Abstract

Nystatin is a polyene macrolide antibiotic with broad-spectrum antifungal activity and serves as a key therapeutic agent for superficial fungal infections. This review systematically elaborates on its multicomponent chemical nature, its mechanism of action targeting ergosterol, and highlights the potential adverse effects, such as cardiotoxicity, associated with impurities like RT6 (albonoursin). The fundamental analytical techniques for quality control are outlined. Furthermore, the clinical applications and combination therapy strategies of nystatin in treating oral diseases, vaginitis, and otitis externa are summarized in detail. Regarding biosynthesis, the assembly mechanism of nystatin A1 via the type I polyketide synthase pathway and its subsequent modification processes are thoroughly discussed. Emphasis is placed on the latest advances and potential of gene-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, in the targeted knockout of genes responsible for toxic components and in optimizing production strains to enhance nystatin yield and purity. Finally, this review prospects the future development of nystatin towards improved safety and efficacy through structural optimization, innovative delivery systems, and synthetic biology strategies, aiming to provide a reference for its further research and clinical application.

1. Introduction

Microbial secondary metabolites, characterized by their distinctive structures, diverse bioactivities, and wide-ranging sources, are vital resources for the advancement of therapeutic antibiotics [1]. Agents including macrolides (erythromycin), β-lactams (penicillin), aminoglycosides (streptomycin), and glycopeptides (vancomycin) have proved crucial in combating numerous bacterial illnesses [2]. Subsequent to the golden era of antibiotic discovery from 1940 to 1960, there was a notable decline in the rate of development, while the increasing menace of pathogenic drug resistance has intensified the demand for novel antibiotics [3]. During this period, semisynthesis—the chemical modification of natural products—emerged as the principal method for developing new antibiotics. Nonetheless, it proved beneficial exclusively for a restricted range of scaffold types, comprising cephalosporins, penicillins, quinolones, and macrolides. Moreover, the intricate architecture surrounding natural products sometimes hinders site-selective alteration or offers only restricted changeable regions, rendering semisynthetic methods increasingly inadequate [4,5]. Consequently, innovative discovery paradigms and methodologies are essential to acquire compounds with exceptional skeletal structures [6].

Polyene antibiotics, also known as polyene macrolide antibiotics (PEMs), are antifungal drugs distinguished by conjugated double bonds and produced by particular actinomycetes and fungi [7]. The primary representations are amphotericin B, nystatin and mandeliopepin [8]. Amphotericin B is a quintessential polyene macrolide antibiotic employed for severe systemic fungal infections [9]. Owing to its high toxicity, it must be administered intravenously, while renal function and electrolytes are monitored to mitigate side effects [10]. Nystatin is structurally similar to amphotericin B, and its biosynthesis-related gene clusters are significantly conserved [11]. Intravenous liposomal nystatin treatment maintains 60% of Candida infections resistant to amphotericin B or fluconazole within the susceptible range, demonstrating equivalent efficacy against candidemia as well as Aspergillus and Cryptococcus infections [12].

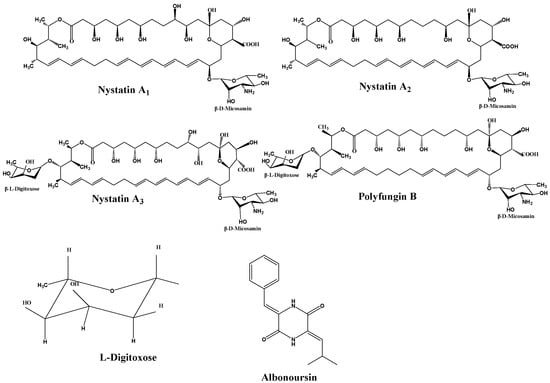

Nystatin is a polyene macrolide antibiotic consisting of 38 members, whose chemical formula is C47H75NO17. The extensive macrocyclic lactone core has three to seven conjugated double bonds, imparting distinctive UV maxima and antifungal properties [13]. The structure also includes an exocyclic carboxyl group, a mycosamine molecule, and a hemiketal moiety. In 1950, Hazen and Brown initially extracted nystatin from cultures of the soil bacterium Streptomyces noursei. Simultaneously, researchers in China extracted a similar compound from Streptomyces sp. (Norse actinomycetes) sourced from Guangdong Province, designating it as nysfungin [14]. Foreign nystatin mostly consists of nystatin A1, a variant that exhibits high efficacy against many fungi, including Candida albicans and Aspergillus species. It exhibits minimal cardiotoxicity in clinical applications, rendering it appropriate for the treatment of localized and gastrointestinal mycoses. Chinese nystatin consists of nystatin A1 (2.12–15.56%), nystatin A3 (27.22–53.52%), Polyfungin B (19.13–39.83%), and an undetermined component RT6 (~10%) [15] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural formulas of components.

In the first stages of development, domestic researchers sought nystatin as a generic alternative to “nystatin”. Further analyses indicated significant compositional differences between the Chinese product and worldwide nystatin. Thus, the domestic formulation was named “nysfungin” to differentiate it from the reference chemical. The distinguishing characteristics are encapsulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of structure and physicochemical properties of domestic and international nystatin.

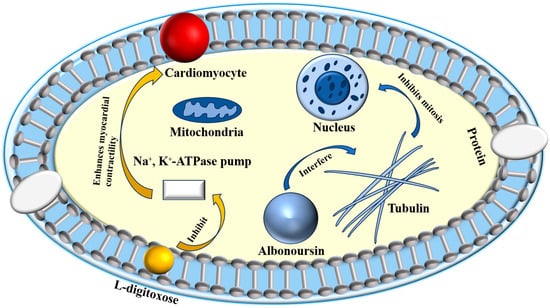

Research has identified the previously unknown component RT6 as albonoursin, a chemical initially extracted from nystatin, which has subsequently been shown to exhibit no antifungal action [18]. Nystatin A3 and Polyfungin B both possess the structural motif L-digitoxose [19]. Digitoxose inhibits the Na+, K+-ATPase pump in cardiomyocytes, hence augmenting contractile force (positive inotropy). Concurrently, its negative chronotropic and dromotropic effects reduce heart rate and obstruct atrioventricular conduction [20]. These properties underlie its clinical utility in congestive heart failure. Digitalis glycosides possess a narrow therapeutic index and significant inter-individual variability, requiring stringent therapeutic medication monitoring to prevent digitalis toxicity, which can lead to a life-threatening arrhythmogenic condition [21]. It has been postulated that the L-digitoxose moiety within nystatin A3 and Polyfungin B may confer analogous cardiotoxic liability, precipitating dysrhythmias. Consequently, heightened vigilance is mandated during clinical use, particularly in patients at elevated risk for digitalis toxicity; proactive surveillance and readiness to manage cardiac adverse events are essential to ensure patient safety. Albonoursin is an antibacterial and antitumor dehydrocyclic dipeptide compound that belongs to the class of 2,5-diketopiperazine derivatives [22]. Research indicates that 2,5-diketopiperazines inhibit tubulin polymerization, interfere with proper mitosis, and exhibit fatal consequences [23]. This toxicity may correlate with persistent cell destruction and could potentially encourage excessive proliferation, suggesting a possible connection to malignant transformation. Structural analysis demonstrates that both amino acid residues in albonoursin experience α, β-dehydrogenation, hence augmenting its cytotoxic potency [24]. While no research has conclusively proven toxicity in humans, clinical caution necessitates that medications containing albonoursin be administered judiciously to those seeking conception or who are pregnant, to mitigate potential reproductive hazards (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Toxic mechanisms of L-digitoxose and albonoursin.

Despite its relatively considerable toxic side effects, nystatin remains one of the most essential antifungal agents in clinical practice due to its potent, broad-spectrum activity and low resistance rate [25]. Notwithstanding its significant toxic side effects, nystatin is a crucial antifungal drug in clinical practice owing to its powerful, broad-spectrum efficacy and low resistance rate [26,27,28]. Progress in biosynthetic research and the advent of gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 have facilitated the execution of targeted gene knockouts to eliminate detrimental components in nystatin and its derivatives, thereby improving the yield of nystatin A1 [29]. These advancements create new opportunities for the manufacturing, optimization, and utilization of these antifungal drugs.

