Abstract

Synthetic pesticides are widely used to protect crops from pathogens and pests, especially for fruits and vegetables, and this may lead to the presence of residues on fresh produce. Improving the sustainability of agriculture and, at the same time, reducing the adverse effects of synthetic pesticides on human health requires effective alternatives that improve the productivity while maintaining the food quality and safety. Moreover, retailers increasingly request fresh produce with the amounts of pesticides largely below the official maximum residue levels. Basic substances are relatively novel compounds that can be used in plant protection without neurotoxic or immune-toxic effects and are still poorly known by phytosanitary consultants (plant doctors), researchers, growers, consumers, and decision makers. The focus of this review is to provide updated information about 24 basic substances currently approved in the EU and to summarize in a single document their properties and instructions for users. Most of these substances have a fungicidal activity (calcium hydroxide, chitosan, chitosan hydrochloride, Equisetum arvense L., hydrogen peroxide, lecithins, cow milk, mustard seed powder, Salix spp., sunflower oil, sodium chloride, sodium hydrogen carbonate, Urtica spp., vinegar, and whey). Considering the increasing requests from consumers of fruits and vegetables for high quality with no or a reduced amount of pesticide residues, basic substances can complement and, at times, replace the application of synthetic pesticides with benefits for users and for consumers. Large-scale trials are important to design the best dosage and strategies for the application of basic substances against pathogens and pests in different growing environments and contexts.

1. Introduction

The world population continues to grow and will reach 9.7 billion by 2050 [1]. For this, increasing food production is the primary objective of all countries. According to the latest estimates of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [2], up to 40% of food crops worldwide are lost every year due to pests and plant diseases. Crop losses caused by plant disease alone cost the global economy $220 billion annually [3]. Crop protection is essential to reduce yield losses, improve food quality, and increase grower profitability. The application of plant protection products (PPPs) is the main way to protect crops against pathogens, pests, and weeds [4]. However, human, animal, and environmental risks associated with the use of chemical PPPs are a growing concern. All these concerns have encouraged the onset of research to develop alternative approaches to control plant diseases [5]. Reducing the use of pesticides being a major challenge in developed countries, European Union Member States are required to implement National Action Plans that set quantitative objectives, timetables, and indicators related to reducing the impact of pesticide use (Directive 2009/128/CE) [6,7]. The use of basic substances is approved in the European Union under Article 23 of EC Regulation No 1107/2009 and which are listed in Part C of the Annex of the Regulation (EC) No 540/2011 [8]. In the EU, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) has been mandatory since January 2014, and among the rules of the IPM is the reduction of the application of synthetic pesticides whenever possible [9]. For sustainable and qualitative food production, respectful of the need to produce in sufficient quantities, biocontrol has grown tremendously through the last few years [10]. The PPP EU Regulation (EC) 1107/2009 was established to ensure a level of protection of humans, animals, and the environment and, at the same time, to unify for the entire EU the rules on the placing on the market of plant protection products [11,12]. Basic substances are sources of interest for research as alternative to synthetic pesticides, since they are used in human medicine or as a food ingredient, so they have no residue concerns and then no maximum residue limit (MRL) and, usually, no preharvest interval [13,14]. The lack of MRL contributes to a better prevention of contamination in plant protection, a better control of the residues and a reduction of analytical problems, of decommissioning, and of market withdrawal [14]. Another benefit of basic substances, and perhaps the most important, is their very low ecologic impact. Basic substances are products that are used as ‘foodstuffs’, as defined in Article 2 of Regulation (EC) 178/2002 [15] cosmetic, and does not have an inherent capacity to cause endocrine-disrupting, neurotoxic or immunotoxic effects, but they are also plant protection means and not placed on the market as a plant protection product. Article 28 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 set the absence of marketing authorizations and usages allowance for basic substances. Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 introduced the new category of ‘basic substances’, which are defined by recital 18 as ‘certain substances which are not predominantly used as plant protection products may be of value for plant protection, but the economic interest of applying for approval may be limited. Therefore, specific provisions should ensure that such substances, as far as their risks are acceptable, may also be approved for plant protection use’. The properties of basic substances are described in Article 23 of the EU Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 [11]. In 2021, the Euphresco project ‘BasicS’ contributed to demonstrate the effectiveness toward pests and pathogens of basic substances, with potential benefits for the farmers, the consumer, and the environment [16,17]. The basic substances have a positive impact on crop health when applied preventively. Certain basic substances, such as chitosan, stimulate the defense system of crops against several classes of pathogens, including fungi, viruses, bacteria, and phytoplasma [18]. According to the EU pesticides database, 24 basic substances were approved for use, 7 were withdrawn, 18 applications were not approved and 8 are still pending [19,20]. This review includes currently approved basic substances that have a protective potential and are a valuable addition to the range of measures and protection methods intended for use. Detailed information about basic substances and updates on new available compounds can be found at the page https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/active-substances (accessed on 23 May 2022). The standard-folder for approval of a basic substance, called ‘Basic Substance Application Template (BSAT)’, is based on the structure of the European Union evaluation report of an active substance that can be used for plant protection purposes. BSAT refers to all areas of risk assessment in the regulation of phytopharmaceutical product uses and shall be considered as a structured model to build a file collating all available information and enabling to demonstrate that the evaluated substance meets the eligibility criteria of a basic substance (SANCO 10,363 rev.10, 2021). Therefore, nowadays, a full deposit under International Uniform ChemicaL Information Database (IUCLID) software is mandatory since March 2021. Basic substances are submitted individually (Annex I inclusion dossier) at the first stage; then, later, an automatic inclusion was adopted for food/foodstuff basic substance from plant or animal origin [21,22]. Recently, an automatic consideration procedure (without any Annex I inclusion dossier) by Expert Group for Technical advice on Organic Production (EGTOP)/Directorate-General for the Agriculture and Rural Development (DGAgri) of positive ongoing basic substance approval (from Directorate-General Health and Food Safety—DGSanté to DGAgri) to generate an automatic EGTOP/DGAgri outcome for inclusion (or not). This provision bypasses the traditional route of substances in organic production in plant protection through dossiers submitted to Member States, but so far, no basic substance has been rejected by the Regulatory Committee of Organic Production (RCOP), and with the current procedure, are no longer studied than substances of mineral origin (or non-foods).

