Abstract

Allium tuberosum, commonly known as garlic chives, is a promising species with significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, useful both fresh and dried as a spice. This study analyzed the chlorophyll, carotenoid, polyphenol content, and antioxidant activity in various parts of two- and three-year-old garlic chives, including green stems, inflorescences, and flowering shoots. The research found that flowering shoots had higher levels of chlorophylls and carotenoids, while inflorescences were rich in total polyphenols and exhibited the highest antioxidant activity. Essential oils extracted from different parts of the plant were analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), revealing distinct chemical profiles. The oils contained unique compounds, with oxygenated monoterpenes predominant in green stems and stems with flower buds, and aliphatic hydrocarbons more prevalent in inflorescences. This study highlights the high antioxidant potential of Allium tuberosum and suggests further research due to its varied chemical composition across different plant parts.

1. Introduction

The health-promoting properties of plants, such as enhancement of the immune system [1], allow the plants to exert beneficial effects on human health [2]. A large number of people worldwide suffer from various diseases, including gastrointestinal disorders caused by numerous pathogenic bacteria such as Bacillus cereus, Listeria spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp., as well as other inflammatory conditions [3]. Antioxidants play a crucial role in maintaining human health [4]. Medicinal plants, as natural sources of bioactive compounds [5,6], also exhibit strong anticancer and antimutagenic activities, neuroprotective effects [7,8], reduce blood glucose and cholesterol levels [9], and influence gut microbiota [8]. Nour et al. [10] highlighted the health benefits of aromatic plants and the absence of any adverse effects. Natural antioxidants present in herbs help mitigate oxidative stress caused by gamma, UV, or X radiation; psycho-emotional stress; contaminated food; adverse environmental conditions; intense physical exertion; smoking; and alcohol consumption [11,12]. It has long been recognized that the role of herbs, as well as vegetables, in proper nutrition is substantial, primarily through their antioxidant activity and by providing a variety of nutritional and health-promoting compounds [13,14]. The number of conscious consumers seeking natural plant-based food additives, such as colorants or flavor enhancers, which are also sources of antioxidant compounds (interest in chlorophylls, carotenoids, and polyphenols is increasing) [9,10,12,15]. Aromatic plants represent an important source of chlorophyll, which exerts beneficial effects on human health as a natural, potent antioxidant [16]. Dried herbs, used as spices, stimulate appetite and positively influence human physiological functions [5], and they are an essential component in culinary preparation [17]. They are also a source of numerous biologically active compounds, including polyphenols [13,18,19], carotenoids—often referred to as “natural pesticides” [20]—and essential oils with antioxidant properties [13]. Aromatic plants and herbs exhibit significant potential in maintaining human health. Therefore, it is justified to expand their repertoire by exploring new plant species, particularly those recommended for organic cultivation, which whether fresh or dried (as spices) demonstrate high antioxidant and health-promoting value as well as appealing colors and aromas, making them suitable as culinary additives.

A highly promising species is Allium tuberosum, which belongs to the family Amaryllidaceae [21], which, in addition to compounds with antimicrobial and antibacterial properties contains numerous substances with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, including polyphenols [3,22,23,24]. The antibacterial activity of garlic chives is attributed to the presence of sulfur-containing compounds [25], which also exhibit anticancer effects [26]. Furthermore, antifungal, antiparasitic, anticancer, hypolipidemic, and renoprotective activities of garlic chives have been reported [2], along with additional benefits such as stimulation of hair growth, regulation of hormonal balance, and aphrodisiac effects. This species is a popular vegetable in Asia and originates from China, where it is widely cultivated due to its significant medicinal properties [27]. The leaves and young inflorescences are the most commonly used parts of the plant [28]. It is also distinguished by its characteristic aroma [29]. Allium tuberosum is consumed as a fresh vegetable, dried, or cooked, and is added to various dishes, including kimchi and pickled cucumbers. The plant grows well even under unfavorable conditions [30] and does not require chemical protection against diseases and pests affecting bulb vegetables [31]. An important factor supporting its wider use is the possibility of utilizing all botanical parts (some of which are often considered by-products) in accordance with the zero-waste principle.

There are no reports on the antioxidant properties of different botanical parts of Allium tuberosum, nor on whether these properties change with plant age. Therefore, this study was undertaken to determine the plant’s antioxidant potential by analyzing the contents of total polyphenols, carotenoids, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll, DPPH radical scavenging activity, and essential oils in various edible parts of garlic chives grown in the second and third growing season. It has been proposed that dried Allium tuberosum exhibits significant antioxidant activity; the level of activity varies among botanical parts and changes with plant age.

2. Results

The results of the study showed that all evaluated botanical parts of Allium tuberosum contain antioxidant compounds, consistent with the findings of Ašimović et al. [32], who reported that vegetables are a good source of phytochemicals. Statistical analysis indicated that the examined parts of garlic chives significantly differed in terms of total polyphenol content, total carotenoids, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, antioxidant activity, and essential oil content. Adamczewska-Sowińska and Turczuk [33] assessed the biological value of garlic chives in the second and third years of vegetation, reporting that this period represents the optimal time for Allium tuberosum to achieve its full biological value. Methanolic extracts obtained from different parts of garlic chives were examined and demonstrated to be rich sources of total polyphenols (Table 1). The highest total polyphenol content was found in the inflorescences, while the lowest was observed in the flowering stems and green stems of garlic chives, with differences of 6.34% and 11.8%, respectively. According to Caser et al. [34], this phenomenon is most likely associated with the production of specialized secondary metabolites by flowers, which play a key role in the reproductive process, as well as with the accumulation of defensive compounds that protect them from herbivores and pathogens. In plants grown in the third season, the highest polyphenol content was recorded in the inflorescences and the lowest in the stems, with a difference of 20.65%. The analyzed plant material contained on average 284.6 mg GAE/100 g of total polyphenols. Compared with the findings of Kopeć-Bieżanowska and Piątkowska [13], who reported in methanolic extracts the highest total polyphenol content in lemon balm (466.55 mg CAE/100 g) and the lowest in ginger (17.23 mg CAE/100 g), these results indicate a substantial richness of polyphenols in garlic chives.