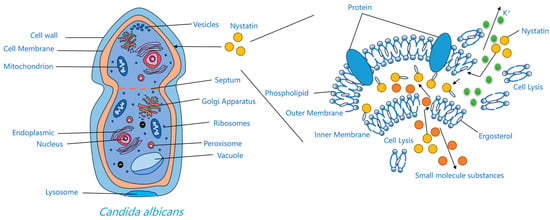

The interaction between nystatin A1 and ergosterol in fungal cell membranes arises from the higher number of double bonds in its ring structure compared to cholesterol in human membranes, leading to relative selectivity [30]. This relative selectivity enhances its antifungal activity, although it also accounts for the associated hemolytic and nephrotoxic side effects [31]. Upon binding to ergosterol, the drug molecule induces size-selective transmembrane pores in the membrane, resulting in osmotic imbalance and significantly increasing permeability to small solute molecules while having little effect on larger ones [32]. These channels result from hydrophobic interactions between the polyene chain and membrane sterols, undermining the barrier and electrochemical gradients. Consequently, potassium and other essential ions are lost, glycolysis is impaired, and the cell perishes [33,34]. The thermodynamically optimal arrangement entails the hydrophobic tail directly interacting with ergosterol in the lipid membrane, and the hydrophilic chain is oriented towards the aqueous channel environment [30]. The pore-forming concept continues to be the primary explanation for the activity of polyenes. Alternative concepts—half-pore, surface adsorption, and the sterol-sponge hypothesis—have been suggested; nevertheless, the sterol-sponge model remains devoid of definitive pharmacological and toxicological validation [35]. Furthermore, oxidative stress induced by polyenes, leading to DNA damage, protein carbonylation, and lipid peroxidation, has been suggested to promote fungal cell death [36]. Regardless of the approach, binding to ergosterol is the essential prerequisite for the efficiency of polyene antifungals [30] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mechanism diagram of action of nystatin A1.

Nystatin A1 demonstrates significant efficacy against Candida spp., notably suppressing Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp., Mucorales, and Blastomyces dermatitidis. Nystatin A1 also demonstrates therapeutic efficacy against specific protozoal or parasitic diseases [37]. It is utilized clinically for superficial candidiasis, including gastrointestinal candidiasis and vaginitis, as well as for leishmaniasis [38,39,40], demonstrating favorable outcomes in combination regimens [41,42]. Formulations containing nystatin A1 are available in the forms of powders, suppositories, ointments, pills, and capsules, taken orally, topically, or via irrigation. Contemporary research concentrates on nano-capsule hydrogels [43], liposomes, and alginate microparticles [44] to expand its delivery options and clinical utility.

Nystatin, a secondary metabolite derived from Streptomyces, is manufactured industrially at a cost that is inversely related to the titer attained by the generating strain. Classical strain enhancement depends on successive cycles of random mutagenesis combined with high-throughput screening, succeeded by statistical optimization of medium composition and fermentation conditions [45,46,47]. The comprehensive understanding of the nystA biosynthetic gene cluster and its transcriptional circuitry has rendered rational genetic engineering the primary method for yield increases. Cluster-embedded, pathway-specific regulators modulate flow by interacting with the promoters of biosynthetic genes. In nystatin, only a limited number of regulators, such as the TetR-type activator NysRI, are identified, and their overexpression often increases output by less than twofold [48]. In contrast, pleiotropic regulators (γ-butyrolactone receptors, two-component systems) and quorum-sensing signaling networks that synchronize morphological differentiation with secondary metabolism have significantly more potential for simultaneously enhancing cellular fitness and nystA expression [49]. Nystatin, at the metabolic level, is a type I polyketide whose backbone assembly is driven by malonyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA. The existence of numerous biosynthetic gene clusters vying for the same precursors creates a significant bottleneck in precursor availability. Thus, intracellular overproduction of CoA esters, external supplementation of small-molecule precursors, or the deletion of essential genes in competing pathways can significantly alleviate carbon shortage. In Streptomyces hygroscopicus, the deletion of the tetramycin activator ttmRIV or the PKS gene ttmS1 eliminates tetramycin production. The deletions increase nystatin titers by 1.1-fold and 10-fold, respectively, offering direct evidence that eliminating a competitive pathway enhances the targeted product [50,51].

2. Determination of Nystatin Components

Nystatin is a multifaceted antibiotic; first assays depended on microbiological potency assessment, a process encumbered by numerous steps, extended incubation, and various causes of variability. Subsequently, ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry (UV-Vis) was employed. However, this method is hindered by inadequate specificity and a limited quantitative range, preventing precise quantification of deleterious congeners. Currently, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is the preferred approach, providing exceptional specificity, precision, and an extensive linear dynamic range that enables dependable resolution and quantification of nystatin components. A comparative overview of these techniques is provided in Table 2. Due to strain selection, maintenance, and minor process variations potentially causing fluctuations in measured content, rigorous management controls are essential during normal manufacturing.

Table 2.

Comparison of determination methods for penicillin content.

2.1. Improvement of Microbial Assay Method

The standard procedure for determining nystatin content predominantly uses the microbiological assay. This method employs the diffusion characteristics of antibiotics in agar media, assessing the widths of inhibition zones produced by standard and test samples against susceptible microbes to determine sample potency. Nystatin, a polyene antibiotic, effectively inhibits fungal growth, facilitating quantitative investigation of its antifungal effectiveness against particular fungal strains. The tube-disk approach has many significant limitations: procedural complexity necessitating multiple technical steps, extended incubation durations, and indistinct inhibition zone boundaries when employing Saccharomyces cerevisiae as the test organism. These variables combined undermine measurement accuracy and render the approach insufficient for modern hospital preparation quality control, which necessitates both precision and swift turnaround times [52].

To address these limitations, investigators have introduced a series of refinements to the conventional assay. Shen enhanced the measurement of nystatin and its tablets by altering the medium formulation, employing the strain ATCC 9763, and establishing the antibiotic concentration range at 10–50 U·mL−1 [53]. The phosphate buffer was adjusted to pH 6.0, and incubation occurred at 28 °C for 22 h. The revised methodology furnishes the test organism with sufficient carbon and nitrogen substrates and delivers crucial enzymatic activators for microbial metabolism. As a result, it generates distinctly defined, stable inhibitory zones devoid of secondary fronts, and zones at both elevated and diminished concentrations may be quantified instrumentally. Wang et al. developed a more efficient potency assay for polyene antibiotics by modifying the test organism, medium composition, incubation temperature, and duration [54]. This method improves reliability and operability and has been established as the standard calibration procedure for the batch replacement of the national nystatin reference standard.

The enhancements to the traditional microbiological potency assay have yielded significant results. Post-optimization, the inhibition zones display distinctly defined borders that facilitate exact instrumental measurement, resulting in correct outcomes and offering a more efficient and dependable technical method for nystatin quantification.

2.2. Ultraviolet-Visible Spectrophotometry

UV-Vis is extensively utilized for nystatin quantification because of its operational simplicity, speed, and satisfactory accuracy. Nystatin demonstrates peak absorption at 304 nm or 319 nm; assessing absorbance at this specific wavelength facilitates the quantification of its concentration [55]. The process involves the production of standard and test solutions with known concentrations, succeeded by spectrophotometric measurement at the maximum absorption. The absorbance ratio of the standard to the sample is utilized to determine the concentration and content of nystatin.

A multitude of researchers have corroborated and enhanced this methodology. Li et al. measured nystatin in nystatin oil at 304 nm, demonstrating exceptional linearity within the range of 7.2–16.8 μg mL−1 [56]. The average recovery was 100.131% ± 0.871% with a relative standard deviation of 0.870%, validating the method’s simplicity, efficiency, and high reproducibility. Ibrahem and Rashid presented two spectrophotometric techniques for pure nystatin and its formulations [57]. A method involves the condensation of vanillin with alkali to produce a yellow Schiff base. The alternative method oxidizes nystatin using an excess of bromate-bromide in an acidic medium, thereafter reacting the residual oxidant with crystal violet to produce a blue chromophore. Mohamed et al. presented an innovative green spectrophotometric method—Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD)—for the quantification of nystatin in both bulk and dose forms [58]. The method employs a straightforward mathematical transformation on the excipient-masked zero-order spectrum. A built-in Fourier wavelet performs deconvolution, and nystatin’s deconvoluted amplitude is quantified at 320 nm. A linear range of 1–25 μg·mL−1 was established; the method is straightforward, expeditious, and suitable for nystatin testing in pharmaceutical and laboratory formulations. Jiang formulated nystatin ointment utilizing Simple Ointment No.2 as the basis and quantified the medication UV-Vis according to protocol [59]. The stability assessment indicated a λmax of 304 nm, a mean recovery of 100.67% (RSD 0.56%), and approximately three months of stability under refrigeration. Zeng et al. noted that while analyzing nystatin vaginal pills by UV-Vis with methanol as the solvent and without filtration, the recovery rate surpassed 98% [60]. Lemus Gallego and Pérez Arroyo integrated UV-Vis with derivative and multivariate calibration techniques to concurrently quantify hydrocortisone, nystatin, and oxytetracycline in synthetic and pharmaceutical formulations [61]. The methods demonstrated excellent linearity, accuracy, and precision without necessitating a separation step, making them appropriate for the quantitative analysis of complex mixtures.