This review aimed to highlight the properties of approved basic substances, summarize, and provide this information for phytosanitary consultants, scientists, growers, stakeholders, companies, and consumers.

2. Results

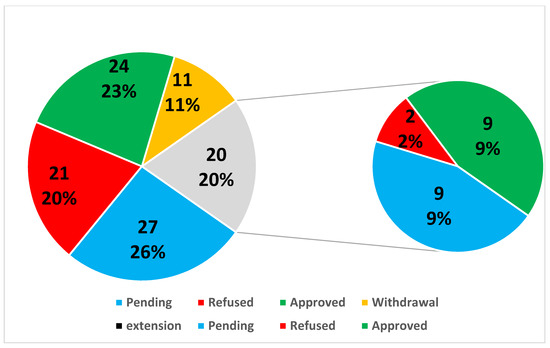

Out of the 86 basic substance application submitted to the European Commission until now, less than one-third have been approved (24) (Table 1 and Table 2), 19 have been refused, 6 have been withdrawn during their assessment (Table 3), 8 are currently being processed by the EC (Table 4 and Figure 1), and 2 already successfully submitted via IUCLID software (Ginger extract and Capsicum frutescens).

Table 1.

Application of the basic substances approved.

Table 2.

Typical uses of the basic substances.

Table 3.

Basic substance applications retired during the evaluation process.

Table 4.

Basic substance applications refused (non-approval).

Figure 1.

Total of the basic substance applications (BSA) and extensions presented by the results (%).

Currently, 24 basic substances are approved, of which 21 are also approved in organic production; for example, talc was validated in 2021 following EGTOP PPP VII and is being currently voted on at RCOP [23] and clayed charcoal was submitted. Recently, voted chitosan does not seem to be acceptable directly in organic production as the basic substance from its microorganism’s origin, although in the context of food quality. Basic substances are approved by EU Regulations, so the application month, where reported in Table 1, is related to the Northern Hemisphere.

