type (WT) [60]. Studies have also shown that LBD18 regulatory gene EXPANSINA 14 (EXPA14) expression is involved in the apical tissue of LRs primordium. Collectively, these findings confirm that LBD18 up-regulates a subset of EXPAs genes to enhance cell division which promotes LR emergence in Arabidopsis [61]. Moreover, LBDs act downstream of the auxin influx carrier AUX1 and Lax1, regulating LR initiation and development [62,63]. These transient developmental phases are further synchronized by the action of microRNA (miRNA) families miRNA156 and miRNA172 [20]. It was revealed that miRNA156 targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) genes SPL3, SPL9, and SPL10, which are involved in the suppression of lateral root growth. This further suggests the function of both miR156 and SPLs in LR development by their response to auxin signalling [22]. SPL9 was identified to be a sentinel short-term nitrate-responsive gene [57], which is targeted by miR156, while rSPL9 (overexpression plants of SPL9) are resistant to the degradation of miR156 [64]. Thus, the miR156-resistant transgenic plants were identified as the rSPL9 mRNA, generated from the modified gene resistant to degradation by miR156. This demonstrated the role of the SPL9 in the regulation of genes involved in the primary NO3− response. It was further demonstrated that the role of SPL9 over-expression on the transcription factor (TF) levels of genes in the network over time leads to a significant increase in NRT1.1, NIA2, and NIR1 in response to NO3− [57] (Table 1). Moreover, TAA1 and TAR2 are involved in auxin biosynthesis, keeps the appropriate root auxin concentration, and the preservation of root stem cell niches (https://www.uniprot.org/).

From the genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis, it was revealed that JR1 (JOSMONATE RESPONSIVE 1) was related to LR length in low and high NO3− condition. Compare to high NO3− condition, there is a specific defect in the average length of the LRs under low NO3− condition. This is an indication that JR1 functions in regulating LRs length under low N condition [58]. Subsequently, the two genes JASMOANTE RESPONSE (JR1) and D AMINO ACID RACEMASE2 (DAAR2) are involved in lateral root growth under low nitrate conditions [58,59].

Under NO3− deficient conditions, NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 are down-regulated in the cbl7 mutants, and therefore accumulate lower NO3– content compared to WT plants, and subsequently inhibit the root development upon nitrate starvation in cbl7 [65], which indicates that CBL7 enhances root development when expressed in the roots of the young seedlings, which is induced by NO3– starvation [65]. In addition, short-term responsive gene family NITRATE-INDUCABLE GRAP-TYPE TRANSCRIPTIONAL REPRESSOR (NIGT1s) transcription factors, incorporated in nitrate starved condition and act as a downstream sensor and transporters of NPF6.3/NRT1.1 to repress primary root growth in the nitrate sufficient condition [66]. The transcriptase and co-transfection analysis showed that NLPs auto-regulate and control the NIGTs [67]. It is also suggested that NRT2.1 is independently regulated by NIGTs and NLP7 because of their different binding sites. Moreover, the NLP-NIGT1 transcriptional cascade controls the targeted genes together by NLP7-mediated activation, while it independently induces repression [67].

The CBL-interacting protein kinases, CIPK8 and CIPK23, are involved in short-term primary nitrate response. Similarly, the subcellular Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CPKs), such as CPK10, CPK30, and CPK32, are necessary for instant nitrate-stimulated cellular and metabolic responses and nitrate-induced root to shoot growth. Under sufficient nitrate conditions, Ca2+-sensor CPKs move to the nucleus, whereas CPK10 targets NLP7S205 phosphorylation to hold NLP7 inside the nucleus in a nitrate-dependent manner [68,69]. Furthermore, nitrate regulatory gene 2 (NRG2) also plays a critical regulatory role in plant primary nitrate responses (PPNR) based on their binding affinity for nitrate [70]. In addition to NRG2, FPI1 genes (factor interacting with poly (A) polymerase 1) enforce a specific role in nitrate signalling in Arabidopsis. FIP1 is an important part of the polyadenylation factor complex. FIN219-interacting protein 1 (FIP219) have also been demonstrated to be rapidly stimulated by auxin and confined consistently in the cytosol without fluctuation in subcellular localization by light [71]. FIN219 was exhibited to be a silencer of COP1 [71], thus demonstrating the role of FIN219/JAR1 as a significant regulator in modulating auxin-mediated phytohormone signalling. However, its physiological function in light signalling and plant development remains unclear [28]. It was also found that FIP1 interacts with cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30-L (CPSF30-L), which is also an indispensable player in NO3– signalling [29]. CPSF30 significantly reduced the primary root length and exhibits fewer LRs when CPSF30 mutant oxt6 was grown on medium containing IAA [72].

2.2. Short and Long Term Nitrate Response Genes

As stated earlier that CIPK8 functions as a positive regulator under high and low nitrate conditions [30,40]. The cipk8 mutant was repressed mainly in NO3– limited condition, and its response to both high and low-affinity nitrate signalling system is suggested to be genetically distinct. This indicates that CIPK8 is involved in low nitrate conditions. Similarly, CIPK8 also functions in long-term nitrate modulated primary root growth and nitrate-induced expression of a vascular malate transporter [30,73].

Furthermore, the transcription factors belonging to the bZIP family, namely TGA1 and TGA4, are stimulated by NO3– in the Arabidopsis root [31]. TGA1 and TGA4 regulate the expression of NO3– transporter genes NRT2.1 and NRT2.2 [31]. The stimulation of both TGA1 and TGA4 is repressed in chl1-5 and chl1-9 mutants after NO3– application, which indicated that both TGA1 and TGA4 are regulated by nitrate transport, rather than the signalling function of NRT1.1 [31]. These findings suggest that TGA1 and TGA4 act as a primary nitrate responsive genes (Table 2).

Another short-term and long-term nitrate responsive transcription factor, NLP7 plays a prominent role in the LRs growth in response to nitrate, promotes the LRs density in high NO3− condition, acts as nitrate sensing and assimilation, suggested to be short-term PNR gene. However, the nlp7 mutant exhibited lateral roots inhibited phenotypes on split-root plates in both high and low nitrate conditions, further suggesting that NLP7 may mediate local nitrate response [23,42]. Conversely, the present findings indirectly strengthen the possible function of the NLP7 in regulating the LRs growth in varying nitrate conditions, which suggests the role of NLP7 as long-term nitrate response gene [50]. In addition to NLP7, the transcription factor that regulates the expression of the prototypical NO3– response gene is SPL9 [57].

2.3. Long Term Nitrate Response Genes

When the supply of nitrogen becomes limited, the long-term high-affinity type transporters enabling the nitrate uptake, are expressed in the root to enhance the efficacy of nitrogen acquisition [45,46] (Table 3). Among them, the nitrate inducible MADS family protein ANR1 promotes lateral root in response to nitrate [60]. NRT1.1 and its downstream MADS-box transcription factor ANR1 mediate local signalling [32,74]. In the long-term mechanism, ANR1 functions as a positive regulator in the signalling pathway of nitrate-induced LRs proliferation [75,76].

Another long-term high-affinity nitrate regulatory gene NRT2.1 involved in the NO3− uptake, are responsible for the accumulation and induction of the transcript in the root under low nitrate conditions [77]. Similarly, microRNA (miRNA) emerged as a key regulator in nitrate-induced root growth and development. miR167 targets and regulates the expression of auxin response factor (ARF8), and both ARF8 and miR167 are expressed in the root cap [43,78]. ARF8 is accumulated in the pericycle by inhibition of miR167 under nitrate availability and subsequently display an increased ratio of initiation vs. emerging LRs in response to NO3− treatments [42]. Moreover, miR393 was activated in response to nitrate supply, mainly by binding the auxin AFB3 transcript and subsequently modulating the accumulation of AFB3 mRNA in the root in response to nitrate treatments [79].

