Abstract

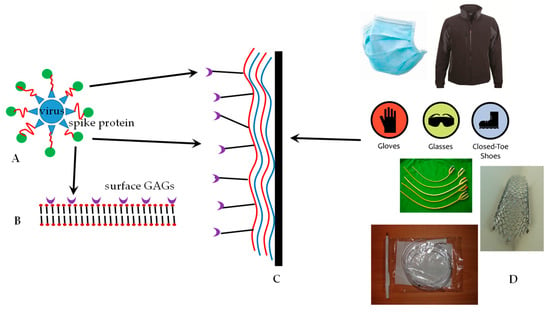

In 2020, the world is being ravaged by the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes a severe respiratory disease, Covid-19. Hundreds of thousands of people have succumbed to the disease. Efforts at curing the disease are aimed at finding a vaccine and/or developing antiviral drugs. Despite these efforts, the WHO warned that the virus might never be eradicated. Countries around the world have instated non-pharmaceutical interventions such as social distancing and wearing of masks in public to curb the spreading of the disease. Antiviral polysaccharides provide the ideal opportunity to combat the pathogen via pharmacotherapeutic applications. However, a layer-by-layer nanocoating approach is also envisioned to coat surfaces to which humans are exposed that could harbor pathogenic coronaviruses. By coating masks, clothing, and work surfaces in wet markets among others, these antiviral polysaccharides can ensure passive prevention of the spreading of the virus. It poses a so-called “eradicate-in-place” measure against the virus. Antiviral polysaccharides also provide a green chemistry pathway to virus eradication since these molecules are primarily of biological origin and can be modified by minimal synthetic approaches. They are biocompatible as well as biodegradable. This surface passivation approach could provide a powerful measure against the spreading of coronaviruses.

1. Introduction

In this paper, the role of a layer-by-layer nanocoating approach to provide a mechanism of prevention of the spreading of the corona- and other viruses is described. The emphasis is placed on passive prevention techniques that may contribute to curbing the spread of the pathogen, rather than active pharmaceutical measures. It must be emphasized that the continued efforts toward vaccination and pharmacotherapeutic measures are essential and should continue. It is suggested that our non-pharmaceutical prophylaxis measures will aid the pharmaceutical measures in a complementary fashion.

The perspective provided here is that several measures can be taken to prevent the spreading of the pathogen and attempt to combat the virus before it even enters the body. Despite our description of external measures against coronaviruses, it still relies significantly on the knowledge gained by renowned researchers who have established and studied vaccination and pharmacotherapeutic interventions against viruses in general.

2. The Cell Entry Mechanism of Encapsulated Viruses

Encapsulated viruses such as the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 viruses comprise of some general surface constituents. The surface envelope or capsule is presented as a lipid bilayer membrane that contains various envelope proteins (E), membrane proteins (M), and an outer layer that presents so-called spike (S) proteins [1]. M and S proteins are generally rich in sugar molecules that form a so-called glycan structure. N- or O-glycosylate moieties are commonly found in the viral S proteins and they can recognize some cell receptors to which the virion can bind [2,3]. These spike proteins facilitate virion entry into host cells. Encapsulated viruses such as the coronaviruses present approximately 200 of these spiky structures [4]. Spike proteins are comprised of glycoproteins, proteins that also contain polysaccharide or oligosaccharide moieties otherwise known as glycans [5,6,7].

The glycoproteins have a variety of functions that maintain the virion structure and properties such as water solubility, creation of diffusion barriers, and antiadhesive actions among others [6]. In addition to the intrinsic functions that glycoproteins afford to the maintenance of the virion structure, they also act as a structure that recognizes glycan-binding proteins presented on the membranes of potential host cells [1]. The viral glycans may be recognized by bacterial, fungal, and parasite-associated glycan-binding proteins. However, viruses are also recognized by host cells via the same mechanism. It is this form of intercellular recognition interactions that prove vital to effect the virus entry into host cells in which the virus could replicate [7].

A detailed description of the spike glycoproteins of SARS-CoV-2 reported that two binding subunits can be distinguished. These subunits become active when the two units are cleaved by host cell proteases on the host cell membrane. Subunit, S1 is responsible for binding to the host cell membrane and subunit, S2 is responsible for fusion of the virion and host cell membranes. The S1 unit is the factor that makes various coronaviruses specific toward a certain host [8]. Pulmonary angiotensin-converting-enzyme 2 (ACE-2) in humans exhibit the appropriate receptor, a specific sequence of amino acid residues [9], towards S1 and partly explains the effective spread of the coronaviruses via droplets in the atmosphere [10].

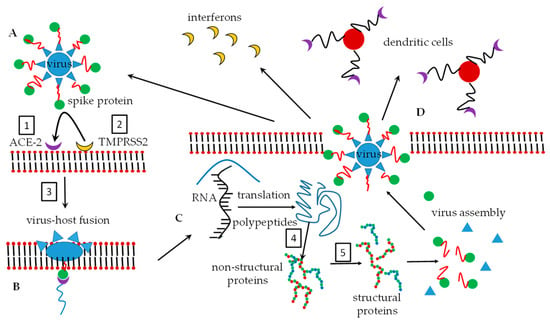

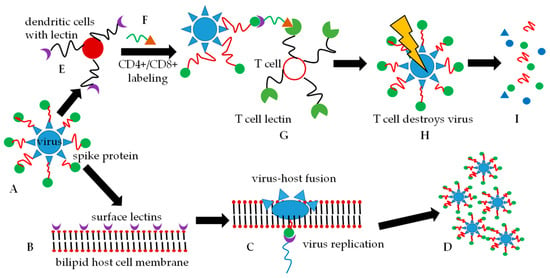

As part of the human host immune responses, the glycans of the coronavirus spike protein subunits are recognized by dendritic cells [11] in the blood which binds to the glycan and subsequently expresses CD4+ and CD8+ glycopeptides. These glycopeptides label the spike protein and this labeled protein is then presented to T-cells [12]. T-cells subsequently recognize the labels, phagocytose these antigen-marked viruses, and degrade them. It has been found that the glycan-binding proteins, also known as lectins [5], can impart broad-spectrum binding properties against HIV-1, SARS-CoV, and human cytomegalovirus. The lectin which is capable of showing broad interaction via oligomannosyl antigens is known as lectin GNA (Galanthus nivalis agglutinin). The N-oligomannosyl cores are embedded in N-glycans which are commonly expressed on the surface of numerous viral pathogens [13]. Once the lectin binds to the glycan, the virus structure may undergo conformational changes that result in the fusion of the virus and host to facilitate virus entry. S-proteins are specifically responsible for host cell entry by coronaviruses [14]. Figure 1 depicts a simplified entry mechanism of the viruses into host cells.

