Abstract

We study the probability of an undetected error for general q-ary codes. We give upper and lower bounds on this quantity, by the Linear Programming and the Polynomial methods, as a function of the length, size, and minimum distance. Sharper bounds are obtained in the important special case of binary Hamming codes. Finally, several examples are given to illustrate the results of this paper.

1. Introduction

Let be an alphabet with q distinct symbols, where and the alphabet do not have any structure. For instance, A can be , the finite field with q elements, or , the ring of integers modulo q. Moreover, a linear code is a subspace of the vector space and k is the dimension of the subspace. For every two vectors , , the (Hamming) distance between and is defined as the number of coordinates where they are different. A nonempty subset C of with cardinality M is called a q-ary code, whose elements are called codewords. The minimum distance d of the code C is the minimum distance between any two different codewords in C. The distance distribution of C is defined as

Assume that the code C is used for error detection on a discrete memoryless channel with q inputs and q outputs. Each symbol transmitted has a probability of being received correctly and a probability of being transformed into each of the other symbols. It is natural to let . Such a channel model is called a q-ary symmetric channel . When such a code is used on the symmetric q-ary channel , errors occur with a probability per symbol.

Let be the codeword transmitted and be the vector received, where is the error vector from the channel noise. Obviously, if and only if . Note that the decoder will accept as error free if . Clearly, this decision is wrong, and such an error is not detected. Thus, when error detection is being used, the decoder will make a mistake and accept a codeword which is not the one transmitted if and only if the error vector is a nonzero codeword [1,2]. In this way, the probability that the decoder fails to detect the existence of an error is called the probability of undetected error and denoted by , which is defined as

In general, the smaller the probability of undetected error for some p, the better the code performs in error detection. However, this function is difficult to characterize in general.

As for the code C, comparing its with the average probability [3,4] for the ensemble of all q-ary linear codes is a natural way to decide whether C is suitable for error detection or not, where

According to [4], there exists a code C such that and there are many codes, the of each of whom is smaller than . In fact, it was commonly assumed that for the linear code C in [5], where is called the bound. The bound is satisfied for certain specific codes, e.g., Hamming codes and binary perfect codes, when .

For the worst channel condition, i.e., when ,

From the above formula, a code C is called good if for all . In particular, if is an increasing function of p in the interval , then the code is good, and the code is called proper. There are many proper codes [1], for example, perfect codes (and their extended codes and their dual codes), primitive binary 2-error correcting BCH codes, a class of punctured of Simplex codes, MDS codes, and near MDS codes (see [5,6,7,8,9] for details). Moreover, for practical purposes, a good binary code C may be defined a bit different, i.e., for every and a reasonably small . Furthermore, an infinite class of binary codes is called uniformly good if there exists a constant c such that for every and , the inequality holds. Otherwise, it is called ugly, for example, some special Reed–Muller codes are ugly (see [10]).

Another way to assess the performance of a code for error detection is to give bounds of the probability of undetected error. In [11], Abdel-Ghaffar defined the combinatorial invariant of the code C and proved that

where

Using combinatorial arguments, Abdel-Ghaffar [11] obtained a lower bound on the undetected error probability . Later, Ashikhmin and Barg called the binomial moments of the distance function and derived more bounds for (see [12,13]).

In particular, constant weight codes are attractive and many bounds are developed, for example, binary constant weight codes (see [14,15]) and q-ary constant weight codes (see [16]). In fact, the probability of an undetected error for binary constant weight codes has been studied and can be given explicitly (see [14,16]).

Note that when and , according to Equation (2), we have

where , d is the minimum distance of C and is called the kissing number of the linear code C. In 2021, Solé et al. [17] studied the kissing number by Linear Programming and the Polynomial Method. They gave bounds for under different conditions and made tables for some special parameters. Motivated by the work, this paper is devoted to studying the function using the same techniques.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we briefly give the definition of the (dual) distance distribution of q-ary codes and give some trivial bounds of the probability of an undetected error. In Section 3.1, linear programming bounds are discussed. The applications of Krawtchouk polynomial (Polynomial Method) to error detection are given in Section 3.2. In Section 4, some bounds better than the bound are given for binary Hamming codes. Finally, we end with some concluding remarks in Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

Recall some basic definitions and notations from [2,18,19,20]. Throughout this paper, to simplify some formulas, we let and for some real k. Furthermore, in this paper, it is natural to define , equivalently, .