In A. thaliana plants, CLE41, a homolog of the phloem-derived secretory peptide tracheary element differentiation inhibitory factor (TDIF) [45], and the CLE41 peptides (CLE41p) stimulated the proliferation of vascular cells, despite the delay in its division into phloem and xylem cell lineages. CLE19/41/44/TDIF are localized in the vascular stem cells and function in the maintenance of LRs emergence [80,81]. In response to high nitrate availability, HNI9/AtIWS1 (HIGH NITROGEN INSENSITIVE9) plays an important role in the systemic regulation of root NO3− uptake in Arabidopsis [32], and functions as an inhibitor of NRT2.1 transcription in the root [82]. Moreover, it plays a significant role in N signalling by regulating hundreds of NO3− responsive genes in the root [82]. Among other, long-term nitrate responsive TFs, that function in lateral root development of A. thaliana, CLEs-CLVs related peptides function as a regulatory module in the nitrate signalling pathway and negatively regulates LRs growth under limited nitrate supply [80,83]. Similarly, CEP hormones, 15-amino-acid peptides, act as negative regulatory hormones in growth and development. CEP1 is a candidate for a novel peptide plant hormone, mainly expressed in the lateral root primordial, and its overexpression significantly inhibits root growth [80]. These polypeptides are imported into the roots to activate nitrate transporter genes in the rhizosphere under a sufficient supply of NO3− [81]. In addition, AtTCP20 is also another nitrate responsive transcription factor, which modulates LRs in nitrate dependent manner, and is studied in chrysanthemum and heterologous overexpression in Arabidopsis. The overexpression of CmTCP20 significantly increased the number and average length of lateral root (LRs) compared with the wild type in chrysanthemum and Arabidopsis [78], indicating that TCP20 is regulated by NO3−, supplied to N starved roots.

Members of the bZIP transcription factor family, TGA1 and TGA2, are induced by nitrate in the roots [31]. Transcriptome analysis of roots showed that differentially expressed numbers of genes regulated by nitrate availability suggest tga1tga4 as a double mutant. Moreover, TGA1 and TGA4 significantly decrease the induction of its target genes NRT2.1 and NRT2.2. Further findings showed that TGA1 could bind NRT2.1 and NRT2.2 and regulates their expression [42,84]. As stated earlier, adequate NO3− suppresses the level of miR167a to allow the accumulation of ARF8 transcript in the pericycle upon nitrogen treatments, while under low NO3− condition miR167a targets ARF8 [23]. Similarly, the AFB3 transcriptional factor plays a significant role in coordinating LRs and primary roots under adequate nitrate supply. Nitrate also activates NAC4, as downstream of AFB3, which is an essential part of regulating the nitrate-responsive system, the mutants of NAC4, nac4 showed altered LR growth. Meanwhile, the primary root growth remains normal under nitrate state. Thus, AFB3 regulatory network confers changes in LRs development in response to nitrates [49], which confirms the long-term role of these transcripts in response to NO3−.

Similarly, the complex overlap between nitrate and phytohormone auxin signalling pathways are regulated by genomic distinctiveness. This induces the allelic variety of genes. ROOT SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE 1 (RSA1) and PHOSPAHT TRANSPORTER 1 (PHO1) are the two genes regulating allometric parts of root system architecture (RSA), however the mechanisms through which their NO3− and IAA signalling pathways regulate the root architecture remains to be understood [82].

3. Nitrate Responsive Genes Enhances Auxin Activity in the Roots

Nitrate (NO3−) supply can alter auxin biosynthesis and its transport [40,85,86]. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is an essential plant native auxin [53], which is required for plant growth and development under diverse environmental conditions [87]. In Arabidopsis roots, the decay of auxin cannot be achieved by the translocation of auxin from shoot to root, which indicated that shoot localized auxin alone is not adequate for supporting the root initiation, elongation, and development [84]. Auxin transportation has been hypothesized to be crucial intercellular and intracellular IAA distributions in the plant. Inside the plant cells, it was reported that for the directional anionic auxin and formation of the polar flow, it needs transporters and their uneven localization [88]. This evidence revealed that roots nitrate transcriptionally regulate the transport and biosynthesis of auxin [89].

To date, few transcription factors that contribute to NO3− dependent auxin efflux have been studied. For instance, nitrate responsive genes which include NRT1.1, NRT2.1, NRT2.2, NIA1, NIA2, NIR, and Arabidopsis Nitrate Regulated (ANR1) [75]; TAR2 (tryptophan aminotransferase related 2) [90]; NIN like Protein 6 (NLP6) [91]; NIN-Like Protein 7 (NLP7) [92]; LOB Domain-Containing proteins (LBD37/38/39) [62]; Squamosa Promoter Binding Protein-Like 9 (SPL9) [93]; Basic Leucine-Zipper 1 (bZIP1) [94]; NAC Domain Containing Protein 4 (NAC4) [49]; TGA1/TGA4 [31], Teosinte Branched1/Cycloidea/Proliferating Cell Factor 20 (TCP20) [78]; and Nitrate Regulatory Gene 2 (NRG2) [70]. Moreover, the link between NLP6 & 7, TGA1, bZIP1, and TCP20 with the promoter of the genes of interest was also confirmed [87].

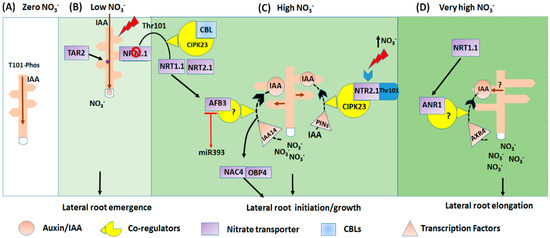

It has been reported that in the roots TAR2 expression is significantly increased compared to TAA1, which is induced moderately under low NO3− condition. However, in shoots, both genes were repressed. TAR2 was expressed in the root pericycle and also the vasculature of the root maturation zone close to the root tip [85] (Figure 1). The mild NO3− deficiency positively affects LRs formation in Arabidopsis which required an auxin biosynthesis gene TAR2. A change L-Trp to indole-3-pyruvic acid (IpyA) by TAR2 is the first step in the IpyA pathway branching from a Trp-dependent auxin pathway [90]. Under low NO3− source, the TAR2 expression was up-regulated, resulting in an increase in IAA levels in the developing LRs. Nevertheless, the tar2-c null mutants exhibit much shorter total LR length and fewer visible LR numbers, demonstrating that mutation of TAR2 reduced the LR formation [85]. Therefore, low NO3− stimulated LR emergence depended on root-synthesized auxin in a TAR2-dependent manner [50]. So far, all the NRTs-dependent hormone transporters are involved in the local redistribution of the hormones within the plant [40]. NO3− transporter enhances the redistribution and transport of auxin at a short distance [95,96]. For instance, NRT1.1 transports auxin (IAA), and consequently overlaps nitrate and auxin (IAA) signalling pathways [40]. NRT1.1 transports the auxin from the lateral root primordial under low nitrate condition, thus suppressing the development of LR primordia and fresh LRs. However, at optimum nitrate condition, the repressed NRT1.1-dependent IAA transport was activated, which result in subsequent accumulation of auxin in the LRs and promotion of the primordium growth [52,81]. Under the low N condition, the nrt2 mutant suppresses the lateral root emergence and the IAA storage in the LRs primordia [85].

Figure 1.

NO3− regulates auxin activity, and consequently controls the NO3− assimilation pathway and transport. The model represents the root morphology subjected to four different nitrate conditions. (A) The deficient (zero) NO3− stimulates auxin translocation from shoot to roots. (B) This mechanism is utilized under low NO3− conditions, either NRT1.1 transport auxin from shoot to root, causing LRs emergence, or reduced the auxin storage in primordia and new lateral root tip, and subsequently inhibits LRs emergence and elongation. Thus considered as the principal regulator for the auxin biosynthesis in the root promotes lateral root growth. (C) Under the high nitrate NO3− condition; NRT1.1 induces the expression of AFB3, and the AFB3-dependent auxin signalling, regulates root growth. The AFB3-NAC4-OBP4 signalling network expressed their protein in the root pericycle of the cell. The NAC4 and OBP4 part of the pathway is probably regulated by AUX/IAA protein IAA14. The black dotted arrow indicates the effect of AFB3 on the IAA accumulation, promotes lateral root initiation under high nitrate condition. (D) Under the excessive supply of NO3−; NRT1.1 stimulates the ANR1-dependent signalling pathways that modulate lateral root elongation. The black dotted arrow indicates the effect of NRT1.1 on the IAA accumulation and expression of ANR1 in the LRs primordial, and lateral root development. The question mark represents the unconfirmed effect of NRT1.1 nitrate transport activity on the expression of ANR1 [97].

