Abstract

Ataxia is a common clinical feature in inherited metabolic disorders. There are more than 150 inherited metabolic disorders in patients presenting with ataxia in addition to global developmental delay, encephalopathy episodes, a history of developmental regression, coarse facial features, seizures, and other types of movement disorders. Seizures and a history of developmental regression especially are important clinical denominators to consider an underlying inherited metabolic disorder in a patient with ataxia. Some of the inherited metabolic disorders have disease specific treatments to improve outcomes or prevent early death. Early diagnosis and treatment affect positive neurodevelopmental outcomes, so it is important to think of inherited metabolic disorders in the differential diagnosis of ataxia.

1. Introduction

Coordination and balance are controlled by a complex network system including the basal ganglia, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, peripheral motor, and sensory pathways. The cerebellum contributes to coordination, quality of movement, and cognition. There are a large number of inherited metabolic disorders affecting the cerebellum and resulting in cerebellar atrophy or hypoplasia [1,2].

Ataxia is described as abnormal coordination secondary to cerebellar dysfunction, vestibular dysfunction, or sensorial dysfunction. Ataxia can present as gait ataxia, truncal ataxia, tremor, or nystagmus depending on the involved parts of the nervous system [3,4]. All types of ataxia can present individually or in combination in a single patient. Ataxia can be an important part of the clinical picture in inherited metabolic disorders which can guide physicians to targeted investigations to identify underlying causes. This is particularly important for diagnosing treatable inherited metabolic disorders to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Inherited metabolic disorders are individually rare, but their collective prevalence is about 1 in 1000 live births. Inborn Errors of Metabolism Knowledgebase listed more than 150 inherited metabolic disorders presenting with ataxia (http://www.iembase.org/gamuts/store/docs/Movement_disorders_in_inherited_metabolic_disorders.pdf, accessed on 29 May 2020) [5].

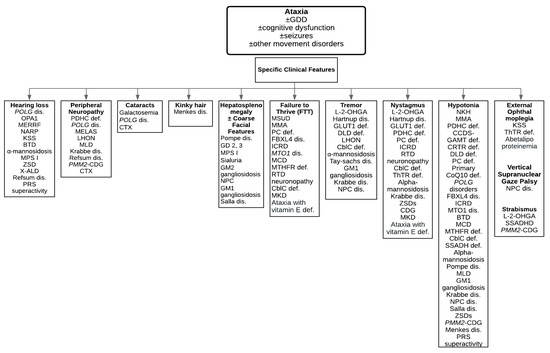

Ataxia is usually part of a complex phenotype in inherited metabolic disorders. There are several important features and signs to point towards inherited metabolic disorders (Figure 1). In medical history, the presence of recurrent somnolence and coma episodes during intercurrent illnesses, a history of protein aversion or failure to thrive, a history of progressive loss of skills, hearing loss, hair abnormalities, behavioral problems, and seizures in combination with ataxia and global developmental delay can guide physicians to consider inherited metabolic disorders in their differential diagnosis. In family history, global developmental delay, cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric disorders, recurrent miscarriage, sudden infant death syndrome, and congenital malformations in other family members can be important clues to consider inherited metabolic disorders in the differential diagnosis. Some of the clinical features together with ataxia can suggest inherited metabolic disorders such as hepatosplenomegaly (lysosomal storage disorders), cardiomyopathy (lysosomal storage disorders, mitochondrial disorders, congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG)), complex movement disorders (mitochondrial disorders, organic acidurias, neurotransmitter disorders), macrocephaly (Canavan disease, lysosomal storage disorders), or microcephaly (glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) deficiency, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis ((NCL)). To investigate the underlying causes, detailed medical history, family history, and physical examination are important to obtain.

Figure 1.

A diagnostic algorithm to guide physicians towards characteristic clinical features. Abbreviations: BTD = Biotinidase deficiency; cblC def = Cobalamin C deficiency; CCDS = Cerebral creatine deficiency syndromes; DLD def = Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency; GLUT1 def = Glucose transporter 1 deficiency; ICRD = Infantile cerebellar-retinal degeneration; KSS = Kearns-Sayre syndrome; L-2-OHGA = L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria; LHON = Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; MCD = Multiple carboxylase deficiency; MKD = Mevalonate kinase deficiency; MLD = Metachromatic leukodystrophy; MMA = Methylmalonic acidemia; MSUD = Maple syrup urine disease; MTHFR def = Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency; NKH = Nonketotic hyperglycinemia; NPC dis = Niemann-Pick type C disease; PC def = Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency; PDHC def = Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency; PMM2-CDG = Phosphomannomutase 2-Congenital disorder of glycosylation; PRS superactivity = Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity; Primary CoQ10 def = Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency; RTD = Riboflavin transporter deficiency; SSADH def = Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency; ThTR def = Thiamine transporter deficiency; ZSDs = Zellweger spectrum disorders.