2.1. Dual Distance Distribution

Assume that is the finite field of size q and C is a subspace of , i.e., C is a linear code over . Then, the dual code of C is the orthogonal complement of the subspace C. That is to say,

where , and . The distance distribution of can be determined similarly. It is well known (see Chapter 5. §2. in [2]) that

where denotes the Krawtchouk polynomial of degree i. For each integer , the Krawtchouk polynomial is defined as

When there is no ambiguity for n, the function is often simplified to .

2.2. Probability of Undetected Error

The q-ary symmetric channel with symbol probability p, where , is defined as follows: symbols from some alphabet A with q elements are transmitted over the channel, and

where is the conditional probability that b is received, given that a is sent. For a q-ary code C, when it is used on such a channel, it is possible that the decoder fails to detect the existence of the errors. Thus, , the function in terms of the weight distribution of C is given in Equation (2). Clearly, this is a difficult computational problem for large parameters n, k, d, and q (see [2]). Hence, it is better to give bounds for . For example, here are some trivial bounds.

Theorem 1.

For every q-ary code C with , if , then

where . Especially, when and , we have

Proof.

It is easy to check that if and only if . Hence,

since when . The lower bound can be obtained similarly. □

The above bounds are trivial. However, they are both tight, because simplex codes over the finite field attain these bounds.

2.3. Some Special Bounds

It is clear that the general bounds given by Theorem 1 will be much larger (or smaller) than the true value of for a fixed code. If the distance distribution is known, one computes (as a function of p), and if we know some particular information about the distance distribution, then we may get some bounds. The following is a special case and more thoughts can be seen in Section 4.

Theorem 2.

Let C be a binary code with and for , then

Moreover, when , we have

and

where and .

Proof.

By the definition of , Equation (7) holds if and . Due to , It is easy to check that , where . In addition, if , then . Similarly for the case . Hence, we get the bounds. □

Remark 1.

If the binary code C satisfies and , we can get the following bounds:

and

Here, , the all zero vector, may not be a codeword.

Example 1.