NLP7 is the primary auxin-efflux protein’s carrier localized in the plasma membrane [44]. NLP7-induced auxin efflux activates PIN7 [88]. Further studies have shown that NLP7 encodes 851 genes under optimum nitrate conditions. In addition, new nitrate regulatory factor NITRATE REGULATORY GENE 2 (NRG2), disrupts the stimulation of NO3− sensor genes in the nrg2 mutant when subjected to nitrate treatments. This indicates the physical interaction of NRG2 with NLP7 in the nucleus [87]. Similarly, NIGT1s expression is auto-regulated and controlled by NLPs. Therefore, NIGT1s inhibit the NRT2.1 stimulation by NLP7 [67]. NLP7 regulates the fluctuation in local auxin by controlling the auxin-efflux to build up and sustain the root primordium and determine the LRs number [88]. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling data revealed that NLP7 and TAR2 are among the top NLP7-activated genes, in addition to the nitrate inducible genes such as NiR, NIA1, FNR2, and NRT2.1 [32,78]. A transcriptomic study demonstrates that an auxin bio-module containing auxin carrier 9 (including among others PIN1, PIN2, PIN4, and PIN7) is specifically regulated by NO3− [98]. Furthermore, it suggests TCP20-NLP6/7 complexes as the upstream target of the Auxin- ROP2-TOR-E2Fa/b signalling pathway [89].

In Arabidopsis root, a nitrate responsive miR393/AFB3 regulatory module, which assimilates nitrate and auxin signals control both primary and LRs growth [49], and is capable of stimulating the nitrate (5 mM) signal to promote root growth in response to auxin. Independent of nitrate metabolism and transport, AFB3 induces auxin signalling, shows sensitivity and response to NO3−, subsequently regulate LRs growth and functions as downstream of nitrate signalling [49]. Family of no apical meristem (NAM)/activating transcription factors/cup-shaped cotyledon (ATF/CUC) proteins, and it’s targeted genes OBP4, acts as a downstream target of ABF3 gene. The interactive signalling network of AFB3-NAC4-OBP4 with their existing protein expression in the pericycle cell of the root is required for the nitrate inducible LRs initiation and emergence (Figure 1). The part of NAC4-OBP4 signalling pathways is possibly regulated by AUX/IAA proteins, IAA14 [49,99] (Figure 1).

Under nitrate deficient condition, the AGL17-clade MADs-box gene, AGL21, and auxin promote longer LRs in Arabidopsis. However, the overexpression (OE) of AGL21 significantly up-regulates the auxin biosynthesis genes YUC5, YUC8, and TAR3, and is down-regulated in agl21 mutants. Ag121 mutants showed a decrease in the rate of LRs elongation in low nitrate supply, demonstrating that AGL21 promotes the local auxin biosynthesis in the LR primordia and LRs, thus positively regulating LRs development [100].

Studies have shown that SPL may function in the auxin homeostasis. To this end, OE of SPL led to the downregulation of auxin reporter DR5-GUS, and subsequently down-regulate several auxin-responsive genes in the leaves of spl-D. Further studies have shown that the two auxin biosynthesis genes, YUC2 and YUC6 were significantly suppressed in spl-D plants. Both genomic and phenotypic studies on spl-D/yuc6-D double mutant revealed that SPL might control auxin homeostasis by suppressing the transcription of YUC2 and YUC6 and contributing to lateral organ morphogenesis [48].

The report of Cui-Hui Sun showed that under low NO3− condition, the nitrate signalling pathway has a specific stimulatory effect on the LRs growth. The molecular players’ complexes involved in these pathways regulate various stages of LR development and also influence auxin biosynthesis and transport [50]. These findings demonstrate that nitrate (NO3−) signalling constituents function upstream of auxin biosynthesis, transport, and control of LR development.

4. Nitrate Signalling Pathways and Auxin Response

The NO3− and IAA cross-talk was first identified by Goerge S. Avery and Louise Pottorf in the 1940s. They demonstrated a direct relationship between NO3− and IAA supply [101]. Numerous studies have also revealed that the interaction between NO3− and the auxin signalling pathways that regulate RSA [39]. Presently, the molecular mechanism of NO3− signalling transduction has been revealed in Arabidopsis [43]. NRT1, NRT2, CLC (Chloride Channel), and SLAC1/SLAH (slow anion channel 1/ SLAC1 homolog) are the four nitrate transporters families that have been characterized in Arabidopsis [102].

4.1. Nitrate Uptake

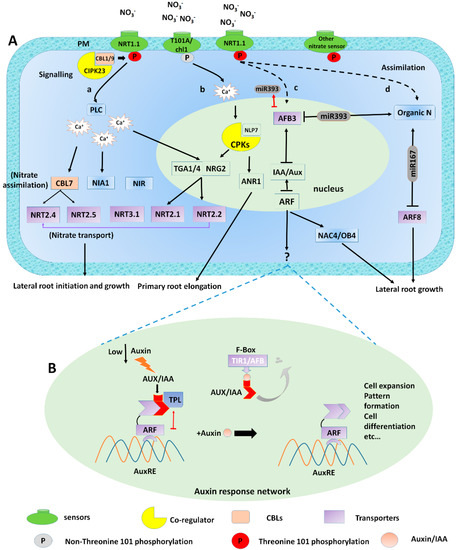

NRT1.1 is phosphorylated by the CBL1/9-CIPK23 complex [102,103]. Nitrate is absorbed into the root cell by plasma membrane-localized transporter family, NRT1 and NRT2 [104]. Under limited nitrate condition, CBL1/9 interacts with CIPK23 to form the CBL1/9-CIPK23 complex, which phosphorylates NRT1.1 at the threonine site T101, for efficient NO3− transport [104,105] (Figure 2). This phosphorylation promotes NRT1.1 enrolment into functional membrane microdomains at the plasma membrane (PM). This activity enhances the NRT1.1-dependent auxin flux, and as a result, drains the auxin level from the LR tips and limits growth. When the NO3− supply was increased, the non-phosphorylated NRT1.1 shows oligomerization, reduced lateral mobility at the PM and exhibits inducible endocytosis. This activity promotes LR growth, induces NRT1.1-auxin transport activity at the PM, and stimulates Ca2+-ANR1 signalling from the endosomes [54].

Figure 2.

Signalling mechanism of nitrate mediated auxin modulation induces lateral root growth; (A) (a) NRT1.1 initially senses, taken up and transport by the NRT1.1 transporter, thereby changing its uptake affinity and modulating phosphorylation to activate signalling pathway. In low nitrate conditions, the phosphorylation switches NRT1.1 into the high-affinity system. This sensing ability of NO3− altering NRT1.1 phosphorylation causes calcium (Ca2+) efflux by the activation of phospholipase C (PLC). This results in varying the expression of (TGA1/4*) and nitrate transporter genes (NRT2.1, NRT2.2, NRT3.1) and nitrate assimilation genes (NIA1 and NiR). (b) T101A/chl1 mutant triggers Ca2+-ANR1 signalling from the endosomes under high NO3− supply. (c) Under adequate NO3− supply, AFB3 regulates NAC4 and OBP4 expression, which as a result affect the root renovation. (d) Finally, as a result of nitrate assimilation organic nitrogen is produced, this system includes miR167 and miR393, which regulates AFB3 and ARF8, respectively (B) In Auxin response network; Class ARF directly connects to the AuxRE (red arrow). Under low nitrate conditions, AUX/IAAs and TPLs repress transcriptional activation by class-ARFs. The degradation of Aux/IAA released this inhibition by connecting auxin and TIR1/AFB. (See text for further details).*TGA1/4 regulatory factors mediate nitrate response inside Arabidopsis root, and while the link of TGA4 to PLC is not approved. Other transcription factors, for instance, NRG2, NLP7, connection to Ca2+ signalling is currently unknown.

