Abstract

Herbal medicine is still widely practiced in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq, especially by people living in villages in mountainous regions. Seven taxa belonging to the genus Teucrium (family Lamiaceae) are commonly employed in the Kurdish traditional medicine, especially to treat jaundice, stomachache and abdominal problems. We report, in this paper, a comprehensive account about the chemical structures and bioactivities of most representative specialized metabolites isolated from these plants. These findings indicate that Teucrium plants used in the folk medicine of Iraqi Kurdistan are natural sources of specialized metabolites that are potentially beneficial to human health.

1. Introduction

Nature is a major source of current medicines, and many (semi)synthetic drugs have been developed from the study of bioactive compounds isolated from extracts of plants used in traditional medicines of different countries [1]. Kurds—the peoples living in Turkey, Iran and other East Asian countries—have been practicing traditional medicine from a time immemorial. In fact, the practices of medicinal plant uses are transmitted orally as a part of the Kurdish cultural heritage. Moreover, the popularity of herbal remedies has increased among Kurds during the last two decades, in part because of the high cost of synthetic drugs, which are mainly imported from abroad. Thus, in rural communities, herbal remedies are the first choice for the treatment of many diseases and practitioners of traditional medicine dispense primary care. However, also in the markets of the big cities, such as in the Qaysary Market located in the centre of Erbil (Irbil), the capital of the Kurdistan Region, Iraq (KRI) (Figure 1), several shops sell different natural medicinal products [2]. It is interesting to note that about 64% of these products have their origin outside Iraqi Kurdistan, being imported from countries as far away as India, Spain and Libya, while only 36% come from different districts within the Kurdistan Region [2].

Figure 1.

The approximate map of the Kurdish-populated region (“Kurdistan”) which includes parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran (taken and adapted from https://www.bing.com/images/search for Kurdistan, latest accessed on 24 April 2022).

Despite the wide use of herbal remedies, a limited number of papers have been published in Kurdistan concerning the structures and bioactivities of specialized metabolites isolated from native plants [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. With the aim to add more value to the medicinal plants growing in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq, to sustain their uses with scientific evidence of the efficacy and to foster further investigations, we report in this paper a comprehensive account of the structures and bioactivities of most representative compounds isolated from Teucrium taxa used in the traditional medicine of the Kurdistan Region.

Iraqi Kurdistan or Southern Kurdistan refers to the Kurdish-populated part of northern Iraq (Figure 1). It is considered one of the four parts of “Kurdistan” in Western Asia, which also includes parts of southeastern Turkey, northern Syria and northwestern Iran (Figure 1). Much of the geographical and cultural region of Iraqi Kurdistan is part of the Kurdistan Region, Iraq (KRI), an autonomous region ruled by the Kurdish Regional Government, which is recognized by the Constitution of Iraq. As with the rest of Kurdistan, and unlike most of the rest of Iraq, the region is inland and mountainous.

2. Ethnobotanical Data about the Teucrium Species Growing in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq

Teucrium L. is the second-largest genus of the subfamily Ajugoideae in the family Lamiaceae (Labiatae), with a subcosmopolitan distribution and more than 430 taxa with accepted names [20,21]. Mild climate regions, such as the Mediterranean and the Middle East areas, contain about 90% of the total Teucrium taxa [22]. Most Teucrium have been used in several traditional medicines for thousands of years, and have different potential applications, from pharmaceutical to food industries, primarily due to the high content of specialized metabolites with significant biological activities. It is interesting to note that the name Teucrium derives from the Greek terms “τευχριον—teúcrion”, in honor of an ancient Trojan king who, according to the Roman historiographer Pliny, was the first one to utilize these plants for medical purposes. In fact, various compounds isolated from Teucrium taxa have shown antipyretic, diuretic, diaphoretic, genotoxic, antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anticancer, cholesterol-lowering, hypoglycemic, anti-malaria, spasmolytic, anti-inflammatory and even antifeedant properties [23,24,25,26,27]. A comprehensive study on the entire Teucrium genus, reviewing the publications conducted in the last two decades was published recently, during the final preparation of this paper [28].

Seven Teucrium taxa are used in the traditional medicine practiced in the Kurdistan Region [22,23], where these plants grow abundantly in certain areas. In Table 1, we report the botanical names, the traditional uses and the growth places in Iraqi Kurdistan. Decoctions and infusions are the most frequently used procedures in the preparation of traditional remedies from these Teucrium plants.

Table 1.

Teucrium taxa used in the traditional medicine of the Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

In addition, to the plants listed in Table 1, T. multicaule Montbret & Aucher ex Benth., T. procerum Boiss. & C. I. Blanche, T. pruinosum Boiss., Teucrium orientale ssp. taylorii (Boiss.) Rech.f. (synonym T. taylorii Boiss.) grow across the rest of Iraq [29,30].

3. Phytochemistry and Ethnopharmacology of Teucrium Taxa Used in the Traditional Medicine of the Kurdistan Region—Iraq Methods for the Literature Search

In this inaugural paper on the phytochemical and ethnopharmacological aspects of Teucrium taxa used in the traditional medicine of Iraqi Kurdistan (Table 1), the pertinent literature was reviewed from 1970 until the end of November 2021 using the Reaxys, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Scifinder, PubChem and PubMed databases. Terms and keywords used for the survey have been the “botanical name of each taxon”, “Germander”, “Kurdistan traditional medicine”, “Kurdistan Teucrium” and “Teucrium metabolites”. Since the plants listed in Table 1 are also used in the traditional medicines of other countries, especially in the Middle East, for the sake of completeness, we extended our survey to the entire literature on the phytochemistry and ethnopharmacology of most representative specialized metabolites isolated from the plants listed in Table 1. In fact, most scientific data about these plants were gathered outside Kurdistan.

The molecular structures of identified representative compounds, divided in accordance with the biogenesis, are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, whereas, in addition to Table 1, traditional uses and data of biological activities in vitro are reported in Table 2.

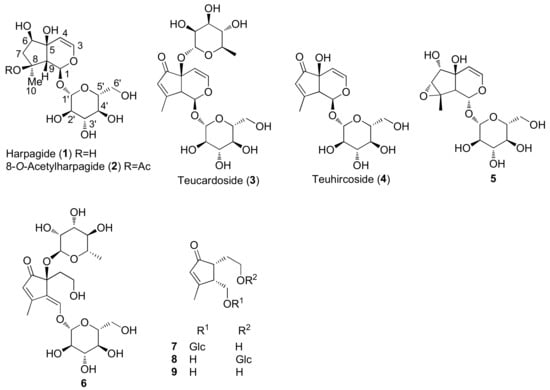

Figure 2.

Representative iridoids and iridoid glycosides isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys, Teucrium oliverianum and Teucrium polium.

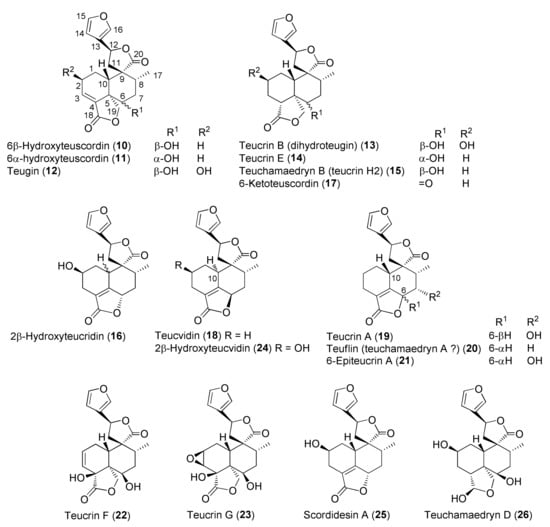

Figure 3.