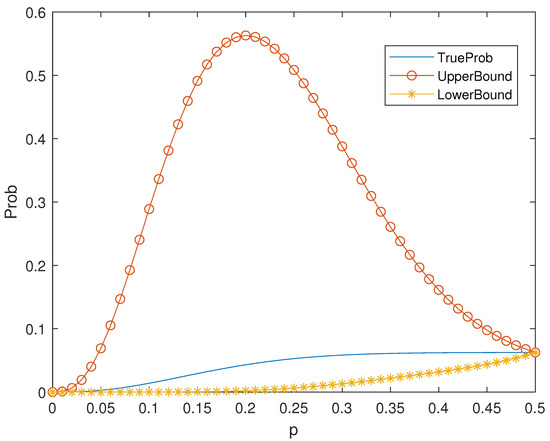

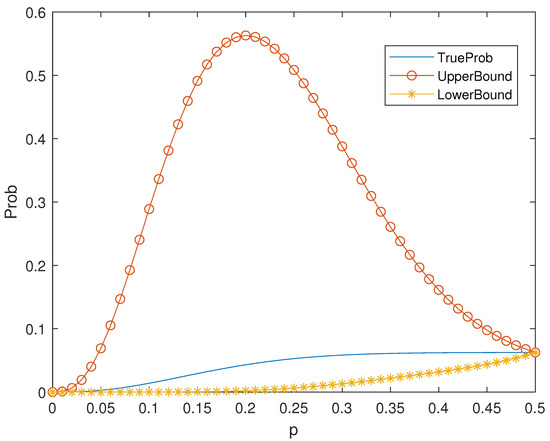

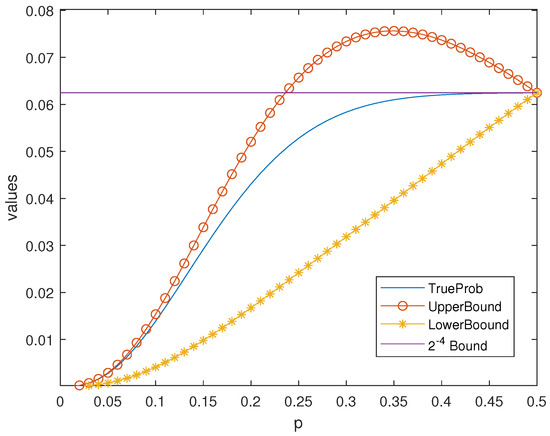

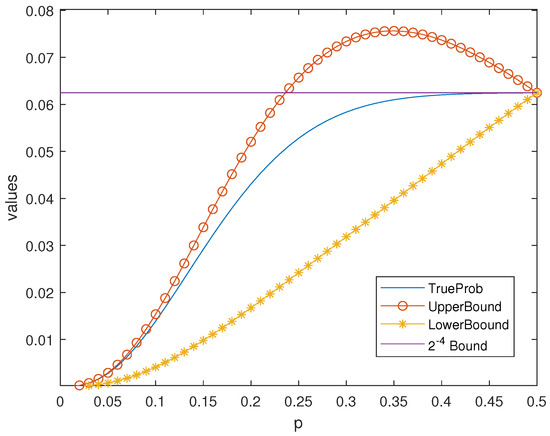

For a binary linear code, if the all-one vector is a codeword, then . So, Theorem 2 can be applied to many codes, for example, Hamming codes. It is known that the binary Hamming code is a linear code. The distance distribution of the Hamming code is listed in Table 1. According to Theorem 2, the values of the bounds and true probability can be seen in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Distance Distribution of the Hamming Code .

Figure 1.

Bounds in Theorem 2 of for the Hamming Code .

3. Universal Bounds for q-Ary Codes

In this section, we will discuss the bounds for using different methods. These bounds are for general codes, thus they do not look so good. Meanwhile, compared with some known bounds, they do not perform better. However, it is the first as far as we know to give bounds for using the following two methods, though they have been shown in [21,22] due to different thoughts.

3.1. Linear Programming Bounds

Consider the linear programming problem that maximizes the objec- tive function

under the constraints:

- (1)

- (2)

- ,

- (3)

- ,

- (4)

- .

Likewise, let be the minimization of the same objective function under the same constraints.

Theorem 3.

If C is a q-ary code of parameters then

Proof.

Remark 2.

Let and be two functions of x, then if or , when , where . For example, let and , then when . But , then when and .

Motivated by Equation (3) and [17], we have the following result.

Theorem 4.

Let C be a q-ary linear code, then when ,

where L (resp. S) denotes the maximum (resp. minimum) of subject to the constraints

for and .

Proof.

Table 2 is a part of Table I in [17], which is helpful to give bounds for .

Table 2.

Bounds of for Some Binary Codes.

Example 2.

Let be a binary code, then

As for the binary code , we have

Obviously, for any code, one can give bounds for its .

Remark 3.

From the above discussion, it is clear that our bounds depend solely on the three parameters of the code, and is the minimal requirement to use a code in practice.

3.2. Polynomial Method

In this section, we will give some general bounds for for any binary code. Recall the definition of the Krawtchouk polynomials and some properties. The following identity is a Polynomial Method of expressing the duality of LP.

Lemma 1.

Let be the polynomial whose Krawtchouk expansion is

Then we have the following identity

Proof.

Immediate by Equation (4), upon swapping the order of summation. □

From now on, we denote the coefficient of Krawtchouk expansion of the polynomial of degree n by , , i.e., .

The first main result of this section is inspired by Theorem 1 in [23], and given as follows.

Theorem 5.

Let and be polynomials over such that , for and for all i with . Then we have the upper bound

and the lower bound

Proof.

By Lemma 1, we have

Returning to the definition of and using the property of , we get

The proof of the lower bound is analogous and ommitted. □

Remark 4.

The above result is a special case of Proposition 5 in [22]. More general setting of the linear programming bounds from Section 3 (Theorem 5) were already considered in [21,22].

The following are some properties of the Krawtchouk expansion, and we omit the proof, since they are not difficult.

Lemma 2

([24] Corollary 3.13). Let and be polynomials over , where , . Then the coefficients of the Krawtchouk expansion of are nonnegative, where are nonnegative rational numbers.

3.2.1. Upper Bounds

For convenience, let be the Kronecker symbol, i.e.,

Lemma 3.

