Utility–Leakage Trade-Off for Federated Representation Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Formulation

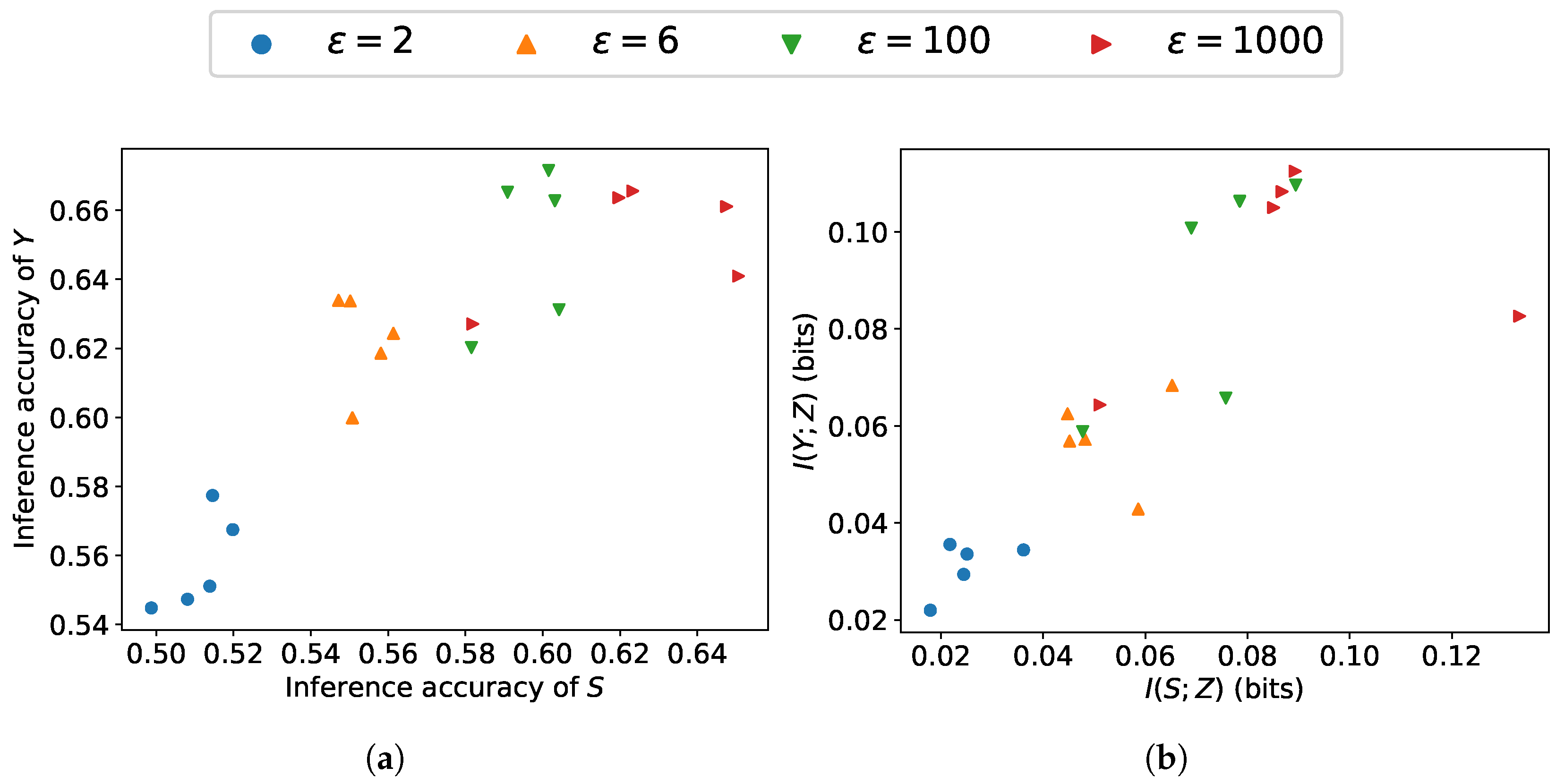