UV-Vis provides operational simplicity, speed, and minimal instrumental demands, rendering it appropriate for swift screening and initial quantification. Nonetheless, its specificity is rather low, and interference from other components is probable; hence, the approach is most effectively utilized on highly pure materials or for preliminary investigations.

2.3. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

HPLC is a very effective separation method that utilizes variations in partition coefficients between the stationary and mobile phases. Upon dissolution in the mobile phase, the sample is propelled through a column filled with the stationary phase; due to the unique partition coefficients of each component, their migration velocities vary, resulting in separation. A C18 column is commonly utilized, with the mobile phase including acetonitrile and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate. Qualitative and quantitative investigations of nystatin components are conducted by evaluating retention duration and peak area [62].

HPLC has been widely utilized for the analysis of nystatin. Li et al. utilized high-performance liquid chromatography to quantify nystatin concentration and assess the stability of nystatin liniments formulated in various carriers [63]. Liniments were composed of 0.9% sodium chloride, 2.5% sodium bicarbonate, glycerol suppository solution, and pure glycerol, with each group further split for observation. The results indicated that the 2.5% sodium bicarbonate formulation was unstable, whereas the other three vehicles exhibited negligible content variation over four weeks and were interchangeable. Consequently, a 2.5% sodium bicarbonate solution is inappropriate as a substrate for nystatin liniment. Abdelrahman et al. isolated nystatin by HPLC on a C8 column utilizing isocratic methanol–0.05% SDS (40:60, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL·min−1, 25 °C, and detection at 220 nm [64]. Linearity was confirmed within the ranges of 5–50, 4–50, and 4–40 µg·mL−1, with nystatin eluting at 3.52 min.

Elsharkawy et al. improved the HPLC method for the concurrent quantification of nystatin in industrial effluent samples through an experimental design approach [65]. A full-factorial screening design was utilized for chromatographic variables, succeeded by optimization through a central composite design, to determine the ideal circumstances for achieving maximum resolution between adjacent peaks within a runtime of under 5 min. The experimental findings revealed a linear range of 1.00–25.00 μg·mL−1 for nystatin, and the proposed methodology was effectively utilized for the measurement of the target pharmaceutical chemicals in rinse wastewater samples. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS) integrates the separation proficiency of HPLC with the heightened sensitivity and selectivity of mass spectrometry, facilitating accurate identification and quantification of constituents in nystatin. Chang et al. utilized HPLC-MS to determine the structural components of nystatin and to estimate their possible toxicity [17]. The experimental results demonstrated that the primary components and their concentrations varied between the two. Nystatin, nystatin A3, and Polyfungin B possess the structural motifs L-digitoxose, perhaps linked to cardiotoxicity, and 2,5-diketopiperazine, which may influence reproduction.

HPLC facilitates the effective separation of several components of nystatin, such as nystatin A1, A3, and Polyfungin B, enabling the investigation of intricate matrices. However, in comparison to UV spectrophotometry, it incurs greater expenses due to the necessity for specialized equipment and skilled workers. Despite this limitation, HPLC provides significant benefits in compositional analysis, quality control, and stability studies of nystatin, offering crucial technical assistance for the development and implementation of nystatin-related products.

3. Clinical Applications of Nystatin

3.1. Nystatin for the Treatment of Oral Diseases

Nystatin demonstrates antifungal properties that successfully inhibit fungal proliferation and is frequently utilized in the treatment of oral conditions. Rinsing with nystatin solution preserves oral hygiene and diminishes fungal colonization [66]. Chlorhexidine mouthwash exhibits significant antifungal effectiveness. Liu indicated that the combination of nystatin solution and compound chlorhexidine mouthwash significantly reduced candidal counts and inflammatory indicators in post-orthodontic patients with Candida [67]. This combination enhanced therapeutic efficacy compared to chlorhexidine alone.

Deng et al. assessed the efficacy of nystatin combined with honey in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in patients with leukemia [68]. Honey, abundant in fructose, vitamins, and amino acids, serves as a natural sweetener, facilitates wound healing, and reduces the risk of infection. The research indicated that the amalgamation of nystatin and honey reduces both the frequency and intensity of OM, mitigates patients’ adverse feelings, and consequently possesses significant clinical promoting potential.

Yan et al. assessed the concurrent administration of nystatin tablets and Kangfuxin solution in individuals following affected third-molar extraction [69]. The findings indicated that this regimen significantly decreases the occurrence of oral infections, preserves oral microbial homeostasis, and adjusts the Th17/Treg immunological balance, hence improving patients’ antibacterial and anti-infective abilities.

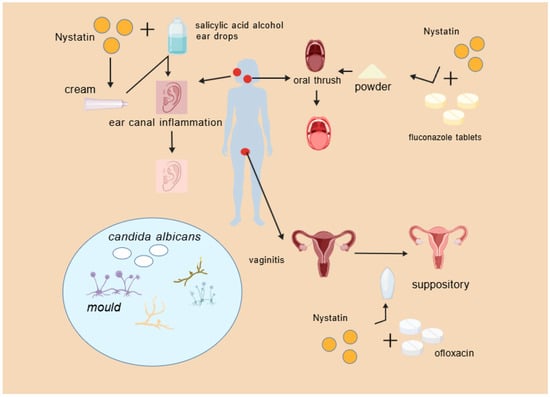

Candida albicans is the primary causative agent of thrush [70], and antifungal medications like nystatin and miconazole are commonly employed as topical treatments. Studies indicate that the combination of topical fluconazole and nystatin ointment significantly surpasses the efficacy of fluconazole administered alone. The combination enhances efficacy, reduces adverse effects, shortens treatment duration, and improves outcomes in affected children [71].

Furthermore, Paiva et al. indicated that the essential oil of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) demonstrates both fungistatic and fungicidal properties against oral yeasts [72]. The amalgamation of this botanical drug with nystatin exhibits potential antifungal effectiveness against isolates from oncologic patients, indicating that simultaneous administration of this phytotherapeutic preparation may augment antimicrobial results in individuals undergoing nystatin treatment.

Nystatin exhibits significant antifungal effectiveness in the management of oral illnesses. The simultaneous application of sodium bicarbonate, honey, or Kangfuxin solution enhances efficacy while reducing costs and adverse effects. Co-administering nystatin with natural remedies such as essential plant oils presents a novel treatment approach.

3.2. Nystatin for the Treatment of Vaginitis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is an endogenous infection induced by Candida species, predominantly Candida albicans [73]. The prevailing clinical protocol often utilizes sequential therapy, commencing with nifuratel-nystatin vaginal soft capsules, succeeded by Lactobacillus vaginal capsules [74]. This technique demonstrates some effectiveness; nonetheless, recurrence is common, requiring additional investigation into more potent therapy strategies.

The simultaneous intravaginal application of fluconazole tablets and nystatin vaginal suppositories for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) has been assessed [75]. The research indicated that the combination swiftly mitigated local symptoms and markedly improved overall therapeutic effectiveness. Further investigations indicated that a triple therapy regimen consisting of nystatin, fluconazole tablets, and Lactobacillus vaginal capsules had a 96.4% cure rate in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis, with a mere 3.6% recurrence rate [76]. These data validate that nystatin successfully eliminates Candida species and reinstates vaginal microbial equilibrium, highlighting its essential function in the therapy of VVC.

Wang assessed the therapeutic efficacy of nifuratel-nystatin vaginal soft capsules versus miconazole nitrate suppositories in the treatment of vaginitis by analyzing oxidative stress markers, inflammatory indicators, and unpleasant effects [77]. The findings demonstrated that nifuratel-nystatin vaginal soft capsules outperform miconazole nitrate suppositories in mitigating inflammatory responses, decreasing oxidative stress, and relieving clinical symptoms, hence, justifying wider clinical usage.

Xie and Li established that the combination of nifuratel-nystatin vaginal capsules and ornidazole suppositories for trichomonal vaginitis more effectively maintains immune homeostasis, reduces inflammation, enhances microcirculation, and significantly decreases recurrence rates compared to ornidazole alone [78]. While ornidazole suppositories effectively suppress Trichomonas and anaerobic bacteria, they also quickly promote the development of resistance. Nifuratel-nystatin vaginal capsules safeguard Lactobacillus, impede microbial glycolysis, reestablish normal vaginal pH, and improve self-cleansing mechanisms. Nifuratel, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, eliminates infections and inhibits their growth; its combined use markedly enhances treatment efficacy.