For general q, the coefficients of the Krawtchouk expansion of the following polynomial

are all nonnegative if and only if i is odd, where is an integer and . Moreover, .

Proof.

Let

where . Then, by Proposition 5.8.2 in [20],

Note that if , we have

According to Lemma 2, the coefficients of the Krawtchouk expansion of are all nonnegative.

Obviously, for any , , because j is a root of . Moreover,

which means . □

Theorem 6.

Let C be a binary code with the distance distribution , where for all possible odd j, then

where even i means that i runs through the even intergers between d and n.

Proof.

According to Lemma 3, the coefficients of the Krawtchouk expansion of the following polynomial:

are nonnegative if and only if i is odd. Then, let

Hence, , for even i and for odd i. By the proof of Theorem 5,

where

and

Thus, the upper bound follows from Theorem 5. □

Remark 5.

If C is linear, then is the number of codewords of weight i, which implies that . Hence,

where . Moreover, if for all odd i, then

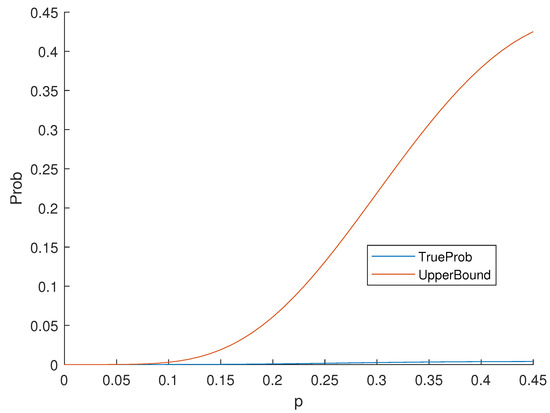

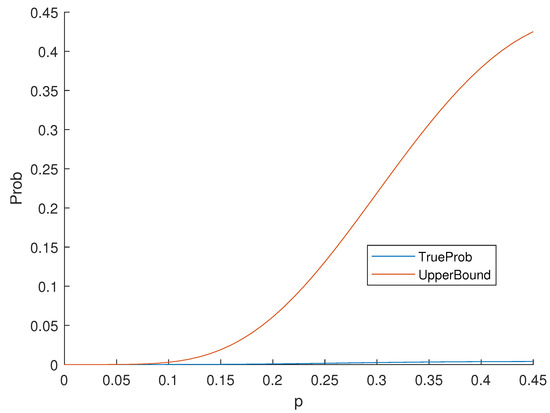

Example 3.

Consider the Nordstrom–Robinson code, it is a binary nonlinear code with the distance distribution in Table 3. Moreover, the weight distribution is the same as the distance distribution. By Equation (2),

According to Theorem 6, the values of the upper bound and true probability can be seen in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Distance Distribution of the Nordstrom–Robinson Code.

Figure 2.

The Probability of Undetected Error of the Nordstrom–Robinson Code.

Example 4.

Let be the set of binary vectors of length n and even weight, then it is actually the Reed–Muller code in Problem 5 in [2] and is generated by all the binary vectors of weight 2. Hence,

Remark 6.

The bound is suitable for many codes, and thus it seems not good. In fact, there exists some code C, whose is very large.

Motivated by [17], we have the following upper bounds for linear codes over .

Proposition 1.

When C is a q-ary linear code and p is small enough, we have the following statements:

- (1)

- If , then

- (2)

- If , then

- (3)

- If , , , and only if , then

Proof.

These three bounds can be deduced easily by Equation (3) and Corollaries 4–6 in [17]. □

Remark 7.

The results in Corollary 4–6 in [17] are actually the upper bounds of under different conditions. Considering Equation (3), it is necessary to make p small enough. According to the proof of Theorem 4, if does not meet such bounds, then “<” holds.

3.2.2. Lower Bounds

Similar to Proposition 1, by Corollaries 1–3 in [17], we have

Proposition 2.

If C is a q-ary linear code, then we have the following statements:

- (1)

- If , then

- (2)

- If , then

- (3)

- If and all weights of C are in , with and , then

When using quadratic polynomials, we have the following bound.

Proposition 3.

Let , and be nonnegative rational numbers such that

then, for a binary code, we have

where .

Proof.