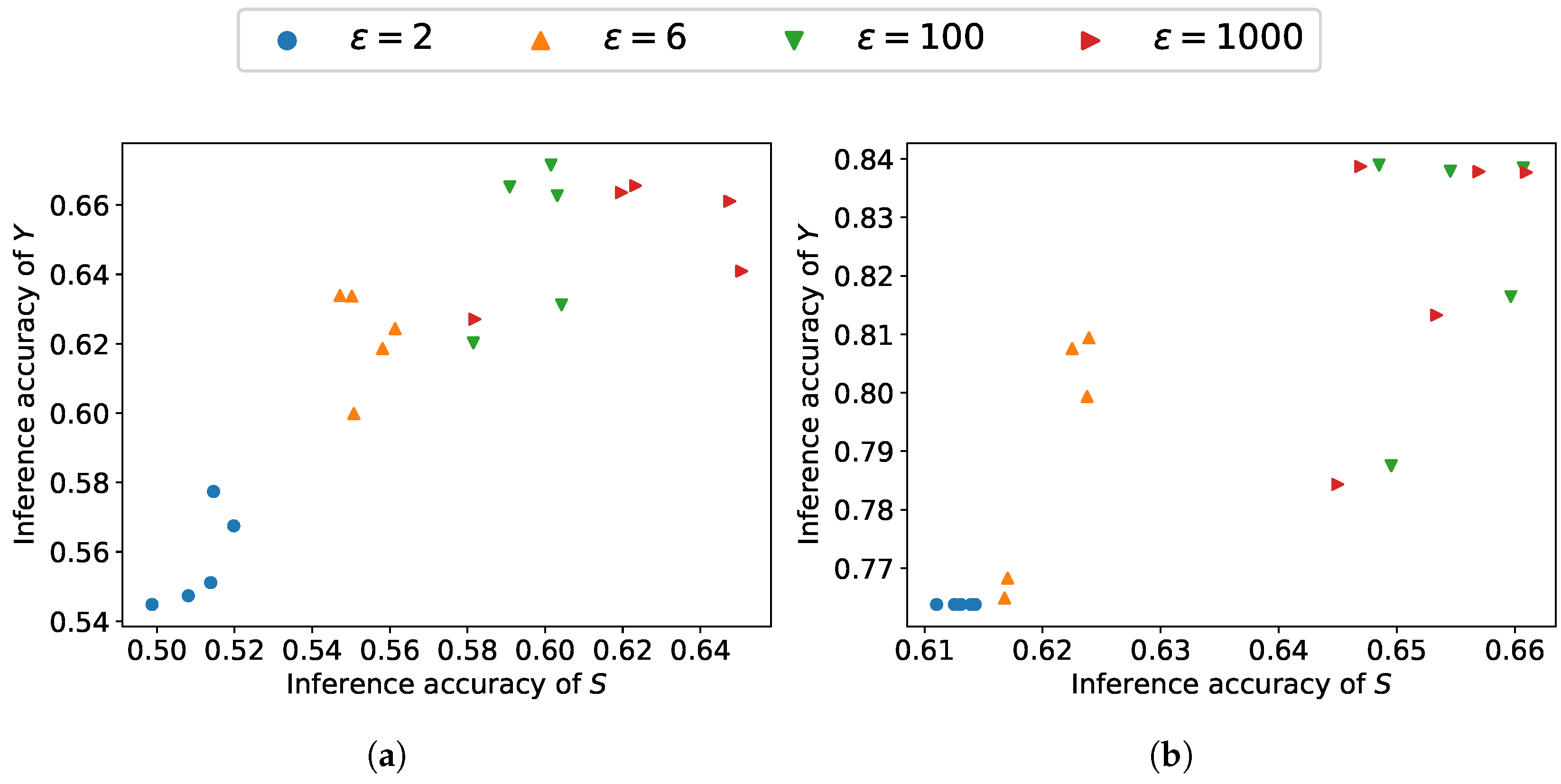

2.1. FRL with Sensitive Attribute

2.2. Sensitive Information Leakage–Utility Model

3. Leakage-Restrained Federated Representation Learning

