Abstract

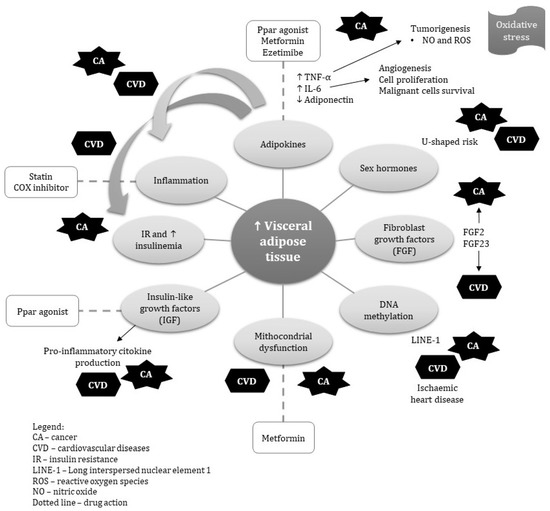

The association between obesity, cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been demonstrated in animal and epidemiological studies. However, the specific role of visceral obesity on cancer and CVD remains unclear. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is a complex and metabolically active tissue, that can produce different adipokines and hormones, responsible for endocrine-metabolic comorbidities. This review explores the potential mechanisms related to VAT that may also be involved in cancer and CVD. In addition, we discuss the shared pharmacological treatments which may reduce the risk of both diseases. This review highlights that chronic inflammation, molecular aspects, metabolic syndrome, secretion of hormones and adiponectin associated to VAT may have synergistic effects and should be further studied in relation to cancer and CVD. Reductions in abdominal and visceral adiposity improve insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and cytokines, which consequently reduce the risk of CVD and some cancers. Several medications have shown to reduce visceral and/or subcutaneous fat. Further research is needed to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms by which visceral obesity may cause both cancer and CVD. The role of visceral fat in cancer and CVD is an important area to advance. Public health policies to increase public awareness about VAT’s role and ways to manage or prevent it are needed.

1. Introduction

Visceral obesity is a type of body fat deposition in the upper part of the body and within the abdominal cavity. This adipose tissue is located near several organs, such as the liver, stomach and intestines and it can build up in the arteries. Visceral fat is sometimes known as “active fat” because it can actively increase the risk of adverse health problems. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is a complex and metabolically active tissue, which can produce different adipokines and hormones responsible for endocrine-metabolic comorbidities. It is associated with increased adipocytokine production, proinflammatory activity and altered blood lipids levels as well as with decreased HDL cholesterol [1].

There is growing consensus that visceral obesity represents an important risk factor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and different types of cancers [2,3,4,5] such as esophagus, pancreas, colorectum, breast, endometrium, kidney and prostate [6,7]. A growing body of evidence suggests an overlap of the epidemiological risk factors of both CVD and cancer [5,8]. In fact, the association between obesity, cancer and CVD has been established in a multitude of animal and epidemiological studies [5,8]. Research on this topic is now focusing on the role of VAT on carcinogenesis and development of CVD, which may involve alterations in immunological, metabolic and endocrinal pathways.

Therefore, this review aims to highlight the potential shared disease pathways linking visceral obesity to cancer and CVD. In addition, we discuss the shared pharmacological treatments that may mitigate the risk of both conditions.

3. Pharmacological Treatment of Visceral Obesity

The development of pharmacological agents to reduce visceral obesity is difficult due to various potential side effects [100]. For example, regulatory authorities in visceral obesity and weight loss had approved dexfenfluramine, sibutramine, and rimonabant. However, they were removed from clinical use because of their various side effects. In this section, we introduce the clinical and experimental drugs that can probably reduce visceral fat that affects the risk of cancer and CVD. The summary of the effects from pharm therapy on cancer and CVD is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Drugs for joint pharmacologic prevention of visceral obesity, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

3.1. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ)

This ligand-activated transcription factor has critical roles in various cellular functions and glucose and lipid metabolism [101]. PPARγ is found in abundance in the adipose tissue where this receptor acts as a lipid sensor. The activation of PPARγ (by its ligands) leads to adipokine secretion [102] which reduces visceral fat, but not necessarily body weight. It has been suggested that pioglitazone (PPARγ agonists) decreases visceral fat, however, it may increase total body weight [103]. PPARγ agonists have cardiovascular protective effects, but some adverse cardiovascular events such as congestive heart failure and myocardial infarction have been detected with these drugs. For example, pioglitazone showed a reduction in the risk of MI (miocard infarction), stroke or death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [104] in a recent meta-analysis. However, another meta-analysis showed that rosiglitazone increased the risk of MI but with low mortality risk [105].

PPAR-γ agonists decrease tumor proliferation by lowering circulating insulin and affecting key pathways of the Insulin/IGF axis, such as PI3K/mTOR, MAPK, and GSK3-β/Wnt/β-catenin cascades, which regulate cancer cell survival, cell reprogramming, and differentiation [106]. One meta-analysis supported a protective association between PPAR-γ agonists’ use and reduction of colon cancer risk in patients with DM [107]. On the other hand, in human studies, it has been shown that Pioglitazone can increase the risk of bladder cancer in humans [108] depending on its dosage. While Pioglitazone decreases the risk of breast cancer. The other PPAR agonist, rosiglitazone, decreased [109] the risk of bowel cancer significantly. Therefore, the effect on cancer may be site and drug specific.