Some of the inherited metabolic disorders can present with episodic or intermittent ataxia during intercurrent illness, stress situations, or prolonged fasting. This is due to an increased energy demand and decreased energy production due to the defects in energy metabolism pathways and in the production or transport of fuels such as glucose and ketone bodies, or the increased production of toxic metabolites such as amino acids or organic acids secondary to catabolism. Episodic or intermittent ataxia can be observed in maple syrup urine disease, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) deficiency, and GLUT1 deficiency. In progressive neurodegenerative disorders, e.g., lysosomal storage disorders, ataxia is usually progressive. In energy metabolism disorders, ataxia is usually static with acute episodes of deterioration during intercurrent illnesses. It is important to remember these disorders to initiate diagnostic investigations and start appropriate treatment.

Recently, we reported the genetic landscape of pediatric movement disorders. Ataxia was the most common movement disorder in 53% of the patients who underwent genetic investigation in our clinic [6]. Interestingly, 74% of patients with ataxia had 16 different underlying genetic diseases. There were 8 different inherited metabolic disorders including GLUT1 deficiency, SURF1 Leigh’s disease, PDHC deficiency, DNAJC19 disease, ND3 mitochondrial encephalopathy, NCL type 2, riboflavin transporter deficiency, and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase 2 deficiency [6]. Seizure and a history of developmental regression are especially important clinical denominators when considering the underlying inherited metabolic disorders in patients with ataxia.

Cerebellar atrophy in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be found in mitochondrial disorders (e.g., mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP), Kearns–Sayre syndrome, leukoencephalopathy with brain stem, spinal cord involvement, and lactate elevation, PDHC deficiency, primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, POLG disease), lysosomal storage disorders (metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), GM2 gangliosidosis, Niemann–Pick type C (NPC), Salla disease, NCL, fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration), classical galactosemia, L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria, Menkes disease, and mevalonate kinase deficiency [1,2].

Table 1 summarizes the vast majority of inherited metabolic disorders presenting with ataxia, including category of inherited metabolic disorders, genes, and clinical features. Table 2 lists metabolic investigations. Disease-specific treatments to improve outcomes in inherited metabolic disorders are summarized in Table 3 [5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. We provide a list of disorders based on the specific clinical features in Figure 1 [36]. In this review article, we list some of the treatable inherited metabolic disorders in details below.

Table 1.

Inherited metabolic disorders presenting with ataxia are summarized by disease category, genetic defect, and clinical features.

Table 2.

Metabolic investigations for inherited metabolic disorders causing ataxia.

Table 3.

Inherited metabolic disorders with specific treatments to amenable disease outcomes and their biochemical and neuroimaging features are summarized in Table 2.

2. Treatable Inherited Metabolic Disorders Presenting with Ataxia

2.1. Disorders of Amino Acid Metabolism and Transport

Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD)

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive disorder of branched chain amino acid (leucine, valine, isoleucine) catabolism due to branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex (BCKD) deficiency encoded by BCKDHA, BCKDHB, and DBT genes [7,8]. The BCKD complex deficiency results in the accumulation of leucine, valine, isoleucine, and alloisoleucine [7,9]. Its estimated incidence is 1 in 185,000 live births, with a higher prevalence of up to 1 in 113 in Ashkenazi Jewish populations due to a founder pathogenic variant in BCKDHB (c.548G > C) [7].

