Abstract

Bombyx batryticatus (B. batryticatus), a well-known traditional animal Chinese medicine, has been commonly used in China for thousands of years. The present paper reviewed advances in traditional uses, origin, chemical constituents, pharmacology and toxicity studies of B. batryticatus. The aim of the paper is to provide more comprehensive references for modern B. batryticatus study and application. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) culture, drugs containing B. batryticatus have been used to treat convulsions, headaches, skin prurigo, scrofula, tonsillitis and fever. Many studies indicate B. batryticatus contains various compounds, including protein and peptides, fatty acids, flavonoids, nucleosides, steroids, coumarin, polysaccharide and others. Numerous investigations also have shown that extracts and compounds from B. batryticatus exert a wide spectrum of pharmacological effects both in vivo and in vitro, including effects on the nervous system, anticoagulant effects, antitumor effects, antibacterial and antifungal effects, antioxidant effects, hypoglycemic effects, as well as other effects. However, further studies should be undertaken to investigate bioactive compounds (especially proteins and peptides), toxic constituents, using forms and the quality evaluation and control of B. batryticatus. Furthermore, it will be interesting to study the mechanism of biological activities and structure-function relationships of bioactive constituents in B. batryticatus.

1. Introduction

Bombyx batryticatus (B. batryticatus) is the dried larva of Bombyx mori L. (silkworm of 4–5 instars) infected by Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill [1]. It is one of the most popular traditional Chinese medicines, called “Jiangcan” in Chinese vernacular and has been used in China for thousands of years. In addition, it is also widely used in Korea and Japan [2]. B. batryticatus is derived from silkworm spontaneously infected by Beauveria bassiana originally [3]. Currently, it is mainly produced through artificial breeding techniques by artificial inoculation of Beauveria bassiana [4].

B. batryticatus, as a common animal medicine in traditional Chinese, Korean, and Japanese medicine systems, has been utilized to treat convulsions, epilepsy, cough, asthma, headaches, skin prurigo, scrofula, tonsillitis, urticarial, parotitis and purpura [2,5,6]. Modern investigations have demonstrated that B. batryticatus possesses various pharmacological activities, including effects on nervous system (anticonvulsant effects, antiepileptic effects, and neurotrophic effects), anticoagulant effects, antitumor effects, antibacterial and antifungal effects, antioxidant effects, hypoglycemic effects, as well as other effects [7,8,9]. In addition, it is reported that B. batryticatus contains many different constituents including proteins, peptides, fatty acids, flavonoids, nucleosides, steroids, coumarin, polysaccharide and others [7,8,9,10].

In the current review, the advances in traditional uses, origins, chemistry, pharmacology and toxicity of B. batryticatus are systematically reviewed. Additionally, the directions and perspectives for future study on B. batryticatus are also discussed in the paper.

2. Traditional Usages

B. batryticatus has been used as a traditional medicine for many centuries in China based on its wide spectrum of biological and pharmacological activities. Traditionally, B. batryticatus has commonly been used to treat liver wind with phlegm, convulsion, acute panic of child, tetanus, stroke, fever, headache, sore throat, itchy rubella, as well as mumps [1]. B. batryticatus listed firstly in “Sheng Nong’s herbal classic”, a famous monograph of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) during the Han Dynasty more than 1000 years ago, and it was described to be useful for the treatment of convulsions of child and skin whitening. Based on “Ming Yi Bie Lu” (Liang Dynasty), the main function of B. batryticatus was to treat postpartum pain and morbid leucorrhea in women. According to “Yao Xing Lun” (Tang Dynasty), B. batryticatus was used for the treatment of sweating and uterine bleeding. Subsequently, in “Xin Xiu Ben Cao” (Tang Dynasty), another famous TCM monograph, B. batryticatus was described as a treatment for furuncle. In addition, according to “Ben Cao Gang Mu” (Ming Dynasty), B. batryticatus could treat liver wind with phlegm, headache, and furuncle. Later, in “Yu Qiu Yao Jie” (Qing Dynasty), B. batryticatus was used to treat headache, thoracic obstruction and rubella. In TCM culture, B. batryticatus is salty in taste, even in nature and attributive to the liver, lung and stomach meridians [1].

As an animal traditional Chinese medicine, B. batryticatus has a little stench smell. In addition, it is reported that B. batryticatus has strong side effects on the gastrointestinal tract, and improper use can cause severe allergic reactions [11,12,13]. Therefore, to alleviate its stench smell and alleviate side effects, B. batryticatus is commonly processed by stir-frying with bran to a yellowish color [11,12,13]. In addition, the raw B. batryticatus and stir-fried B. batryticatus are the most common clinically used forms [1]. Although B. batryticatus is widely used in TCM, there are limited researches on its side effects and safety evaluations. The Chinese Pharmacopoeia recommends a dose of 5–10 g for B. batryticatus [1].

Currently, B. batryticatus is a well-known TCM that is used as the main forms of powders, decoctions or infusions for the treatments of convulsion, epilepsy, apoplexy, fever, cough with sputum and other diseases [5,14]. “Chinese Pharmacopoeia”, “Guo Jia Zhong Cheng Yao Biao Zhun”, “Zhong Yao Cheng Fang Zhi Ji”, and “Xin Yao Zhuan Zheng Biao Zhun” revealed 175 prescriptions of Chinese patent drug containing B. batryticatus. The present paper summaries prescriptions of Chinese patent drug and decoctions which B. batryticatus is the main drug (Table 1).

Table 1.

The traditional and clinical uses of B. batryticatus in China.