Figure 1.

Two simplified routes of the fate of an encapsulated virus are shown. Either route (A–D) or route (A–I) can be followed. (A). The virus with spike proteins comprising of N-glycan moieties on the protein (red and green) is presented. (B). A potential host cell presents glycan-recognizing lectins on its bilipid membrane surface. (C). The virus glycan array binds to the host cell lectins and membrane fusion is initiated and after phagocytosis, virus replication follows. (D). Host cell destruction takes place with the subsequent release of new virus particles. (E). The virus is intercepted by dendritic cells before it can interact with the host cell membrane. The dendritic cells label the virus with cytokines CD4+/CD8+ (green and orange symbols), and (G). presents the cytokine-labeled virus to T-cells. (H). T-cells recognize the CD4+/CD8+ labels and phagocytose the virus that is destroyed in the T-cell lysosomes. (I). Only inactive, non-pathogenic viral degradation products remain.

5. What Can LbL Nanocoating Contribute to the Prevention of Infectious Disease?

5.1. The Process of Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Nanocoating

LbL self-assembly of polyelectrolytes took its origin in the 1990s [78]. Poly(styrene-4-sulfonate), PSS, was one of the first polyanions employed for LbL self-assembly and remains widely utilized today. As polycation, an ammonium-containing polymer, poly(N,N-dimethylallylamine), PDDA, was successfully employed to create a multilayer structure comprising of alternating polyanion and -cation layers [79].

A series of proteins were also successfully employed as polycations namely cytochrome c, lysozyme, histone f3, myoglobin, and hemoglobin. By adjustment of the pH of the medium, amylase, glucose oxidase, and catalase were employed as polyanions [80]. DNA was also employed successfully as a polyelectrolyte for LL self-assembly [81].

LbL coating has also been employed to modify inorganic surfaces. Although many applications for these surface modifications are possible, only some antimicrobial examples are mentioned. Stainless steel surfaces were primed with an acrylate-based surfactant via electrografting. Subsequently, PSS and PDDA layers were coated in an alternating fashion. Lastly, a layer of chitosan was coated as an antibacterial layer against E. coli and S. aureus [82]. Silicone-based intraocular lenses (IOL) are commonly employed to replace the natural eye lens when it is damaged. The IOL can, however, allow adhesion of many kinds of bacteria and lead to post-operative infections with catastrophic effects in some patients. LbL nanocoating of the lenses with hyaluronic and chitosan had significant anti-adhesion and bactericidal effects that reduced the risk of postoperative infections [83,84].

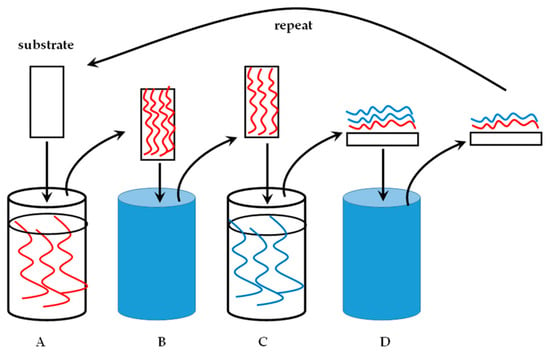

The technique of LbL nanocoating is uncomplicated and requires relatively low concentrations of the polyelectrolytes to produce an efficient coat, often in the low nanometer range. A substrate for coating is required, a polycation and separate polyanion solution, and clean water as the washing liquid. Figure 3 illustrates the technique. Numerous polysaccharides, especially GAGs, are charged polyelectrolytes and the next section will elaborate on this.

Figure 3.

A substrate undergoing layer-by-layer (LbL) nanocoating. (A). Polyelectrolyte solution with a specified charge in a dipping container. The substrate is immersed in this solution for a predetermined time. (B). The coated substrate is placed in water to wash off the excess, unbound polyelectrolyte solution. (C). The washed, coated substrate is immersed in a polyelectrolyte solution of an opposite charge relative to the first solution. (D). A bilayer of the polycation and -anion is formed. The excess of the second polyelectrolyte (blue) is washed off to produce a substrate with a single bilayer of the polyelectrolytes as a nanocoating. The process is repeated for the desired amount of cycles.

5.2. Employment of Polysaccharides as LbL Materials

In this paper, the focus will fall only on common GAGs and other common polysaccharides such as chitosan. It was also noticed during our literature survey that the GAG, keratan sulfate has not been studied in LbL applications and can most probably be attributed to its production in the cornea, cartilage, and bone tissues which makes it fairly inaccessible. To date, the GAGs and other polysaccharides have not been employed widely in LbL nanocoating to specifically produce antiviral surfaces as is the case for antibacterial or antifungal coatings. Numerous publications have reported on the antibacterial surface application of polysaccharides via an LbL approach [85,86,87,88,89,90]. Table 1 lists some commonly utilized polysaccharides that have been employed in LbL nanocoatings and a non-exhaustive list of recent applications.

Table 1.

Polysaccharides that have been studied in LbL nanocoating applications.

The reader should be able to realize that the LbL technique presents numerous possibilities for the application of polysaccharides as antiviral surfaces. Firstly, the polysaccharides, especially GAGs are abundantly available. Secondly, they can recognize and interact with proteins via a range of intermolecular forces including electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic bonding [112]. Thirdly, the polysaccharides are biological molecules and in the case of LbL applications, need minimal or no modification to perform their intended function. Fourthly, fairly low quantities of material need to be deposited to coat the substrates. Lastly, they are biocompatible, biodegradable, and most renewable sources of material. It is very apt to illustrate the chemical structures of the GAGs and some other selected polysaccharides at this point. Figure 4 shows the structures based on the official IUPAC recommendations [113].

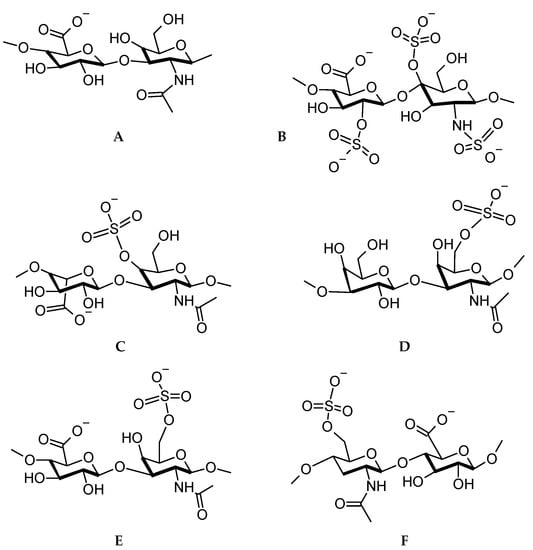

Figure 4.