Phenotypes of MSUD consist of classical, intermediate, intermittent, and thiamine responsive [7,8]. The classical MSUD, or severe neonatal onset form, presents in the first week of life with feeding intolerance, encephalopathy, and seizures. Characteristic maple syrup odor can be present in cerumen as early as 12 hours [7,8,9]. If left untreated, the severe neonatal onset form may progress to coma or death secondary to brain edema [8]. Intermediate and intermittent forms typically manifest during any age ranging from infantile to adulthood. Clinical features of the intermediate form include global developmental delay, failure to thrive, maple syrup urine smell, and intermittent episodes of encephalopathy during intercurrent illnesses [7,8]. Usually, patients with the intermittent form may have normal early development and growth and can be missed until a catabolic state or intercurrent febrile illness when ataxia may manifest as an initial presentation [7,8]. The clinical presentation of the thiamine responsive form is similar to the intermediate form and is responsive to thiamine supplementation.

In the neonatal period, the acute elevation of leucine levels results in fencing and bicycling movements, irritability, and opisthotonos. In older children, the acute elevation of leucine levels results in acute neurological deterioration characterized by an altered level of consciousness, acute dystonia, and ataxia which may progress to coma. Hyperactivity, sleep disturbances, and hallucinations are also reported.

Patients with classical MSUD can be identified by positive newborn screening for MSUD or with the above symptoms. Plasma amino acid analysis reveals elevated leucine, alloisoleucine, valine, and isoleucine. Elevated ketones may cause metabolic acidosis. Ammonia is usually normal in MSUD patients but may be mild to moderately elevated during acute metabolic decompensations in some patients [9]. Intermediate and intermittent forms are often missed by newborn screening due to higher BCKD activity resulting in initial normal leucine plus isoleucine levels [7,8]. Plasma amino acid analysis can be normal or mildly elevated in intermittent forms of MSUD outside of metabolic decompensations. In patients with episodes of ataxia during intercurrent illness, plasma amino acid analysis is highly recommended; if plasma amino acid analysis is not collected during an acute metabolic decompensation, the intermittent form of MSUD can be missed.

Treatment consists of a dietary restriction of leucine, supplementation of valine and isoleucine, and branched chain amino acid free medical formula. During intercurrent illness, caloric intake should be increased to prevent catabolism and leucine elevation, which could result in acute encephalopathy and brain edema [7,8]. If medical treatment is not successful in decreasing leucine levels, hemodialysis is undertaken to remove leucine and prevent coma and death due to leucine toxicity [9]. If patients require strict leucine restriction and several hospital admissions during intercurrent illnesses, non-related orthotopic liver transplantation is the treatment of choice [9].

2.2. Disorders of Carbohydrate Metabolism

2.2.1. Galactose-1-phosphate Uridylyltransferase Deficiency

Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder of the galactose metabolism. Galactosemia is due to biallelic pathogenic variants in GALT [10]. Its prevalence is 1 in 48,000 as per the National Newborn Screening and Genetics Resources Center. It is more common in Ireland with a prevalence of 1 in 16,476 [11,12]. GALT deficiency results in the accumulation of galactose, galactose-1-phosphate, and galactitol [10,11,12].

Classical galactosemia patients present in the neonatal period with feeding problems, hepatic failure, and coagulopathy that can acutely progress to multi organ failure and potentially death if untreated [10,11,12]. Despite adequate treatment with galactose restricted diet, patients can suffer from developmental delay, speech delay, and motor dysfunction presenting with ataxia and tremor. Females are at risk of gonadal dysfunction and premature ovarian insufficiency [11,12].

The long-term neurodevelopmental outcome is characterized by speech problems, learning difficulties, and cognitive dysfunction even in treated patients. A small number of patients present with tremor, either intentional or postural, cerebellar ataxia, and dystonia.

The National Newborn Screening Programs included galactosemia in their list of disorders to identify and treat newborns early. Diagnosis is confirmed by the measurement of erythrocyte galactose-1-phosphate concentration or reduced GALT enzyme activity [11]. Treatment consists of dietary lactose and galactose restriction [10].

2.2.2. Glucose Transporter 1 (GLUT1) Deficiency

Glucose is transported from the bloodstream to the central nervous system by glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), encoded by SLC2A1. A genetic defect in this transporter protein results in impaired glucose supply to the brain, affecting brain development and function, called GLUT1 deficiency. Since its first description, there have been about 400 patients reported in the literature [13]. It is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by heterozygous pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in SLC2A1.