3. Origin

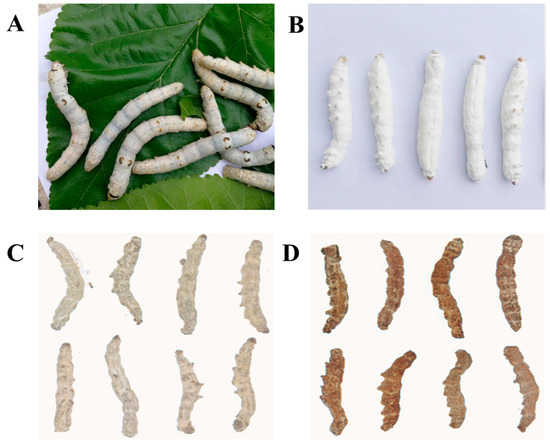

B. batryticatus (Figure 1), derived from silkworm spontaneously infected by Beauveria bassiana, is the by-product of sericulture, which was described in “Sheng Nong’s herbal classic” (Han Dynasty), “Xin Xiu Ben Cao” (Tang Dynasty), “Zheng Lei Ben Cao” (Song dynasty), “Tang Ye Ben Cao” (Yuan dynasty) and “Ben Cao Pin Hui Jing Yao” (Ming dynasty). Dictionary of Chinese Pharmacy by Chen (2010) revealed the formation of B. batryticatus that before silkworm became moth, it was infected by Beauveria bassiana and eventually died [32]. In addition, the lethal mechanism is that when spore of Beauveria bassiana infected silkworm, it can secrete chitinase, then dissolve the epidermis and body wall of silkworm and invade into its body, continuously reproduce and eventually cause the death of silkworm. After silkworm is infected by Beauveria bassiana, it becomes stiff and its surface covered with white conidias of Beauveria bassiana [33].

Figure 1.

Silkworms (A); Silkworms infected by Beauveria bassiana (B); Bombyx batryticatus (B. batryticatus) (C); Stir-fried B. batryticatus (D).

With development of prevention technology of silkworm diseases, the source of B. batryticatus was significantly deficient. Thus, for meeting the market demands, its artificial breeding techniques, namely artificial inoculation of Beauveria bassiana, have received more attention and obtained certain development in recent years [4]. The detailed procedure of artificial breeding of B. batryticatus is as follows: Beauveria bassiana is mixed with warm water and sprayed on silkworms of 4–5 instars; after inoculation for 15–20 min, silkworms are fed with mulberry leaves, and fed every 5.0–6.0 h until they become stiff and white; finally, stiff silkworms are mixed with lime and dried in a ventilated place. The temperature and humidity of the feeding room should be set at 24.0–26.0 °C and 90.0%, respectively [14].

It was recorded that B. batryticatus firstly appeared in Yu county, Henan province in Qin and Han Dynasties [3]. During Tang and Song Dynasties, Henan and Shandong were main producing regions of B. batryticatus recorded in “Ben Cao Tu Jing and Zheng Lei Ben Cao”. Later, during Ming and Qing Dynasties, its main regions moved to south area, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, which was recorded in “Ben Cao Chong Yuan”. Subsequently, Sichuan and Guangdong became the main producing regions of B. batryticatus. Currently, the main regions of B. batryticatus bred artificially are Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Shandong and Guangxi in China, and the quality of B. batryticatus in Sichuan is considered to be the best [34].

4. Chemistry

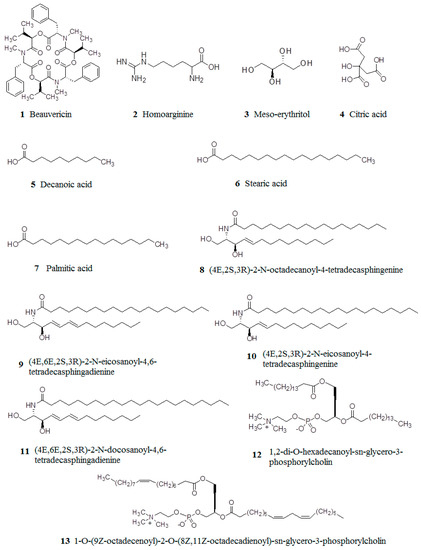

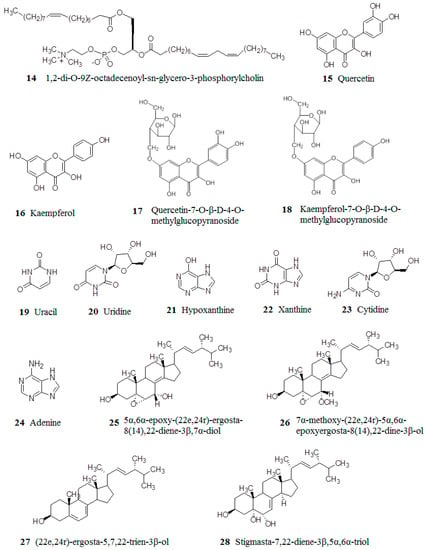

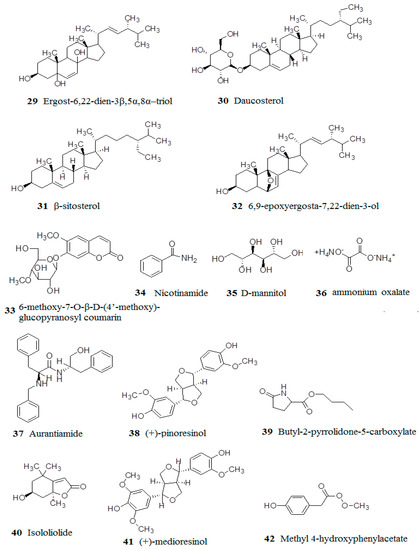

There are various chemical constituents in B. batryticatus, including protein and peptides, fatty acids, flavonoids, nucleosides, steroids, coumarin, polysaccharide and others. In this section, the major chemical constituents and structures of B. batryticatus are presented (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Chemical constituents isolated from B. batryticatus.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of compounds isolated from B. batryticatus.

4.1. Proteins and Peptides

As a traditional animal medicine, the main chemical constituents in B. batryticatus are proteins. It is reported that the content of proteins in B. batryticatus varies in the range within 43.9–74.3% [45,55]. Currently, some research on peptides in B. batryticatus have been reported. BB octapeptide is a novel platelet aggregation inhibitory peptide isolated from B. batryticatus, and its molecular mass and the amino acid sequence are 885.0 Da and Asp-Pro-Asp-Ala-Asp-IIe-Leu-Gln, respectively [35]. Beauvericin (1), a cyclic three carboxylate peptide, was identified from B. batryticatus [36,37,38]. Cyclo(D)-Pro-(D)-Val, Cyclo(S)-Pro-(R)-Leu, Cyclo(D)-Pro-(D)-Ile, Cyclo(D)-Pro-(D)-Phe and Cyclo-(Ala-Pro), belonging to dipeptide, were also isolated from B. batryticatus [36,39]. In 2004, ACIBB were isolated from B. batryticatus, whose molecular mass is 1200.0 Da, and it consisted of 7 kinds of amino acids [40]. Later, homoarginine (2) was identified from B. batryticatus by Cheng et al. (2013a) [41]. Finally, enzymolysis polypeptides by pepsin is studied by Li et al. (2017), and the molecular mass and amino acid number of enzymolysis polypeptide were about 500.0–1000.0 Da and less than 10, respectively [42].