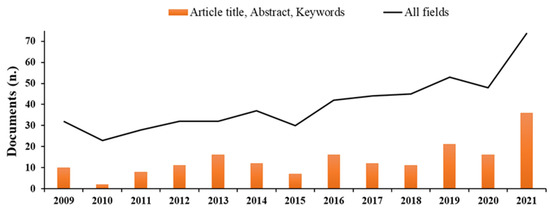

The scientific literature dealing with basic substances is relatively limited but increasing in recent years (Figure 2), and there is poor information about the effectiveness in field trials of basic substances toward pests and pathogens.

Figure 2.

Number of documents available on Scopus through searches with keywords ‘basic substances’ in ‘Article title, Abstract, and Keywords’ (histograms) or in ‘All fields’ (linear) published over the last 10 years (Source: Scopus, https://www.scopus.com, accessed on 11 May 2022).

In the last decade, MRLs for pesticides with agricultural trade are becoming important. In the EU, there are increasing requirements from retailers to their suppliers to provide fruits and vegetables with an amount of pesticide residue below the MRLs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Examples of requests from the retailer of the amount of the Maximum Residue Level (MRL) and Acute reference doses (ARfD).

The substances tested during Casdar programs ‘4P’, ‘Carie’, ‘Sweet’, ‘HE, Ecophyto ‘Usage’ and some from projects have already been described (Marchand, 2016) (Table 6). New projects are ongoing to develop extensions of use, describe better efficacy through better positioning during the season or to investigate compatibility/incompatibility with other biocontrol agents (i.e., reduce copper and macro-organisms). This is the ongoing work for Coperreplace, ABAPIC (ITAB), Vitinnova (UNIVPM), and Euphresco BasicS (Euphresco Network).

Table 6.

Examples of the applications of the basic substances in research projects.

3. Discussion

The use of pesticides, if not appropriate, may lead to problems like contamination of the water, potential damage to sensitive species (e.g., bees), contamination of final food products and water, with up to 90% of applied pesticides not reaching the target species, and, also, because of the development of resistant pathogens and pests [39]. A high number of PPPs were not reauthorized (or companies did not provide the dossier for the reregistration of products out of patent, due to high costs and uncertain benefits) and leaves a gap for several uses. It is important that authorities provide a good number of options to growers to protect their crops, since farmers cannot stand without PPPs for certain crops and uses, and there is an increasing need, because a lot of substance prohibition dates are fixed without substitution mean. Just as an example, this occurred with the fungicide mancozeb in January 2022 and a risk to occur in 2025 with copper, that is fundamental for plant protection in organic agriculture and a good support to prevent the appearing of resistant isolates in IPM. In France, the use of neonicotinoids, known as dangerous insecticides, is extended when there is no other way to preserve crops and productivity. With Farm to Fork Strategy of the European Green Deal, the European Commission is committed to reduce the use of the most dangerous synthetic pesticides of 50% and achieve at least 25% of the EU agricultural land under organic farming by 2030, although the decrease of synthetic pesticides is already ongoing. These trends, together with the implementation of sustainable development goals—SDGs by the United Nations—are demanding for new alternatives, such as basic substances, to tackle some of these issues. To achieve these goals, more research is needed to advance the design of better farming systems and the development of alternatives to synthetic pesticides and to copper formulations.

