Abstract

Marigold (Calendula), an important asteraceous genus, has a history of many centuries of therapeutic use in traditional and officinal medicines all over the world. The scientific study of Calendula metabolites was initiated at the end of the 18th century and has been successfully performed for more than a century. The result is an investigation of five species (i.e., C. officinalis, C. arvensis, C. suffruticosa, C. stellata, and C. tripterocarpa) and the discovery of 656 metabolites (i.e., mono-, sesqui-, di-, and triterpenes, phenols, coumarins, hydroxycinnamates, flavonoids, fatty acids, carbohydrates, etc.), which are discussed in this review. The identified compounds were analyzed by various separation techniques as gas chromatography and liquid chromatography which are summarized here. Thus, the genus Calendula is still a high-demand plant-based medicine and a valuable bioactive agent, and research on it will continue for a long time.

1. Introduction

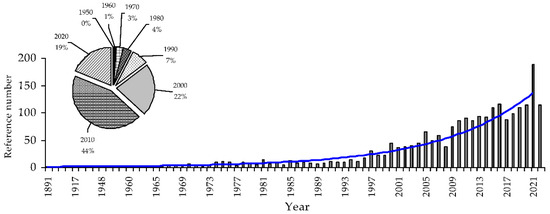

Calendula (marigold; Caléndula L.) is a genus of herbaceous plants from the Asteraceae family, whose members are widely used for medicinal and decorative purposes. Genus Calendula includes 12 species of which Calendula officinalis L. is the most famous plant and the oldest medical remedy [1]. To date, experimental science has accumulated a considerable amount of scientific information about this genus; therefore, we performed a scientometric study of the available information. There are more than 2200 articles related to the study of the Calendula species for the period of 1891–2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of studies on plant species from the Calendula genus by year (1891–2022) and an exponential ‘curve of interest’ (blue line). The X-axis is the year, and the Y-axis is the number of publications. The inset shows the impact of each decade on the total publication value.

Statistical studies indicate an exponential growth in scientific interest in Calendula; the value of the determination coefficient (r2) for the ‘curve of interest’ (Y = 0.6718·e0.0726·X) is 0.9435, which indicates the reliability of these statements. Thus far, the greatest scientific impact on the total number of studies on Calendula was made during 2010–2019 (44% of publications); however, because during 2020–2022, approximately 19% of studies on this topic were completed, the picture may change in the near future. Among the scientific areas in which Calendula research is performed, the agricultural and biological (approximately 38% of publications), medical (approximately 28%), and pharmacology/toxicology sciences (approximately 25%) occupy a predominant position (Table S1). The largest number of works published by authors are from India (208), USA (200), Iran (189), Brazil (158), and Italy (148), and the authors with the largest number of articles are Kasprzyl Z. (35), Janiszowska W. (33), Szakiel A. (24), and Bransard G. (10). The top 10 most-cited articles with more than 100 citations include studies on chemical composition (triterpenoids, lipids), biological activity (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, hypoglycemic), as well as clinical trials and allergic properties [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] (Table S2).

As expected, this level of scientific interest has led to the fact that review papers on various Calendula aspects are published in the scientific literature with varying frequency. In total, twelve reviews have been published from 2006 to 2022 (Table 1). All identified review articles had an important goal of generalizing data on the pharmacological activity of Calendula extracts to the detriment of information on the chemical composition. As a result, the total number of compounds mentioned in these works was 0–155. The work that cites the largest number of compounds (155) was published in 2009; therefore, this information needs to be updated. None of the reviews summarized data on the methods of analysis and/or separation of Calendula metabolites, which is a very important aspect of practical research of plant samples. Therefore, the aim of this work is to summarize the scientific information about the Calendula genus regarding the metabolite’s diversity as well as methods of analysis and separation.

Table 1.

Review articles aimed at Calendula research.

2. Review Strategy

The resources of international databases (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar) were used, and only original papers written in English and published in journals prior to October 2022 were considered. The search keywords used included plant names (e.g., “Calendula”, “Calendula officinalis”, etc.) and metabolite names. Metabolites with tentative structure (e.g., “quercetin-O-desoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside”, etc.) were excluded from the study. The structures of well-known metabolites (e.g., monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, fatty acids, amino acids, etc.) are not discussed in this paper.

3. Chemodiversity of Calendula Genus

Some of the earliest chemical studies of the Calendula genus are the reports of F.A. Wirth (1891) [24], A. Kirchner (1892) [25], and A. Hilger (1894) [26] on the coloring pigments of C. officinalis flowers, which indicated the presence of phytosterols and some esters. Later, H. Kylin (1926) determined that the color of marigold flowers was primarily due to the carotenoid pigment calendulin, which differs from carotene; in 1932, L. Zechmeister and L. von Cholnoky characterized calendulin as a mixture of lycopene and violaxanthin [27]. Research on C. officinalis carotenoids was continued only in 1951 [28], after which investigations of the metabolites of this species and the genus became regular and have continued to this day for more than 70 years.

The chemical studies of Calendula genus metabolites include five species: C. officinalis or pot marigold (common marigold) is the most famous and widely distributed medicinal plant; C. arvensis or field marigold and C. suffruticosa or bush marigold are native to Central and Southern Europe; C. stellata or star marigold is grown in Northwestern Africa, Malta, and Sicily; and small tripterous marigold C. tripterocarpum occurs in Spain, Iran, and Africa. During 1892–2022, more than 650 compounds (1–656) have been identified for the genus Calendula, including monoterpenes (1–44), sesquiterpenes (45–173) and sesquiterpene glycosides (174–207), diterpenes (208, 209), triterpenes (210–342), carotenoids (343–437), phenols (438–443), benzoic acid derivatives (444–456), hydroxycinnamates (457–478), coumarins (479–488), flavonols (489–516), anthocyanins (517–524), alkanes (525–550), aliphatic alcohols (551–559), aliphatic aldehydes and ketones (560–565), fatty acids and esters (566–602), chromanols (603–613), organic acids (614–616), carbohydrates (617–630), amino acids (631–646), and other groups (647–656) (Table 2). In addition, several polysaccharides have been isolated and characterized. Among the species mentioned, the most studied is C. officinalis for which 529 compounds are known, followed by C. arvensis (187 comp.), C. suffruticosa (68 comp.), C. stellata (27 comp.), and C. tripterocarpa (5 comp.). In terms of the organ-specific distribution of known metabolites of C. officinalis, the flowers are the best-studied part and are known to contain 403 compounds, while the leaves, roots, and seeds are known to contain 138 compounds. Studies on other species have been performed mainly on samples of the aerial part.

Table 2.

Compounds 1–656 found in Calendula plants.

3.1. Monoterpenes

Monoterpenes 1–44 were found in the essential oils of C. officinalis, C. arvensis, and C. stellata herb, flowers, and leaves [16,29,30,31,32,33,34]. The typical compounds of the Calendula genus are linalool (15), limonene (17), β-myrcene (21), α/β-pinene (27/29), sabinene (33), γ-terpinene (40), terpinene-4-ol (42), α-terpinolene (43), and α-tujene (44) because these are routinely identified in essential oil samples using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). These compounds are likely responsible for the characteristic odor of marigold flowers, although this has not been confirmed by olfactory analysis.

3.2. Sesquiterpenes

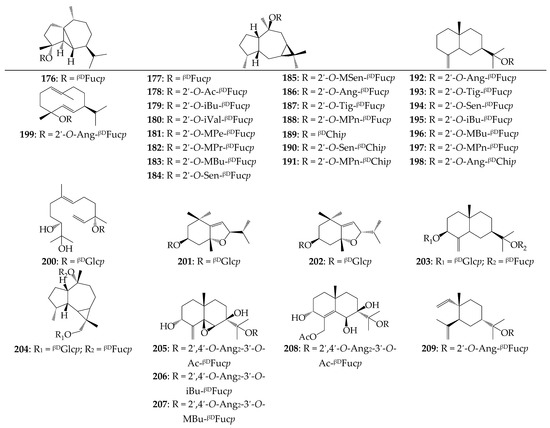

A total of 163 compounds of sesquiterpene nature were detected or isolated from four calendulas, i.e., 129 non-glycosidic compounds (45–173) and 34 glycosides (174–207) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sesquiterpenes 176–209. Ac—acetyl; Ang—angeloyl; But—butyl; dCrt—dicrotaloyl; βDChip—β-D-chinovopyranose; βDFucp—β-D-fucopyranose; iBu—isobutyryl; iVal—isovaleroyl; βDGlcp—β-D-glucopyranose; MBu—methylbutenoyl; MPe—methylpentenoyl; MPn—3-methyl-2-pentenoyl; MPr—methylpropanoyl; MSen—4-methylsenecioyl; Sen—senecioyl; Tig—tigloyl.

All non-glycosides were detected in the essential oils of C. arvensis, C. officinalis, and C. suffruticosa [30,31,37]. Structurally, derivatives of cadinane, carotane, caryophyllane, cubebane, eromophyllane, eudesmane, muurolane, and selinane dominated in all samples studied.

The sesquiterpene glycosides of the Calendula genus (a rare group of natural terpenoids) have attracted much greater interest. The first compound, arvoside A (174), isolated from C. arvensis, is a very rare 4-epi-cubebol glycoside [44]. Later, viridiflorol derivatives (175–189) were found in C. arvensis (as C. persica) and C. officinalis. This is the largest group of sesquiterpene glycosides in which hydroxyl can be substituted by fucose or chinovose acylated by acetic [44], isobutyric [45], isovaleric [44], methylpentenoic [44,46], methylpropanoic [47,48], methylbutenoic [46,47], senecic [45,46], 4-methylsenecic [46], angelic [45], and tiglic acids [45]. Similar to viridiflorol fucosides and chinovosides of β-eudesmol, 190–196 were identified in C. arvensis [46] and C. officinalis [45]. Rare angeloyl fucosides of 4α-hydroxygermacra-1(10)E,5E-diene (197) [46], α-elemol (207) [45], and 3α,7β-dihydroxy-5β,6β-epoxyeudesm-4(15)-ene (203–208) [48], as well as megastigmane glucosides officinoside A (199) and B (200) [50], icariside C3 (198) [9], and glucosyl fucosides officinoside C (201) and D (202) [50] showed the unique sesquiterpene profile of Calendula plants.