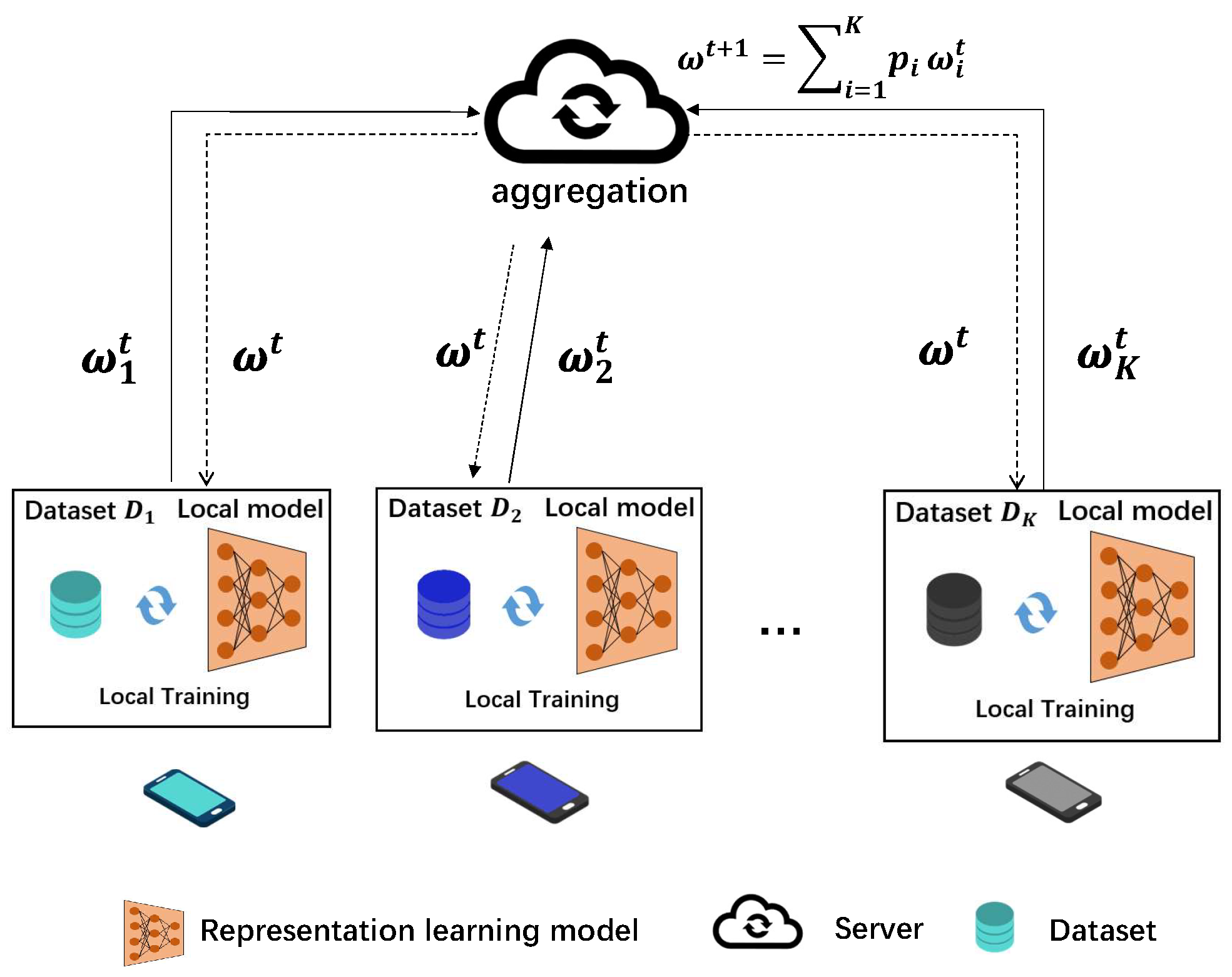

3.1. Proposed FRL Framework

- According to Definition 1, assures that the system is -sensitive information leakage guarantee.