3.2. Growth Hormone Treatment

Growth hormone (GH) treatment is not effective in treating visceral obesity in patients with normal levels but its deficiency leads to obesity or visceral obesity [110]. It has been suggested that GH therapy decreases visceral adiposity and improves lipid profile in adults with obesity [111]. This effect results from GH lipolysis properties [112]. However, IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels are more related to visceral adipose tissue accumulation than overall adiposity [113].

Recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) has been widely used to treat children with short stature secondary to any medical problems. The experience from many thousands of patients and years of treatment demonstrates a good safety record for rhGH. Nevertheless, the findings from a meta-analysis showed a significant increase in all-cause mortality but no significant increase in the malignancy and CVD mortality. The risk for second neoplasms increases in these patients [114].

A recent meta-analysis evaluated the risk of cancer in adults with and without growth hormone replacement therapy, which suggested that growth hormone replacement therapy could reduce the risk of cancer in adults with growth hormone deficiency [115].

3.3. Metformin

Metformin, a biguanide anti-hyperglycemic agent, is the first line treatment for overweight diabetes patients [116]. It reduces liver glucose production, increases cells insulin sensitivity and induces anorexia effect [117]. Metformin treatment up-regulates adipose oxidation-related enzymes in the liver and also UCP-1 in the brown adipose tissue which leads to reductions in abdominal obesity in mice [118]. In addition, metformin can reduce visceral adiposity by upregulating adaptive thermogenesis [119].

Metformin has protective effects on cardiovascular problems in patients with type 2 diabetes which are independent from the glucose-lowering effect [120]. Metformin activates AMPK promoting glycolysis. Metformin also increases eNOS production, which results in beneficial effects in patients with heart failure [121]. Metformin attenuated ER stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in myocardial cells, which results in reduction of cardiac injury through ER-stress [122].

Metformin increases glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity and reduces serum insulin level which results in reduction of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic cell proliferation [123]. Metformin also reduces circulating levels of androgen and estrogen, which is another potential mechanism of metformin in the prevention of cancer incidence [124]. Metformin inhibits mTOR activity and activates p53 which reduces the cell cycle. Metformin reduces mortality risk and recurrence of cancers in clinical studies and also sensitizes cancer cells to chemo and radiotherapy [123]. The most recent meta-analysis confirms the association between metformin use and reduction of pancreatic and colorectal cancer incidence [63,125].

3.4. Cycloxyganase Inhibitors

Elevated levels of cyclooxygenase (COX), a sign of chronic inflammation, is the key connection between cancer and obesity. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce inflammation via COX inhibition which ultimately reduces prostaglandin levels [126]. They also have a different effect on visceral obesity and adipose reduction [127].

The results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses show that there is a significant increase in risk of heart attack in patients who are taking COX inhibitors compared with placebo [128]. The possible mechanisms are due to the fact that prostacyclin reductions lead to platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction [129]. Cancer cells and tissues upregulate the expression of COX which is inversely associated with cancer incidence and recurrence [130]. It has been confirmed that COX inhibitors can reduce the risk of breast cancer in women [131]. However, because of adverse cardiovascular effects, they are not currently prescribed for prevention of cancer risk and recurrence.

Aspirin, an irreversible inhibitor of the COX enzyme [132], is an exception, which has protective effects on the cardiovascular system. It has been confirmed that low-dose aspirin use may reduce the risk of cancer. These observations coincide with recent in vivo and clinical studies showing a functional relationship between platelets and tumors, suggesting that aspirin’s chemo preventive properties may result, in part, from direct modulation of platelet biology and biochemistry [133].

3.5. Statins

Statins, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, are the most common lipid-lowering medications and are widely prescribed. They are effective in lowering cholesterol and play a critical role in the prevention of primary and secondary cardiovascular disease [134]. Statins also decrease chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, which is another possible mechanism in preventing cardiovascular disease [135]. It seems that some types of statins, such as pitavastatin may increase circulating adiponectin. However, data are conflicting [136]. A recent study confirmed that atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (two other statins) reduce epicardial adipose tissue in post-menopausal women independent of their lipid-lowering property [137]. However, it seems that different types of statins may have different effects.

There are several meta-analyses on the effect of statins and cancer incidence and also relapse with some showing beneficial effects while others found no effects. A risk reduction has been observed in esophageal [138], colorectal [139] and gastric cancer [140]. It seems that they may reduce the risk of mortality from cancer too [141,142].

3.6. Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe is another lipid-lowering drug which limits the absorption of cholesterol from the gastrointestinal tract epithelial. It blocks the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) protein on small intestine epithelial cells, which leads to reduction of plasma level of cholesterol [143].

