Abstract

Hyperoside is an active ingredient in plants, such as Hypericum monogynum in Hypericaceae, Crataegus pinnatifida in Rosaceae and Polygonum aviculare in Polygonaceae. Its pharmacologic effects include preventing cancer and protecting the brain, neurons, heart, kidneys, lung, blood vessels, bones, joints and liver, among others. Pharmacokinetic analysis of hyperoside has revealed that it mainly accumulates in the kidney. However, long-term application of high-dose hyperoside should be avoided in clinical practice because of its renal toxicity. This review summarises the structure, synthesis, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of hyperoside.

1. Introduction

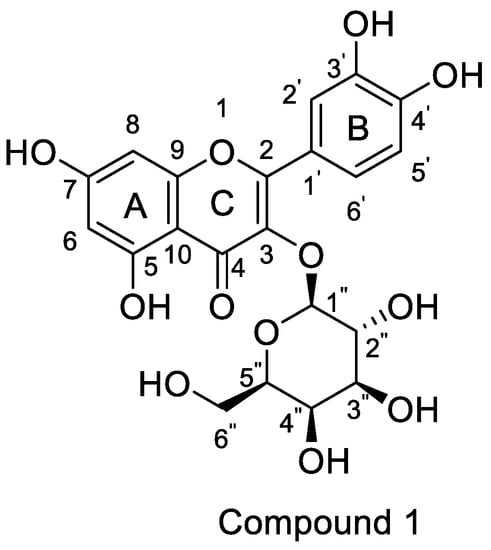

Hyperoside, which has the structure shown in Figure 1, is an active ingredient in plants such as Hypericum monogynum in Hypericaceae, Crataegus pinnatifida in Rosaceae and Polygonum aviculare in Polygonaceae [1,2,3]. These plants are widely distributed worldwide, especially in Southeast Asian countries, such as China, Japan and South Korea. They exhibit various pharmacological effects, such as protecting the blood vessels, regulating the digestive system and protecting against oxidation, aging and cancer [4,5,6].

Figure 1.

Structure of hyperoside.

Hyperoside was first extracted and isolated from Hypericum perforatum L. in 1937 [7]. Considering the low content and difficult extraction of this compound, scholars usually employ chemical and biosynthetic methods to obtain hyperoside. Guna et al. used resting cell fermentation and recycling to increase hyperoside production in 2020, and for the first time, obtained a maximum yield of 18,000 mg/L [8]. Hyperoside, also known as quercetin 3-O-beta-D-galactopyranoside, is a yellow solid, and its aglycon is quercetin [9,10]. Its antioxidant activity may be related to the hydroxyl groups on the A and B rings and the glycosides linked to the C ring [11], whereas its analgesic effect may be related to 3-galactopyranoside [12]. It also has a high affinity for soy protein [13]. Considering these properties, Wang et al. fabricated and characterised zein–tea polyphenol–pectin ternary complex nanoparticles and zein–pectin composite nanoparticles as effective delivery systems for hyperoside [14,15]. Such systems undoubtedly greatly improve the bioavailability of hyperoside. Hyperoside exerts its anti-cancer and brain-, nerve- and kidney-protective functions through the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) and nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/haem oxygenase-1 (HO-1) pathways. However, hyperoside easily accumulates in the kidney. Toxicity tests have shown that long-term use of hyperoside has nephrotoxic effects, but researchers have also found that this damage is reversible. So far, the toxic mechanism of hyperoside remains to be elucidated. This review summarises the structure, synthesis, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of hyperoside. This review may serve as a basis for developing hyperoside and expanding its application.

2. Structure and Synthesis

The aglycone of hyperoside is quercetin. Quercetin has many derivatives, such as quercetin-3′-O-acetic acid methyl ester, quercetin-3′-O-acetic acid, quercetin- 5-O-formate methyl ester and quercetin-5-O-formate [16]. Hyperoside (IUPAC name: 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-3-[(2S,3R,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxychromen-4-one) is a derivative of quercetin. Hyperoside also has derivatives, such as 2-(2,2-diphenyl-benzo [1,3] dioxincyclo-5-yl)-3-o-β-d-tetraacetyl pyrangalactose-5,7-dihydroxy-benzo pyran-4-one. Molecular docking of HCOV-229E showed that it has a good binding effect on the 3CL protease of HCOV-229E anti-prototype coronavirus [17].

2.1. Chemical Synthesis

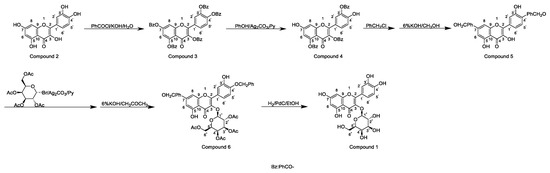

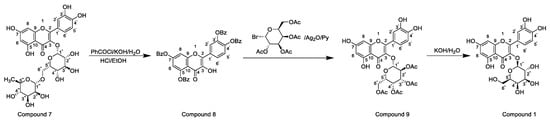

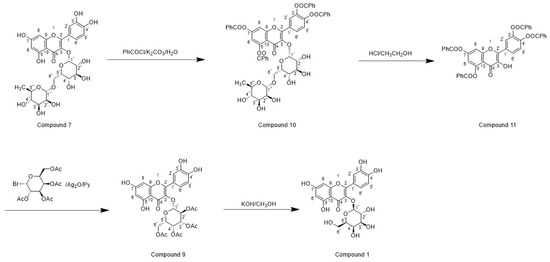

Horhammer et al. were the first to synthesise hyperoside. They used quercetin as a raw material for total synthesis and obtained a total yield of only 2.6%. The main synthetic challenge within the Horhammer synthesis of hyperoside was the selective glycosylation of the C3 hydroxyl group of quercetin. The series of highly controlled regioselective protection and deprotection operations resulted in the formation of compound 5. The Koening–Knorr reaction with this compound and acetylated bromoglucose proceeded regioselectivity at the hydroxyl in position C3. Further hydrogenolysis with hydrogen, using palladium on carbon as a catalyst, resulted in the formation of hyperoside [18]. This synthetic route is shown in Scheme 1. Following simple steps, Jiang et al. semi-synthesised hyperoside using rutin as the raw material under mild reaction conditions and obtained a total yield of 6.8% [19]. There are two things to note about this synthesis scheme. First, the team used compound 7 to react with benzoyl chloride and hydrolyse rutinose at the C3 position in the HCl/EtOH system to obtain compound 8. Second, the team also used the same reaction method as the previous team (the Koening–Knorr reaction) to select and further glycosylate the hydroxyl group at the C3, and the 5,7,3′ and 4′ substituents were converted to hydroxyl groups. Hyperoside was also obtained by hydrolysis of compound 9 [19] and the synthetic route is shown in Scheme 2. In 2002, Zhou integrated and improved the previous two schemes. Since the o-glycoside bond was usually a hemiacetal structure that can be easily hydrolysed, Zhou dissolved compound 10 in hot ethanol solution and hydrolysed it with strong HCl to obtain compound 11. He also used a Koening–Knorr reaction to remove the protective group in a KOH/anhydrous methanol system to obtain the target product. The hydrolysis conditions of benzoylated rutin were improved, and the yield of hyperoside was increased from 6.8% to 11% [12]. This synthetic route is shown in Scheme 3.

Scheme 1.

Hyperoside synthesis using a chemical method from the study by Horhammer et al. [18].

Scheme 2.

Hyperoside synthesis using a chemical method from the study by Jiang et al. [19].

Scheme 3.

Hyperoside synthesis using a chemical method from the study by Zhou [12].

2.2. Biosynthesis

Guna et al. constructed a uridine 5′-diphosphate-galactose synthesis pathway in 2020 and synthesised hyperoside by using quercetin as a raw material. In this method, quercetin is added to uractose diphosphate galactose and Escherichia coli containing the flavonol 3-O-galactosyltransferase gene to produce uractose diphosphate and hyperoside. The supply of uractose diphosphate galactose to the recombinant strain must be improved to increase hyperoside yield. The optimal conversion temperature is 30 °C, but this parameter is affected by oxygen content. Eight layers of gauze can be used to increase oxygen supply and facilitate its synthesis. Moreover, resting cell fermentation and recycling can increase the yield of hyperoside. The maximum yield of hyperoside can reach 18,000 mg/L, which is 393% of batch fermentation, achieving production at a scale of 10 g/L for the first time [8]. This method has high output, but its expansion to large-scale production faces certain difficulties because of the complicated procedures and expensive equipment.