- If , thenThis enable us to minimize the upper bound of as follows:

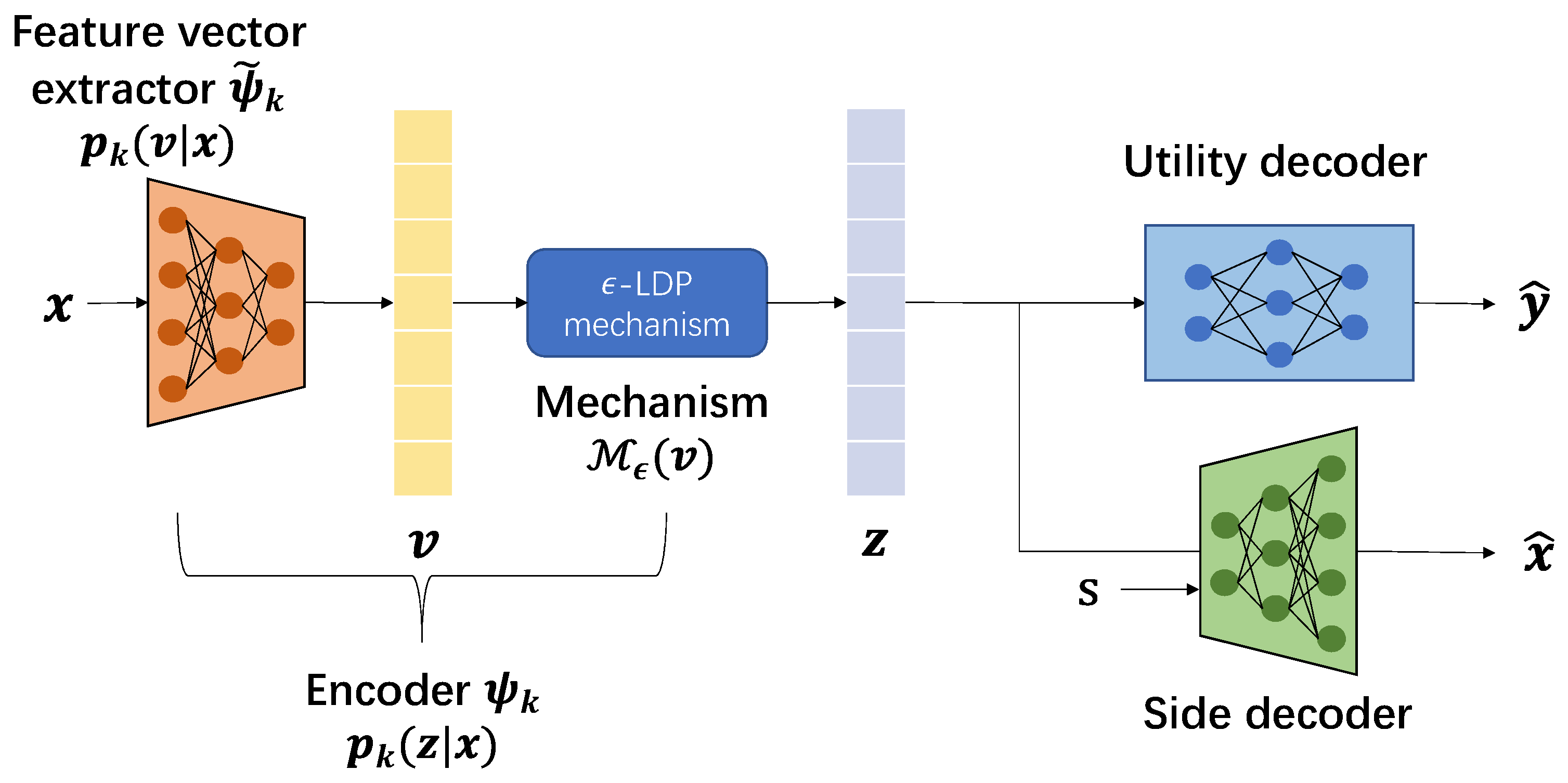

- The feature extractor parameterized by encodes the original data x into feature vector v.

- The -LDP mechanism maps the feature v to an obfuscated representation z.

- The utility decoder takes the representation z as input and predicts utility variable as .

- The side decoder takes both representation z and sensitive attribute s as inputs to reconstruct input data as .