There is some evidence suggesting that ezetimibe has an effect on adiponectin and decreases insulin resistance which results in adipose tissue reduction in patients with metabolic syndrome [144]. Adding ezetimibe to statin therapy is associated with a greater reduction in blood level of TNF-α in patients with hyperlipidemia [145].

Ezetimibe in combination with statin, has beneficial effects on the risk reduction of non-fatal MI. However, there is limited evidence about its monotherapy and CVD risk reduction [146]. It has been shown that ezetimibe could suppress inflammation and liver tumor growth in animal models of a high fat diet. It seems that inhibiting angiogenesis in mice leads to tumor suppression [147]. However, cholesterol lowering by ezetimibe did not slow prostate tumor growth and may induce expression of LDL receptor in cancer cells [148].

4. Conclusions

In this review, we discussed some pathophysiological aspects shared between VAT, cardiovascular disease and cancer as well as their shared pharmacological prevention. Chronic inflammation and dysregulated metabolism associated to visceral obesity, such as insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia can affect both CVD and cancer development and progression. The shared disease pathways linking visceral obesity to cancer and CVD may offer valuable opportunities for public health interventions to tackle both diseases. Reductions in abdominal and visceral adiposity improve insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and cytokines, which consequently reduce the risk of CVD and some cancer types. In fact, in addition to lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy with antidiabetic drugs, PPARγ and recombinant growth hormone may decrease the risk of both visceral obesity and cancer. Several medications have been shown to reduce visceral and/or subcutaneous fat. However, none of them have been approved for use in this context. Further research on the shared pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between visceral obesity, CVD and cancer could potentially lead to the discovery of important biomarkers and pathways and development and assessment of effective therapies. New pharmacological treatments that selectively affect the shared pathways, are needed. Long term, well designed RCTs and cohort studies should be conducted to test the hypothesis of targeting shared mechanisms aiming to prevent VAT, cancer and CVD. The role of visceral fat in cancer and CVD is an important area to advance in public health policies. It is also important to increase public awareness about its role and ways to manage or prevent it.

Author Contributions

E.A.S. was responsible for writing the draft of the manuscript and performing major revisions of the manuscript, G.V. and A.S.d.C.S. developed the figure and wrote some parts. A.S.d.C.S., F.M., M.N., N.M., C.d.O., edited the whole manuscript and wrote some parts. N.K. wrote some parts and critically revised the manuscript. N.S. and E.A.S. developed the idea, wrote some parts, edited the whole manuscript and supervised the whole project. C.d.O. edited the whole manuscript and critically revised. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Cesar de Oliveira is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (Grant ES/T008822/11).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the Universidade Federal se Goias (UFG) and the Instituto Federal Goiano as well as Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute for the Technical assistance and support. Cesar de Oliveira is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant ES/T008822/1).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

Where authors are identified as personnel or advisors of the International Agency for Research on Cancer or the World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of their affiliated agencies.