Researchers have assessed the sequential protocol of Honghe Fujie vaginal wash in conjunction with nifuratel-nystatin vaginal soft capsules, succeeded by Lactobacillus vaginal capsules for the treatment of mycotic vaginitis. The results indicated that this combination swiftly alleviates clinical symptoms, regulates vaginal micro-ecology, decreases CRP and PCT levels, minimizes recurrence rates, and demonstrates a high safety profile, thus providing a novel strategy for the management of mycotic vaginitis [79].

3.3. Nystatin for the Treatment of Otitis

Fungal external otitis is an infectious condition resulting from fungus infiltrating the external auditory canal, with heightened susceptibility occurring when human immunity diminishes or the canal’s epidermis is compromised [80]. Clinical signs include pruritus, discomfort, aural fullness, little watery discharge, and, in severe instances, auditory impairment [81]. Pathological studies demonstrate that the condition is primarily attributable to Aspergillus, Candida, or mixed fungal-bacterial infections. Topical antifungal treatments constitute the primary treatment; frequently utilized medications include nystatin, ketoconazole, and clotrimazole. Woods and Saliba established that nystatin does not induce hearing loss or cochlear hair-cell damage in guinea pigs, hence affirming its safety [82]. Furthermore, it has been documented that oral nystatin suspension, when provided biweekly, can effectively treat fungal external otitis, with observable improvement within three weeks [83].

Clotrimazole ointment, a commonly utilized antifungal, is effective against Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus species in fungal external otitis. The constricted, innervated canal makes cotton-bud application unpleasant, reduces compliance, and leaves hidden foci unaddressed, promoting recurrence. Nystatin powder, administered via insufflation, prevents direct touch, enhances coverage, eradicates untreated niches, and increases both compliance and efficacy. Yang established that endoscopic insufflation of nystatin powder results in significant mycological clearance, minimal recurrence, substantial reduction in inflammation, and rapid symptom alleviation, all while maintaining safety and simplicity [84]. Wang et al. noted favorable results when nystatin cream was uniformly administered to the canal, succeeded by 2% salicylic-acid alcoholic drops once symptoms diminished [85].

Nystatin powder provides specific benefits in treating fungal external otitis, especially when administered with otoscopic supervision, thus improving therapeutic effectiveness and patient adherence (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Nystatin combination drug scenario.

4. Biosynthesis of Nystatin

4.1. The Biosynthetic Process of Nystatin

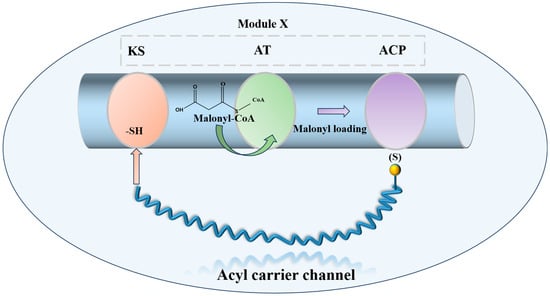

Combinatorial biosynthesis is a research approach that generates structural variety in natural products by substituting, augmenting, or altering biosynthetic genes. Progress in polyketide synthase (PKS) mechanisms has stimulated enzyme reengineering approaches. This involves inserting or deleting PKS modules to modify chain length, exchanging modules or domains to alter building blocks, and customizing domains, such as β-keto reductases, to adjust skeleton decorating. All these methodologies seek to generate additional molecules with innovative scaffolds, thus augmenting the repository for the identification of novel antibiotic agents. The polyene macrolide antibiotic nystatin A1 is synthesized by a type I PKS with a modular structure that includes the standard β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains [86,87] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the minimal functional unit of Type I PKS extension module.

In A1 biosynthesis, the AT domain of the loading module NysA selectively loads malonate onto the neighboring ACP, followed by decarboxylation catalyzed by KS, which produces the initial acetyl unit. The elongation modules then perform Claisen-type condensations that integrate fifteen malonyl-CoA and three methylmalonyl-CoA extender units. The thioesterase (TE) domain facilitates the release of the macrolactone core, subsequently allowing tailoring processes to transform the linear polyketide into nystatin A1 [88]. Post-PKS alterations include mycosamine glycosylation, hydroxylation at C-10, and the oxidation of the C-16 exocyclic methyl to a carboxyl group [89,90,91] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Biosynthesis pathway of nystatin.

The trehalose amine glycosylation of nystatin A1 is regulated by NysDIII, NysDII, and NysDI, occurring at the C19 position. The first stage of glycosylation involves the enzyme GDP-mannose-4,6-dehydratase, encoded by NysDIII, which catalyzes the transformation of GDP-mannose into GDP-4-keto-6-deoxymannose. Thereafter, through the action of an isomerase, the molecule autonomously converts to 3-keto-6-deoxy-GDP-mannose. Subsequently, facilitated by NysDII, an amidation reaction transpires, resulting in the synthesis of GDP-trehalose amine. The trehalose amine is ultimately linked to the macrolide backbone via a deoxy sugar component, facilitated by the glycosyltransferase encoded by NysDI. Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases catalyze the carboxylation, epoxidation, and hydroxylation of the polyene macrolide polyketide backbone. The P450 monooxygenases encoded by NysN and NysM facilitate the transfer of electrons from NADH, converting the oxidation group at the C16 position to a carboxyl group, whereas NysL catalyzes the hydroxylation at the C10 position.

4.2. Combinatorial Biosynthesis of Nystatin

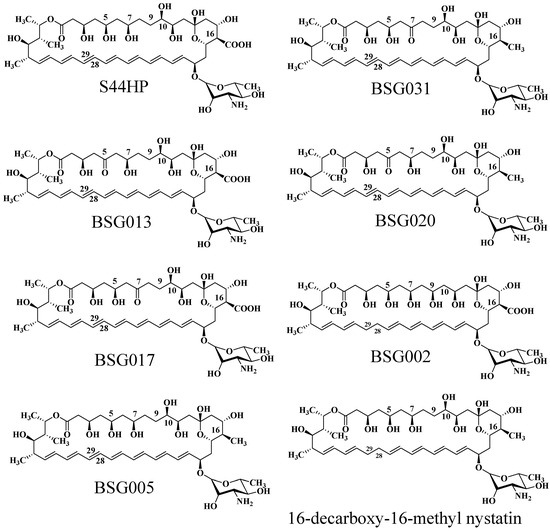

Researchers employed combinatorial biosynthesis to focus on three specific areas of nystatin: the C-28/C-29 polyene segment, the C-16 exocyclic carboxyl group inside the macrolactone, and the C-5/C-7/C-9/C-10 polyol domain, resulting in a variety of optimal derivatives.

Brautaset et al. investigated the biosynthesis mechanism of nystatin through polyketide synthase and designed a sequence of biosynthetic domains within this pathway [92]. Researchers initially deleted the C-terminal region of the KR domain in module 4 of NysC, the ACP domain, and the entirety of module 5, resulting in the mutant strain ERD48, which synthesized the hexaene nystatin derivative S48HX. This approach markedly diminished both yield and biological activity. Through the examination of ER5 domain inactivation inside the NysC module, the ERD44 mutant strain was generated, resulting in the heptaene nystatin derivative S44HP. This chemical exhibits superior solubility, and experimental findings indicate that its biological activity significantly exceeds that of nystatin [93]. Researchers demonstrated that two amino acid changes in the ER5 domain of the NPP PKS NppC transform the heptaene core, resulting in the new antibiotic NPPB1 with significantly enhanced pharmacokinetics [94]. In the polyol sector of S44HP, the C-5 or C-7 carboxyl groups were substituted with keto functions [95]. Targeted alterations were incorporated into KR17 and KR16 of NysJ, resulting in BSG013 and BSG017, respectively. In comparison to S44HP, BSG013 showed a two-fold reduction in antifungal activity and a one-fold drop in hemolytic activity, whereas BSG017 displayed a four-fold decrease in antifungal activity and a one-fold reduction in hemolytic activity. Researchers later altered the NysN domain by substituting the carboxyl group with a methyl group at position C16, resulting in BSG020 and BSG031. These compounds exhibited improved antifungal efficacy and less hemolytic toxicity; however, their exceedingly low yields significantly constrained more testing. Brautaset et al. substituted the histidine in the DH15 module of PKS NysJ, resulting in the mutant NJDH15 [95]. The C-5/C-7 keto-analogues BSG013/BSG017 exhibited diminished activity and reduced hemolytic potential, while the C-9/C-10 hydroxyl-modified BSG002 demonstrated significant declines in both activity and titer. In the C-16 carboxyl region, the mutant 16-DecNys exhibited reduced hemolysis but insufficient production. The C16 methyl position in the structure of S44HP was replaced with a carboxyl group, resulting in the formation of 16-decarboxy-16-methyl-28,29-dihydroxynystatin (BSG005). In comparison to S44HP, BSG005 exhibits a notable enhancement in yield, attaining 40% of that of S44HP, accompanied by a 1.5-fold decrease in hemolytic activity. In comparison to the analogous product 16-DecNys, the yield of BSG005 has increased twentyfold. BSG005 demonstrates antifungal activity that is twice that of S44HP and twenty times that of nystatin, suggesting that the medication retains significant antifungal efficacy while minimizing hemolytic effects. The augmented yield additionally facilitates further investigation and application.