- (Bernoulli)

- (Gaussian)

| Algorithm 1 FRL with sensitive information protection. |

|

3.2. Guarantee of Sensitive Information Protection

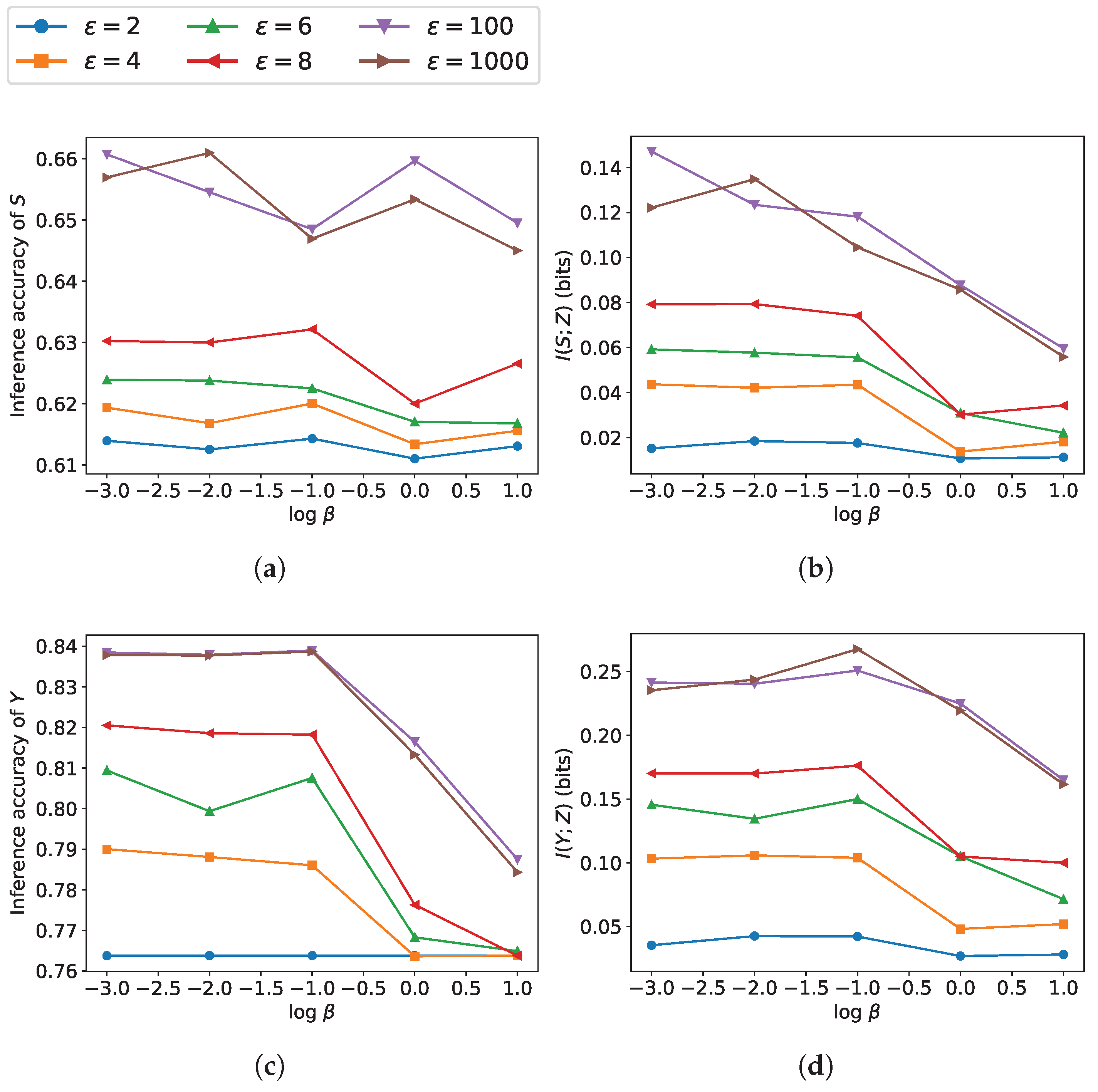