References

- Tchernof, A.; Després, J.-P. Pathophysiology of Human Visceral Obesity: An Update. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 359–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, H.; Khan, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Usman, M.S.; Shah, N.; Goyal, A.; Khan, S.; Mookadam, F.; Krasushi, R.A.; Ahmed, H. Association Between Obesity and Cardiovascular Outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e183788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberio, A.M.; Alareeki, A.; Viner, B.; Pader, J.; Vena, J.E.; Arora, P.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Brenner, D.R. Central body fatness is a stronger predictor of cancer risk than overall body size. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, E.A.; Ferreira, C.C.D.C.; Pagotto, V.; Santos, A.S.E.A.D.C.; Velasquez-Melendez, G. Total and central obesity in elderly associated with a marker of undernutrition in early life—Sitting height-to-stature ratio: A nutritional paradox. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2017, 29, e22977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, E.A.; Kliemann, N.; Noll, M.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Oliveira, C. Visceral obesity and incident cancer and cardiovascular disease: An integrative review of the epidemiological evidence. Obes. Rev. 2020, 1, obr.13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fund, W.C.R. Body Fatness and Weight Gain and the Risk of Cancer. American Institute for Cancer Research, 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Body-fatness-and-weight-gain_0.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Doyle, S.L.; Donohoe, C.L.; Lysaght, J.; Reynolds, J.V. Visceral obesity, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and cancer. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.C.P. Link between obesity and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8753–8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Lyon, C.J.; Bergin, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Hsueh, W.A. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2016, 11, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; Bodzin, J.L.; Saltiel, A.R. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Candales, A.; Hernández Burgos, P.M.; Hernandez-Suarez, D.F.; Harris, D. Linking Chronic Inflammation with Cardiovascular Disease: From Normal Aging to the Metabolic Syndrome. J. Nat. Sci. 2017, 3, e341. [Google Scholar]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.V.; Cobucci, R.N.O.; Jatobá, C.A.N.; de Medeiros Fernandes, T.A.A.; de Azevedo, J.W.V.; de Araújo, J.M.G. The Role of the Mediators of Inflammation in Cancer Development. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2015, 21, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudkabir, F.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Gotay, C.; Ignaszewski, A.; Krahn, A.D.; Davis, M.K.; Franco, C.; Mani, A. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: Evidence for shared disease pathways and pharmacologic prevention. Atherosclerosis 2017, 263, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multhoff, G.; Molls, M.; Radons, J. Chronic Inflammation in Cancer Development. Front. Immunol. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. Inflammation, a Key Event in Cancer Development. Mol. Cancer Res. 2006, 4, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, L.L. Cancer and inflammation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2017, 9, e1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, J.; Evers, N.; Awazawa, M.; Nicholls, H.T.; Bronneke, H.S.; Dietrich, A.; Mauer, J.; Bluher, M.; Bruning, J.C. Obesogenic memory can confer long-term increases in adipose tissue but not liver inflammation and insulin resistance after weight loss. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Zatterale, F.; Naderi, J.; Parrillo, L.; Formisano, P.; Raciti, G.A.; Beguinot, F.; Miele, C. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancello, R.; Henegar, C.; Viguerie, N.; Taleb, S.; Poitou, C.; Rouault, C.; Coupaye, M.; Pelloux, V.; Hugol, D.; Bouillot, J.-L.; et al. Reduction of Macrophage Infiltration and Chemoattractant Gene Expression Changes in White Adipose Tissue of Morbidly Obese Subjects After Surgery-Induced Weight Loss. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lam, K.S.L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Lam, M.C.; Shen, J.; Wong, L.; Hoo, R.L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, A. Hypoxia dysregulates the production of adiponectin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 independent of reactive oxygen species in adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 341, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wueest, S.; Rapold, R.A.; Rytka, J.M.; Schoenle, E.J.; Konrad, D. Basal lipolysis, not the degree of insulin resistance, differentiates large from small isolated adipocytes in high-fat fed mice. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoldi, A.; Naffah de Souza, C.; Câmara, N.O.S.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M. The Macrophage Switch in Obesity Development. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loffek, S.; Schilling, O.; Franzke, C.-W. Biological role of matrix metalloproteinases: A critical balance. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, L. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Inflammation/Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer. Immunogastroenterology 2013, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-J.; Li, H.-X.; Luo, X.-T.; Lu, R.-Z.; Ma, Y.-F.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.-Q.; Yu, H.; Liu, J. STAT3 activation in tumor cell-free lymph nodes predicts a poor prognosis for gastric cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porporato, P.E.; Filigheddu, N.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cell. Res. 2018, 28, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.J.; Ma, W.; Starost, M.F.; Lago, C.U.; Lim, P.K.; Sack, M.N.; Kang, J.-G.; Wang, P.-Y.; Hwang, P.M. Ambient Oxygen Promotes Tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.