3.3. Diterpenes

Two diterpenes, neophytadiene (176) and phytol (177), were identified in the essential oils of C. arvensis, C. officinalis, and C. suffruticosa [40,41].

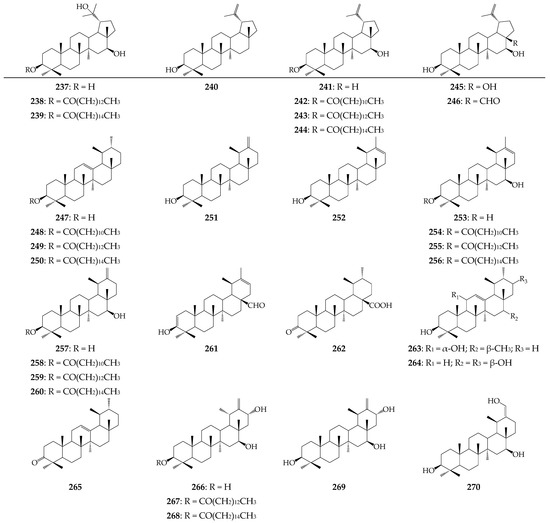

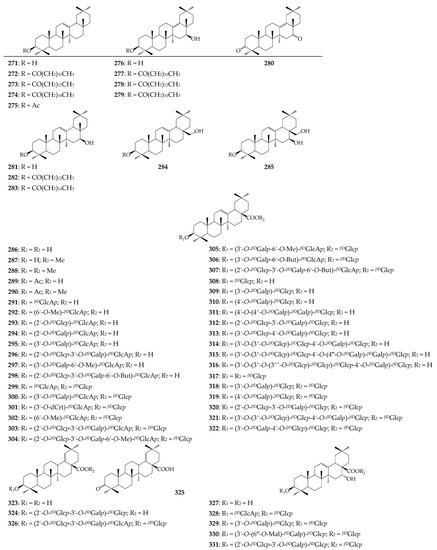

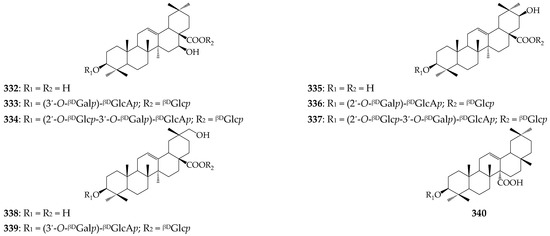

3.4. Triterpenes

Triterpenes of the genus Calendula are present in plants both in the free state and as esters with fatty acids (lauric, myristic, palmitic) or alcohols (methanol, n-butanol), as well as in the glycosidic form. Isolated and characterized compounds were derived from eleven parent structures, including stigmastane (211–220), ergostane (221–224), cholestane (225–229), lanostane (230, 231), dammarane (232), cycloartane (233, 234), fridelane (235, 236), lupane (237–246; Figure 3), ursane (247–270; Figure 3), oleanane (271–340; Figure 4) and tirucallane (341, 342). The only aliphatic triterpene squalene (210) was found in C. suffruticosa [42]. Stigmastanes, ergostanes, cholestanes, and lanostanes represent sterol derivatives of the Calendula genus that are most abundant in C. officinalis [51,58,59]. Cycloartanes, fridelanes, lupanes, and ursanes are non-glycosidic compounds that exist in the form of alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones. Selected lupanes (lupane-3β,16β,20-triol, calenduladiol) and ursanes (α-amyrin, faradiol, arnidiol, arnitriol) are esterified by lauric, myristic, and palmitic acids [53,56,60].

Figure 3.

Lupane derivatives 237–246 and ursane derivatives 247–270.

Figure 4.

Oleanane derivatives 271–340. Ac—acetyl; βDGalp—β-D-galactopyranose; βDGlcp—β-D-glucopyranose; βDGlcAp—β-D-glucuronopyranose; Mal—malonyl; Me—methyl.

In the oleanane group, oleanolic acid (286) and derivatives (287–322) have shown the largest diversity. The structural features of oleanolic acid glycosides that distinguish Calendula from other Compositae species are the ability to form mono- and oligoglycosides with one and/or two points of attachment of carbohydrate fragments at the C-3 and C-28 positions. Two types of glycosides have been identified in Calendula plants, i.e., acidic and neutral. Acidic glycosides contain a glucuronic acid fragment at C-3, which can be linked to glucose and galactose at C-2′, galactose at C-3′, and/or esterified at C-6′ with methanol or butanol. Neutral glycosides are characterized by some differences; after the addition of glucose to C-3, a complication of the structure has been observed as a result of the introduction of additional glucose fragments at C-2′, galactose, glucose, di- and tri-glucosyl fragments at C-3′, and also glucose, galactose, and a di-galactosyl moiety at C-4′. At position C-28 of oleanolic acid, only glucose can exist.

Glycosides of other triterpene acids (e.g., morolic acid (323), moronic acid (325), echinocystic acid (327), cochalic acid (332), machaerinic acid (335), and mesembryanthemoidigenic acid (338)) are both neutral and/or acidic derivatives.

In C. officinalis, two compounds related to rare 3,4-seco-terpene alcohols, which are derivatives of tirucallan (3,4-seco-cucurbitane or 3,4-seco-19(10→9)abeo-euphane), have been identified as helianol (341) and thirucalla-7,24-dienol (342) [3]. Previously, both compounds were found in tubular flowers of Helianthus annus L. [110].

The most distributed triterpene glycoside is glucoside D (295), which has been found in four species: C. arvensis, C. officinalis, C. stellata, and C. suffruticosa. Three species (C. arvensis, C. officinalis, C. stellata) contain glucoside C (300), calenduloside C (312), and calenduloside D (320), and seven glycosides (293, 299, 303, 309, 318, 319, 333) were identified in two species. Triterpenoids are quantitatively the main group of Calendula metabolites, which reaches up to 3–4% of the total level of fatty esters of faradiol, arnidiol, and calenduladiol [58], and up to 9% of triterpenoid glycosides [111].

Scientometric studies have shown a number of mismatches in the names of some triterpenoid glycosides; specifically, for individual compounds, several trivial names are used. For the first time, six glycosides of oleanolic acid (containing a glucuronic acid residue at the C-3 position of the aglycone) were isolated from the flowers of C. officinalis and characterized by Kasprzyk Z. and Wojciechowski Z. in 1967, giving them the names glucosides A (291), B (293), C (295), D (296), E (300), and F (303) [67]. Later, Wojciechowski Z. et al. (1971) established the existence of a second group of oleanolic acid glycosides in C. officinalis containing a glucose residue at the C-3 position of the aglycone, named glucosides I (308), II (310), III (311), IV (313), V (314), VI (315), VII (316), and VIII (321) [71]. The latter research group used other names for glycosides A–F, such as glucuronides A–F, which are still relevant [112]. Therefore, the question of the priority of names for compounds 291, 293, 295, 296, 300, and 303 remains open; the use of both variants is legitimate. Of note, the variants of names for glucosides C (295), D (296), and F (303), such as calendulosides H, G, and E, respectively, proposed by Vecherko L.P. et al., who isolated these compounds from C. officinalis in 1975–1976 [69,74,76,79,80,81], can be considered as synonyms. Calenduloside F (299) was isolated and characterized by Vecherko L.P. et al. (1975) [76]; however, the final identification of this compound under the name glucoside D2 was performed by Vidal-Oliver E. (1989) [70]. Later, compound 299 was also named glucuronide D2 [9].

3.5. Carotenoids

Since the discovery of carotene, lycopene, and violaxanthin in pigmented marigold petals [27], approximately a hundred carotenoids (343–437) have been found and identified in C. officinalis. Only this species was studied for this group of compounds. Carotenoids have been found in free and esterified forms, including myristic, palmitic, and stearic acid mono- and di-esters [85]. The most diverse carotenoid aglycone is lutein, which forms 32 compounds (376–407), followed by violaxanthin (418–428), cryptoxanthin (362–369), and zeaxanthin (429–434). Owing to the wide variety of colors of calendula flowers (ranging from white to burgundy and maroon), different varieties have different levels of carotenoids, ranging from trace amounts to 200 mg per 100 g of dry flower petals [113,114].

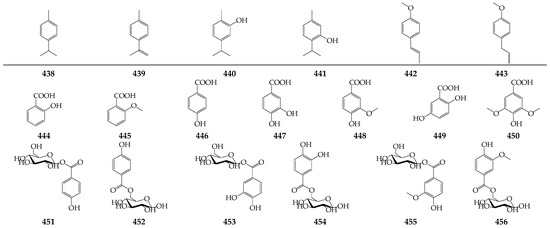

3.6. Phenols

Six simple phenols (i.e., p-cymene (438), p-cymenene (439), carvacrol (440), thymol (441), p-anethole (442), and estragole (443)) are the minor constituents of the essential oil of C. officinalis [30,35,36] and C. arvensis [16] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Phenols 438–443 and benzoic acid derivatives 444–456.

3.7. Benzoic Acid Derivatives

Seven simple benzoic acids were identified as minor components of methanolic and ethanolic extracts of C. officinalis flowers, including salicylic acid (444), o-anisic acid (445), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (446), protocatechuic acid (447), vanillic acid (448), gentisic acid (449), and syringic acid (450) [35,87,89] (Figure 5). Later, six glucosides of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (451, 452), protocatechuic acid (453, 454), and vanillic acid (455, 456) were identified in leaves and pollen of C. officinalis [90,91].