Table 1.

The content of polyphenols (mg GAE/100 g) in garlic chives, depending on the tested part and age of the plant.

In the study, the highest total carotenoid content was detected in the flowering stems, while the lowest was found in the inflorescences of garlic chives (Table 2). Similar relationships were reported by Lachowicz et al. [35] for Allium ursinum. With regard to total carotenoid content in flowers, Watkins [36] demonstrated that the content in white petals is markedly reduced. Higher total carotenoid levels were observed in the flowering stems of both the second and the third growing season, whereas lower levels in the stems in in the second season and inflorescences in the third one. The lowest levels in inflorescences were noticed in the second growing season. A significant relationship was also found between carotenoid content in the examined parts and plant age. Older, three-year-old plants contained 11.6% more carotenoids compared to two-year-old plants. Adamczewska-Sowińska and Turczuk [33] found 9.3% higher carotenoid content in the leaves of biennial garlic chives compared to triennial plants. These divergent results may suggest an influence of cultivation conditions [37]. A precise explanation of the relationship between carotenoid content and plant age indicates the need for further research.

Table 2.

The content of carotenoids (mg/kg DM) in depending on the tested part and age of garlic chives.

Lachowicz et al. [35] reported an average value of 470.4 mg/kg DM of chlorophyll a and 741.4 mg/kg DM of chlorophyll b in the stems of wild garlic and concluded that these stems could be a significant dietary source of chlorophyll for humans. In contrast, the authors found considerably lower chlorophyll levels in the flowers of this species, averaging 299.1 mg/kg DM of chlorophyll a and 461.4 mg/kg DM of chlorophyll b. In the present study, comparing these plant parts in garlic chives, higher levels of chlorophyll a and b were also found in the stems compared to the inflorescences, with increases of 47.5% and 38.2%, respectively (Table 3). However, when we analyzed all examined parts of garlic chives, the highest amounts of chlorophyll a, b, and total chlorophyll were detected in the flowering stems, and the lowest in the inflorescences. Depending on the growing season, significantly higher contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were observed in the flowering stems during both the second and third growing seasons, whereas the lowest contents were observed in the inflorescences of plants from both age groups. In two-year-old plants, this difference was substantial at 125.9 mg/kg DM, while in three-year-old plants it was 57.0 mg/kg DM. It is noteworthy that in garlic chives, higher amounts of chlorophyll a than b were detected in the examined parts, which is opposite to the pattern observed by [35] in wild garlic. According to Ašimović et al. [32], this may be related to external factors and environmental conditions, as chlorophyll a plays a central role in the photosynthetic process [8,38].

Table 3.

The content of assimilation pigments (mg/kg DM) in depending on the tested part and age of garlic chives.

According to Adamczewska-Sowińska and Turczuk [33], the biological value of garlic chive leaves depends on plant age. They reported higher chlorophyll and carotenoid contentsw in the leaves of two-year-old garlic chives. In the present study, however, plant age did not affect the content of these parameters in stems, inflorescences, and flowering stems (Table 1 and Table 3).

Nergui et al. [39] reported the average antioxidant activity measured by the DPPH assay for fresh Allium fistulosum plants (77.8%) and Allium cepa (69.4%). In the present study, the average antioxidant activity of garlic chives was found to be high, at 69.8% (Table 4). The highest antioxidant activity was observed in the inflorescences of Allium tuberosum, and the lowest in the stems. The difference was substantial, amounting to 50.3%. These results suggest that the inflorescences of garlic chives possess a greater capacity to neutralize free radicals than flowering stems and green stems. A similar relationship was demonstrated by Tóth et al. [40] between the flowers and leaves of Allium ursinum.

Table 4.

Antioxidant capacity expressed as percentage inhibition of DPPH free radicals depending on the tested part and age of garlic chives.

Despite similar polyphenol contents in inflorescences and inflorescence stems, inflorescences exhibited a greater capacity to scavenge the DPPH radical. In contrast, green stems showed the lowest polyphenol content, which corresponded to the weakest DPPH radical scavenging activity.

From the fresh parts of garlic chives, light yellow oils with a characteristic garlic leaf-like aroma were obtained in yields of 0.02%, 0.08%, and 0.03% (w/w) for green stems, inflorescences, and stems with flower buds, respectively. A larger amount of essential oil (0.11% w/w) was obtained by Furletti et al. [41] from the fresh aerial parts of A. tuberosum cultivated in Brazil and by Lopes et al. [42] from the fresh leaves of Allium tuberosum cultivated in Brazil (0.3% w/w).

Differences in essential oil content between plants grown in Poland and Brazil may be due to several factors, including differences in the plant parts used, growing conditions, differences in extraction methods, and plant maturity at harvest. Furthermore, the higher oil yields obtained from fresh aerial parts and leaves of plants grown in Brazil may also suggest that the growing conditions in Brazil are more favorable for essential oil production in garlic chives.

The chemical composition of the essential oils (EOs), the percentage content and retention indices of the constituents, and the main classes and chemical groups of the identified compounds are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

The percentage composition of the essential oils obtained from different parts of garlic chives.

A total of 102 compounds were identified in the garlic chives’ stem oil, representing 99.10% of the total oil. The EO consisted mainly of allyl methyl trisulphide (15.26%), linalool (8.00%), diallyl disulphide (7.33%), and dimethyl trisulphide (6.50%).