It is known that, when , , and . Let and then it is a quadratic function whose axis of symmetry is . Considering that , it is sufficient to show that

i.e., for . Equivalently,

The result follows from Theorem 5. □

4. Good Bounds for Hamming Codes

Recall that the weight enumerator of the code C is the homogeneous polynomial

where means the Hamming weight the codeword . The binary Hamming code is a code, with the weight enumerator

whose distance distribution satisfies

and the recurrence , ,

Moreover,

Let be a primitive element and let be the minimal polynomial of with respect to . According to Exercise 7.20 in [20], can be regarded as the generator polynomial of a Hamming code. Since , then

which implies that the all-one vector is a codeword of the Hamming code and .

Note that

Hence,

Let , where , then

According to Chapter 6, Exercise(E2), page 157 in [2], there are nonzero weights of . Considering that , we have if and only if . Since , then and we have

Obviously,

Similarly,

Thus,

and

Summarize the above discussions, we get

Theorem 7.

Proof.

Note that the upper bound should be larger or equal than the lower bound, then

It is sufficient to solve the inequality , due to . Hence, . □

Remark 8.

The difference of the upper bound and the lower bound is small.

Let and be the bound given by Equation (14) and Equation (15), respectively, where , and

In fact, H is a polynomial of p whose degree and the leading coefficient is

while the product is just a polynomial whose degree is 4. Then,

That is to say, the lower bound and the upper bound are very close. On the other hand,

Then,

Here, let , then its derivative is . Note that the roots of are . Since , then we choose the root . Hence,

Thus the difference of the upper bound and the lower bound is about at most, and tends to 0 when .

Example 5.

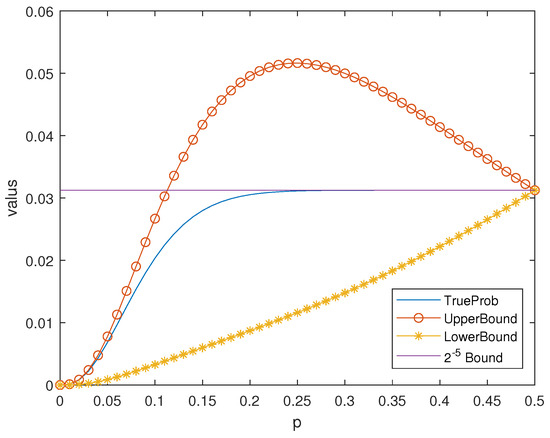

Figure 3.

Bounds in Theorem 7 of for the Hamming Code .

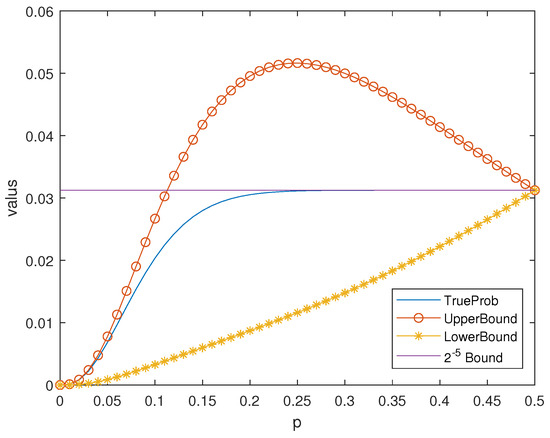

Figure 4.

Bounds in Theorem 7 of for the Hamming Code .

It is known that the Hamming codes satisfy the bound when i.e., . See [5] for more details. In fact, the obtained new bound is better than the ordinary bound, when p is not large.

Theorem 8.

Let be the binary Hamming code, then when and , we have

Moreover, if , this upper bound is better than the bound, where is the smaller root of the equation .

Proof.

Assume that

then it is sufficient to solve the inequality

Obviously, the inequality holds when , where

is the smaller root of the equation . □

Example 6.

Remark 9.

Of course, the weight distribution of the binary Hamming codes can be computed and expressed by the sum of combinatorial numbers, which are usually very large when m is large. So, the method in this section is to estimate quickly. Compared with the bound, our bounds are better when p is small enough.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the probability of an undetected error and gave many bounds for . The main contributions of this paper are the following:

- (1)

- The bounds obtained from the linear programming problem are given in Theorem 4. The bounds obtained from the Polynomial Method are given. According to the main Theorem 5, we get Theorem 6 (applied to the codes with even distances) and Proposition 3.