The phenotype ranges from early onset severe global developmental delay, epileptic encephalopathy, acquired microcephaly, ataxia, dystonia, and spasticity to paroxysmal movement disorder including intermittent ataxia, choreoathetosis, dystonia, and alternating hemiplegia with or without cognitive dysfunction or intellectual disability. In a study, 57 patients with GLUT1 deficiency were reported with their distribution of movement disorders. Ataxia and ataxia plus spastic gait were the most common movement disorder in 70% of the patients. Ataxia improved after feeding in some of the patients [14].

The characteristic biomarker is low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) glucose or low CSF to blood glucose ratio in the presence of normal blood glucose. Blood glucose should be collected within 30 min prior to lumbar puncture. If blood glucose is not collected, the CSF glucose level is also helpful to guide the diagnosis of GLUT1 deficiency. The CSF-to-blood glucose ratio ranges between 0.19 and 059 and the CSF glucose ranges between 0.9 and 2.88 mmol/L in patients with GLUT1 deficiency [13]. The diagnosis is confirmed by either a genetic test using targeted next generation sequencing for epilepsy, movement disorders, intellectual disability, or whole exome sequencing. In patients with low CSF glucose levels, direct Sanger sequencing of SLC2A1 can be applied to confirm the diagnosis [13]. In about 90% of patients, diagnosis is confirmed by sequence analysis and in about 10% of the patients, a deletion/duplication test is important to apply to identify small deletion and duplications.

The ketogenic diet has been the gold standard for the treatment of GLUT1 deficiency. The response to treatment varies depending on the age of diagnosis and application of the ketogenic diet. About 65% of patients become seizure free in one week to one month of the ketogenic diet therapy. It is recommended that beta-hydroxybutyrate levels are kept at 4–5 mM. The response to the ketogenic diet is variable.

2.3. Disorder of Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism

2.3.1. Creatine Deficiency Disorders

Arginine, glycine amino acid, L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT), and guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT) are involved in creatine synthesis in the kidney and liver. After synthesis, creatine is taken up by high energy demanding organs, such as the brain, muscles, and the retina by an active sodium chloride dependent creatine transporter (CRTR). There are three disorders involving synthesis and transport of creatine, including AGAT, GAMT, and CRTR deficiencies. The first two enzyme deficiencies are inherited autosomal recessively while CRTR deficiency is an X-linked disorder. They are ultra-rare disorders with less than 130 patients with GAMT deficiency, less than 20 patients with AGAT deficiency, and less than 200 patients with CRTR deficiency reported so far [15].

Global developmental delay and cognitive dysfunction are the most common clinical features and present in all untreated patients in the three creatine deficiency disorders. Epilepsy, movement disorders, and behavioral problems are observed in GAMT and CRTR deficiencies. The phenotype ranges from asymptomatic to severe phenotypes in females in CRTR deficiency. GAMT deficiency leads to complex movement disorders in combination with ataxia and tremor; choreoathetosis and dystonia; dystonia, chorea, and ataxia; myoclonus and bradykinesia; or ballismus and dystonia [16]. In a study, 50% of the patients who were older than 6 years of age at the time of the diagnosis of GAMT deficiency presented with ataxia [17]. In 101 male patients with CRTR deficiency, a wide based gait, ataxia, dysarthria, and coordination problems were reported in 29% of them [18].

The biochemical hallmarks are cerebral creatine deficiency in brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in GAMT and AGAT deficiencies as well as in males with CRTR deficiency. Urine, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) guanidinoacetate is elevated in GAMT deficiency, low in AGAT deficiency, and normal in CRTR deficiency. The urine creatine is elevated in males with CRTR deficiency. Females can have a normal or mildly elevated urine creatine. In the presence of abnormal biochemical features, Sanger sequencing of GAMT, GATM or SLC6A8 confirms the diagnosis of these disorders [15].

Creatine supplementation is applied in all creatine deficiency disorders. Ornithine supplementation and protein- or arginine-restricted diet are applied in GAMT deficiency. Arginine and glycine supplementation are applied in CRTR deficiency [15]. Epilepsy improves in about two-thirds of the patients with GAMT deficiency and movement disorder improves in about 50% of the patients with GAMT deficiency.

2.3.2. Primary Coenzyme Q10 Deficiency

Coenzyme Q10 is an essential cofactor involved in various cellular pathways including the electron transport chain, the beta oxidation of fatty acids, and pyrimidine biosynthesis [19]. There are more than 10 genetic defects involved in the coenzyme Q10 biosynthesis causing primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency (Table 1) [19,20]. The genes associated with primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency are listed in Table 1. Inherited primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency disorders are autosomal recessive disorders [20].

