Quercetin and Related Chromenone Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Targeting Neurological and Mental Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

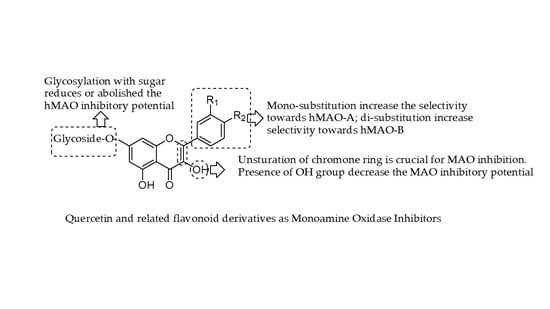

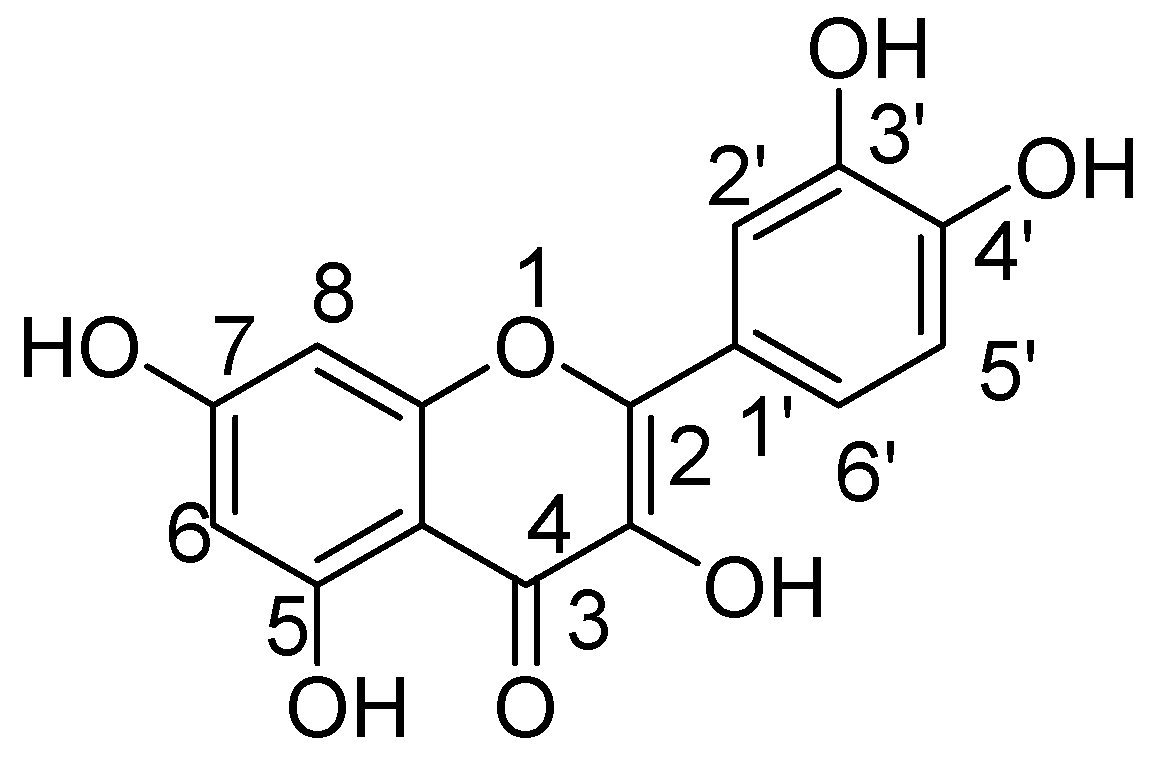

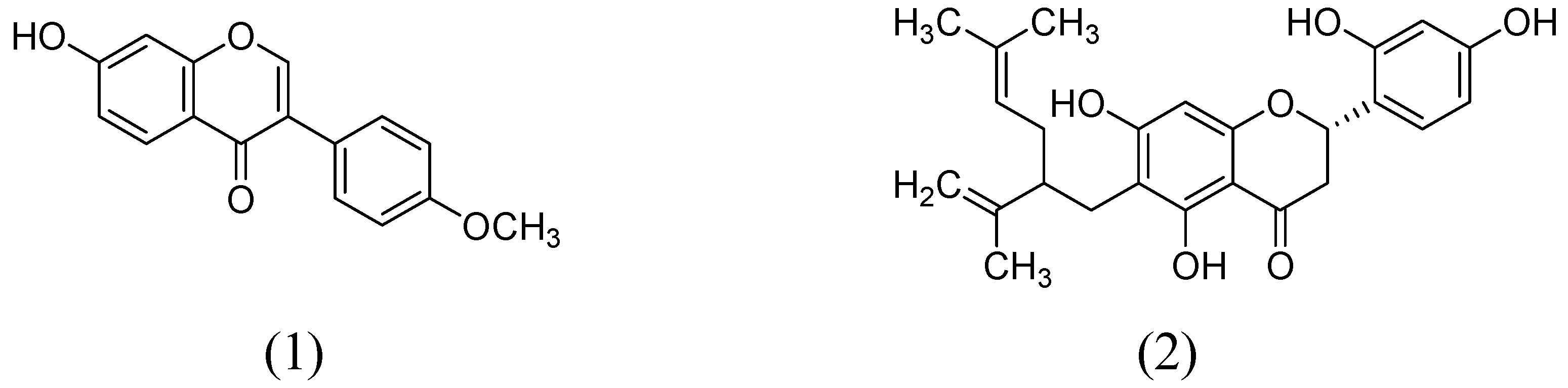

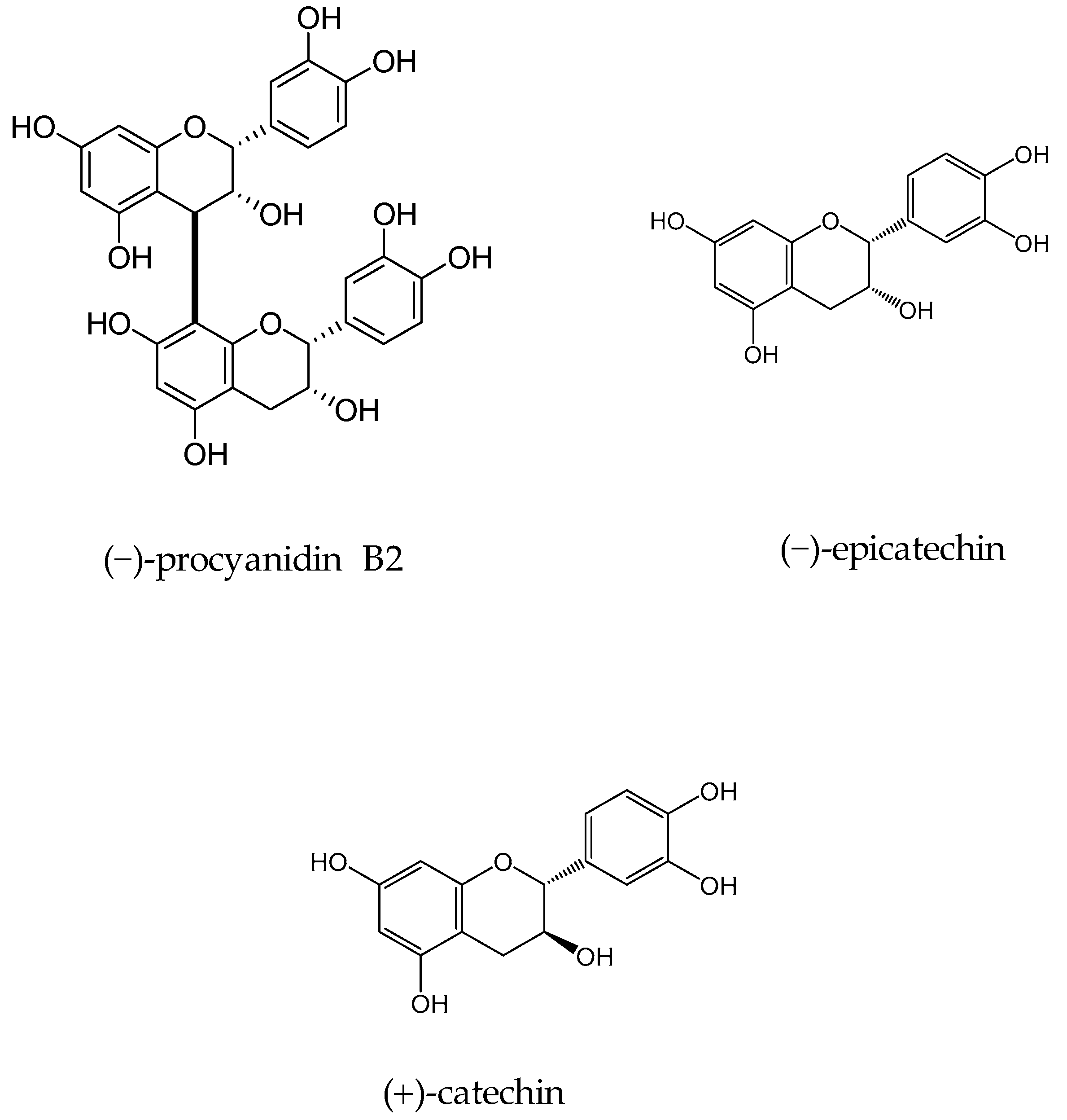

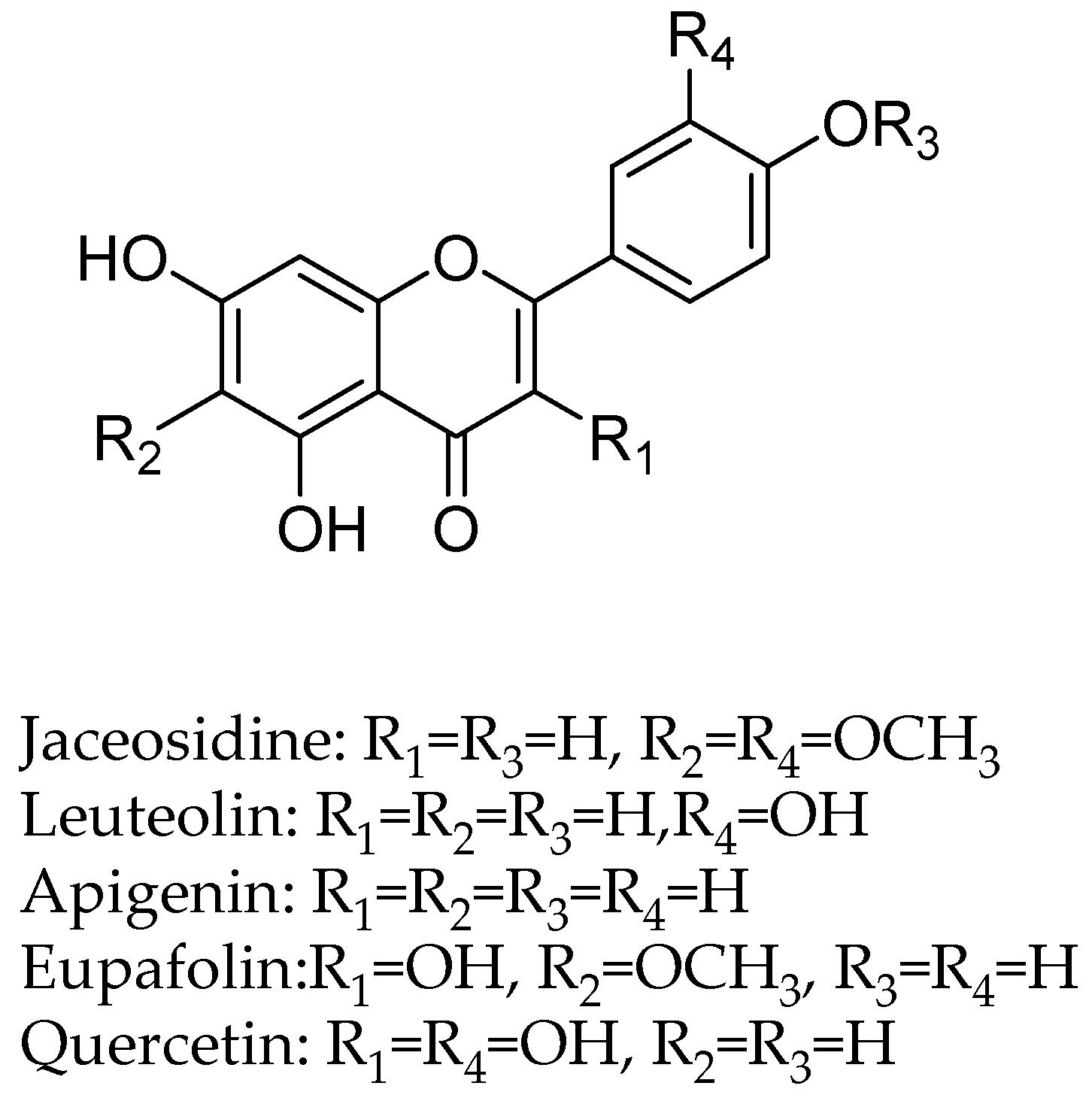

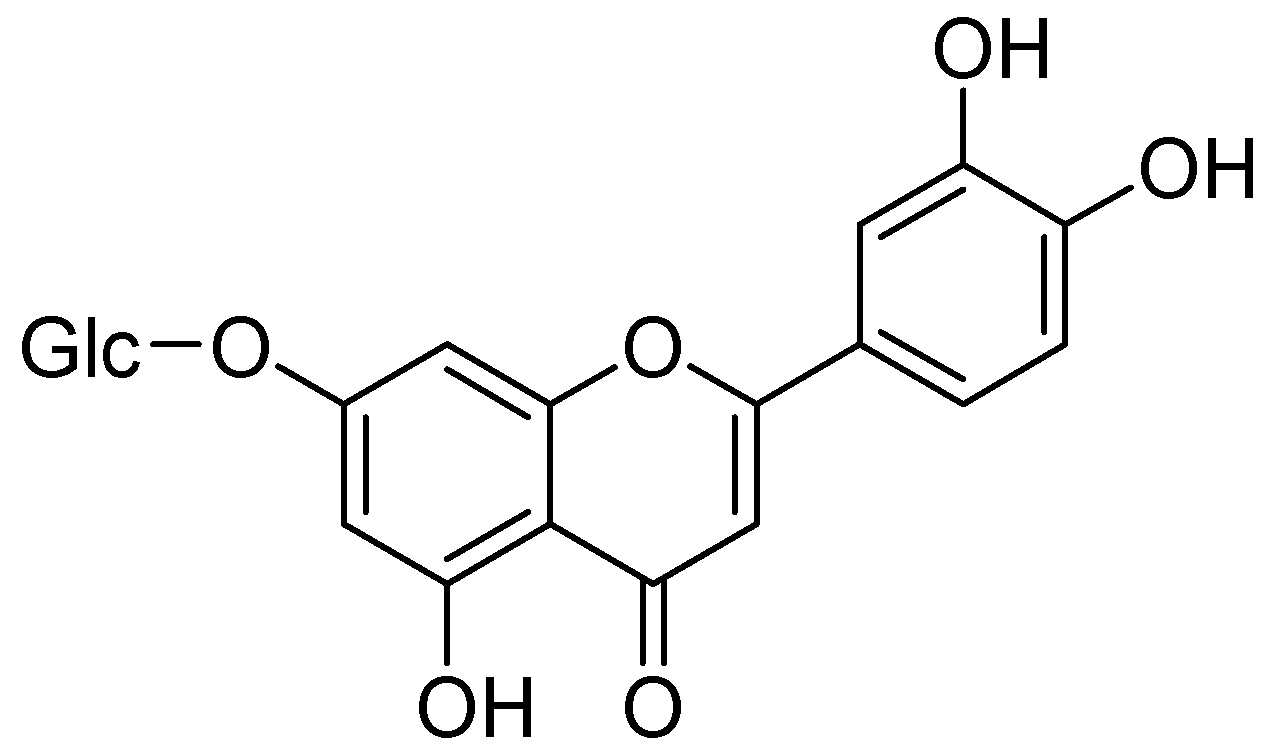

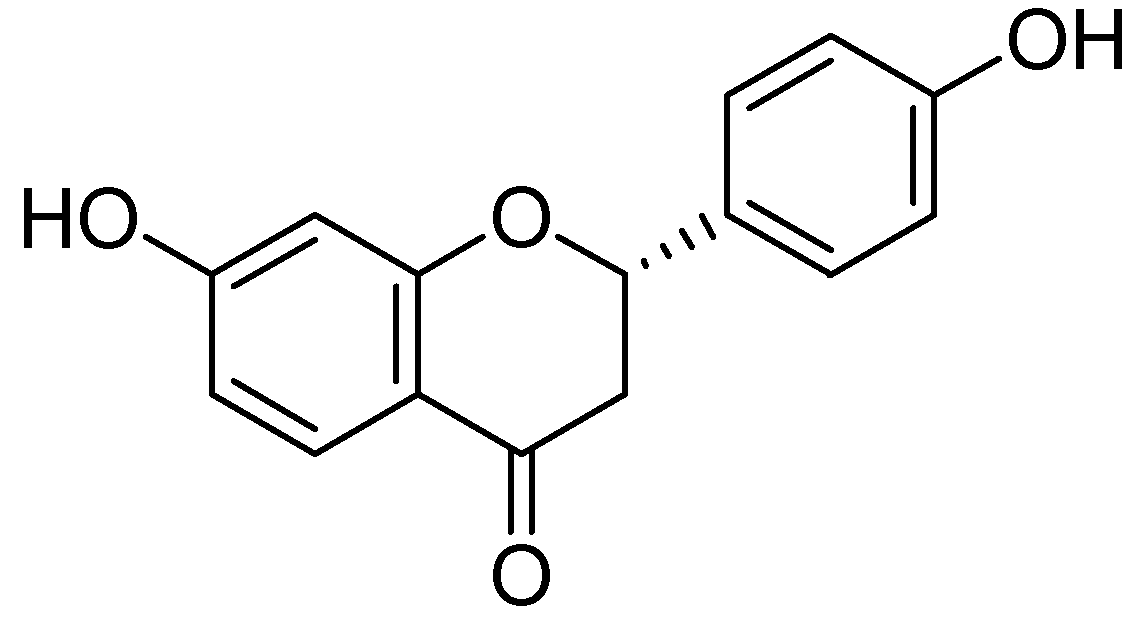

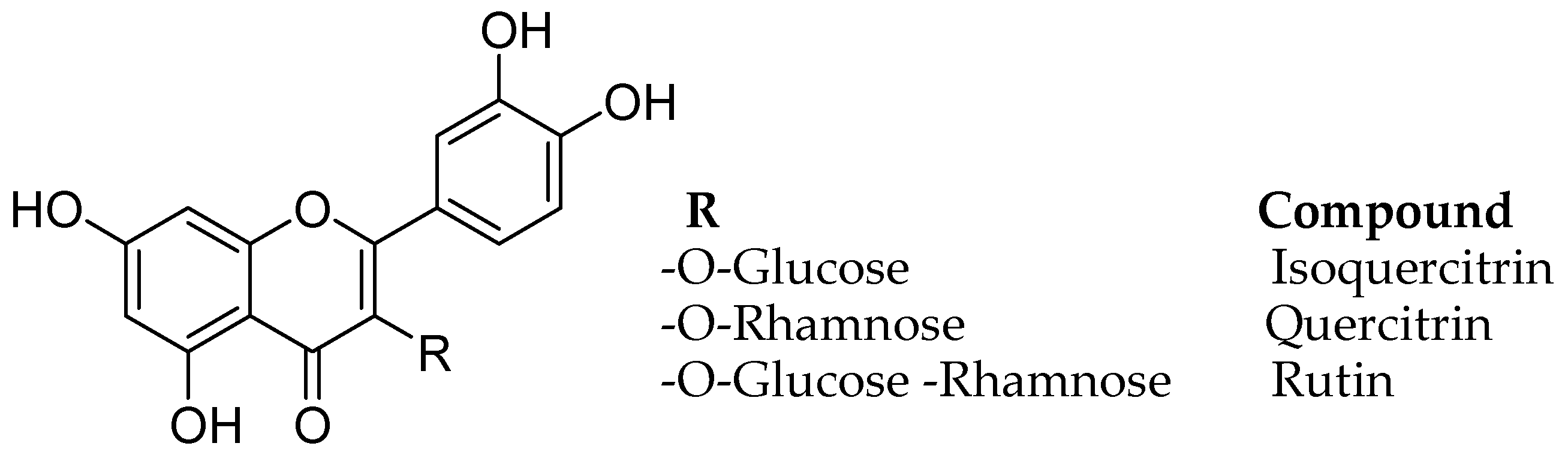

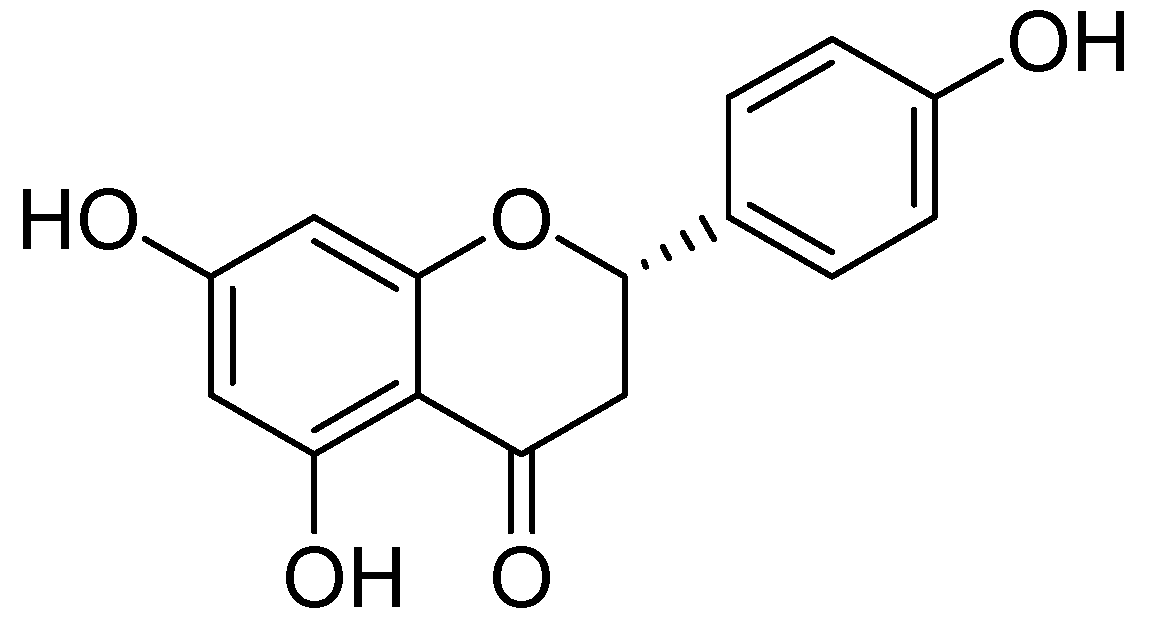

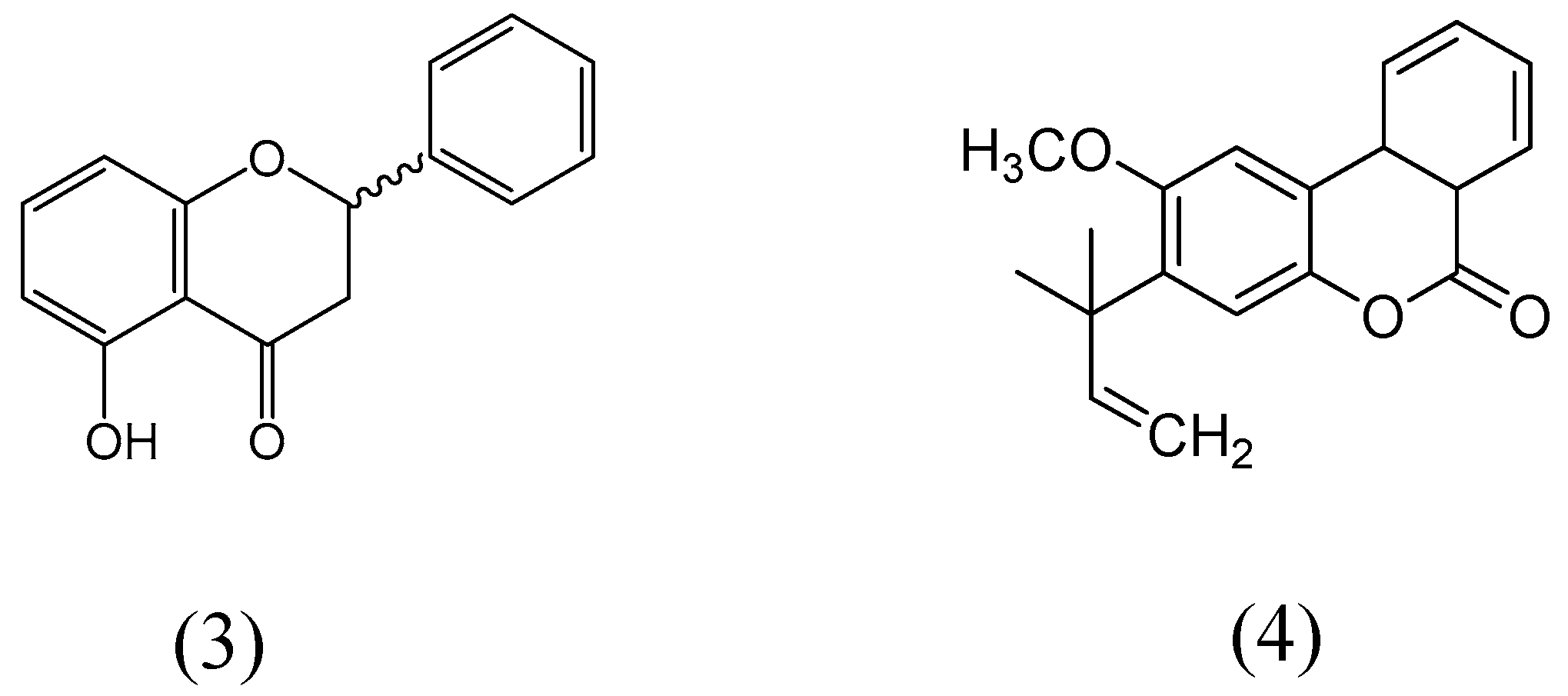

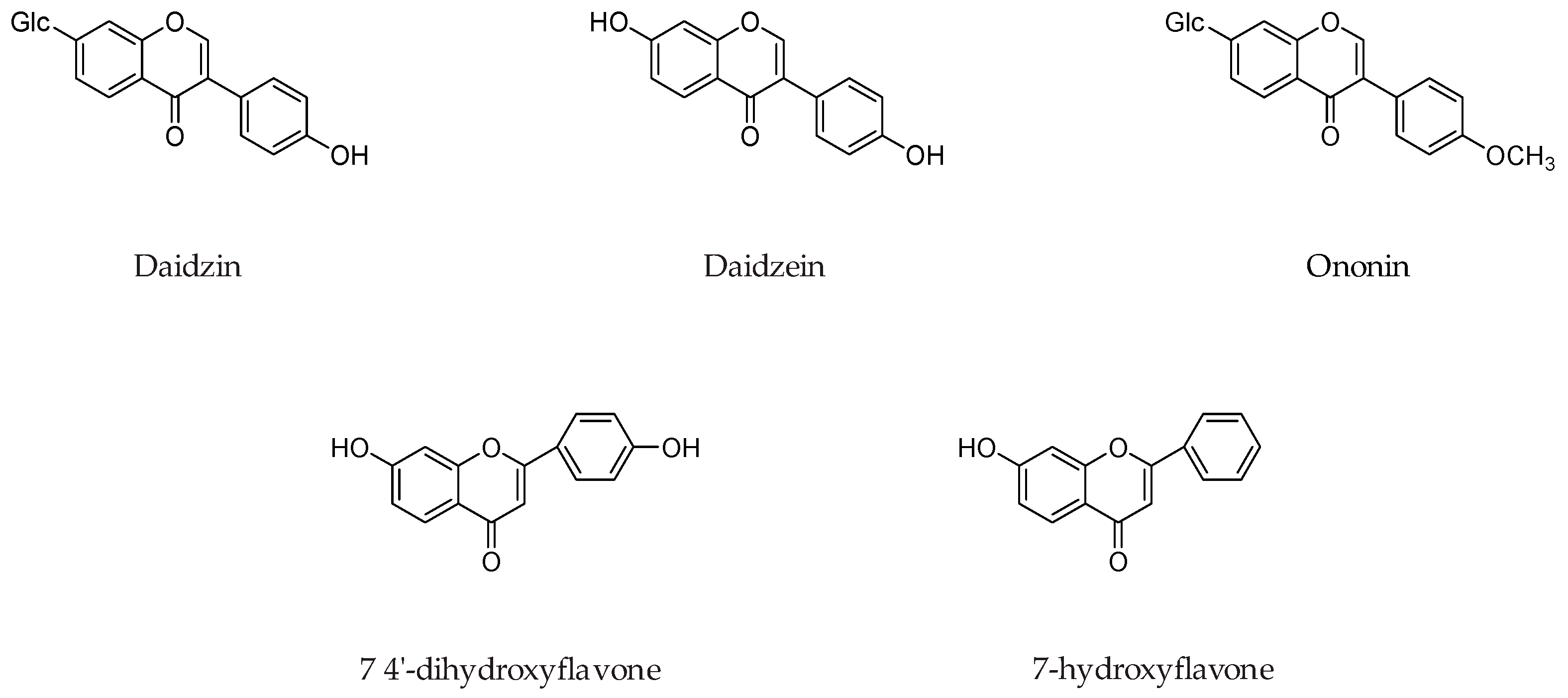

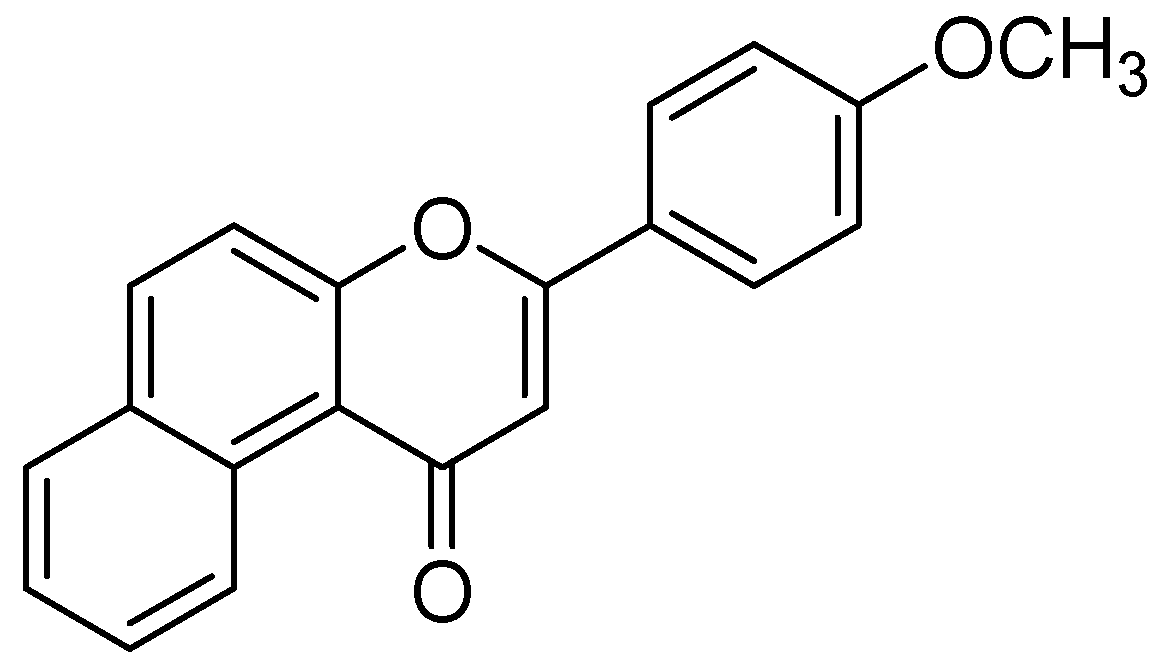

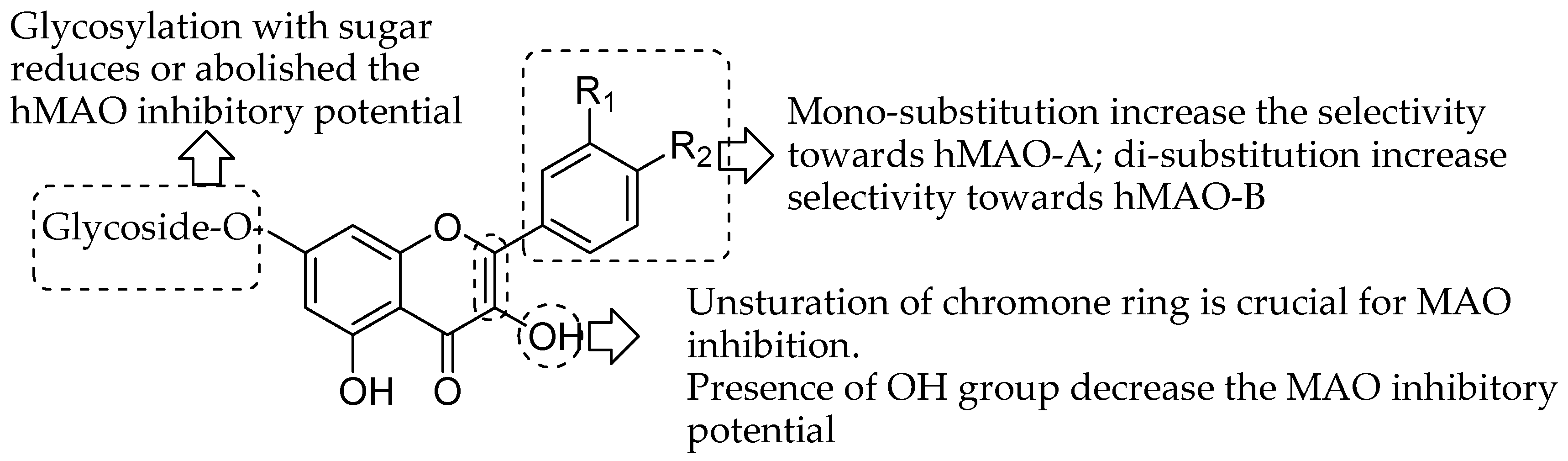

2. Chemistry and Therapeutic Journey of Quercetin and Related Derivatives

3. Molecular Docking Studies of Quercetin and Related Flavonoid Derivatives

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D. Evidence-based health policy-lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science 1996, 274, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, R.J.; Mendlowicz, M.V.; Marrocos, R.P.; Figueira, I.L. Anxiety disorders in outpatients with schizophrenia: Prevalence and impact on the subjective quality of life. J. Psychiatry. Res. 2005, 39, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G.; Chochinov, H.M.; Skirko, M.G.; Allard, P.; Chary, S.; Gagnon, P.R.; Macmillan, K.; De Luca, M.; O’Shea, F.; Kuhl, D.; et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J. Pain. Symptom. Manage. 2007, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, L.S.; Nielsen, N.H.; Champion, H.C. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999, 14, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstün, T.B.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Chatterji, S.; Mathers, C.; Murray, C.J. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004, 184, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaria, R.N.; Maestre, G.E.; Arizaga, R.; Friedland, R.P.; Galasko, D.; Hall, K.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Ogunniyi, A.; Perry, E.K.; Potocnik, F.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: Prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet. Neurol. 