Concerning the inflorescences’ oil, 91 compounds representing 98.63% of the total EO were identified. The major components were allyl methyl trisulphide (11.58%), 1-pentacosene (7.51%), diallyl disulphide (6.86%), 1-tricosene (5.82%), diallyl trisulphide (5.71%) and 1-heptacosene (5.22%).

One hundred and two constituents, which represented 99.29% of the total oil, were identified in the oil from stems with flower buds. Allyl methyl trisulphide (17.28%) was the major component, followed by dimethyl trisulphide (12.84%), diallyl disulphide (10.00%), allyl methyl disulphide (9.78%), and linalool (8.25%).

Considering the identified compounds, only 53 of them were common for all the oils. The obtained results showed that the chemical composition of A. tuberosum clearly depends on the part of the plant analyzed. Decane, carvone, 2-phenyl-2-butenal, tridecane, methyl cinnamate, β-cubebene, β-gurjunene, cis-3-hexenyl benzoate, τ-muurolol, α-eudesmol, pentadecanal, pentadecanoic acid, 1-nonadecene, palmitic acid, methyl linoleate, methyl stearate, linoleic acid, 6-methylhexacosane, and squalene were detected only in the stem oil, while trans-hex-3-en-1-ol, trans-2-octen-1-ol, nonyl acetate, bicycloelemene, 2-tridecanone, α-muurolol, 5-ethyl-5-methylpentadecane, benzyl benzoate, hexadecanal, 13-epi-manool, 1-docosene, eicosanal, trans-5-eicosene, 1-tetracosene, 5,5-dimethylheneicosane, docosanal, 11-tricosene, 2-methylpentacosane, 3-methylpentacosane, methyl lignocerate, 5,17-dimethylheptacosane, 2-methyloctacosane, and 1-tricontene were present only in the oil extracted from inflorescences. Compounds such as 2-ethylpyridine, cis-hex-3-en-1-ol, heptanal, 1-octen-3-ol, 3-octanol, p-cymene, 2,4-octadienal, β-elemene, β-bourbonene, trans-nerolidol, 2-methylheptadecane, trans-α-atlantone, and 3-methylheptadecane we found only in the oil obtained from stems with flower buds.

The percentage composition of different groups of compounds in Allium tuberosum essential oils (EOs) has been thoroughly examined (refer to Table 5). Oxygenated monoterpenes were identified as the primary constituents in the oils from green stems (15.96%) and stems with flower buds (12.13%), whereas aliphatic hydrocarbons (26.41%) were predominant in the oil from inflorescences. The content of monoterpene hydrocarbons in all the oils did not exceed 0.5%. Additionally, the amount of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons was found to be low in the oils from green stems (2.93%), inflorescences (4.13%), and stems with flower buds (1.61%). Similarly, the levels of oxygenated sesquiterpenes were low, recorded at 0.68%, 4.06%, and 3.12% for green stems, inflorescences, and stems with flower buds, respectively. Furthermore, the content of phenols (2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol and eugenol) in all oil samples was very low, ranging from 0.51% to 0.91%. Estragole, a representative of phenylpropanoids, was detected only in the EOs of green stems (1.96%) and stems with flower buds (0.87%). Conversely, the volatile oil from green stems exhibited a higher content of fatty acids (5.83%) and fatty acid esters (5.27%).

The variations in the composition of essential oils from different parts of Allium tuberosum can be attributed to the distinct biochemical pathways and functions associated with each plant part. The stems, inflorescences, and stems with flower buds each fulfill unique roles within the plant, leading to a divergence in the synthesis of specific compounds. For instance, the predominance of oxygenated monoterpenes in the oils from green stems and stems with flower buds suggests a role in deterring herbivores or attracting pollinators, while the higher concentration of aliphatic hydrocarbons in inflorescences may be related to structural or protective functions. The presence of specific compounds only in certain parts, such as estragole in green stems, indicates localized biosynthetic activity tailored to the plant’s developmental or environmental needs. Additionally, the observed differences in fatty acids and esters content reflect the metabolic specialization of each plant part, possibly linked to energy storage or membrane structure [45,46].

The volatile compounds found in the parts of Allim tuberosum may also be categorized into sulphides, disulphides, and tetrasulphides.

As shown in Table 6, sulfur-containing compounds account for 53.12, 45.28, and 71.43% of the total volatiles of green stems, inflorescences, and stems with flower buds, respectively.

Table 6.

The content of sulfur compounds in the essential oils obtained from different parts of garlic chives.

The highest content of dimethyl trisulphide (12.84%) was found in stalks with flower buds, while the lowest content of this constituent was noted in the inflorescences (4.72%). Moreover, the stalks with flower buds had the highest content of allyl methyl disulphide (9.78%), methyl propyl disulphide (1.23%), methyl 1-propenyl disulphide (3.79%), diallyl disulphide (10.00%) and dimethyl tetrasulphide (3.05%). According to the results, the highest content of diallyl trisulphide (5.71%), allyl methyl tetrasulphide (3.17%) and diallyl tetrasulphide (0.93%) were found in the inflorescences. When comparing the methional content, it was shown that its highest value was in the inflorescences (0.89%), while its lowest value was noted for stalks with flower buds (0.31%). Although, the highest value of methyl-1-(methylthio)ethyl-disulphide was noted for the essential oil isolated from the green stems, while the lowest content of this constituent was noted in the inflorescences. Trace amounts of methyl trans-1-propenyl trisulphide (0.08%) and di-1-propenyl trisulphide (0.06%) were found in green stem oil, while diallyl sulphide (0.05%) was present only in the oil obtained from stalks with flower buds. Interestingly, di-2-propenyl tetrasulphide (0.19%) was noted only in the oil of inflorescences.