Representative neo-clerodane diterpenoids isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys and Teucrium scordium subspecies scordioides.

Figure 4.

Representative neo-clerodane diterpenoids isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys and Teucrium oliverianum.

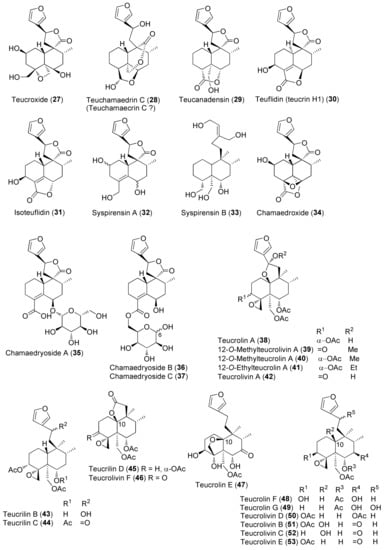

Figure 5.

Representative neo-clerodane diterpenoids isolated from Teucrium polium.

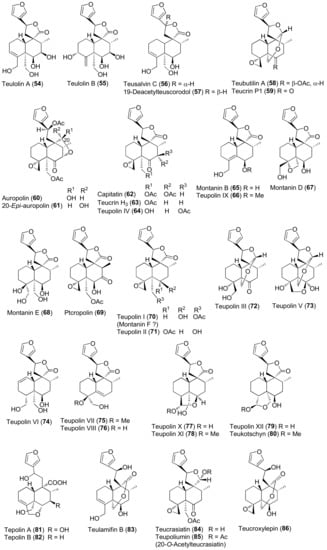

Figure 6.

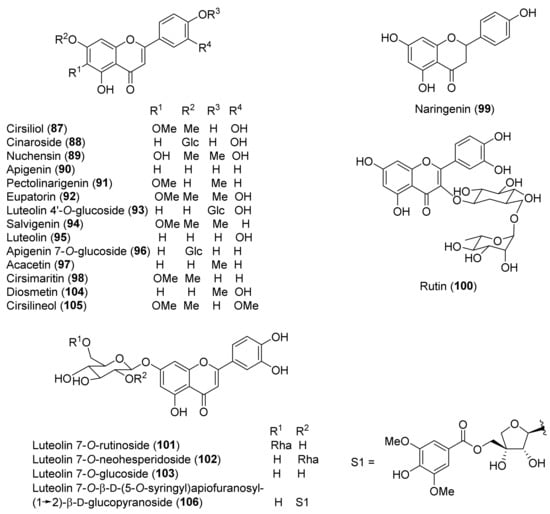

Representative flavonoids isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys, Teucrium oliverianum and Teucrium polium.

Figure 7.

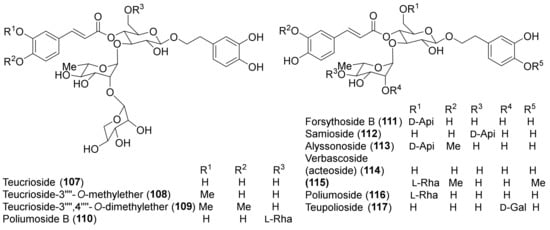

Representative verbascoside derivatives isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys and Teucrium polium.

Figure 8.

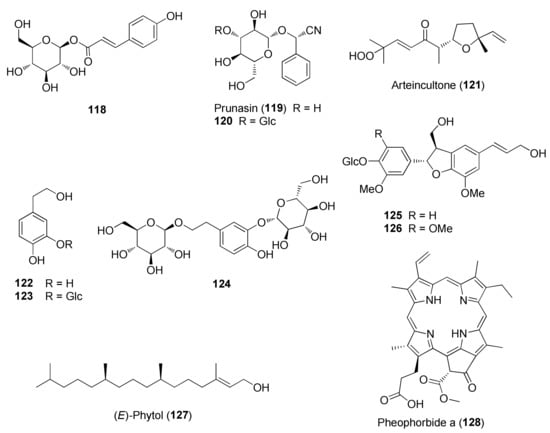

Representative phenolics, lignans and miscellaneous compounds isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys and Teucrium polium.

Figure 9.

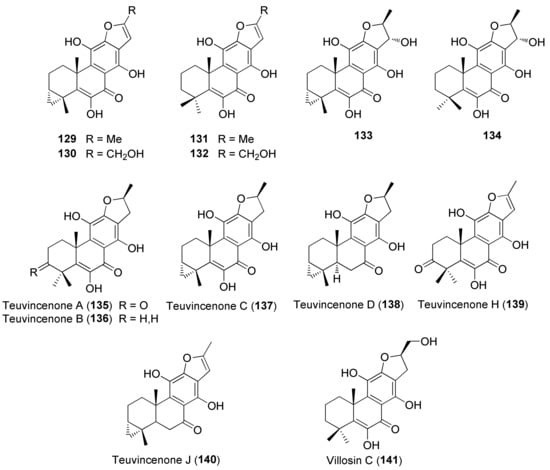

Representative abeo-abietane diterpenoids isolated from Teucrium polium.

Figure 10.

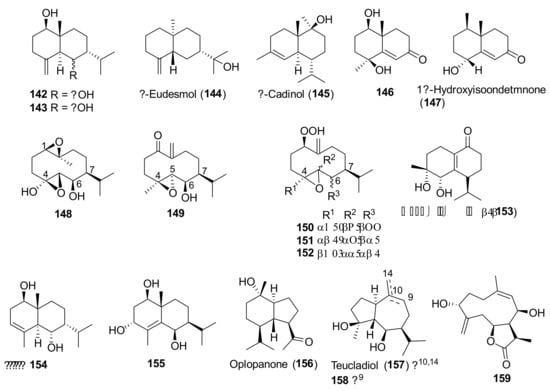

Representative sesquiterpenoids isolated from Teucrium polium.

Figure 11.

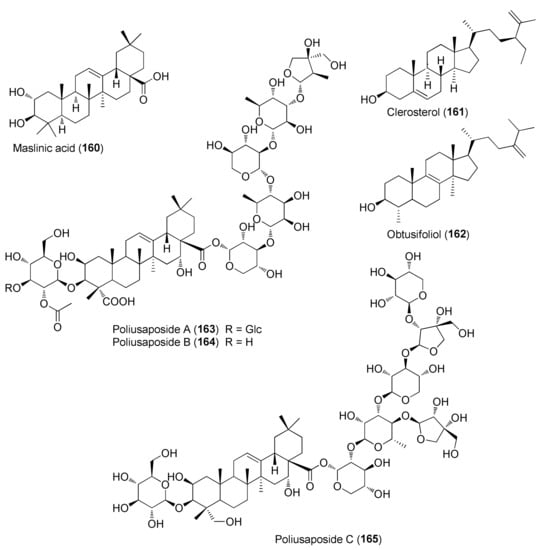

Representative triterpenoids and sterols isolated from Teucrium polium.

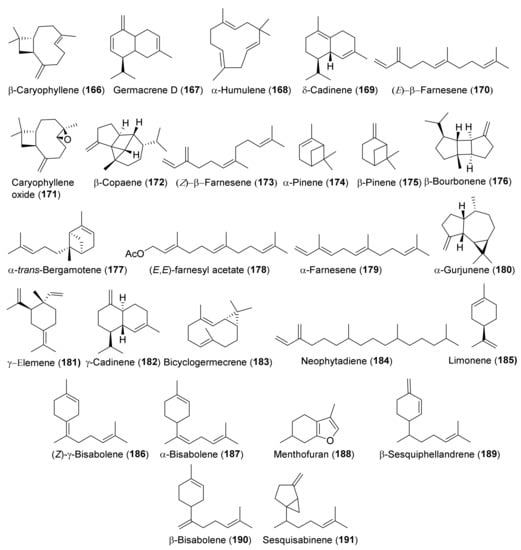

Figure 12.