3. Pharmacology

Hyperoside exerts a wide range of pharmacological effects (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11), such as preventing cancer and protecting the brain, neurons, heart and kidney, and by regulating various signalling pathways, metabolic processes, cytokines and kinases.

Table 1.

Anti-cancer Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 2.

Neuroprotective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 3.

Cardioprotective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 4.

Hepatoprotective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 5.

Brain-Protective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 6.

Renal-Protective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 7.

Lung-Protective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 8.

Vasoprotective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 9.

Bone-Protective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 10.

Joint-Protective Activity of Hyperoside.

Table 11.

Other Effects of Hyperoside.

3.1. Anti-Cancer Activity

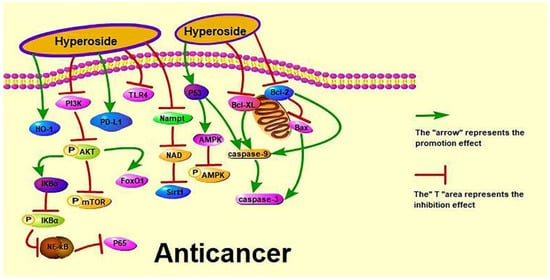

The incidence and mortality of cancer have increased with industrialisation [111]. Lung cancer has received increasing attention because of its high incidence rate. Previous studies reported that hyperoside has anti-lung cancer effects and its mechanism is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Anti-cancer effect of hyperoside.

3.2. Effect on Lung Cancer

According to the World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/cancer accessed on 10 January 2022), lung cancer deaths have risen significantly in upper-middle-income countries to more than twice that of the three other income groups combined. Clinically, chemotherapy can slightly prolong the survival of patients with advanced cancer but at the cost of significant adverse reactions [112]. Recent studies have shown that hyperoside can induce the apoptosis and G1/S phase arrest and inhibit the proliferation of A549 cells by down-regulating the expression of B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and B cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL) and up-regulating the expression of cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase 3 (caspase-3) [27]. Dong et al. discussed the anti-cancer effects of hyperoside on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from different aspects. Dong et al. showed that hyperoside inhibits the expression of PD-L1 in NSCLC cells and at the cell membrane surface at the transcriptional level by reducing the protein expression of transcription factor cellular-myelocytomatosis viral oncogene (c-Myc) [24]. Chen et al. investigated the effect of hyperoside on hypoxia-induced NSCLC A549 cells and found that hyperoside increases the phosphorylation and HO-1 expression of A549 AMPK [25]. Furthermore, hyperoside can inhibit the proliferation and induce the apoptosis of T790M-positive NSCLC cells by up-regulating forkhead box protein O1 by colon cancer associated transcript 1. It can also inhibit the proliferation and induce the apoptosis of H1975 cells in a dose-dependent manner [26]. However, the effect of hyperoside on NSCLC remains unclear to date, as is its effect on small cell lung cancer.

3.3. Effect on Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is the most common gynaecological cancer in Brazil, second only to breast cancer in women [113]. In Japan, two cases of lung cancer in children (23-month-old and 6-year-old boys) were found to be caused by the mother-to-child transmission of a cervical tumour [114]. Bian et al. and Wang et al. have performed anti-cervical cancer experiments on HeLa cells. Bian et al. explored the effects of hyperoside on nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)/silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1) expression during cell proliferation and migration and found that hyperoside treatment significantly decreased the mRNA expression levels for Nampt, NAD and Sirt1 [21]. Wang et al. studied the effects of hyperoside on the apoptosis and antioxidant capacity of HeLa cells by treating and culturing HeLa cells with hyperoside at 0, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μmol/L in vitro for 12, 24 and 48 h, and found that hyperoside decreased the cell survival rate in a dose- and time-dependent manner according to 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo(-z-yl)-3,5-di-phenytetrazoliumromide (MTT) assay, cell morphological observation, cell apoptosis detection and other methods. Their results also showed that hyperoside increases superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione (GSH) activities; significantly decreases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Bcl-2; and significantly increases the expression of malondialdehyde (MDA), Bax (Bcl2-associated X) and tumour suppressor gene p53 [20]. Guo et al. explained the effect of hyperoside on cervical cancer cells through a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, PPI module analysis, transcription factor (TF)-target network construction and survival analysis, RT-QPCR and Western blot to detect key genes. They found that hyperoside down-regulates c-Myc gene expression and inhibits HeLa and C-33A cell proliferation [22].

3.4. Effect on Liver Cancer

Liver cancer is a high-risk cancer with a high fatality rate. Patients often neglect treatment or misdiagnose this disease at the initial stage because its symptoms are similar to those of other liver diseases. Moreover, liver cancer has become a severe disease affecting the average life expectancy in China [115]. Jiang et al. and Wei et al. studied the protective effect of hyperoside on human liver cancer cells through different pathways. Jiang et al. studied the effects of hyperoside on the apoptosis of human hepatoma HepG2 cells via the P53/caspase pathway, and found that this compound significantly increases (p < 0.05) the expression levels of P53, caspase-9 and caspase-3 proteins in HepG2 cells [23]. Wei et al. studied the effect of hyperoside on the PI3K/AKT pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. They found that hyperoside down-regulates the expression of bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP-7), arrests the cell cycle growth of HepG2 cells in the G1 phase, inhibits the phosphorylation of AKT and significantly down-regulates the expression of PI3K [6]. In addition, Han Jingxia and Hu et al. performed protein–protein interaction experiments, such as fast protein liquid chromatography, co-immunoprecipitation and metabolomics, to illustrate the anti-liver cancer effect of hyperoside. Han Jingxia found that hyperoside inhibits the interaction between YY1 and P65 and P300, reduces the activity of quaking (QKI) promoter and down-regulates the expression of has_circ_0004631 [116]. Hu et al. found that hyperoside at 60 mg/kg can prevent liver damage caused by acetaminophen-induced oxidative stress and regulate glutathione-related metabolites and enzymes by inhibiting cytochrome P450 2E1 [117]. In conclusion, hyperoside exerts its anti-liver cancer effect by inhibiting the proliferation of liver cancer cells, arresting their cell cycle and effectively inhibiting the activity of the YY1 complex, the expression of QKI and the invasion and metastasis of liver cancer cells.

3.5. Effect on Breast Cancer

In recent years, the incidence of breast cancer in China has gradually increased, and breast cancer has become the most common malignant tumour in women [118]. Qiu et al. and Sun et al. studied the effect of hyperoside on breast cancer. Qiu et al. investigated the effect of hyperoside on the apoptosis of breast cancer cells via the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway and found that hyperoside inhibits the survival and migration and promotes the apoptosis of MCF-7 and 4T1 cells [28]. Sun et al. showed that hyperoside inhibits cell viability and increases apoptosis and caspase-3 activity in toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-positive breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, enhancing the sensitivity of such cells to paclitaxel [29].

3.6. Effect on Stomach Cancer

The incidence of gastric cancer is decreasing, but its morbidity and mortality remain high. Liu Haiwen and Wang et al. studied the effect of hyperoside on the proliferation and apoptosis of human gastric cancer MKN-45 cells. Liu Haiwen used hyperoside doses of 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL, and Wang et al. used hyperoside doses of 50, 75 and 100 μg/mL [30,31]. Both studies found that hyperoside increases the apoptosis rate and the G0/G1 phase ratio; up-regulates caspase-3, Bax, nuclear factor B inhibitor (IκBα) expression; decreases M/G2/M phase cell ratio; and down-regulates NF-κB P65 and Bcl-2 protein expression [30,31]. However, in terms of toxicity, a lower dose of hyperoside is safe since it reduces kidney accumulation in vivo. Therefore, given its effectiveness against gastric cancer cells, 25 μg/mL hyperoside should be given priority in the treatment of this disease.

3.7. Effect on Other Cancers

Ovarian cancer has a very high mortality rate among gynaecological cancers and is a major threat to women’s health. Xu et al. showed that hyperoside can up-regulate cleaved-caspase-3 and caspase-9, down-regulate Bcl-2, reduce the protein levels of p65 and p-IκB-α and suppress the migration and invasive abilities of SKOV3 cells. It can also inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway and resist ovarian cancer. Pancreatic cancer is a tumour of the digestive system [32]. Xue et al. found that hyperoside exerts a high killing activity on PANCI cells by inducing a high level of perforin in NK cells [33]. Skin cancer is primarily diagnosed visually, but dermatoscopic analysis, biopsy and histopathology are needed for confirmation [119]. Kong et al. studied the effect of hyperoside on skin tumours induced by 7, 12 dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA)/12-Otetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and found that hyperoside can reduce the phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and AMPK [34].