The phosphorylation activates the high-affinity nitrate transporter NRT2.1 [106], and stimulation of NRT1.1, NRT2.1, NRT2.2, and NRT2.4 was reported under nitrate starved seedlings after nitrate supply and all the nitrates assimilation genes were up-regulated [107,108]. Studies have identified the roles of the Ca2+ in the nitrate signal transduction and stimulate nitrate-inducible regulation of the genes expressed in Arabidopsis. It was observed that nitrate treatments significantly increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels in the roots and the seedlings of the plants [109] (Figure 2). NRT1.1 is governed by two modes of phosphorylation at Th-101 residue to regulate LRs growth, modulating NO3− dependent basipetal auxin transport and NO3− induced signal transduction. By using the two Arabidopsis phosphomimetic NRT1.1T101A and non-phosphorylatable NRT1.1T1101D mutants respectively [54], NRT1.1T101D has presented the fast lateral mobility and membrane partitioning that enabled auxin flux under low-nitrate conditions while In contrast NRT1.1T101A mutants showed low lateral mobility and oligomerized at the plasma membrane (PM), where it induced endocytosis under high NO3−. These activities stimulate LR development by suppressing NRT1.1-mediated auxin transport on the PM and inducing Ca2+-ANR1 signalling network from the endosomes [54] Figure 2A. To this end, phosphorylation mediates the calcium flux in the PM by NO3− transporter NRT1.1, subsequently regulates auxin flux and nitrate signalling in lateral roots development [54]. These studies indicated that NO3− mediated Ca2+ flux modulating auxin response and polar auxin transport in the root growth and development.

4.2. Auxin Response Network

It was previously reported that auxin-NO3− pathway by identifying a passive feed-forward mechanism consisting of auxin receptor auxin signalling F-box 3 (AFB3) and microRNA miR393 [79]. The expression of AFB3 protein in response to NO3−, indicating Ca2+-independent pathways that regulate the nitrate-sensitive genes [109] (Figure 2A). Under high nitrate conditions, AFB3 is stimulated, whereas, under lower NO3−, miR939 induced by nitrate reduction and assimilation which produces N metabolites, and subsequently AFB3 suppressed by miR393 [79] (Figure 2A). Furthermore, it was established that nitrate-AFB3-NAC4-OBP4 mediated perception, signalling and response of auxin in a nitrate-dependent manner is mainly regulated by multiple signalling mechanisms and their coordination under unfavorable nitrate condition [68]. Nitrate-specific induction of AFB3 inside the root may regulate a specific signalling network of Aux/IAA and ARF factors that modulate NAC4 activation. AFB3 regulates the transcription of the IAA-responsive gene by promoting the degradation of the Aux/IAA transcriptional repressor of auxin [110] (Figure 2A). The microRNA, miR167, and its target auxin-responsive factor ARF8 mRNA [42] function to regulate several genes connected via a network and activate the lateral root initiation and inhibition of elongated roots in response to NO3− [42] (Figure 2A).

Auxin stabilizes the communication among TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE1/AUXIN SIGNALLING F-BOX proteins (TIR1/AFB3) and Domain II of AUXIN/INDLOE-3-ACETIC ACID (AUX/IAA) transcriptional co-regulators to stimulates the ubiquitin-dependent breakdown of AUX/IAA protein in the 26S proteasome [111] (Figure 2B). When the auxin concentration is low, individuals from the AUXIN/IAA-INDUCIBLE (AUX/IAA) family of transcriptional repressors bind with DNA-binding protein of ARF [112,113], which exactly possess auxin-response promoter elements (AuxREs) in various auxin-regulated genes [114,115]. AUX/IAA protein inhibits the ARF function either by passively sequestering ARF protein away from their specific target promoters [116], or by interacting AUX/IAA with the co-repressor TOPLESS (TPL) to stimulate chromatin inactivation and silencing of ARF target genes [117]. The auxin concentration is increased by the auxin-stimulated module of co-receptor complexes, which include TIR1/AFBs family and an AUX/IAA member [118]. TIR1/ABFs specifically allows subunit of nuclear S-PHASE KINASE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 1-CULLIN-F-BOX PROTEIN (SCF)-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases (SCFTIR/AFB) and stimulate the recognition of substrate. The auxin response is initiated by connecting the hormones to the TIR1/AFB receptor. The auxin receptor is a constituent of the SCFTIR1/AFB ubiquitin ligase complex [119]. This complex binds auxin to its receptor TIR1/AFB to activate the formation and breakdown of the polyubiquitination of AUX/IAA repressor, and subsequently activates ARF that induces auxin-responsive gene transcription [120,121,122] and represents the pivotal role of auxin signalling (Figure 2).

In a nutshell, auxin-initiated AUX/IAA removal regulates ARF repression and activates the transcription of primary genes. [123]. The abundance of Aux/IAA-ARF modules chronologically generate new LRs and control LRs development in Arabidopsis model plant.

5. Relationship between Nitrate Level and Auxin Translocation between the Root and the Shoot

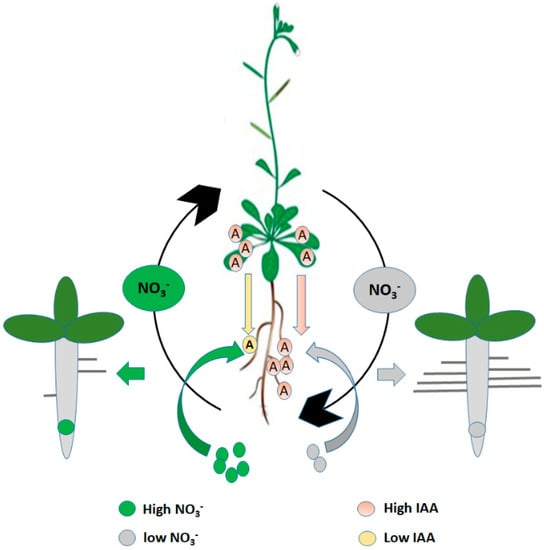

A decrease in NO3− supply tends to promote auxin translocation from shoots to roots [124] (Figure 3). Here, we discuss the mechanism involved in the transportation of the auxin in response to different NO3− concentrations and the influences of the auxin concentration on the root growth.

Figure 3.

The schematic model represents NO3− dependent shoot-root auxin transport and accumulation inside the Arabidopsis root. “A” represents auxin (IAA).

5.1. Auxin Translocation in Response to Nitrate Level

High NO3− concentration (50 mM) negates the lateral root growth [121]. These responses are linked with an auxin transport inhibitor. Previous studies have established that the internal supply of nitrate reduced shoot to root auxin transport and subsequently decrease root auxin concentration to a significant level for lateral root growth. Therefore, for the stimulation of the lateral root growth, change in the root auxin concentration alone is not adequate, as nitrate concentration is also a determinant factor [121,125]. There is a decrease in the level of auxin in the root when there is an adequate supply of nitrogen because the adequate supply of NO3− seems to inhibit auxin transport activity from the shoots to the roots. Furthers reports have shown that the external IAA concentration partially lowers the stimulatory effect of localized nitrate (Figure 3). This inverse relationship between nitrate and auxin concentration disrupts the LRs development [126].

As stated earlier, the auxin level in the roots is reduced by an adequate supply of nitrate (NO3−) which disrupted LRs development [126]. Moreover, The tissue auxin fixation was estimated in the roots 24 h after transferring the Arabidopsis seedlings from higher to lower nitrate medium [16]. Results indicated that the restricted root growth induced by 50 mM NO3− is replenished back to its normal growing state, 24-48 h after reducing the high nitrate (NO3−) concentration. It is worthy to note that if the auxin plays a role in controlling this process, its concentration in the root may depend on the time before activating the inhibited lateral root. Further revealed that, a 50% increase was observed in the IAA content of the root when moved to 1 mM NO3− compared to that of 50 mM NO3− [127]. Similarly, the seedlings grown under 1 mM NO3− has a root auxin concentration that was four-fold more than the plants grown on 8 mM NO3− condition [128]. This is also evident that high NO3− (8 mM) concentration significantly reduces the root auxin content [128]. Meanwhile, the high nitrate supply reduces the IAA concentration in the phloem exudates. Thus, the suppression of root growth by high nitrate could be linked to the reduced IAA level in the roots, particularly in the root tip region. It is speculated that the inhibitory effects of high nitrate concentration on the restricted root growth might be related to the decline in auxin content of the root [126].