Representative terpenoids contained in essential oils isolated from Teucrium taxa.

Table 2.

Traditional uses, biological activities and specialized metabolites isolated from Teucrium taxa used in the traditional medicines of the Kurdistan Region, Iraq, and other countries.

3.1. Phytochemical Aspects

A survey of the literature reveals that more than 290 compounds have been identified in the essential oils and non-volatile extracts from the Teucrium taxa used in the folk medicine of the Kurdistan Region, Iraq (Table 1). They include mono-, sesqui-, di- and triterpenoids, steroids, flavonoids, phenylethanoid glycosides, etc.

No phytochemical investigation has yet been dedicated to T. rigidum Benth. Essential oils (EOs) are the most analyzed phytochemical parts of the other taxa listed in Table 1, except the oil from T. oliverianum. EOs were isolated by conventional hydrodistillation in a Clevenger apparatus and were analyzed by standard GC-FID and GC-MS techniques. Both polar (Carbowax 20M) and non-polar (OV1 and SE 30) columns were used. EOs can, in general, be divided between those where the main components are sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, such as β-caryophyllene (166) and germacrene D (167), as the oil from T. parviflorum, and the oils where monoterpene hydrocarbons, such as α- (174) and β-pinene (175) predominate, as the oil from T. melissoides. There are significant qualitative and quantitative differences between the EOs of the different taxa and this variability is even intraspecific, which is probably due to the genetic, differing chemotypes, drying conditions, mode of oil distillation, extraction and/or storage, and geographic or climatic factors. The compositions of the EOs isolated from specimens of T. chamaedrys and T. polium collected in different countries, are typical examples of such variability [26]. The high content of menthofuran (188) in the EO from T. scordium subsp. scordioides collected in Serbia [132] indicates that this terpenoid can be considered a chemotaxonomic marker of the oil.

Regarding the structures of non-volatile secondary metabolites, those occurring in T. melissoides and T. parviflorum are still unknown and only a few studies have been dedicated to the contents in extracts from T. oliverianum and T. scordium subspecies scordioides. Instead, the phytochemical aspects of T. chamaedrys and T. polium have been subjected to several investigations. These studies have possibly been promoted by the worldwide occurrence and widespread medicinal uses of the two plants.

Among monoterpenoids, the presence of iridoids, as aglycones and glycosides, in T. chamaedrys, T. oliverianum and T. polium extracts, confirms the observation that they are chemotaxonomic markers of the Lamiaceae family and have been recognized in several genera of the Ajugoideae and Lamioideae subfamilies.

Non-volatile sesquiterpenoids 142–159 (Figure 10) were so far isolated from only T. polium [81,88,95]. Most of them belonged to the eudesmane, cadinane and germacrane families.

Diterpenes include representatives of the abeo-abietane and neo-clerodane families. Compounds of the first group (129–141) have been isolated only from T. polium [90]; on the other hand, T. chamaedrys, T. oliverianum and T. polium are rich sources for neo-clerodane diterpenoids (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Indeed, these compounds probably represent the most abundant family of specialized metabolites occurring in Teucrium taxa and are considered the chemotaxonomic markers of the genus [134]. The reason of the wide distribution and conservation of neo-clerodanes might be likely due to their potential allelopathic properties [39], a pronounced protective role against herbivore predators and the general antifeedant activity [25,134]. Thus, the last effects may have economic importance against Lepidopterous pests [135]. Most neo-clerodanes shown in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 contain a characteristic trans-fused decalin core with an α-spiro 4-(3-furyl)-γ-butyrolactone-based side chain attached to C-9. Representative structures are compounds 10–26. However, the lactone ring may be absent, as in 47–53 and even the furan moiety may be missing, as in syspirensin B (33). Except for teupolins VII (75) and VIII (76), the carbon C-6 is oxygenated. Other frequently oxygenated carbons are C-2, C-3, C-7, C-12, C-18, C-19 and, rarely, C-10, as in neo-clerodanes 45, 47, 50 and 51. Moreover, the presence of an epoxide, as in 23 and 38, an oxetane, as in 27, 34 and 67, a tetrahydrofuran, as in 47 and 81, a hemiacetal or an acetal, as in 26, 58, 60, 73, 79, a γ-lactone, as in 13, 16, 29, 34, 45, or a δ-lactone ring, as in 28, 83, 86, add to complicate the chemical structures of these diterpenoids.

The NMR data of representative Teucrium sesquiterpenes, neo-clerodane and abeo-abietane diterpenoids are thoroughly discussed in reference [25].

Readers must be aware that some ambiguities exist in the literature about the names and even the stereochemistry of a few neo-clerodane diterpenoids isolated from Teucrium. Typical examples are compound 16, teucvidin (18) and syspirensin A (32). These uncertainties depend on the fact that chemical structures were based mainly on the interpretation of NMR spectra, while only a few ones were firmly confirmed by X-ray analysis [56] or stereoselective total synthesis [53]. The chemical structures depicted in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 are reported in the most recent publications.

The group of sterols and triterpenoids comprises compounds widely distributed in plants, such as β-sitosterol, campesterol and oleanolic acid, but also novel triterpene saponins, poliusaposides A-C (163–165), that were isolated from a MeOH extract of T. polium aerial parts.

Flavonoids, in glycosidic and aglycone forms (Figure 6), are relatively abundant in T. chamaedrys and T. polium, while only a couple of compounds, 87 and 92, occurred in T. oliverianum extracts [72,73]. The most characteristic flavonoids are the flavones apigenin (90) and luteolin (95) and a small group of derivatives, including 4′- and 7-O-glycosides and some 6-methoxy flavones. It is worth noting that luteolin 7-O-β-D-(5-O-syringyl)apiofuranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (106), isolated from a MeOH extract of T. polium leaves, contains an unprecedented structure [92]. Other classes of flavonoids are rarely represented in the extracts. In fact, the only flavanone isolated so far has been naringenin (99), from T. chamaedrys subsp. chamaedrys, while the only isolated flavonol O-glycoside has been rutin (100), from extracts of T. polium [87,90]. A rare 6,8-di-C-glucoside, vicenin-2, was also isolated from T. polium [118].

Among other phenolic derivatives, only a couple of lignans (125 and 126) have been isolated [96]. This finding is quite interesting because lignans, phenylpropanoid dimers, are produced as a result of plant defense against stress. On the other hand, T. chamaedrys and T. polium are good sources of phenylethanoid glycosides, the verbascoside derivatives 107–117 (Figure 7).

3.2. Bioactivity and Pharmacological Properties

Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging properties have been determined for most extracts and isolated phytochemicals described in this review, including EOs [26,76], iridoid glycosides [85], abeo-abietanes [90], phenyl ethanoid glycosides [38,85] and flavonoids [85,88,92]. However, such antioxidant action has usually been evaluated through various standard in vitro assays, in cell-free systems, which included cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) assay [88], DPPH scavenging (DPPH), reducing power (RP), xanthine oxidase inhibitory effect (XOI) and antioxidant activity in a linoleic acid system (ALP) [85]. Therefore, these evaluations have limited pharmacological relation and limit the validation of the established biological action. Moreover, the antioxidant activity of an extract may be due to a synergistic effect of the various components through different antioxidant mechanisms,

Antibacterial and other bioactivities of EOs have been described in detail in a previous review [26]. An interesting potential application of the antimicrobial power of EOs, for example that from T. polium, concerns the implementation as preservative additives in the food industry in order to fight microbial contaminations and development [26,36] and lipid oxidation [123].