Three decades ago, the concept of MRLs was poorly known, while, in recent years, MRLs for pesticides arguably have become the first action growers should consider in their pest management decisions [40]. Trying to interpret consumer demands, retailers are increasingly required to reduce pesticide residues even more than the allowed thresholds (MRLs), which are defined considering a wide security factor (e.g., ×100) using the presence of pesticide residues as a factor of competition among companies. Requests from the retailers and consumer to reduce synthetic pesticide residues from fresh produce even more than the allowed threshold, such that the rules defined by the public administration have become more limiting for farmers in terms of the active ingredients allowed and MRLs [40,41]. The reduction of the presence of fungicide residues well beyond MRL may allow the pathogen to develop after harvest, resulting food loss and waste along the value chain. These developments have driven the search for alternative management strategies that are effective and not reliant just on conventional fungicide applications [5,42,43]. European regulation followed and carried this development with the introduction of new classes of phytosanitary products, in particular basic substances, but also new laws and simplification accompanied by the reduction of registration processes of low-risk substances, theoretically. Basic substances are approved for use in the EU and are products that are already sold for certain purposes, e.g., as a foodstuff or a cosmetic. Basic substances may be of major importance in biocontrol and several advantages can explain it. Basic substance regulatory application is simplified [44] and particularly reduced compared to other substances, therefore representing a lower cost to applicant (around 35-40 kEuro for approval of a basic substance and overall around 45 kEuro including approval for organic agriculture), thanks to the fact that these substances are already on the market for another purpose than plant protection, and safety is not an issue to be demonstrated. These substances are good alternatives available today and wide targets. Basic substances can be used in the crop protection as fungicide, bactericide, insecticide, etc., and most of them are allowed in organic production [18,45,46,47]. The basic substances are in order from 2014, when was the first approved application of Equisetum arvense L., chitosan hydrochloride, and sucrose until 2022, when a second chitosan formulation was approved. In some conditions basic substances were already at farm level, with a level of pest management not different than the standard. Just as example, chitosan hydrochloride was also applied in commercial conditions, in the field, and postharvest treatments, and several studies proved that it could have an effectiveness comparable to some commercial PPPs [42,48]. Basic substances, probably less efficient and practical to use than other active substances authorized as PPPs, are known and used by producers since decades as substitution means and have already demonstrated their effectiveness. Basic substances were the perfect tool to provide to producers as known, easy-to-use, less dangerous, and environmentally more respectful. Today, there is a consensus among a wide range of stakeholders that synthetic pesticide used need to be gradually reduced to a level that is effectively required to ensure crop production and that risks of pesticide application should be reduced as far as possible. Basic substances are good alternatives available today in our hands. The use of these substances needs to be integrated in vocational education, training, and technical advice to farmers. Further research around the world on the efficacy of basic substances may prove in the future that these substances can replace pesticides without reducing yields or increasing production costs. To develop the uses and the field trials we listed here the main usages of basic substances. However, rates included in the approval schedule may not produce a significant containment of diseases and pests in specific pathosystems. Just as example, the advised application rate of chitosan hydrochloride is between 100 and 800 g/ha, equal to a concentration ranging among 0.05 and 0.2% with 200–400 L/ha, while trials in commercial vineyards found a good effectiveness delivering the chitosan hydrochloride, with a concentration of at least 0.5% and with a volume of at least 500 L/ha [34,49]. For this reasons, large-scale trials are very important to demonstrate the effectiveness toward pathogens and pests in different environments and growing contexts, and a flexibility could be required in suggested dosages to avoid that applying basic substances at suggested rated can lead to a lack of or poor effectiveness and then the disaffection of users toward these innovative compounds, and this is in contrast with the requirements of finding solutions alternatives to the application of synthetic pesticides keeping the standard quality and quantity of the production, which is one of the drivers of the Farm-to=Fork Strategy of European Green Deal. Moreover, the diluent allowed for basic substance, up to now concretely restricted to water, may be another substance. In this case, vinegar has just been authorized for chitosan. Finally, increasing the demand from growers and competition among companies can lead to the reduction of costs of the treatments that, nowadays, are often higher than standard treatments.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Data

A systematic literature search from 2009 to 2021 was performed using the database of Scopus with the keywords ‘basic substance’ and ‘basic substances’. In the EU, several retailers request an amount of pesticide residue on fruit and vegetables below the legal limit (MRL), and data on some protocols were collected through companies and plant doctors.

4.2. Legislation

Basic substance criteria are defined by article 23 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009, cited in introduction. By way of derogation from Article 4 of this regulation, a basic substance is approved when all relevant evaluations conducted in accordance with other Community legislation, governing other uses of this substance, showing that it has neither an immediate or delayed harmful effect on human or animal health nor any unacceptable influence on the environment. Active substances that could be defined as ‘foodstuff’ are intrinsically considered as basic substances, following Article 2 of Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002. Basic substances shall be approved in accordance with paragraphs 2–6 of regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 and by way of derogation from Article 5, the approval shall be for an unlimited period. By way of derogation from Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009, an application for approval of a basic substance can be made by a Member State or any interested party. At the end of the evaluation process, basic substances shall be listed separately in the Regulation referred to in Article 13(4). The Commission may review the approval of an active substance at any time. It may take into account the request of a Member State to review the approval. Article 28 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 set the absence of marketing authorizations and usages allowance for basic substances. However, no formal authorization is required as long as the product contains exclusively basic substances (see corresponding Review Report) [49,50].