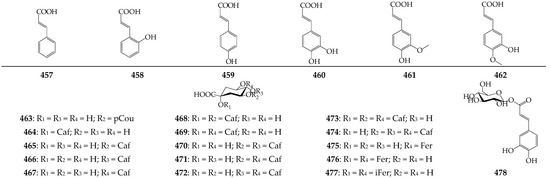

3.8. Hydroxycinnamates

Twenty two derivatives of cinnamic acid of Calendula genus (i.e., cinnamic acid (457), coumaric acids (458, 459), caffeic acid (460), ferulic acid (461), isoferulic acid (462), mono-O-caffeoyl quinic acids (464–467), di-O-caffeoyl quinic acids (468–472), tri-O-caffeoyl quinic acids (473, 474), 5-O-feruloylquinic acid (475), 1,5-di-O-feruloylquinic acid (476), 1,5-di-O-isoferuloylquinic acid (477), and 1-O-caffeoyl glucose (478)) were identified in the herb, roots, and pollen of C. arvensis, C. officinalis, C. suffruticosa, and C. tripterocarpa [75,89,92] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hydroxycinnamates 457–478. Caf—caffeoyl; pCou—p-coumaroyl; Fer—feruloyl; iFer—isoferuloyl.

Hydroxycinnamates are typical metabolites of asteraceous plants [115]; therefore, it is not surprising that they have been identified in calendulas. The dominant hydroxycinnamates in the flowers (3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (465) and 3,5-di-O-caffeoyl quinic acid (471)) amounted to 1–7 mg/g for 465 and 0.5–2 mg/g for 471; while in the leaves, the content of 465 can reach 9 mg/g [89].

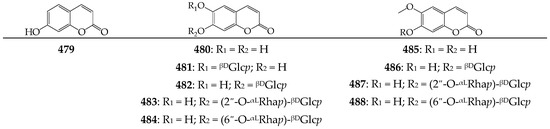

3.9. Coumarins

A small group of α-pyrone compounds or coumarins (ten compounds (479–488)) has been identified in small amounts in the flowers, leaves, and herb of C. officinalis [90,94,95] and C. tripterocarpa [92], including umbelliferone (479), esculetin (480) and glycosides (481–484), scopoletin (485), and glycosides (486–488) (Figure 7). The carbohydrate moieties of glycosides contain a glycose in esculin (481), cichoriin (482), and scopolin (486), neohesperidose in neoisobaisseoside (483) and haploperoside D (487), and rutinose in haploperoside (484) and isobaisseoside (488).

Figure 7.

Coumarins 479–488. βDGlcp—β-D-glucopyranose; αLRhap—α-L-rhamnopyranose.

3.10. Flavonoids and Anthocyanins

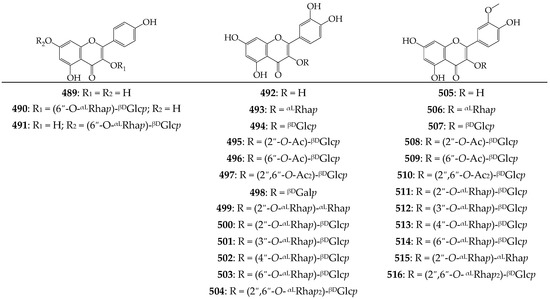

Since the discovery of isorhamnetin (505), isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside (507), and narcissin (514) in C. officinalis flowers in 1962 [116,117], twenty-eight flavonoids of C. arvensis, C. officinalis, C. stellata, C. suffruticosa, and C. tripterocarpa were also identified; the glycosyl derivatives of kaempferol (489–491), quercetin (492–504), and isorhamnetin (505–516) are the predominant forms of flavonoids (Figure 8). Carbohydrate fragments may exist as monosaccharides (incorporate one moiety of rhamnose, galactose, and glucose), disaccharides (including neohesperidose (2-O-ramnosylglucose), such as calendoflavobioside (500) and calendoflavoside (511) [97]; rungiose (3-O-ramnosylglucose) such as calendoside II (501) and IV (512) [91]; 4-O-ramnosylglucose, such as calendoside I (502) and III (513) [91]; rutinose (6-O-ramnosylglucose), such as nicotiflorin (490), kaempferol-7-O-rutinoside (491), rutin (503), and narcissin (514) [93,97,98]; and 2-O-ramnosylrhamnose, such as quercetin-3-O-(2″-O-ramnosyl)-rhamnoside (499) and calendoflaside (515) [97]), and trisaccharides (2,6-di-O-ramnosylglucose in manghaslin (504) and thyphaneoside (516) [98,100]). Monoglucosides of quercetin and isorhamnetin may sometimes be acylated by acetic acid giving mono- (495, 496, 508, 509) or diacetates (497, 510) [89,91]. The content of flavonoids in different parts varies from trace amounts in the roots and seeds to 2–4% in the tubular and ligular flowers; isorhamnetin derivatives are typically the major components [89,114]. Anthocyanins 517–524, as components of red colored marigold ray florets, are glycosides of cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, paeonidin, pelargonidin, and petunidin with a total content of 0.6–1.2% [89].

Figure 8.

Flavonoids 489–516. Ac—acetyl; βDGalp—β-D-galactopyranose; βDGlcp—β-D-glucopyranose; αLRhap—α-L-rhamnopyranose.

3.11. Other Compounds

Highly lipophilic compounds found in essential oils and hexane fractions of C. arvensis, C. officinalis, and C. suffruticosa include alkanes (525–550), aliphatic alcohols (551–559), aliphatic aldehydes and ketones (560–565), fatty acids and esters (566–602), and chromanols (603–613) [33,34,36,39]. In methanolic and water extracts of Calendula species, various hydrophilic compounds have been identified, including organic acids (614–616), carbohydrates (617–630), and amino acids (631–646) [41,108]. In essential oils of C. officinalis, 3-cyclohexene-1-ol, 3-cyclohexene-1-ol 4-methyl ester, loliolide, 1,2,3,5,8,8α-hexahydronaphthalene 6,7-dimethyl ester, 4-methylacethophenone, and 1-methyl ethyl hexadecanoate were identified [30,31,35,109]; tricyclene, 1H-benzocyclohepten-9-ol, and 2-pentyl furane were identified in C. arvensis [16,33,41]; naphthalene was detected in C. suffruticosa [42].

3.12. Polysaccharides

The study of Calendula polysaccharides started in the mid-1980s [118] and refers only to C. officinalis flowers; none of the other species have been studied (Table 3). A group of German researchers conducted a systematic study of plant polysaccharides and their immunostimulating properties [8]. After the 0.5 M NaOH extraction of C. officinalis flowers, three neutral polysaccharides were isolated and characterized as rhamnoarabino-3,6-galactan and two arabino-3,6-galactans [119].

Table 3.

Source of polysaccharides of C. officinalis, extractant, monaccharide composition, yeld, molecular weight (MW), and fine structure.

Later, five water-soluble polymers with 24.1–57.2 mol% of uronic acids were identified and demonstrated a wide variation of arabinose (4.0–12.5 mol%) and galactose (14.1–40.8 mol%) levels [120]. Polysaccharide fractions were also isolated from the industrial C. officinalis flower wastes; a high uronic content was typical for them (58.3–64.0 mol%) as well as variation in the level of neutral monosaccharides [121,122]. The exact structure of the acidic polysaccharides of C. officinalis is still unknown.

4. Separation of Calendula Metabolites by GC and LC

The chemical characteristics and chromatographic properties of the Calendula metabolites determine which technique is used to achieve satisfactory separation of target compounds. Some differences exist between gas chromatography and liquid chromatography (LC) methods designed for analyzing sterols, triterpenes, carotenoids, fatty acids, and phenolic compounds that are found in Calendula plants (Table 4).

4.1. Sterols

Both GC and LC techniques were designed to separate sterols with various structures. Various 30 m columns (e.g., ZB-1 [123], HP-5MS UI [124], DB 17 [3], and RTX®-1 MS [56]) were used to analyze sterol alcohols and esters by GC with flame ionization detection (GC-FID) and mass spectrometric detection (GC-MS). Fatty acid esters of arnitriol, faradiol, arnidiol, and maniladiol demonstrated appropriate LC separation on 250 mm reversed-phase (RP) columns (e.g., LiChrosphere RP-8 [125] and RP-18e [126], Hypersil ODS [60], Nucleosil 100-5 C18 [58], and Superiorex ODS C18 [3]) using isocratic elution with methanol [3,60,125], a water–methanol mixture [58], as well as gradient elution with trifluoroacetic acid–methanol mixtures [126,127,128] and ultraviolet (UV) or diode array (DAD) detection at 210 nm. Shorter columns (e.g., Kinetex C18 (100 mm) and Kromasil 100Å (50 mm)) showed good separation of 10 sterol esters by LC with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometric detection (LC-APCI-QTOF-MS) [56].

4.2. Triterpenes and Glycosides

Aglycones (oleanolic acids) and glycosides were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography with UV (HPLC-UV) and mass-spectrometric detection (HPLC-UV-MS) assays using 250 mm (KromaPhase C18 [129], Eurospher 100 C18 [130]) and 150 mm RP columns (Waters Sunfire RP C18 [111], C18 Luna [131]) with isocratic [129] or gradient elution in mixtures of acetic acid and acetonitrile [111,130,131]. Detection at 205–215 nm and MS detection in negative ionization mode allowed the analysis of two to six components [111,129,130,131].

4.3. Carotenoids

The chromatographic separation of Calendula carotenoids was realized using HPLC with diode-array detection (DAD) and HPLC-UV-MS techniques. To qualitatively and quantitatively analyze carotenes, lutein, lycopene, and other pigments, the RP sorbents are traditionally used in 250 mm and in 300 mm columns (e.g., C30 YMC [85], Nucleosil ODS C18 [86], YMC [132], Bondclone C18 [133], Nucleodur C18 [134], and Inertsil ODS-3 C18 [135]). Isocratic elution (with methanol–acetonitrile–methylene chloride–cyclohexene [133], acetone–water [134], methanol–tetrahydrofuran–water [135], and acetonitrile–methanol [136] mixtures) and gradient elution (with acetonitrile–water–ethyl acetate [86] and methanol–methyl tert-butyl ester–water [85,132] mixtures) were successfully performed. The strong absorption of carotenoids in the visible spectral region allowed their detection at 450–474 nm wavelengths [132,133,134,135,136] as well as by MS detection using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) [85].