4.2. Fatty Acids

Some studies have been carried out to investigate the fatty acids and their derivatives in B. batryticatus. Five fatty acids were isolated from B. batryticatus: meso-erythritol (3), citric acid (4), decanoic acid (5), stearic acid (6) and palmitic acid (7) [43,44,45]. Seven derivatives of fatty acids in B. batryticatus were identified: (4E,2S,3R)-2-N-octadecanoyl-4-tetradecasphingenine (8), (4E,6E,2S,3R)-2-N-eicosanoyl-4,6-tetradecasphingadienine (9), (4E,2S,3R)-2-N-eicosanoyl-4-tetradecasphingenine (10), (4E,6E,2S,3R)-2-N-docosanoyl-4,6-tetradecasphingadienine (11), 1,2-di-O-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholin (12), 1-O-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-2-O-(8Z,11Z-octadecadienoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholin (13) and 1,2-di-O-9Z-octadecenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholin (14) [46,47].

4.3. Flavonoids

Flavonoids are common constituents of numerous Chinese medicinal materials. To date, only four flavonoids from B. batryticatus have been reported. In 2009, quercetin (15) and kaempferol (16) were detected in RP-HPLC method and the contents were 0.2 and 0.6 mg/g, respectively [48]. Later, quercetin-7-O-β-d-4-O-methylglucopyranoside (17) and qaempferol-7-O-β-d-4-O-methylglucopyranoside (18) were isolated from B. batryticatus [2,36].

4.4. Nucleosides

In 1996, four nucleotides were detected in B. batryticatus by Li et al. (1996) through HPLC method, including uracil (19), uridine (20), hypoxanthine (21) and xanthine (22), and among them, uracil content was highest [47]. Later, in 2003, uracil (19), cytidine (23) and adenine (24) were isolated from B. batryticatus by Kwon et al. (2003b) [49].

4.5. Steroids

Currently, researchers have found and identified many steroids in B. batryticatus. Up to now, eight steroids have been identified from B. batryticatus: 5α,6α-epoxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-8(14),22-diene-3β,7α-diol (25), 7α-methoxy-(22E,24R)-5α,6α-epoxyergosta-8(14),22-dine-3β-ol (26), (22E,24R)-ergosta-5,7,22-trien-3β-ol (27), stigmasta-7,22-diene-3β,5α,6α-triol (28), ergost-6,22-dien-3β,5α,8α–triol (29), daucosterol (30), β-sitosterol (31) and 6,9-epoxyergosta-7,22-dien-3-ol (32) [37,43,50].

4.6. Coumarin

Limited investigations have been carried out to study the coumarin in B. batryticatus. To date, only one coumarin was isolated from B. batryticatus: 6-methoxy-7-O-β-d-(4′-methoxy)-glucopyranosyl coumarin (33) [51].

4.7. Polysaccharide

One study of Ying et al. (2015) showed that polysaccharide yield of B. batryticatus was about 4.4% and it possessed good antioxidant activity [56]. In addition, BBPW-2 was isolated from B. batryticatus and its characteristic was analyzed by Jiang et al. (2014). The results demonstrated that BBPW-2 consisted of β-d-(1 → 2,6)-glucopyranose and β-d-(1 → 2,6)-mannosyl units serving as the backbone, α-d-(1 → 2)-galactopyranose and α-d-(1 → 3)-mannosyl units as branches, and α-d-Manp and β-d-Glcp as terminals [52].

4.8. Trace Elements

18 trace elements have been found in B. batryticatus, including Al, Fe, Ca, Mg, P, B, Ba, Cu, Cr, La, Mn, Ni, Pb, Sr, Ti, U, Y and Zn. Among them, the contents of Al, Fe, Zn, La and Mn were relatively high [57].

4.9. Other Compounds

In addition to the compounds above, some other compounds are also isolated from B. batryticatus. In 2003, nicotinamide (34) was reported to be isolated from B. batryticatus [47]. Then, D-mannitol (35) was identified from B. batryticatus by Yin et al. (2004a) [43]. Furthermore, it is reported that ammonium oxalate (36) was isolated from B. batryticatus. [53,54]. Later, in 2015, the following compounds were also found and identified from B. batryticatus: aurantiamide (37), (+)-pinoresinol (38), butyl-2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxylate (39), isololiolide (40), (+)-medioresinol (41) and methyl 4-hydroxyphenylacetate (42) were isolated from B. batryticatus [39].

5. Pharmacology

5.1. Effects on Nervous System

The characteristic pharmacological activity of B. batryticatus is the effects on nervous system, including anticonvulsant and antiepileptic effects, hypnotic effects, neurotrophic effects and others. The beauvericin can significantly prolong latent period of nikethamide-induced and isoniazid-induced convulsion in mice (125.0 and 250.0 mg/kg, s.c.) [58,59]. In addition, β-sitosterol and ergost-6,22-dien-3,5,8-triol were demonstrated to obviously prolong latent period of isoniazid-induced convulsion in mice (125.0 mg/kg, s.c.) [59]. Chloroform fraction of ethanol extract of B. batryticatus at dose of 20.0 g/kg showed significant effect on nikethamide-induced convulsion in mice [60]. The results obtained by Yao et al. demonstrated that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus possessed significantly antiepileptic effects on epileptic mice induced by maximal electroshock seizure (MES) and metrazol (MET) in dose-dependent and time-dependent manners [61]. Later, another interesting study reported that ammonium oxalate (30.0 and 60.0 mg/kg) also can inhibit epileptic discharge frequency, amplitude, time and pyramidal cell necrosis in hippocampus region of epileptic rats induced by penicillin [62].