Researchers inactivated the nysL cytochrome P450 gene inside the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster, successfully producing 10-deoxynystatin [89]. The MIC50 of this compound against Candida albicans was assessed, revealing that its inhibitory efficacy is equivalent to that of nystatin, suggesting that the hydroxyl group at the C10 position does not substantially influence nystatin’s activity against Candida albicans. Consequently, Brautaset et al. altered the nysL gene and incorporated it into the S44HP fermentation strain, resulting in the synthesis of a novel compound, BSG022 [95]. In comparison to S44HP, BSG022 had comparable biological activity; however, its HC50 value was reduced, signifying an enhancement in hemolytic toxicity. This result indicates that the hydroxyl group at the C10 position has a negligible influence on the antibacterial efficacy of the antibiotic; however, it may exert some effect on hemolysis (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The molecular structure of natamycin analogs produced through biosynthetic engineering.

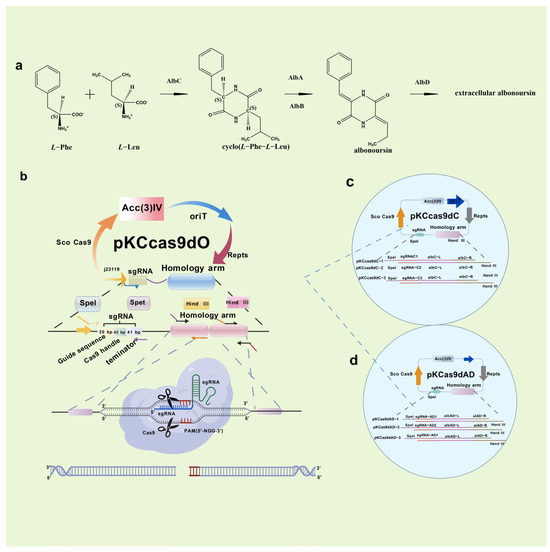

5. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Streptomyces

Gene-editing technology, a pivotal domain in contemporary analytical biology, is essential for investigating gene function. In the last 15 years, gene-editing methods utilizing designed nucleases have experienced three major advancements: zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) [96], transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [97], and the CRISPR/Cas system. The fundamental mechanism of these three systems is based on a DNA recognition domain and a DNA cleavage domain [98]. In contrast to the CRISPR/Cas system, ZFN and TALEN technologies are constrained in their applicability because of their intricate procedures, protracted assembly, and elevated prices.

In 2013, the CRISPR/Cas system—A groundbreaking genome-editing technology—was utilized in mammalian cells, garnering global interest [99]. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing is a mechanism originating from the bacterial adaptive immune system that facilitates accurate genetic alteration via RNA-directed DNA cleavage. A solitary plasmid containing the sgRNA specific to the target gene, the Cas9 gene, and the homologous arms next to the target locus is inserted into Streptomyces. The produced sgRNA directs the Cas9 protein to cleave the target gene, facilitating gene knockout through homologous recombination with the neighboring arms [100,101]. The genome of Streptomyces is the largest among all known prokaryotic organisms and possesses a high GC content (typically exceeding 70%), rendering genetic manipulation of the Streptomyces genome more complex than that of other model organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The existing genetic manipulation techniques for Streptomyces are constrained, mostly depending on conventional site-specific recombination systems such as Cre/loxP, Dre/rox, Flp/FRT, and lnt-Xis. Nonetheless, these methodologies typically exhibit numerous issues, including intricate procedures, prolonged testing durations, and diminished efficiency. The CRISPR/Cas9 technology facilitates highly effective, locus-specific genome editing, encompassing insertion, repair, and replacement procedures [102,103].

In 2014, Cobb initially employed CRISPR/Cas9 in Streptomyces lividans, excising the 31 kb undecyl prodigiosin biosynthetic gene cluster [104]. He et al. subsequently created the pKCcas9dO method, attaining 60–100% efficiency for single or multi-gene knockouts [105]. The selection of sgRNA and the composition of the medium significantly affected efficiency. In 2019, Mo et al. developed pMWCas9, effectively deleting and substituting erythromycin PKS and other biosynthetic genes in Saccharopolyspora erythraea and Streptomyces spp. [106]. Xie et al. established a type I CRISPR/Cas methodology facilitating targeted deletions (8 bp–100 kb) with over 92% efficiency across phylogenetically distinct Streptomyces strains [107]. This technique also allows for the insertion of DNA cassettes to facilitate heterologous expression and activate dormant gene clusters, significantly enhancing Streptomyces research. Kim et al. altered Cas9-BD by including poly-aspartate tags, which diminished off-target binding and cytotoxicity [108]. This modified system has been utilized across many Streptomyces species, offering a versatile and high-efficiency editing tool for high-GC actinomycetes. The secondary metabolites of Streptomyces include the cytotoxic compound RT6, which is difficult to eliminate. In collaboration with Zhejiang Zhenyuan Pharmaceutical, Ai disrupted essential genes responsible for RT6 biosynthesis in the high-yield nystatin producer Streptomyces sp. ZY01, significantly enhancing nystatin purity [15] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Synthesis pathway and knockout of RT6 components. Streptomyces sp. ZY01 in vivo RT6 biosynthesis pathway (a); How the CRISPR/Cas9 system knockout plasmid PKCCas9dO works (b); Schematic diagram of knockout plasmid PKCCas9dC (c); and Schematic diagram of knockout plasmid PKCCas9dAD (d).

These examples demonstrate that CRISPR/Cas9 facilitates the convenient and efficient modification of antibiotic biosynthesis routes.

Researchers have noted that identical plasmids exhibit variable performance among Streptomyces species, presenting practical difficulties. Alternative Cas proteins have been assessed to overcome this constraint. Alongside the standard SpCas9, orthologues such as Sth1Cas9 from Streptococcus thermophilus, SaCas9 from Staphylococcus aureus, and FnCpf1 from Francisella tularensis have been evaluated and demonstrated to facilitate precise genome alteration with significant efficacy in streptomycetes. In 2024, Tan et al. revealed that Cas12j has superior transformation efficiency compared to SpCas9 and Cas12a, significantly enhancing editing efficacy for activating BGCs in Streptomyces sp. A34053, while SpCas9 and Cas12a face entry obstacles [109]. The findings suggest that Cas12j can mitigate the access constraints affecting SpCas9, thereby enhancing the applicability of CRISPR/Cas systems for genome editing in Streptomyces.

6. Prospective Directions

Invasive fungal diseases have emerged as a significant global public health concern owing to the rise of novel pathogens, heightened medication resistance, and an expanding immunocompromised demographic. Natural antifungal agents encompass polyenes, nucleosides, echinocandins, and others. Nystatin is restricted to second-line application because of its significant nephrotoxicity and narrow therapeutic index. Lipid-based formulations have been created to mitigate toxicity; nevertheless, their use is limited by elevated costs and residual toxicity [110,111]. Structural modifications have yielded analogues like BSG005 that preserve antifungal efficacy while mitigating nephrotoxicity [97], providing a more secure clinical alternative and enhancing the comprehension of the structure-activity connections of polyene antibiotics [112].

Simultaneously, advancements have been achieved in the studies into the mechanism of polyene pharmaceuticals. Historically, researchers believed that polyene pharmaceuticals eradicated fungi by creating ion channels. Recent research indicates that amphotericin B can remove ergosterol to create extramembranous sponge-like complexes, resulting in pore development and ion leakage, while also extracting and binding to cholesterol in human cell membranes, which leads to nephrotoxicity. This work offers guidance for the development of novel compounds that specifically bind to ergosterol while circumventing cholesterol binding [113,114,115]. A recent study has, for the first time, elucidated the full structure of the heptameric ion channel created by amphotericin B, providing a definitive structural template for the rational design of highly selective polyene medicines, including nystatin derivatives [116].

Advancements in gene editing and biosynthetic technologies have created novel prospects for the synthesis and enhancement of nystatin. Modern genetic engineering techniques primarily focus on inactivating the reductase domain of polyketide synthase (PKS) or modifying post-PKS genes. In the future, acquiring a profound understanding of the substrate selectivity of PKS domains may enable the modification of PKS to produce derivatives with innovative polyketide backbone architectures. Employing CRISPR/Cas9 for accurate genetic alterations of production strains—such as disrupting pathways for hazardous byproducts or augmenting precursor availability—offers potential for the high-yield, high-purity, and low-toxicity synthesis of nystatin and its derivatives. These developments will considerably augment the efficacy of this traditional medication in combating severe fungal infections.