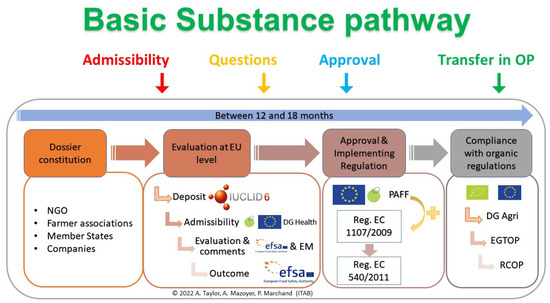

4.3. Approval Process

The approval process of a basic substance starts with a request for approval (Figure 3). The applicant estimates if the substance concerned fulfil all criteria of basic substances category and then complete the BSAT, in English, to obtain a Basic Substance Application. Several guidance documents, such as the official SANCO guide or the teaching guide from the ITAB, have been published to help applicants to build basic substance application correctly [50]. For the transmission of the basic substance application, once completed, the file should be sent to the DGSanté, representing the European Commission (EC). The Basic Substance Application can firstly be sent to national competent authorities for a preassessment and possibly a support. For example, in France, the Basic Substance Application can be sent to the Ministry of Agriculture (DGAl in France), who can ask for the National Authority’ opinion and then transfer the file to the EC. Upon receipt of the Basic Substance Application, EC implements the approval procedure detailed in Article 23 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009. Admissibility may be pronounced at any time, directly or after questions from DGSanté. It constitutes the real start of the application (black line in Figure 3). The first stage is based on the Basic Substance Application evaluation by Member States and EFSA as scientific assistance leading to a request for corrections and questions. The request is sent to the applicant, and his answers shall be sent back within one month to the EFSA. For decision and approval, at the end of the basic substance application evaluation, EFSA will deliver its opinion, append a comment, and send the basic substance application to the DG Health within 3 months for the final vote of Member States in the PAFF committee (Figure 3). Approval, if accorded, is effective at the date of the publication of an implementing Regulation modifying Regulation (EU) No. 540/2011 [8].

Figure 3.

Approval process and timeline of a Basic Substance Application (BSA).

The period of examination of the basic substance application is established in paragraph 1 of article 37 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009. It is said: ‘The Member State examining the application shall decide within 12 months of receiving it whether the requirements for authorization are met. Where the Member State needs additional information, it shall set a period for the applicant to supply it. In that case, the 12-month period shall be extended by the additional period granted by the Member State. That additional period shall be a maximum of 6 months and shall cease at the moment when the additional information is received by the Member State. Where at the end of that period the applicant has not submitted the missing elements, the Member State shall inform the applicant that the application is inadmissible.’ [10]. The maximum delay is therefore set at 18 months. However, although clearly defined, these steps are not so straightforward in many cases [51].

4.4. Extension of Uses Process

The request for an extension is somehow similar, except the need of support from corresponding agricultural sectors at the deposit step. Some extensions were voted after submission, some others were granted with admissibility and voted rapidly after; some later were following the full approval pathway, including admissibility, evaluation, outcome, full vote at PAFF Committee (appearance in Part A (lecture, discussion), C (proposal) and B (effective vote)). This latter process sometimes takes the same amount of time compared to a new approval, which is considered very excessive by the applicants, having an approved substance at the beginning of their request and only asking for one line sometimes in the Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) table.

4.5. Regulation Analysis

The EU Pesticides Database [52] was used to detect basic substances and their status (approved, nonapproved, pending, and modifications of Review Reports). Corresponding linked Implementing Regulations [20] attached to each active substance were found using the same method and cross-verified with Implementing Regulation (EU) 540/2011. The EU law database for Eur-Lex was also used to track each Implementing Regulation publication. Furthermore, EFSA documents were also compiled to extract decisions supportive analyses.