According to literature data, the characteristic odor of A. tuberosum is due to the presence of sulfur-containing flavor components.

Mnayer et al. [43] identified dimethyl disulphide (19.58%), allyl methyl disulphide (14.37%), dimethyl trisulphide (14.34%), allyl methyl trisulphide (7.24%), methyl 1-propenyl disulphide (6.07%), and diallyl disulphide (5.14%) in the essential oil obtained from bulbs of garlic chives from France. The main components of the essential oil from Allium tuberosum cultivated in Brazil were allyl methyl disulphide (25.9%), diallyl disulphide (22.5%), and dimethyl disulphide (5.3%) [42], while Pino et al. [47] found methyl propyl trisulphide (9.9%), dipropyl trisulphide (6.0%), dimethyl trisulphide (6.0%), and methyl propyl disulphide (5.5%) in volatiles from Chinese chives cultivated in Havana.

The essential oils composition detailed in this study shows some differences from previously published reports on garlic chives [42,43,47]. Dimethyl disulphide, which dominated in the essential oil from garlic chives cultivated in France [43] and in Brazil [42] was not detected in our oils. The content of components such as dimethyl trisulphide, allyl methyl disulphide, dimethyl trisulphide, allyl methyl disulphide, methyl propyl trisulphide, dipropyl trisulphide, and diallyl disulphide found in the oils from current study was lower as compared to cited literature. It can be concluded that the relative proportions of sulfur-containing compounds in garlic chives essential oil vary significantly depending on the collection places and botanical organs used for extraction.

Aliphatic aldehydes, ketones, and aliphatic hydrocarbons were found in Allium tuberosum leaves and seeds by Lopes et al. [42] and Hu et al. [48]. Moreover, the presence of other volatiles like furfuryl and furan derivatives, phenols, diterpenes, and terpenoids in different genotypes of Allium tuberosum have been confirmed by Hanif et al. [49]. However, linalool, which we found in significant amounts (3.16–8.25%) in our oils, was present in lesser amounts (1.75%) in Allium tuberosum from France [43].

This study provides valuable information on the antioxidant properties of dried Allium tuberosum, which can be used as a spice or ingredient in food products beneficial to human health. The essential oils derived from garlic chives, particularly from different parts of the plant, exhibit a diverse range of chemical compounds that contribute to their biological activities. Notably, allyl methyl trisulphide, diallyl disulphide, and dimethyl trisulphide are prominent constituents known for their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. These sulfur-containing compounds have been widely studied for their ability to inhibit the growth of various bacteria and fungi, making them valuable in food preservation and as potential therapeutic agents. Linalool, another significant component, is recognized for its calming and anti-inflammatory effects, often utilized in aromatherapy and skincare products [45,50,51]. Furthermore, the distinct aroma of garlic chives, attributed to its sulfur compounds, can enhance the flavor profile of culinary dishes, making it a valuable ingredient in the food industry. The diverse chemical composition also suggests potential applications in the agricultural sector as a natural pest deterrent, leveraging the plant’s ability to repel herbivores. Moreover, the exploration of garlic chives essential oils in pharmaceuticals could yield new formulations for anti-inflammatory or antimicrobial treatments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Field Experiment

The field experiment was conducted from 2022 to 2024 at the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin (14°31′ E, 53°26′ N), within a vegetative hall. The experimental factors were the botanical part of the plant and the plant age.

The garlic chive seeds used in the study were obtained from the commercial seed company PlantiCo, Zielonki Poland. Garlic chives were cultivated from unpotted seedlings produced in an unheated greenhouse. Untreated seeds were sown on 14 March 2022 (Season 1) into seed trays filled with a substrate based on high peat with a pH of 5.4–6.0 containing the macronutrients NPK (14–16–18) + Mg (5) at a rate of 0.6 kg/m3 and micronutrients at 0.2 kg/m3. The seedlings were subsequently transplanted on 29 April to their permanent location in perforated plastic trays measuring 60 × 40 × 24 cm, planted in nests with five seedlings per nest, at a spacing of 30 × 20 cm. Each tray contained four clumps of garlic chives. The sides of the trays were covered with black foil. The trays were filled with a light mineral soil with a pH of 6.7, in a volume of 45 L. The experiment was established in a randomized sub-block design with three replications, each consisting of five trays. In total, the study was conducted on 60 plant clumps. Nutrient deficiencies were supplemented to the level recommended for Allium cepa [52] using the multi-component fertilizer Azofoska (N 13.6, P2O5 6.4, K2O 19.1, MgO 4.5, B 0.045, Cu 0.180, Fe 0.17, Mn 0.27, Mo 0.040, Zn 0.045). In the first year of cultivation, the fertilizer was applied to each tray twice: the first application was three weeks before the planned seedling transplanting at a dose of 25 g, and the second application was four weeks after transplanting at a dose of 20 g. In subsequent years, the plants were fertilized with the same fertilizer once, four weeks after the onset of the growing season, at a dose of 20 g. Plant harvests for laboratory analyses began in the second year of cultivation, i.e., in 2023 (season 2). Every 10 days, flowering stems with buds and fully developed flowers in the inflorescences were randomly harvested separately. No leaf harvests were conducted during the growing season. In the first year of the study (season 2), the flowering stems were harvested four times: 5 September, 15 September, 20 September, and 1 October. In the second year (season 3), they were harvested six times: 15 August, 25 August, 5 September, 16 September, 25 September, and 7 October. Allium tuberosum is a perennial plant cultivated over several growing seasons. The variation in the number of harvests resulted from differences in the growing season. Older plants initiated flowering earlier and completed flowering later than younger plants. The number of harvests did not affect the laboratory evaluation, as the entire yield of inflorescences from both growing seasons of garlic chives was subjected to analysis. Properly developed inflorescence stems were harvested when approximately 75% of the flowers had developed, at a height of 5 cm above the soil surface. The harvested material was divided into flowering stems, green stems, and inflorescences.