7. Conclusions

Nystatin, a polyene macrolide antibiotic, displays its antifungal activity by binding to ergosterol in fungal cell membranes. It is extensively used for the treatment of localised fungal infections, including those in the mouth cavity, external ear canal, and vagina. Nonetheless, the hazardous contaminant (RT6) present in its multi-component mixture restricts its clinical safety. At present, high-performance liquid chromatography has emerged as a pivotal technique for quality control. Utilising combinatorial biosynthesis and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technologies, genes associated with toxic components can be eliminated to improve product purity, while alterations to polyketide synthase domains can produce derivatives that maintain antifungal efficacy with less toxicity. Subsequent research ought to persist in concentrating on the synthetic biological engineering of production strains, the creation of innovative low-toxicity derivatives, and the enhancement of distribution strategies, like liposomes and nanoparticles. This would enhance nystatin’s safety and efficacy, so it more effectively tackles the issues presented by invasive fungal infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.; Project administration, R.G.; Software, W.J.; Funding acquisition, X.L.; Visualization, X.L.; Methodology, X.L.; Data curation, X.L., J.Z. and Y.Z.; Investigation, W.J. and Z.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, X.L., J.Z., Z.C. and R.G.; Writing—review and editing, R.G., X.L., J.Z. and Y.Z.; Supervision, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32302042), Major Scientific and Technological Project of Zhejiang Province (2024C04029 and 2023C04027), and Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (LQ23C200012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of Analysis and Testing Center at Zhejiang University of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xiaofeng Liu and Wei Jiang were employed by the company Zhejiang Zhenyuan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry |

| FSD | Fourier self-deconvolution |

| VVC | Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| PKS | Polyketide synthase |