2008, 7, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacho, M.; Coelho-Cerqueira, E.; Follmer, C.; Nabavi, S.M.; Rastrelli, L.; Uriarte, E.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. A medical approach to the monoamine oxidase inhibition by using 7H-benzo [e] perimidin-7-one derivatives. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Hong, J.T.; Lee, H.J. Antioxidant properties of natural polyphenols and their therapeutic potentials for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 87, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Tariq, A.; Ahmed, T.; Budzyńska, B.; Tejada, S.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S.M. Tanshinones and mental diseases: From chemistry to medicine. Rev. Neurosciences. 2016, 27, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joao Matos, M.; Viña, D.; Vazquez-Rodriguez, S.; Uriarte, E.; Santana, L. Focusing on new monoamine oxidase inhibitors: Differently substituted coumarins as an interesting scaffold. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 2210–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, M.B.; Edmondson, D.; Tipton, K.F. The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nature. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Fridkin, M.; Youdim, M.B. From antioxidant chelators to site-activated multi-target chelators targeting hypoxia inducing factor, beta-amyloid, acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase A/B. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carradori, S.; D’Ascenzio, M.; Chimenti, P.; Secci, D.; Bolasco, A. Selective MAO-B inhibitors: A lesson from natural products. Molec. Divers. 2014, 18, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel Nabavi, S.; Uriarte, E.; Rastrelli, L.; Modak, B.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. Aporphines and Parkinson’s Disease: Medical Tools for the Future. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1906–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, P.; Malik, N.; Khatkar, A. 3D-QSAR and in-silico studies of natural products and related derivatives as monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helguera, A.; Perez-Machado, G.; NDS Cordeiro, M.; Borges, F. Discovery of MAO-B inhibitors-present status and future directions part I: Oxygen heterocycles and analogs. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanez, M.; Fernando Padin, J.; Alberto Arranz-Tagarro, J.; Camiña, M.; Laguna, R. History and therapeutic use of MAO-A inhibitors: A historical perspective of MAO-A inhibitors as antidepressant drug. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 2275–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, B.; Marley, E.; Price, J.; Taylor, D. Hypertensive interactions between monoamine oxidase inhibitors and foodstuffs. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1967, 113, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P.; Malik, N.; Khatkar, A.; Kulharia, M. Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase and Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitory Potential of Coumarins: A. Review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P.; Malik, N.; Khatkar, A. Docking-Related Survey on Natural-Product-Based New Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors and Their Therapeutic Potential. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2017, 20, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe-Sellers, B.J.; Staggs, C.G.; Bogle, M.L. Tyramine in foods and monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs: A crossroad where medicine, nutrition, pharmacy, and food industry converge. J. Food. Compost. Anal. 2006, 19, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, M.H. Dietary restrictions and drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: The state of the art. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007, 68, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shih, J.C.; Chen, K.; Ridd, M.J. Monoamine oxidase: From genes to behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1999, 22, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M.; Brown-Borg, H.; Ren, J.; Sharma, S.; Shavali, S.; El ReFaey, H.; Carlson, E.C. Therapeutic efficacy of selegiline in neurodegenerative disorders and neurological diseases. Curr. Drug. Targets. 2006, 7, 1513–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalgutkar, A.S.; Dalvie, D.K.; Castagnoli, N.; Taylor, T.J. Interactions of nitrogen-containing xenobiotics with monoamine oxidase (MAO) isozymes A and B: SAR studies on MAO substrates and inhibitors. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 1139–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carradori, S.; Silvestri, R. New Frontiers in Selective Human MAO-B Inhibitors: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 6717–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, A.; Hernandez, C.; Kunduzova, O.; Bompart, G.; Cambon, C.; Parini, A.; Francés, B. Age-dependent increase in hydrogen peroxide production by cardiac monoamine oxidase A in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2003, 284, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, H.S.; Weiss, C.; Silides, D.J.; Cohen, G. Coupling of dopamine oxidation (monoamine oxidase activity) to glutathione oxidation via the generation of hydrogen peroxide in rat brain homogenates. J. neurochem. 1981, 36, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.F.; Zhang, H.Y. Multipotent natural agents to combat Alzheimer’s disease. Functional spectrum and structural features. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M. Hybrid molecules incorporating natural products: Applications in cancer therapy, neurodegenerative disorders and beyond. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlund, I. Review of the flavonoids quercetin, hesperetin, and naringenin. Dietary sources, bioactivities, bioavailability, and epidemiology. Nutr. Res. 2004, 24, 851–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt, R.J.; Van Nood, E.L.; Van Hoorn, D.E.; Boelens, P.G.; Van Norren, K.; Van Leeuwen, P.A. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proteggente, A.R.; Pannala, A.S.; Paganga, G.; Buren, L.V.; Wagner, E.; Wiseman, S.; Put, F.V.; Dacombe, C.; Rice-Evans, C.A. The antioxidant activity of regularly consumed fruit and vegetables reflects their phenolic and Vitamin C composition. Free. Radic. Res. 2002, 36, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirpara, K.V.; Aggarwal, P.; Mukherjee, A.J.; Joshi, N.; Burman, A.C. Quercetin and its derivatives: Synthesis, pharmacological uses with special emphasis on anti-tumor properties and prodrug with enhanced bio-availability. Anticancer. Agents. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardia, T.; Rotelli, A.E.; Juarez, A.O.; Pelzer, L.E. Anti-inflammatory properties of plant flavonoids. Effects of rutin, quercetin and hesperidin on adjuvant arthritis in rat. II farmaco. 