During plant growth and development, basic maintenance practices were performed, including weeding and irrigation. In both years of the study, there was no need to apply chemical protection against diseases and pests affecting bulb vegetables. In each study year, after the end of the growing season, leaves were cut at a height of approximately 5–7 cm above the soil surface in November. The analysis of weather conditions in 2023–2024 was based on data obtained from the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management for the Hydrological-Meteorological Station IMGW in Szczecin-Dąbie (Table 7).

Table 7.

Meteorological data covering the years of research 2023–2024 (data source: https://www.ogimet.com/, accessed on 20 October 2025).

Under the climatic conditions of Szczecin, garlic chives begin producing flowering stems in July and bloom until the end of September or early October. The most intensive flowering period occurs from late July to early September. In both study years, weather conditions were favorable for the growth of this species. During flowering, air temperature and sunshine levels were at or above the long-term average. The plants flowered very abundantly. In contrast, monthly precipitation totals, compared to long-term averages, were higher in July in both study years, whereas in August and September, lower precipitation was recorded in the second year of the study.

3.2. Laboratory Analyses

Plant material analyses were carried out in three replications in the laboratories of the Department of Horticulture and the Department of Organic and Physical Chemistry at the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin. For each batch of raw material, ten parallel measurements were performed.

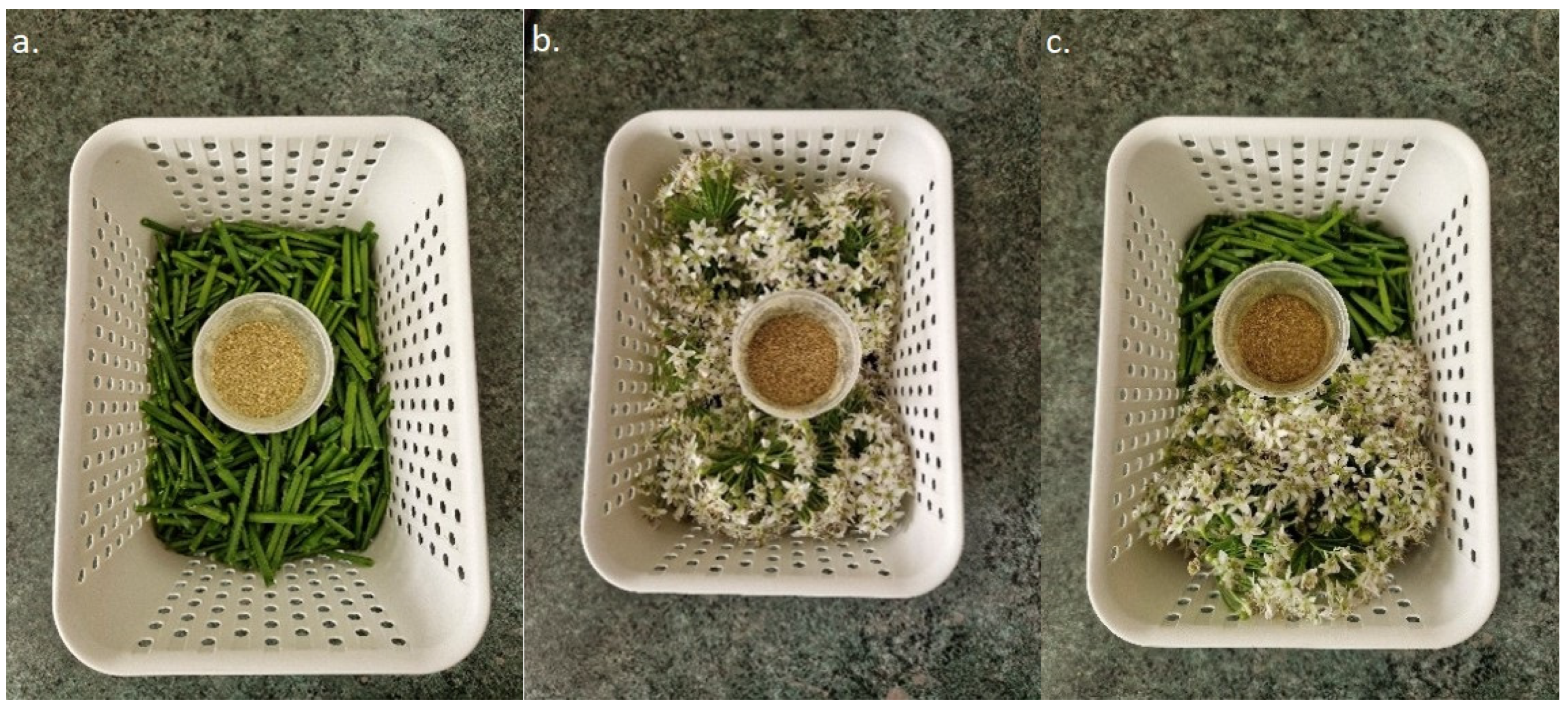

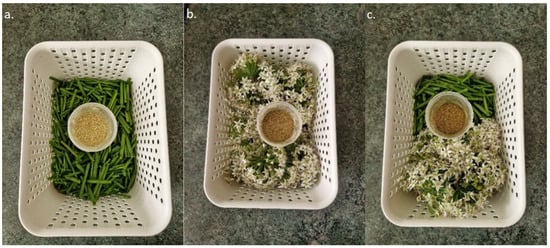

The contents of total polyphenols, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, total carotenoids, and DPPH radical scavenging activity in green stems, inflorescences, and flowering stems were determined in dried material (Figure 1). Flowering stems (35 g), green stems (30 g), and inflorescences (40 g) were dried separately using an SLN 115Eco laboratory dryer (POL-ECO, Wodzisław Śląski, Poland) at 40 °C. After drying, the material was ground using a WŻ-1 laboratory mill (Instytut Sadkiewicza, Bydgoszcz, Poland). This procedure was repeated after each harvest. Subsequently, the dried material from different plant parts was combined into composite samples from individual harvests and subjected to chemical analyses. The same procedure was applied in the second year of the study. In both years of the study, dried material with a particle size of 0.8 mm was obtained. The moisture content of the material was as follows: green stems (9.25% and 9.68%), inflorescences (11.27% and 11.60%), and flowering stems (13.35% and 12.82%).

Figure 1.

Fresh and dried plant material (a) green stems, (b) inflorescences, (c) flowering stems (photo by A. Żurawik).

Essential oils in green stems, inflorescences, and stems with floral buds were analyzed in fresh plant material collected on 25 September 2024.

3.2.1. Determination of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids

Plant material (0.5 g) was extracted with 80% acetone. The samples were ground in a mortar with a small amount of acetone and then transferred to a 50 mL volumetric flask. The residue was rinsed with acetone until the extracted material was completely decolorized. The extract was analyzed using a Helios Gamma spectrophotometer (Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, NY, USA) at wavelengths of 441, 646, 652, and 663 nm, with three replications.

The pigment content in the analyzed material was calculated using the following formulas:

where E is the extinction at the specified wavelength, V is the volume of the volumetric, and m is the mass of the sample.

3.2.2. Determination of Total Polyphenols