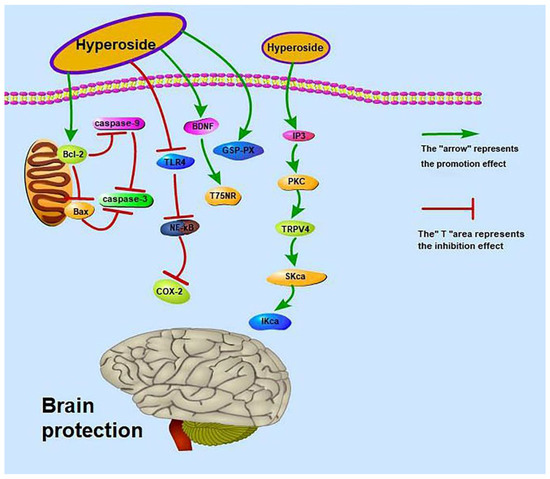

3.8. Brain Protection Activity

Brain-related diseases include cerebral ischaemia, stroke and so on. Hyperoside can regulate the expression of cerebral blood vessel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) by initiating the inositol trisphosphate (IP3)/protein kinase 1 (PKC) signalling pathway and activating intermediate conductance Kca (IKca) and small conductance (SKca) channels, thereby promoting Vascular endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization factor (EDHF) to generate vasodilation responses to improve ischaemic brain injury [70]. Hyperoside can also protect the brain and improve ischaemia–reperfusion. Ischemia–reperfusion is related to the TLR4/cyclooxygenase-2 signalling pathway and to brain-derived neuro-trophic factor (BDNF), p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NRT), Bcl-2 mRNA, p-PI3K, p-AKT, Bax and caspase-3 [69,71,72]. Moreover, hyperoside can improve nickel-induced brain injuries [73]. The mechanisms by which hyperoside exerts brain protection are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Brain-protective effect of hyperoside.

Some animal experimental data are also worthy of our attention. A previous study found that the intragastric administration of hyperoside at 50 mg/kg/day to Sprague–Dawley rats significantly decreases (p < 0.01) the cerebral infarct volume ratio; significantly increases the activities of total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) (p < 0.01), superoxide dismutase (SOD) (p < 0.01) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) (p < 0.05); and significantly decreases the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) (p < 0.01) [72]. Intragastric administration of hyperoside at 25 and 12.5 mg/kg to rats also increases cerebral blood flow in the cerebral cortex [120]. These results suggest that hyperoside exerts a protective effect on cerebral infarction in rats. Intraperitoneal injection of 50 and 100 mg/kg hyperoside increases the activity of lactate dehydrogenase in the brain tissues of mice to 147.7 ± 20.4 (p < 0.01) and 163.3 ± 34.2 (p < 0.01), respectively, and improves learning and memory disorders in the platform test [121]. However, the drug doses used in this study are too large and may affect the metabolism and kidney function of mice.

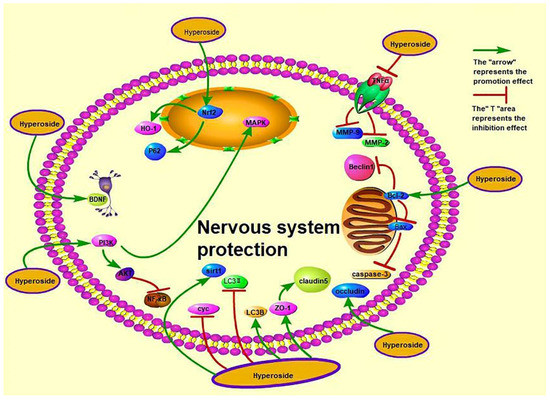

3.9. Neuroprotective Effect

Nervous system diseases occur in the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system and vegetative nervous system, with sensory, motor, consciousness and vegetative nervous system dysfunctions as the main manifestations of disease. Nervous system diseases include depression, epilepsy, Huntington’s disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and so on. Hyperoside exerts its anti-depressant effects possibly through the serotoninergic system, monoaminergic system and BDNF up-regulation [38,46]. In contrast, it exerts its anti-epileptic effect by increasing the antioxidant level and reducing the levels of autophagy-related proteins through the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways [39]. Systemic degenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (PD), are primary degenerative diseases of the central nervous system caused by the deposition of extracellular β-amyloid protein (amyloid-β, Aβ). Liu et al. showed that hyperoside dose-dependently up-regulates zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin and claudin-5 and down-regulates MMP (matrix metalloproteinase)-2 and MMP-9 to protect the damaged or weakened blood–brain barrier (BBB) [45]. However, the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease is diverse. Damaged or weakened BBB protection is only one mechanism in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, and the authors only studied the mechanism in vitro. Therefore, more research is required on the specific effects of hyperoside on Alzheimer’s disease in vivo and its other pathogenetic pathways to enrich this field. Previous studies found that hyperoside can reduce the expression of caspase3, Cyc and Bcl-2, induce HO-1 activation of Nrf2 and inhibit 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced oxidative stress to prevent and treat Parkinson’s disease [41,44]. Kwon et al. were the first to study the neuroprotective effect of hyperoside on 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity and its possible mechanism. This study promotes the application of hyperoside in the treatment of diseases related to Parkinson’s disease. Hyperoside can also reduce neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic rats through the tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)/NF-κB/caspase-3 signalling pathway, activate the SIRT1 gene and inhibit the nuclear factor-kappa-gene binding (NF-κB) gene to protect human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) from oxidative damage [37,40]. Furthermore, hyperoside can protect the nerves of mice from cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Intragastric administration of 50 mg/kg hyperoside increases the expression of ZO-1 and Claudin5 protein in mice [35]. In addition, intragastric administration of hyperoside to rats exerts significant anti-depressant-like effects (1.8 mg/kg/day p.o.) (p < 0.05) [122]. For example, intraperitoneal injection of hyperoside 1 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg shortened the immobile time of rats to 78.92 ± 3.32 and 69.33 ± 4.7 s (p < 0.05) and increased sucrose consumption by 103% ± 7.22% and 128% ± 11.1%, respectively (p < 0.01) [123]. Treatment with hyperoside (0.6 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks significantly reduces plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone levels by 40%–70% [124]. However, current research on hyperoside still faces several problems. For example, the research on the prevention and treatment of neurological diseases by using hyperoside is still in the experimental stage, and few clinical studies have been conducted. A consensus on a safe and effective dose of hyperoside for the human body has yet to be reached, and the clinical efficacy of the treatment is affected by many factors. Therefore, the clinical value and effective concentration of hyperoside needs to be explored and studied further. In addition, Huntington’s disease is a neurological disease, but scholars have yet to study whether hyperoside exerts a therapeutic effect on this disease. The mechanisms by which hyperoside exerts nerve protection are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Nerve-protective effect of hyperoside.