2001, 56, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Anacona, J.R. Metal complexes of the flavonoid quercetin: Antibacterial properties. Transit. Metal. Chem. 2001, 26, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, T.N.; Middleton, E.; Ogra, P.L. Antiviral effect of flavonoids on human viruses. J. Med. Virol. 1985, 15, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ververidis, F.; Trantas, E.; Douglas, C.; Vollmer, G.; Kretzschmar, G.; Panopoulos, N. Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part I: Chemical diversity, impacts on plant biology and human health. Biotechnol. J. 2007, 2, 1214–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, A.K.; Saaby, L. Flavonoids and the CNS. Molecules 2011, 16, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

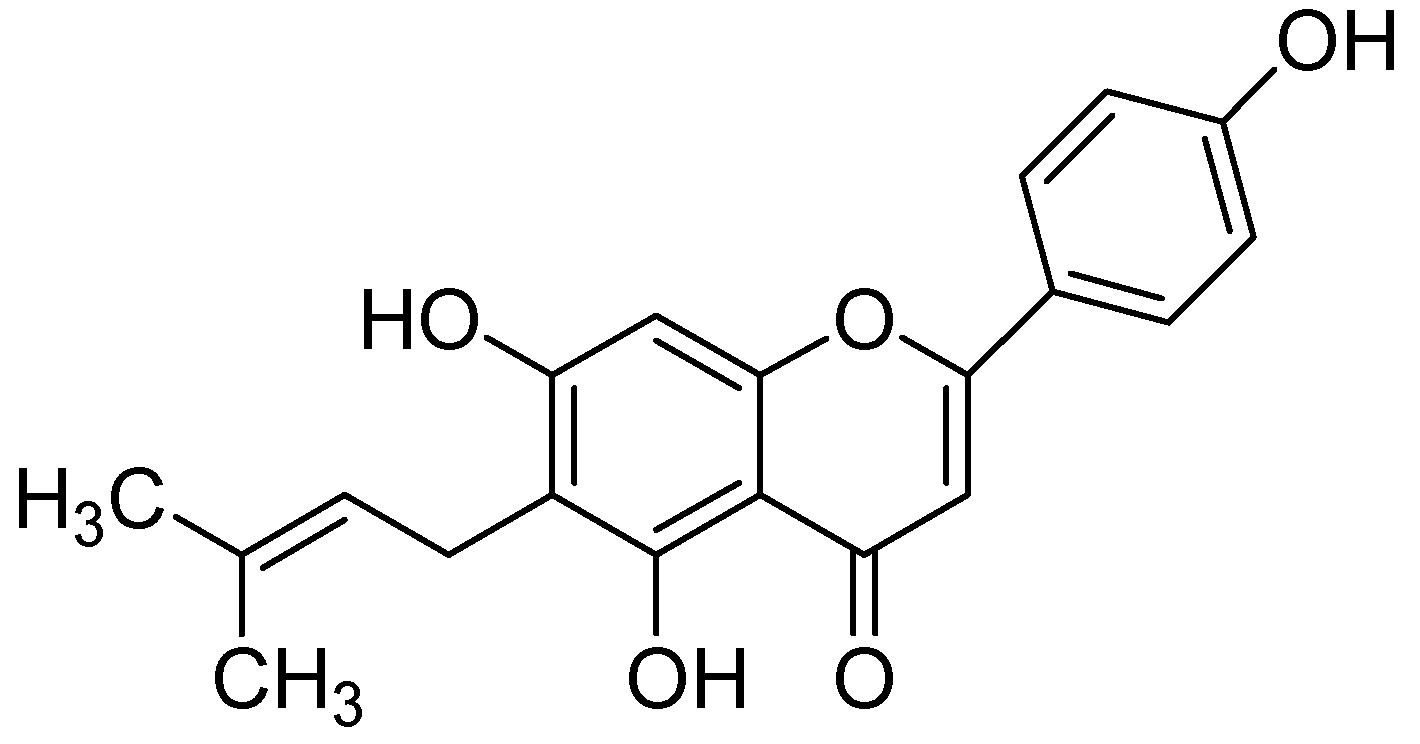

- Hwang, J.S.; Lee, S.A.; Hong, S.S.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, M.K.; Hwang, B.Y.; Ro, J.S. Monoamine oxidase inhibitory components from the roots of Sophora flavescens. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoylenko, V.; Rahman, M.M.; Tekwani, B.L.; Tripathi, L.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Khan, S.I.; Khan, I.A.; Miller, L.S.; Joshi, V.C.; Muhammad, I. Banisteriopsis caapi, a unique combination of MAO inhibitory and antioxidative constituents for the activities relevant to neurodegenerative disorders and Parkinson’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.C.; Lin, R.D.; Chen, C.T.; Lee, M.H. Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition by active principles from Uncaria rhynchophylla. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Chung, H.Y.; Lee, I.K.; Oh, S.U.; Yoo, I.D. Phenolics with inhibitory activity on mouse brain monoamine oxidase (MAO) from whole parts of Artemisia vulgaris L (Mugwort). Food. Sci. Biotechnol. 2000, 9, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Son, Y.K.; Kim, G.H.; Hwang, K.H. Xanthoangelol and 4-hydroxyderricin are the major active principles of the inhibitory activities against monoamine oxidases on Angelica keiskei K. Biomol. Ther. 2013, 21, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