In 2003, it was reported that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus had a significant hypnotic effect on mice (25.0 g/kg, p.o. or 12.5 g/kg, s.c.) and rabbits [63]. The extracts (extracted by water and precipitated by ethanol) of B. batryticatus (20.0 g/kg, p.o.) were found to exhibit sedation effect on mice through inhibiting its spontaneous activity [64].

In vitro, some compounds (10.0 μM) isolated from B. batryticatus were found to exert notable neurotrophic effect by stimulation of NGF (nerve growth factor) synthesis in astrocytes, including (4E,2S,3R)-2-N-octadecanoyl-4-tetradecasphingenine, (4E,6E,2S,3R)-2-N-eicosanoyl-4,6-tetradecasphingadienine, (4E,2S,3R)-2-N-eicosanoyl-4-tetradecasphingenine, (4E,6E,2S,3R)-2-N-docosanoyl-4,6-tetradecasphingadienine, 1-O-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-2-O-(8Z,11Z-octadecadienoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine , 1,2-Di-O-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine and 1,2-Di-O-9Z-octadecenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholin [46,47]. Moreover, Bombycis corpus extract (BCE) had a powerful ameliorating effect on neurotoxicity induced by Amyloid-β (Aβ)25–35 in human neuronal cells dose-dependently at the lowest dose of 1.0 μg/mL, and also effectively attenuated the neurotoxic action of NMDA (Nmethyl-d-aspartic acid) [65]. In 2001, another study reported that water extracts of B. batryticatus (1.0 × 10−7–1.0 × 10−6 g/mL) also had significant protective effect against Aβ(25–35) peptide-induced cytotoxicity dose-dependently via inhibiting lipid peroxidation and protecting antioxidative enzymes [66].

5.2. Anticoagulant Effect

Anticoagulant effect is another characteristic pharmacological activity of B. batryticatus. In 2014, it was reported that BB octapeptide, a novel peptide, can inhibit rabbit platelet aggregation induced by collagen and epinephrine in vitro, with the IC50 values of 91.1 and 104.5 μM, respectively [35]. In addition, BB octapeptide also significantly prevented paralysis and death in pulmonary thromboembolism model at doses of 10.0, 30.0 and 50.0 mg/kg, and significantly reduced ferric chloride-induced thrombus formation in rats (5.0, 10.0 and 20.0 mg/kg) [35]. One investigation by Wang et al. (1989) revealed that water extracts of B. batryticatus (20.0 mg/mL) could inhibit blood coagulation [67].

Zhao et al. (2005) demonstrated that increasing total concentration of ammonium oxalate in water extracts of B. batryticatus (33.7–42.3 mg/mL) can prolong TT (thrombase time) [68]. ACIBB (9.0, 18.0 and 36.0 mg/kg, i.v.), belonging to peptide, can significantly inhibit venous thrombosis in rats dose-dependently, by decreasing the contents of Fbg (fibrinogen) and PLg (plasminogen), increasing the activities of tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) and AT-III (antithrombin-III), as well as prolonging APTT (activated partial thromboplastin time), PT (prothrombin time) and TT [69]. Similarly to ACIBB, water extracts of B. batryticatus (350.0 mg/kg, i.v.) also possessed fibrinolytic activity and inhibited venous thrombosis [70]. Injection of B. batryticatus (150.0 mg/L) was reported that can also inhibit venous thrombosis through increasing tPA activity and decreasing PAI-1 activity [71].

5.3. Antitumor Effect

Numerous studies have been conducted on antitumor effects of B. batryticatus in recent years. B. batryticatus possesses significant anti-proliferative effects on human cancer cell lines, such as cervical cancer, liver cancer and gastric cancer [8]. In 2011, it was reported that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus possessed significant anti-cervical cancer effect against HeLa cells at concentrations of 3.0–11.0 mg/mL, and anticancer mechanisms may be associated with induction of apoptosis by down-regulating the expression of Bcl-2 [72]. Another study reported that flavonoids isolated from B. batryticatus (50.0–500.0 µg/mL) also showed strong anti-cervical cancer activities through suppressing proliferation of HeLa cells in a concentration-dependent manner [73]. Later, an oligosaccharide BBPW-2 in B. batryticatus was demonstrated to have notable anti-cervical cancer (HeLa), anti-liver cancer (HepG2) and anti-breast cancer (MCF-7) activities above the dose of 1.0 mg/mL, and the action mechanism was that BBPW-2-induced cellcycle disruption in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases of early and late apoptotic as well as necrotic cells [52]. In addition, ethanol extract of B. batryticatus also had significant anti-cervical cancer activity against HeLa cells with IC50 value of 1.7 mg/mL by inducing apoptosis via the regulation of the Bcl-2 and Bax [74]. Recently, it has been reported that ethanol extract of B. batryticatus can induce apoptosis of human gastric cancer cells SGC-7901 through upregulating expressions of Bax and P21 and downregulating Bc1-2 expressions with IC50 value of 3.2 mg/mL [75]. Another investigation demonstrated that ergosterol, β-Sitosterol and palmitic acid isolated from B. batryticatus exerted significant anti-melanoma activities at the lowest concentrations of 0.1, 0.1 and 0.3 mmol/L, respectively [76].

5.4. Antibacterial and Antifungal Effects

The study of Xiang et al. (2010) revealed that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus possessed antibacterial effect on Escherichia coli with MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) value of 0.6 mg/mL [77]. Another interesting study reported that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus also showed notable antifungal effects on Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Valsa mali and leaf cast of Pericarpium Zanthoxyli dose-dependently with EC50 values of 4.8 × 10−2, 9.9 × 10−2 and 7.8 × 10−2 g/mL, respectively [78].

5.5. Effects on Viruses

In 2016, one study demonstrated that the supernatant (after ethanol extraction and water precipitation) of B. batryticatus possessed antiviral effects against RSV viruses, and the EC50 value was 2.7 × 10−2 g/mL [79]. Interestingly, the research of Zhang et al. (2014) indicated that ethanol extracts of B. batryticatus can significantly increase the virulence of HearNPV via inhibition of the ALP (alkaline phosphatase) activity at concentrations of 40.0–80.0 µg/mL [80].