4.4. Fatty Acids

The fatty acid composition of C. officinalis seeds was extensively studied by GC assays on BPx-70 (60 m) [105], DB-23 (30 m) [137], HP-88 (100 m) [138], and Supelco SP-2560 (100 m) [139] columns and resulted in the quantification of 7–17 compounds with electron impact [105,137,138] and chemical ionization [139] MS detection.

Table 4.

Synopsis of the methods of Calendula extracts analysis, separation conditions, detectors, and separated compounds.

Table 4.

Synopsis of the methods of Calendula extracts analysis, separation conditions, detectors, and separated compounds.

| Assay a, Ref. | Separation Conditions b | Detection | Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterols | |||

| GC-FID [123] | C: Zebron ZB-1 (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm; Phenomenex, Torrans, CA, USA) | MS: FID | Oleanolic acid, campesterol, cholesterol, isofucosterol, 24-methylenecycloartanol, sitosterol, sitostanol, stigmasterol, stigmast-7-en-3-ol |

| GC-MS/FID [124] | C: HP-5MS UI (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA) | MS: FID | Oleanolic acid, campesterol, cholesterol, isofucosterol, sitosterol, sitostanol, stigmasterol, tremulone, 24-methylenecycloartanol |

| GC-MS [3] | C: DB 17 (30 m × 0.3 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA) | MS: ESI (70 eV) | Helianol; taraxerol; dammaradienol; α/β-amyrins; cycloartenol; tirucalla-7,24-dienol; lupeol; 24-methylene-cycloartanol; ψ-taraxasterol, taraxasterol |

| GC-MS [56] | C: RTX®-1 MS (30 m × 0.25 mm; Restek, Cartersville, GE, USA) | MS: EI (70 eV) | 3-O-Palmitates and 3-O-myristates of arnidiol, arnitriol A, faradiol, lupane-3β,16β,20-triol, and maniladiol |

| HPLC-UV [125] | C: LiChrosphere RP-8 (250 × 15 mm, 5 μm; Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA); I; E: MeOH | UV: λ 210 nm | 3-O-Palmitate and 3-O-myristate of faradiol |

| HPLC-UV [126,127,128] | C: LiChrosphere RP-18e (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm; Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA); G; E: TFA (A), MeOH (B); 0–50 min 95–100 %B, 50–95 min 100 %B; T 25 °C; ν 1.5 mL/min | UV: λ 210 nm | 3-O-Palmitate, 3-O-myristate and 3-O-laurate of faradiol |

| HPLC-DAD [60] | C: Hypersil ODS (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); I; E: MeOH; ν 1 mL/min | DAD: λ 210 nm | 3-O-Palmitates, 3-O-myristates and 3-O-laurates of faradiol and maniladiol; taraxasterol, β-amyrin |

| HPLC-UV [58] | C: Nucleosil 100-5 C18 (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany); I; E: MeOH-H2O 97:3; ν 1.5 mL/min | UV: λ 210 nm | 3-O-Palmitates, 3-O-myristates and 3-O-laurates of arnidiol, faradiol and calenduladiol |

| HPLC-UV [3] | C: Superiorex ODS C18 (250 × 10 mm, 5 μm; Osaka Soda, Osaka, Japan); I; E: MeOH; ν 4 mL/min | UV: λ 210 nm | Helianol; taraxerol; dammaradienol; α/β-amyrins; cycloartenol; tirucalla-7,24-dienol; lupeol; 24-methylene-cycloartanol; ψ-taraxasterol, taraxasterol |

| LC-APCI-QTOF-MS [56] | 1. C: Kinetex C18 (100 × 3 mm, 2.6 µm; Phenomenex, Torrans, CA, USA); G; E: MeCN (A), MeOH (B); 0–1 min 0%B, 1–10 min 0–100%B, 10–15 min 100%B; ν 400 µL/min 2. C: Kromasil 100Å (50 × 4 mm, 5 µm; Kromasil, Göteborg, Sweden); G; E: MeOH (A), i-PrOH (B); 0–1 min 30%B, 1–25 min 30–100%B, 25–30 min 100%B; ν 1.2 mL/min | MS: CE | 3-O-Palmitates and 3-O-myristates of arnidiol, arnitriol A, faradiol, lupane-3β,16β,20-triol, and maniladiol |

| Triterpenes and Glycosides | |||

| HPLC-UV [129] | C: KromaPhase C18 (250 mm × 4.6, 5 µm; Kromasil, Göteborg, Sweden); I; E: MeCN-H2O 90:10; ν 1 mL/min | UV: λ 210 nm | Oleanolic acid |

| HPLC-UV-MS [130] | C: Eurospher 100 C18 (250 × 4 mm, 5 µm; Knauer, Berlin, Germany); G; E: 0.5% CH3COOH in MeCN (A), 0.5% CH3COOH in H2O (B); 1–15 min 20% A, 15–45 min 46% A, 45–90 min 55% A, 90–100 min 90% A, 100–110 min 20% A; ν 0.6 mL/min | UV: λ 210 nm; MS: neg. | Glycosides A, B; calendulosides H, F, G, E |

| HPLC-UV-MS [111] | C: Waters Sunfire RP C18 (150 × 2.1 mm, 5 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA); G; E: 0.12% CH3COOH in 10% MeCN (A), 0.12% CH3COOH in 100% MeCN (B); 0–3 min 75% A, 3–25 min 75–50% A, 25–28 min 50–25% A, 28–33 min 100% B; ν 0.2 mL/min | UV: λ 205, 215 nm; MS: neg. | Glycosides A, B, C, D, D2 |

| HPLC-UV-MS [131] | C: C18 Luna (150 × 4.6, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrans, CA, USA); G; E: H2O (A), MeCN (B), CH3COOH in 10% MeCN (C); 0–47 min 90%A-O%B-10%C→43%A-47%B-10%C, 0–47 min 0%A-90%B-10%C | UV: λ 210 nm; MS: neg. | Glycosides A, B, C, D, F; calenduloside A |

| Carotenoids | |||

| HPLC-DAD [86] | C: Nucleosil ODS C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany); G; E: MeCN-H2O 9:1 in 0.25% TEA (A), EtOAc in 0.25% TEA (B); 0–10 min 90–50% A, 10–20 min 50–10% A; ν 1 mL/min | DAD: λ 450 nm | Antheraxanthin, carotene (α-, β-, γ-), flavoxanthin, lactucaxanthin, lutein, lycopene, mutatoxanthin, (9Z)-neoxanthin, rubixanthin, zeaxanthin |

| HPLC-DAD [132] | C: YMC (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; YMC Co., Kyoto, Japan); G; E: MeOH-MTBE-H2O 90:6:4 (A); MeOH-MTBE-H2O 25:71:4 (B); 0–12 min 100% A, 12–96 min 0% A; ν 1 mL/min | DAD: λ 450 nm | γ-Carotene, lycopene, rubixanthin |

| HPLC-DAD [133] | C: Bondclone C18 (300 × 3.9 mm, 10 µm; Phenomenex, Torrans, CA, USA); I; E: MeOH-MeCN-MeCl-cyclohexene 22:55:11.5:11.5; ν 0.8 mL/min | DAD: λ 440 nm | β-Carotene, lutein |

| HPLC-DAD [134] | C: Nucleodur C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany); I; E: H2O-Me2CO 13:87; ν 1 mL/min | DAD: λ 445 nm | Lutein, zeaxanthin |

| HPLC-DAD [135] | C: Inertsil ODS-3 C18 (250 × 4.6 mm; GL Sciences, Torrance, CA; USA); I; E: MeOH-THF-H2O 37:60:3; ν 1.4 mL/min | DAD: λ 474 nm | Astaxanthin, canthaxanthin, β-carotene |

| HPLC-DAD [136] | C: C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm); I; E: MeCN-MeOH 40:60; ν 1 mL/min | DAD: λ 446 nm | Lutein |

| HPLC-DAD-MS [85] | C: C30 YMC column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; YMC Co., Kyoto, Japan); G; E: MeOH-MTBE-H2O 81:15:4 (A), MeOH-MTBE-H2O 16:80.4:3.6 (B); 0–39 min 99–44% A, 39–45 min 44–0% A; ν 1.0 mL/min | DAD: 450 nm MS: APCI | 74 Compounds |

| Fatty Acids | |||

| GC-MS [105] | C: BPx-70 (60 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm; Trajan Scientific and Medical, Victoria, Australia) | MS: EI (70 eV) | 11 Acids |

| GC-MS [137] | C: DB-23 (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA) | MS: EI (70 eV) | 12 Acids |

| GC-MS [138] | C: HP-88 (100 m × 25 mm, 0.2 µm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA) | MS: EI (70 eV) | 7 Acids |

| GC-MS [139] | C: Supelco SP-2560 (100 m × 0.25 mm, 0.2 µm; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MI, USA) | MS: CI | 17 Acids |

| Phenolic Compounds | |||

| HPLC-UV [140] | C: SiliaChrom C-18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; SiliCycle, Quebec, Canada); G; E: 0.08% H3PO4 (A), MeOH (B); 0–1.5 min 35% B, 1.5–4 min 35–50% B, 4–12 min 55% B, 12–13 min 50–100% B, 13–20 min 100% B, 20–21 min 100–35% B, 21–30 min 35% B; ν 1 mL/min | UV: λ 370 nm | Quercetin |

| HPLC-UV [141] | C: Hypersyl C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); I; E: MeCN-2% CH3COOH in H2O 15:85; ν 1 mL/min | UV: λ 340 nm | Narcissin, rutin |

| HPLC-UV [142] | C: Phenomenex C18 (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA); I; E: MeCN-2% HCOOH 15:85; ν: 0.5 mL/min | UV: λ 254 nm | Chlorogenic, caffeic acids, rutin |