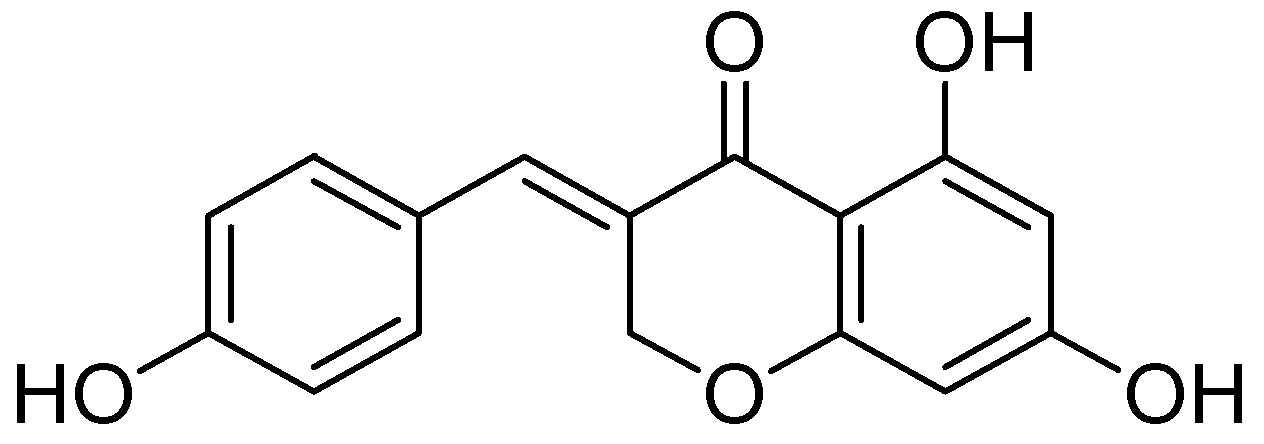

- Pan, X.; Kong, L.D.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C.H.; Tan, R.X. In vitro inhibition of rat monoamine oxidase by liquiritigenin and isoliquiritigenin isolated from Sinofranchetia chinensis. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2000, 21, 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.H.; Lin, R.D.; Shen, L.Y.; Yang, L.L.; Yen, K.Y.; Hou, W.C. Monoamine oxidase B and free radical scavenging activities of natural flavonoids in Melastoma candidum D. Don. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5551–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloley, B.D.; Urichuk, L.J.; Morley, P.; Durkin, J.; Shan, J.J.; Pang, P.K.; Coutts, R.T. Identification of kaempferol as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor and potential neuroprotectant in extracts of Ginkgo biloba leaves. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000, 52, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaby, L.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Jäger, A.K. MAO-A inhibitory activity of quercetin from Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 121, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diermen, D.; Marston, A.; Bravo, J.; Reist, M.; Carrupt, P.A.; Hostettmann, K. Monoamine oxidase inhibition by Rhodiola rosea L. roots. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