5.6. Antioxidant Effect

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is one of main causes of various types of diseases. In addition, recently, increasing studies have been performed on the antioxidant effect of B. batryticatus. In 2013, the study of Jiang et al. (2013) demonstrated that flavonoids isolated from B. batryticatus had strong abilities to scavenge DPPH radicals and hydroxyl radicals at concentrations of 5.0 × 10−3–0.1 mg/mL and 0.1–0.4 mg/mL, respectively [73]. Another investigation reported that methanol extract of B. batryticatus possessed notable DPPH radical scavenging, ferric ion-scavenging and lipoxygenase-scavenging activities at the lowest concentrations of 2.0, 8.0 and 4.0 mg/mL, respectively [81]. Later, polysaccharides isolated from B. batryticatus possessed a powerful hydroxyl radical-scavenging effect and reducing power at concentrations of 2.5 × 10−2–0.3 mg/mL [56]. In addition, water extracts of B. batryticatus (1.0 × 10−7–1.0 × 10−6) were reported to possess notable antioxidant effects through inhibiting lipid peroxidation and enhancing SOD activity [66].

5.7. Other Pharmacological Effects

Increasing investigations suggest that B. batryticatus possesses a wide range of other biological activities, such as hypoglycemic effects, anti-fertility effects, improving immune function effects and others. It was reported that flavonoids isolated from B. batryticatus can significantly promote proliferation of HEK293 normal human embryo kidney cell lines at concentrations of 50.0–500.0 µg/mL [73]. The study of Zhao et al. (2014) demonstrated that methanol extracts of B. batryticatus can inhibit tyrosinase activity at concentrations of 5.0, 10.0, 20.0, 40.0 and 80.0 mg/mL [81]. Another investigation revealed that powder of B. batryticatus presented notable hypoglycemic effects in clinical use at the dose of 15.0 g/day for 2 months (p.o.) [82,83]. Additionally, powder of B. batryticatus was also reported to relieve headache caused by disturbing-up of liver Yang at a dose of 18.0 g/day for 3 days (p.o.) in clinic [84]. In 2002, one interesting study indicated that water extracts of B. batryticatus exerted significant anti-fertility effect on mice, and the results showed that water extracts can significantly reduce the weight of ovary, uterus and pregnancy rate in female mice, and increase the weight of testes and seminal vesicles in male mice [85]. Furthermore, another study reported that polysaccharide isolated from B. batryticatus can significantly improve immune function via increasing the immune organ weights, improving phagocyte phagocytosis and lymphocyte transformation rate [86].

5.8. Summary of Pharmacological Effects

B. batryticatus possesses a wide spectrum of pharmacological effects, including effects on the nervous system, anticoagulant effects, antitumor effects, antibacterial and antifungal effects, effects on viruses and antioxidant effects, etc. (Table 3). These pharmacological effects show that the extracts and the compounds from B. batryticatus can used to prevent or treat certain diseases, in particular convulsions, epilepsy, thrombus and cancer. However, there is not enough systematic data on chemical compounds of B. batryticatus and their pharmacological effects.

Table 3.

Pharmacological effects of B. batryticatus.

6. Toxicity

Throughout its long history, B. batryticatus has been generally considered to be a safe TCM in China [5,14]. However, recent poisoning accidents of B. batryticatus were reported by numerous investigations, which is not consistent with traditional understanding of B. batryticatus safety. Cheng (2007), Gao (2011), Li et al. (2011a), Liu et al. (2013) reported 46, 216, 425, 248 clinical cases about poisoning accidents of B. batryticatus, respectively [87,88,89]. Based on the literature, it can be found that occurrences of poisoning accidents for B. batryticatus mainly result from the following reasons: overdose and misuse of B. batryticatus, and quality problems caused by non-standard procedure of production and processing [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Furthermore, as a traditional animal medicine, B. batryticatus is easily contaminated by aflatoxin, which is regarded as carcinogenic or a teratogenic toxic substance in the procedure of processing, storage and transportation [96]. Therefore, it is urgent and important to standardize methods of production and processing and select the proper doses according to the using form of B. batryticatus to avoid adverse reactions and even poisoning.

It was reported that metabolism of ammonium oxalate in the body can produce ammonia easily, and high content of ammonium oxalate may cause blood ammonia poisoning [97]. The content of ammonium oxalate in B. batryticatus is in the range of 5.0–13.0% [53,54]. Thus, overdosing B. batryticatus can possibly cause poisoning. Additionally, toxins secreted by Beauveria bassiana when using infected silkworm, such as beauvericin, chitosan, chitinase and cellulase, can induce cell death procedurally [9]. Currently, the recognized cause of adverse reactions of B. batryticatus is an allergic reaction. Some allogeneic proteins in B. batryticatus, can cause sensitization, immune response and even cause metabolic disorder and dysfunction of central nervous system [97]. One investigation demonstrated that proteins secreted by Beauveria bassiana can cause adverse effects on mice [97]. However, to date the specific constituents causing adverse reactions or poisoning have not been clarified in B. batryticatus. Thus, further studies should be carried out to confirm which constituents are causing side effects or poisoning in B. batryticatus and explore corresponding content ranges.

7. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

B. batryticatus is one of the most important and frequently used traditional animal medicines, which has been used to treat convulsions, cough, asthma, headaches, skin prurigo, scrofula, tonsillitis and other diseases in China. Recently, B. batryticatus has received increasing attention. However, certain aspects still need to be further studied and explored.

There is limited research on bioactive compounds and the mechanism of biological activities of B. batryticatus. Thus, it is essential to strengthen research on bioactive compounds, action mechanisms of the bioactive compounds and their structure-function relationships in B. batryticatus. Current investigations of B. batryticatus mainly focus on its small molecule compounds, but rarely investigate its macromolecular compounds. In addition, as an animal Chinese medicine, the main chemical constituents in B. batryticatus are proteins. Therefore, future investigations of B. batryticatus could be concentrated on its macromolecular compounds, particularly its proteins and peptides. In addition, mechanisms of biological activities of B. batryticatus should be further explored with techniques of modern molecular biology and pharmacology.