The total polyphenol content was determined spectrophotometrically using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, with gallic acid as the standard [53]. Plant material (1.0 g) was extracted for 30 min with 70% methanol. The cooled extract was then quantitatively transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask using methanol. The flask was stoppered and mixed thoroughly. To obtain the final extract, the sample was filtered. Using a pipette, 5 mL of the extract was transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask, and the following were added sequentially: 75 mL of distilled water, 5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and 10 mL of saturated Na2CO3 solution. The flask was filled up to 100 mL with distilled water and mixed. The sample was kept at 21 °C for 60 min in the dark. The absorbance was measured using a Helios Gamma spectrophotometer (Thermo Spectronic) at a wavelength of 760 nm.

The total polyphenol content was calculated using the formula:

where A is the weight of the plant material divided by 20 and y is the value obtained from the standard curve.

Polyphenol concentration was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100 g of dry matter (DM).

3.2.3. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the DPPH Method

The antioxidant activity of the plant material was determined using the DPPH radical scavenging method [54]. Prior to the analysis, a reagent containing the radical solution was prepared. A sample of 0.012 g DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) was weighed and quantitatively transferred to a 100 mL volumetric flask, which was then filled to the mark with methanol. The test sample was prepared in a test tube by sequentially combining: 1 mL of a fivefold diluted methanolic plant extract, 3 mL of methanol, and 1 mL of the DPPH solution. The mixture was shaken, and after 10 min the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer. The percentage of DPPH inhibition was calculated using the formula [55]:

where Ar is the absorbance of the control and At is the absorbance of the test sample.

3.3. Determination of Essential Oil Content

Separate 100 g samples of stems, inflorescences, and stems with floral buds were weighed and placed in a 1000 mL round-bottom flask with 400 mL of distilled water. The samples were subjected to hydrodistillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus (Labo24.pl, Gliwice, Poland) for 4 h, according to the method recommended in the European Pha(rmacopoeia [56], with some modifications. After this time, the condensate collected into the calibrated tube of the apparatus was extracted once with 25 mL of dichloromethane to completely recover the oil (the content of oil in the garlic chives was so small that it did not form a separate layer on the water surface). Anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to the dichloromethane to remove moisture. Next, the dichloromethane was removed by rotary evaporation at 40 °C to give light yellow oils with the characteristic chive smell. The obtained oils were stored in tightly closed vials at 4 °C until analysis. The essential oil content was determined and expressed as weight of oil per fresh material weight (%w/w).

GC–MS Analysis

GC–MS analysis of the isolated oils was realized on an HP 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with an HP-5 MS fused silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness) and directly coupled with an HP 5793 mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). Helium was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The volume of sample injected was 2 μL (20–30 mg of oil dissolved in 1.5 mL of dichloromethane) and split injection was used (split ratio 5:1). The injector and the transfer line were kept at 250 °C and 280 °C, respectively. The ion source temperature was 230 °C.

The oven temperature was raised from 50 °C to 280 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min. Mass spectra were taken at 70 eV with a mass scan range of 50–550 amu.

Solvent delay was 4 min. The total running time for a single sample was 76.76 min.

Most of the constituents were identified by comparison of their mass spectra with the spectrometer databases (Wiley NBS75K.L and NIST 2002) and by comparison of their calculated retention indices with those reported in the NIST Chemistry WebBook (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/, accessed on 15 November 2025) and literature [43,44]. The retention indices were determined in relation to a homologous series of n-alkanes (C7–C30, from Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) under the same operating conditions. Each GC–MS analysis was repeated three times.