5.2. Influence of Auxin Concentration on Root Growth

Recent studies demonstrated that auxin accumulation in the LRs primordia overlaps with the low nitrate-stimulated expression of TAR2 in the root [16,85]. The application of the 2-4-carboxyphenyl-4, 4, 5, 5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO) under NO3− supply, initiates auxin (IAA) level in the root [112]. In contrast to wild-type (WT), the ospin1b mutant has lower auxin level in their root, fewer LRs and shorter seminal root (SRs). These results demonstrate the effect of NO3− on LR arrangement and seminal root (SR) elongation by regulating auxin transport and NO3− [112]. NO3− and IAA regulate the expression of the rice adenosine phosphate isopentenyltransferase (OsIPT) genes, limit the cytokinin (CTKs) biosynthesis in the tiller nodes, thereby regulating the development of tiller bud in rice [17]. Similarly, it is revealed that there was no increase in LRs elongation of auxin resistant axr4 when subjected to low nitrate conditions [113]. Reversed-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography (RP-UPLC) results on the plants showed that LR auxin concentration was increased while the nitrogen level decreased, hence the tea plant LRs formation might be stimulated by low nitrogen level via IAA biosynthesis and accumulation [129].

Auxin exhibits either a stimulatory or inhibitory effect on the primary and lateral roots of the plants depending on auxin concentration in the plants [130]. A reduced IAA (auxin) level in the roots inhibits LRs development [90], which is an indication of the NO3−-regulated auxin transport in the root. It has been inferred that NO3− increase in the shoot may repress the transition of auxin to the root, resulting in auxin-transport for LRs development [130]. However, in the auxin signalling pathway, high nitrate enhances LR development by influencing auxin levels in the roots. For example, at high external nitrate fixation, the LRs elongation in maize was repressed, due to a decrease of auxin translocation in phloem from shoot to root [90].

6. Nitrate Responsive Regulatory Module Initiates Root Growth

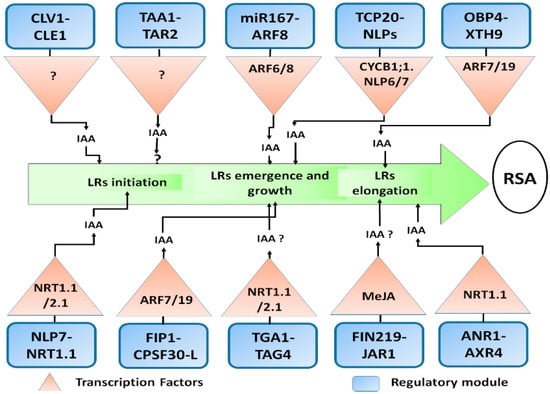

Nitrate modulates universal gene expression [131] (Figure 4), and some of the nitrate responsive regulatory modules are discussed here.

Figure 4.

Molecular players involved in nitrate signalling regulating the primary and lateral roots; Schematic presentation of a regulatory module involved in the nitrate-mediated auxin response in Arabidopsis root. For clarity purposes, all players and their secondary transcription factors (both upstream and downstream) are presented with blue and black colors respectively, which might not be the case in a plant cell. Auxin fluxes and accumulations contribute to primary and lateral root growth are indicated with the black arrow. However, the detailed mechanism and other transcripts are still unknown.

6.1. TAA1 and TAR2 Regulatory Module

Analysis of TAA1 and paralogues revealed a link between assimilation of local auxin, tissue-specific ethylene effect, and organ development. Indole-3-pyruvate (IPA) processed auxin synthesis is key to synthesize auxin response to light and environmental cues [36]. TAA1 and TAR2 are interlinked with auxin synthesis, required for keeping the suitable root auxin fixation and also required for the protection of root stem cell niches (https://www.uniprot.org/).

6.2. ANR1 and AXR4 Regulatory Module

There is an interaction between the ANR1-dependent pathway and auxin signalling [113]. However, it remains unclear whether there is a relationship between the ANR1 and the miR393/AFB3 module. It has been reported that NRT1.1 functions upstream of ANR1, as it regulates LRs elongation, obviously by its role as NO3− sensor [55]. In addition, NO3− signal activated by NO3− sensor (targeted at the PM), is transmitted by pathways that consist of the products of ANR1 and AXR4 genes. The possible function of AXR4 and whether it lies upstream or downstream of ANR1 in a signal transduction pathway remains unclear [96].

6.3. TGA1 and TAG4 Regulatory Module

Using the integrative bioinformatics approach, TGA1 and TGA4 TFs were shown to mediate NO3− responses in Arabidopsis roots. The ATH1 Affymetrix microarray analysis showed that tga1/tga4 double mutants have different responses to nitrate compared to wild type. This implies that TFs regulate genes that participate in the NO3− transport and metabolic processes. Also, ChIP analysis indicates that the TFs control the expression of high nitrate affinity transporters NRT2.1 and NRT2.2 by binding to their promoters. This reveals that TGA1/TG4 & NRT2.1/NRT2.2 regulates the lateral root growth induced by nitrate signalling in Arabidopsis [31].

6.4. CLV1 and CLE1 Regulatory Module

This signalling module consisting of the nitrogen responsive (CLAVATA3/ESR-related) and leucine-rich occurring receptor-like kinase CLAVATAI (CLV1) are expressed in the root vasculature of Arabidopsis root [132]. CLV1 and CLE1 regulate the elongation of the root system under limited nitrogen conditions [132]. CLE1, -3, -4 and -7 stimulated by limited internal NO3− in the root, and mainly expressed in the cells of root pericycle [133]. In A. thaliana plants, the CLE41 peptides (CLE41p) promote the proliferation of vascular cells. This proliferation is dependent on auxin binding since it was improved by the exogenous application of synthetic auxin. This report established that vascular architecture is regulated by various CLE peptides related to hormonal signalling [74].

6.5. FIN219-JAR1 Regulatory Module

FIN219/JAR1 plays an exemplary role in regulating the combination of phytohormones in an auxin-dependent manner [28]. Specifically, Since FIN219 contains far-red (FR) light and methyl jasmonate (MeJA), that control various TFs including 94 basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TFs. Some of the loss of function mutant bHLH influenced by FIN219 demonstrate an altered response to MeJA in the regulation of the hypocotyl and root elongation. Thus, FIN219/JAR1 is specifically controlled by exogenous MeJA and interacts with different plant hormones to modulate the hypocotyl and root elongation of Arabidopsis seedlings, likely by regulating a group of TFs [118].

6.6. FIP1 and CPSF30-L Regulatory Module

It is reported that FIP1 interacts with the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30-L (CPSF30-L), which is also a fundamental player in nitrate signalling [29]. To study the expression of CPSF30 in the LRs by qRT-PCR plant poly (A) signal (PAS) in oxt6 was performed. The results demonstrated that in the absence of auxin the expression of ARF7 and ARF19 was found lower in fip1 compared to WT, which may be one of the reasons for less LRs in oxt6. However, in oxt6, there was a significantly greater increase in the expression of ARF7 and ARF19 when exogenous IAA was applied than that of WT. This further validates the role of CPSF30 in auxin regulation of LRs growth and development to a greater extent through ARF19 [134].

6.7. TCP20-NLPs Regulatory Module

The branched1/cycloidea/proliferating cell factor1-20 (TCP20) and NIN-like protein (NLP) NLP6 & NLP7, which functions to induce nitrate assimilatory genes, target the promoter upstream of nitrate reductase genes NIA1 [79,135]. TCP20-NLP6 and 7 heterodimers aggregate in the nucleus, and its overlaps mediate up-regulation of NO3− assimilation genes, and down-regulates G2/M cell-cycle marker gene CYCB1;1 [79]. In a likewise manner, TCP20-NLP6 & 7 supports root meristem development under N deficiency. This report elucidates mechanisms through which plants facilitate accessibility to nitrate responses, subsequently interconnecting NO3−-assimilation and signalling with cell-cycle progression [79]. It was revealed that Chrysanthemum morifolium TCP20 (CmTCP20) positively influence auxin accumulation in the LRs, partially by improving auxin biosynthesis, transport, and response, and thereby stimulating LRs growth [78].

6.8. Nitrate-Responsive OBP4-XTH9 Regulatory Module

Xyloglucan endotransglucosylases (XTHs) plays a crucial role in cell wall biosynthesis of group genes 1 XTHs gene, e.g., XTH1-11. XTH9 is highly expressed in the LRs primordial. Consistently, xth9 mutant shows fewer LRs compared to the OE XTH9 exhibits more LRs. This indicating the potential role of XTH9 in regulating LRs growth [122]. Genetic analysis revealed that this function of XTH9 depend on auxin-mediated ARF7/19 and the downstream AFB3 in response to nitrogen signals, stimulates the expression of XTH9 to enhance the LRs [122].