The clinical features of primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency are complex and involve multiple organs or systems including global developmental delay, cognitive dysfunction, seizures, ataxia, movement disorder, spasticity, cardiomyopathy, hearing loss, peripheral neuropathy, and retinopathy [19,20].

A definitive biochemical diagnosis is confirmed by deficient coenzyme Q10 amounts in muscle biopsy specimen and skin fibroblasts [19,20]. The biochemical diagnosis is confirmed by either targeted next generation sequencing panel for coenzyme Q10 deficiency or by whole exome sequencing.

Treatment consists of oral coenzyme Q10 supplementation, which is well tolerated. The response to the treatment is variable and treatment outcome data is sparse [19,20].

2.4. Vitamin and Cofactor Responsive Disorders

2.4.1. Biotinidase Deficiency

Biotinidase deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder due to the biallelic pathogenic variants in BTD, encoding biotinidase [21]. Biotinidase is responsible for the recycling of biotin from biocytin to contribute to the free biotin pool. Biotin is an important cofactor for the conversion of apocarboxylases to holocarboxylases, including pyruvate carboxylase, 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, propionyl CoA carboxylase, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase [21,22]. Biotinidase deficiency is sometimes referred to as late onset multiple carboxylase deficiency, as biotin deficiency impacts numerous enzymatic processes [22]. Its estimated prevalence is 1 in 60,000 worldwide, including 1 in 137,000 for profound and 1 in 110,000 for partial biotinidase deficiency [22,23]. In some expanded newborn screening programs, biotinidase deficiency is included to identify newborns in the asymptomatic stage.

Profound biotinidase deficiency can present with seizures, alopecia, hypotonia, and skin rash in the first few months of life. If left untreated, patients present with global developmental delay, ataxia, optic atrophy, ophthalmological problems, and hearing loss [21,22,23]. Older patients with later onset tend to display ataxia and movement disorders as initial clinical presentations [23].

Untreated biotinidase deficiency has numerous biochemical abnormalities including metabolic acidosis, hyperammonemia, or lactic acidosis which may present as an acute metabolic decompensation during intercurrent illness [22]. An abnormal acylcarnitine profile and urine organic acid analysis are suggestive and biochemical diagnosis is confirmed by deficient biotinidase activity in serum. If the biotinidase activity is less than 10% normal, it is called profound deficiency. If the biotinidase activity is 10–30% normal, it is called partial deficiency [23].

Treatment consists of lifelong biotin supplementation, resolving seizures, ataxia, skin rash, and alopecia quickly [21,22]. If hearing loss, vision problems, or severe developmental delay present, biotin supplementation will not resolve them, indicating the importance of early intervention [21,22,23].

2.4.2. Riboflavin Transporter Deficiency

Riboflavin is a precursor of flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), which are crucial cofactors for the electron transport chain and beta oxidation of fatty acids in the mitochondria for energy production. To maintain riboflavin metabolism in the human body, riboflavin is transported across membranes using riboflavin transporters including RFVT1, encoded by SLC52A1, RFVT2, encoded by SLC52A2 and RFVT3, encoded by SLC52A3. Biallelic pathogenic variants in SLC52A2 and SLC52A3 are reported in human disease after 2010. Both genetic defects are associated with previously known Brown–Vialetto–Van Laere (BVVL) and Fazio–Londe (FL) syndromes [24].

Disease onset ranges from early infantile onset to early adulthood onset. Usually, a history of developmental regression is the initial symptom. Symptoms range from motor dysfunction, muscle weakness, hypotonia, ataxia, failure to thrive, or hearing loss to peripheral neuropathy. Bulbar symptoms, respiratory failure, and optic atrophy are also common features. These are progressive disorders, if untreated.

Diagnosis is suspected by acylcarnitine profile and urine organic acid abnormalities resembling multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency or ethylmalonic aciduria. Complex II deficiency in muscle biopsy has been reported in two patients with riboflavin transporter deficiency [25].

Diagnosis is confirmed either by the direct Sanger sequencing of SLC52A2 and SLC52A3 genes or the application of targeted next generation sequencing panels for nuclear mitochondrial disorders or whole exome sequencing.