The average values of the relative percentages of essential oil constituents were determined from the total peak area (TIC) using MSD Enhanced ChemStation G1701AA ChemStation A.03.00. software.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The results of the chemical analyses, including total polyphenols, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, total carotenoids, DPPH radical scavenging activity, and essential oils in different botanical parts of two- and three-year-old Allium tuberosum (season 2 and 3), were statistically processed using Statistica Professional 13.3 (TIBCO StatSoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and verified by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each plant part and study year. Mean values were compared using Tukey’s test at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

4. Conclusions

Allium tuberosum is a valuable plant in terms of total polyphenol content, total carotenoids, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, antioxidant activity, and essential oil content across all examined botanical parts. The inflorescences of garlic chives were particularly rich in total polyphenols and exhibited high antioxidant activity. Flowering stems, in turn, represent the best source of total carotenoids and chlorophyll a, b, and total chlorophyll. Three-year-old plants contained 11.6% more carotenoids compared to two-year-old plants. A total of 154 essential oil components were identified in the different botanical parts of garlic chives. In the volatile profile of garlic chives cultivated in northwestern Poland, sulfur-containing compounds predominated. The highest content of these compounds was recorded in the essential oil isolated from stems with floral buds (71.43%), and the lowest in the essential oil of the inflorescences (45.28%). Both two- and three-year-old garlic chives were rich sources of antioxidants and may be recommended for use in the food industry. A more comprehensive phytochemical characterization could strengthen the potential application of garlic chives as a functional food. Furthermore, to enable the commercialization of Allium tuberosum in food products, it is necessary to optimize harvesting, drying, and storage technologies to preserve its maximum antioxidant properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.Ż. and P.Ż.; methodology, A.Ż. and A.W.; investigation, A.Ż., P.Ż. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Ż. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, P.Ż. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Q. Cinese star anise (Illicium verum) and pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium) as natural alternatives for organic farming and health care—A review. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2020, 14, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Khoshkharam, M.; Cheng, Q. Caravay, Chinese chives and Cassia as functional foods with considering nutrients and health benefits. Carpath. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 13, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasee, B.; Mittraparp-arthorn, P. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activities of Fresh and Dried Chinese Chive (Allium tuberosum Rottler) Leaf Extracts. ASEAN J. Sci. Tech. Rep. 2023, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, D.; Ajiati, D.; Heliawati, L.; Sumiarsa, D. Antioxidant Properties and Structure Antioxidant Activity Relationship of Allium Species Leaves. Molecules 2021, 26, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, E.; Sabała, P. Organic and Conventional Herbs Quality Reflected by Their Antioxidant Compounds Concentration. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartip, H.; Yadegari, H.; Fakheri, B. Organic agriculture and production of medicinal plants. Int. J. Food Allied Sci. 2015, 4, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Opara, E.I.; Chohan, M. Culinary Herbs and Spices: Their Bioactive Properties, the Contribution of Polyphenols and the Challenges in Deducing Their Health Benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 19183–19202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvitković, D.; Lisica, P.; Zortić, Z.; Repajić, M.; Pedisić, S.; Uzelac-Dragović, V.; Balbino, S. Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Pigments of Mediterranean Herbs and Spices as Affected by Different Extraction Methods. Foods 2021, 10, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.A. Health Benefits of Culinary Herbs and Spices. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Trandafir, I.; Cosmulescu, S. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Nuytitional Quality of Different Culinary Aromatic Herbs. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobo. 2017, 45, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowati, W.; Ratnawati, H.; Husin, W.; Maesaroh, M. Antioxidant properties of spice extracts. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 1, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yashin, A.; Yashin, Y.; Xia, X.; Nemzer, B. Antioxidant Activity of Spices and Their Impact on Human Health: A Review. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć-Bieżanowska, R.; Piątkowska, E. Total Polyphenols and Antioxidant Properties of Selected Fresh and Dried Herbs and Spices. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Xiao, X.; Li, H.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Yu, J. Moderate Salinity if Nutrient Solution Improved the Nutritional Quality and Flavor of Hydroponic Chinese Chives (Allium tuberosum Rottler). Foods 2023, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embuscado, M.E. Spices and herbs: Natural sources of antioxidants—A mini review. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, V.M.; Dumbravă, D.G.; Raba, D.N.; Radu, F.; Moldovan, C. Spectrophotometric determination of the content of chlorophylls, carotenoids and xanthophyll in the fresh and dry leaves of some seasoning and aromatic plants from the western area of Romania. Sect. Adv. Biotechnol. 2022, 22, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, W.; Khamrui, K.; Mandal, S.; Badola, R. Anti-oxidative, physico-chemical andsensory attributes of burfi affected by incorporation of different herbs and its comparison with synthetic anti-oxidant (BHA). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3802–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, A.D.; Keum, Y.S.; Saini, R.K. A comprehensive study of polyphenols contents and antioxidant potential of 39 widely used spices and food condiments. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Yadav, S.S. A review on health benefits of phenolics derived from dietary spices. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1508–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.E.; Zhao, X.; Carey, E.E.; Welti, R.; Yang, S.-S.; Wang, W. Phytochemical phenolics in organically grown vegetables. Mol. Nutrit. Food Res. 2005, 49, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.E.; Baasanmunkh, S.; Nyamgerel, N.; Oh, S.-Y.; Song, J.-H.; Yusupov, Z.; Tojibaev, K.; Choi, H.J. Flower morphology of Allium (Amaryllidaceae) and its systematic significance. Plant Divers. 2024, 46, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaert, N.; Paepe, D.; Bouten, C.; De Clercq, H.; Steward, D.; Van Bockstaele, E.; De Loose, M.; Van Droogenbroeck, B. Antioxidant capacity, total phenolic and ascorbate content as a function of the genetic diversity of leek. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurawik, A.; Żurawik, P. Content of macro- and micronutrients in green and blanched leaves of garlic chives (Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Sprengel). J. Elem. 2015, 20, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutejo, I.R.; Efendi, E. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of garlic chives (Allium tuberosum) ethanolic extract on doxorubicin-induced liver injured rats. Int. J. Pharma Med. Biol. Sci. 2017, 6, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Niu, K.M.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, S.; Han, S.G.; Kim, S.K. Characteristics of Chinese chives (Allium tuberosum) fermented by Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2016, 59, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Pinto, J.; Gundersen, G.G.; Weistein, I.B. Effects of a series of organosulfur compounds on mitotic arrest and induction of apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mau, J.L.; Chen, C.P.; Hsieh, P.C. Antimicrobial Effect of Extracts from Chinese Chive, Cinnamon, and Cori Fructus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagishi, K.; Abe, T.; Ubukata, M.; Kato, S. Inhibition of flower stalk elongation and abnormal flower development by short-day treatment in a Japanese variety of Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Sprengel). Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.; Whiteman, M.; Moore, P.K.; Zhu, Y.Z. Bioactive S-alk(en)yl cysteine sulfoxidemetabolites in the genus Allium: The chemistry of potential therapeutic agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005, 22, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, M.K. Effect of Chlorophyll in Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum) Leaves by Drought and pH. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2022, 4, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurawik, A.; Żurawik, P. Mineral components in green stems and inflorescences of Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Sprengel. J. Elem. 2024, 29, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ašimović, Z.; Čengić, L.; Hodžić, J.; Murtić, S. Spectrophotometric determination of total chlorophyll content in fresh vegetables. Work. Fac. Agric. Food Sci. Univ. Sarajevo 2016, LXI, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczewska-Sowińska, K.; Turczuk, J. Yielding and biological value of garlic chives (Allium tuberosum Rottl. ex Spreng) depending on the type of mulch. J. Elem. 2016, 21, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caser, M.; Falla, N.M.; Demasi, S.; Nucera, D.; Scariot, V. Edible flowers of wild allium species: Bioactive compounds, functional activity and future prospect as biopreservatives. AIMS Agric. Food 2025, 10, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Wiśniewski, R. Determination of triterpenoids, carotenoids, chlorophylls, and antioxidant capacity in Allium ursinum L. at different times of harvesting and anatomical parts. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.L. Uncovering the secrets to vibrant flowers: The role of carotenoid esters and their interaction with plastoglobules in plant pigmentation. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roşan, C.A.; Bei, M.F.; Heredea, R.; Vicas, S.I. Influence of various treatments on the level of photosynthetic pigments, bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential in Allium ursinum L. leaves. Nat. Resour. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 14, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbravă, D.G.; Moldovan, C.; Raba, D.N.; Popa, M.V. Vitamin C, chlorophylls, carotenoids and xanthophylls content in some basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) leaves extracts. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2012, 18, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Nergui, S.; Deleg, E.; Chen, Y.H. The Study of the Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Compounds of Different Allium Species. Food Nutr. Sci. 2025, 16, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, T.; Kovarovič, J.; Bystrická, J.; Vollmannová, A.; Musilová, J.; Lenková, M. The content of polyphenols and antioxidant activity in leaves and flowers of wild garlic (Allium ursinum L.). Acta Aliment. 2018, 47, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furletti, V.F.; Teixeira, I.P.; Obando-Pereda, G.; Mardegan, R.C.; Sartoratto, A.; Figueira, G.M.; Duarte, R.M.T.; Rehder, V.I.G.; Duarte, M.C.T.; Höfling, J.F. Action of Coriandrum sativum L. essential oil upon oral Candida albicans biofilm formation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 985832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.; Godoy, R.L.O.; Goncalves, S.L.; Koketsu, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Sulphur constituents of the essential oil of nira (Allium tuberosum Rottl.) cultivated in Brazil. Flavour Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnayer, D.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Petitcolas, E.; Hamieh, T.; Nehme, N.; Ferrant, C.; Fernandez, X.; Chemat, F. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of six essential oils from Alliaceae family. Molecules 2014, 19, 20034–20053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.-F.; Sun, Q.; Hu, H.-B. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil from Allium hookeri consumed in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzotti, V. The analysis of onion and garlic (Review). J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Fuentes, V.; Correa, M.T. Volatile Constituents of Chinese Chive (Allium tuberosum Rottl. ex Sprengel) and Rakkyo (Allium chinense G. Don). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1328−1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.H.; Sheng, C.; Mao, R.G.; Ma, Z.Z.; Lu, Y.H.; Wei, D.Z. Essential oil composition of Allium tuberosum seeds from China. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 48, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Xie, B.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Gao, C.; Wang, R.; Ali, S.; Xiao, X.; Yu, J.; Al-Hashimi, A.; et al. Characterization of the volatile profile from six different varieties of Chinese chives by HS-SPME/GC–MS coupled with E. NOSE. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, J.; Ren, Y.-H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.-L.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Chen, X.-F.; Liu, Z.-B. Antimicrobial activity, chemical composition and mechanism of action of Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum Rottler) extracts. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1028627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamatou, G.P.P.; Viljoen, A. Linalool—A Review of a Biologically Active Compound of Commercial Importance. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grześkowiak, A. Fertilizing Vegetables in Field Cultivation; Agencja Reklamowa Endo Media: Police, Poland, 2002; pp. 66–69. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.; Rossi, J. Colorimetry of Total Phenolic Compounds with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.C.; Chen, H.Y. Antioxidant Activity of Various Tea Extracts in Relation to Their Antimutagenicity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, D.; Guerrini, A.; Maietti, S.; Bruni, R.; Paganetto, G.; Poli, F.; Scalvenzi, L.; Radice, M.; Saro, K.; Sacchetti, G. Chemical fingerprinting and bioactivity of Amazonian Ecuador Croton lechleri Müll. Arg. (Euphorbiaceae) stem bark essential oil: A new functional food ingredient? Food Chem. 2011, 126, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2019; p. 307.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.