| KS | β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase |

| AT | Acyltransferase |

| ACP | Acyl carrier protein |

| TE | Thioesterase |

| ZFNs | Zinc-finger nucleases |

| TALENs | Transcription activator-like effector nucleases |

References

- Mireille, F.; Laurent, D. Microbial Secondary Metabolism and Biotechnology. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.S.; Campos, C.D.L.; Pereira Filho, J.L.; Monteiro, C.R.A.V.; Neto, V.M. Antimicrobial and Anti-Infective Activity of Natural Products: Unveiling Mechanisms, Synergies, and Translational Applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, L.D.; Sergio, S. Microbial drug discovery: 80 years of progress. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuan, S.L.; Bing, C.Y.; Han, D.S.; Jin, C.L.; Pema, T.P. Bridging chemical space and biological efficacy: Advances and challenges in applying generative models in structural modification of natural products. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2025, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, G.D. Opportunities for natural products in 21st century antibiotic discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, M.; Marco, P.; Tilmann, W.; Mark, B.; Peter, H.; Ludovic, H.; Rolf, M. Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotchev, S.B. Polyene macrolide antibiotics and their applications in human therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.S.; Li, Y.C.; Wen, Y.H.; Chen, T.; Liu, N.; Ling, M.M.; Qiu, Z.X.; Zhuo, S.; Wang, Z.Q. A polyene macrolide targeting phospholipids in the fungal cell membrane. Nature 2025, 640, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamill, R.J. Amphotericin B formulations: A comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs 2023, 73, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, T.; Svetlana, E.; Alexander, A.; Olga, O.; Eslam, G.; Elena, B.; Andrey, S. Semisynthetic Amides of Amphotericin B and Nystatin A1: A Comparative Study of In Vitro Activity/Toxicity Ratio in Relation to Selectivity to Ergosterol Membranes. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamberardino, C.D.; Schell, W.A.; Tenor, J.L.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Perfect, J.R. Efficacy of Liposomal Nystatin in a Rabbit Model of Cryptococcal Meningitis. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, L.; Duan, Y.W. Identification of tetramycin and tetraenomycin in Streptomyces CB02959 and optimization of culture medium. Microbiol. China 2021, 48, 2341–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.S.; Wu, S.Y.; Shen, L.J.; Liang, S.F. A study of nystatin A-94. Sci. Bull. 1959, 23, 795–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.M. Synthetic Biological Modification of Artemisinic Acid and Nystaticin Engineering Bacteria Based on CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing Technology. Master’s Thesis, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/CiBUaGVzaXNOZXdTMjAyNTA2MTMyMDI1MDYxMzE2MTkxNhIIWTM4MDMwMTQaCGRlcXZ4eGhr (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Zhou, G.Y.; Chen, P.; Tian, Z.H.; Liu, W.J.; Li, J. Nystatin tablets quality control study. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2012, 6, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Niu, X.; Li, G.L. Identification of components and potential toxicity prediction of nystatin and nystatin by HPLC-MS method. Drugs Clinic 2022, 37, 1234–1238. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7107731337&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Sun, S.N.; Len, X.Y.; Li, Y.R.; Sun, Z.H.; Li, X.Q.; Meng, X.Y.; Xie, Y.Y.; Shan, G.Z. Structural identification of unknown components in nystatin and determination of content by UHPLC method. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 41, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J.; Reddy, P. Digoxin Toxicity in Renal Failure: Resolution with Plasma Exchange After Fab Therapy Failure. Cureus 2025, 17, e96841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hack, J.B.; Wingate, S.; Zolty, R.; Rich, M.W.; Hauptman, P.J. Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Digoxin Toxicity. Am. J. Med. 2024, 138, 25–33.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, R.; Vagha, J.D.; Meshram, R.J.; Patel, A. A Comprehensive Review on Unveiling the Journey of Digoxin: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives. Cureus 2024, 16, e56755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.R.; Shu, M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Yang, W.J.; Lin, Z.H. 3D-QSAR study of 2,5-diketopiperazine microtubule inhibitors. Comput. Appl. Chem. 2014, 31, 86–90. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=48437142&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Liao, S.R.; Qin, X.C.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Li, J.S.; Liu, Y.H. Design, synthesis and cytotoxic activities of novel 2,5-diketopiperazine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvie, L.; Muriel, G.; Roger, G.; Luc, P.J. The albonoursin gene Cluster of S noursei biosynthesis of diketopiperazine metabolites independent of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, A.; Yan, Z.; Ahmed, F.; Tong, W.T.; Hans, M.; Jin, X. Effect of Nystatin on Candida albicans–Streptococcus mutans duo-species biofilms. Arch. Oral Biol. 2022, 145, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, M.P.; Blay, R.A.; Geyer, S.; Buck, S.M.; Pollock, L.; Mayner, R.E.; Epstein, J.S. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication in H9 cells by nystatin-A compared with other antiviral agents. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1993, 9, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virág, E.; Seffer, D.; Pénzes-Hűvös, Á.; Varajti, K.; Hegedűs, G.; Jankovics, I.; Pallos, J.P. Repurposed Nystatin to Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 and Mutants in the GI Tract. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2021, 40, 31854–31865. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.19.464931v1 (accessed on 15 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Omelchuk, O.; Tevyashova, A.; Efimova, S.; Grammatikova, N.; Bychkova, E.; Zatonsky, G.; Shchekotikhin, A. A Study on the Effect of Quaternization of Polyene Antibiotics’ Structures on Their Activity, Toxicity, and Impact on Membrane Models. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, E.; Weber, J.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Tammireddy, S.; Whitfield, P.D.; Brakhage, A.A.; Warris, A. Recreation of in-host acquired single nucleotide polymorphisms by CRISPR-Cas9 reveals an uncharacterised gene playing a role in Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance via a non-cyp51A mediated resistance mechanism. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 130, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanc, L.; Božič, B.; Jokhadar, Z.Š.; Dolenc, M.S.; Gomišček, G. The pore-forming action of polyenes: From model membranes to living organisms. BBA-Biomembranes 2018, 1861, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, V.; JeanMarc, L. Solution NMR structure of five representative glycosylated polyene macrolide antibiotics with a sterol-dependent antifungal activity. Eur. J. Biochem. FEBS 2002, 269, 4533–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A.G.; Marquês, J.T.; Carreira, A.C.; Castro, I.R.; Viana, A.S.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P.; Silva, L.C. The molecular mechanism of Nystatin action is dependent on the membrane biophysical properties and lipid composition. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2017, 19, 30078–30088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngece, K.; Ntondini, T.L.; Khwaza, V.; Paca, A.M.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Polyene-Based Derivatives with Antifungal Activities. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quindós, G.; Gil-Alonso, S.; Marcos-Arias, C.; Sevillano, E.; Mateo, E.; Jauregizar, N.; Eraso, E. Therapeutic tools for oral candidiasis: Current and new antifungal drugs. Med. Oral Patol. Oral y Cir. Buccal 2019, 24, e172–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, C.; Siebe, P.; Katrien, L.; Patrick, V.D. Amphotericin B and Other Polyenes-Discovery, Clinical Use, Mode of Action and Drug Resistance. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipa, S.; Cecília, N.; Domingos, F.; Salette, R.; Paulo, C. Reviving the interest in the versatile drug nystatin: A multitude of strategies to increase its potential as an effective and safe antifungal agent. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 199, 114969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.S.; Jesus, J.A.; Bezerra-Souza, A.; Laurenti, M.D.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Passero, L.F.D. Activity of Fenticonazole, Tioconazole and Nystatin on New World Leishmania Species. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anamika, R.; Ranjan, S.M.; Saurav, P.; Grzegorz, S.; Lora, M.; Rupsa, D.; Barbara, L. Nystatin Effectiveness in Oral Candidiasis Treatment: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Life 2022, 12, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddasani, S.; Rivin, G.; Fleischer, A.B. The Persistence of Nystatin Use for Dermatophyte Infections. Dermatol. Times 2023, 44, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarani, N.; Bharadava, K.; Kaushik, A.; Dave, A.; Gangawane, A.K.; Kaushal, R.S. Leishmaniasis: A multifaceted approach to diagnosis, maladies, drug repurposing and way forward. Microbe 2025, 6, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, S.; Peter, R.; Daniel, P.; Atenisa, C.; Jacob, K.; Daniel, W. Direct observation of nystatin binding to the plasma membrane of living cells. BBA-Biomembranes 2021, 1863, 183528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhou, M.J.; Piao, H.Y. Preparation and quality evaluation of nystatin suspension. Chin. J. Pharm. 2022, 20, 47–55+61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouSamra, M.M.; Basha, M.; Awad, G.E.A.; Mansy, S.S. A promising nystatin nanocapsular hydrogel as an antifungal polymeric carrier for the treatment of topical candidiasis. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun-Jin, K.; Sik, J.S.; Tae-Yub, K. Antifungal Effect of a Dental Tissue Conditioner Containing Nystatin-Loaded Alginate Microparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.L.; Xu, Z.N.; Liu, T.F.; Lin, J.P.; Cen, P.L. Effects of cultivation conditions on the production of natamycin with Streptomyces gilvosporeus LK-196. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2007, 42, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Lu, F.P.; Du, L.X. Natamycin production by Streptomyces gilvosporeus based on statistical optimization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5057–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Tao, Z.S.; Zheng, H.L.; Zhang, F.; Long, Q.S.; Deng, Z.X.; Tao, M.F. Iteratively improving natamycin production in Streptomyces gilvosporeus by a large operon-reporter based strategy. Metab. Eng. 2016, 38, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volokhan, O.; Sletta, H.; Sekurova, O.N.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Zotchev, S.B. An unexpected role for the putative 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase-encoding genenysF in the regulation of nystatin biosynthesis in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 249, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.H.; Liu, F.; Hou, Z.W.; Zong, G.L.; Zhu, X.Q.; Ling, P. Enhancement of natamycin production on Streptomyces gilvosporeus by chromosomal integration of the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin gene (vgb). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Cui, Y.Q.; Zhang, F.; Cui, H.; Ni, X.P.; Chen, F.; Xia, H.Z. Enhancement of nystatin production by redirecting precursor fluxes after disruption of the tetramycin gene from Streptomyces ahygroscopicus. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ni, X.P.; Shao, W.; Su, J.; Su, J.Q.; Ren, J.; Xia, H.Z. Functional manipulations of the tetramycin positive regulatory gene ttmRIV to enhance the production of tetramycin A and nystatin A1 in Streptomyces ahygroscopicus. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, D.B.G.A.; Pathirana, W.; Amara, P. Potency determination of antidandruff shampoos in nystatin international unit equivalents. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 70, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.J. Improvement of the method for the determination of nystatin and its tablet content. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 2013, 33, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Ma, B.F.; Zhang, P.P.; Yao, S.C.; Ning, B.M. Improvement of the titer determination method of tetraenyl antifungal antibiotics. Chin. J. Antibiot. 2023, 48, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, H.; Mohsen, N.; Ghodratollah, A.; Mehdi, A. Photodegradation study of nystatin by UV-Vis spectrophotometry and chemometrics modeling. J. AOAC Int. 2014, 97, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.P.; Zhang, D.J.; Cui, X.J. Application of ultraviolet spectrophotometry in the determination of nystatin content in nystatin oil. Shandong Med. J. 2012, 52, 48–50. Available online: https://lczl.med.wanfangdata.com.cn/Home/DocumentDetail?id=shandyy201244017 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Ibrahem, L.I.; Rashid, Q.N. Spectrophotometric determination of nystatin in its pharmaceutical preparations. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2450, 020034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.R.; Abolmagd, E.; Badrawy, M.; Nour, I.M. Innovative Earth-Friendly UV-Spectrophotometric Technique for In Vitro Dissolution Testing of Miconazole Nitrate and Nystatin in Their Vaginal Suppositories: Greenness Assessment. J. AOAC Int. 2022, 105, 1528–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.L.; He, R.; Zhang, F. Quality control and stability study of nystatin ointment. Strait Pharm. J. 2009, 21, 83–85. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=32775240&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Zeng, W.X.; Liu, L.B.; Tang, W.C.; Sun, L.L. Ultraviolet spectrophotometry was used to determine the nystatin content in vaginal tablets. J. China-Jpn. Friendsh. Hosp. 2012, 26, 118–119. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=41524106&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Lemus Gallego, J.M.; Pérez Arroyo, J. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrocortisone, nystatin and oxytetracycline in synthetic and pharmaceutical preparations based on various univariate and multivariate methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 460, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.; Stewart, A.; Flournoy, V.; Zito, S.W.; Vancura, A. Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Nystatin in Pharmaceutical Preparations. J. AOAC Int. 2001, 84, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F.G. Investigation of the stability of nystatin liniment prepared by different media and hospital dispensing management. Chin. J. Mod. Appl. Pharm. 2022, 39, 3123–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.M.; Naguib, I.A.; Zaazaa, H.E.; Nagieb, H.M. Ecofriendly single-step HPLC and TLC methods for concurrent analysis of ternary antifungal mixture in their pharmaceutical products. BMC Chem. 2023, 17, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsharkawy, L.; Hegazy, M.A.; Elgendy, A.E.; Ahmed, R.M. Experimental Design Approach for Development of HPLC Method for Simultaneous Analysis of Triamcinolone, Nystatin, and Gramicidin in Industrial Wastewater. Separations 2023, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Samantha, M.; Wu, T.T.; Zeng, Y.; Aaron, L.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J. Impact of Nystatin Oral Rinse on Salivary and Supragingival Microbial Community among Adults with Oral Candidiasis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Effect of nystatomin tablets combined with compound chlorhexidine gargle in the treatment of patients with oral candida infection after orthodontics. Med. J. Chin. People’s Health 2023, 35, 94–96. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7110015050&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Deng, K.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Gong, Y. Clinical application of nystaticin combined with honey in the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis after chemotherapy. Public Med. Forum Mag. 2022, 26, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Zhang, L.L.; Hu, Z.W.; Wang, P.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y. Clinical effect of nystaticin tablets combined with rehabilitation new solution for the prevention of oral infection after impacted wisdom tooth extraction and its effect on Th17/Treg cell immunity. Chin. J. Nosocomiology 2024, 34, 2022–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbul, M.S. Antifungal Activity of Salvia Jordanii Against the Oral Thrush Caused by the Cosmopolitan Yeast Candida Albicans Among Elderly Diabetic Type 2 Patients. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2020, 11, 20031493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J. Exploration of the effect of fluconazole combined with nystaticin in the treatment of thrush. Med. Diet Health 2020, 18, 118–119. Available online: https://cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-YXSL202004084.htm (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Paiva, L.F.D.; TeixeiraLoyola, A.B.A.; Schnaider, T.B.; Souza, A.C.D.; Lima, L.M.Z.; Dias, D.R. Association of the essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf with nystatin against oral cavity yeasts. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94, e20200681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazia, H.; Uzma, F.; Kumar, D.A.; Kalicharan, S.; Aamir, M.M.; Suhail, F.; Zeenat, I. In Silico Guided Nanoformulation Strategy for Circumvention of Candida albicans Biofilm for Effective Therapy of Candidal Vulvovaginitis. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 6918–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.Y.; Wang, W.; Su, Y.L.; Sun, W.; Ma, L.Y. Antibiotics therapy combined with probiotics administered intravaginally for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Med. 2023, 18, 20230644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.M. Clinical efficacy of fluconazole combined with nystatin vaginal suppositories in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Chin. J. Mod. Drug Appl. 2023, 17, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Zhou, L.; Wei, H.P. Efficacy of fluconazole, three-dimensional nystatin suppositories and lactobacillus vaginal capsules in the sequential treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Lab. Med. Clin. 2020, 17, 2723–2724. Available online: http://jyyxylc.com/jyyxylc/article/abstract/196640?st=search (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Wang, J. Comparison of the efficacy of nifurtail nystatin vaginal soft capsules with miconazole nitrate suppositories in the treatment of fungal vaginitis. Chin. J. Sch. Dr. 2020, 34, 944–945. Available online: https://www.zgxyzz.org.cn/CN/Y2020/V34/I12/944 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Xie, F.; Li, S. Clinical effect of nifurtel nystatin vaginal capsule combined with ornidazole suppositories in the treatment of patients with trichomoniasis vaginitis. Guizhou Med. J. 2024, 48, 1412–1414. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/Ch9QZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJTmV3UzIwMjQxMTA1MTcxMzA0EhJndWl6aG91eXkyMDI0MDkwMjMaCHZrN2V0dGVk (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Wang, W.L.; Wan, X.L.; Li, T.W. The effect of sequential medication in the treatment of fungal vaginitis and the effects of sequential medication on vaginal microecology, PCT and CRP levels of vaginal microecology. Clin. Res. Pract. 2024, 9, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Bai, G.P.; Jin, Y.G. Evaluation of the efficacy of combination therapy in the treatment of fungal otitis externa. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, W.W.; Wakely, P.E.; Kalmar, J.R.; Argyris, P.P. Fungal Otitis Externa (Otomycosis) Associated with Aspergillus Flavus: A Case Image. Head Neck Pathol. 2024, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, O.; Saliba, I. Effect of nystatin on Guinea Pigs’ inner ear. Neurotox Res. 2011, 20, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekard-Amenitsch, S.; Schriebl, A.; Posawetz, W.; Willinger, B.; Kölli, B.; Buzina, W. Isolation of Candida auris from Ear of Otherwise Healthy Patient, Austria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1596–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Effect of otoendoscopic clotrimazole ointment and nystatin powder in the treatment of fungal otitis externa. Harbin Med. J. 2023, 43, 88–90. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7111413421&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Wang, R.H.; Zeng, L.; Tang, X. Analysis of the efficacy of nystaticin cream combined with salicylic acid alcohol ear drops in the treatment of fungal otitis externa. Zhejiang Clin. Med. J. 2021, 23, 1298–1299. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/ChVQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJMjAyNTA2MjISD3pqbGN5eDIwMjEwOTAyNBoIczNlYms0Y2Q%3D (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Reeves, C.D.; Murl, S.; Ashley, G.M.; Piagentini, M.; Hutchinson, C.R.; McDaniel, R. Alteration of the substrate specificity of a modular polyketide synthase acyltransferase domain through site-specific mutations. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 15464–15470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003, 7, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brautaset, T.; Sekurova, O.N.; Sletta, H.; Ellingsen, T.E.; StrŁm, A.R.; Valla, S.; Zotchev, S.B. Biosynthesis of the polyene antifungal antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455: Analysis of the gene cluster and deduction of the biosynthetic pathway. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olga, V.; Håvard, S.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Zotchev, S.B. Characterization ofthe P450 monooxygenase NysL, responsible for C-10 hydroxylation durin biosynthesis of the polyene macrolide antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, N.; Håvard, S.; Brautaset, T.; Borgos, S.E.F.; Sekurova, O.N.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Zotchev, S.B. Analysis of the mycosamine biosynthesis and attachment genes in the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7400–7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, W.L. Polyene macrolide antibiotic biosynthesis and combination biosynthesis. Chin. J. Mar. Drugs 2013, 32, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautaset, T.; Per, B.; Håvard, S.; Lars, H.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Strøm, A.R.; Zotchev, S.B. Hexaene Derivatives of Nystatin Produced as a Result of an Induced Rearrangement within the nysC Polyketide Synthase Gene in S. noursei ATCC 11455. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Per, B.; Borgos, S.E.F.; Pascale, T.; Håvard, S.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Jean-Marc, L.; Zotchev, S.B. Chemical diversity of polyene macrolides produced by Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 and recombinant strain ERD44 with genetically altered polyketide synthase NysC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4120–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Han, Y.C.; Park, S.J.; Oh, S.H.; Kang, S.H.; Choi, S.S.; Kim, E.S. Nystatin-like Pseudonocardia polyene B1, a novel disaccharide-containing antifungal heptaene antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautaset, T.; Håvard, S.; Aina, N.; Borgos, S.E.F. Improved Antifungal Polyene Macrolides via Engineering of the Nystatin Biosynthetic Genes in Streptomyces noursei. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urnov, F.D.; Rebar, E.J.; Holmes, M.C.; Steve, Z.H.; Gregory, P.D. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas, C.; Doyle, E.L.; Michelle, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Clarice, S.; Voytas, D.F. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.L.; Larson, H.M.; Morsut, L.; Liu, Z.; Brar, G.A.; Sandra, E.T.; Lei, S.Q. CRISPR-Mediated Modular RNA-Guided Regulation of Transcription in Eukaryotes. Cell 2013, 154, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Lo, T.W.; Zeitler, B.; Pickle, C.S.; Ralston, E.J.; Lee, A.H.; Amora, R.; Miller, J.C.; Leung, E.; Meng, X.; et al. Targeted Genome Editing Across Species Using ZFNs and TALENs. Science 2011, 333, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jao, L.; Wente, R.S.; Chen, W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13904–13909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, K.C. CRISPR-Net: A Recurrent Convolutional Network Quantifies CRISPR Off-Target Activities with Mismatches and Indels. Biotech. Week 2020, 7, 1903562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chuai, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q. Toward a molecular mechanism-based prediction of CRISPR-Cas9 targeting effects. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, R.E.; Yajie, W.; Huimin, H. High-efficiency multiplex genome editing of Streptomyces species using an engineered CRISPR/Cas system. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015, 4, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zheng, G.; Jiang, W.; Hu, H.; Lu, Y. One-step high-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in Streptomyces. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qu, X. Efficient editing DNA regions with high sequence identity in actnomycetal genomes by a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2019, 4, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, T.; Luo, Y. Harnessing the Streptomyces-originating type I-E CRISPR/Cas system for efficient genome editing in Streptomyces. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.D.; Gu, B.; Cha, Y.; Ha, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, G.; Cho, B.K.; Oh, M.K. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 for Streptomyces sp. genome editing to improve specialized metabolite production. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.L.; Heng, E.; Leong, Y.C.; Ng, V.; Yang, L.K.; Seow, D.C.S.; Koduru, L.; Kanagasundaram, Y.; Ng, S.B.; Peh, G.; et al. Application of Cas12j for Streptomyces Editing. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulastri, E.; Rahma, M.N.; Herdiana, Y.; Elamin, K.M.; Mohammed, A.F.A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Wathoni, N. Enhancing Antifungal Efficacy and Stability of Nystatin Liposomes Through Chitosan and Alginate Layer-by-Layer Coating: In vitro Studies Against Candida albicans. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 10739–10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Milani, A.T.; Soufiani, K.B. Nystatin Encapsulated Nanoliposomes: Potential Anti-infective against Candida spp. Isolated from Candidiasis Patients. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2024, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preobrazhenskaya, M.N.; Olsufyeva, E.N.; Solovieva, S.E.; Tevyashova, A.N.; Reznikova, M.I.; Luzikov, Y.N.; Zotchev, S.B. Chemical modification and biological evaluation of new semisynthetic derivatives of 28, 29-Didehydronystatin A1 (S44HP), a genetically engineered antifungal polyene macrolide antibiotic. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.M.; Clay, M.C.; Cioffi, A.G.; Diaz, K.A.; Hisao, G.S.; Tuttle, M.D.; Nieuwkoop, A.J.; Comellas, G.; Maryum, N.; Wang, S.; et al. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufourc, E.J. Sterols and membrane dynamics. J. Chem. Biol. 2008, 1, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, D.; Andrew, N.; Valerie, L.; Michael, H.; Wolfgang, K.; Giovanna, F.; Wacklin Knecht, H.P. The Antifungal Mechanism of Amphotericin B Elucidated in Ergosterol and Cholesterol-Containing Membranes Using Neutron Reflectometry. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuichi, U.; Tomoya, Y.; Mayank, D.; Kosuke, F.; Sangjae, S.; Yasuo, N.; Michio, M. Amphotericin B assembles into seven-molecule ion channels: An NMR and molecular dynamics study. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.