| HPLC-UV [143] | C: Zorbax SB-C18 (100 × 3 mm, 3.5 µm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA); G; E: 0.1% HCOOH in H2O (A), MeOH (B); 0–35 min 5–42% B; ν 1 mL/min; T 48 °C | UV: λ 330, 370 nm | Caffeic, chlorogenic, p-coumaric, ferulic acids, isoquercitrin, rutin, quercetin |

| HPLC-UV [96] | K: Schim-pack C-18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Shimadzu, Columbia, MA, USA); G; E: 0.1% HCOOH in H2O (A), 0.1% HCOOH in MeCN (B); 0–1 min 5% B, 1–12 min 5–100% B, 12–16 min 100% B, 16–18 min 100–5% B; ν 200 µL/min | UV: λ 280, 335 nm | Isoquercitrin, isorhamnetin, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, rutin, scopolin |

| HPLC-UV [133] | C: Bondclone C18 (300 × 3.9 mm, 10 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA); G; E: 15% CH3COOH in H2O (A), MeOH (B); 0–15 min 5% B; ν 1.5 mL/min | UV: λ 254 nm | Isoquercitrin, narcissin, quercetin, scopolin |

| HPLC-UV [90,114,144] | C: ProntoSIL-120-5-C18 AQ (75 × 2 mm, 5 µm; Knauer, Berlin, Germany); G; E: 0.2 M LiClO4 in 0.006 M HClO4 (A), MeCN (B); 0–7.5 min 11–18% B, 7.5–13.5 min 18% B, 13.5–15 min 18–20% B, 15–18 min 20–25% B, 18–24 min 25% B, 24–30 min 25–100% B; ν: 150 µL/min; T 35 °C | UV: λ 270 nm | 3-O-Caffeoylquinic, caffeic acids, thyphaneoside, isoquercitrin, rutin, quercetin-3-O-(6″-acetyl)-β-d-glycoside, 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic, 1,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic, 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acids, isorhamnetin-3-O-β-d-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-(6″-acetyl)-β-d-glycoside |

| HPLC-PDA [145] | C: X-Bridge C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA); I; E: MeCN-MeOH-H2O 30:2:68; ν: 0.5 mL/min | PDA: λ 254 nm | Rutin |

| HPLC-DAD [146] | C: Eclipse XDB-C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA); G; E: 0.1% H3PO4 in MeOH (A), 0.1% H3PO4 in iPrOH (B); 0–10 min 10–15% B, 10–20 min 15–20% B | DAD: λ 280, 330 nm | Caffeic, chlorogenic, vanilic, p-coumaric, t-2-hydroxycinnamic acids |

| HPLC-DAD [147] | C: ODS Hypersil C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); G; E: 0.33 M CH3COOH (A), MeOH (B); 0–80 min 8–70% B; ν 80 µL/min | DAD: λ 327, 356 nm | Quercetin, rutin |

| HPLC-DAD [148] | C: Phenomenex C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA); G; E: 0.5% CH3COOH (A), MeOH (B); 0–2 min 1–5% B, 2–10 min 5–20% B, 10–40 min 20–45% B, 40–55 min 70% B, 55–75 min 100% B; ν 0.6 mL/min | DAD: λ 327, 366 nm | Chlorogenic, caffeic, rutin, quercetin, kaempferol |

| HPLC-DAD [149] | C: Spherisorb S3 ODS-2 C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm); G; E: 0.1% HCOOH (A), MeCN (B); 0–5 min 15% B, 5–10 min 15–20% B, 10–20 min 20–25% B, 20–30 min 25–35% B, 30–40 min 35–50% B | DAD: λ 280, 370 nm | 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, quercetin-3-O-rhamnosylrutinoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, kaempferol-O-rhamnosylrutinoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-rhamnosylrutinoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohesperidoside, quercetin-3-O-(6″-acetyl)-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-(6″-acetyl)-glucoside |

| HPLC-DAD [150] | C: Phenomenex Kinetex Phenyl-hexyl (150 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA); G; E: 0.1% HCOOH (A), 0.1% HCOOH in MeCN (B); 0–5 min 10% B, 5–35 min 15–45 % B, 35–40 min 45–100 % B; ν 500 μL/min | DAD: λ 330 nm | Chlorogenic acid, thyphaneoside, manghaslin, rutin, calendoflavoside, narcissin |

| HPLC- UV-MS [151] | C: RP Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 1.8 µm; Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, CA, USA); G; E: 0.2% HCOOH in H2O (A), MeCN (B); 0–3 min 5–24% B, 3–6 min 24% B, 6–24 min 24–38% B, 24–30 min 38–99% B, 30–33 min 99% B, 33–34 min 99–5% B; ν 0.8 mL/min | UV: λ 356 nm MS: neg. | 3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-acetylglucoside, manghaslin, narcissin, rutin, thyphaneoside |

| HPLC- UV-MS [152] | C: Aquapore RP-300 (220 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA); I; E: iPrOH-THF-CH3COONH4 pH 4.5 10:5:85; ν 1.2 mL/min | UV: λ 360 nm MS: neg. | Thyphaneoside |

| HPLC- UV-MS [100,153] | C: LiChrosorb RP18 (10 × 4 mm, 5 µm; Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA); G; E: MeCN (A), phosphate buffer pH 3.0 (B); 0–10 min 12% B, 10–15 min 12–18% B, 15–30 min 18–45% B, 30–42 min 45–100% B, 42–50 min 100–12% B; ν 1.3 mL/min; T 26 °C | UV: λ 254, 330, 350 nm MS: neg. | 3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, isoquercitrin, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-acetylglucoside, manghaslin, narcissin, rutin, thyphaneoside |

| HPLC- UV-MS [131] | C: C18 Luna (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrans, CA, USA); G; E: H2O (A), MeCN (B), CH3COOH in 10% MeCN (C); 0–47 min 90%A-0%B-10%C→43%A-47%B-10%C, 0–47 min 0%A-90%B-10%C | UV: λ 254 nm; MS: neg. | Narcissin, thyphaneoside |

| HPLC- UV-MS [75] | C: Hypersil gold column (1000 × 20 mm, 1.9 µm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); G; MeCN (A), 0.1% HCOOH (B); 0–14 min 5% B, 14–16 min 5–40 % B, 16–23 min 40–100 % B, 23–33 min 100–5 % B; ν 0.2 mL/min; T 30 °C | UV: λ 280 nm; MS: neg. | 40 Compounds |

| UHPLC-DAD [154] | C: Acquity UPLC HSS T3 (150 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA); G; E: H2O (A), MeCN (B); 0.0–4.0 min 3–13% B, 4.0–5.0 min 13–17.5% B, 5.0–9.0 min 17.5% B, 9.0–12.5 min 17.5–24.5% B, 12.5–17.0 min 24.5–30.0% B, 17.0–25.0 min 30.0% B, 25.0 min 3.0% B, 25.0–30.0 min 3.0% B; ν 275 µL/min | UV: λ 330 nm | Chlorogenic acid, typhaneoside, narcissin |

a Assay: APCI-QTOF—atmospheric pressure chemical ionization quadrupole time-of-flight; DAD—diode array detector; FID—flame ionization detector; GC—gas chromatography; HPLC—high-performance liquid chromatography; MS—mass spectrometric detector; PDA—photodiode arrary detector; UHPLC—ultra high-pressure liquid chromatography; UV—ultraviolet. b Separation conditions: column (C); elution mode (I—isocratic, G—gradient); eluents (E; iPrOH—isopropanol; MeCN—acetonitrile; MTBE—methyl tert-butyl ester; THF—tetrahydrofuran); column temperature (T).

4.5. Phenolic Compounds

Evaluation of phenolic compounds in Calendula plants is an important task, as indicated by the known HPLC protocols found in the scientific literature. To separate target compounds, only RP C18 columns with varying lengths were used, such as 75 mm ProntoSIL-120-5-C18 [90,114,144]; 100 mm Phenomenex C18 [142], Zorbax SB-C18 [143], and LiChrosorb RP18 [100,153]; 150 mm Luna C18 [131], SiliaChrom C-18 [140], Eclipse XDB-C18 [146], Spherisorb S3 ODS-2 C18 [149], Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 [151], and Aquity UPLC HSS T3 [154]; 220 mm Aquapore RP-300 [152]; 250 mm Shim-pack C-18 [96], Hypersil C18 [141,147], X-Bridge C18 [145], and Phenomenex C18 [148]; 300 mm Bondclone C18 [133]; and 1000 mm Hypersil Gold [75]. The presence of various eluents requires the frequent use of formic acid [75,96,142,150,151], acetic acid [133,141,148], phosphoric acid [140,146] as the polar eluent and methanol [133,140] and acetonitrile [96,114,141,142] as the non-polar eluent. The addition of lithium perchlorate [90,114,144] and tetrahydrofuran [152] resulted in better resolution and improved peak shapes. Detection in the region at 254–280 nm and/or 330–370 nm corresponds to the maximum absorption of most phenolic compounds. The optimized LC conditions resulted in the separation of basic flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates of Calendula.

5. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives of Calendula Metabolites Research

Based on the results of previous studies, for the genus Calendula, a situation has been observed that is typical for industrial plant species that are widely used in human life. For such species, knowledge is skewed in favor of a single plant that is a commercial product, such as C. officinalis, which is the only species from the genus that is widely used. An incomparably smaller amount of information is available for C. arvensis, C. stellata, C. suffruticosa, and C. tripterocarpum, and seven other species (C. eckerleinii, C. karakalensis, C. lanzae, C. maroccana, C. meuselii, C. pachysperma, C. palaestina) are still unstudied. Of note, C. officinalis is an example of the use of only one part of the plant (flowers) to the detriment of the rest of the biomass (leaves, stems, roots), which has been understudied and is typically wasted. Table 5 presents a synopsis of known knowledge and clearly demonstrates the current situation regarding the Calendula genus.

Table 5.

Synopsis of known scientific information about metabolites of five Calendula species.