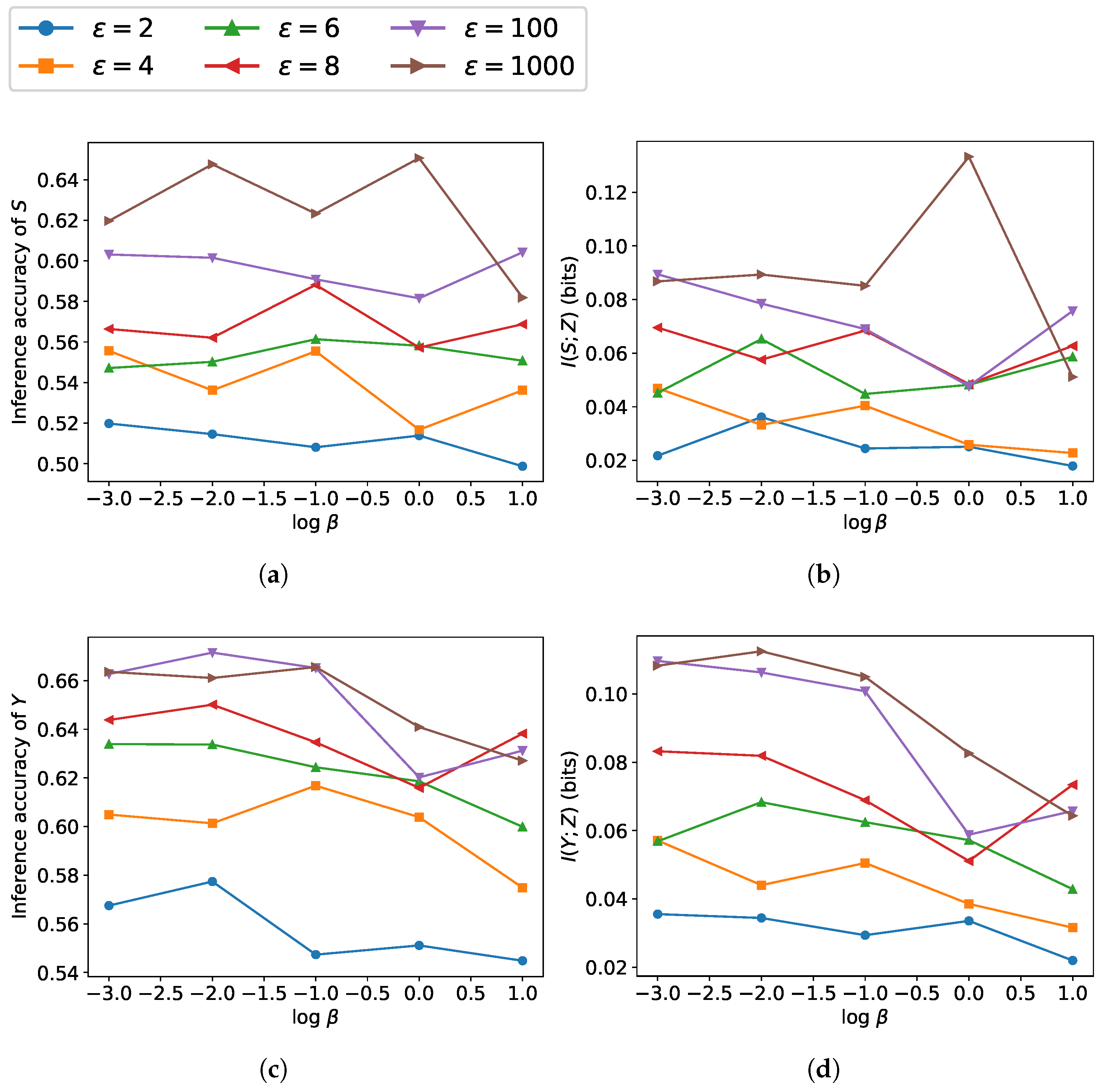

4. Simulation Results

- The estimated lower bound may fail to closely approximate the true mutual information, particularly when its actual value is small.