A study of the relationship between structure and antioxidant effects has been performed on verbascoside (114) and derivatives (Figure 7). The activity varied, depending on the glycosylation and methylation patterns. It was observed that increasing sugar units with accompanying free-phenolic-hydroxyl pairs increased antioxidant activity, while hydroxyl methylation decreases this effect [88]. Thus, poliumosides 110 and 116 showed the highest antioxidant capacity. It was suggested that phenolic hydroxyl pairs form hydrogen bond between adjacent groups that can stabilize phenoxy radical intermediates. Instead, hydroxyl methylation destabilizes the intermediate by disrupting hydrogen bonding [88]. Noteworthy, compounds 114 and 116 with free ortho-dihydroxyl groups showed higher activity than the positive controls, trolox and α-tocopherol [88]. A similar trend was observed with the radical scavenging activity of a group of flavonoids isolated from T. polium [85,92]. Luteolin (95) and luteolin-based compounds with a free ortho-dihydroxy group in ring B elicited a massive reduction of the radical species, whereas luteolin 4′-O-glucoside (93) and apigenin (90) showed very low or no radical scavenging and reducing properties. This finding underlined that the structural feature responsible for the observed activity is the presence of a C-2–C-3 double bond, a carbonyl group at C-4 and, more importantly, a free ortho-dihydroxy (catechol-type) substitution in the flavone B-ring. The authors suggested that the formation of flavonoid phenoxy radicals may be stabilized by the mesomeric equilibrium to ortho-semiquinone structures [85]. In this regard, the higher scavenging and reducing activities of compounds 110 and 116, with respect to flavonoid glycosides, could be attributed to the presence of a second phenolic ring in the caffeoyl residue with an ortho-dihydroxy group [85]. Flavonoid aglycones showed more potent antiradical action than their corresponding O-glycosides in the A or B ring and a disaccharide moiety bound to the C-7 of the A-ring weakens the antiradical effect, as observed for luteolin 7-O-rutinoside (101) and luteolin 7-O-neohesperidoside (102), compared to luteolin 7-O-glucoside (103) and luteolin (95). In contrast to these findings, T. polium flavonoids 101–103 showed a lower xanthine oxidase inhibitory (XOI) activity than compound 93. It was suggested that the presence of a free C-4′ hydroxyl group in compounds 101–103 makes them more easily ionizable and, therefore, less able than flavonoid 93 to interact with the hydrophobic channel, which is the main access to XO active site [85].

Among other bioactive metabolites, the iridoid harpagide (1) exerted a wide number of biological activities such as cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, anti-osteoporotic and neuroprotective effects [136]. Similarly, 8-O-acetylharpagide (2) showed vasoconstrictor [137], antitumoral, antiviral, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. Notably, an inconsistent connection between anti-tumor and antioxidant/radical scavenging activity was observed for the iridoids 2 and teucardoside (3) and poliumoside (116), which resulted in varied effects on several cancer cell lines. This finding is consistent with some in vivo studies [88]. Moreover, iridoids 2 and 3 exhibited an extraordinary ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation [85]. It was suggested that the presence of a free hydroxyl group on C5 of the iridoid 2 could be responsible for the higher antioxidant ability than compound 3 [85].

The saponin glycosides poliusaposides A-C (163–165) were evaluated for anticancer effects by a National Cancer Institute 60 human tumor cell line screen (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/btb/ivclsp.html, latest accessed on 24 April 2022) [98]. Poliusaposide C (165) completely inhibited the growth of a breast (MDA-MB-468) and colon cancer line (HCC-2998) and partially inhibited the growth of a colon (COLO 205), renal (A498) and melanoma cancer (SK-MEL-498) cell line [98]. The other two saponins were considerably less active. By analogy with previously reported bidesmosidic saponins, it was suggested that the increased activity of 165, compared to 163 and 164, was linked to the presence of multiple apiose units, the apiose branching in the oligosaccharide moiety attached to C-28, the difference in glycan chain polarity and the increased aglycone hydroxylation, due to the reduction of the triterpenoid carboxylic acid group to a primary alcohol [98].

Verbascoside (114) exhibited anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, anti-infective and protein kinase C inhibitory properties [138]; moreover, compound 114 and forsythoside B (111) exerted strong neuroprotective and antiseptic effects [32,139].

The hypoglycemic effect of T. polium has been accounted for by its constituents that increase insulin release [105]. In this context, the effect of the major flavonoids occurring in T. polium extract, rutin (100) and apigenin (90), on insulin secretion at various glucose concentrations was investigated [89]. The two flavonoids demonstrated protective effects on β-cell destruction in a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes, due to the antioxidant activity [89]. Among other flavonoids isolated from T. polium, cirsiliol (87) showed good relaxant, sedative and hypnotic effects [32]. Moreover, 3′,4′,5-trihydroxy-6,7-dimethoxyflavone and 5,6,7,3′,4′-pentahydroxyflavone, carrying a 3′,4′-dihydroxy B-ring pattern, showed an interesting inhibitory activity against the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus aureus strain AH133. It was suggested that due to the antibacterial activity, these flavonoids can potentially be used for coating medical devices such as catheters [96]. Antibacterial activity of the crude extract of T. polium, as well as of isolated flavonoid salvigenin (94) and sesquiterpenoids 151 and 154, was observed with Staphylococcus aureus anti-biofilm activity in the low μM range [95]. It should be noted that biofilm formation is a physical strategy that bacteria employ to effectively block the penetration and toxicity of antibiotics. Thus, blocking or retarding the formation of biofilms improves the efficacy of antibiotics.

Shawky in a network pharmacology-based analysis showed that T. polium had potential anti-cancer effects against A375 human melanoma cells, TRAIL-resistant Huh7 cells and gastric cancer cells, likely due to luteolin (95) occurrence in the plant. In fact, luteolin inhibited the proliferation and induced the apoptosis of A375 human melanoma cells by reducing the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 proteinases through the PI3K/AKT pathway [140].

Moreover, it was found that the aqueous extract of T. polium aerial parts, given intraperitoneally, reduced significantly the serum levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in hyperlipidemic rats. It was suggested that the presence of flavonoid and terpenoid constituents may play a role in the observed hypolipidemic effects [106].

Although many crude extracts or partially purified fractions from Teucrium have showed various beneficial biological and pharmacological effects (see the literature cited in Table 2), the use of herbal remedies prepared from Teucrium plants should be considered with caution unless the safety has been demonstrated by rigorous scientific evidence. A paradigmatic example is T. chamaedrys, commonly known as ‘germander’, which has long been used as dietary supplement for facilitating weight loss or as a hypoglycemic aid. However, acute and chronic hepatitis and even fatal cirrhosis were observed in patients who had consumed the plant as a tea for 3–8 weeks [35,141]. Subsequently, similar hepatotoxicity was observed with other members of the Teucrium genus, including the widely used T. polium [142,143]. These toxic effects have mainly been associated with the presence of abundant neo-clerodane diterpenoids, especially teucrin A (19) [54]. In fact, Lekehal and collaborators, while studying the in vivo hepatotoxicity of teucrin A (19) and teuchamaedryn A (20), as well as the furano diterpenoid fraction of T. chamaedrys, demonstrated that the furan ring of neo-clerodane diterpenoids is bioactivated by CYP3A (cytochrome P450 enzymes) into electrophilic metabolites that covalently bind to hepatocellular proteins, deplete GSH and cytoskeleton associated protein thiols and lead to formation of plasma membrane blebs and apoptosis in rat hepatocytes [42,142]. 1,4-Enedials or possible epoxide precursors are the likely reactive toxic metabolites [143]. In contrast to these findings, 18 neo-clerodane diterpenes containing a 3-substituted furan ring, isolated from T. polium, showed low toxicity at the highest test concentration (200 μM) against HepG2 human cells, which provided a useful model to study the function of the CYP3A4 enzyme [100]. The authors of the study suggested that a high concentration of neo-clerodanes in the crude extract or synergistic effect of the neo-clerodanes with one another or with other phytochemicals present in the plant might produce hepatotoxic effects. Other lines of evidence implicate immune-mediated pathways in initiating liver injury. In other cases, autoantibodies were present [142,144].