-Y.; Döppler, H.; DelGiorno, K.E.; Zhang, L.; Leitges, M.; Crawford, H.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Storz, P. Mutant KRas-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Acinar Cells Upregulates EGFR Signaling to Drive Formation of Pancreatic Precancerous Lesions. Cell. Rep. 2016, 14, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Luo, N.; Klein, R.L.; Garvey, W.T. Adiponectin promotes adipocyte differentiation, insulin sensitivity, and lipid accumulation. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 46, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Cheng, K.K.Y.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Lam, K.S.L.; Xu, A. Vascular effects of adiponectin: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic intervention. Clin. Sci. 2008, 114, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Siddharth, S.; Sharma, D. Adiponectin, Obesity, and Cancer: Clash of the Bigwigs in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muppala, S.; Konduru, S.K.; Merchant, N.; Ramsoondar, J.; Rampersad, C.K.; Rajitha, B.; Mukund, V.; Kancherla, J.; Hammond, A.; Barik, T.K.; et al. Adiponectin, Its role in obesity-associated colon and prostate cancers. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 116, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalamaga, M.; Diakopoulos, K.N.; Mantzoros, C.S. The Role of Adiponectin in Cancer: A Review of Current Evidence. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 547–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez, J.; Iglesias, P. The role of the novel adipocyte-derived hormone adiponectin in human disease. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2003, 148, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedvídková, J.; Smitka, K.; Kopský, V.H.V. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived protein. Physiol. Res. 2005, 54, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S.; Arefhosseini, S.R.; Ebrahimi-Mamaeghani, M.; Fallah, P.; Bazi, Z. Adiponectin as a potential biomarker of vascular disease. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhai, D.A.; Kranendonk, M.E.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; van der Graaf, Y.; Kappelle, L.J.; Visseren, F.L.J. Adiponectin and incident coronary heart disease and stroke. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Ohishi, M.; Kihara, S.; Funahashi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Nagaretani, H.; Kumada, M.; Ohashi, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Nishizawa, H.; et al. Association of Hypoadiponectinemia With Impaired Vasoreactivity. Hypertension 2003, 42, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, N.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J. Adiponectin induces growth inhibition and apoptosis in cervical cancer HeLa cells. Biologia (Bratisl) 2011, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelsomino, L.; Naimo, G.D.; Catalano, S.; Mauro, L.; Andò, S. The Emerging Role of Adiponectin in Female Malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, L.; Naimo, G.D.; Gelsomino, L.; Malivindi, R.; Bruno, L.; Pellegrino, M.; Tarallo, R.; Memoli, D.; Weisz, A.; Panno, M.S.; et al. Uncoupling effects of estrogen receptor α on LKB1/AMPK interaction upon adiponectin exposure in breast cancer. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 4343–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, L.; Pellegrino, M.; Giordano, F.; Ricchio, E.; Rizza, P.; De Amicis, F.; Catalano, S.; Bonofiglio, D.; Panno, M.L.; Andò, S. Estrogen receptor-α drives adiponectin effects on cyclin D1 expression in breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2150–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbaschian, Z.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Giahi, L.; Golpaie, A.; Masoudkabir, F.; Talebpour, M.; Kosari, F.; Karbaschian, N.; Hoseini, M.; Mazaherioun, M. Portal and systemic levels of visfatin in morbidly obese subjects undergoing bariatric surgery. Endocrine 2013, 44, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, H.; Soltani, D.; Sobh-Rakhshankhah, A.; Jafari, S.; Boroumand, M.A.; Goudarzi, V.; Vasheghani-Farahani, A.; Masoudkabir, F. Visfatin as marker of isolated coronary artery ectasia and its severity. Cytokine 2019, 113, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landecho, M.F.; Tuero, C.; Valentí, V.; Bilbao, I.; de la Higuera, M.; Frühbeck, G. Relevance of Leptin and Other Adipokines in Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Risk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romacho, T.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F.; Peiró, C. Visfatin/Nampt: An Adipokine with Cardiovascular Impact. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romacho, T.; Valencia, I.; Ramos-González, M.; Vallejo, S.; López-Esteban, M.; Lorenzo, O.; Cannata, P.; Romero, A.; San Hipólito-Luengo, A.; Gómez-Cerezo, J.F.; et al. Visfatin/eNampt induces endothelial dysfunction in vivo: A role for Toll-Like Receptor 4 and NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, T.-Y.; Guan, Y.-F.; Su, D.-F.; Fan, G.-R.; Miao, C.-Y. Perivascular adipose tissue-derived visfatin is a vascular smooth muscle cell growth factor: Role of nicotinamide mononucleotide. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 81, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-R.; Bae, Y.-H.; Bae, S.-K.; Choi, K.-S.; Yoon, K.-H.; Koo, T.H.; Jang, H.-O.; Yun, I.; Kim, K.-W.; Kwon, Y.-G.; et al. Visfatin enhances ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression through ROS-dependent NF-κB activation in endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 2008, 1783, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C. The role of visfatin in cancer proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis, drug resistance and clinical prognosis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3481–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Li, L. The NAMPT/E2F2/SIRT1 axis promotes proliferation and inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Teng, F.; Tian, W.; Yang, W.; Yan, Y.; Xue, F. Visfatin stimulates endometrial cancer cell proliferation via activation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK1/2 signalling pathways. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-W.; Kim, W.-H.; Shin, S.-H.; Kim, J.Y.; Yun, M.R.; Park, K.J.; Park, H.-Y. Visfatin exerts angiogenic effects on human umbilical vein endothelial cells through the mTOR signaling pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 2011, 1813, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, Y.-H.; Park, H.-J.; Kim, S.-R.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kang, Y.; Kim, J.-A.; Wee, H.-J.; Kageyama, R.; Jung, J.S.; Bae, M.-K.; et al. Notch1 mediates visfatin-induced FGF-2 up-regulation and endothelial angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 89, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, G.C.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Ho, G.Y.; Going, S.B.; Beebe-Dimmer, J.; Manson, J.E.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Rohan, T. Metabolic Obesity Phenotypes and Risk of Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2017, 26, 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Margolis, K.L.; Hendryx, M.; Rohan, T.E.; Groessl, E.J.; Thomson, C.A.; Kroenke, C.H.; Simon, M.S.; Lane, D.; Stefanick, M.; et al. Metabolic Phenotype and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Normal-Weight Postmenopausal Women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.S.; McDaniel, M.L. Identifying the links between obesity, insulin resistance and beta-cell function: Potential role of adipocyte-derived cytokines in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 32, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayn, K.N. Visceral fat and insulin resistance—Causative or correlative? Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, S71–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneni, F.; Costantino, S.; Cosentino, F. Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2014, 16, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, C.L.; Doyle, S.L.; Reynolds, J.V. Visceral adiposity, insulin resistance and cancer risk. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2011, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; LeRoith, D. Minireview: IGF, Insulin, and Cancer. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 2546–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourian, M.; Karimi, R.; Vaseghi, G. Different effects of metformin and insulin on primary and secondary chemoprevention of colorectal adenoma in diabetes type 2: Traditional and Bayesian meta-analysis. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lukanova, A.; Söderberg, S.; Stattin, P.; Palmqvist, R.; Lundin, E.; Biessy, C.; Rinaldi, S.; Riboli, E.; Hallmans, G.; Kaaks, R. Nonlinear relationship of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-I/IGF-binding protein-3 ratio with indices of adiposity and plasma insulin concentrations (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 2002, 13, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncoso, R.; Ibarra, C.; Vicencio, J.M.; Jaimovich, E.; Lavandero, S. New insights into IGF-1 signaling in the heart. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgers, A.M.G.; Biermasz, N.R.; Schoones, J.W.; Pereira, A.M.; Renehan, A.G.; Zwahlen, M.; Egger, M.; Dekkers, O.M. Meta-analysis and dose-response metaregression: Circulating insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 2912–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, H.; Yu, H.; Fan, L. Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Level and Ovarian Cancer Risk. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.G.; Hudis, C.A.; Giri, D.; Morrow, M.; Falcone, D.J.; Zhou, X.K.; Du, B.; Brogi, E.; Crawford, C.B.; Kopelovich, L.; et al. Inflammation and Increased Aromatase Expression Occur in the Breast Tissue of Obese Women with Breast Cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Yu, H.; McLarty, J.; Glass, J. IGF-I and breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 111, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J.; Carlzon, D.; Petzold, M.; Karlsson, M.K.; Ljunggren, Ö.; Tivesten, Å.; Mellström, D.; Ohlsson, C. Both Low and High Serum IGF-I Levels Associate with Cancer Mortality in Older Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 4623–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camhi, S.M.; Bray, G.A.; Bouchard, C.; Greenway, F.L.; Johnson, W.D.; Newton, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Ryan, D.H.; Smith, S.R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. The Relationship of Waist Circumference and BMI to Visceral, Subcutaneous, and Total Body Fat: Sex and Race Differences. Obesity 2011, 19, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongraw-Chaffin, M.L.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Allison, M.A.; Ouyang, P.; Szklo, M.; Vaidya, D.; Woodward, M.; Golden, S.H. Association Between Sex Hormones and Adiposity: Qualitative Differences in Women and Men in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E596–E600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Sairam, M.R. Sex hormone imbalances and adipose tissue dysfunction impacting on metabolic syndrome; a paradigm for the discovery of novel adipokines. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2014, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hafe, P.; Pina, F.; Pérez, A.; Tavares, M.; Barros, H. Visceral fat accumulation as a risk factor for prostate cancer. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1930–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosgood, H.D.; Gunter, M.J.; Murphy, N.; Rohan, T.E.; Strickler, H.D. The Relation of Obesity-Related Hormonal and Cytokine Levels with Multiple Myeloma and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquali, R.; Casimirri, F.; De Iasio, R.; Mesini, P.; Boschi, S.; Chierici, R.; Flamia, R.; Biscotti, M.; Vicennati, V. Insulin regulates testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations in adult normal weight and obese men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 654–658. [Google Scholar]