Disaccharide repeat units for (A) hyaluronic acid, (B) heparan sulfate, (C) dermatan sulfate, (D) keratan sulfate, (E) chondroitin sulfate, (F) heparin.

From Figure 4, it is observed that several anionic functional groups are available for electrostatic interaction, however, numerous hydroxyl and carbonyl groups are also available for hydrogen bonding. The successful application of polysaccharides as antimicrobials now leads us to the possible preventative measures against viruses.

7. Conclusions and Perspective

Humanity is faced with an unprecedented pandemic. It is the best-documented pandemic that the world has seen and this makes it different from previous, historic pandemics. However, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has elicited a concerted, world effort to attempt and curb the effect of the pandemic.

If a cynical view is taken, humanity has to realize that this will not be the last pandemic and that potentially worse pandemics will be seen in the future.

The cusp of antibiotic resistance against many infectious diseases is currently being reached, yet there are even fewer defenses against viral infections. However, nature has provided an abundance of tools, which with human ingenuity and unselfish behavior, can contribute greatly to the prevention of pandemics or at least help to control the spread of these pandemics.

Seen only from an antiviral perspective, many efforts that were launched against other microorganisms can also be effectively applied against viruses. Significant research efforts are focused on the treatment of coronaviruses and these will continue. Of special interest is the employment of antiviral polysaccharide to create virucidal drugs and vaccines. These efforts are aimed primarily at in vivo situations and treatment. It is suggested that many of the in vivo knowledge can be applied to ex vivo, the passive effort against pathogens.

It is known that host cells and viruses interact through glycoprotein and polysaccharide-based interactions. Therefore, the pharmacological effort is attempting to disrupt these interactions or the cellular effects that are seen after the virus and host membrane has indeed merged and the viral mechanism is put into motion.

The human body is a harsh environment and drug delivery and drug development meet these challenges head-on. These include, for example, resistance to absorption of therapeutic agents into the body or degradation of therapeutic agents once they are absorbed into the body.

A clever strategy that is being followed against virus-host cell interaction is to exploit the polysaccharide-lectin recognition system. In vivo efforts have shown that administered polysaccharide-based drugs can serve effectively as decoy binding targets for viruses. Thus, the interaction with membrane-seated viral recognition mechanisms can be circumvented.

Another approach is to induce immunity by presenting polysaccharides or oligosaccharides that represent viral glycoproteins of a specific, or numerous, pathogen(s) to B- and T-cells. These cells will recognize the xenobiotic polysaccharide and activate the immune system cascade and recognize further viruses and eliminate them. If successful, memory cells will be formed and become active when the antigen-antibody, polysaccharide-lectin, interaction occurs in a future infection.

Our suggestion is almost unsophisticated. It is inferred that several surfaces and substrates can be exploited as nanotraps for viruses, outside of the body. It might not be farfetched to suggest that the naturally occurring GAGs will be sufficient to gain positive antiviral results. GAGs are naturally occurring and abundantly available and are suitable to LbL nanocoating in their crude, unrefined state.

It might seem obvious that a layer-by-layer nanocoating strategy will work. However, literature and patent literature surveys have not revealed a significant effort toward antiviral nanocoatings. From the abundant bactericidal reports, it can be deduced that the LbL technique will produce antiviral surfaces. However, we foresee success because surface recognition mechanisms between organisms, hosts, and guests, rely on similar principles and that is protein-polysaccharide interactions.

It is known that numerous polysaccharides have shown antiviral properties and hold significant promise as therapeutic agents. It is suggested to LbL-nanocoat the polysaccharides onto several environmental structures with which humans come into contact daily. We are also optimistic enough to state that researchers in an industry can be successful in this effort since the technique of LbL nanocoating is straightforward, robust, and based on many types of intermolecular forces that can almost guarantee adhesion of materials to a surface of any kind. Numerous examples of LbL nanocoating have been found and described that coat commonly encountered surfaces and produce antibacterial and antifungal actions. Investigation of the antiviral effects of polysaccharide LbL coatings should be investigated and developed. This is an aspect of LbL nanocoating that has not been investigated to a large extent and is a very lucrative option for antiviral research and industrial cooperation. The human, airborne coronavirus are ideal targets for this endeavor. Polysaccharides, in vivo or ex vivo, should be explored for their antiviral applications, especially against coronavirus infections that may be recurring or more frequent in our existence.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the conceptualization and writing of this publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy for financial support of this study.

Acknowledgments

The North-West University of South Africa and the University of Wisconsin-Madison are thanked for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Banerjee, N.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Viral glycoproteins: Biological role and application in diagnosis. Virusdisease 2016, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haan, C.A.; Vennema, H.; Rottier, P.J. Assembly of the coronavirus envelope: Homotypic interactions between the M proteins. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4967–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.M.; Liu, Y.V.; Mu, H.; Taylor, J.K.; Massare, M.; Flyer, D.C.; Glenn, G.M.; Smith, G.E.; Frieman, M.B. Purified coronavirus spike protein nanoparticles induce coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3169–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturman, L.S.; Holmes, K.V. The Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses. In Advances in Virus Research; Lauffer, M.A., Maramorosch, K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 28, pp. 35–112. [Google Scholar]