Many monographs of TCM record that powder of B. batryticatus is used directly in a total of 65 prescriptions where B. batryticatus is as the main drug [5,14]. However, in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China of all editions except 1963 edition, the only using form of B. batryticatus is decoction. Therefore, further studies should be done to explore which using form (decoction or powder) of B. batryticatus is more reasonable and scientific. Furthermore, based on scientific using form of B. batryticatus, further studies should be done to analyze reasons of adverse reaction or poisoning caused by B. batryticatus and then to establish its safety evaluation system.

Lack of standardized methods of production and processing is another issue of B. batryticatus. In the process of production, lime is often used to dry silkworm infected by Beauveria bassiana to avoid contamination by miscellaneous bacteria, but lime lacks quality standard and contains a high content of heavy metal and other toxic substances, which seriously affects the quality and safety of B. batryticatus [4]. When B. batryticatus is processed by stir-frying with bran to a yellowish color, processing degree is mainly evaluated by experience of pharmaceutical worker, which lacks quantifiable indices and is not objective. Thus, it is crucial to standardize the procedure of production and processing using modern technologies for ensuring quality of B. batryticatus.

Additionally, as an animal medicine containing complicated compounds, quality evaluation and control of B. batryticatus remains challenging for modern researchers. Currently, quality criteria of B. batryticatus in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China only includes a description, microscopic identification, check (impurity, contents of water, total ash, acid insoluble ash and aflatoxin) and extract [1], which is inadequate to reflect the holistic quality of B. batryticatus. Therefore, it is urgent and important to establish suitable quality evaluation and control systems that can reflect the holistic quality of B. batryticatus, such as the fingerprint of the protein or peptide.

In conclusion, this paper provides a comprehensive overview on the traditional uses, chemistry, pharmacology and toxicity of B. batryticatus. In addition, this review also provides some trends and perspectives for the future development of B. batryticatus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773906) and National standardization project of traditional Chinese Medicine of China (No. 2YB2H-Y-SC-41).