- Frasor, J.; Danes, J.M.; Komm, B.; Chang, K.C.N.; Lyttle, C.R.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S. Profiling of Estrogen Up- and Down-Regulated Gene Expression in Human Breast Cancer Cells: Insights into Gene Networks and Pathways Underlying Estrogenic Control of Proliferation and Cell Phenotype. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 4562–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberger, N.; Somasundaram, A.; Stabile, L. The Role of the Estrogen Pathway in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suba, Z. Triple-negative breast cancer risk in women is defined by the defect of estrogen signaling: Preventive and therapeutic implications. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2014, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittermann, S.I.; Issekutz, A.C. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, FGF-2) potentiates leukocyte recruitment to inflammation by enhancing endothelial adhesion molecule expression. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Ohta, H. Pathophysiological roles of FGF signaling in the heart. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korc, M.; Friesel, R.E. The role of fibroblast growth factors in tumor growth. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2009, 9, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, D.; Benham, V.; Bullard, B.; Kearney, T.; Hsia, H.C.; Gibbon, D.; Demireva, E.Y.; Lunt, S.Y.; Bernard, J.J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor is a mechanistic link between visceral adiposity and cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6668–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benham, V.; Chakraborty, D.; Bullard, B.; Bernard, J.J. A role for FGF2 in visceral adiposity-associated mammary epithelial transformation. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, X.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Pan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Jia, W.-P. Associations of serum fibroblast growth factor 23 levels with obesity and visceral fat accumulation. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masai, H.; Joki, N.; Sugi, K.; Moroi, M. A preliminary study of the potential role of FGF-23 in coronary calcification in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2013, 226, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, O.M.; Januzzi, J.L.; Isakova, T.; Laliberte, K.; Smith, K.; Collerone, G.; Sarwar, A.; Hoffmann, U.; Coglianese, E.; Christenson, R.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2009, 119, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.J.; Wu, M.-S. Fibroblast growth factor 23: A possible cause of left ventricular hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 337, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ix, J.H.; Katz, R.; Kestenbaum, B.R.; De Boer, I.H.; Chonchol, M.; Mukamal, K.J.; Rifkin, D.; Siscovick, D.S.; Sarnak, M.J.; Shlipak, M.G. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and death, heart failure, and cardiovascular events in community-living individuals: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, C.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, W. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 is associated with angiographic severity and extent of coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Liu, Y. DNA methylation in human diseases. Genes Dis. 2018, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Yarychkivska, O.; Boulard, M.; Bestor, T.H. DNA methylation and DNA methyltransferases. Epigenet. Chromatin 2017, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, H.H.; Marsit, C.J.; Kelsey, K.T. Global Methylation in Exposure Biology and Translational Medical Science. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Hopp, L.; Liu, X.; Wohland, T.; Rohde, K.; Cancello, R.; Klös, M.; Bacos, K.; Kern, M.; Eichelmann, F.; et al. Genome-wide DNA promoter methylation and transcriptome analysis in human adipose tissue unravels novel candidate genes for obesity. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, D.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Torres, J.A.; Morcillo, S.; Ocaña-Wilhelmi, L.; Tinahones, F.J.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Cardona, F. Altered Adipose Tissue DNA Methylation Status in Metabolic Syndrome: Relationships Between Global DNA Methylation and Specific Methylation at Adipogenic, Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Candidate Genes and Metabolic Variables. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcot, V.; Tchernof, A.; Deshaies, Y.; Pérusse, L.; Bélisle, A.; Marceau, S.; Biron, S.; Lescelleur, O.; Biertho, L.; Vohl, M.-C. LINE-1 methylation in visceral adipose tissue of severely obese individuals is associated with metabolic syndrome status and related phenotypes. Clin. Epigenet. 2012, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Tseng, L.-M.; Lee, H.-C. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer progression. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynam-Lennon, N.; Connaughton, R.M.; Carr, E.; Mongan, A.M.; O’Farrell, N.J.; Porter, R.K.; Brennan, L.; Pidgeon, G.P.; Lysaght, J.; Reynolds, J.; et al. Excess visceral adiposity induces alterations in mitochondrial function and energy metabolism in esophageal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernochet, C.; Damilano, F.; Mourier, A.; Bezy, O.; Mori, M.A.; Smyth, G.; Rosenzweig, A.; Larsson, N.; Kahn, C.R. Adipose tissue mitochondrial dysfunction triggers a lipodystrophic syndrome with insulin resistance, hepatosteatosis, and cardiovascular complications. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 4408–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Pharmacotherapy for obesity. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 68, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Blandon, J.; Rude, J.; Elfar, A.; Mukherjee, D. PPAR- γ Agonist in Treatment of Diabetes: Cardiovascular Safety Considerations. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 10, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, P.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Medina-Gómez, G. PPARs and Metabolic Disorders Associated with Challenged Adipose Tissue Plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Mahankali, A.; Matsuda, M.; Mahankali, S.; Hardies, J.; Cusi, K.; Mandarino, L.; DeFronzo, R. Effect of Pioglitazone on Abdominal Fat Distribution and Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2784–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Wolski, K.; Nicholls, S.J.; Nissen, S.E. Pioglitazone and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA 2007, 298, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K. Rosiglitazone Revisited. Arch Intern Med. 2010, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, V.; Nicolosi, M.L.; Giuliano, S.; Bellomo, M.; Belfiore, A.; Malaguarnera, R. PPAR-γ Agonists As Antineoplastic Agents in Cancers with Dysregulated IGF Axis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, P.-P.; Sun, X.-C.; Hu, T.-T. Thiazolidinediones and risk of colorectal cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Xie, H.; Ying, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Zheng, X. Pioglitazone use in patients with diabetes and risk of bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monami, M.; Dicembrini, I.; Mannucci, E. Thiazolidinediones and cancer: Results of a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, C.; Utz, A.L.; Schaub, A.E.; Nachtigall, L.; Biller, B.M.K.; Miller, K.K.; Klibanski, A. Growth Hormone Decreases Visceral Fat and Improves Cardiovascular Risk Markers in Women with Hypopituitarism: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2063–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewitt, M.S. The Role of the Growth Hormone/Insulin-Like Growth Factor System in Visceral Adiposity. Biochem. Insights 2017, 10, 117862641770399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, C.; Borai, A. Insulin-like growth factor-II: Its role in metabolic and endocrine disease. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 80, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frühbeck, G. Bariatric and metabolic surgery: A shift in eligibility and success criteria. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deodati, A.; Ferroli, B.B.; Cianfarani, S. Association between growth hormone therapy and mortality, cancer and cardiovascular risk: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2014, 24, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Fu, J.; Huang, X.; Shen, L. Growth hormone replacement therapy reduces risk of cancer in adult with growth hormone deficiency: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthur, N.M.; Tseng, E.; Hutfless, S.; Wilson, L.M.; Suarez-Cuervo, C.; Berger, Z.; Chu, Y.; Iyoha, E.; Segal, J.B.; Bolen, S. Diabetes Medications as Monotherapy or Metformin-Based Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Intern Med. 2016, 164, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappachan, J.M.; Viswanath, A.K. Medical Management of Diabesity: Do We Have Realistic Targets? Curr. Diab. Rep. 2017, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokubuchi, I.; Tajiri, Y.; Iwata, S.; Hara, K.; Wada, N.; Hashinaga, T.; Nakayama, H.; Mifune, H.; Yamada, K. Beneficial effects of metformin on energy metabolism and visceral fat volume through a possible mechanism of fatty acid oxidation in human subjects and rats. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Massey, S.; Story, D.; Li, L. Metformin: An Old Drug with New Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.J. Metformin: Effects on Micro and Macrovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2008, 22, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Das, A.; Chen, J.; Wu, P.; Li, X.; Fang, Z. Metformin in patients with and without diabetes: A paradigm shift in cardiovascular disease management. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Thompson, J.; Hu, Y.; Das, A.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Metformin attenuates ER stress–induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Transl. Res. 2017, 190, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraei, P.; Asadi, I.; Kakar, M.A.; Moradi-Kor, N. The beneficial effects of metformin on cancer prevention and therapy: A comprehensive review of recent advances. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3295–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnoli, C.; Berrino, F.; Venturelli, E.; Abbà, C.; Biglia, N.; Brucato, T.; Cogliati, P.; Danese, S.; Donadio, M.; Zito, G.; et al. Metformin Decreases Circulating Androgen and Estrogen Levels in Nondiabetic Women with Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2013, 13, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zhong, X.; Gao, P.; Shi, J.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y.-X. The Potential Effect of Metformin on Cancer: An Umbrella Review. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colotta, F.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farb, M.G.; Tiwari, S.; Karki, S.; Ngo, D.T.; Carmine, B.; Hess, D.T.; Zuriaga, M.A.; Walsh, K.; Fetterman, J.L.; Hamburg, N.M.; et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibition improves endothelial vasomotor dysfunction of visceral adipose arterioles in human obesity. Obesity 2014, 22, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antman, E.M.; Bennett, J.S.; Daugherty, A.; Furberg, C.; Roberts, H.; Taubert, K.A. Use of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs. Circulation 2007, 115, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Cannon, P.J. COX-2 Inhibitors and Cardiovascular Risk. Science 2012, 336, 1386–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurpinar, E.; Grizzle, W.E.; Piazza, G.A. COX-Independent Mechanisms of Cancer Chemoprevention by Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.W.C.; Loo, W.T.Y.; Toi, M. Current directions for COX-2 inhibition in breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2005, 59, S281–S284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.; Muszbek, L.; Komáromi, I. Mechanism of the irreversible inhibition of human cyclooxygenase-1 by aspirin as predicted by QM/MM calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2013, 40, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornelas, A.; Zacharias-Millward, N.; Menter, D.G.; Davis, J.S.; Lichtenberger, L.; Hawke, D.; Hawk, E.; Vilar, E.; Bhattacharya, P.; Millward, S. Beyond COX-1: The effects of aspirin on platelet biology and potential mechanisms of chemoprevention. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenghat, F.J.; Davis, A.M. Management of Blood Cholesterol. JAMA 2019, 321, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesterle, A.; Laufs, U.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiki, N.; Mantzoros, C.S. Statins in relation to adiponectin: A significant association with clinical implications. Atherosclerosis 2016, 253, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raggi, P.; Gadiyaram, V.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Lopaschuk, G.; Stillman, A.E. Statins Reduce Epicardial Adipose Tissue Attenuation Independent of Lipid Lowering: A Potential Pleiotropic Effect. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.G.; Singh, P.P.; Murad, M.H.; Iyer, P.G. Statins Are Associated With Reduced Risk of Esophageal Cancer, Particularly in Patients With Barrett’s Esophagus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Li, T.; He, Y.; Deng, Y.; Peng, Q.; Li, S.; Qin, X. Association between statin use and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis of 42 studies. Cancer Causes Control 2014, 25, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Singh, S. Statins are associated with reduced risk of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Y. Impact of statin use on cancer-specific mortality and recurrence. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, M.; Haghjooy-Javanmard, S.; Eshraghi, A.; Vaseghi, G.; Hayatshahi, A.; Thomas, J. Statins Use and Risk of Breast Cancer Recurrence and Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, B.A.P.; Dayspring, T.D.; Toth, P.P. Ezetimibe therapy: Mechanism of action and clinical update. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2012, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takase, H.; Dohi, Y.; Okado, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Goto, Y.; Kimura, G. Effects of ezetimibe on visceral fat in the metabolic syndrome: A randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 42, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolezelova, E.; Stein, E.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Nachtigal, P.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of ezetimibe on plasma adipokines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Tang, M.; Liu, F.; Xia, P.; Shu, M.; Wu, X. Ezetimibe for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality events. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Ohnishi, H.; Morimoto, N.; Minami, S.; Ishioka, M.; Watanabe, S.; Tsukui, M.; Takaoka, Y.; Nomoto, H.; Isoda, N.; et al. Ezetimibe suppresses development of liver tumors by inhibiting angiogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cancer. Sci. 2019, 110, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masko, E.M.; Alfaqih, M.A.; Solomon, K.R.; Barry, W.T.; Newgard, C.B.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Valilis, N.A.; Phillips, T.E.; Poulton, S.H.; Freedland, A.R.; et al. Evidence for Feedback Regulation Following Cholesterol Lowering Therapy in a Prostate Cancer Xenograft Model. Prostate 2017, 77, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).