- Neural network-based estimation can suffer from high variance. This problem is amplified when dealing with high-dimensional data.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.Y. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Found. Trends® Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Chaudhuri, K.; Sarwate, A.D. Stochastic gradient descent with differentially private updates. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing, Austin, TX, USA, 3–5 December 2013; pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bassily, R.; Smith, A.; Thakurta, A. Private empirical risk minimization: Efficient algorithms and tight error bounds. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 55th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 18–21 October 2014; pp. 464–473. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.C.; Klein, T.; Nabi, M. Differentially private federated learning: A client level perspective. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.07557. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Learning differentially private recurrent language models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.06963. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Ma, C.; Yang, H.H.; Farokhi, F.; Jin, S.; Quek, T.Q.; Poor, H.V. Federated learning with differential privacy: Algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 15, 3454–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; McMahan, H.B.; Mironov, I.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Deep learning with differential privacy. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, D.; Aggarwal, C.C. On the design and quantification of privacy preserving data mining algorithms. In Proceedings of the Twentieth ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems, Santa Barbra, CA, USA, 21–23 May 2001; pp. 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Calmon, F.P.; Makhdoumi, A.; Médard, M. Fundamental limits of perfect privacy. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Hong Kong, China, 14–19 June 2015; pp. 1796–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Wang, Y.; Ishwar, P. Privacy-Preserving Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.07008. [Google Scholar]

- Sreekumar, S.; Gündüz, D. Optimal Privacy-Utility Trade-off under a Rate Constraint. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Paris, France, 7–12 July 2019; pp. 2159–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, B.; Calmon, F.P.; Gunduz, D.; Voloshynovskiy, S. Bottlenecks CLUB: Unifying Information-Theoretic Trade-Offs Among Complexity, Leakage, and Utility. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 2060–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Pin Calmon, F.; Fawaz, N. Privacy against statistical inference. In Proceedings of the 2012 50th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), Monticello, IL, USA, 1–5 October 2012; pp. 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, D.; Gomez-Vilardebo, J.; Tan, O.; Poor, H.V. Information theoretic privacy for smart meters. In Proceedings of the 2013 Information Theory and Applications Workshop (ITA), San Diego, CA, USA, 10–15 February 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Gálvez, B.; Thobaben, R.; Skoglund, M. A variational approach to privacy and fairness. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW), Kanazawa, Japan, 17–21 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman, F.; Dutta, S. Demystifying local and global fairness trade-offs in federated learning using information theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2023, Honolulu, HI, USA, 28 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Xie, T.; Wu, X.; Maciejewski, R.; Tong, H. Infofair: Information-theoretic intersectional fairness. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 1455–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassami, A.; Khodadadian, S.; Kiyavash, N. Fairness in supervised learning: An information theoretic approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Vail, CO, USA, 17–22 June 2018; pp. 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kasiviswanathan, S.P.; Lee, H.K.; Nissim, K.; Raskhodnikova, S.; Smith, A. What can we learn privately? SIAM J. Comput. 2011, 40, 793–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuncion, A.; Newman, D. UCI Machine Learning Repository; University of California: Irvine, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich, W.; Mendoza, C.; Brennan, T. COMPAS Risk Scales: Demonstrating Accuracy Equity and Predictive Parity; Northpointe Inc.: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, L.; Tao, D. Variational approach for privacy funnel optimization on continuous data. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 137, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creager, E.; Madras, D.; Jacobsen, J.H.; Weis, M.; Swersky, K.; Pitassi, T.; Zemel, R. Flexibly fair representation learning by disentanglement. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 1436–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Louizos, C.; Swersky, K.; Li, Y.; Welling, M.; Zemel, R. The variational fair autoencoder. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.00830. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, T.; Gao, H.; Shi, P.; Wang, X. Achieving Fairness through Separability: A Unified Framework for Fair Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Valencia, Spain, 2–4 May 2024; Dasgupta, S., Mandt, S., Li, Y., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (PMLR): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 238, pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

| Layer | Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder | Dense + ReLU Dense | 100 | 100 |

| Utility Decoder | Dense + ReLU Dense + Sigmoid | 100 | 100 2 |

| Side Decoder | Dense + ReLU Dense | 100 | 100 |

| LDP mechanism | Laplacian mechanism |

| Dataset | Method | Accuracy (Y) | Accuracy (S) | Accuracy (Y)-Accuracy (S) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPAS | ours | 0.6691 | 0.1192 | 0.5983 | 0.0098 | 0.1094 | 0.0708 |