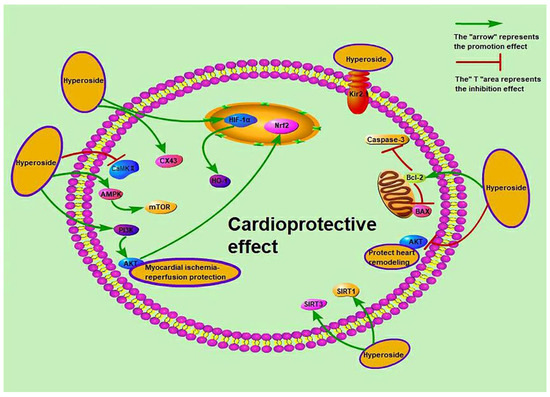

3.10. Cardioprotective Activity

Cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, heart failure and myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion, are commonly caused by abnormal heart function or structural defects. Hyperoside blocks the AKT pathway, which reduces the protein expression of B-type natriuretic peptide and β-myosin heavy chain by angiotensin II (Ang II) or enhances SIRT3 signal expression to improve cardiac hypertrophy [55,59]. Hyperoside also protects against myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion. The activated related pathways are protein kinase 1 (PKC)/mitochondrial ATP channel (mitoKATP) and AMPK/mTOR, and the affected proteins are gap junction protein 43 (Cx43), inwardly-rectifying potassium channel 2.1 (Kir2.1) and calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII), which also affects the activity of myocardial ATPase [47,50,54,56]. In addition, myocardial infarction in mice and heart failure in rats are related to the regulation of autophagy [53,57,60], and myocardial infarction is also related to the nucleotide binding oligomerization domain like receptor 1 (NLRP1) inflammatory pathway [60]. Hyperoside protects the myocardium of severely burned rats by regulating inflammation and oxidative stress and activating the SIRT1 signalling pathway [51]. At the same time, hyperoside can treat sepsis-related cardiac dysfunction by inducing the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)/HO-1 signalling pathway or inhibiting microRNA-21 (miR-21) [52,61]. Up-regulation of microRNA-138 (miR-138) can protect cardiomyocytes induced by hypoxia [58]. Hyperoside also protects the myocardial damage caused by diabetes and high glucose [48,49]. The mechanisms of cardioprotective activity are presented in Figure 5. Other research has shown that gavage of hyperoside (20 mg/kg/day) increases the left ventricular ejection fraction to 40.8% ± 5.1%, increases dp/dt max to 8735.4 ± 478.4 mmHg/s and decreases dp/dt min to −7902.3 ± 369.3 mmHg/s. It also decreases heart size and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area [59]. Intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg hyperoside decreases the infarct size in rats from 48.35 ± 6.74 to 23.61 ± 4.29 (p < 0.01) [125]. Hyperoside can ameliorate heart failure induced by thoracic aortic coarctation in rats and reduce myocardial cell cross-sectional area and heart weight/body weight ratio [57]. These studies suggest that hyperoside prevents stress overload-induced cardiac remodelling, alleviates myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury and prevents heart failure, among others. However, whether hyperoside affects atrial fibrillation has not been studied.

Figure 5.

Cardioprotective activity of hyperoside.

3.11. Hepatoprotective Activity

Liver-related diseases include fibrosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and so on. Hyperoside can activate the Nrf2 gene to protect the acute liver injury induced by N-acetyl-para-amino-phenol [64]. Hyperoside also exerts a protective effect on acute liver injury induced by CCl4 via two mechanisms. One is to increase the Nrf2 level by increasing extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)-chromosomal region maintenance 1 (Crm1), thereby protecting the liver from injury induced by CCl4 [62]. The other is to regulate the pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 2 (PHLPP2)-AKT-GSK-3β signalling pathway and reverse the decrease in SOD activity in the body [67]. At the same time, the factor member 1 of nuclear receptor subfamily group 4A (Nr4A1) related to Nrf2 is linked to the prevention of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by hyperoside [66]. Hyperoside exerts a hepatoprotective effect on diabetic mice, rats with liver fibrosis caused by heart failure and rats with hepatic ischaemia–reperfusion injury [63,65,68]. In rats, hyperoside (15 and 60 mg/kg) induces the reversal of serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase levels and protects liver tissue from CCl4-induced injury [126]. Intraperitoneal injection of hyperoside (50 mg/kg/day) decreases the Suzuki score of the liver from 6.0 ± 0.9 to 5.0 ± 0.5 (p < 0.05) and histological damage [65]. In addition, gavage of 100 and 200 mg/kg hyperoside improves vacuolar oedema and degeneration of liver cells and inhibits alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels in rats [63]. These results reflect the protective effect of hyperoside on the liver, though there is a need for researchers to study the effect of hyperoside on alcoholic fatty liver disease.

3.12. Renal Protective Activity

Kidney disease has risen from the 13th to the 10th leading cause of death worldwide. The death rate increased from 813,000 in 2000 to 1.3 million in 2019 (https://www.who.int/cancer) (accessed on 10 January 2022). Hyperoside can improve diabetic nephropathy by targeting the miR-499-5p/APC axis and inhibiting the extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)/cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)/miRNA-34a signalling pathway [79,80]. It can also treat acute kidney injury by regulating mitochondrial fission mediated by metalloproteinase-associated protein 1 (OMA1)-optic atrophy 1 and inhibiting TLR4 and nucleotide binding oligomerisation domain-like receptorprotein3 (NLRP3) pathways [74,78]. Liu et al. reported that hyperoside can inhibit autophagy through the AMPK-unc-51 like autophagy activated kinase 1 (ULK1) signalling pathway to prevent age-related renal injury, and provided the first opportunity for hyperoside to treat D-galactose-induced renal aging and damage [77]. In addition to the above three aspects, hyperoside can also improve the endogenous antioxidant and detoxification functions of kidney cells through the Nrf2/HO-1/quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) pathway [76]. Intragastric administration of hyperoside and quercetin (20 mg/kg/day) at a ratio of 1:1 can reduce the severity of renal crystal deposition (p < 0.05) [127] and reduce urinary citrate excretion to 48.38 ± 22.82 mg/24 h [127]. This finding suggests that hyperoside prevents calculi in rats. A mixture of quercetin and hyperoside (0.1 mg/kg/day) (1:1) was administered intragastrically to rats to reduce the expression of fibrosis-related proteins in obstructed kidneys [128], thereby protecting the kidney. Interestingly, although both experiments proved that hyperoside and quercetin (1:1) exert a protective effect on kidney diseases, the difference in dose gap is very large; thus, the accurate dosage could be explored in the future to provide a preliminary basis for clinical trials.

3.13. Protective Activity of Bone and Joint Diseases

Hyperoside has a protective effect on interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-induced osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. The pathways related to its protective mechanism include the NF-κB signalling pathway, p38 protein kinase pathway, PI3K/AKT/NF-κB and MAPK signalling pathway [88,92,95]. The nuclear factor receptor activator κB ligand (RANKL)/RANK/NF-κB signalling pathway is also related to the NF-κB signalling pathway. Experiments have verified that inhibiting the RANKL/nuclear factor kappa B receptor activator (RANK)/NF-κB signalling pathway can improve osteoporosis in ovariectomised (OVX) mice [89]. In addition, the factors used to treat osteoarthritis include TNF-α, IL-6, MMP3 and MMP13 [93,94]. Inhibiting the MAPK signalling pathway and regulating the TWEEP-p38 pathway also contribute to the protective effect of hyperoside on osteoblasts [90,91].

3.14. Others

Firstly, hyperoside can protect blood vessels. Hyperoside can reduce the production rate of ArgII by competing for active sites, changing the surface hydrophobicity of the enzyme, decreasing the vascular tone and inhibiting vascular remodelling, thereby lowering blood pressure [86]. Liu et al. used network pharmacology to elucidate the mechanism of anti-atherosclerosis treatment, which may be mainly related to the PI3K/AKT and MAPK signalling pathways [129]. Other researchers have demonstrated that hyperoside can regulate vascular endothelial cells by reducing low-density lipoprotein-C level, affecting nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity, regulating NO synthesis, improving vascular endothelial function and reducing p38 MAPK, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), ERK, NF-κB and TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) levels to inhibit vascular inflammation and affect atherosclerosis [85,87]. By contrast, Wang et al. found that hyperoside cannot reduce blood lipids in mice and cannot inhibit the formation of aortic atherosclerotic plaques [130]. Secondly, hyperoside also exhibits lung-protective functions. Hyperoside protects bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis through the AKT/GSK3β pathway and inhibits collagen secretion [81,83]. It also inhibits AMPK/mTOR signalling to reduce particulate-induced lung injury [82], and can be used to treat Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia (MPP) via the interaction of chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5)-CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) [84]. Thirdly, hyperoside has a function in ovarian protection. The protection of hyperoside in ovarian-related diseases is related to SHH signalling pathway, the PI3K/AKT anti-apoptotic pathway and Nrf-2/HO-1 anti-oxidative stress [97,98]. Fourth, hyperoside has an anti-inflammatory effect [96,102]. This anti-inflammatory effect is related to the miR-499a-5p/nuclear receptor interaction protein 1 (NRIP1) axis, regulation of the p38MAPK/Sirt6/NF-κB signalling pathway and inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway [99,103,104]. Hyperoside (100 mg/kg, i.p. (p < 0.05) and 200, 500 mg/kg, p.o. (p < 0.01)) significantly inhibits acetic acid-induced vascular permeability in mice [131]. In addition, 100 mg/kg hyperoside significantly decreases serum prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), TNF-α, IL-1β, c-reactive protein (CRP), myeloperoxidase (MPO) and MDA levels (p < 0.01) and significantly increases SOD activity in mice (p < 0.01) [132]. Haematoxylin and eosin results proved the effect of hyperoside on ulcerative colitis, suggesting that hyperoside demonstrates good anti-inflammatory activity. Intragastric administration of 100 mg/kg hyperoside in rats significantly reverses the up-regulation of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor containing n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor 2B (NR2B) in the midbrain periaqueductal grey and shows analgesic activity against continuous inflammatory stimulation in mice [133]. Hyperoside can also prevent age-related macular degeneration and protect against diabetic retinopathy [100,101]. It also has antioxidant activity [134,135,136,137]. Wang Mengyu reported that the antioxidant activity of hyperoside is related to the 3-position hydroxyl group of hyperoside [138]. Hyperoside can also protect the pancreas, fight fatigue and enhance NK cell proliferation [105,107,108]. In addition, hyperoside regulates the mTOR/S6K and TLR4/myeloid differentiation factor 88/NF-κB signalling pathways to reduce recurrent pregnancy loss and anterior cruciate ligament injury [109,110]. Pan Shanshan used a multi-omics strategy to demonstrate that hyperoside can regulate the metabolism of high-fat mice by changing the abundance of intestinal flora and down-regulating the expression of Cypla2 and Ugtla6b [137].