5. Conclusions

Searching for alternative products for crop protection is an important strategy for promoting more sustainable food systems. The use of basic substances is in line with the restriction on the application of chemical PPPs and the principles of the European Green Deal and SDGs, mostly renewables and with no MRL. There is relatively poor information about the effectiveness of basic substances as compared to synthetic pesticides and biological PPPs. A higher testing and validation of the use of basic substances as a phytosanitary measure can lead to further reduction of application of synthetic pesticides. In addition, searching for the most effective dosage of the basic substance is critical and an important question for phytosanitary consultants (the plant doctors that are opinion leaders in application of innovations in pest management), growers, stakeholder, and companies to avoid that their application at the recommended dose can lead to a lack of or poor effectiveness of these substances. For this reason, a flexibility might be required in the suggested dosage of basic substances approved to ensure good maintenance of the quality and quantity of production, which is one of the keys of the Farm to Fork Strategy of the European Green Deal. Moreover, a defined timeline for approval is basilar to have the chance to increase the number of basic substances available for growers, the scientific community, and the whole agricultural sector, with final benefits for the consumers.

6. Patents

All Implementing Regulations may be considered as patents but with free exploitation, since no Marketing Authorizations are needed for basic substances.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules27113484/s1, Figure S1: Time needed for Basic Substance Application admissibility evaluation over time (bars) and tendency line (dotted line); Table S1: Total time of basic substance application process within admissibility to Implementing Regulation publication in months.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R. and P.A.M.; methodology, Y.O. and M.M.; resources, G.R., Y.O., Y.D., M.M. and P.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R., Y.O., Y.D., M.M. and P.A.M.; writing—review and editing, G.R., Y.D., M.M. and P.A.M.; supervision, G.R. and P.A.M.; and funding acquisition, G.R. and P.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