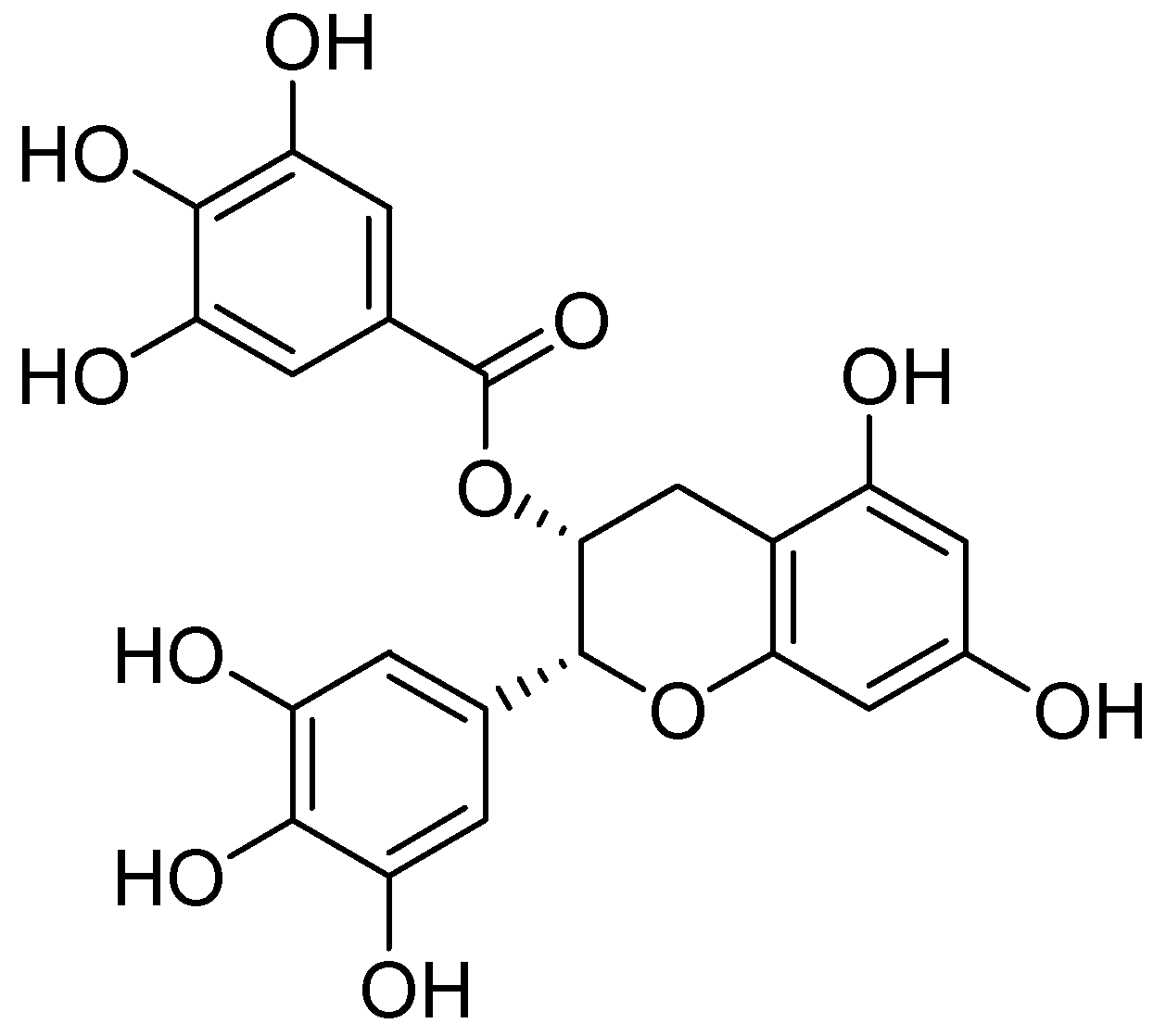

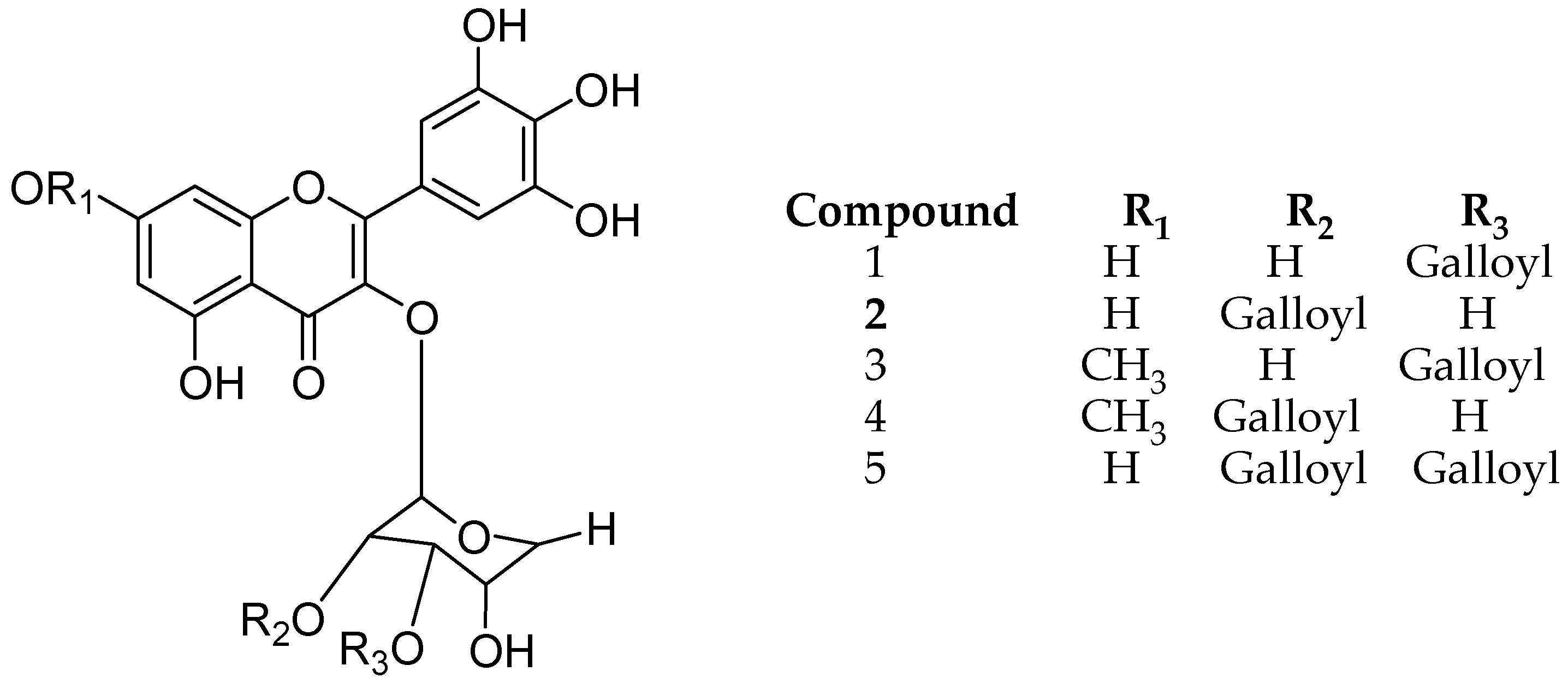

- Lee, T.H.; Liu, D.Z.; Hsu, F.L.; Wu, W.C.; Hou, W.C. Structure-activity relationships of five myricetin galloylglycosides from leaves of Acacia confusa. Bot. Stud. 2006, 47, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- López, V.; Martín, S.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Carretero, M.E.; Jäger, A.K.; Calvo, M.I. Neuroprotective and neurological properties of Melissa officinalis. Neurochem. Res. 2009, 34, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; West, B.J. Antidepressant effects of noni fruit and its active principals. Asian. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 3, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, S.Y.; Han, Y.N.; Han, B.H. Monoamine oxidase-A inhibitors from medicinal plants. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1988, 11, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, H.T.; Stafford, G.I.; van Staden, J.; Christensen, S.B.; Jäger, A.K. Isolation of the MAO-inhibitor naringenin from Mentha aquatica L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraguchi, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Kabbash, A.; Fujioka, T.; Ishizu, T.; Yagi, A. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors from Gentiana lutea. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2255–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreiseitel, A.; Korte, G.; Schreier, P.; Oehme, A.; Locher, S.; Domani, M.; Hajak, G.; Sand, P.G. Berry anthocyanins and their aglycons inhibit monoamine oxidases A and B. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 59, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.H.; Hong, S.S.; Hwang, J.S.; Lee, M.K.; Hwang, B.Y.; Ro, J.S. Monoamine oxidase inhibitory components from Cayratia japonica. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2007, 30, 13–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.N.; Noh, D.B.; Han, D.S. Studies on the monoamine oxidase inhibitors of medicinal plants I. Isolation of MAO-B inhibitors from Chrysanthemum indicum. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1987, 10, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

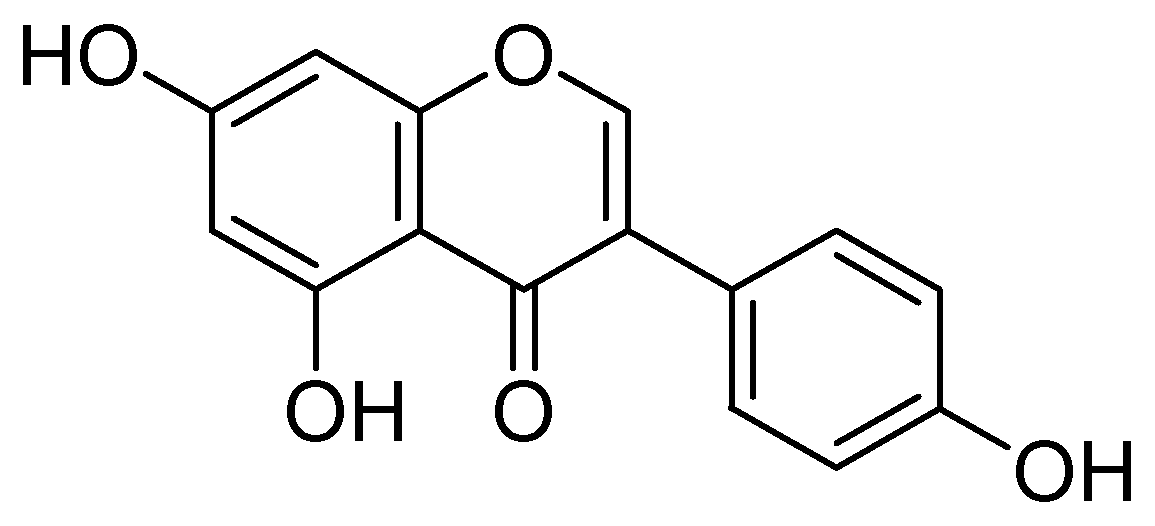

- Gao, G.Y.; Li, D.J.; Keung, W.M. Synthesis of potential antidipsotropic isoflavones: Inhibitors of the mitochondrial monoamine oxidase-aldehyde dehydrogenase pathway. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

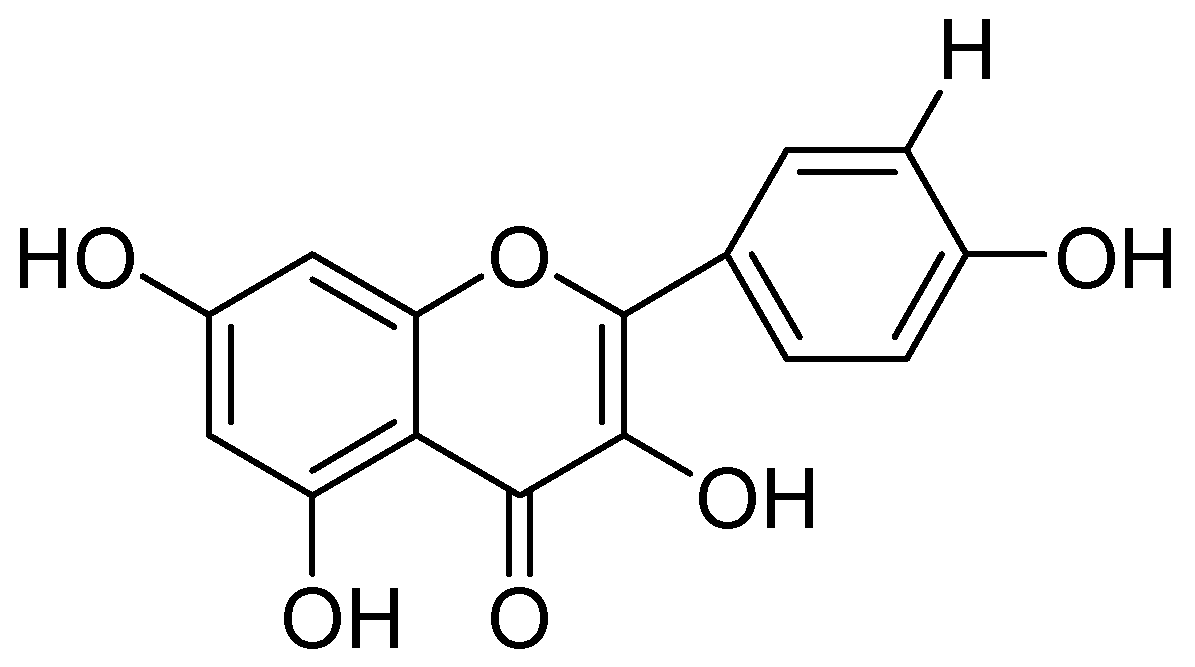

- Ji, H.F.; Zhang, H.Y. Theoretical evaluation of flavonoids as multipotent agents to combat Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 2006, 767, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeson, J.M.; Sanford, B.; Monti, D.A. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): A review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature. Psychopharmacology 2001, 153, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Fang, J.S.; Bai, X.Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.T.; Liu, A.L.; Du, G.H. In silico Target Fishing for the Potential Targets and Molecular Mechanisms of Baicalein as an Antiparkinsonian Agent: Discovery of the Protective Effects on NMDA Receptor-Mediated Neurotoxicity. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2013, 81, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beula, S.J.; Raj, V.B.; Mathew, B. Isolation and molecular recognization of 6-prenyl apigenin towards MAO-A as the active principle of seeds of Achyranthes aspera. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2014, 4, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaro, M.C.; Astorino, C.; Petzer, A.; Carradori, S.; Alcaro, F.; Costa, G.; Artese, A.; Rafele, G.; Russo, F.M.; Petzer, J.P.; et al. Kaempferol as selective human MAO-A inhibitor: analytical detection in calabrian red wines, biological and molecular modeling studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1394–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimenti, F.; Cottiglia, F.; Bonsignore, L.; Casu, L.; Casu, M.; Floris, C.; Secci, D.; Bolasco, A.; Chimenti, P.; Granese, A.; et al. Quercetin as the Active Principle of Hypericum h ircinum Exerts a Selective Inhibitory Activity against MAO-A: Extraction, Biological Analysis, and Computational Study. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