4. Pharmacokinetics

Hyperoside has a wide range of pharmacological effects and pharmacokinetic characteristics, such as easy accumulation in the viscera and kidneys, low oral bioavailability and compatibility with different drugs that prolong its elimination time in the body. The pharmacokinetics of hyperoside will be discussed in detail below. Ni et al. found that the extraction of hyperoside impurities from dodder seed by using ethyl acetate has minimal interference, high recovery and stability, and that using icariin as an internal standard could reduce errors in sample handling and injection; in addition, the hyperoside curve shows the main and secondary peaks [139]. Another scholar reported that the Cmax in rats intragastrically administered with Qianbai rhinitis capsules was 1.25 times that of rats treated with Senecio extract [140]. This result shows that hyperoside is compatible with other traditional Chinese medicines and they can improve its bioavailability and oral absorption. Chen et al. also found that t1/2, Tmax and AUC0-∞ are significantly prolonged after hyperoside is combined with other Chinese medicines, indicating that they can slow down the elimination of hyperoside in vivo, prolong the action time, promote its absorption and significantly improve bioavailability. They also found the highest accumulation of hyperoside occurred in the kidney, followed by the liver and lastly in the testes [141]. Chen Shanshan also studied the pharmacokinetics of hyperoside when administered multiple times and showed that this treatment improves Cmax, Tmax, AUC(0-T), AUC(0-ꝏ) and MRT [142]. Yuan et al. studied the effects of different administration methods in rats and found that the plasma levels from intraperitoneally administered hyperoside are closer to those of intravenously administered hyperoside than to those of intragastrically administered hyperoside; in addition, the bioavailability of hyperoside in rats is particularly low after intragastric administration [143]. These results indicate that intraperitoneal and intravenous injections are effective ways of administration. The pharmacokinetic profile of hyperoside is presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Hyperoside and Traditional Chinese Medicine Containing Hyperoside.

5. Toxicity

Hyperoside has many pharmacological effects, including significant renal protection. Previous pharmacokinetic studies indicated that hyperoside accumulates in the kidney. However, studies on the toxicity of hyperoside are very few. So far, only one team has studied the toxicity of hyperoside, and only animals were used in their studies. Firstly, an acute toxicity test of hyperoside showed that its LD50 > 5000 mg/kg [145]. Secondly, a bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test) indicated that hyperoside has no genetic toxicity [145]. An experiment on rat embryo and foetal developmental showed that this compound exerts negligible effects on pregnant rats but slows down the growth of foetal rats [146]. Thirdly, long-term use of hyperoside is toxic to the kidneys, but the damage is reversible [147]. However, research on the toxicity of hyperoside is not comprehensive, and a cellular experiments that verify whether or not hyperoside is cytotoxic remain to be conducted. Therefore, experiments must be conducted in the future to evaluate the biological safety of hyperoside and provide a basis for its future clinical applications.

6. Conclusions and Perspective

At present, many studies have shown that hyperoside can be found in Hypericaceae, Rosaceae and Polygonaceae plants. However, the plant family with the highest abundance of hyperoside cannot be determined because of the different measurement conditions used. Hyperoside has anti-cancer, brain-protective, neuroprotective, cardioprotective and renal-protective activities, among others. However, most scholars have only studied classic signalling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and NF-κB, and few scholars have studied other pathways. In the future, scholars could concentrate on different pathways to study the effects of hyperoside on target diseases to promote the advancement of medicine worldwide. At present, few studies have explored the pharmacokinetics, especially the excretion, of hyperoside. However, by consulting the existing literature on the pharmacokinetics of hyperoside, we can conclude that the drug-time curve after oral administration of hyperoside in rats shows bimodal absorption. This phenomenon may be related to hepato-enteric circulation or absorption by dual parts of the intestine, though these conjectures have not been confirmed by researchers. Studies have also shown that the bioavailability of orally administered hyperoside is lower than that of intraperitoneally injected hyperoside, which may be related to the first-pass metabolism of hyperoside and the physical properties of flavonoids (hydrophobicity). In response, researchers have developed hyperoside–zein/pectin composite nanoparticles and hyperoside-loaded zein–tea polyphenols–pectin ternary complex nanoparticles to slow the release of hyperoside [14,15]. This system improves the bioavailability of hyperoside. In addition, other scholars have found that combining hyperoside with other drugs can slow down its elimination in the body and prolong its action time, thereby increasing its bioavailability. Hyperoside is also used to treat chronic diseases, such as atherosclerosis, but its safety remains to be verified. As a result, the clinical application of hyperoside is limited. In short, the research on the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of hyperoside is insufficient, which directly restricts further therapeutic development of hyperoside. This review has summarised the pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of hyperoside and raised some issues worthy of future discussion to promote the application and development of hyperoside in the future.

Author Contributions

H.S. and X.F. reviewed and revised the manuscripts. W.X. participated in the revision of the manuscript. S.X. and S.C. collected the documents and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81860708 and No.82160747) and Ningxia Key Laboratory of Ethnic Minority Medicine Modernization (XZ2020005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors on request (X.F.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and publication.