4. Conclusions

Seven taxa belonging to the genus Teucrium, native to the Kurdistan Region, Iraq (Table 1), are used for the preparation of remedies for various diseases in the local traditional medicine, as well as in other countries. In Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 1 and Table 2 of this first ethnopharmacological review dedicated to this group of Kurdish plants, we collected the structures of more than 190 representative specialized components of essential oils and extracts, their traditional uses and their various biological activities reported in the literature. In general, the components of most essential oils, mainly mono- and sesquiterpenoids, were determined, whereas non-volatile metabolites have been less investigated, except those from T. polium and T. chamaedrys. However, a great number of novel and bioactive furanoid neo-clerodane and abeo-abietane diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, triterpenoids, steroids, flavonoids, iridoids, phenylethanoids and other aromatic compounds were isolated. Thus, Teucrium taxa belonging to the Iraqi Kurdistan flora can be considered rich sources of compounds with the potential to develop efficacious therapeutic agents. This finding should stimulate further scientific investigations, as well as the implementation of measures to preserve the rich biodiversity of Kurdistan.

However, several studies have indicated the contemporaneous presence of substances with opposite biological effects, for example, antioxidant polyphenols and hepatotoxic neo-clerodanes. This finding should be seriously considered and an accurate screening for toxic substances should be compulsory, especially if the plants are used as raw materials for botanicals.

This example clearly indicates that better public and physician awareness through health education, early recognition and management of herbal toxicity and tighter regulation of complementary/alternative medicine systems are required to minimize the dangers of herbal product use [141]. Moreover, in vivo assays and evidence-based clinical trials are needed to confirm the therapeutic properties of bioactive compounds. Moreover, SAR and QSAR approaches on active metabolites should be implemented in further studies.

Based on the findings outlined in this review, we intend to further in-depth investigate the phytochemistry and biological activities of Teucrium species used in Iraqi Kurdistan, especially the poorly known species T. melissoides, T. parviflorum and T. rigidum. In this context, we consider it particularly important to exclude the presence of hepatotoxic neo-clerodane diterpenoids, considering the wide uses of Teucrium plants in the Kurdish traditional medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V. and F.H.S.H.; data curation and supervision, F.O.A., A.S.S. and G.G.; writing- original draft preparation, Z.M.T. and F.O.A.; writing-review and editing, G.V., G.G. and Z.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Abdul Hussain Al Khayyat and Abdullah S. A., from the University of Salahaddin-Hawler/Iraq, for botanical information. We are also grateful to the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) for supporting open access publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mathur, S.; Hoskins, C. Drug development: Lessons from nature. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 6, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mati, E.; de Boer, H. Ethnobotany and trade of medicinal plants in the Qaysari Market, Kurdish Autonomous Region, Iraq. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusotti, G.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Dentamaro, A.; Gilardoni, G.; Tosi, S.; Grisoli, P.; Cesare Dacarro, C.; Guglielminetti, M.L.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Caccialanza, G.; et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the volatile fractions from leaves and flowers of the wild Iraqi Kurdish plant Prangos peucedanifolia Fenzl. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.A.; Askari, A.A. Ethnobotany of the Hawraman region of Kurdistan Iraq. Harv. Pap. Bot. 2015, 20, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.A.; Al-Habib, O.A.M.; Bugonl, S.; Clericuzio, M.; Vidari, G. A new ursane-type triterpenoid and other constituents from the leaves of Crataegus azarolus var. aronia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1637–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.I.M.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Sardar, A.S.; Vidari, G. Phytochemistry and Ethnopharmacology of Some Medicinal Plants Used in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Abdullah, S.S.; Vita-Finzi, P.; Vidari, G. Phytochemistry and Ethnopharmacology of Medicinal Plants Used on Safeen Mountain in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1923–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, H.M. Ethnopharmacobotanical study on the medicinal plants used by herbalists in Sulaymaniyah Province, Kurdistan, Iraq. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.F.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Zanoni, G.; Vidari, G. The main constituents of Tulipa systola Stapf. roots and flowers; their antioxidant activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2001–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hussain, F.H.; Clericuzio, M.; Porta, A.; Vidari, G. A new iriDOId dimer and other constituents from the traditional Kurdish plant Pterocephalus nestorianus Nábělek. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.I.M.; Amin, A.A.; Tosi, S.; Mellerio, G.G.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Picco, A.M.; Vidari, G. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oils from flowers, leaves, rhizomes, and bulbs of the wild Iraqi Kurdish plant Iris persica. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Mannucci, B.; Lappano, R.; Tosi, S.; Maggiolini, M.; Vidari, G. Composition, antifungal and antiproliferative activities of the hydrodistilled oils from leaves and flower heads of Pterocephalus nestorianus Nábělek. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hussain, F.S.H.; Cucca, L.; Vidari, G. Phytochemical investigation and antioxidant effects of different solvent extracts of Pterocephalus nestorianus Nab. growing in Kurdistan Region-Iraq. SJUOZ 2018, 6, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.I.M.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Maggiolini, M.; Vidari, G. Bioactive constituents from the traditional Kurdish plant Iris persica. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1934578X1801300907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheder, D.A.; Al-Habib, O.A.M.; Gilardoni, G.; Vidari, G. Components of volatile fractions from Eucalyptus camaldulensis leaves from Iraqi-Kurdistan and their potent spasmolytic effects. Molecules 2020, 25, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hi, M.A.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Gilardoni, G.; Thu, Z.M.; Clericuzio, M.; Vidari, G. Phytochemistry of Verbascum Species Growing in Iraqi Kurdistan and Bioactive Iridoids from the Flowers of Verbascum calvum. Plants 2020, 9, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.I.M.; Hussain, F.H.S.; Najmaldin, S.K.; Thu, Z.M.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Gilardoni, G.; Vidari, G. Phytochemistry and biological activities of Iris species growing in Iraqi Kurdistan and phenolic constituents of the traditional plant Iris postii. Molecules 2021, 26, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.V.; Ismail, R.R.; Diyya, A.S.M.; Ghafour, D.D.; Jalal, L.K. Antibacterial effects of the organic crude extracts of freshwater algae of Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. J. Med. Plant Res. 2021, 15, 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, F.O.; Hamahameen, B.A.; Dastan, D. Chemical constituents of the volatile and nonvolatile, cytotoxic and free radical scavenging activities of medicinal plant: Ranunculus millefoliatus and Acanthus dioscoridis. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. World Flora Online. An Online Flora of All Known Plants. 2021. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Govaerts, R.A.; Paton, A.; Harvey, Y.; Navarro, T.; Del Rosario Garcia Pena, M. World Checklist of Lamiaceae; The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, T. Systematics and Biogeography of the Genus Teucrium (Lamiaceae). In Teucrium Species: Biology and Applications; Stanković, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, D.; Stanković, M. Application of Teucrium Species: Current Challenges and Further Perspectives. In Teucrium Species: Biology and Applications; Stanković, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarić, S.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Ethnobotanical Features of Teucrium Species. In Teucrium Species: Biology and Applications; Stanković, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubelen, A.; Topçu, G.; Sõnmez, U. Chemical and biological evaluation of genus Teucrium. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Vol. 23 (Bioactive Natural Products, Part D); Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 591–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano Candela, R.; Rosselli, S.; Bruno, M.; Fontana, G. A review of the phytochemistry, traditional uses and biological activities of the essential oils of genus Teucrium. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 432–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, M.S.; Zlatic, N.-M. Ethnobotany of Teucrium Species; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Yang, J.L.; Venditti, A.; Mahdi Moridi Farimani, M.M. A review of the phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology and biological activities of Teucrium genus (Germander). Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, A. Wild Plants of Iraq with Their Distribution; Iraq Ministry of Agriculture: Baghdad, Iraq, 1968.