The actual situation in the field of studying Calendula chemodiversity indicates that essential oils of this genus are most often subjected to research. This occurs owing to the greater availability of instruments for this type of analysis, which is usually performed using the GC-MS technique, as well as the simplicity of sample preparation, which requires hydrodistillation (as the most common method of isolation). The same applies to the analysis of lipophilic extracts (hexane, dichloroethane, chloroform), which contain sterols, alkanes, aliphatic alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and fatty acids. That is why there is an abundance of information on non-polar compounds. Of note, the lipophilic components of Calendula are currently of no practical importance; thus, excessive attention to them is not justified, at least until further studies are performed.

Sesquiterpene glycosides, unlike the sesquiterpene components of essential oils, have proven antiviral activity against a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and rhinovirus (HRV type 1B) [47], antiprotozoal activity against Leishmania donovani [49], and anti-inflammatory activity [155]. However, the study of these valuable compounds is limited to only three species; in C. officinalis, only flowers have been studied; although, given the discovery of these compounds in the herb of C. arvensis, it would be worth paying attention to other parts of C. officinalis.

Researchers have made considerable progress in the study of triterpene alcohols, esters, and glycosides of Calendula. However, these studies refer primarily to C. officinalis from which 91 compounds have been isolated out of 109 known compounds. Compared to other compounds, for triterpenoid esters and glycosides, more in-depth pharmacological studies have been performed. Pharmacological studies demonstrated the anti-ulcer effect of calenduloside B (319) [156], antimutagenic activity of glycosides 291, 295, 296, 299, 300, 303, 309, 312, 318, 320 [157], the anti-inflammatory activity of faradiol (197), lupeol (189) [6], and other triterpene alcohols [3] and some esters [125], hypoglycemic and gastroprotective potential of glucoside A (303), B (296), C (300), D (295), and F (291) [9], as well as their antibacterial, antiparasitic [158], and other activities. Owing to the clear potential of using triterpenoids as biologically active agents, it is necessary to expand the search for new compounds and new sources within the Calendula genus.

Phenolic compounds of the Calendula genus have been extensively studied; however, most of the scientific information related to C. officinalis does not allow global conclusions about the features of the phenolic distribution within the genus. The question of domination of only two flavonol aglycones (quercetin and isorhamnetin) in Calendula plants remains interesting and unexplored.

The studies of carotenoids, anthocyanins, and polysaccharides are limited to a single object, C. officinalis flowers, and these studies require more attention because of the availability and wide spectrum of bioactivity of these phytochemicals. Moreover, a detailed study of the fine stricture of polysaccharides of C. officinalis flowers is needed owing to the lack of information.

Because C. officinalis is an industrial plant, it is necessary to expand research on non-floral parts of the plant, such as leaves, stems, roots, and seeds. The volume of production of these parts of the plant must be gigantic, but there are currently no examples of their rational practical application. In terms of marigold pharmaceutic production, the waste from the industrial processing of C. officinalis flowers is not used as a resource for obtaining valuable products. Moreover, there are few examples of recycling waste from the pharmaceutical processing of plants. Currently, this wasteful approach can be regarded as irrational and requires more attention and reasonable proposals for processing plant waste.

In general, after almost a century of studying the genus Calendula, despite its widespread use, it is still the subject of numerous studies. Scientists are trying to expand the horizons of knowledge about its metabolites, application, and analysis because there are still many areas that need to be clarified. Taking into account the identified trends in the study of Calendula, we will still require scientific progress in the field of genus chemistry for a long period of time.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules27238626/s1, Table S1: Distribution of Calendula publications between research areas; Table S2: Top 10 cited articles aimed to Calendula research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition, D.N.O. and N.I.K.; supervision, project administration, D.N.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, grant number 121030100227-7.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Plants of the World Online. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30120329-2 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Pommier, P.; Gomez, F.; Sunyach, M.P.; D’Hombres, A.; Carrie, C.; Montbarbon, X. Phase III randomized trial of Calendula officinalis compared with trolamine for the prevention of acute dermatitis during irradiation for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihisa, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Oinuma, H.; Kasahara, Y.; Yamanouchi, S.; Takido, M.; Kumaki, K.; Tamura, T. Triterpene alcohols from the flowers of Compositae and their anti-inflammatory effects. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparzadeh, N.; D’Amico, M.L.; Khavari-Nejad, R.-A.; Izzo, R.; Navari-Izzo, F. Antioxidative responses of Calendula officinalis under salinity conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2004, 42, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, M.; Heinzmann, B.; Hamburger, M.; Laufer, S.; Merfort, I. Determination of the wound healing effect of Calendula extracts using the scratch assay with 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loggia, R.; Tubaro, A.; Sosa, S.; Becker, H.; Saar, S.; Isaac, O. The role of triterpenoids in the topical anti-Inflammatory activity of Calendula officinalis flowers. Planta Med. 1994, 60, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukiya, M.; Akihisa, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Tokuda, H.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, Y. Anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor-promoting, and cytotoxic activities of constituents of marigold (Calendula officinalis) flowers. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1692–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, H.; Proksch, A.; Riess-Maurer, I.; Vollmar, A.; Odenthal, S.; Stuppner, H.; Jurcic, K.; Le Turdu, M.; Fang, J.N. Immunstimulierend wirkende Polysaccharide (Heteroglykane) aus hoheren Pflanzen. Arzneim. Forsch. 1985, 35, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Murakami, T.; Kishi, A.; Kageura, T.; Matsuda, H. Medicinal flowers. III. Marigold. (1): Hypoglycemic, gastric emptying inhibitory, and gastroprotective principles and new oleanane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, calendasaponins A, B, C, and D, from Egyptian Calendula officinalis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćetković, G.S.; Djilas, S.M.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.M.; Tumbas, V.T. Antioxidant properties of marigold extracts. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Medina, E.; Garcia-Lora, A.; Paco, L.; Algarra, I.; Collado, A.; Garrido, F. A new extract of the plant Calendula officinalis produces a dual in vitro effect: Cytotoxic anti-tumor activity and lymphocyte activation. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Bent, S.; Foppa, I.; Haskmi, S.; Kroll, D.; Mele, M.; Szapary, P.; Ulbricht, C.; Vora, M.; Yong, S. Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2006, 6, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M.J. Calendula officinalis and wound healing: A systematic review. Wounds 2008, 20, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muley, B.; Khadabadi, S.; Banarase, N. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Calendula officinalis Linn (Asteraceae): A review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2009, 8, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Chattopadhayay, P. Calendula officinalis: An important herb with valuable therapeutic dimensions—An overview. J. Global Pharma Technol. 2010, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, D.; Rani, A.; Sharma, A. A review on phytochemistry and ethnopharmacological aspects of genus Calendula. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2013, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodiyan, J.; Amber, K.T. A review of the use of topical Calendula in the prevention and treatment of radiotherapy-induced skin reactions. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghédira, K.; Goetz, P. Calendula officinalis L. (Asteraceae): Souci. Phytothérapie 2016, 14, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruceriu, D.; Balacescu, O.; Rakosy, E. Calendula officinalis: Potential roles in cancer treatment and palliative care. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, B.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B. Edible flowers with the common name “marigold”: Their therapeutic values and processing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 89, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givol, O.; Kornhaber, R.; Visentin, D.; Cleary, M.; Haik, J.; Harats, M. A systematic review of Calendula officinalis extract for wound healing. Wound Repair Regener. 2019, 27, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, S.I.; Taha, M.M.E.; Taha, S.M.E.; Alsayegh, A.A. Fifty-year of global research in Calendula officinalis L. (1971−2021): A bibliometric study. Clin. Complement. Med. Pharmacol. 2022, 2, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeli, D. Calendula officinalis L. In Novel Drug Targets with Traditional Herbal Medicines; Gürağaç, D.F.T., Ilhan, M., Belwal, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, F.A. Über die Bestandteile der Blüten der Ringelblume; Dissert: Erlangen, Germany, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, A. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der in dem Farbstoff der Blüten der Ringelblume (Calendula officinalis) Vorkommenden Cholesterinester; Dissert: Erlangen, Germany, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Hilger, A. Zur chemischen Kenntnis der Blumenfarbstoffe. Botan. Centr. 1894, 57, 375. [Google Scholar]