For G.R. and M.M., this work was conducted within the framework of the PSR ZeroSprechi, PSR Vitinnova, PSR CleanSeed, and of PRIMA StopMedWaste projects, which are funded by PRIMA, a program supported by the European Union. For Authors Y.O., Y.D., and P.A.M., the French Ministry of Agriculture (CASDAR ‘4P’, ‘Contrat de branche Carie’, ‘Sweet’, and ‘HE’; Ecophyto ‘Usage’, ’Biocontrol’ ’INADOM’, and ’PARMA’), French Ministry of Ecology (Project ‘PNPP‘ CT0007807, ‘SubDOMEx‘, and ‘Jussie‘). All authors worked within the “Euphresco BasicS (Objective 2020-C-353) project. Thanks are expressed to Antonello Lepore, Gianni Ceredi and other technicians for providing data about pesticide residues requested by retailers.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nation. Growing at a Slower Pace, World Population Is Expected to Reach 9.7 billion in 2050 and Could Peak at Nearly 11 billion around 2100. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2019.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- FAO. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1402920/icode/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz-Pfeilstetter, A.; Mendelsohn, M.; Gathmann, A.; Klinkenbuß, D. Considerations and regulatory approaches in the USA and in the EU for dsRNA-based externally applied pesticides for plant protection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 682387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanazzi, G.; Smilanick, J.L.; Feliziani, E.; Droby, S. Integrated management of postharvest gray mold on fruit crops. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 113, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chèze, B.; David, M.; Martinet, V. Understanding farmers’ reluctance to reduce pesticide use: A choice experiment. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D.; Marchand, P.A. Evolution of Directive (EC) No 128/2009 of the European parliament and of the council establishing a framework for Community action to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides. JRS 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Commission Implementing Regulation No 540/2011 of 25 May 2011 implementing Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European parliament and of the council as regards the list of approved active substances. OJ 2011, L153, 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Matyjaszczyk, E. Problems of implementing compulsory integrated pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2063–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D.; Marchand, P.A. Biocontrol active substances: Evolution since the entry in vigour of Reg. 1107/2009. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Commission Regulation No 1107/2009 of the European parliament and of the council of 21 October 2009 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market and repealing council directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC. OJ 2009, L309, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, J.; Roszkowski, S.; Krzymińska, J. Substancje podstawowe—Efektywne uzupełnienie metod ochrony upraw. Basic substances—An effective supplement to crop protection methods. Prog. Plant Prot. 2021, 61, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, P.A. Basic and low-risk substances under European Union pesticide regulations: A new choice for biorational portfolios of small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2017, 57, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Charon, M.; Robin, D.; Marchand, P.A. The importance of substances without maximum residue limit (MRL) in integrated pest management (IPM). Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2019, 23, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Regulation No 178/2002 of the European parliament and of the council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. OJ 2002, L31, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Euphresco. BasicS Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/project/EUPHRESCO-Basic-substances-as-an-environmentally-friendly-alternative-to-synthetic-pesticides-for-plant-protection-BasicS (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Marchand, P.A.; Davillerd, Y.; Riccioni, L.; Sanzani, S.M.; Horn, N.; Matyjaszczyk, E.; Golding, J.; Roberto, S.R.; Mattiuz, B.-H.; Xu, D.; et al. BasicS, an euphresco international network on renewable natural substances for durable crop protection products. Chron. Bioresour. Manag. 2021, 5, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, G.; Feliziani, E.; Sivakumar, D. Chitosan, a biopolymer with triple action on postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables: Eliciting, antimicrobial and film-forming properties. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Working Document on the Procedure for Application of Basic Substances to be Approved in Compliance with Article 23 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009; SANCO/10363/2012 rev. 10; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 25 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EU. EU Pesticides Database (v.2.2) Search Active Substances, Safeners and Synergists (europa.eu). 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/active-substances/?event=search.as (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Matyjaszczyk, E. Plant protection means used in organic farming throughout the European Union. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, P.A. Basic substances under EU pesticide regulation: An opportunity for organic production? Org. Farming 2017, 3, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) amending and correcting Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/1165 authorising certain products and substances for use in organic production and establishing their lists. Official J. Eur. Union 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, P.A.; Isambert, C.A.; Jonis, M.; Parveaud, C.-E.; Chevolon, M.; Gomez, C.; Lambion, J.; Ondet, S.J.; Aveline, N.; Molot, B.; et al. Evaluation des caractéristiques et de l’intérêt agronomique de préparations simples de plantes, pour des productions fruitières, légumières et viticoles économes en intrants. Innov. Agron. 2014, 34, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- CASDAR 4P, Protéger les Plantes Par les Plantes. 2014. Available online: https://ecophytopic.fr/recherche-innovation/proteger/projet-4p (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- COPPEREPLACE. 2015. Available online: https://coppereplace.com/fr/project-coppereplace/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Robin, N.; Bruyere, J. Traitements de semences: Contrôler la carie. In Actes Journée Technique; ITAB: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 31–40. Available online: http://www.itab.asso.fr/downloads/actes%20suite/carie-actes2012.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Arnault, I.; Bardin, M.; Ondet, S.; Furet, A.; Chovelon, M.; Kasprick, A.-C.; Marchand, P.; Clerc, H.; Davy, M.; Roy, G.; et al. Utilisation de micro-doses de sucres en protection des cultures. Innov. Agron. 2015, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Arnault, I.; Aveline, N.; Bardin, M.; Brisset, M.N.; Carriere, J.; Chovelon, M.; Delanoue, G.; Furet, A.; Frérot, B.; Lambion, J.; et al. Optimisation des stratégies de biocontrôle par la stimulation de l’immunité des plantes avec des applications d’infra-doses de sucres simples. Innov. Agron. 2021, 82, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, R.; Muchembled, J.; Deweer, C.; Tournant, L.; Corroyer, N.; Flammier, S. Évaluation de l’intérêt de l’utilisation d’huiles essentielles dans des stratégies de protection des cultures. Innov. Agron. 2018, 63, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Compo Expert. Report 2015. In LA PUGERE, 2011 Pear Psylla [Psylla piri], The TALC Efficiency Evaluation in a Preventive Control Strategy of the Pear Psylla Year; Station d’experimentation La Pugere: Mallemort, France, 2015; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- CA (Chambre d’Agriculture de l’Aude). Réduction des coûts en viticulture. Produits Alternatifs: Lactosérum [Reducing Costs in Viticulture: Alternative Crop Protection: Lactoserum]; Technical Report; Chambre d’Agriculture de l’Aude (CA11): Carcas-sonne, France, 2011; 123p. [Google Scholar]