High dose oral riboflavin supplementation is the treatment. The timing of treatment onset is essential for favorable treatment outcomes [24,25].

2.5. Organelle Related Disorders: Lysosomal Storage Disorders

Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCL)

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL) are the most common lysosomal storage disorders with an estimated prevalence of 1.5 to 9 per a million people [26]. There are more than 10 subtypes. The most common subtypes are type 2, CLN2, and type 3, CLN3 diseases. Disease onset ranges from infantile to adulthood even within the same subtype.

Clinical features are characterized by a history of developmental regression in motor and cognitive functions, seizures, visual problems, and early death [27]. Progressive ataxia is a common feature in NCL secondary to progressive cerebellar atrophy [6]. The first symptom is usually a seizure which is followed by developmental regression. Motor dysfunction is characterized by myoclonus in infants and ataxia and spasticity in older children.

Three of the NCL genes encode an enzyme, cathepsin D, encoded by CTSD; palmitoyl-protein thioesterase, encoded by PPT1 or CLN1, and tripeptidylpeptidase 1, encoded by TPP1 or CLN2 [28]. Granular osmiophilic, curvilinear, and fingerprint lipopigments identified by the electron microscopic examination of lymphocytes, skin cells, or cells from conjunctival biopsy are the suggestive neuropathological features of NCL. The diagnosis is confirmed by targeted Sanger sequencing, the application of an NCL panel, or whole exome sequencing. Many NCL genes are also included in targeted next generation sequencing panel for epilepsy [29].

Treatment is symptomatic for the majority of NCL. Recently, intracerebroventricular cerliponase alfa infusions for the treatment of CLN2 (TPP1) disease was approved for clinical use [27,30]. Trials for CLN3 and CLN6 are underway in clinical Phase I/II human studies.

2.6. Organelle Related Disorders: Peroxisomal Disorders

2.6.1. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD)

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD) is due to hemizygous pathogenic variants in ABCD1, which encodes ATP-binding cassette domain 1 (ABCD1). This protein is a peroxisome transporter protein. Due to the pathogenic variants and ABCD1 dysfunction, very long chain fatty acids accumulate, especially in the adrenal glands and the brain. Its estimated prevalence is 1 in 20,000 males [31].

The age of symptom onset is variable and ranges from childhood to adulthood. The most severe form is the childhood onset cerebral form. After normal cognitive and motor function, males present with behavioral problems, followed by progressive motor and cognitive dysfunction and progressive ataxia between the ages of 4 and 8 years, leading to complete motor and cognitive dysfunction within a few years. The cerebral form can also be seen in adolescents and adults with a slower disease progression [31]. Adrenal insufficiency is a common feature requiring hormone replacement therapy. Adrenomyeloneuropathy is the most common phenotype, with spinal cord disease leading to chronic progressive spasticity, neuropathy, and incontinence [31,32].

The diagnosis is suspected by characteristic brain MRI features including symmetrical increased signal intensity in parieto-occipital region in T2 weighted images. Active demyelination areas are enhanced with contrast. The biochemical hallmark is elevated plasma very long chain fatty acids. The diagnosis is confirmed by direct sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of ABCD1 [31,32].

The treatment is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in males, with disease progression stopping after HSCT. The decision for HSCT depends on disease morbidity. In males with extensive white matter changes, motor, and cognitive dysfunction, HSCT is not recommended [31,32].

2.6.2. Refsum Disease

Refsum disease is called classic or adult Refsum disease. This is an autosomal recessively inherited peroxisomal disease due to biallelic variants in PHYH (>90%, encodes phytanoyl-CoA hydroxylase [35].

The age of onset ranges from 7 months to older than 50 years. Retinitis pigmentosa and anosmia are early clinical features. About 10–15 years later, neuropathy, ataxia, muscle weakness, sensory loss, deafness, and ichthyosis are the part of the clinical features. Initially, patients present with an unsteady gait which progresses to ataxia as a result of cerebellar dysfunction. Additionally, motor and sensory polyneuropathy, skeletal abnormalities, and cardiac arrhythmias have been reported [35].

Elevated plasma phytanic acid and pipecolic acid suggest the diagnosis of Refsum disease. The diagnosis is confirmed by direct Sanger sequencing of PHYH [35].