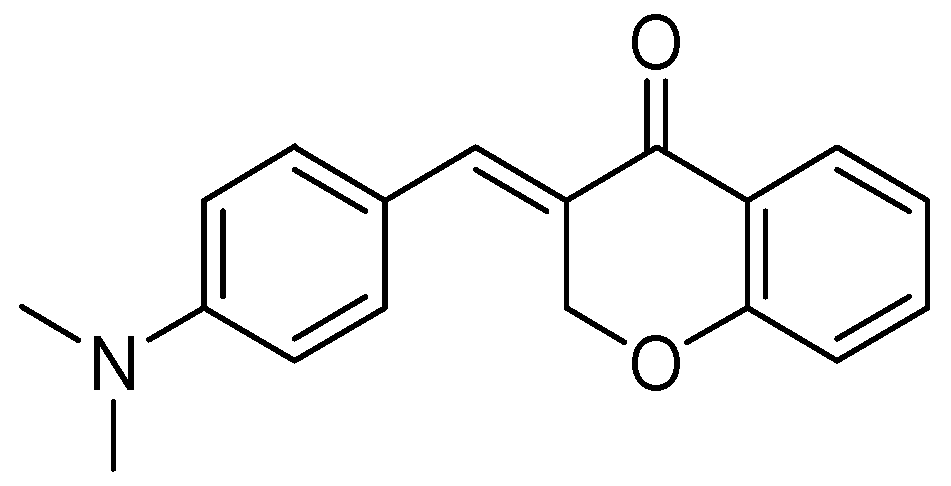

- Jo, G.; Sung, S.H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, B.G.; Yoon, J.; Lee, H.O.; Ji, S.Y.; Koh, D.; Ahn, J.H.; Lim, Y. Discovery of Monoamine Oxidase A Inhibitors Derived from in silico Docking. Bull. Korean. Chem. Soc. 2012, 33, 3841–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarey, M.; Kramer, B.; Lengauer, T.; Klebe, G. A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 261, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, N.; Bolasco, A.; Fioravanti, R.; Proietti, M.L.; Orallo, F.; Yáñez, M.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S. Homoisoflavonoids: Natural scaffolds with potent and selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibition properties. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2155–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, F.; Fioravanti, R.; Bolasco, A.; Chimenti, P.; Secci, D.; Rossi, F.; Yáñez, M.; Orallo, F.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S.; et al. A new series of flavones, thioflavones, and flavanones as selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkmenoglu, F.P.; Baysal, İ.; Ciftci-Yabanoglu, S.; Yelekci, K.; Temel, H.; Paşa, S.; Ezer, N.; Çalış, İ.; Ucar, G. Flavonoids from Sideritis species: Human monoamine oxidase (hMAO) inhibitory activities, molecular docking studies and crystal structure of xanthomicrol. Molecules 2015, 20, 7454–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaraman, D.; Vignesh, G.; Selvaraj, R.; Dare, B.J. Identification of potential monoamine oxidase inhibitor from herbal source for the treatment of major depressive disorder: An in-silico screening approach. Der. Pharma. Chemica. 2015, 7, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zarmouh, N.; Eyunni, S.; Mazzio, E.; Messeha, S.; Elshami, F.; Soliman, K. Bavachinin and Genistein, Two Novel Human Monoamine Oxidase-B (MAO-B) Inhibitors in the Psoralea Corylifolia Seeds. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 771–772. [Google Scholar]

- Zarmouh, N.O.; Mazzio, E.A.; Elshami, F.M.; Messeha, S.S.; Eyunni, S.V.; Soliman, K.F. Evaluation of the inhibitory effects of bavachinin and bavachin on human monoamine oxidases A and B. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarmouh, N.O.; Messeha, S.S.; Elshami, F.M.; Soliman, K.F. Evaluation of the Isoflavone Genistein as Reversible Human Monoamine Oxidase-A and-B Inhibitor. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Flavonoids | Target Protein | Important Amino Acid Residues | Comments | Software | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | MAO-A PDB (2Z5X) | Tyr444, Tyr197, and Asn181 | Quercetin fitted well within the hMAO-A active site than in the hMAO-B active site due to development of highest π-π interaction and intermolecular hydrogen bonds. | Schrodinger [61] | Zhang et al. [62] |

| Baicalein | MAO-B PDB (2Z5Y) | Leu164 and Leu167 | Two catecholic OH groups of baicalein showed hydrogen bonding with Leu167and Leu164 respectively. | Schrodinger [61] | Gao et al. [63] |

| 6-prenyl apigenin | hMAO-A PDB (2Z5X) | Tyr 444 and Tyr407 | 6-prenyl apigenin the structural shared π electrons of the hydroxyl groups were sandwiched between phenolic side chains of TYR407 and TYR 444 composed the ‘aromatic cage’ of the hydrophobic pocket of the enzyme. | AutoDock [64] | Beula et al. [65] |

| Kaempferol | hMAO-A PDB (2Z5X) | Ile335 of hMAO-A Tyr326 of hMAO-B | Kaempferol in the dynamic site of hMAO-A established hydrophobic interactions with important residues of hMAO-A for a longer time than in the hMAO-B pocket. | Schrödinger [61] | Gidaro et al. [66] |

| Sr. No | Flavonoid | Binding Score Energy Value for MAO-A (Kcal/mol) | Calculated Ki for MAO-A (μM) | Binding Score Energy Value for MAO-B (Kcal/mol) | Calculated Ki for MAO-B (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl-β-d-allopyranosyl-(1→2)]-6″-O-acetyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | −3.81 | 1660.00 | 8.92 | - |

| 2 | Salvigenin | −8.30 | 0.867 | −7.51 | 3.63 |

| 3 | Isoscutellarein 7-O-[6′′′-O-acetyl-β-d-allopyranosyl-(1→2)]-β-d-glucopyranoside | −4.15 | 930.10 | 5.79 | - |

| 4 | Xanthomicrol | −7.80 | 1.90 | −5.78 | 64.26 |

| Sr. No | Name of the Lead | Binding Free Energy (Kcal/mol) | Inhibition Constant Ki (µM) | No. of Hydrogen Bonds | Interacting Amino Acid Residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kaempferol | −5.17 | 4.63 | 12 | 397 TRP, 352 PHE, 406 CYS, 444 TYR, 448 ALA, 303 VAL, 51ARG, 407 TYR, 52 THR, 435 THR, 305 LYS, 445 MET |

| 2 | Quercetin | −4.40 | 636.60 | 9 | 436 GLU, 448 ALA, 52 THR, 435 THR, 407 TYR,51 ARG, 406 CYS, 23 ILE, 445 MET |

| 3 | Apigenin | −7.65 | 2.61 | 8 | 305 LYS, 397 TRP, 448 ALA, 51 ARG, 406 CYS, 435 THR, 352 PHE, 407 TYR |

| 4 | Luteolin | −7.67 | 2.42 | 11 | 448 ALA, 23 ILE, 435 THR, 406 CYS, 303 VAL, 52 THR, 51 ARG, 397 TRP, 445 MET, 407 TYR,444TYR |

| 5 | Brofaromine (Standard) | −7.55 | 3.06 | 10 | 303 VAL, 397 TRP, 51 ARG, 52 THR, 406 CYS, 305 LYS, 445 MET, 407 TYR, 435 THR, 448 ALA |

| Sr. No | Natural Ligands | MAO-A Active Site PDB (2BXR) | MAO-B Active Site PDB (1GOS) | Overall Bonds | MAO Inhibition Selectivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Score | Predicted H-Bond | Docking Score | Predicted H-Bond | H-Bond | Active Site Residue | |||

| 1. | Bavachinin | −1.06 | 0 | −6.82 | 2 | OH⋯O HO⋯HN | THR:201: A THR:201: A | B |

| 3 | Safinamide | −0.22 | 0 | −6.12 | 3 | NH⋯O NH⋯O NH⋯O | GLU:84: A THR:201: A PRO:102: A | B |

| 4 | Bavachin | −8.72 | H2O-726 | −3.95 | 0 | ⋯ | ⋯ | NA |

| Sr. No | Name of the Lead | MAO-A | MAO-B | RMSD Å | Amino Acid | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Score | Predicted H-Bond | Docking Score | Predicted H-Bond | ||||

| 1 | Genistein (GST) | −7.0 | 0 | −12.8 | 2 (OH⋅ ⋅ ⋅ N) | 2.27 | THR: 201: A |

| 2 | Daidzein (DZ) | −6.9 | 0 | −12.8 | 1 (O⋅ ⋅ ⋅ HN) | 2.32 | THR: 201: A |

| Sr. No | Name of the Lead | hMAO-B | hMAO-A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | ΔG Bind (Kcal/mol) | IC50 (μM) | ΔG Bind (Kcal/mol) | ||

| 1 | Kaempferol | >100 | −42.66 | 0.525 ± 0.035 | −49.52 |

| 2 | Quercetin | >100 | −46.98 | 3.98 ± 0.265 | −48.35 |

| 3 | Harmine | - | - | 0.029 ± 0.0042 | −46.07 |

| 4 | Safinamide | 0.0479 ± 0.00472 | −73.70 | - | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dhiman, P.; Malik, N.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Uriarte, E.; Khatkar, A. Quercetin and Related Chromenone Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Targeting Neurological and Mental Disorders. Molecules 2019, 24, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030418

Dhiman P, Malik N, Sobarzo-Sánchez E, Uriarte E, Khatkar A. Quercetin and Related Chromenone Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Targeting Neurological and Mental Disorders. Molecules. 2019; 24(3):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030418

Chicago/Turabian StyleDhiman, Priyanka, Neelam Malik, Eduardo Sobarzo-Sánchez, Eugenio Uriarte, and Anurag Khatkar. 2019. "Quercetin and Related Chromenone Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Targeting Neurological and Mental Disorders" Molecules 24, no. 3: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030418

APA StyleDhiman, P., Malik, N., Sobarzo-Sánchez, E., Uriarte, E., & Khatkar, A. (2019). Quercetin and Related Chromenone Derivatives as Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Targeting Neurological and Mental Disorders. Molecules, 24(3), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030418