- Duriez, J.M. Le phosphate di-ammonium, un attractant de la mouche de l’olive Journées Techniques Intrants; ITAB: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: http://www.itab.asso.fr/downloads/jt-intrants-2016/10_duriez-afidol-pda.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Montag, J.; Schreiber, L.; Schönherr, J. The post-infection activity of hydrated lime against conidia of Venturia inaequalis. In Proceedings of the Ecofruit-12th International Conference on Cultivation Technique and Phytopathological Problems in Organic Fruit-Growing, Weinsberg, Germany, 31 January–2 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, G.; Piancatelli, S.; D’Ignazi, G.; Moumni, M. Innovative approaches to grapevine downy mildew management on large and commercial scale. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Grapevine Downy and Powdery Mildew, Cremona, Italy, 20–22 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, G.; Moumni, M. New challenges in preventing and managing fresh fruit loss and waste. In Proceedings of the VI International Symposium on Postharvest Pathology, Limassol, Cyprus, 29 May–2 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ortenzio, A.L.; Fava, G.; Mazzoni, S.; Acciarri, P.; Baronciani, L.; Ceredi, G.; Romanazzi, G. Postharvest application of natural compounds and biocontrol agents to manage brown rot of stone fruit. In Proceedings of the VI International Symposium on Postharvest Pathology, Limassol, Cyprus, 29 May–2 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Piancatelli, S.; Moumni, M.; Binni, T.; Giardini, D.; Profili, R.; Napoleoni, D.; Morbidelli, M.; Fabbri, G.; Piersanti, G.; Nardi, S.; et al. Impiego di sostanze di origine naturale e a basso impatto ambientale nella protezione del cavolo cappuccio da seme. Giornate Fitopatol. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.W.; Yang, Y.S.; Lee, Y.U.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.P.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, D.; Song, N.; et al. Pesticide residues and risk assessment from monitoring programs in the largest production area of leafy vegetables in South Korea: A 15-year study. Foods 2021, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahhal, I.; El-Nahhal, Y. Pesticide residues in drinking water, their potential risk to human health and removal options. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, M.; Grant, J.H.; Peterson, E. Trade impact of maximum residue limits in fresh fruits and vegetables. Food Policy 2022, 106, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Feliziani, E.; Baños, S.B.; Sivakumar, D. Shelf life extension of fresh fruit and vegetables by chitosan treatment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Sanzani, S.M.; Bi, Y.; Tian, S.; Gutierrez-Martinez, P.; Alkan, N. Induced resistance to control postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D.; Marchand, P.A. Expansion of the low-risk substances in the framework of the European Pesticide Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, P.A. Basic substances: An opportunity for approval of low-concern substances under EU pesticide regulation. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, P.A. Basic substances under EC 1107/2009 phytochemical regulation: Experience with non-biocide and food products as biorationals. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2016, 56, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykogianni, M.; Bempelou, E.; Karamaouna, F.; Aliferis, K.A. Do pesticides promote or hinder sustainability in agriculture? The challenge of sustainable use of pesticides in modern agriculture. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanazzi, G.; Mancini, V.; Foglia, R.; Marcolini, D.; Kavari, M.; Piancatelli, S. Use of chitosan and other natural compounds alone or in different strategies with copper hydroxide for control of grapevine downy mildew. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3261–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU. Working Document on the Procedure for Application of Basic Substances to be Approved in Compliance with Article 23 of Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 SANCO/10363/2012; (rev. 9 of 21 March 2014); EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/456 of 21 March 2022 approving the basic substance chitosan in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market, and amending the Annex to Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011. OJ 2022, L93, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, P.A.; Carrière, J. Guide Pédagogique: Constituer un dossier d’approbation de substance naturelle au règlement (CE) n°1107/2009; ITAB: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekemans, M.C.; Marchand, P.A. The fate of the Biocontrol agents under the European phytopharmaceutical regulation: A hindering for approval botanicals as new active substances? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39879–39887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).