References

- Wang, J.; Peng, S.L.; Wang, M.K.; Chen, N.Y.; Ding, L.S. Chemical constituents of Hyperricum monogynum. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2002, 27, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Simultaneous determination of isoquercetin and hyperoside in Hawthorn by HPLC. Jilin J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2019, 39, 949–952. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.Y.; Zheng, Y.M.; Fu, S.Q.; Wang, A.L. Quantitative determination of hyperoside and quercitrin and luteolin in Polygonum aviculare by HPLC. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2006, 4, 563–564. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.Y.; Zhu, X.Y.; Zhang, M.M. Research progress on pharmacological function of Hawthorn in the past five years. Chin. J. Basic Med. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2019, 25, 715–718. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.L.; Huang, L.D.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Wu, J. Research advances of Polygonum aviculare L. Anhui Med. Pharm. J. 2016, 20, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.F.; Hu, W.D.; Bao, W.X.; Mao, L.; Chen, J.X.; Li, H.J.; Wen, Y.K.; et al. Hyperoside suppresses BMP-7-dependent PI3K/AKT pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerzmanowska, Z. Hyperin, a glucoside of Hypericum perforatum L. Chem. Abstr. 1937, 64, 527. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, N.; Qiu, C.; Zhao, L.G.; Zhang, L.H.; Pei, J.J. Efficient production hyperoside from quercetin in escherichia coli through increasing UDP-galactose supply and recycling of resting cell. Catal. Lett. 2021, 151, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.Y.; Zhou, P.H.; Pei, G. Studies on chemical constituents of Hypericum sampsonii. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2002, 5, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T. Crataegus pinnatia Bge Chemical Composition and Quality Specification Research. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, Shenyang, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.W.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Hang, K.; Yang, X.N. Relationship between structure and activity of eight natural flavonoids against oxidation. J. East China Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2002, 01, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. Synthesis of New Type Analgesic Drug-Hyperin and Its Derivatives. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Tang, L.; Duan, R.; Hu, X.; Geng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.X.; Li, H. Interaction mechanisms and structure-affinity relationships between hyperoside and soybean beta-conglycinin and glycinin. Food Chem. 2021, 347, 129052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Li, M.; Liu, F.G.; Peng, F.; Li, F.; Lou, X.M.; Jin, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.D. Fabrication and characterization of zein-tea polyphenols-pectin ternary complex nanoparticles as an effective hyperoside delivery system: Formation mechanism, physicochemical stability, and in vitro release property. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Peng, F.; Liu, F.G.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Li, F.; Lei, H.J.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Xu, H.D. Zein-pectin composite nanoparticles as an efficient hyperoside delivery system: Fabrication, characterization, and in vitro release property. Lwt 2020, 133, 109869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhai, G. Progress in research on biological activity of quercetin derivatives. Chin. Pharm. J. 2021, 56, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Tan, H.; Zhu, W. Synthesis and SAR studies on hyperin and its analogues as 3CL protease inhibitors of human coronavirus 229E. Chin. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 17, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Hrhammer, L.; Wagner, H.; Arndt, H.G.; Dirscherl, R.; Farkas, L. Ber die synthese von quercetin-3-glykosiden; I. synthese und strukturbeweis von isoquercitrin, hyperosid und quercitrin. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1968, 101, 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.L.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, W.S. Study on synthesis of hyperoside. Acta Pharm. Sin. 1994, 29, 874–876. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.L.; Tang, W.Z.; Lin, F.R. Effects of hyperoside on apoptosis and antioxidative capacity of cervical cancer Hela cells. Chin. J. Coal Ind. Med. 2019, 22, 402–407. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, B.F.; Zhang, L.J.; Chen, S.H.; Wang, L.H.; Yang, L. Effect of hyperoside on the proliferation and migration of Hela cells via Nampt/NAD/Sirt1 pathway. Chin Pharm. 2021, 24, 624–629. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.K.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.W.; Liu, Y.D.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.Y. Effect of hyperoside on cervical cancer cells and transcriptome analysis of differentially expressed genes. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, S.; Xiong, H.S.; Wu, H.K.; Wen, J.; Liang, L. Regulatory effect of hyperoside on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic carcinoma cell HepG2 via mitochondrial P53/Caspase signaling pathway. Chin. J. Immunol. 2018, 34, 1832–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.W.; Kuang, Z.A.; Yin, M.X.; Liu, X.J.; Liu, Y.; Deng, H.B. Hyperoside exerts its anti-tumor activity by reducing the PD-L1 level in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2021, 56, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Wu, Y.X.; Qiu, Y.B.; Wan, B.B.; Liu, G.; Chen, J.L.; Lu, M.D.; Pang, Q.F. Hyperoside suppresses hypoxia-induced A549 survival and proliferation through ferrous accumulation via AMPK/HO-1 axis. Phytomedicine 2020, 67, 153138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Zhao, P.J.; Xu, H.F. Hyperoside exhibits anticancer activity in non-small cell lung cancer cells with T790M mutations by upregulating FoxO1 via CCAT1. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 43, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.P.; Liao, X.H.; Xiang, Y.; Yao, A.; Song, R.H.; Zhang, Z.J.; Huang, F.; Dai, Z.T.; Zhang, T.C. Hyperoside and let-7a-5p synergistically inhibits lung cancer cell proliferation via inducing G1/S. phase arrest. Gene 2018, 679, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.X.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, X.Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhou, N.; Ju, B.X.; Zhou, T.H.; Deng, G.Z.; Qiu, C.W. Hyperoside induces breast cancer cells apoptosis via ROS-mediated NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, T.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, M.D.; Yu, H.H.; Piao, H.Z. Administration with hyperoside sensitizes breast cancer cells to paclitaxel by blocking the TLR4 signaling. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 53, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W. Hyperoside Induces Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cell Line MKN-45 and Its Mechanism. Master’s Thesis, Jinzhou Medical University, Jinzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.M.; Qu, X.J.; Wang, Z.D.; Yang, T. Effect of hyperoside on the proliferation and apoptosis of human gastric cancer cells by inhibiting the nf-kb pathway. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2020, 36, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.W. Effects of hypericin on proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2018, 40, 702–706. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.J.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, T.; Lu, X.T.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, Z.H. Enhancement effects of hyperoside on killing activity of human NK cells against pancreatic cancer PANC1 cells. Chin. J. Pancreatol. 2018, 18, 324–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.H.; Sun, W.G.; Wu, P.F. Hyperoside exerts potent anticancer activity in skin cancer. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2020, 25, 463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Zhang, D.X.; Cao, J.W.; Yan, B.C. Neuroprotective effect and mechanism of hyperoside pretreatment on mice with cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shandong Med. J. 2021, 61, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Cai, J. Hypericin alleviates early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage through regulating Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway in rats. Zhejiang Med. J. 2020, 42, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Song, X.F.; Du, X.N.; Liu, Z.M. Protective effects of Chinese hawthorn leaf hyperoside against high glucose-induced injury in SH-SY5Y cells. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2019, 31, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.Z.; Fan, Y.J.; Pan, Y.; Shi, D.F.; Liu, C.M. Studies on the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside on the possible mechanism of 5-HT system. J. Changchun Norm. Uni. 2018, 37, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.W.; Tang, C.; Gao, M.M.; Rui, Y.G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yan, B.C. Hyperoside alleviates epilepsy-induced neuronal damage by enhancing antioxidant levels and reducing autophagy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 257, 112884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Famurewa, A.C.; Tang, J.; Olatunde, O.O.; Olatunji, O.J. Hyperoside attenuates neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment and oxidative stress via suppressing TNF-alpha/NF-kappa B/caspase-3 signaling in type 2 diabetes rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.J.; Li, Y.R.; Sun, M.Y.; Xiao, W.S.; Song, L.J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yu, J.Z.; Jin, X.M.; Ma, C.G.; et al. Hyperoside reduces rotenone-induced neuronal injury by suppressing autophagy. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 3149–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, D.X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.F.; Yang, S.L.; Feng, Y.L.; Luo, T.; Li, Y. Protective effects and mechanism of hyperoside in PC12 cells against oxidative stress injury induced by hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.L.; Chen, T.B.; Lei, B.; Zheng, N.D.; Wan, X.Q.; Xu, J.G.; Wang, T.H. Hyperoside attenuate inflammation in HT22 cells via upregulating SIRT1 to activities Wnt/beta-catenin and sonic hedgehog pathways. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 8706400. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.H.; Lee, S.R.; Park, Y.J.; Ra, M.; Lee, Y.; Pang, C.; Kim, K.H. Suppression of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress by hyperoside via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in dopaminergic neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.Y.; Bai, K.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, L.M.; Yu, G.R. Hyperoside protects the blood-brain barrier from neurotoxicity of amyloid beta 1–42. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orzelska-Gorka, J.; Szewczyk, K.; Gawronska-Grzywacz, M.; Kedzierska, E.; Glowacka, E.; Herbet, M.; Dudka, J.; Biala, G. Monoaminergic system is implicated in the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside and protocatechuic acid isolated from impatiens glandulifera royle in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 128, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.D.; Xue, T.; Huang, X.F. Cardioprotective effects of hyperoside on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Chin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 3721–3724. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, W.T.; Hu, L.P. Study on the protective effect of hypericin on diabetic myocardial injury. Asia-Pac. Tradit. Med. 2020, 16, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, M.L.; Hou, Y.L.; Guo, C.L. The effect and mechanism of hyperoside on high glucose-induced Oxidative Stress Injury of Myocardial Cells. J. Sichuan Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2018, 49, 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.F. The Effect and Mechanism of Hyperoside Onattenuating Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injuryvia Activating PKC/mitoKATP Signaling Pathway Inrats. Master’s Thesis, WanNan Medical College, Wuhu, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Li, J. Protective effects of hyperoside against myocardial injury in severely burned rats and its underlying mechanism. J. Shanxi Med. Univ. 2019, 50, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Yao, X.L.; Liu, T.; Liu, B.Y.; Fang, Z.C. Mechanism of hyperoside improving myocardial injury in model rats with sepsis. China Pharm. 2021, 30, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Rao, T.; Zhang, J. Hyperoside ameliorates the injury of heart and thoracic aorta in mice with myocardial infarction by regulating autophagy pathway. Chin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Yang, Q. Effects of hyperoside on the myocardical activities of ATPases and expressions of Cx43 and Kir2.1 in arrhythmia rats induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2018, 40, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.J.; Wang, F.F.; Bai, B.B.; Liu, P.Y.; Ji, Z.L. The protective effects of hyperoside on cardiac hypertrophy induced by transverse aortic constriction. Prog. Mod. Biomed. 2021, 21, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.S.; Guo, W.G.; Shang, F.J.; Teng, J.W.; Ma, C. Effect of hyperin on ischemia reperfusion injury in H9C2 cells. Chin. J. Geriatr. Heart Brain Vessel Dis. 2019, 21, 294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.T.; Lu, C.H.; Qu, F.X.; Jiang, X.Y. Protective effect of hyperoside on heart failure rats via attenuating myocardial apoptosis and inducing autophagy. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.Y.; Yin, X.Q.; Wu, F.; Zeng, S.J.; Gao, F.; Xin, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.B. Hyperoside protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia-induced injury via upregulation of microRNA-138. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.L.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.Y.; Yang, L.L.; Chen, N.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.Y. Hyperoside protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling via the AKT signaling pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 51, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Li, J.; Rao, T.C.; Fang, Z.R.; Zhang, J.Y. The role and mechanism of hyperoside against myocardial infarction in mice by regulating autophagy via NLRP1 inflammation pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Liu, L.J. Hyperoside prevents sepsis-associated cardiac dysfunction through regulating cardiomyocyte viability and inflammation via inhibiting miR-21. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Q.; Li, B.; Peng, D.; Wang, X.F.; Li, P.; Huang, M.C.; Xing, H.Y.; Chen, J.H. Crm1-dependent nuclear export of Bach1 is involved in the protective effect of hyperoside on oxidative damage in hepatocytes and CCl4-induced acute liver injury. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, C.Z.; Liu, X.J.; Ge, Y.P.; Jiang, X.Y.; Zhao, W. Hyperoside protects against heart failure-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Acta Histochem. 2019, 121, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.T.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Pan, J.H. Hyperoside alleviated N-acetyl-para-amino-phenol-induced acute hepatic injury via Nrf2 activation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.P.; Qiu, X.X.; Dai, M.J.; Zhang, X.B.; Jin, G.X. Hyperoside attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by suppressing oxidative stress and inhibiting apoptosis in rats. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, R.T.; Liang, Z.C.; Fan, A.Q.; Kang, D.M. Hyperoside attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through targeting Nr4A1 in macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 94, 107438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, H.Y.; Fu, R.Q.; Cheng, C.Y.; Cai, Y.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Deng, D.M.; Gong, X.Y.; Chen, J.H. Hyperoside protected against oxidative stress-induced liver injuryviathe PHLPP2-AKT-GSK-3 beta signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, M.M.; Dong, H.H.; Yu, X.M.; Zhang, J.F. Anti-hypoglycemic and hepatocyte-protective effects of hyperoside from Zanthoxylum bungeanum leaves in mice with high-carbohydrate/high-fat diet and alloxan-induced diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, F.F.; Chen, Z.Z.; Xu, Y.W.; Wan, H.F.; Lin, H.Y. Study on mechanism of hyperoside protecting cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Chin. J. Mod. Appl. Pharm. 2021, 38, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.H. Mechanism of Hyperoside Regulating Cerebrovascular trpv4 through ip3/pkc Signaling Pathway to Ameliorate Ischemic Cerebral Apoplexy. Master’s Thesis, WanNan Medical College, Wuhu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Xiong, Y.; Peng, A.L. Brain protective effect of Lilium lancifolium hypericin on rats with cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.T.; Li, H.Q.; Li, G.F.; Yang, L. Hyperoside protects against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by alleviating oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in rats. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yildiz Deniz, G.; Altun, S. Evaluation of nickel-induced brain injuries in rats via oxidative stress and apoptosis: Attenuating effects of hyperoside. Turk. J. Zool. 2020, 44, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.Z. Protective Effect of Hyperoside on LPS-Induced Acute Kidney Injury and the Underlying Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.H. Hyperoside Attenuates Renal Ageing Induced by D-galactose via Regulating AMPK-ULK1 Signalling-Mediated Autophagy. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Ye, L.H.; Li, W.J.; Li, D.Z.; Li, F. Hyperoside protects human kidney-2 cells against oxidative damage induced by oxalic acid. Mol Med Rep. 2018, 18, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.H.; Tu, Y.; He, W.M.; Liu, Y.L.; Wu, W.; Fang, Q.J.; Tang, H.T.; Tang, R.M.; Wan, Z.Y.; Sun, W.; et al. Hyperoside attenuates renal aging and injury induced by D-galactose via inhibiting AMPK-ULK1 signaling-mediated autophagy. Aging-Us 2018, 10, 4197–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.M.; An, X.F.; Huang, Z.M.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Y.G.; Xing, C.Y. Protective effect of hyperoside against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via modulating mitochondrial fission, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Res. 2019, 53, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Dai, Q.; Hu, L.L.; Yu, H.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, J.Y.; Long, M.; Zhou, S.W.; Zhang, K.B. Hyperoside alleviates high glucose-induced proliferation of mesangial cells through the inhibition of the ERK/CREB/miRNA-34a signaling pathway. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 2020, 1361924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.B.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.Y.; Lou, Y.; Bao, J.J.; Yu, J.Y. Hyperoside ameliorates diabetic nephropathy induced by STZ via targeting the miR-499-5p/APC axis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 146, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.X.; Li, L.M.; Shi, J.Q. Effects and mechanism of hyperin against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Chin. J. Public Health 2018, 34, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Fan, X.Y.; Gu, W.J.; Ci, X.X.; Peng, L.P. Hyperoside relieves particulate matter-induced lung injury by inhibiting AMPK/mTOR-mediated autophagy deregulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 167, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.Z.; Tong, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.G.; Zhang, S.J.; Fan, H. Hyperoside attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis development in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 550955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.H.; Lu, J.M.; Chen, S.H.; Zhang, X.G.; Mao, W.W. Hyperoside inhibits proinflammatory cytokines in human lung epithelial cells infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 453, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Min, D.Y.; Zhu, J.H.; Yuan, Y.; Guan, X.J.; Hu, L.P. Experimental study of hyperoside on process of atherosclerosis by regulating vascular endothelium via NOS/NO system. Drug Eval. Res. 2021, 44, 971–977. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Guo, C.L.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, M.L.; Hou, Y.L. The antihypertensive effect of hyperoside as a inhibitor of ACE. Pharmacol. Clin. Chin. Mater. Med. 2018, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.A.; Park, D.W.; Sohn, E.H.; Lee, S.R.; Kang, S.C. Hyperoside suppresses tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated vascular inflammatory responses by downregulating mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Zuo, R.T. Effects of hyperin on sacroiliacjoint of mice with IL-1β-induced chondrocyte injury. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2021, 43, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Dai, F.; He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Q.; Cheng, G.; Lu, Y.X.; Zhang, Q. Beneficial effects of hyperoside on bone metabolism in ovariectomized mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.C.; Li, B.; Wu, W.L.; Liu, H.C.; Jiang, Y.P. Protective effect of hyperoside against hydrogen peroxide-induced dysfunction and oxidative stress in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2020, 48, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.F. Hyperoside decreases the apoptosis and autophagy rates of osteoblast MC3T3-E1 cells by regulating TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis and the p38mitogen activated protein kinase pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, Q.; Jin, X.N.; Gao, Y.Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, P. Effect of hyperoside on synoviocytes of rheumatoid arthritis and its mechanism. J. Jinzhou Med. Uni. 2020, 41, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.N.; Gao, W.; Feng, X.; Sui, H.J.; Fu, Q. Therapeutic effect of hyperoside on mice with collagen-induced arthritis. J. Pract. Med. 2021, 37, 2199–2203. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.; Kong, F.Y.; Liang, R.M. Effect of Hyperoside on LPS-induced osteoarthritis in vitro. J. Snake 2020, 32, 420–423. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Luo, J.H.; Jing, X.Z.; Xiang, W.; Guo, J.C.; Yao, X.D.; Liang, S.; Guo, F.J.; Xu, T. Hyperoside ameliorates the progression of osteoarthritis: An in vitro and in vivo study. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.P.; Cai, Y.Q.; Zhou, S.Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, W.Y.; Li, X.L. Therapeutic effect of hyperoside in rats with ulcerative colitis and its mechanism. Immunol. J. 2021, 37, 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.R.; Tan, Y. The effect and mechanism of hyperin on ovarian reserve of tripterygium glycosides-induced POI mice. J. Sichuan Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 52, 458–466. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.X.; Fan, G.M.; Wei, F.M.; Bu, Y.; Huang, W.H. Hyperoside protects rat ovarian granulosa cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury by sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 310, 108759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.B.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.Y.; Lou, Y.; Yu, J.Y. Hyperoside protects HK-2 cells against high glucose-induced apoptosis and inflammation via the miR-499a-5p/NRIP1 pathway. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 629829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jin, H.L.; Jang, D.S.; Jeong, K.W.; Choung, S.Y. Hyperoside (quercetin-3-O-beta-D-galactopyranoside) protects A2E-laden retinal pigmented epithelium cells against UVA and blue light-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xie, Z.L.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.Q.; Bi, X.T.; Yang, X.; Li, B.; Chen, J.H. Hyperoside ameliorates diabetic retinopathy via anti-oxidation, inhibiting cell damage and apoptosis induced by high glucose. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, Y.; Yan, C.T.; Zhuge, N.S.; Yu, J.H. Hyperoside ameliorates periodontitis in rats by promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs via activation of the NF-kappa B pathway. Febs. Open Bio. 2020, 10, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, X.Y.; Li, H.B. Study on the inhibitory effects of hyperoside on lipopolysaccharides-induced inflammatory response in mouse macrophage RAW264.7. Chin. J. Basic Med. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 27, 944–949. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.T.; Zhao, X.Y.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.W.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.B. Hyperoside suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Curr. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Yu, X.M.; Wang, M.M.; Ding, Y.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.K.; Cheng, Y. Hyperoside from Z. bungeanum leaves restores insulin secretion and mitochondrial function by regulating pancreatic cellular redox status in diabetic mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 162, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkoz, M. Effect of hyperoside on the inhibition of adipogenesis in 3t3-L1 adipocytes. Acta Endocrinol. (Buchar. Rom.) 2019, 15, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, X.M.; Gao, J.Y. Study on the effects and mechanism of hyperoside on anti-fatigue in mice. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2021, 42, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.N.; Lv, X.T.; Sun, L.Q.; Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, Z.H. Enhancement of NK cells proliferation and function by hyperoside. Chin. J. Immunol. 2019, 35, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A.W.; Song, Y.L.; Ni, T.T.; Xiao, H.D.Z.; Wan, Y.R.; Ren, X.X.; Li, H.J.; Xu, G.L. Hyperoside attenuates pregnancy loss through activating autophagy and suppressing inflammation in a rat model. Life Sci. 2020, 254, 117735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.W.; Xiao, H.D.Z.; Xu, G.L.; Yu, X.L.; Guo, J.J.; Jing, Z.Q.; Shi, S.Q.; Song, Y.L. Hyperoside protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against anticardiolipin antibody-induced injury by activating autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zheng, R.; Baade, P.D.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, H.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A.; Yu, X.Q.; He, J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiller, J.H.; David, H.; Belani, C.P.; Corey, L.; Alan, S.; James, K.; Junming, Z.; Johnson, D.H.; Group, E. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 346, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlos, S.J.; De, A.; Dias, G.; Chada, B.E. Cervical cancer: What’s new? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2015, 61, 536–542. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa, A.; Ichikawa, H.; Kubo, T.; Motoi, N.; Kumamoto, T.; Nakajima, M.; Yonemori, K.; Noguchi, E.; Sunami, K.; Shiraishi, K.; et al. Vaginal transmission of cancer from mothers with cervical cancer to infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.L. Diet and health care of patients with liver cancer. Diet and Health 2020, 18, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.X. Hyperoside Inhibits Tumor Progress by Targeting YY1-p65 Complex. Master’s Thesis, Nankai University, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.Y.; Jia, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.Q. Metabolomics analysis reveals the protective effect of quercetin-3-O-galactoside (Hyperoside) on liver injury in mice induced by acetaminophen. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.T.; Shen, S.J.; Sun, Q. Current situation and progress of breast cancer screening in China. Chin. J. Front. Med. Sci. 2020, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ma, C. Protective effect of hyperin on cerebral infarction in rats. Chin. J. Chin. Miner. Med. 1998, 23, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhao, W. Protective effect of hyperin against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Acta Pharm. Sin. 1998, 33, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, J.S.; Stolz, E.D.; Betti, A.H.; Stein, A.C.; Schripsema, J.; Poser, G.L.; Rates, S.M. The anti-immobility effect of hyperoside on the forced swimming test in rats is mediated by the D2-like receptors activation. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, M.; Huang, D.; Yang, R.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Xiong, Q.; Xiong, Z. Hyperoside protects against chronic mild stress-induced learning and memory deficits. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterweck, V.; Hegger, M.; Winterhoff, H. Flavonoids of St. John’s Wort reduce HPA axis function in the rat. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Xuan, J.L.; Hu, H.R.; Chen, Z.W. Protective effect against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injuries induced by hyperoside preconditioning and its relationship with PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in rats. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2015, 40, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, H.; Fu, R.; Cheng, C.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, D.; Gong, X.; Chen, J. Hyperoside protected against oxidative stress-induced liver injury via the PHLPP2-AKT-GSK-3β signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Xu, Y.F.; Feng, Y.; Peng, B.; Che, J.P.; Liu, M.; Zheng, J.H. Prophylactic effects of quercetin and hyperoside in a calcium oxalate stone forming rat model. Urolithiasis 2014, 42, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, W.; Che, J.P.; Wang, G.C.; Liu, M.; Zheng, J.H. Protective effects of quercetin and hyperoside on renal fibrosis in rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 8, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, W.T.; Hu, L.P. Prediction of target and mechanism of hyperoside in atherosclerosis treatment by using network pharmacology methods. Mod. Chin. Med. 2018, 20, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.T.; Su, M.T.; Gao, H.; Liang, J.L.; Du, B.L.; Cao, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.Z. Effects of hypericin on blood lipid and arterial plaque formation in ApoE -/- mice. Chin. Pract. Med. 2018, 13, 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Yamada, M.; Kim, B.K.; Ohuchi, K.; Shin, K.H. Antiinflammatory activity of hyperin from Acanthopanax chiisanensis roots. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yu, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Flos lonicerae flavonoids attenuate experimental ulcerative colitis in rats via suppression of NF-κB signaling pathway. Naunyn-Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 2481–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.N.; Xu, Z.H.; Liu, S.B.; Guo, H.J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, F.X.; Sun, X.L.; et al. A role of periaqueductal grey NR2B-containing NMDA receptor in mediating persistent inflammatory pain. Mol. Pain. 2009, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y.T.; Fang, L.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Lan, R.N.; Wang, M.Y.; Du, G.; Guan, W.Q.; Liu, J.F.; Brennan, M.; Guo, H.X.; et al. Antioxidant activity evaluation of dietary flavonoid hyperoside using saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model. Molecules 2019, 24, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Zhang, W.W.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Q.; Cai, H.B.; Tan, W.S. Hyperoside promotes ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells derived from cord blood by reducing intracellular ROS level. Process Biochem. 2018, 72, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X. Analysis of Different Components in Different Parts of Acanthopanax senticosus and Protective Mechanism of Hyperoside in the Oxidative Damage. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.S. Multi-Omics Analysis of the Mechanism in Lipid Metabolism by Hyperinin Mice. Master’s Thesis, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Y. Study on the Preparation of Luteoloside and Hyperoside Reference Materials and Their Antioxidant Activities. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, C.R.; Yuan, S.J. Quantitation of hyperoside in rat plasma by LC/MS and its application to pharmacokinetics study. Guiding J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharm. 2020, 26, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.F. Determination of hyperoside in the extract of Senecionis Scandens herba and Qianbai Biyan capsule by HPLC and its pharmacokinetics in rats. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2019, 48, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.S.; Wu, D.L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.S.; Xu, F.Q.; Wang, T.S. Effects of different compatibilities of Wuzi Yanzong pill on the absorption and distribution of hyperoside in rats. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 2021, 41, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.S. Effects of Different Compatibility on the Content and Pharmacokinetics of Hyperoside in Cuscuta chinensis Lam. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hefei, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.J.; Wang, J.J.; An, X.F.; Dai, M.X.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Zhang, L.Y.; Yu, S.; Huang, X. UPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of hyperoside and application to pharmacokinetics study in rat after different administration routes. Chromatographia 2021, 84, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.Y.; Jia, Z.; Han, T.; Liu, M.N.; Jia, T.Y.; Qu, W.J.; Xu, X.F.; Li, X.R. UPLC-MS/MS determination of chlorogenic acid, hyperoside and astragalin in plasma and its pharmacokinetic application in liver injury rats. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 17, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, G.; Huang, Z.M.; Wang, D.W.; Zhang, H.C. Acute toxicity and genotoxicity evaluation of hyperoside extracted from Abelmoschus manihot (L.). Medic. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 21, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, G.; Huang, Z.M.; Wang, D.W.; Liu, Z.P. Study on toxicity of hyperoside in rat embryo-fetal development. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2012, 37, 2452–2455. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, G.; Huang, Z.M.; Wang, D.W.; Zhang, H.D. Toxicity of hyperoside after long-term oral administration in wistar rats. Chin. J. New Drugs. 2012, 21, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).