Author Contributions

Meibian Hu wrote the Introduction, Origin, Pharmacology, Toxicity sections and Conclusion sections; Zhijie Yu wrote the Chemistry and Pharmacology, and finalized the draft; Jiaolong Wang wrote the Traditional uses section; Yujie Liu and Wei Peng edited the English language; Wenxiang Fan and Jianghua Li sorted out the references; He Xiao and Yongchuan Li drawn the structures of chemical constituents, Wei Peng designed Pharmacology section; Chunjie Wu conceived and designed the whole structure of the review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China Part I; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 375. ISBN 9787506773379. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, H.; Takahashi, N.; Oshima, Y. Novel aromatics bearing 4-O-methylglucose unit isolated from the oriental crude drug Bombyx batryticatus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.X. Sheng Nong’s Herbal Classic Jizhu; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1995; p. 54. ISBN 9787117022514. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.B.; Liu, Y.J.; Xiao, H.; Wu, C.J.; Zhang, J.X. Advance and thinking of researches on artificial culture of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2016, 39, 930–933. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Traditional Chinese Medicine Dictionary; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; p. 1020. ISBN 9787532382712. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton, R.W. Insects and other arthropods used as drugs in Korean traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 65, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Zhu, C.L.; Dai, H. The pharmacological research and clinical applications of Jiangcan and Jiangyong. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 1999, 10, 637–638. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Shan, S.Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, M. Progress of researches on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Bombyx batryticatus. China Pharm. 2014, 25, 3732–3734. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Chen, F.; Yu, F. Progress of research on Bombyx batryticatus. Guid. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharmacol. 2015, 21, 101–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Liao, S.T.; Xing, D.X.; Luo, G.Q.; Wu, F.Q. Advances in chemical composition of Bombyx batryticatus and its identification techniques. Sci. Ser. 2009, 35, 696–699. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.W.; Peng, X.W. Study on processing technology of Bombyx batryticatus stir-fried with bran. J. N. Pharm. 2013, 10, 39–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Q.F. Processing Science of Traditional Chinese Medicine; China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 134. ISBN 9787801563088. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.B.; Liu, Y.J.; Xie, D.S.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y.C.; Wu, C.J. The research on the Maillard reaction in the process of Bombyx batryticatus stir-fried with bran. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2016, 39, 2251–2254. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Chinese Materia Medica; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1998; pp. 179–182. ISBN 9787532344345. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J. Eczema Treat. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1986, 27, 10–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.L. Clinical Experience of Skin Disease; China Medical Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 333. ISBN 9787506723343. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.X. Treatments of 100 skin disease cases with modified Shufeng Huoxue decoction. J. Sichuan Tradit. Chin. Med. 1994, 11, 49–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Q.; Wang, L.Y.; Wang, L.P.; Li, Y.N. Observation on the treatment of allergic dermatosis by using modified Xiaofeng powder. China’s Naturop. 1996, 4, 33–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.J. 4 cases of skin diseases. New. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2002, 35, 62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.Q. Experience in the treatment of diabetic complications using Bombyx batryticatus. Clin. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2004, 16, 222. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.M. Clinical observation of 38 prurigo nodularis cases treated with comprehensive TCM. Guid. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharmacol. 2005, 11, 45–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.Y. Treatments of 33 pediatric multiple cases using Bombyx batryticatus powder. Tianjin Tradit. Chin. Med. 1995, 12, 21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.L. The treatment of chloasma using Bombyx batryticatus. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009, 50, 725. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.G.; Du, W. Exact effect on allergic rhinitis with Bombyx batryticatus. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009, 50, 725. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Z.J. Clinical application of Bombyx batryticatus. Inf. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1999, 17, 23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Han, Y.; He, X.Z.; Zhang, Z.L. Zhang Zong-li experience in treatment of intractable proteinuria by using Bombyx batryticatus and Cicadae Periostracum. Hunan J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2016, 32, 34–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z. Experience of Professor Ba Yuanming in using TCM herb pairs to treating kidney disease. Acta Chin. Med. 2017, 32, 229–231. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Q.; Zhang, H.L.; Liu, R.J.; Zhang, W.B. Example for experience cases on the clinical application of Bombyx batryticatus of Zhang wen tai aged traditional Chinese medicine doctors. Guangming Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 30, 138–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.B.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, W.P.; Jing, W. Clinical applications of Bombyx batryticatus. Shandong J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 34, 961–962. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.M.; Xiong, M.B. Bombyx batryticatus has good effect on fever. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009, 50, 1108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.M.; Zhou, S.J. Treatment of hypertension using Bombyx batryticatus. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009, 50, 1108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.R. Dictionary of Chinese Pharmacy; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; p. 423. ISBN 9780325454252. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.A. Research reports of Beauveria bassiana and related problems on the production of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Xinxiang Teach. Coll. 1982, 23, 63–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.W.; Shi, L.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhan, Z.L. Herbal textual research on origin and development of Bombyx batryticatus. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2017, 28, 171–173. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.; Xu, C.; He, Z.L.; Zhou, Q.M.; Wang, J.B.; Li, Z.Y.; Ming, X. A novel peptide inhibitor of platelet aggregation from stiff silkworm, Bombyx batryticatus. Peptides 2014, 53, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.M.; Su, M.S.; Zhang, Y.M.; Shao, F.; Yang, M.; Zhang, P.Z. Chemical Constituents from Bombyx batryticatus. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2017, 41, 87–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.H. Study on the Quality Standard of Bombyx batryticatus. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, China, 2006. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. The pharmacological research and clinical application of batryticated silkworms and muscardine pupae. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2003, 14, 492–494. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.M.; Deng, H.Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.Z.; Yang, M. Chemical constituents from Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drug. 2015, 46, 2377–2380. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y. The Study on the Isolation and Purifition about the Anticoagulation of Bombyx batryticatus. Master’s Thesis, Hunan College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Changsha, China, 2004. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.M.; Li, G.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.H. Study on chemical constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. Mod. Chin. Med. 2013, 15, 544–547. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Hou, L.; Yu, R.X.; Zhang, Y.J. Analysis of enzymolysis polypeptide from Bombyx batryticatus by LC–MS. Chem. Anal. Meter. 2017, 26, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.Q.; Ye, W.C.; Zhao, S.X. Studies on the chemical constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2004, 28, 52–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.F.; Sun, J.M.; Zhang, H. Bombyx batryticatus’s chemical components and pharmacological activities. Jilin J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 35, 175–177. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.S.; Wang, J.H.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.Q. Main chemical constituents of Bombyx batryticatus and its volatile oil analysis. Chem. Bioeng. 2003, 20, 22–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.C.; Lee, K.C.; Cho, O.R.; Jung, I.Y.; Cho, S.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, K.R. Sphingolipids from Bombycis Corpus 101A and their neurotrophic effects. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.C.; Jung, I.Y.; Cho, S.Y.; Cho, O.R.; Yang, M.C.; Lee, S.O.; Hur, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Yang, J.B.; Lee, K.R. Phospholipids from Bombycis corpus and their neurotrophic effects. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003, 26, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.M. Content analysis of quercetin and kaempferol in Bombyx batryticatus by RP-HPLC. Feed Ind. 2009, 30, 48–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wen, H.M.; Zhang, A.H.; Yu, L.; Guo, R. The content determinations of 4 kinds of nucleosides and bases in HPLC method. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 1996, 6, 46–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, G.Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.H. Study on steroids constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. Study on steroids constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Shihezi Univ. 2013, 31, 724–728. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.Q.; Ye, W.C.; Zhao, S.X. A new coumarin glycoside from Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drug. 2004, 35, 1205–1207. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Shi, L. Structural elucidation and in vitro antitumor activity of a novel oligosaccharide from Bombyx batryticatus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 15, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.J.; Xu, G.M.; Li, M.J.; Jiang, X.M. Determination of oxalic acid ammonium in Bombyx batryticatus by HPLC. Cent. S. Pharm. 2006, 4, 255–257. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A.X.; Song, Y.Y.; Yao, L.H.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, J.Y. Determination of ammonium oxalate in Bombyx batryticatus by ultrasonic extraction-high performance liquid chromatography. Chin. J. Anal. Lab. 2016, 35, 941–944. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.J.; Peng, Y.G.; Zeng, X.Q.; Zhao, J.G.; Jiang, X.M.; Gao, J. Quantitative analysis of protein and ammonium oxalate in the extract liquide from Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. J. Inform. TCM 2005, 12, 38–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xing, D.X.; Liao, S.T.; Luo, G.Q.; Li, L.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Q.R.; Ye, M.Q.; Yang, Q. Extraction process optimization and antioxidant activity determination of polysaccharide from Bombyx batryticatus. Sci. Seric. 2015, 41, 1088–1093. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.Q.; Ju, G.C.; Li, H.P.; Zhao, J. Analysis of chemical constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Jilin Agric. Univ. 1995, 7, 44–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.H.; Yan, Z.Y.; Liu, T.; Song, D.M.; Li, X.H. Anticonvulsive activity of three compounds isolated from Beauveria bassiana. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Form. 2013, 19, 248–250. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.H.; Wu, Y.Y.; Song, D.M.; Yan, Z.Y.; Liu, T. Compounds isolated and purified from chloroform active part of Bombyx batryticatus and their anticonvulsive activities. Chin. J. Pharm. 2014, 45, 431–433. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.Y.; Li, X.H.; Chen, X.; Peng, C.; Liu, Y.P.; Xiang, C. Aprimary study on anticonvulsant parts of BombyxmoriL. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2006, 17, 696–697. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.W.; He, X.G.; He, Q.Y.; Yang, L.H.; Ma, Y.G. Comparative study on the anticonvulsant effect of alcohol extract of Bombyx batryticatus and Scolopendra. Chin. Remed. Clin. 2006, 3, 221–223. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xu, M.T.; Xia, Z.Y.; Cheng, F. Effects of ammonium oxalate on the epilepsy rat model caused by penicillin. Med. J. Wuhan Univ. 2009, 30, 97–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.Y.; Peng, X.J.; Peng, Y.G. Modern research progress of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Hunan Coll. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2003, 25, 62–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.F.; Wang, J.P.; Fan, R.P.; Chen, X.J.; Xu, Y.X.; Pang, C.Y. Study on the sedation of Bombyx batryicatus. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2005, 16, 1113–1114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.S.; An, H.G.; Moon, S.K.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, H.M.; Ko, J.H.; Kim, C.H. Bombycis corpus extract (BCE) protects hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Immunopharm. Immun. 2003, 25, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, W.H.; Yoon, C.H.; Jeong, J.C.; Nam, K.S.; Kim, H.M.; Choo, Y.K.; Lee, M.C.; Kim, C.H. Bombycis corpus extract prevents amyloid-beta-induced cytotoxicity and protects superoxide dismutase activity in cultured rat astrocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2001, 43, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.D.; Narui, T.; Kurata, H.; Takeuchi, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Okuyama, T. Hematological studies on naturally occurring substances. II. Effects of animal crude drugs on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis systems. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989, 37, 2236. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.G.; Peng, X.J.; Peng, Y.G.; Zeng, X.Q.; Jiang, X.M.; Zhang, Y.H.; Lu, M.F. Influence of ammonium oxalate on the action of anticoagalation on stiff silkworm. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2005, 16, 468–469. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.G.; Lei, T.X.; Fu, C.Y.; Zeng, X.Q.; Li, L.D. Effect of anticoagulant components in Bombys batryticatus on thrombosis. Pharmacol. Clin. Chin. Mater. Med. 2007, 23, 27–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.G.; Li, L.D.; Deng, Y.H. Study on anti-venous thrombosis and its mechanism in Bombys batryticatus. Chin. J. Thromb. Hemo 2001, 8, 104–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.Y.; Su, Y.; Peng, Y.G. Effect of Bombyx batryticatus injection on the balance of fibrinolytic system of human umbilical vascular endothelial cell induced by thrombin. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. Intens. Crit. Care 2007, 14, 70–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. Studies on Toxicology of Hela Which Treat with Ethanol Extracts of Bombyx baticatus. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A & F University, Xianyang, China, 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.G. Optimization of flavonoids extraction from Bombyx batryticatus using response surface methodology and evaluation of their antioxidant and anticancer activities in vitro. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 22, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.P.; Cao, J.; Wu, J.Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, D. Anticancer activity of Bombyx batryticatus ethanol extract against the human tumor cell line HeLa. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 15, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Y.; Sheikho, A.; Ma, H.; Li, T.C.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, D. Molecular mechanisms of Bombyx batryticatus ethanol extract inducing gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells apoptosis. Cytotechnology 2017, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.G.; Jiang, X.H.; Liu, Z.M.; Huang, S.Q.; Zhou, J.Y. Study on anti-tumor activity of seven chemical constituents of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Zhongkai Univ. Agric. Eng. 2015, 28, 35–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, L.P.; Chai, W.L.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.W.; Tang, G.H.; Lv, L.; Wang, D. Analysis on antibacterial components from Bombyx batryticatus and its antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli. J. Northwest Agric. For. Univ. 2010, 38, 150–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, W.L.; Xiang, L.P.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.W.; Tang, G.H.; Lv, L.; Wang, D. Inhibitory effect of alcohol extract of Bombyx batryticatus on pathogenic fungi of forest. For. Pract. Technol. 2009, 52, 33–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Niu, W.F.; Zhang, J.Z.; Hou, B.S.; Liu, Y.T.; Zhou, C.Z. To determine the effective in vitro antiviral part of Bombyx Batryticatus. Shandong J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2016, 35, 909–911. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.F.; Ma, H.; Zhao, S.N.; Niu, M.M.; Xing, Y.Y.; Wang, D. Enhancement of HearNPV by ethanol extact of Bombyx batryticatus. J. Northwest Agric. For. Univ. 2014, 42, 119–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Huo, L.Q.; Jia, T.Z. Effects of Different Processing Methods on in vitro Antioxidant Activity and Inhibiting Capacity for Tyrosinase of Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Form. 2014, 20, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.Y. Treatments of 52 diabetes cases using powder of Bombyx batryticatus. Hunan J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1990, 17, 37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.J. Treatments of type 2 diabetes using Bombyx batryticatus. China’s Naturop. 2016, 24, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.L.; Zhang, D.F. Treatments of headache using Bombyx batryticatus singly. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2009, 50, 1011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.J.; Mao, X.P.; Xiao, Q.C.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, X.Y. Pharmacological study of antifertility on Bombyx batryticatus. J. Yunnan Coll. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2002, 25, 26–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. Researches on Separation, Purification and Pharmacological Effects of Active Components of Bombyx batryticatus. Doctor’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.Y. Clinical treatment of 46 acute poisoning cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus. Mod. J. Integr. Tradit. Chin. West. Med. 2007, 16, 371–372. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H. Clinical observation of toxicity of Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. Commun. Doc. 2011, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.H.; Yan, Y.H.; Qiu, S.S.; Guo, X.F. Retrospective analysis of 425 poisoning cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus. Strait. Pharm. J. 2011, 23, 244–245. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.S.; Xiang, S.H. Clinical analysis of 248 poisoning cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus. Clin. Focus 2004, 18, 495. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Qian, J.; Tang, W.J. Analysis of one poisoning case taking powder of Bombyx batryticatus. Clin. Misdiag. Misther. 2011, 24, 73–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.H. Emergency nursing to one extrapyramidal reaction cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus. Chin. Commun. Doc. 2011, 13, 134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.H. 2 cases of muscular myoclonus caused by Bombyx batryticatus. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2011, 52, 1889. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.X.; Zhang, Z.W.; Zhang, Z.K. Reports of 2 poisoning cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus and countermeasures. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013, 54, 808–810. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kao, X.L. Report of 1 poisoning cases caused by Bombyx batryticatus. J. Zhejiang Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2013, 37, 306–307. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.H. Research progress in fungi and mycotoxin infection of medicinal plants and their products. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2008, 36, 59–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Cheng, D.Q.; Lin, M.A.; Ding, Z.S.; Pan, P.L. Research on the toxic effect of extracellular proteins secreted by Beauveria bassiana on mice. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2008, 27, 1541–1542. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).