- Van Breedam, W.; Pohlmann, S.; Favoreel, H.W.; de Groot, R.J.; Nauwynck, H.J. Bitter-sweet symphony: Glycan-lectin interactions in virus biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 598–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varki, A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Bowden, T.A.; Wilson, I.A.; Crispin, M. Exploitation of glycosylation in enveloped virus pathobiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chakraborti, S.; Dimitrov, A.S.; Gramatikoff, K.; Dimitrov, D.S. The SARS-CoV S glycoprotein: Expression and functional characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 312, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathewson, A.C.; Bishop, A.; Yao, Y.; Kemp, F.; Ren, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, X.; Berkhout, B.; van der Hoek, L.; Jones, I.M. Interaction of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus and NL63 coronavirus spike proteins with angiotensin converting enzyme-2. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2741–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells in vivo: A key target for a new vaccine science. Immunity 2008, 29, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padron-Regalado, E. Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2: Lessons from Other Coronavirus Strains. Infect. Dis. 2020, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Tang, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.X. Targeting N-glycan cryptic sugar moieties for broad-spectrum virus neutralization: Progress in identifying conserved molecular targets in viruses of distinct phylogenetic origins. Molecules 2015, 20, 4610–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahony, J.B.; Richardson, S. Molecular diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome: The state of the art. J. Mol. Diagn. 2005, 7, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Ma, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Qin, B.; Shang, S.; Cui, S.; Tan, Z. Binding of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Glycans. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brojakowska, A.; Narula, J.; Shimony, R.; Bander, J. Clinical Implications of SARS-Cov2 Interaction with Renin Angiotensin System. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Yang, N.; Deng, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. Inhibition of SARS Pseudovirus Cell Entry by Lactoferrin Binding to Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodo, F.; Bruijns, S.C.M.; Rodriguez, E.; Li, R.J.E.; Molinaro, A.; Silipo, A.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Garcia-Rivera, D.; Valdes-Balbin, Y.; Verez-Bencomo, V.; et al. Novel ACE2-Independent Carbohydrate-Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Host Lectins and Lung Microbiota. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocke, A.C.; Becher, A.; Knepper, J.; Peter, A.; Holland, G.; Tönnies, M.; Bauer, T.T.; Schneider, P.; Neudecker, J.; Muth, D.; et al. Emerging Human Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Causes Widespread Infection and Alveolar Damage in Human Lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Lee, K.C.; Ng, W.F.; Lai, S.T.; Leung, C.Y.; Chu, C.M.; Hui, P.K.; Mak, K.L.; Lim, W.; et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, J.M.; Smits, S.L.; Haagmans, B.L. Pathogenesis of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Pathol. 2015, 235, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, S.; Ujike, M.; Morikawa, S.; Tashiro, M.; Taguchi, F. Protease-mediated enhancement of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, V.C.C.; Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as an Agent of Emerging and Reemerging Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamming, I.; Timens, W.; Bulthuis, M.; Lely, A.; Navis, G.; van Goor, H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004, 203, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Gao, L.; Shi, H.; Mai, L.; et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut 2020, 69, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, N.; Xie, H.; Lin, S.; Huang, J.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Q. Umifenovir treatment is not associated with improved outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, Y. Camostat mesilate therapy for COVID-19. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurich, A.; Hofmann-Winkler, H.; Gierer, S.; Liepold, T.; Jahn, O.; Pöhlmann, S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarino, A.; Boelaert, J.R.; Cassone, A.; Majori, G.; Cauda, R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: An old drug against today’s diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, C.A.; Rolain, J.-M.; Colson, P.; Raoult, D. New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: What to expect for COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeaud, M.E.; Zores, F. SARS-CoV-2 and the Use of Chloroquine as an Antiviral Treatment. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, J.L.; Tisdale, J.E. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine in the Era of SARS–CoV2: Caution on Their Cardiac Toxicity. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2020, 40, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.L.C.; Ooi, E.E.; Lin, C.-Y.; Tan, H.C.; Ling, A.E.; Lim, B.; Stanton, L.W. Inhibition of SARS coronavirus infection in vitro with clinically approved antiviral drugs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Yang, R.; Yoshinaka, Y.; Amari, S.; Nakano, T.; Cinatl, J.; Rabenau, H.; Doerr, H.W.; Hunsmann, G.; Otaka, A. HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir inhibits replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, G.; Zmora, P.; Gierer, S.; Heurich, A.; Pöhlmann, S. Proteolytic activation of the SARS-coronavirus spike protein: Cutting enzymes at the cutting edge of antiviral research. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell proteases: Critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015, 202, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinatl, J.; Michaelis, M.; Hoever, G.; Preiser, W.; Doerr, H.W. Development of antiviral therapy for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Antivir. Res. 2005, 66, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.O.; Sarafianos, S.G. Antiviral drugs specific for coronaviruses in preclinical development. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 8, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.M.; Monogue, M.L.; Jodlowski, T.Z.; Cutrell, J.B. Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1824–1836. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, H.L.; Apicella, M.A.; Christopher, E.T. Carbohydrate Moieties as Vaccine Candidates. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 705–712. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Quadeer, A.A.; McKay, M.R. Preliminary Identification of Potential Vaccine Targets for the COVID-19 Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Based on SARS-CoV Immunological Studies. Viruses 2020, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Sun, J.; Mao, Z.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.-L.; Li, J. A guideline for homology modeling of the proteins from newly discovered betacoronavirus, 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letko, M.; Marzi, A.; Munster, V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.F.W.; Lau, S.K.P.; To, K.K.W.; Cheng, V.C.C.; Woo, P.C.Y.; Yuen, K.-Y. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: Another Zoonotic Betacoronavirus Causing SARS-Like Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Cottrell, C.A.; Wang, N.; Pallesen, J.; Yassine, H.M.; Turner, H.L.; Corbett, K.S.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S.; Ward, A.B. Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein. Nature 2016, 531, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhao, G.; Lin, Y.; Sui, H.; Chan, C.; Ma, S.; He, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wu, C.; Yuen, K.-Y.; et al. Intranasal Vaccination of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Encoding Receptor-Binding Domain of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Spike Protein Induces Strong Mucosal Immune Responses and Provides Long-Term Protection against SARS-CoV Infection. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 948. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Kou, Z.; Ma, C.; Tao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Yu, F.; Tseng, C.T.; Zhou, Y.; et al. truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: Implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhao, G.; Chan, C.C.S.; Sun, S.; Chen, M.; Liu, Z.; Guo, H.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, B.