- Zechmeister, L.; von Cholnoky, L.V. Über den Farbstoff der Ringelblume (Calendula officinalis). Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis des Blüten-Lycopins. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 1932, 208, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeon, J. Uber die Inhaltsstoffe der Ringelblume, Calendula officinalis L. Pharmazie 1951, 6, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Chattopadhyay, P. Assessment of in vitro sun protection factor of Calendula officinalis L. (Asteraceae) essential oil formulation. J. Young Pharm. 2012, 4, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh, O.O.; Sadimenko, A.A.; Afolayan, A.J. The effect of age on the yield and composition of the essential oils of Calendula officinalis. J. Appl. Sci. 2007, 7, 3806–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh, O.O.; Sadimenko, A.A.; Asekun, O.T.; Afolayan, A.J. The effect of drying on the chemical components of essential oils of Calendula officinalis. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 1500–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Gazim, Z.C.; Rezende, C.M.; Fraga, S.R.; Filho, B.P.D.; Nakamura, C.V.; Cortez, D.A.G. Analysis of the essential oils from Calendula officinalis growing in Brazil using three different extraction processes. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Farm. 2008, 44, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbes, R.; Dib, M.E.A.; Djabou, N.; Ilias, F.; Tabti, B.; Costa, J.; Muselli, A. Chemical variability, antioxidant and antifungal activities of essential oils and hydrosol extract of Calendula arvensis L. from Western Algeria. Chem. Biodiv. 2017, 14, e1600482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, J.; Barboni, T.; Desjobert, J.-M.; Djabou, N.; Muselli, A.; Costa, J. Chemical composition, intraspecies variation and seasonal variation in essential oils of Calendula arvensis L. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.K.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Biology of Calendula officinalis Linn.: Focus on pharmacology, biological activities and agronomic practices. Med. Arom. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 6, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaškonienė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Jalinskaitė, M.; Maruška, A. Chemical composition and chemometric analysis of variation in essential oils of Calendula officinalis L. during vegetation stages. Chromatographia 2011, 73, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.K. Effect of potassium uptake on the composition of essential oil content in Calendula officinalis L. flowers. Emirates J. Food Agricult. 2013, 25, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, G.; Yayli, B.; Arslan, T.; Yasar, A.; Karaoglu, S.A.; Yayli, N. Comparative essential oil analysis of Calendula arvensis L. extracted by hydrodistillation and microwave distillation and antimicrobial activities. Asian J. Chem. 2012, 24, 1955–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, L.; Lepojevic, Z.; Sovilj, V.; Adamovic, D.; Tesevic, V. An investigation of CO2 extraction of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2007, 72, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, G.; Zengin, G.; Ceylan, R.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Jugreet, S.; Mollica, A.; Stefanucci, A. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oils from Calendula officinalis L. flowers and leaves. Flavour Fragr. J. 2021, 36, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino, M.V.; Seca, A.M.L.; Silveira, P.; Silva, A.M.S.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry profile of four Calendula L. taxa: A comparative analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 104, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohse, S.; Marques, M.B.; Silveira, P.C.; Válega, M.S.G.A.; Granato, D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Inter-individual versus inter-population variability of Calendula suffruticosa subsp. algarbiensis hexane extracts. Chem. Biodiv. 2021, 18, e2100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizza, C.; De Tommasi, N. Plants metabolites. A new sesquiterpene glycoside from Calendula arvensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1987, 50, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizza, C.; De Tommasi, N. Sesquiterpene glycosides based on the alloaromadendrane skeleton from Calendula arvensis. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2205–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, M.; Ciocarlan, A.; Colombo, E.; Guerriero, A.; Pizza, C.; Sangiovanni, E.; Dell’Agli, M. Structure and cytotoxic activity of sesquiterpene glycoside esters from Calendula officinalis L.: Studies on the conformation of viridiflorol. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakupovic, J.; Grenz, M.; Bohlmann, F.; Rustaiyan, A.; Koussari, S. Sesquiterpene glycosides from Calendula persica. Planta Med. 1988, 54, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tommasi, N.; Pizza, C.; Conti, C.; Orsi, N.; Stein, M.L. Structure and in vitro antiviral activity of sesquiterpene glycosides from Calendula arvensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1990, 53, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Jakupovic, J.; Mabry, T.J. Sesquiterpene glycosides from Calendula arvensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 1821–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.A.; Ashour, A.A.; Qiu, L. New sesquiterpene glycoside ester with antiprotozoal activity from the flowers of Calendula officinalis L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 5250–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marukami, T.; Kishi, A.; Yoshikawa, M. Medicinal flowers. IV. Marigold. (2): Structures of new ionone and sesquiterpene glycosides from Egyptian Calendula officinalis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, G.; Kasprzyk, Z. Free sterols, steryl esters, glucosides, acylated glucosides and water-soluble complexes in Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry 1975, 14, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintea, A.; Dulf, F.V.; Bele, C.; Andrei, S. Fatty acid distribution in the lipid fraction of Calendula officinalis L. seed oil. Chem. Listy 2008, 102, 749–750. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski, Z.; Bocheńska-Hryniewicz, M.; Kucharczak, B.; Kasprzyk, Z. Sterol and triterpene alcohol esters from Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niżyński, B.; Alsoufi, A.S.M.; Pączkowski, C.; Długosz, M.; Szakiel, A. The content of free and esterified triterpenoids of the native marigold (Calendula officinalis) plant and its modifications in in vitro cultures. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, H.; Ansari, S.H.; Ali, M.; Naved, T. A new δ-lactone containing triterpene from the flowers of Calendula officinalis. Pharm. Biol. 2004, 42, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaus, C.; Sievers-Engler, A.; Murillo, R.; D’Ambrosio, M.; Lämmerhofer, M.; Merfort, I. Mastering analytical challenges for the characterization of pentacyclic triterpene mono- and diesters of Calendula officinalis flowers by non-aqueous C30 HPLC and hyphenation with APCI-QTOF-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 118, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzyk, Z.; Pyrek, J. Triterpenic alcohols of Calendula officinalis L. flowers. Phytochemistry 1968, 7, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukirch, H.; D’Ambrosio, M.; Via, J.D.; Guerriero, A. Simultaneous quantitative determination of eight triterpenoid monoesters from flowers of 10 varieties of Calendula officinalis L. and characterisation of a new triterpenoid monoester. Phytochem. Anal. 2004, 15, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiłkomirski, B. Pentacyclic triterpene triols from Calendula officinalis flowers. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 3066–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, M.; Adler, S.; Baumann, D.; Förg, A.; Weinreich, B. Preparative purification of the major anti-inflammatory triterpenoid esters from Marigold (Calendula officinalis). Fitoterapia 2003, 74, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, G.; Wójciak-Kosior, M.; Paduch, R. The influence of Calendulae officinalis flos extracts on cell cultures, and the chromatographic analysis of extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 38, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwowski, J.; Dziewanowska, K.; Kasprzyk, Z. Ursadiol: A new triterpene diol from Calendula officinalis flowers. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, Z.; Wiłkomirski, B. Structure of a new triterpene triol from Calendula officinalis flowers. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 2299–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk, Z.; Wojciechowski, Z. Incorporation of 14C-acetate into triterpenoids in Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry 1969, 8, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naved, T.; Ansari, S.H.; Mukhtar, H.M.; Ali, M. New triterpenic esters of oleanene-series from the flowers of Calendula officinalis L. Ind. J. Chem. B 2005, 44, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, M.; Wiktorowska, E.; Wiśniewska, A.; Pączkowski, C. Production of oleanolic acid glucosides by hairy root established cultures of Calendula officinalis L. Acta Biochim. Polon. 2013, 60, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzyk, Z.; Wojciechowski, Z. The structure of triterpenic glycosides from the flowers of Calendula officinalis L. Phytochemistry 1967, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakiel, A.; Ruszkowski, D.; Janiszowska, W. Saponins in Calendula officinalis L.—Structure, biosynthesis, transport and biological activity. Phytochem. Rev. 2005, 4, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Zinkevich, É.P.; Kogan, L.M. Oleanolic acid 3-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1973, 9, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Ollivier, E.; Balansard, G.; Faure, R.; Babadjamian, A. Revised structures of triterpenoid saponins from the flowers of Calendula officinalis. J. Nat. Prod. 1989, 52, 1156–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, Z.; Jelonkiewicz-Konador, A.; Tomaszewski, M.; Jankowski, J.; Kasprzyk, Z. The structure of glycosides of oleanolic acid isolated from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehbili, M.; Alabdul Magid, A.; Kabouche, A.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L.; Abedini, A.; Morjani, H.; Sarazin, T.; Gangloff, S.C.; Kabouche, Z. Oleanane-type triterpene saponins from Calendula stellata. Phytochemistry 2017, 144, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizza, C.; Zhong-Liang, Z.; De Tommasi, N. Plant metabolites. Triterpenoid saponins from Calendula arvensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1987, 50, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Sviridov, A.F.; Zinkevich, É.P.; Kogan, L.M. Structures of calendulosides G and H from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1974, 10, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustino, M.V.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Salgueiro, L.; Silveira, P.; Silva, A.M.S. Calendula L. species polyphenolic profile and in vitro antifungal activity. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 45, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Zinkevich, É.P.; Kogan, L.M. The structure of calenduloside F from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1973, 9, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızıbekmez, H.; Bassarello, C.; Piacente, S.; Pizza, C.; Çalış, İ. Triterpene saponins from Calendula arvensis. Z. Naturforsch. B 2006, 61, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemli, R.; Babadjamian, A.; Faure, R.; Boukef, K.; Balansard, G.; Vidal, E. Arvensoside A and B, triterpenoid saponins from Calendula arvensis. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1785–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Zinkevich, É.P.; Libizov, N.I.; Ban’kovskii, A.I. Calenduloside A from Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1969, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Sviridov, A.F.; Zinkevich, É.P.; Kogan, L.M. The structure of calendulosides C and D from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1975, 11, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecherko, L.P.; Kabanov, V.S.; Zinkevich, É.P. The structure of calenduloside B from the roots of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1971, 7, 516–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tommasi, N.; Conti, C.; Stein, M.; Pizza, C. Structure and in vitro antiviral activity of triterpenoid saponins from Calendula arvensis. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakó, E.; Deli, J.; Tóth, G. HPLC study on the carotenoid composition of Calendula products. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2002, 53, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, S.; Sumitomo, K.; Yagi, M.; Nakayama, M.; Ohmiya, A. Three routes to orange petal color via carotenoid components in 9 Compositae species. J. Jap. Soc. Horticult. Sci. 2007, 76, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Mariutti, L.R.B. Marigold carotenoids: Much more than lutein esters. Food Res. Int. 2018, 119, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintea, A.; Bele, C.; Andrei, S.; Socaciu, C. HPLC analysis of carotenoids in four varieties of Calendula officinalis L. flowers. Acta Biol. Szeg. 2003, 47, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Swiatek, L.; Góra, J. Phenolic acids in the inflorescences of Arnica montana L. and Calendula officinalis L. Herba Polon. 1978, 24, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Góra, J.; Kalemba, D.; Kurowska, A.; Swiatek, L. Chemical substances from inflorescences of Arnica montana L. and Calendula officinalis L. soluble in isopropyl myristate and propylene glycol. Acta Hortic. 1980, 96, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I. New isorhamnetin glycosides and other phenolic compounds from Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 49, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I. Componential profile and amylase inhibiting activity of phenolic compounds from Calendula officinalis L. leaves. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 654193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I. 1,5-Di-O-isoferuloylquinic acid and other phenolic compounds from pollen of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rifai, A. Identification and evaluation of in-vitro antioxidant phenolic compounds from the Calendula tripterocarpa Rupr. South Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 116, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, M.; Gravina, C.; Piccolella, S.; Pecoraro, M.T.; Formato, M.; Stinca, A.; Pacifico, S.; Esposito, A. Calendula arvensis (Vaill.) L.: A systematic plant analysis of the polar extracts from its organs by UHPLC-HRMS. Foods 2022, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derkach, A.I.; Komissarenko, N.F.; Chernobai, V.T. Coumarins of the inflorescences of Calendula officinalis and Helichrysum arenarium. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1986, 22, 722–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I.; Vennos, C. A new esculetin glycoside from Calendula officinalis (Asteraceae) and its bioactivity. Farmacia 2017, 65, 698–702. [Google Scholar]