6.9. Nitrate Responsive NLP7 and NRT1.1 Module

It was reported by [136], that the expression of a transceptor NRT1.1 is modulated by NIN-like protein 7 (NLP7). Genetic and molecular analyses indicated that NLP7 functions as an upstream of NRT1.1 in the regulation of nitrate when NH4+ is present, while in absence of NH4+, it functions in nitrate signalling without being mediated by NRT1.1. However, in the nlp7 mutant, the expression of NRT1.1 initiates a partial or complete nitrate signalling [136]. More convincing evidence from ChiP and EMSA analyses indicated that NLP7 may bind to the particular region of the promoter of NRT1.1. Hence, NLP7 gene plays a significant role in NO3− signalling by regulating NRT1 [136].

7. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Recently, the system biology approach was established to distinguish the constituents and the crosstalk between nitrate and hormonal signal influenced by nitrate-signalling [137]. NO3− and IAA contribute to the cascade of events involved in the signal transduction towards the auxin-induced adventitious and LRs formation [138,139].

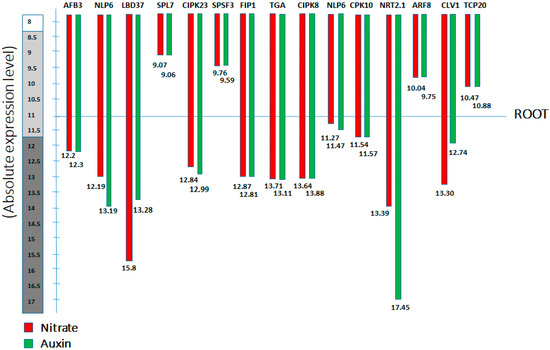

Several nitrate responsive genes involved in nitrate signalling promotes lateral root growth. And these genes are characterized in terms of nitrate regulatory genes, which build up signalling overlap between nitrate and auxin, and subsequently induce LR initiation, emergence, and development [50]. We distinguished these genes as short-term and long-term nitrate responsive transcription factors, highlighted their possible roles and also elucidate how they mediate auxin biosynthesis to initiate LRs in Arabidopsis at different nitrate levels (Figure 1) (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). To further demonstrate this signalling crosstalk, here, we have presented the absolute expression by collecting information from “Genevistigator database” (Table S1 and Figure 5), namely the Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 genome microarray analysis of root, which further presents each gene’s absolute expression in response to nitrate and auxin treatment respectively. Moreover, a refined set of genes was designated to be regulated by both nitrate (NO3−) and auxin signalling. We found that these genes have significantly higher levels of baseline expression to NO3− and auxin (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Unknown Affinity Nitrate Responsive Genes.

Figure 5.

Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 genome microarray analysis of the root; The schematic model represents the absolute expression level of the different nitrate transcription factors in the root of Arabidopsis, under nitrate (NO3−) and auxin treatment, the red bar represents the gene expression for nitrate treatment, while the green bar represents the expression level for auxin treatments. (See text for further detail).

Thus, our results demonstrate the identical regulation of these transcription factors for both nitrate and auxin treatments in the root of Arabidopsis thaliana. These discoveries lead to new speculation that nitrate plays a vital role in enhancing the effect of auxin signal. Additionally, cis-regulatory elements (CREs) in the promoters of these genes imply their role as candidates that might stimulate the NO3− regulated genes expression. This review highlights the ongoing innovation about the several regulatory modules controlling NO3− uptake and promoting root growth in response to mutual nitrate and auxin signalling in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

However, limited studies assessed the role of auxin in nitrate induced lateral root growth. There has been an outstanding achievement in our understanding of NO3− signalling pathways. With the schematic diagram, we have presented the nitrate mediated auxin biosynthesis regulates LRs growth. This regulation is via co-signalling induced by the primary nitrate transporter NPF6.3/NRT1.1 and its downstream TFs, including NIA1, NIA2, NiR, NR, and NRT2.1 (Figure 2), which mediate IAA biosynthesis induced lateral root growth (Figure 1). However, distinctive transcription factors such as CBL7, NLP7, TGA1/TGA4, TCP20, NRG2, RSA1, CLV1/CLE1, RSA1, NAC4/OBF4 (downstream of AFB3), SPL9, CLE/CLV1, LBDs, JR1, PHO1, DAAR2 are nitrate responsive, also may target NPF6.3/NRT1 and NRT2.1. However, how these transcription factors interact to build up a signalling module to regulate the LR root growth of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to nitrate is still questionable. Furthermore, some nitrate responsive genes are yet to be characterized and their interaction with auxin is yet unknown. However, they are the fundamental contributor genes in the regulation of LR development.

The NO3− and IAA signalling overlap in the Arabidopsis root system open up a huge research gap for each identified effect on root growth. Hence, the functional identification and characterization of various players associated with NO3− signalling pathways and their possible functional interaction with auxin in regulating LRs of Arabidopsis is the following step to comprehend the N responses in the plant. Moreover, it is also of much interest to uncover evidence to support the auxin signalling pathways that are self-regulated as they are involved in the feedback regulation of nitrate transport and assimilation to induce lateral root growth and development, which is fundamental to the field of crop biotechnology.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/8/2880/s1, Table S1. Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 Genome Microarray of Anatomical Part: Root.

Author Contributions

M.A. and Q.W. has jointly developed the conceptual structure of the manuscript. M.A. wrote the manuscript, including all the Tables and Figures. A.O. assisted in further modification of the manuscript. Z.U. corrected the grammatical mistakes and revised the manuscript. H.L. has provided critical feedback, revised, and approved it for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2017QC003), Science Foundation for Young Scholars of Tobacco Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2016B02), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP-TRIC02) and the Fundamental Research Funds for China Agricultural Academy of Sciences (1610232016005).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| RSA | Root system architecture |

| LBD | Lateral Organ Boundaries Domain |

| SPL | SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE |

| NIGT1 | NITRATE-INDUCABLE GRAP-TYPE TRANSCRIPTIONAL REPRESSOR1 |

| FIP1 | Factor interacting with poly (A) polymerase 1 |

| ARF | Auxin Response Factor |

| HNI9 | HIGH NITROGEN INSENSITIVE9 |

| NLP | NIN-like protein |

| TCP20 | The branched1/cycloidea/proliferating cell factor1-20 |

| XTH | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylases |

| JR1 | JOSMONATE RESPONSIVE 1 |

| DAAR2 | D AMINO ACID RACEMASE2 |

| HNI9/AtIWS1 | HIGH NITROGEN INSENSITIVE9 |

| PHO1 | PHOSPAHT TRANSPORTER 1 |

| RSA1 | ROOT SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE 1 |

| NRG2 | NITRATE REGULATORY GENE 2 |

| TIR1/AFB | TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE1/AUXIN SIGNALLING F-BOX |

| AUX/IAA | AUXIN/ INDLOE-3-ACETIC ACID |

| ARF | AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR |

| CPSF30-L | cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 30-L |

| SCFTIR/AFB | S-PHASE KINASE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 1-CULLIN-F-BOX PROTEIN (SCF)-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases |

| MeJA | Methyl jasmonate |

| EMSA | Electrophoretic mobility shift analysis |

References

- Gregory, P.J. Plant Roots: Growth, Activity, and Interaction with soils. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.J.; Kim, H.R.; Roy, S.K.; Kim, H.J.; Boo, H.O.; Woo, S.H.; Kim, H.H. Effects of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilizers on growth characteristics of two species of bellflower (platycodon grandiflorum). J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 22, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Z.; Amtmann, A. Food for thought: How nutrients regulate root system architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Dong, J.X.; Wang, S.S.; Song, K.; Ling, A.F.; Yang, J.G.; Xiao, Z.X.; Li, W.; Song, W.J.; Liang, H.B. Differential responses of root growth to nutrition with different ammonium/nitrate ratios involve auxin distribution in two tobacco cultivars. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 2703–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Glass, A.D.M.; Crawford, N.M. Ammonium inhibition of Arabidopsis root growth can be reversed by potassium and by auxin resistance mutations aux1, axr1, and axr2. Plant Physiol. 1993, 102, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Loqué, D.; Yuan, L.; Kojima, S.; Gojon, A.; Wirth, J.; Gazzarrini, S.; Ishiyama, K.; Takahashi, H.; Von Wirén, N. Additive contribution of AMT1;1 and AMT1;3 to high-affinity ammonium uptake across the plasma membrane of nitrogen-deficient Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 2006, 48, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, C.B.; Kranz, R.G. Reciprocal leaf and root expression of AtAmt1.1 and root architectural changes in response to nitrogen starvation. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Shen, Q.; Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M. Nitrogen form effects on yield and nitrogen uptake of rice crop grown in aerobic soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2004, 27, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J. Root architecture and plant productivity. Plant Physiol. 2010, 109, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.A.; Gutiérrez, R.A. A systems view of nitrogen nutrient and metabolite responses in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, V.; Bustos, R.; Irigoyen, M.L.; Cardona-López, X.; Rojas-Triana, M.; Paz-Ares, J. Plant hormones and nutrient signalling. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 69, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korasick, D.A.; Enders, T.A.; Strader, L.C. Auxin biosynthesis and storage forms. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2541–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.Q.; Wang, R.; Crawford, N.M. The Arabidopsis dual-affinity nitrate transporter gene AtNRT1.1 (CHL1) is regulated by auxin in both shoots and roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristova, D.; Carré, C.; Pervent, M.; Medici, A.; Kim, G.J.; Scalia, D.; Ruffel, S.; Birnbaum, K.D.; Lacombe, B.; Busch, W.; et al. Combinatorial interaction network of transcriptomic and phenotypic responses to nitrogen and hormones in the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walch-Liu, P.; Forde, B.G. Nitrate signalling mediated by the NRT1.1 nitrate transporter antagonises L-glutamate-induced changes in root architecture. Plant J. 2008, 54, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walch-Liu, P.; Ivanov, I.I.; Filleur, S.; Gan, Y.; Remans, T.; Forde, B.G. Nitrogen regulation of root branching. Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Wang, S. The relationship between nitrogen, auxin and cytokinin in the growth regulation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) tiller buds. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Dubos, C.; Huggins, D.; Grant, G.H.; Knight, M.R.; Campbell, M.M. A role for glycine in the gating of plant NMDA-like receptors. Plant J. 2003, 35, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzarrini, S.; Lejay, L.; Gojon, A.; Ninnemann, O.; Frommer, W.B.; Von Wirén, N. Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K. Nitrogen—Essential macronutrient and signal controlling. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 162, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Miller, A.J. Transporters responsible for the uptake and partitioning of nitrogenous solutes. Artic. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2001, 52, 659–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, N.; Niu, Q.; Ng, K.; Chua, N. The role of miR156 / SPLs modules in Arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant J. 2015, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-F.; Tian, Q.; Reed, J.W. Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development 2006, 133, 4211–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delay, C.; Imin, N.; Djordjevic, M.A. CEP genes regulate root and shoot development in response to environmental cues and are specific to seed plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5383–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Xu, C.; Xu, K.; Hu, Y. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN transcription factors direct callus formation in Arabidopsis regeneration. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, R.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Xu, N.; Chen, K.; Qi, S.; Zhang, M.; Tsay, Y.; et al. The Arabidopsis CPSF30-L gene plays an essential role in nitrate signalling and regulates the nitrate transceptor gene NRT1. New Phytol. 2017, 216, 1205–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, R.; Sumida, K.; Yoshii, T.; Ohyama, K.; Shinohara, H.; Matsubayashi, Y. Perception of root-derived peptides by shoot LRR-RKs mediates systemic N-demand signalling. Science 2014, 346, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Huang, I.C.; Liu, M.J.; Wang, Z.G.; Chung, S.S.; Hsieh, H.L. Glutathione S-transferase interacting with far-red insensitive 219 is involved in phytochrome A-mediated signalling in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Bi, Y.; Crawford, N.M.; Wang, Y. FIP1 plays an important role in nitrate signalling and regulates CIPK8 and CIPK23 expression in arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.-C.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Tsay, Y.-F. AtCIPK8, a CBL-interacting protein kinase, regulates the low-affinity phase of the primary nitrate response. Plant J. 2009, 57, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.; Riveras, E.; Vidal, E.A.; Gras, D.E.; Contreras-l, O.; Ruffel, S.; Lejay, L.; Jordana, X.; Guti, R.A.; Aceituno, F.; et al. Systems approach identifies TGA1 and TGA4 transcription factors as important regulatory components of the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiez, T.; El Kafafi, E.S.; Girin, T.; Berr, A.; Ruffel, S.; Krouk, G.; Vayssières, A.; Shen, W.H.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Gojon, A.; et al. High Nitrogen Insensitive 9 (HNI9)-mediated systemic repression of root NO3– uptake is associated with changes in histone methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13329–13334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, Y.H.; Pandey, G.K.; Grant, J.J.; Batistic, O.; Li, L.; Kim, B.G.; Lee, S.C.; Kudla, J.; Luan, S. Two calcineurin B-like calcium sensors, interacting with protein kinase CIPK23, regulate leaf transpiration and root potassium uptake in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 52, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ye, H.; Guo, H.; Yin, Y. Arabidopsis IWS1 interacts with transcription factor BES1 and is involved in plant steroid hormone brassinosteroid regulated gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 3918–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.-M.; Sun, C.-H.; Wen, L.-Z.; Liu, B.-W.; Ren, H.; Sun, X.; Ma, F.-F.; Zheng, C.-S. CmTCP20 plays a key role in nitrate and auxin signalling-regulated lateral root development in chrysanthemum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, A.N.; Robertson-Hoyt, J.; Yun, J.; Benavente, L.M.; Xie, D.Y.; Doležal, K.; Schlereth, A.; Jürgens, G.; Alonso, J.M. TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 2008, 133, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.A.; Álvarez, J.M.; Moyano, T.C.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Transcriptional networks in the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 27, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wang, R.; Chen, M.; Crawford, N.M. The Arabidopsis dual-affinity nitrate transporter gene AtNRT1.1 (CHL1) is activated and functions in nascent organ development during vegetative and reproductive growth. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, J.; Contreras-l, O.; Guti, R.A. Nitrate induction of root hair density is mediated by TGA1 / TGA4 and CPC transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2017, 92, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G.; Lacombe, B.; Bielach, A.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Malinska, K.; Mounier, E.; Hoyerova, K.; Tillard, P.; Leon, S.; Ljung, K.; et al. Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounier, E.; Pervent, M.; Ljung, K.; Gojon, A.; Nacry, P. Auxin-mediated nitrate signalling by NRT1.1 participates in the adaptive response of Arabidopsis root architecture to the spatial heterogeneity of nitrate availability. Plant. Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, M.L.; Dean, A.; Gutierrez, R.A.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Birnbaum, K.D. Cell-specific nitrogen responses mediate developmental plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, F.; Crawford, N.M.; Wang, Y. Molecular regulation of nitrate responses in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friml, J.; Vieten, A.; Sauer, M.; Weijers, D.; Schwarz, H.; Hamann, T.; Offringa, R.; Jürgens, G. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 2003, 426, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.L.; Ishida, T.; Sawa, S. CLE peptides and their signalling pathways in plant development. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4813–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Ryu, H.; Rho, S.; Hill, K.; Smith, S.; Audenaert, D.; Park, J.; Han, S.; Beeckman, T.; Bennett, M.J.; et al. A secreted peptide acts on BIN2-mediated phosphorylation of ARFs to potentiate auxin response during lateral root development. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, I.; Zhang, Y.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Pisanty, O.; Barbosa, I.C.R.; Zourelidou, M.; Regnault, T.; Crocoll, C.; Olsen, C.E.; Weinstain, R.; et al. The Arabidopsis NPF3 protein is a GA transporter. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.C.; Qin, G.J.; Tsuge, T.; Hou, X.H.; Ding, M.Y.; Aoyama, T.; Oka, A.; Chen, Z.; Gu, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. SPOROCYTELESS modulates YUCCA expression to regulate the development of lateral organs in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.A.; Moyano, T.C.; Riveras, E.; Contreras-López, O.