| FFVAE | 0.5377 | 0.011 | - | - | - | - | |

| PPVAE | 0.6632 | 0.0897 | 0.9415 | 0.1485 | −0.0587 | −0.2783 | |

| VFAE | 0.6546 | 0.0567 | 0.9834 | 0.2865 | −0.2118 | −0.3288 | |

| FSNS | 0.6701 | 0.0760 | 0.6246 | 0.0207 | 0.0553 | 0.0455 | |

| Raw data | 0.6776 | 0.1776 | 0.6884 | 0.2506 | −0.0729 | −0.0108 | |

| Adult | ours | 0.8389 | 0.1938 | 0.6142 | 0.0325 | 0.1613 | 0.2247 |

| FFVAE | 0.7637 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| PPVAE | 0.7879 | 0.1633 | 0.7479 | 0.0769 | 0.0864 | 0.040 | |

| VFAE | 0.7865 | 0.1555 | 0.6672 | 0.0696 | 0.0859 | 0.1193 | |

| FSNS | 0.8126 | 0.2423 | 0.6689 | 0.0850 | 0.1573 | 0.1437 | |

| Raw data | 0.8527 | 0.3374 | 0.8391 | 0.4150 | −0.0776 | 0.0136 |

| Dataset | Method | Accuracy (Y) | Accuracy (S) | Accuracy (Y)-Accuracy (S) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPAS | ours | 0.6717 | 0.1103 | 0.6187 | 0.0758 | 0.0344 | 0.0530 |

| FFVAE | 0.5377 | 0.0797 | - | - | - | - | |

| PPVAE | 0.6627 | 0.1384 | 0.6639 | 0.5099 | −0.3715 | −0.0012 | |

| VFAE | 0.6659 | 0.1154 | 0.5910 | 0.6574 | −0.5420 | 0.0749 | |

| FSNS | 0.6722 | 0.1226 | 0.6293 | 0.1778 | −0.0552 | 0.0429 | |

| Raw data | 0.6776 | 0.1776 | 0.6884 | 0.2506 | −0.0729 | −0.0108 | |

| Adult | ours | 0.8364 | 0.2136 | 0.6595 | 0.0990 | 0.1146 | 0.1769 |

| FFVAE | 0.7637 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| PPVAE | 0.8118 | 0.2262 | 0.6995 | 0.2593 | -0.0331 | 0.1123 | |

| VFAE | 0.8073 | 0.2049 | 0.6684 | 0.1330 | 0.0719 | 0.1389 | |

| FSNS | 0.8335 | 0.2701 | 0.7071 | 0.2290 | 0.0411 | 0.1264 | |

| Raw data | 0.8527 | 0.3374 | 0.8391 | 0.4150 | −0.0776 | 0.0136 |

| Dataset | Method | Accuracy (Y) | Accuracy () | Accuracy () | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMAPS | ours only | 0.6691 | 0.1192 | 0.5983 | 0.0098 | - | - |

| ours and | 0.6533 | 0.0764 | 0.5890 | 0.0501 | 0.6295 | 0.0178 | |

| Adult | ours only | 0.8389 | 0.1938 | 0.6142 | 0.0325 | - | - |

| ours and | 0.8125 | 0.1485 | 0.6622 | 0.0363 | 0.6986 | 0.1173 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Günlü, O.; Shi, Y.; Wu, Y. Utility–Leakage Trade-Off for Federated Representation Learning. Entropy 2025, 27, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111163

Liu Y, Günlü O, Shi Y, Wu Y. Utility–Leakage Trade-Off for Federated Representation Learning. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111163

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yuchen, Onur Günlü, Yuanming Shi, and Youlong Wu. 2025. "Utility–Leakage Trade-Off for Federated Representation Learning" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111163

APA StyleLiu, Y., Günlü, O., Shi, Y., & Wu, Y. (2025). Utility–Leakage Trade-Off for Federated Representation Learning. Entropy, 27(11), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111163