- Rigane, G.; Younes, B.S.; Ghazghazi, H.; Salem, R.B. Investigation into the biological activities and chemical composition of Calendula officinalis L. growing in Tunisia. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 3001–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Komissarenko, N.F.; Chernobai, V.T.; Derkach, A.I. Flavonoids of inflorescences of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1988, 24, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Ollivier, E.; Elias, R.; Faure, F.; Babadjamian, A.; Crespin, F.; Balansard, G.; Boudon, G. Flavonol glycosides from Calendula officinalis flowers. Planta Med. 1989, 55, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I. Calendosides I–IV, new quercetin and isorhamnetin rhamnoglucosides from Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilia, A.R.; Salvini, D.; Mazzi, G.; Vincieri, F.F. Characterization of calendula flower, milk-thistle fruit, and passion flower tinctures by HPLC-DAD and HPLC-MS. Chromatographia 2000, 53, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mašterová, I.; Grančaiová, Z.; Uhrínová, S.; Suchý, V.; Ubik, K.; Nagy, M. Flavonoids in flowers of Calendula officinalis L. Chem. Papers 1991, 45, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Samra, R.M.; Maatooq, G.T.; Zaki, A.A. A new antiprotozoal compound from Calendula officinalis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 36, 5747–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul’chenko, N.T.; Glushenkova, A.I.; Mukhamedova, K.S. Lipids of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1998, 34, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khidoyatova, S.K.; Ul’chenko, N.T.; Gusakova, S.D. Hydroxyacids from seeds and lipids of Calendula officinalis flowers. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2016, 52, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, F.V.; Pamfil, D.; Baciu, A.D.; Pintea, A. Fatty acid composition of lipids in pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) seed genotypes. Chem. Centr. J. 2013, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiszowska, W.; Jasiňska, R. Intracellular localization of labelling of tocopherols with [U-14C]-tyrosine in Calendula officinalis leaves. Acta Biochim. Polon. 1982, 29, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janiszowska, W.; Korczak, G. The intracellular distribution of tocopherols in Calendula officinalis leaves. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 1391–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasova, R.L.; Aslanov, S.M.; Mamedova, M.É. Amino acids of Calendula officinalis. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1994, 30, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willuhn, G.; Westhaus, R.-G. Loliolide (calendin) from Calendula officinalis. Planta Med. 1987, 53, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshihiro, A.; Hirotoshi, O.; Ken, Y.; Yoshimasa, K.; Yumiko, K.; Sei-Ichi, T.; Sakae, Y.; Michiob, T.; Kunio, K.; Toshitake, T. Helianol [3,4-seco-19(10→9)abeo-8α,9β,10α-eupha-2.24-dien-3-ol]. a novel triterpene alcohol from the tabular flowers of Helianthus annuns L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1255–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Balsevich, J.J.; Bishop, G.G.; Deibert, L.K. Use of digitoxin and digoxin as internal standards in HPLC analysis of triterpene saponin-containing extracts. Phytochem. Anal. 2009, 20, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakiel, A.; Janiszowska, W. Competition between oleanolic acid glucosides in their transport to isolated vacuoles from Calendula officinalis leaf protoplasts. Acta Biochim. Polon. 1992, 39, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fadda, A.; Palma, A.; Azara, E.; D’Aquino, S. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on overall appearance and nutraceutical quality of pot marigold held at 5 °C. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I.; Chirikova, N.K.; Akobirshoeva, A.; Zilfikarov, I.N.; Vennos, C. Isorhamnetin and quercetin derivatives as anti-acetylcholinesterase principles of marigold (Calendula officinalis) flowers and preparations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Kiprotich, J.; Kuhnert, N. Determination of the hydroxycinnamate profile of 12 members of the Asteraceae family. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, H. Über das Vorkommen von Isorhamnetinglykosiden in den Blüten von Calendula officinalis L. Arch. Pharm. 1962, 295, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, H. Untersuchungen über die Isorhamnetinglykoside aus den Blüten von Calendula officinalis L. Arch. Pharm. 1962, 295, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, H.; Proksch, A.; Riess-Maurer, I. Immunstimulierend wirkende Polysaccharide (Heteroglykane) aus hoheren Pflanzen: Vorlaufige Mitteilung. Arzneim. Forsch. 1984, 34, 659–661. [Google Scholar]

- Varljen, J.; Lipták, A.; Wagner, H. Structural analysis of a rhamnoarabinogalactan and arabinogalactans with immuno-stimulating activity from Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 2379–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzh, A.P.; Gur’ev, A.M.; Belousov, M.V.; Yusubov, M.S.; Belyanin, M.L. Composition of water-soluble polysaccharides from Calendula officinalis L. flowers. Pharm. Chem. J. 2012, 46, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Panchev, I.; Kovacheva, D.; Vasileva, I. Physico-chemical characterization of water-soluble pectic extracts from Rosa damascena, Calendula officinalis and Matricaria chamomilla wastes. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Ognyanov, M.; Vasileva, I. Pectic polysaccharides extracted from pot marigold (Calendula officinalis) industrial waste. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 101, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, M.; Alsoufi, A.S.M.; Szakiel, A.; Długosz, M. Effect of ethylene and abscisic acid on steroid and triterpenoid synthesis in Calendula officinalis hairy roots and saponin release to the culture medium. Plants 2022, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Pączkowski, C.; Szakiel, A. Modulation of steroid and triterpenoid metabolism in Calendula officinalis plants and hairy root cultures exposed to cadmium stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitterl-Eglseer, K.; Sosa, S.; Jurenitsch, J.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M.; Della Loggia, R.; Tubaro, A.; Bertoldi, M.; Franz, C. Anti-oedematous activities of the main triterpendiol esters of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1997, 57, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznicek, G.; Zitterl-Eglseer, K. Quantitative determination of the faradiol esters in marigold flowers and extracts. Sci. Pharm. 2003, 71, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitterl-Eglseer, K.; Reznicek, G.; Jurenitsch, J.; Novak, J.; Zitterl, W.; Franz, C. Morphogenetic variability of faradiol monoesters in marigold Calendula officinalis L. Phytochem. Anal. 2001, 12, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, D.; Adler, S.; Grüner, S.; Otto, F.; Weinreich, B.; Hamburger, M. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of marigold at high pressures: Comparison of analytical and pilot-scale extraction. Phytochem. Anal. 2004, 15, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva-Bermejo, D.; Vázquez, E.; Villalva, M.; Santoyo, S.; Fornari, T.; Reglero, G.; Rodriguez García-Risco, M. Simultaneous supercritical fluid extraction of heather (Calluna vulgaris L.) and Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) and anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. Studies of selected plant raw materials as alternative sources of triterpenes of oleanolic and ursolic acid types. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budan, A.; Bellenot, D.; Freuze, I.; Gillmann, L.; Chicoteau, P.; Richomme, P.; Guilet, D. Potential of extracts from Saponaria officinalis and Calendula officinalis to modulate in vitro rumen fermentation with respect to their content in saponins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, S.; Maoka, T.; Sumitomo, K.; Ohmiya, A. Analysis of carotenoid composition in petals of calendula (Calendula officinalis L.). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 2122–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccaglia, R.; Marotti, M.; Chiavari, G.; Gandini, N. Effects of harvesting date and climate on the flavonoid and carotenoid contents of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.). Flavour Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzaru, I.; Untea, A.E.; Van, I. Determination of bioactive compounds with benefic potential on health in several medicinal plants. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 20, 10773–10783. [Google Scholar]

- Jorjani, M.; Sharif, R.M.; Mirhashemi, R.A.; Ako, H.; Tan Shau Hwai, A. Pigmentation and growth performance in the blue gourami, Trichogaster trichopterus, fed marigold, Calendula officinalis, powder, a natural carotenoid source. JWAS 2019, 50, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.M.A.S.; Michielin, E.M.Z.; Danielski, L.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Experimental data and modeling the supercritical fluid extraction of marigold (Calendula officinalis) oleoresin. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2005, 34, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Reed, D.W.; Hong, H.; MacKenzie, S.L.; Covello, P.S. Identification and analysis of a gene from Calendula officinalis encoding a fatty acid conjugase. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Barut, M.; Tansi, L.S.; Bicen, G.; Karaman, S. Deciphering the quality and yield of heteromorphic seeds of marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) under high temperatures in the Eastern Mediterranean region. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, R.; Byrdwell, W. GC analysis of seven seed oils containing conjugated fatty acids. Separations 2021, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.J.A.; Morgan, M.J.E.; Trujillo, G.M. Validation of an HPLC method for quantification of total quercetin in Calendula officinalis extracts. Rev. Cubana Farm. 2015, 49, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, Y.M.; Vicentini, F.T.M.C.; Catini, C.D.; Fonseca, M.J.V. Determination of rutin and narcissin in marigold extract and topical formulations by liquid chromatography: Applicability in skin penetration studies. Quím. Nova 2010, 33, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loescher, C.M.; Morton, D.W.; Razic, S.; Agatonovic-Kustrin, S. High performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of Calendula officinalis—Advantages and limitations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 98, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniga, I.; Toiu, A.; Hanganu, D.; Vlase, L.; Duda, M.; Benedec, D. Influence of fertilizer treatment on the chemical composition of some Calendula officinalis varieties cultivated in Romania. Farmacia 2018, 66, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]