-J.; et al. Recombinant receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein expressed in mammalian, insect and E. coli cells elicits potent neutralizing antibody and protective immunity. Virology 2009, 393, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, J.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Wrapp, D.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Turner, H.L.; Cottrell, C.A.; Becker, M.M.; Wang, L.; Shi, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieber-Emmons, A.; Monzavi-Karbassi, B.; Kieber-Emmons, T. Antigens: Carbohydrates II. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2020; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson, S.; Bergström, T. Glycoconjugate glycans as viral receptors. Ann. Med. 2005, 37, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, K.; Poluri, K.M. Mechanistic and therapeutic overview of glycosaminoglycans: The unsung heroes of biomolecular signaling. Glycoconj. J. 2016, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovensky, J.; Grand, E.; Uhrig, M.L. Applications of Glycosaminoglycans in the Medical, Veterinary, Pharmaceutical, and Cosmetic Fields. In Industrial Applications of Renewable Biomass Products; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, N.S.; Mancera, R.L. The Structure of Glycosaminoglycans and their Interactions with Proteins. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2008, 72, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imberty, A.; Lortat-Jacob, H.; Pérez, S. Structural view of glycosaminoglycan–protein interactions. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, B.; Magnani, J.L. From carbohydrate leads to glycomimetic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.P.; Sasse, F.; Brönstrup, M.; Diez, J.; Meyerhans, A. Antiviral drug discovery: Broad-spectrum drugs from nature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Pavy, M.; Young, N.; Freeman, C.; Lobigs, M. Antiviral effect of the heparan sulfate mimetic, PI-88, against dengue and encephalitic flaviviruses. Antivir. Res. 2006, 69, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.C.; Davis-Poynter, N.; Nguyen, C.T.H.; Peters, A.A.; Monteith, G.R.; Strounina, E.; Popat, A.; Ross, B.P. GAG mimetic functionalised solid and mesoporous silica nanoparticles as viral entry inhibitors of herpes simplex type 1 and type 2 viruses. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 16192–16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.H.; Harprecht, C.; Stehle, T. The bulky and the sweet: How neutralizing antibodies and glycan receptors compete for virus binding. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 2342–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, B.; Naggi, A.; Torri, G. Chemical Derivatization as a Strategy to Study Structure-Activity Relationships of Glycosaminoglycans. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2002, 28, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Tseligka, E.D.; Jones, S.T.; Tapparel, C. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans and Viral Attachment: True Receptors or Adaptation Bias? Viruses 2019, 11, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycroft-West, C.; Su, D.; Elli, S.; Li, Y.; Guimond, S.; Miller, G.; Turnbull, J.; Yates, E.; Guerrini, M.; Fernig, D.; et al. The 2019 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) surface protein (Spike) S1 Receptor Binding Domain undergoes conformational change upon heparin binding. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycroft-West, C.J.; Su, D.; Li, Y.; Guimond, S.E.; Rudd, T.R.; Elli, S.; Miller, G.; Nunes, Q.M.; Procter, P.; Bisio, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1 Receptor Binding Domain undergoes Conformational Change upon Interaction with Low Molecular Weight Heparins. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycroft-West, C.J.; Su, D.; Li, Y.; Guimond, S.E.; Rudd, T.R.; Elli, S.; Miller, G.; Nunes, Q.M.; Procter, P.; Bisio, A.; et al. Glycosaminoglycans induce conformational change in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1 Receptor Binding Domain. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycroft-West, C.J.; Su, D.; Pagani, I.; Rudd, T.R.; Elli, S.; Guimond, S.E.; Miller, G.; Meneghetti, M.C.Z.; Nader, H.B.; Li, Y.; et al. Heparin inhibits cellular invasion by SARS-CoV-2: Structural dependence of the interaction of the surface protein (spike) S1 receptor binding domain with heparin. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.S. The secret life of ACE2 as a receptor for the SARS virus. Cell 2003, 115, 652–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewska, A.; Zarebski, M.; Nowak, P.; Stozek, K.; Potempa, J.; Pyrc, K. Human coronavirus NL63 utilizes heparan sulfate proteoglycans for attachment to target cells. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 13221–13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Pyrc, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Geier, M.; Berkhout, B.; Pöhlmann, S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7988–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamhankar, M.; Gerhardt, D.M.; Bennett, R.S.; Murphy, N.; Jahrling, P.B.; Patterson, J.L. Heparan sulfate is an important mediator of Ebola virus infection in polarized epithelial cells. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Masante, C.; Buchholz, U.J.; Dutch, R.E. Human metapneumovirus (HMPV) binding and infection are mediated by interactions between the HMPV fusion protein and heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3230–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, A.S.; Sharkey, C.M.; Sanders, D.A. Role of heparan sulfate in entry and exit of Ross River virus glycoprotein-pseudotyped retroviral vectors. Virology 2019, 529, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Tortorici, M.A.; Frenz, B.; Snijder, J.; Li, W.; Rey, F.A.; DiMaio, F.; Bosch, B.-J.; Veesler, D. Glycan shield and epitope masking of a coronavirus spike protein observed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M.; Chandra, V.; Rahman, S.A.; Sehgal, D.; Jameel, S. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans Are Required for Cellular Binding of the Hepatitis E Virus ORF2 Capsid Protein and for Viral Infection. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, S.R.; Warrington, K.H., Jr.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Zolotukhin, S.; Muzyczka, N. Identification of amino acid residues in the capsid proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 that contribute to heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 6995–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulst, M.M.; van Gennip, H.G.; Moormann, R.J. Passage of classical swine fever virus in cultured swine kidney cells selects virus variants that bind to heparan sulfate due to a single amino acid change in envelope protein E(rns). J. Virol. 2000, 74, 9553–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Villiers, M.M.; Otto, D.P.; Strydom, S.J.; Lvov, Y.M. Introduction to nanocoatings produced by layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decher, G.; Hong, J.D.; Schmitt, J. Buildup of ultrathin multilayer films by a self-assembly process: III. Consecutively alternating adsorption of anionic and cationic polyelectrolytes on charged surfaces. Thin Solid Film. 1992, 210–211, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, Y.; Ariga, K.; Ichinose, I.; Kunitake, T. Assembly of Multicomponent Protein Films by Means of Electrostatic Layer-by-Layer Adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6117–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, G.B.; Möhwald, H.; Decher, G.; Lvov, Y.M. Assembly of polyelectrolyte multilayer films by consecutively alternating adsorption of polynucleotides and polycations. Thin Solid Film. 1996, 284–285, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cécius, M.; Jérôme, C. A fully aqueous sustainable process for strongly adhering antimicrobial coatings on stainless steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 70, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.K.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, H. Antiadhesive and antibacterial polysaccharide multilayer as IOL coating for prevention of postoperative infectious endophthalmitis. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017, 66, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkaphan, J.; Banlunara, W.; Palaga, T.; Sombuntham, P.; Wanichwecharungruang, S. Silicone surface with drug nanodepots for medical devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 20188–20196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Petterson, T.; Illergård, J.; Ek, M.; Wågberg, L. Influence of Cellulose Charge on Bacteria Adhesion and Viability to PVAm/CNF/PVAm-Modified Cellulose Model Surfaces. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Tu, H.; Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; Deng, H.; Du, Y. Layer-by-layer immobilization of quaternized carboxymethyl chitosan/organic rectorite and alginate onto nanofibrous mats and their antibacterial application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 121, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, S.; Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Pan, S.; Zhou, X.; Deng, H. Cytotoxicity and antibacterial ability of scaffolds immobilized by polysaccharide/layered silicate composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 1880–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Álvarez, L.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Azua, I.; Benito, V.; Bilbao, A.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. Development of multiactive antibacterial multilayers of hyaluronic acid and chitosan onto poly(ethylene terephthalate). Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lian, X.; Xiong, Y. Surface properties of polyurethanes modified by bioactive polysaccharide-based polyelectrolyte multilayers. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 100, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Long, Y.; Li, Q.L.; Han, S.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.W.; Gao, H. Layer-by-Layer (LBL) Self-Assembled Biohybrid Nanomaterials for Efficient Antibacterial Applications. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 17255–17263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Luo, D.; Zhao, A.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Maitz, M.F.; Yang, P.; Huang, N. pH responsive chitosan and hyaluronic acid layer by layer film for drug delivery applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 135, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, A.; Perez-Alvarez, L.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Pacha Olivenza, M.A.; Garcia Blanco, M.B.; Diaz-Fuentes, M.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. Antibacterial hyaluronic acid/chitosan multilayers onto smooth and micropatterned titanium surfaces. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcsanyi, A.; Varga, N.; Csapo, E. Chitosan-modified hyaluronic acid-based nanosized drug carriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, S.J.; Otto, D.P.; Stieger, N.; Aucamp, M.E.; Liebenberg, W.; de Villiers, M.M. Self-assembled macromolecular nanocoatings to stabilize and control drug release from nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 2014, 256, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Ji, J.; Shen, J. Construction of Polycation-Based Non-Viral DNA Nanoparticles and Polyanion Multilayers via Layer-by-Layer Self-Assembly. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2005, 26, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, B. pH-controlled drug loading and release from biodegradable microcapsules. Nanomedicine 2008, 4, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahlicli, F.Y.; Altinkaya, S.A. Surface modification of polysulfone based hemodialysis membranes with layer by layer self assembly of polyethyleneimine/alginate-heparin: A simple polyelectrolyte blend approach for heparin immobilization. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Yan, J.; Qiu, F.; Song, X.; Fu, G.; Ji, J. Heparin/collagen multilayer as a thromboresistant and endothelial favorable coating for intravascular stent. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2011, 96, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Xiong, X.; Zou, Q.; Ouyang, P.; Burkhardt, C.; Krastev, R. Design of intelligent chitosan/heparin hollow microcapsules for drug delivery. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.V.; Mano, J.F.; Alves, N.M. Nanostructured self-assembled films containing chitosan fabricated at neutral pH. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Yoshida, K.; Takahashi, S.; Anzai, J.-I. pH- and sugar-sensitive layer-by-layer films and microcapsules for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Huang, K.; Chen, L. Polyelectrolyte three layer nanoparticles of chitosan/dextran sulfate/chitosan for dual drug delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 190, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, N.M.; Owen, A.; Rannard, S.; McDonald, T.O. Controlled synthesis of calcium carbonate nanoparticles and stimuli-responsive multi-layered nanocapsules for oral drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 574, 118866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado-Gonzalez, M.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, M.; San Roman, J.; Mijangos, C.; Hernández, R. Local and controlled release of tamoxifen from multi (layer-by-layer) alginate/chitosan complex systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Hung, H.C.; Sun, F.; Bai, T.; Zhang, P.; Nowinski, A.K.; Jiang, S. Achieving low-fouling surfaces with oppositely charged polysaccharides via LBL assembly. Acta Biomater. 2016, 40, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qi, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Lei, J. Self-Assembled Pectin-Conjugated Eight-Arm Polyethylene Glycol–Dihydroartemisinin Nanoparticles for Anticancer Combination Therapy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8097–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, M.; Racovita, S.; Vasiliu, A.L.; Doroftei, F.; Barbu-Mic, C.; Schwarz, S.; Steinbach, C.; Simon, F. Autotemplate Microcapsules of CaCO3/Pectin and Nonstoichiometric Complexes as Sustained Tetracycline Hydrochloride Delivery Carriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37264–37278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ruengruglikit, C.; Wang, Y.W.; Huang, Q. Interfacial interactions of pectin with bovine serum albumin studied by quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring: Effect of ionic strength. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10425–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyomard, A.; Nysten, B.; Muller, G.; Glinel, K. Loading and release of small hydrophobic molecules in multilayer films based on amphiphilic polysaccharides. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2281–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyomard, A.; Muller, G.; Glinel, K. Buildup of Multilayers Based on Amphiphilic Polyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5737–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, F.; Yuan, Q.; Zhu, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, S. Hydrogen-bonded thin films of cellulose ethers and poly(acrylic acid). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 215, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyklema, J.; Deschênes, L. The first step in layer-by-layer deposition: Electrostatics and/or non-electrostatics? Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 168, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, N. IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). Nomenclature of glycoproteins, glycopeptides and peptidoglycans. Recommendations 1985. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986, 159, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafagati, N.; Patanarut, A.; Luchini, A.; Lundberg, L.; Bailey, C.; Petricoin, E., 3rd; Liotta, L.; Narayanan, A.; Lepene, B.; Kehn-Hall, K. The use of Nanotrap particles for biodefense and emerging infectious disease diagnostics. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 71, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, P.; Gao, G.F.; Cheng, S. Carbohydrate-functionalized chitosan fiber for influenza virus capture. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3962–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Gildersleeve, J.C.; Blixt, O.; Shin, I. Carbohydrate microarrays. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4310–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Peng, H.; Reid, S.; Ni, N.; Fang, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, B. Carbohydrate biomarkers for future disease detection and treatment. Sci. China Chem. 2010, 53, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, L.; Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J.; Sobsey, M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009, 43, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallapaty, S. How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak. Nature 2020, 580, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Zhen-dong, T.; Hong-ling, W.; Ya-xin, D.; Ke-feng, L.; Jie-nan, L.; Wen-jie, W.; Chen, Y.; Meng-lu, Y.; Peng, L.; et al. Detection of Novel Coronavirus by RT-PCR in Stool Specimen from Asymptomatic Child, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 26, 1337. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.-H.; Ni, W.; Wu, Q.; Li, W.-J.; Li, G.-J.; Wang, W.-D.; Tong, J.-N.; Song, X.-F.; Wing-Kin Wong, G.; Xing, Q.