- (2)

- Combining the results of [17], we give the bounds in Propositions 1 and 2.

- (3)

- We find sharper bounds for binary Hamming codes (see Theorems 7 and 8).

To the best of our knowledge, that is the very first time that the LP method has been applied to bound . Even though computing exactly requires knowledge of the code weight spectrum, our bounds depend solely on the three parameters , of the code. The weight frequencies are only used as variables in the LP program. Knowing the three parameters is the minimal requirement to use a code in applications.

To sum up, our bounds are most useful when the exact weight distribution is too hard to compute. Our bounds perform well when p is small enough and the kissing number is known, and there are many such codes.

We mention the following open problems. The readers interested in Hamming codes are suggested to derive bounds for general q-ary Hamming codes with Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the linear programming problem works better numerically than the Polynomial Method. The interest of the latter lies in producing bounds with closed formulas. It is a challenging open problem to derive better bounds with polynomials of degree higher than 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S.; methodology, P.S.; software, H.L.; validation, X.W. and P.S.; formal analysis, X.W. and P.S.; investigation, X.W. and P.S.; resources, H.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and P.S.; visualization, H.L.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a publicly accessible repository.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Minjia Shi, Li Chen, and his colleagues for their helpful suggestions for improving the presentation of the material in this paper and pointing out the references [6,21,22,24].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Dodunekova, R.; Dodunekov, S.M.; Nikolova, E. A survey on proper codes. Discret. Appl. Math. 2008, 156, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- MacWilliams, F.J.; Sloane, N.J.A. The Theory of Error Correcting Codes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, J. Coding techniques for digital data networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Theory and Systems, NTG-Fachberichte, Berlin, Germany, 18–20 September 1978; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.K.; Michelson, A.M.; Levesque, A.H. On the probability of undetected error for linear block codes. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1982, 30, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung-Yan-Cheong, S.K.; Hellman, M.E. Concerning a bound on undetected error probability. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1976, 22, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, M.; Bianchi, M.; Chiaraluce, F.; Kløve, T. A class of punctured Simplex codes which are proper for error detection. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2012, 58, 3861–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasami, T.; Lin, S. On the probability of undetected error for the maximum distance separable codes. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1984, 32, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung-Yan-Cheong, S.K.; Barnes, E.R.; Friedman, D.U. On some properties of the undetected error probability of linear codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1979, 25, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.; Leung, C. On the undetected error probability of triple-error-correcting BCH codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1991, 37, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kløve, T. Reed-Muller codes for error detection: The good the bad and the ugly. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1996, 42, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghaffar, K.A.S. A lower bound on the undetected error probability and strictly optimal codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1997, 43, 1489–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikhmin, A.; Barg, A. Binomial moments of the distance distribution: Bounds and applications. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1999, 45, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barg, A.; Ashikhmin, A. Binomial moments of the distance distribution and the probability of undetected error. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 1999, 16, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.T.; Fu, F.W.; Jiang, Y.; Ling, S. The probability of undetected error for binary constant weight codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2005, 51, 3364–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.T.; Fu, F.W.; Ling, S. A lower bound on the probability of undetected error for binary constant weight codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2006, 52, 4235–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.T.; Fu, F.W. Undetected error probability of q-ary constant weight codes. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2008, 48, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, P.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Guilley, S.; Rioul, O. Linear programming bounds on the kissing number of q-ary Codes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW), Kanazawa, Japan, 17–21 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kløve, T. Codes for Error Detection; Kluwer: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lint, J.H. Introduction to Coding Theory, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, C.; Ling, S. Coding Theory: A First Course; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boyvalenkov, P.; Dragnev, P.; Hardin, D.; Saff, E.; Stoyanova, M. Energy bounds for codes in polynomial metric spaces. Anal. Math. Phys. 2019, 9, 781–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, H.; Zhao, Y. Energy-minimizing error-correcting codes. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2014, 60, 7442–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikmin, A.; Barg, A.; Litsyn, S. Estimates on the distance distribution of codes and designs. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2001, 47, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein, V. Universal bounds for codes and designs. In Chapter 6 of Handbook of Coding Theory; Pless, V.S., Huffman, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 499–648. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).