The treatment consists of phytanic acid restricted diet. This diet can improve polyneuropathy, ataxia and ichthyosis and arrhythmias due to decrease in plasma phytanic acid levels. In acute onset arrhythmias and severe weakness, plasmapheresis or lipopheresis can be used to improve symptoms. Weight loss or decreased caloric intake mobilizes stored lipids and causes the acute deterioration of symptoms, which should be avoided by a high caloric intake diet [35].

3. Conclusions

Inherited metabolic disorders are individually rare. Some inherited metabolic disorders have disease-specific treatments to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes and to prevent early death. It is important to think of inherited metabolic disorders in the differential diagnosis of ataxia.

A medical history of somnolence and coma during intercurrent illness, the progressive loss of skills, hearing loss, behavioral problems, seizures, and global developmental delay are important to suggest inherited metabolic disorder. A history of developmental regression is an important symptom to suggest lysosomal storage disorders. Detailed three-generation family history can help identifying X-linked, autosomal dominant, or mitochondrial disorders. A family history of global developmental delay, cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric disorders, recurrent miscarriage, sudden infant death syndrome, and congenital malformations can suggest inherited metabolic disorders. A detailed review of neuroimaging can identify specific neuroimaging features to suggest specific inherited metabolic disease. For example, progressive ataxia and cerebellar atrophy in brain MRI is suggestive of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. If there is any specific clinical, or neuroimaging feature to suggest a particular inherited metabolic disease, appropriate metabolic investigations can be performed to support the diagnosis. The diagnosis is confirmed by targeted direct Sanger sequencing. If there is no specific clinical, biochemical, or neuroimaging feature, non-targeted genetic investigations including targeted next generation sequencing panel or whole exome or mitochondrial genome sequencing are applied to reach a diagnosis.

Author Contributions

G.S. reviewed the literature, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version. S.M.-A. reviewed the literature, revised the manuscript, and finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Khadine Wiltshire and Serap Vural for formatting the manuscript according to journal requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABCD1 | ATP-binding cassette domain 1 |

| AGAT | Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase |

| BCKD | Branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex |

| BVVL | Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere |

| CDG | Congenital disorders of glycosylation |

| CRTR | Creatine transporter |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FL | Fazio-Londe |

| FMN | Flavin mononucleotide |

| GALT | Galatose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase |

| GAMT | Guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| NCL | Nneuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses |

| PDHC | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency |

| MSUD | Maple syrup urine disease |

| X-ALD | X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy |

References

- Poretti, A.; Wolf, N.I.; Boltshauser, E. Differential diagnosis of cerebellar atrophy in childhood. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. EJPN Off. J. Eur. Paediatr. Neurol. Soc. 2008, 12, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaser, S.I.; Steinlin, M.; Al-Maawali, A.; Yoon, G. The Pediatric Cerebellum in Inherited Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Pattern-recognition Approach. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2016, 26, 373–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, U.; Ashizawa, T. Ataxia. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashizawa, T.; Xia, G. Ataxia. Contin. Minneap. Minn 2016, 22, 1208–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.R.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Blau, N. Clinical and biochemical footprints of inherited metabolic diseases. I. Movement disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 127, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, D.; Bullivant, G.; Siriwardena, K.; Evans, A.; Kobayashi, J.; Cohn, R.D.; Mercimek-Andrews, S. Genetic landscape of pediatric movement disorders and management implications. Neurol. Genet. 2018, 4, e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pode-Shakked, N.; Korman, S.H.; Pode-Shakked, B.; Landau, Y.; Kneller, K.; Abraham, S.; Shaag, A.; Ulanovsky, I.; Daas, S.; Saraf-Levy, T.; et al. Clues and challenges in the diagnosis of intermittent maple syrup urine disease. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, P.R.; Gass, J.M.; Vairo, F.P.E.; Farnham, K.M.; Atwal, H.K.; Macklin, S.; Klee, E.W.; Atwal, P.S. Maple syrup urine disease: Mechanisms and management. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2017, 10, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.A.; Puffenberger, E.G.; Morton, D.H. Maple Syrup Urine Disease. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, S.; O’Sullivan, S.; Sweeney, B.; Lynch, B.; Hanrahan, D.; Knerr, I.; Lynch, S.A.; Crushell, E. Friedreich Ataxia in Classical Galactosaemia. JIMD Rep. 2016, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.T. Classic Galactosemia and Clinical Variant Galactosemia. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer-Krantz, S. Early diagnosis of inherited metabolic disorders towards improving outcome: The controversial issue of galactosaemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, S50–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Pascual, J.M.; De Vivo, D. Glucose Transporter Type 1 Deficiency Syndrome. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, R.; Collins, A.; Rotstein, M.; Engelstad, K.; De Vivo, D.C. The spectrum of movement disorders in Glut-1 deficiency. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2010, 25, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercimek-Mahmutoglu, S.; Salomons, G.S. Creatine Deficiency Syndromes. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Khaikin, Y.; Sidky, S.; Abdenur, J.; Anastasi, A.; Ballhausen, D.; Buoni, S.; Chan, A.; Cheillan, D.; Dorison, N.; Goldenberg, A.; et al. Treatment outcome of twenty-two patients with guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency: An international retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. EJPN Off. J. Eur. Paediatr. Neurol. Soc. 2018, 22, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, S.U.; Scaglia, F.; Li, F.-Y.; Smith, L.; Barshop, B.A.; Eng, C.M.; Haas, R.H.; Hunter, J.V.; Lotze, T.; Maranda, B.; et al. Expanded clinical and molecular spectrum of guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 96, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Kamp, J.M.; Betsalel, O.T.; Mercimek-Mahmutoglu, S.; Abulhoul, L.; Grünewald, S.; Anselm, I.; Azzouz, H.; Bratkovic, D.; de Brouwer, A.; Hamel, B.; et al. Phenotype and genotype in 101 males with X-linked creatine transporter deficiency. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbats, M.A.; Lunardi, G.; Doimo, M.; Trevisson, E.; Salviati, L. Genetic bases and clinical manifestations of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ 10) deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015, 38, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salviati, L.; Trevisson, E.; Doimo, M.; Navas, P. Primary Coenzyme Q10 Deficiency. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, W.; Dumin, Y.; Tal, G.; Zehavi, Y.; Sakran, W.; Spiegel, R. Biotinidase Deficiency: A Treatable Neurological Inborn Error of Metabolism. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. IMAJ 2019, 21, 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, T.M.; Blitzer, M.G.; Wolf, B. Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Technical standards and guidelines for the diagnosis of biotinidase deficiency. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2010, 12, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, B. Biotinidase Deficiency. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan, B.; Bosch, A.M.; Houlden, H. An update on the genetics, clinical presentation, and pathomechanisms of human riboflavin transporter deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, G.A.M.; Ejaz, R.; Cordeiro, D.; Kannu, P.; Mercimek-Andrews, S. Riboflavin transporter deficiency mimicking mitochondrial myopathy caused by complex II deficiency. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018, 176, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, S.E.; Williams, R.E. Neuronal Ceroid-Lipofuscinoses. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mole, S.E.; Anderson, G.; Band, H.A.; Berkovic, S.F.; Cooper, J.D.; Kleine Holthaus, S.-M.; McKay, T.R.; Medina, D.L.; Rahim, A.A.; Schulz, A.; et al. Clinical challenges and future therapeutic approaches for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Kohlschütter, A.; Mink, J.; Simonati, A.; Williams, R. NCL diseases-clinical perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costain, G.; Cordeiro, D.; Matviychuk, D.; Mercimek-Andrews, S. Clinical Application of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Panels and Whole Exome Sequencing in Childhood Epilepsy. Neuroscience 2019, 418, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, A.; Ajayi, T.; Specchio, N.; de Los Reyes, E.; Gissen, P.; Ballon, D.; Dyke, J.P.; Cahan, H.; Slasor, P.; Jacoby, D.; et al. Study of Intraventricular Cerliponase Alfa for CLN2 Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1898–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, G.V.; Moser, A.B.; Fatemi, A. X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mallack, E.J.; Turk, B.; Yan, H.; Eichler, F.S. The Landscape of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant and Gene Therapy for X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2019, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuelke, M. Ataxia with Vitamin E Deficiency. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1241/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Burnett, J.R.; Hooper, A.J.; Hegele, R.A. Abetalipoproteinemia. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532447/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Wanders, R.J.A.; Waterham, H.R.; Leroy, B.P. Refsum Disease. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1353/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Ficicioglu, C.; An Haack, K. Failure to thrive: When to suspect inborn errors of metabolism. Pediatrics. 2009, 124, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).