-S. Prolonged viral shedding in feces of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilliam, R.S.; Weidmann, M.; Moresco, V.; Purshouse, H.; O’Hara, Z.; Oliver, D.M. COVID-19: The environmental implications of shedding SARS-CoV-2 in human faeces. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G.; Bonadonna, L.; Lucentini, L.; Kenmoe, S.; Suffredini, E. Coronavirus in water environments: Occurrence, persistence and concentration methods - A scoping review. Water Res. 2020, 179, 115899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, G.N.; Korpi, A.; Sipponen, M.H.; Zou, T.; Kostiainen, M.A.; Österberg, M. Agglomeration of Viruses by Cationic Lignin Particles for Facilitated Water Purification. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 4167–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Patil, A.; Raza, B.G.; Reurink, D.; van den Hengel, S.K.; Rutjes, S.A.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; Roesink, H.D.W.; de Vos, W.M. Cationically modified membranes using covalent layer-by-layer assembly for antiviral applications in drinking water. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 570–571, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.Y.; Li, Q.; Veselinovic, J.; Kim, B.-S.; Klibanov, A.M.; Hammond, P.T. Bactericidal and virucidal ultrathin films assembled layer by layer from polycationic N-alkylated polyethylenimines and polyanions. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4079–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.Q.; Wang, Z.X.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Shao, L. Designing Multifunctional Coatings for Cost-Effectively Sustainable Water Remediation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Hsu, B.B.; Rautaray, D.; Haldar, J.; Chen, J.; Klibanov, A.M. Hydrophobic polycationic coatings disinfect poliovirus and rotavirus solutions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedenbiedel, F.; Tiller, J.C. Antimicrobial Polymers in Solution and on Surfaces: Overview and Functional Principles. Polymers 2012, 4, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P.T. Engineering materials layer-by-layer: Challenges and opportunities in multilayer assembly. Aiche J. 2011, 57, 2928–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsona, E.O.; Muthuraj, R.; Ojogbo, E.; Valerio, O.; Mekonnen, T.H. Engineered nanomaterials for antimicrobial applications: A review. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassyouni, M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.H.; Zoromba, M.S.; Abdel-Hamid, S.M.S.; Drioli, E. A review of polymeric nanocomposite membranes for water purification. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 73, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.W.H.; Chu, J.T.S.; Perera, M.R.A.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Yen, H.-L.; Chan, M.C.W.; Peiris, M.; Poon, L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G.; Todt, D.; Pfaender, S.; Steinmann, E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyankov, O.V.; Bodnev, S.A.; Pyankova, O.G.; Agranovski, I.E. Survival of aerosolized coronavirus in the ambient air. J. Aerosol. Sci. 2018, 115, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampf, G. Potential role of inanimate surfaces for the spread of coronaviruses and their inactivation with disinfectant agents. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2020, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, I.; Choi, H.-J. Respiratory Protection against Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Seale, H.; Raina MacIntyre, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Pang, X.; Wang, Q. Mask-wearing and respiratory infection in healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.C.-C.; Wong, S.-C.; Chuang, V.W.-M.; So, S.Y.-C.; Chen, J.H.-K.; Sridhar, S.; To, K.K.-W.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Hung, I.F.-N.; Ho, P.-L. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.M.; Weiss, P.D.; Weiss, D.E.; Weiss, J.B. Disrupting the Transmission of Influenza A: Face Masks and Ultraviolet Light as Control Measures. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, S32–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, R.S.; Christian, M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can. J. Anesth. /J. Can. D’anesthésie 2020, 67, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.W.H.; Ho, P.-L.; Hota, S.S. Outbreak of a new coronavirus: What anaesthetists should know. Br. J. Anaesth 2020, 124, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.C.; Lee, J.K.L.; Yau, S.Y.; Charm, C.Y.C. Sensitivity and specificity of the user-seal-check in determining the fit of N95 respirators. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Verani, M.; Lombardi, R.; Casini, B.; Privitera, G. Environmental survey to assess viral contamination of air and surfaces in hospital settings. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 77, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, T.F.; Kournikakis, B.; Bastien, N.; Ho, J.; Kobasa, D.; Stadnyk, L.; Li, Y.; Spence, M.; Paton, S.; Henry, B.; et al. Detection of Airborne Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Coronavirus and Environmental Contamination in SARS Outbreak Units. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 1472–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Chang, S.Y.; Sung, M.; Park, J.H.; Bin Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.-P.; Choi, W.S.; Min, J.-Y. Extensive Viable Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Coronavirus Contamination in Air and Surrounding Environment in MERS Isolation Wards. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, V. Viruses as Agents Of Airborne Contagion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1980, 353, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.T.; Li, Y.; Wong, T.W.; Tam, W.; Chan, A.T.; Lee, J.H.; Leung, D.Y.; Ho, T. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-H.; Wan, G.-H.; Wu, Y.-K.; Tsao, K.-C. Airborne Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Concentrations in a Negative-Pressure Isolation Room. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2006, 27, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tong, T.R. Airborne Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus and Its Implications. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 1401–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Transmission and phylogenetic evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Gerber, S.I.; Swerdlow, D.L. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: Update for Clinicians. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 1686–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.M.; Norton, A.; Young, F.P.; Collins, D.W. Airborne transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 to healthcare workers: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Peng, W.; Chen, R. More awareness is needed for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2019 transmission through exhaled air during non-invasive respiratory support: Experience from China. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.E.; Chen, L.H. Travellers give wings to novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). J. Travel Med. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T.M. Personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic—A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Is the coronavirus airborne? Experts can’t agree. Nature 2020, 580, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.T.; Hwang, J. Filtration and inactivation of aerosolized bacteriophage MS2 by a CNT air filter fabricated using electro-aerodynamic deposition. Carbon 2014, 75, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiliket, G.; Sage, D.L.; Moules, V.; Rosa-Calatrava, M.; Lina, B.; Valleton, J.M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Lebrun, L. A new material for airborne virus filtration. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 173, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Atab, N.; Qaiser, N.; Badghaish, H.; Shaikh, S.F.; Hussain, M.M. Flexible Nanoporous Template for the Design and Development of Reusable Anti-COVID-19 Hydrophobic Face Masks. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7659–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junter, G.A.; Lebrun, L. Cellulose-based virus-retentive filters: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 16, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, S.J.; Otto, D.P.; Liebenberg, W.; Lvov, Y.M.; de Villiers, M.M. Preparation and characterization of directly compactible layer-by-layer nanocoated cellulose. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 404, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Khanna, R.; Shekhar, R.; Jha, K. Chitosan nanocoating on cotton textile substrate using layer-by-layer self-assembly technique. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 119, 2793–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Mano, J.; Queiroz, J.; Gouveia, I. Layer-by-Layer Deposition of Antibacterial Polyelectrolytes on Cotton Fibres. J. Polym. Environ. 2012, 20, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, K.; Kant, K.; Bramhecha, I.; Mathur, P.; Sheikh, J. Multifunctional modification of cotton using layer-by-layer finishing with chitosan, sodium lignin sulphonate and boric acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juikar, S.J.; Vigneshwaran, N. Microbial production of coconut fiber nanolignin for application onto cotton and linen fabrics to impart multifunctional properties. Surf. Interfaces 2017, 9, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Slopek, R.P.; Condon, B.; Grunlan, J.C. Surface Coating for Flame-Retardant Behavior of Cotton Fabric Using a Continuous Layer-by-Layer Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3805–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-C.; Schulz, J.; Grunlan, J.C. Polyelectrolyte/Nanosilicate Thin-Film Assemblies: Influence of pH on Growth, Mechanical Behavior, and Flammability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 2338–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.; Seo, S.; Kwon, H.; Kim, D.; Park, Y.T. Fire protection behavior of layer-by-layer assembled starch-clay multilayers on cotton fabric. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 11433–11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Kundu, C.; Wang, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Sheng, H.; Pan, Y.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. A green approach to constructing multilayered nanocoating for flame retardant treatment of polyamide 66 fabric from chitosan and sodium alginate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, G.; Kirkland, C.; Morgan, A.B.; Grunlan, J.C. Intumescent multilayer nanocoating, made with renewable polyelectrolytes, for flame-retardant cotton. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2843–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.J.; Moule, M.G.; Sule, P.; Smith, T.; Cirillo, J.D.; Grunlan, J.C. Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Nanocoating Dramatically Reduces Bacterial Adhesion to Polyester Fabric. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesh Babu, K.; Ravindra, K.B. Bioactive antimicrobial agents for finishing of textiles for health care products. J. Text. Inst. 2015, 106, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, C.; Xiao, D.; Meng, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Tian, X. Environmentally friendly assembly multilayer coating for flame retardant and antimicrobial cotton fabric. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 90, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerkez, I.; Kocer, H.B.; Worley, S.D.; Broughton, R.M.; Huang, T.S. N-Halamine Biocidal Coatings via a Layer-by-Layer Assembly Technique. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4091–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, I.C.; Wan, A.C.A.; Yim, E.K.F.; Leong, K.W. Controlled release from fibers of polyelectrolyte complexes. J. Control. Release 2005, 104, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, R.K.; Guimarães, F.E.G.; Carvalho, A.J.F. Wood pulp fiber modification by layer-by-layer (LBL) self-assembly of chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose complex: Confocal microscopy characterization. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 273, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudi, H.; Saedi, H.; Kermanian, H. Fabrication of self-assembled polysaccharide multilayers on broke chemi-mechanical pulp fibers: Effective approach for paper strength enhancement. Polym. Test. 2019, 74, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Qin, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. LBL deposition of chitosan/heparin bilayers for improving biological ability and reducing infection of nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smelcerovic, A.; Knezevic-Jugovic, Z.; Petronijevic, Z. Microbial Polysaccharides and their Derivatives as Current and Prospective Pharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 3168–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetisen, A.K.; Qu, H.; Manbachi, A.; Butt, H.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Hinestroza, J.P.; Skorobogatiy, M.; Khademhosseini, A.; Yun, S.H. Nanotechnology in Textiles. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3042–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehulster, L.M. Healthcare Laundry and Textiles in the United States: Review and Commentary on Contemporary Infection Prevention Issues. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathi, V.; Thilagavathi, G. Development of plasma enhanced antiviral surgical gown for healthcare workers. Fash. Text. 2015, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathi, V.; Thilagavathi, G. Developing antiviral surgical gown using nonwoven fabrics for health care sector. Afr. Health Sci. 2013, 13, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.R. Novel Approaches to avoid Microbial Adhesion onto Biomaterials. J. Biotechnol. Biomater. 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannelli, I.; Reigada, R.; Suárez, I.; Janner, D.; Carrilero, A.; Mazumder, P.; Sagués, F.; Pruneri, V.; Lakadamyali, M. Functionalized Surfaces with Tailored Wettability Determine Influenza A Infectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15058–15066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulwan, M.; Wójcik, K.; Zapotoczny, S.; Nowakowska, M. Chitosan-Based Ultrathin Films as Antifouling, Anticoagulant and Antibacterial Protective Coatings. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2012, 23, 1963–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brynda, E.; Houska, M.; Jiroušková, M.; Dyr, J.E. Albumin and heparin multilayer coatings for blood-contacting medical devices. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfand, R.; Santerre, J.P.; Ernsting Mark, J.; Wang Vivian, Z.; Tjahyadi, S. Self-Eliminating Coatings. European Patent EP2214748B1, 17 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Erbey, J.R., II; Tucker, B.J.; Upperco, J.L. Coated and/or Impregnated Ureteral Catheter or Stent and Method. U.S. Patent US16/696,026, 27 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, P.A.; Wynne, J.H. Development of Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Latex Paint Surfaces Employing Active Amphiphilic Compounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 2878–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Caruso, F.; Dähne, L.; Decher, G.; De Geest, B.G.; Fan, J.; Feliu, N.; Gogotsi, Y.; Hammond, P.T.; Hersam, M.C.; et al. The Future of Layer-by-Layer Assembly: A Tribute to ACS Nano Associate Editor Helmuth Möhwald. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6151–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunlertchai, S.; Srisang, S.; Nasongkla, N. Development of antimicrobial coating by layer-by-layer dip coating of chlorhexidine-loaded micelles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Frongia, M.E.; Cardellach, M.; Miller, C.A.; Stafford, G.P.; Leggett, G.J.; Hatton, P.V. Functionalised nanoscale coatings using layer-by-layer assembly for imparting antibacterial properties to polylactide-co-glycolide surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2015, 21, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.; Heo, J.; Lee, S.-E.; Shin, J.-W.; Chang, M.; Hong, J. Polysaccharide-based superhydrophilic coatings with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agent-delivering capabilities for ophthalmic applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 68, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Mazumder, A.; Nasongkla, N. Layer-by-layer nanocoating of antibacterial niosome on orthopedic implant. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 547, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasin, S.; Sun, D. Propelling textile waste to ascend the ladder of sustainability: EOL study on probing environmental parity in technical textiles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windler, L.; Height, M.; Nowack, B. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobials for textile applications. Environ. Int. 2013, 53, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G. 8-Disposable and reusable medical textiles. In Textiles for Hygiene and Infection Control; McCarthy, B.J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, C.; Nanke, K.; Furumura, S.; Arimatsu, M.; Fukuyama, M.; Maeda, H. Effects of disposable bath and towel bath on the transition of resident skin bacteria, water content of the stratum corneum, and relaxation. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2019, 47, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).