- Ridda, T.J.; Daood, W.H. Geographical Distribution of Wild Vascular Plants of Iraq; National Herbarium of Iraq: Baghdad, Iraq, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Avula, B.; Manyam, R.B.; Bedir, E.; Khan, I.A. HPLC analysis of neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium chamaedrys. Die Pharmazie 2003, 58, 494–496. [Google Scholar]

- Frezza, C.; Venditti, A.; Matrone, G.; Serafini, I.; Foddai, S.; Bianco, A.; Serafini, M. Iridoid glycosides and polyphenolic compounds from Teucrium chamaedrys L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, T.A.K.; Veitch, N.C.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Direct inhibition of calcineurin by caffeoyl phenylethanoid glycosides from Teucrium chamaedrys and Nepeta cataria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 1306–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özel, M.Z.; Göğüş, F.; Lewis, A.C. Determination of Teucrium chamaedrys volatiles by using direct thermal desorption-comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1114, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrey, D.; Vial, T.; Pauwels, A.; Castot, A.; Biour, M.; David, M.; Michel, H. Hepatitis after germander (Teucrium chamaedrys) administration: Another instance of herbal medicine hepatotoxicity. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 117, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djabou, N.; Lorenzi, V.; Guinoiseau, E.; Andreani, S.; Giuliani, M.C.; Desjobert, J.M.; Bolla, J.M.; Costa, J.; Berti, L.; Luciani, A.; et al. Phytochemical composition of Corsican Teucrium essential oils and antibacterial activity against foodborne or toxi-infectious pathogens. Food Control 2013, 30, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, L.; Benedec, D.; Hanganu, D.; Damian, G.; Csillag, I.; Sevastre, B.; Mot, A.C.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Tilea, I. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities and phenolic profile for Hyssopus officinalis, Ocimum basilicum and Teucrium chamaedrys. Molecules 2014, 19, 5490–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacifico, S.; D’Abrosca, B.; Pascarella, M.T.; Letizia, M.; Uzzo, P.; Piscopo, V.; Fiorentino, A. Antioxidant efficacy of iridoid and phenylethanoid glycosides from the medicinal plant Teucrium chamaedrys in cell-free systems. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6173–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Esposito, A.; Izzo, A.; Pascarella, M.T.; D’Angelo, G.; Monaco, P. Potential allelopathic effect of neo-clerodane diterpenes from Teucrium chamaedrys (L.) on stenomediterranean and weed cosmopolitan species. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2009, 37, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakov, P.Y.; Papanov, G.Y. Teuchamaedrin C, a neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Teucrium chamaedrys. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savona, G.; García-Alvarezt, M.C.; Rodríguez, B. Dihydroteugin, a neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Teucrium chamaedrys. Phytochemistry 1982, 21, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekehal, M.; Pessayre, D.; Lereau, J.M.; Moulis, C.; Fourasté, I.; Fau, D. Hepatotoxicity of the herbal medicine germander: Metabolic activation of its furano diterpenoids by cytochrome P450 3A depletes cytoskeleton-associated protein thiols and forms plasma membrane blebs in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 1996, 24, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmastas, M.; Erenler, R.; Isnac, B.; Aksit, H.; Sen, O.; Genc, N.; Demirtas, I. Isolation and identification of a new neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Teucrium chamaedrys L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.-C.; Barluenga, J.; Pascual, C.; Rodríguez, B.; Savona, G.; Piozzi, F. Neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium chamaedrys: The identity of teucrin B with dihydroteugin. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 2960–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, P.R.; Slavoff, S.A.; Grundel, E.; White, K.D.; Mazzola, E.; Koblenz, D.; Rader, J.I. Isolation and characterisation of selected germander diterpenoids from authenticated Teucrium chamaedrys and T. canadense by HPLC, HPLC-MS and NMR. Phytochem. Anal. 2006, 17, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gadea, F.; Pascual, C.; Rodríguez, B.; Savona, G. 6-epiteucrin A, a neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Teucrium chamaedrys. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Piccolella, S.; Fiorentino, A.; Pepi, F.; D’Abrosca, B.; Monaco, P. A tandem mass spectrometric investigation of the low-energy collision-activated fragmentation of neo-clerodane diterpenes. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 1543–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanov, G.Y.; Malakov, P.Y. Furanoid diterpenes in the bitter fraction of Teucrium chamaedrys L. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B 1980, 35, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinbol’d, A.M.; Popa, D.P. Minor diterpenoids of Teucrium chamaedrys. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1974, 10, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubelen, A.; Topcu, G.; Kaya, Ü. Steroidal compounds from Teucrium chamaedrys subsp. chamaedrys. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.P.; Reinbol’d, A.M. Bitter substances from Teucrium chamaedrys. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1972, 8, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedir, E.; Manyam, R.; Khan, I.A. Neo-clerodane diterpenoids and phenylethanoid glycosides from Teucrium chamaedrys L. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lee, C.S. Total synthesis of (−)-teucvidin. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2886–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzi, S.A.; McMurtry, R.J.; Nelson, S.D. Hepatotoxicity of germander (Teucrium chamaedrys L.) and one of its onstituent neoclerodane diterpenes teucrin A in the mouse. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994, 7, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalis, I.; Bedir, E.; Wright, A.D.; Sticher, O. Neoclerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium chamaedrys subsp. syspirense. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguren, L.; Perales, A.; Fayos, J.; Rodriquez, B.; Savona, G.; Piozzi, F. New neoclerodane diterpenoid containing an oxetane ring isolated from Teucrium chamaedrys. X-ray structure determination. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 4157–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Ricci, A.; Pacifico, S.; Piccolella, S.; Monaco, P. Structure determination of chamaedryosides A-C, three novel nor-neo-clerodane glucosides from Teucrium chamaedrys, by NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2009, 47, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geçibesler, I.H.; Demirtas, I.; Koldaş, S.; Behçet, L.; Gül, F.; Altun, M. Bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds with antiproliferative activity from Teucrium chamaedrys L. subsp. sinuatum (Celak.) Rech. F. Progr. Nutr. 2019, 21, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Williams, C.A.; Gil, M.I. A chemotaxonomic study of flavonoids from European Teucrium species. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognoni, F.; Iannello, C.; Mandrone, M.; Scognamiglio, M.; Fiorentino, A.; Giovannini, P.P.; Poli, F. Elicited Teucrium chamaedrys cell cultures produce high amounts of teucrioside, but not the hepatotoxic neo-clerodane diterpenoids. Phytochemistry 2012, 81, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.A.; Lahloub, M.F.; Anklin, C.; Schulten, H.R.; Sticher, O. Teucrioside, a phenylpropanoid glycoside from Teucrium chamaedrys. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muselli, A.; Desjobert, J.-M.; Paolini, J.; Bernardini, A.-F.; Costa, J.; Rosa, A.; Dessi, M.A. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Teucrium chamaedrys L. from Corsica and Sardinia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezić, N.; Vuko, E.; Dunkić, V.; Ruščić, M.; Blažević, I.; Burčul, F. Antiphytoviral activity of sesquiterpene-rich essential oils from four Croatian Teucrium species. Molecules 2011, 16, 8119–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morteza-Semnani, K.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Rostami, B. The essential oil composition of Teucrium chamaedrys L. from Iran. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 544–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Hyseni, L.; Bajrami, A.; Mustafa, G.; Quave, C.L.; Nebija, D. Phytochemical study of eight medicinal plants of the Lamiaceae family traditionally used as tea in the Sharri Mountains region of the Balkans. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 4182064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kovacevic, N.N.; Lakusic, B.S.; Ristic, M.S. Composition of the essential oils of seven Teucrium species from Serbia and Montenegro. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2001, 13, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, E.; Yazgın, A.; Hayta, S.; Cakılcıoglu, U. Composition of the essential oil of Teucrium chamaedrys L. (Lamiaceae) from Turkey. J. Med. Plant Res. 2010, 4, 2588–2590. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, L.; Mirza, M.; Shahmir, F. Essential oil of Teucrium melissoides Boiss. et Hausskn. ex Boiss. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2002, 14, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajabnoor, M.A.; Al-Yahya, M.A.; Tariq, M.; Jayyab, A.A. Antidiabetic activity of Teucrium oliverianum. Fitoterapia 1984, 55, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya, M.A.; El-Feraly, F.S.; Chuck Dunbar, D.; Muhammad, I. Neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium oliverianum and structure revision of teucrolin E. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Omar, A.A.; Perales, A.; Piozzi, F.; Rodríguez, B.; Savona, G.; Torre, M.C.D.l. Neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium oliverianum. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, M.A.; Muhammad, I.; Mirza, H.H.; El-Feraly, F.S.; McPhail, A.T. Neoclerodane diterpenoids and their artifacts from Teucrium oliverianum. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahat, A.A.; Alsaid, M.S.; Khan, J.A.; Higgins, M.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Chemical constituents and NAD(P)H:Quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) inducer activity of Teucrium oliverianum Ging. ex Benth. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- De La Torre, M.C.; Bruno, M.; Piozzi, F.; Savona, G.; Rodríguez, B.; Omar, A.A. Teucrolivins D–F, neo-clerodane derivatives from Teucrium oliverianum. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, M.Ş.; Sarı, A. Plants used in traditional treatment against hemorrhoids in Turkey. Marmara Pharm. J. 2018, 22, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, S.; Çelik, S.; Türkoğlu, I.; Çakılcıoğlu, U.; Bahsi, M. Determination of the antioxidant properties of ethanol and water extracts from different parts of Teucrium parviflorum Schreber. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 6797–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, E.; Hayta, S.; Yazgin, A.; Dogan, G. Composition of the essential oil of Teucrium parviflorum L. (Lamiaceae) from Turkey. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 3457–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Ageel, A.M.; al-Yahya, M.A.; Mossa, J.S.; al-Said, M.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of Teucrium polium. Int. J. Tissue React. 1989, 11, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bahramikia, S.; Yazdanparast, R. Phytochemistry and medicinal properties of Teucrium polium L. (Lamiaceae). Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedir, E.; Tasdemir, D.; Çalis, I.; Zerbe, O.; Otto, S. Neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium polium. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, A. 7-epi-Eudesmanes from Teucrium polium. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubuncic, P.; Dakwar, S.; Portnaya, I.; Cogan, U.; Azaizeh, H.; Bomzon, A. Aqueous extracts of Teucrium polium possess remarkable antioxidant activity in vitro. Evid.-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2006, 3, 436479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Snoussi, M.; Anouar, E.H.; Alreshidi, M.; Veettil, V.N.; Elkahoui, S.; Adnan, M.; Patel, M.; Kadri, A.; Aouadi, K.; et al. HR-LCMS-based metabolite profiling, antioxidant, and anticancer properties of Teucrium polium L. methanolic extract: Computational and in vitro study. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, A.; Yazdanparast, R. Inhibitory effects of ethyl acetate extract of Teucrium polium on in vitro protein glycoxidation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marino, S.; Festa, C.; Zollo, F.; Incollingo, F.; Raimo, G.; Evangelista, G.; Iorizzi, M. Antioxidant activity of phenolic and phenylethanoid glycosides from Teucrium polium L. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharififar, F.; Dehghn-Nudeh, G.; Mirtajaldini, M. Major flavonoids with antioxidant activity from Teucrium polium L. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, V.; Gomez-Caravaca, A.M.; Exarchou, V.; Gerothanassis, I.P.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Gutiérrez, A.F. Exploring the antioxidant potential of Teucrium polium extracts by HPLC–SPE–NMR and on-line radical-scavenging activity detection. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasri, W.A.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Mechref, Y.; Paré, P.W. Structure-antioxidant and anti-tumor activity of Teucrium polium phytochemicals. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 15, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.A.; Zohari, F.; Sadeghi, H. Antioxidant and protective effects of major flavonoids from Teucrium polium on β-cell destruction in a model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Pacifico, S.; Scognamiglio, M.; D’Angelo, G.; Monaco, P. abeo-Abietanes from Teucrium polium roots as protective factors against oxidative stress. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 8530–8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacifico, S.; D’Abrosca, B.; Scognamiglio, M.; D’Angelo, G.; Gallicchio, M.; Galasso, S.; Monaco, P.; Fiorentino, A. NMR-based metabolic profiling and in vitro antioxidant and hepatotoxic assessment of partially purified fractions from Golden germander (Teucrium polium L.) methanolic extract. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1957–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Abrosca, B.; Pacifico, S.; Scognamiglio, M.; D’Angelo, G.; Galasso, S.; Monaco, P.; Fiorentino, A. A new acylated flavone glycoside with antioxidant and radical scavenging activities from Teucrium polium leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autore, G.; Capasso, F.; De Fusco, R.; Fasulo, M.P.; Lembo, M.; Mascolo, N.; Menghini, A. Antipyretic and antibacterial actions of Teucrium polium (L.). Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1984, 16, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabpour, E.; Motamedi, H.; Nejad, S.M.S. Antimicrobial properties of Teucrium polium against some clinical pathogens. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2010, 3, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasri, W.A.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Aziz, M.; Koksal, E.; Amor, W.; Mechref, Y.; Hamood, A.N.; Cordes, D.B.; Paré, P.W. Biofilm blocking sesquiterpenes from Teucrium polium. Phytochemistry 2014, 103, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BozovElmasri, W.A.; Yang, T.; Tran, P.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Hamood, A.N.; Mechref, Y.; Paré, P.W. Teucrium polium phenylethanol and iridoid glycoside characterization and flavonoid inhibition of biofilm-forming Staphylococcus aureus. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oganesyan, G.B.; Galstyan, A.M.; Mnatsakanyan, V.A.; Shashkov, A.S.; Agababyan, P.V. Phenylpropanoid glycosides of Teucrium polium. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1991, 27, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasri, W.A.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Mechref, Y.; Paré, P.W. Cytotoxic saponin poliusaposide from Teucrium polium. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27126–27133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi-Mahani, S.N.; Rezazadeh-Kermani, M.; Mehrabani, M.; Nakhaee, N. Cytotoxic effects of Teucrium polium. on some established cell lines. Pharm. Biol. 2007, 45, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; D’Abrosca, B.; Pacifico, S.; Scognamiglio, M.; D’Angelo, G.; Gallicchio, M.; Chambery, A.; Monaco, P. Structure elucidation and hepatotoxicity evaluation against HepG2 human cells of neo-clerodane diterpenes from Teucrium polium L. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twaij, H.A.A.; Albadr, A.A.; Abul-Khail, A. Anti-ulcer activity of Teucrium polium. Int. J. Crude Drug Res. 1987, 25, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Karimpour, H.; Monsef-Esfehani, H.R. Antinociceptive effects of Teucrium polium L. total extract and essential oil in mouse writhing test. Pharmacol. Res. 2003, 48, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Maggio, A.M.; Piozzi, F.; Puech, S.; Rosselli, S.; Simmonds, M.S.J. Neoclerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium polium subsp. polium and their antifeedant activity. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, M.N.; Elayan, H.H.; Salhab, A.S. Hypoglycemic effects of Teucrium polium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1988, 24, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.A.; Yazdanparast, R. Hypoglycaemic effect of Teucrium polium: Studies with rat pancreatic islets. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasekh, H.R.; Khoshnood-Mansourkhani, M.J.; Kamalinejad, M. Hypolipidemic effects of Teucrium polium in rats. Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević-Djordjević, O.; Radović Jakovljević, M.; Marković, A.; Stanković, M.; Ćirić, A.; Marinković, D.; Grujičić, D. Polyphenolic contents of Teucrium polium L. and Teucrium scordium L. associated with their protective effects against MMC-induced chromosomal damage in cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Turk. J. Biol. 2018, 42, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakov, P.Y.; Papanov, G.Y.; Ziesche, J. Teupolin III, a furanoid diterpene from Teucrium polium. Phytochemistry 1982, 21, 2597–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakov, P.Y.; Papanov, G.Y.; Mollov, N.M. Furanoid diterpenes in the bitter fraction of Teucrium polium L. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B 1979, 34, 1570–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakov, P.Y.; Papanov, G.Y. Furanoid diterpenes from Teucrium polium. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 2791–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieskorn, C.H.; Pfeuffer, T. Labiate bitter principles: Picropoline and similar diterpenoids from poleigamander. Chem. Ber. 1967, 100, 1998–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galstyan, A.M.; Shashkov, A.S.; Oganesyan, G.B.; Mnatsakanyan, V.A.; Serebryakov, É.P. Structures of two new diterpenoids from Teucrium polium. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1992, 28, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakov, P.Y.; Boneva, I.M.; Papanov, G.Y.; Spassov, S.L. Teulamifin B, a neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Teucrium lamiifolium and T. polium. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 1141–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, A.; Frezza, C.; Trancanella, E.; Zadeh, S.M.M.; Foddai, S.; Sciubba, F.; Delfini, M.; Serafini, M.; Bianco, A. A new natural neo-clerodane from Teucrium polium L. collected in Northern Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, A.M.; Hammouda, F.M.; Rimpler, H.; Kamel, A. Iridoids and flavonoids of Teucrium polium herb1. Planta Med. 1986, 52, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verykokidou-Vitsaropoulou, E.; Vajias, C. Methylated flavones from Teucrium polium. Planta Med. 1986, 52, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shalabi, E.; Alkhaldi, M.; Sunoqrot, S. Development and evaluation of polymeric nanocapsules for cirsiliol isolated from Jordanian Teucrium polium L. as a potential anticancer nanomedicine. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashty, S.A.; Gamal El-Din, E.M.; Saleh, N.A.M. The flavonoid chemosystematics of two Teucrium species from Southern Sinai, Egypt. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1999, 27, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicha, S.F.; Barrek, S.; Skanji, T.; Zarrouk, H.; Ghrabi, Z.G. Fatty acid, tocopherol, and sterol content of three Teucrium species from Tunisia. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2009, 45, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, F.; Cerri, R.; Morrica, P.; Senatore, F. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of an alcoholic extract of Teucrium polium L. Boll. Soc. Ital. Bio. Sper. 1983, 59, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Vokou, D.; Bessiere, J.-M. Volatile constituents of Teucrium polium. J. Nat. Prod. 1985, 48, 498–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassel, G.M.; Ahmed, S.S. Essential oil of Teucrium polium L. Die Pharmazie 1974, 29, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sayyad, R.; Farahmandfar, R. Influence of Teucrium polium L. essential oil on the oxidative stability of canola oil during storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3073–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburjai, T.; Hudaib, M.; Cavrini, V. Composition of the essential oil from Jordanian germander (Teucrium polium L.). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikani, M.H.; Goodarznia, I.; Mirza, M. Comparison between the essential oil and supercritical carbon dioxide extract of Teucrium polium L. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1999, 11, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzeghabaie, A.; Asgarpanah, J. Essential oil composition of Teucrium polium L. fruits. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2016, 28, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Jamalpoor, S.; Shirzadi, M.H. Variability in essential oil of Teucrium polium L. of different latitudinal populations. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 54, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahbakhsh, J.; Najafian, S.; Hosseinifarahi, M.; Gholipour, S. The effect of time and temperature on shelf life of essential oil composition of Teucrium polium L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, A.; Duru, M.E.; Harmandar, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Passannanti, S. Volatile constituents of Teucrium polium L. from Turkey. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1998, 10, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashnagar, A.; Naseri, N.G.; Foroozanfar, S. Isolation and identification of the major chemical components found in the upper parts of Teucrium polium plants grown in Khuzestan province of Iran. Chin. J. Chem. 2007, 25, 1171–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozov, P.I.; Penchev, P.N.; Girova, T.D.; Gochev, V.K. Diterpenoid constituents of Teucrium scordium L. subsp. scordioides (Shreb.) Maire Et Petitmengin. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20959525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.; Dekić, M.; Joksović, M.; Vukićević, R. Chemotaxonomy of Serbian Teucrium species inferred from essential oil chemical composition: The case of Teucrium scordium L. ssp. scordioides. Chem. Biodivers. 2012, 9, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano Candela, R.; Ilardi, V.; Badalamenti, N.; Bruno, M.; Rosselli, S.; Maggi, F. Essential oil compositions of Teucrium fruticans, T. scordium subsp. scordioides and T. siculum growing in Sicily and Malta. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 3460–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piozzi, F.; Bruno, M.; Rosselli, S.; Maggio, A. Advances on the chemistry of furano-diterpenoids from Teucrium genus. Heterocycles 2005, 65, 1221–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.S.J.; Blaney, W.M.; Ley, S.V.; Savona, G.; Bruno, M.; Rodriguez, B. The antifeedant activity of clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1069–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezza, C.; de Vita, D.; Toniolo, C.; Ventrone, A.; Tomassini, L.; Foddai, S.; Nicoletti, M.; Guiso, M.; Bianco, A.; Serafini, M. Harpagide: Occurrence in plants and biological activities—A review. Fitoterapia 2020, 147, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, M.C.; Martinotti, E.; Catalano, S.; Flamini, G.; Morelli, I.; Pagni, A.M. Vasoconstrictor activity of 8-O-acetylharpagide from Ajuga reptans. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J.M.; Maffrand, J.P.; Taoubi, K.; Augereau, J.M.; Fouraste, I.; Gleye, J.; Shi, C.; Hui, N.; Liu, Y.; Ling, M.; et al. Verbascoside isolated from Lantana camara, an inhibitor of protein kinase C. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, J.; Liang, C.; Tian, L.; Shi, C.; Hui, N.; Liu, Y.; Ling, M.; Xin, L.; Wan, M.; et al. Pacifico. Syringa microphylla Diels: A comprehensive review of its phytochemical, pharmacological, pharmacokinetic, and toxicological characteristics and an investigation into its potential health benefits. Phytomedicine 2021, 93, 153770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, E. Prediction of potential cancer-related molecular targets of North African plants constituents using network pharmacology-based analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 238, 111826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeper, J.; Descatoire, V.; Letteron, P.; Moulis, C.; Degott, C.; Dansette, P.; Fau, D.; Pessayre, D. Hepatotoxicity of germander in mice. Gastroenterology 1994, 106, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, S.; Farrell, G.C. Hepatotoxic slimming aids and other herbal hepatotoxins. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckova, A.; Mernaugh, R.L.; Ham, A.-J.L.; Marnett, L.J. Identification of the protein targets of the reactive metabolite of teucrin A in vivo in the rat. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1393–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeros, D.; Kamberoglou, D.; Tzias, V. Acute cholestatic hepatitis caused by Teucrium polium (golden germander) with transient appearance of antimitochondrial antibody. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002, 34, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).