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Systems approaches map regulatory networks downstream of the auxin receptor AFB3 in the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12840–12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Hu, D.G. Nitrate: A crucial signal during lateral roots development. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, S.; Friml, J. Auxin: A trigger for change in plant development. Cell 2009, 136, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T. Auxin-responsive gene expression: Genes, promoters and regulatory factors. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002, 49, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Yu, M.; Su, B.; Gong, W.; Baluška, F.; Komis, G.; Šamaj, J.; Shan, X.; Lin, J. Phosphorylation-mediated dynamics of nitrate transceptor NRT1.1 regulate auxin flux and nitrate signalling in lateral root growth. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remans, T.; Nacry, P.; Pervent, M.; Filleur, S.; Diatloff, E.; Mounier, E.; Tillard, P.; Forde, B.G.; Gojon, A. The Arabidopsis NRT1.1 transporter participates in the signalling pathway triggering root colonization of nitrate-rich patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19206–19211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmailov, S.F.; Nikitin, A.V.; Rodionov, V.A. Nitrate Signalling in Plants: Introduction to the Problem. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 65, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G.; Mirowski, P.; Lecun, Y.; Shasha, D.E.; Coruzzi, G.M. Predictive network modeling of the high- resolution dynamic plant transcriptome in response to nitrate. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, M.L.; Banta, J.A.; Katari, M.S.; Hulsmans, J.; Chen, L.; Ristova, D.; Tranchina, D.; Purugganan, M.D.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Birnbaum, K.D. Plasticity regulators modulate specific root traits in discrete nitrogen environments. Plos Genet. 2013, 9, 1003760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y.; Konishi, M.; Yanagisawa, S. Molecular basis of the nitrogen response in plants. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 63, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Du, X.; Cui, X. Effects of three auxin-inducible LBD members on lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2012, 236, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, J. EXPANSINA17 Up-Regulated by LBD18/ASL20 promotes lateral root formation during the auxin response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, G.; Tohge, T.; Matsuda, F.; Saito, K.; Scheible, W.-R. Members of the LBD family of transcription factors repress anthocyanin synthesis and affect additional nitrogen responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3567–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, N.Y.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, J. LBD18/ASL20 regulates lateral root formation in combination with LBD16/ASL18 downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Czech, B.; Weigel, D. miR156-Regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 2009, 138, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tang, R.; Zheng, X.; Wang, S.; Luan, S. The calcium sensor CBL7 modulates plant responses to low nitrate in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, A.; Marshall-Colon, A.; Ronzier, E.; Szponarski, W.; Wang, R.; Gojon, A.; Crawford, N.M.; Ruffel, S.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Krouk, G. AtNIGT1/HRS1 integrates nitrate and phosphate signals at the Arabidopsis root tip. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Konishi, M.; Kiba, T.; Sakuraba, Y.; Sawaki, N.; Kurai, T.; Ueda, Y.; Sakakibara, H.; Yanagisawa, S. A NIGT1-centred transcriptional cascade regulates nitrate signalling and incorporates phosphorus starvation signals in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-H.; Niu, Y.; Konishi, M.; Wu, Y.; Du, H.; Sun Chung, H.; Li, L.; Boudsocq, M.; McCormack, M.; Maekawa, S.; et al. Discovery of nitrate-CPK-NLP signalling in central nutrient-growth networks. Nature 2017, 545, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Li, S.; Asim, M.; Mao, J.; Xu, D.; Ullah, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H. The Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) and their roles in plant growth regulation and abiotic stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, R.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Lei, Z.; Liu, F.; Guan, P.; Chu, Z.; Crawford, N.M.; et al. The Arabidopsis NRG2 protein mediates nitrate signalling and interacts with and regulates key nitrate regulators. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.L.; Okamoto, H.; Wang, M.; Ang, L.H.; Matsui, M.; Goodman, H.; Deng, X.W. FIN219, an auxin-regulated gene, defines a link between phytochrome A and the downstream regulator COP1 in light control of Arabidopsis development. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Xu, R.; Merrill, C.; Hong, L.; Von Lanken, C.; Hunt, A.G.; Li, Q.Q. Integration of developmental and environmental signals via a polyadenylation factor in arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, H.D.; Chen, L.Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.L.; He, L.; Wu, W.H. A Protein Kinase, Interacting with Two Calcineurin B-like Proteins, Regulates K + Transporter AKT1 in Arabidopsis. Cell 2006, 125, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitford, R.; Fernandez, A.; De Groodt, R.; Ortega, E.; Hilson, P. Plant CLE peptides from two distinct functional classes synergistically induce division of vascular cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18625–18630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Li, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, C. A novel morphological response of maize (Zea mays) adult roots to heterogeneous nitrate supply revealed by a split-root experiment. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 150, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y.; Filleur, S.; Rahman, A.; Gotensparre, S.; Forde, B.G. Nutritional regulation of ANR1 and other root-expressed MADS-box genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2005, 222, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsel, M.; Krapp, A.; Daniel-Vedele, F. Analysis of the NRT2 nitrate transporter family in Arabidopsis. Structure and gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Wang, R.; Nacry, P.; Breton, G.; Kay, S.A.; Pruneda-paz, J.L.; Davani, A. Nitrate foraging by Arabidopsis roots is mediated by the transcription factor TCP20 through the systemic signalling pathway. PNAS 2014, 111, 15267–15272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.A.; Araus, V.; Lu, C.; Parry, G.; Green, P.J.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Nitrate-responsive miR393/AFB3 regulatory module controls root system architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4477–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohyama, K.; Ogawa, M.; Matsubayashi, Y. Identification of a biologically active, small, secreted peptide in Arabidopsis by in silico gene screening, followed by LC-MS-based structure analysis. Plant J. 2008, 55, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkubo, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tabata, R.; Ogawa-Ohnishi, M.; Matsubayashi, Y. Shoot-to-root mobile polypeptides involved in systemic regulation of nitrogen acquisition. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, U.; Cibrian-Jaramillo, A.; Ristova, D.; Banta, J.A.; Gifford, M.L.; Fan, A.H.; Zhou, R.W.; Kim, G.J.; Krouk, G.; Birnbaum, K.D.; et al. Integration of responses within and across Arabidopsis natural accessions uncovers loci controlling root systems architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15133–15138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Nakanomyo, I.; Motose, H.; Iwamoto, K.; Sawa, S.; Dohmae, N.; Fukuda, H. Dodeca-CLE as peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science 2006, 313, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Dai, X.; De-Paoli, H.; Cheng, Y.; Takebayashi, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Zhao, Y. Auxin overproduction in shoots cannot rescue auxin deficiencies in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, J.; Qu, B.; He, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.; Fu, X.; Tong, Y. Auxin biosynthetic gene TAR2 is involved in low nitrogen-mediated reprogramming of root architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2014, 78, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.Y.; Sun, P.; Zhang, W.H. Ethylene is involved in nitrate-dependent root growth and branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 184, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undurraga, S.F.; Ibarra-Henríquez, C.; Fredes, I.; Álvarez, J.M.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Nitrate signalling and early responses in Arabidopsis roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overvoorde, P.; Fukaki, H.; Beeckman, T. Auxin control of root development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P. Dancing with hormones: A current perspective of nitrate signalling and regulation in arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Ferrer, J.-L.; Ljung, K.; Pojer, F.; Hong, F.; Long, J.A.; Li, L.; Moreno, J.E.; Bowman, M.E.; Ivans, L.J.; et al. Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell 2008, 133, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, M.; Yanagisawa, S. A central role in nitrate signalling. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1617–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchive, C.; Roudier, F.; Castaings, L.; Bréhaut, V.; Blondet, E.; Colot, V.; Meyer, C.; Krapp, A. Nuclear retention of the transcription factor NLP7 orchestrates the early response to nitrate in plants. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krouk, G. Hormones and nitrate: A two-way connection. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 91, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Para, A.; Li, Y.; Marshall-colón, A.; Varala, K.; Francoeur, N.J.; Moran, T.M. Hit-and-run transcriptional control by bZIP1 mediates rapid nutrient signalling in Arabidopsis. PNAS 2014, 111, 10371–10376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaings, L.; Camargo, A.; Pocholle, D.; Gaudon, V.; Texier, Y.; Boutet-Mercey, S.; Taconnat, L.; Renou, J.P.; Daniel-Vedele, F.; Fernandez, E.; et al. The nodule inception-like protein 7 modulates nitrate sensing and metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009, 57, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Forde, B.G. Regulation of Arabidopsis root development by nitrate availability. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouk, G.; Crawford, N.M.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Tsay, Y.-F. Nitrate signalling: Adaptation to fluctuating environments. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]